Abstract

It has been estimated that 24 million Americans have diabetes, many of whom are Medicare beneficiaries. These individuals carefully monitor their blood glucose levels primarily through the use of in-home blood glucose testing kits. Although the test is relatively simple, the cumulative expense of providing glucose test strips and lancets to patients is ever increasing, both to the Medicare program and to uninsured individuals who must pay out-of-pocket for these testing supplies. This article discusses the diabetes durable medical equipment (DME) coverage under Part B Medicare, the establishment and role of DME Medicare administrative contractors, and national and local coverage requirements for diabetes DME suppliers. This article also discusses the federal government’s ongoing concerns regarding the improper billing of diabetes testing supplies. To protect the Medicare Trust Fund, the federal government has contracted with multiple private entities to conduct reviews and audits of questionable Medicare claims. These private sector contractors have conducted unannounced site visits of DME supplier offices, interviewed patients and their families, placed suppliers on prepayment review, and conducted extensive postpayment audits of prior paid Medicare claims. In more egregious administrative cases, Medicare contractors have recommended that problematic providers and/or DME suppliers have their Medicare numbers suspended or, in some instances, revoked. More serious infractions can lead to civil or criminal liability. In the final part of this article, we will examine the future of enforcement efforts by law enforcement and Medicare contractors and the importance of understanding and complying with federal laws when ordering and supplying diabetes testing strips and lancets.

Keywords: durable medical equipment, False Claims Act, Medicare, Medicare administrative contractor, Medicare Trust Fund

Introduction

It has been estimated that 24 million Americans have diabetes, many of whom are Medicare beneficiaries. These individuals carefully monitor their blood glucose levels primarily through the use of a test that measures the level of glucose in their blood. Although the test is relatively simple, the cumulative expense of providing glucose test strips and lancets to patients is ever increasing, both to the Medicare program and to uninsured individuals who must pay out of pocket for these supplies. This article discusses the current law enforcement landscape facing ordering physicians and durable medical equipment (DME) suppliers. It also examines a number of risk areas to be contemplated and avoided when ordering or supplying diabetes testing supplies to patients.

Background: Medical Necessity, Coverage, and Payment Issues

History of Medicare and Medicaid Programs1

On July 30, 1965, President Lyndon Johnson signed into law dramatic changes to the existing health care delivery system under Chapter 7, Subchapters XVIII2 and XIX3 of the Social Security Act (Act). This legislation enacted the Medicare and Medicaid programs, both of which were to be administered by the secretary for the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Medicare is a federally funded program and provides health insurance coverage for eligible older and disabled Americans. Medicare eligibility is not dependent on financial need or condition. In contrast, Medicaid is a medical care program that is jointly funded by the federal and state governments. Only eligible low-income individuals can qualify for participation in the Medicaid program.

The secretary of HHS has been delegated overall authority in the administration and management of the Medicare and Medicaid programs. The secretary is authorized to issue guidance covering these programs but is not required to promulgate regulations or policies that “either by default rule or by specification, address every conceivable question” that may arise.4 The secretary typically administers these programs through the direct issuance of formal and informal guidance. The secretary may also allow “specific applications of a rule [to] evolve” through the administrative appeals process.4

Pursuant to 42 U.S.C.A. § 1395y(a)(1)(A),5 Medicare covers items and services that are “reasonable and necessary for the diagnosis and treatment of illness or injury or to improve the functioning of a malformed body member.” The secretary administers the Medicare program through an agency of HHS known as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). As set out in the HHS Quality Improvement Organization Manual, Chapter 1: Background and Responsibilities, § 1015,6 the CMS’s primary mission is to promote the timely delivery of appropriate, quality health care to beneficiaries, ensure that beneficiaries are aware of the services for which they are eligible, ensure that those services are accessible, and promote efficiency and quality in the programs under its administration.

Collectively, CMS-administered health insurance programs cover over 90 million Americans.7 Approximately 4.5 million Medicare claims alone are processed each day.8 Despite the extraordinary scope of the CMS’s responsibilities, the agency’s staff size is quite small, employing less than 5000 employees.

To accomplish its broad program obligations, the CMS has contracted with various private entities (which are primarily “for-profit” in nature) to process and pay Medicare claims filed by participating health care suppliers and providers. In some cases, these contractors also serve as the CMS’s first-line representatives with participating providers and suppliers, interacting with them on an ongoing basis to address Medicare coverage questions, coding/billing concerns, and program participation issues that may arise. The CMS also relies on third-party contractors to perform medical reviews of provider claims, conduct periodic site visits, and initiate postpayment and prepayment audits of Medicare claims.

Establishment of Durable Medical Equipment Medicare Administrative Contractors

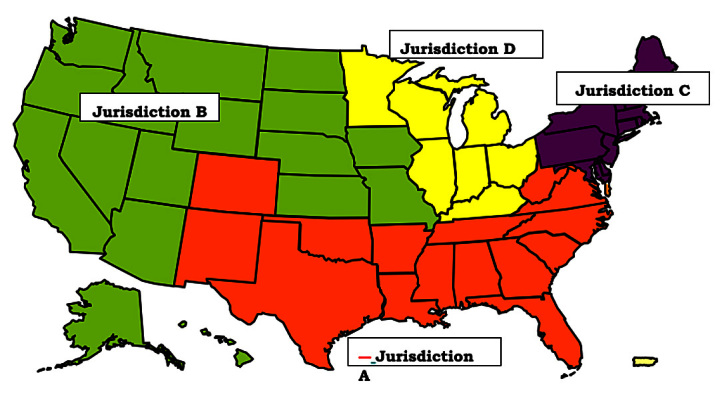

Pursuant to § 911 of the Medicare Prescription Drug Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003, the CMS has consolidated the handling and processing of Part A and Part B Medicare claims. Broadly speaking, Medicare Part A claims include inpatient hospital and skilled nursing facility claims. In contrast, Medicare Part B claims include physician services and most outpatient care claims. The CMS has combined these responsibilities to newly formed Medicare administrative contractors (MACs). Specialty MAC jurisdictions have been established to handle hospice and home health claims. Separate DME MACs have been set up in four jurisdictions to process claims filed by participating suppliers for covered DME, orthotic, prosthetic, and related items under Medicare Part B (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Map showing the four jurisdictions assigned to DME MACs. Jurisdiction A, National Heritage Insurance Company; Jurisdiction B: National Government Services LLC; Jurisdiction C: CIGNA Government Services; Jurisdiction D: Noridian Administrative Services.

The term “DME” is defined as medical equipment that can withstand repeated use, is used primarily and customarily to serve a medical purpose, is generally not useful to a person in the absence of an illness or injury, and is appropriate for use in the home (42 CFR § 414.202).9 The general basis for providing Medicare coverage for DME is found in § 1861(s)(6) of the Act, as amended by § 4062 of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987.

Blood Glucose Test Strips and Lancets May Qualify for Coverage and Payment Under Medicare Part B

Under §§ 1832(a)(1), 1861(s)(6), and 1861(n) of the Social Security Act, home blood glucose test strips and lancets prescribed by a qualified physician to treat a diabetes patient may qualify for coverage and payment under Medicare Part B as long as the supplies are medically necessary and meet certain requirements specified by the CMS and DME MACs working on the CMS’s behalf. These coverage and documentation requirements are intended to help ensure that test strips and lancets ordered for use by a Medicare beneficiary are, in fact, medically necessary. Unfortunately, many physicians and suppliers are either unaware of these detailed requirements or do not recognize the importance of properly maintaining supporting documentation.10

National Coverage Determination and Local Coverage Determination Documentation Requirements

Although the CMS has not issued national coverage determination (NCD) guidance covering the medical necessity and usage of blood glucose test strips, it has addressed the program coverage of blood glucose monitors (see Medicare National Coverage Determinations Manual, Pub. No. 100-03, Chapter 1, § 40.2, effective June 19, 2006).11 As the NCD reflects, the CMS did not address the coverage and payment of medically necessary test strips or lancets. In an effort to address the medical necessity, coverage, documentation, and payment of these essential supplies, each of the four DME MACs have issued local coverage determination (LCD) guidance that addresses the various guidelines and rules to be followed by ordering physicians and suppliers of test strips and lancets. Jurisdictions A and B have issued LCD L11530.12 Jurisdiction C has issued LCD L11520.13 Finally, Jurisdiction D has issued LCD L196.14

Local Coverage Determination Guidance Covering Blood-Glucose Test Strips and Lancets Has Been Issued and Specifically Addresses the Quantity of Test Strips and Lancets That Are Likely to Be Covered by Medicare

As a review of the LCD guidance cited earlier will show, each of the applicable LCDs specify the coverage, payment rules, and documentation requirements that must be met in order for test strips and lancets to qualify for coverage by Medicare. Importantly, all four LCDs limit coverage to 100 test strips and 100 lancets per Medicare patient per month if a Medicare beneficiary is insulin dependent. This quantity is intended to permit insulin-dependent beneficiaries to test their blood glucose levels up to three times per day. When a Medicare beneficiary is not insulin dependent, a contractor may only cover up to 100 test strips and 100 lancets every three months.

In certain instances, a Medicare beneficiary may need to assess their blood glucose levels more frequently than an LCD generally permits. Medicare permits more frequent testing as long as it is medically necessary and appropriate in light of a beneficiary’s clinical profile and medical needs. The invoice submissions associated with these situations are sometimes referred to as “high utilization” claims. Medical documentation supporting the more frequent use of test strips must be maintained in a treating physician’s records (and ultimately the supplier’s records) in order to support a patient’s high utilization of testing supplies.

Administrative, Civil, and Criminal Enforcement Measures to Ferret Out Improper Billing and Coding Practices Are Increasing

There are a number of agencies tasked with the investigation and enforcement of the laws, rules, and regulations governing the coverage and payment of claims billed to Medicare by treating/ordering physicians and DME suppliers. Providers engaging in wrongdoing can be subject to administrative action, civil liability, and criminal prosecution. Moreover, depending on the facts and the culpability of a party, the government may choose to pursue one, two, or all three of these avenues of recourse. Each of these enforcement options are discussed here.

Administrative Actions

It is essential to keep in mind that the government has been accumulating utilization data related to both services and supplies since the passage of the Medicare and Medicaid programs in 1965. Today, “data mining” is an essential tool used by the CMS and its contractors to identify “outliers”—individuals or entities who bill differently than their peers. The CMS contractors exercise a wide degree of discretion and are expected to develop techniques and methodologies aimed at identifying health care providers and suppliers who may be engaging in improper treatment, coding, and/or billing practices. Through the application and assessment of historical billing and claims data, even the most ethical provider or supplier may appear to be an outlier and find themselves subjected to an unannounced visit, audit, or referral to law enforcement for further investigation.

The CMS and its contractors exercise a wide range of administrative enforcement authorities that may be used to examine, address, and/or deter potential and actual wrongdoing or fraud by a treating/ordering physician or DME supplier. In most regions of the country, the primary contractor auditing the Medicare claims of both nonhospital providers and suppliers are zone program integrity contractors (ZPICs). Possible administrative actions taken by ZPICs have included, but are not limited to the following:

Unannounced Site Visits to Your Practice or Office. There are no statutory restrictions that prevent a ZPIC from “unexpectedly” visiting your practice or office and requesting to see documentation related to Medicare claims you have ordered or submitted to the program for payment. Moreover, as a participating physician or DME supplier, you have an obligation to cooperate with the contractor’s review. Should ZPIC representatives show up at your medical practice or office, you will likely find that the ZPIC’s auditors are knowledgeable, experienced, and professional in their dealings with you and your staff. When they do show up, they will likely already have a listing of the claims-related medical records and the specific records to be pulled from your files. The ZPICs have sometimes been known to show up with their own scanner or copier. This has led to problems for providers later on because they failed to request a copy of any documents taken by the contractor before it left. Should a ZPIC ask you to make copies, the contractor will often identify a handful of documents they intend to take with them at that time and ask that you forward additional supporting documentation by an agreed deadline. The ZPICs have requested both medical record and business-related documentation, such as contracts with medical directors and any leases for space. Notably, these business-related documents may be used to identify possible violations of the federal Anti-Kickback Statute or the civil False Claims Act.

Unannounced Interviews of Diabetes Patients and Their Families. Since 2012, ZPIC auditors have been reported to have unexpectedly visited the homes of diabetes patients who are alleged to be high utilization users of blood glucose test strips and lancets. During these visits, ZPIC representatives (typically two people, one of whom is a registered nurse) have interviewed patients in an effort determine whether it was medically necessary for the patient to check his or her blood glucose levels more frequently than one would normally expect (in consideration of the patient’s specific clinical profile). After interviewing a patient, a ZPIC would then conclude whether, in their professional opinion, the high utilization claims billed to Medicare were medically necessary. Unfavorable medical necessity determinations by a ZPIC can lead to a postpayment audit of prior paid claims, a recommendation to the CMS that a DME supplier should be suspended, or, in extreme cases, a recommendation to the CMS that a DME supplier’s Medicare number should be revoked.

The HHS’s Office of Inspector General (OIG) has expressed concern that providers and suppliers are improperly ordering and/or supplying Medicare beneficiaries with excessive blood glucose test strips and lancets. In mid 2012, the HHS OIG issued a report, Medicare Contractors Lacked Controls to Prevent Millions in Improper Payments for High Utilization Claims for Home Blood Glucose Test Strips and Lancets, A-09-11-02027 (June 2012), that examined whether the four DME contractors engaged by the CMS to process high-utilization claims for home blood glucose test strips and lancet supplies submitted by Part B suppliers properly handled these claims.15 The supplies at issue were paid by the four DME contractors in calendar year 2007. The HHS OIG found that only 97 of the 400 (approximately 24%) paid high-utilization claims qualified for coverage and payment. The remaining 303 claims (76%) had one of more deficiencies which rendered it non-payable. The four major areas of deficiency are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Four Major Areas of Deficiency in “High-Utilization” Claims Examined

| Four major areas of deficiency were noted. These included the following: | |

| 1 | Over half of the claims reviewed (222 out of the 400 claims evaluated) were not supported by adequate documentation to justify the patient’s need for these additional diabetes testing supplies. Specific documentation problems included the following:

|

| 2 | The HHS OIG further found that the medical documentation for more than a quarter of the claims (117 out of 400) did not note whether refill requirements had been met. |

| 3 | The patient’s medical documentation did not include a necessary physician order for the supplies in almost a quarter of the claims (90 out of 400 claims) evaluated by the four DME contractors. |

| 4 | Proof-of-delivery records were missing in almost 10 per cent of the claims evaluated (33 of 400 claims). Notably, suppliers are required to maintain proof-of-delivery documentation for seven years. |

Based on these findings, the HHS OIG concluded that the four DME MACs improperly paid approximately $209 million to participating Medicare suppliers (out of a total of $275 million paid in fiscal year 2007). In light of the HHS OIG’s findings, physicians and DME suppliers should reevaluate both their documentation and business practices to better ensure that high-utilization claims are only ordered and/or submitted in cases where the medical need for this frequency of testing is both fully documented and there is clear medical necessity for this frequency of testing. Moreover, refills must be fully supported by the record.

-

Prepayment Reviews. With increasing frequency, both treating and ordering physicians and DME suppliers are finding themselves being placed on prepayment review by a ZPIC or DME MAC. When a physician or supplier is placed on prepayment review, the CMS contractor has essentially taken the position that an entity’s claims should not be paid prior to being reviewed to ensure that the claims qualify for medical necessity, coverage, and payment. While this administrative remedy may sound like an imminently reasonable course of action to take, it has been our experience that few, if any, treating/ordering physicians or suppliers maintain a proverbial “rainy day” fund to pay employees and cover their expenses until the DME MAC determines whether or not specific claims should be paid. As a result, participating providers and suppliers placed on prepayment review or audit may be forced into bankruptcy because their cash flow has been disrupted.

Importantly, physicians and DME suppliers placed on prepayment review cannot challenge the action through an administrative appeals process. The only way to be removed from this status is to satisfy the CMS contractor that it is no longer necessary to review the supporting documentation of each claim before a payment determination is made.

Postpayment Audits. The ZPICs around the country are actively conducting postpayment audits of blood glucose test suppliers and lancets submitted to Medicare for payment by DME suppliers. These audits typically involve the review of an alleged “statistically relevant sample” of the claims submitted and paid by Medicare over the course of one to three years. The CMS contractors then extrapolate from the sample to determine a projected overpayment. Providers challenging an overpayment may avail themselves of the administrative appeals process, but such an endeavor can take from 18 months to 2 years to reach the administrative law judge level of appeal.

Suspension Actions. In cases where a ZPIC believes that a credible allegation of fraud exists, the contractor may recommend to the CMS that a participating provider or DME supplier should be placed on suspension. When this occurs, a physician provider or DME supplier may still provide services to Medicare beneficiaries. However, any monies that they are eligible to receive will be held by the MAC (in the case of a physician) or by a DME MAC (in the case of a DME supplier) until a post payment audit can be conducted. As with a prepayment review, there is no administrative appeal process to challenge a suspension action. Although a provider or supplier may file a “rebuttal” statement, they are rarely granted. Suspension actions typically last a minimum of six months and are often in effect for a year or more. Any monies held by the CMS contractor will then be applied to any alleged overpayment. If a provider or supplier disagrees with the alleged overpayment, it can avail itself of the administrative appeals process. More often than not, a suspension action will lead to the bankruptcy and closure of a provider’s or DME supplier’s business. Few organizations with a significant Medicare patient load can remain in business for six months or more without receiving Medicare reimbursement for the services or supplies it has rendered to Medicare beneficiaries.

Medicare Number Revocation. Revocation actions can arise in a number of ways. Two reasons frequently cited for revoking a provider’s Medicare number are (1) failure to cooperate during a site visit and (2) failure to provide Medicare with a legitimate office address. As a participating provider or DME supplier, you have an obligation to cooperate with the ZPIC’s review. Should you fail to cooperate, a ZPIC can recommend to the CMS that your Medicare number be revoked. This is a very real threat and should not be discounted. This becomes even more complicated if the ZPIC’s representatives go beyond mere claims-related questions and appear to be seeking information that could subject you (in your individual capacity) to possible civil and/or criminal liability. While you must adhere with your obligations as a participating provider or supplier in the Medicare, you should still consult with your attorney to help ensure that your personal interests are properly protected. Similarly, you have an obligation to advise the government (and its contractors) if you move the location of your office. The ZPICs and other contractors conducting due diligence are routinely checking to ensure that participating providers and DME suppliers are operating legitimate, bona fide businesses. Should they travel to a listed address and find that you are not operating in that location, they will immediately notify the CMS so that your number can be revoked and the Medicare Trust Fund can be protected.

Civil Enforcement

While most remedial actions taken against a Medicare provider or supplier are administrative in nature, in certain instances, the government may determine that the conduct at issue warrants a more serious response. In such cases, the government may choose to pursue civil remedies against an offender. Potential civil remedies may take many forms, including but not limited to (1) injunctive relief; (2) an action against a provider or supplier for common law fraud, unjust enrichment, or payment by mistake; or (3) an action under the civil False Claims Act.

Civil False Claims Act (31 U.S.C. § § 3729-3733)16

The False Claims Act is the primary civil enforcement tool utilized by federal prosecutors when pursuing allegations of civil health care fraud. Sometimes referred to as Lincoln’s Law, the False Claims Act was first passed in 1863 in an effort to discourage and prevent war profiteering. Among its provisions were measures intended to encourage the disclosure of fraud. Under the qui tam (also commonly referred to as “whistleblower”) provisions of the statute, a private person (often referred to as a “relator”) can bring an False Claims Act lawsuit on behalf of, and in the name of, the United States. If a recovery is made, a relator may be eligible for a share of any monies recovered by the government.17 The federal False Claims Act imposes civil penalties and damages against a violator under the circumstances in Table 2.

Table 2.

Overview of the False Claims Act, (31 U.S.C. §§ 3729-3733)16

Sec. 3729. False Claims

|

Damages and Penalties under the False Claims Act

A person found to have violated this statute is liable for civil penalties in an amount between $5500 and not more than $11,000 per false claim, as well as up to three times the amount of damages sustained by the government.

Examples of Possible Civil Liability

As a careful review of recent enforcement efforts will show, the government exercises a wide degree of discretion when deciding whether to pursue allegations of wrongdoing as a mere overpayment, under the civil False Claims Act or, if the evidence is sufficiently compelling, under one of various criminal statutes. There are a number of factors considered by law enforcement when deciding whether to pursue a case through one, two, or even all three avenues of redress (this is commonly referred to as “parallel proceedings”). Actions that may lead to liability under the civil False Claims Act include, but are not limited to the following:

Ordering and/or billing for DME supplies that are not medically necessary. Treating physicians ordering blood glucose testing supplies for patients must ensure that their orders are reflective of a patient’s clinical needs and that any supplies ordered are medically necessary for the care and treatment of the patient. It is important to remember that, under the False Claims Act, if a person knowingly submits or causes a false claim to be submitted to the government for payment, the conduct may constitute a violation of the statute.

Consignment closets could subject a provider to liability under the False Claims Act. In today’s hyper-regulated health care environment, it is essential to keep in mind that any business relationship entered into between a treating physician and a DME supplier should be carefully vetted with the physician’s health care attorney prior to moving forward. One common, potentially problematic practice involves the rental of “consignment closets” from a physician by DME suppliers. When a consignment closet is rented, a DME supplier is allowed to maintain DME supplies and devices on site, in a physician’s office. If properly handled, a consignment closet can both greatly increase patient compliance and provide an opportunity for educating a patient regarding the use of a particular device or supplies before the patient leaves the physician’s office. Typically, the DME supplier would handle billing for supplies distributed from the closet. Problems may arise in a number of different ways. One common concern is that patients may be pressured to buy a device or supplies at their physician’s office rather than from an outside supplier. Depending on the facts, the business relationship between the physician and the DME supplier could conceivably run afoul of the False Claims Act, Stark laws, and/or the federal Anti-Kickback Statute. Under Stark, physicians are prohibited from making referrals of designated health services to an entity in which they have a financial interest. Under the Anti-Kickback Statute, it is illegal to knowingly and willfully offer, pay, solicit, or receive something of value to induce referrals of items or services covered by Medicare or other federal health benefits programs.

Durable medical equipment suppliers who deliver and bill Medicare for supplies that are not supported by an appropriate medical order and/or may not be medically necessary may be liable under the False Claims Act. Durable medical equipment suppliers of blood glucose strips and lancets must exercise caution when filling an order and delivering supplies to Medicare beneficiaries. Does the current order for DME supplies cover the amount of blood glucose test strips that are being delivered and billed to Medicare? If the quantity of test strips would be considered a high-utilization claim, has the DME supplier obtained medical documentation from the treating physician that supports the medical necessity of this frequency of testing? It is imperative that treating physicians and DME suppliers alike regularly review and consider the utilization quantities set out in their applicable LCD. Durable medical equipment suppliers found to have shipped and billed high-utilization amounts of testing supplies to patients that are subsequently found to medically unnecessary may find themselves liable for the cost of these supplies, despite the fact that they were merely following the treating physician’s order. Medicare auditors have held DME suppliers liable if the medical necessity of a high-utilization claim cannot be supported by the supplier when audited.

Blood glucose test strips and lancets must be intended for sale and used in the United States. The domestic sale of test strips intended for sale abroad is prohibited and can lead to liability under the False Claims Act. Depending on the facts, it could conceivably also lead to criminal liability. Domestic manufacturers of blood glucose test strips intended for sale and use in this country take extraordinary steps to help ensure that their products fully comply with all laws, rules, and regulations enforced by the Food and Drug Administration. As set out here, a number of domestic manufacturers produce test strips both in the United States and abroad that are not intended for use or sale in this country. Durable medical equipment suppliers who import or otherwise divert these test strips for sale in the United States may run afoul of a wide number of criminal and/or civil statutes, including the False Claims Act.

Manufacturers take considerable care to ensure that blood glucose test strip package inserts are clear and easy to understand by patients. Manufacturers also annotate each package (typically containing 50 or 100 test strips) with important information needed to assist in calibrating a patient’s test meter. Test strip boxes also reflect a “lot number” that is unique and can be used to determine where and when the strips were manufactured. This information is invaluable if a recall of defective or substandard test strips is needed. With this information, both the manufacturer and the government can quickly notify patients of potential quality problems.

Importantly, literally all testing supply manufacturers employ staff who serve as “secret shoppers.” These individuals are responsible for visiting retail outlets where blood glucose test strips and lancets are sold. These secret shoppers purchase samples of the blood glucose test strip boxes for a variety of reasons. First, it lets the manufacturer know if the retail establishment is purchasing boxes of test strips directly from the manufacturer, from an authorized distributor, or from an unauthorized party. Small pharmacies and other retailers may seek to purchase extra boxes of low-priced test strips from unauthorized sellers on the Internet, from an online auction company, or from a retail distributor who is essentially selling the boxes on a wholesale basis to another retailer, in contravention of their contract with the manufacturer.

Blood glucose test strips purchased and imported from overseas for sale and use in the United States can often be bought on the “gray market” at a mere fraction of the cost of legitimately purchased domestic test strips. Moreover, test strips imported into the United States may not have been stored or transported in the proper manufacturer’s recommended temperature and/or humidity-controlled environments. Additionally, as with imported pharmaceuticals, appearances may be deceiving. Boxes of test strips that appear to be those of a recognized manufacturer may be counterfeit cheap knock-offs, which are sold in an otherwise authentic-looking package.

In some cases, the seller or the retailer may have taken steps to hide the source of the test strips by altering the lot number or covering the manufacturer’s statement that the strips are not intended for sale in this country. A worst case scenario would include situations where a seller or retailer has obliterated or attempted to change the expiration date printed on the box in an effort to sell expired test strips. Both the federal government and DME manufacturers who learn of illegal diversion will aggressively work to identify any unauthorized sellers and/or distributors who are involved in the improper distribution and sale of these altered test strips.

Similarly, the illegal diversion of blood glucose test strips manufactured in the United States that are intended for sale and use overseas may also constitute an actionable civil violation. In many instances, these test strips are manufactured to the standards of the country where their sale is intended to take place. If these test strips are improperly diverted for sale in the United States, sellers may attempt to disguise that fact by attempting to remove the disclaimer placed on the package by the manufacturer.

Criminal Enforcement

In some instances, the government may determine that neither administrative nor civil enforcement is sufficient to address the egregious nature of a physician’s or supplier’s improper conduct. In such instances, the government may choose to pursue one or more criminal enforcement remedies at its disposal, including the following:

Misbranding DME Supplies. In one case,18 a nationally known manufacturer found that a batch of its test strips was defective and required recall. During this time period, the manufacturer also pulled boxes of test strips that appeared to have been damaged during shipment, along with those whose expiration dates were quickly approaching (or had already passed). The manufacturer subsequently contracted with an outside company to destroy these defective, damaged, and/or expired test strips. As the manufacturer would soon learn, the company failed to destroy the test strips. Instead, the company arranged to have these defective, damaged, and/or expired boxes of test strips sold on an Internet auction shopping Web site. It was later estimated that approximately 100 people bought the recalled test strips. One can only imagine the manufacturer’s reaction when it learned that the company it had paid to destroy these testing supplies was instead selling them over the Internet. Consequently, the purchasers of the test strips were also surprised—none of them had been told that these strips had been pulled from sale by the manufacturer. In this particular case, the outside company that failed to destroy the damaged or expired test strips was criminally prosecuted for (1) introducing misbranded medical devices into interstate commerce, a violation of 21 U.S.C. § 331, and (2) wire fraud, a violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1343.19

Future Enforcement Efforts

Each year, the HHS OIG issues an annual work plan for the upcoming fiscal year, which details specific areas of concern and provides insights into the areas the HHS OIG intends to investigate. As set out here, the HHS OIG’s fiscal year 2013 work plan (issued on October 2, 2012) includes five specific areas related to diabetes testing supplies that will be addressed over the course of fiscal year 2013.20 These five areas are outlined in Table 3.

Table 3.

Areas of Concern Identified in the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General’s 2013 Annual Work Plan

|

Recommendations for Physicians and Durable Medical Equipment Suppliers

The government has repeatedly expressed its concern regarding the medical necessity, ordering, supply, billing, and coding of blood glucose test strips and lancets to the Medicare program. It is essential that treating/ordering physicians and DME suppliers alike remain knowledgeable of the medical necessity, documentation, and coverage requirements set out in applicable NCD, LCD, and Medicare benefit policy manual provisions related to these items. There are a number of steps that can be taken to help reduce a provider’s/supplier’s potential liability. These include, but are not limited to, the following:

First and foremost, develop and implement an effective Compliance Plan. Importantly, “one size does not fit all.” Providers and suppliers should develop an individualized plan that recognizes both general and entity-specific risks to be addressed in an effort to fully comply with applicable laws and regulations.

Conduct a “gap analysis” to determine whether your current medical necessity, documentation, and coverage practices fully meet existing NCD, LCD, and Medicare benefit policy manual requirements. If not, take remedial steps to repay any overpayment that may exist and ensure that future billings are compliant.

Examine your documentation with a critical eye. If your records are audited, will an independent third party (such as a ZPIC) find that your assessment and documentation practices are compliant? If not, what additional steps can be taken to better document the services at issue?

Take audits seriously. Reviews and audits by ZPICs are serious business. Do not ignore requests for information and promptly respond (through counsel) to significant billing inquiries.

Keep accurate records. Do not improperly alter medical records. Additionally, think before you write. Does this accurately describe the facts? Avoid hyperbole and exaggeration. Do not speculate.

Conduct periodic internal audits. How often have you sampled postpayment claims to determine if they have been properly coded and billed?

Train your staff to identify and report any noncompliant practices. If you have reason to believe that anyone is engaging in practices that could violate one or more statutory requirements or could lead to the submission of a false or misleading claim, you should immediately report the practice to your entity’s compliance officer.

Do not ignore an overpayment. Providers and suppliers have an obligation to report and repay a Medicare overpayment within 60 days of its identification. Our mothers taught us a life-long lesson that continues to be true: “If it doesn’t belong to you, give it back.”

Appoint someone in your organization to serve as “compliance officer.” Compliance does not just happen; it takes an active effort to help ensure that your staff (and your organization as a whole) fully understands their responsibilities and their role in the compliance process.

Diligently work to instill an ethos in your organization that encourages everyone on your staff, both professional and nonprofessional, to comply with applicable laws, rules, and regulations. The honor code utilized by U.S. Military Academy at West Point says it all. Essentially, their honor code provides, “We do not lie, cheat, steal, or tolerate those who do.”

We encourage you to adopt this as the honor code for your practice or company.

Acknowledgments

Robert W. Liles, M.S., M.B.A., J.D., is managing partner at Liles Parker, a Washington DC-based health law firm with offices in Washington DC; Houston, TX; McAllen, TX; and Baton Rouge, LA. Liles Parker attorneys represent physicians and other providers/suppliers around the country in connection with health care audits, investigations, compliance matters, and transactional projects.

Glossary

- (CMS)

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- (DME)

durable medical equipment

- (HHS)

Health and Human Services

- (LCD)

local coverage determination

- (MAC)

Medicare administrative contractor

- (NCD)

national coverage determination

- (OIG)

Office of Inspector General

- (ZPIC)

zone program integrity contractors

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; Office of the Actuary. Brief summaries of Medicare and Medicaid. http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/MedicareProgramRatesStats/Downloads/MedicareMedicaidSummaries2011.pdf.

- 2. The Social Security Act, Chapter 7, Subchapter XVIII, 42 U.S.C.A. §§ 1395-1395kkk-1 (1965).

- 3. The Social Security Act, Chapter 7, Subchapter XIX, 42 U.S.C.A. §§ 1396-1396w-5 (1965).

- 4. Shalala v Guernsey Memorial Hospital, 514 U.S. 87, 96 (1995).

- 5. The Social Security Act, Chapter 7, Subchapter XVIII, 42 U.S.C.A. § 1395y(a)(1)(A) (1965).

- 6.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Quality improvement organization manual, chapter 1 - background and responsibilities, § 1015 - Centers for Medicare and Medicaid services (CMS) role. http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Downloads/qio110c01.pdf.

- 7.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid statistical supplement, table 13.4 - number of Medicaid persons served (beneficiaries), by eligibility group: fiscal years 1975-2009. http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/MedicareMedicaidStatSupp/Medicare-and-Medicaid-Statistical-Supplement-Items/2011Medicaid.html.

- 8.U.S. Government Accountability Office. Medicare recovery audit contracting: lessons learned to address improper payments and improve contractor coordination and oversight. Publication No. GAO-10-864T. http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d10864t.pdf.

- 9.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare benefit policy manual, publication 100-02, chapter 15 § 110.1. http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CFR-2011-title42-vol3/pdf/CFR-2011-title42-vol3-sec414-202.pdf.

- 10.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; Medicare Learning Network (MLN). Medicare coverage of blood glucose monitors and testing supplies. http://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNMattersArticles/downloads/SE1008.pdf.

- 11. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare benefit policy manual, publication 100-03, chapter 1 § 40.2, 2012, http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/ncd103c1_Part1.pdf.

- 12. NHIC Corp. Local coverage determination (LCD) for glucose monitors (L11530). https://www.medicarenhic.com/dme/medical_review/mr_lcds/mr_lcd_current/L11530_2012-11-01_rev_2012-12_PA_2011-07.pdf.

- 13. CGS Administrators LLC. LCD for Glucose Monitors (L11520). http://www.cgsmedicare.com/jc/education/video/MM/BGM_LCD.pdf.

- 14. Noridian. Local coverage determination (LCD) for glucose monitors (L196). https://www.noridianmedicare.com/dme/coverage/docs/lcds/current_lcds/glucose_monitors.htm%3f.

- 15. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Office of Inspector General. Medicare contractors lacked controls to prevent millions in improper payments for high utilization claims for home blood-glucose test strips and lancets. A-09-11-02027. https://oig.hhs.gov/oas/reports/region9/91102027.asp.

- 16. False Claims Act. 31 U.S. code. §§ 3729-3733 et seq. http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/31/3729.

- 17. U.S. Department of Justice; United States Attorneys Office. False Claims Act cases: government intervention in qui tam (whistleblower) suits. http://www.justice.gov/usao/pae/Documents/fcaprocess2.pdf.

- 18. United States v. William Greg Kroa and Nor Am Plastics Recycling, Inc., Northern District of Indiana, Case No. 3:09-CR-0001 RM, LexisNexis.

- 19. WNDU.com; Platt S. Knox CEO pleads guilty to fraud, illegally selling diabetic testing strips. http://www.wndu.com/home/headlines/37185719.html.

- 20.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Office of Inspector General. Office of Inspector General work plan fiscal year 2013. https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/archives/workplan/2013/Work-Plan-2013.pdf.