Abstract

Study Objectives:

To examine relationships between different physical activity (PA) domains and sleep, and the influence of consistent PA on sleep, in midlife women.

Design:

Cross-sectional.

Setting:

Community-based.

Participants:

339 women in the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation Sleep Study (52.1 ± 2.1 y).

Interventions:

None.

Measurements and Results:

Sleep was examined using questionnaires, diaries and in-home polysomnography (PSG). PA was assessed in three domains (Active Living, Household/Caregiving, Sports/Exercise) using the Kaiser Physical Activity Survey (KPAS) up to 4 times over 6 years preceding the sleep assessments. The association between recent PA and sleep was evaluated using KPAS scores immediately preceding the sleep assessments. The association between the historical PA pattern and sleep was examined by categorizing PA in each KPAS domain according to its pattern over the 6 years preceding sleep assessments (consistently low, inconsistent/consistently moderate, or consistently high). Greater recent Sports/Exercise activity was associated with better sleep quality (diary “restedness” [P < 0.01]), greater sleep continuity (diary sleep efficiency [SE; P = 0.02]) and depth (higher NREM delta electroencephalographic [EEG] power [P = 0.04], lower NREM beta EEG power [P < 0.05]), and lower odds of insomnia diagnosis (P < 0.05). Consistently high Sports/Exercise activity was also associated with better Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index scores (P = 0.02) and higher PSG-assessed SE (P < 0.01). Few associations between sleep and Active Living or Household/Caregiving activity (either recent or historical pattern) were noted.

Conclusion:

Consistently high levels of recreational physical activity, but not lifestyle- or household-related activity, are associated with better sleep in midlife women. Increasing recreational physical activity early in midlife may protect against sleep disturbance in this population.

Citation:

Kline CE; Irish LA; Krafty RT; Sternfeld B; Kravitz HM; Buysse DJ; Bromberger JT; Dugan SA; Hall MH. Consistently high sports/exercise activity is associated with better sleep quality, continuity and depth in midlife women: the SWAN Sleep Study. SLEEP 2013;36(9):1279-1288.

Keywords: Physical activity, exercise, sleep, polysomnography, sleep depth, sleep continuity

INTRODUCTION

Sleep disturbance affects 30% to 60% of midlife women1,2 and has significant consequences on health and functioning. In addition to impaired daytime function,3 disturbed sleep is associated with a host of adverse health outcomes, including cardio-metabolic morbidity.4,5 Among midlife women in particular, sleep disturbance has been linked to increased risk of diabetes,6 the metabolic syndrome,7,8 and cardiovascular mortality.9

Unfortunately, very little is known about behavioral or life-style factors which could protect against sleep disturbance during midlife. Physical activity may be one such protective factor, but the current evidence is mixed. In the general population, physical activity is commonly associated with better sleep,10 and exercise interventions have significantly reduced the severity of various sleep disorders (e.g., insomnia, obstructive sleep apnea, periodic limb movements during sleep).11–13 However, this relationship is much less clear in midlife women. Although higher levels of physical activity have been associated with less sleep disturbance in some studies of this population,2,14 others have found no relation.15–18

Methodological limitations likely contributed to the equivocal state of knowledge regarding the relevance of physical activity to sleep in midlife women. Sleep outcomes have often been based on single-item measures14,17,18 or brief questionnaires focused on insomnia-related symptoms2,15,16; objective measures of sleep have not been assessed. This is especially relevant for midlife women, since subjective reports and objective measures of sleep are often divergent.19,20 In addition, the epidemiologic literature is based on measurement of physical activity at a single time-point. However, since the effects of relatively acute physical activity on sleep may differ from those conferred by long-term patterns of physical activity participation,21 multiple assessments over time may yield a more accurate view of the sleep-related benefits of habitual physical activity. Finally, studies have focused on recreational physical activity, which fails to capture the overall physical activity profile of midlife women.22,23 Compared to men, women are less active in recreational physical activity, but similarly active when physical activity related to household and care-giving duties are considered.24

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between physical activity and subjective and objective indices of sleep in midlife women. Our primary interest was to examine the relationship between sleep and two different timeframes of physical activity, proximal (i.e., measured closest to sleep assessments) and historical (i.e., pattern of activity over 5-6 years leading up to sleep assessments). We also sought to evaluate the relationship between sleep and different domains of physical activity (i.e., lifestyle, household, recreational).

METHODS

Data for these analyses were from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Sleep Study, a cross-sectional study of sleep in a multi-ethnic sample of midlife women. The SWAN Sleep Study is an ancillary study of the longitudinal SWAN cohort (N = 3,302), a study of the menopausal transition and its consequences on health and functioning, being conducted at 7 clinical sites across the United States.25 Data for the SWAN Sleep Study were collected at 4 sites from 2003 through 2005: Chicago, IL; Detroit area, MI; Oakland, CA; and Pittsburgh, PA. Each site recruited Caucasian participants, while African American participants were recruited from the Chicago, Detroit, and Pittsburgh sites, and Chinese participants were recruited from the Oakland site.

Participants

A cohort of 370 SWAN Sleep Study participants was recruited from the core SWAN study at the time of their fifth, sixth, or seventh annual assessment. SWAN Sleep Study exclusion criteria were hysterectomy or bilateral oophorectomy, current cancer treatment, current oral corticosteroid use, regular nocturnal shiftwork, regular consumption of > 4 alcoholic beverages per day, or noncompliance with core SWAN procedures (> 50% of annual visits missed, refusal of annual visit blood draws). Written informed consent was obtained by all participants in accordance with approved protocols and guidelines of the institutional review board of each participating institution.

Due to missing physical activity data (see below; n = 13) or missing covariate data (n = 18), 339 women were included in analyses. Compared to women whose data were retained for analysis, excluded participants had significantly higher Pitts-burgh Sleep Quality Index scores (mean ± standard deviation [SD]: 7.40 ± 3.46 vs. 5.57 ± 3.05; P = 0.002) and lower rela-tive beta electroencephalographic (EEG) power during NREM sleep (1.41 ± 0.52 vs. 1.83 ± 1.03; P = 0.03). No other differences in sleep outcomes were observed. Excluded participants did not differ from women retained for analysis on physical activity (for participants missing covariate data) or covariates (for participants missing physical activity data).

Physical Activity Measurement

Physical activity was assessed with a modified version of the Kaiser Physical Activity Survey (KPAS)22 at SWAN study entry and at annual visits 3, 5, and 6. Adapted from the Baecke physical activity questionnaire,26 the KPAS assesses activity levels during the previous 12 months in 3 distinct domains: Active Living (e.g., frequency of television viewing [reverse scored], active transportation such as walking to work), Household/Caregiving (e.g., housework, childcare), and Sports/Exercise (e.g., participation in recreational activity or sports). A fourth domain, occupation, was not evaluated because many SWAN participants were not employed for pay outside of the home. Domain-specific activity indices were calculated from mostly ordinal Likert scale categorical responses, with higher scores indicating greater activity in that specific domain (range: 1-5). The KPAS has been validated against activity logs, accelerometers, and maximal oxygen consumption,22 with 1-month test-retest reliability of 0.81 to 0.84 (varying by domain).22

Participants were excluded from analysis if KPAS data from SWAN annual visits 5 and 6 were not available (n = 13). The 3 KPAS domains were evaluated for their association with sleep in 2 ways: according to (1) recent physical activity and (2) the historical pattern of physical activity. For analyses focusing on recent physical activity, continuous KPAS scores from the SWAN annual visit that preceded the SWAN Sleep Study were used (1.05 ± 0.70 years preceding SWAN Sleep). For analyses examining the historical pattern of physical activity, participant physical activity in each domain was classified as “consistently high,” “inconsistent/moderate,” or “consistently low” based upon 2-4 KPAS assessments in the 5-6 years prior to the SWAN Sleep Study. For classification in “consistently high” or “consistently low” groups, KPAS domain scores needed to be in the top or bottom tertile, respectively, at > 50% of the available time-points. Patterns of KPAS data that failed to meet this criterion were classified as “inconsistent/moderate” activity for that specific domain.

Sleep Assessment

The SWAN Sleep Study was conducted across a complete menstrual cycle or 35 days, whichever was shorter. In participants with regular menstrual cycles, the protocol was initiated within 7 days of the start of menstrual bleeding. Women who had irregular menstrual cycles or were non-cycling were scheduled at their convenience.

A multi-modal assessment of sleep was conducted, employing in-home polysomnography (PSG), daily sleep diaries, and validated questionnaires. This approach provided a comprehensive assessment of sleep quality and indices of sleep duration, continuity and depth, as well as measurement of clinically significant sleep disturbance (e.g., sleep disordered breathing). Due to differing amounts of data loss across sleep measures, the sample size used for each respective sleep measure varied and is indicated in parentheses below.

Polysomnography

Polysomnography (Vitaport-3; Temec Instruments, Kerkrade, Netherlands) was conducted in participants' homes according to their habitual sleep and wake times over 3 consecutive nights at the beginning of the Sleep Study protocol. The PSG montage included EEG recorded at C3 and C4 referenced to linked mastoids, bilateral electrooculogram, submentalis electromyogram (EMG), and electrocardiogram. Additional signals were collected on the first night of PSG recording to assess sleep disordered breathing (SDB) and periodic limb movements during sleep (PLMS). For SDB assessment, additional signals included nasal pressure cannula, oronasal thermistor, respiratory inductance plethysmography, and fingertip oximetry, whereas PLMS was monitored with bilateral anterior tibialis EMG.

Visual sleep stage scoring was conducted in 20-sec epochs using standard sleep stage scoring criteria.27 In addition, SDB events were evaluated using American Academy of Sleep Medicine definitions,28 and PLMS was assessed using standard rules.29 As measured from the first night of PSG recording, the apnea-hypopnea index ([AHI] n = 321) and periodic limb movement arousal index ([PLMAI] n = 323) were retained as measures of SDB and PLMS, respectively. All other summary sleep variables (n = 335) were averaged across the non-SDB/ PLMS assessment nights due to the potentially disruptive effects of breathing and limb movement assessment on sleep. Two summary measures, total sleep time (TST) and sleep efficiency (SE), were used in analyses. As a measure of sleep duration, TST was calculated as the total minutes of any sleep stage following sleep onset. As a measure of sleep continuity, SE was calculated as the ratio of TST to time in bed multiplied by 100.

As a measure of sleep “depth,” spectral analysis of the EEG signal was performed to quantify power in the delta (0.5-4.0 Hz) and beta (16-32 Hz) frequency bands during NREM sleep (n = 313). Modified periodograms were computed using the Fast Fourier transform of non-overlapping 4-sec epochs of the sleep EEG. Following automated artifact rejection,30 EEG spectra were obtained for each artifact-free 4-sec epoch and aligned with 20-sec visually scored sleep stage data. Relative power (i.e., spectral power within a specific frequency band [microvolts2/Hz] divided by the total power across 0.5 to 32 Hz [microvolts2/Hz], resulting in unit-less values) was used in analyses to account for individual differences in EEG power.

Daily Sleep Diary

Subjective perceptions of sleep were obtained across the entire Sleep Study protocol through daily completion of a sleep diary. Each morning, participants were asked to recall the prior night's sleep and indicate the time they got into bed and attempted to sleep, how long it took to fall asleep, the final out-of-bed time, and length of overnight awakenings. In addition, participants were asked to indicate how rested they felt upon awakening, from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). Diary variables retained for analysis included TST (as a measure of sleep duration), SE (as a measure of sleep continuity), and restedness (as a measure of sleep quality), averaged across all valid nights (mean [SD] nights per participant: 29.94 ± 6.57; n = 339).

Questionnaires

The 18-item Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) 31 was administered on the fourth and last days of the Sleep Study protocol (n = 336). The PSQI provides a validated measure of sleep quality; scores range from 0-21, with higher scores indicating worse sleep quality. PSQI scores were highly correlated (r = 0.81, P < 0.001) and were averaged for analyses. The 13-item Insomnia Symptom Questionnaire (ISQ)32 was administered on the last day of the Sleep Study protocol to provide case definitions of insomnia (n = 331). The ISQ assesses the frequency and severity of insomnia-related symptoms and provides a dichotomous assessment of insomnia presence/ absence based upon DSM-IV criteria.

Covariates

Covariates were chosen for inclusion in statistical analyses due to their established relationships with sleep and/or relevance to the possible relationship between physical activity and sleep. Age was calculated at the time of the sleep study.

Race/ethnicity (Caucasian, African American, Chinese) was defined by self-identification. Marital status, employment status, and body mass index (BMI) were assessed at the closest core SWAN visit prior to the sleep study. Marital status was dichotomized as being unmarried (i.e., single, divorced, separated, widowed) or married/living as married, employment status was dichotomized as not employed/employed for pay < 20 h/week or employed for pay ≥ 20 h/week, and BMI was expressed as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Educational attainment was assessed by self-report during the core SWAN baseline interview and dichotomized as less than a college degree or at least a college degree. Use of medication that affects sleep was assessed over the course of the study protocol, including both prescription and over-the-counter medicines. Medications were coded according to the World Health Organization ATC classification system, and medications with the following ATC codes were considered to affect sleep: N02A (opioids), N03A (antiepileptics), N05B (anxiolytics), N05C (hypnotics and sedatives), N06A (antide-pressants), and R06A (antihistamines).33 Medication use was dichotomized as none/infrequent (< 3 nights/week) or frequent (≥ 3 nights/week). Menopausal status was determined by bleeding patterns reported during the closest core SWAN visit prior to the SWAN Sleep Study: participants were categorized as being pre- or early perimenopausal, late perimenopausal, or postmenopausal, as previously described.34 Vasomotor symptoms (VMS) were assessed by daily diary entries. Each morning, participants were asked to report the number of cold sweats, hot flashes, and night sweats they experienced during the previous night's sleep. Vasomotor symptoms were categorized as being present if at least one VMS was reported that night, and participants were categorized based upon the frequency of nighttime VMS: none to infrequent (< 25% of nights), intermittent (25 to < 75% of nights), and frequent (≥ 75% of nights). Smoking status, caffeine consumption, and alcohol use were assessed by daily diary entries. Smoking status was dichotomized as none versus any reported smoking, caffeine consumption was calculated as the mean daily number of caffeinated beverages, and alcohol use was calculated as the mean daily number of alcoholic drinks.

Statistical Analyses

Prior to analyses, skewed sleep variables were transformed (see Table legends for specific transformations employed). Relationships between KPAS domain scores preceding the Sleep Study were evaluated with Pearson correlations. To evaluate associations between the patterns of different KPAS domains in the 5-6 years preceding the Sleep Study, the like-lihood of having a pattern of “consistently high” activity in each domain relative to other domains was evaluated with binary logistic regression.

To evaluate the relationship between sleep and recent physical activity (i.e., assessed at the SWAN visit immediately preceding the Sleep Study), linear and logistic regression analyses were conducted for each KPAS domain (Active Living, Household/Caregiving, Sports/Exercise). Multiple linear regression analyses were conducted to examine each KPAS domain score as a predictor of continuous sleep outcomes after adjusting for previously described covariates. Binary logistic regression analyses were performed to evaluate the odds of meeting diagnostic criteria for insomnia (based upon the ISQ), moderate-severity SDB (AHI ≥ 15), and moderate-severity PLMS (PLMAI ≥ 10), as used in previous SWAN Sleep Study publications.32,35

To evaluate the relationship between sleep and the historical pattern of physical activity (i.e., assessed at up to 4 time-points in the 5-6 years preceding the Sleep Study), analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) and logistic regression analyses were conducted for each KPAS domain. With adjustment for previously noted covariates, ANCOVA evaluated differences in continuous sleep outcomes between historical patterns of each KPAS domain, with Tukey group comparisons performed when appropriate. Binary logistic regression evaluated the odds of having clinically significant sleep disturbance (as described above) according to physical activity history pattern. “Consistently low” physical activity was used as the referent group.

Analyses were conducted using SAS v. 9.2 (SAS Institute; Cary, NC). All statistical tests were 2-tailed, with statistical significance set at P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

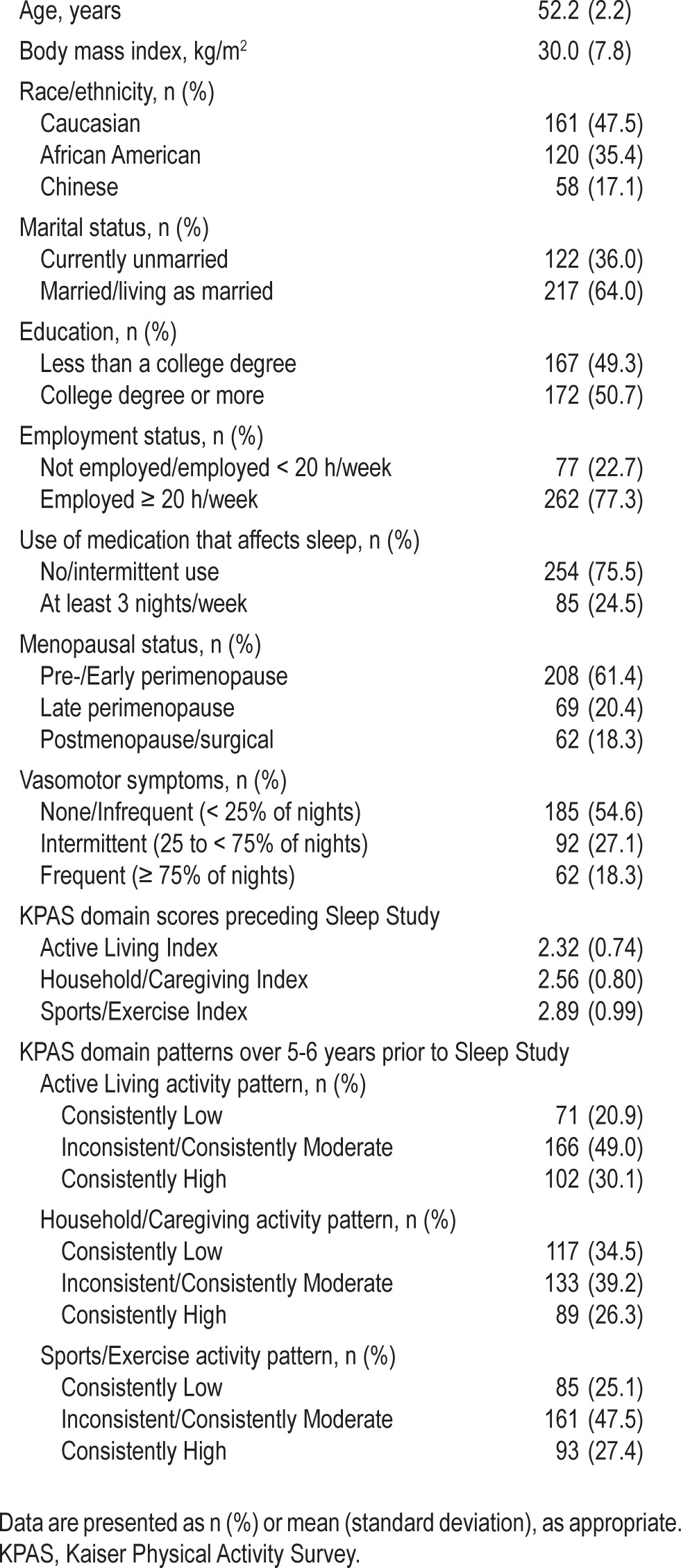

Characteristics of the study sample are summarized in Table 1. Of the 339 women included in analyses, the mean [SD] age was 52.2 ± 2.2 years; 48% of the women were Caucasian, 35% were African American, and 17% were Chinese. Approximately 25% of the sample used medications that affect sleep ≥ 3 nights per week, and the majority (55%) reported no or infrequent VMS during the Sleep Study protocol.

Table 1.

SWAN Sleep Study participant characteristics (N = 339)

KPAS domain scores for Active Living, Household/Care-giving, and Sports/Exercise preceding the Sleep Study were similar in level and mildly correlated with each other (Active Living and Household/Caregiving: r = 0.13, P = 0.02; Active Living and Sports/Exercise: r = 0.32, P < 0.001; Household/ Caregiving and Sports/Exercise: r = 0.22, P < 0.001). Compared to women with a pattern of consistently low or moderate Sports/Exercise activity, women with a pattern of consistently high Sports/Exercise activity had significantly increased odds of having patterns of consistently high Active Living activity (odds ratio [OR] = 3.32 [95% confidence interval = 2.01, 5.50]) and Household/Caregiving activity (OR = 1.87 [1.11, 3.14]).

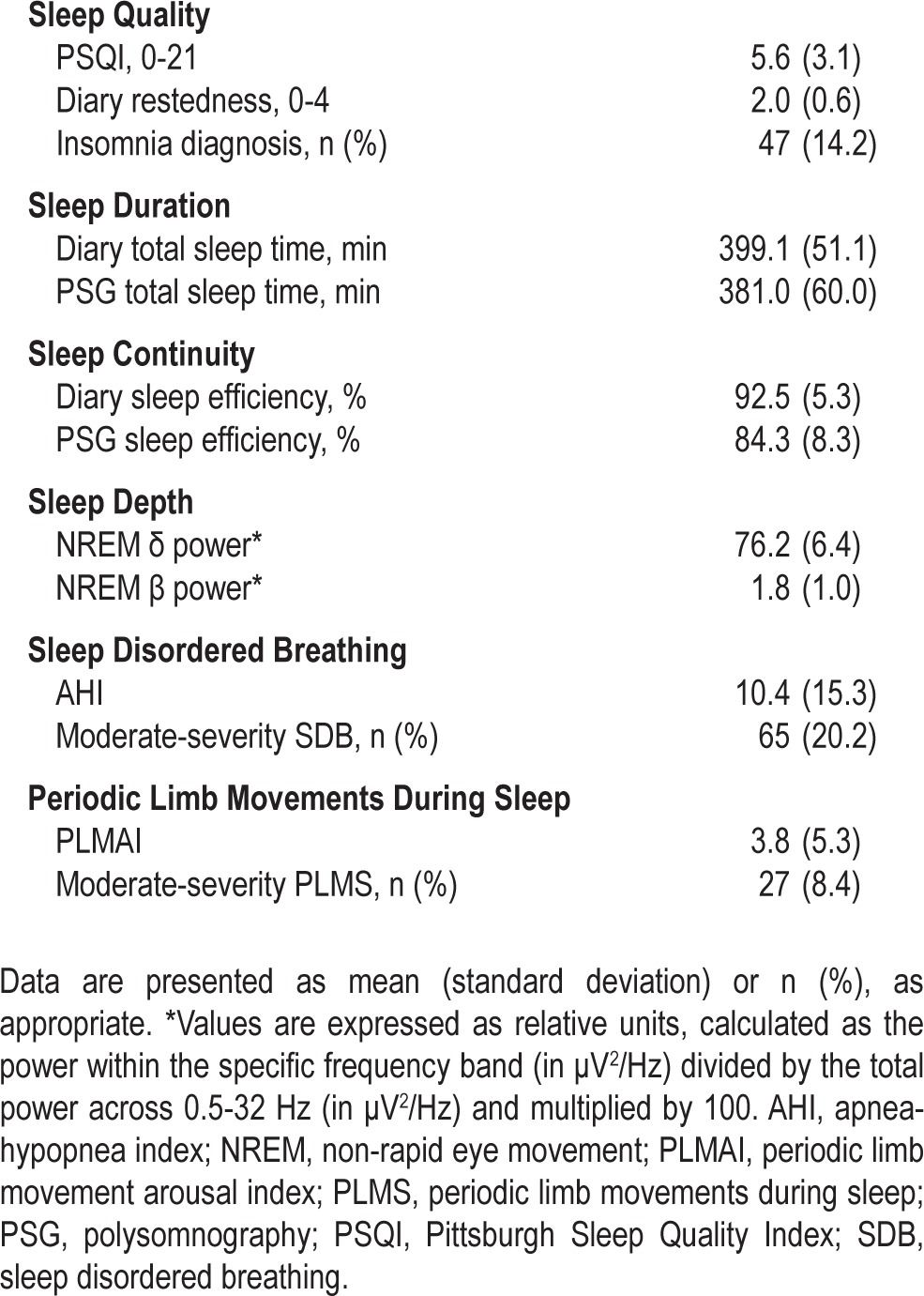

Table 2 provides a summary of the sleep characteristics of the sample. Of note, average PSQI score of the sample was 5.6 ± 3.1 and PSG-assessed TST was 381.0 ± 60.0 min. Approximately 14% of women met diagnostic criteria for insomnia (n = 47 of 331), 20.2% had at least moderate-severity SDB (n = 65 of 321), and 8.4% of women had at least moderate-severity PLMS (n = 27 of 323).

Table 2.

SWAN Sleep Study participant sleep characteristics and prevalence of clinically significant sleep disturbances

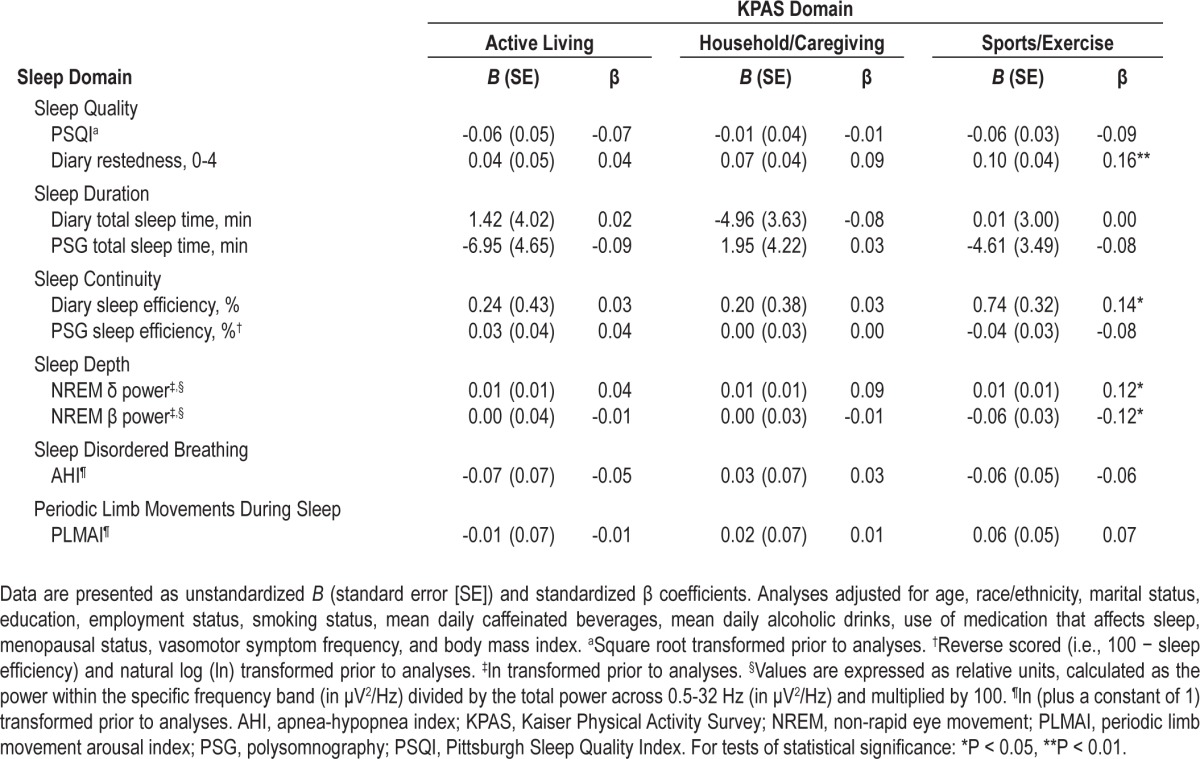

Recent Physical Activity and Sleep

Table 3 summarizes the association between sleep and physical activity levels assessed immediately preceding the SWAN Sleep Study. No significant associations were observed between sleep and Active Living or Household/Caregiving Index scores. In contrast, higher Sports/Exercise Index scores were associated with greater sleep quality and continuity, as assessed by diary-based measures of restedness (β = 0.16, P < 0.01) and SE (β = 0.14, P = 0.02), respectively, and with greater sleep depth, as indicated by higher NREM delta power (β = 0.12, P = 0.04) and lower NREM beta power (β = -0.12, P < 0.05).

Table 3.

Relationship between sleep and recent physical activity (closest preceding Sleep Study) according to physical activity domain

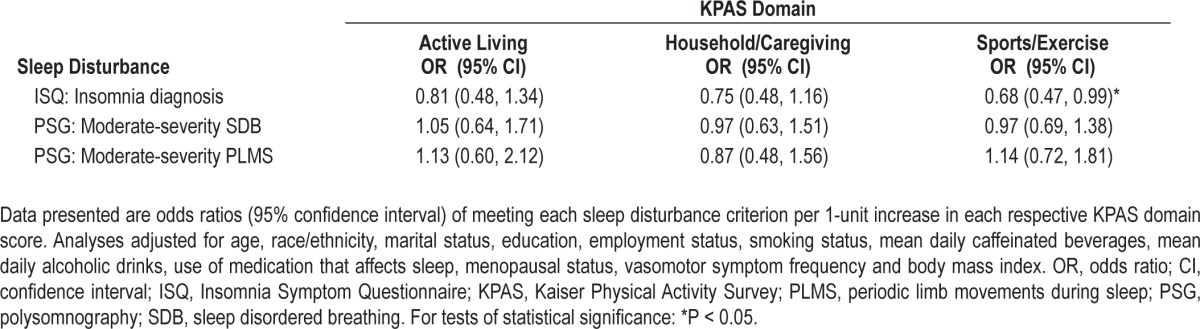

Table 4 displays the odds of clinically significant sleep disturbance according to recent activity levels for each KPAS domain. The odds of insomnia diagnosis, moderate-severity SDB, or moderate-severity PLMS did not differ by Active Living or Household/Caregiving Index value. However, there were lower odds of meeting diagnostic criteria for insomnia with higher Sports/Exercise Index scores (OR = 0.68 [0.47, 0.99]).

Table 4.

Odds of clinically significant sleep disturbance according to recent domain-specific physical activity (closest preceding Sleep Study)

Historical Physical Activity Pattern and Sleep

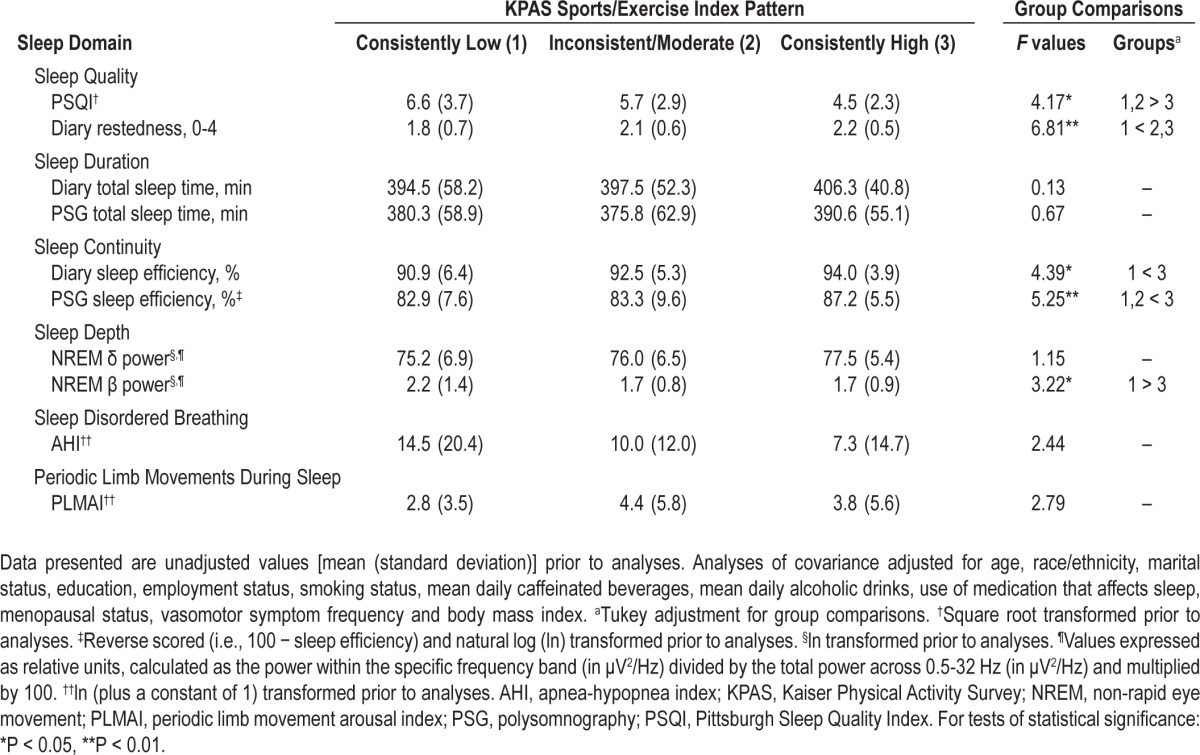

When evaluating the relationship between sleep and different historical patterns of domain-specific physical activity, no differences in sleep outcomes were observed across patterns of Active Living Index activity (data not shown). Polysomnographic TST values significantly differed across Household/Caregiving Index patterns (F2,313 = 3.13, P = 0.04); women with consistently high Household/Caregiving values had greater PSG TST than women with a consistent pattern of low Household/Caregiving values (P = 0.05). Differences between Sports/Exercise Index patterns, summarized in Table 5, were observed for sleep quality (PSQI [F2,317 = 4.17, P = 0.02], diary restedness [F2,320 = 6.81, P < 0.01]), sleep continuity (diary SE [F2,320 = 4.39, P = 0.01], PSG SE [F2,316 = 5.25, P < 0.01]), and sleep depth (NREM β power [F2,294 = 3.22, P = 0.04]). For the majority of these measures, women with a consistently high level of Sports/Exercise activity had significantly better sleep compared to women with consistently low Sports/Exercise activity.

Table 5.

Sleep according to the historical pattern of KPAS Sports/Exercise activity (i.e., 5-6 years preceding the Sleep Study)

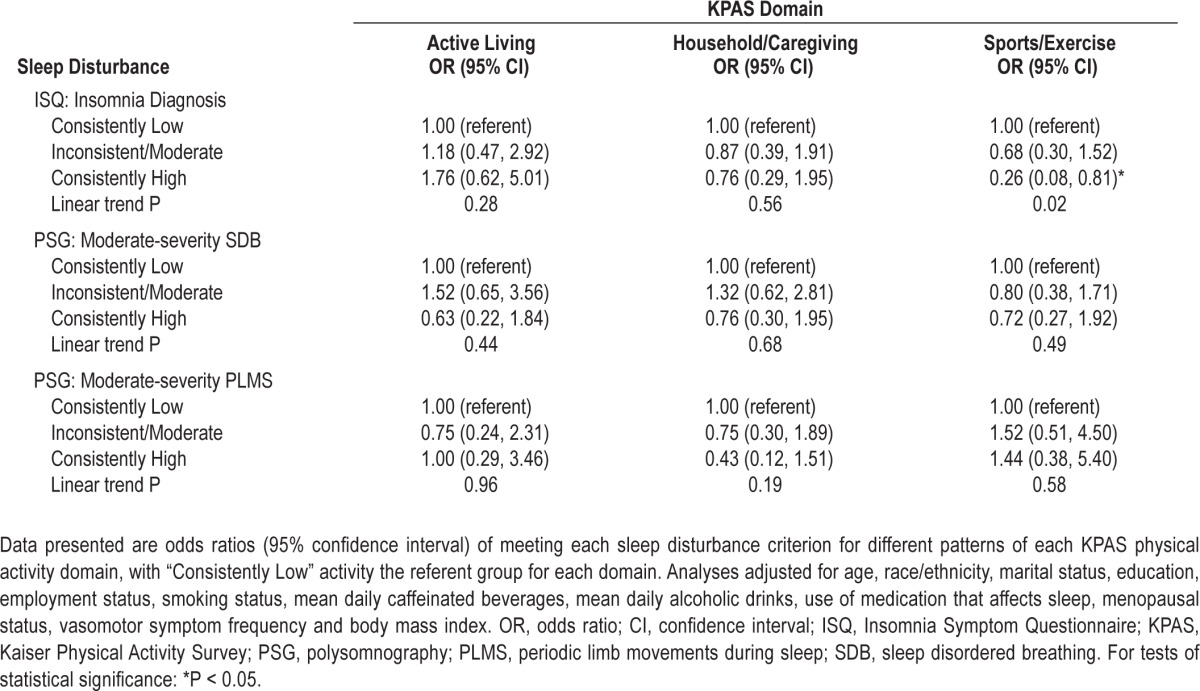

Table 6 displays the odds of clinically significant sleep disturbance according to different patterns of domain-specific activity. The odds of insomnia diagnosis, moderate-severity SDB, or moderate-severity PLMS did not differ across patterns of Active Living or Household/Caregiving Index values. Relative to consistently low Sports/Exercise Index activity, consistently high Sports/Exercise Index activity was associated with lower odds of meeting diagnostic criteria for insomnia (OR = 0.26 [0.08, 0.81]), with a significant linear trend observed (P = 0.02).

Table 6.

Odds of clinically significant sleep disturbance according to historical domain-specific physical activity pattern (i.e., 5-6 years preceding the Sleep Study)

DISCUSSION

A growing literature has documented the prevalence and adverse consequences of sleep disturbance in midlife women.1,2,6–9 However, we know little about factors which may protect against sleep disturbance during this period of life. Physical activity may be one such protective factor, although the extant literature is equivocal. The present study used a multi-method approach to investigate the relationship between physical activity and sleep in midlife women, and several significant associations were noted. Higher levels of Sports/Exercise activity were consistently associated with important objective and subjective indices of sleep, whereas Active Living and Household/Caregiving activity were associated with few sleep outcomes. Moreover, the relationship between Sports/Exercise activity and sleep was most robust when considering the pattern of activity over multiple years relative to activity levels most proximal to the sleep assessment.

Although household- and lifestyle-related activity make a prominent contribution to the overall physical activity levels of midlife women,22 prior studies focused upon the association between recreational physical activity and sleep.2,14–18 In our analyses, few relationships emerged between sleep and either Active Living or Household/Caregiving domains of physical activity. Because the Active Living and Household/Caregiving indices of the KPAS predominantly reflect lower-intensity and/ or more intermittent activities,22,36 one possible explanation is that these domains of physical activity are of insufficient intensity to affect sleep. Although studies directly comparing the effects of low-, moderate-, and vigorous-intensity physical activity on sleep have not been conducted, physical activity interventions for sleep improvement have prescribed moderate and vigorous-intensity physical activity.37–41 Based upon our results, focusing on recreational physical activity for sleep improvement seems warranted.

A second key observation was that significantly better sleep, particularly measures pertaining to sleep quality and continuity, was observed among women with a consistent pattern of high Sports/Exercise activity in the 5-6 years leading up to the sleep assessment. As indicated by the fewer number of significant relationships observed, these findings were less consistent when only considering Sports/Exercise activity most recent to the sleep assessment. It is possible that, given the inherent measurement error in self-reported physical activity at a single time-point,42,43 repeated assessments of physical activity over time may simply provide a more accurate view of habitual physical activity. However, it is also possible that accrual of sleep-related benefits continue past initial adoption and maintenance of a physically active lifestyle, as has been documented for most other health outcomes.44 Unfortunately, the long-term time course of sleep improvement from exercise is unknown, since randomized trials longer than 6 months have rarely been conducted,39 and studies have neglected to assess sleep at intermediate time-points. Nevertheless, our results suggest that consistent participation in recreational physical activity may confer additional benefits to those achieved by more recent activity.

Sports/Exercise Index values were significantly associated with sleep quality, continuity, and depth, but not duration. Sports/Exercise activity had perhaps the most consistent relationship with sleep quality, as lower PSQI scores (consistently high activity only), higher diary-based reports of restedness, and reduced odds of meeting diagnostic criteria for insomnia were associated with higher levels of Sports/Exercise activity. These results concur with prior epidemiologic research,2,14 which concluded that physical activity is associated with less insomnia-related complaints and/or better subjective sleep in midlife women. However, they also contrast with findings from studies that reported nonsignificant associations between physical activity and sleep quality.15–18

These results are the first to document a relationship between physical activity and aspects of sleep other than sleep quality in midlife women, most notably objective indicators of sleep continuity and depth. Importantly, we observed Sports/Exercise activity to be associated with both subjective (i.e., diary) and objective (i.e., PSG) assessments of sleep efficiency. This methodological distinction is noteworthy, as subjective reports of sleep often differ from objective measures in midlife women.19,20 Moreover, we found that recent and consistently high levels of Sports/Exercise activity were associated with objective indices of sleep depth, as assessed by spectral analysis of the sleep EEG. Specifically, our findings of higher NREM delta EEG power (recent Sports/Exercise activity only) and lower NREM beta EEG power with greater levels of Sports/Exercise activity conflict with the notion that exercise primarily impacts subjective, but not objective, sleep parameters.45 In fact, we are unaware of any other studies that have linked habitual levels of recreational physical activity with altered EEG microarchitecture.

No physical activity domains were significantly associated with PLMS or SDB. The possible relationship between physical activity and PLMS has been sparsely explored, though experimental research suggests exercise may reduce PLMS severity.13 As our statistical models adjusted for BMI, with which SDB is strongly associated46 and a pathway by which physical activity may reduce SDB, it is unsurprising we failed to observe any significant associations between physical activity and SDB. Whereas our data are in agreement with others who found a minimal influence of physical activity on SDB once BMI was considered, 47 other epidemiologic research has reported an association between exercise and SDB independent of body composition.48

Strengths of this study include a well-characterized sample of women from an established cohort study, a comprehensive multi-modal assessment of sleep, consideration of multiple validated domains of physical activity at several time-points up to 6 years prior to sleep assessment, and statistical adjustment for several potential confounders. However, these strengths must be evaluated in light of study limitations. One such limitation is the lack of multi-modal sleep data from earlier in the SWAN study. As such, it is possible that persistent poor sleep quality led to low physical activity during the menopausal transition. Future research studies would ideally involve randomization of women with disturbed sleep to an exercise trial prior to the menopausal transition with longitudinal follow-up through post-menopause. Another limitation is that additional factors that were not considered in these analyses (e.g., mental health, environmental influences) could account for the findings. However, it is noteworthy that significant relationships between physical activity and sleep were observed despite statistical adjustment for key factors which could mediate this relationship (e.g., BMI, other health behaviors). An additional limitation is that our findings may not generalize to all women. For example, in a smaller SWAN ancillary study of predominantly postmeno-pausal women with frequent VMS, greater household-related activity was associated with better subjective sleep.49 Although race and menopausal status, among others, could potentially be important moderators of the relationship between physical activity and sleep, we did not have an adequate sample size to investigate these potential interactions. In the future, it will be important to evaluate whether these factors moderate the relationship between physical activity and sleep. A further limitation is the reliance upon self-report physical activity data. Subjective and objective assessments of physical activity are only modestly correlated,22 with objective assessment indicating much less physical activity than self-reported.50 Specifically, the KPAS does not permit detailed inquiry of the specific activities reported (e.g., timing, intensity, volume) and absolute amounts of physical activity performed. Consequently, its best use may be for ranking levels of activity, as were performed in this study. Similarly, “inconsistent” patterns of physical activity over 5-6 years were grouped with “consistently moderate” patterns of physical activity in analyses. Although we did not have an adequate sample size to examine more specific subgroups, future research should endeavor to classify “inconsistent” activity patterns in a more precise manner when possible.

Despite these limitations, the study results supplement the existing literature on the benefits of physical activity on numerous other symptoms and health conditions that arise during the menopausal transition (e.g., depression, weight gain, reduced bone density).51 In particular, the potential use of physical activity as a nonpharmacologic treatment or preventive measure for sleep disturbance among midlife women is appealing, given that physical activity is a modifiable behavior with minimal side effects and the robust associations between consistent recreational physical activity and indices of sleep quality, continuity and depth that were noted herein. Randomized trials are needed to address the limitations of previous interventions that have evaluated the efficacy of exercise on sleep quality in midlife women, such as inclusion of women without sleep complaints,37,39–41 reliance upon subjective sleep measures,37–41 and failure to account for VMS.39,41

In summary, these results suggest that higher levels of recreational physical activity, but not lifestyle- or household-related activity, are associated with better sleep in midlife women, and that consistently high levels of activity are more robustly associated with better sleep than recent activity. Although experimental trials are needed to confirm these observations, adoption and/or maintenance of adequate recreational physical activity may help to improve sleep and protect against sleep disturbances that arise during midlife in women.

Clinical Centers

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor – Siobán Harlow, PI 2011-present, MaryFran Sowers, PI 1994-2011; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA – Joel Finkelstein, PI 1999-present; Robert Neer, PI 1994-1999; Rush University, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL – Howard Kravitz, PI 2009-present; Lynda Powell, PI 1994-2009; University of California, Davis/Kaiser – Ellen Gold, PI; University of California, Los Angeles – Gail Greendale, PI; Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY – Carol Derby, PI 2011-present, Rachel Wildman, PI 2010-2011; Nanette Santoro, PI 2004-2010; University of Medicine and Dentistry – New Jersey Medical School, Newark – Gerson Weiss, PI 1994-2004; and the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA – Karen Matthews, PI.

NIH Program Office

National Institute on Aging, Bethesda, MD – Winifred Rossi 2012-present; Sherry Sherman 1994-2012; Marcia Ory 1994-2001; National Institute of Nursing Research, Bethesda, MD

– Program Officers.

Central Laboratory

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor – Daniel McConnell (Central Ligand Assay Satellite Services).

Coordinating Center

University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA – Maria Mori Brooks, PI 2012-present; Kim Sutton-Tyrrell, PI 2001-2012; New England Research Institutes, Watertown, MA - Sonja McKinlay, PI 1995-2001.

Steering Committee

Susan Johnson, Current Chair; Chris Gallagher, Former Chair.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. Dr. Buysse has served as a paid consultant on scientific advisory boards for Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Philips Respironics, Purdue Pharma, Sanofi-Aventis, and Takeda. He has also spoken at single-sponsored educational meetings for Sanofi-Aventis and Servier. The other authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the study staff at each site and all the women who participated in SWAN. The Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) has grant support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), DHHS, through the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) and the NIH Office of Research on Women's Health (ORWH) (Grants U01NR004061, U01AG012505, U01AG012535, U01AG012531, U01AG012539, U01AG012546, U01AG012553, U01AG012554, U01AG012495). The SWAN Sleep Study was funded by the NIH (Grants R01AG019360, R01AG019361, R01AG019362, R01AG019363). Sleep data were processed with the support of UL1RR024153. Additional NIH grant support for Dr. Kline and Dr. Irish was provided by T32HL082610 and T32MH019986 respectively, and grant support for Dr. Krafty was provided by National Science Foundation DMS-0805050. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NSF, NIA, NINR, ORWH or the NIH.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kravitz HM, Ganz PA, Bromberger J, Powell LH, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Meyer PM. Sleep difficulty in women at midlife: a community survey of sleep and the menopausal transition. Menopause. 2003;10:19–28. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200310010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arakane M, Castillo C, Rosero MF, Penafiel R, Perez-Lopez FR, Chedraui P. Factors relating to insomnia during the menopausal transition as evaluated by the Insomnia Severity Index. Maturitas. 2011;69:157–61. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chedraui P, Perez-Lopez FR, Mendoza M, et al. Factors related to increased daytime sleepiness during the menopausal transition as evaluated by the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Maturitas. 2010;65:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cappuccio FP, D'Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Quantity and quality of sleep and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:414–20. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elwood P, Hack M, Pickering J, Hughes J, Gallacher J. Sleep disturbance, stroke, and heart disease events: evidence from the Caerphilly cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:69–73. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.039057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Delaimy WK, Manson JE, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Hu FB. Snoring as a risk factor for type II diabetes mellitus: a prospective study. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:387–93. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.5.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leineweber C, Kecklund G, Akerstedt T, Janszky I, Orth-Gomer K. Snoring and the metabolic syndrome in women. Sleep Med. 2003;4:531–6. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(03)00160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall MH, Okun ML, Sowers MF, et al. Sleep is associated with the metabolic syndrome in a multi-ethnic cohort of midlife women: the SWAN Sleep Study. Sleep. 2012;35:783–90. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campos-Rodriguez F, Martinez-Garcia MA, de la Cruz-Moron I, Almeida-Gonzalez C, Catalan-Serra P, Montserrat JM. Cardiovascular mortality in women with obstructive sleep apnea with or without continuous positive airway pressure treatment: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:115–22. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-2-201201170-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Youngstedt SD, Kline CE. Epidemiology of exercise and sleep. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2006;4:215–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-8425.2006.00235.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reid KJ, Baron KG, Lu B, Naylor E, Wolfe L, Zee PC. Aerobic exercise improves self-reported sleep and quality of life in older adults with insomnia. Sleep Med. 2010;11:934–40. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kline CE, Crowley EP, Ewing GB, et al. The effect of exercise training on obstructive sleep apnea and sleep quality: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep. 2011;34:1631–40. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esteves AM, de Mello MT, Pradella-Hallinan M, Tufik S. Effect of acute and chronic physical exercise on patients with periodic leg movements. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41:237–42. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318183bb22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li C, Borgfeldt C, Samsioe G, Lidfeldt J, Nerbrand C. Background factors influencing somatic and psychological symptoms in middle-age women with different hormonal status: a population-based study of Swedish women. Maturitas. 2005;52:306–18. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woods NF, Mitchell ES. Sleep symptoms during the menopausal transition and early postmenopause: observations from the Seattle Midlife Women's Health Study. Sleep. 2010;33:539–49. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.4.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pien GW, Sammel MD, Freeman EW, Lin H, DeBlasis TL. Predictors of sleep quality in women in the menopausal transition. Sleep. 2008;31:991–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Donato P., Giulini NA, Bacchi MA, Cicchetti G Progetto Menopausa Italia Study Group. Factors associated with climacteric symptoms in women around menopause attending menopause clinics in Italy. Maturitas. 2005;52:181–9. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tom SE, Kuh D, Guralnik JM, Mishra GD. Self-reported sleep difficulty during the menopausal transition: results from a prospective cohort study. Menopause. 2010;17:1128–35. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181dd55b0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Young T, Rabago D, Zgierska A, Austin D, Laurel F. Objective and subjective sleep quality in premenopausal, perimenopausal, and postmenopausal women in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study. Sleep. 2003;26:667–72. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.6.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freedman RR, Roehrs TA. Lack of sleep disturbance from menopausal hot flashes. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:138–44. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubitz KA, Landers DM, Petruzzello SJ, Han M. The effects of acute and chronic exercise on sleep: a meta-analytic review. Sports Med. 1996;21:277–91. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199621040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ainsworth BE, Sternfeld B, Richardson MT, Jackson K. Evaluation of the Kaiser Physical Activity Survey in women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:1327–38. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200007000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masse LC, Ainsworth BE, Tortolero S, et al. Measuring physical activity in midlife, older, and minority women: issues from an expert panel. J Womens Health. 1998;7:57–67. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1998.7.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hallal PC, Victora CG, Wells JC, Lima RC. Physical inactivity: prevalence and associated variables in Brazilian adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1894–1900. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000093615.33774.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sowers MF, Crawford S, Sternfeld B, et al. SWAN: a multi-center, multi-ethnic, community-based cohort study of women and the menopausal transition. In: Lobo RA, Kelsey J, Marcus R, editors. Menopause: biology and pathobiology. San Diego: Academic Press; 2000. pp. 175–88. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baecke JA, Burema J, Frijters JE. A short questionnaire for the measurement of habitual physical activity in epidemiological studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 1982;36:936–42. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/36.5.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rechtschaffen A, Kales A. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, Department of Health Education and Welfare; 1968. A manual of standardized terminology, techniques and scoring system for sleep stages of human subjects (NIH Publication 204) [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force. Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults: recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research. Sleep. 1999;22:667–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Sleep Disorders Association Atlas Task Force. Recording and scoring leg movements. Sleep. 1993;16:748–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brunner DP, Vasko RC, Detka CS, Monahan JP, Reynolds CF, III, Kupfer DJ. Muscle artifacts in the sleep EEG: automated detection and effect on all-night EEG power spectra. J Sleep Res. 1996;5:155–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1996.00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okun ML, Kravitz HM, Sowers MF, Moul DE, Buysse DJ, Hall M. Psychometric evaluation of the Insomnia Symptom Questionnaire: a self-report measure to identify chronic insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5:41–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization. Guidelines for ATC classification. [Accessed December 10, 2007]. Available at: http://www.whocc.no/atcddd.

- 34.Kravitz HM, Avery E, Sowers M, et al. Relationships between menopausal and mood symptoms and EEG sleep measures in a multi-ethnic sample of middle-aged women: the SWAN Sleep Study. Sleep. 2011;34:1221–32. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hall MH, Matthews KA, Kravitz HM, et al. Race and financial strain are independent correlates of sleep in midlife women: the SWAN Sleep Study. Sleep. 2009;32:73–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, et al. 2011 Compendium of Physical Activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:1575–81. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821ece12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elavsky S, McAuley E. Lack of perceived sleep improvement after 4-month structured exercise programs. Menopause. 2007;14:535–40. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000243568.70946.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mansikkamaki K, Raitanen J, Nygard CH, et al. Sleep quality and aerobic training among menopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. Maturitas. 2012;72:339–45. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tworoger SS, Yasui Y, Vitiello MV, et al. Effects of a yearlong moderate-intensity exercise and a stretching intervention on sleep quality in postmenopausal women. Sleep. 2003;26:830–6. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilbur J, Miller AM, McDevitt J, Wang E, Miller J. Menopausal status, moderate-intensity walking, and symptoms in midlife women. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2005;19:163–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kline CE, Sui X, Hall MH, et al. Dose-response effects of exercise training on the subjective sleep quality of postmenopausal women: exploratory analyses of a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e001044. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferrari P, Friedenreich C, Matthews CE. The role of measurement error in estimating levels of physical activity. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:832–40. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shephard RJ. Limits to the measurement of habitual physical activity by questionnaires. Br J Sports Med. 2003;37:197–206. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.37.3.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pedersen BK, Saltin B. Evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in chronic disease. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2006;16(Suppl 1):3–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2006.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buman MP, King AC. Exercise as a treatment to enhance sleep. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2010;4:500–14. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li C, Ford ES, Zhao G, Croft JB, Balluz LS, Mokdad AH. Prevalence of self-reported clinically diagnosed sleep apnea according to obesity status in men and women: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2005-2006. Prev Med. 2010;51:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Awad KM, Malhotra A, Barnet JH, Quan SF, Peppard PE. Exercise is associated with a reduced incidence of sleep-disordered breathing. Am J Med. 2012;125:485–90. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peppard PE, Young T. Exercise and sleep-disordered breathing: an association independent of body habitus. Sleep. 2004;27:480–4. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.3.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lambiase MJ, Thurston RC. Physical activity and sleep among midlife women with vasomotor symptoms. Menopause. 2013 Mar 25; doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e3182844110. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Masse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:181–8. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Daley AJ, Stokes-Lampard HJ, Macarthur C. Exercise to reduce vasomotor and other menopausal symptoms: a review. Maturitas. 2009;63:176–80. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]