Abstract

The diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is an increasingly common event due to widespread use of screening mammography. However, appropriate clinical management of DCIS is a major challenge in the absence of prognostic markers. Tumor-initiating cells may be particularly relevant for disease pathogenesis; therefore, two markers associated with such cells, EZH2 and ALDH1, were evaluated. A cohort of 248 DCIS patients was used to determine the association of EZH2 and ALDH1 with ipsilateral breast event, DCIS recurrence and progression to invasive breast cancer (IBC). In this cohort, high EZH2 expression was associated with the risk of an ipsilateral breast event and DCIS recurrence but not invasive progression. ALDH1 expression was observed in both the tumor and stromal compartment; however, in neither compartment were ALDH1 levels independently associated with evaluated study endpoints. Interestingly, the combination of high EZH2 with high epithelial ALDH1 was associated with disease progression. Therefore, ALDH1 within the DCIS lesion can add to the prognostic significance of EZH2, particularly in the context of risk of development of invasive disease.

Keywords: ALDH1, DCIS, EZH2, IBC, ductal carcinoma in situ, invasive breast cancer, prognostic markers, tumor-initiating cells

Introduction

The incidence of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) has increased dramatically over the last few decades. In the 1970s, 1–2% of newly diagnosed breast cancers were DCIS, while in 2005 this number had increased to 25%. The rise in the incidence and prevalence of DCIS is attributed to the increasing use of screening mammography.1-3 DCIS is a proliferation of malignant epithelial cells that is confined to the lumen of mammary ducts without invasion through the basement membrane. The latter is the trait that differentiates DCIS from invasive breast carcinoma (IBC). DCIS is considered a nonobligatory precursor to IBC.1,2 Both DCIS and IBC have similar risk factors, such as older age, family history of breast cancer, late age at menopause, nulliparity and late age at first birth.2,3 The reason why some DCIS progress to IBC and others do not remains unresolved. Thus, there is great interest in the medical community to uncover prognostic markers for defining DCIS cases that are at risk of progression to IBC.

Tumor-initiating cells may be particularly relevant for breast cancer development and progression.4,5 Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) and aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1), two markers evaluated in this study, have been implicated in stem cell maintenance and renewal.6-11 It has been shown that upregulation of EZH2 results in transcriptional repression of key target genes involved in differentiation, proliferation, cell fate and DNA repair mechanisms.11-13 These aberrations could drive the neoplastic process and also are important for stem cell renewal.7,11 EZH2 is deregulated by complex mechanisms in cancer and has diverse functional impacts related to development and cancer.14-17 Consistent with such a concept, EZH2 expression was shown to progressively increase from normal breast tissue to atypical ductal hyperplasia, DCIS and IBC, suggesting that EZH2 protein levels increase as breast cancer develops.18-20 Additionally, elevated EZH2 expression was detected in benign appearing breast epithelium from prophylactic mastectomies in women with BRCA1 mutation, indicating that EZH2 might predict increased risk for breast cancer.19

ADLH1 expression has been employed for identification of human cancer stem cells.21-23 ALDH1 plays a functional role in stem cell differentiation by conversion of retinol to retinoic acid.24,25 Expression of ALDH1 in IBC was associated with large tumor size, higher histological grade and shorter overall survival in several studies. ALDH1-positive cells were also more frequent in basal-like and HER2-positive IBC than in luminal tumors, indicating that presence of these cells is associated with more aggressive subtypes of IBC.26 When DCIS and IBC coexisting in the same tumor were evaluated, the frequency of cells positive for ALDH1 appeared to be the same in the in situ and invasive areas of the tumor.26

Currently, there are no data on ALDH1 and EZH2 expression in DCIS in relation to disease recurrence and progression to IBC. The aim of this study was to evaluate the expression EZH2 and ALDH1 in a large cohort of DCIS patients treated at one institution with wide-excision surgery and correlate the expression of these markers with disease outcome.

Results

Both EZH2 and ALDH1 are associated with tumor-initiating cells that portend poor prognosis in IBC and could contribute to disease progression in breast cancer.11,23 To determine the association of EZH2 and ALDH1 with DCIS outcome, a cohort of 236 patients was evaluated. The clinicopathological features of this cohort are summarized in (Table 1). EZH2 expression could be evaluated in 169 cases. Staining for ALDH1 could be evaluated in 164 (stromal expression) and 176 (epithelial expression) cases.

Table 1. Clinicopathological features of patient cohort portrayed the association of EZH2 and ALDH1 with DCIS outcome.

| Variable | Distribution No. (%) | IBE No (%) | DCIS recurrence No. (%) | Invasive recurrence No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Age |

|

|

|

|

| Under 50 |

69 (29%) |

23 (33%) |

14 (20%) |

9 (13%) |

| Over 50 |

167 (71%) |

52 (31%) |

34 (20%) |

18 (11%) |

| p-value |

|

|

|

|

|

Necrosis |

|

|

|

|

| No |

111 (47%) |

35 (32%) |

23 (21%) |

12(11%) |

| Yes |

125 (53%) |

40 (32%) |

25 (20%) |

15 (12%) |

| p-value |

|

|

|

|

|

Nuclear grade |

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

51 (22%) |

14 (28%) |

7 (14%) |

7 (14%) |

| 2 |

112 (47%) |

40 (36%) |

28 (25%) |

12 (11%) |

| 3 |

73 (31%) |

21 (29%) |

13 (18%) |

8 (11%) |

| p-value |

|

|

|

|

|

Tumor size |

|

|

|

|

| Microfocal and Focal and < 1.0 cm |

113 (69%) |

34 (30%) |

20 (18%) |

14 (12%) |

| 1.00+cm |

50 (31%) |

14 (32%) |

8 (16%) |

6 (16%) |

| p-value |

|

|

|

|

|

Comedo |

|

|

|

|

| No |

158 (67%) |

48 (30%) |

30 (19%) |

18 (11%) |

| Yes |

78 (33%) |

27 (35%) |

18 (23%) |

9 (12%) |

| p-value |

|

|

|

|

|

HER2 |

|

|

|

|

| 0 |

64 (30%) |

19 (29%) |

13 (20%) |

6 (9%) |

| 1+ |

64 (30%) |

20 (32%) |

10 (16%) |

10 (16%) |

| 2+ |

25 (12%) |

4 (12%) |

2 (8%) |

2 (4%) |

| 3+ |

60 (28%) |

24 (4%) |

19 (32%) |

5 (8%) |

| p-value |

|

|

|

|

|

PR |

|

|

|

|

| Negative |

49 (22%) |

18 (36%) |

11 (22%) |

7 (14%) |

| Positive |

174 (78%) |

54 (31%) |

35 (20%) |

19 (11%) |

| p-value |

|

|

|

|

|

ER |

|

|

|

|

| Negative |

34 (15%) |

9 (27%) |

6 (18%) |

3 (9%) |

| Positive |

200 (85%) |

66 (33%) |

42 (21%) |

24 (12%) |

| p-value |

EZH2 is associated with ipsilateral breast event and DCIS recurrence

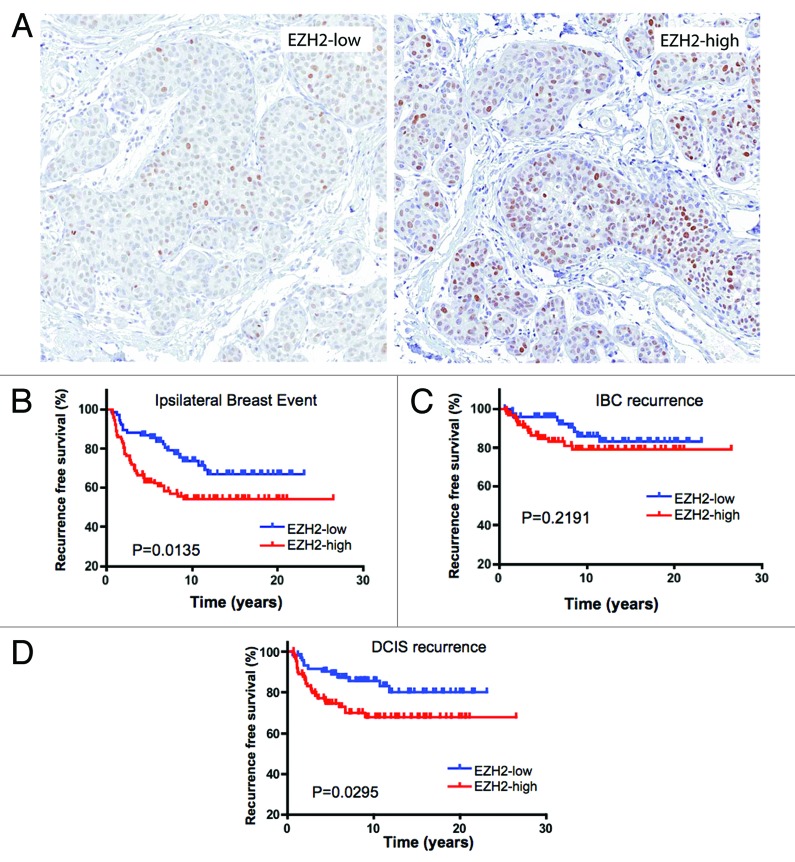

EZH2 staining localized to the nucleus. DCIS lesions exhibited a labeling index ranging from 0–100% (Fig. 1A). For statistical analyses, the data were dichotomized, with greater than 15% positive cells defining high expression. With this criteria, 55% of cases had elevated EZH2 expression. In the cohort analyzed, DCIS lesions with high expression of EZH2 were at significantly increased risk of an ipsilateral breast event (Table 2 and Fig. 1B). Since both DCIS recurrence and progression to invasive breast cancer define ipsilateral breast events, these endpoints were analyzed independently. Interestingly, while high EZH2 was associated with DCIS recurrence (Table 2 and Fig. 1D), it was not statistically associated with invasive progression (Table 2 and Fig. 1C). In multivariate analyses EZH2 remained prognostically significant for ipsilateral breast event (Table 2).

Figure 1. EZH2 is associated with risk of IBE and DCIS recurrence: (A) Representative images of EZH2 expression in DCIS. (B) Kaplan-Meier analyses of EZH2 status relative to IBE in the cohort analyzed. (C) Kaplan-Meier analyses of EZH2 status relative to IBC recurrence in the cohort analyzed. (D) Kaplan-Meier analyses of EZH2 status relative to DCIS recurrence in the cohort analyzed.

Table 2. EZH2 is associated with ipsilateral breast events and DCIS recurrence.

| IBE-free rate | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Year |

EZH2-low |

EZH2-high |

| 1 |

99% |

92% |

| 2 |

89% |

81% |

| 5 |

87% |

63% |

| 10 |

74% |

54% |

| 15 |

67% |

54% |

| HR = 1.92(1.13, 3.25) p = 0.015 | ||

| IBC recurrence-free rate | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Year |

EZH2-low |

EZH2-high |

| 1 |

100% |

97% |

| 2 |

96% |

93% |

| 5 |

96% |

85% |

| 10 |

86% |

79% |

| 15 |

83% |

79% |

| HR = 1.67 (0.73, 3.82), p = 0.22 | ||

| DCIS recurrence-free rate | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Year |

EZH2-low |

EZH2-high |

| 1 |

99% |

96% |

| 2 |

93% |

87% |

| 5 |

90% |

75% |

| 10 |

86% |

68% |

| 15 |

80% |

68% |

| HR = 2.10 (1.06, 4.17), p = 0.030 | ||

| EZH2 - forward selection with the Cox Model (IBE) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Variable |

Subgroups |

p-value |

| EZH2 |

Positive vs. Negative |

0.015 |

| Age |

< 50 vs. > 50 y old |

0.75 |

| Necrosis |

No vs Yes |

0.71 |

| Nuclear Grade |

1–2 vs 3 |

0.79 |

| Comedo | No vs Yes | 0.56 |

ALDH1 expression is not independently associated with ipsilateral breast event

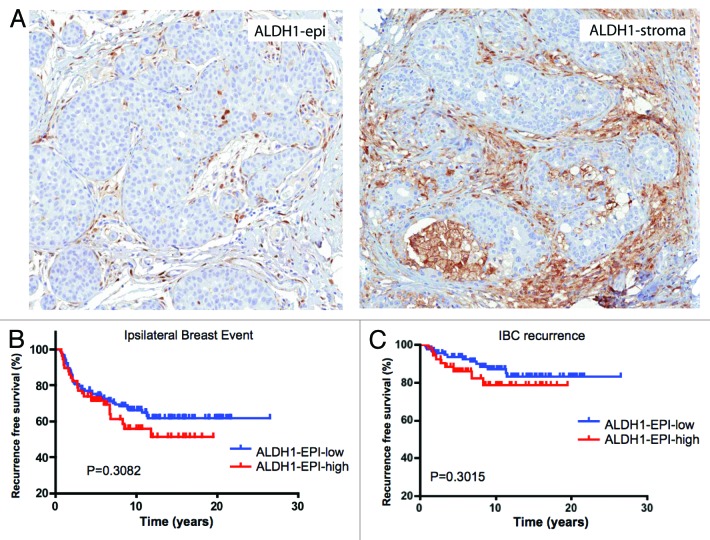

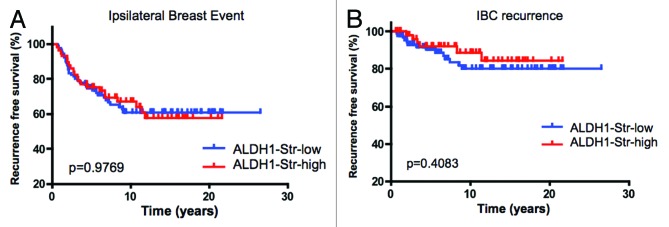

ALDH1 is an established marker of breast cancer tumor-initiating cells.23 By immunohistochemical analyses the staining for ALDH1 was observed in both DCIS epithelial cells and the associated stroma (Fig. 2A). These data suggested that ALDH1 could have distinct effects on the tumor and microenvironment that could differentially affect DCIS pathogenesis. In the analyses of ALDH1 staining in the DCIS epithelial cells, 33% of lesions scored positive for this marker. For epithelia that are ALDH1-positive, there was an increased trend for ipsilateral breast event, but it was not statistically significant (Fig. 2B and Table 3). Similarly, there was no significant association when DCIS recurrence and invasive progression were analyzed separately (Fig. 2B and C and Table 3). Thus, ALDH1 expression within the DCIS epithelial cells was not an independent prognostic marker in our cohort. To determine the influence of stromal ALDH1 expression, the association with clinical outcome in DCIS was evaluated. This marker was present in the stroma of 39% of DCIS cases but had no association with disease outcome (Fig. 3 and Table 3).

Figure 2. ALDH1 expression within DCIS is not associated with clinical outcome in DCIS: (A) Representative images of ALDH1 expression in DCIS epithelia and stroma (B) Kaplan-Meier analyses of ALDH1 status relative to IBE in the cohort analyzed. (C) Kaplan-Meier analyses of EZH2 status relative to IBC recurrence in the cohort analyzed.

Table 3. ALDH1 expression is not independently associated with ipsilateral breast events.

| IBE-free rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Year |

ALDH1 (Str-low Str-high) |

ALDH1 (Epi-low Epi-high) |

||

| 1 |

98% |

96% |

97% |

91% |

| 2 |

87% |

88% |

85% |

84% |

| 5 |

76% |

76% |

74% |

71% |

| 10 |

64% |

69% |

65% |

55% |

| 15 |

64% |

58% |

62% |

50% |

| HR = 1.07(0.64, 1.81) p = 0.79 | HR = 1.31(0.79, 2.17) p = 0.29 | |||

| IBC recurrence-free rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year |

ALDH1 (Str-low Str-high) |

ALDH1 (Epi-low Epi-high) |

||

| 1 |

98% |

98% |

97% |

98% |

| 2 |

94% |

97% |

95% |

94% |

| 5 |

90% |

92% |

93% |

86% |

| 10 |

81% |

89% |

86% |

76% |

| 15 |

81% |

85% |

84% |

76% |

| HR = 0.69 (0.28, 1.67) p = 0.41 | HR = 1.65 (0.73, 3.72) p = 0.23 | |||

| DCIS recurrence-free rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year |

ALDH1 (Str-low Str-high) |

ALDH1 (Epi-low Epi-high) |

||

| 1 |

100% |

97% |

99% |

93% |

| 2 |

92% |

91% |

90% |

89% |

| 5 |

85% |

83% |

80% |

82% |

| 10 |

79% |

77% |

76% |

73% |

| 15 |

79% |

68% |

74% |

67% |

| HR = 1.40 (0.73, 2.69) p = 0.31 | HR = 1.14 (0.60, 2.18) p = 0.69 | |||

Figure 3. Stromal ALDH1 expression is not associated with clinical outcome in DCIS: (A) Kaplan-Meier analyses of ALDH1 status relative to IBE in the cohort analyzed. (B) Kaplan-Meier analyses of ALDH1 status relative to IBC recurrence in the cohort analyzed.

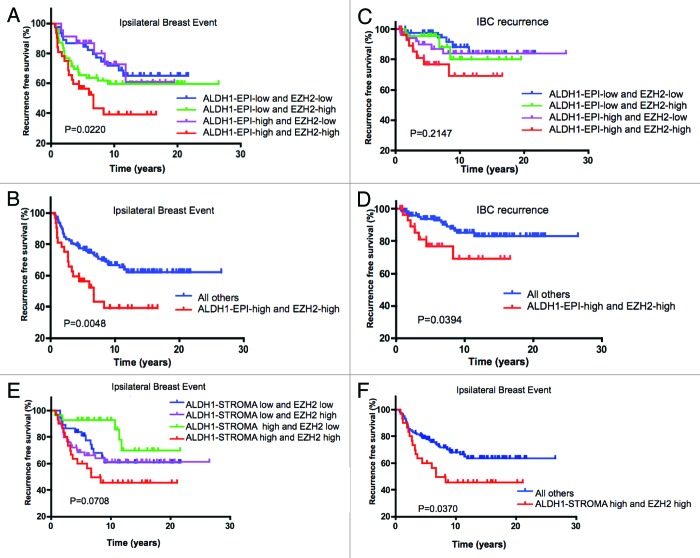

Coordinate EZH2/ALDH1 status in the tumor epithelial compartment provides added prognostic value

While ALDH1 had no independent association with disease outcome, it is possible that the combination of EZH2 and ALDH1 could define DCIS cases that were enriched for cells with tumor-initiating properties and therefore harbored distinct clinical outcome. Stratification of DCIS by both EZH2 and ALDH1 expression in the tumor epithelial compartment defined cases that were at increased risk for IBE relative to EZH2 status alone (Fig. 4A and Table 4). Importantly, incorporation of ALDH1 status also increased the prognostic power related to IBC development, such that those DCIS lesions that were positive for both EZH2 and ALDH1 in the tumor epithelial compartment were significantly associated with disease progression (Fig. 4B and Table 4). While the epithelial expression of ALDH1 harbored significance in combination with EZH2, the inclusion of stromal ALDH1 had little effect and did not increase the prognostic association for IBE (Fig. 4 and Table 5), DCIS and IBC recurrence (Table 5 and data not shown). Together, these data indicate that the combination of EZH2 with ALDH1 within the DCIS epithelial compartment is associated with prognosis for ipsilateral breast event and invasive progression.

Figure 4. Coordinate EZH2/ALDH1 status is associated with clinical outcomes in DCIS: (A) Kaplan-Meier analyses of ALDH1/EZH2 status relative to IBE in the cohort analyzed. (B) Kaplan-Meier analyses of high EZH2/ALDH1 vs. all other groups relative to IBE in the cohort analyzed. (C) Kaplan-Meier analyses of ALDH1/EZH2 status relative to IBC in the cohort analyzed. (D) Kaplan-Meier analyses of high EZH2/ALDH1 vs. all other groups relative to IBC in the cohort analyzed. (E) Kaplan-Meier analyses of stromal ALDH1/EZH2 status relative to IBE in the cohort analyzed. (F) Kaplan-Meier analyses of stromal ALDH1/EZH2 vs. all other groups relative to IBE in the cohort analyzed.

Table 4. Coordinate EZH2/ALDH1 status in the tumor epithelial compartment provides added prognostic value.

| IBE-free rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Year |

EZH2 low (ALDH1-epi-low) |

EZH2 low (ALDH1-epi-high) |

EZH2 high (ALDH1-epi low) |

EZH2 high (ALDH1-epi high) |

| 1 |

98% |

100% |

96% |

84% |

| 2 |

89% |

91% |

82% |

78% |

| 5 |

87% |

87% |

66% |

56% |

| 10 |

72% |

73% |

59% |

39% |

| 15 |

66% |

61% |

59% |

39% |

| p = 0.021 | HR = 0.99 (0.38, 2.64) p = 0.99 | HR = 1.65 (0.88, 3.07) p = 0.12 | ||

| IBC recurrence-free rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Year |

EZH2 low (ALDH1-epi-low) |

EZH2 low (ALDH1-epi-high) |

EZH2 high (ALDH1-epi low) |

EZH2 high (ALDH1-epi high) |

| 1 |

100% |

100% |

96% |

97% |

| 2 |

98% |

96% |

94% |

93% |

| 5 |

98% |

96% |

90% |

77% |

| 10 |

88% |

80% |

84% |

69% |

| 15 |

84% |

80% |

84% |

69% |

| p = 0.21* | HR = 1.45 (0.36, 6.03) p = 0.58 | HR = 2.03 (0.71, 5.79) p = 0.19 | ||

| DCIS recurrence-free rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Year |

EZH2 low (ALDH1-epi-low) |

EZH2 low (ALDH1-epi-high) |

EZH2 high (ALDH1-epi low) |

EZH2 high (ALDH1-epi high) |

| 1 |

98% |

100% |

100% |

87% |

| 2 |

91% |

95% |

87% |

84% |

| 5 |

89% |

91% |

73% |

73% |

| 10 |

81% |

91% |

70% |

57% |

| 15 |

78% |

76% |

70% |

57% |

| p = 0.12* | HR = 0.74 (0.20, 2.75) p = 0.65 | HR = 1.47 (0.67, 3.20) p = 0.33 | ||

Table 5. Stromal ALDH1 does not increase the prognostic association of EZH2 with IBE, DCIS and IBC recurrence.

| IBE-free rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Year |

EZH2 low (ALDH1-str-low) |

EZH2 low (ALDH1-str-high) |

EZH2 high (ALDH1-str-low) |

EZH2 high (ALDH1-str-high) |

| 1 |

100% |

96% |

96% |

97% |

| 2 |

89% |

93% |

83% |

87% |

| 5 |

84% |

93% |

68% |

60% |

| 10 |

61% |

93% |

61% |

46% |

| 15 |

61% |

70% |

61% |

46% |

| p = 0.07* | HR = 0.49 (0.17, 1.37) p = 0.17 | HR = 1.48 (0.77, 2.85) p = 0.25 | ||

| IBC recurrence-free rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Year |

EZH2 low (ALDH1-str-low) |

EZH2 low (ALDH1-str-high) |

EZH2 high (ALDH1-str-low) |

EZH2 high (ALDH1-str-high) |

| 1 |

100% |

100% |

100% |

96% |

| 2 |

97% |

100% |

96% |

92% |

| 5 |

97% |

100% |

84% |

86% |

| 10 |

80% |

100% |

77% |

80% |

| 15 |

80% |

91% |

77% |

80% |

| p = 0.32* | HR = 0.25 (0.03, 2.14) p = 0.21 | HR = 1.02 (0.34, 3.06) p = 0.96 | ||

| DCIS recurrence-free rates | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Year |

EZH2 low (ALDH1-str-low) |

EZH2 low (ALDH1-str-high) |

EZH2 high (ALDH1-str-low) |

EZH2 high (ALDH1-str-high) |

| 1 |

100% |

96% |

100% |

97% |

| 2 |

92% |

93% |

90% |

90% |

| 5 |

86% |

93% |

80% |

72% |

| 10 |

76% |

93% |

77% |

59% |

| 15 |

76% |

77% |

77% |

59% |

| p = 0.19* | HR = 0.64 (0.19, 2.12) p = 0.54 | HR = 1.85 (0.80, 4.26) p = 0.15 | ||

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the expression of EZH2 and ALDH1 in DCIS and their prognostic value in predicting ipsilateral breast event, DCIS recurrence and progression to IBC. These two proteins are implicated as markers of tumor-initiating cells that would be hypothesized to be associated with an adverse prognosis.11,20 The data demonstrate a prognostic role for EZH2 that can be modified by the expression of ALDH1 within the DCIS lesion. There was no apparent prognostic significance to ALDH1 expression within the stromal environment surrounding the DCIS.

Markers that can be used to determine the risk of ipsilateral breast events and invasive progression in particular will be crucial to improve the treatment of DCIS. Currently, the management of patients with DCIS is difficult due to the uncertainty associated with disease course.2,3,27 While a substantial fraction of women can be cured by breast-conserving surgery, there are clearly DCIS cases that are prone to recurrence and progression to invasive disease that would benefit by more aggressive therapy. Due to this clinical heterogeneity of DCIS, many women are exposed to adjuvant therapies that may be of limited benefit in terms of overall survival and are not without significant side effects.

The interrogation of EZH2 was based on several known aspects of this protein. EZH2 is a part of the polycomb repressor complex 2 and is strongly associated with the functional maintenance of bivalent chromatin, which is a unique feature of stem cells.12,28 EZH2 is rarely detected in normal breast duct epithelium and, when present in normal tissue, is associated with increased risk of breast cancer development.19 Raaphorst et al. reported that EZH2 expression was increased in high-grade DCIS, but since there was not clinical outcome data for their DCIS patients, this finding could not be correlated with DCIS recurrence.29 Lastly, the expression of EZH2 is a transcriptional target of the RB/E2F pathway, which has also been implicated in DCIS recurrence and progression.30,31 Here we found that EZH2 expression was a marker for increased risk of IBE, and DCIS recurrence, but was not associated with risk for IBC progression. Such a finding is interesting, but not without prior precedence. For example, Her2 expression is associated with increased risk for IBE, but not invasive progression.32

ALDH1 has been proposed as a marker of cancer stem cells, and therefore would be anticipated to be associated with a deleterious clinical course. Consistent with this concept, Park et al. found that ALDH1 was significantly associated with ER-negative tumors in the cases of IBC alone or IBC with DCIS.26 Another study concluded that ALDH1 had strong prognostic value in breast cancer and correlated with other known histopathological factors.23 However, these findings are not without controversy, as several groups found that ALDH1 expression did not correlate with clinical parameters and was not an independent prognostic factor in breast cancer.10,33 In our cohort, we observed ALDH1 expression in both the DCIS epithelial compartment and the local stroma environment. ALDH1 protein levels in either compartment were not statistically associated DCIS recurrence or invasive progression, although ALDH1 expression with the DCIS lesion trended toward increased risk. These findings, using a relatively large patient cohort, clearly demonstrate little prognostic utility of ALDH1 expression as a single marker in DCIS.

Due to the complexity of disease, it is likely that only combinations of markers will yield sufficient sensitivity and specificity to be useful within the clinic. Therefore, we investigated the coordinate association of EZH2 and ALDH1 with IBE and invasive progression. These data showed that the presence of ALDH1 within the DCIS lesion increased the prognostic power of EZH2. Importantly, those tumors that expressed EZH2 and ALDH1 were also at statistically increased risk for IBC. This suggests that ALDH1 adds to the biology of EZH2 in defining a form of DCIS more likely to progress to invasive cancer.

Materials and Methods

Study population

The medical charts and surgical pathology of 236 DCIS patients treated at Thomas Jefferson University were obtained after approval by the Institutional Review Board. Only patients treated by surgical excision were included in the study, and excision was performed by the same surgeon (GFS). Patients treated with chemotherapy and/or radiation in addition to surgical excision were excluded. Patients with DCIS involving more than 1 quadrant were treated by mastectomy and were also excluded from this study. Negative margins (> 10 mm) were achieved at the conclusion of excision or re-excision, and removal of all suspicious calcifications was confirmed on post-operative mammography. The date of diagnosis and recurrence were defined as the date of surgery leading to the relevant pathologic diagnosis. The presence of DCIS/IBC or absence of disease at the last follow-up was established as the study endpoint. Median and mean follow up was 8.6 and 9.3 y, respectively, with 100 patients followed for over 10 y and 51 patients for over 15 y. For each case, the size, histological pattern (cribriform, solid, comedo, papillary, micropapillary), presence or absence of necrosis, and nuclear grade were evaluated. Patients who developed IBC within 6 mo of a DCIS diagnosis were excluded, because IBC was assumed to be part of their original disease and not a recurrence.

Immunohistochemistry and statistical analysis

Expression of EZH2 and ALDH1 was assessed by standard immunoperoxidase method with monoclonal antibodies against EZH2 (BD Biosciences, Mouse Monoclonal, Clone 11, 1:250) and ALDH1 (BD Biosciences, mouse monoclonal, clone 44, 1:5,000, DAB).19,20 The EZH2 expression was scored as high (nuclear expression present in > 15% of cells) vs. low (nuclear expression present in 0–15% cells). Stromal ALDH1 staining was scored as negative, weak, moderate or strong as previously described.10 Epithelial ALDH1 staining was scored as positive if any cell showed staining.

The recurrence rates were estimated by Kaplan-Meier method and compared by log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazards models were utilized to determine the univariate and multivariable hazard ratios (HR) for standard clinical and pathological variables. A forward stepwise procedure with the criterion of p < 0.05 was used to select individual variables for subsequent multivariate analysis. To test for interaction between EZH2 and ALDH1, a Cox model was used with the two main effects and the interaction term. p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant and were not adjusted for multiple testing. All analyses were performed with the use of SAS software (version 9.2; SAS Institute). The statistical tests performed were two-sided.

Procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Human Experimentation in the USA and in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding to AKW (RO1-CA163863) and ESK (RO1-CA129134).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Source of Support

Impact of ErbB2 and RB Pathways on DCIS Progression and Treatment.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/25065

References

- 1.Kuerer HM, Albarracin CT, Yang WT, Cardiff RD, Brewster AM, Symmans WF, et al. Ductal carcinoma in situ: state of the science and roadmap to advance the field. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:279–88. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.3103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Virnig BA, Tuttle TM, Shamliyan T, Kane RL. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: a systematic review of incidence, treatment, and outcomes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:170–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allegra CJ, Aberle DR, Ganschow P, Hahn SM, Lee CN, Millon-Underwood S, et al. National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference statement: Diagnosis and Management of Ductal Carcinoma In Situ September 22-24, 2009. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:161–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wicha MS. Breast cancer stem cells: the other side of the story. Stem Cell Rev. 2007;3:110–2, discussion 113. doi: 10.1007/s12015-007-0016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu S, Wicha MS. Targeting breast cancer stem cells. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4006–12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.5388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang CJ, Hung MC. The role of EZH2 in tumour progression. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:243–7. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang CJ, Yang JY, Xia W, Chen CT, Xie X, Chao CH, et al. EZH2 promotes expansion of breast tumor-initiating cells through activation of RAF1-β-catenin signaling. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:86–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dave B, Chang J. Treatment resistance in stem cells and breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2009;14:79–82. doi: 10.1007/s10911-009-9117-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakshatri H, Srour EF, Badve S. Breast cancer stem cells and intrinsic subtypes: controversies rage on. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2009;4:50–60. doi: 10.2174/157488809787169110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Resetkova E, Reis-Filho JS, Jain RK, Mehta R, Thorat MA, Nakshatri H, et al. Prognostic impact of ALDH1 in breast cancer: a story of stem cells and tumor microenvironment. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123:97–108. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0619-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chase A, Cross NC. Aberrations of EZH2 in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:2613–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simon JA, Lange CA. Roles of the EZH2 histone methyltransferase in cancer epigenetics. Mutat Res. 2008;647:21–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bracken AP, Pasini D, Capra M, Prosperini E, Colli E, Helin K. EZH2 is downstream of the pRB-E2F pathway, essential for proliferation and amplified in cancer. EMBO J. 2003;22:5323–35. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asangani IA, Harms PW, Dodson L, Pandhi M, Kunju LP, Maher CA, et al. Genetic and epigenetic loss of microRNA-31 leads to feed-forward expression of EZH2 in melanoma. Oncotarget. 2012;3:1011–25. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koh CM, Iwata T, Zheng Q, Bethel C, Yegnasubramanian S, De Marzo AM. Myc enforces overexpression of EZH2 in early prostatic neoplasia via transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms. Oncotarget. 2011;2:669–83. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marchesi I, Fiorentino FP, Rizzolio F, Giordano A, Bagella L. The ablation of EZH2 uncovers its crucial role in rhabdomyosarcoma formation. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:3828–36. doi: 10.4161/cc.22025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tatton-Brown K, Hanks S, Ruark E, Zachariou A, Duarte SdelV, Ramsay E, et al. Childhood Overgrowth Collaboration Germline mutations in the oncogene EZH2 cause Weaver syndrome and increased human height. Oncotarget. 2011;2:1127–33. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collett K, Eide GE, Arnes J, Stefansson IM, Eide J, Braaten A, et al. Expression of enhancer of zeste homologue 2 is significantly associated with increased tumor cell proliferation and is a marker of aggressive breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1168–74. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ding L, Kleer CG. Enhancer of Zeste 2 as a marker of preneoplastic progression in the breast. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9352–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kunju LP, Cookingham C, Toy KA, Chen W, Sabel MS, Kleer CG. EZH2 and ALDH-1 mark breast epithelium at risk for breast cancer development. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:786–93. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charafe-Jauffret E, Ginestier C, Iovino F, Wicinski J, Cervera N, Finetti P, et al. Breast cancer cell lines contain functional cancer stem cells with metastatic capacity and a distinct molecular signature. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1302–13. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charafe-Jauffret E, Ginestier C, Iovino F, Tarpin C, Diebel M, Esterni B, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1-positive cancer stem cells mediate metastasis and poor clinical outcome in inflammatory breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:45–55. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ginestier C, Hur MH, Charafe-Jauffret E, Monville F, Dutcher J, Brown M, et al. ALDH1 is a marker of normal and malignant human mammary stem cells and a predictor of poor clinical outcome. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:555–67. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ginestier C, Wicinski J, Cervera N, Monville F, Finetti P, Bertucci F, et al. Retinoid signaling regulates breast cancer stem cell differentiation. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:3297–302. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.20.9761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zeng XCS, Chen S, Huang H. Phosphorylation of EZH2 by CDK1 and CDK2: a possible regulatory mechanism of transmission of the H3K27me3 epigenetic mark through cell divisions. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:579–83. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.4.14722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park SY, Lee HE, Li H, Shipitsin M, Gelman R, Polyak K. Heterogeneity for stem cell-related markers according to tumor subtype and histologic stage in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:876–87. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schnitt SJ. Local outcomes in ductal carcinoma in situ based on patient and tumor characteristics. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010;2010:158–61. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kleer CG, Cao Q, Varambally S, Shen R, Ota I, Tomlins SA, et al. EZH2 is a marker of aggressive breast cancer and promotes neoplastic transformation of breast epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11606–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1933744100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raaphorst FM, Meijer CJ, Fieret E, Blokzijl T, Mommers E, Buerger H, et al. Poorly differentiated breast carcinoma is associated with increased expression of the human polycomb group EZH2 gene. Neoplasia. 2003;5:481–8. doi: 10.1016/s1476-5586(03)80032-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gauthier ML, Berman HK, Miller C, Kozakeiwicz K, Chew K, Moore D, et al. Abrogated response to cellular stress identifies DCIS associated with subsequent tumor events and defines basal-like breast tumors. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:479–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Witkiewicz AK, Rivadeneira DB, Ertel A, Kline J, Hyslop T, Schwartz GF, et al. Association of RB/p16-pathway perturbations with DCIS recurrence: dependence on tumor versus tissue microenvironment. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:1171–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.05.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rakovitch E, Nofech-Mozes S, Hanna W, Narod S, Thiruchelvam D, Saskin R, et al. HER2/neu and Ki-67 expression predict non-invasive recurrence following breast-conserving therapy for ductal carcinoma in situ. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1160–5. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurebayashi J, Kanomata N, Shimo T, Yamashita T, Aogi K, Nishimura R, et al. Marked lymphovascular invasion, progesterone receptor negativity, and high Ki67 labeling index predict poor outcome in breast cancer patients treated with endocrine therapy alone. Breast Cancer. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s12282-012-0380-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]