Abstract

Hypoxia promotes angiogenesis, proliferation, invasion and metastasis of pancreatic cancer. Essentially all studies of the hypoxia pathway in pancreatic cancer research to date have focused on fully malignant tumors or cancer cell lines, but the potential role of HIFs in the progression of pre-malignant lesions has not been critically examined. Here, we show that HIF2α is expressed early in pancreatic lesions both in human and in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. HIF2α is a potent oncogenic stimulus but its role in Kras-induced pancreatic neoplasia has not been discerned. We used the Ptf1aCre transgene to activate KrasG12D and delete Hif2α solely within the pancreas. Surprisingly, loss of Hif2α in this model led to not reduced but rather markedly higher number of mPanIN lesions. These low-grade mPanIN lesions, however, failed to progress to high-grade mPanINs, associated with exclusive loss of β-catenin and SMAD4. The concomitant loss of HIF2α as well as β-catenin and Smad4 was further confirmed in vitro, whereby silencing of Hif2α resulted in reduced β-catenin and Smad4 transcription. Thus, with oncogenic Ras expressed in the pancreas, HIF2α modulates Wnt-signaling during mPanIN progression, by maintaining appropriate levels of both Smad4 and β-catenin.

Keywords: Pancreas, cancer, HIF2-alpha, Wnt-signaling, neoplasia

Introduction

Like most adult epithelial malignancies, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) arises from non-invasive precursor lesions following a prolonged period of local inflammation and stress (1). Among the precursor lesions, the most common and extensively studied is pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN). The exact sequence of molecular events leading to full blown invasive cancer is still not clear, however genetic analyses have disclosed that PanINs already exhibit abnormalities in many of the same genes and pathways altered in PDAC, including Kras, CyclinD1, Smad4, Notch, Hedgehog, and β-catenin/Wnt (2, 3). Although, tight regulation of β-catenin/Wnt-signaling is required for the initiation of Kras-induced ductal reprogramming (4), our knowledge about the exact role β-catenin/Wnt-signaling may play during PanIN progression remains limited. Cells overcome hypoxic stress through multiple mechanisms, including the stabilization of the family of hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) transcriptional regulators. Two distinct transcription factors, HIF1α and HIF2α, regulate overlapping sets of target genes in hypoxic cells, although each protein also has unique functions (5–7). In the setting of normoxia, HIFs are ubiquinated through an oxygen-dependent interaction with von Hipple-Lindau (VHL) protein (8, 9). In humans, VHL is expressed in normal pancreatic ducts, but its expression is lost as early as in PanIN1As (10). HIF1α is absent in PanINs but is highly expressed in pancreatic cancer and has been recognized as an important resistance factor against chemotherapy and radiotherapy (11, 12). However, so far there have been no reports on the role of HIF2α in pancreatic cancer. Given the absence of VHL and HIF1α in PanINs (10, 11), we set out to study the potential role of HIF2α in pancreatic pre-malignant lesions. Specifically we hoped to determine whether loss of Hif2α would influence the progression of Kras-induced pancreatic neoplasia. We generated the Ptf1aCre;KrasG12D;Hif2αf/f mice, and studied Kras-mediated mPanIN progression in the absence of HIF2α.

Together, our findings demonstrate that β-Catenin/Wnt-signaling in the mPanINs is regulated by Smad4 expression and HIF2α plays a key role in orchestrating this process.

Materials and Methods

Human tissue specimens

Human pancreatic adenocarcinoma specimens were collected from patients who underwent surgical procedures. All studies with human pancreatic tissues were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Mice

Mice used in these studies were maintained according to protocols approved by the University of Pittsburgh IACUC. The Hif2α-floxed strain was generated by GHF (Supplementary Results and Discussion), the Ptf1Cre (13), KrasG12D (14), and Rosa26-HA-HiIF1dPA (15) strains were obtained from MMRRC, NCI Mouse Repository, and The Jackson laboratories, respectively.

Tissue processing and Immunostaining

Tissue processing and immunostaining were performed as previously described (16). For SMAD4 staining, antigen retrieval was performed in Tris-EDTA Buffer (10mM Tris Base, 1mM EDTA Solution, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 9.0) for 20 minutes at 95°C in steamer. For HIF2α, antigen retrieval was performed in IHC-Tek™ Epitope Retrieval Solution for 20 minutes at 95°C in steamer. Images were acquired on a Zeiss Imager Z1 microscope with a Zeiss AxioCam driven by Zeiss AxioVision Rel.4.7 software.

BrdU-labeling

BrdU-labeling was performed by injecting intraperitoneally (i.p.) BrdU (0.2 mg/g body weight) (Sigma) two hours prior to sacrifice.

Cell cultures

Low-passage cancer cells were isolated from PdxCre;KrasG12D;p53+/− tumors in Dr. M. T. Lotze laboratory, University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute as previously described (17). In brief, tumor fragments were digested with 2mg/ml collagenase V at 37 °C while agitating, then strained and washed to retrieve the tumor cells. Cells were subsequently plated in T25 flasks and expanded. After 3 passages, cells were tested for mesothelin expression. Tumor cells were frozen down and used for further expansion and testing as needed. Following thawing, cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS, 5% penicillin–streptomycin, and 5% glutamax. Cultures were maintained in 5% CO2 at 37°C in a humidified incubator.

Small Interfering RNA transfection

Endogenous Hif2α, β-catenin, and Smad4 in CPK cells were silenced using ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool siRNA (Dharmacon) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

RT-qPCR

Harvesting, tissues processing, and reactions were performed as previously described (16). PCR primers were purchased from Qiagen (QuantiTect® Primer Assays, Qiagen) and are listed in Supplemental Table 2.

Western Blot

Western blotting was done as described previously (18).

Results

Normal pancreatic development in the Hif2α-deficient pancreas

To study the role of HIF2α in pancreatic development and malignant transformation, we generated a Hif2α-floxed strain (Supplemental Figure 1), and crossed the homozygous mice (Hif2αf/f) with Ptf1aCre transgenic mice, which targets Cre recombinase expression to the epithelial lineages of the embryonic pancreas (13). Mice with homozygous deletion of Hif2α in the pancreas (Ptf1aCre;Hif2αf/f) were born at the expected frequency, and showed demonstrated normal pancreatic cytoarchitecture and differentiation throughout postnatal life (n=15 mice, ages 1–12 months) as evident by exocrine as well as endocrine immunostaining analyses (Supplemental Figure 2). More importantly, Ptf1aCre;Hif2αf/f mice did not develop pancreatic neoplasms.

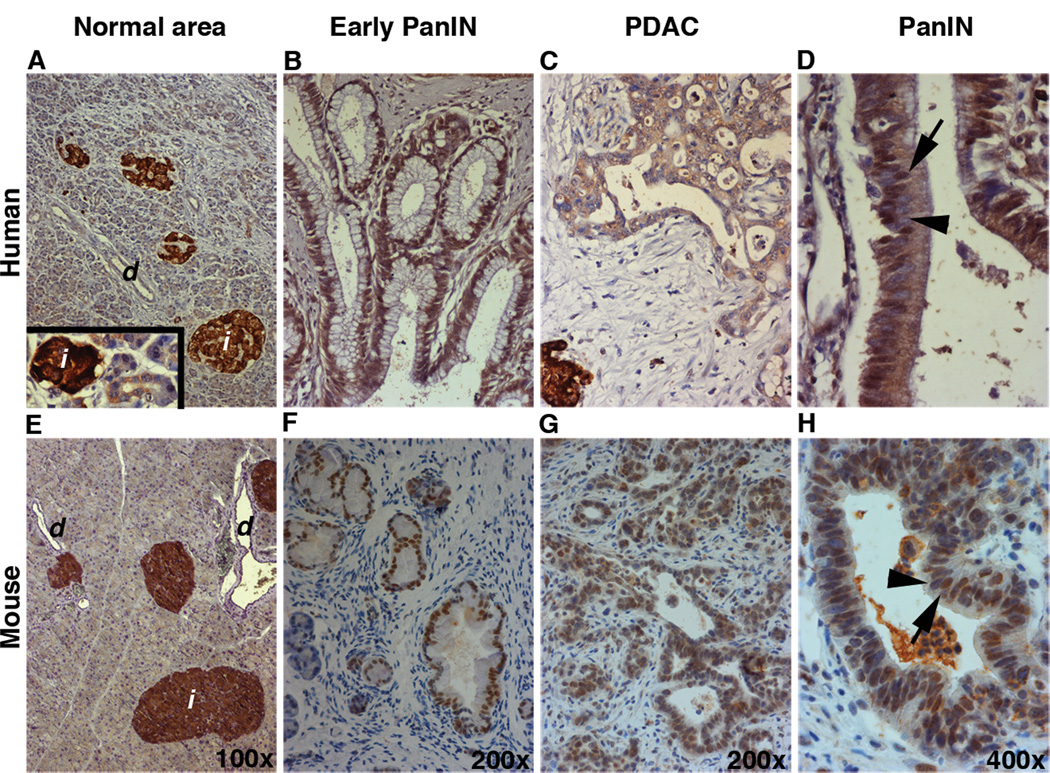

HIF2α expression decreases during malignant progression of pancreatic cancer

We first examined HIF2α expression in well-preserved surgical specimens from 11 patients with PDAC. In the region of histologically normal tissue, HIF2α could not be detected in the acinar or ductal compartments, but it was highly expressed in the endocrine islets (Figure 1A). Immuohistochemical analyses of human pancreatic adenocarcinoma tissues showed nuclear and/or cytoplasmic HIF2α localization within the metaplastic ducts (inset in 1A) and in the early stage mPanINs (Figure 1B). The levels of HIF2α protein gradually declined as the lesions progressed to more advanced stages (Figure 1C). Similarly, immunostaining analyses of Ptf1aCre;KrasG12D pancreata (PK mice) showed expression of HIF2α in the islets (Figure 1E) and a more prominent presence of HIF2α in less advanced lesions (Figure 1F) compared to PDAC (Figure 1G). As demonstrated in Figure 1D & H, adjacent cells within the same lesion in both human and mouse samples could display varying levels of HIF2α protein. Interestingly, although cells with low or no HIF2α expression could be occasionally found in PanIN1s, the presence of HIF2-negative or HIF2Low cells was more noticeable in the more advanced PanINs. These findings show that the dynamic expression of HIF2α observed in human PanIN and PDAC is associated with PanIN progression and is recapitulated in a mouse model of PDAC.

Figure 1.

HIF2α expression is gradually decreased during malignant progression. Immunohistochemical analyses for detection of HIF2α in human A–D and PK (E–H) pancreas. In the histologically normal pancreatic tissues in both human (A) and mice (E) HIF2α was absent in the acinar and ductal compartments. Inset in (A) shows acinar-to-ductal metaplastic structure with HIF2α-negative acinar cells turning into HIF2α-positive metaplastic ducts (arrowhead). HIF2α could be detected in early PanINs (B, F), whereas it’s expression was significantly reduced in more advanced lesions (C, G). Both human (D) and mouse (H) PanINs are composed of heteregenous populations of HIF2α-positive (arrows in G and H) and HIF2α-negative (arrowheads in G and H) cells. d: duct; i: islet.

HIF2α is required for mPanIN progression

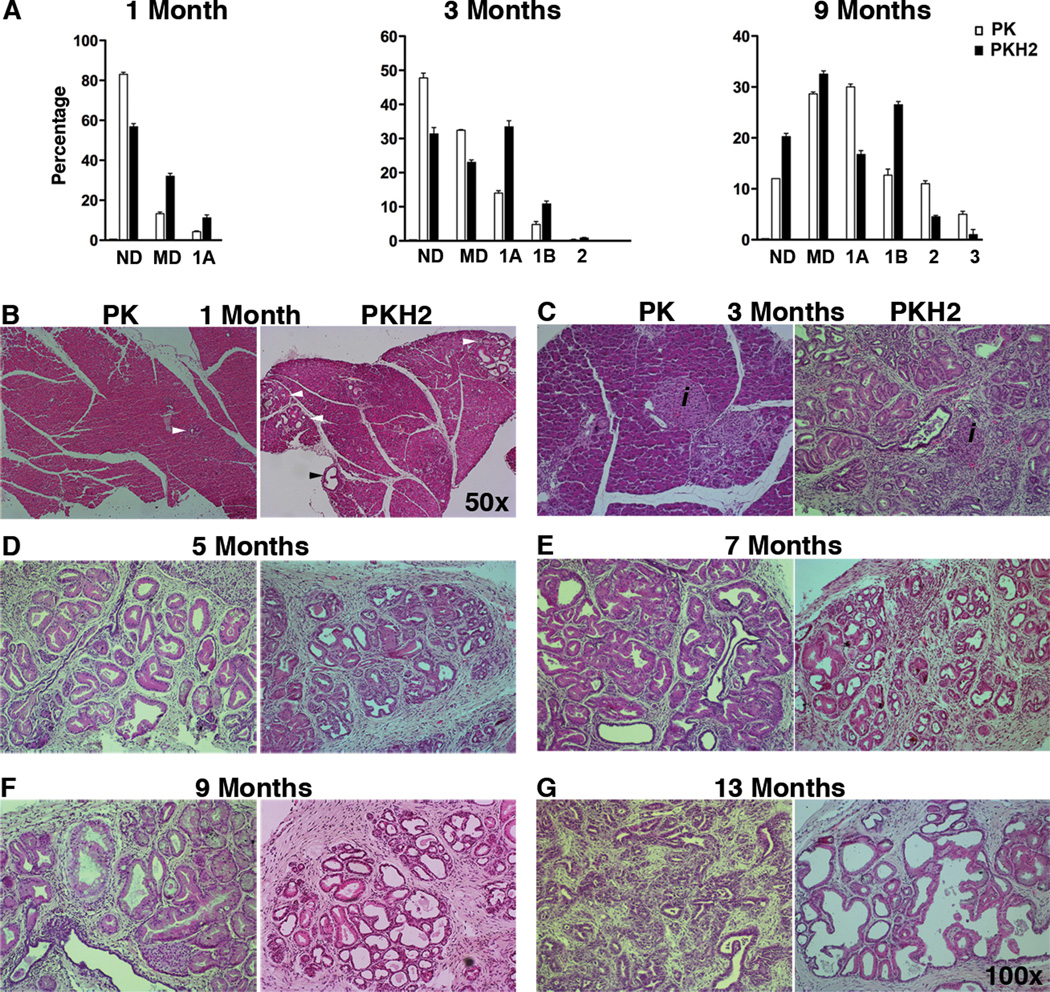

In order to study the loss of Hif2α in the setting of oncogenic Kras expression, Hif2αf/f mice were crossed with PK mice to generate the Ptf1aCre;KrasG12D;Hif2αf/f (PKH2 mice) strain. The absence of HIF2α in the early PanIN lesions in PKH2 mice confirmed the pancreatic inactivation of Hif2α (Supplemental Figure 1E). In the PK pancreas, only a few PanIN1As could be detected at 1 month of age (Figure 2A, B), while at 3 months early morphological changes including ADM and PanIN1A lesions could be detected (Figure 2C). By contrast, at 1 month, PKH2 mice showed acceleration of PanIN progression, with higher incidence of both metaplastic ducts and mPanIN1A lesions, although still in the context of intact lobule architecture (Figure 2A, B).

Figure 2.

HIF2α is required for mPanIN progression. (A) Higher early mPanIN incidence was observed in PKH2 pancreas. Columns, percentages (mean ± SE) of normal ducts, metaplastic ducts, and mPanINs by grade per total ductal structures in our two genotypes at 1, 3, and 9 months of age (n=5 for each cohort). (B–G) Representative tissues from PK and PKH2 collected at 1 (B), 3 (C), 5 (D), 7 (E), 9 (F) and 13 (G) months of age were stained for H&E. Arrowheads show the lesions on the sections. ND: Normal Ducts; MD: Metaplastic Ducts; 1A, 1B, 2, 3: mPanINs1A-3.

Between 1 and 3 months, there was evidence of further progression in PKH2 mice, with severe periductal stromal response, secondary loss of the lobular acinar parenchyma, as well as increased duct ectasia and PanIN1 lesions. At 3 months of age, PKH2 pancreata already displayed PanIN1B lesions, with a few of them transitioning to PanIN2 (Figure 2C). Compared to their age matched PK cohort, 3 month old PKH2 mice also demonstrated robust desmoplastic response, diffuse replacement of the acini by lobules with mucinous epithelium (PanIN1) and luminal dilation (with significant increase in the acinar-to-ductal ratio) (Figure 2C). From 3 months onward the PK mice displayed classic stepwise mPanIN formation (Figure 2D–F), and transition to PDAC (Figure 2G). Interestingly, the 9 month old PKH2 pancreas contained a similar percentage of PanIN1s as the PK mice (Figure 2A, D). The PK mice, however, contained more PanIN1A lesions, whereas the PKH2 mice contained more PanIN1B leions (Figure 2A). Nevertheless, despite the higher PanIN incidence in younger mice, there was a decrease in the number of PanIN2s in older PKH2 mice, and more advanced PanIN3s were rarely detected (Figure 2A, D–F). The changes within the lobules demonstrated increased cytoplasm with progressive increase in dilation and papillary projections into the dilated lumina (Figure 2G).

These findings suggest that HIF2α is dispensable for initiation of mPanINs, but it is required for mPanIN progression.

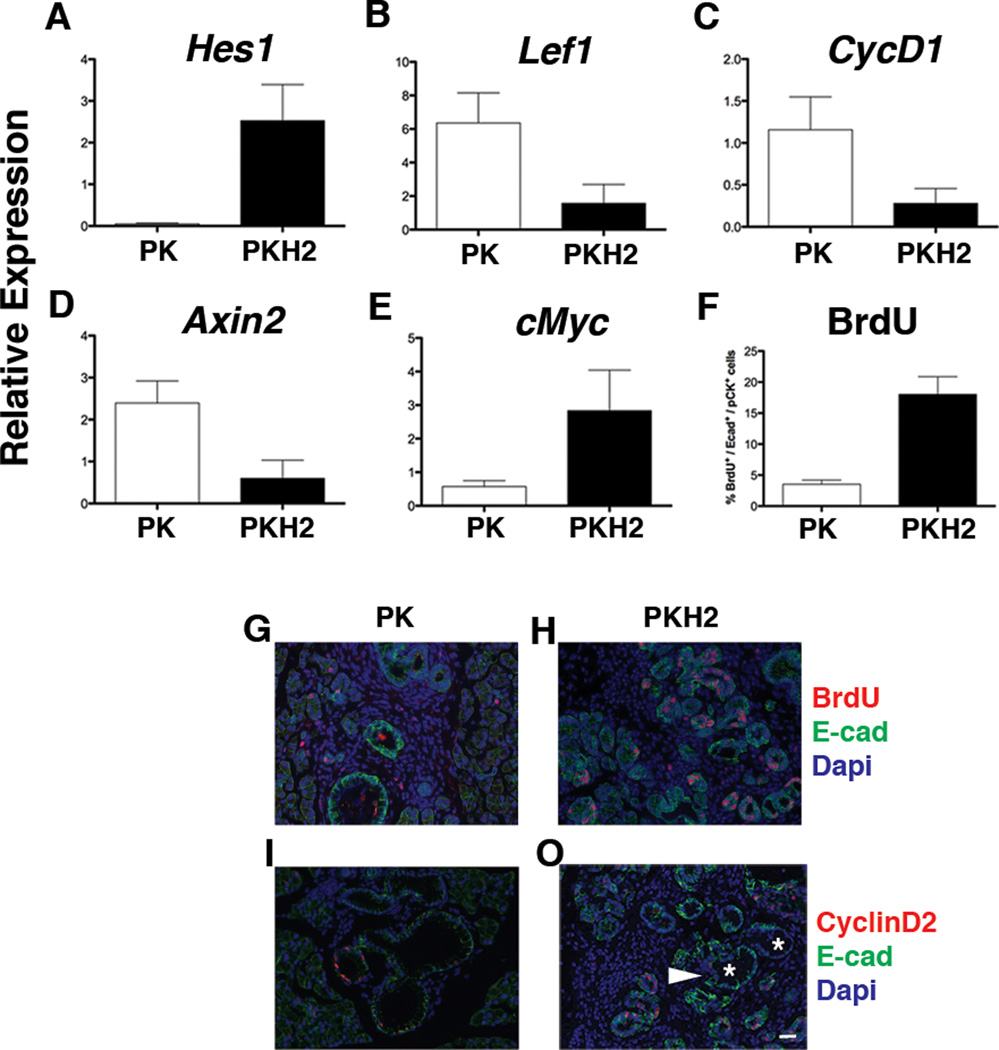

Low Wnt pathway activity in PKH2 mice

Notch and Wnt-signaling pathways are reactivated during PanIN formation. Expression of the Notch target gene Hes1 was significantly higher in the PKH2 pancreas compared to the age matched PK cohort (Figure 3A). In addition, some targets of Wnt/β-catenin pathway, such as Lef1 (Figure 3B), CyclinD1 (Figure 3C), and Axin-2 (Figure 3D) were found to be expressed at lower levels in the PKH2 pancreas. In contrast, the expression of another Wnt-target, cMyc, was substantially higher in the PKH2 pancreas (Figure 3E).

Figure 3.

Decreased Wnt signaling in PKH2 pancreas. qRT-PCR analysis of RNA extracted from 3 months old PK and PKH2 whole pancreas shows higher Notch activity as evident by upregulation of Hes1 (A) and down regulation of Wnt-target genes in PKH2 pancreas (n=5 for each cohort). Bars represent gene expression (mean ± SE) relative to GAPDH. (B–E) Highly proliferative metaplastic PKH2 ducts. (F–J) Quantification of the proliferation rate showed a four-fold increase in BrdU incorporation in the PKH2 metaplastic ducts (F). Immunofluorescent analyses of 3 month old PK (G, I) and PKH2 (H, J) pancreas using antibodies against E-cadherin and BrdU (G, H) or E-cadherin and CyclinD2 (I, J) showed few CyclinD2+ or BrdU+ cells within PKH2 ducts (arrowhead) but not in mPanINs (Asterisks). Scale bar 20µm.

Highly proliferative metaplastic ducts in PKH2 mice

PKH2 pancreata have a higher incidence of ADM and PanIN lesions at earlier time points (Figure 2A). We thus quantified the proliferation rate in the lesions of both PK and PKH2 mice. Interestingly, despite an overall four-fold increased BrdU+ cell number in the PKH2 pancreatic epithelium (Figure 3F), the increased proliferative rate was more prominent among the metaplastic ducts, whereas cells within the PanINs were mostly BrdU-negative (Figure 3G, H). In addition, compared to age matched PK, the PKH2 PanINs contained fewer CyclinD2-expressing cells (Figure 3I, J).

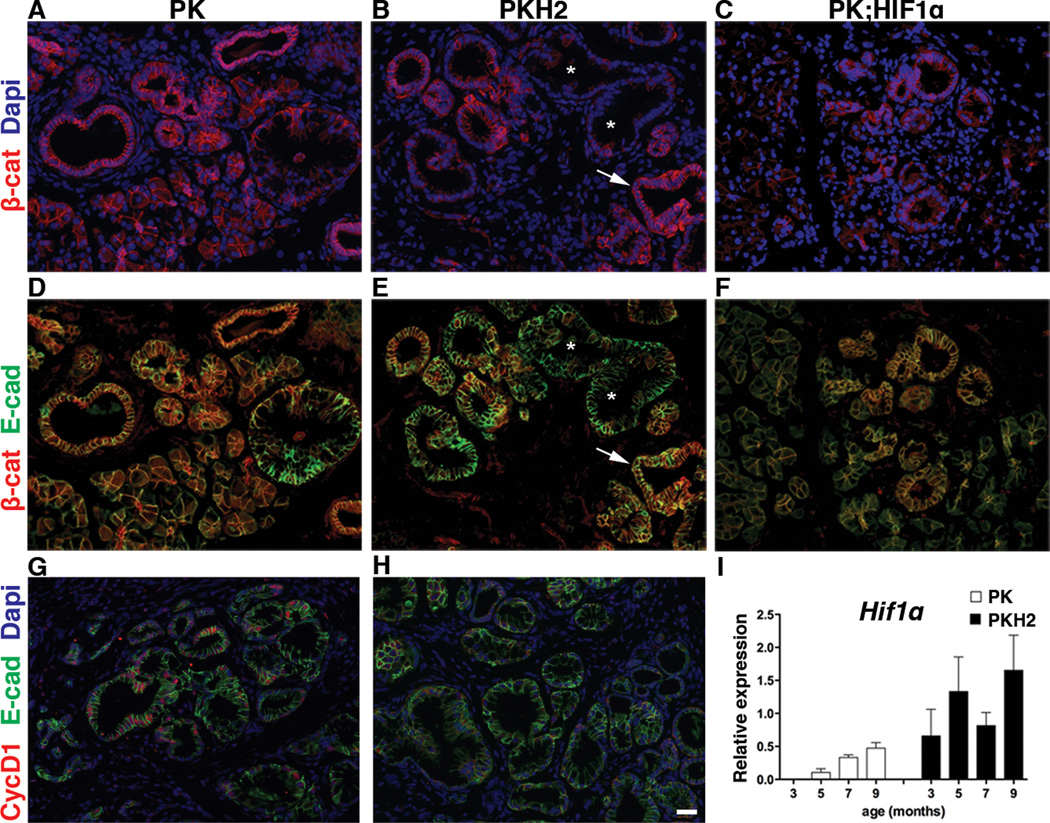

Impaired β-Catenin signaling in PKH2 PanINs

Several studies have highlighted an important role for Wnt/β-catenin signaling in PDAC (4, 19–21). Thus, the observed downregulation of Wnt-pathway in PKH2 mice, encouraged us to study β-catenin protein expression in PK and PKH2 pancreas (Figure 4). As expected, immunostaining in PK mice revealed that β-catenin was present in all epithelial cells, including metaplastic ducts and PanINs (Figure 4A, D). In contrast, in PKH2 pancreata β-catenin was absent in the vast majority of PanINs, although it could be detected in the endocrine and acinar cells, as well as in the normal and metaplastic ducts (Figure 4B, E). Expression of E-cadherin confirmed the epithelial characteristics of the β-catenin-deficient PKH2 PanIN cells (Figure 4E). The deficiency of β-catenin was related neither to the age of the mice, nor to the PanIN stage (Supplemental Figure 3). The absence of CyclinD1 in PKH2 PanINs, further confirmed the impairment of β-catenin/Wnt-signaling in these animals (Figure 4G, H).

Figure 4.

PanIN-specific loss of β-catenin in PKH2 pancreas. (A–F) Immunostaing for β-catenin (A–C) or β-catenin and E-cadherin (D–F) of 3 months old PK (A, D), PKH2 (B, E) or PK;HIF1α pancreas showed absence of β-catenin in PKH2 mPanINs. Asterisks mark β-caten-negative mPanINs, arrows highlight an adjacent duct with normal β-catenin distribution. (G, H) Immunofluorescent analyses using antibodies against E-cadherin and CyclinD1 of 3 months old PK (G) and PKH2 (H) pancreas confirmed impaired Wnt-signaling in PKH2 mPanINs. Scale bar 20µm. Compensatory Hif1α expression in the PKH2 pancreas. (I) qRT-PCR analysis of RNA extracted from 3–9 months old PK and PKH2 whole pancreas (n=5 for each cohort) showed an overall higher Hif1α gene expression in PKH2 pancreas. Bars represent gene expression (mean ± SE) relative to GAPDH.

The phenotype in PKH2 mPanINs is independent of HIF1α

Deletion of Hif1α often leads to enhanced Hif2α expression, and similarly Hif2α deletion results in higher levels of Hif1α expression (22). We thus speculated that the phenotype observed in PKH2 mice could be due to compensatory expression of Hif1α rather than deletion of Hif2α. To investigate this hypothesis, pancreatic Hif1α gene expression was analyzed in samples obtained from 3–12 month-old PK and PKH2 mice (Figure 4I). We found that Hif1α transcript levels were undetectable in 3 month-old PK pancreas, but gradually increased in the older animals, confirming what previous studies had reported in human PanINs (11). In contrast, the deletion of Hif2α in the PKH2 pancreas leads to an accelerated and higher Hif1α expression (Figure 4I). To further determine whether the absence of β-catenin in Hif2α-deficient PanINs was primarily the result of HIF1α function, we bred the PK mice into the Rosa26-HA-HiF1-dPA strain (15). Our analyses of 3 month old Ptf1aCre;KrasG12D;R26Hif1α pancreas showed normal expression of β-catenin in PanINs (Figure 4C, F). These data indicate that the absence of β-catenin in the PKH2 PanINs is likely to be independent of the ectopic presence of HIF1α in the Hif2α-deficient pancreas.

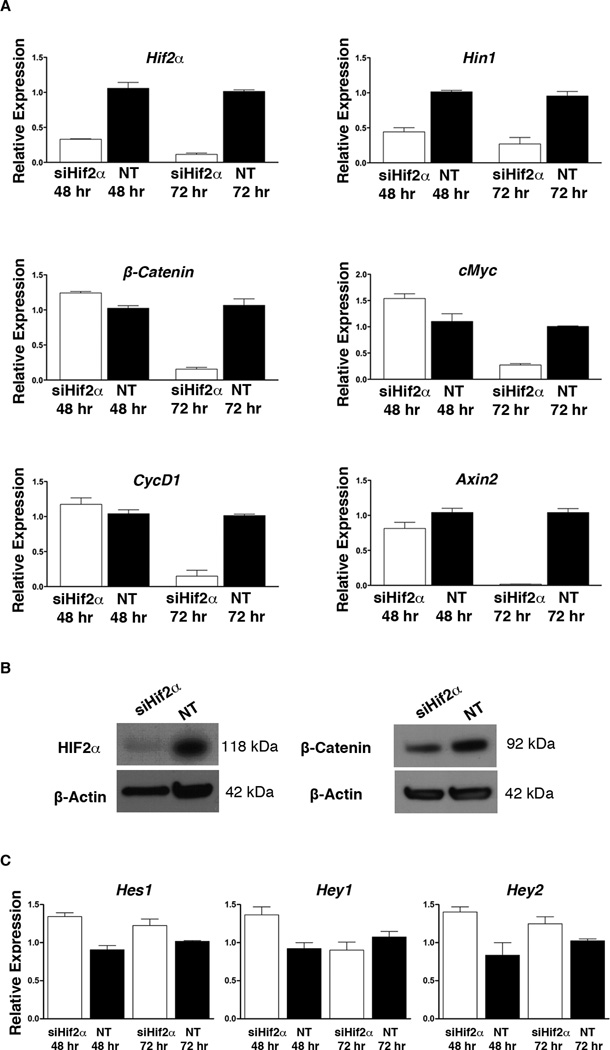

HIF2α regulates β-catenin levels at the level of transcription

Our transgenic studies strongly suggest that the presence of β-catenin in PanINs is correlated with HIF2α activity. To determine whether loss of Hif2α affects β-catenin at a transcriptional and/or translational level, CKP cells were treated with Hif2α siRNA (siHif2α) and harvested after 48 or 72 hours (Figure 5). The CPK cell line is a mouse pancreatic cancer cell line isolated from PdxCre;KrasG12D;p53+/− tumors. As shown in figure 4A, HIF2α, and β-catenin are both expressed in this cell line at basal level. After siHif2α treatment, we detected a 60% reduction in Hif2α mRNA at 48 hours, which was further reduced to >95% at 72 hours. Consistently, the expression of Hin1, which is a direct HIF2α target gene (23), was also reduced 50% at 48 hours and 75% at 72 hours (Figure 5A). Interestingly, β-catenin levels and downstream Wnt-target genes CyclinD1 and cMyc were not appreciably affected after 48 hours, but showed significant reduction after 72 hours (Figure 5A). Western blot analysis also confirmed reduction of β-catenin protein levels first 72 hours after siHIF2α treatment (Figure 5B, & Supplemental Figure 4A, B). Overall, our results demonstrate that HIF2α regulates the transcription of β-catenin in pancreatic lesions.

Figure 5.

HIF2α promotes β-catenin expression. (A) qRT-PCR analyses for expression of Hif2α, Hin1, Hes1, Hey1, Hey2, β-catenin and some Wnt-target genes in CKP cells treated with Hif2α-siRNA (siHif2α) or non-target siRNA (NT). Silencing of Hif2α resulted in decreased β-catenin transcript levels specifically after 72 hours. (B) Western blot analyses for HIF2α and β-catenin confirmed silencing of the Hif2α gene and the subsequent downregulation of β-catenin at 72 hours. (C) Silencing of Hif2α did not have any effect on Notch activity. Bars represent gene expression (mean ± SE) relative to GAPDH, (n=5).

The higher PanIN incidence in PKH2 mice is associated with down-regulation of Smad4

Given the oncogenic nature of wnt-signaling, we looked for other mechanisms that could account for the accelerated and higher PanIN incidence observed in PKH2 mice. Active Notch pathway promotes epithelial transformation and PanIN progression in human and mouse (24, 25). As shown in figure 3, Hes1 expression was significantly higher in the PKH2 pancreas. However, we could not detect any changes on mRNA level for Notch targets such as Hes1, Hey1, and Hey2 following Hif2α silencing in CKP cells (Figure 5C).

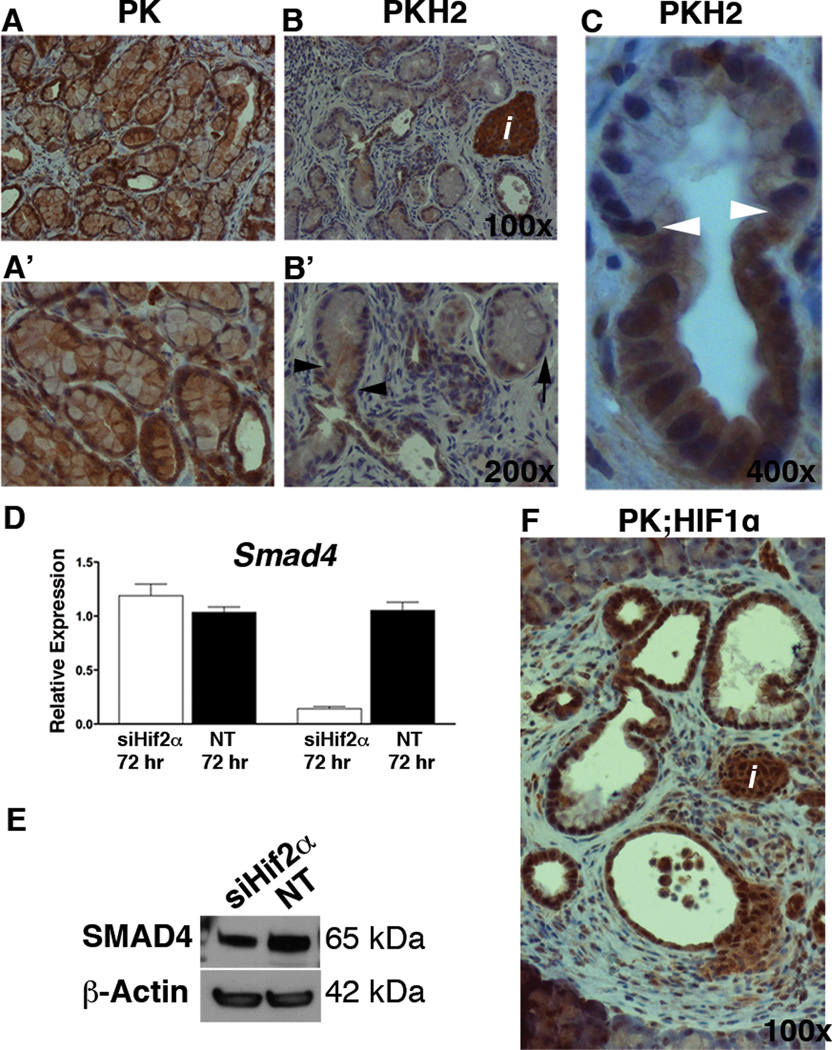

Loss of Smad4 is a relatively late event during PanIN development (26), and inactivation of Smad4 in the setting of Kras-driven neoplasia is associated with an acceleration in pancreatic tumorigenesis (27, 28). Our immunohistochemical analyses showed that SMAD4 was present in the normal- as well as in the metaplastic ducts in both the PK (Figure 6A, & Supplemental Figure 5A) and the PKH2 pancreas (Figure 6B, C, & Supplemental Figure 5B–D). As expected, early PanINs in PK mice expressed Smad4 (Figure 5A, & Supplemental Figure 5A) however, the PanINs in the Hif2α-mutant pancreas lacked Smad4 expression (Figure 6B, C, & Supplemental Figure 5B–D). The observed loss of SMAD4 in PKH2 pancreas occurred concomitantly with transformation of metaplastic ducts to PanIN1A (Figure 6B’, C). Similarly to β-catenin, the loss of Smad4 in the Hif2α-deficient lesions was not age-dependent (Supplemental Figure 5B–D).

Figure 6.

Loss of Smad4 in PKH2 mPanINs. (A–C) Immunohistochemical analyses of 5 month old PK (A), or PKH2 (B, C) pancreas using antibodies against SMAD4. A’ and B’ are higher magnifications of A and B. Arrowheads in B’ and C highlight the transition point from duct to PanIN in PKH2 pancreas which is associated with the loss of Smad4 expression. Arrow in B marks a Smad4 PanIN cell. Scale bars 20µm. HIF2α promotes Smad4 expression. (D) qRT-PCR analysis for expression of Hif2α, Smad4 in CKP cells treated with Hif2α-siRNA (siHif2α) or non-target siRNA (NT). Silencing of Hif2α in CKP cells resulted in decreased Smad4 transcript levels (D) as well as protein levels (E) after 72 hours (n=5). Bars represent gene expression (mean ± SE) relative to GAPDH. (F) SMAD4 could be detected in islets, ducts and PanINs in the PK;HIF1α pancreas.

To verify whether the expression of Smad4 is dependent on HIF2α, we analyzed Smad4 expression in siHif2α-treated and control CPK cells (Figure 6D). No significant changes could be detected in Smad4 expression at 48 hours. However, at 72 hours both Smad4 mRNA and protein levels had reduced significantly compared to controls, confirming that HIF2α also regulates Smad4 transcription (Figure 6D, E & Supplemental Figure 4C). Finally, the presence of SMAD4 in Ptf1aCre;KrasG12D;R26Hif1α PanINs confirmed that the loss of SMAD4 in PKH2 PanINs is HIF2α-dependent (Figure 6F).

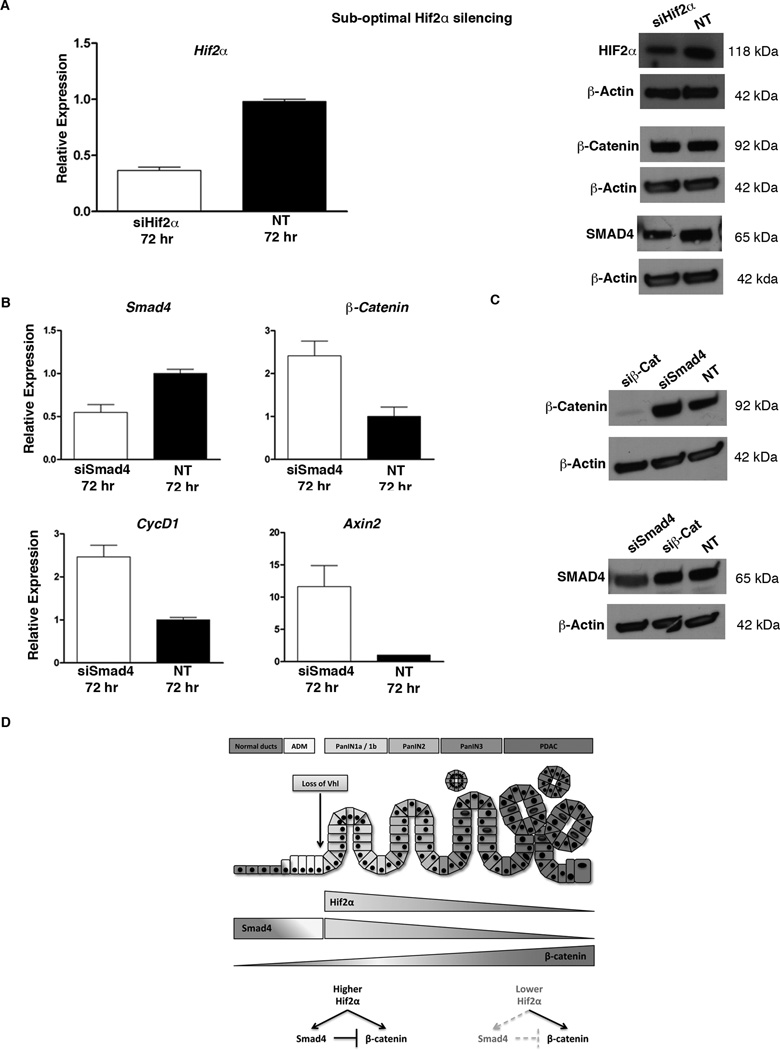

SMAD4 inhibits β-catenin transcription in pancreatic cancer cells

We have shown that inactivation of Hif2α (95% reduction in siHif2α-treated cells or complete inactivation in the PKH2 pancreas) leads to significant reduction of SMAD4 and β-catenin levels. These data suggest that the observed decrease in HIF2α levels in more advanced lesions (Figure 1C, F) would result in reduced Smad4 and β-catenin expression. While this finding is consistent with Smad4 expression during PanIN progression (26), it is in contrast to what has been proposed for the β-catenin activity (4). However, this discrepancy could reflect a dose dependent transcriptional activity of HIF2α. To determine whether HIF2α regulates Smad4 and β-catenin expression in a dose dependent manner, we silenced Hif2α under sub-optimal conditions. A 60% reduction in Hif2α mRNA levels 72 hours after siHif2α-treatment resulted in decreased SMAD4, but had no effect on β-catenin expression (Figure 7A, & Supplemental Figure 4D).

Figure 7.

HIF2α regulates Smad4 expression in a dose dependent manner. (A) Partial silencing of Hif2α in CKP cells leads to decreased SMAD4, but not β-catenin protein levels. β-catenin expression is suppressed by SMAD4. (B) qRT-PCR analysis for expression of Smad4, β-catenin and Wnt-target genes CyclinD1 and Axin2 in CKP cells treated with Smad4-siRNA (siSmad4), or non-target siRNA (NT). Silencing of Smad4 resulted in increased β-catenin and Wnt-targets transcripts after 72 hours, (n=5). Bars represent gene expression (mean ± SE) relative to GAPDH. (C) Western blot analyses showed that while silencing of Smad4 increased β-catenin protein levels, silencing of β-catenin (siβ-Cat) did not have any impact on Smad4 expression. (D) The proposed mechanism by which HIF2α promotes PanIN progression.

Next, we studied whether the reductions in Smad4 and β-catenin mRNA are two independent events, or if the two genes are synchronous hierarchically downstream of HIF2α. To further investigate the relation between SMAD4 and β-catenin, we silenced the expression of Smad4 (siSmad4) and β-catenin (siβ-cat) separately in CKP cells, and determined SMAD4 and β-catenin mRNA and protein expression in comparison to non-target siRNA treated cells (Figure 7B, C, & Supplemental Figure 4E). Interestingly, we found that expression of β-catenin was significantly increased in Smad4-silenced CKP cells both at the mRNA and protein levels (Figure 7B, C). Consistently, the expression of Wnt-targets such as Axin2, and CyclinD1, were also higher in siSmad4-treated CKP cells (Figure 7B). On the other hand, silencing of β-catenin did not have any effect on Smad4 expression at mRNA (data not shown) and protein level (Figure 7C).

Overall, our findings indicate that in pancreatic cancer cells HIF2α promotes β-catenin and SMAD4 expression independently. In addition, HIF2α regulates Smad4 expression in a dose dependent manner, and the expression of β-catenin is negatively regulated by SMAD4.

Discussion

The Loss of VHL and the subsequent activation of the hypoxic pathway is one of the earliest events in Kras-induced pancreatic neoplasia, and it is evident as early as in PanIN1As (10). Here, we evaluated the role of HIF2α in pancreatic carcinogenesis in vivo, and propose a molecular mechanism, which could explain the phenotype observed. Histological analysis of the PKH2 pancreata showed that loss of Hif2α significantly accelerated the onset of acinar-to-ductal metaplasia and the appearance of PanIN lesions. However, despite the increased acinar-to-ductal metaplasia and PanIN incidence early on, the subsequent PanIN progression was halted, with a predominance of low grade PanINs in the older PKH2 mice. The phenotype in PKH2 pancreas was associated with a higher Notch activity, as evident by increased Hes1 expression. Nevertheless, Hif2α silencing in CKP cells did not have any effect of Notch targets, thus it is likely that the in vivo difference could reflect higher number of PanINs in the PKH2 pancreas. The PKH2 pancreas also displayed overall lower transcript levels of Wnt-target genes, such as Axin2, lef1 and CyclinD1, but higher levels of cMyc. However, increased expression levels of cMyc is a common emergent phenotype in most neoplastic cells and in addition, cMyc is expressed by the acinar cells (29).

Recent studies imply that Wnt-signaling must be tuned to appropriate levels at key time points during transformation to specify the PanIN-PDAC lineage (3, 4). Here, we report loss of β-catenin expression and impaired wnt-signaling in PKH2 PanINs. Of note, β-catenin was not uniformly absent in all Hif2α mutant PanIN cells. Indeed, in some lesions only a sub-population of cells was β-catenin-negative, while in few other lesions all cells were β-catenin-positive. This finding is consistent with the absence of HIF2α in a sub-population of PanIN cells. Similar to β-catenin, In the PKH2 mice, SMAD4 could be detected in the metaplastic ducts, however its expression was lost in early PanINs. Together, these findings suggest that the accelerated and higher PanIN incidence seen in the PKH2 pancreas may be due to the absence of SMAD4. At the same time, the impaired PanIN progression could be the result of β-catenin loss.

Our in vitro studies revealed that, like β-catenin, Smad4 was also regulated by HIF2α at the transcriptional level. However, the lack of HIF-binding motifs in the regulatory elements of β-catenin or Smad4 would suggest that HIF2α likely does not directly regulate β-catenin or Smad4 gene expression. Furthermore, while silencing of Hif2α in CKP cells resulted in decreased transcript levels of Hin1 (a direct HIF2α target) within 48 hours, any significant decrease in β-catenin or Smad4 gene expression was detected only after 72 hours.

In addition to directly binding to DNA and promote transcription of target genes, HIFs may also regulate transcription through heterodimer-mediated protein-protein interaction with other transcription factors (30). For example, HIF2α accentuate MAX/MYC or β-catenin/TCF-driven transcription (31, 32). Thus, we speculate that HIF2α may be part of DNA-binding protein complexes that regulate β-catenin and Smad4 expression. More detailed analyses are needed to better understand the mechanisms by which β-catenin and Smad4 expressions are regulated by HIF2α.

To determine whether loss of β-catenin was the result of HIF1α expression, we generated a mouse in which HIF1α was expressed in conjunction with oncogenic Kras in the pancreas. The presence of β-catenin and SMAD4 in the PanIN lesions in the Ptf1aCre;KrasG12D;R26Hif1α pancreas confirmed that the expression profile observed in PKH2 PanINs is the result of HIF2α loss. Smad4 deficiency in the setting of oncogenic Kras expression is associated with increased proliferation of the neoplastic epithelium (27, 28). Consistently, PKH2 mice displayed a higher proliferative rate among metaplastic ducts compared to their PK littermates. However, the PanINs in PKH2 mice incorporated significantly less BrdU, likely due to the impaired wnt-signaling and the absence of CyclinD1.

Based on the collective results of our in vivo and in vitro experiments we propose that HIF2α modulates Wnt-signaling during mPanIN progression, by maintaining appropriate levels of Smad4 and β-catenin (Figure 7D). Transformation of metaplastic ducts into PanIN1A lesions is associated with downregulation of VHL, which leads to accumulation of high levels of HIF2α in the early PanINs. The abundance of HIF2α at this stage promotes expression of both Smad4 and β-catenin in PanINs. SMAD4 prevents overexpression of β-catenin, thus maintaining β-catenin levels at the necessary threshold required for PanIN progression (4). This finding is consistent with recent reports showing that SMAD4 β-catenin expression is negatively regulated by SMAD4 (33, 34). As PanINs progress, the levels of HIF2α decline. Lower levels of HIF2α maintain β-catenin expression, but may not be sufficient to promote Smad4 expression. In the absence of SMAD4, β-catenin/Wnt-signaling levels reach the necessary threshold, required for PanIN-PDA transformation. It stands to reason that HIF2α may interact with two separate transcriptional factors, both competing for binding HIF2α to drive β-cateinin or Smad4 transcription, respectively. It is tempting to speculate that the complex promoting β-catenin may have higher affinity to bind HIF2α, and as the result being less sensitive to HIF2α levels present in the PanIN cell. This model, while intriguing, requires validation from more precise biophysical studies. Future studies should elucidate the mechanisms that distinguish the tumor promoting, or tumor suppressive activities of HIF2α protein during pancreatic tumorigenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Drs. S.D. Leach (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD), and S.F. Konieczny (Purdue University, W. Lafayette, IN) for their insightful comments.

Grant Support

This work was supported by the Concern Foundation (FE), The Cochrane-Weber endowed Fund in Diabetes Research (FE, AC), The Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC (FE), and NIH 5R01EY019721 (GHF).

Footnotes

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Author Contributions: FE and AC designed research; AC, JAR, and EW performed research; LJD and GHF generated the Hif2α-floxed mice; MTL provided the primary cell line; FE, AC, VF, DJH, PSM, and GKG analyzed the data; FE wrote the paper.

References

- 1.Maitra A, Fukushima N, Takaori K, Hruban RH. Precursors to invasive pancreatic cancer. Adv Anat Pathol. 2005;12(2):81–91. doi: 10.1097/01.pap.0000155055.14238.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bardeesy N, DePinho RA. Pancreatic cancer biology and genetics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(12):897–909. doi: 10.1038/nrc949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris JPt, Wang SC, Hebrok M, KRAS Hedgehog. Wnt and the twisted developmental biology of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(10):683–695. doi: 10.1038/nrc2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris JPt, Cano DA, Sekine S, Wang SC, Hebrok M. Beta-catenin blocks Kras-dependent reprogramming of acini into pancreatic cancer precursor lesions in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(2):508–520. doi: 10.1172/JCI40045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raval RR, Lau KW, Tran MG, Sowter HM, Mandriota SJ, Li JL, et al. Contrasting properties of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) and HIF-2 in von Hippel-Lindau-associated renal cell carcinoma. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(13):5675–5686. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.13.5675-5686.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu CJ, Iyer S, Sataur A, Covello KL, Chodosh LA, Simon MC. Differential regulation of the transcriptional activities of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF-1alpha) and HIF-2alpha in stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(9):3514–3526. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.9.3514-3526.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordan JD, Simon MC. Hypoxia-inducible factors: central regulators of the tumor phenotype. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17(1):71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamura T, Sato S, Iwai K, Czyzyk-Krzeska M, Conaway RC, Conaway JW. Activation of HIF1alpha ubiquitination by a reconstituted von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(19):10430–10435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190332597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohh M, Park CW, Ivan M, Hoffman MA, Kim TY, Huang LE, et al. Ubiquitination of hypoxia-inducible factor requires direct binding to the beta-domain of the von Hippel-Lindau protein. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2(7):423–427. doi: 10.1038/35017054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin F, Shi J, Liu H, Hull ME, Dupree W, Prichard JW, et al. Diagnostic utility of S100P and von Hippel-Lindau gene product (pVHL) in pancreatic adenocarcinoma-with implication of their roles in early tumorigenesis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32(1):78–91. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31815701d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Angst E, Sibold S, Tiffon C, Weimann R, Gloor B, Candinas D, et al. Cellular differentiation determines the expression of the hypoxia-inducible protein NDRG1 in pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(3):307–313. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kizaka-Kondoh S, Itasaka S, Zeng L, Tanaka S, Zhao T, Takahashi Y, et al. Selective killing of hypoxia-inducible factor-1-active cells improves survival in a mouse model of invasive and metastatic pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(10):3433–3441. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawaguchi Y, Cooper B, Gannon M, Ray M, MacDonald RJ, Wright CV. The role of the transcriptional regulator Ptf1a in converting intestinal to pancreatic progenitors. Nat Genet. 2002;32(1):128–134. doi: 10.1038/ng959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hingorani SR, Petricoin EF, Maitra A, Rajapakse V, King C, Jacobetz MA, et al. Preinvasive and invasive ductal pancreatic cancer and its early detection in the mouse. Cancer Cell. 2003;4(6):437–450. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim WY, Safran M, Buckley MR, Ebert BL, Glickman J, Bosenberg M, et al. Failure to prolyl hydroxylate hypoxia-inducible factor alpha phenocopies VHL inactivation in vivo. EMBO J. 2006;25(19):4650–4662. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Criscimanna A, Speicher JA, Houshmand G, Shiota C, Prasadan K, Ji B, et al. Duct cells contribute to regeneration of endocrine and acinar cells following pancreatic damage in adult mice. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(4):1451–1462. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.003. 1462 e1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mazur PK, Einwachter H, Lee M, Sipos B, Nakhai H, Rad R, et al. Notch2 is required for progression of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and development of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(30):13438–13443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002423107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang R, Loux T, Tang D, Schapiro NE, Vernon P, Livesey KM, et al. The expression of the receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) is permissive for early pancreatic neoplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(18):7031–7036. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113865109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heiser PW, Cano DA, Landsman L, Kim GE, Kench JG, Klimstra DS, et al. Stabilization of beta-catenin induces pancreas tumor formation. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(4):1288–1300. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.06.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pasca di Magliano M, Biankin AV, Heiser PW, Cano DA, Gutierrez PJ, Deramaudt T, et al. Common activation of canonical Wnt signaling in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(11):e1155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang L, Heidt DG, Lee CJ, Yang H, Logsdon CD, Zhang L, et al. Oncogenic function of ATDC in pancreatic cancer through Wnt pathway activation and beta-catenin stabilization. Cancer Cell. 2009;15(3):207–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Menrad H, Werno C, Schmid T, Copanaki E, Deller T, Dehne N, et al. Roles of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha (HIF-1alpha) versus HIF-2alpha in the survival of hepatocellular tumor spheroids. Hepatology. 2010;51(6):2183–2192. doi: 10.1002/hep.23597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mazumdar J, Hickey MM, Pant DK, Durham AC, Sweet-Cordero A, Vachani A, et al. HIF-2alpha deletion promotes Kras-driven lung tumor development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(32):14182–14187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001296107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyamoto Y, Maitra A, Ghosh B, Zechner U, Argani P, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, et al. Notch mediates TGF alpha-induced changes in epithelial differentiation during pancreatic tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2003;3(6):565–576. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De La OJ, Murtaugh LC. Notch and Kras in pancreatic cancer: at the crossroads of mutation, differentiation and signaling. Cell Cycle. 2009;8(12):1860–1864. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.12.8744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilentz RE, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Argani P, McCarthy DM, Parsons JL, Yeo CJ, et al. Loss of expression of Dpc4 in pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia: evidence that DPC4 inactivation occurs late in neoplastic progression. Cancer Res. 2000;60(7):2002–2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bardeesy N, Cheng KH, Berger JH, Chu GC, Pahler J, Olson P, et al. Smad4 is dispensable for normal pancreas development yet critical in progression and tumor biology of pancreas cancer. Genes Dev. 2006;20(22):3130–3146. doi: 10.1101/gad.1478706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kojima K, Vickers SM, Adsay NV, Jhala NC, Kim HG, Schoeb TR, et al. Inactivation of Smad4 accelerates Kras(G12D)-mediated pancreatic neoplasia. Cancer Res. 2007;67(17):8121–8130. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonal C, Thorel F, Ait-Lounis A, Reith W, Trumpp A, Herrera PL. Pancreatic inactivation of c-Myc decreases acinar mass and transdifferentiates acinar cells into adipocytes in mice. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(1):309–319. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.015. e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dang CV, Kim JW, Gao P, Yustein J. The interplay between MYC and HIF in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(1):51–56. doi: 10.1038/nrc2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gordan JD, Bertout JA, Hu CJ, Diehl JA, Simon MC. HIF-2alpha promotes hypoxic cell proliferation by enhancing c-myc transcriptional activity. Cancer Cell. 2007;11(4):335–347. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi H, Chun YS, Kim TY, Park JW. HIF-2alpha enhances beta-catenin/TCF-driven transcription by interacting with beta-catenin. Cancer Res. 2010;70(24):10101–10111. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li J, Huang X, Xu X, Mayo J, Bringas P, Jr, Jiang R, et al. SMAD4-mediated WNT signaling controls the fate of cranial neural crest cells during tooth morphogenesis. Development. 2011;138(10):1977–1989. doi: 10.1242/dev.061341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freeman TJ, Smith JJ, Chen X, Washington MK, Roland JT, Means AL, et al. Smad4-mediated signaling inhibits intestinal neoplasia by inhibiting expression of beta-catenin. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(3):562–571. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.11.026. e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.