Abstract

Inverse paralogous low-copy repeats (IP-LCRs) can cause genome instability by nonallelic homologous recombination (NAHR)-mediated balanced inversions. When disrupting a dosage-sensitive gene(s), balanced inversions can lead to abnormal phenotypes. We delineated the genome-wide distribution of IP-LCRs >1 kB in size with >95% sequence identity and mapped the genes, potentially intersected by an inversion, that overlap at least one of the IP-LCRs. Remarkably, our results show that 12.0% of the human genome is potentially susceptible to such inversions and 942 genes, 99 of which are on the X chromosome, are predicted to be disrupted secondary to such an inversion! In addition, IP-LCRs larger than 800 bp with at least 98% sequence identity (duplication/triplication facilitating IP-LCRs, DTIP-LCRs) were recently implicated in the formation of complex genomic rearrangements with a duplication-inverted triplication–duplication (DUP-TRP/INV-DUP) structure by a replication-based mechanism involving a template switch between such inverted repeats. We identified 1,551 DTIP-LCRs that could facilitate DUP-TRP/INV-DUP formation. Remarkably, 1,445 disease-associated genes are at risk of undergoing copy-number gain as they map to genomic intervals susceptible to the formation of DUP-TRP/INV-DUP complex rearrangements. We implicate inverted LCRs as a human genome architectural feature that could potentially be responsible for genomic instability associated with many human disease traits.

Keywords: segmental duplications, inverted repeats, genomic inversions, MMBIR

Introduction

Low-copy repeats (LCRs), or segmental duplications [Bailey et al., 2001], constitute approximately 4–5% of the human genome. LCRs >5–10 kB in size, with >95–97% DNA sequence identity, and located <10 MB apart can lead to localized genomic instability via nonallelic homologous recombination (NAHR) [Lupski 1998; Stankiewicz and Lupski 2002]. Recently, it has been observed that LCR length correlates with the frequency of the rearrangements in the germline consistent with ectopic synapsis mediating NAHR [Liu et al., 2011].

Using bioinformatic approaches, Sharp et al. (2005) predicted the genome-wide occurrence of potential genomic rearrangements mediated by directly oriented paralogous LCRs via NAHR. To date, approximately 40 of these rearrangements, resulting from meiotic NAHR have been described to manifest as genomic disorders, microdeletion, and microduplication syndromes [Liu et al., 2012; Vissers and Stankiewicz 2012].

In contrast, only two pathogenic inversions, both mapping to chromosome Xq28 and flanked by inversely oriented paralogous LCRs (IP-LCRs) have been reported despite two decades passing since the landmark finding of Gitschier and colleagues that a single inversion disrupting the factor VIII gene (F8) accounts for >45% of patients with severe hemophilia A (MIM# 306700). In 90% of the inversion-mediated hemophilia A cases, NAHR occurs between the 9.5 kB LCR int22h-1 located in intron 22 and the inverted int22h-2 or int22h-3 LCRs mapping 600 kB or 500 kB upstream to F8, respectively [Lakich et al., 1993; Naylor et al., 1992, 1993, 1995]. In the remaining 10% of patients with inversion-mediated hemophilia A, the NAHR site is in intron 1 and affects a 1041-bp sequence called int1h-1, which has a duplicated copy in inverted orientation (int1h-2) located 140 kB distally [Bagnall et al., 2002]. Approximately, 13% of patients with mucopolysaccharidosis type II (Hunter syndrome; MIM# 309900) have been found to have the IDS gene disrupted by an NAHR-mediated inversion between the 1.6 kB LCR in intron 7 of the IDS gene and its telomeric IDS2 pseudogene of 95.97% sequence identity [Bondeson et al., 1995]. In addition, based on the predicted breakpoint products for rearrangements between highly identical inverted repeated sequences, Flores et al. (2007) found evidence for LCRs/NAHR-mediated inversions occurring in somatic cells at low frequencies yet detectable by PCR.

Approximately, 2% of the haploid human genome shows 100% DNA sequence identity [Zepeda-Mendoza et al., 2010]. It was shown that these identical regions overlap with almost 80% of the known copy-number variants (CNVs), suggesting that a high percent of DNA identity predisposes to NAHR and contributes to the formation of both polymorphic and pathogenic CNVs. In addition, complex genomic rearrangements (CGRs) constituted by both copy-number gains and inversions can occur at a high frequency; they can be observed in up to 20% of gains at some disease-associated X-chromosome loci such as MECP2. These CGRs can be mediated by duplication/triplication facilitating IP-LCRs (DTIP-LCRs) in the human genome [Carvalho et al., 2011].

In aggregate, these findings implicate inverted repeats as a genomic architectural feature rendering susceptibility to genomic instability through either mediating, by NAHR, or facilitating, through a template switching mechanism such as fork stalling and template switching (FoSTeS)/microhomology-mediated break-induced replication (MMBIR) [Hastings et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2007] the formation of structural variation in the human genome.

Here, we report the genome-wide distribution of IP-LCRs and DTIP-LCRs, and intersect their location with positional genome mapping information of all human genes. Finally, focusing on dosage sensitive and other known disease genes, we describe the potential role for inverted repeat mediated or facilitated genome instability in causing human disease traits.

Materials and Methods

Identification of Inverted Paralogous Low-Copy Repeats

The set of IP-LCRs was generated using a whole-genome assembly comparison approach [Bailey et al., 2001]. From the set of all LCRs (GRCh37, February 2009), we selected the subset of IP-LCRs that satisfy the following criteria: sequence identity (calculated using a fraction matching parameter that examined for the percent identity between the inverted repeat pair studied) at least 95%, less than 10 MB distance between elements, and a minimal element length of 1 kB. The thresholds fixed for sequence identity and the maximal distance between elements are commonly used in the literature for regions prone to NAHR-mediated deletions and duplications [Liu et al 2012; Sharp et al 2005]. The parameter for the minimal LCR length is a result of the limitation of the Segmental Dups track used to generate the set of IP-LCRs.

Database of Genomic Variants Inversions

We compared the IP-LCR genome architecture with the apparently benign genome-wide structural variants identified in healthy controls deposited in the Database of Genomic Variants (DGV) (http://projects.tcag.ca/variation/) [Zhang et al., 2006]. It should be noted that DGV contains a significant fraction of false positive genomic rearrangements due to the limited genome resolution of the various platforms and technologies used mainly in the initial studies that populated the database. Moreover, as a consequence of technical limitations, sizes of smaller genomic rearrangements reported in DGV are unreliable often because genomic rearrangements were detected using relatively poor-resolution technologies that under-or overestimate the boundaries [Koolen et al., 2009]. Thus, before testing correlations between inversion sizes and other parameters, we parsed out the rearrangements smaller than 10 kB. Interestingly, 917 of 925 inversions were detected either by DNA sequencing (N = 361) or paired end mapping (PEM) (N = 556). The rearrangements captured by PEM are significantly longer (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test; P value <0.01) than others (Supp. Fig. S1) and more often correspond to recurrent inversions; that is, elements in DGV that overlap with each other.

Genes Located in IP-LCR Regions

The inversion rearrangements mediated by the IP-LCR pairs via NAHR can disrupt gene function and have potential phenotypic consequences when the rearrangement affects dosage-sensitive genes [Huang et al., 2010] or their regulatory elements located in the involved genomic interval. Therefore, we identified all IP-LCRs overlapping RefSeq genes and, in particular, dosage-sensitive genes, in which disrupting inversion rearrangements can convey a phenotype [Boone et al., 2010]. We also attempted to assign a disease phenotype to the identified genes by exploring the Genetic Association Database (GAD) [Zhang et al., 2010], an archive of human genetic association studies of complex diseases and disorders allowing for rapid identification of medically relevant polymorphisms.

Identification of Inverted Repeated Sequences in the Human Genome that Can Lead to DUP-TRP/INV-DUP Structures

Due to their association with facilitating complex duplication– triplication rearrangements, we also were interested in examining the genome-wide distribution of such potential inverted repeat structures. We computationally generated a set of DTIP-LCRs based on the methodology described by Flores et al. (2007) and Zepeda-Mendoza et al. (2010) using the sequence identity, length, and distance parameters delineated from the empirically derived experimental observations in Carvalho et al. (2011). We identified all 100% identical repeated sequences of inverted orientation with a minimum length of 145 bp in the human genome using the RE-Puter program family [Kurtz et al., 2001]. We used such inverted repeated sequences as seeds to extend and merge into larger regions or tracks of >98% of sequence identity. These repeated tracks were then filtered by size to those larger than 800 bp and separated by 30–350 kB, consistent with parameters derived from previous experimental observations [Carvalho et al., 2011]. Repeated sequences were merged and analyzed using custom-formulated Perl scripts.

Identification of Genes Susceptible to DUP-TRP/INV-DUP Rearrangements

We compared all RefSeq genes to our dataset of DTIP-LCRs to identify genes located upstream, downstream, or in between a pair of inverted tracks and up to 1 MB upstream or downstream, parameters that were again based on experimental observations of DUP-TRP/INV-DUP rearrangements. In addition, we compared our DTIP-LCRs using the distance criteria previously described to a list of 5,335 disease-associated genes.

Results

The Genome-Wide Inverted Paralogous-LCR Landscape

Our objective was to investigate the intersection of the IP-LCRs and genes that could be disrupted by genomic inversions via NAHR. We fixed the minimal length of IP-LCRs to 1 kB utilizing the original Segmental Dups UCSC track (see section “Materials and Methods” for details). We delineated 2,805 IP-LCRs with DNA sequence identity between paralogous genomic segments, or fraction matching, above a threshold of 90%, 1,337 IP-LCRs with the DNA sequence fraction matching above 95%, and 915 IP-LCRs with the fraction matching above 97% (Fig. 1).

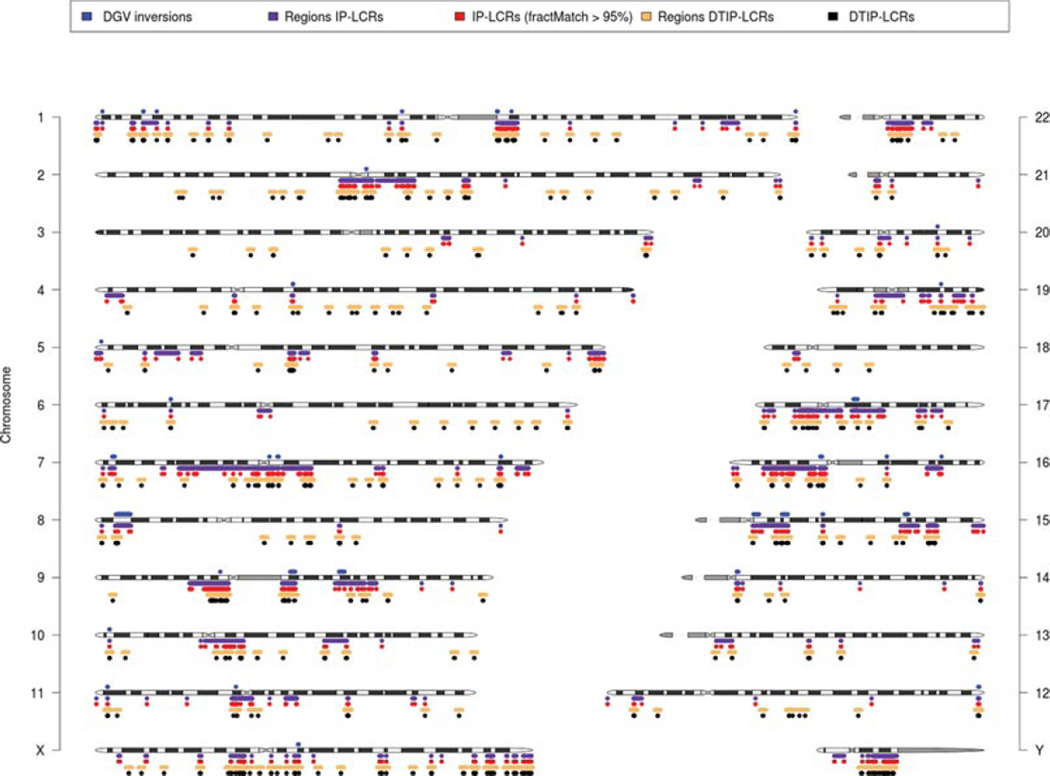

Figure 1.

Ideogram of the human chromosomes showing distribution of known benign inversions (DGV) potentially mediated by IP-LCRs (above chromosomes) and genomic regions flanked by IP-LCR (and potentially susceptible to genomic instability via NAHR inversions), DTIP-LCRs with 1 MB flanking segments and regions occupied by IP-LCRs and DTIP-LCRs (below chromosomes). The blue track depicts 47 inversions found in the DGV database with both breakpoints mapping within IP-LCRs. In violet are genomic regions flanked by 1,337 IP-LCRs greater than 1-kB in size of 95% sequence identity and in red IP-LCRs. The black track (below IP-LCRs) highlights predicted DTIP-LCRs genomic regions and the yellow track shows DTIP-LCRs with 1 MB flanking regions.

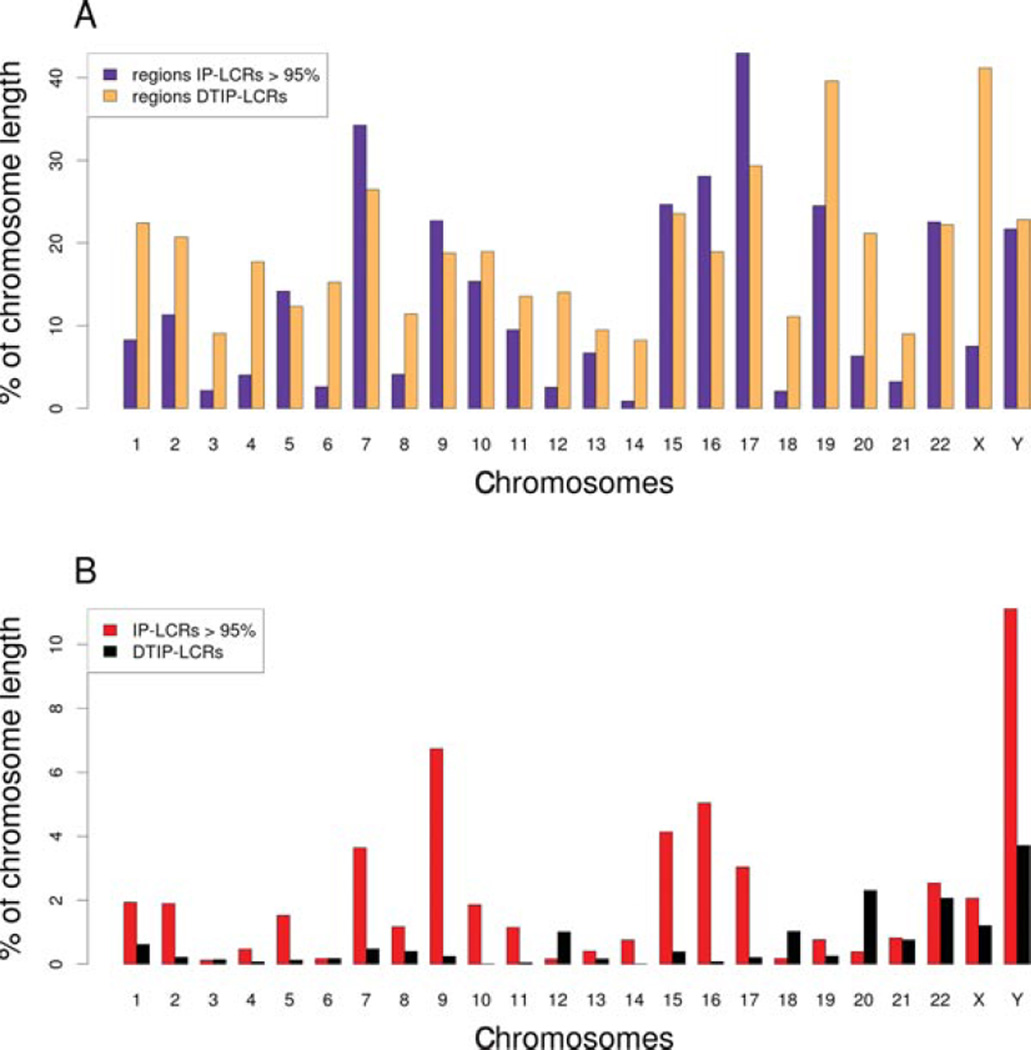

For further studies, we focused on the set of 1,337 IP-LCRs with the paralogous fraction matching >95%. The overall length of DNA regions flanked by these IP-LCRs, and thus potentially susceptible to genomic instability via NAHR inversions, is 372.6 MB (12.0% of the human genome), including the IP-LCRs fraction size (59 MB, 1.93%) (Fig. 2A). Of note, 43% of chromosome 17 is flanked by IP-LCRs and chromosome Y is the most IP-LCR rich (>11.1%) (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

A: Chromosome percent coverage of genomic regions flanked by 1,337 IP-LCRs greater than 1-kB in size of 95% sequence identity and mapping <10 MB apart from each other (violet) and DTIP-LCRs with 1 MB flanking regions (yellow), representing potential genome instability regions. B: Chromosome percent coverage, of IP-LCRs (red) and DTIP-LCRs (black). Note that ~43% of chromosome 17 is flanked by IP-LCRs (A) and chromosome Y is the most IP-LCR rich (>11.1%) (B).

Genome-Wide Analysis of the Reported Benign Inversions

In the DGV, we found evidence for 587 DGV inversions longer than 10 kB; 47 of them have both breakpoints intersecting with at least one IP-LCR pair (Fig. 1, Supp. Table S1). To evaluate the statistical significance of such events we have estimated P values that random inversion of given length have breakpoints within a corresponding pair of IP-LCR elements (all P values are below the 0.05 threshold).

Candidate Genes Potentially Disrupted by IP-LCR-Mediated Inversions

After intersecting 1,337 IP-LCRs with the map positions of Ref-Seq genes, we found 942 genes that can be disrupted by the inversion breakpoints (Supp. Table S2 and Supp. Fig. S2). Among them are eight genes fulfilling dosage-sensitive criteria as determined by Huang et al. (2010): ABCC6, FKBP6, GTF2I, NCF1, PRODH, RTN4R, STAT5A, and STAT5B. Thirty-one genes have been associated with different diseases or syndromes (Table 1). Of note, one of them, CFC1, has two distinct isoforms (chr2:131,278,835-131,285,583 on the + strand and chr2:131,350,334-131,357,082 on the – strand) that intersect with specific IP-LCR consisting of two overlapping parts (chr2:131,200,001–131,426,704 [226,704 bp in size] and chr2:131,207,520–131,436,670 [229,151 bp in size]).

Table 1.

Known Disease Genes Overlapping with IP-LCRs

| Gene | Gene description | Location | Intersection with LCR size (size of entire LCR) (kB) |

LCR identity% | Disease | Inheritance | OMIM | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCC6 | ATP-binding cassette, subfamily C (CFTR/MRP), member 6 |

16pl3.11 | 25 (128) | 99.36 | Pseudoxanthoma elasticum | AR | 264800 | [Bergen et al. 2000; Le Saux et al. 2000] |

| AKR1C2 | Aldo-keto reductase family 1, member C2 | 10pl5.1 | 28 (47.5) | 95.15 | 46, XY sex reversal 8 | AR | 614279 | (Fluck etal. 2011) |

| BCR | Breakpoint cluster region | 22qll.23 | 7 (10.5), 4 (7) | 95.98, 96.17 | Chronic myeloid leukemia | – | 608232 | [Hermans et al. 1987] |

| CFC1 | Cripto, FRL-1, cryptic family 1 | 2q21.1 | 7 (227), 7 (229) | 99.27, 99.27 | Visceral heterotaxy-2 (HTX2), (a congenital heart disease, identified in patients with transposition of the great arteries and double-outlet right ventricle) |

AD | 605376 | [Bamford et al. 2000; Goldmuntz et al. 2002; Ozcelik et al. 2006; Roessler et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2011] |

| CHRNA7 | Cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, alpha 7 (neuronal) |

15ql3.3 | 17 (307) | 99.62 | Chromosome 15ql3.3 deletion syndrome | AD | 612001 | [Flomen et al; 2008; Masurel-Paulet et al. 2010; Sharp et al. 2008; Shinawi et al. 2009; Szafranski et al. 2010] |

| CNTNAP3 | Contactin-associated protein-like 3 | 9pl3.1 | 5 (208), 55 (115), 130 (155), 64 (64), 22 (49) |

99.29, 98.72, 98.49, 98.3, 98.2 |

Candidate gene for bipolar disorder and bladder exstrophy |

? | N/A | (Boyadijev et al. 2005; Palo et al. 2010] |

| DPP6 | Dipeptidyl-peptidase 6 | 7q36.2 | 105 (105), 110 (110) | 98.4, 98.42 | Paroxysmal familial ventricular fibrillation 2 (VF2) |

AD | 612956 | [Alders et al. 2009; Radicke et al. 2005;) |

| DUOX2 | Dual oxidase 2 | 15q21.1 | 1 (1) | 97.46 | Congenital hypothyroidism Thyroid Dyshormonogenesis 6 (TDH6) |

AR | 607200 | [Moreno et al. 2002; Vigone et al. 2005] |

| FANCC | Fanconi anemia, complementation group C | 9q22.32 | 3 (3) | 95.98 | Fanconi anemia, complementation group C | AR | 227645 | [Gavish et al. 1992; Strathdee et al. 1992] |

| FLNC | Filamin C | 7q32.1 | 3 (3) | 96.4 | Myofibrillar myopathy, Distal myopathy 4 | AD | 609524; 614065 | [Duff et al. 2011; Vorgerd et al. 2005] |

| GTF2I | General transcription factor IIi | 7qll.23 | 33 (144) | 99.67 | Williams-Beuren syndrome critical region, responsible for autism spectrum disorders |

AD | 194050 | [Malenfant et al. 2012; Sakurai et al. 2011] |

| HERC2 | HECT and RLD domain containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 2 |

15ql3.1 | 4 (4), 47 (47), 1 (1), 34 (34), 6 (103) |

95.04, 97.31, 96.12, 97.07, 99.61 |

Juvenile development and fertility 2 (jdf2), skin/hair/eye pigmentation |

AD? | 227220 | [Kayser et al. 2008; Ji et al. 2000; Sturm et al. 2008; Sulem et al. 2007] |

| KRTS1 and KRTS6 | Keratin 81 and keratin 86 | 12ql3.13 | 4 (4) | 97.72 | Monilethrix | AD | 158000 | [Pearce et al. 1999; Winter et al. 1997, 2000] |

| NCF1 | Neutrophil cytosolic factor 1 | 7qll.23 | 15.3 (144) | 99.67 | Chronic granulomatous disease | AR | 233700 | [Casimir et al. 1991; Gorlach et al. 1997; Noack et al. 2001; Roesler et al. 2000; Volpp et al. 2005) |

| NQO2 | NRH:quinone oxidoreductase-2 | 6p25.2 | 2 (2) | 96.95 | Breast cancer | – | 114480 | [Yu et al. 2009] |

| OCLN | Occludin | 5ql3.2 | 24 (79) | 99.67 | Band-like calcification with simplified gyration and polymicrogyria (BLCPMG) |

AR | 251290 | [O’Driscoll et al. 2010] |

| PLEKHM1 | Pleckstrin homology domain-containing protein, family M, member 1 |

17q21.31 | 3 (3) | 95.79 | Osteopetrosis, autosomal recessive 6 | AR | 611497 | [van Wesenbeeck et al. (2007) |

| PRODH | Proline dehydrogenase | 22qll.21 | 12 (23); 2 (2) | 95.83, 96.37 | Hyperprolinemia type 1, Schizophrenia | AD | 239500; 600850 | [Bender et al. 2005; Jacquet et al. 2002] |

| RANBP2 | RAN binding protein 2 | 2ql2.3 | 52 (52), 52 (52), 52 (52) | 97.59, 97.62, 97.67 | Acute necrotizing encephalopathy (ANE1) | AD | 608033 | [Lonnqvist et al. 2011; Neilson et al. 2009] |

| RHCE and RHD | Rh blood group, CcEe antigens | lp36.11 | 58 (63) and 57 (61) | 98.07 | RH-null disease | AD | 268150 | [Huang et al. 1998] |

| RTN4R | Reticulon 4 receptor | 22qll.21 | 6 (28) | 95.84 | Susceptibility to schizophrenia | AD | 181500 | [Sinibaldi et al. 2004] |

| SBDS | Shwachman–Bodian–Diamond syndrome | 7qll.21 | 8 (46) | 96.77 | Shwachman–Bodian–Diamond syndrome, Paragangliomas 5 |

AR | 260400 | [Boocock et al. 2003] |

| SDHA | Succinate dehydrogenase | 5pl5.33 | 0.5 (5), 21 (24) | 96.18, 95.65 | Leigh syndrome | AR | 256000 | [Bourgeron et al. 1995; Burnichon et al. 2010] |

| SORD | Sorbitol dehydrogenase | 15q21.1 | 4 (4), 18 (18), 17 (25) | 95.07, 97.31, 97.86 | Deficiency in a family with congenital cataracts |

N/A | N/A | [Shin et al. 1984] |

| SPECC1L | Sperm antigen with calponin homology and coiled-coil domains 1-like |

22qll.23 | 5 (5), 5 (5) | 97.06, 96.91 | Oblique facial clefting-1 (OBLFC1) | AD | 600251 | [Saadi et al. 2011] |

| SPTLC1 | Serine palmitoyltransferase, long-chain base unit 1 |

9q22.31 | 11 (11) | 96.68 | Neuropathy, hereditary sensory and autonomic, type 1, severe |

AD | 162400 | [Dawkins et al. 2001] |

| STAT5B | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 5B |

17q21.2 | 4 (4) | 97.4 | Growth hormone insensitivity with immunodeficiency |

AR | 245590 | (Kofoedetal. 2003) |

| TAF1 | TAF1 RNA polymerase II, TATA box binding protein (TBP-associated factor, 250 kDa) |

Xql3.1 | 3 (3) | 99.84 | Dystonia 3, Torsion, X-linked (DYT3) | X-linked | 314250 | [Makino et al. 2007] |

| TMLHE | Trimethyllysine hydroxylase, epsilon | Xq28 | 16 (51), 1 (1) | 99.92, 96.06 | New error of carnitine metabolism | X-linked | N/A | [Celestino-Soper et al. 2011] |

To examine for potential disease associations for other genes, we used the GAD (http://geneticassociationdb.nih.gov) resource. The distribution among the different disease classes for genes potentially disrupted by the rearrangements mediated using IP-LCRs as NAHR substrate pairs does not reveal any highly predominant disease class (Supp. Fig. S3). Finally, we found that by reducing IP-LCRs fraction matching to 94%, we identified an additional 101 intersecting genes.

DTIP-LCRs Rendering Susceptibility to Complex Genomic Rearrangements

Triplications embedded in duplications represent CGRs that are observed in at least 20% of the rearrangements involving MECP2 copy-number gain [Carvalho et al., 2009, 2011]. We experimentally demonstrated that inverted repeats of between 856 bp and 11.3 kB in length, with at least 98% sequence identity, and separated by genomic distances between ~38 and ~318 kB, can facilitate the formation of CGRs at the MECP2 locus [Carvalho et al., 2011]. Remarkably, each of these CGR products share the common genomic organization of an inverted triplicated segment located between directly oriented duplicated genomic segments (duplication-inverted triplication–duplication designated herein as DUP-TRP/INV-DUP). We hypothesized that DTIP-LCRs may foster genomic instability and facilitate formation of such CGRs in other regions of the human genome. Indeed, DTIP-LCR substrate pairs and disease associated DUP-TRP/INV-DUP rearrangements have also been observed to occur at the PLP1 locus at Xq22 [Carvalho et al., 2011; Shimojima et al., 2012].

In the present work, we applied the empirically derived experimental observations from our locus-specific studies as parameters or “rules” to perform a genome-wide computational analysis of the human genome and determine the distribution of the inverted repeats fulfilling these predefined criteria (see section “Materials and Methods”). Remarkably, we identified 1,551 such DTIP-LCRs distributed throughout the human genome (Figs. 1 and 2; Supp. Table S3). On the basis of previous studies and observations at the MECP2 and PLP1 loci, we observed that copy-number gain of genes can be the result of duplication and DUP-TRP/INV-DUP rearrangements mediated by such DTIP-LCRs. Therefore, we determined all the genes in proximity to our bioinformatically predicted set of DTIP-LCRs that might consequently be susceptible to this CGR mutational mechanism; the CGR could result in copy-number gain or breakpoint disruption of such genes. We found from our genome-wide computational analysis that 5,644 nonredundant genes map within 1 MB upstream or downstream or in between any given pair of our DTIP-LCRs, with some of the genes being flanked both upstream and downstream or containing DTIP-LCRs within (Supp. Tables S4-1, S4-2). Of these, 1,445 represent genes that have been previously associated with disease (OMIM, http://www.omim.org) (Supp. Tables S4 and S3). Interestingly, 673 of these “at risk” genes map to the X chromosome, of which 626 are known disease genes.

Discussion

Bioinformatic analyses of the genome-wide distribution of inverted repeats, both IP-LCRs and DTIP-LCRs, reveal that a substantial portion of the human genome is potentially susceptible to genomic instability either directly mediated or facilitated by such inverted repeats (Figs. 1 and 2). Intersection of these inverted repeat structures with positional map information for genes suggests that many genes could be either disrupted, through inversion-mediated gene disruption, or have their dosage changed, resulting from either a duplication or triplication rendered by nearby inverted repeats.

LCRs Mediating Inversions versus Deletions and Reciprocal Duplications

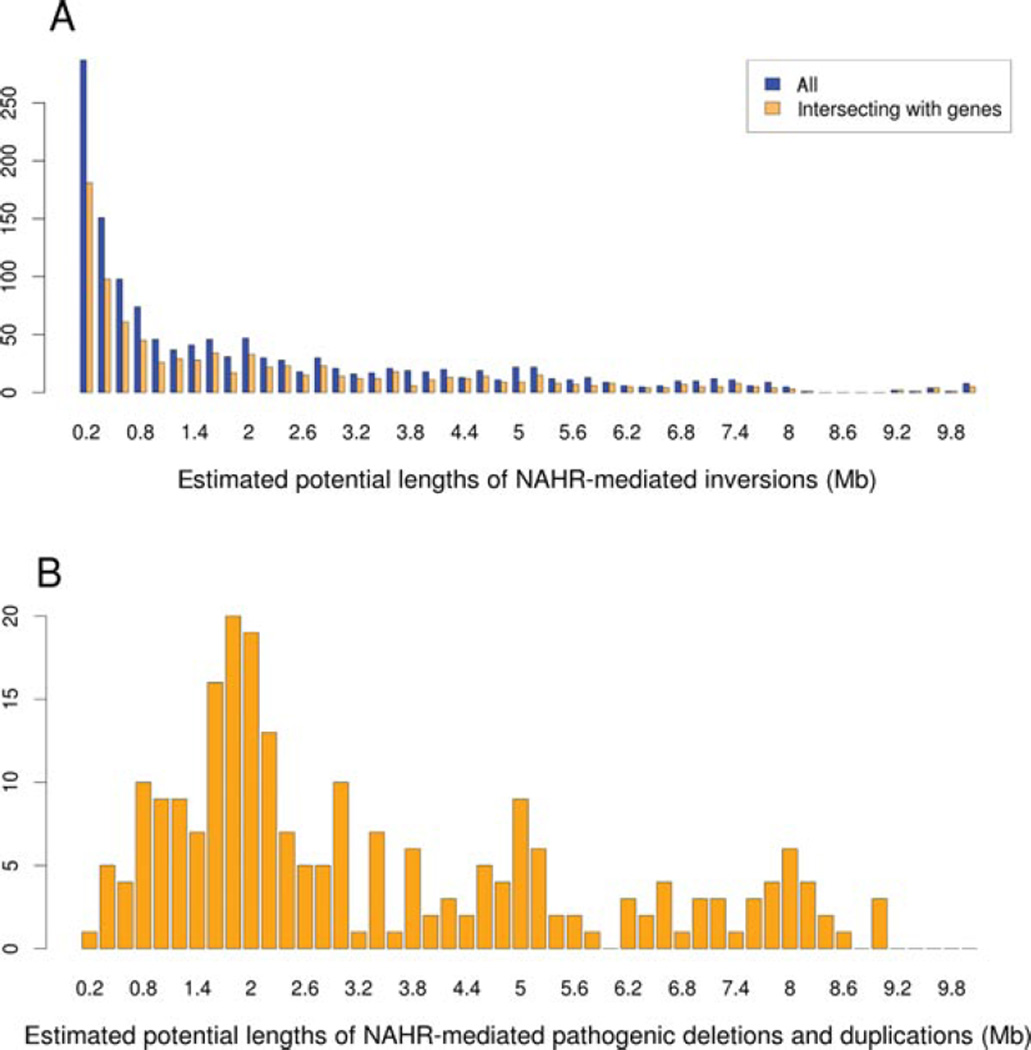

The majority of NAHR-mediated pathogenic deletions and reciprocal duplications (inter- and intrachromosomal) characterized to date at ~40 genomic regions utilize directly oriented LCRs greater that 9–10 kB in size separated by a distance of between 1 to 10 MB. Interestingly, over 56.3% of the paralogous gene-overlapping IP-LCRs that can potentially mediate inversions (intra-chromosomal), including two known pathogenic inversions disrupting F8 and IDS, are located less than 1.5 MB away from each other (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Distributions of estimated lengths of LCR-mediated NAHR rearrangements. The length was calculated as a sum of a unique distance between LCRs pairs plus the size of a shorter LCR element. A: Blue bars depict the frequencies of distances between paralogous elements in the set of IP-LCRs satisfying the defined criteria, that is, fraction matching >95% and maximal distance <10 MB. Yellow bars refer to he distribution of distances in the subset of IP-LCRs intersecting human genes. B: Distributions of directly oriented paralogous LCRs (fraction matching >95%, distance between LCRs <10 MB, LCR size >1 kB) intersecting with both breakpoints of known pathogenic deletions and reciprocal duplications. Note that, in contrast to directly oriented LCRs, the majority of IP-LCRs inversions are between paralogous elements mapping <1.5 MB from each other.

IP-LCRs and Potential NAHR-Mediated Pathogenic Inversions

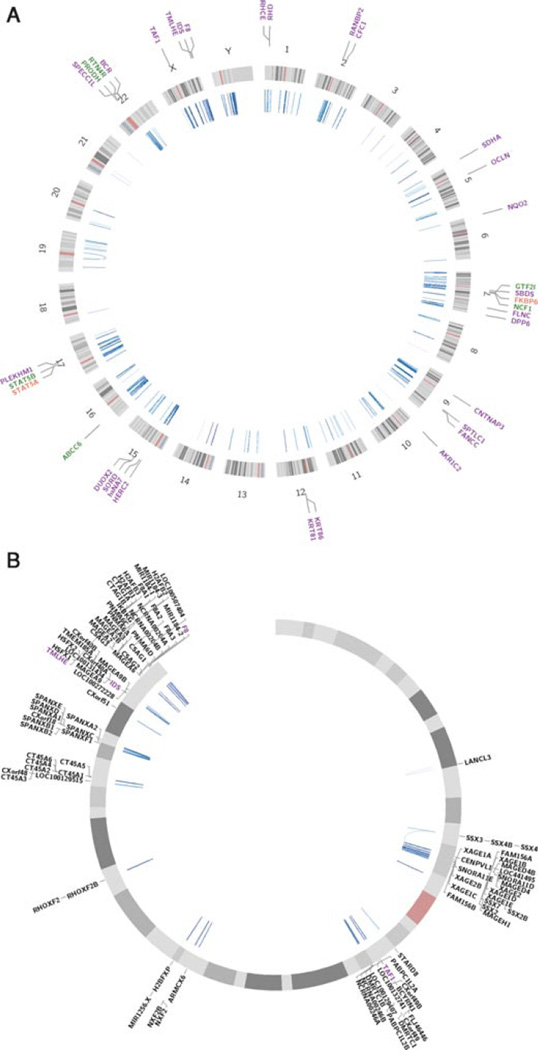

Of the 942 genes potentially disrupted by IP-LCR-mediated inversions identified from our analyses (Supp. Table S2), eight (ABCC6, FKBP6, GTF2I, NCF1, PRODH, RTN4R, STAT5A, and STAT5B) are considered dosage sensitive (Fig. 4A) and thus, are more likely to manifest an abnormal phenotype secondary to a heterozygous, inversion-mediated disruption allele [Huang et al., 2010]. Further, 99 of these genes (10.5%) map to chromosome X (Fig. 4B), consistent with the previous findings that the X chromosome is one of the most IP-LCR-rich chromosomes second only to the Y chromosome which essentially represents one large inverted repeat within an inverted repeat structure [Lange et al., 2009; Warburton et al., 2004]. These X-linked genes are potentially disease causing in males when inactivated. Thus, these represent excellent candidate genes to investigate for potential inversion in males with unexplained mental retardation.

Figure 4.

Circos plots showing the location of IP-LCRs (fraction matching above 95%) and intersected genes. Each blue line inside the circle connects chromosomal locations of the IP-LCR paralogous genomic segments. Light–dark scale of this blue color refers to the ascending fraction matching (from 95% to 100%) between repeats. Genes that intersect with at least one IP-LCR are depicted outside the circles. (A) genome-wide and (B) X chromosome IP-LCR architecture across the entire genome shown with dosage-sensitive genes (red), known disease-causing genes (violet), and genes belonging to both classes (green). Each plot was made using the Circos tool [Krzywinski et al., 2009].

In addition, from genome-wide analysis of potential IP-LCR mediated inversions that intersect genes, 31 genes are disease-causing (listed in OMIM) via mechanisms other than IP-LCR mediated inversions due to NAHR (Table 1, Fig. 4A). Therefore, we propose that the IP-LCRs/NAHR mechanism should be considered during genetic testing to examine for disease associated genetic variation. Inversions that disrupt one of these 31 genes could lead directly to a dominant disease trait or represent a carrier allele for a recessive trait.

Inversions Predisposing to Deletions and Duplications

IP-LCRs can also lead to genomic instability by mediating inversion polymorphisms that now result in directly oriented repeats, which can subsequently predispose these genomic regions to recurrent deletions or reciprocal duplications [Lupski, 2006]. Such events have been described for incontinentia pigmenti with LAGE1-LAGE2A–mediatedinversionspredisposingtoIKBKB(NEMO)deletions [Aradhya et al., 2001], 17q21.31 deletion syndrome with the inverted H1 and H2 haplotypes [Itsara et al., 2012; Koolen et al., 2006; Stefansson et al., 2005; Zody et al., 2008], the BP4-BP5 inversions in 15q13.3 predisposing to CHRNA7 deletions and reciprocal duplications [Shinawi et al., 2009; Szafranski et al., 2010], and chromosomal regions 3q29, 8p23, 15q24, and 17q12 [Antonacci et al., 2009].

IP-LCR-Mediated Inversions May Mimic Gene Conversions

Paralogous LCRs have also been shown to be responsible for gene conversion events. For example, gene conversions between the SMN1 gene and its more centromeric SMN2 copy that differ by only five nucleotides [Lefebvre et al., 1995] and are embedded in a large ~1.9 MB complex LCR cluster with many subunits mapping in opposite orientation, that is, inverted repeats, are responsible for autosomal recessive spinal muscular dystrophy (MIM# 253300). However, both the SMN1 and SMN2 genes are directly oriented with reference to each other and thus were not included in our analysis.

It is possible that some of the IP-LCR-mediated genomic inversions might have been mistakenly recognized as gene conversion events. In support of this notion, three (NCF1, PMS2, and RHD) of the 942 identified genes have been reported to be inactivated by gene conversion events between the IP-LCR copies.

Autosomal recessive chronic granulomatous disease (CGD; MIM# 306400) results from a deficiency of the NCF1 (neutrophil cytosolic factor 1) gene, encoding the p47 (phox) subunit of NADPH oxidase [Casimir et al., 1991; Gorlach et al., 1997; Noack et al., 2001; Roesler et al., 2000; Volpp et al., 1993]. NCF1 maps in the Williams–Beuren syndrome (WBS) chromosome region at 7q11.23 and is embedded within a 144 kB LCR of 99.67% sequence identity with the inverted copy located 350 kB distally and harboring the pseudogene copy NCF1C. In addition, a directly oriented 106 kB LCR copy of 99.54% sequence identity located 1.5 MB proximally encompasses the second NCF1 pseudogene, NCF1B. Roesler et al. (2000) have reported recombination events between the NCF1 gene and its highly homologous pseudogenes, causing NCF1 inactivation due to gene conversion, resulting in the incorporation of delta-GT in patients with CGD. However, to date, no inversions between NCF1 and NCF1C have been described. Interestingly, patients with WBS, who had NCF1 deleted had significantly less prevalent hypertension when compared to those whose 7q11.23 deletion did not include NCF1 (P = 0.02) [Del Campo et al., 2006]. These findings suggest that decreased amount of NCF1 protects against hypertension, likely through a lifelong reduced angiotensin II-mediated oxidative stress.

The PMS2 (postmeiotic segregation increased, Saccharomyces cerevisiae) gene has been found to be mutated in patients with a mismatch repair deficient cancer syndrome (homozygous mutations, MIM# 276300) and hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer-4 (heterozygous mutations, MIM# 614337). PMS2 has a PMS2CL pseudogene copy, corresponding to its exons 9 and 11 to 15 embedded in a 100-kB inverted duplication located about 700 kB centromeric [De Vos et al., 2004; Auclair et al., 2007]. Hayward et al. (2007) have demonstrated that gene conversions between the PMS2 and PMS2CL are the ongoing process that leads to the allelic diversity of PMS2 and is thus a challenge for mutation analysis. We have not found any evidence of IP-LCR/NAHR-mediated inversions involving either PMS2 or other tumor suppressor genes.

Gene conversions between RHD and RHCE are considered as the major mechanism responsible for polymorphism and gene diversity in the Rh blood group antigen genes; however, gene deletions have also been identified [Innan et al., 2003].

DUP-TRP/INV-DUP

In addition to NAHR, inverted LCRs have been shown to have a potential for generating non-B DNA structures that can stall DNA replication fork progression, for example, DNA hairpins [Voineagu et al., 2008, 2009], and render a region prone to undergo genomic rearrangements due to the FoSTeS/MMBIR mechanism. Intrachromosomal template switches between inverted repeats can produce duplication of the segment in between the inverted repeats in addition to a variable-sized triplication embedded within the duplication of the segment flanking one of the inverted repeats (DUP-TRP/INV-DUP rearrangements). Therefore, dosage-sensitive genes maping within or flanking those inverted repeats are at risk for an incrase in copy-number (duplication or triplication) or gene interruption at a breakpoint of the CGR.

Approximately, 20% of the rearrangements observed in patients with MECP2 duplication syndrome (MIM# 300260) were produced by the aforementioned molecular mechanism [Carvalho et al., 2009, 2011]; in a subset of these cases, the MECP2 gene is included in the triplication which will lead to more severely affected patients [Carvalho et al., 2011; Del Gaudio et al., 2006]. In addition, the Xq22 locus was also observed to be prone to similar rearrangements [Carvalho et al., 2011]. PLP1 is the dosage-sensitive gene that maps close to the inverted repeats at the Xq22 locus, duplications of which are responsible for 60–70% of Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease cases (PMD; MIM# 312080). DUP-TRP/INV-DUP rearrangements were observed in three patients with PMD reported in Carvalho et al. (2011); only the duplication encompassed PLP1. Recently, we have observed one very severely affected patient with PMD who was found to have a DUP-TRP/INV-DUP rearrangement, in which the triplication encompasses PLP1 (unpublished observation). A severely affected PMD patient with such a CGR has also been reported by Shimojima et al. (2012).

These findings prompted us to hypothesize that DUP-TRP/INV-DUP rearrangements elsewhere in the genome are likely underestimated as is their contribution to human genomic disorders [Lupski, 1998, 2009; Stankiewicz and Lupski 2002]. We now bioinformatically identified 1,551 DTIP-LCRs which can potentially mediate a template switch during break-induced replication (BIR) and produce DUP-TRP/INV-DUP rearrangements (Fig. 1). In total, 5,644 genes across the genome were identified in proximity (±1 MB) to these inverted repeats of which 1,445 are classified as disease-associated genes.

In summary, our data demonstrate that inverted LCRs represent a prominent architectural feature of the human genome structure. Furthermore, the genomic instability rendered by inverted repeats in the human genome can result in genomic variation that could be responsible for many human disease traits.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Drs. F. Probst, I. Van den Veyver, and A.N. Pursley for helpful discussion.

Contract grant sponsors: Polish National Science Center (2011/01/B/NZ2/00864 to A.G. and P.D.); EU through the European Social Fund (UDA-POKL.04.01.01–00-072/09–00 to P.D.); the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education (R13–0005-04/2008 to P.S.); and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01 NS058529 to J.R.L.).

References

- Alders M, Koopmann TT, Christiaans I, Postema PG, Beekman L, Tanck MWT, Zeppenfeld K, Loh P, Koch KT, Demolombe S, Mannens MM, Bezzina CR, et al. Haplotype-sharing analysis implicates chromosome 7q36 harboring DPP6 in familial idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:468–476. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonacci F, Kidd JM, Marques-Bonet T, Ventura M, Siswara P, Jiang Z, Eichler EE. Characterization of six human disease-associated inversion polymorphisms. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:2555–2566. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aradhya S, Bardaro T, Galgóczy P, Yamagata T, Esposito T, Patlan H, Ciccodicola A, Munnich A, Kenwrick S, Platzer M, D’Urso M, Nelson DL. Multiple pathogenic and benign genomic rearrangements occur at a 35 kB duplication involving the NEMO and LAGE2 genes. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:2557–2567. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.22.2557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auclair J, Leroux D, Desseigne F, Lasset C, Saurin JC, Joly MO, Pinson S, Xu XL, Montmain G, Ruano E, Navarro C, Puisieux A, et al. Novel biallelic mutations in MSH6 and PMS2 genes: gene conversion as a likely cause of PMS2 gene inactivation. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:1084–1090. doi: 10.1002/humu.20569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagnall RD, Waseem N, Green PM, Giannelli F. Recurrent inversion breaking intron 1 of the factor VIII gene is a frequent cause of severe hemophilia A. Blood. 2002;99:168–174. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JA, Yavor AM, Massa HF, Trask BJ, Eichler EE. Segmental duplications: organization and impact within the current human genome project assembly. Genome Res. 2001;11:1005–1017. doi: 10.1101/gr.187101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamford RN, Roessler E, Burdine RD, Saplakoglu U, dela Cruz J, Splitt M, Towbin J, Bowers P, Marino B, Schier AF, Shen MM, Muenke M, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the EGF-CFC gene CFC1 are associated with human left-right laterality defects. Nat Genet. 2000;26:365–369. doi: 10.1038/81695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender HU, Almashanu S, Steel G, Hu CA, Lin WW, Willis A, Pulver A, Valle D. Functional consequences of PRODH missense mutations. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:409–420. doi: 10.1086/428142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergen AAB, Plomp AS, Schuurman EJ, Terry S, Breuning M, Dauwerse H, Swart J, Kool M, van Soest S, Baas F, ten Brink JB, de Jong PT. Mutations in ABCC6 cause pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Nat Genet. 2000;25:228–231. doi: 10.1038/76109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondeson ML, Dahl N, Malmgren H, Kleijer WJ, Tönnesen T, Carlberg BM, Pettersson U. Inversion of the IDS gene resulting from recombination with IDS-related sequences is a common cause of the Hunter syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:615–621. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.4.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boocock GRB, Morrison JA, Popovic M, Richards N, Ellis L, Durie PR, Rommens JM. Mutations in SBDS are associated with Shwachman–Diamond syndrome. Nat Genet. 2003;33:97–101. doi: 10.1038/ng1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone PM, Bacino CA, Shaw CA, Eng PA, Hixson PM, Pursley AN, Kang SH, Yang Y, Wiszniewska J, Nowakowska BA, del Gaudio D, Xia Z, et al. Detection of clinically relevant exonic copy-number changes by array CGH. Hum Mutat. 2010;31:1326–1342. doi: 10.1002/humu.21360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeron T, Rustin P, Chretien D, Birch-Machin M, Bourgeois M, Viegas-Pequignot E, Munnich A, Rotig A. Mutation of a nuclear succinate dehydrogenase gene results in mitochondrial respiratory chain deficiency. Nat Genet. 1995;11:144–149. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyadjiev SA, South ST, Radford CL, Patel A, Zhang G, Hur DJ, Thomas GH, Gearhart JP, Stetten G. A reciprocal translocation 46,XY,t(8;9)(p11.2;q13) in a bladder exstrophy patient disrupts CNTNAP3 and presents evidence of a pericentromeric duplication on chromosome 9. Genomics. 2005;85:622–629. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnichon N, Briere JJ, Libe R, Vescovo L, Riviere J, Tissier F, Jouanno E, Jeunemaitre X, Benit P, Tzagoloff A, Rustin P, Bertherat J, Favier J, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP. SDHA is a tumor suppressor gene causing paraganglioma. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:3011–3020. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho CM, Ramocki MB, Pehlivan D, Franco LM, Gonzaga-Jauregui C, Fang P, McCall A, Pivnick EK, Hines-Dowell S, Seaver LH, Friehling L, Lee S, et al. Inverted genomic segments and complex triplication rearrangements are mediated by inverted repeats in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1074–1081. doi: 10.1038/ng.944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho CM, Zhang F, Liu P, Patel A, Sahoo T, Bacino CA, Shaw C, Peacock S, Pursley A, Tavyev YJ, Ramocki MB, Nawara M, et al. Complex rearrangements in patients with duplications of MECP2 can occur by fork stalling and template switching. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:2188–2203. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casimir CM, Bu-Ghanim HN, Rodaway ARF, Bentley DL, Rowe P, Segal AW. Autosomal recessive chronic granulomatous disease caused by deletion at a dinucleotide repeat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2753–2757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.7.2753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celestino-Soper PB, Shaw CA, Sanders SJ, Li J, Murtha MT, Ercan-Sencicek AG, Davis L, Thomson S, Gambin T, Chinault AC, Ou Z, German JR, et al. Use of array CGH to detect exonic copy number variants throughout the genome in autism families detects a novel deletion in TMLHE. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:4360–4370. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawkins JL, Hulme DJ, Brahmbhatt SB, Auer-Grumbach M, Nicholson GA. Mutations in SPTLC1, encoding serine palmitoyltransferase, long chain base subunit-1, cause hereditary sensory neuropathy type I. Nat Genet. 2001;27:309–312. doi: 10.1038/85879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vos M, Hayward BE, Picton S, Sheridan E, Bonthron DT. Novel PMS2 pseudogenes can conceal recessive mutations causing a distinctive childhood cancer syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:954–964. doi: 10.1086/420796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Campo M, Antonell A, Magano LF, Munoz FJ, Flores R, Bayes M, Perez Jurado LA. Hemizygosity at the NCF1 gene in patients with Williams–Beuren syndrome decreases their risk of hypertension. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:533–542. doi: 10.1086/501073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Gaudio D, Fang P, Scaglia F, Ward PA, Craigen WJ, Glaze DG, Neul JL, Patel A, Lee JA, Irons M, Berry SA, Pursley AA, et al. Increased MECP2 gene copy number as the result of genomic duplication in neurodevelopmentally delayed males. Genet Med. 2006;8:784–792. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000250502.28516.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff RM, Tay V, Hackman P, Ravenscroft G, McLean C, Kennedy P, Steinbach A, Schoffler W, van der Ven PF, Furst DO, Song J, Djinović-Carugo K, et al. Mutations in the N-terminal actin-binding domain of filamin C cause a distal myopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:729–740. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flomen RH, Davies AF, Di Forti M, La Cascia C, Mackie-Ogilvie C, Murray R, Makoff AJ. The copy number variant involving part of the alpha-7 nicotinic receptor gene contains a polymorphic inversion. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16:1364–1371. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores M, Morales L, Gonzaga-Jauregui C, Domínguez-Vidaña R, Zepeda C, Yañez O, Gutiérrez M, Lemus T, Valle D, Avila MC, Blanco D, Medina-Ruiz S, et al. Recurrent DNA inversion rearrangements in the human genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:6099–6106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701631104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fluck CE, Meyer-Boni M, Pandey AV, Kempna P, Miller WL, Schoenle EJ, Biason-Lauber A. Why boys will be boys: two pathways of fetal testicular androgen biosynthesis are needed for male sexual differentiation. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:201–218. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavish H, dos Santos CC, Buchwald M. Generation of a non-functional Fanconi anemia group C protein (FACC) by site-directed in vitro mutagenesis. Am J Hum Genet Suppl. 1992;51:A128. (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Goldmuntz E, Bamford R, Karkera JD, dela Cruz J, Roessler E, Muenke M. CFC1 mutations in patients with transposition of the great arteries and double-outlet right ventricle. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:776–780. doi: 10.1086/339079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorlach A, Lee PL, Roesler J, Hopkins PJ, Christensen B, Green ED, Chanock SJ, Curnutte JT. A p47-phox pseudogene carries the most common mutation causing p47-phox-deficient chronic granulomatous disease. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:1907–1918. doi: 10.1172/JCI119721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings PJ, Ira G, Lupski JR. A microhomology-mediated break-induced replication model for the origin of human copy number variation. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward BE, De Vos M, Valleley EMA, Charlton RS, Taylor GR, Sheridan E, Bonthron DT. Extensive gene conversion at the PMS2 DNA mismatch repair locus. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:424–430. doi: 10.1002/humu.20457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermans A, Heisterkamp N, von Lindern M, van Baal S, Meijer D, van der Plas D, Wiedemann LM, Groffen J, Bootsma D, Grosveld G. Unique fusion of bcr and c-abl genes in Philadelphia chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cell. 1987;51:33–40. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C-H, Chen Y, Reid ME, Seidl C. Rh(null) disease: the amorph type results from a novel double mutation in RhCe gene on D-negative background. Blood. 1998;92:664–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang N, Lee I, Marcotte EM, Hurles ME. Characterising and predicting haploinsufficiency in the human genome. PLoS Genet. 2010;66:e1001154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innan H. A two-locus gene conversion model with selection and its application to the human RHCE and RHD genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8793–8798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1031592100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itsara A, Vissers LE, Steinberg KM, Meyer KJ, Zody MC, Koolen DA, de Ligt J, Cuppen E, Baker C, Lee C, Graves TA, Wilson RK, et al. Resolving the breakpoints of the 17q21.31 microdeletion syndrome with next-generation sequencing. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:599–613. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquet H, Raux G, Thibaut F, Hecketsweiler B, Houy E, Demilly C, Haouzir S, Allio G, Fouldrin G, Drouin V, Bou J, Petit M, et al. PRODH mutations and hyperprolinemia in a subset of schizophrenic patients. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:2243–2249. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.19.2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Y, Rebert NA, Joslin JM, Higgins MJ, Schultz RA, Nicholls RD. Structure of the highly conserved HERC2 gene and of multiple partially duplicated paralogs in human. Genome Res. 2000;10:319–329. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.3.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser M, Liu F, Janssens AC, Rivadeneira F, Lao O, van Duijn K, Vermeulen M, Arp P, Jhamai MM, van Ijcken WF, den Dunnen JT, Heath S, et al. Three genome-wide association studies and a linkage analysis identify HERC2 as a human iris color gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:411–423. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofoed EM, Hwa V, Little B, Woods KA, Buckway CK, Tsubaki J, Pratt KL, Bezrodnik L, Jasper H, Tepper A, Heinrich JJ, Rosenfeld RG. Growth hormone insensitivity associated with a STAT5b mutation. New Engl J Med. 2003;349:1139–1147. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koolen DA, Pfundt R, de Leeuw N, Hehir-Kwa JY, Nillesen WM, Neefs I, Scheltinga I, Sistermans E, Smeets D, Brunner HG, van Kessel AG, Veltman JA, de Vries BB. Genomic microarrays in mental retardation: a practical workflow for diagnostic applications. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:283–292. doi: 10.1002/humu.20883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koolen DA, Vissers LE, Pfundt R, de Leeuw N, Knight SJ, Regan R, Kooy RF, Reyniers E, Romano C, Fichera M, Schinzel A, Baumer A, et al. A new chromosome 17q21.31 microdeletion syndrome associated with a common inversion polymorphism. Nat Genet. 2006;38:999–1001. doi: 10.1038/ng1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzywinski MI, Schein JE, Birol I, Connors J, Gascoyne R, Horsman D, Jones SJ, Marra MA. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009;19:1639–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz S, Choudhuri JV, Ohlebusch E, Schleiermacher C, Stoye J, Giegerich R. REPuter: the manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:4633–4642. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.22.4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakich D, Kazazian HH, Jr, Antonarakis SE, Gitschier J. Inversions disrupting the factor VIII gene are a common cause of severe haemophilia A. Nat Genet. 1993;5:236–241. doi: 10.1038/ng1193-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange J, Skaletsky H, van Daalen SK, Embry SL, Korver CM, Brown LG, Oates RD, Silber S, Repping S, Page DC. Isodicentric Y chromosomes and sex disorders as byproducts of homologous recombination that maintains palindromes. Cell. 2009;138:855–869. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Saux O, Urban Z, Tschuch C, Csiszar K, Bacchelli B, Quaglino D, Pasquali-Ronchetti I, Pope FM, Richards A, Terry S, Bercovitch L, de Paepe A, et al. Mutations in a gene encoding an ABC transporter cause pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Nat Genet. 2000;25:223–227. doi: 10.1038/76102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JA, Carvalho CM, Lupski JR. A DNA replication mechanism for generating nonrecurrent rearrangements associated with genomic disorders. Cell. 2007;131:1235–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre S, Burglen L, Reboullet S, Clermont O, Burlet P, Viollet L, Benichou B, Cruaud C, Millasseau P, Zeviani M, Le Paslier D, Frézal J, et al. Identification and characterization of a spinal muscular atrophy-determining gene. Cell. 1995;80:155–165. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90460-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P, Carvalho CM, Hastings P, Lupski JR. Mechanisms for recurrent and complex human genomic rearrangements. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2012;22:211–220. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P, Lacaria M, Zhang F, Withers M, Hastings PJ, Lupski JR. Frequency of nonallelic homologous recombination is correlated with length of homology: evidence that ectopic synapsis precedes ectopic crossing-over. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:580–588. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonnqvist T, Isohanni P, Valanne L, Olli-Lahdesmaki T, Suomalainen A, Pihko H. Dominant encephalopathy mimicking mitochondrial disease. Neurology. 2011;76:101–103. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318203e908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupski JR. Genomic disorders: structural features of the genome can lead to DNA rearrangements and human disease traits. Trends Genet. 1998;14:417–22. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01555-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupski JR. Genome structural variation and sporadic disease traits. Nat Genet. 2006;38:974–976. doi: 10.1038/ng0906-974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupski JR. Genomic disorders ten years on. Genome Med. 2009;1:42. doi: 10.1186/gm42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino S, Kaji R, Ando S, Tomizawa M, Yasuno K, Goto S, Matsumoto S, Tabuena MD, Maranon E, Dantes M, Lee LV, Ogasawara K, et al. Reduced neuron-specific expression of the TAF1 gene is associated with X-linked Dystonia–Parkinsonism. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:393–406. doi: 10.1086/512129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malenfant P, Liu X, Hudson ML, Qiao Y, Hrynchak M, Riendeau N, Hildebrand MJ, Cohen IL, Chudley AE, Forster-Gibson C, Mickelson EC, Rajcan-Separovic E, et al. Association of GTF2i in the Williams–Beuren syndrome critical region with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42:1459–1469. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1389-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masurel-Paulet A, Andrieux J, Callier P, Cuisset JM, Le Caignec C, Holder M, Thauvin-Robinet C, Doray B, Flori E, Alex-Cordier MP, Beri M, Boute O, et al. Delineation of 15q13.3 microdeletions. Clin Genet. 2010;78:149–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno JC, Bikker H, Kempers MJE, van Trotsenburg ASP, Baas F, de Vijlder JJM, Vulsma T, Ris-Stalpers C. Inactivating mutations in the gene for thyroid oxidase 2 (THOX2) and congenital hypothyroidism. New Engl J Med. 2002;347:95–102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor J, Brinke A, Hassock S, Green PM, Giannelli F. Characteristic mRNA abnormality found in half the patients with severe hemophilia A is due to large DNA inversions. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2:1773–1778. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.11.1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor JA, Buck D, Green P, Williamson H, Bentley D, Giannelli F. Investigation of the factor VIII intron 22 repeated region (int22h) and the associated inversion junctions. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:1217–1224. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.7.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor JA, Green PM, Rizza CR, Giannelli F. Factor VIII gene explains all cases of hemophilia A. Lancet. 1992;340:1066–1067. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)93080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neilson DE, Adams MD, Orr CMD, Schelling DK, Eiben RM, Kerr DS, Anderson J, Bassuk AG, Bye AM, Childs AM, Clarke A, Crow YJ, et al. Infection-triggered familial or recurrent cases of acute necrotizing encephalopathy caused by mutations in a component of the nuclear pore, RANBP2. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noack D, Rae J, Cross AR, Ellis BA, Newburger PE, Curnutte JT, Heyworth PG. Autosomal recessive chronic granulomatous disease caused by defects in NCF1, the gene encoding the phagocyte p47-phox: mutations not arising in the NCF1 pseudogenes. Blood. 2001;97:305–311. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.1.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Driscoll MC, Daly SB, Urquhart JE, Black GCM, Pilz DT, Brockmann K, McEntagart M, Abdel-Salam G, Zaki M, Wolf NI, Ladda RL, Sell S, et al. Recessive mutations in the gene encoding the tight junction protein occludin cause bandlike calcification with simplified gyration and polymicrogyria. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:354–364. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozcelik C, Bit-Avragim N, Panek A, Gaio U, Geier C, Lange PE, Dietz R, Posch MG, Perrot A, Stiller B. Mutations in the EGF-CFC gene cryptic are an infrequent cause of congenital heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol. 2006;27:695–698. doi: 10.1007/s00246-006-1082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palo OM, Soronen P, Silander K, Varilo T, Tuononen K, Kieseppä T, Partonen T, Lönnqvist J, Paunio T, Peltonen L. Identification of susceptibility loci at 7q31 and 9p13 for bipolar disorder in an isolated population. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2010;153B:723–735. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce EG, Smith SK, Lanigan SW, Bowden PE. Two different mutations in the same codon of a type II hair keratin (hHb6) in patients with monilethrix. J Invest Derm. 1999;113:1123–1127. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radicke S, Cotella D, Graf EM, Ravens U, Wettwer E. Expression and function of dipeptidyl-aminopeptidase-like protein 6 as a putative beta-subunit of human cardiac transient outward current encoded by Kv4.3. J Physiol. 2005;565:751–756. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.087312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roesler J, Curnutte JT, Rae J, Barrett D, Patino P, Chanock SJ, Goerlach A. Recombination events between the p47-phox gene and its highly homologous pseudogenes are the main cause of autosomal recessive chronic granulomatous disease. Blood. 2000;95:2150–2156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roessler E, Ouspenskaia MV, Karkera JD, Vélez JI, Kantipong A, Lacbawan F, Bowers P, Belmont JW, Towbin JA, Goldmuntz E, Feldman B, Muenke M. Reduced NODAL signaling strength via mutation of several pathway members including FOXH1 is linked to human heart defects and holoprosencephaly. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saadi I, Alkuraya FS, Gisselbrecht SS, Goessling W, Cavallesco R, Turbe-Doan A, Petrin AL, Harris J, Siddiqui U, Grix AW, Jr, Hoove HD, Leboulch P, et al. Deficiency of the cytoskeletal protein SPECC1L leads to oblique facial clefting. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:44–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Dorr NP, Takahashi N, McInnes LA, Elder GA, Buxbaum JD. Haploinsufficiency of Gtf2i, a gene deleted in Williams -Syndrome, leads to increases in social interactions. Autism Res. 2011;4:28–39. doi: 10.1002/aur.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp AJ, Locke DP, McGrath SD, Cheng Z, Bailey JA, Vallente RU, Pertz LM, Clark RA, Schwartz S, Segraves R, et al. Segmental duplications and copy-number variation in the human genome. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:78–88. doi: 10.1086/431652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp AJ, Mefford HC, Li K, Baker C, Skinner C, Stevenson RE, Schroer RJ, Novara F, De Gregori M, Ciccone R, Broomer A, Casuga I, et al. A recurrent 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome associated with mental retardation and seizures. Nat Genet. 2008;40:322–328. doi: 10.1038/ng.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimojima K, Mano T, Kashiwagi M, Tanabe T, Sugawara M, Okamoto N, Arai H, Yamamoto T. Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease caused by a duplication-inverted triplication-duplication in chromosomal segments including the PLP1 region. Eur J Med Genet. 2012;55:400–403. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin YS, Rieth M, Endres W. Sorbitol dehydrogenase deficiency in a family with congenital cataracts. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1984;7(Suppl. 2):151–152. doi: 10.1007/978-94-009-5612-4_50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinawi M, Schaaf CP, Bhatt SS, Xia Z, Patel A, Cheung SW, Lanpher B, Nagl S, Herding HS, Nevinny-Stickel C, Immken LL, Patel GS, et al. A small recurrent deletion within 15q13.3 is associated with a range of neurodevelopmental phenotypes. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1269–1271. doi: 10.1038/ng.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinibaldi L, De Luca A, Bellacchio E, Conti E, Pasini A, Paloscia C, Spalletta G, Caltagirone C, Pizzuti A, Dallapiccola B. Mutations of the Nogo-66 receptor (RTN4R) gene in schizophrenia. Hum Mutat. 2004;24:534–535. doi: 10.1002/humu.9292. (Abstract) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stankiewicz P, Lupski JR. Genome architecture, rearrangements and genomic disorders. Trends Genet. 2002;18:74–82. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)02592-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefansson H, Helgason A, Thorleifsson G, Steinthorsdottir V, Masson G, Barnard J, Baker A, Jonasdottir A, Ingason A, Gudnadottir VG, Desnica N, Hicks A, et al. A common inversion under selection in Europeans. Nat Genet. 2005;37:129–137. doi: 10.1038/ng1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee CA, Gavish H, Shannon WR, Buchwald M. Cloning of cDNAs for Fanconi’s anaemia by functional complementation. Nature. 1992;356:763–767. doi: 10.1038/356763a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm RA, Duffy DL, Zhao ZZ, Leite FPN, Stark MS, Hayward NK, Martin NG, Montgomery GW. A single SNP in an evolutionary conserved region within intron 86 of the HERC2 gene determines human blue-brown eye color. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:424–431. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulem P, Gudbjartsson DF, Stacey SN, Helgason A, Rafnar T, Magnusson KP, Manolescu A, Karason A, Palsson A, Thorleifsson G, Jakobsdottir M, Steinberg S, et al. Genetic determinants of hair, eye and skin pigmentation in Europeans. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1443–1452. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szafranski P, Schaaf CP, Person RE, Gibson IB, Xia Z, Mahadevan S, Wiszniewska J, Bacino CA, Lalani S, Potocki L, Kang SH, Patel A, et al. Structures and molecular mechanisms for common 15q13.3 microduplications involving CHRNA7: benign or pathological? Hum Mutat. 2010;31:840–850. doi: 10.1002/humu.21284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wesenbeeck L, Odgren PR, Coxon FP, Frattini A, Moens P, Perdu B, MacKay CA, Van Hul E, Timmermanns JP, Vanhoenacker F, Jacobs R, Peruzzi B, et al. Involvement of PLEKHM1 in osteoclastic vesicular transport and osteopetrosis in incisors absent rats and humans. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:919–930. doi: 10.1172/JCI30328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigone MC, Fugazzola L, Zamproni I, Passoni A, Di Candia S, Chiumello G, Persani L, Weber G. Persistent mild hypothyroidism associated with novel sequence variants of the DUOX2 gene in two siblings. Hum Mutat. 2005;26:395. doi: 10.1002/humu.9372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vissers LE, Stankiewicz P. Microdeletion and microduplication syndromes. In: Feuk L, editor Genomic structural variants. New York: Springer; 2012. pp. 29–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voineagu I, Freudenreich CH, Mirkin SM. Checkpoint responses to unusual structures formed by DNA repeats. Mol Carcinogen. 2009:48309–318. doi: 10.1002/mc.20512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voineagu I, Narayanan V, Lobachev KS, Mirkin SM. Replication stalling at unstable inverted repeats: interplay between DNA hairpins and fork stabilizing proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9936–9941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804510105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpp BD, Lin Y. In vitro molecular reconstitution of the respiratory burst in B lymphoblasts from p47-phox-deficient chronic granulomatous disease. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:201–207. doi: 10.1172/JCI116171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorgerd M, van der Ven PFM, Bruchertseifer V, Lowe T, Kley RA, Schroder R, Lochmuller H, Himmel M, Koehler K, Furst DO, Huebner A. A mutation in the dimerization domain of filamin C causes a novel type of autosomal dominant myofibrillar myopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:297–304. doi: 10.1086/431959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Wang J, Liu S, Han X, Xie X, Tao Y, Yan J, Ma X. CFC1 mutations in Chinese children with congenital heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 2011;146:86–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton PE, Giordano J, Cheung F, Gelfand Y, Benson G. Inverted repeat structure of the human genome: the X-chromosome contains a preponderance of large, highly homologous inverted repeats that contain testes genes. Genome Res. 2004;14:1861–1869. doi: 10.1101/gr.2542904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter H, Rogers MA, Gebhardt M, Wollina U, Boxall L, Chitayat D, Babul-Hirji R, Stevens HP, Zlotogorski A, Schweizer J. A new mutation in the type II hair cortex keratin hHb1 involved in the inherited hair disorder monilethrix. Hum Genet. 1997;101:165–169. doi: 10.1007/s004390050607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter H, Vabres P, Larregue M, Rogers MA, Schweizer J. A novel missense mutation, A118E, in the helix initiation motif of the type II hair cortex keratin hHb6, causing monilethrix. Hum Hered. 2000;50:322–324. doi: 10.1159/000022936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu KD, Di GH, Yuan WT, Fan L, Wu J, Hu Z, Shen ZZ, Zheng Y, Huang W, Shao ZM. Functional polymorphisms, altered gene expression and genetic association link NRH:quinone oxidoreductase 2 to breast cancer with wild-type p53. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:2502–2517. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zepeda-Mendoza CJ, Lemus T, Yáñez O, García D, Valle-García D, Meza-Sosa KF, Gutiérrez-Arcelus M, Márquez-Ortiz Y, Domínguez-Vidaña R, Gonzaga-Jauregui C, Flores M, Palacios R. Identical repeated backbone of the human genome. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, De S, Garner JR, Smith K, Wang SA, Becker KG. Systematic analysis, comparison, and integration of disease based human genetic association data and mouse genetic phenotypic information. BMC Med Genomics. 2010;3:1. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Feuk L, Duggan GE, Khaja R, Scherer SW. Development of bioinformatics resources for display and analysis of copy number and other structural variants in the human genome. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2006;115:205–214. doi: 10.1159/000095916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zody MC, Jiang Z, Fung HC, Antonacci F, Hillier LW, Cardone MF, Graves TA, Kidd JM, Cheng Z, Abouelleil A, Chen L, Wallis J, et al. Evolutionary toggling of the MAPT 17q21.31 inversion region. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1076–1083. doi: 10.1038/ng.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.