Abstract

The tumour suppressor ARF is specifically required for p53 activation under oncogenic stress1–6. Recent studies showed that p53 activation mediated by ARF, but not that induced by DNA damage, acts as a major protection against tumorigenesis in vivo under certain biological settings7,8, suggesting that the ARF–p53 axis has more fundamental functions in tumour suppression than originally thought. Because ARF is a very stable protein in most human cell lines, it has been widely assumed that ARF induction is mediated mainly at the transcriptional level and that activation of the ARF–p53 pathway by oncogenes is a much slower and largely irreversible process by comparison with p53 activation after DNA damage. Here we report that ARF is very unstable in normal human cells but that its degradation is inhibited in cancerous cells. Through biochemical purification, we identified a specific ubiquitin ligase for ARF and named it ULF. ULF interacts with ARF both in vitro and in vivo and promotes the lysine-independent ubiquitylation and degradation of ARF. ULF knockdown stabilizes ARF in normal human cells, triggering ARF-dependent, p53-mediated growth arrest. Moreover, nucleophosmin (NPM) and c-Myc, both of which are commonly overexpressed in cancer cells, are capable of abrogating ULF-mediated ARF ubiquitylation through distinct mechanisms, and thereby promote ARF stabilization in cancer cells. These findings reveal the dynamic feature of the ARF–p53 pathway and suggest that transcription-independent mechanisms are critically involved in ARF regulation during responses to oncogenic stress.

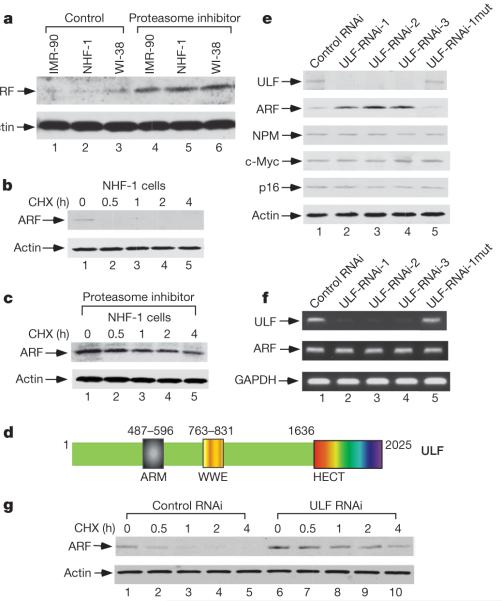

Although recent studies have demonstrated that ARF turnover can occur through ubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation, the identity of the E3 ligase responsible for ARF degradation and its biological significance are still unknown5,9. In accord with published results, we found that proteasome-mediated ARF degradation is severely inhibited in most human tumour cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 2). In particular, although the levels of ARF protein are low in the cells of normal human fibroblast cell lines such as NHF-1, IMR90 and WI-38 (Fig. 1a), treatment with a proteasome inhibitor markedly stabilized ARF without affecting the messenger RNA levels (Supplementary Fig. 3) in these cells. Moreover, the half-life of ARF is extremely short in normal human fibroblasts (less than 30 min) (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 4) but increases markedly (to more than 4 h) in the presence of proteasome inhibitors (Fig. 1c). These data suggest that ARF is very unstable in normal human cells but that its degradation is inhibited in cancerous cells.

Figure 1. ULF is identified as a major factor for short half-lives of ARF in normal human fibroblast cells.

a–c, Western blot analysis of cell extracts from normal human fibroblast cells harvested at 0 or 17 h after treatment with proteasome inhibitor (a), at the indicated time points (h) after treatment with cycloheximide (CHX) (b), or after 17 h of treatment with proteasome inhibitor followed by the addition of cycloheximide (c). d, Diagram of the ULF protein showing several signature motifs. e, Lysates of the NHF-1 cells treated with the different RNAi oligonucleotides were analysed by western blotting with the indicated antibodies. ULF-RNAi-1mut, a point mutation form of ULF-RNAi-1. f, Expression of mRNAs encoding ULF and ARF by RT–PCR from the cells in e.g, Inactivation of ULF by siRNA extends the half-life of endogenous ARF protein in NHF-1 cells.

Several studies have shown that both the function and stability of ARF are tightly regulated by NPM (refs 10–17). To elucidate the mechanism of ARF degradation in vivo, we isolated NPM-associated protein complexes from human cells. Mass spectrometric analysis of the NPM protein complexes identified one polypeptide with a potential ubiquitin ligase domain (Supplementary Fig. 5). A fragment of this protein was named as TRIP12 for a binding partner of the thyroid hormone receptor from a yeast two-hybrid screen with undefined function18. We have designated this protein as ULF (ubiquitin ligase for ARF) because the experiments described implicate it in ARF ubiquitylation. In addition to a carboxy-terminal HECT domain that potentially catalyses ubiquitylation, the 2,025-residue ULF protein also contains a centrally located WWE motif and an amino-terminal ARM domain (Armadillo/β-catenin-like repeats) (Fig. 1d).

To determine the physiological function of ULF, we examined whether inactivation of endogenous ULF has any effect on the stability of ARF or NPM. To this end, the normal human fibroblast cell line NHF-1 was transfected with either a ULF-specific (ULF-RNAi-1) or a control short interfering RNA (siRNA). As shown in Fig. 1e, the levels of endogenous ULF polypeptides were severely decreased after three consecutive transfections with ULF-RNAi-1. Although the levels of NPM were unaffected by ULF ablation, ULF knockdown significantly elevated ARF protein levels. As additional controls, the levels of Ink4a/p16 and c-Myc were not affected by the same treatment. To exclude off-target effects, we also treated cells with two additional ULF siRNAs (ULF-RNAi-2 and ULF-RNAi-3) that recognized different regions of the ULF mRNA. Again, the endogenous levels of ARF protein were increased by ULF knockdown although the mRNA levels for ARF remained unchanged (Fig. 1f). Similar results were also obtained in other normal human cell lines such as WI-38 and IMR90 (Supplementary Fig. 6). In addition, the half-life of endogenous ARF was extended from less than 30 min to about 4 h by knockdown of ULF (Fig. 1g). These data demonstrate that ULF is required for ARF degradation in normal human cells.

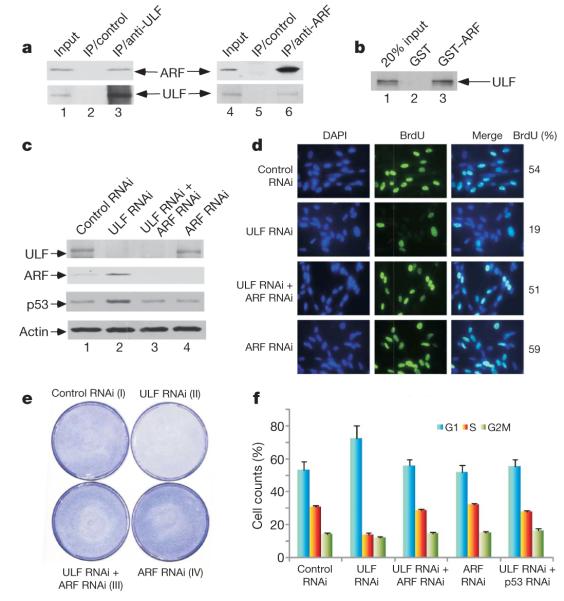

To validate a role for ULF in regulating ARF stability in vivo, we first tested the interaction between endogenous ARF and ULF proteins. To this end, cell extracts from NHF-1 cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-ULF or with control IgG. As shown in Fig. 2a, ARF was detected in the immunoprecipitates obtained with the anti-ULF antiserum but not in those obtained with control IgG. Conversely, endogenous ULF was readily immunoprecipitated with an ARF-specific monoclonal antibody but not with control antibody. We also examined whether ARF can bind ULF in vitro. As shown in Fig. 2b, 35S-labelled ULF strongly bound immobilized glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged ARF but not GST alone. These data demonstrate that ULF interacts with ARF both in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 2. ULF interacts with ARF.

Inactivation of ULF induces ARF-dependent p53 stabilization and cell growth repression in NHF-1 cells a, Co-immunoprecipitation of ARF with ULF or ULF with ARF from NHF-1 cells treated with proteasome inhibitors. IP, immunoprecipitation. b, GST–ARF (lane 3) or GST alone (lane 2) was used in a GST pull-down assay with in vitro translated 35S-labelled ULF. c, Inactivation of ULF by RNAi induces ARF-dependent p53 stabilization. d, NHF-1 cells were labelled and stained with BrdU after RNAi treatment as indicated. e, NHF-1 cells treated with the indicated RNAi oligonucleotides were stained with crystal violet three days after siRNA treatment. f, Inactivation of ULF by RNAi induces G1 arrest in NHF-1 cells. Error bars represent s.d. (n = 3).

To examine the physiological consequence of the ULF–ARF interaction in human cells, we evaluated the role of ULF in regulating the ARF–p53 pathway. For this purpose, normal human fibroblast NHF-1 cells were transfected with either control or ULF-specific siRNAs. As shown in Fig. 2c, RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated knockdown of ULF expression significantly increased the levels of endogenous p53. To ascertain whether the ULF-mediated effect on p53 is dependent on ARF, we tested the consequences of ULF knockdown in the absence of ARF. Indeed, p53 activation was markedly diminished in NHF-1 cells on siRNA-mediated depletion of both ULF and ARF (Fig. 2c), suggesting that the activation of p53 induced by ULF ablation is dependent on ARF. To examine whether ARF induction affects cell growth, we used bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) staining of newly synthesized DNA to monitor cell proliferation. As shown in Fig. 2d, ULF knockdown significantly decreased the fraction of BrdU-positive cells (from 54% to 19%), but this effect was reversed by concomitant knockdown of ARF. Cell proliferation was also visibly inhibited after similar treatment in ULF-knockdown cells (Fig. 2e). Moreover, analysis by fluorescence-activated cell sorting revealed that ULF knockdown induces growth arrest by increasing the proportion of cells in G1 phase (72% versus 55%) and decreasing the proportion of S-phase cells (14% versus 31%) (Fig. 2f). Again, these effects were reversed by the concomitant knockdown of either endogenous ARF or p53 (Fig. 2f). These experiments indicate that inactivation of ULF induces ARF stabilization and triggers an ARF-dependent, p53-mediated arrest of cell growth.

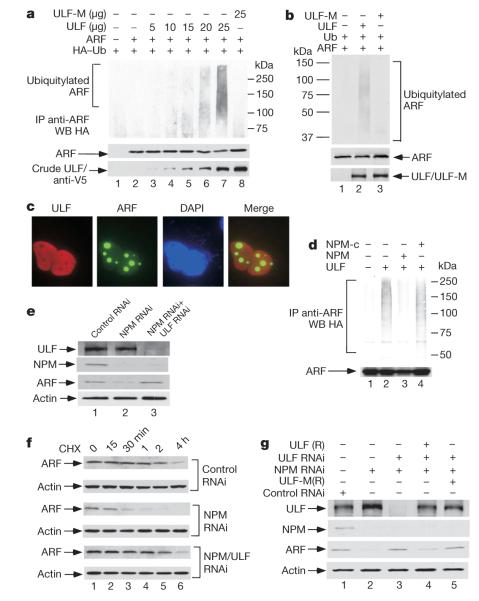

To examine the functional relationship between ARF and ULF, we tested whether ULF induces the ubiquitylation of ARF in cells. Western analysis revealed that ARF ubiquitylation levels were induced in a dosage-dependent manner by ULF expression (Fig. 3a). To validate the importance of its ubiquitin ligase activity, we also made a point mutant of ULF (ULF-M) in which the conserved cysteine residue in the HECT domain was replaced by alanine (C1992A). In the same assay, this mutation completely abrogated ARF ubiquitylation by ULF (Fig. 3a). We also examined whether ULF promotes ARF ubiquitylation in a purified in vitro system. As shown in Fig. 3b, western blot analysis with an ARF-specific monoclonal antibody revealed that high levels of ubiquitylated ARF were generated by wild-type ULF but not by the catalytically inactive ULF-M. Because the human ARF polypeptide does not contain a lysine residue, these results demonstrate that ULF is a genuine ubiquitin ligase for lysine-independent ubiquitylation of ARF.

Figure 3. ULF-mediated effect on ARF ubiquitylation and degradation is modulated by NPM.

a, ARF is ubiquitylated by ULF in vivo. Lysates from transfected 293 cells were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-ARF antibody (ab-4), and separated proteins were blotted with antibodies against the HA (top) or monoclonal ARF (middle) antibody. Ectopic ULF in crude lysates were analysed by western blotting (WB) with anti-V5 antibody. b, ARF is ubiquitylated by ULF in vitro. See Methods for detail. c, Subcellular localization of ectopic ULF and endogenous ARF in H1299 cells. d, ARF ubiquitylation mediated by ULF is affected by NPM but not by NPM-c. e, ARF stability regulated by NPM is ULF dependent. Western blot analysis of cell extracts of H1299 cells treated with the indicated RNAi oligonucleotides by the antibodies shown. f, Inactivation of ULF extends the half-life of endogenous ARF protein in NPM-depleted H1299 cells. g, ULF-RNAi-mediated effects are reversed by ULF(R) expression in NPM-depleted H1299 cells.

Several recent studies have shown that nucleolar localization of ARF induced by NPM overexpression is crucial for ARF stabilization9–17,19–21. In particular, whereas NPM levels are very low in normal human fibroblasts, NPM overexpression occurs in many types of human cancer (Supplementary Fig. 7; refs 22, 23). As expected, on ectopic expression of wild-type NPM with ARF in human cells, NPM and ARF were co-localized in the nucleoli (Supplementary Fig. 8). However, in contrast to ARF, ULF was predominantly present in the nucleoplasm (Fig. 3c), suggesting that NPM overexpression in cancer cells induces ARF stabilization by keeping ARF away from its nucleoplasmic ubiquitin ligase. Indeed, ULF-dependent polyubiquitylation of ARF was severely inhibited by overexpression of NPM (Fig. 3d). Moreover, the coding sequences of the NPM gene are mutated in about 35% of primary acute myeloid leukaemias24–27. These NPM mutants (NPM-c), which failed to promote ARF retention in the nucleoli (Supplementary Fig. 8), had no obvious effect on ULF-mediated ubiquitylation of ARF (Fig. 3d).

To validate NPM-mediated effects on the ULF–ARF interaction in vivo, we examined whether NPM knockdown restores the ULF-dependent degradation of ARF in cancer cells. To this end, H1299 carcinoma cells were transfected with a NPM-specific siRNA (NPM-RNAi), a ULF-specific siRNA (ULF-RNAi), or a control siRNA (control RNAi). As expected, ARF was very stable in H1299 cells and the levels of ARF were not markedly affected by ULF depletion (data not shown). However, RNAi-mediated knockdown of NPM expression significantly decreased the levels of endogenous ARF (Fig. 3e). In particular, this effect was completely reversed by the concomitant knockdown of ULF (Fig. 3e). To corroborate these results, we also examined the half-life of ARF protein under different treatments. The long half-life of endogenous ARF in H1299 cells was decreased to less than 30 min by NPM depletion but was restored when both NPM and ULF were depleted (Fig. 3f). To demonstrate more rigorously the specificity of these effects, we included rescue controls for the RNAi depletion experiments. Thus, expression vectors encoding either wild-type ULF or catalytically inactive ULF-C1992A (ULF-M) were designed with a point mutation at the RNAi-1 targeting region to render them resistant to RNAi-1-mediated depletion (Supplementary Fig. 9). We then examined whether RNAi-resistant ULF(R) could restore ARF degradation in H1299 cells simultaneously depleted with NPM-RNAi and ULF-RNAi-1. Expression of RNAi-resistant wild-type ULF, but not C1992A-mutant ULF, significantly decreased the levels of ARF protein in these cells (Fig. 3g), indicating that the ubiquitin ligase activity is required for ULF-mediated ARF degradation. These data show that ULF induces the ubiquitylation and degradation of ARF but this activity is inhibited in these cancer cells because ULF and ARF exist mostly in different subcellular compartments.

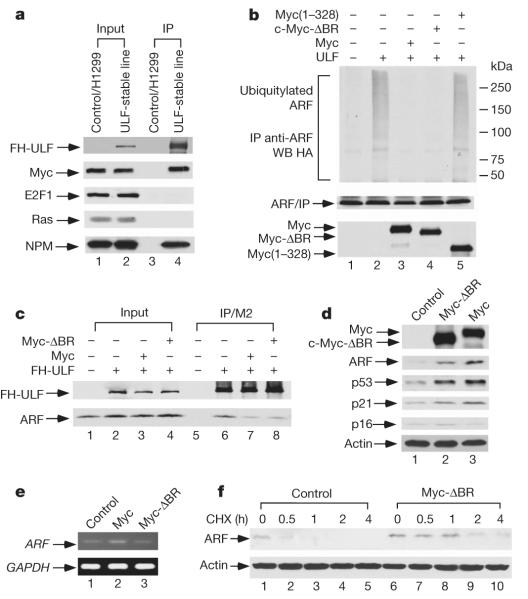

Numerous studies indicate that ARF function is markedly induced by oncogenic stress4–7. Although the mRNA levels for ARF are up-regulated in cancer cells, the ARF protein is also stabilized in most human tumour cells. Western analysis revealed that a significant amount of endogenous c-Myc, but not Ras or E2F1, was also co-purified with the ULF-associated complexes (Fig. 4a). We further confirmed that ULF interacts with c-Myc both in vitro and in vivo (Supplementary Fig. 10). We next examined whether ULF-mediated ARF ubiquitylation is modulated by c-Myc expression. As shown in Fig. 4b, c-Myc expression markedly decreased ULF-dependent ubiquitylation of ARF, although a mutant Myc(1–328), lacking the ULF-binding domain (Supplementary Fig. 11), failed to do so. Thus, binding between c-Myc and ULF is required for the Myc-mediated effect on ARF ubiquitylation. To investigate further this novel aspect function of c-Myc on ARF, we made a transcriptionally defective c-Myc mutant (Myc-ΔBR) that lacks the basic region required for DNA binding but retains its ability to interact with ULF (Supplementary Fig. 12). Myc-ΔBR suppressed ULF-mediated ARF ubiquitylation to the same extent as wild-type c-Myc (Fig. 4b), and the interaction between ARF and ULF was inhibited by expression of either wild-type Myc or Myc-ΔBR (Fig. 4c).

Figure 4. c-Myc overexpression blocks the interaction between ULF and ARF, which leads to c-Myc-mediated, transcription-independent ARF induction.

a, Myc is in the FH (tagged with Flag and HA)–ULF complexes. ULF-stable line, H1299 cells stably transfected with FH–ULF. b, Both wild-type Myc and Myc-ΔBR, but not Myc(1–328), inhibit ARF ubiquitylation mediated by ULF. c, Both wild-type Myc and Myc-ΔBR block the interaction between ULF and ARF. Western blot analysis of cell extracts from the transfected human 293 cells by anti-HA and anti-ARF. d, Both Myc-ΔBR and Myc stabilize ARF; induction of p53 and p21 in NHF-1 cells by adenoviral infection. e, Expression of mRNA encoding ARF by RT–PCR from the cells in d. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. f, Myc-ΔBR extends the half-life of endogenous ARF protein in NHF-1 cells.

Finally, to examine the transcription-independent effects of c-Myc on ARF induction under more physiological settings, we tested whether Myc-ΔBR expression was sufficient to activate the ARF–p53 pathway in normal human cells. Western analysis of the cell extracts revealed that Myc-ΔBR expression increased the steady-state levels of endogenous ARF in normal human fibroblasts (Fig. 4d). As expected, expression of the transcription-defective Myc-ΔBR had no obvious effect on the levels of ARF mRNA (Fig. 4e) but significantly extended the half-life of ARF polypeptides (Fig. 4f). Moreover, Myc-ΔBR expression stabilized p53 and induced p21 expression (Fig. 4d); conversely, Ink4a/p16 levels were not altered by Myc-ΔBR. These data show that c-Myc can stabilize ARF by inhibiting the ULF–ARF interaction and that c-Myc-mediated ARF induction is achieved, at least in part, through a transcription-independent mechanism.

ULF probably serves in normal cells as a sensor of oncogenic stress that represses ARF/p53 function in unstressed cells but permits transcription-independent induction of the ARF/p53 pathway in cells at risk of malignant transformation. Obviously, downstream lesions in the p53 pathway, such as p53 mutation and Mdm2 amplification, would impair p53 activation1–6. ULF itself is highly expressed in human tumours, including breast cancer and pancreatic cancer, on the basis of the cancer gene expression profile database from Oncomine Research28,29 (Supplementary Fig. 13). Mechanistically, our findings add a dynamic feature to the ARF regulatory pathway. On damage to DNA, ubiquitylation of p53 is inhibited by post-translational mechanisms that permit the immediate stabilization and activation of p53 (refs 4, 6). the activation of p53 by genotoxic stress is therefore a rapid process that prevents the further proliferation of cells bearing damaged DNA. In contrast, ARF induction was thought to be a much slower and largely irreversible process that may require epigenetic changes of the ARF gene locus1–6. Our findings significantly modify the current view of ARF regulation by showing that ARF can be activated through a very rapid and potentially reversible process involving ULF-mediated ubiquitylation, reminiscent of the interaction between p53 and Mdm2. We propose that activation of p53 by ARF, representing a critical barrier for oncogenesis30, requires both transcription-independent (fast) and transcription-dependent (slow) upregulation of ARF for effectively suppressing tumorigenesis in vivo.

METHODS

Plasmids, antibodies and cell culture

The full-length ULF was amplified by PCR from Marathon-Ready HeLa cDNA (Clontech, BD) and subcloned into pcDNA3.1/V5-His-Topo vector (Invitrogen) or pCIN4-Flag–HA expression vector31. Different site-directed mutations were generated with a QuikChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene). cDNA of cytoplasmic NPM mutant (NPM-c) was from B. Falini. For the Flag–HA–NPM construct, full-length NPM was amplified by PCR from Marathon-Ready HeLa, and sub-cloned into the pCIN4-Flag–HA vector. For the Flag–HA–NPM-c construct, full-length NPM-c was amplified by PCR from cDNA and subcloned into the pCIN4-Flag–HA vector. pcDNA3 c-Myc, PCMV-Tag2–Flag–Myc and pMT2T c-Myc-ΔBR were from R. Dalla-Favera. To construct GST–Myc or NPM vectors, cDNA sequences corresponding to the full-length proteins were amplified by PCR from other expression vectors and subcloned into pGEX (GST) vectors for expression in bacteria. For the different deletion mutant constructs, DNA sequences corresponding to different regions were amplified by PCR from the above constructs and subcloned into their respective expression vectors. pcDNA3.1–ARF, GST–ARF and pCIN4-HA–ARF–Flag were described previously14. To prepare the ARF–HA construct, the HA sequence was introduced to the C terminus of ARF by PCR and subcloned into PET14b vector for expression in bacteria. Anti-ULF antiserum was raised in rabbits and further affinity-purified by Bethyl Laboratories, Inc. (BL-4336). Rabbit polyclonal p14ARF (ab-4) and mouse monoclonal (ab-3) p14ARF antibodies were purchased from Labvision. Rabbit polyclonal p14ARF (NB 200–111) was from Novus Biologicals. Rabbit polyclonal p14ARF (A300-340A and A300-342A) was from Bethyl. p53-specific monoclonal (DO-1), anti-NPM (H106) polyclonal, anti-Myc monoclonal (9E10) and polyclonal (N-262) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Mouse anti-HA monoclonal antibody was gift from R. Baer’s laboratory. Anti-NPM monoclonal antibody (clone 322) was gift from B. Falini’s laboratory. Rat anti-HA monoclonal antibody was purchased from Roche.

H1299, U2OS, 293 and U-937 cells were maintained in DMEM medium; NHF-1, IMR-90 and WI-38 cells in MEM medium; SK-BR-3 cells in McCoy’s 5A medium; and BT-549 cells in RPMI medium. All media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum.

Purification of NPM complexes from human cells

The epitope-tagging strategy to isolate NPM-containing protein complexes from human cells was performed essentially as described previously14. In brief, to obtain a Flag–HA–NPM-expressing cell line, p53-null H1299 cells were transfected with pCIN4-Flag–HA–NPM and selected for 2 weeks in 1 mg ml−1 G418 (Gibco). The tagged NPM protein levels were detected by western blot analysis. The stable cell lines were chosen to expand for complex purification. Thus, the cells were grown in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum and harvested near confluence. The cell pellet was resuspended in buffer A (10 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride (PMSF) and protein inhibitor mixture (Sigma)). The cells were left to swell on ice for 15 min, after which 10% Nonidet P40 (Fluka) was added to a final concentration of 0.5%. The tube was vigorously vortex-mixed for 1 min. The homogenate was centrifuged for 10 min at 1,000g. The nuclear pellet was resuspended in ice-cold buffer C (20 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 0.4 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF and protein inhibitor mixture) and the tube was rocked vigorously at 4 °C for 45 min. The nuclear extract was diluted with buffer D (20 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 1 mM EDTA) to a final NaCl concentration of 100 mM, ultracentrifuged at 69,300g for 2 h at 4 °C. After filtration with 0.45-μm syringe filters (Nalgene), the supernatants were used as nuclear extracts for M2 immunoprecipitations by anti-Flag-antibody-conjugated agarose (Sigma). The bound polypeptides were eluted with the Flag peptide and were further affinity-purified by anti-HA-antibody-conjugated agarose (Sigma). The final eluates from the HA beads with HA peptides were resolved by SDS–PAGE on a 4–20% gradient gel (Novex) for silver staining or staining analysis with colloidal blue. Specific bands were cut out from the gel and subjected to mass-spectrometric peptide sequencing. GST pull-down. GST–Myc, GST–ARF and GST–NPM were induced in Rosetta (DE3) pLys cells (Novagen) at room temperature (25 °C), extracted with buffer BC500 (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.3, 0.2 mM EDTA, 500 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF) containing 1% Nonidet P40, and purified on glutathione-Sepharose (Pharmacia). pcDNA3.1-ULF full-length or different deletion mutants were labelled by incorporation of 35S-methionine during in vitro translation (TNT Coupled Reticulocyte Lysate System; Promega Corporation). 35S-labelled protein (5 μl) was incubated overnight with 3 μg of the purified GST–NPM, GST–Myc or GST–ARF proteins, as indicated, in the presence of 0.2% BSA in BC200 on a rotator at 4 °C. The proteins were pulled down with GST beads; the beads were washed three times with BC200 and twice with BC100. The beads were added to 40 μl of 1 × SDS sample buffer and boiled for 5 min. The presence of 35S-labelled protein was detected by autoradiography.

siRNA-mediated ablation of ULF, ARF, NPM and p53

Ablation of ULF was performed by transfection of the NHF-1 cells or the other cell lines with siRNA duplex oligonucleotides (ULF-RNAi-1 (5′-GGUAGUGACUCCACCCAUUUU-3′), ULF-RNAi-2(5′-GAACACAGAUGGUGCGAUAUU-3′),ULF-RNAi-3(5′-GACAAAGACUCAUACAAUAUU-3′) or ULF-RNAi-1 mutant (5′-GGUCGUGACUCCACUCAUUUU-3′)) synthesized by Dharmacon. NPM RNAi (On-Target-Plus Smartpool L-015737-00; Dharmacon), p14ARF RNAi (5′-GAUCAUCAGUCACCGAAGGUU-3′; Dharmacon), p53 RNAi (On-Target-plus Smartpool L-003329-00; Dharmacon) and control RNAi (On-target-plus siControl non-targeting-pool D-001810-10-20; Dharmacon) were also used for transfection. RNAi transfections were performed three times at 24–48-h intervals, with Lipofectamine 2000 or Oligofectamine (Invitrogen) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol.

Adenovirus infection

Adenoviruses expressing Myc or c-Myc-ΔBR were produced by using the AdEasy Adenoviral Vector System kit from Stratagene in accordance with the manufacturer’s manual. To construct adenovirus-Myc or c-Myc-ΔBR, the cDNAs were first cloned into pShuttle-IRES-hrGFP-1 vector. The resultant plasmids were then transformed for recombination into Escherichia coli strain BJ5183 containing the adenoviral backbone plasmid pAdEasy-1. The roughly 40-kilobase recombinant plasmids were linearized by digestion with PacI and purified by extraction with phenol/chloroform. AD-293 cells were then transfected with the purified DNA to produce adenoviruses expressing Myc or c-Myc-ΔBR. After one round of amplification in Ad-293 cells, the viruses were used to infect NHF-1 cells at 70% confluence.

Protein purification of components for in vitro ubiquitylation reactions

To prepare the purified components for the in vitro ubiquitylation assay, pet14b-ARF–HA was induced in Rosetta (DE3) pLys cells (Novagen) at room temperature, and proteins were extracted with buffer BC300 (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.3, 0.2 mM EDTA, 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF) containing 1% Nonidet P40, and purified on HA beads (Sigma). E3 (Flag–HA–ULF) was purified from H1299 stable cell line with M2 beads in BC300 (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.3, 0.2 mM EDTA, 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF). Rabbit E1 was obtained from Calbiochem. Rabbit E2 and His-ubiquitin were purchased as a purified protein from Affinity Inc.

In vitro ubiquitylation assays

The in vitro ubiquitylation assay was performed as described previously with some modifications14. ARF–HA protein (5 ng) produced by bacteria was mixed with other components, including E1 (10 ng) or E2 (His-UbcH5a, 100 ng), and 5 μg of His-ubiquitin (affinity) and E3 (purified from H1299 cells stably transfected with Flag–HA–ULF or Flag–HA–ULF-M) in 10 μl of reaction buffer (40 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM ATP, 2 mM DTT). The reaction was stopped after 3 h at 37 °C by the addition of SDS sample buffer, and subsequently resolved on SDS–PAGE gels for western blot analysis with anti-ARF antibody, and ULF or ULF-M levels with anti-HA antibody.

In vivo ubiquitylation assays

The in vivo ubiquitylation assay was performed as reported previously, with some modifications14. In brief, 293 cells were co-transfected by using the calcium phosphate method with expression vectors of ARF, HA–ubiquitin, ULF or ULF-M (C1992A), as indicated. Cells were harvested after 24 h and lysed in RIPA buffer with 0.05% SDS containing protease inhibitors. Lysates were precleared with rabbit IgG and protein A/G beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1 h, and precleared supernatants were precipitated with rabbit anti-ARF antibody ab-4 (Labvision) or NB200-111 (Novus Biologicals). Immune complexes recovered with protein A/G beads were washed six times with RIPA buffer and boiled in 2 × sample buffer for 5 min. Denatured immune complexes were resolved on an SDS gel. Proteins were detected with antibodies against HA (rat) and ARF (either monoclonal or rabbit). Ectopic protein levels in crude lysates were analysed by western blotting with anti-V5 antibody for ULF, or with anti-Myc (N-262) for Myc, Myc-ΔBR or Myc(1–328).

BrdU labelling. The BrdU incorporation assay was performed essentially as described previously14. In brief, cells were grown in medium containing 20 μM BrdU (Calbiochem) for 2 h and then fixed in 70% ethanol. DNA was denatured, and cells were permeabilized in 2 M HCl, 0.5% Triton X-100 (Sigma), neutralized in 0.1 M Na2B4O7 pH 8.5, and then blocked with 1% BSA in PBS. Anti-BrdU (Amersham) was added in accordance with the manufacture’s protocol. After being washed with 1% BSA/PBS, the cells were incubated with Alexa-488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Molecular Probes). Finally, cells were counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to reveal the nuclei.

RT–PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from cells by using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), and first-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA by using the SuperScript First-Strand synthesis system (Invitrogen) with the oligo(dT) primer. Prepared cDNA samples were amplified and analysed by PCR. The following primers were used in the PCR reaction: human ULF, 5′-GAAGTTTACCTCATTCCCACA-3′ (forward) and 5′-AACCGAGAGGAGCTGCTGAAA-3′ (reverse); human GAPDH, 5′-GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGT-3′ (forward) and 5′-GAAGATGGTGATGGGATTTC-3′ (reverse); human ARF, 5′-GTGCGCAGGTTCTTGGTGACC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTGCCCGTGGACCTGGCTGA-3′ (reverse).

Immunofluorescent staining

For immunofluorescent staining, the cells were plated on six-well glass coverslips. Cells on the coverslips were washed three times with PBS and then fixed for 20 min with 4% paraformaldehyde on ice, rehydrated for 5 min in serum-free DMEM, and permeabilized for 10 min with 0.2% Triton X-100 (Fisher). Cells were incubated for 30 min in 1% BSA (Sigma)/PBS (Cellgro). Primary rat monoclonal anti-HA antibody (Roche) (for transfected FH-ULF immunostaining) or polyclonal ARF (ab-4, for endogenous ARF immunostaining) was added to 1% BSA/PBS for 45 min at room temperature. After washing with 1% BSA/PBS, Alexa-conjugated anti-rat, anti-rabbit or anti-mouse antibody was added and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Finally, cells were counterstained with DAPI to reveal the nuclei, essentially as described previously32.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank R. Baer and R. Dalla-Favera for critical comments on this study; B. Falini and J. B. Yoon for providing reagents; W. Z. Zhang for helping in mass spectrometry analysis; E. McIntush for developing the anti-ULF antibody. This study was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society and NSFC-30628028. W.G. is an Ellison Medical Foundation Senior Scholar in aging.

Footnotes

Full Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Author Contributions The experiments were conceived and designed by D.C. and W.G. Experiments were performed mainly by D.C. Protein identification, mass spectrometric analysis and cloning were performed by D.C., J.S., W.Z. and J.Q. The paper was written by D.C. and W.G.

Author Information The full-length ULF sequence is deposited in GenBank under accession number EU489742.

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Lowe SW, Sherr CJ. Tumor suppression by Ink4a-Arf: progress and puzzles. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2003;13:77–83. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gil J, Peters G. Regulation of the INK4b-ARF-INK4a tumour suppressor locus: all for one or one for all. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:667–677. doi: 10.1038/nrm1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matheu A, Maraver A, Serrano M. The Arf/p53 pathway in cancer and aging. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6031–6034. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooks CL, Gu W. p53 ubiquitination: Mdm2 and beyond. Mol. Cell. 2006;21:307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sherr CJ. Divorcing ARF and p53: an unsettled case. Nature Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:663–673. doi: 10.1038/nrc1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kruse J-P, Gu W. Modes of p53 regulation. Cell. 2009;137:609–622. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christophorou MA, Ringshausen I, Finch AJ, Swigart LB, Evan GI. The pathological response to DNA damage does not contribute to p53-mediated tumour suppression. Nature. 2006;443:214–217. doi: 10.1038/nature05077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martins CP, Brown-Swigart L, Evan GI. Modeling the therapeutic efficacy of p53 restoration in tumors. Cell. 2006;127:1323–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuo ML, den Besten W, Bertwistle D, Roussel MF, Sherr CJ. N-terminal polyubiquitination and degradation of the Arf tumor suppressor. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1862–1874. doi: 10.1101/gad.1213904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Itahana K, et al. Tumor suppressor ARF degrades B23, a nucleolar protein involved in ribosome biogenesis and cell proliferation. Mol. Cell. 2003;12:1151–1164. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00431-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korgaonkar C, et al. Nucleophosmin (B23) targets ARF to nucleoli and inhibits its function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:1258–1271. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.4.1258-1271.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brady SN, Yu Y, Maggi LB, Weber JD. ARF impedesNPM/B23 shuttling in an Mdm2-sensitive tumor suppressor pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:9327–9338. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.21.9327-9338.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bertwistle D, Sugimoto M, Sherr CJ. Physical and functional interactions of the Arf tumor suppressor protein with nucleophosmin/B23. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:985–996. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.985-996.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen DL, et al. ARF-BP1/mule is a critical mediator of the ARF tumor suppressor. Cell. 2005;121:1071–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moulin S, Llanos S, Kim SH, Peters G. Binding to nucleophosmin determines the localization of human and chicken ARF but not its impact on p53. Oncogene. 2008;27:2382–2389. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colombo E, et al. Nucleophosmin is required for DNA integrity and p19Arf protein stability. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:8874–8886. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.20.8874-8886.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grisendi S, et al. Role of nucleophosmin in embryonic development and tumorigenesis. Nature. 2005;437:147–153. doi: 10.1038/nature03915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee JW, Choi HS, Gyuris J, Brent R, Moore DD. Two classes of proteins dependent on either the presence or absence of thyroid hormone for interaction with the thyroid hormone receptor. Mol. Endocrinol. 1995;9:243–254. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.2.7776974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.den Besten W, Kuo ML, Williams RT, Sherr CJ. Myeloid leukemia-associated nucleophosmin mutants perturb p53-dependent and independent activities of the Arf tumor suppressor protein. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1593–1598. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.11.2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colombo E, et al. Delocalization and destabilization of the Arf tumor suppressor by the leukemia-associated NPM mutant. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3044–3050. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng K, et al. The leukemia-associated cytoplasmic nucleophosmin mutant is an oncogene with paradoxical functions: Arf inactivation and induction of cellular senescence. Oncogene. 2007;26:7391–7400. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feuerstein N, Mond JJ. ‘Numatrin,’ a nuclear matrix protein associated with induction of proliferation in B lymphocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:11389–11397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nozawa Y, vanBelzen N, vanderMade ACJ, Dinjens WNM, Bosman FT. Expression of nucleophosmin/B23 in normal and neoplastic colorectal mucosa. J. Pathol. 1996;178:48–52. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199601)178:1<48::AID-PATH432>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Falini B, et al. Cytoplasmic nucleophosmin in acute myelogenous leukemia with a normal karyotype. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:254–266. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quentmeier H, et al. Cell line OCI/AML3 bears exon-12 NPM gene mutation-A and cytoplasmic expression of nucleophosmin. Leukemia. 2005;19:1760–1767. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grisendi S, Mecucci C, Falini B, Pandolfi PP. Nucleophosmin and cancer. Nature Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:493–505. doi: 10.1038/nrc1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saporita AJ, Maggi LB, Apicelli AJ, Weber JD. Therapeutic targets in the ARF tumor suppressor pathway. Curr. Med. Chem. 2007;14:1815–1827. doi: 10.2174/092986707781058869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finak G, et al. Stromal gene expression predicts clinical outcome in breast cancer. Nature Med. 2008;14:518–527. doi: 10.1038/nm1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buchholz M, et al. Transcriptome analysis of microdissected pancreatic intraepithelial neoplastic lesions. Oncogene. 2005;44:6626–6636. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zindy F, et al. Myc signaling via the ARF tumor suppressor regulates p53-dependent apoptosis and immortalization. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2424–2433. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.15.2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abide WM, Gu W. p53-Dependent and p53-independent activation of autophagy by ARF. Cancer Res. 2006;68:352–357. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li M, et al. Mono- versus polyubiquitination: differential control of p53 fate by Mdm2. Science. 2003;302:1972–1975. doi: 10.1126/science.1091362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.