Abstract

Discussing end-of-life decisions with cancer patients is a crucial skill for physicians. This article reports findings from a pilot study evaluating the effectiveness of a computer-based decision aid for teaching medical students about advance care planning. Second-year medical students at a single medical school were randomized to use a standard advance directive or a computer-based decision aid to help patients with advance care planning. Students' knowledge, skills, and satisfaction were measured by self-report; their performance was rated by patients. 121/133 (91%) of students participated. The Decision-Aid Group (n=60) outperformed the Standard Group (n=61) in terms of students´ knowledge (p<0.01), confidence in helping patients with advance care planning (p<0.01), knowledge of what matters to patients (p=0.05), and satisfaction with their learning experience (p<0.01). Likewise, patients in the Decision Aid Group were more satisfied with the advance care planning method (p<0.01) and with several aspects of student performance. Use of a computer-based decision aid may be an effective way to teach medical students how to discuss advance care planning with cancer patients.

Keywords: Advance directives, Advance care planning, Medical student education, Computer-based instruction

Introduction

There is widespread agreement that patients with cancer ought to plan for their futures and that physicians should help them participate in medical aspects of that planning [1–8]. Advance directives are one concrete mechanism for helping individuals consider, articulate, and document their wishes for future medical care [2, 9–11], and in the USA, legislation exists in all 50 states supporting their use. Despite express expectations that physicians-in-training learn to facilitate advance care planning [12–15], there is no standardized method for teaching the topic in medical schools and little is known about which educational strategies are most effective for achieving this goal [16, 17]. In this pilot study, we sought to evaluate whether an interactive, computer-based decision aid could be an acceptable and effective tool for helping to teach medical students and for providing them a meaningful, practical experience with advance care planning.

Previously, we developed a computer program, Making Your Wishes Known: Planning Your Medical Future, to help individuals clarify and articulate their medical treatment preferences [18]. The computer program is interactive, multimedia, and employs a decision tool based on multi-attribute utility theory [19–22] that facilitates the ranking and rating of people’s priorities for end-of-life decisions. The program uses a question-answer format, along with clinical vignettes and video clips of “professional experts” to help users explore in lesser or greater depth a broad variety of advance care planning related issues. Additionally, it incorporates individuals’ responses to generate a printable copy of an advance directive document that can be placed in the medical record and help guide medical decision-making. Pilot testing of this program has shown that it is acceptable and effective among a variety of demographic groups, including healthy older adults, patients with cancer, and patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [23–25].

Here, we report findings from a pilot investigation into the effectiveness of this program as a teaching tool for medical students at a single midsized medical school. We hypothesized that students who used the program to help older adult patients complete an advance directive would be more knowledgeable, skilled, and satisfied with advance care planning than those who used a standard advance care planning packet. It is not known what constitutes the most effective method for preparing medical students to communicate effectively with patients about end of life decision-making [15, 26, 27]. As such, this study was designed to provide pilot data for a broader examination into whether a computer-based teaching tool can provide an effective, standardized educational experience for physicians-in-training.

Methods

We used a prospective, randomized controlled design that included all second-year medical students enrolled in a required Ethics and Professionalism course at Penn State College of Medicine. As part of that course, students learn about advance care planning and are required to help an older adult (hereafter referred to as “patient”) complete an advance directive. Students were randomized to use either our computer-based decision aid (Decision Aid Group) or a state-specific advance care planning packet (Standard Group) to facilitate a discussion about end-of-life wishes and to help their patient complete an advance directive. Prior to the intervention, all students received basic training in advance care planning: several hours of lectures and small group discussion on patient autonomy, informed consent, and doctor-patient communication; articles about the purpose and mechanics of advance directives; and instruction on how to discuss advance directives with patients. Immediately pre-intervention, students completed measures of their demographic characteristics, knowledge of advance care planning, and confidence in assisting patients with advance care planning. Post-intervention, they repeated the knowledge and confidence instruments, and also completed measures of their satisfaction with the advance care planning method and their perceived knowledge of patient’s wishes. Additionally, post-intervention, each patient completed brief demographic measures, an evaluation of student performance, and a measure of global satisfaction similar to that completed by students. All instruments were developed for this project but modified from instruments we have used in prior research. The institutional Human Subjects Protection Office determined that this study met criteria for exempt research (per HHS Federal Regulations Title 45, Part 46.101(b)(1 and 2)); hence, written informed consent was not required from participants. However, all data were rendered unidentifiable, and in our analyses, we only used data from those who agreed to its use in research.

Participants

Students

All 133 second-year medical students enrolled in a mandatory Ethics and Professionalism course in November 2006 were eligible to participate in this study.

Patients

Each “student-participant” recruited a “patient-participant” (from inpatients, outpatients, family members, and acquaintances) who was an English speaker, ≥50 years of age, and able to engage in advance care planning. This age cutoff was chosen to identify that patient population most likely to seek discussion with physicians about advance care planning.

Outcome Measures

Students’ knowledge was assessed using a 17-item true/false and multiple-choice test adapted from the authors’ related research studies, developed after a thorough literature review, and pilot testing for face and content validity.

Students’ skill was measured with a self-assessment instrument (five-point scale) on which students rated their confidence in assisting the patient with advance care planning (four items) and their perceived knowledge of patient wishes (four items).

Students’ satisfaction was assessed using (1) a measure of global satisfaction (one item, 10-point scale) and (2) satisfaction with particular aspects of the advance care planning process (four items, five-point scale).

Patients’ evaluation of the student’s performance was assessed using a 12-item instrument that addressed students’ communication skills, helpfulness, and perceived understanding of their (the patient’s) wishes.

Patients’ satisfaction with the advance care planning method was assessed via the same measure of global satisfaction used by students (one item, 10-point scale).

Prior to implementation, all instruments were pilot tested with a group of physicians, psychologists, medical students, and patients for clarity and relevance as well as content and face validity. Patient completion of study questionnaires was voluntary.

Intervention

The Decision Aid Group participants used Making Your Wishes Known, Planning Your Medical Future, an interactive, computer-based program for advance care planning that was developed by the investigators and an interdisciplinary team of clinicians and researchers. This multimedia decision aid helps prepare users to engage in advance care planning discussions by providing education material and exercises designed to (1) help users clarify and prioritize their values; (2) explain end-of-life conditions (stroke, dementia, terminal illness, and coma) and medical treatments (CPR, mechanical ventilation, dialysis, feeding tube); (3) help users choose a surrogate decision maker and learn how to discuss their wishes with this spokesperson; and (4) translate their wishes and goals into a medical plan in the form of an advance directive. Details of the computer program have been described elsewhere [18, 28], and readers can try it for themselves at: www.makingyourwishesknown.com (log in as “test user.”).

The Standard Group participants used an advance care planning packet comprised of Understanding Advance Directives for Health Care: Living Wills and Powers of Attorney in Pennsylvania, an educational brochure and living will form produced by the Pennsylvania Department of Aging [29]. This standard packet provides basic education about advance directives, sections for assigning a surrogate decision-maker and outlining specific end-of-life wishes, along with instructions on how to complete the form. But it does not include values clarification exercises, education about medical conditions/treatments, or a decision support tool for assisting in decision-making.

In both groups, students were given the same task—to introduce the topic of advance care planning to their patient and use their assigned intervention to help patients explore their values, priorities, and understanding of common end-of-life conditions and medical interventions. Additionally, students were asked to elicit from patients the name of their desired spokesperson(s) as well as to gather sufficient information about the patient’s goals and preferences for end-of-life care to complete a formal advance directive. Students were to answer questions as they arose, but no formal time limit was set for the student–patient interaction.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables. Differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups were compared using a two-sample t test for continuous variables and a chi-square test for categorical variables. For post-intervention ordinal outcome data, a Wilcoxon Rank Sum test was used to analyze the differences in mean scores between groups (student and patient satisfaction and patient evaluation of student performance). For outcomes related to student knowledge and student confidence, a linear mixed effects model was used to compare the mean change from baseline to post-intervention between groups. Change from baseline was calculated for each subject by subtracting the baseline measure from the post-intervention measure for each outcome. The model was also adjusted for the baseline measure of the outcome.

Results

All 133 eligible students participated in the advance care planning exercise (i.e., helping a patient complete an advance directive). Of these, 121 students—60 in the Decision Aid Group and 61 in the Standard Group— agreed to have their data used (91% response rate). The students’ mean age was 25 years (range 21–36 years) and 50% were male. The patients’ mean age was 57 years (range 50–83 years) and 42% were male. Additionally, 90% of patients said they owned a computer, and 20% had completed an advance directive previously. There were no significant differences between groups for any demographic variables.

Student Evaluation

Student Knowledge of Advance Care Planning

Despite high baseline levels of knowledge of advance care planning in both groups, students in the Decision Aid Group demonstrated an increase in knowledge (from 84% correct responses to 88%, p<0.01), while students in the Standard Group did not (86% to 85%). Specifically, students in the Decision Aid Group were significantly more likely to provide correct post-intervention answers for the following items: “An advance directive and a living will are exactly the same thing” (87% vs. 52%); and “Over 40% of all cardiac arrest victims survive following administration of CPR” (75% vs. 56%). See Appendix 1 for complete knowledge test.

Student Skill

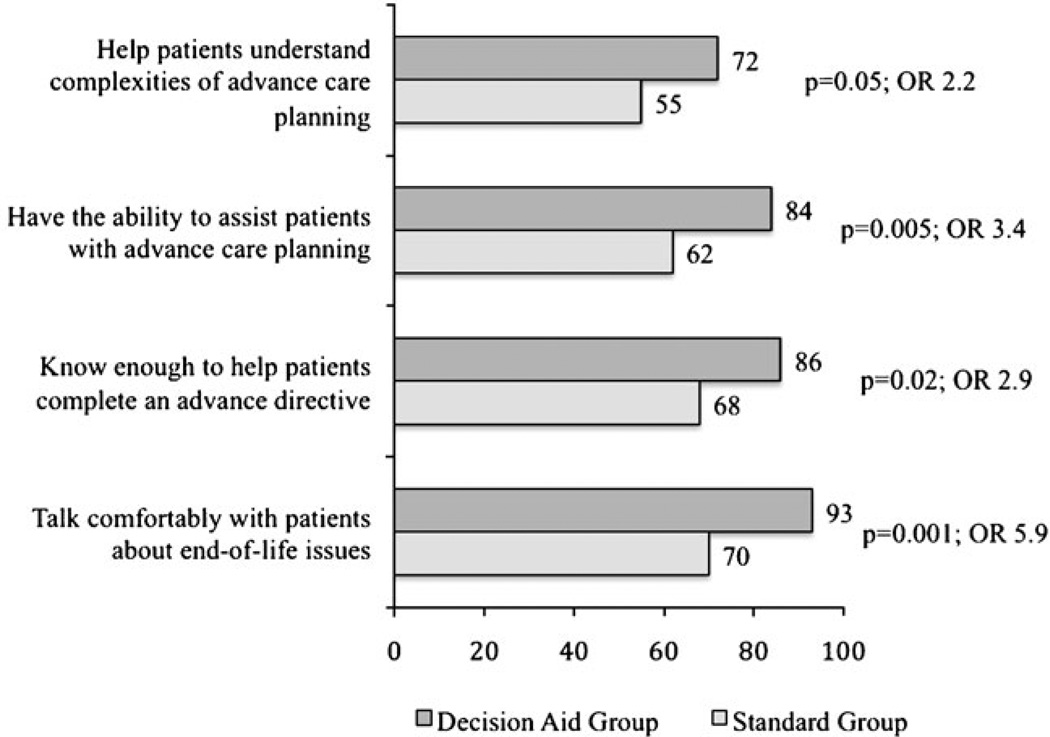

Student Confidence in Engaging in Advance Care Planning Prior to the intervention, students in the two groups reported similar confidence for: (1) knowing enough to help patients complete an advance directive; (2) talking comfortably with patients about end-of-life issues; (3) helping patients understand the complexities of advance care planning; and (4) having the ability to assist patients with advance care planning. Post-intervention, student confidence increased significantly (p<0.01) in both groups, but the increase was significantly greater in the Decision Aid Group (p<0.01) across all domains. Figure 1 shows the percentage of students in each group who rated themselves post-intervention as “moderately” or “very” confident at each task.

Fig. 1.

Percent of students who rated themselves (post-intervention) as “Moderately Confident” or “Very Confident” to

Student Knowledge of Wishes Students’ perceived knowledge of patients’ wishes did not differ between groups. However, for one of the four items (“I feel I know what matters most to this person regarding his/her end-of-life wishes”) scores were significantly greater in the Decision Aid Group (4.4 vs. 4.1, p=0.05, where 1=less knowledgeable, 5=more knowledgeable).

Student Satisfaction

Students’ global satisfaction with the advance care planning method was significantly greater in the Decision-Aid Group than in the Standard Group (7.8 vs. 5.6, p<0.01, where 1=not at all satisfied, 10=extremely satisfied). In particular, students were more satisfied with how the decision aid helped them in each of the domains we measured: (1) exploring the patient’s values; (2) documenting the patient’s wishes; (3) learning about the patient’s wishes; and (4) discussing end-of-life care with patients (Table 1).

Table 1.

Post-intervention student satisfaction with the advance care planning method

| Item | Decision aid group (n=60) |

Standard group (n=56) |

P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| How satisfied were you with the [advance care planning method] in terms of: Mean (95% C.I.) (1=very dissatisfied, 5=very satisfied) | |||

| Helping the patient explore his/her values | 4.1 (3.9, 4.3) | 3.2 (2.9, 3.5) | <0.01 |

| Helping the patient to thoroughly document his/her wishes | 4.0 (3.8, 4.2) | 3.1 (2.8, 3.4) | <0.01 |

| Helping you learn about the patient’s wishes | 4.2 (4.1, 4.4) | 3.6 (3.3, 3.9) | <0.01 |

| Helping you discuss end-of-life care with the patient | 4.2 (4.0, 4.4) | 3.5 (3.3, 3.8) | <0.01 |

P values from a Wilcoxon Rank Sum test

Patient Evaluation

Patient Evaluation of Student Performance

Responding to the question “How satisfied were you with the medical student who helped you complete an advance directive?” patients were significantly more satisfied with students in the Decision Aid Group (9.7 vs. 8.8, p<0.01, where 1=not at all satisfied, 10=extremely satisfied). In response to 11 task-specific questions, patients rated student performance as significantly better for those in the Decision Aid Group with regard to: amount of time spent with patients; explaining things in an understandable way; being knowledgeable about advance care planning; meeting patients’ need for factual information; and tailoring the discussion to patients’ specific concerns. In no instance was performance rated more favorably in the Standard Group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Post-intervention patient evaluation of student performance

| Item | Decision aid group (n=60) | Standard group (n=61) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (95% C.I.) (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree) |

|||

| Student took enough time with me | 4.7 (4.6, 4.9) | 4.5 (4.3, 4.7) | 0.01 |

| Student explained things in a way that I could understand |

4.7 (4.5, 4.9) | 4.5 (4.3, 4.7) | 0.01 |

| Student was knowledgeable about advance care planning |

4.5 (4.3, 4.7) | 4.3 (4.1, 4.4) | 0.02 |

| Student was helpful to me as I completed my advance directive |

4.7 (4.5, 4.9) | 4.6 (4.4, 4.7) | 0.08 |

| I felt willing to share my values and preferences with the student |

4.7 (4.5, 4.9) | 4.6 (4.5, 4.7) | 0.17 |

| Student seemed interested in my concerns | 4.7 (4.5, 4.9) | 4.6 (4.5, 4.8) | 0.32 |

| (1=excellent, 4 =poor) | |||

| How well the student met your need for factual information |

1.3 (1.1, 1.4) | 1.6 (1.4, 1.8) | 0.01 |

| How well the student tailored the discussion to your specific concern |

1.3 (1.1, 1.4) | 1.5 (1.3, 1.7) | 0.05 |

| How well the student understood what was most Important to you |

1.2 (1.1, 1.3) | 1.4 (1.2, 1.6) | 0.11 |

| How well the student addressed emotional concerns | 1.3 (1.1, 1.4) | 1.5 (1.3, 1.7) | 0.12 |

| Level of rapport the student established with you | 1.1 (1.0, 1.2) | 1.3 (1.1, 1.4) | 0.15 |

P values from a Wilcoxon Rank Sum test

Patient Satisfaction with Method of Advance Care Planning

Finally, as with the students, patients’ global satisfaction with the advance care planning method was significantly greater in the Decision-Aid Group (8.1 vs. 6.6, p<0.01, where 1=not at all satisfied, 10=extremely satisfied).

Discussion

In this pilot study, we found that as a teaching tool for medical students, a computer-based program significantly outperformed standard advance care planning materials across virtually all parameters measured. Commonly, medical students learn to communicate with patients about end-of-life issues in ways that are haphazard and unstructured, be it trial and error, observing others, or using some version of a standard living will form as their guide. Although the computer program was conceived primarily as a method for helping patients with advance care planning, this study suggests that it may also be an effective tool for helping medical students learn how to have meaningful discussions with patients about advance care planning.

It is particularly promising that students’ who used this program expressed greater confidence not only in helping patients understand the complexities of advance care planning but also in implementing what they have learned—including creating a formal advance directive. Not surprisingly, these same students also reported greater confidence in their ability to talk comfortably with patients about end-of-life issues.

Because students in each group had received in-depth background materials related to advance care planning prior to the intervention, the incremental improvement in knowledge that we found was quite modest. Even so, students in the Decision Aid Group demonstrated a statistically significant increase in knowledge compared with the Standard Group. We expect that in a broader study of medical colleges this increase might be even more pronounced insofar as advance care planning-related education may not be as fully developed as at our institution.

The high levels of both student and patient satisfaction in the Decision Aid Group are encouraging in several respects. First, it shows that this tool can provide students a positive first experience with advance care planning. Second, students can see first-hand that patients appreciate the opportunity to discuss advance care planning with a healthcare provider. Third, as a structured learning exercise, the program can reinforce for students that discussing advance care planning is a valuable way to engage with patients.

Another positive finding was that students in the Decision Aid Group reported significantly greater understanding of “what mattered most” to their patient regarding his/her end-of-life wishes. That said, we did not find that the computer program out-performed standard approaches to advance care planning in terms of either (1) students’ perceived knowledge of what medical treatments their patient would want if s/he were unable to make medical decisions or (2) students feeling they had enough information about the patient’s wishes to make appropriate medical decisions on his/her behalf. This negative result may reflect that participants were second-year medical students with little to no experience making actual medical decisions.

The present findings are encouraging for the potential use of Making Your Wishes Known by other medical institutions. In our own curriculum, we historically have assigned medical students the task of using standard advance care planning materials to help a patient complete an advance directive. This assignment has been popular and well received over the years, and students have reported that it helped prepare them for having such discussions with actual patients. It also helped them recognize the complexity of advance care planning, the difficulty of discussing death and dying, and the emotional challenges entailed. However, we had never systematically evaluated our methods of teaching until this trial. This pilot study suggests that a computer program can outperform standard advance care planning teaching techniques while yielding high satisfaction for both medical students and patients.

Limitations

As a pilot study, the chief limitation of our findings is that the results describe one cohort of medical students at a single academic medical center. Second, selection of patients was determined by the students and was not random; hence, students may have chosen individuals whose skills and interests differed from those in the general population. That said, there is no reason to believe that any such selection bias would systematically favor one group over the other. Third, the study was not blinded, which could affect how the participants responded to the intervention. Fourth, we do not have full information about students’ interactions with their patients, including time spent. While this does not cast doubt on students’ satisfaction with the intervention, it does raise the question whether patients’ satisfaction with students was influenced by their appreciation for the intervention. Fifth, the measures used in the study have not been formally validated. Finally, we rely on subjective self-report for evaluation of student performance, and this may not be the most accurate way to determine teaching effectiveness.

Despite these limitations, these data suggest that use of a computer-based decision aid designed to help patients with advance care planning may be an effective way to teach medical students how to engage patients in conversations about end-of-life issues. We look forward to a national study comparing this intervention with existing teaching modalities for advance care planning, and also invite other medical educators to examine the program at www.makingyourwishesknown.com and consider using it with their own students.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research (1 R21 NR008539), Penn State University Social Science Research Institute, and Penn State University Woodward Endowment for Medical Science Education.

Appendix 1: Advance care planning knowledge

For questions 1–11, mark the single best answer with an x.

- An advance directive is a document that:

-

✓Expresses an individual's medical wishes when that person is unable to speak for him- or herself

-

□Determines who will handle one's financial affairs after death

-

□Describes how one's estate will be distributed upon death

-

□Explains one's rights as a patient Don't know

-

✓

- Advance directives go into effect if and only if an individual:

-

□Gets admitted to the hospital

-

□Has a terminal medical condition

-

✓Can no longer communicate his or her health care decisions

-

□Can't make up his or her mind about a health care decision

-

□Don't know

-

□

- A Health Care Power of Attorney:

-

□Is the designation of another person to make financial decisions when the patient is too sick to make them

-

✓Is the designation of another person to make medical decisions when the patient is too sick to make them

-

□Is a person who is paid to write an individual's last will and testament

-

□Is a person who represents the hospital when end-of-life decisions must be made

-

□Don't know

-

□

- In general, the best person to serve as an individual’s health care surrogate is the person who:

-

□Has the most medical knowledge

-

□Has the most legal knowledge

-

✓Is best able to represent the individual's views

-

□Has known the individual the longest

-

□Don't know

-

□

- Hospice and palliative care are:

-

✓Approaches to caring for people near death that focus on controlling discomfort and addressing emotional and spiritual needs

-

□Programs where terminally ill patients agree to receive no additional medical treatment

-

□Medical facilities that separate and treat patients who have highly infectious diseases

-

□Specialty services that provide medical interventions to help patients end their lives

-

□Don't know

-

✓

- Living wills:

-

□Do not have to follow any formal guidelines

-

□Must be approved by a hospital’s legal counsel before they go into effect

-

□Must be prepared by a lawyer

-

✓Have no legal standing so long as the patient has decision-making capacity

-

□Are not valid without the explicit approval of one’s designated surrogate decision-maker

-

□

- A Health Care Power of Attorney:

-

□Must be a family member

-

□Is the title given to anyone who makes decisions on another person's behalf

-

✓Has the authority to make health care decisions only when an individual is incapacitated

-

□Is also entitled to make financial decisions on an individual's behalf

-

□Cannot make decisions that override written advance directives

-

□

- Which of the following statements regarding advance directives is false?

-

□Most adults do not have advance directives

-

□To be valid, an advance directive must be completed by a person who is competent to make his or her own decisions

-

✓Having an advance directive ensures that physicians will follow an individual's wishes

-

□Advance directives often do not anticipate the exact medical conditions under which they may be needed

-

□In creating an advance directive, the process of discussing one's wishes with friends and family may be as useful as the written advance directive itself

-

□

- Which of the following characteristics of a potential surrogate decision-maker is least important?

-

□Being trustworthy

-

□Understanding the patient's values and preferences regarding end-of-life care

-

✓Being knowledgeable about legal issues

-

□Having the judgment and strength to make difficult decisions at emotionally trying times

-

□Being able to accurately interpret a patient's wishes

-

□

- Of the following, which is least important for a patient to do regarding advance care planning?

-

□Discuss their values and wishes regarding end-of-life care with trusted family members and friends

-

□Create an advance directive that explains their views

-

□Provide their physician(s) with the advance directive and discuss their values and wishes

-

✓Use a state-specific living will form

-

□Name a Health Care Power of Attorney

-

□

-

Which of the following statements about advance directives is false?

-

□Advance directives are not always available when needed

-

✓Advance directives must follow a specific legal format

-

□There is no guarantee that a written advance directive will be followed

-

□Disputes may arise regarding how an advance directive should be interpreted

-

□Written advance directives often fail to anticipate the exact conditions under which decisions need to be made

For questions 12–17, please indicate whether you think each item is True or False.

-

□

- If an individual has decision-making capacity and can still speak for him- or herself, an advance directive does NOT determine which medical treatments they will receive.

-

✓True

-

□False

-

✓

- An advance directive and a living will are exactly the same thing.

-

□True

-

✓False

-

□

- A doctor cannot implement a patient's wishes unless the patient has completed an advance directive.

-

□True

-

✓False

-

□

- Written advance directives may include non-medical end-of-life preferences

-

✓True

-

□False

-

✓

- Over 40% of all cardiac arrest victims survive following administration of CPR (cardio-pulmonary resuscitation)

-

□True

-

✓False

-

□

- More than 50% of U.S. adults have completed written advance directives

-

□True

-

✓False

-

□

Footnotes

Author Disclosure Statement The authors have intellectual property and copyright interests for the decision aid used for this study, and anticipate making the decision aid available through Penn State University as a marketed product (but with no-cost licensure for use with healthcare students).

Presented as a research abstract at the following professional meetings: Society for Medical Decision Making Annual Meeting, Philadelphia, PA., October 19, 2008; American Society of Bioethics and Humanities Annual Meeting, Cleveland, OH, October 23, 2008; and Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting, Pittsburgh, PA, April, 2008.

Contributor Information

Michael J. Green, Departments of Humanities and Internal Medicine, Penn State College of Medicine, C1743, 500 University Drive, Hershey, PA 17033, USA mjg15@psu.edu

Benjamin H. Levi, Departments of Humanities and Pediatrics, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, PA, USA

References

- 1.Doukas DJ, Brody H. After the Cruzan case: the primary care physician and the use of advance directives. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1992;5:201–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lo B, Steinbrook R. Resuscitating advance directives. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1501–1506. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.14.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miles S, Koepp R, Weber E. Advance end-of-life treatment planning. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1062–1068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moskop JC. Improving care at the end of life: how advance care planning can help. Palliat Support Care. 2004;2:191–197. doi: 10.1017/s1478951504040258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mullan PB, Weissman DE, Ambuel B, von Gunten C. End-of-life care education in internal medicine residency programs: an interinstitutional study. J Palliat Med. 2002;5:487–496. doi: 10.1089/109662102760269724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prendergast TJ. Advance care planning: pitfalls, progress, promise. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:N34–N39. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200102001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwartz CE, Merriman MP, Reed GW, Hammes BJ. Measuring patient treatment preferences in end-of-life care research: applications for advance care planning interventions and response shift research. J Palliat Med. 2004;7:233–245. doi: 10.1089/109662104773709350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tulsky JA. Beyond advance directives: importance of communication skills at the end of life. JAMA. 2005;294:359–365. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.3.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emanuel LL, Emanuel EJ. The Medical Directive. A new comprehensive advance care document. JAMA. 1989;261:3288–3293. doi: 10.1001/jama.261.22.3288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McAuley WJ, Buchanan RJ, Travis SS, Wang S, Kim M. Recent trends in advance directives at nursing home admission and one year after admission. Gerontologist. 2006;46:377–381. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.3.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quill TE. Terri Schiavo–a tragedy compounded. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1630–1633. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barnard D, Quill T, Hafferty FW, Arnold R, Plumb J, Bulger R, Field M. Preparing the ground: contributions of the preclinical years to medical education for care near the end of life. Working Group on the Pre-clinical Years of the National Consensus Conference on Medical Education for Care Near the End of Life. Acad Med. 1999;74:499–505. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199905000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schonwetter RS, Robinson BE. Educational objectives for medical training in the care of the terminally ill. Acad Med. 1994;69:688–690. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199408000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sullivan AM, Lakoma MD, Billings JA, Peters AS, Block SD, Faculty PC. Teaching and learning end-of-life care: evaluation of a faculty development program in palliative care. Acad Med. 2005;80:657–668. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200507000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sullivan AM, Lakoma MD, Block SD. The status of medical education in end-of-life care: a national report. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:685–695. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21215.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Block SD. Medical education in end-of-life care: the status of reform. J Palliat Med. 2002;5:243–248. doi: 10.1089/109662102753641214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buss MK, Marx ES, Sulmasy DP. The preparedness of students to discuss end-of-life issues with patients. Acad Med. 1998;73:418–422. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199804000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green MJ, Levi BH. Development of an interactive computer program for advance care planning. Health Expect. 2009;12:60–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2008.00517.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jain NL, Kahn MG. Using knowledge maintenance for preference assessment. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1995;1995:263–269. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Torrance GW, Boyle MH, Horwood SP. Application of multi-attribute utility theory to measure social preferences for health states. Oper Res. 1982;30:1043–1069. doi: 10.1287/opre.30.6.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Torrance GW, Feeny DH, Furlong WJ, Barr RD, Zhang Y, Wang Q. Multiattribute utility function for a comprehensive health status classification system. Health Utilities Index Mark 2. Med Care. 1996;34:702–722. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199607000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Torrance GW, Furlong W, Feeny D, Boyle M. Multi-attribute preference functions. Health Utilities Index. Pharmacoeconomics. 1995;7:503–520. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199507060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farace E, Marupudi N, Green MJ, Levi BH, Sheehan JM. Las Vegas, NV. The Society for NeuroOncology 13th Annual Scientific Meeting.2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green MJ, Levi BH, Farace E. Pittsburgh, PA. Society for Medical Decision Making 29th Annual Meeting.2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green MJ, Levi BH, Farace E. Bethesda, MD. American Society of Preventive Oncology Annual Meeting.2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gallagher TH, Pantilat SZ, Lo B, Papadakis MA. Teaching medical students to discuss advance directives: a standardized patient curriculum. Teach Learn Med. 1999;11:142–147. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lorin S, Rho L, Wisnivesky JP, Nierman DM. Improving medical student intensive care unit communication skills: A novel educational initiative using standardized family members. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2386–2391. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000230239.04781.BD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levi BH, Green MJ. Too Soon to Give Up: Re-examining the Value of Advance Directives. Am J Bioeth. 2010;10:3–22. doi: 10.1080/15265161003599691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pennsylvania Department of Aging. [Accessess 19 May];Understanding Advance Directives for Health Care: Living Wills and Powers of Attorney in Pennsylvania. 2010 http://www.portal.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt?open=514&objID=616385&mode=2.