Abstract

Objectives

As buprenorphine treatment and illicit buprenorphine use increase, many patients seeking buprenorphine treatment will have had prior experience with buprenorphine. Little evidence is available to guide optimal treatment strategies for patients with prior buprenorphine experience. We examined whether prior buprenorphine experience was associated with treatment retention and opioid use. We also explored whether type of prior buprenorphine use (prescribed or illicit use) was associated with these treatment outcomes.

Methods

We analyzed interview and medical record data from a longitudinal cohort study of 87 individuals who initiated office-based buprenorphine treatment. We examined associations between prior buprenorphine experience and 6-month treatment retention using logistic regression models, and prior buprenorphine experience and any self-reported opioid use at 1, 3, and 6 months using non-linear mixed models.

Results

Most (57.4%) participants reported prior buprenorphine experience; of these, 40% used prescribed buprenorphine and 60% illicit buprenorphine only. Compared to buprenorphine-naïve participants, those with prior buprenorphine experience had better treatment retention (AOR=2.65, 95% CI=1.05–6.70). Similar associations that did not reach significance were found when exploring prescribed and illicit buprenorphine use. There was no difference in opioid use when comparing participants with prior buprenorphine experience to those who were buprenorphine-naive (AOR=1.33, 95% CI=0.38–4.65). Although not significant, qualitatively different results were found when exploring opioid use by type of prior buprenorphine use (prescribed buprenorphine vs. buprenorphine-naïve, AOR=2.20, 95% CI=0.58–8.26; illicit buprenorphine vs. buprenorphine-naïve, AOR=0.47, 95% CI=0.07–3.46).

Conclusions

Prior buprenorphine experience was common and associated with better retention. Understanding how prior buprenorphine experience affects treatment outcomes has important clinical and public health implications.

Keywords: buprenorphine, opioid, opioid dependence, office-based treatment

In the United States, opioid abuse and dependence continue to dramatically increase (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2008a, 2008b; Cicero et al., 2005; Sung et al., 2005). Buprenorphine, a partial opioid agonist, can address this problem, as buprenorphine is used to treat opioid dependence in a variety of settings. Studies report that up to 27% of patients seeking buprenorphine treatment have had prior experience with buprenorphine (Alford et al., 2011; Whitley et al., 2010; Cicero et al., 2007). The number of patients receiving buprenorphine prescriptions from physicians has been increasing, with 2009 estimates of over 22,000 physicians having undergone training to provide buprenorphine treatment and over 1 million patients having received buprenorphine treatment (Kresina et al., 2008; Fiellin, 2007; Arfken et al., 2010). Additionally, emerging evidence indicates that individuals are increasingly using illicit buprenorphine obtained from friends or bought on the streets (Bazazi et al., 2011; Cicero et al., 2007; Schuman-Olivier et al., 2010; Daniulaityte et al., 2012). In fact, studies report that among individuals seeking or receiving buprenorphine treatment, 10–49% have used illicit buprenorphine (Alford et al., 2011; Whitley et al., 2010; Cicero et al., 2007; Schuman-Olivier et al., 2010).

Among individuals seeking buprenorphine treatment, those who have prior use of prescribed buprenorphine may differ than those who have prior use of illicit buprenorphine. Despite this, because both types of buprenorphine use (prescribed and illicit use) provide individuals with an experience taking buprenorphine, a partial opioid agonist that has unique pharmacologic properties and challenges, examining how any prior experience with buprenorphine may be associated with treatment outcomes is warranted.

National treatment guidelines caution that patients with prior buprenorphine treatment episodes may not be appropriate candidates for subsequent office-based buprenorphine treatment (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2007). Presumably, this recommendation is based on concerns that patients who failed prior treatment attempts may have severe opioid dependence that may be refractory to treatment. If so, they may require more intensive treatment and monitoring than can be provided in office-based settings, and drug treatment settings with buprenorphine or methadone maintenance treatment programs may be more suitable. However, national treatment guidelines do not give guidance regarding treatment of patients with prior use of illicit buprenorphine. Recent studies have demonstrated substantial illicit buprenorphine use, particularly among marginalized populations, and suggest that individuals with illicit buprenorphine use tend to use it as “self-treatment” “self-management” or “self-medicating” rather than for obtaining euphoria or getting “high” (Bazazi et al., 2011; Cicero et al., 2007; Schuman-Olivier et al., 2010; Monte et al., 2009; Whitley et al., 2010; Gwin et al., 2009; Daniulaityte et al., 2012). These studies suggest that these individuals engage in non-traditional forms of treatment rather than accessing formal treatment programs.

Despite the national treatment guidelines and recent reports about illicit buprenorphine use, little evidence is available to guide decisions about optimal treatment strategies for patients with prior buprenorphine experience. We are aware of only a few studies that examined prior buprenorphine experience in patients seeking office-based buprenorphine treatment. One study found more “successful treatment” (12-month treatment retention or buprenorphine taper after treatment adherence and absence of illicit drug use for ≥ 6 months) in patients with illicit buprenorphine use than without illicit use (68 vs. 49%; Alford et al., 2011). In our previous work examining a retrospective cohort, we found fewer complicated inductions (inductions with precipitated or protracted withdrawal) in patients with illicit or prescribed buprenorphine use versus buprenorphine-naïve patients (0% vs. 33%; Whitley et al., 2010). However, in a different analysis, we found no difference in 30-day treatment retention in patients with prior buprenorphine experience compared with buprenorphine-naïve patients (81% vs. 77%; Sohler et al., 2009). Given the paucity of studies examining prior buprenorphine experience, the inconsistent findings of these studies, and the increased likelihood of prior buprenorphine experience among persons seeking buprenorphine treatment, in a prospective cohort, we examined whether prior buprenorphine experience was associated with treatment outcomes in opioid-dependent individuals who initiated office-based buprenorphine treatment. Based on our clinical experience and the studies mentioned above, we hypothesized that compared to buprenorphine-naïve individuals, those with prior buprenorphine experience would have better treatment outcomes, including higher treatment retention and less opioid use. We also explored how different types of prior buprenorphine experience (use of prescribed buprenorphine and use of illicit buprenorphine) were associated with treatment outcomes.

Methods

We conducted an analysis of a longitudinal cohort study of opioid-dependent individuals who initiated buprenorphine treatment at an urban community health center. Original study aims were to identify factors that predict positive treatment outcomes in participants receiving buprenorphine treatment that was integrated into primary care. Participants were followed for six months, and data collection included interviews and medical record extraction.

Setting

The study was conducted in a Bronx community health center from November 2004 to December 2009, immediately after a buprenorphine treatment program was established. (For details about the buprenorphine treatment program, see Cunningham et al., 2008). Briefly, six general internists work closely with a clinical pharmacologist to provide buprenorphine treatment in the context of general primary care medicine. Buprenorphine treatment typically consists of monthly visits with a provider in which buprenorphine/naloxone medication is prescribed, counseling occurs, and urine toxicology tests are conducted. If there is evidence of ongoing drug use despite buprenorphine treatment, physicians typically intensify treatment through more frequent visits and/or referrals for psychosocial support (e.g., off-site self-help groups, outpatient substance abuse treatment programs, or psychiatric care). No substance abuse counselors or support groups are available at the health center, but, two social workers are available to all health center patients, including those who receive buprenorphine treatment.

Participants

Original study eligibility criteria included: 1) newly initiating buprenorphine treatment at the health center (defined as transferred from a hospital, rehabilitation, or detoxification facility within 7 days of starting buprenorphine medication or no prescribed buprenorphine in the previous 30 days), 2) HIV infection, and 3) English fluency. After securing additional funding, the last two criteria were revised in January 2007 to include participants who were HIV-positive or HIV-negative, and fluent in English or Spanish. To receive buprenorphine treatment at the health center, participants had to be at least 18 years old, dependent on opioids (per Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition [DSM-IV] criteria, 1994), and insured by a health plan accepted at the health center or willing to pay for treatment on a sliding scale fee. Consistent with national guidelines (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment., 2007), participants were excluded from receiving buprenorphine treatment if they were: 1) hypersensitive to buprenorphine or naloxone, 2) pregnant, 3) alcohol dependent (per DSM-IV criteria (1994)), 4) benzodiazepine dependent (per DSM-IV criteria (1994), 5) with transaminase levels greater than five times normal, 6) diagnosed with severe, untreated psychiatric illness, and 7) taking more than 60 mg of methadone daily in the past month.

The study was registered in clinicaltrials.gov and was approved by the medical center’s institutional review board. All participants provided written informed consent.

Data Collection

Participants were interviewed by a research assistant at baseline (prior to initiating buprenorphine treatment at the health center), and 1, 3, and 6 months. Interviews lasted 45–60 minutes and occurred in a private room at the health center. Interviews were conducted using audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) technology in which questions were displayed on a computer while an audio recording of the question was played. Participants entered responses directly on the computer, which may result in more accurate reporting of sensitive behavior than other survey methods (Turner et al., 1998). Participants received $15 travel reimbursement for each interview.

At the 6-month follow-up period, visit and prescription data were extracted from electronic medical records.

Dependent variables

Our two primary outcomes were buprenorphine treatment retention and opioid use. Treatment retention was examined 1, 3, and 6 months after participants initiated buprenorphine treatment. Participants were categorized as retained in treatment if they had either a medical visit or active buprenorphine prescription between day 30–60 for 1-month retention, between day 90–120 for 3-month retention, and between day 180–210 for 6-month retention. To be retained in treatment at 3 months, participants also had to be retained at 1 month, and to be retained in treatment at 6 months, participants had to be retained at both 1 and 3 months. All retention data were from medical records.

Opioid use was defined as self-reported use of any heroin, methadone, or opioid analgesic in the 30-day period prior to each interview during the 6-month follow-up period (at 1, 3, and 6 months).

Independent variable

Our main independent variable was prior buprenorphine experience, defined as having ever taken buprenorphine prior to initiating buprenorphine treatment at our health center. Participants who reported having ever been prescribed buprenorphine or having ever taken non-prescribed or illicit buprenorphine were considered as having ever taken buprenorphine. In exploratory analyses, we also examined type of buprenorphine use as an independent variable. Those who reported having ever been prescribed buprenorphine were categorized as having prior use of prescribed buprenorphine, regardless of whether they reported prior use of illicit buprenorphine. Those who reported never having been prescribed buprenorphine and reported prior use of illicit buprenorphine were categorized as having prior use of illicit buprenorphine. Questions about prior buprenorphine experience were from a buprenorphine/HIV multi-site study (Weiss et al., 2011).

Other variables

Sociodemographic covariates collected via interviews included: age (continuous); gender (male, female); race/ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic other); language (English fluency, no English fluency); education (less than a high school diploma or GED, at least a high school diploma or GED); employment (employed, unemployed); housing status (stably housed defined as reporting living in an apartment or home, unstably housed defined as living in any other situation); marital status (married, not married); and history of incarceration for three or more days (yes, no). Clinical covariates collected via interviews included: drug use in the 30 days prior to baseline (heroin; methadone; opioid analgesics; cocaine; sedatives, hypnotics, or tranquillizers); ever injected drugs (yes, no); methadone treatment within the previous 3 months (yes, no); and depressive symptoms (score of ≥16 from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies, Depression [CESD; (Radloff 1977)]; score of <16 on the CESD). Demographic questions were from a buprenorphine/HIV multi-site study (Weiss et al., 2011), and substance use questions were from the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (McLellan et al., 1992). Buprenorphine/naloxone dose 1 month after initiation of buprenorphine treatment was extracted from medical records.

Data Analyses

Buprenorphine treatment retention and previous buprenorphine experience

We first conducted simple chi square tests of those retained in treatment at 1, 3, and 6 months comparing participants with prior buprenorphine experience with buprenorphine-naïve participants. We then used logistic regression models to test whether prior buprenorphine experience was associated with 6-month treatment retention while adjusting for potential confounders. To determine which covariates to include in the full model, we first examined variables that differed (p<0.20) between participants with prior buprenorphine experience and buprenorphine-naïve participants. As indicated in Table 1, these variables included age, language, housing status, baseline methadone use, baseline cocaine use, and recent methadone treatment. We then tested whether these variables were associated with a change of greater than 10% in the beta coefficient for prior buprenorphine experience. Age and language, which were each associated with a change of greater than 10% in the beta coefficient, were included in the final multivariate model examining the association between prior buprenorphine experience and buprenorphine treatment retention.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of participants with and without prior buprenorphine experience.

| Sociodemographic characteristics | Total N=87 n (%) |

Buprenorphine- naïve N=37 of 87 n (%) |

Prior buprenorphine experience N=50 of 87 n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean years ± SD) | 43.5 ± 9.0 | 45.2 ± 9.1 | 42.3 ± 8.8* |

| Male | 64 (73.6) | 27 (73.0) | 37 (74.0) |

| Race/ethnicity1 | |||

| Hispanic | 60 (73.2) | 26 (72.3) | 34 (72.3) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 19 (23.1) | 7 (20.0) | 12 (25.5) |

| Non-Hispanic other | 3 (3.7) | 2 (5.7) | 1 (2.1) |

| English fluency | 53 (60.9) | 27 (73.0) | 26 (52.0)** |

| High school diploma or GED | 57 (65.5) | 22 (59.5) | 35 (70.0) |

| Employed | 27 (31.0) | 13 (35.1) | 14 (28.0) |

| Stably housed | 34 (39.1) | 19 (51.4) | 15 (30.0)** |

| Married | 26 (29.9) | 13 (35.1) | 13 (26.0) |

| Ever incarcerated | 60 (69.0) | 24 (64.9) | 36 (72.0) |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Baseline drug use2 | |||

| Heroin | 59 (67.8) | 24 (64.9) | 35 (70.0) |

| Methadone | 46 (52.9) | 25 (67.6) | 21 (42.0)** |

| Opioid analgesics | 23 (26.4) | 10 (27.0) | 13 (26.0) |

| Sedatives | 13 (14.9) | 7 (18.9) | 6 (12.0) |

| Cocaine | 34 (39.1) | 11 (29.7) | 23 (46.0)* |

| Ever injected drugs | 44 (50.6) | 18 (48.7) | 26 (52.0) |

| Recent methadone treatment | 21 (25.9) | 15 (48.4) | 6 (12.0)** |

| CESD score ≥16 | 55 (63.2) | 22 (59.5) | 33 (66.0) |

| Median 1-month buprenorphine/naloxone dose (IQR)1 | 16/4 mg (12/3–24/6 mg) | 16/4 mg (8/2–24/6 mg) | 16/4 mg (12/3–24/6 mg) |

Note: Column percentages are presented.

CESD=Center for Epidemiology Studies, Depression (Radloff, 1977); IQR=interquartile range

Missing data: race/ethnicity is missing for 5 participants; dose is missing for 3 participants.

Baseline drug use is defined as self-reported use of the drug within 30 days prior to baseline interview.

p<0.20

p<0.05

Opioid use and previous buprenorphine experience

We used mixed effects non-linear models to test whether prior buprenorphine experience use was associated with opioid use over the 6 month follow-up period (measured at 1, 3, and 6 months) while adjusting for time and baseline opioid use. Using the same process mentioned above, to determine which covariates to include the full multivariate model adjusting for potential confounders, we examined variables that differed (p<0.20) between participants with prior buprenorphine experience and buprenorphine-naïve participants. We tested whether these variables were associated with a change of greater than 10% in the beta coefficient for prior buprenorphine experience. Language, housing status, baseline methadone use, baseline cocaine use, and recent methadone treatment were each associated with a change of greater than 10% in the beta coefficient. Because baseline methadone use and recent methadone treatment were collinear, we included only one of these measures (baseline methadone use) in the model. Thus, along with time and baseline opioid use, language, housing status, baseline methadone use, and baseline cocaine use were included in the final multivariate model examining the association between prior buprenorphine experience and opioid use.

Exploratory analyses examining type of buprenorphine experience

In subsequent analyses, we explored how type of prior buprenorphine experience was associated with treatment retention and opioid use. Using the same analytic methods mentioned above, we examined separately whether prior use of prescribed buprenorphine, and then prior use of illicit buprenorphine, were associated with treatment retention and opioid use when compared with buprenorphine-naïve participants.

All analyses were conducted using STATA v11.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Participant characteristics

Of the 114 screened and eligible participants, 108 (94.7%) enrolled in the study. Of these, 3 withdrew from the study, 14 never initiated buprenorphine treatment, and 4 had no follow-up interviews. Thus, 87 participants are included in this analysis. From these 87 participants, 75 (86.2%) interviews were conducted at 1 month, 79 (90.8%) at 3 months, and 73 (83.9%) at 6 months.

Participants’ mean age was 43.5 years at baseline, and most were men (73.6%), Hispanic (73.2%), unemployed (69.0%), with histories of incarceration (69.0%) and with histories of injection drug use (50.6%) (see Table 1). Regarding baseline opioid use (use within the 30-day period prior to the baseline interview), 67.8% reported using heroin, 52.9% methadone, and 26.4% opioid analgesics. Recent methadone treatment (within 3 months of initiating buprenorphine treatment) was reported by 25.9% of participants. Median buprenorphine/naloxone dose 1 month after initiating buprenorphine treatment was 16/4 mg (interquartile range, 12/3 – 24/6 mg).

At baseline, 50 (57.4%) participants reported prior buprenorphine experience. Of these, 20 (40.0%) reported having used prescribed buprenorphine, while 30 (60.0%) reported having used illicit buprenorphine. Participants with prior buprenorphine experience versus participants who were buprenorphine-naïve were less likely to be fluent in English (52.0% vs. 73.0%, p<0.05), be stably housed (30.0% vs. 51.4%, p<0.05), report baseline methadone use (42.0% vs. 67.6%, p<0.05), and report recent methadone treatment (12.0% vs. 48.4%, p<0.05).

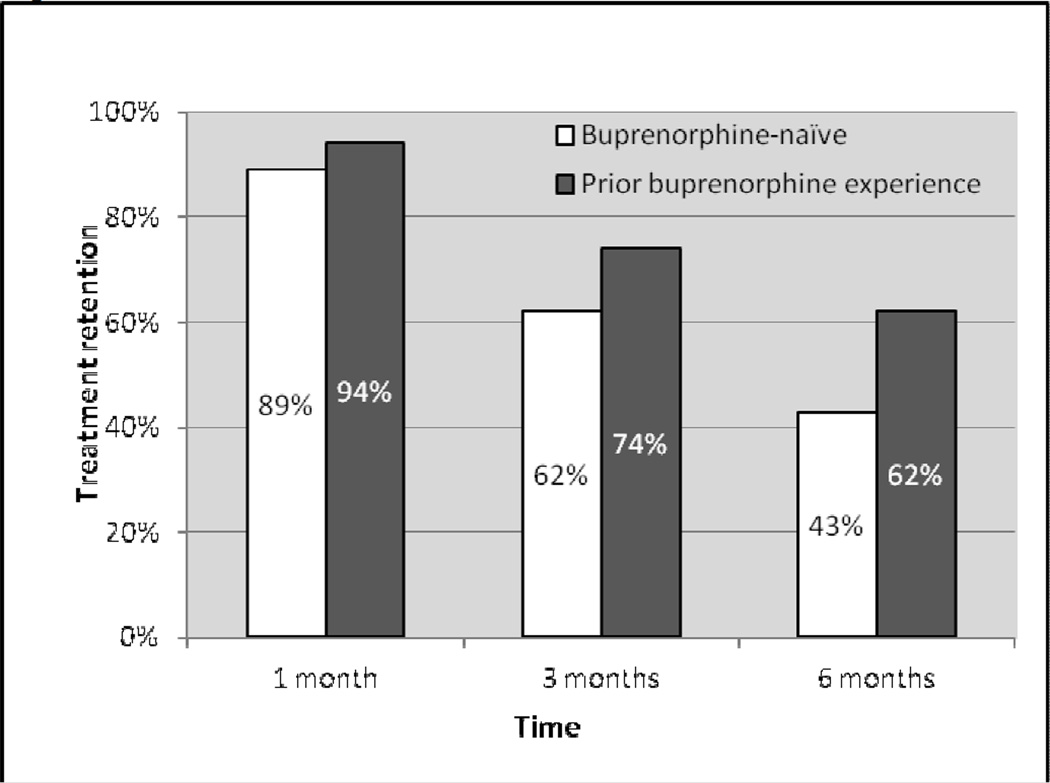

Buprenorphine treatment retention

Among all participants, treatment retention at 1, 3, and 6 months was 92.0%, 69.0% and 54.0%, respectively. Figure 1 displays treatment retention at 1, 3, and 6 months by prior buprenorphine experience. In multivariate analysis, compared with those who were buprenorphine-naïve, participants with prior buprenorphine experience were more likely to be retained in treatment at 6 months (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=2.65, 95% CI=1.05–6.70, p<0.05) (see Table 2). When exploring 6-month treatment retention for each type of prior use of buprenorphine versus being buprenorphine-naïve, we found similar associations that did not reach statistical significance (retention in participants with prior use of prescribed buprenorphine vs. buprenorphine-naïve participants, AOR=2.53, 95% CI=0.81–7.88, p=0.11; retention in participants with prior use of illicit buprenorphine vs. buprenorphine-naïve participants, AOR=2.92, 95% CI=0.95–8.91, p=0.06).

Figure 1.

Treatment retention in participants with and without prior buprenorphine experience

Table 2.

Adjusted odds of treatment retention and self-reported opioid use over 6 months by prior buprenorphine experience.

| AOR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment retention1 | ||

| Prior use of any buprenorphine | 2.65 | 1.05 – 6.70 |

| Prior use of prescribed buprenorphine | 2.53 | 0.81 – 7.88 |

| Prior use of illicit buprenorphine only | 2.92 | 0.95 – 8.91 |

| Self-reported opioid use2 | ||

| Prior use of any buprenorphine | 1.33 | 0.38 – 4.65 |

| Prior use of prescribed buprenorphine | 2.20 | 0.58 – 8.26 |

| Prior use of illicit buprenorphine only | 0.47 | 0.07 – 3.46 |

Note: For all analyses, the comparison group is buprenorphine-naïve participants

Covariates included in models examining retention include age and language

Covariates included in models examining opioid use include time, baseline opioid use, language, housing status, baseline methadone use, and baseline cocaine use

Opioid use

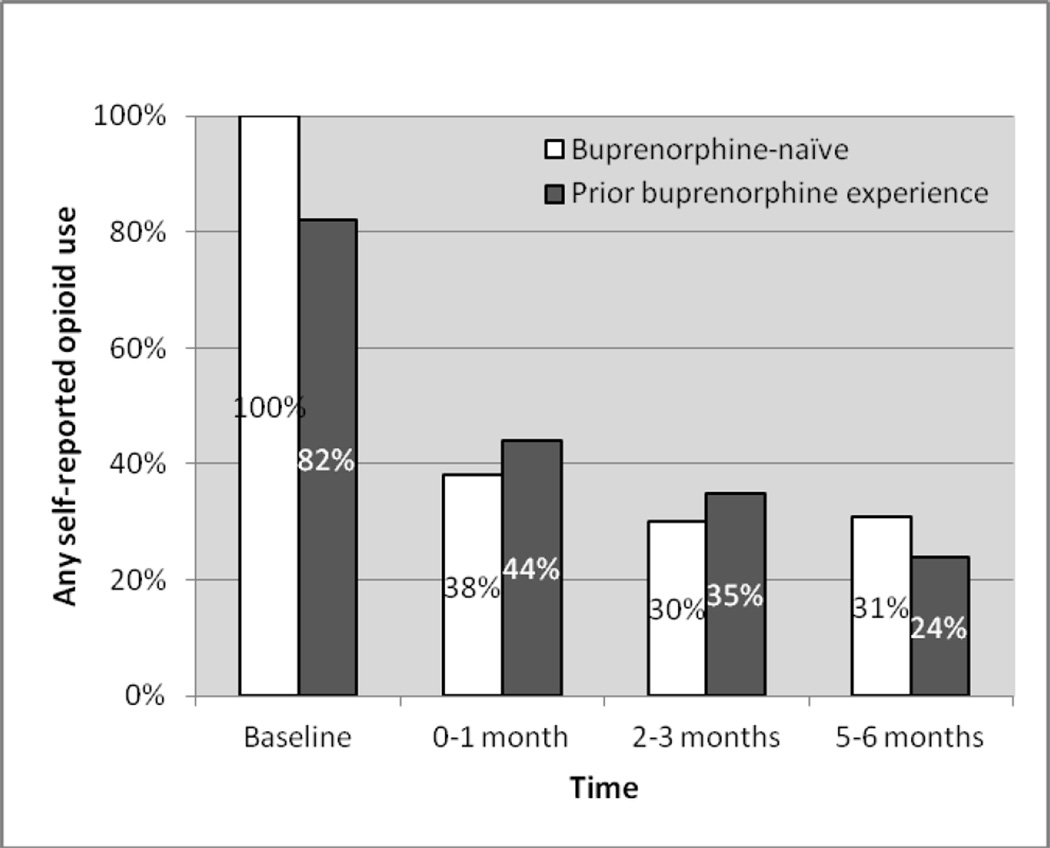

Among all participants, opioid use decreased over time from 89.7% at baseline to 41.9% at 1 month, 32.9% at 3 months, and 27.4 % at 6 months. Figure 2 displays opioid use at 1, 3, and 6 months by prior buprenorphine experience. In multivariate analysis, there was no significant difference in opioid use between participants with prior buprenorphine experience versus those who were buprenorphine-naïve (AOR=1.33, 95% CI=0.38–4.65, p=0.65) (see Table 2). When we explored opioid use in participants with prior use of prescribed buprenorphine and those with prior use of illicit buprenorphine separately, we found qualitatively different results, but the associations did not reach statistical significance (opioid use in participants with prior use of prescribed buprenorphine vs. buprenorphine-naïve participants, AOR=2.20, 95% CI=0.58–8.26, p=0.24; opioid use in participants with prior use of illicit buprenorphine vs. buprenorphine-naïve participants, AOR=0.47, 95% CI=0.07–3.46, p=0.46).

Figure 2.

Any self-reported opioid use in participants with and without prior buprenorphine experience

Discussion

In this study of opioid-dependent individuals initiating buprenorphine treatment at an urban community health center, over half of the participants entered treatment with a history of prior buprenorphine experience. The majority of those with prior buprenorphine experience reported using illicit buprenorphine. We found that participants with prior buprenorphine experience were more likely to be retained in treatment than buprenorphine-naïve participants. However, we found no evidence of differences in opioid use between these groups. While three other studies examined treatment retention among participants with and without prior buprenorphine experience, to our knowledge, this study is the first to also compare opioid use across these groups.

We are aware of three other studies that examined treatment outcomes among patients with prior buprenorphine use (Alford et al., 2011; Whitley et al., 2010; Sohler et al., 2009). In one study by Alford and colleagues of nearly 400 patients who received buprenorphine treatment in an office-based setting, patients with illicit buprenorphine use at the time they sought treatment had greater odds of achieving success (treatment retention or taper off of buprenorphine) when compared to those without illicit buprenorphine use (OR=3.04; Alford et al., 2011). However, those who had a history or current use of prescribed buprenorphine at the time they sought treatment had no better outcomes. Our findings are somewhat similar to that found by Alford and colleagues. We found that those with any prior buprenorphine experience (prescribed or illicit buprenorphine) were significantly more likely to be retained in treatment, while Alford found that only those with illicit buprenorphine use, and not prescribed buprenorphine use, had significantly better outcomes.

Additional studies that examined treatment outcomes among patients with prior buprenorphine use were from our previous retrospective cohort study in which medical records were reviewed from the first patients treated in our office-based treatment program. Our earlier studies differ from our current study, as our current study is a prospective cohort study following different patients over a 6-month period with data from interviews and medical records. In one of our previous studies that focused on factors associated with complicated inductions, we found that prior prescribed buprenorphine use and prior illicit buprenorphine use were both associated with better induction outcomes (Whitley et al., 2010). In that study, complicated inductions (inductions with precipitated or protracted withdrawal) occurred among 19% of patients without prior prescribed buprenorphine use and 21% of patients without prior illicit buprenorphine, while no complicated inductions occurred among patients with prior prescribed or illicit buprenorphine use. However, in our other previous study that focused on home-based versus office-based inductions, we found no difference in 30-day retention between patients with any prior buprenorphine experience versus buprenorphine-naïve patients (81% vs. 77%; Sohler et al., 2009). Our current prospective study extends our previous findings, as our current study examined opioid use in addition to treatment retention, examined longer-term (6-month) outcomes, and found better retention in those with prior buprenorphine experience.

Individuals with prior buprenorphine experience may have better treatment outcomes for a variety of reasons. For example, those with prior prescribed buprenorphine use may have had positive experiences with buprenorphine treatment, despite dropping out of treatment at some point. Their positive experiences may have been related to the physiological effects of buprenorphine and/or the treatment setting with minimal regulations. Similarly, those with prior illicit buprenorphine use may also have had positive experiences with the physiological effects of buprenorphine, and may have become motivated to use buprenorphine in a treatment setting. It is also possible that those with prior buprenorphine experience may have been more highly motivated to avoid methadone treatment than buprenorphine-naïve patients. As prior buprenorphine experience is likely to become more common among those seeking buprenorphine treatment, further exploration of how prior use of prescribed or illicit buprenorphine affects treatment outcomes is warranted.

Although our main analysis examined the association between any prior buprenorphine experience and treatment outcomes, when we explored prior illicit buprenorphine use and prior prescribed buprenorphine use separately, our data indicated that outcomes did not differ significantly by different types of prior buprenorphine use. However, we noted qualitatively different point estimates of opioid use for participants with prior use of illicit buprenorphine than those with prior use of prescribed buprenorphine, suggesting that those with prior use of illicit buprenorphine may have a lower risk of opioid use after initiating buprenorphine treatment (when compared to buprenorphine-naïve participants) while those with prior use of prescribed buprenorphine may have a higher risk of opioid use (when compared to buprenorphine-naïve participants). Although our findings did not reach statistical significance, they are consistent with prior studies that have described use of illicit buprenorphine to reduce other opioid use (Bazazi et al., 2011; Cicero et al., 2007; Schuman-Olivier et al., 2010; Monte et al., 2009; Whitley et al., 2010; Gwin et al., 2009). Thus, individuals who use illicit buprenorphine prior to seeking buprenorphine treatment may be highly motivated to reduce their opioid use. Clearly these analyses are exploratory and deserve additional exploration with a larger study sample.

Our study has limitations. One of our outcomes, opioid use, relied on self report which may not accurately portray ongoing substance use and is subject to recall bias. Although urine toxicology tests were available in medical records, they were conducted for clinical care rather than research. Because they were not routinely collected in a standardized manner, differential collection among those retained in treatment versus those not retained in treatment created bias. Therefore, results of urine toxicology tests were not used in our outcome measure. However, our other main outcome, treatment retention, relied on objective data from medical records. Our study was limited to one clinical site; thus, our findings may not be generalizable to other populations. Although our sample of 87 participants limited our power to detect significant differences between participants with prior buprenorphine experience and buprenorphine-naïve participants, we observed a significant difference in treatment retention between groups, but no significant difference in opioid use between groups. In our exploratory analyses, we were limited in our categorization of participants. Because of the structure of our interview, we were able to categorize participants into either having prior use of prescribed buprenorphine or prior use of illicit buprenorphine. We were unable to categorize participants as having prior use of both types of buprenorphine, which may have obscured findings in our exploratory analyses. Because study participants received buprenorphine treatment in a real-world setting outside of a drug treatment setting, they often received prescriptions for a month’s worth of medications, and had monthly visits. Frequently, patients in this setting reported “stretching” buprenorphine medication to last longer than indicated by prescription data, and would miss visits only to keep another visit shortly thereafter. Therefore, determination of treatment drop-out (and conversely treatment retention) may not have been as straight forward or clearly delineated as other buprenorphine studies. To balance clinical and methodological importance, we used a definition of treatment retention at 1, 3, and 6 months that took into account active prescriptions and recent visits.

Conclusions

In conclusion, among opioid-dependent individuals seeking office-based buprenorphine treatment in the Bronx, prior buprenorphine experience was common. Our study found better treatment retention in those with prior buprenorphine experience (prescribed or illicit buprenorphine use) than those who were buprenorphine-naïve. As buprenorphine treatment continues to expand, and illicit buprenorphine use appears to be increasing, prior experience with buprenorphine is likely to be more common among individuals presenting for buprenorphine treatment. Understanding how prior buprenorphine experience affects treatment outcomes has important clinical and public health implications.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration, HIV/AIDS Bureau, Special Projects of National Significance, grant 6H97HA00247; the Center for AIDS Research at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Montefiore Medical Center (NIH AI-51519); NIH R25DA023021; and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program. We thank Mia Brisbane and Johanna Rivera for their help conducting this research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders - Fourth Edition. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Alford DP, LaBelle CT, Kretsch N, Bergeron A, Winter M, Botticelli M, et al. Collaborative care of opioid-addicted patients in primary care using buprenorphine: five-year experience. Arch. Intern. Med. 2011;171:425–431. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arfken CL, Johanson CE, di Menza S, Schuster CR. Expanding treatment capacity for opioid dependence with office-based treatment with buprenorphine: National surveys of physicians. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2010;39:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazazi AR, Yokell M, Fu JJ, Rich JD, Zaller ND. Illicit use of buprenorphine/naloxone among injecting and noninjecting opioid users. J. Addict. Med. 2011;5:175–180. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3182034e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Clinical Guidelines for the Use of Buprenorphine in the Treatment of Opioid Addiction. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 40. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2007. DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 04-3939. 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicero TJ, Inciardi JA, Munoz A. Trends in abuse of Oxycontin and other opioid analgesics in the United States: 2002–2004. J. Pain. 2005;6:662–672. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicero TJ, Surratt HL, Inciardi J. Use and misuse of buprenorphine in the management of opioid addiction. J. Opioid. Manag. 2007;3:302–308. doi: 10.5055/jom.2007.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham C, Giovanniello A, Sacajiu G, Whitley S, Mund P, Beil R, et al. Buprenorphine treatment in an urban community health center: what to expect. Fam. Med. 2008;40:500–506. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniulaityte R, Falck R, Carlson RG. Illicit use of buprenorphine in a community sample of young adult non-medical users of pharmaceutical opioids. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;122:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiellin DA. The first three years of buprenorphine in the United States: Experience to date and future directions. J. Addict. Med. 2007;1:62–67. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3180473c11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwin MS, Kelly SM, Brown BS, Schacht RH, Peterson JA, Ruhf A, et al. Uses of diverted methadone and buprenorphine by opioid-addicted individuals in Baltimore, Maryland. Am. J. Addict. 2009;18:346–355. doi: 10.3109/10550490903077820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresina TF, Litwin AH, Marion I, Lubran R, Clark HW. United States government oversight and regulation of medication assisted treatment for the treatment of opioid dependence. Journal of Drug Policy Analysis. 2009;2 [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, et al. The Fifth Edition of the Addiction Severity Index. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 1992;9:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monte AA, Mandell T, Wilford BB, Tennyson J, Boyer EW. Diversion of buprenorphine/naloxone coformulated tablets in a region with high prescribing prevalence. J. Addict. Dis. 2009;28:226–231. doi: 10.1080/10550880903014767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied. Psychological. Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Schuman-Olivier Z, Albanese M, Nelson SE, Roland L, Puopolo F, Klinker L, et al. Self-treatment: illicit buprenorphine use by opioid-dependent treatment seekers. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2010;39:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohler NL, Li X, Kunins HV, Sacajiu G, Giovanniello A, Whitley S, et al. Home- versus office-based buprenorphine inductions for opioid-dependent patients. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2009;38:153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Rockville, MD: NSDUH; 2008a. Series H-34 (DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 08-4343). [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Office of Applied Studies. Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2006: National Estimates of Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits. Rockville, MD: DAWN; 2008b. Series D-30 (DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 08-4339). [Google Scholar]

- Sung HE, Richter L, Vaughan R, Johnson PB, Thom B. Nonmedical use of prescription opioids among teenagers in the United States: trends and correlates. J. Adolesc. Health. 2005;37:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, violence: increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280:867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss L, Egan JE, Botsko M, Netherland J, Fiellin DA, Finkelstein R. The BHIVES collaborative: organization and evaluation of a multisite demonstration of integrated buprenorphine/naloxone and HIV treatment. J. Acquir. Immune. Defic. Syndr. 2011;56(Suppl 1):S7–S13. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182097426. S7-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitley SD, Sohler NL, Kunins HV, Giovanniello A, Li X, Sacajiu G, et al. Factors associated with complicated buprenorphine inductions. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2010;39:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]