Abstract

Aminoacyl-transfer RNA (tRNA) synthetases (RS) are essential components of the cellular translation machinery and can be exploited for antibiotic discovery. Because cells have many different RS, usually one for each amino acid, identification of the specific enzyme targeted by a new natural or synthetic inhibitor can be cumbersome. We describe the use of the primer extension technique in conjunction with specifically designed synthetic genes to identify the RS targeted by an inhibitor. Suppression of a synthetase activity reduces the amount of the cognate aminoacyl-tRNA in a cell-free translation system resulting in arrest of translation when the corresponding codon enters the decoding center of the ribosome. The utility of the technique is demonstrated by identifying a switch in target specificity of some synthetic inhibitors of threonyl-tRNA synthetase.

INTRODUCTION

The key function of an aminoacyl-transfer RNA (tRNA) synthetase (RS) is to charge tRNA with the cognate amino acid (1,2). Because these enzymes are essential for protein biosynthesis and exhibit significant sequence variation between bacteria and eukaryotes, they constitute valid antibiotic targets (3–5). For example, Ile-RS is the target of mupirocin, an antibiotic used as a topical treatment for bacterial skin infections (6). Other RS inhibitors are being investigated as new antibacterials (7–9). However, identifying new natural or synthetic inhibitors of RS is complicated for several reasons. A compound targeting one of the RS enzymes would appear as a general inhibitor of translation, whose activity in in vivo or in vitro protein synthesis assays would be hard to distinguish from any ribosome- or translation factor-targeting antibiotic. Even when it is known that a compound inhibits tRNA aminoacylation, it usually requires a significant experimental effort to identify which of the 20 cellular RS enzymes is affected. Moreover, if a series of derivatives is generated, it is relatively easy to test their activity against a specific target, but it is difficult to analyze whether the inhibitor incidentally acquired activity against another RS.

Here, we present a simple and straightforward assay, which we call SToPS for Selective Toeprinting in Pure System, which readily detects the activity of an RS inhibitor and uniquely identifies the targeted enzyme. The approach combines three components: (i) specifically designed artificial tester genes, (ii) a cell-free translation system composed of purified constituents (‘PURE’ system) (10,11) and (iii) the use of the primer extension inhibition (‘toeprinting’) technique to identify the site of translation arrest (12). In the SToPS assay, an artificial gene containing codons specifying all 20 amino acids is translated in the PURE system. If an inhibitor diminishes activity of one of the RS enzymes, the lack of the aminoacyl-tRNAs causes the ribosome to stall when the corresponding mRNA codon enters the decoding site. The site of stalling is uniquely identified by toeprinting. We tested the SToPS approach with several known inhibitors of bacterial RS enzymes and demonstrated its practical utility by identifying the switch in specificity in some synthetic derivatives of Thr-RS inhibitors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of DNA templates for the SToPS assay

The templates, RST1 and RST2 (Figure 1A), were generated by a four-primer PCR reaction that combined two long overlapping primers carrying the T7 promoter, the synthetic gene and the priming site for the toeprinting primer NV1 with two short primers, T7fwd and NV1 (Supplementary Table S1 in Supplementary Data section). A 100 µl of PCR reaction contained 0.1 µM of the long primers (e.g. RST1-fwd and RST1-rev), 1 µM of the short primers (T7fwd and NV1), 1X manufacturer-recommended PCR buffer I and 2 U of High Fidelity AccuPrime Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen). PCR conditions were 94°C, 2 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C, 30 s; 50°C, 30 s; 68°C, 15 s, followed by incubation for 1 min at 68°C. The PCR products were purified using Wizard SV gel and PCR clean-up system (Promega) and dissolved in H2O to a concentration of 0.2 µM.

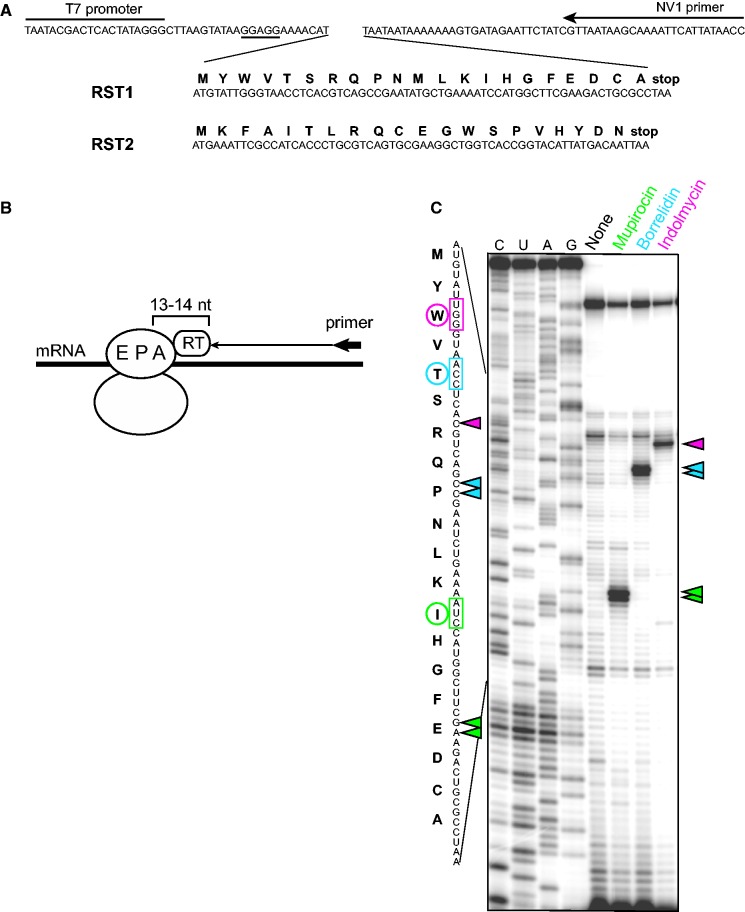

Figure 1.

Principle and validation of the SToPS technique. (A) Sequences of the coding segments of the synthetic genes RST1 and RST2. The T7 promoter and the 3′ untranslated regions where the toeprinting primer anneals are shown. The Shine-Dalgarno sequence is underlined. The amino acid sequences of the encoded polypeptides are indicated above their respective codons. (B) Principle of the primer extension inhibition (toeprinting) assay. When the RT encounters the stalled ribosome, the 3′ end of the synthesized cDNA is separated by 13–14 nt from the first base of the A-site codon (12). (C) Specific toeprint bands in the gel lanes, absent in the control sample, indicate codon-specific translation arrest at the RST1template (the template used in this experiment lacked the internal Met codon). The sites of arrest are indicated by colored triangles; the codons located in the A-site of the arrested ribosome and the encoded amino acids are highlighted with the same color.

Toeprinting

Toeprinting experiments were carried essentially as previously described (13) with some modifications as indicated in the following detailed protocol.

Primer labeling

In all, 20 pmol primer NV1 were combined with 30 µCi γ-[32P] ATP (6000 Ci/mmol) and 10 U T4 polynucleotide kinase (Thermo Scientific) in 10 µl of the enzyme buffer provided by the manufacturer [50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.6) at 25°C, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 0.1 mM spermidine]. The reactions were incubated at 37°C for 30 min, and then the enzyme was inactivated at 95°C for 2 min.

Translation

The PCR-generated DNA template was expressed in a cell-free transcription-translation system (PURExpress In Vitro Protein Synthesis kit, New England BioLabs) (11). For a typical reaction, 2 µl of solution A (kit), 1 µl of solution B (kit), 0.5 µl of DNA template (0.2 pmol/µl), 0.5 µl of radioactive primer (1 pmol), 0.2 µl of Ribolock RNAse inhibitor (40 U/µl, Thermo Scientific), 0.5 µl of the compound to be tested (10X solution in H2O) and 0.3 µl of H2O were combined in the reaction tube chilled on ice. Samples were incubated at 37°C for 20 min.

For the reactions that were run at a reduced concentration of amino acids, a modified solution A (11) was prepared to contain 125 mM Hepes-KOH (pH 7.6), 250 mM potassium glutamate, 15 mM magnesium acetate, 5 mM spermidine, 2.5 mM DTT, 25 µg/ml formyl donor (see later in the text), 50 mM creatine phosphate (Sigma), 5 mg/ml Escherichia coli tRNA (Roche), 15 µM each amino acid, 5 mM ATP, 5 mM GTP, 2.5 mM CTP, 2.5 mM UTP (pH of all the nucleotide triphosphate stocks was previously adjusted to 7.5). The formyl donor solution was prepared by dissolving 25 mg of calcium folinic acid (Sigma) in 2 ml of 50 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, adding 220 µl of 12 N HCl and incubating the reaction at room temperature for 3 h. The solution was diluted to 1 mg/ml with H2O and stored in 100 µl of aliquots at −20°C.

Primer extension

The reverse transcriptase (RT) mix was freshly prepared by combining five volumes of the dNTPs solution (4 mM each), 4 volumes of the Pure System Buffer (11) (9 mM magnesium acetate, 5 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.3), 95 mM potassium glutamate, 5 mM NH4Cl, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 1 mM spermidine, 8 mM putrescine, 1 mM DTT) and one volume of AMV RT (Roche, 20–25 U/µl). One µl of the RT mix was added to the 5 µl of translation reaction, and samples were incubated at 37°C for 15 min. Reactions were terminated by addition of 1 µl of 10 M NaOH and incubation for 15 min at 37°C. The samples were then neutralized by the addition of 0.8 µl of 12 N HCl. Two hundred microliters of resuspension buffer (0.3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.5), 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% SDS) was added to the reactions, and samples were extracted with phenol [Tris-saturated (pH 7.5–7.7)] and then with chloroform. Glycoblue solution (15 mg/ml, Ambion), 0.7 µl, was added to each sample, and DNA was precipitated by addition of 600 µl of ethanol. After removal of supernatants, the pellets were washed with 500 µl of 70% ethanol, air-dried and resuspended in 6 µl of formamide loading buffer (a 1-ml stock solution contains 980 µl of formamide (deionized, nuclease-free, Ambion), 20 µl of 0.5 M EDTA (pH 8.0), 1 mg of bromophenol blue and 1 mg of xylene cyanol). After heating the sample for 2 min at 95°C, 2 µl were loaded in the sequencing gel (see later in the text).

Sequencing reactions

The reactions were performed by adapting the protocol from the previously available fmol DNA Cycle Sequencing System kit (Promega). Approximately 150 ng of the DNA template were combined with 3 pmol of radiolabeled NV1 primer (see earlier in the text) and 1 µl of Hemo KlenTaq DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) previously diluted 40 times in storage buffer [10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 100 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Tween-20 (Sigma), 0.5% IGEPAL CA-630 (Sigma), 50% glycerol] in a total volume of 17 µl of sequencing buffer [50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 9.0) at 25°C, 2 mM MgCl2]. Four microliters of the mixture were distributed into four different PCR tubes containing 2 µl of the corresponding terminator solution (20 µM of each dNTP (dATP, dTTP, dCTP and 7-deaza-dGTP) and either 30 µM ddGTP, 350 µM ddATP, 600 µM ddTTP or 200 µM ddCTP). Sequencing reactions were run in a thermocycler at 95°C for 2 min, then 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 42°C for 30 s and 70°C for 60 s. After completion of the reaction, 3 µl of formamide loading buffer were added, the samples were heated for 2 min at 95°C and 2 µl were loaded on the sequencing gel alongside the toeprinting reactions.

Gel electrophoresis was run in a 6% sequencing gel (40 cm × 20 cm × 0.3 mm) at 40 W (ca. 1600 V) for ∼75 min until the first dye migrated 35 cm. Gels were transferred onto Whatman paper, dried and exposed to the phosphorimager screen for 2 h or overnight. Gels were visualized in a Typhoon phosphorimager (GE Healthcare).

Translation of GFP protein in the cell extract

The codon- and translation start- optimized synthetic gene of the enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP), cloned in the pJET plasmid under the control of the pA1 promoter (pJETgfp) (Supplementary Figure S2) was used as a template. The gene was expressed in the E. coli S30 system (E. coli S30 Extract System for Circular DNA, Promega). A typical translation reaction was assembled in a total volume of 10 µl and contained 75 ng of the pJETgfp plasmid, 0.5 µl of amino acid mixture minus cysteine (1 mM), 0.5 µl of amino acid mixture minus methionine (1 mM), 4 µl of S30 premix and 1.5 µl of S30 circular extract. Samples were placed in a well of a 384-well black/clear, tissue-culture treated, flat-bottom plate (BD Biosciences) and covered with the lid. Reactions were performed at 37°C in a microplate reader (Tecan), and fluorescence values were recorded over a period of 2–3 h taking readings every 20 min at λExc = 488 nm and λEm = 520 nm.

RESULTS

Synthetic genes for testing RS inhibitors

The SToPS method takes advantage of the in vitro toeprinting assay for identifying site-specific translation pausing caused by the paucity of a particular aminoacyl-tRNA. The toeprinting technique, which is based on inhibition of progression of RT by the stalled ribosome, allows detection of the precise site of translation arrest on mRNA (Figure 1B) (12).

For testing the activity of putative RS inhibitors, we designed two synthetic genes (named RST1 and RST2 for ‘RS Testers’) composed of 21 and 20 codons, respectively, specifying all 20 amino acids (Figure 1A). The translation of both templates is guided by a highly efficient ribosome binding site derived from the ermCL leader cistron (13). Hypothetically, a template with an initiator methionine codon followed by codons for the other 19 amino acids (like RST2) should allow determining amino acid-specific translation arrest at 18 of 20 codons (codons 3–20). The first two codons of the open reading frame (ORF), however, present specific problems. Inhibition of an RS corresponding to the second codon would result in a stalled initiation complex, whose formation can be caused by many general protein synthesis inhibitors (e.g. inhibitors of peptide bond formation or ribosome translocation), which could obscure the desired anti-RS activity (14,15). This problem is alleviated by the parallel use of two templates, RST1 and RST2, with shuffled codon sequence (Figure 1A). The first codon problem arises from the fact that inhibition of the Met-RS activity would interfere with initiation complex formation and thus would not lead to the appearance of a characteristic gel band in the SToPS approach. We reasoned, however, that at moderate concentrations of a putative Met-RS inhibitor, some level of translation initiation would be possible, but ribosomes that managed to bypass the initiation hurdle would pause when decoding an internal Met codon because of the limiting concentration of Met-tRNA. Therefore, we placed an additional methionine codon in the middle of the RST1 gene. Hypothetically, the combined use of the RST1 and RST2 templates provides a tool for monitoring inhibition of any RS.

We tested SToPS with three known and well-characterized inhibitors of bacterial RS enzymes. Mupirocin was originally isolated from Pseudomonas fluorescens (16) and targets bacterial Ile-RS (17,18) with ∼8000-fold selectivity over its mammalian counterpart (19). Borrelidin, an 18-membered polyketide macrolide from Streptomyces species with both antimicrobial (20) and antiangiogenic properties (21), inhibits Thr-RS from a range of prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms (22). Indolmycin, originally isolated from Streptomyces griseus, is a selective inhibitor of bacterial Trp-RS (23,24). The RST1 gene, equipped with a T7 RNA polymerase promoter, was expressed in the commercially available cell-free transcription-translation system (see ‘Materials and Methods’ section) in the absence or presence of 50 µM of either mupirocin, borrelidin or indolmycin, and the site of the translation arrest was determined by toeprinting (Figure 1C). Strong toeprint bands absent in the control sample appeared in the respective lanes of the gel, revealing ribosome stalling when the ‘hungry codon’ (Ile, Thr or Trp for mupirocin, borrelidin or indolmycin, respectively) entered the decoding (A) site. Similar results were obtained with the RST2 template (data not shown). Therefore, the SToPS technique readily and specifically detects RS inhibitory activity.

Testing target specificity of synthetic RS inhibitors

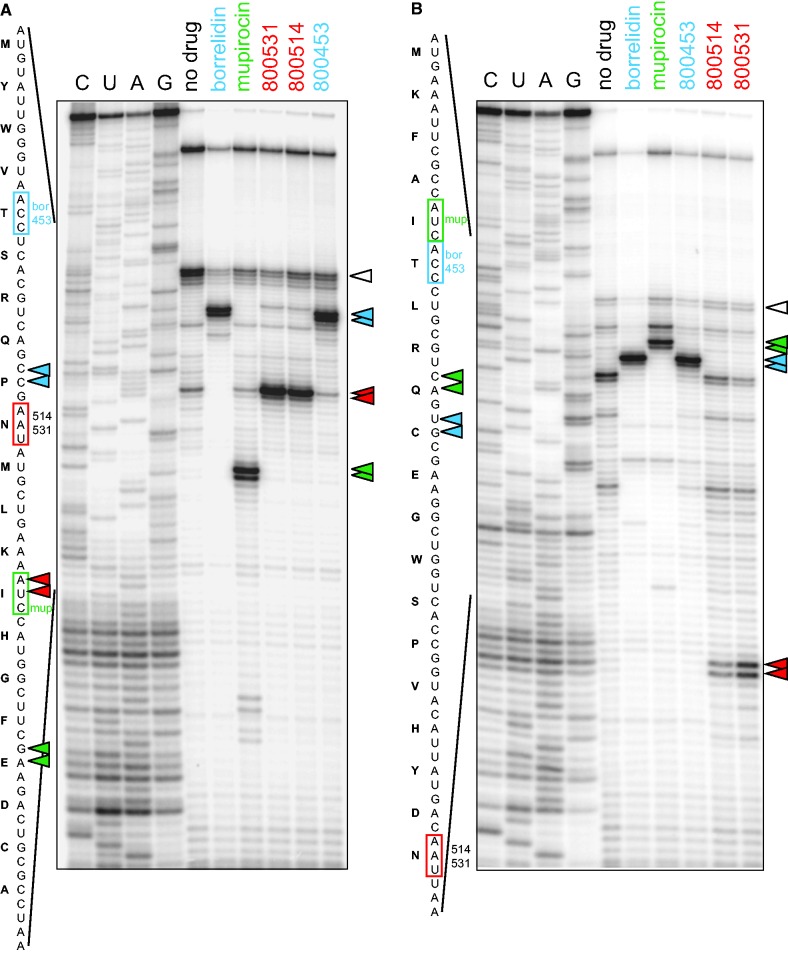

Having established the experimental system, we then used it to investigate target specificity of a series of compounds derived from the synthetic Thr-RS inhibitor 5′-O-[N-(threonyl)sulfamoyl] adenosine, a mimic of the threonyl adenosine monophosphate intermediate and a known competitive inhibitor of Thr-RS (8,25). These compounds were part of a structure-based drug design program to identify substrate analogs that inhibit Thr-RS (8,25). As anticipated, most of the tested compounds stalled the ribosome at the Thr codon of the RST1 template, confirming that these derivatives inhibited the activity of Thr-RS (Figure 2). However, three of the compounds, 800453, 800514 and 800531, did not notably slow down translation at any codon under standard experimental conditions. Nevertheless, when the effect of these compounds was tested in the S30 cell-free translation system prepared from an E. coli extract, they did exhibit notable protein synthesis inhibitory activity, even if less pronounced when compared with a control antibiotic, kanamycin (Supplementary Figure S1). Even marginal reduction of the amount of a specific aminoacyl-tRNA, which would remain undetectable by toeprinting, may have a much more profound effect on the translation of a 239 amino acid-long GFP protein because the hungry codon may be present in multiple locations within the gene. Therefore, we reasoned that compounds 800453, 800514 and 800531 may still possess some RS inhibitory activity, but their effect is not strong enough to sufficiently reduce the concentration of Thr-tRNA in the translation reaction. To render the SToPS assay more sensitive to a marginal inhibition of RS activity, the concentration of free amino acids in the PURE translation system was reduced from the standard 300 to 6 µM (see ‘Materials and Methods’ section for details). Under these conditions, we observed that translation in the presence of 50 µM of 800453 was arrested at the Thr codon revealing this compound as a weak inhibitor of Thr-RS (Figure 3A). Strikingly, the strong toeprint band that appeared in the 800514 and 800531 samples placed the arrested ribosome not at the expected Thr but at the Asn codon (Figure 3A). To verify this result, we repeated the experiment with the RST2 template and consistently observed that the compounds 800514 and 800531 caused translation arrest at the Asn codon, when Asn-tRNA was required for continuation of translation (Figure 3B). This unanticipated result suggested that the specificity of the inhibitory action of the compounds 800514 and 800531 may have switched and that these derivatives of a Thr-RS inhibitor acquired activity against Asn-RS.

Figure 2.

SToPS analysis of a series of synthetic Thr-RS inhibitors. Translation was directed by the RST1 template. A sample containing Thr-RS inhibitor borrelidin was included as a control. The toeprint bands are indicated by the filled triangles, and the corresponding (Thr) codon located in the A-site of the stalled ribosome is boxed. The open triangle indicates the band representing the ribosomes occupying the initiator AUG codon of the RST1 ORF; this band, which results from a slow initiation in the cell free system, is often observed in the toeprinting experiments.

Figure 3.

Compounds 800514 and 800531 inhibit the activity of Asp-RS. The SToPS assay was carried out using the templates RST1 (A) or RST2 (B) and decreased (6 µM) concentrations of amino acids in the PURE cell-free translation system. The Thr-RS inhibitor borrelidin and Ile-RS inhibitor mupirocin were included as controls. Open triangles indicates the initiating ribosomes.

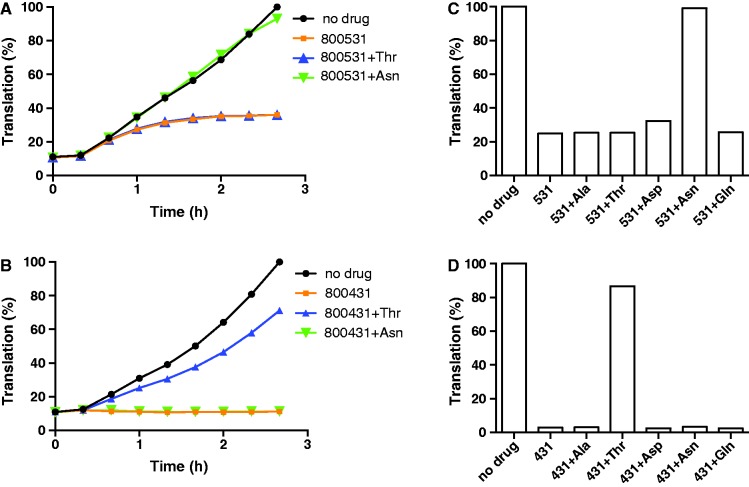

We verified this conclusion, which we reached exclusively using the SToPS approach, by using a principally different experimental set-up, where real-time expression of GFP protein was followed in an E. coli extract-based S30 cell-free translation system in the absence or presence of the inhibitors. As mentioned previously, at a sufficiently high concentration, compounds 800453, 800514 and 800531 inhibited GFP production (Supplementary Figure S1). Because the activity of a competitive RS inhibitor can be counterbalanced by increasing the concentration of the appropriate substrate (26), we tested whether excess of a specific amino acid would rescue translation inhibited by 800531 (Figure 4A). Compound 800431, an inhibitor of Thr-RS, was used as a control (Figure 4B). The standard concentration of amino acids in the commercial S30 cell-free translation system (Promega) is 100 µM. The addition of Thr to 2.6 mM specifically rescued translation inhibited by 800431, but not by 800531 (Figure 4B and D). In contrast, translation inhibited by 800531 could be rescued by excess (2.6 mM) of Asn (Figure 4A), whereas none of the other four tested amino acids (Thr, Asp, Gln or Ala) could offset the inhibition of translation caused by this compound (Figure 4C). This result verified the conclusion that compound 800531 (and by analogy, 800514) acquired a new anti-Asn-RS activity, thereby validating the results of the SToPS approach.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of in vitro translation by Thr-RS and Asn-RS inhibitors is relieved by the presence of an excess of corresponding amino acids. (A and B) Time course of the synthesis of GFP in the E. coli S30 transcription-translation system in the presence of 50 µM of compound 800531 (A) or 0.6 µM of compound 800431 (B). Where indicated, the concentrations of Asn or Thr were increased to 2.6 mM. (C and D) Relative fluorescence of GFP produced after 2.5 h in the presence of 50 µM of compound 800531 (C) or 0.4 µM of compound 800431 (D) in the reactions supplemented with an excess (2.6 mM) of the indicated amino acids.

DISCUSSION

We designed a novel, simple and straightforward SToPS approach for detecting inhibition of activity of individual RS. The currently available approaches, which are based on the use of in vitro aminoacylation assays with up to 20 radiolabeled amino acids (20,27–29) or the selection of resistant mutants combined with genetic mutation mapping (30), are costly, tedious and cumbersome. In contrast, the SToPS set-up is fairly inexpensive and can rapidly and uniquely define which of the RS enzymes is inhibited.

The first step in developing novel antibiotics is identifying inhibitors of a unique bacterial target. This is usually followed by the structure–activity relationship investigation and studies of toxicity and selectivity (31). SToPS is a qualitative technique designed to specifically assist with the first steps of drug discovery—finding promising inhibitors of bacterial RS enzymes and facilitating structure–activity relationship research. Once such RS inhibitors are identified in the model (E. coli) system, their activity against homologous RS from specific pathogens could be tested in more targeted studies. Toxicity and selectivity of the identified compounds could be further analyzed in whole cell assays and using available mammalian cell-free translation systems. However, in principle, the SToPS method could be also adopted for the studies of selectivity because the toeprinting approach has been successfully used with some eukaryotic cell-free systems (32,33). The use of SToPS could be beneficial over the traditional ways of improving selectivity of action of lead compounds, which require purification of large quantities of bacterial and eukaryotic enzymes (34).

The SToPS method was tested with three known RS inhibitors (borrelidin, mupirocin and indolmycin) and a range of new synthetic inhibitors. Although the activity of potent inhibitors used at 50 µM could be readily detected in the standard PURE transcription/translation reaction, the system can be additionally ‘sensitized’ for testing weak inhibitors. As we have shown, this can be easily achieved by simply reducing the concentrations of amino acids in the cell-free translation reaction from the original 300 µM down to 6 µM. Under these conditions, even a slight inhibition of the RS activity is apparently sufficient to significantly reduce the concentration of aminoacyl-tRNA to cause ribosome stalling at the cognate mRNA codon. If the solubility and availability of the inhibitor permits, a similar effect can likely be achieved simply by increasing the concentration of the compound to a sufficiently high level to cause ribosome arrest even without altering the amino acid concentrations. We do not know, however, to which extent the RS activity has to be inhibited to be detectable by SToPS.

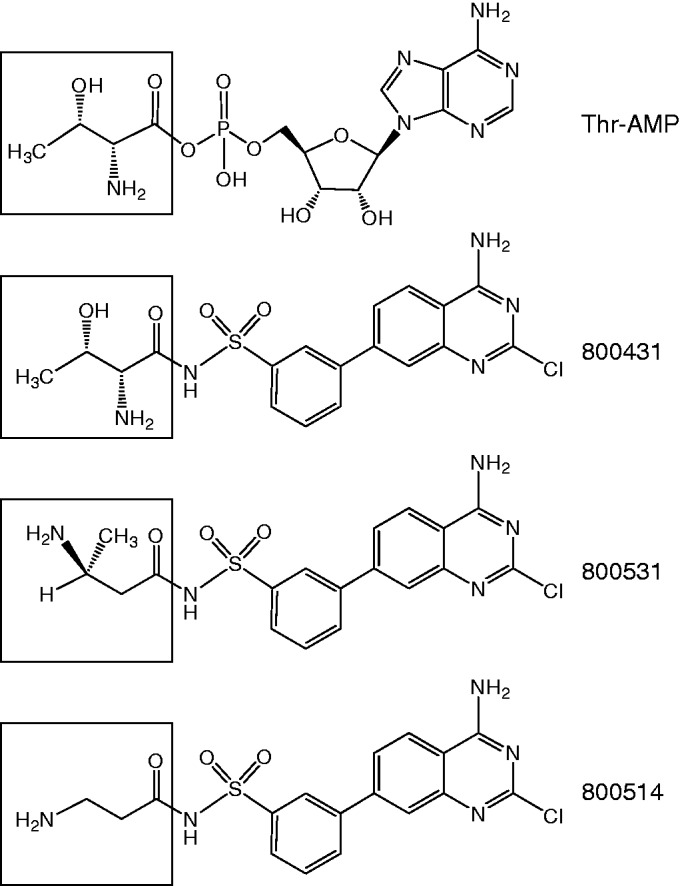

The use of our technique made it possible to detect an unexpected specificity switch in some of the compounds in a series of synthetic Thr-RS inhibitors. We observed that two of the inhibitors, 800514 and 800531, lost their activity against Thr-RS and instead acquired a weak inhibitory activity against Asn-RS. In contrast to the other compounds in the series (8), both 800514 and 800531 lack the Thr-like moiety, which explains the lack of inhibition of Thr-RS (Figure 5). Understanding why these compounds acquired activity against Asn-RS would require additional investigation and is beyond the scope of this study.

Figure 5.

Chemical structures of the RS inhibitors. The amino acid moiety of the Thr-RS inhibitor 800431 mimics the structure of Thr-AMP, an intermediate of the tRNA aminoacylation reaction catalyzed by Thr-RS. The structures of the compounds 800531 and 800514, which lost Thr-RS inhibitory activity and acquired Asn-RS inhibitory activity, lack similarity to Thr-AMP.

Other in vitro techniques have been advanced for determining the inhibitory activity targeted against RS enzymes. For example, recent work of Keller et al. (26) describes the use of amino acid compensation to identify Pro-RS as the target of the antifungal compound halofuginone. Such an approach, even if elegant, requires 20 assays (one per amino acid) to determine the target of the inhibitor and only works if the amino acid competes with the drug. The advantage of our method is that a single translation/toeprinting reaction tests at once for the activity of all RS enzymes and can identify the RS target of the inhibitor action irrespective of the mode of action. The SToPS assay provides for a high degree of multiplexing (Figure 1C) because it allows for parallel testing of a range of the inhibitors on one gel, and substituting capillary electrophoresis for slab gel electrophoresis can additionally increase the throughput.

Although we exclusively tested the method with few specific RS inhibitors, it should be applicable for detecting activity of an inhibitor of any bacterial RS. The use of two different synthetic genes, RST1 and RST2, with the principally different sequence of codons where none of the codon pairs is repeated should alleviate the ‘second codon problem’ discussed in the ‘Results’ section and may additionally lessen any context-specific effects, which may potentially obscure the results. Furthermore, the presence of an internal Met codon in RST1 should make it possible to detect Met-RS inhibitory activity: at the reduced concentrations of fMet-tRNA and Met-tRNA, some ribosomes will be able to bypass the initiation block but will pause during decoding of the internal Met codon. The lack of commercially available Met-RS inhibitors prevented us from experimentally testing this possibility.

The SToPS method can be used to identify RS inhibitors from both synthetic and natural sources. Importantly, relatively crude natural extracts can be directly analyzed in translation/toeprinting experiments (Orelle et al., in preparation). This approach can be further optimized to explore the activity of other protein synthesis inhibitors that target the ribosome or specific translation factors.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online: Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figures 1 and 2.

FUNDING

National Institutes of Health [R03 DA035191]; DTRA Chemical/Biological Technologies Directorate contract (in part) [HDTRA1-10-C-004]. Funding for open access charge: University of Illinois institutional funding and Research Open Access Article Publishing Fund.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Corinna Tuckey (New England Biolabs) for the advice on optimizing PURE system for the goals of this study, and Allen Borchardt and Gregory Haley for the synthesis of 800453, 800514 and 800531. They are also grateful to Kathryn and Bruce Solka for proofreading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ibba M, Soll D. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2000;69:617–650. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schimmel P. Aminoacyl tRNA synthetases: general scheme of structure-function relationships in the polypeptides and recognition of transfer RNAs. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1987;56:125–158. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.001013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurdle JG, O'Neill AJ, Chopra I. Prospects for aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase inhibitors as new antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005;49:4821–4833. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.12.4821-4833.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ochsner UA, Sun X, Jarvis T, Critchley I, Janjic N. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases: essential and still promising targets for new anti-infective agents. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2007;16:573–593. doi: 10.1517/13543784.16.5.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pohlmann J, Brotz-Oesterhelt H. New aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase inhibitors as antibacterial agents. Curr. Drug Targets Infect. Disord. 2004;4:261–272. doi: 10.2174/1568005043340515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gurney R, Thomas CM. Mupirocin: biosynthesis, special features and applications of an antibiotic from a gram-negative bacterium. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011;90:11–21. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3128-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lv PC, Zhu HL. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase inhibitors as potent antibacterials. Curr. Med. Chem. 2012;19:3550–3563. doi: 10.2174/092986712801323199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teng M, Hilgers M, Cunningham M, Borchardt A, Locke J, Abraham S, Haley G, Kwan B, Hall C, Hough G, et al. Identification of Bacteria Selective Threonyl tRNA Synthetase (ThrRS) Substrate Inhibitors by Structure–Based Design. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:1748–1760. doi: 10.1021/jm301756m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vondenhoff GH, Van Aerschot A. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase inhibitors as potential antibiotics. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011;46:5227–5236. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimizu Y, Inoue A, Tomari Y, Suzuki T, Yokogawa T, Nishikawa K, Ueda T. Cell-free translation reconstituted with purified components. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001;19:751–755. doi: 10.1038/90802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimizu Y, Ueda T. PURE technology. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010;607:11–21. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-331-2_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hartz D, McPheeters DS, Traut R, Gold L. Extension inhibition analysis of translation initiation complexes. Methods Enzymol. 1988;164:419–425. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(88)64058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vazquez-Laslop N, Thum C, Mankin AS. Molecular mechanism of drug-dependent ribosome stalling. Mol. Cell. 2008;30:190–202. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jerinic O, Joseph S. Conformational changes in the ribosome induced by translational miscoding agents. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;304:707–713. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vazquez-Laslop N, Ramu H, Klepacki D, Kannan K, Mankin AS. The key function of a conserved and modified rRNA residue in the ribosomal response to the nascent peptide. EMBO J. 2010;29:3108–3117. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fuller AT, Mellows G, Woolford M, Banks GT, Barrow KD, Chain EB. Pseudomonic acid: an antibiotic produced by Pseudomonas fluorescens. Nature. 1971;234:416–417. doi: 10.1038/234416a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughes J, Mellows G. Inhibition of isoleucyl-transfer ribonucleic acid synthetase in Escherichia coli by pseudomonic acid. Biochem. J. 1978;176:305–318. doi: 10.1042/bj1760305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakama T, Nureki O, Yokoyama S. Structural basis for the recognition of isoleucyl-adenylate and an antibiotic, mupirocin, by isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:47387–47393. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109089200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes J, Mellows G. Interaction of pseudomonic acid A with Escherichia coli B isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase. Biochem. J. 1980;191:209–219. doi: 10.1042/bj1910209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nass G, Poralla K, Zahner H. Effect of the antibiotic Borrelidin on the regulation of threonine biosynthetic enzymes in E. coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1969;34:84–91. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(69)90532-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams TF, Mirando AC, Wilkinson B, Francklyn CS, Lounsbury KM. Secreted Threonyl-tRNA synthetase stimulates endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:1317. doi: 10.1038/srep01317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruan B, Bovee ML, Sacher M, Stathopoulos C, Poralla K, Francklyn CS, Soll D. A unique hydrophobic cluster near the active site contributes to differences in borrelidin inhibition among threonyl-tRNA synthetases. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:571–577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411039200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Werner RG, Thorpe LF, Reuter W, Nierhaus KH. Indolmycin inhibits prokaryotic tryptophanyl-tRNA ligase. Eur. J. Biochem. 1976;68:1–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1976.tb10758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanamaru T, Nakano Y, Toyoda Y, Miyagawa KI, Tada M, Kaisho T, Nakao M. In vitro and in vivo antibacterial activities of TAK-083, an agent for treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001;45:2455–2459. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.9.2455-2459.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bovee ML, Pierce MA, Francklyn CS. Induced fit and kinetic mechanism of adenylation catalyzed by Escherichia coli threonyl-tRNA synthetase. Biochemistry. 2003;42:15102–15113. doi: 10.1021/bi0355701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keller TL, Zocco D, Sundrud MS, Hendrick M, Edenius M, Yum J, Kim YJ, Lee HK, Cortese JF, Wirth DF, et al. Halofuginone and other febrifugine derivatives inhibit prolyl-tRNA synthetase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012;8:311–317. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berg BH. The early influence of 17-beta-oestradiol on 17 aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases of mouse uterus and liver. Phosphorylation as a regulation mechanism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1977;479:152–171. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(77)90136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van de Vijver P, Vondenhoff GH, Kazakov TS, Semenova E, Kuznedelov K, Metlitskaya A, Van Aerschot A, Severinov K. Synthetic microcin C analogs targeting different aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. J. Bacteriol. 2009;191:6273–6280. doi: 10.1128/JB.00829-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walter RD, Ossikovski E. Effect of amoscanate derivative CGP 8065 on aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases in Ascaris suum. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1985;14:23–28. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(85)90102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rock FL, Mao W, Yaremchuk A, Tukalo M, Crepin T, Zhou H, Zhang YK, Hernandez V, Akama T, Baker SJ, et al. An antifungal agent inhibits an aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase by trapping tRNA in the editing site. Science. 2007;316:1759–1761. doi: 10.1126/science.1142189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Erb W, Zhu J. From natural product to marketed drug: the tiacumicin odyssey. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2013;30:161–174. doi: 10.1039/c2np20080e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Onouchi H, Nagami Y, Haraguchi Y, Nakamoto M, Nishimura Y, Sakurai R, Nagao N, Kawasaki D, Kadokura Y, Naito S. Nascent peptide-mediated translation elongation arrest coupled with mRNA degradation in the CGS1 gene of Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1799–1810. doi: 10.1101/gad.1317105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sachs MS, Wang Z, Gaba A, Fang P, Belk J, Ganesan R, Amrani N, Jacobson A. Toeprint analysis of the positioning of translation apparatus components at initiation and termination codons of fungal mRNAs. Methods. 2002;26:105–114. doi: 10.1016/S1046-2023(02)00013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Green LS, Bullard JM, Ribble W, Dean F, Ayers DF, Ochsner UA, Janjic N, Jarvis TC. Inhibition of methionyl-tRNA synthetase by REP8839 and effects of resistance mutations on enzyme activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009;53:86–94. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00275-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.