Abstract

The present study aimed to analyze the water polo matches of the men’s World Championships, comparing technical and tactical aspects of winning and losing teams, during closed (≤ 3 goals of margin of victory at the end of the 4th quarter; winning, W; losing, L) and unbalanced (>3 goals; winning, MW; losing, ML) games. Therefore, 42 of the 48 (6 were draw at end of the 4th quarter) matches were considered. According to each game situation (i.e., even, counterattack, power-play, transition), a notational analysis was performed in relation to the following aspects: occurrence of actions, action outcome, execution and origin of shots, and mean duration. In addition, the occurrence of the offensive (and role) and defensive arrangements of even and power-play were analyzed. To show differences (p < 0.05) in terms of margin of victory, an analysis of variance was applied. Although ML (74 ± 11%) performed more even actions than W (68 ± 7%) and MW (69 ± 6%), the latter teams (W = 9 ± 6%; MW = 13 ± 6%) performed more counterattacks than L (3 ± 2%) and ML (5 ± 5%). Power-play is more played during closed (W = 20 ± 3%; L = 22 ± 3%) than unbalanced games (MW = 17 ± 4%; ML = 16 ± 7%). Moreover, differences in terms of margin of victory emerged for mean duration (even, power-play, transition), action outcome (even, power-play), zone origin (even, counterattack, power-play) and technical execution (even, power-play) of shots, and even and power-play offensive (and role) and defensive arrangements. Divergences mainly emerged between closed and unbalanced games, highlighting that the water polo matches of the men’s World Championships need to be analyzed either considering the winning and losing outcome of match and specific margins of victory. Thus, coaches can advance their knowledge, considering that closed and unbalanced games are largely characterized by the opponent’s exclusion fouls to perform power-play actions, and by a divergent grade of defensive skills regardless of game situation, respectively.

Key points.

The water polo matches of the men’s World Championships need to be analyzed considering successful/unsuccessful teams as well as specific margins of victory.

Closed matches are mainly characterized by a high occurrence of the opponent’s exclusion fouls to perform the power-play actions.

For the unbalanced matches, a divergent grade of defensive skills between teams has been highlighted.

Coaches can improve their training, considering the opponent’s exclusion fouls to perform the power-play actions towards a closed match, and caring the defensive skills of each game situation towards an unbalanced match.

Key words: Technical indicators, tactical indicators, match outcome, playing situation, closed games, unbalanced games

Introduction

Water polo originated in the late 1800s and is one of the oldest team sports of the modern Olympic Games. Nevertheless, every two years, the Federation Internationale De Natation (FINA) structures another planetarium water polo competition: the World Championships. In 2009, the 13th edition of this international competition has been organized in Rome (Italy), counting the participation of sixteen national teams coming from every continent. In this Championship, matches have been played by two teams, consisting of 6 field players and a goalkeeper, for four 8-minute clock-time (i.e., excluding breaks in play) quarters, and in a court measuring 30m X 20m. Teams had to play a single action for a maximum of 30 seconds of clock time. Moreover, from the moment that a defender commits an exclusion foul, the latter has to stay out of the play for 20-second clock-time and to go to a delimited corner area located back to the goal line and close to his team bench (FINA, 2010), allowing the offence team to play with a player numerical advantage.

At present, water polo has been mainly analyzed in terms of physiological characteristic (Lozovina et al., 2004; Pavlik et al., 2005; Platanou and Geladas, 2006; Sardella et al., 1992; Smith, 1998; Tan et al., 2009; Tsekouras et al., 2005) and swimming capability (Falk et al., 2004; Melchiorri et al., 2009; Mujika et al., 2006; Platanou, 2006). Moreover, the situational nature of water polo makes difficult the game analyses in terms of replication (Lupo et al., 2010). Nevertheless, technical and tactical studies of this sport have been provided in terms of team (Hughes et al., 2006; Lupo et al., 2009; 2011) and play role (Lozovina et al., 2004; Lupo et al., 2007; 2008) efficacy, rules evolution (Platanou et al., 2007), different competition levels (Lupo et al., 2010), and influence of match outcome (Argudo Iturriaga et al., 2009; Escalante et al., 2011; Lupo et al., 2011; Smith, 2004; Vila et al., 2011). In particular, despite the latter aspect has been recently high-lighted for other team sports like basketball (Csataljay et al., 2009; Gómez et al., 2008; Sampaio and Janeira, 2003; Sampaio et al., 2010) and rugby (Vaz et al., 2010), only few water polo studies (Escalante et al., 2011; Vila et al., 2011) have been investigated for the present men’s inter-national rule (FINA, 2010). However, there is a lack of studies considering a specific margin of victory (i.e., a number of goal difference in the final score between winning and losing teams) as a discriminating factor to analyze the technical and tactical aspects of a water polo match.

Thus, the present study aimed to analyze the men’s water polo matches played during the 13th edition of the World Championships (Roma, 2009) by comparing technical and tactical playing aspects of winning and losing teams playing in matches with different margins of victory, that is, closed games, 1-3 goals; and unbalanced games, >3 goals.

Methods

Sample

The Review Board of the University of Rome Foro Italico approved this study to investigate the game aspects of the water polo matches of the men’s World Championships.

Each team scoring of a single match was inserted in one of the four categories related to the established margin of victory. For example, not more than three goals winning team, W; not more than three goals losing team, L; more than three goals winning team, MW; and more than three goals losing team, ML. Only the match characterized by a winning and losing team at the end of 4th quarter has been considered for the study, whereas all matches ending draw were excluded from the experimental sample. Therefore, 42 of the 48 (6 matches were draw at end of the 4th quarter) men’s water polo matches of the 13th FINA World Championships (i.e., Rome 2009) were considered for the study.

Considering the championship participation, 9 teams came from Europe (Germany, Hungary, Montenegro, Croatia, Serbia, Spain, Macedonia, Romania, Italy), 2 from Asia (China, Kazakhstan), 2 from North (USA, Canada), 1 from South (Brazil) America, 1 from Africa (South Africa), and 1 from Oceania (Australia). In relation to the four margins of victory, W, L, MW, and ML category counted 20, 20, 22, and 22 teams playing scores, respectively; while, the specific margins of victory of the closed and unbalanced games were 1.8 ± 0.8 (range: 1-3) and 8.1 ± 3.2 (range: 4-17) goals, respectively.

Although only based on established water polo habits and coaches’ statements (and not on published data), the elite men’s water polo players observed in the present study are usually involved in a minimum of six to a maximum of twelve 120/180-min training sessions per week.

Variables and instruments

All the men’s water polo matches of the 13th World Championships were recorded by means of a video camera (JVC GR-DVL 107, Yokohama, Japan) positioned at a side of the pool, at the level of the midfield line, at a height of 12m and at a distance of 10m from the pool. Subsequently, the video recordings were replayed by a Video Home System (SONY SLV-E1000VC, Tokyo, Japan) to facilitate the handling of the playing images (i.e., still, replay, slow motion picture, etc.). Therefore, a notational analysis has been executed according to the following technical and tactical indicators (Table 1), which were considered in relation to even, counterattack, power-play, and transition playing situation. In particular an even situation is characterized by a number of offensive players related to the ball position which is never larger than that of the defence, within the offensive half-court; a counterattack refers to playing situations where, relatively to the ball position, the number of offensive players is larger than that of the defence, determining, therefore, at the moment of the end of the action, a real numerical advantage for the offensive players; a power-play situation originates following an exclusion foul committed by a defensive player who has to be out from the play for 20-s clock time; a transition situation is a swimming play phase performed further to a defensive action and before of the offensive arrangement of the most advanced player within the offensive half-court.

-

1)

Occurrence of actions, that is, the ratio between the number of even, counterattack, power-play and transition actions, with respect to the total number of actions of match. In particular, an action was defined from the moment that a player gained possession of the ball until possession was lost to the opposing team or re-obtained after shot, or other play event coincident with the resetting of the 30s action-time);

-

2)

Mean duration of actions. Mean clock time of offensive actions in seconds, electronically registered by referees;

-

3)

Action outcome, the ratio between the number of goals, no goal shots, offensive fouls, lost possessions, and exclusions and penalties achieved, occurring at the moment of the end of action, with respect to the total number of actions;

-

4)

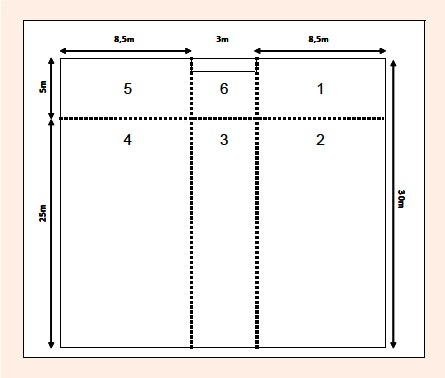

Origin of shots, the ratio between the number of shots performed from one of the six zones (Figure 1), with respect to the total number of shots.

-

5)

Technical execution of shots, the ratio between the number of free throws (i.e., overhead shots with no fake performed further to a received foul committed outside the 5-meter area), drive shots (i.e., overhead shots with no fake), shots after 1 fake, shots after 2 fakes, shots after more than 2 fakes, backhand shots, and off-the-water shots (i.e., shots attempted while the ball is controlled in the water), with respect to the total number of shots;

-

6)

Centre forward versus perimeter players, the ratio between the number of even actions performed by means of the centre forward (i.e., the most advanced offensive player, who is centrally located and 2-3 meters distant from the opponent goal) and perimeter player (i.e., the players located around the centre forward, more distant from the opposite goal than the latter role) events, at the moment of the end of action, with respect to the total number of even actions];

-

7)

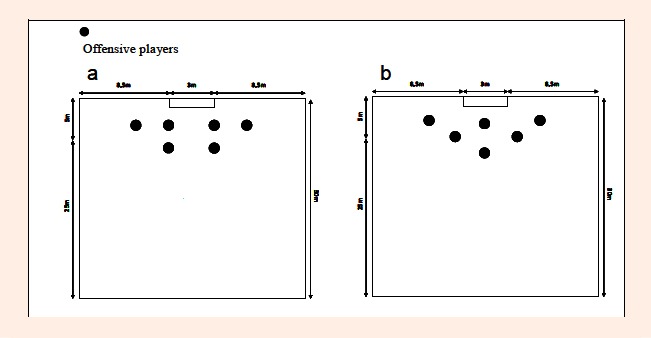

Offensive arrangement. The occurrence of even offensive arrangement, the ratio between the number of the 6 versus 6 and 5 versus 5, 4 versus 4 and 3 versus 3, and 2 versus 2 and 1 versus 1 arrangements, occurring at the moment of the end of even action, with respect to the total number of even actions). The occurrence of power-play offensive arrangement and role analysis, the ratio between the number of power-play actions performed by means of the "4:2" (Figure 2a) and "3:3" (Figure 2b) offensive arrangements, and by the centre forward and perimeter play events, at the moment of the end of action, with respect to the total number of power-play actions;

-

8)

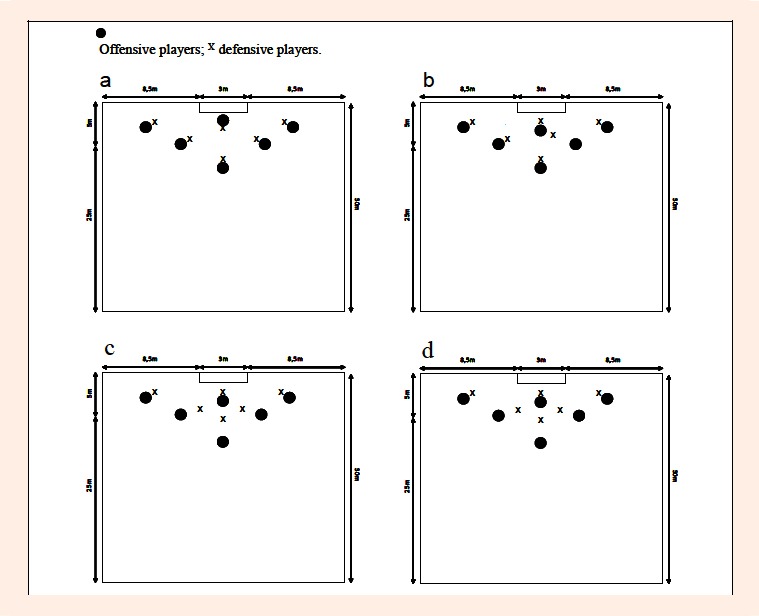

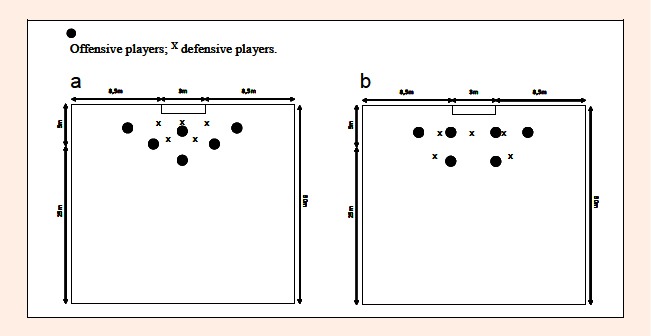

Defensive arrangement. The occurrence of even defensive arrangement, the ratio between the number of "pressing" (Figure 3a), "zone 1-2" (Figure 3b), "zone M" (Figure 3c), and "zone 2-3-4" (Figure 3d) defensive arrangements, occurring at the moment of the end of the opponent’s even actions, and the total number of the opponent’s even actions. The occurrence of power-play defensive arrangement, the ratio between the number of "cluster" (Figure 4a) and "anticipating" (Figure 4b) defensive arrangement, occurring at the moment of the end of the opponent’s power-play actions, with respect to the total number of the opponent’s power-play actions;

Table 1.

List of technical and tactical indicators in relation to playing situations.

| Technical and Tactical Indicators | Playing Situations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) Actions (%) | Even | Counterattack | Power-play | Transition | |

| 2) Mean duration of actions (s) | Even | Counterattack | Power-play | Transition | |

| 3) Action outcome (%) | goals | Even | Counterattack | Power-play | |

| no goal shots | Even | Counterattack | Power-play | ||

| offensive fouls | Even | Counterattack | Power-play | Transition | |

| lost possessions | Even | Counterattack | Power-play | Transition | |

| exclusions achieved | Even | Counterattack | Power-play | Transition | |

| penalties achieved | Even | Counterattack | Power-play | ||

| 4) Origin of shots (%) (Fig. 1) | shots originated from zone 1 | Even | Counterattack | Power-play | |

| shots originated from zone 2 | Even | Counterattack | Power-play | ||

| shots originated from zone 3 | Even | Counterattack | Power-play | ||

| shots originated from zone 4 | Even | Counterattack | Power-play | ||

| shots originated from zone 5 | Even | Counterattack | Power-play | ||

| shots originated from zone 6 | Even | Counterattack | Power-play | ||

| 5) Technical execution of shots (%) | free throws | Even | Counterattack | Power-play | |

| drive shots | Even | Counterattack | Power-play | ||

| shots after 1 fake | Even | Counterattack | Power-play | ||

| shots after 2 fakes | Even | Counterattack | Power-play | ||

| shots after >2 fakes | Even | Counterattack | Power-play | ||

| backhand shots | Even | Counterattack | Power-play | ||

| off-the-water shots | Even | Counterattack | Power-play | ||

| 6) Centre Forward versus Perimeter Players (%) | centre forward actions | Even | |||

| perimeter player actions | Even | ||||

| 7) Offensive Arrangements (%) | 6vs6 and 5vs5 offensive arrangements | Even | |||

| 4vs4 and 3vs3 offensive arrangements | Even | ||||

| 2vs2 and 1vs1 offensive arrangements | Even | ||||

| 4:2 offensive arrangements/perimeter players (Fig. 2a) | Power-play | ||||

| 4:2 offensive arrangements/centre forwards (Fig. 2a) | Power-play | ||||

| 3:3 offensive arrangements/perimeter players (Fig. 2b) | Power-play | ||||

| 3:3 offensive arrangements/centre forwards (Fig. 2b) | Power-play | ||||

| 8) Defensive Arrangements (%) | pressing defensive arrangements (Fig. 3a) | Even | |||

| zone 1-2 defensive arrangements (Fig. 3b) | Even | ||||

| zone M defensive arrangements (Fig. 3c) | Even | ||||

| zone 2-3-4 defensive arrangements (Fig. 3d) | Even | ||||

| cluster defensive arrangements (Fig. 4a) | Power-play | ||||

| anticipating defensive arrangements (Fig. 4b) | Power-play | ||||

Figure 1.

Schema of the division of the court according to 6 zones. Zone 1: inside penalty area, from the right post to the right lateral line; Zone 2: outside penalty area, from the right post to the right lateral line; Zone 3: outside penalty area, within the goal posts; Zone 4: outside penalty area, from the left post to the left lateral line; Zone 5: inside penalty area, from the left post to the left lateral line; Zone 6: inside penalty area, within the goal posts.

Figure 2.

Schemas of the power-play offensive arrangements: a) “4:2” (i.e., four offensive players at 2-meters and two at 4- or 5-meters distant from the goal line); and b) “3:3” (i.e., three offensive players at 2-meters, two at 4- or 5-meters, and one centrally positioned at 5- or 6-meters distant from the goal line).

Figure 3.

Schemas of the even defensive arrangements: a) “pressing” (i.e., each defensive player is exclusively positioned at facing of a single offensive player); b) “zone 1-2” (i.e., one of the defensive players positioned in correspondence of the right side offensive arrangement systematically occupying the opponent centre forward playing zone, in order to doubly mark the latter offensive player); c) “zone M” (i.e., one of the defensive players occupying the opponent centre forward playing zone, in order to doubly mark the latter offensive player, and one or two defensive players positioned in line or forward with respect to direct opponent player), and d) “zone 2-3-4” (i.e., the defensive players positioned in correspondence of the left, central, and right side of the perimeter offensive players systematically occupying the opponent centre forward playing zone, in order to doubly mark the latter offensive player).

Figure 4.

Schemas of the power-play defensive arrangements: a) “cluster” (i.e., absence of any defensive player between the perimeter offensive players); and b) “anticipating” (i.e., one or more than one defensive player between the perimeter offensive players.

To avoid any inter-observer variability, a single experienced observer (with more than 300 analyzed water polo matches) scored all matches. However, before the study, the observer scored a random sample of 8 matches twice, where each observation was separated by 2 weeks, and quantified in terms of reliability (Kappa coefficients). The results reported agreement coefficients never below than 0.97.

Data analysis

Means, standard deviations and ranges (i.e., minimum and maximum) were calculated for each dependent variable. Statistical analyses were conducted using a SPSS package (version 17.00, Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and the criterion for significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) approach was applied for the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th indicator, where the playing situations (i.e., even, counterattack, power-play, and transition) were considered as dependent variables and the margin of victory (i.e., W, L, MW, and ML) as independent ones. Although for the other indicators, the independent variable remained the same, the dependent variables were the offensive roles which ended the even actions (i.e., centre forward versus perimeter player), the offensive even arrangements (i.e., 6 versus 6 or 5 versus 5, 4 versus 4 or 3 versus 3, and 2 versus 2 or 1 versus 1), the offensive roles which ended the power-play actions in relation to the offensive arrangements (i.e., centre forward and perimeter players, during the 4:2 and 3:3 arrangement), the defensive even arrangements (i.e., "pressing", "zone 2", "zone M", and "zone 2-3-4"), and the defensive power-play arrangements (i.e., "cluster", "anticipating"). Then, for each obtained significant difference in terms of margin of victory (the independent variable), Bonferroni’s post-hoc test was applied. Nevertheless, to provide meaningful analysis for comparisons, the Cohen’s effect sizes (ESs) were also calculated (Cohen, 1988). In particular, an ES ≤ 0.2, was considered trivial; from 0.3 to 0.6, small; from 0.7 to 1.2, moderate; and >1.2, large.

Results

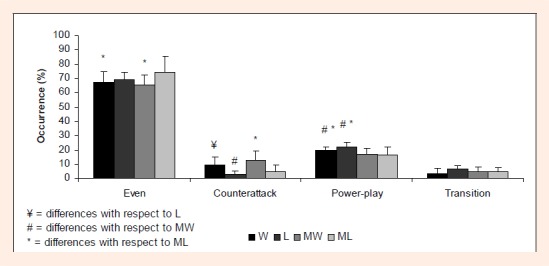

The percentage of occurrence of actions (Figure 5) reported differences for even (p = 0.002, ES range: 0.3-0.4), counterattack (p < 0.001, ES range: 0.6-0.7), and power-play (p = 0.001, ES = 0.4) situation. In particular, for even actions, differences emerged between ML and W (p = 0.024, ES = 0.3), and MW (p = 0.002, ES = 0.4); for counterattacks, between W and L (p = 0.001, ES = 0.6), L and MW (p < 0.001, ES = 0.7), and MW and ML (p < 0.001, ES = 0.6); and, for power-play actions, between W and MW (p = 0.035, ES = 0.4), and ML (p = 0.016, ES = 0.3), and L with respect to MW (p = 0.004, ES = 0.4) and ML (p = 0.002, ES = 0.4). For transitions, no difference has been reported.

Figure 5.

Men’s Water Polo World Championships. Means and standard deviations of the frequencies of occurrence (%) of actions of the W, L, MW, ML, in relation to the playing situations (i.e., even, counterattack, power-play, transition). å Differences (p≤0.05) with respect to L; # Differences with respect to MW; * Differences with respect to ML.

Table 2 shows differences in terms of margin of victory for mean duration of actions (even: p < 0.001, ES = 0.4; power-play: p < 0.001, ES range = 0.5-0.6; transition: p = 0.004, ES range = 0.4-0.5), action outcome (even: goal, p < 0.001, ES range = 0.7-0.8; exclusion, p = 0.004, ES range = 0.4-0.5; lost possession, p = 0.043, ES = 0.3; penalty, p < 0.001, ES = 0.6; power-play: goal, p < 0.001, ES range = 0.5-0.6; no goal shot, p = 0.001, ES = 0.5; lost possession, p = 0.004, ES = 0.5), and zone origin (even: Z3, p = 0.044, ES = 0.4; counterattack: Z5, p = 0.024, ES = 0.4; Z6, p = 0.002, ES = 0.5; power-play: Z4, p = 0.001, ES range = 0.4-0.6) and technical execution (even: drive shot, p = 0.002, ES = 0.5; off-the-water shot, p = 0.016, ES = 0.5; power-play: shot after 1 fake, p = 0.035, ES = 0.4) of shots, in relation to the playing situations.

Table 2.

Men’s Water Polo World Championship matches. Means, standard deviations, ranges, and differences (p≤0.005) between margins of victory (i.e., 1-3 goals winning teams, W; 1-3 goals losing teams, L, >3 goals winning teams, MW; >3 goals losing teams, ML), for mean duration of actions, action outcome, zone origin and technical execution of shots, occurring at the end of even, counterattack, power-play, and transition.

| Even | Counterattack | Power-play | Transition | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W | L | MW | ML | W | L | MW | ML | W | L | MW | ML | W | L | MW | ML | |

|

Mean Duration (s) |

22±2 (19-25)††† |

20±2 (18-22)** |

21±2 (17-25) |

22±1 (20-24) |

14±3 (11-18) |

14±4 (8-19) |

13±2 (11-18) |

13±4 (5-17) |

15±1 (13-17)‡‡ |

15±2 (12-18)# |

12±3 (9-17)*** |

16±3 (11-20) |

4±2 (2-7)† |

8±4 (3-14)** |

6±2 (2-9) |

5±4 (0-11) |

| Action Outcome (%) | ||||||||||||||||

| Goals | 8±4 (0-14)‡‡‡ |

6±4 (3-14)‡‡‡ |

19±6 (9-27)*** |

5±3 (0-9) |

35±33 (0-100) |

40±45 (0-100) |

41±27 (0-88) |

17±20 (0-50) |

44±17 (14-70)** |

36±11 (21-58)‡‡ |

54±18 (20-86) |

26±15 (0-50)*** |

||||

| No goal shots | 32±13 (11-50) |

32±9 (16-50) |

28±13 (0-48) |

35±8 (24-54) |

47±24 (0-67) |

42±42 (0-100) |

48±30 (13-100) |

70±37 (0-100) |

41±19 (10-71)** |

51±13 (33-70) |

40±18 (14-80)** |

59±14 (33-86) |

||||

| Offensive fouls | 16±6 (6-27) |

14±8 (3-27) |

16±19 (3-71) |

15±7 (9-34) |

4±11 (0-33) |

0 | 0 | 0 | 1±4 (0-11) |

3±6 (0-14) |

1±3 (0-11) |

2±5 (0-17) |

28±29 (0-67) |

32±35 (0-100) |

27±34 (0-100) |

35±35 (0-100) |

| Lost Posessions | 19±6 (12-30) |

21±8 (11-35) |

18±7 (0-26)* |

25±12 (0-43) |

9±14 (0-33) |

14±38 (0-100) |

11±11 (0-33) |

11±18 (0-50) |

10±8 (0-27) |

7±9 (0-25) |

3±6 (0-17)** |

14±14 (0-33) |

0 | 8±18 (0-50) |

19±26 (0-67) |

24±42 (0-100) |

| Exclusions | 22±5 (16-33)‡ |

24±6 (12-30)‡‡ |

16±7 (0-25) |

20±10 (8-44) |

4±8 (0-22) |

0 | 0 | 2±5 (0-14) |

3±6 (0-17) |

3±4 (0-11) |

1±3 (0-10)** |

1±2 (0-6) |

72±29 (33-100) |

60±30 (0-100) |

54±40 (0-100) |

41±39 (0-100) |

| Penalties | 2±2 (0-6)* |

1±2 (0-5) |

3±3 (0-7)*** |

0 | 1±4 (0-13) |

4±9 (0-25) |

0 | 0 | 1±3 (0-8) |

1±2 (0-6) |

1±4 (0-13) |

1±2 (0-6) |

||||

| Origin of shots (%) | ||||||||||||||||

| Zone 1 | 7±11 (0-33) |

3±4 (0-11) |

7±8 (0-23) |

8±8 (0-27) |

24±40 (0-100) |

8±20 (0-50) |

10±17 (0-50) |

28±36 (0-100) |

14±17 (0-50) |

14±12 (0-30) |

18±10 (0-33) |

19±23 (0-67) |

||||

| Zone 2 | 21±19 (0-58) |

12±8 (0-23) |

14±10 (0-36) |

18±14 (7-54) |

20±34 (0-100) |

8±20 (0-50) |

7±10 (0-25) |

15±21 (0-50) |

8±9 (0-25) |

11±10 (0-33) |

13±13 (0-40) |

14±12 (0-33) |

||||

| Zone 3 | 13±9 (0-24) † |

23±14 (0-44) |

19±12 (0-36) |

18±12 (7-43) |

15±23 (0-50) |

39±38 (0-100) |

8±19 (0-67) |

17±24 (0-50) |

11±14 (0-43) |

15±14 (0-36) |

8±18 (0-60) |

15±18 (0-50) |

||||

| Zone 4 | 13±16 (0-36) |

10±14 (0-38) |

11±7 (0-22) |

12±15 (0-47) |

21±30 (0-71) |

8±20 (0-50) |

25±31 (0-100) |

19±35 (0-100) |

27±16 (0-50)‡‡ |

23±19 (0-67)‡ |

9±10 (0-25) |

14±16 (0-44) |

||||

| Zone 5 | 20±15 (0-44) |

30±19 (0-53) |

27±17 (0-62) |

25±12 (7-50) |

5±12 (0-33)† |

31±40 (0-100) |

17±19 (0-50) |

13±19 (0-40) |

22±16 (0-50) |

24±16 (0-45) |

27±19 (0-60) |

19±19 (0-60) |

||||

| Zone 6 | 26±10 (0-43) |

21±13 (6-47) |

22±13 (0-36) |

19±12 (0-38) |

15±26 (0-67)‡‡ |

6±14 (0-33)* |

32±27 (0-75) |

8±15 (0-33) |

19±14 (0-44) |

12±18 (0-50) |

24±14 (0-43) |

18±16 (0-50) |

||||

| Technical execution of shots (%) | ||||||||||||||||

| Free throw | 18±10 (0-33) |

17±9 (0-11) |

11±8 (0-23) |

14±16 (0-27) |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Drive Shot | 37±13 (22-58)** |

43±18 (11-78) |

47±15 (25-71) |

56±18 (31-88) |

54±35 (0-100) |

67±41 (0-100) |

77±21 (50-100) |

58±42 (0-100) |

59±20 (33-88) |

46±20 (10-82) |

61±19 (30-86) |

60±30 (0-100) |

||||

|

Shot after 1 fake |

16±11 (0-38) |

16±14 (0-44) |

20±8 (10-38) |

13±12 (0-36) |

35±40 (0-100) |

33±41 (0-100) |

14±12 (0-33) |

38±36 (0-100) |

19±13 (0-38)† |

35±19 (9-70) |

30±18 (14-67) |

26±19 (0-67) |

||||

|

Shot after 2 fakes |

9±6 (0-21) |

10±6 (0-22) |

8±8 (0-27) |

7±8 (0-21) |

3±7 (0-17) |

0 | 8±10 (0-25) |

0 | 13±15 (0-38) |

35±19 (0-27) |

30±18 (0-40) |

26±19 (0-40) |

||||

|

Shot after >2 fakes |

7±11 (0-33) |

4±4 (0-11) |

3±4 (0-9) |

3±4 (0-8) |

2±6 (0-17) |

0 | 0 | 0 | 4±8 (0-25) |

5±8 (0-20) |

0 | 2±5 (0-13) |

||||

| Backhand shot | 5±7 (0-17) |

5±5 (0-11) |

5±6 (0-15) |

6±6 (0-20) |

2±6 (0-17) |

0 | 1±3 (0-10) |

0 | 1±4 (0-13) |

0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Off-the-water shot | 8±7 (0-18)** |

5±8 (0-22) |

5±9 (0-27) |

1±3 (0-9) |

4±11 (0-33) |

0 | 0 | 4±12 (0-33) |

4±6 (0-13) |

3±7 (0-20) |

0 | 0 | ||||

†, †† and ††† indicate differences (p < 0.05, 0.01 and 0.001 respectively) with respect to L; ‡, ‡‡ and ‡‡‡ indicate differences (p < 0.05, 0.01 and 0.001 respectively) with respect to MW; *, ** and *** indicate differences (p < 0.05, 0.01 and 0.001 respectively) with respect to ML.

No difference emerged for the occurrence of the even actions ended by means of the forward’s and perimeter players’ game events (Table 3). Nevertheless, differences emerged for the even offensive arrangements (6 versus 6 and 5 versus 5: p < 0.001, ES range = 0.4-0.6; 4 versus 4 and 3 versus 3: p < 0.001, ES range = 0.4-0.5; 2 versus 2 and 1 versus 1: p < 0.001, ES range = 0.4-0.6; Table 3). For the power-play offensive arrangements and roles occurring at the end of action (Table 3), only a difference emerged for the "3-3" offensive arrangement and perimeter player events (p = 0.009). Finally, differences in terms of margin of victory emerged for "pressing" (p < 0.001, ES range = 0.4-0.6), "zone 1-2" (p < 0.001, ES range = 0.6-0.7), and "zone 2-3-4" (p = 0.002, ES range=0.4-0.5) even defensive arrangements, as well as for "cluster" and "anticipating" (p = 0.020) power-play defensive arrangements (Table 3).

Table 3.

Men’s Water Polo World Championship matches. Means, standard deviations, and ranges of the occurrences of the centre forward and perimeter players play events and offensive arrangements, and defensive arrangements, occurring at the end of even and power-play actions, in relation to margin of victory (i.e., W, L, MW, and ML).

| W | L | MW | ML | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centre Forward versus Perimeter Players (%) | ||||

| Even | ||||

| Centre forward | 50±8 (41-59) |

50±11 (32-69) |

54±11 (30-72) |

48±9 (34-64) |

| Perimeter player | 50±8 (41-59) |

50±11 (31-68) |

46±11 (28-70) |

52±9 (36-66) |

| Offensive Arrangements | ||||

| Even | ||||

| 6vs6 and 5vs5 | 92±6 (81-100)** |

96±4 (90-100) ‡‡,*** |

88±9 (70-100) |

84±10 (66-100) |

| 4vs4 and 3vs3 | 5±4 (0-12)* |

3±3 (0-9)*** |

6±5 (0-15) |

10±7 (0-20) |

| 2vs2 and 1vs1 | 3±4 (0-11)* |

1±2 (0-6)*** |

6±7 (0-19)** |

7±5 (0-17) |

| Power-play | ||||

| 4:2/perimeter player | 65±16 (33-89) |

69±15 (50-90) |

64±22 (14-90) |

63±14 (33-78) |

| 4:2/centre forward | 25±10 (11-40) |

23±14 (0-50) |

32±19 (0-71) |

23±14 (0-44) |

| 3:3/perimeter player | 10±11 (0-33) |

7±11 (0-29) |

5±6 (0-14)** |

14±11 (0-33) |

| 3:3/centre forward | 0 | 1±2 (0-8) |

0 | 0 |

| Defensive Arrangment (%) | ||||

| Even | ||||

| “Pressing” | 40±14 (19-70)#,*** |

37±12 (18-55) ‡‡,*** |

52±14 (32-81) |

60±17 (34-83) |

| “Zone 1-2” | 35±10 (19-53)‡‡‡,*** |

43±16 (17-62) ‡‡‡,*** |

16±10 (0-30) |

16±17 (0-52) |

| “Zone M” | 9±7 (0-24) |

6±6 (0-15) |

6±6 (0-21) |

6±6 (0-23) |

| “Zone 2-3-4” | 16±10 (3-31)‡ |

14±9 (3-26)‡‡ |

25±11 (7-42) |

17±12 (3-40) |

| Power-play | ||||

| “cluster” | 93±7 (80-100)* |

88±10 (67-100) |

80±18 (50-100) |

80±21 (33-100) |

| “anticipating” | 7±7 (0-20)* |

12±10 (0-33) |

20±18 (0-50) |

20±21 (0-67) |

‡, ‡‡ and ‡‡‡indicate differences (p < 0.05, 0.01 and 0.001 respectively) with respect to MW; *, ** and *** indicate differences (p < 0.05, 0.01 and 0.001 respectively) with respect to ML.

Discussion

This is the first study that considered technical and tactical aspects of water polo according to the new international rule and a margin of victory. In particular, the in-troducing of the latter factor allowed to investigate the water polo game by means of a higher awareness, to minimize the effect of the situational nature that inevitably makes hard the replication of technical and tactical analyses (Lupo et al., 2010) and, coherently to other team sports (Csataljay et al., 2009; Gómez et al., 2008; Sampaio and Janeira, 2003; Sampaio et al., 2010; Vaz et al., 2010), to define the influence of match outcomes on performance. Nevertheless, in this study, different playing strategies sometimes favored high data heterogeneity (high standard deviations and ranges, and small ESs), even for teams appertaining to the same category of margin of victory.

The main finding of this study showed that the men’s water polo matches of the World Championships are mainly characterized by the divergence between closed and unbalanced games rather than the comparison between winning and losing teams. Thus, it could assume that the game aspects of the elite men’s water polo matches have to be analyzed in relation to specific margins of victory and not only considering the winning and losing outcome.

For even offensive actions, the higher ML’s occurrence with respect to the W and MW ones emerged for effect of a minor frequency of counterattacks, probably due to a low ability to promptly perform the offensive action. In terms of power-play actions, both teams playing closed games (W and L) reported higher occurrences with respect to those of unbalanced game (MW and ML), confirming the importance of this particular game phase, previously highlighted in other studies on elite men’s water polo (Lupo et al., 2007; 2010). The reduced occurrences of the transitions (range: 4-6%) limit any possible explanations on the relative data.

In line to a previous study on elite and sub-elite men’s water polo (Lupo et al., 2010), the shorter duration of the L’s even actions with respect to the W and ML ones could be interpreted in favor of a different grade of ability to maintain ball possessions and to defense. In particular, it could be speculated that W are more able to maintain the ball possession, while ML hardly find good opportunity to score a goal, spending more time to perform action. On the other hand, for power-play, MW showed a shorter duration than that of the ML, W and L, speculating that, during unbalanced games, the winning teams could obtain offensive opportunities to successfully shot (as demonstrated by the goal and "no goal shot" occurrences) after few seconds from the origin of the action.

In terms of scored goals, winning teams showed their supremacy with respect to losing teams especially during even and power-play actions. However, as easily expected, for both goals scored and "no goal shots" indicators, the main divergence emerged between MW and ML, speculating different grade of abilities to create effective offensive playing opportunities as well as to limit opponent play.

Although in previous studies (Lupo et al., 2007; 2010), the best men’s water polo teams achieve high occurrence of opponent exclusions during even action in order to perform a consequent high number of power-play actions, the present data did not show any effect between winning and losing teams, but only between teams playing closed games (W and L) and MW, highlighting how this game phase (i.e., the passage from the exclusion achieved during even actions to the power-play actions) is crucial for team playing matches with small margin of victory. The lost possessions occurring during even and power-play actions, as well as the penalty achieved during even action, showed huge divergences between teams perform-ing unbalanced games, inferring likely for the interpretation of action duration data, divergent offensive abilities to maintain ball possession and defensive skills to steal the opposite ball possession.

The analysis of origin of shots did not display significant effects. However, for each game situation, winning teams showed high values of shots (despite statistically reported only for Counterattacks, between MW and L, and ML) originated from the "zone 6" (i.e., the central zone inside the five-meter area) with respect to losing ones, suggesting that the winnings teams are more able to centrally penetrate inside the five-meter area (rationally considered as the most favorable position to score a goal) and the losing ones are scarcely skilled to defend.

Consistent with the literature (Hughes et al., 2006; Lupo et al., 2010; 2011), the most performed technical execution of shots was drive shot. In particular, it could be inferred that this type of shot provides the best opportunity to end the action quickly, which is useful to limit the opponents defensive counter act.

Nevertheless, for even actions, W reported a significant low occurrence of drive shots and a higher frequency of "off-the-water shot" with respect to ML, determining, therefore, an extended selection of shot executions. Conversely, for power-play actions, the lower occurrence of the W’s shots after 1 fake with respect to the L one could be interpreted according to the latter’s necessity to mislead the goalkeeper (Lupo et al., 2010), instead of ending the action with a quick shot, which seems to be the best play solution considering the related goal and "no goal shot" data (W: goal = 44 ± 17%, "no goal shots" = 41 ± 19; L: goal = 36 ± 11, "no goal shots" = 51 ± 13).

The play events occurring at the end of even actions by centre forward and perimeter players reported quite balanced occurrences, therefore confirming the already highlighted high impact of centre forward for the game of an entire team (Lupo et al., 2007), because the offensive arrangements are mainly characterized by the presence of 5 perimeter players and only one centre forward (Figure 2).

The analysis of the even offensive arrangements showed that the teams performing closed games showed more (>90%) complete offensive arrangements (i.e., 6 or 5 offensive players) than MW (88%) and ML (84%), probably for a divergent technical and tactical, and physical abilities to quickly perform the swimming phases useful to complete an offensive arrangement, within the limit of 30 seconds clock-time of a single ball possession (FINA, 2010). Although, for the power-play offensive arrangement, the 3:3 arrangement ended by perimeter player reported a difference between MW and ML, their low occurrences limit any potential interpretation. However, consistent with previous studies (Hughes et al., 2006; Lupo et al., 2010), the 4:2 arrangement resulted the most adopted Power play offensive arrangement.

Relatively to the defensive arrangement performed during even actions, the high occurrence of the "zone 2" performed during closed games (W and L) showed how in these matches it is important to minimize the opponent centre forward play, which is crucial to obtain an opponent exclusion foul (Lupo et al., 2007; 2008). Conversely, during unbalanced games (MW and ML), the above mentioned defensive strategy was not evident, while "pressing" emerged as the most approved. Coherently to even actions, for the defensive arrangements of power-play, the teams performing the closed games tended to principally cover the opponent players located close to their goal ("cluster" defence) instead of pressing the perimeter players ("anticipating" defence; Figure 3).

Conclusion

Although the situational nature of water polo limit the replication of studies (Lupo et al., 2010), this technical and tactical study tends to promote the knowledge of the elite men’s water polo, promoting the identification of specific training planning (Smith, 1998) for water polo teams and roles, considering the offensive game phases as well as the defensive ones. Therefore, consistent with other studies (Hughes et al., 2006; Lozovina et al., 2004; Lupo et al., 2007; 2008; 2009; 2010; 2011), results from the current study confirms notational analysis as a useful method for better coaching (Hughes and Franks, 2004) through the interpretation of water polo technical and tactical aspects (Lupo et al., 2010), even with particular reference to specific competition levels, margins of victory, game situations and roles.

In this study, discrepancies mainly emerged between closed and unbalanced games, rather than between winning and losing teams, highlighting that the water polo matches of the men’s World Championships need to be analyzed considering successful/unsuccessful teams as well as specific margins of victory. Thus, coaches can improve their knowledge and training, considering, for closed matches, high occurrences of opponent’s exclusion fouls to perform power-play actions, while for unbalanced ones, a divergent grade of defensive skills between teams during each game situation.

Biographies

Corrado Lupo

Employment

University of Rome “Foro Italico”, Italy. Department of Human Movement and Sport Sciences

Degree

PhD

Research interests

Notational analysis, aquatic team sports, teaching and coaching team sports.

E-mail: corrado.lupo@uniroma4.it

Giancarlo Condello

Employment

PhD Student, Department of Human Movement and Sport Sciences, University of Rome “Foro Italico”, Italy

Degree

MSc

Research interest

Agility in field athletes

E-mail: giancarlo.condello@libero.it

Antonio Tessitore

Employment

Associate Professor, Department of Human Movement and Sport Sciences, University of Rome “Foro Italico”, Italy

Degree

PhD

Research interest

Agility in field athletes; Monitoring training fatigue and recovery in team sports; Match Analysis

E-mail: antonio.tessitore@uniroma4.it

References

- Argudo-Iturriaga F.M., Roque J.I.A., Marín P.G., Lara E.R.(2007) Influence of the efficacy values in counterattack and defensive adjustment on the condition of winner and loser in male and female water polo. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport 7(2), 81–91 [Google Scholar]

- Argudo-Iturriaga F.M., Ruiz E., Alonso J.I.(2009)Were differences in tactical efficacy between the winners and losers teams and the final classification in the 2003 water polo world championship? Journal of Human Sport and Exercise 4(2), 142–153 [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J.(1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd edition. Lawrence, Erlbaum, Hillsdale: [Google Scholar]

- Csataljay G., O'Donoghue P., Hughes M., Dancs H.(2009)Performance indicators that distinguish winning and losing teams in basketball. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport <http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/uwic/ujpa;jsessionid=37l9hkt5hmqqc.alice> 9(1), 60–66 [Google Scholar]

- Escalante Y., Saavedra J.M., Mansilla M., Tella V.(2011) Discriminatory power of water polo game-related statistics at the 2008 Olympic Games. Journal of Sports Sciences 229(3), 291–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk B., Lidor R., Lander Y., Lang B.(2004) Talent identification and early development of elite water-polo players: A 2-year follow-up study. Journal of Sports Sciences 22(4), 347–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federation Internationale De Natation (2010) Water polo rules Available from URL: http://www.fina.org/H2O/index.php?option= com_content&view=category&id=85:water-polo-rules&Itemid=184&layout=default Retrieved on November 17, 2010

- Gómez M.A., Lorenzo A., Sampaio J., Ibáñez S.J., Ortega E.(2008) Game-related statistics that discriminated winning and losing teams from the Spanish men's professional basketball teams. Collegium Antropol ogicum 32(2), 451–456 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M., Appleton R., Brooks C., Hall M., Wyatt C.(2006)Notational analysis of elite men's water-polo. In: 7th World Congress of Performance Analysis of Sport. July 23-26, Szombathely-Hungary: Book of abstract 275–298 [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M., Franks I.(2004) Notational analysis of sport: Systems for better coaching and performance in sport. 2nd edition Routledge, London [Google Scholar]

- Lozovina V., Pavicic L., Lozovina M.(2004) Analysis of indicators of load during the game in the activity of the center in water polo. Nase More 51, 135–141 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupo C., Tessitore A., Cortis C., Ammendolia A., Figura F., Capranica L.(2009) A physiological, time-motion, and technical comparison of youth water polo and Acquagoal. Journal of Sports Sciences 27(8), 823–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupo C., Tessitore A., Cortis C., Perroni F., D'Artibale E., Capranica L.(2007)Elite water polo: A technical and tactical analysis of the centre forward role. In: Book of abstract of 12th European College of Sport Sciences. July 11-14, Jyväskylä, Finland: 468 [Google Scholar]

- Lupo C., Tessitore A., King B., Capranica L.(2008)American women's collegiate water polo: A technical and tactical analysis of the centre forward role. In: Book of abstract of 13th European College of Sport Sciences. July 9-12, Estoril, Portugal: 212 [Google Scholar]

- Lupo C., Tessitore A., Minganti C., Capranica L.(2010) Notational analysis of elite and sub-elite water polo matches. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 24(1), 223–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupo C., Tessitore A., Minganti C., King B., Cortis C., Capranica L.(2011) Notational analysis of American women's collegiate water polo matches. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 25(3), 753–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melchiorri G., Manzi V., Padua E., Sardella F., Bonifazi M.(2009)Shuttle swim test for water polo players: validity and reliability. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness 49(3), 327–330 <http://journalseek.net/cgi-bin/journalseek/journalsearch.cgi?field=issn&query=0022-4707> [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mujika I., Mcfadden G., Hubbard M., Royal K., Hahn A.(2006) The water-polo intermittent shuttle test: A match-fitness test for waterpolo players. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 1(1), 27–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlik G., Kemeny D., Kneffel Z., Petrekanits M., Horvàth P., Sido Z.(2005) Echocardiographic data in Hungarian top-level water polo players. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 37(2), 323–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platanou T.(2006) Simple 'in-water' vertical jump testing in water polo. Kinesiology 38(1), 57–62 [Google Scholar]

- Platanou T., Geladas N.(2006) The influence of game duration and playing position on intensity of exercise during match-play in elite water polo players. Journal of Sports Sciences 24(11), 1173-1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platanou T., Grasso G., Cufino B., Giannouris Y.(2007)Comparison of the offensive action in water polo games with the old and new rules. In: Book of abstract of 12th European College of Sport Sciences. July 11-14, Jyväskylä, Finland: 576 [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio J., Janeira M.(2003)Statistical analyses of basketball team performance: understandings teams wins and losses according to a different index of ball possessions. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport <http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/uwic/ujpa;jsessionid=37l9hkt5hmqqc.alice> 3(1), 40–46 [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio J., Drinkwater E.J., Leite N.(2010) Effects of season period, team quality, and playing time on basketball players' game-related statistics. European Journal of Sport Science 10(2), 141–149 [Google Scholar]

- Sardella F., Alippi B., Rudic R., Castellucci G., Bonifazi M.(1992) Analisi fisiometabolica della partita. Tecnica Nuoto 19, 21–24 [Google Scholar]

- Smith H.K.(2004) Penalty shot importance, success and game context in international water polo. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 7(2), 221–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith H.K.(1998) Applied physiology of water polo. Sports Medicine 26(5), 317–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan F., Polglaze T., Dawson B.(2009) Activity profiles and physical demands of elite women's water polo match play. Journal of Sports Sciences 27(10), 1095-1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsekouras Y.E., Kavouras S.A., Campagna A., Kotsis Y.P., Syntosi S.S., Papazoglou K., Sidossis L.S.(2005) The anthropometrical and physiological characteristics of elite water polo players. European Journal of Applied Physiology 95(1), 35–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaz L., Van Rooyen M., Sampaio J.(2010) Rugby game-related statistics that discriminate between winning and losing teams in IRB and Super twelve close games. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine 9, 51–55 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vila M.H., Abraldes A.J., Alcaraz P.E., Rodríguez N., Ferragut C.(2011)Tactical and shooting variables that determine win or loss in top-Level in water polo. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport <http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/uwic/ujpa;jsessionid=37l9hkt5hmqqc.alice> 11(3), 486–498 [Google Scholar]