Abstract

Background

Qualitative and quantitative data and participatory research approaches might be most valid and effective for assessing substance use/abuse and related trends in American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) communities.

Method

29 federally recognized AIAN Tribes in Washington (WA) State were invited to participate in Health Directors interviews and State treatment admissions data analyses. Ten Tribal Health Directors (or designees) from across WA participated in 30–60 minute qualitative interviews. State treatment admissions data from 2002–2008 were analyzed for those who identified with one of 11 participating AIAN communities to explore admission rates by primary drug compared to non-AIANs. Those who entered treatment and belonged to one of the 11 participating tribes (n=4,851) represented 16% of admissions for those who reported a tribal affiliation.

Results

Interviewees reported that prescription drugs, alcohol and marijuana are primary community concerns, each presenting similar and distinct challenges. Additionally, community health is tied to access to resources, services, and culturally appropriate and effective interventions. Treatment data results were consistent with interviewee reported substance use/abuse trends, with alcohol as the primary drug for 56% of AIAN adults compared to 46% of non-AIAN, and other opiates as second most common for AIAN adults in 2008 with 15% of admissions.

Limitations

Findings are limited to those tribal communities/community members who agreed to participate.

Conclusion

Analyses suggest that some diverse AIAN communities in WA State share similar substance use/abuse, treatment, and recovery trends and continuing needs.

Scientific Significance

Appropriate and effective research with AIAN communities requires respectful and flexible approaches.

Keywords: substance use, treatment, recovery, American Indian, Washington

BACKGROUND

Substance use and associated harms are primary concerns in many American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) communities and exist within a complex and changing context of significant health disparities, economic/social consequences, risk and protective factors, and community resources, strengths, and resiliencies (1–3). To begin to address these concerns and related needs requires a greater understanding of the entire context and its many components, including current substance use and related trends. Furthermore, utilizing qualitative community-based data gathered through respectful, participatory research approaches together with available quantitative data may provide a more complete and valid assessment of substance use and related trends (4).

In the mid 2000s, data from publicly funded treatment admissions of AIAN individuals both nationally and in Washington (WA) State indicated that admissions for methamphetamine had increased over the past several years. These reports and community-institutional efforts prompted the National Institute on Drug Abuse’s (NIDA) National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network (CTN) to fund an exploratory/developmental, national, multisite study originally intended to investigate current methamphetamine abuse in AIAN communities. However, during the development of this multisite study, it became clear that alcohol continued to be the substance for which treatment was most often sought and that while methamphetamine was still a major concern, there was a more recent and growing concern about the influx into and impact of prescription opiates in tribal communities (5–10). This awareness led to an expansion of the project beyond its original focus on methamphetamine to focus on substance use/abuse more broadly, factors contributing to use, abuse, or non-use, and community resources and efforts around prevention and treatment.

Studies were developed in five CTN regions in collaboration with local AIAN communities and organizations and following Community Based and Tribally Based Participatory Research (CBPR/TPR; 11, 12) approaches and ethical principles specifically developed by collaborators to guide the process (13). CBPR/TPR are becoming more widely recognized for their potential to benefit community understanding of issues under study and enhance researchers’ ability to understand community priorities and the need for culturally sensitive communication and research approaches (14). CBPR/TPR emphasize the need for and value of an alliance between investigators and communities in the design and completion of studies that address health promotion and health disparities (15–18). Effective collaboration leads to studies that address research questions of high importance to the community, promotes community participation, enhances the interpretation of results and facilitates the dissemination and adoption of study findings (16, 19). Partnerships, shared responsibility, and ownership between those with scientific knowledge and those with personal and cultural knowledge are emphasized (12, 20).

Effective CBPR/TPR also guide the development of studies and methods that are most acceptable, appropriate, and effective for addressing research questions in AIAN communities (21). Thus, WA State’s CTN study shared characteristics with other CTN regions’ studies but also incorporated unique local opportunities (13). First, tribal community Health Directors (HD) or their designees contributed their perspectives on substance use/abuse and related concerns, harms, and trends. Second, analyses were conducted with available drug treatment admissions data to evaluate the demand for and access to treatment for AIANs. Qualitative and quantitative data together provide a more complete picture of current substance use and treatment trends and incorporate more culturally appropriate data-gathering methods than purely quantitative approaches (15). Following a CBPR/TPR process to the extent possible, two WA State AIAN health and policy advisory groups provided limited advisement and guidance regarding the research process before, during, and after the studies were completed.

OBJECTIVES

The specific objectives of the larger WA State CTN study (i.e., “Methamphetamine and Other Drugs in AIAN Communities – MOD”) were to learn about current substance use/abuse, related concerns and harms, existing prevention and treatment, reasons/causes of use, and current community strengths, resources, and needs related to prevention and treatment, with the long-term goals of improving substance use/abuse interventions and eliminating health disparities for AIAN people and communities. An additional objective was to continue to develop trust and research partnerships with AIAN communities and organizations. The HD Interviews and state treatment admissions data analyses were components of the CTN MOD study and provided the data for this article, which describes trends in substance use/abuse, treatment admissions, recovery, and related concerns and needs in some WA State tribal communities. Additional findings from the CTN MOD study may be reported in future articles.

METHOD

We invited 29 federally recognized AIAN Tribes in WA State to participate in 1) Health Directors (HD) Interviews, and 2) analyses of state treatment admissions data from the Division of Behavioral Health and Recovery’s (DBHR) Treatment and Report Generation Tool (TARGET). Two key persons in each tribal community, such as a Tribal Council Chair and a Tribal Health Director, received separate letters describing each study and inviting participation. Follow-up conversations took place by phone and email, and 15 Tribes from across WA State chose to participate in either study, with 10 participating in HD Interviews and 11 in the TARGET Analysis (i.e., overlap with 6 in both). Participating tribal communities were proportionately distributed across the state in all four directions and in coastal, Puget Sound, and inland areas based on the number of Tribes located in those areas. Communities were rural and urban, primarily reservation based, and included a couple hundred to a few thousand tribal members and varying numbers of non-tribal community members.

Researchers presented HD Interviews and TARGET Analysis study plans, progress, and outcomes to two WA State advisory groups, the American Indian Health Commission (AIHC) and the Indian Policy Advisory Committee (IPAC). Advisory groups provided limited but specific comments, questions, and suggestions regarding the necessary participating community approvals for study participation, dissemination of study findings, and protection of Tribes’ and communities’ identities. For example, both AIHC and IPAC stated that approval from each tribe would be necessary in order to proceed with the TARGET study. With the TARGET Analysis formal approval was required via the return of the signed Tribal Leader’s Consent Form included in the recruitment materials. Institutional Review Board oversight/review was not needed for the TARGET study as these analyses met exempt status as secondary analyses of de-identified data. An exemption certificate was obtained from the University of Washington’s IRB for the HD study. With each study’s completion, separate HD and TARGET reports were provided to the advisory groups, interviewees, and participating TARGET communities.

Health Directors Interviews Methods

Some Tribal HDs chose to be interviewed and some designated others who they believed were more knowledgeable and experienced to best answer the interview questions, such as chemical dependency treatment providers, clinical supervisors, or psychiatrists. Anonymous, semi-structured interviews were conducted by phone or in person to gather participants’ perspectives about the communities’ current substance use and abuse concerns, available and effective prevention and treatment, community strengths and resources, existing needs that must be addressed to alleviate the negative consequences of substance abuse, and ideas about how to address these needs (Table 1). Interviews lasted 30–60 minutes and were conducted between June and October of 2009. Interviewees were Native, non-Native, tribal members and non-Tribal members.

Table 1.

Health Director Interview Questions

| We asked the same 6 primary questions of all ten interviewees, with follow-up questions asked as needed: |

|---|

First, we would like to hear about your community:

|

Next, we’d like to ask you about substance use and abuse in your community (i.e., prevalence):

|

We would also like to ask you about how the substances you’ve talked about affect your community (i.e., impact):

|

Next, we would like to ask you about the availability and effectiveness of substance abuse treatment in your community (i.e., treatment availability):

|

We also think it is important to ask you about how your community’s culture might help prevention or treatment of substance abuse (i.e., culture):

|

Finally, we would also like to learn about what your community does to prevent substance abuse (i.e., prevention):

|

All interviews were audio-recorded with each interviewee’s permission and transcribed verbatim, and each interviewee received his/her transcript to review and edit for accuracy or removal of any remaining information that might identify the interviewee or community. To extract key themes and representative quotations from the 10 transcripts, three study staff independently read each transcript and noted primary themes and other valuable information (e.g., quotes, outliers), and then discussed the similarities and discrepancies in their reviews to determine what to include in the report. The report was sent as a draft to each interviewee for his/her review and suggestions and was considered final after 3 individuals sent positive comments and the other 7 did not respond.

TARGET Analysis Methods

State treatment admission data (TARGET) were analyzed for individuals who identified their tribal affiliation as one of 11 participating AIAN communities to explore admissions rates by primary drug compared to non-AIANs. Primary drug is generally determined by the person entering data and may be ascertained differently by different intake workers. TARGET is a web-based management and reporting system of DBHR client services that generally includes data obtained at intake into publicly funded substance use/abuse treatment and for all admissions into methadone maintenance treatment. Differences may exist across Tribes in terms of which clients are entered into the system with some just entering publicly funded clients and others also including non-publicly funded clients.

Data were analyzed for admissions between 2002 and 2008. Admissions are duplicated, that is, a person could enter treatment multiple times over the study period. To be included in the data analysis, we required verbal or written communication from each Tribal community of their willingness to participate; no communities that declined (only one declined) or did not respond to the invitation were included.

For these descriptive analyses two groups were constructed. The Native American group included all who self-reported their tribal affiliation as one of the 11 tribes that actively agreed to be part of this data analysis. Individuals entering treatment with one of these 11 tribal affiliations represented a total of 16% of individuals who reported any tribal affiliation in TARGET. The comparison group included all other people admitted to treatment, excluding individuals with tribal affiliations that were the same as the tribes that did not agree to participate in this analysis. There were no inclusion or exclusion criteria related to the types of facilities, rather, the tribal affiliations of individuals were the sole inclusion/exclusion criteria. Statistical tests of differences between groups are not provided because the proportion of Native Americans included among all known to have entered treatment is small and the proportions attending different modalities of care vary, potentially introducing unknown biases.

RESULTS

Substance Use and Intervention/Recovery Trends from HD Interviews

According to the perspectives of the ten interviewees, methamphetamine use/abuse peaked in 2005–2006 and then declined, and alcohol “held steady.” As of the time of interviews in 2009, prescription medications, especially opioids, were reported as the primary current concern, although alcohol and marijuana were seen as the most prevalent substances of abuse. Interviewees reported alarm at the rise in prescription medication use/abuse as these substances appear to be more available and accessible, used by many young people in their 20s and 30s, and especially damaging to family structures and the social and cultural “fabric” of entire communities. Interviewees associated methamphetamine use with “acting out behaviors” and prescription medications with isolation, theft and lack of communication. They associated both methamphetamines and prescription medications with increased crime rates, including theft, burglary, and violence. Illustrative quotations include:

-

▪

“We have gone through different times in the past where we had a lot of alcohol and then we went to marijuana and then we went to cocaine, and now we are on prescription meds.”

-

▪

“Alcohol, like I said, is still our number one problem…”.

-

▪

“But when opiate use is involved it seems to damage the family structure even greater, even more so than alcohol, and some of that has to do with the effects of Oxycontin. The effects are that people stay wasted for pretty long periods of time and when they fall asleep they are really out, and they don’t care for their children. They don’t take care of some of the basic needs.”

Interviewees also reported positive trends in substance use/abuse interventions and recovery. Positive progress nurtures hope, community involvement, and commitment to health promotion and wellness in many communities with resulting improved substance use/abuse treatment services, prevention, and recovery opportunities. Interviewees described an ongoing revitalization of Native/tribal culture through reconnection with cultural history, traditional Native practices, and cultural ways as an important part of substance use/abuse recovery and overall community health and wellness. For example, some communities addressed the past methamphetamine problem “head on” with community campaigns and experienced positive results by using “cultural strengths and cultural ways of working with people.” Furthermore, interviewees reported that those in need have more treatment options, individualized program planning, recovery education, and family support and involvement than in the past.

-

▪

“I do think that a big part of the answer to this is going to be community-based because of our culture. We are used to relying on each other.”

-

▪

“…colonization happened and so many people got away from their tribal ways, and now they’re reclaiming that.”

-

▪

“Canoe journeys, sweat lodge, smudging, drumming circles, hugely getting back to that culture…there are values being taught, there is knowledge, there is tradition being passed down.”

Interviewees reported that much progress is still needed and is severely limited by a lack of funding and other resources. Access to care is a critical issue, including the ability to get individuals into treatment programs at all, and culturally appropriate ones specifically. In addition, considering the current prescription medication situation, adequate and alternative pain management is needed. To illustrate continuing needs:

-

▪

“More funding is always great—what we need is more people who have the same goal, the same vision, the same energy as a lot of the people that we’ve already implemented into those jobs. Those people that are going to be there day in and day out, being consistent.”

-

▪

“…give us ideas that are maybe culturally appropriate and effective in working with our community and creating the energy within the community to stand up and take action.”

Finally, although primary/common themes are described above, there were some notable differences among the diverse communities. Available and accessible substance abuse treatment resources, programs, and prevention efforts varied widely, due in part to geographic location and funding. In addition, a few interviewees reported that methamphetamine is still a concern in their communities, although not the largest concern.

Treatment Admissions, TARGET

Drug treatment admissions data can help provide insight into both the demand for and access to treatment. From 2002 to 2008 there were a total of 4,851 admissions reported in TARGET from the 11 participating Native American groups and a total of 363,172 for the comparison group. The total number of Native American youth admissions reported in TARGET was just 681, with the proportion of youth entering each of the modalities of care being quite similar to the comparison group. Admissions for adult Native Americans totaled 4,161 and the proportion entering each of the modalities of care was quite different from the comparison group for certain modalities. For instance, 12% of Native Americans compared to 26% of the comparison group were admitted to Detoxification. Conversely, 35% of Native Americans were admitted to outpatient treatment compared to 26% of the comparison group. Overall, youth treatment admission numbers held steady over time. For adults in the comparison group there was a 41% increase in the number of admissions from 2002 to 2008 and for the Native American group the increase was 141%.

Patterns for the primary drug over time for youth were similar for both groups; marijuana was the primary drug for a majority of youth, followed by alcohol. The number of admissions for other substances for Native American youth was too small to comment on trends. For non-Native American youth methamphetamine was the third most common drug, increasing from 2002 to 2005 and then declining substantially through 2008. Other opiates (i.e. pharmaceutical opiates such as morphine, Vicodin, OxyContin and methadone) increased from 0.4% (n=24) to 3.0% (n=193) from 2002 to 2008 for non-Native American Youth.

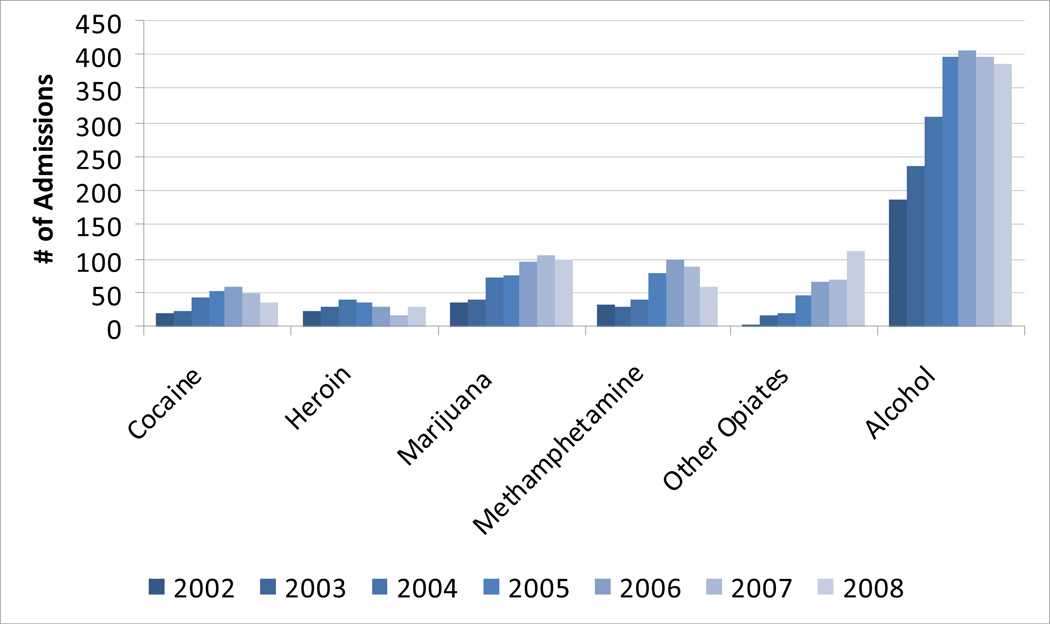

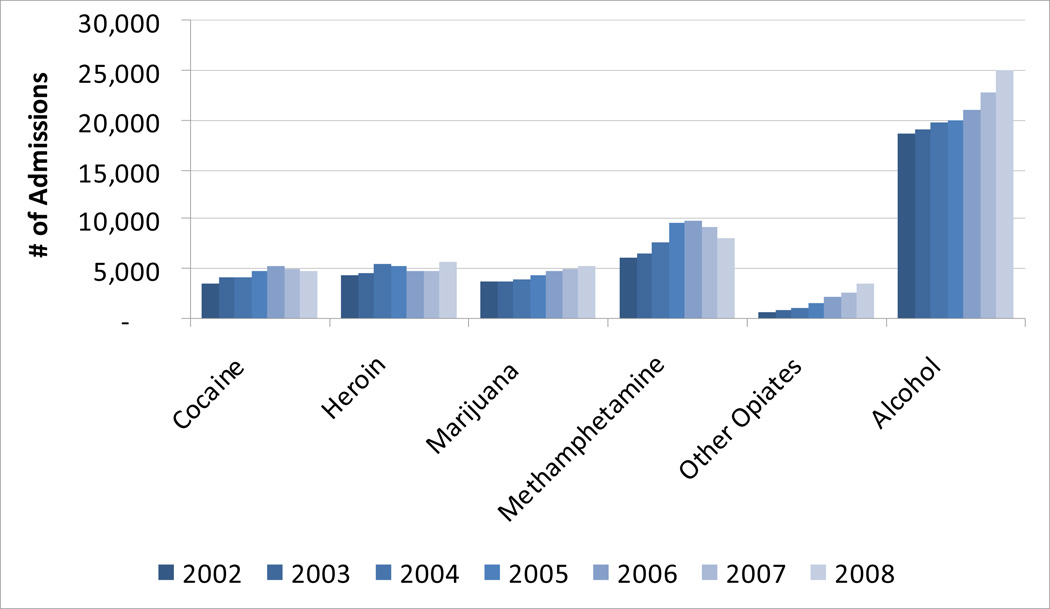

Alcohol was by far the most common primary drug for adults admitted to treatment, both Native American and non-Native American (Figures 1 and 2). From 2002 to 2008, alcohol was the primary drug for 56% of Native American admissions compared to 46% for non-Native Americans. For Native American admissions the second most common primary drug was other opiates in 2008, with 111 (15%) of 736 admissions, up from 3 of 306 admissions in 2002. For non-Native American admissions, other opiates had the greatest proportional increase in admission rate, but the overall proportion was much lower, 6.5% of admissions in 2008. For Native American admissions, marijuana was the third most common substance in 2008, with a generally increasing number of admissions in each year. For non-Native American admissions there was also an increasing trend in marijuana admissions, but it was much more modest and the overall rank in 2008 was fourth among substances. Methamphetamine increased substantially for both groups until peaking in 2006 and subsequently declining. In 2006, methamphetamine was the second most common drug at admission for Native American admissions with 100 of 768 admissions, however by 2008 it declined to a rank of fourth with 59 of 736 admissions.

Figure 1.

Adult Native American Treatment Admissions in WA State by Primary Drug

Figure 2.

Adult Non-Native American Treatment Admissions in WA State by Primary Drug

Other opiates increased the greatest proportion of any drug among adults in both groups, from 1% to 15% for Native American admissions and from 2% to 7% for non-Native American admissions from 2002 to 2008. Other data indicate a particular problem among youth and young adults, so additional analyses by age were conducted. Youth were excluded because of the very small number of treatment admissions. Numbers are also small for Native American adults and should be viewed cautiously. For both groups the largest proportion of admissions for other opiates from 2006 through 2008 were among those ages 18–24. This young adult group represented 41% of admissions for other opiates in 2008 among Native American admissions and 33% among non-Native American admissions (the difference is not substantial given the small number of admissions). Sixty-two percent of admissions for other opiates among Native American admissions and 60% of non-Native American admissions in 2008 were among those ages 18–29.

LIMITATIONS

Due to limited recruitment and participation in HD interviews and treatment admissions data analyses, findings are limited to those tribal communities or community members in WA State who agreed to participate. Although participating communities did represent a reasonable geographical cross-section of tribal communities in terms of location across the state and population size, AIAN communities are diverse in many ways (e.g., there are 29 federally recognized WA State Tribes with unique histories, cultures, and sociopolitical contexts); therefore, it is important to note that this information applies only to communities that participated in the study, and only from the perspectives of interviewees and available treatment admissions data. In addition, the TARGET data are descriptive and statistical tests were not conducted because of known limitations and biases in how the Native American group was developed for these analyses and the inability to adjust for these limitations statistically because of the nature of the data. The degree to which these data represent treatment demand versus access (e.g., geographic, financial, cultural) cannot be determined. It is possible that bias could have been introduced by using duplicated data given differences in the proportion of admissions to different modalities of care; a larger proportion of comparison group admissions were to detox and a smaller proportion to outpatient compared to the Native American group. The differences may have roughly balanced each other out, but it is not possible to know if systematic bias was introduced by utilizing duplicated admissions. However, duplicated admissions are important because they give a sense of the service utilization, not just the number of individuals. Furthermore, the potential for bias exists in whether people self-reported as AIAN race. Any self-report biases would most likely be for people to under-report AIAN race (and therefore not provide a tribal affiliation). In this case, those persons would be included in the comparison group and this would likely lead to less differences between the groups.

CONCLUSION

Findings from the HD interviews and TARGET analyses provide an initial picture of a number of diverse AIAN communities in Washington State, suggesting common substance use/abuse trends, as well as positive trends in treatment and recovery and continuing needs. As sample sizes for both HD Interviews and TARGET were modest, care must be taken not to draw conclusions that extend beyond the participating individuals and communities.

Both studies suggest that methamphetamine use/abuse and concern about it peaked around 2005–2006 and then declined; however, in some communities it remains a current concern. Findings also suggest that alcohol continues to be a primary concern in all communities, and accounted for the greatest number of publicly funded treatment admissions during the 2002–2008 period. In addition, both analyses indicate that use/abuse of prescription medications, especially opiates, is a growing trend with many real and potential long-lasting harms to individuals, families, and communities. These findings are consistent with other WA State reports indicating that AIANs have the highest rate of unmet treatment need and a disproportionately high rate of admissions for prescription-type opiates (22).

In addition, community wellness/health is tied to community involvement and support and access to resources and services that incorporate culturally appropriate and effective interventions. Strong and hopeful communities with a shared sense of responsibility and focus can support recovery for individuals and communities. As communities reclaim stolen culture and use cultural ways to promote hope and overall wellness for their people, culture and spirituality are also being incorporated into addressing substance use/abuse through appropriate and effective prevention and treatment. Finally, participants shared that how substance use/abuse issues are approached is vital. If efforts are framed in positive, strength-based terms to strive for wellness, this is much more effective and acceptable than targeting “problems” and “issues.”

SCIENTIFIC SIGNIFICANCE

Recognizing and developing appropriate and effective research methods is necessary to obtain AIAN community-based data about current substance use/abuse and related trends in order to inform future efforts to ameliorate these and other health disparities. These exploratory studies were examples of modified CBPR and TPR approaches that utilized both qualitative and quantitative data to answer similar research questions. Consistency in trends found in both HD and TARGET studies suggests that we can be fairly confident in their accuracy. The analyses provided many lessons that were shared with study participants and advisory groups who could then utilize the information to guide timely prevention and treatment. Additionally, findings reinforced our beliefs about developing collaborative working relationships with AIAN communities (13). The research process varies with each community and study, requires a significant investment of time and effort, may succeed with attention and adherence to both formal and informal community protocols, procedures, and expectations (e.g., review and approval, time spent to build trust), and demands flexibility in researchers and research plans. Of utmost importance, recognize that communities are engaged in many high priority endeavors to meet their members’ needs and ensure that research is a positive experience with tangible benefits for participating communities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network. The authors acknowledge the generous contributions by the participating individuals, communities, and advisory organizations.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

Contributor Information

Sandra M. Radin, University of Washington.

Caleb J. Banta-Green, University of Washington.

Lisa R. Thomas, University of Washington.

Stephen H. Kutz, Cowlitz Indian Tribe.

Dennis M. Donovan, University of Washington.

REFERENCES

- 1.Noe T, Fleming C, Manson S. Healthy nations: Reducing substance abuse in American Indian and Alaska Native communities. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(1):15–25. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10399989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.May PA. Overview of alcohol abuse epidemiology for American Indian populations. In: Sandefur G, Rindfuss R, Cohen B, editors. Changing numbers, changing needs: American Indian demography and public health. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996. pp. 235–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nachreiner D. Washington State health disparities in Indian Country. American Indian Health Commission. 2002 Position paper. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strickland CJ. The importance of qualitative research in addressing cultural relevance: experiences from research with Pacific Northwest Indian women. Health Care Women Int. 1999;20(5):517–525. doi: 10.1080/073993399245601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forcehimes A, Venner K, Bogenschutz M, Foley K, Davis M, Houck J, et al. American Indian methamphetamine and other drug use in the Southwestern United States. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2011;17(4):366–376. doi: 10.1037/a0025431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Washington State Division of Alcohol and Substance Abuse. Tobacco, alcohol, and other drug abuse trends in Washington State: 2005 report. Olympia: Washington State Department of Social and Health Services; 2005. Dec, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akins S, Mosher C, Rotolo T, Griffin R. Patterns and correlates of substance use among American Indians in Washington State. Journal of Drug Issues. 2003;33(1):45–71. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beals J, Manson S, Whitesell N, Spicer P, Novins D, Mitchell C. Prevalence of DSM-IV disorders and attendant help-seeking in 2 American Indian reservation populations. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(1):99–108. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Office of Applied Studies. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH): Substance use and substance use disorders among American Indians and Alaska Natives: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2007 Jan 19; 2007.

- 10.Office of Applied Studies. The DASIS report: American Indian / Alaska Native Treatment Admissions in Rural & Urban Areas 2000: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

- 11.Fisher P, Ball T. Tribal Participatory Research: Mechanisms of a Collaborative Model. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;32(3/4):207–216. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000004742.39858.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Community-based participatory research: Engaging communities as partners in health research; Community-Campus Partnerships for Health’s 4th Annual Conference; 2000 April 29; Washington, DC. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas L, Rosa C, Forcehimes A, Donovan D. Research partnerships between academic institutions and American Indian and Alaska Native tribes and organizations: Effective strategies and lessons learned in a multisite CTN study. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2011;37:333–338. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.596976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenstock L, Hernandez L, Gebbie K, editors. Educating public health professionals for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. Who will keep the public healthy? [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caldwell JY, Davis JD, DuBois B, Echo-Hawk H, Erickson JS, Goins RT, et al. Culturally competent research with American Indians and Alaska Natives: Findings and recommendations of the first symposium of the work group on American Indian research and program evaluation methodology. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 2005;12(1):1–21. doi: 10.5820/aian.1201.2005.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cashman SB, Adeky S, Allen AJ, III, Corburn J, Israel BA, Montano J, et al. The Power and the promise: Working with communities to analyze data, interpret findings, and get to outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(8):1407–1417. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.113571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christopher S, Watts V, McCormick AK, Young S. Building and maintaining trust in a community-based participatory research partnership. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(8):1398–1406. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.125757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cochran PA, Marshall CA, Garcia-Downing C, Kendall E, Cook D, McCubbin L, et al. Indigenous ways of knowing: Implications for participatory research and community. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(1):22–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.093641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minkler M, Hancock TSe. Community-driven asset identification and issue selection. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes. Second ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008. pp. 153–169. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis SM, Reid R. Practicing participatory research in American Indian communities. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69(4 Suppl):755S–759S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.4.755S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas LR, Donovan DM, Sigo RLW, Price L. Community based participatory research in Indian Country: Definitions, theory, rationale, examples, and principles. In: Sarche MC, Spicer P, Farrell P, Fitzgerald HE, editors. American Indian children and mental health: Development, context, prevention, and treatment. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, LLC; 2011. pp. 165–187. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tobacco, alcohol, and other drug abuse trends in Washington State 2010 report. 2010. Washington State Division of Behavioral Health and Recovery. [Google Scholar]