Abstract

Paranemic crossover (PX) DNA is a four-stranded coaxial DNA structure containing a central dyad axis that relates two flanking parallel double helices. The strands are held together exclusively by Watson-Crick base pairing. The key feature of the structure is that the two adjacent parallel DNA double helices form crossovers at every point possible. Hence, reciprocal crossover points flank the central dyad axis at every major or minor groove separation. This motif has been modeled and characterized in an oligonucleotide system; a minor groove separation of 5 nucleotide pairs and major groove separations of 6, 7, or 8 nucleotide pairs produce stable PX DNA molecules; a major groove separation of 9 nucleotide pairs is possible at low concentrations. Every strand undergoes a crossover every helical repeat (11, 12, 13 or 14 nucleotides), but the structural period of each strand corresponds to two helical repeats (22, 24, 26 or 28 nucleotides). Non-denaturing gel electrophoresis shows that the molecules are stable, forming well-behaved complexes. PX DNA can be produced from closed dumbbells, demonstrating that the molecule is paranemic. Ferguson analysis indicates that the molecules are similar in shape to DNA double crossover molecules. Circular dichroism spectra are consistent with B-form DNA. Thermal transition profiles suggest a premelting transition in each of the molecules. Hydroxyl radical autofootprinting analysis confirms that there is a crossover point at each of the positions expected in the secondary structure. These molecules are generalized Holliday junctions that have applications in nanotechnology.

INTRODUCTION

Watson-Crick1 base pairing is the well-known interaction that stabilizes the coaxial double helical structure of DNA. The complementary relationships between adenine (A) and thymine (T), and between guanine (G) and cytosine (C) provide the means by which the two strands of DNA recognize each other. In addition to double stranded molecules, triple stranded coaxial species can be formed if one of the molecules contains a polypurine tract2 and the system is properly configured.3,4 Tetra-stranded coaxial species can be formed that include homopolymer motifs, such as G4 arrangements (e.g., ref. 5), the unusual cytosine motif in I-DNA,6 or poly-dA and poly-dT.7 In addition, multistranded species can be formed that are based on the Holliday junction;8 these molecules contain a unique branch point flanked by three or more double helices,9 but the strands are not coaxial in these molecules. Nevertheless, two Holliday junctions joined at two adjacent arms produce double crossover (DX) molecules. The joins may occur between strands of the same polarity, producing 'parallel' molecules, or between strands of opposite polarity, yielding 'antiparallel' molecules. DX molecules flank a central axis; they have been proposed as intermediates in recombination,10,11 and have been demonstrated to be involved in meiosis.12 DX molecules have been modeled in oligonucleotide systems,13 and they have found applications in the analysis of Holliday junction physical chemistry and enzymology (e.g., refs. 14–18), in nanotechnology,19–23 and in DNA-based computing.24 McGavin25 and Wilson26 have proposed paranemic motifs involving a central dyad axis and recognition via hydrogen bonding in the grooves of the helices. Such species are appealing models of homologous recognition, useful to explain recombination data (e.g., ref. 27), but their formation has not been demonstrated convincingly in the laboratory, except in short molecules stabilized by other interactions.28

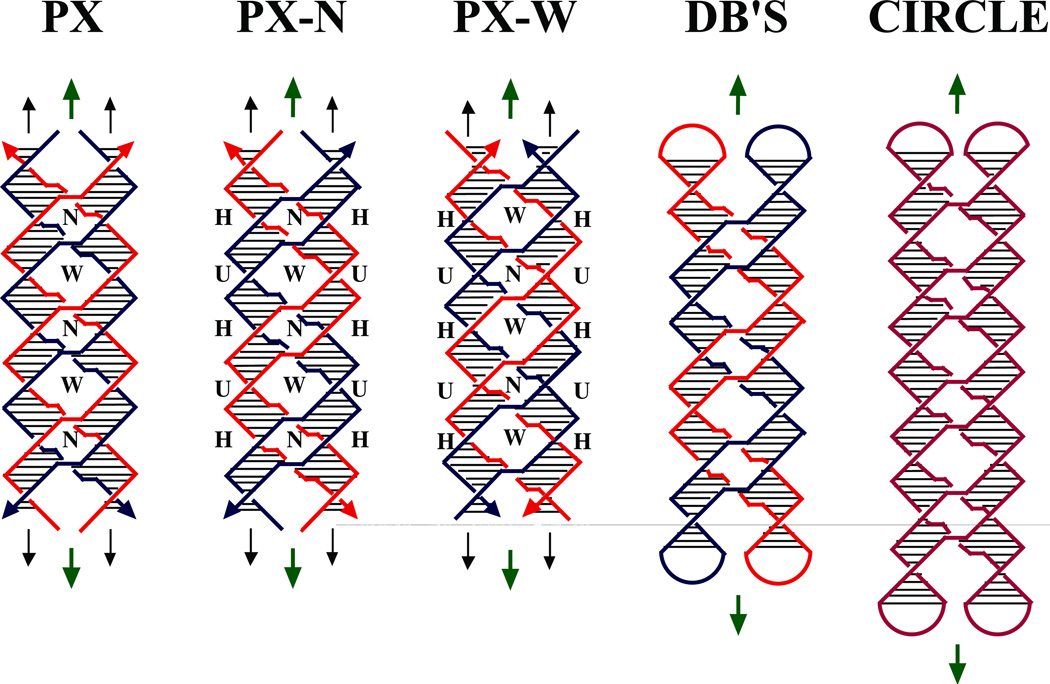

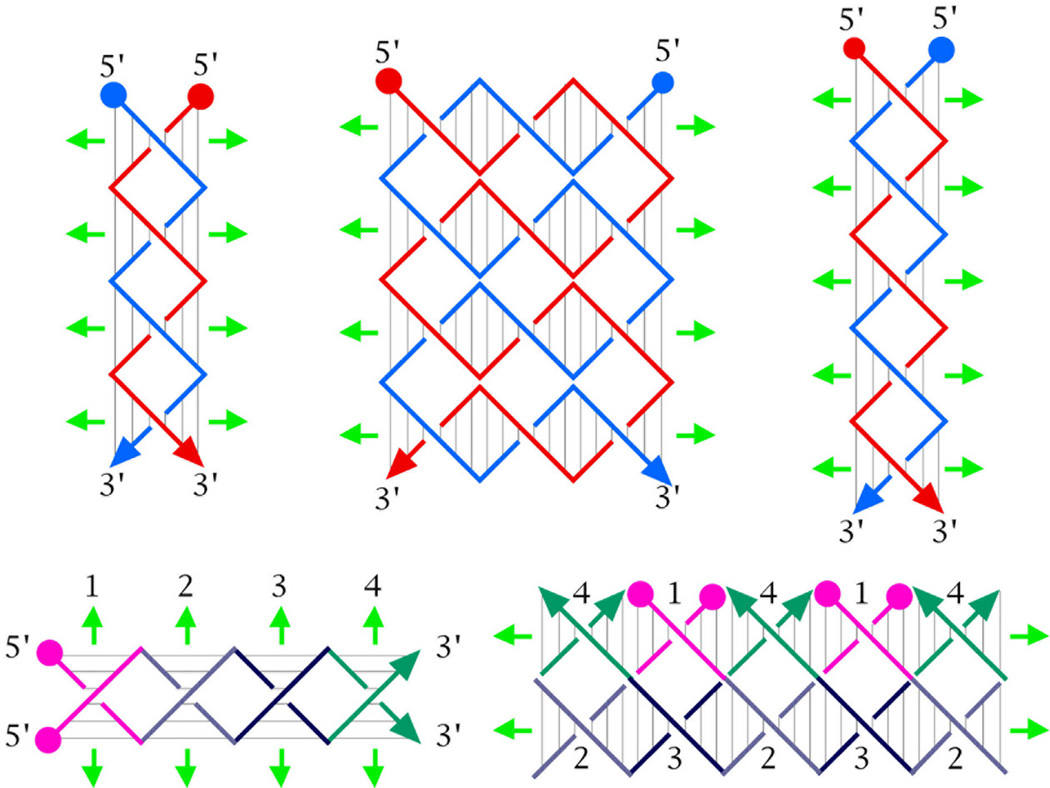

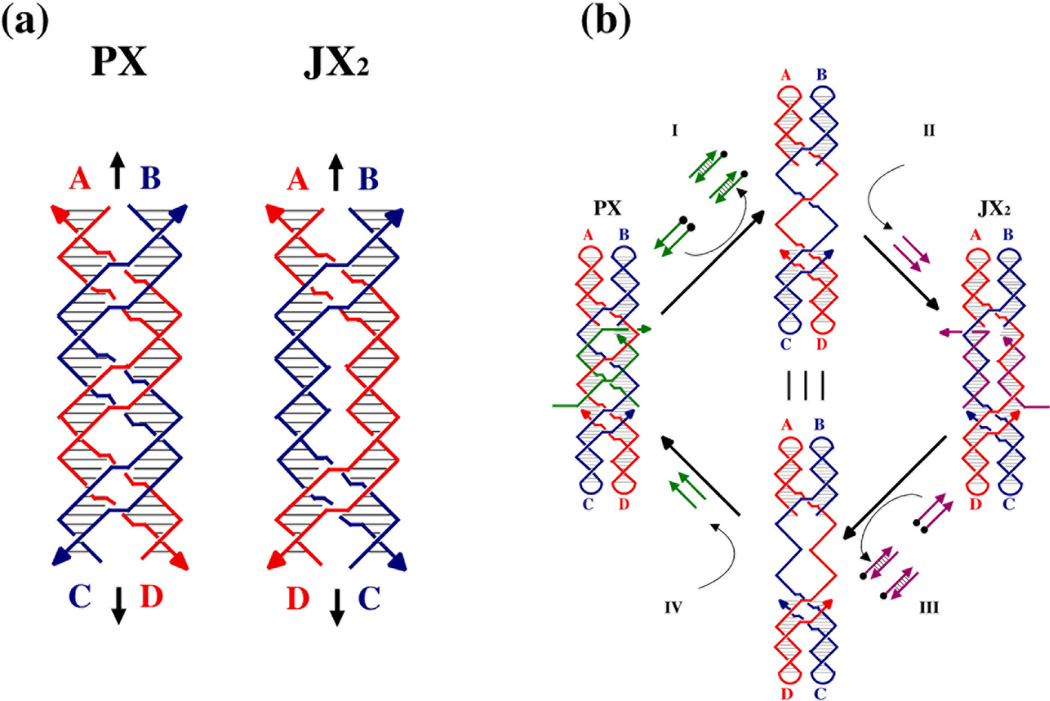

Here, we report the construction and preliminary physical characterization of a coaxial 4-stranded DNA motif in which every nucleotide is paired by Watson-Crick interactions. This structure is shown schematically in several variants in Figure 1. In contrast to previously proposed four-stranded parallel molecules, no non-Watson-Crick hydrogen bonding interactions are necessary to stabilize this structure. Similar to the McGavin and Wilson structures, the molecule contains a central dyad axis (green arrows in Figure 1), relating the backbones of one pair of strands to the other; it also contains two subsidiary DNA helix axes (pairs of black arrows in Figure 1), whose repeat is similar to the normal twist in DNA double helices. We term this structure paranemic crossover (PX) DNA, because the backbones of the two component double strands are not linked to each other, and can pair with each other indefinitely, without the need for strand scission. Nevertheless, the two double strands are wrapped about each other in a manner similar to the wrapping of the two strands of a double helix; this type of association is known as 'plectonemic'. The PX structure can be derived by exchanging strands of the same polarity at every possible site between two adjacent double helices that have been placed side by side. 29 Thus, wherever two strands approach the central region of the molecule, they pass over to the other helix, and there are no backbone juxtapositions. Consequently, each strand is involved in a crossover at the start and the end of each of its Watson-Crick helical turns. The period of the PX structure is about twice that of conventional DNA.

Figure 1. Schematic Drawings of Paranemic Crossover DNA, and its Closed Analogs.

The three molecules on the left are drawn containing pairs of strands drawn in red and blue; strands drawn with the same color are related to each other by the dyad axis. The helix of each strand is approximated by a zig-zag structure. Arrowheads on the strands denote their 3' ends. The base pairs are indicated by very thin black lines. Both the PX and PX-N molecules contain four strands, arranged in two double helical domains related by a central dyad axis. The PX and PX-N molecules are identical, but two different pairs of dyad symmetries are shown between strands flanking the dyad: PX illustrates symmetry between strands of the same polarity, whereas PX-N shows symmetry between strands flanking a minor groove (a third symmetry, between strands flanking the major groove, is not shown). The view is perpendicular to the plane containing both helix axes. The dyad axes are indicated by the short green arrows above and below each molecule. The PX and PX-N molecules have alternating major (wide) and minor (narrow) groove tangles, indicated by 'W' and 'N', respectively. The formation of PX from two intact double helices would require homology in the unit tangles labeled 'H', but not those labeled 'U'. The two molecules on the far right are closed PX molecules. The left molecule of the two contains two paired dumbbells (DB's) that are unlinked topologically. The molecule on the right is a half-turn longer in each helical domain; the resulting structure is an intricately self-paired single-stranded circle drawn in purple.

PX DNA is a generalization of the Holliday intermediate, because it repeats the crossover feature over a number of contiguous positions, rather than just a single site. The molecule labeled PX in Figure 1 is colored to show dyad symmetry between strands of the same polarity; the one labeled PX-N is identical to it, but it is colored differently; its symmetry is drawn to suggest two double strands of different colors wrapped around each other with their minor grooves on the outside of the structure. The molecule labeled PX-W is colored analogously to PX-N, except that the double strands wrapped around each other are phased differently, so their major grooves are on the outside of the structure. A system based on the PX structure has been used in structural DNA nanotechnology as the basis of a robust sequence-dependent nanomechanical device.30

If one examines the part of the PX molecule flanking the central dyad axis, crossovers occur with alternating frequencies, depending on whether a major groove or a minor groove flanks the axis; these different spacings are indicated as W (for wide, or major groove), or N (for narrow, or minor groove). In this projection (normal to the plane containing both helix axes), the strands of the PX-N molecule cross each other within the double helices, at sites between the inter-helical crossover points. These intra-helix strand crossings, visible as red or blue 'X's flanked by U's in the PX-N and PX-W molecules (Figure 1), are unit tangles31 of DNA; a unit tangle is the basic individual strand-crossing feature (also called a node) of a catenane or a knot. There are also red-blue or blue-red intra-helix unit tangles within the PX-N and PX-W molecules; all the intra-helix unit tangles in the molecule labeled PX are red-blue or blue-red. We refer to these partial turns within each helix as either a major groove tangle or a minor groove tangle, depending on which of its grooves flanks the central dyad axis. The major (wide) groove tangles are labeled 'W' in Figure 1, and the minor (narrow) groove tangles are labeled 'N'. The ubiquity of the inter-helix crossovers makes it reasonable to phase the rotational component of each strand's helix from crossover point to crossover point; in going 5'→3' between crossover points, a strand participates in two unit tangles, first a major groove tangle, and then a minor groove tangle. If the ends of the PX-N molecule in Figure 1 were closed by hairpin loops, two unlinked dumbbells would be produced, as seen in the molecule labeled DB's (Figure 1); the separability of the dumb-bells highlights the paranemic nature of the PX molecule. Dumb-bell like molecules have been used as the cohesive elements for closed geometrical systems in structural DNA nanotechnology applications.32 Nevertheless, closing the ends of molecules one unit tangle longer or shorter in each helical domain would result in the formation of an intricate, but ultimately trivial knot (a circle), illustrated on the far right of Figure 1.

We have used sequence symmetry minimization33,34 to model PX molecules in an oligonucleotide system. We have determined empirically that the best spacing for the minor groove is five nucleotide pairs, but the major groove can contain six, seven, eight or, (at low concentration) nine nucleotide pairs. The bulk of our experiments apply to three molecules with these features, containing seven half-turns of DNA. We have characterized the PX motif by gel electrophoresis, circular dichroism spectroscopy, thermal transition profiles and hydroxyl radical autofootprinting analysis. All of these forms of characterization are consistent with the schematic drawings shown in Figure 1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sequence Design

The sequences have been designed by applying the principles of sequence symmetry minimization,33,34 insofar as it is possible to do so within the constraints of this system. The crossover points on each strand are pre-determined in a PX molecule with an asymmetric sequence: Crossover isomerization16 would produce mispairing, because major groove tangles would become minor groove tangles and vice versa. The sequences of the molecules used are given in the supplementary information..

Synthesis and Purification of DNA

All DNA molecules in this study have been synthesized on an Applied Biosystems 380B automatic DNA synthesizer, removed from the support, and deprotected, using routine phosphoramidite procedures.35 DNA strands have been purified from denaturing gels.

Formation of Hydrogen-bonded Complexes

Complexes are formed by mixing a stoichiometric quantity of each strand, as estimated by OD260, in a solution containing 40 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0, 20 mM acetic acid, 2 mM EDTA and 12.5 mM magnesium acetate (TAEMg). This mixture is then heated to 90 °C for 5 minutes and cooled to the desired temperature by the following protocol: 20 minutes at 65 °C, 20 minutes at 45 °C, 30 minutes at 37 °C, 30 minutes at room temperature, and (if desired), 2 hrs at 4 °C. Stoichiometry is determined by titrating pairs of strands designed to hydrogen bond together, and visualizing them by native gel electrophoresis; absence of monomer indicates the endpoint.

Thermal Denaturation Profiles

DNA strands are dissolved to 1 µM concentration in 2 ml of a solution containing 40 mM sodium cacodylate a 10 mM magnesium acetate, pH 7.5, and annealed as described above. The samples are transferred to quartz cuvettes, and the cacodylate buffer is used as a blank. Thermal denaturation is monitored at 260 nm on a Spectronic Genesys 5 Spectrophotometer, using a Neslab RTE-111 circulating bath; temperature was incremented at 0.1 °C/min.

Hydroxyl Radical Analysis

Individual strands of PX complexes are radioactively labeled, and are additionally gel purified from a 10–20% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. Each of the labeled strands [approximately 1 pmol in 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.5) containing 10 mM MgCl2] is annealed to a tenfold excess of the unlabeled complementary strands, or it is annealed to a tenfold excess of a mixture of the other strands forming the complex, or it is left untreated as a control, or it is treated with sequencing reagents for a sizing ladder. The samples are annealed by heating to 90 °C for 3 min. and then cooled slowly to 4 °C. Hydroxyl radical cleavage of the double-strand and PX-complex samples for all strands takes place at 4 °C for 2 min.,36 with modifications noted by Churchill, et al.37 The reaction is stopped by addition of thiourea. The sample is dried, dissolved in a formamide/dye mixture, and loaded directly onto a 10–20% polyacrylamide/8.3M urea sequencing gel. Autoradiograms are analyzed on a BioRad GS-525 Molecular Imager.

Non-Denaturing Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis

Gels contain 8–20% acrylamide (19:1, acrylamide:bisacrylamide). DNA is suspended in 10–25 µL of a solution of TAEMg buffer; the quantities loaded vary as noted. The solution is boiled and allowed to cool slowly in staged decrements to 4 °C. Samples are then brought to a final volume of 20 µL and a concentration of 1 µM, with a solution containing TAEMg, 50% glycerol and 0.02% each of Bromophenol Blue and Xylene Cyanol FF tracking dyes. Gels are run on a Hoefer SE-600 gel electrophoresis unit at 11 Volts/cm at 4 °C, and stained with Stainsall dye. Absolute mobilities (cm/hr) of native gels run at 4 °C are measured for Ferguson analysis; logarithms are taken to base 10.

Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy

Each of four strands is mixed stoichiometrically to produce a 1 µM solution in a buffer containing in 40 mM Sodium Cacodylate, and 10 mM magnesium acetate at pH 7.5. The strands are annealed as described above. CD spectra are measured using an AVIV (Lakewood, NJ) model 62A DS spectropolarimeter at room temperature.

RESULTS

Formation of the Complexes

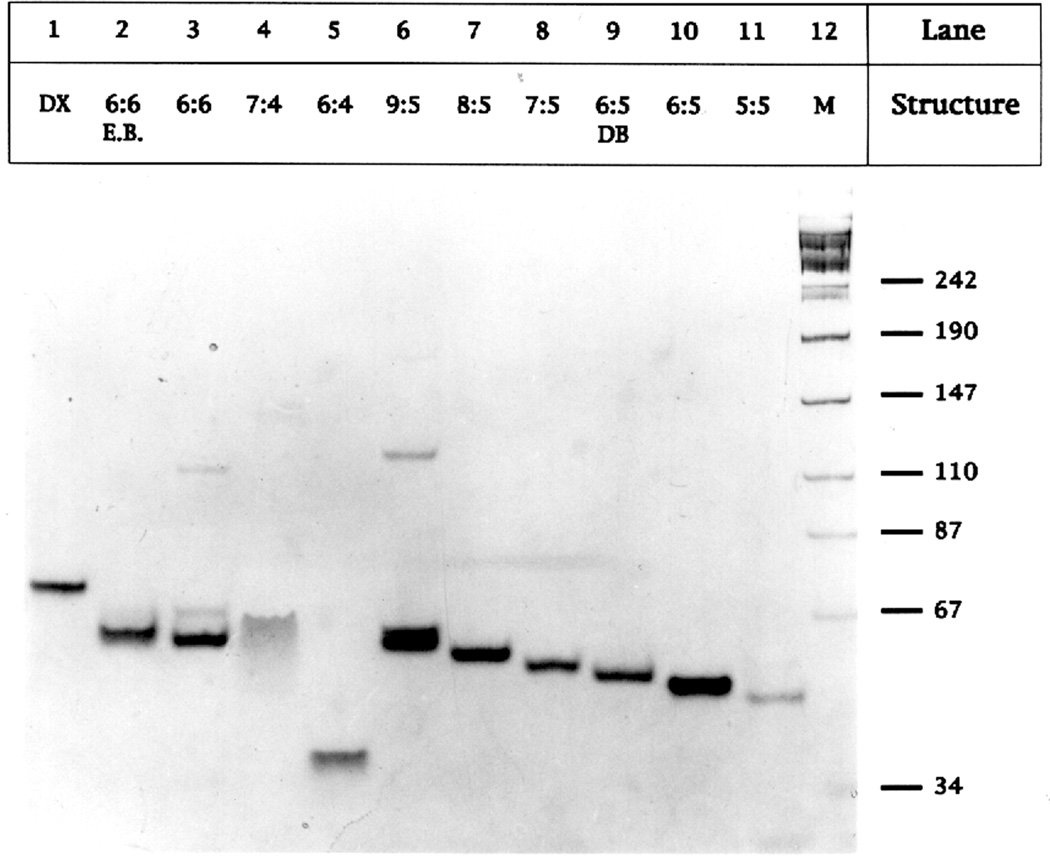

We designate complexes as W:N, where W represents the number of nucleotide pairs in the major (wide) groove and N represents the number of nucleotide pairs in the minor (narrow) groove. Figure 2 illustrates the successful formation of stable 6:5, 7:5 and 8:5 PX complexes containing five half-turns of DNA, and compares them with a series of related molecules of similar length; this is the only series in which five half-turns are used instead of seven. We interpret a single band with approximately the expected mobility as evidence for a stable molecule. Bands migrating faster than this target are interpreted to be breakdown products; well-formed bands migrating more slowly are taken to be multimers of the full complex (containing 8, 12 or more strands), whose presence indicates some form of instability in the 4-strand complex. Such multimers were seen in the formation of parallel double crossover (DX) molecules;13 these are similar to PX molecules, except that in DX molecules there are only two points where the two helical domains are connected by crossover structures. Lane 1 contains a stable DAO-type DX molecule13 containing 38 nucleotide pairs per helical domain. Lanes 2 and 3 contain a molecule designed with 6 nucleotide pairs in each groove, 6:6. Neither complex produces a clean single band, but the one in lane 2 contains ethidium, thereby decreasing its twist; the expected molecular band is split, but the molecular dimer prominent in Lane 3 is missing, suggesting that some part of the 6:6 molecule is overtwisted. Lane 4 contains a 7:4 complex, showing a prominent smear below the molecular band, denoting instability. Lane 5 contains a 6:4 combination, which appears not to form a four-strand complex at all. Lane 6 contains a 9:5 complex, which exhibits a dimer. Lanes 7, 8 and 10 contain stable 8:5, 7:5 and 6:5 complexes, characterized by a single band of approximately the expected molecular weight. Lane 9 contains a 6:5 PX molecule formed from dumbbells, such as those in Figure1, although shorter; the successful formation of a PX molecule from dumbbell components demonstrates that the topology shown in Figure 1 is correct, and that plectonemic braiding of individual strands is not required for association. Lane 11 contains another ill-behaved complex, the 5:5 molecule, whose molecular band is split like the one in lane 2. The 1:1:1:1 stoichiometry of the complexes has been established by titration experiments38 (data not shown).

Figure 2. Non-Denaturing Gel Analysis of PX Molecules.

The 8% non-denaturing gel shown contains variations of the basic PX motif, and illustrates that only 6:5, 7:5 and 8:5 form well behaved molecules. These experiments have been performed with PX molecules and their congeners containing about 5 unit tangles in each helical domain. The contents of each lane is indicated above it. 'E.B.' indicates that the molecule has been treated with ethidium bromide; DB is a dumbbell motif, similar to, but shorter than the two-dumbbell PX molecule in Figure 1, in which both molecules have been sealed covalently. In all cases, smears or multimers indicate that PX molecules are not forming stable molecules.

Hydroxyl Radical Autofootprinting Analysis

We have used hydroxyl radical autofootprinting previously to characterize unusual DNA molecules, including branched junctions,9,37 tethered junctions,39 antijunctions and mesojunctions,40 DX molecules13,14 and triple crossover (TX) molecules.41 These experiments are performed by labeling a component strand of the complex and exposing it to hydroxyl radicals. The key feature noted at crossover sites in these analyses is decreased susceptibility to attack when comparing the pattern of the strand as part of the complex, relative to the pattern of the strand derived from linear duplex DNA. Decreased susceptibility is interpreted to suggest that access of the hydroxyl radical may be limited by steric factors at the sites where it is detected. Likewise, similarity to the duplex pattern at points of potential flexure is assumed to indicate that the strand has adopted a conventional helical structure in the complex, whether or not it is required by the secondary structure. In previous studies of junctions, DX molecules, and mesojunctions, protection has been seen particularly at the crossover sites, but also at non-crossover sites where strands from two adjacent parallel or antiparallel domains appear to occlude each other's surfaces, preventing access by hydroxyl radicals.13,37,40 Thus, crossover sites can be located reliably by hydroxyl radical autofootprinting analysis, but it is not possible to distinguish them unambiguously from juxtapositions of backbone strands.

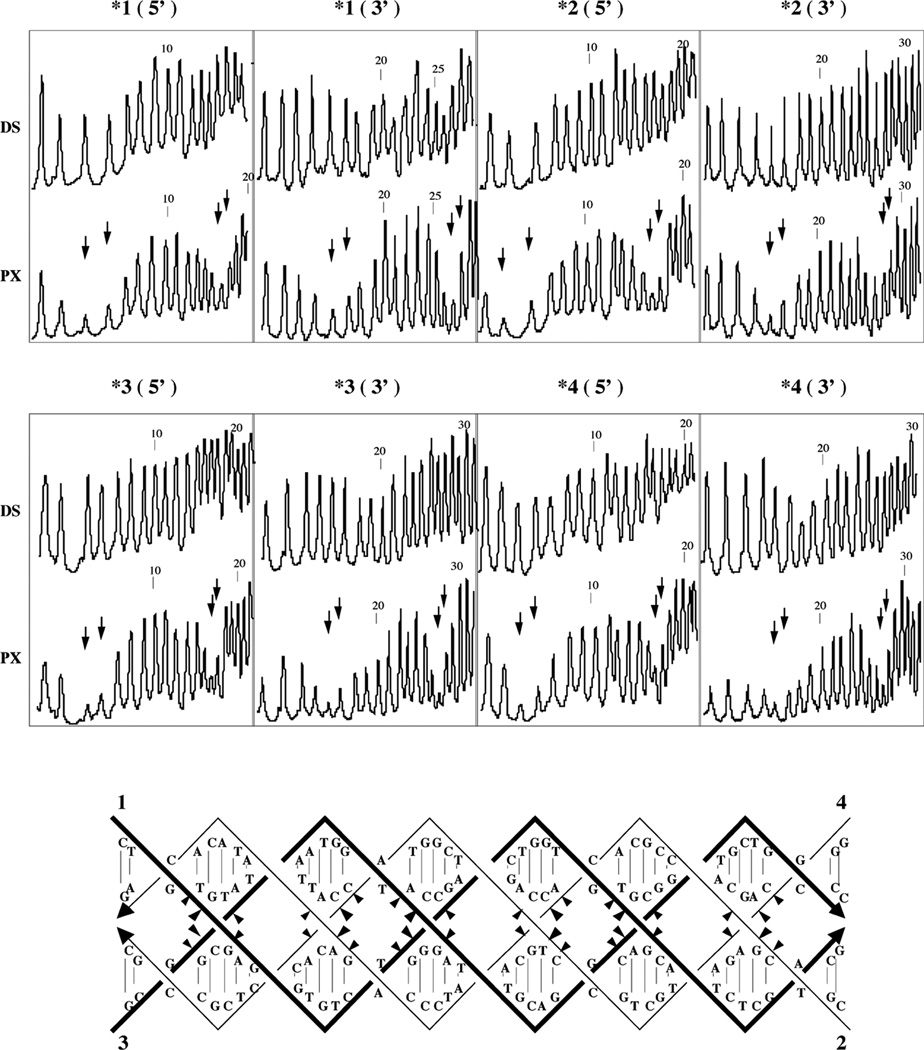

Hydroxyl radical attack patterns are displayed for a 6:5 molecule in Figure 3; results for 7:5 and 8:5 molecules are similar (not shown). The 5' and 3' portions of each strand are shown in two separate panels, and the expected crossover positions are indicated for each strand by two vertical arrows that indicate the two nucleotides that flank the site. In each panel, the pattern for each strand in the complex (PX) is compared with the pattern for the same strand when it is paired with its conventional Watson-Crick complement in a double helix (DS). Dramatic protection is seen in the vicinity of the crossover point, relative to the duplex control. The protection seen here differs slightly from that seen for branched junctions, where the two nucleotides flanking the crossover point appear to be equally protected. Here, the protection centers primarily on the 5' nucleotide flanking the crossover. This feature was observed in some instances in the hydroxyl radical autofootprinting of parallel DX molecules.13 The hydroxyl radical autofootprinting analysis of the PX molecules is in agreement with the expected pattern, with protection visible on each strand in the vicinity of the nucleotides designed to flank crossover points.

Figure 3. Hydroxyl Radical Autofootprinting of a 6:5 PX Molecule.

The analysis for each strand is shown twice, once for its 5' end, and once for its 3' end, as indicated above the appropriate panel. Susceptibility to hydroxyl radical attack is compared for each strand when incorporated into the PX molecule (PX) and when paired with its traditional Watson-Crick complement (DS). Nucleotide numbers are indicated above every tenth nucleotide. The two nucleotides flanking expected crossover positions are indicated by two arrows. Note the correlation between the arrows and protection in all cases. The data are summarized on a molecular drawing below the scans. Sites of protection are indicated by triangles pointing towards the protected nucleotide; the extent of protection is indicated qualitatively by the sizes of the triangles.

Ferguson Analysis

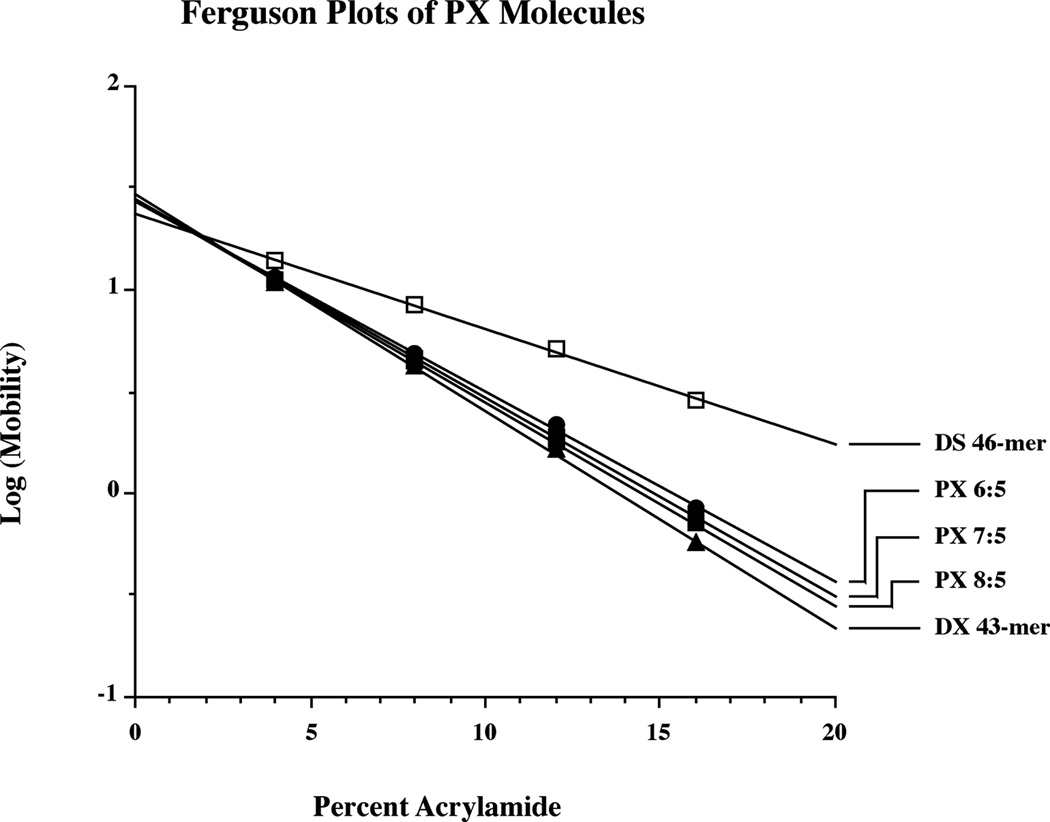

The Ferguson plot is used to analyze electrophoretic mobility as a function of gel concentration; the slope of this plot (log(mobility) vs. polyacrylamide concentration) yields information about the friction constant of the molecule. Figure 4 illustrates Ferguson plots for each of the PX molecules reported here, for a DX control, and for a double stranded control. Each of the PX molecules contains seven unit tangles, so the 6:5 molecule contains 38 nucleotide pairs per domain, the 7:5 molecule contains 43 nucleotide pairs per domain and the 8:5 molecule contains 46 nucleotide pairs per domain. The slopes of the three PX molecules are very similar to each other, and they are also similar to control molecules in which the central unit tangle is flanked by juxtapositions, rather than crossovers (data not shown). As expected, the slopes increase slightly with the size of the molecule. The slopes are all comparable to that of a DX molecule of similar size, suggesting similarity in their molecular shapes. The duplex molecule plotted along with these species exhibits clearly different frictional properties.

Figure 4. Ferguson Analysis of PX Molecules.

The plots of the three PX molecules are compared to a DX molecule of comparable length, which is similar, and to a double helical molecule, which is quite distinct. The slopes and intercepts for the molecules are 6:5 (−0.0934, 1.44), 7:5 (−0.0973, 1.44), 8:5 (−0.0997, 1.45), DX (−0.1065, 1.47), DS (-.0561, 1.37). Versions of the PX molecules containing juxtapositions flanking their central major groove tangles are similar to the PX molecules: 6:5 (−0.0936, 1.44), 7:5 (−0.0995, 1.45), and 8:5 (−0.1023, 1.46).

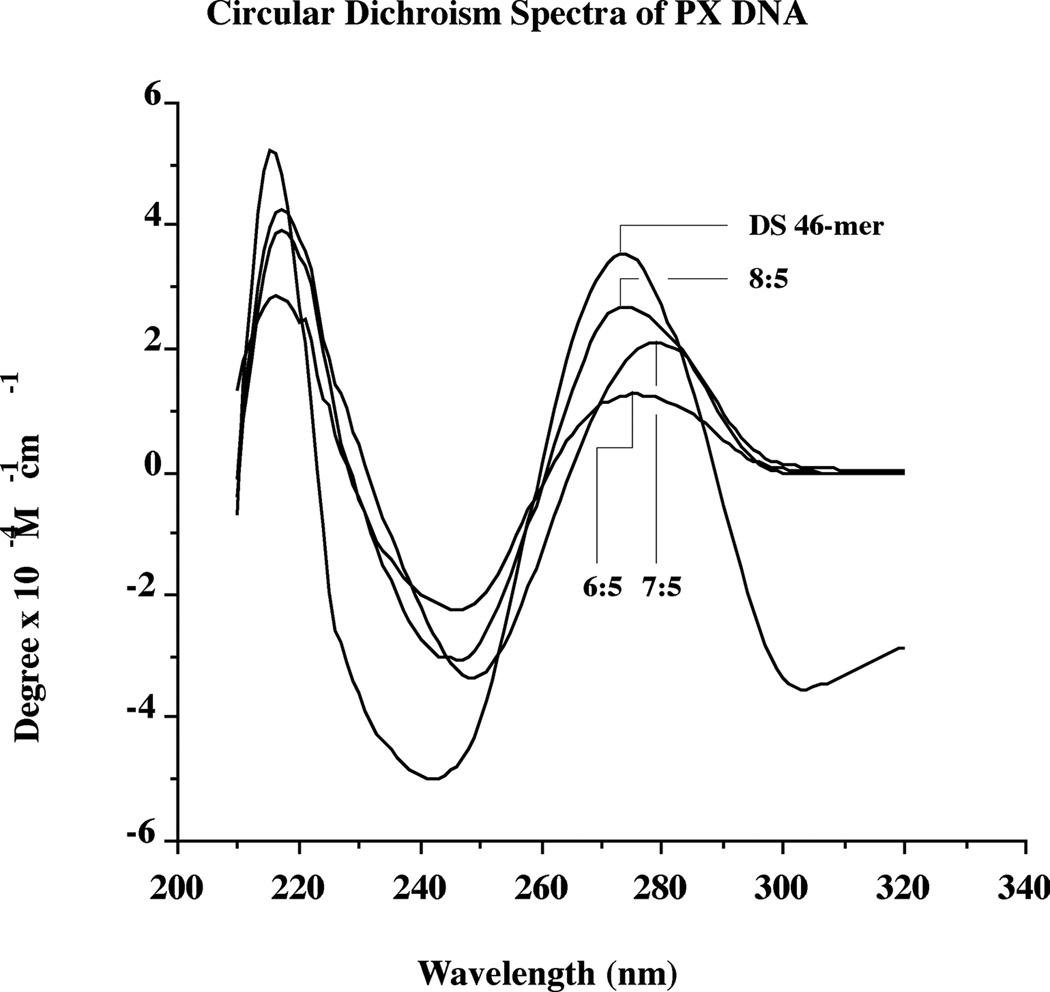

Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy

The fact that the PX molecule can accommodate three different sizes of the major groove suggests that its secondary structure might be somewhat unusual. We have examined this issue qualitatively by measuring circular dichroism spectra for the three PX molecules, and by comparing them to a standard double helical molecule. The spectra (Figure 5) suggest that none of the molecules have unusual secondary structures, and that they most resemble B-DNA. The long-wavelength maxima are observed at 276 nm (6:5), 279 nm (7:5) and 274 nm (8:5), similar to the duplex standard's maximum at 274 nm. Minima are noted at 246 nm (6:5), 249 nm (7:5) and 247 nm (8:5), again similar to 242 nm, seen for the duplex standard. Thus, the 6:5 and 8:5 PX molecules have extrema most similar to those of B-DNA, whereas the spectra of the 7:5 PX molecules are slightly red-shifted. The key point here, however, is that the stresses placed on the molecules by enforcing the PX structure on them do not appear to have produced a secondary structure significantly different from conventional B-DNA.

Figure 5. Circular Dichroism Spectra of PX Molecules Compared with Duplex DNA.

The extrema of the double helical 46-mer are similar to those seen for B-DNA. All of the PX spectra are similar to that of the double helical molecule, although the 7:5 molecule is shifted slightly to longer wavelengths.

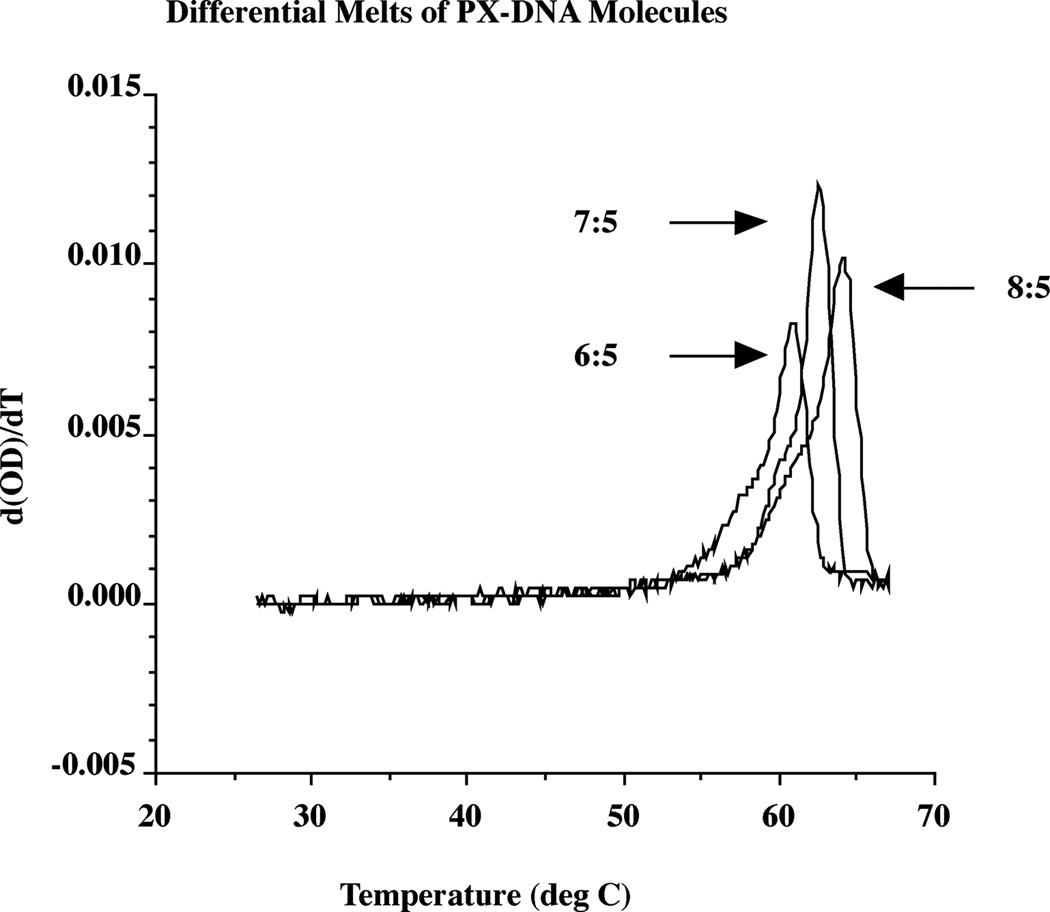

Thermal transition profiles

Figure 6 shows the thermal transition profiles of the three complexes as monitored by optical density (260 nm). A differential plot of the melting is shown. The melting temperatures derived from the differential plot are 60.8 °C (6:5), 62.5 °C (7:5) and 64.2 °C (8:5). These relative melting temperatures are in agreement with reasonable expectations, given the relative sizes of the molecules (76, 86 and 92 nucleotide pairs). It is clear that the melting behavior is cooperative, but the differential plot reveals pre-melting transitions for each molecule. It is likely that the melting points represented by the nominal melting temperatures represent the final unstacking of the nucleotides, but that the pre-melting transitions are due to disruption of the PX structure itself.

Figure 6. Thermal Transition Behavior of PX DNA.

The drawing shows the differential melting behavior, in a plot smoothed by a 13 point interpolation. It has not been possible to obtain reversible melting curves; hysteresis is always seen, even if the reverse transition is extended to a period of a week. A pre-melting transition is evident for all species.

DISCUSSION

Complex Formation and Stability of Isomers

The data presented suggest that PX DNA is a stable nucleic acid motif containing parallel helix axes that flank a central dyad axis. Strands with sequences lacking homology that are designed to associate into PX DNA do so as readily as strands designed to form immobile branched junctions9,38 or antiparallel DX molecules.13 Indeed, PX DNA with major groove/minor groove ratios of 6:5, 7:5 or 8:5 is better behaved than parallel DX molecules with only two crossovers. This finding may be due to the fact that there are no juxtapositions of negatively-charged backbones in PX molecules, unlike in parallel DX molecules. Other combinations of major and minor groove sizes do not appear to be stable. The formation of the complexes from a dumbbell analog of 6:5 supports the notion that the complex is paranemic.

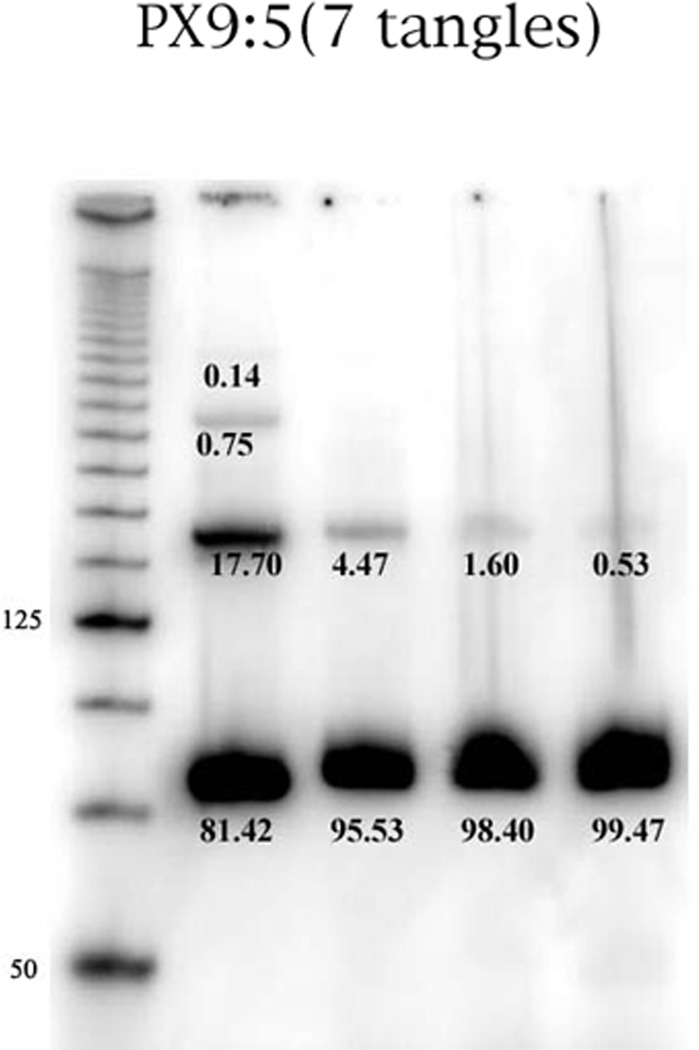

Molecular dynamics calculations on the stability of PX molecules (Maiti, P.K., Heo, J., Pascal, T., Vaidehi, N. & Goddard, W. A. III, in preparation) have suggested that 9:5 molecules ought to be stable. Examination of the 9:5 lane in Figure 2 shows a very large ratio of the PX monomer to the dimer and trimer bands when a 1 µM concentration is used. We have studied the effects of concentration on the multimerization of the 9:5 PX molecule, as shown in Figure 7. It is clear that the 4-strand monomer becomes an even greater component of the species present as the concentration is decreased. Hydroxyl radical autofootprinting of both 5- and 7-unit tangle 9:5 PX molecules reveals the expected protection at the inner crossover points, but not at those closest to the ends of the helical domains (data not shown).

Figure 7. Concentration Dependence of the 9:5 PX Motif.

This is an autoradiogram of a PX 9:5 complex containing 7 half-turns of DNA. The leftmost lane contains a 25 base-pair marker. From left to right, the other lanes contain the complex at concentrations of 1000 nM, 500 nM, 250 nM and 125 nM. The percentage of material in each band is indicated. It is clear that the multimers of the 9:5 PX virtually can be eliminated at low concentrations.

Structural Features

The preliminary characterization performed here supports the qualitative structure of the PX molecules drawn in Figure 1. Hydroxyl radical analysis indicates that each strand exhibits dramatic protection in the vicinity of the expected crossover point, in line with the suggested model. The protection noted is somewhat more intense than that seen previously for juxtapositions in DX molecules,13 suggesting that it derives from crossovers. Ferguson analysis confirms that the overall shape of the molecule is similar to that of a DX molecule of comparable size, again in agreement with the model presented in Figure 1. Circular dichroism spectroscopy indicates that the secondary structure of the DNA is at least qualitatively of the B-form. The spectra are similar to standard B-DNA spectra that have been measured, and differ markedly from, say, A-form spectra, even though the A-structure is traditionally associated with nucleic acids containing 11–12 nucleotide pairs per helical turn. The backbone structure appears to be independent of the sequence of the molecule, so long as the Watson-Crick pairing requirements are met.

The most stable molecules we have described contain 11 (6:5), 12 (7:5) or 13 (8:5) nucleotide pairs per Watson-Crick turn, compared with an average number of about 10.5 in unstressed DNA molecules in solution.42, 43 A DNA molecule constrained to have an excess number nucleotide pairs per Watson-Crick turn is negatively supercoiled, relative to its relaxed state. DNA molecules may respond to distortions of this sort either by changing the effective twist within dinucleotide units or by distorting the helix axis, which is called writhing (e.g., ref. 44). Molecular dynamics (MD) calculations (Maiti, P.K., Heo, J., Pascal, T., Vaidehi, N. & Goddard, W. A. III, in preparation) suggest that the extra nucleotides per turn in PX molecules is accommodated primarily through writhing, rather than by twisting that loosens the crossover point. Thus, the long segments involving major groove tangles are likely to be bent somewhat. Writhing of the helix axes can also lead to a twisting around the dyad axis, a feature also seen in the MD calculations.

Switchback DNA

We did not arrive at PX DNA by consciously seeking a molecule that would fulfill the characteristics described here; neither did it come from asking what would happen to parallel DX molecules if the backbone juxtapositions that appear to destabilize them were replaced with crossovers. Rather, the structure forced itself upon us when we tried to make a different new motif, termed switchback DNA. The nature of switchback DNA is illustrated in Figure 8. The essence of switchback DNA is that individual stacking domains are connected with their helix axes parallel to each other. The minimal unit for a stacking domain in this scheme is a half-turn of DNA, corresponding to roughly six nucleotide pairs. The drawing in the upper left of Figure 8 illustrates a switchback molecule containing four half-turns (unit tangles) of DNA. The sequence of this molecule can be designed from two strands, or from a single strand that is self-complementary in the switchback sense;45 four successive self-complementary hexamers (e.g., GAATTCCGTACGGCCGGCTAGCTA) would be a switchback self-complementary molecule. Note that the helix in this molecule is left-handed, although the axes of individual domains are all right-handed. The drawing in the upper center of Figure 8 shows the extension of this concept to stacking domains, that contain 1.5 turns of DNA (closer to 16 than to 18 nucleotide pairs). A version of this molecule with two stacking domains resembles the part of a DAO DX molecule between the crossovers.13 The drawing in the upper right shows the extension of the switchback on the upper left to contain five half-turn stacking domains.

Figure 8. Switchback DNA.

The drawing on the upper left shows a four one-half-turn switchback design. 5' ends are indicated by filled circles and 3' ends by arrowheads. Backbones are drawn in blue and red, and helix domain axes are drawn in green. The central upper panel shown the same notion extended to three-half-turn domains. The upper right panel illustrates a stable five one-half-turn domain. The bottom left panel is a rotated version of the upper left panel, with numbered domains that are differently color coded. The panel on the lower right shows that this sequence can assume a nicked PX structure that increases the stacking of the molecule. The nicks are shown away from the crossover points for clarity, but have been found to be near the crossover points.

We have been successful in preparing the molecule with five half-turn stacking domains. However, when we tried to prepare the molecule with four half-turn stacking domains (24 nucleotides, self-complementary in the switchback sense), we produced a very large aggregate, containing ca. 1000 bp. Our analysis of what occurred is illustrated on the bottom of Figure 8. The drawing in the bottom left is the same molecule shown in the upper left, but now the individual domains have been numbered and color-coded. The drawing in the bottom right illustrates an alternative arrangement for these pairing domains that corresponds to an infinite array of the 24-nucleotide molecule. This alternative motif is a nicked PX arrangement. When the nicks are removed in a model molecule whose ends coincide, the 6:6 arrangement is not stable (see Figure 2, lanes 2 and 3), but, as discussed above, the 6:5, 7:5 and 8:5 arrangements are stable. Switchback molecules will be described in detail elsewhere (ZS, HY, P. Constantinou & NCS, in preparation).

PX Molecules in DNA Nanotechnology and DNA-Based Computation

The PX molecule is particularly useful in DNA nanotechnology because its structure is amenable to topological variation; one can remove sections of the molecule and replace them with segments lacking two crossovers, shown in Figure 9a as molecules labeled 'JX2'. The bottom helices of the JX2 molecules are rotated 180° relative to the same portion in a pure PX molecule. Recently, we have used this strategy to produce a robust rotary sequence-dependent nanomechanical device;30 the device is driven by removing the green strands of the molecule in Figure 9b, using the method of Yurke et al.,46 and replacing them with the purple strands. Many different species can be constructed, using different sequences of green strands and purple strands. Thus, this system provides a starting point for DNA-based nanorobotics, because an assembly of N of these devices could, in principle, produce 2N distinct structural states.

Figure 9. The PX Motif as the Basis for a Robust Sequence Dependent Device.

Panel (a) illustrates the PX molecule and a variant that has two juxtapositions, rather than crossovers, termed JX2, Note that the topological difference between the two species leads to a half-turn difference in their structures. The PX molecule has the blue strands wrapped around the red strands for 1.5 turns, but the JX2 molecule only has a one-turn wrapping; this difference can be seen in the positions of the four letter labels flanking the helices, with A (red) and B (blue) at the top of each helix, but C (blue) and D (red) on opposite sides at the bottom. Panel (b) illustrates the machine cycle of a device based on the molecules shown in (a)30 Starting at the left, the PX molecule now contains two green strands that set its conformation to the PX conformation, but these molecules contain extensions that allow their removal when their complete biotinylated (black circles) complements are added to the solution (Process I), leaving an empty frame. The addition of the purple strands (Process II) sets the state of the device to the JX2 conformation. Processes III and IV act analogously to reset the state of the device to the PX conformation. By varying the sequence in the unpaired region of the frame, a large number of different devices can be designed.

The PX motif has other applications to nanotechnology. We have demonstrated recently that paranemic PX cohesion can be used in place of sticky ends.32 The use of PX motifs enables one to join two topologically closed molecules. This is important, because only closed molecules can be purified adequately, owing to their resistance to dissociation on denaturing gels.47 Furthermore, PX cohesion can be made as long as desired. This is a major advantage over sticky ends that are created by restriction enzymes that are 4–5 nucleotides in length at most; we have found that PX cohesion can bond molecules noncovalently more effectively that short sticky ends.32

Antiparallel DNA motifs containing fused helical domains have been suggested as useful elements in DNA-based computation;24 recently a successful experimental demonstration of this approach has been performed, in which a cumulative XOR calculation was carried out using triple crossover molecules.48 It is likely that PX DNA can be applied to this area, possibly with applications to string tiles.49 It is easy to design PX motifs containing more than two helical domains, but they have not yet been produced in the laboratory.

PX Molecules in Biological Systems

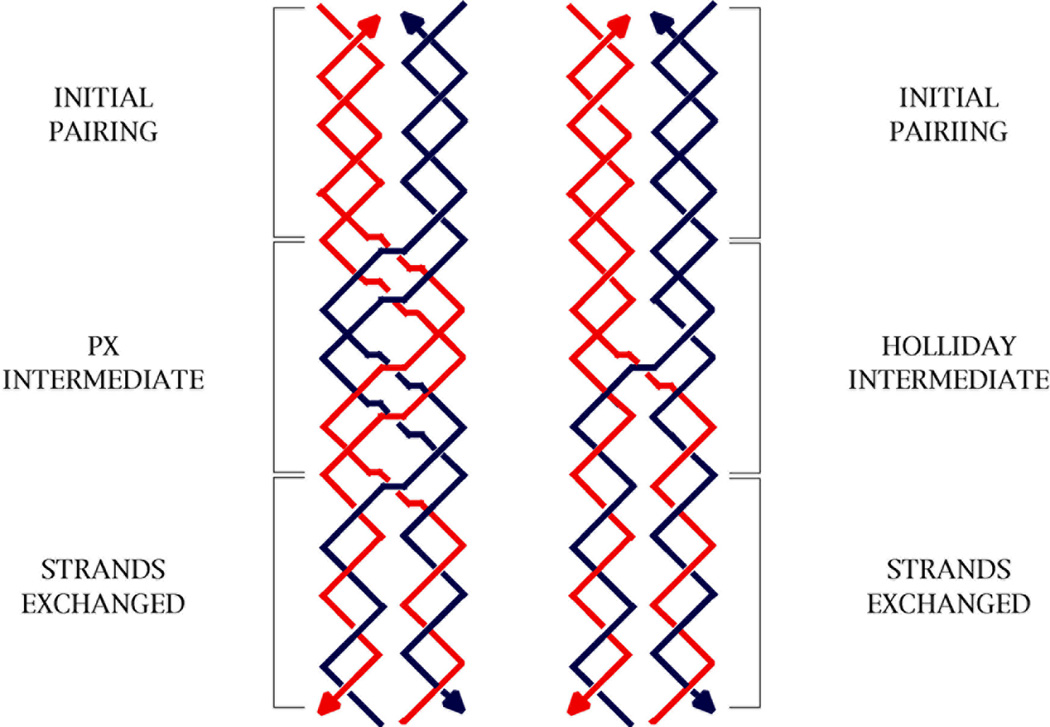

We have generated PX structures by using strands that cannot themselves form completely paired double helices. If one were to try to produce PX molecules from two double helical molecules, homology would be needed at least every other unit tangle. The minor groove tangles formed from red and blue strands in the PX-N molecule of Figure 1 are labeled 'H' to indicate the need for homology there; by contrast, the red-red and blue-blue major groove tangles are labeled 'U' to indicate that homology is unnecessary there. The PX-W molecule is labeled analogously, with the major groove tangles are labeled 'H' and the minor groove tangles labeled 'U'. It is unlikely that two homologous DNA duplex molecules would cohere in the PX motif unassisted; nevertheless, in a cellular context, we cannot yet exclude that proteins or superhelicity could stabilize the formation of PX structures by homologous double helices. For example, owing to their double-length period, their formation might stabilizea negatively supercoiled cyclic molecule that contains homologous regions. Like the Holliday junction, the PX structure appears capable of branch migration (see Figure 10), although it is unlikely that alternating-unit-tangle homology would support this isomerization. Branch migration of a Holliday junction is sensitive to homology at every step,50 and this would be true of the PX structure, as well, since it is a generalized Holliday junction. It is evident that PX DNA could provide a molecular framework for the DNA-based recognition of homology in cellular processes, including homologous recombination; this topic will be discussed elsewhere (X. Zhang, C. Mao and NCS, in preparation).

Figure 10. Branch Migration of PX Structures.

The left side shows a red and a blue double helix exchanging strands by the upward migration of a PX structure arbitrarily drawn to consist of one PX repeat (two Watson-Crick turns). If the length of the PX segment shrinks to a single crossover, it is identical with a Holliday junction, which is shown on the right. In both cases, branch migration leads to strand exchange.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Drs. Albert S. Benight, Charles Spink, Hui Wang, Junghuei Chen, Chengde Mao, William A. Goddard III, Nagarayan Vaidehi, Brad Chaires and Qingyi Yang for valuable assistance and insight in this project. This research has been supported by grants GM-29554 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, N00014-98-1-0093 the Office of Naval Research, DMI-0210844, EIA-0086015, DMR-01138790, and CTS-0103002 from the National Science Foundation, and F30602-01-2-0561 from DARPA/ AFSOR.

REFERENCES

- 1.Watson JD, Crick FHC. Nature. 1953;171:737–738. doi: 10.1038/171737a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Felsenfeld G, Davies DR, Rich A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1957;79:2023–2024. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frank-Kamenetskii MD, Mirkin SM. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 1995;64:65–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.000433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ono A, Ts'O POP, Kan L-S. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 1997;44:601–607. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williamson JR. Ann. Rev. Biophys. & Biomol. Str. 1994;23:703–730. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.23.060194.003415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gehring K, Leroy JL, Gueron M. Nature. 1993;363:561–565. doi: 10.1038/363561a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chernyi AA, Lusov YP, Il’ychova IA, Zibrov AS, Shchyolkina AK, Borisova OF, Mamaeva OK, Florntiev VL. J. Biomol. Str. & Dyns. 1990;8:513–527. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1990.10507826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holliday R. Genet. Res. 1964;5:282–304. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y, Mueller JE, Kemper B, Seeman NC. Biochem. 1991;30:5667–5674. doi: 10.1021/bi00237a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thaler DS, Stahl FW. Ann. Rev. Genet. 1988;22:169–197. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.22.120188.001125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun H, Treco D, Szostak JW. Cell. 1991;64:1155–1161. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90270-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwacha A, Kleckner N. Cell. 1995;83:783–791. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90191-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu T-J, Seeman NC. Biochem. 1993;32:3211–3220. doi: 10.1021/bi00064a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang S, Seeman NC. J. Mol. Biol. 1994;238:658–668. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun W, Mao C, Liu F, Seeman NC. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;282:59–70. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li X, Wang H, Seeman NC. Biochem. 1997;36:4240–4247. doi: 10.1021/bi9629586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sha R, Liu F, Seeman NC. Biochem. 2000;39:11514–11522. doi: 10.1021/bi0010468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sha R, Iwasaki H, Liu F, Shinagawa H, Seeman NC. Biochem. 2000;39:11982–11988. doi: 10.1021/bi001037z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winfree E, Liu F, Wenzler LA, Seeman NC. Nature. 1998;394:539–544. doi: 10.1038/28998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu F, Sha R, Seeman NC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:917–922. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mao C, Sun W, Seeman NC. Nature. 1999;397:144–146. doi: 10.1038/16437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiao S, Liu F, Rosen A, Hainfeld JF, Seeman NC, Musier-Forsyth KM, Kiehl RA. J. Nanopart. Res. 2002;4:313–317. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan H, Seeman NC. J. Supramol. Chem. 2001;1:229–237. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winfree E. In: DNA Based Computing. Lipton EJ, Baum EB, editors. Providence: Am. Math. Soc; 1996. pp. 199–219. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGavin S. J. Mol. Biol. 1971;55:293–298. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson JH. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. (USA) 1979;76:3641–3645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.8.3641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conley EC, West SC. Cell. 1989;56:987–995. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90632-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parkinson GN, Lee MPH, Neidle S. Nature. 2002;417:876–880. doi: 10.1038/nature755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seeman NC. NanoLett. 2001;1:22–26. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yan H, Zhang X, Shen Z, Seeman NC. Nature. 2002;415:62–65. doi: 10.1038/415062a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sumners DW. Math Intelligencer. 1990;12:71–80. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang X, Yan H, Shen Z, Seeman NC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:12940–12941. doi: 10.1021/ja026973b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seeman NC. J. Theor. Biol. 1982;99:237–247. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(82)90002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seeman NC. J. Biomol. Str. & Dyns. 1990;8:573–581. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1990.10507829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caruthers MH. Science. 1985;230:281–285. doi: 10.1126/science.3863253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tullius TD, Dombroski B. Science. 1985;230:679–681. doi: 10.1126/science.2996145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Churchill MEA, Tullius TD, Kallenbach NR, Seeman NC. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. (USA) 1988;85:4653–4656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.13.4653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kallenbach NR, Ma R-I, Seeman NC. Nature. 1983;305:829–831. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kimball A, Guo Q, Lu M, Kallenbach NR, Cunningham RP, Seeman NC, Tullius TD. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:6544–6547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Du SM, Zhang S, Seeman NC. Biochem. 1992;31:10955–10963. doi: 10.1021/bi00160a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.LaBean T, Yan H, Kopatsch J, Liu F, Winfree E, Reif JH, Seeman NC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:1848–1860. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang JC. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. (USA) 1979;76:200–203. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rhodes D, Klug A. Nature. 1980;286:573–578. doi: 10.1038/286573a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bates AD, Maxwell A. DNA Topology. Oxford: IRL Press; 1993. pp. 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seeman NC. Synlett. 2000;2000:1536–1548. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yurke B, Turberfield AJ, Mills AP, Jr., Simmel FC, Neumann JL. Nature. 2000;406:605–608. doi: 10.1038/35020524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen J, Seeman NC. Nature. 1991;350:631–633. doi: 10.1038/350631a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mao C, Sun W, Shen Z, Seeman NC. Nature. 1999;397:144–146. doi: 10.1038/16437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Winfree E, Eng T, Rozenberg G. In: DNA Computing. Condon A, Rozenberg G, editors. Vol. 2054. Springer, Berlin: LNCS; 2001. pp. 63–88. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Panyutin IG, Hsieh P. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;230:413–424. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.