Abstract

Measures of treatment integrity are needed to advance clinical research in general and are viewed as particularly relevant for dissemination and implementation research. Although some efforts to develop such measures are underway, a conceptual and methodological framework will help guide these efforts. The purpose of this article is to demonstrate how frameworks adapted from the psychosocial treatment, therapy process, healthcare, and business literatures can be used to address this gap. We propose that components of treatment integrity (i.e., adherence, differentiation, competence, alliance, client involvement) pulled from the treatment technology and process literatures can be used as quality indicators of treatment implementation and thereby guide quality improvement efforts in practice settings. Further, we discuss how treatment integrity indices can be used in feedback systems that utilize benchmarking to expedite the process of translating evidence-based practices to service settings.

Keywords: children's mental health, dissemination and implementation research, evidence-based treatments, treatment integrity

Approximately 15 million youth receive mental health treatment each year in the United States (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 1999); the costs of mental health services for youth have been estimated at almost 10 billion US dollars in 2006 (Soni, 2009). Despite this clear and pressing need, many youth with significant mental health problems remain underserved or unserved (Fulda, Lykens, Bae, & Singh, 2009; Kataoka, Zhang, & Wells, 2002). A multitude of evidence-based treatments (EBTs) for youth emotional and behavioral problems is associated with reduced youth symptomatology posttreatment in efficacy trials (Chorpita & Daleiden, 2009; McLeod & Weisz, 2004). Unfortunately, findings from effectiveness research in practice settings (e.g., community clinics), where most youth actually receive mental health services, have been mixed (e.g., Clarke et al., 2005; Southam-Gerow et al., 2010; Weisz, Jensen-Doss, & Hawley, 2006; Weisz et al., 2012). These mixed findings raise questions about the transportability of EBTs. Moreover, they partly contributed to the development of a field of study called dissemination and implementation (D&I) science (Chambers, Ringeisen, & Hickman, 2005; Fixsen, Naoom, Blase, Friedman, & Wallace, 2005), with a primary focus on identifying the methods needed to improve community-based services by leveraging the considerable scientific evidence base on psychological treatments.

This article focuses upon one important domain of study within D&I research: treatment integrity research (e.g., Perepletchikova & Kazdin, 2005). In this article, we make the case that treatment integrity models, methods, and measurement will be a key component for D&I research and ultimately for the success of promoting an evidence-based approach to provide services to youth and their families in a variety of practice contexts. Specifically, we will describe how the components of treatment integrity represent the key domains from which to identify quality indicators (i.e., a measure of the quality of mental health care) for the implementation of EBTs within mental health service systems. As described in an earlier article in this series (Southam-Gerow & McLeod, 2013), treatment integrity is a multidimensional construct including (a) extensiveness of the delivery of specific therapeutic interventions considered integral to the treatment model(s) intended; (b) extent to which the treatment includes a variety of other therapeutic interventions that are not part of the intended model; (c) the quality of treatment delivery; and (d) the relational aspects of treatment delivery (i.e., client-therapist alliance, level of client involvement).

Most past work related to treatment integrity has focused on ensuring a particular treatment was delivered as intended in clinical trials (Perepletchikova & Kazdin, 2005; Weisz, Jensen-Doss, & Hawley, 2005). More recently, this research has begun to focus upon ways to inform the optimization of treatment programs, for example by understanding how different components of the programs promote positive outcomes (e.g., Hogue et al., 2008). Although these directions represent important applications of treatment integrity research, in this article, we identify another way treatment integrity models and methods can be applied to the goals of D&I research. Specifically, we make the case that the components of treatment integrity can be viewed as key domains from which to identify quality indicators for the implementation of EBTs.

To make the case for the use of treatment integrity in this way, we will consider models and findings from the treatment development, health services, business, industrial/organizational psychology, and education literatures. We begin with a discussion of some new models of treatment development and evaluation to demonstrate how (a) D&I research is linked to more traditional treatment development models and (b) treatment integrity has relevance to D&I research.

A FOCUS ON TREATMENT IMPLEMENTATION

Dissemination and implementation researchers have asserted that the treatment development and evaluation process (i.e., the stage model for psychotherapy treatment development; Carroll & Nuro, 2002) needs to include steps that assess fit between EBTs and different practice contexts (Schoenwald & Hoagwood, 2001). Toward this end, D&I research focuses upon transportability (i.e., focused upon the processes involved in moving an EBT from a research setting into a community setting) and dissemination (i.e., how to distribute and sustain an EBT) research. Relevant to this article, an important outcome in transportability and dissemination research is the integrity of treatment implementation1—the extent to which the elements of an EBT are delivered according to the treatment model (Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, 2001; Schoenwald et al., 2011). Thus, assessing the extent and quality of treatment implementation is a key research goal, as this allows D&I researchers to determine whether “failure” to produce a desired clinical outcome was due to the potency/applicability of the EBT (i.e., implementation was sufficient, so the EBT is not effective; thus, adapt the EBT or select an alternative intervention) or some quality/aspect of its implementation (i.e., implementation was insufficient; thus, engage in staff training; e.g., Schoenwald et al., 2011). Thus, treatment integrity research represents an important outcome domain for D&I science.

A conceptual and methodological framework is needed to guide efforts to characterize the important components of treatment implementation in practice settings. With the rest of this article, we propose a new framework that blends existing models found in the psychosocial treatment development, health services, business, industrial and organizational psychology, and education literatures. Specifically, we cover three topics. First, we describe the quality of care model (e.g., Donabedian, 1988; McGlynn, Norquist, Wells, Sullivan, & Liberman, 1988) as a framework to guide understanding of how factors at different levels of the service system can influence treatment implementation. Next, we make the case for treatment integrity measures as quality indicators of treatment implementation. Finally, we describe how feedback and benchmarking approaches from the business literature can be used to guide quality improvement to promote more precise transmission of EBTs to practice settings.

QUALITY INDICATORS FOR TREATMENT IMPLEMENTATION IN CHILDREN'S MENTAL HEALTH CARE

Quality of care research seeks to improve the outcomes of individuals who access care across a variety of healthcare settings (Burnam, Hepner, & Miranda, 2009; Donabedian, 1988; McGlynn et al., 1988). To achieve this goal, quality of care research seeks to understand how the structural elements of healthcare settings (e.g., contextual elements of where care is provided, including attributes of settings, clients, and providers) and the processes of care (e.g., activities and behaviors associated with delivering and receiving care) influence patient outcomes (e.g., symptom reduction, client satisfaction, client functioning; Donabedian, 1988).

An important goal of quality of care research is to identify quality indicators. Healthcare quality indicators are structural or process elements that are demonstrated to lead to improvements in patient outcomes (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ], 2006). Importantly, quality indicators provide stakeholders with the means to assess, track, and monitor provider performance relative to current “best practices” (Hussey, Mattke, Morse, & Ridgely, 2007). The identification of quality indicators therefore is a necessary prerequisite for quality improvement efforts (Garland, Bickman, & Chorpita, 2010; Pincus, Spaeth-Rublee, & Watkins, 2011).

Relevant to the current article, the mental health field has yet to come to a consensus about how to define and measure quality indicators for the implementation of psychosocial treatments (Pincus et al., 2011). A primary thesis of this article is that the components of treatment integrity represent an ideal framework to guide the identification of quality indicators specifically for the implementation of EBTs. There are numerous quality indicators relevant for the processes of care in mental health2 (e.g., profit margin of a particular procedure/technique, accessibility of services, rates of treatment completion, show-rates for appointments), so careful consideration is needed when developing a framework for measuring quality indicators specifically focused upon treatment implementation. Therefore, to make our case, it is important to review past efforts to define quality indicators for mental health processes.

Background on Quality Indicators

Typically, quality indicators are identified through literature reviews and expert consensus. To be considered a quality indicator, a structural or process element of the healthcare system must augment client outcomes (AHRQ, 2006). In primary/medical health care, a number of different frameworks for identifying and evaluating quality indicators are used. As one example, the AHRQ described an evaluation framework for identifying a set of quality indicators (Hussey et al., 2007), including face validity (i.e., does the indicator gauge an aspect of care viewed as important and within the control of the provider or public health system) and lack of “perverse” incentives (i.e., leads to actual quality improvement vs. incentivizing performance reporting and/or avoiding clients/patients who might risk lower scores on the indicator). However, efforts to identify and evaluate quality indicators in mental/behavioral health care are not as advanced (Pincus et al., 2011).

Some researchers have proposed quality indicators for mental health care. For example, Noser and Bickman (2000) identified a set of quality indicators for children's mental health. The authors relied upon guidelines set forth by healthcare organizations (e.g., Center for Mental Health Services; Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Uniform Services) to identify three quality indicators: (a) the client–therapist relationship, (b) parent involvement in treatment, and (c) parent and child satisfaction with services. In a sample of youth presenting with diverse mental health needs across varied settings (e.g., outpatient to residential services), the authors found mixed support for the relation between the quality indicators and client outcomes. The child–therapist relationship was the best and most consistent predictor of outcomes, although the magnitude of the relation was small.

A few years later, Zima et al. (2005) engaged in an effort to identify quality indicators for outpatient mental health care for children diagnosed with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, and major depression. To identify the quality indicators, the authors relied upon the literature, clinical opinion, and expert consensus. Six relevant domains of quality indicators were identified: (a) completeness of initial clinical assessment, (b) appropriate linkage to other services, (c) following basic treatment principles, (d) providing appropriate psychosocial treatment, (e) initiating medication referral, and (f) safety. To quantify the indicators, medical records of 813 children who received at least three months of outpatient care across California were coded. Adherence to the quality indicators varied across the six domains. Psychosocial and medication treatments fared best, whereas linkage to other services and safety relevant to medication-specific monitoring fared the worst. Although this study was one of the first to identify a set of quality indicators for specific child emotional and behavioral problems, the psychosocial treatment indicators do not capture all facets of treatment implementation (e.g., the indicators do not assess therapist competence) or reflect dimensionality (e.g., dosage of interventions or range of therapist competence). Thus, it would be difficult to use this framework to guide quality improvement efforts aimed at improving treatment implementation in practice settings.

Pincus et al. (2011) offered another take on quality indicators for mental health and substance use care. A major goal of the authors was to inspire researchers to identify indicators that could be used to guide quality improvement efforts. Indeed, Pincus et al. noted that there is a lack of coordination and leadership within the mental health and substance use fields to identify quality indicators despite the prominence of quality of care issues since the Institute of Medicine's Quality Chasm report (Institute of Medicine, 2001). The authors proposed 10 quality indicators and encouraged stakeholders to put forward additional indicators. The quality indicators fell under six domains that were balanced across structure, process, and outcome and mapped onto the framework suggested by the Quality Chasm report: safety, effectiveness, patient-centeredness, timeliness, efficiency, and equity. For example, a proposed process quality indicator under safety included appropriate monitoring of metabolic/cardiovascular side effects for individuals receiving antipsychotic medication. As a further example, another process quality indicator under patient-centeredness focused upon the experience of care/satisfaction with care/recovery consumer survey items. Pincus et al. (2001) underscored the need not only to identify quality indicators but also to establish appropriate benchmarks for each indicator to help guide quality improvement efforts, a topic that we return to shortly in this article. Overall, the quality indicators proposed by Pincus et al. represent an important step for the field; however, the proposed quality indicators do not capture all aspects of treatment implementation and thus may not adequately characterize the processes of care that are the target for quality improvement efforts.

Treatment Integrity Components as Quality Indicators

Overall, these efforts to identify quality indicators for mental health care are laudable. However, important elements of treatment implementation relevant to D&I research have been neglected (Garland et al., 2010), an omission we propose to remedy. Specifically, we propose that the four components of treatment integrity represent domains from which to identify key quality indicators (McLeod, Southam-Gerow, & Weisz, 2009): (a) adherence, (b) differentiation, (c) competence, and (d) relational factors (alliance, client involvement). We believe that these indicators are ideal for treatment implementation and can be used in conjunction with other efforts to identify quality indicators for mental health care (e.g., Pincus et al., 2011; Zima et al., 2005).

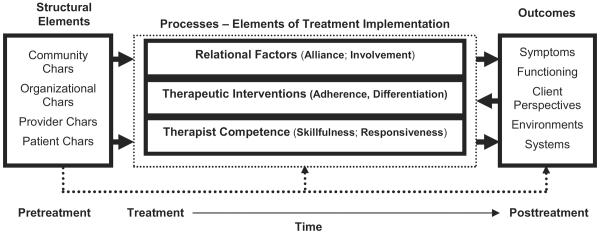

Figure 1 provides a graphical representation of our model that incorporates facets of treatment integrity models (e.g., Dane & Schneider, 1998; Hogue, 2002; Jones, Clarke, & Power, 2008) with models and findings from therapy process research (e.g., Doss, 2004; McLeod, Islam, & Wheat, in press). Placed within a quality of care framework, the left side of the model identifies the structural elements of mental healthcare settings, which includes attributes of settings (e.g., service characteristics, financial factors) where care is provided that influences (directly or moderate) treatment implementation and outcomes. The middle section represents the focus of this article and includes the components of treatment implementation. Each component captures a unique technical (i.e., what the therapist does) or relational (i.e., quality of the client–therapist relationship, level of client involvement in therapy) aspect of treatment implementation. Our dual focus on technical and relational aspects is supported by data finding that both account for variation in outcomes (see Karver, Handelsman, Fields, & Bickman, 2006; McLeod, 2011; McLeod & Weisz, 2004; Shirk & Karver, 2011) as well as the importance each aspect plays in quality of care research (Donabedian, 1988). Finally, the right portion of the diagram represents children's treatment outcomes (e.g., symptoms, functioning).

Figure 1.

Model of treatment implementation within a quality of care framework.

Here, our main focus is the middle of the figure. Treatment integrity is already an important concept in psychosocial treatment research (e.g., Kazdin, 1994; McLeod et al., 2009; Perepletchikova & Kazdin, 2005; Waltz, Addis, Koerner, & Jacobson, 1993). However, we believe a definitional shift in the focus of treatment integrity is required to use treatment integrity components as domains from which to select quality indicators for D&I research. Consistent with recent proposals in the field (e.g., Chorpita & Daleiden, 2009), we suggest that treatment integrity definitions move away from focusing upon specific manualized treatments to the broader evidence-based principles. To illustrate this point, consider that most cognitive-behavioral treatment (CBT) programs for youth anxiety involve training in cognitive strategies; however, CBT programs use a variety of different techniques (e.g., three-column technique, identification of specific cognitive errors, generation of coping thoughts) to accomplish that goal. Attempting to generate enough items to represent the therapeutic techniques designed to teach cognitive strategies as found in the dozens of CBT programs for youth anxiety (for example) would require too many items to be manageable. Coding at the practice element level (i.e., cognitive strategy) therefore may represent the ideal level of inference for D&I research, which increasingly focuses on whether treatment implementation in practice settings is consistent with evidence-based principles rather than specific programs. To maximize the utility of efforts to characterize treatment implementation in practice settings, it would be helpful if the specification and measurement of treatment integrity concepts followed the same approach. To illustrate, we next present how the different components of treatment integrity can be used as quality indicators for youth psychotherapy.

Treatment Adherence

Treatment adherence refers to the extent to which the therapist delivers the technical elements of a treatment as designed. EBTs contain a set of therapeutic interventions designed to address and remediate particular youth emotional or behavioral problems (e.g., Chorpita et al., 2011; McLeod & Weisz, 2004). Research suggests that treatment adherence is linked with outcomes in youth psychotherapy (e.g., Hogue et al., 2008; Schoenwald, Carter, Chapman, & Sheidow, 2008), although a recent meta-analysis focused primarily upon adult psychotherapy returned mixed evidence for the link between adherence and outcome (Webb, DeRubeis, & Barber, 2010).

Past definitions of adherence have typically been described at a molar level—that is, focused on whether a therapist delivers interventions from a specific EBT (e.g., delivery consistent with a specific treatment manual). However, we propose aligning the definition of treatment adherence to a more molecular understanding consistent with the distillation and matching model of Chorpita and Daleiden (2009; Chorpita, Daleiden, & Weisz, 2005; cf. Embry & Biglan, 2008). The distillation and matching model promotes an understanding of the relations between the context, or matching variables, and treatment components (i.e., the distilled techniques). The first step of the model involves distillation, a process through which an intervention is conceptualized as one possible set of discrete strategies, techniques, or components (e.g., praise, tangible rewards, time-out) that can be empirically regrouped rather than as the specific organization in the specific manual or program (e.g., parent management training). It is this first step that is most relevant to the approach we describe here. The second step, matching, involves matching the evidence for these distilled practices to client (e.g., gender, age, ethnicity), setting, or other pertinent factors as a means to guiding the selection of an appropriate, nonstandard intervention. In short, the model permits a different (and complementary) perspective on the evidence base, one that focuses on individual practices (vs. programs), thereby allowing a therapist to build a flexible treatment plan, able to focus on multiple child target problems, still rooted in empirical evidence.

The distillation and matching model enables therapists to derive “practice element profiles” that embody aspects of evidence-based protocols specific to different clinical disorders and client characteristics (Garland, Hawley, Brookman-Frazee, & Hurlburt, 2008). Instead of defining adherence as the extent to which the prescribed components of a specific treatment program are in evidence, we propose focusing on the extent to which various practice elements (i.e., a finite set of discrete principles or skills found in treatments, such as cognitive or exposure interventions) are present. For example, treatment adherence for child behavior problems could be defined as the extent to which therapists delivered specific practice elements found in the EBTs for that problem area (e.g., parent psychoeducation, rewards, time-out). This approach is consistent with the diverse manner of many practice settings (i.e., where adherence to one specific EBT for a particular problem area may not exist) and still permits a quantitative description of how consistent treatment implementation was with the evidence base for a specific child problem.

Using the distillation and matching approach to define treatment adherence has several advantages for D&I research. First, the approach is more efficient: Rather than needing a separate adherence measure for each EBT, this approach only requires a single measure that contains the practice elements (Schoenwald et al., 2011). Second, the approach is more flexible: Measurement of treatment adherence can address multiple problem areas, a need when cases at an agency include clients with comorbidities (e.g., Southam-Gerow, Chorpita, Miller, & Gleacher, 2008). Third, the approach can be applied to usual clinical care: This approach allows researchers to determine whether usual clinical care contains elements of evidence-based practice (McLeod & Weisz, 2010). Fourth, the approach can be more easily modified as the evidence based changes. For example, program-specific definitions must be changed with each iteration of a treatment manual, or with the use of a new manual. Finally, the approach is more consistent with the way that treatment occurs in most service settings. Although specific programs are available in some settings, many agencies and providers deliver diverse approaches; these agencies and providers may perceive the distillation and matching approach as more appealing, thereby increasing the chances that these strategies are actually sustained over time (Garland et al., 2010). Thus, a more flexible adherence measurement approach would have broader application across multiple service settings.

Treatment Differentiation

Treatment differentiation has been defined as the extent to which treatments under study differ along appropriate lines defined by the treatment manual(s) (Perepletchikova & Kazdin, 2005). Whereas treatment adherence assesses whether a therapist implements particular interventions, treatment differentiation evaluates whether (and “to where”) therapists deviate from that approach (Kazdin, 1994). Such checks provide valuable information regarding patterns of treatment implementation that might influence outcomes–differences in treatment implementation across sites (e.g., Hill, O'Grady, & Elkin, 1992; Hogue et al., 1998). Treatment differentiation checks can also aid understanding of whether and/or how departures from the treatment manual (i.e., treatment purity) influence outcomes (e.g., Waltz et al., 1993).

To determine whether treatment implementation departs from evidence-based practice in community-based service settings, differentiation checks must assess for a diverse array of therapeutic interventions (Garland et al., 2010; McLeod & Weisz, 2010). The ability to perform a broad assessment of protocol violations is particularly important in D&I research because clinicians working in practice settings often have diverse training backgrounds, which can increase the use of interventions from different theoretical orientations (e. g., Garland et al., 2010; McLeod & Weisz, 2010). Moreover, therapists trained to use specific EBTs may continue to use therapeutic interventions not found in the EBT (Weisz et al., 2009), and the use of such proscribed interventions may dilute treatment effects (Perepletchikova & Kazdin, 2005).

As with treatment adherence, we propose that the distillation and matching model can be used to guide the measurement of treatment differentiation in D&I research. Using this approach with treatment for child anxiety as an example, practice elements could be categorized into prescribed (e.g., exposure) and proscribed (e.g., interpretation) therapeutic interventions. As noted earlier, measuring proscribed interventions may require assessing for interventions that have not been studied extensively in the youth psychotherapy literature (e.g., client-centered, psychodynamic; McLeod & Weisz, 2004). Treatment differentiation could then be measured by the ratio of prescribed to proscribed interventions (Frank, Kupfer, Wagner, & McEachran, 1991). This approach considers how the purity of treatment implementation influences outcomes. Again, using the distillation and matching model to define treatment differentiation would allow the quality indicator to evolve with the empirical literature in contrast to defining differentiation in terms of a static program.

A differentiation measure developed with the distillation and matching model as its basis offers several important applications. First, one could gauge whether or not the additional interventions diluted or amplified treatment effects, helping to inform treatment adaptation as well as training efforts. Second, information about additional interventions may help guide intra-agency or intra-team discussion about why certain interventions are being applied. For example, imagine a seven-year-old client with a primary disruptive behavior disorder focus. Adherence measurement demonstrates use of target-relevant interventions (e.g., attending, parent psychoeducation). Differentiation measurement indicates that other interventions, such as interpretations, activity selection, and relaxation, are also present. Supervision could focus on why these additional interventions were used. In some instances, the differentiation data point to dilution of outcomes and allow a correction by the provider to focus more intently on the most relevant interventions. It is also possible that such a measurement strategy would identify outcome-augmenters—that is, practices that improve rather than dilute the outcomes of the practices for which the evidence base for the target problem is stronger.

Therapist Competence

Competence refers to the level of skill and degree of responsiveness demonstrated by the therapist when delivering treatment (Barber, Sharpless, Klostermann, & McCarthy, 2007; Carroll et al., 2000). Therapist competence is hypothesized to play an instrumental role in youth psychotherapy (Kendall, Hudson, Gosch, Flannery-Schroeder, & Suveg, 2008; Shirk, 2001), although only one study has tested this hypothesis for youth treatment (Hogue et al., 2008). The few studies that have tested this hypothesis in the adult literature have produced mixed findings (Webb et al., 2010). A factor that might contribute to the assorted findings is that therapist competence has proven difficult to define and measure (e.g., Barber et al., 2007; Bellg et al., 2004; Milne, Claydon, Blackburn, James, & Shelkh, 2001). Efforts to define competence can be placed under the technical (“specific”) or “nonspecific” aspects of the therapy process (e.g., Wampold et al., 1997). To date, most definitions have focused upon the skill in the application of specific aspects of treatment—that is, the technical quality of interventions (skillfulness of delivery of interventions) and the timing and appropriateness of an intervention for a given client and situation (responsiveness). However, others have suggested that it is important to assess competence in the “nonspecific” or “common” elements of psychotherapy (also called “global” competence; Barber et al., 2007). Although researchers agree on some aspects of common competence (e.g., alliance-building skills), they do not agree on all aspects and there may be certain parts of common competence that are not identified or well understood to date.

Although more theoretical and empirical work is needed to clarify whether technical and common aspects of competence contribute to outcomes, current evidence would support an assessment of competence including (a) competence in delivering specific practice elements (e.g., exposure for youth anxiety treatment or cognitive interventions for youth depression treatment) and (b) competence related to common aspects of therapy (e.g., alliance formation and creating positive expectancies). Defined as such, therapist competence represents another potential quality indicator for children's mental health that offers several important applications for D&I research. First, assessing technical and common competence would help clarify the role of therapist competence in promoting positive youth outcomes. Second, disentangling technical and common competence could help refine therapist training efforts by indicating whether therapists need instruction in technical or more common relational skills. Third, assessing adherence and competence concurrently would help clarify the role each component plays in promoting outcomes.

Relational Factors

Relational processes are thought to play an important role in youth psychotherapy, and here we focus on two important components that are linked with outcomes: (a) alliance and (b) client involvement (Karver et al., 2006; McLeod, 2011; Shirk & Karver, 2011). Relational components like these are viewed by some as critical to the success of the technical elements (Dane & Schneider, 1998; Donabedian, 1988). In other words, technical elements may only be successful if clients form an alliance with the therapist and become active participants in treatment activities (Kendall & Ollendick, 2004).

Proper alliance measurement gauges the child-therapist and parent-therapist relationships because both types of alliance are linked with positive outcomes in youth psychotherapy (McLeod, 2011; Shirk & Karver, 2011). Typically, the alliance is considered to entail two important and interacting dimensions: (a) bond, the affective connection between therapist and client, and (b) task, agreement on the activities of therapy (McLeod, 2011; Shirk & Saiz, 1992). Both dimensions may be particularly important to the success of youth psychotherapy for children and parents (McLeod & Weisz, 2005; Shirk & Saiz, 1992).

Client involvement is also considered a critical ingredient of successful youth psychotherapy. Involvement is typically defined as the level of behavioral, affective, and cognitive participation in therapeutic activities (Karver et al., 2008). Youth psychotherapy contains child-, parent-, group-, and family-focused models, so the “client” for whom involvement is gauged must be defined accordingly (McLeod et al., in press). The extent to which a client engages in therapeutic activities is hypothesized to promote treatment effectiveness by promoting client skill acquisition (Chu & Kendall, 2004). Research supports the link between involvement and outcome in youth psychotherapy (Chu & Kendall, 2004; Karver et al., 2006).

We propose alliance and involvement as candidate quality indicators because both constructs are thought to facilitate clients' receipt of the active ingredients of EBTs (i.e., the technical aspects of treatment discussed earlier). Measures of alliance and involvement could be applied in D&I research in a few important ways. First, understanding the link between these relational factors and outcomes in practice settings represents an important goal for clinical research and one that would be served by the development and application of these indicators. Second, research is needed to investigate the interplay of relational and technical factors in the implementation of EBTs (and other treatments) in practice settings. Third, understanding whether the implementation of manualized EBTs in practice settings enhances, or interferes with, the relational aspects of treatment can help inform efforts to adapt these treatments for practice settings (Langer, McLeod, & Weisz, 2011).

In sum, we have identified five candidate quality indicators stemming from our reconceptualization of treatment integrity: (a) adherence, (b) differentiation, (c) competence, (d) alliance, and (e) involvement. In the next section, we translate these concepts into actionable steps to move the field of D&I research forward through the use of a benchmarking approach consistent with current quality improvement and quality of care models.

USING FEEDBACK SYSTEMS TO GUIDE QUALITY IMPROVEMENT

Description of treatment implementation can provide a road map for quality improvement efforts, although merely characterizing the elements of treatment implementation may not be sufficient. Once treatment implementation data are available, additional tools are needed to guide quality improvement decisions (Schoenwald et al., 2011). In the healthcare and business fields, such tools exist in the form of feedback systems that use benchmarking methods. In this section of the article, we describe how a feedback system that utilizes benchmarking can be used to guide D&I efforts related to bringing EBTs to community-based service settings.

Feedback systems are an important quality improvement tool (Bradley et al., 2004). In feedback systems, an individual is given information by a third party about how his or her behavior compares to an established standard (Kluger & Denisi, 1996). Data support the notion that feedback interventions improve performance at individual and at aggregate group levels (DeShon, Kozlowski, Schmidt, Milner, & Wiechmann, 2004; Locke & Latham, 1990). Seeing the potential of feedback systems, researchers have called for the use of this tool in D&I research (Bickman, 2008; Garland et al., 2010). To date, most feedback systems used in mental healthcare research have focused upon outcomes (e.g., Bickman, Kelley, Breda, de Andrade, & Riemer, 2011; Lambert et al., 2003; Stein, Kogan, Hutchison, Magee, & Sorbero, 2010), with results demonstrating that providing feedback to therapists and clients about client progress improves attendance and outcomes (Bickman et al., 2011; Lambert, Hansen, & Finch, 2001; Lambert et al., 2003).

Recently, mental health researchers have called for feedback systems to incorporate information about the processes of care, including data about treatment implementation (Garland et al., 2010; Kelley & Bickman, 2009), although only a few have answered that call to date (e.g., Anker, Duncan, & Sparks, 2009). We contend that feedback systems containing information about the different elements of treatment implementation may facilitate the transfer of EBTs to community-based service settings. Indeed, creating feedback systems focused upon treatment implementation has the potential to create “learning organizations” that use real-time data (online) to make quality improvement decisions (Knox & Aspy, 2011).

An important component of feedback systems is the information used for comparison. So an important next consideration concerns what data are the best to use for quality improvement. With this issue in mind, we now turn to benchmarking.

BENCHMARKING AS A KEY TOOL IN FEEDBACK APPROACHES

Benchmarking is a total quality improvement tool (Lai, Huang, & Wang, 2011) designed to facilitate the enhancement of business operations and organizational performance by helping organizations evaluate their own operations and determine whether they can be made better (Keehley & MacBride, 1997). In essence, in a feedback system, benchmarking establishes a comparison point used to evaluate the progress of the organization toward a specific goal (Lai et al., 2011). Specifically, a company compares a quality indicator in a relevant domain (e.g., customer service as rated by online surveys) to a benchmark (e.g., the performance of an exemplary competitor). By doing so, the company can identify gaps in performance that are then used as targets for quality improvement efforts.

To date, the few benchmarking studies in mental health care have focused primarily upon outcomes observed in non-RCT studies in community settings and have not been considered quality improvement efforts (e.g., Franklin, Abramowitz, Kozak, Levitt, & Foa, 2000; Persons, Bostrom, & Bertagnolli, 1999; Wade, Treat, & Stuart, 1998; Warren & Thomas, 2001; Weersing & Weisz, 2002). In this article, we propose to apply benchmarking strategies in a distinct way. Specifically, we contend that feedback systems with the five treatment integrity benchmarks can be applied to answer critical D&I research questions. For example, the approach would help to inform whether “failure” to produce a desired outcome is due to the intervention (i.e., when all quality indicators are met, then the treatment is not effective and another option is needed) or its implementation (i.e., treatment not provided correctly, training/consultation needed; Schoenwald et al., 2011).

Choosing a Benchmark Comparator

An important step in establishing benchmarks is the identification of the appropriate comparator (Kennedy, Allen, & Allen, 2002). In business, a number of options have been described for selecting a comparator (see Kennedy et al., 2002), with the goals of a project largely determining the selection process. Here, we focus upon comparators that will help researchers interpret findings generated by transportability and dissemination research. For this type of research, three comparators are relevant: (a) efficacy trial standard, (b) high-performing external unit (i.e., similar unit in another organization), and (c) high-performing internal unit (i.e., unit within the same organization). These comparators have relative strengths and weaknesses, as discussed briefly here.

Using data from efficacy trials to generate benchmarks has a number of applications in transportability and dissemination research. First, these data may help ascertain how closely an EBT was implemented to the manner in which it was delivered in the near-optimal laboratory studies (i.e., high dosage, high competence, high purity). Such a comparator is useful for guiding interpretation of outcomes from effectiveness and transportability research (Schoenwald et al., 2011). Further, the approach may also enhance the informational value of D&I research by allowing researchers to determine whether the implementation of an EBT in practice settings approximates the standards found in laboratory settings. Second, benchmarks from efficacy trials could be used to inform quality control efforts, such as therapist training and supervision, providing potential goals for therapist training efforts (e.g., Sholomskas et al., 2005).

In other situations, using a community clinic benchmark (i.e., not generated from an efficacy study) is a reasonable choice and one consistent with recent calls for researchers to generate practice-based evidence (cf. Garland et al., 2010; McLeod & Weisz, 2010). As noted, there are two different comparators to consider here. First, one could identify a strong-performing organization that provides similar services to the one engaged in the benchmarking project: an external benchmark. For example, a new agency might choose to use an established agency with a good reputation as its comparator. Using an external agency as a benchmark can help an organization understand how well it is performing in a particular domain in relation to a competitor. For example, Stern, Niemann, Wiedemann, and Wenzlaff (2011) used external benchmarking methods in hospital settings to improve quality of care for patients with cystic fibrosis (CF). The study included 12 CF clinics and used quality indicators relevant to the population (e.g., body mass index). Minimally acceptable benchmarks (e.g., patients were defined as malnourished if weight for height was < 90% of the predicted sex and height in children) were identified and used to evaluate each site. The “highest performing” sites for each quality indicator were identified and asked to define their specific strategies (e.g., more individualized intensified dietary counseling) for use by other centers for quality improvement.

Alternatively, in some larger organizations, internal benchmarks may be useful; that is, a high-performing unit within the same agency may serve as the comparator. For example, a large mental health agency with multiple sites may be able to identify a high-functioning site or team to use as a benchmark based upon quality indicators (e.g., Pincus et al., 2011; Zima et al., 2005). In either of these cases (internal and external benchmarking), two factors are important in determining the most appropriate benchmarks: (a) outcomes and (b) practice patterns. Practice settings that produce optimal outcomes on quality indicators and use specific treatments for specific child problems represent ideal candidates to serve as benchmarks (Profit et al., 2010).

All things considered, using data from community (vs. research) settings offers some advantages. Acknowledging that EBTs developed in laboratory settings may not always be a good fit for the youth treated in practice settings, some researchers have asserted that more treatment development should occur in practice settings and that treatment adaptation will be needed (e. g., Gotham, 2004; Hogue, 2010; Southam-Gerow, Hourigan, & Allin, 2009; Weisz, Jensen, & McLeod, 2005). Benchmarking EBTs that have been successfully implemented in practice settings could aid efforts to adapt EBTs for use in practice settings. The approach could also help to identify practice-based evidence (i.e., what therapeutic procedures work with particular children in practice settings; Garland et al., 2010). In some cases, this may indicate that there is a convergence of science and practice in which elements found in the treatment literature are also working well in community practice settings. In other cases, there may be a divergence in which elements not found in the treatment literature produce beneficial effects in practice settings.

Benchmark Measurement

Once the appropriate comparator is chosen, one must determine how to operationalize the benchmark. In the case of treatment integrity, this means identifying efficient and effective measures for the treatment integrity components (Garland et al., 2010; McGlynn et al., 1988; Mendel, Meredith, Schoenbaum, Sherbourne, & Wells, 2008; Schoenwald et al., 2011). Unfortunately, the science and measurement of treatment integrity research are underdeveloped in the child mental health field, although recent research has begun to address this gap (see Hogue et al., 2008). This is not a one-size-fits-all problem. Different tools are needed (e.g., self-report, observer report) to meet the needs of the various stakeholders who are interested in measuring treatment implementation (Garland, Hurlburt, Brookman-Frazee, Taylor, & Accurso, 2009; McLeod et al., 2009). Here, we focus upon the needs of researchers interested in measuring the various aspects of treatment integrity to establish benchmarks.

Observational assessment represents the gold standard in treatment integrity research because it provides objective and highly specific information regarding clinician within-session performance (Hill, 1991; Hogue, Liddle, & Rowe, 1996). Observational coding has a number of advantages that make it appropriate for benchmarking. Most notably, observational assessment bypasses some of the limitations of therapist self-report. Although self-report data are important, therapists may have an incomplete or inaccurate perception of what happens in their sessions (Chevron & Rounsaville, 1983; Hurlburt, Garland, Nguyen, & Brookman-Frazee, 2010). Thus, relying solely on their reports may not provide a comprehensive description of treatment implementation. Direct observation by trained observers, when coding is assessed for reliability, provides the most accurate description of in-session behavior. Thus, for researchers interested in benchmarking treatment implementation, it is important to use direct observation methods. Of course, the time and financial cost associated with direct observation can make it difficult for some stakeholders to use this method.

It is also important to incorporate design elements that help produce data about treatment implementation with the maximum degree of reliability, validity, and utility. Efforts to characterize treatment implementation should use quantitative measures, so variation across therapists and clients can be captured. For example, therapists vary in the extent to which they employ different interventions, so it is important that scoring strategies capture both the breadth and depth of therapeutic interventions (McLeod & Weisz, 2010). Quantitative measures are also ideally suited to assess structure-process and/or process-outcome relations (Hogue et al., 1996) and therefore are a good match for D&I research. It is also important that both therapist (adherence, differentiation, competence) and client contributions (alliance, involvement) are considered (Donabedian, 1988; McLeod et al., 2009). Altogether, these design elements will produce benchmark data about key quality indicators that can be used in D&I research.

In sum, feedback systems that utilize benchmarking data have the potential to advance D&I research. By comparing treatment implementation to a benchmark, researchers can enhance the informational value of D&I research and pinpoint areas for quality improvement. This will help researchers create feedback systems that use real-time data to make quality improvement decisions. Such a system can be used to study the implementation process, adapt EBTs for use in different contexts, and speed up the transmission of evidence-based practices to community settings (Knox & Aspy, 2011). We now describe a program of research designed (in part) to demonstrate how such a system could be used to advance D&I research.

HOW FEEDBACK SYSTEMS USING INTEGRITY BENCHMARKS CAN ADVANCE D&I RESEARCH

We have thus far discussed how concepts and methodologies from three different research traditions can help researchers characterize treatment implementation and use the resulting data to guide quality improvement efforts in practice settings. This hybrid approach has the potential to advance D&I research within a quality of care framework. To illustrate that potential, we now describe the application of treatment integrity benchmarking related to transporting an EBT for child anxiety, namely CBT.

Child anxiety has an extensive treatment literature, and CBT is the best-supported treatment, with over 25 published RCT studies documenting positive effects (Chorpita et al., 2011). However, recent effectiveness studies have documented that CBT, though effective, was not more effective than usual clinical care (Barrington, Prior, Richardson, & Allen, 2005; Southam-Gerow et al., 2010). A number of factors may explain these findings. Compared to efficacy trials, research has demonstrated that in effectiveness trials, (a) child participants have higher levels of comorbidity, (b) therapists have full caseloads and little previous experience with EBTs, (c) families were from ethnic minority groups, and (d) families reported lower incomes (Ehrenreich-May et al., 2011; Southam-Gerow, Chorpita et al., 2008; Southam-Gerow, Marder, & Austin, 2008). It is plausible that one, or more, of these factors may influence the implementation or potency of an EBT or that the therapist training and supervision model were not adequate. Therefore, it is important to determine whether failure to produce the desired clinical outcome was due to the EBT model (i.e., the treatment itself was not effective) or its implementation (i. e., treatment integrity was compromised; e.g., Schoenwald et al., 2011).

Assessment of treatment integrity is needed to answer these critical questions. Each trial assessed treatment adherence and found that therapists adhered to CBT (Barrington et al., 2005; Southam-Gerow et al., 2010). However, Barrington et al. relied upon therapist self-report, and Southam-Gerow and colleagues relied upon observer-rated presence/absence ratings to document treatment adherence. Although these methods are consistent with the procedures typically used in efficacy trials to document treatment integrity (see Perepletchikova, Treat, & Kazdin, 2007), they may not be adequate for D&I research (McLeod et al., 2009).

Realizing the need for a more in-depth investigation, Southam-Gerow et al. (2010) took steps to further document treatment integrity. In this trial, 48 youths (aged 8–15) diagnosed with DSM-IV anxiety disorders were randomized to CBT or usual care (UC) provided by clinicians employed at community clinics who were randomized to one of the two treatment groups (i.e., CBT, usual care). Outcome results supported the potency of both treatment groups, with remission rates for primary anxiety diagnoses exceeding 65%; however, the groups did not significantly differ on symptom or diagnostic outcomes.

The fact that CBT did not outperform usual care was inconsistent with study hypotheses and some other effectiveness studies (Baer & Garland, 2005; Ginsburg & Drake, 2002; Weisz et al., 2012). Why this failure occurred leads to a number of important scientific questions that the measurement of treatment implementation is poised to answer. For example, at what level was the adherence of the CBT? What elements in usual care contributed to its potency? To address these questions, Southam-Gerow et al. (2010) used the Therapy Process Observational Coding System for Child Psychotherapy Strategies Scale (TPOCS-S; McLeod & Weisz, 2010) to characterize the treatment provided in the two treatment conditions. Originally designed to provide a means of objectively describing usual clinical care for youth (McLeod & Weisz, 2010), the TPOCS-S assesses a diverse range of therapeutic interventions (cognitive, behavioral, psychodynamic, client-centered, family) as applied to a variety of treated problems and conditions. Due to its breadth, the TPOCS-S represents an ideal measure to assess treatment differentiation because of its inclusion of therapeutic interventions found in multiple treatment approaches.

In the Southam-Gerow et al. (2010) study, the TPOCS-S was used to answer three questions: (a) to what extent did the CBT condition contain the required ingredients? (i.e., adherence); (b) to what extent did usual care include elements found in the CBT condition? (i.e., differentiation); and (c) to what extent did the CBT condition contain proscribed interventions? (i.e., psychodynamic or family interventions). Rating 70 sessions for 32 cases (13 CBT, 19 UC), the authors found that the CBT group implemented the expected CBT interventions, but not at a particularly high level (M = 2.24, SD = 0.52 on a 7-point scale), based on anchors of the extensiveness rating scale. Further, although usual care therapists employed fewer CBT interventions, the extensiveness of those interventions was rather low (M = 1.62, SD = 0.35 on a 7-point scale). Thus, youth in the CBT group appear to have received a relatively low dose of CBT (Southam-Gerow et al., 2010), although the CBT dose was higher than that received by usual care.

However, this interpretation is speculative because we do not have benchmarking data to which to compare the dosage provided in the CBT group. Benchmarking data from an efficacy trial would help determine whether the therapists in the effectiveness trial implemented CBT at the dose and purity (i.e., ratio of prescribed to proscribed interventions) achieved by therapists in laboratory conditions. Without such data, it is impossible to determine whether CBT was implemented at the dose seen in efficacy trials. Thus, although the study indicates that the dosage of CBT was in the lower part of the possible range, it is unclear whether that dose is less than what is needed to produce optimal effects. Further, the TPOCS-S does not assess the quality of interventions or the relational aspects of therapy, all of which may have influenced these findings.

A next step needed for our example would be evidence to guide the establishment of “minimal” scores to serve as benchmarks for each facet of treatment implementation. These data would help to improve interpretation of research findings, as our discussion of the Southam-Gerow et al. (2010) trial exemplifies. Further, these data could be used to inform training efforts in a variety of settings by guiding evaluation of training (Beidas & Kendall, 2010; Herschell, Kolko, Baumann, & Davis, 2010; Sholomskas et al., 2005) or supervision efforts. For example, therapists could be trained to a certain level of adherence and/or competence prior to participating in a treatment study (e.g., efficacy, effectiveness, transportability). As another example, treatment implementation could be monitored throughout the study by supervisors to monitor integrity. Measuring key quality indicators and incorporating the data into a feedback system accessible by supervisors would help minimize departures from the model and guide quality improvement efforts. For the field to take advantage of this potential, however, there is a need for treatment integrity research to (a) establish measures for key constructs and (b) use those measures to determine initial benchmarks. We conclude the article by describing a program of research we have been engaged in that aims to accomplish just such a goal.

The Treatment Integrity Measurement Study (TIMS; NIMH RO1 MH086529) is a five-year NIMH-funded R01 project that will result in the development of measures for the five quality indicators described in this article: (a) adherence, (b) differentiation, (c) competence, (d) alliance, and (e) client involvement. TIMS involves developing and applying these measurement tools across data from three different randomized controlled trials: one efficacy trial (Kendall et al., 2008) and two effectiveness studies (Southam-Gerow et al., 2010; Weisz et al., 2012) that evaluate CBT for youth with anxiety disorders. The first goal of this work is to establish the psychometrics of four measures: (a) a CBT for youth anxiety adherence measure, (b) a treatment differentiation measure (TPOCS-S), (c) a CBT for youth anxiety competence measure, and (d) a common factors competence measure. Once the psychometrics are established, we will determine the application of each measure to key questions in the field, including using the efficacy trial to establish benchmarks across the five quality indicators measured in the study.

CONCLUSION

In this article, we have made the case for considering the components of treatment integrity as candidates for quality indicators of treatment implementation in a broad quality of care framework. To do so, we broadened the definition of treatment integrity, including technical and relational aspects of the therapy process. Further, we discussed a variety of concepts from diverse research literature (e.g., business, healthcare, education), including the use of feedback systems and benchmarking. In the end, we applied these concepts to the case of transporting and disseminating CBT for child anxiety disorders. We recounted what is known to date about how treatment integrity influences CBT when transported to community clinical settings and described a new research project, the TIMS project, that aims to develop a set of treatment integrity measures that can be used as key tools for D&I research (e. g., by guiding quality improvement efforts).

Although we take the potentially self-aggrandizing step of highlighting our own work as an exemplar, others are conducting similarly important work, including efforts to benchmark adherence and competence for EBTs for adolescent substance abuse (e.g., Hogue, 2009) and develop child, parent, and therapist report measures of CBT implementation (e.g., Hawley, 2011). Many of these efforts are designed to develop appropriate measures that can characterize one or more aspects of treatment implementation. As these research efforts begin to bear fruit, researchers will have a variety of measures that can be used to generate benchmarks that can be incorporated into feedback systems. Moreover, establishing benchmarks from efficacy trials (e.g., TIMS) and practice settings (e.g., Hogue, 2009) will provide data that can guide future D&I research.

Footnotes

We use the phrase treatment implementation to represent one component of the broader construct of implementation (as in dissemination and implementation research). In its broader sense, implementation refers to the various efforts (and interventions) needed to transport or disseminate a treatment (successfully) into a new setting (cf. Chambers et al., 2005). These efforts included but are not limited to the specific activities of a therapist with a client. Treatment implementation in this article, thus, refers to these therapist–client activities.

What is deemed an ideal quality indicator may vary by stakeholder group.

REFERENCES

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality . 2006 National healthcare disparities report (AHRQ Publication No. 07-0012) U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville, MD: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Anker MG, Duncan BL, Sparks JA. Using client feedback to improve couple therapy outcomes: A randomized clinical trial in a naturalistic setting. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(4):693–704. doi: 10.1037/a0016062. doi:10.1037/a0016062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer S, Garland EJ. Pilot study of community-based cognitive behavioral group therapy for adolescents with social phobia. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44(3):258–264. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200503000-00010. doi:10.1097/00004583-200503000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber JP, Sharpless BA, Klostermann S, McCarthy KS. Assessing intervention competence and its relation to therapy outcome: A selected review derived from the outcome literature. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2007;38(5):493–500. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.38.5.493. [Google Scholar]

- Barrington J, Prior M, Richardson M, Allen K. Effectiveness of CBT versus standard treatment for childhood anxiety disorders in a community clinic setting. Behaviour Change. 2005;22(1):29–43. doi:10.1375/bech.22.1.29.66786. [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Kendall PC. Training therapists in evidence-based practice: A critical review of studies from a systems-contextual perspective. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2010;17(1):1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellg AJ, Borellei B, Resnick B, Hecht J, Miniccuci DS, Ory M, Czajkowski S. Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: Best practices and recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Health Psychology. 2004;23(5):443–451. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickman L. A measurement feedback system (MFS) is necessary to improve mental health outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47(10):1114–1119. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181825af8. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181825af8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickman L, Kelley SD, Breda C, de Andrade AR, Riemer M. Effects of routine feedback to clinicians on mental health outcomes of youth: Results of a randomized trial. Psychiatric Services. 2011;62(12):1423–1429. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.002052011. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.002052011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley EH, Holmboe ES, Mattera JA, Roumanis SA, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. Data feedback efforts in quality improvement: Lessons learned from US hospitals. Quality & Safety in Health Care. 2004;13:26–32. doi: 10.1136/qhc.13.1.26. doi:10.1136/qshc.2002.4408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnam MA, Hepner KA, Miranda J. Future research on psychotherapy practice in usual care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10488-009-0254-7. doi:10.1007/s10488-009-0254-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Nich C, Sifty RL, Nuro KF, Frankfurter TL, Ball SA, Rounsaville BJ. A general system for evaluating therapist adherence and competence in psychotherapy research. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;57(3):225–238. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00049-6. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(99)00049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Nuro KF. One size cannot fit all: A stage model for psychotherapy manual development. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2002;9(4):396–406. doi:10.1093/clipsy/9.4.396. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Substance Abuse Prevention . Finding the balance: Program fidelity and adaptation in substance abuse. SAMHSA, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville, MD: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers DA, Ringeisen H, Hickman EE. Federal, state, and foundation initiatives around evidence-based practices for child and adolescent mental health. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2005;14(2):307–327. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2004.04.006. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevron ES, Rounsaville BJ. Evaluating the clinical skills of psychotherapists: A comparison of techniques. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1983;40:1129–1132. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790090091014. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790090091014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL. Mapping evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: Application of the distillation and matching model to 615 treatments from 322 randomized trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(3):566–579. doi: 10.1037/a0014565. doi:10.1037/a0014565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL, Ebesutani C, Young J, Becker KD, Nakamura BJ, Starace N. Evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: An updated review of indicators of efficacy and effectiveness. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2011;18(2):154–172. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2850.2011.01247.x. [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL, Weisz JR. Identifying and selecting the common elements of evidence based interventions: A distillation and matching model. Mental Health Services Research. 2005;7(1):5–20. doi: 10.1007/s11020-005-1962-6. doi:10.1007/s11020-005-1962-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu BC, Kendall PC. Positive association of child involvement and treatment outcome within a manual-based cognitive-behavioral treatment for children with anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(5):821–829. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.821. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke G, Debar L, Lynch F, Powell J, Gale J, O'Connor E, Hertert S. A randomized effectiveness trial of brief cognitive-behavioral therapy for depressed adolescents receiving antidepressant medication. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44(9):888–898. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000171904.23947.54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dane AV, Schneider BH. Program integrity in primary and early secondary prevention: Are implementation effects out of control? Clinical Psychology Review. 1998;18:23–45. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(97)00043-3. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(97)00043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeShon RP, Kozlowski SWJ, Schmidt AM, Milner KR, Wiechmann D. A multiple-goal, multilevel model of feedback effects on the regulation of individual and team performance. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2004;89(6):1035–1056. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.89.6.1035. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.89.6.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donabedian A. The quality of care: How can it be assessed? Journal of the American Medical Association. 1988;260(12):1743–1748. doi: 10.1001/jama.260.12.1743. doi:10.1001/jama.1988.03410120089033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss BD. Changing the way we study change in psychotherapy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2004;11(4):368–386. doi:10.1093/clipsy/bph094. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenreich-May J, Southam-Gerow MA, Hourigan SE, Wright LR, Pincus DB, Weisz JR. Characteristics of anxious and depressed youth seen in two different clinical contexts. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011;38:398–411. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0328-6. doi:10.1007/s10488-010-0328-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embry DD, Biglan A. Evidence-based kernels: Fundamental units of behavioral influence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2008;11(3):75–113. doi: 10.1007/s10567-008-0036-x. doi:10.1007/s10567-008-0036-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, Friedman RM, Wallace F. Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature. University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, The National Implementation Research Network; Tampa, FL: 2005. (FMHI Publication #231) [Google Scholar]

- Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Wagner EF, McEachran AB. Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy as a maintenance treatment of recurrent depression: Contributing factors. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;48:1053–1059. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360017002. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360017002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin ME, Abramowitz JS, Kozak MJ, Levitt JT, Foa EB. Effectiveness of exposure and ritual prevention for obsessive-compulsive disorder: Randomized compared with nonrandomized samples. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:594–602. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.68.4.594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulda KG, Lykens KK, Bae S, Singh KP. Unmet mental health care needs for children with special health care needs stratified by socioeconomic status. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2009;14(4):190–199. doi:10.1111/j.1475-3588.2008.00521.x. [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Bickman L, Chorpita BF. Change what? Identifying quality improvement targets by investigating usual mental health care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2010;37(1-2):15–26. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0279-y. doi:10.1007/s10488-010-0279-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Hawley KM, Brookman-Frazee L, Hurlburt M. Identifying common elements of evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children's disruptive behavior problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47(5):506–515. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31816765c2. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b13e31816765c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Hurlburt M, Brookman-Frazee L, Taylor RM, Accurso EC. Methodological challenges of characterizing usual care psychotherapeutic practice. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10488-009-0237-8. doi:10.1007/s10488-009-0237-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg GS, Drake KL. Anxiety sensitivity and panic attack symptomatology among low-income African-American adolescents. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2002;16:83–96. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(01)00092-5. doi:10.1016/S0887-6185(01)00092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotham HJ. Diffusion of mental health and substance abuse treatments: Development, dissemination, and implementation. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2004;11:161–176. doi:10.1093/clipsy/bph067. [Google Scholar]

- Hawley KM. Increasing the capacity of providers to monitor fidelity to child and family CBT. University of Missouri; 2011. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Herschell AD, Kolko DJ, Baumann BL, Davis AC. The role of therapist training in the implementation of psychosocial treatments: A review and critique with recommendations. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(4):448–466. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.005. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill CE. Almost everything you ever wanted to know about how to do process research on counseling and psychotherapy but didn't know who to ask. In: Watkins CE, Schneider LJ, editors. Research in counseling. Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1991. pp. 85–118. [Google Scholar]

- Hill CE, O'Grady KE, Elkin I. Applying the Collaborative Study Psychotherapy Rating Scale to therapist adherence in cognitive-behavior therapy, interpersonal therapy, and clinical management. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60(1):73–79. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.1.73. doi:0022-006X/92/J3.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A. Adherence process research on developmental interventions: Filling in the middle. In: Higgins-D'Alessandro A, Jankowski KRB, editors. New directions for child and adolescent development. Vol. 98. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2002. pp. 67–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A. Evidence-based practices and services outcomes in usual care of ASA. Columbia University; 2009. Unpublished manuscript, prepared at the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse. [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A. When technology fails: Getting back to nature. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2010;17(1):77–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01196.x. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01196.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, Henderson CE, Dauber S, Barajas PC, Fried A, Liddle HA. Treatment adherence, competence, and outcome in individual and family therapy for adolescent behavior problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(4):544–555. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.544. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.60.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, Liddle HA, Rowe C. Treatment adherence process research in family therapy: A rationale and some practical guidelines. Psychotherapy. 1996;33:332–345. doi:10.1037/0033-3204.33.2.332. [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, Liddle HA, Rowe C, Turner RM, Dakof GA, LaPann K. Treatment adherence and differentiation in individual vs. family therapy for adolescent substance abuse. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1998;45(1):104–114. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.45.1.104. [Google Scholar]

- Hurlburt MS, Garland AF, Nguyen K, Brookman-Frazee L. Child and family therapy process: Concordance of therapist and observational perspectives. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2010;37(3):230–244. doi: 10.1007/s10488-009-0251-x. doi:10.1007/s10488-009-0251-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussey PS, Mattke S, Morse L, Ridgely MS. Evaluation of the use of AHRQ and other quality indicators. RAND Health; Rockville, MD: 2007. Prepared for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones HA, Clarke AT, Power TJ. Expanding the concept of intervention integrity: A multidimensional model of participant engagement. In Balance, Newsletter of Division 53 (Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology) of the American Psychological Association. 2008;23(1):4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Karver MS, Handelsman JB, Fields S, Bickman L. Meta-analysis of therapeutic relationship variables in youth and family therapy: The evidence for different relationship variables in the child and adolescent treatment outcome literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26(1):50–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.09.001. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karver MS, Shirk S, Handelsman J, Fields S, Gudmundsen G, McMakin D, Crisp H. Relationship processes in youth psychotherapy: Measuring alliance, alliance building behaviors, and client involvement. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2008;16(1):15–28. doi:10.1177/1063426607312536. [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB. Unmet need for mental health care among U.S. children: Variation by ethnicity and insurance status. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1548–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1548. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin A. Methodology, design, and evaluation in psychotherapy research. In: Bergin AE, Garfield SL, editors. Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change. 4th ed. John Wiley & Sons; Oxford, UK: 1994. pp. 19–71. [Google Scholar]

- Keehley P, MacBride SA. Can benchmarking for best practices work for government? Quality Progress. 1997;30(3):75–80. Retrieved from http://proxy.library.vcu.edu/login?url=http://proquest.umi.com/pqdweb?did=11267335&Fmt=7&clientId=4305&RQT=309&VName=PQD. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley SD, Bickman L. Beyond outcomes monitoring: Measurement feedback systems in child and adolescent clinical practice. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2009;22(4):363–368. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32832c9162. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e32832c9162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Hudson JL, Gosch E, Flannery-Schroeder E, Suveg C. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disordered youth: A randomized clinical trial evaluating child and family modalities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:282–297. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.282. doi:10.1080/10508420802064309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Ollendick TH. Setting the research and practice agenda for anxiety in children and adolescence: A topic comes of age. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2004;11(1):65–74. doi:10.1016/S1077-7229(04)80008-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy MP, Allen J, Allen G. Benchmarking in emergency health systems. Emergency Medicine. 2002;14(4):430–435. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2026.2002.00351.x. doi:10.1046/j.1442-2026.2002.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluger AN, Denisi A. The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;II9(2):254–284. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.119.2.254. [Google Scholar]

- Knox LM, Aspy CB. Quality improvement as a tool for translating evidence-based interventions into practice: What the youth violence prevention community can learn from healthcare. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;48(1-2):56–64. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9406-x. doi:10.1007/s10464-010-9406-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai MC, Huang HC, Wang WK. Designing a knowledge-based system for benchmarking: A DEA approach. Knowledge-Based Systems. 2011;24(5):662–671. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2011.02.006. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MJ, Hansen NB, Finch AE. Patient-focused research: Using patient outcome data to enhance treatment effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69(2):159–172. doi:10.1037//0022-006X.69.2.159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MJ, Whipple JL, Hawkins EJ, Vermeersch DA, Nielsen SL, Smart DW. Is it time for clinicians to routinely track patient outcome? A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2003;10:288–301. doi:10.1093/clipsy/bpg025. [Google Scholar]

- Langer DA, McLeod BD, Weisz JR. Do treatment manuals undermine youth-therapist alliance in community clinical practice? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79(4):427–432. doi: 10.1037/a0023821. doi:10.1037/a0023821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke EA, Latham GP. A theory of goal setting and task performance. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- McGlynn EA, Norquist GS, Wells KB, Sullivan G, Liberman RP. Quality-of-care research in mental health: Responding to the challenge. Inquiry: A Journal of Medical Care Organization, Provision and Financing. 1988;25(1):157–170. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/29771940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD. Relation of the alliance with outcomes in youth psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31(4):603–616. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.02.001. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD, Islam NY, Wheat E. Designing, conducting, and evaluating therapy process research. In: Comer J, Kendall P, editors. The Oxford handbook of research strategies for clinical psychology. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: in press. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD, Southam-Gerow MA, Weisz JR. Conceptual and methodological issues in treatment integrity measurement. School Psychology Review. 2009;38(4):541–546. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD, Weisz JR. Using dissertations to examine potential bias in child and adolescent clinical trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(2):235–251. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.235. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]