Abstract

Treatment for non–small cell lung cancer has been improving, with personalized treatment increasingly becoming a reality in the clinic. Unfortunately, these advances have largely been confined to the treatment of adenocarcinomas. Treatment options for squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the lung have lagged behind, partly because of a lack of understanding of the oncogenes driving SCC. Cytotoxic chemotherapy continues to be the only treatment option for many of our patients, and no genetic tests are clinically useful for patients with SCC. Recent advances in basic science have identified mutations and alterations in protein expression frequently found in SCCs, and clinical trials are ongoing to target these changes.

Background

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) accounts for about 30% of new cases of lung cancer in the United States. The patterns of incidence have changed over the decades as SCC has become less common, although it is still estimated to account for about 40,000 deaths annually in the United States (1). This reduction is thought to be due to decreased smoking rates as well as changes in the content of cigarettes. Until recently, SCC and adenocarcinoma had very similar overall survival; more recent analyses have shown that outcomes for metastatic adenocarcinoma are improved compared with patients with metastatic SCC (2), possibly due to new treatment options for adenocarcinoma.

For patients with localized or regional disease, treatment options differ very little between SCC and other subtypes of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Patients without involvement of mediastinal lymph nodes should undergo surgical evaluation, with consideration for adjuvant chemotherapy after resection (3). Patients with locally advanced disease, stage IIIA or IIIB, should be treated with multimodality therapy, often incorporating chemotherapy and radiation with or without surgery. These decisions, for the most part, are made without regard to histology.

Unfortunately, many patients with NSCLC present with metastatic disease or develop metastatic disease following local treatment. The past decade has seen a number of improvements in the treatment of metastatic NSCLC. For patients with EGF receptor (EGFR) mutations or anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) translocations, targeted therapies now represent standard front-line therapy (4, 5). A modern cytotoxic agent, pemetrexed, is used in the first-line (6), second-line (7), and maintenance (8) settings for patients with nonsquamous NSCLC. Bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody against the VEGF receptor (VEGFR), can prolong survival when added to chemotherapy (9). Unfortunately, all of these advances are more effective for patients with nonsquamous NSCLC. EGFR mutations and ALK translocations are not commonly found in patients with SCC, and bevacizumab is associated with an unacceptable risk of pulmonary hemorrhage (10). Pemetrexed is not effective in patients with SCC (6-8) and should not be used for these patients. Thus far, the only targeted agent approved for use in SCC of the lung is erlotinib, which has modest activity in patients with previously treated disease (11).

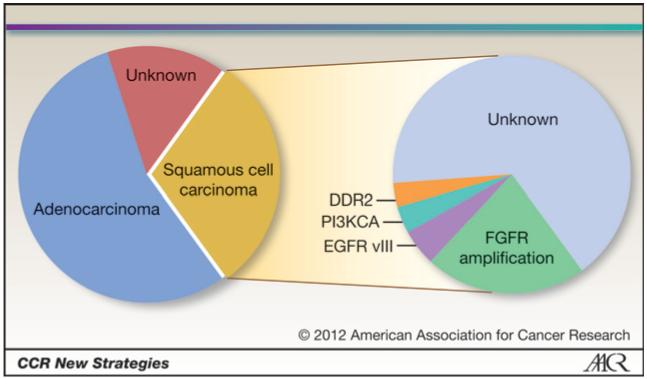

For patients with SCC, the standard of care is still cytotoxic chemotherapy. Standard front-line chemotherapy consists of a platinum-based doublet (12), and second-line therapy is often docetaxel (13) or erlotinib (11). Recent data indicate that similar to adenocarcinomas, SCCs are clinically, histologically, and molecularly heterogeneous tumors. For patients with SCC, research is ongoing to identify driver mutations (see Fig. 1) as well as targeted agents, including profiling and sequencing studies conducted as part of the Cancer Genome Atlas project (US National Cancer Institute). This article discusses some of the recent discoveries in the genetics of SCC as well as the direction of current and future research.

Figure 1.

Subsets of NSCLC and alterations in SCC. EGFR vIII, EGFR variant III mutation.

On the Horizon

Cytotoxic chemotherapy

Although much ongoing clinical research in lung cancer focuses on targeted agents, cytotoxic chemotherapy may play an important role in improving treatment. Paclitaxel is a frequently used drug in NSCLC treatment, but difficulties with administration include poor solubility and frequent reactions to the solvent used (cremaphor). To avoid some of these issues, nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel (nab-paclitaxel) was created. Some preclinical evidence also shows that albumin may increase drug delivery to tumors, possibly by interacting with secreted protein, acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC; refs. 14, 15). In a randomized phase III trial in women with breast cancer, nab-paclitaxel showed higher response rates and longer time to progression than solvent-based paclitaxel (16). Phase II trials of nab-paclitaxel in lung cancer as monotherapy (17) and in combination with carboplatin (18) have shown response rates as high as 39%. A phase III trial randomizing patients with NSCLC to carboplatin/nab-paclitaxel or carboplatin/paclitaxel showed a significantly higher response rate in the nab-paclitaxel arm (33% vs. 25%; P = 0.005). Preliminary estimates of progression-free survival were similar between the 2 arms (19). Several ongoing phase II trials combining carboplatin with nab-paclitaxel (NCT00729612 and NCT01236716) will study a variety of biomarkers, including SPARC, caveolin-1, and serum microRNAs.

EGF receptor

EGFR is expressed only at low levels in normal lung tissue, but it is overexpressed in preneoplasia and in many SCCs (20). Erlotinib, a small-molecule EGFR inhibitor, has been approved for use in NSCLC (including SCC) in maintenance therapy (21) and in previously treated disease (11), but benefits are modest and similar to those of cytotoxic therapy (22), with response rates less than 10%. Gefitinib, another EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor, seems to have similar activity to erlotinib, although it is not currently available in the United States (4, 22). EGFR mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain that confer sensitivity to gefitinib and erlotinib are found in a significant percentage of adenocarcinomas (23-25). These activating EGFR mutations have also been described in several patients with SCC (24, 26), but it has been hypothesized that these patients have incompletely sampled adenosquamous carcinoma rather than pure SCC (27). About 5% of SCCs have a deletion in the extracellular domain of EGFR (variant III EGFR mutation), but these mutations confer resistance to EGFR inhibitors in in vitro studies (28).

Cetuximab is a monoclonal antibody against EGFR and has proven efficacy in SCC of the head and neck (29, 30). In the FLEX study, patients with metastatic NSCLC received cisplatin and vinorelbine with or without cetuximab. Survival was significantly longer in the group receiving cetuximab (11.3 months vs. 10.1 months; P = 0.044; ref. 31). This trial enrolled all histologies of NSCLC, and on subgroup analysis, both patients with SCC and adenocarcinoma experienced benefit from the addition of cetuximab. A Southwest Oncology Group Study, SWOG 0819, is currently accruing patients to receive carboplatin and paclitaxel with or without cetuximab. Patients who are eligible (i.e., nonsquamous histologies) can also receive bevacizumab at the clinician’s discretion. Overall survival is a primary endpoint, and other objectives include the prospective study of EGFR copy number by FISH as a predictive marker for progression-free survival, as well as a variety of other EGFR-related biomarkers, including KRAS and EGFR mutations.

Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor

Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor (IGF-IR) is a cell-surface receptor with an intracellular tyrosine kinase domain. Binding of its ligand, IGF-I or IGF-II, activates the kinase domain and stimulates downstream signaling, including the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/mTOR pathway and the RAF/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, promoting cell proliferation and survival (32). IGF-IR plays an important role in carcinogenesis, contributing to cell growth, cell division, and protection from apoptosis. Aberrant IGF-IR signaling has been seen in many tumor types (33), and alterations in this pathway predict poor prognosis in early-stage lung cancers (34).

A randomized phase II trial randomizing patients to carboplatin and paclitaxel with or without figitumumab, an anti-IGF-IR monoclonal antibody, had promising results, with response seen in 78% of the patients with SCC treated with figitumumab (Pfizer; ref. 35). Unfortunately, a phase III registration trial was recently closed for futility, with a concern for an increased risk of early death (36).

Small-molecule IGF-IR inhibitors are also being actively studied. It is hoped that these agents have efficacy without some of the toxicities of anti-IGF-IR antibodies. In a phase II study (NCT01186861), erlotinib with or without OSI-906 (Astellas), an inhibitor of IGF-IR and the insulin receptor, is being studied in the maintenance setting in all histologic types of NSCLC. The primary endpoint is progression-free survival. Biomarker analyses, including analysis of the epithelial marker E-cadherin, will also be done.

Fibroblast growth factor receptor

The 4 members of the fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) family have important roles in the regulation of cell proliferation and survival (37). Mutations in these receptors have been described in other malignancies (38). In SCC, amplification of FGFR1 has been seen in more than 20% of SCCs but only rarely in adenocarcinoma (39, 40). In preclinical models, small-molecule inhibitors of this receptor can cause decreased cell growth in both cell lines and xenograft models (39, 40). A phase III study (NCT00805194) combining docetaxel with BIBF 1120 (Boehringer Ingelheim), a tyrosine kinase inhibitor with activity against FGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), and VEGFR, recently completed accrual, and an ongoing European phase I and II study (NCT 01346540) is enrolling patients with SCC to receive cisplatin and gemcitabine with or without BIBF 1120. Other inhibitors in this class are also in early-phase development, including BGJ398 (Novartis), AZD4547 (AstraZeneca), and dovitinib (Novartis).

Discoid domain receptor 2 kinase

Discoid domain receptor 2 (DDR2) is a kinase that interacts with collagen and has roles in cell adhesion and proliferation (41). Mutations have been described in lung cancer and can be found in about 4% of SCCs (42, 43). In cell line and xenograft models, growth of DDR2 mutant cells is inhibited by dasatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor already in widespread use for the treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia (42). In a clinical trial combining dasatinib with erlotinib, a patient with SCC who responded to treatment was found to have a DDR2 mutation (42). An ongoing single-arm phase II trial (NCT01491633) treats patients with SCC with dasatinib; DDR2 mutations are not required for enrollment, but all patients will be tested. Another phase II trial opening soon (NCT01514864) will enroll a molecularly selected group of patients, including patients with SCC and DDR2 mutations.

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase

PI3Ks have crucial roles in cell survival, growth, and motility. This pathway is downstream of multiple other proteins involved in NSCLC, such as B-raf, K-ras, and EGFR. The PI3K CA gene mutation (PI3KCA) gene encodes the catalytic domain of one of these kinases and is one of the most frequently mutated genes in human cancer, including frequent mutations in breast and gastric cancer (44). Mutations in PI3KCA have been described in about 3% of SCCs; copy number gains are present in about a third of tumors (45). These changes are found less frequently in adenocarcinomas. Knockdown of PIK3CA in cell lines with mutations or copy number gains inhibited growth (45). PI3K inhibitors have shown activity against lung cancer in vivo (46), and multiple agents targeting this kinase are in development. For patients with previously treated SCC, a phase II trial randomizing patients to docetaxel or PI3K inhibitor BKM120 (Novartis) is currently accruing (NCT1297491); those patients with previously untreated SCC are eligible for a randomized phase II trial of carboplatin and paclitaxel with or without GDC-0941 (Genentech), another PI3K inhibitor (NCT01493843). Other inhibitors of this pathway in development include BEZ-235 (Novartis), PX-866 (Oncothyreon), and BAY 80-6946 (Bayer).

AKT1/protein kinase B

The AKT1 gene encodes protein kinase B, which helps to mediate PI3K signaling. The E17K missense mutation in this gene causes increased activation of the PI3K pathway (47, 48). These mutations are found in 1% to 7% of SCCs and are not found in adenocarcinomas (27, 47, 49). MK-2066 (Merck), an Akt inhibitor, is currently being studied in several phase II trials. In one trial, patients with NSCLC and PIK3CA, AKT, or PTEN mutations will receive MK-2066 as a single agent (NCT01306045). In the BATTLE-2 trial (NCT01248247), patients with NSCLC will undergo biopsy prior to randomization to 1 of 4 targeted therapy arms. One arm includes MK-2066 in combination with erlotinib; another combines MK-2066 with AZD6244 (AstraZeneca), a MAP-extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) kinase (MEK) inhibitor. This combination is also being studied in other malignancies, including melanoma (NCT01519427).

Platelet-derived growth factor receptors

The PDGFs are a family of molecules that bind to PDGFRs and have an important role in angiogenesis (50). Multiple studies have shown that higher levels of these growth factors in tumor cells predict negative outcomes in resected NSCLC, including SCC (51-53). A number of agents currently in clinic use for other diseases, for example, sorafenib, sunitinib, and imatinib, inhibit PDGFR. Sorafenib, a multi-tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting PDGFR-β, VEGF, c-KIT, and B-raf, was studied in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel in a placebo-controlled phase III trial. Unfortunately, patients with SCC had an increased risk of mortality when treated with sorafenib, carboplatin, and paclitaxel compared with patients treated with carboplatin and paclitaxel alone (54). Another trial investigating a similar inhibitor, motesanib, in combination with chemotherapy, had to limit accrual to only patients with nonsquamous histology after an interim analysis revealed an increased risk of hemoptysis in patients with SCC (55). Because of the concern for increased toxicity with PDGFR inhibitors in SCC, further trials of these medications should be viewed with caution. Two anti-PDGFR antibodies are currently in development for NSCLC. MEDI-575 (MedImmune) is currently being studied in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel in NSCLC in a phase I and II trial (NCT01268059). Another phase II trial (NCT00918203) combines IMC-3G3 (ImClone) with carboplatin and paclitaxel. X-82 (Tyrogenex), a VEGFR/PDGFR inhibitor, is currently in phase I testing (NCT01296581).

SOX2

SOX2 is a transcription factor that has important roles in embryogenesis and stem cell maintenance. The SOX2 gene is amplified in about 20% of SCCs, and amplification is associated with higher SOX2 expression (56-59). Amplification may be an early event in carcinogenesis (60). Amplification and overexpression are found much less frequently in adenocarcinomas (56, 58). Studies suggest that higher SOX2 expression is associated with better prognosis in SCC (58).

Conclusions

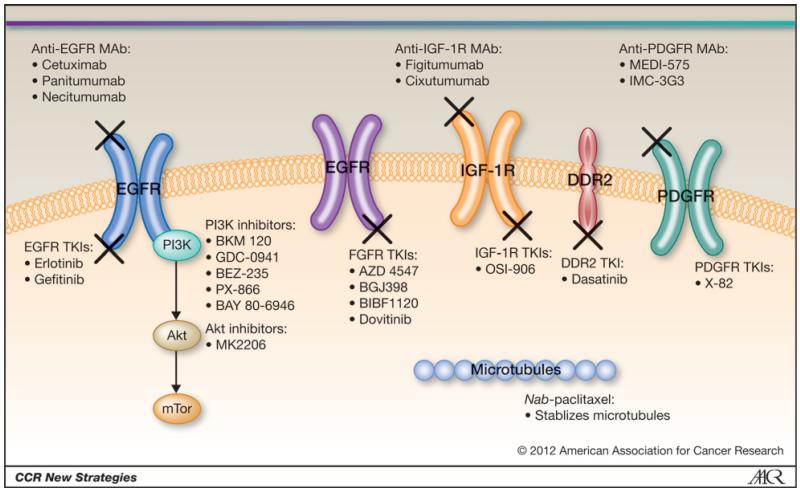

SCC of the lung is a growing area of interest in terms of molecular diagnostics and treatment options. Recent research has identified several potential driver oncogenes (Fig. 2; Table 1). Although many of these mutations affect only a small portion of patients with SCC, identifying them and using appropriate targeted agents could lead to significantly improved outcomes, as has been shown in patients with adenocarcinoma and EGFR mutations or ALK rearrangements. For example, dasatinib, when used in an unselected group of patients with NSCLC, does not seem to be particularly active (61); however, in a group of patients with DDR2 mutations, this drug may prove to be more effective. Future clinical trials should incorporate biomarker analyses for all patients. Patients with certain molecular abnormalities, including DDR2 mutations, PI3KCA mutations, FGFR1 amplifications, and AKT1 mutations, should be enrolled onto appropriate clinical trials. Through this personalization of care, we hope to improve outcomes for patients with SCC.

Figure 2.

Altered pathways in SCC of the lung and agents targeted against them. MAb, monoclonal antibody; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Table 1.

Targetable alterations in squamous cell carcinoma of the lung

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

E.S. Kim received honoraria from Genentech, Bayer/Onyx, Boerhinger, and Eli Lilly. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed by the authors.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morgensztern D, Waqar S, Subramanian J, Gao F, Govindan R. Improving survival for stage IV non-small cell lung cancer: a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results survey from 1990 to 2005. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:1524–9. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181ba3634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arriagada R, Bergman B, Dunant A, Le Chevalier T, Pignon JP, Vansteenkiste J International Adjuvant Lung Cancer Trial Collaborative Group Cisplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with completely resected non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:351–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mok TS, Wu Y-L, Thongprasert S, Yang CH, Chu D-T, Saijo N, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:947–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwak EL, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Solomon B, Maki RG, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1693–703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1006448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scagliotti GV, Parikh P, von Pawel J, Biesma B, Vansteenkiste J, Manegold C, et al. Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3543–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanna N, Shepherd FA, Fossella FV, Pereira JR, De Marinis F, von Pawel J, et al. Randomized phase III trial of pemetrexed versus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1589–97. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ciuleanu T, Brodowicz T, Zielinski C, Kim JH, Krzakowski M, Laack E, et al. Maintenance pemetrexed plus best supportive care versus placebo plus best supportive care for non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2009;374:1432–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61497-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, Brahmer JR, Schiller JH, Dowlati A, et al. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2542–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson DH, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny WF, Herbst RS, Nemunaitis JJ, Jablons DM, et al. Randomized phase II trial comparing bevacizumab plus carboplatin and paclitaxel with carboplatin and paclitaxel alone in previously untreated locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2184–91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, Tan EH, Hirsh V, Thongprasert S, et al. National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:123–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schiller JH, Harrington D, Belani CP, Langer C, Sandler A, Krook J, et al. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:92–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fossella FV, DeVore R, Kerr RN, Crawford J, Natale RR, Dunphy F, et al. Randomized phase III trial of docetaxel versus vinorelbine or ifosfamide in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-containing chemotherapy regimens. The TAX 320 Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2354–62. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.12.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.John TA, Vogel SM, Tiruppathi C, Malik AB, Minshall RD. Quantitative analysis of albumin uptake and transport in the rat microvessel endothelial monolayer. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;284:L187–96. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00152.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schiemann BJ, Neil JR, Schiemann WP. SPARC inhibits epithelial cell proliferation in part through stimulation of the transforming growth factor-beta-signaling system. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:3977–88. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-01-0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gradishar WJ, Tjulandin S, Davidson N, Shaw H, Desai N, Bhar P, et al. Phase III trial of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel compared with polyethylated castor oil-based paclitaxel in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7794–803. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rizvi NA, Riely GJ, Azzoli CG, Miller VA, Ng KK, Fiore J, et al. Phase I/II trial of weekly intravenous 130-nm albumin-bound paclitaxel as initial chemotherapy in patients with stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:639–43. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.8605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Socinski MA, Manikhas GM, Stroyakovsky DL, Makhson AN, Cheporov SV, Orlov SV, et al. A dose finding study of weekly and every-3-week nab-Paclitaxel followed by carboplatin as first-line therapy in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:852–61. doi: 10.1097/jto.0b013e3181d5e39e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Socinski MA, Bondarenko IN, Karaseva NA, Makhson AN, Vynnychenko I, Okamoto I, et al. Survival results of a randomized, phase III trial of nab-paclitaxel and carboplatin compared with cremophor-based paclitaxel and carboplatin as first-line therapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:7551. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meert AP, Martin B, Delmotte P, Berghmans T, Lafitte JJ, Mascaux C, et al. The role of EGF-R expression on patient survival in lung cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:975–81. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00296502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cappuzzo F, Ciuleanu T, Stelmakh L, Cicenas S, Szczésna A, Juhász E, et al. SATURN investigators Erlotinib as maintenance treatment in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:521–9. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim ES, Hirsh V, Mok T, Socinski MA, Gervais R, Wu Y-L, et al. Gefitinib versus docetaxel in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (INTEREST): a randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;372:1809–18. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61758-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, Gurubhagavatula S, Okimoto RA, Brannigan BW, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2129–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eberhard DA, Johnson BE, Amler LC, Goddard AD, Heldens SL, Herbst RS, et al. Mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor and in KRAS are predictive and prognostic indicators in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer treated with chemotherapy alone and in combination with erlotinib. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5900–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marchetti A, Martella C, Felicioni L, Barassi F, Salvatore S, Chella A, et al. EGFR mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer: analysis of a large series of cases and development of a rapid and sensitive method for diagnostic screening with potential implications on pharmacologic treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:857–65. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park SH, Ha SY, Lee JI, Lee H, Sim H, Kim YS, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations and the clinical outcome in male smokers with squamous cell carcinoma of lung. J Korean Med Sci. 2009;24:448–52. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2009.24.3.448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rekhtman N, Paik PK, Arcila ME, Tafe LJ, Oxnard GR, Moreira AL, et al. Clarifying the spectrum of driver oncogene mutations in biomarker-verified squamous carcinoma of lung: lack of EGFR/KRAS and presence of PIK3CA/AKT1 mutations. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:1167–76. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ji H, Zhao X, Yuza Y, Shimamura T, Li D, Protopopov A, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor variant III mutations in lung tumorigenesis and sensitivity to tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7817–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510284103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J, Azarnia N, Shin DM, Cohen RB, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:567–78. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vermorken JB, Mesia R, Rivera F, Remenar E, Kawecki A, Rottey S, et al. Platinum-based chemotherapy plus cetuximab in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1116–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pirker R, Pereira JR, Szczesna A, von Pawel J, Krzakowski M, Ramlau R, et al. FLEX Study Team Cetuximab plus chemotherapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (FLEX): an open-label randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1525–31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60569-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pollak MN, Schernhammer ES, Hankinson SE. Insulin-like growth factors and neoplasia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:505–18. doi: 10.1038/nrc1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baserga R, Peruzzi F, Reiss K. The IGF-1 receptor in cancer biology. Int J Cancer. 2003;107:873–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang YS, Wang L, Liu D, Mao L, Hong WK, Khuri FR, et al. Correlation between insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-3 promoter methylation and prognosis of patients with stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3669–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karp DD, Paz-Ares LG, Novello S, Haluska P, Garland L, Cardenal F, et al. Phase II study of the anti-insulin-like growth factor type 1 receptor antibody CP-751,871 in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin in previously untreated, locally advanced, or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2516–22. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.9331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jassem J, Langer CJ, Karp DD, Mok T, Benner RJ, Green SJ, et al. Randomized, open label, phase III trial of figitumumab in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin versus paclitaxel and carboplatin in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:7500s. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.4932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turner N, Grose R. Fibroblast growth factor signalling: from development to cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:116–29. doi: 10.1038/nrc2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cappellen D, De Oliveira C, Ricol D, de Medina S, Bourdin J, Sastre-Garau X, et al. Frequent activating mutations of FGFR3 in human bladder and cervix carcinomas. Nat Genet. 1999;23:18–20. doi: 10.1038/12615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weiss J, Sos ML, Seidel D, Peifer M, Zander T, Heuckmann JM, et al. Frequent and focal FGFR1 amplification associates with therapeutically tractable FGFR1 dependency in squamous cell lung cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:62ra93. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dutt A, Ramos AH, Hammerman PS, Mermel C, Cho J, Sharifnia T, et al. Inhibitor-sensitive FGFR1 amplification in human non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e20351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Labrador JP, Azcoitia V, Tuckermann J, Lin C, Olaso E, Mañes S, et al. The collagen receptor DDR2 regulates proliferation and its elimination leads to dwarfism. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:446–52. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hammerman PS, Sos ML, Ramos AH, Su C, Dutt A, Zhou W, et al. Mutations in the DDR2 kinase gene identify a novel therapeutic target in squamous cell lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:78–89. doi: 10.1158/2159-8274.CD-11-0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davies H, Hunter C, Smith R, Stephens P, Greenman C, Bignell G, et al. Somatic mutations of the protein kinase gene family in human lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7591–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Engelman JA, Luo J, Cantley LC. The evolution of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases as regulators of growth and metabolism. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:606–19. doi: 10.1038/nrg1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamamoto H, Shigematsu H, Nomura M, Lockwood WW, Sato M, Okumura N, et al. PIK3CA mutations and copy number gains in human lung cancers. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6913–21. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Engelman JA, Chen L, Tan X, Crosby K, Guimaraes AR, Upadhyay R, et al. Effective use of PI3K and MEK inhibitors to treat mutant Kras G12D and PIK3CA H1047R murine lung cancers. Nat Med. 2008;14:1351–6. doi: 10.1038/nm.1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Malanga D, Scrima M, De Marco C, Fabiani F, De Rosa N, De Gisi S, et al. Activating E17K mutation in the gene encoding the protein kinase AKT1 in a subset of squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:665–9. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.5.5485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carpten JD, Faber AL, Horn C, Donoho GP, Briggs SL, Robbins CM, et al. A transforming mutation in the pleckstrin homology domain of AKT1 in cancer. Nature. 2007;448:439–44. doi: 10.1038/nature05933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Do H, Solomon B, Mitchell PL, Fox SB, Dobrovic A. Detection of the transforming AKT1 mutation E17K in non-small cell lung cancer by high resolution melting. BMC Res Notes. 2008;1:14. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferrara N, Kerbel RS. Angiogenesis as a therapeutic target. Nature. 2005;438:967–74. doi: 10.1038/nature04483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Donnem T, Al-Saad S, Al-Shibli K, Andersen S, Busund LT, Bremnes RM. Prognostic impact of platelet-derived growth factors in non-small cell lung cancer tumor and stromal cells. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:963–70. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181834f52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kawai T, Hiroi S, Torikata C. Expression in lung carcinomas of platelet-derived growth factor and its receptors. Lab Invest. 1997;77:431–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shikada Y, Yonemitsu Y, Koga T, Onimaru M, Nakano T, Okano S, et al. Platelet-derived growth factor-AA is an essential and autocrine regulator of vascular endothelial growth factor expression in non-small cell lung carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7241–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scagliotti G, Novello S, von Pawel J, Reck M, Pereira JR, Thomas M, et al. Phase III study of carboplatin and paclitaxel alone or with sorafenib in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1835–42. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Langer CJ, Besse B, Gualberto A, Brambilla E, Soria JC. The evolving role of histology in the management of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:5311–20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.8126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yuan P, Kadara H, Behrens C, Tang X, Woods D, Solis LM, et al. Sex determining region Y-Box 2 (SOX2) is a potential cell-lineage gene highly expressed in the pathogenesis of squamous cell carcinomas of the lung. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e9112. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bass AJ, Watanabe H, Mermel CH, Yu S, Perner S, Verhaak RG, et al. SOX2 is an amplified lineage-survival oncogene in lung and esophageal squamous cell carcinomas. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1238–42. doi: 10.1038/ng.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilbertz T, Wagner P, Petersen K, Stiedl AC, Scheble VJ, Maier S, et al. SOX2 gene amplification and protein overexpression are associated with better outcome in squamous cell lung cancer. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:944–53. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hussenet T, Dali S, Exinger J, Monga B, Jost B, Dembelé D, et al. SOX2 is an oncogene activated by recurrent 3q26.3 amplifications in human lung squamous cell carcinomas. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e8960. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McCaughan F, Pole JC, Bankier AT, Konfortov BA, Carroll B, Falzon M, et al. Progressive 3q amplification consistently targets SOX2 in pre-invasive squamous lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:83–91. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0005OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Johnson FM, Bekele BN, Feng L, Wistuba I, Tang XM, Tran HT, et al. Phase II study of dasatinib in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4609–15. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.5474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.