Abstract

The cornea receives the densest sensory innervation of the body, which is exclusively from small-fiber nociceptive (pain-sensing) neurons. These are similar to those in the skin of the legs, the standard location for neurodiagnostic skin biopsies used to diagnose small-fiber peripheral polyneuropathies. Many cancer chemotherapy agents cause dose-related, therapy-limiting, sensory-predominant polyneuropathy. Because corneal innervation can be detected noninvasively, it is a potential surrogate biomarker for skin biopsy measurements. Therefore, we compared hindpaw-skin and cornea innervation in mice treated with neurotoxic chemotherapy. Paclitaxel (0, 5, 10, or 20mg/kg) was administered to C57/Bl6 mice and peri-mortem cornea and skin biopsies were immunolabeled to reveal and permit quantitation of innervation. Both tissues demonstrated dose-dependent, highly correlated (r = 0.66) nerve fiber damage. These findings suggest that the quantification of corneal nerves may provide a useful surrogate marker for skin peripheral innervation.

Keywords: Corneal nerves, peripheral neuropathy

The cornea receives the densest sensory innervations of any anatomical site (Bonini et al, 2001) and nerves can be easily imaged in the cornea, even in vivo, given its accessibility and transparence. Corneal innervation has been studied extensively in a number of ocular diseases; however, little information is available in the setting of systemic peripheral nerve damage.

Use of cancer chemotherapy is increasing due to improved survival rates and new drug discovery, but many patients are unable to complete optimal chemotherapy regimens due to adverse events. In fact, painful, distal sensory chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) is dose-limiting for many antineoplastics, including taxanes, vinca alkaloids, platinum-complex, and proteasome-inhibitors1. Small-diameter pain fibers are the most often involved because their inefficient non-saltatory conduction plus their minimal capacity for axon transport make them exquisitely vulnerable to chemotherapy-evoked mitochondrial toxicity (Flatters et al, 2006). As a consequence, neuropathic pain is common in CIPN, and this can be debilitating, long-lasting and treatment-resistant, forcing physicians to curtail chemotherapy, even at the risk of compromising survival. The effect of systemic chemotherapy on corneal nerves is unknown; however, we hypothesized that they should be similarly affected as longer axons innervating other anatomical areas. If this hypothesis were true, it could have clinical implications, specifically the use of in vivo corneal confocal microscopy (CCM), as a potential non-invasive surrogate marker for CIPN. CCM allows repeatable visualization and quantitation of sub-basal corneal nerves.

For early CIPN diagnosis, distal-leg skin biopsy to measure intraepidermal nerve-fiber density (IENFD) is most recommended although biopsies are slightly invasive and technically demanding to process and interpret (England et al, 2009). Small series suggest that CCM can detect corneal nerve damage in sensory polyneuropathy (Gemignani et al, 2010; Mimura et al, 2008); however, sensitivity is a concern given the short length of corneal afferents compared to the long axons innervating the feet. Thus, corneal and distal-limb measurements deserve comparison. The few studies of diabetic polyneuropathy are encouraging, but diabetics without polyneuropathy also had reduced corneal nerve-fiber density (CNFD) and distal-leg IENFD, and correlation was modest (rs = 0.385), (Quattrini et al, 2007). CCM has been studied in a limited number of patients with non-diabetic polyneuropathies. Our single-case report of capecitabine-CIPN in this journal prompted the current prospective, controlled, dose-response comparison of skin and corneal measurements in a mouse model (Ferrari et al, 2010). We decided to study CIPN induced by paclitaxel, a compound of the taxane family, because taxanes are globally used for common cancers, and because persistent painful CIPN develops in almost ¼ of patients receiving standard doses and nearly all aggressively treated patients (Gradishar et al, 2005).

Using approved methods, six-week-old male C57/BL6 mice received one intraperitoneal injection of paclitaxel dissolved in Cremophor-EL at doses spanning the experimental range; 5 mg/kg (n=8), 10 mg/kg (n=8), or 20 mg/kg (n=13). Fourteen untreated mice provided controls. At sacrifice two weeks later, corneas and 2 mm punch-biopsies from one plantar hindpaw were removed, fixed in lysine-periodate-paraformaldehyde, vertically sectioned (50 μm) and immunohistochemically labeled against PGP 9.5 (skin) or anti–beta 3 tubulin (corneas). Secondary antibody comprised fluorophore-conjugated donkey anti rabbit IgG FITC. IENFD was quantitated by a single blinded morphometrist using standard clinical diagnostic methods (England et al, 2009). Total lengths of labeled corneal axons were digitally measured through segmentation, binarization and skeletonization (The Mathworks, Inc., Natick, MA). Between-group differences were assessed by ANOVA plus Kruskal-Wallis post-hoc tests; Pearson correlation coefficients were used.

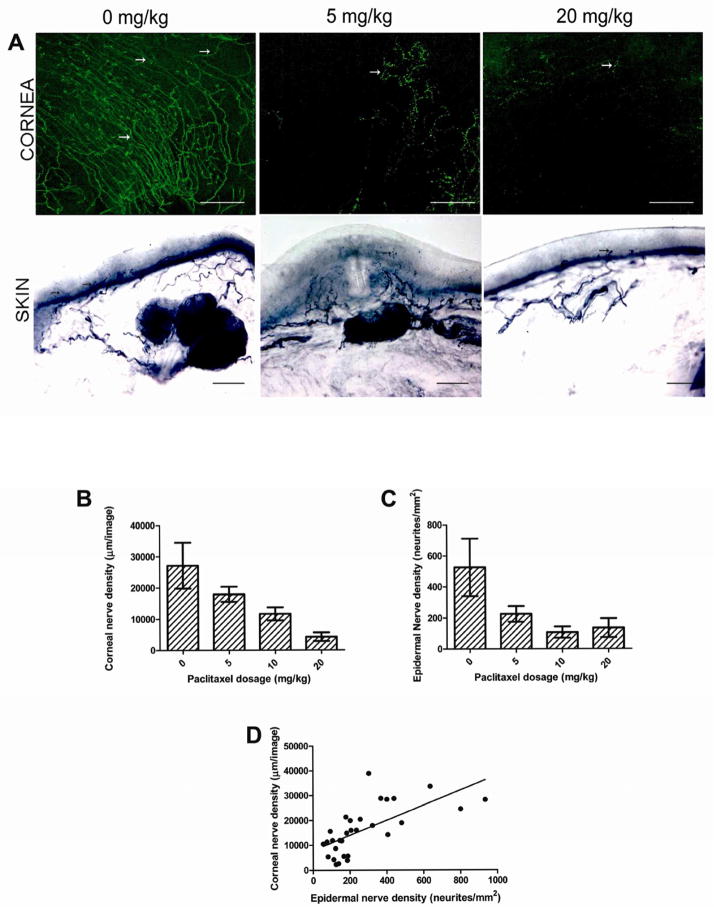

In vivo corneal examination revealed no keratitis or lesions in treated or untreated mice. Immunohistochemistry revealed highly significant dose-related reductions in corneas and hind-paws (Fig. 1A). CNFD averaged 27,131 ± 2,446 μm/image in untreated mice, 17,924 ± 848 μm/image among 5 mg/kg mice, 11,634 ± 783 μm/image among 10 mg/kg mice, and 4,259 ± 523 μm/image among 20 mg/kg mice (all P < 0.0001), (Fig. 1B); consistent with dose-related neurotoxicity. Biopsies from hind paw-skin biopsies revealed similar dose-related reductions; 527 ± 53 neurites/mm2 skin surface area in untreated mice; 226 ± 19 neurites/mm2 skin surface area among 5 mg/kg mice, 107 ± 14 neurites/mm2 skin surface area among 10 mg/kg mice, and 135 ± 17 neurites/mm2 skin surface area among 20 mg/kg mice (all P < 0.0001), (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Reductions in corneal and hindpaw small-fiber innervation following paclitaxel administration. (A) Immunohistochemical visualization of sensory nerve endings (arrows) in anti–beta 3 tubulin immunoreactive mouse corneas (upper row) and anti-PGP9.5-immunoreactive hindpaw skin biopsies. Both tissues had highly significant dose-related loss of labeled innervation (P < 0.0001); (magnification 200x). Bar length: 300 μm (cornea), 50 μm (skin). (B) Corneal nerve density is inversely related with paclitaxel dosage (P < 0.0001). (C) Epidermal nerve density is inversely related with paclitaxel dosage (P < 0.0001). (D) Corneal and epidermal nerve density is highly correlated (r = 0.66). Bars represent mean with standard deviation.

In summary, nerves in the skin and in the cornea were progressively reduced following increasing doses of paclitaxel. Indeed, correlation between CNFD and IENF measurements was good (r = 0.66) (Fig. 1D).

Interestingly, the cornea did not show any obvious pathological change even in the group of animals with the most severe nerve depletion. This could be due the fact that even a limited amount of spared fibers may be sufficient to maintain corneal integrity. Alternatively, the relatively short observation time (two weeks) may not be sufficient for epithelial damage to develop. Although it is believed that extensive nerve damage is required to develop neurotrophic keratitis, the exact threshold is still unknown. In this vein, we observed that neurotrophic keratitis developed in mice after complete ablation of corneal nerves (Ferrari et al, 2011).

These findings support our hypothesis that the cornea may be a useful “window” to image peripheral nerves. In other words, corneal axons might provide surrogate biomarkers for distal-limb skin biopsy in detecting early paclitaxel axonopathy. Additionally, dose-response relationships were even more linear in the cornea than the hind-paw, suggesting that corneal imaging may effectively capture peripheral nerve damage. The chief limitation of this study is the use of ex vivo rather than in vivo imaging as CCM was not available for this animal study. In fact, given the increasing availability of non- repeatable, non-invasive, CCM imaging of patients, our data suggest that this technique be considered for prospective comparison with distal-limb skin biopsy measurements in patients with sensory polyneuropathies.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Supported in part by the Public Health Service (NINDS K24-NS059892 and NEI RO1-EY20889). Presented in abstract form at the annual meetings of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology and the American Neurologic Association.

Abbreviations

- CIPN

chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy

- IENFD

intraepidermal nerve-fiber density

- CCM

in vivo corneal confocal microscopy

- CNFD

corneal nerve-fiber density

Footnotes

Author Contributions: All authors concurred in the experimental, data analysis, manuscript writing and approved the final version.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bonini S, Rama P, Olzi D, Lambiase A. Neurotrophic keratitis. Eye (Lond) 2003;17(8):989–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England JD, Gronseth GS, Franklin G, et al. Practice Parameter: Evaluation of distal symmetric polyneuropathy: role of autonomic testing, nerve biopsy, and skin biopsy (an evidence-based review). Report of the American Academy of Neurology, American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine, and American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Neurology. 2009;72:177–184. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000336345.70511.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari G, Gemignani F, Macaluso C. Chemotherapy-associated peripheral sensory neuropathy assessed using in vivo corneal confocal microscopy. Archives of Neurology. 2010;67:364–365. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari G, Chauhan SK, Ueno H, Nallasamy N, Gandolfi S, Borges L, Dana R. A novel mouse model for neurotrophic keratopathy: trigeminal nerve stereotactic electrolysis through the brain. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(5):2532–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatters SJ, Bennett GJ. Studies of peripheral sensory nerves in paclitaxel-induced painful peripheral neuropathy: evidence for mitochondrial dysfunction. Pain. 2006;122:245–257. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemignani F, Ferrari G, Vitetta F, Giovanelli M, Macaluso C, Marbini A. Non-length-dependent small fibre neuropathy. Confocal microscopy study of the corneal innervation. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2010;81:731–733. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.177303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradishar WJ, Tjulandin S, Davidson N, et al. Phase III trial of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel compared with polyethylated castor oil-based paclitaxel in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7794–7803. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimura T, Amano S, Fukuoka S, et al. In vivo confocal microscopy of hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy. Curr Eye Res. 2008;33:940–945. doi: 10.1080/02713680802450992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quattrini C, Tavakoli M, Jeziorska M, et al. Surrogate markers of small fiber damage in human diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes. 2007;56:2148–2154. doi: 10.2337/db07-0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]