Abstract

The availability of next-generation sequences of transcripts from prokaryotic organisms offers the opportunity to design a new generation of automated genome annotation tools not yet available for prokaryotes. In this work, we designed EuGene-P, the first integrative prokaryotic gene finder tool which combines a variety of high-throughput data, including oriented RNA-Seq data, directly into the prediction process. This enables the automated prediction of coding sequences (CDSs), untranslated regions, transcription start sites (TSSs) and non-coding RNA (ncRNA, sense and antisense) genes. EuGene-P was used to comprehensively and accurately annotate the genome of the nitrogen-fixing bacterium Sinorhizobium meliloti strain 2011, leading to the prediction of 6308 CDSs as well as 1876 ncRNAs. Among them, 1280 appeared as antisense to a CDS, which supports recent findings that antisense transcription activity is widespread in bacteria. Moreover, 4077 TSSs upstream of protein-coding or non-coding genes were precisely mapped providing valuable data for the study of promoter regions. By looking for RpoE2-binding sites upstream of annotated TSSs, we were able to extend the S. meliloti RpoE2 regulon by ∼3-fold. Altogether, these observations demonstrate the power of EuGene-P to produce a reliable and high-resolution automatic annotation of prokaryotic genomes.

Keywords: genome annotation, prokaryotes, RNA-Seq, rhizobium

1. Introduction

With the new generation of sequencing (NGS) technologies, bacterial and archeal genome projects now combine deep genomic sequencing with a variety of transcriptome libraries.1–4 If the main motivation for transcriptome sequencing is usually the quantification of gene expression, the transcribed sequences generated by deep sequencing can also contribute to prokaryotic genome annotation by the elucidation of gene structural features, including transcription start sites (TSSs), 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) and the identification of non-coding RNA (ncRNA) genes. The quantification of gene expression following deep cDNA sequencing is based on the number of reads that map to a given gene. Therefore, the development of genome annotation tools that enable a better delineation of transcripts should lead to a more reliable expression measurement. In the recent sequencing of bacterial and archeal genomes, the annotation has still been done manually owing to the lack of appropriate tools to integrate RNA-Seq data.5 Indeed, most existing prokaryotic gene finders6–9 or high-level bacterial annotation systems10,11 are based on genomic sequence analysis and cannot take into account available expression data in the structural prediction. Expert annotation using RNA-Seq data has been recently facilitated by the use of integrated tools, such as VESPA12 or MicroScope,13 which allow to simultaneously visualize genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic or syntenic data, but the ultimate curation process still remains laborious.

With the tremendously increasing number of prokaryotic genomes that is being sequenced, there is a clear need for automated prokaryotic genome annotation tools able to integrate the variety of informative data that can be produced either by second-generation sequencing or by other high-throughput analyses, such as tiling arrays and proteomics. The development of such prokaryotic gene finders allowing not only the prediction of coding sequences (CDSs), but also TSSs and non-coding (nc) transcribed genes, should provide improved transcript quantification, facilitated identification of regulatory sequences upstream of mapped TSSs and thus, easier analysis of gene regulation. Because of the higher complexity of eukaryotic gene structures and the usual availability of transcribed sequences (such as expressed sequence tags or ESTs), many eukaryotic gene finders already have the ability to integrate experimental evidence in their gene prediction process. For example, ESTs are exploited in EuGene14 and Augustus,15 GenomScan16 uses similarities with known proteins, whereas SGP/SGP217,18 and EuGene'Hom19 integrates sequence conservation with related organisms.

In this work, we adapted the eukaryotic gene finder, EuGene14,20, to the specific requirements of gene identification in prokaryotes, where in particular overlapping CDSs are relatively frequent. EuGene has already been used successfully to annotate a variety of eukaryotic genomes21–27 and has shown its ability to quickly incorporate new types of information for enhancing its predictive power. The generic tool developed here, called EuGene-P, exploits high-throughput data, such as strand-specific RNA-Seq data, to qualitatively improve the prediction contents and to minimize manual expert annotation. The produced annotation contains previously unpredicted important gene structure features such as 5′ and 3′ UTRs, as well as ncRNA genes (including antisense RNAs). The mathematical model behind EuGene-P and its modular software architecture based on plug-ins facilitate the integration of a variety of other high-throughput data, such as PET-Seq, mass spectrometry data, protein similarities, DNA homologies, predicted transcription terminators and others. The source codes of EuGene-P are available under the open-source Artistic licence at https://mulcyber.toulouse.inra.fr/projects/eugene. A fully automated generic prokaryotic pipeline annotation relying on EuGene-P is under preparation and will be made available.

We trained and used EuGene-P for the annotation of the nitrogen-fixing symbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti bacterial strain 2011 (Sm2011). Sinorhizobium meliloti is a Gram-negative bacterium belonging to the alpha subclass of Proteobacteria, which can live either free in the soil, or in symbiotic association with roots of legume plants such as the model legume Medicago truncatula.26 The Sinorhizobium–Medicago symbiotic interaction leads to the formation of new root organs called nodules, within which bacteria differentiate into bacteroids that fix nitrogen to the benefit of the host plant. Both nodule organogenesis and bacteroid differentiation are complex developmental processes that involve deep reprogramming of gene expression in both organisms.28–30 The 6.7-Mb genome of Sm2011 is composed of three replicons, one main chromosome and two megaplasmids called pSymA and pSymB. The Sm2011 strain used in this study is closely related to the Sm1021 reference strain that was previously sequenced.31 Both strains are independent spontaneous streptomycin-resistant derivatives of the parental SU47 strain.32 Despite being originated from the same parental strain, a number of phenotypic differences were reported,33–38 which may be related to specific genetic differences. In this work, we determined both the genome sequence and the transcriptome of the Sm2011 strain under in planta and different growth conditions. These data were integrated into EuGene-P to refine and enrich the annotation of the S. meliloti genome sequence, notably to predict TSSs and ncRNA genes.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Bacterial strains and growth conditions

The bacterial strain used in this study was the streptomycin-resistant derivative of Sm2011 (GMI11495). A rpoE2 mutant derivative of this strain was generated as previously described.39 Strains were grown under aerobic conditions at 28°C in Vincent minimal medium supplemented with disodium succinate and ammonium chloride as carbon and nitrogen sources as previously described.40 Bacteria were collected either in a mid-exponential phase (OD600 = 0.6) or in an early stationary phase (∼1 h 30 min after entry in a stationary phase, OD600 = 1.2). Bacteria were harvested by filtration on 0.2 µm membranes, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until RNA extraction. Bacterial cultures were collected from three independent biological experiments.

2.2. Plant material and growth conditions

Medicago truncatula cv Jemalong A17 seeds were germinated and transferred to aeroponic caissons as described,41 under the following chamber conditions: temperature: 22°C; 75% hygrometry; light intensity: 200 μE m−2 s−1; light–dark photoperiod: 16–8 h. Plants were grown for 18 days in caisson growth medium42 supplemented with 10 mM NH4NO3, before growth in nitrogen-free medium for 4 days prior to inoculation with S. meliloti. At 10 days post-inoculation, nodules were harvested on ice from at least 20 plants, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Each biological repetition corresponded to an independent caisson, with ∼40 plants per caisson.

2.3. Sinorhizobium meliloti genome sequencing

The genome of Sm2011 was sequenced at the Genoscope (CNS, Evry, France) using fractions of 454 Titanium (46 Mb), 454 paired ends (18 Mb, insert size: 8 kb) and Illumina single end reads (1.2 Gb, read length: 76 nt), providing a 190-fold theoretical coverage of the genome. The genome sequence was assembled as described in Supplementary Materials and Methods. The nucleotide sequences of Sm2011 and Sm1021 strains were compared using the glint software (Faraut T. and Courcelle E.; http://lipm-bioinfo.toulouse.inra.fr/download/glint/, unpublished) to identify polymorphic regions. A set of 71 mutations including 64 putative frameshifts were verified by Sanger sequencing of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products surrounding these regions generated using either Sm2011 or Sm102132 DNA as a template. The genome sequence of Sm2011 was submitted to Genbank under accession numbers CP004138, CP004139 and CP004140, and a browser was set up at https://iant.toulouse.inra.fr/S.meliloti2011.

2.4. RNA preparations

RNAs were prepared as described in Supplementary Materials and Methods. Briefly, total RNAs extracted from cultured bacteria and root nodules were depleted of ribosomal RNAs by an oligocapture strategy derived from the Plant Ribominus kit (Invitrogen), in which the oligonucleotide sets were specifically designed to target M. truncatula and S. meliloti rRNAs, as well as the highly abundant S. meliloti tRNA-Ala (see Supplementary Table S1 for oligonucleotide sequences). RNAs were then separated in two fractions, short (<200 nt) and long (>200 nt), using Zymo Research RNA Clean & Concentrator™-5 columns (Proteigene).

2.5. cDNA library preparation and Illumina sequencing

Oriented sequencing with a RNA ligation procedure was carried out by Fasteris SA (Geneva, Switzerland) using procedures recommended by Illumina, with adaptors and amplification primers designed by Fasteris, unless specified. For small RNAs, the Small RNA Sequencing Alternative v1.5 Protocol (Illumina) was used, starting with ∼500 ng RNAs that were treated with tobacco acid pyrophosphatase to remove triphosphate at 5′ transcript ends and purified on acrylamide gel before and after the adaptor ligation step. The 3′ adaptor was the Universal miRNA cloning linker (NEB). For large RNAs, the amount of starting RNAs was ∼200 ng, and a fragmentation step by zinc during 8 min was included, after the Illumina procedure. The size of selected inserts was 20–120 nt for short RNA libraries and 50–120 nt for long RNA libraries from cultured bacteria and 150–250 nt for long RNA libraries from nodules. Libraries were sequenced either in paired end or in single end (Table 1). Raw sequence data were submitted to the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (Accession GSE44083).

Table 1.

RNA-Seq libraries used for annotation

| GEO sample code | RNA samples | RNA fraction | Biological replicate number | Sequencing process | Number of unambiguously mapped reads or paired-reads |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSM1078108 | Nodule | Long | 1 | pe 2 × 54 nt | 79 339 |

| GSM1078109 | Nodule | Long | 2 | pe 2 × 54 nt | 103 025 |

| GSM1078110 | Nodule | Long | 3 | pe 2 × 54 nt | 55 825 |

| GSM1078111 | Nodule | Short | 1 | pe 2 × 54 nt | 785 009 |

| GSM1078112 | Nodule | Short | 2 | pe 2 × 54 nt | 1 503 684 |

| GSM1078113 | Nodule | Short | 3 | pe 2 × 54 nt | 1 465 610 |

| GSM1078114 | Bacteria mid-exponential phase | Long | 1 | se 1 × 50 nt | 4 158 264 |

| GSM1078115 | Bacteria mid-exponential phase | Long | 2 | se 1 × 50 nt | 4 154 232 |

| GSM1078116 | Bacteria mid-exponential phase | Long | 3 | se 1 × 50 nt | 2 873 524 |

| GSM1078117 | Bacteria mid-exponential phase | Short | 1 | pe 2 × 50 nt | 4 792 283 |

| GSM1078118 | Bacteria mid-exponential phase | Short | 2 | pe 2 × 50 nt | 5 390 729 |

| GSM1078119 | Bacteria mid-exponential phase | Short | 3 | pe 2 × 50 nt | 9 061 874 |

| GSM1078120 | Bacteria stationary phase | Long | 1 | se 1 × 50 nt | 2 102 607 |

| GSM1078121 | Bacteria stationary phase | Long | 2 | se 1 × 50 nt | 3 171 844 |

| GSM1078122 | Bacteria stationary phase | Long | 3 | se 1 × 50 nt | 2 953 260 |

| GSM1078123 | Bacteria stationary phase | Short | 1 | pe 2 × 50 nt | 11 368 031 |

| GSM1078124 | Bacteria stationary phase | Short | 2 | pe 2 × 50 nt | 5 960 882 |

| GSM1078125 | Bacteria stationary phase | Short | 3 | pe 2 × 50 nt | 5 559 756 |

All RNA samples were depleted in ribosomal RNA using the RiboMinus™ protocol and separated in short (<200 nt) and long (>200 nt) fractions. Note that nodule libraries contain a mixture of S. meliloti and M. truncatula transcriptomes. Figures indicated here correspond to S. meliloti sequence reads only.

pe, paired ends; se, single end.

2.6. Read mapping

Reads were mapped to the genome using the procedure as described in Supplementary Materials and Methods. For paired-end reads, all positions between the two reads were considered as transcribed. All transcription data can be visualized in the genome browser (https://lipm-browsers.toulouse.inra.fr/gb2/gbrowse/GMI11495-Rm2011G).

2.7. Semi-conditional random field and associated features

The mathematical model of semi-conditional random field (CRF)43 has been used for gene finding in the eukaryotic gene finders, such as CRAIG44 and CONRAD,45 and implicitly used in EuGene from its creation. The semi-CRF model in EuGene-P is used to define an optimal segmentation of each strand of the genomic sequence into a succession of biologically meaningful regions. For one strand, the segmentation is defined by a succession of regions s= (s1 … sq). Each region si = (bi, li, ti) starts at position bi, has length li and labels ti. A label can be any of {IG, UTR5′, UIR, UTR3′, ncRNA, CDS1, CDS2, CDS3, CDS1:2, CDS2:3, CDS1:3}, where IG stands for intergenic, UTR5′, UIR and UTR3′ for untranslated regions of coding genes, ncRNA for non-coding RNA genes, CDSi for coding regions in frame i and CDSi:j for overlapping coding regions in frame i and j. See Fig. 1 for an example.

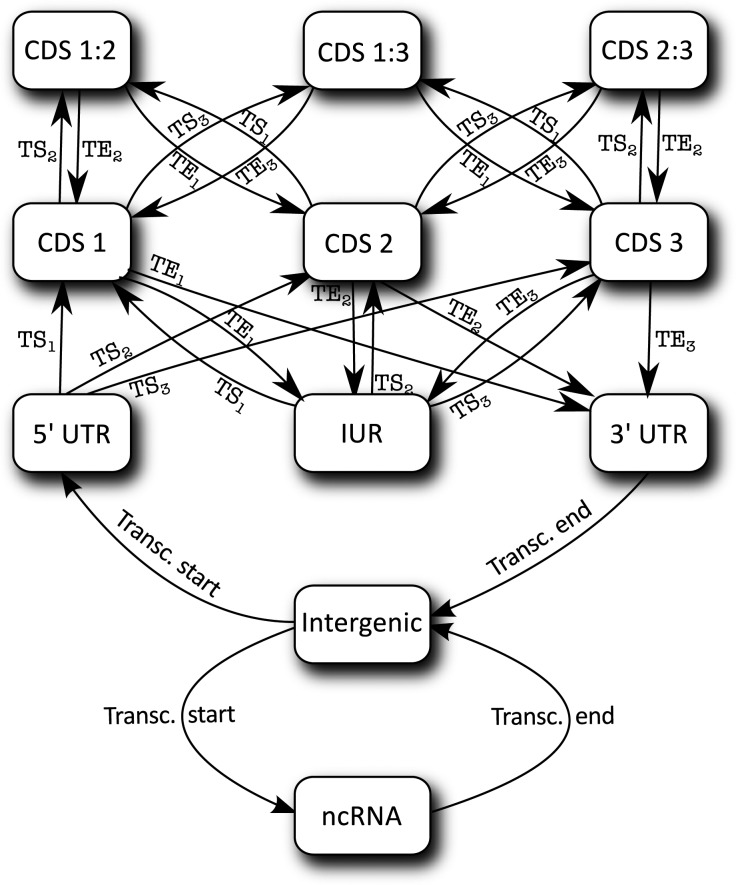

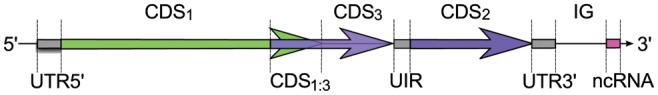

Figure 1.

A prokaryotic genomic sequence and the corresponding annotation defined as a sequence of typed regions. Each region has a specific label (or state) that defines its type. Beyond coding regions (e.g. CDS1) and intergenic regions (IG), an annotation may identify untranslated transcribed regions at the extremities of coding transcripts (5′ and 3′ UTRs), untranslated internal regions (or UIR, between two CDSs in a transcript) and ncRNA genes. Specific region types are also used to label overlapping CDSs. In this figure, the region labelled CDS1:3 corresponds to the overlap of a CDS in frame 1 with another CDS in frame 3.

The linear semi-CRF model computes the score of a segmentation (s1, …, sq) of a given input sequence as a linear combination of functions representing individual features of the segmentation. Each feature scores a region si based on its length li, its label ti, the label of the previous segment ti−1 and some evidence x (including the DNA sequence). EuGene-P relies more specifically on three types of features:

Contents features,

, score the fact that a region si has received label ti. For example, if the nucleotides in the region si appear in an alignment with a known protein, a ‘protein alignment’ feature will score positively if the associated label ti represents a coding region in the frame/strand indicated by the alignment.

, score the fact that a region si has received label ti. For example, if the nucleotides in the region si appear in an alignment with a known protein, a ‘protein alignment’ feature will score positively if the associated label ti represents a coding region in the frame/strand indicated by the alignment.Signal features,

, score the fact that a region si with label ti starts at position bi after a region with label ti−1. For example, a ‘RNA-Seq sharp depth upshift’ feature will score positively if si−1, labelled as an intergenic region, is followed by si defining a transcribed region, and a sharp upshift in the transcription level is observed on mapped RNA-Seq around position bi.

, score the fact that a region si with label ti starts at position bi after a region with label ti−1. For example, a ‘RNA-Seq sharp depth upshift’ feature will score positively if si−1, labelled as an intergenic region, is followed by si defining a transcribed region, and a sharp upshift in the transcription level is observed on mapped RNA-Seq around position bi.Length features,

, score the fact that a segment si has a given length. A typical example would be a feature scoring against extremely short CDSs.

, score the fact that a segment si has a given length. A typical example would be a feature scoring against extremely short CDSs.

Each feature can be understood as generating votes in favour of some annotations. After a learning phase, each feature receives a weight representing a ‘confidence’. The annotation that collects the maximum weighted sum of votes is considered as the optimal prediction. The usual probabilistic interpretation of CRFs, the formal definition of all features used inside EuGene-P and associated training and prediction algorithms are described in Supplementary Materials and Methods.

2.8. Transcriptome analysis

Differential expression of identified genes was calculated with R v2.13.0 using DESeq v1.4.146 available in Bioconductor v2.8. DESeq utilizes a negative binomial distribution for modelling read counts per transcript and implements a method for normalizing the counts. Variance was estimated using the per-condition argument. P-values are adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini and Hochberg method.47

2.9. Quantitative RT-PCR analyses

Reverse transcription was performed using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) with random hexamers as primers. RNA samples isolated from at least three independent experiments were tested for each condition. Real-time PCRs were run on a LightCycler system (Roche) using the FastStart DNA MasterPLUS SYBRGreen I kit (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

For gene expression normalization, six reference genes were selected from the RNA-Seq data of the current study, on the basis of their similar levels of expression in both culture conditions (exponential and stationary growth phases) and M. truncatula nodules. The expression level of these genes was then examined by qRT-PCR in wild-type and rpoE2 mutant strains grown at 28 and 40°C, and expression data were computed using the NormFinder application.48 SMc00519 and SMb21134 were found as the more stably expressed genes by NormFinder and were therefore used as references for qRT-PCR normalization in our conditions. Oligonucleotides sequences used for PCR are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

3. Results

3.1. A new integrative annotation tool for prokaryotic genomes

One of the main results of this work is the definition of an integrative gene finder for prokaryotic gene prediction, allowing automatic incorporation of various sources of evidence in the prediction process, including oriented RNA-Seq data. The produced annotation not only accounts for statistical properties of observed open reading frames, but also for consistency with a variety of experimental data, thus minimizing subsequent manual expert annotation work.

We designed EuGene-P on the basis of the eukaryotic gene finder, EuGene.14,20 EuGene is able to incorporate the various types of information for enhancing its predictive power and has been used for the annotation of several genomes.21–27 As all recent integrative gene finders, EuGene does not rely on a full generative probabilistic model, such as Hidden Markov Models,49 that would require the expensive and unrealistic probabilistic modelling of all dependencies between the available information, but on a dedicated discriminative model. Formally, EuGene-P as EuGene can be described as semi-linear CRF-, or SL-CRF-,43 based predictor. A CRF is a variant of Markov random fields, aimed at capturing the conditional probability of a succession of unknown discrete random variables y=(y1 … yn) given observed variables x (the available evidence). From such a model, the values of the unknown variables y can be reconstructed as the most probable ones given the available evidence x. In gene finding, the genomic sequence and the available information (mapped reads, other similarities …) will be represented as the evidence x. The unknown (or hidden) variables y are used to represent structural annotations. We therefore associate one variable yi with every base in the sequence. The variable yi specifies the annotation label (or state) of the base at position i (inside a CDS, an intergenic region …). In eukaryotic genomes, despite the accumulating evidence of overlapping functional regions, existing gene finders usually assume that each base belongs to just one type of region. The above model, with one variable yi per base, is perfectly suitable to perform the gene prediction on both strands simultaneously. In gene-dense prokaryotic genomes, overlapping functional regions is a rather frequent event. Genes can overlap with neighbouring genes on either strand. The genomic model we chose is therefore an unusual stranded model. This model describes how genes appear on one strand, independently of the other.

Formally, we have to enumerate the list of possible states for a nucleotide in an annotation. As shown in Fig. 1, since we restrict ourselves to a single strand, a typical prokaryotic sequence will contain bases belonging to either an intergenic region (denoted as IG), a transcribed non-translated region of a coding gene (denoted as UTR5′, UIR or UTR3′ depending on its location in the gene), a ncRNA gene (denoted as ncRNA), a non-overlapping CDS region in a given coding frame i (denoted as CDSi) or a region where two CDS in different coding frames i and j overlap (denoted as CDSi:j).

Overall, each variable yi, representing possible annotations for nucleotide i, may take 11 different states. Such states cannot appear arbitrarily in the genome sequence. For example, a CDS must start and end at specific codons. The CRF model can capture gene structures described as simple automaton. The automaton used in EuGene-P is described in Fig. 2. Transitions between possible states in the automaton correspond to the occurrence of specific biological signals in the sequence. Transcription Starts and Transcription Ends denote the start and end of transcripts (containing coding genes or ncRNA genes), whereas Translation Starts and Translation Ends (denoted as TSi and TEi, respectively, where i is the frame of the corresponding codon in the sequence) enable to, respectively, start or end a CDS inside a transcript and possibly inside another CDS in a different frame. Finally, the conditional probability distribution that relates the evidence in x and possible annotations in y must be described. In CRF, this is done through a set of features. Every type of experimental or statistical evidence is represented by one (or more) feature. A feature is a small mathematical function that uses some available evidence to vote in favour of (or against) the prediction of specific elements. For example, a ‘protein similarities’ feature would vote in favour of CDS prediction in the regions that have similarities with known proteins. A precise definition of the different features available in EuGene-P is given in Materials and Methods. Once the set of features used for gene finding is fixed, the CRF model can be trained. This training process computes a multiplicative factor for each feature that determines a feature-specific confidence. The prediction is then in charge of finding the annotation that has maximum conditional probability. This is the prediction that accumulates most support from all features. Overall, the mathematical model and associated software provide a qualitative improvement in terms of its abilities in predicting TSSs, untranslated transcribed regions, overlapping CDSs, ncRNA genes and antisense genes.

Figure 2.

The different states and possible transitions between these states used inside EuGene-P.

3.2. Generation of high-quality Sinorhizobium meliloti 2011 genome and transcriptome sequencing data

The genome sequence of the streptomycin-resistant derivative of S. meliloti strain 2011 was generated using a combination of 454 (Roche) and Solexa (Illumina) technologies that provided a total coverage of ∼190 genome equivalents. The assembly of the complete genome sequence was guided by the S. meliloti 1021 sequence that was determined previously.31 The comparison of these two DNA sequences revealed 463 polymorphisms, including 332 SNPs, 119 Indels and 12 large deletions or insertions (>10 bp; Supplementary Table S3). In addition to these differences, a 3564-nt region was specifically present in the chromosome of Sm2011 but not in Sm1021. This insertion, located between SMc03253 and SMc03254, was checked and confirmed by PCR amplification. This region contains a new gene, referred to as SMc06990, encoding a glutamine synthetase domain fused to a putative carbamoyl-phosphate synthase large chain ATP-binding protein, an enzyme that catalyzes the production of carbamoyl phosphate, which can be subsequently employed in both pyrimidine and arginine biosyntheses,50 as well as the SMc06992 gene which is a duplication (100% identical) of the SMc03253 gene preceded by two copies of its promoter region. The promoter region of SMc03253 was previously shown to be a duplication of the whole promoter region of fixK, a gene whose expression is controlled by the key symbiotic transcription regulator FixJ.51 Sanger DNA sequencing of 71 polymorphic regions including 64 putative frameshifts showed that 55 of them were actually errors on the reference sequence Sm1021, whereas eight were errors on the Sm2011 sequence and only eight were real polymorphisms (Supplementary Table S4). These results suggest that presumably only ∼10% of the 463 polymorphisms are real (most being errors in the Sm1021 sequence).

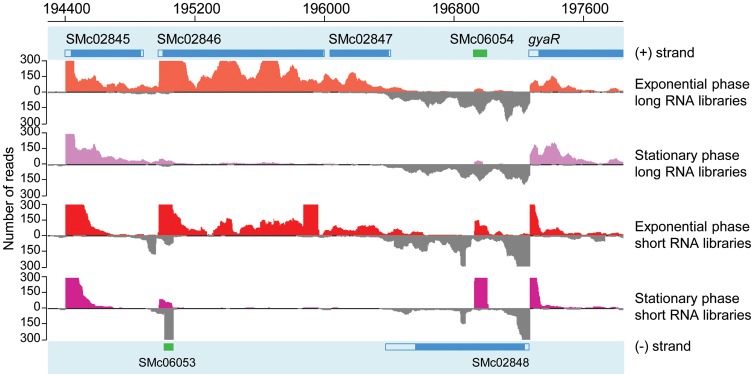

To obtain a global view of the transcriptome of Sm2011, RNAs were prepared from bacteria grown in three very different physiological conditions to cover a large number of expressed genes. These include RNAs extracted from bacteria grown in liquid cultures (in both exponential and stationary growth phases) and from 10-day-old nodules in which bacteria were differentiated in nitrogen-fixing bacteroids.52 For each condition, three biological replicates were performed to assess data reproducibility and reliability, and short (<200 nt) and long (>200 nt) RNA fractions were separately analysed. RNA samples were depleted in both ribosomal RNAs and the highly abundant tRNA-Ala using a S. meliloti-specific capture set of oligonucleotides and were sequenced using the stranded Illumina protocol.53,54 This protocol, based on ligation of adapters directly to the 3′ and 5′ ends of the RNA molecules, has the advantage of preserving the information about the transcript orientation. The RNA-Seq libraries generated in this study are listed in Table 1. The resulting sequences were mapped onto the S. meliloti genome sequence. RNA-Seq data appeared to be highly reproducible as shown in Supplementary Fig. S1 (Pearson correlation values varied from 0.899 to 0.998 between biological replicates). Of the 6308 S. meliloti annotated CDSs (see below), the expression of 5717 (90%) was detected in at least one experimental condition [raw expression level summed in the six libraries (short and long) of one condition was above 50 reads]. The number of mapped reads per nucleotide (summed values from triplicates) was visualized using the Apollo interface.55 Figure 3 illustrates a 3-kb region of the genome showing short and long RNAs in two conditions. The expression profiles of bacteria grown in exponential and stationary phases were compared with two previous studies performed in similar conditions, but based on oligonucleotide microarrays.30,39 Among the 804 genes found to be up-regulated in stationary phase in any of these studies, 631 genes (78%) were consistently found in our study to be up-regulated in the stationary phase (>2-fold, P < 0.05) either in the short or long RNA libraries. This percentage is similar to the percentage of common up-regulated genes found in the two microarray studies (80%), which attest to the good quality of our RNA-Seq data.

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of a genomic region in Apollo. Apollo represents the annotation on both strands (upper and lower part of the figure) as well as the expression level of the mapped RNA-Seq data from short and long RNA libraries in exponential and stationary growth phase conditions. Reads mapped on the plus strand are shown in colour, and reads mapped on the minus strand are in grey. Y-axis represents the number of reads summed from triplicates. The upper limit was set at 300 reads. This region contains several annotated non-coding (in green) and protein-coding (in blue) genes, full blue squares correspond to CDSs and open blue squares correspond to 5′ and 3′ UTRs.

3.3. Annotation of the Sinorhizobium meliloti 2011 genome using EuGene-P

EuGene-P inherits from EuGene its ability to integrate a variety of data. Selecting the most significant or informative sources of evidence is highly beneficial for the quality of the final annotation. We decided to use:

Similarities with known protein sequences modelled as a dedicated feature that votes for the prediction of coding regions in the corresponding coding frame (see Supplementary Materials and Methods). To identify similarities, we used the SwissProt database as a reliable general source of information for protein similarities. In addition, we used the proteome of the Sm1021 (set of all the protein sequences obtained by translating all CDS of the Sm1021 annotation) as a more specific source of information.

Mapped RNA-Seq data that indicate transcription activity. For transcribed sequences, we used RNA libraries of Sm2011 in exponential or stationary growth conditions and libraries of S. meliloti-colonized M. truncatula nodule tissues. All reads were mapped to the S. meliloti genome (Table 1). The absolute expression level and the changes in relative expression levels were each exploited in a specific feature. The absolute expression level was used as an evidence of transcribed regions, while abrupt changes in expression, captured by the derivative of the log-level of the expression, indicate a possible TSS.

Interpolated Markov models derived from coding potential to help identifying coding genes. The 3-periodic Markov models were estimated on CDSs from a subset of the genes in the Sm1021 annotation. Those genes have a specific (non-automatic) gene name, indicating that they have gone through expert annotation. Because they are known to have different statistical compositions, one coding model was estimated on pSymA genes and another coding model estimated on genes from pSymB together with the chromosome.

Output of ncRNA prediction programs to help identifying RNA genes from known families. The genomic sequence of S. meliloti was analysed using tRNAscan-SE v1.23 (April 2002) for transfer RNA detection, RNAmmer (February 2006) for ribosomal RNAs and rfam_scan v1.0.2 with Rfam v10.0 (1446 families, April 2010) for other known ncRNA gene families. This produced a set of genomic regions predicted as ncRNA genes. Each of these intervals was used in a feature favouring ncRNA prediction in the region that contains them.

The translation Start and Stop features are generic (see Materials and Methods). EuGene-P allows the user to parameterize the definition of Stop and Start codons to deal with unusual codon tables.

Overall, the purely automated annotation of Sm2011 produced a total of 6483 coding genes and 2040 ncRNA (including tRNAs and rRNAs) genes. This raw annotation was then submitted to manual checking, leading to possible curation of predicted CDSs, UTRs and ncRNAs. Manual modifications were done using Apollo55 to simultaneously visualize predicted elements and RNA-Seq expression levels in each condition (Fig. 3). Each elementary modification typically impacts several levels. For instance, corrections of 5′/3′ ends of UTRs often corresponded to the removal or creation of a new ncRNA. Typically, a predicted ncRNA that appeared close to 5′ was removed, and the UTR enlarged to include the corresponding region. Overall, 100 ncRNAs were removed in this way and the corresponding region included in a UTR (47 5′ UTRs and 53 3′ UTRs), while 87 UTRs (35 5′ UTRs and 52 3′ UTRs) were modified and new ncRNAs annotated. Around 13% of protein-coding genes and 29% of nc genes were modified as described in Table 2. However, it is important to note that nc genes and UTRs are difficult to discriminate even by expert analyses of RNA-Seq data. The manual curation led to the final annotation described in Table 3 and is available on the browser https://iant.toulouse.inra.fr/S.meliloti2011. In total 6308 protein-coding genes, 9 rRNAs, 55 tRNAs, 28 tRNAs precursors and 1876 ncRNAs were annotated.

Table 2.

Modifications performed on the automatic annotation during the manual curation process

| Type | 5′ ends | 3′ ends | CDS starts | CDS stops | Creations | Removals | Total number of modified genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coding genes | 350 | 275 | 135 | 2 | 19 | 194 | 835 |

| Non-coding genes | 31 | 151 | 180 | 252 | 604 |

Table 3.

Structural annotation of the S. meliloti 2011 genome

| CDSs (total number) | 6308 |

| New (when compared with Sm1021) | 125 |

| tRNAs | 55 |

| tRNA primary transcripts | 28 |

| rRNAs | 9 |

| ncRNAs | 1876 |

| Antisense to a protein-coding gene | 1281 |

| TSSs (total number) | 4840 |

| Predicted with high confidence | 4077 |

| Predicted with low confidence | 763 |

| Insertion sequences | 94 |

| Repeated elements | 618 |

| RIME | 209 |

| MOTIF | 256 |

| Sm-1 repeat | 21 |

| Sm-2 repeat | 8 |

| Sm-3 repeat | 4 |

| Sm-4 repeat | 73 |

| Sm-5 repeat | 47 |

3.4. Identification of a high number of putative non-coding RNAs in Sinorhizobium meliloti

The number of predicted ncRNAs was remarkable (Table 3). All of them, but five that were only detected by Rfam_scan, were supported by RNA-Seq expression data. Because the number of predicted ncRNAs was surprisingly high, we compared the automated raw predictions (before manual curation) with the set of 1102 small RNA candidates proposed in the previous RNA-Seq study of Schlüter et al.56 In that study, sRNAs candidates were arbitrarily classified as trans-encoded, cis-encoded sense, cis-encoded antisense and mRNA leaders. Cis-encoded sense regions have been reported as probable mRNA degradation products in Schlüter et al.56 We therefore excluded cis-encoded sense candidates from the comparison. We found that 77% of cis-encoded antisense candidates, 76% of trans-encoded candidates and 53% of mRNA-leader candidates were covered on >50% of their length by regions that were predicted as non-translated transcribed regions (UTRs or ncRNA regions together covering 503 kb or 3.8% of all chromosomal and plasmid strands).

Regarding the 1876 ncRNAs that were predicted after the manual curation, a large part (68%) was found located antisense to a protein-coding gene. Antisense RNAs overlap either with the 5′end (10%), the 3′end (19%) or the central part (71%) of the gene found on the opposite strand. These results strongly support the current findings that antisense transcription activity is more widespread in bacteria than initially thought.57,58

Our predicted ncRNAs displayed an average size of 107 nt, 94% ranging between 20 and 250 nt (Supplementary Fig. S2). This length distribution is consistent with the sizes of 50–348 nt observed by Schlüter et al.56 Besides the 55 tRNAs, the nine rRNAs and the five well-characterized ncRNAs (ffs, ssrS, ssrA, rnpB and incA), only 36 additional ncRNA were classified by Rfam_scan in 18 known ncRNA families (Supplementary Table S5). A majority of them has thus a completely unknown function. Interestingly, analysis of expression patterns indicated that a large part of predicted ncRNAs were differentially expressed (> or <2-fold, P < 0.01) between at least two of the three conditions studied: 152 were induced in symbiosis compared with free-living conditions while 1116 were induced, and 317 were repressed in stationary phase when compared with exponential growth phase (Supplementary Tables S6 and S7). These expression patterns support the idea that ncRNAs potentially play important regulatory functions in S. meliloti under these conditions.

Consistently with the study of Schlüter et al.56 intergenic repeated elements previously identified in the genome of S. meliloti, like the RIME, MOTIF or Sm-1 to Sm-5 repeats,59–61 were also transcribed and, thus, further increase the number of non-translated transcribed elements. Since reads corresponding to such repeated sequences could not be unambiguously mapped, it was difficult to estimate their relative expression levels and to determine whether they were all transcribed at a similar level.

3.5. EuGene-P identifies TSSs and efficiently delineates 5′ UTRs of mRNAs

The RNA-Seq protocol used here allowed us to precisely predict the 5′ ends of RNAs. This is related to the fact that, prior to library constructions, RNA molecules were treated with the tobacco acid pyrophosphatase that converts the 5′ triphosphate group of native transcripts into a 5′ monophosphate capable of ligation with oligonucleotide adaptors (see Materials and methods). This procedure enabled the sequencing of 5′ RNA ends with a very high precision and thereby the identification of probable TSSs. TSS prediction was based on the identification of abrupt changes in expression level as assessed by the approximation of the derivative of the expression level logarithm. In total, 4077 TSSs of protein-coding genes or nc genes were predicted with good confidence (clear changes in expression), whereas 763 were predicted with a lower confidence. Compared with the existing Sm1021 annotation,31 505 conserved CDSs had a modified start codon. This was a direct consequence of RNA-Seq data integration since the previously predicted start codon was usually located before the TSS predicted from RNA-Seq data, showing the interest of integrating RNA-Seq data for gene annotation.

To further evaluate EuGene-P predictions, we compared our data with TSSs experimentally mapped in previous studies. Prokaryotic transcription initiates in promoter DNA regions, defined by the presence of binding sites for a dissociable RNA polymerase subunit called sigma factor.62 To date, seven S. meliloti sigma factors (among 15) are known to be active in at least one of the experimental conditions tested here: the vegetative sigma factor (RpoD, or sigma 70) and the alternative sigma factors RpoN, RpoH1, RpoH2, RpoE2, RpoE1 and RpoE4.39,63–66 The TSSs of >100 promoters known or supposed to be controlled by either one of these sigma factors were experimentally mapped in various studies (Table 4). The TSSs annotated from the transcript 5′ ends mapped in the present study are in good agreement with these data, as 72% of the experimentally mapped TSSs match (±5 nt) our annotated TSSs (Table 4 and Supplementary Table S8). Several authors used the consensus promoter sequences deduced from these experimentally determined TSSs, combined or not with microarray or Affimetrix data, to predict >200 additional putative targets of these sigma factors (Table 4). The good congruence of these predictions with our data (74%) further strengthens our annotation (Table 4 and Supplementary Table S8). Note, however, that the number of correctly annotated TSSs was found to be positively correlated with the number of reads. Indeed, TSS annotations based on small numbers of reads appeared unreliable (24% of congruence), whereas TSSs covered by >50 sequencing reads were found to match more frequently the experimentally determined or in silico predicted TSSs (82 and 77%, respectively). Caution should therefore be taken with weakly expressed genes. Among other mis-annotated TSSs are those corresponding to processed transcripts, such as tRNA and rRNA, for which only 4 of 14 annotated TSSs match the predicted or experimentally determined TSSs (Supplementary Table S8). Finally, to evaluate the proportion of annotated 5′ends corresponding to actual TSSs, we reasoned that most of the promoters not analysed above should be recognized by the vegetative sigma factor RpoD. An in silico search revealed that >1/3 of them contain putative RpoD-binding sequences (Supplementary Table S9), as defined by MacLellan et al.67 Altogether, these observations therefore suggest that a large number of the annotated 5′ends indeed correspond to actual TSSs.

Table 4.

Congruence between TSS annotation and the published literature

| Fraction of annotated TSSa matching: |

||

|---|---|---|

| Experimentally mapped TSSb | In silico predicted TSSb | |

| RpoD | 22/27 | 63/89 |

| RpoH1 and/or RpoH2 | 45/67 | 49/69 |

| RpoE1 and/or RpoE4 | 3/4 | – |

| RpoE2 | 1/1 | 29/35 |

| RpoN | 3/4 | 5/6c |

All mapped or predicted promoter sequences are available in Supplementary Table S8.

aGenes for which no TSS was annotated in the current study were not retained for this table.

cAs the coordinates of RpoN TSS predicted by Dombrecht et al.94 were not described in their paper, we kept the promoters carrying the most obvious −24/−12 RpoN-binding sequences.

Interestingly, manual inspection of transcription data allowed the identification of 33 CDSs having different TSSs depending on experimental conditions (Supplementary Tables S6 and S7).

The length of annotated 5′ UTRs ranges between 1 and 839 nt and displays a median size of 45 nt, which is similar to the median length of 5′ UTRs observed in Escherichia coli (37 nt),68 Synechococcus elongatus (33 nt)2, Geobacter sulfurreducens (37 nt)1 or Agrobacterium tumefaciens (61 nt).69

3.6. Reappraisal of the Sinorhizobium meliloti RpoE2 regulon

The genome-wide determination of TSSs should make it possible to extend our knowledge of regulons by looking for the conserved binding sites of regulators in promoter regions. We tested this idea on the RpoE2 regulon. RpoE2 is an extracytoplasmic function sigma factor involved in the general stress response of S. meliloti and is activated under various conditions, including heat shock, salt stress or entry into stationary phase following nitrogen or carbon starvation.39 This sigma factor was found in previous studies to target <40 S. meliloti promoters.39,40,70,71 To re-evaluate the extent of the RpoE2 regulon, we screened all DNA regions located 5–11 nt upstream of 5′ transcript ends for the presence of the strictly conserved RpoE2-binding sequence (GGAAC N18–19 TT).39 We identified 108 transcription units that meet this criterion, including 26 putative ncRNAs (Supplementary Table S10). That most of these sequences correspond to genuine RpoE2-controlled promoters was validated by the following observations : (i) 30 of them were previously reported as RpoE2 targets,39,70,71 (ii) transcription from 86% of the newly identified promoters (67 of 78) was found in the current study as being up-regulated (>2-fold, P < 0.001) in stationary phase (a known RpoE2-activating condition; Supplementary Table S10) and finally (iii) using qRT-PCR, we confirmed that transcription from 6 of 6 randomly chosen promoters (four mRNAs and two ncRNAs) is up-regulated, either following a heat shock or entry in stationary phase (two RpoE2-activating conditions), in the wild type but not in a rpoE2 mutant strain (Supplementary Fig. S3). Altogether, these observations further validate TSS annotations predicted by EuGene-P and give a demonstration of its power to extend the knowledge of a given regulon.

4. Discussion

Through RNA sequencing, NGS technologies give access to prokaryotic transcriptomes with an unprecedented resolution and provide a massive amount of novel information on genome organization. In this work, we took advantage of data produced from the legume bacterial symbiont S. meliloti to develop a new bioinformatic tool that exploits transcription data for exhaustive annotation of prokaryotic genomes. The oriented RNA-Seq data that were produced from Sm2011 in stationary and exponential phases as well as in symbiotic condition have excellent reproducibility, with highly consistent triplicates and a good congruence when compared with previously published data. The analysis of both short and long fractions of RNAs enabled the identification of transcribed biological objects of small length, like ncRNAs and short CDSs, which could have been lost with usual RNA preparation protocols. The Sm2011 oriented RNA sequencing also showed a complex landscape of expression on both strands. Such complexity would have been completely hidden by non-oriented sequencing, possibly leading to biased expression level measurements as well as a poorer genome annotation.

Oriented RNA-Seq data give an opportunity to define a new generation of integrative prokaryotic genome annotation tools. In the area of prokaryotic genome annotation, existing NGS-related studies11 have focussed on the possibly increased level of sequencing errors associated with such technologies. Here, we showed that the quality of the Sm2011 genomic sequence obtained by NGS is comparable with, if not better than, the Sm1021 genomic sequence previously generated by Sanger sequencing.31 Using oriented RNA-Seq data, the EuGene-P proved to be able to automatically produce a complex annotation with novel coding and nc genes, including many antisense genes, untranslated 5′ and 3′ regions and precise mapping of 5′ TSSs. To the best of our knowledge, EuGene-P is the first prokaryotic gene finder that is able to predict a comprehensive genome annotation. The ability to predict highly overlapping functional regions is directly inherited from the strand-specific prediction process, which is itself consistent with oriented RNA-Seq data. Predicting genes on each strand independently has historically been considered as a bad idea given that the gene contents of the two DNA strands are highly correlated. However, ncRNA genes and specifically antisense genes blur this idea, which is already shaken by overlapping CDSs and transcripts. Strand-specific prediction and oriented RNA-Seq allow dealing with this complex situation directly.

The quality of the Sm2011 automatic annotation was validated by in-depth manual curation. A relatively limited number of manual modifications were made using Apollo for the simultaneous visualization of per-triplicated bank expression levels and annotation on both strands. The distinction between 3′ and 5′ UTRs and nearby ncRNA genes remains difficult and is still questionable even in the expert annotation. Beyond this, the resulting final annotation led to the definition of accurate gene structures, which is very useful for biologists to better understand the organization of genes and to characterize their function and regulation.

The number of predicted ncRNA genes is particularly high in S. meliloti, even though we cannot rule out that some of them encode peptides or small proteins. Most predicted ncRNA regions are consistently supported by RNA-Seq data. The fact that a large proportion of predicted ncRNAs are differentially expressed between the three physiological conditions analysed suggests that they are probably not artefacts introduced either by cDNA library preparation or by sequencing protocols. Moreover, the list of ncRNA genes predicted in a previous RNA-Seq study56 is also largely covered by our predicted nc transcripts, despite the fact that it represents only a small fraction of the genome. Among the 1876 predicted ncRNAs, 29 have been experimentally validated by northern blot or 5′-RACE analyses in previous studies.56,72–74 Beside tRNAs, rRNAs and the five well-conserved and well-characterized ncRNAs, 4.5S RNA (SRP, ffs), 6S RNA (ssrS), tmRNA (ssrA), the ribozyme RNase P (rnpB) and incA that mediates plasmid incompatibility phenotypes,75 36 ncRNAs belong to known families described in the Rfam database, whereas the remaining predicted ncRNAs could not be assigned to a given class. A lot of work thus remains to be done to validate the existence of predicted ncRNAs and to elucidate their function in S. meliloti. Interestingly, 454-sequencing of small ncRNAs of A. tumefaciens, a bacterium phylogenetically close to S. meliloti, recently revealed the presence of numerous small RNAs on all four replicons.69 The number of ncRNAs in S. meliloti would be even higher if widespread repeated elements like the RIME, MOTIF and Sm-1 to Sm-5 repeats59–61, that appeared to be highly transcribed elements, were taken into account. Similar repeated regions, like bacterial interspersed mosaic element and boxC DNA repeat elements, have also been shown to be transcribed in E. coli and to play key roles in transcription attenuation76 or mRNA stabilization.77,78 More recently, they have also been demonstrated to be involved in nucleoid morphology and chromosome formation and maintenance.79

A large proportion of S. meliloti ncRNAs were found to map antisense to annotated protein-coding genes. With oriented RNA-Seq data, antisense transcription now appears to be a common and widespread phenomenon in bacteria as recently reported for E. coli, in which 1005 antisense RNAs were identified,80,81 and Helicobacter pylori, in which 46% of CDSs are overlapping with at least one antisense RNA.82,83 Several mechanisms of the action of antisense RNAs in bacteria have been recently reviewed.84 They include the alteration of target RNA stability, the modulation (inhibition or activation) of translation, transcriptional interference and attenuation. Antisense RNA-mediated regulation thus likely appears as an important component of complex regulatory pathways controlling gene expression in bacteria. However, it was recently suggested by Nicolas et al.83 that some antisense RNAs can potentially arise from spurious transcription initiation or from imperfect control of transcription termination.

In this study, we also provided a detailed map of S. meliloti TSSs. This high-resolution TSS map is in agreement with previous in silico predicted or experimentally determined TSSs, in which 72% of validated TSSs matched our annotated TSSs by ±5 nt. These data will greatly facilitate the study of promoter regions, the identification of protein-binding motifs and the determination of regulons in S. meliloti. This was done here for the RpoE2 regulon that appears to be almost three times larger than previously determined using classical approaches.39

Oriented bacterial RNA-Seq data also unveil more complex mechanisms, such as alternative transcription starts, depending on the experimental condition (exponential or stationary phase). In our expression data, we identified 33 genes that displayed multiple TSSs. The frequency of multiple TSSs would have probably been higher if more physiological conditions had been analysed. Indeed, it was shown in E. coli and Bacillus subtilis that 35 and 46% of genes, respectively, have multiple TSSs.68,83 This type of adaptive behaviour is currently difficult to represent and raises new problems for automatic genome annotation and visualization.

In conclusion, we developed a new generic tool, EuGene-P, to automatically and accurately annotate prokaryotic genomes by integrating genome-wide experimental data, such as RNA-Seq data. This tool was used to re-visit the structural annotation of S. meliloti, providing a much more complete and comprehensive view of its genome architecture. The ability of EuGene-P to identify nc transcribed elements as well as to precisely map TSSs offers a new view of prokaryotic genomes and should greatly contribute to our understanding of gene regulation and function in bacteria.

Supplementary data

Supplementary Data are available at www.dnaresearch.oxfordjournals.org.

Funding

This work was supported by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche under grant ANR-08-GENO-106 "SYMbiMICS". This research was done in the Laboratoire des Interactions Plantes-Microorganismes, part of the Laboratoire d'Excellence (LABEX) entitled TULIP (ANR-10-LABX-41). F. Jardinaud was supported by the Institut National Polytechnique de Toulouse.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Bénédicte Bastiat for constructing the Sm2011 rpoE2 mutant, and Pierre Dupuy for help with qRT-PCR experiments. We thank Svetlana Yurgel and Michael Kahn (University of Washington) for exchanging the sequence data on putative frameshifts between the two S. meliloti strains, Sm2011 and Sm1021.

Footnotes

Edited by Dr Kenta Nakai

References

- 1.Qiu Y., Cho B.K., Park Y.S., Lovley D., Palsson B.O.,, Zengler K. Structural and operational complexity of the Geobacter sulfurreducens genome. Genome Res. 2010;20:1304–11. doi: 10.1101/gr.107540.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vijayan V., Jain I.H., O'Shea E.K. A high resolution map of a cyanobacterial transcriptome. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R47. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-5-r47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frank S., Klockgether J., Hagendorf P., et al. Pseudomonas putida KT2440 genome update by cDNA sequencing and microarray transcriptomics. Environ. Microbiol. 2011;13:1309–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weissenmayer B.A., Prendergast J.G.D., Lohan A.J., Loftus B.J. Sequencing illustrates the transcriptional response of Legionella pneumophila during infection and identifies seventy novel small non-coding RNAs. PloS ONE. 2011;6:e17570. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richardson E.J., Watson M. The automatic annotation of bacterial genomes. Brief Bioinform. 2013;14:1–12. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delcher A.L., Harmon D., Kasif S., White O., Salzberg S.L. Improved microbial gene identification with GLIMMER. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:4636–41. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.23.4636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delcher A.L., Bratke K.A., Powers E.C., Salzberg S.L. Identifying bacterial genes and endosymbiont DNA with Glimmer. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:673–79. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Do J.H., Choi D.K. Computational approaches to gene prediction. J. Microbiol. 2006;44:137–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hyatt D., Chen G.L., Locascio P.F., Land M.L., Larimer F.W., Hauser J. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aziz R.K., Bartels D., Best A.A., et al. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pareja-Tobes P., Manrique M., Pareja-Tobes E., Pareja E., Tobes R. BG7: a new approach for bacterial genome annotation designed for next generation sequencing data. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e49239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peterson E.S., McCue L.A., Schrimpe-Rutledge A.C., et al. VESPA: software to facilitate genomic annotation of prokaryotic organisms through integration of proteomic and transcriptomic data. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:131. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vallenet D., Belda E., Calteau A., et al. MicroScope—an integrated microbial resource for the curation and comparative analysis of genomic and metabolic data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D636–47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schiex T., Moisan A., Rouzé P. EuGene: an eukaryotic gene finder that combines several sources of evidence. In: Gascuel O., Sagot M., editors. Computational biology. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2001. pp. 111–25. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stanke M., Steinkamp R., Waack S., Morgenstern B. AUGUSTUS: a web server for gene finding in eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W309–12. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeh R.F., Lim L.P., Burge C.B. Computational inference of homologous gene structures in the human genome, Genome Res. 2001;11:803–16. doi: 10.1101/gr.175701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiehe T., Gebauer-Jung S., Mitchell-Olds T., Guigó R. SGP-1: prediction and validation of homologous genes based on sequence alignments. Genome Res. 2001;11:1574–83. doi: 10.1101/gr.177401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parra G., Agarwal P., Abril J.F., Wiehe T., Fickett J.W., Guigó R. Comparative gene prediction in human and mouse. Genome Res. 2003;13:108–17. doi: 10.1101/gr.871403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foissac S., Bardou P., Moisan A., Cros M.J., Schiex T. EuGene'Hom: a generic similarity-based gene finder using multiple homologous sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3742–45. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foissac S., Gouzy J., Rombauts S., et al. Genome annotation in plants and fungi: EuGene as a model platform. Curr. Bioinformatics. 2008;3:87–97. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abad P., Gouzy J., Aury J.M., et al. Genome sequence of the metazoan plant–parasitic nematode Meloidogyne incognita. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:909–15. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin F., Aerts A., Ahrén D., et al. The genome of Laccaria bicolor provides insights into mycorrhizal symbiosis. Nature. 2008;452:88–92. doi: 10.1038/nature06556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cock J.M., Sterck L., Rouzé P., et al. The Ectocarpus genome and the independent evolution of multicellularity in brown algae. Nature. 2010;465:617–21. doi: 10.1038/nature09016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grbić M., Van Leeuwen T., Clark R.M., et al. The genome of Tetranychus urticae reveals herbivorous pest adaptations. Nature. 2011;479:487–92. doi: 10.1038/nature10640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Argout X., Salse J., Aury J.M., et al. The genome of Theobroma cacao. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:101–08. doi: 10.1038/ng.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young N.D., Debellé F., Oldroyd G.E., et al. The Medicago genome provides insight into the evolution of rhizobial symbioses. Nature. 2011;480:520–24. doi: 10.1038/nature10625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sato S., Tabata S., Hirakawa H., et al. The tomato genome sequence provides insights into fleshy fruit evolution. Nature. 2012;485:635–41. doi: 10.1038/nature11119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moreau S., Verdenaud M., Ott T., et al. Transcription reprogramming during root nodule development in Medicago truncatula. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16463. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maunoury N., Redondo-Nieto M., Bourcy M., et al. Differentiation of symbiotic cells and endosymbionts in Medicago truncatula nodulation are coupled to two transcriptome-switches. PloS ONE. 2010;5:e9519. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Capela D., Filipe C., Bobik C., Batut J., Bruand C. Sinorhizobium meliloti differentiation during symbiosis with alfalfa: a transcriptomic dissection. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2006;19:363–72. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galibert F., Finan T.M., Long S.R., et al. The composite genome of the legume symbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti. Science. 2001;293:668–72. doi: 10.1126/science.1060966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meade H.M., Long S.R., Ruvkun G.B., Brown S.E., Ausubel F.M. Physical and genetic characterization of symbiotic and auxotrophic mutants of Rhizobium meliloti induced by transposon Tn5 mutagenesis. J. Bacteriol. 1982;149:114–22. doi: 10.1128/jb.149.1.114-122.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wais R.J., Wells D.H., Long S.R. Analysis of differences between Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021 and 2011 strains using the host calcium spiking response. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2002;15:1245–52. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2002.15.12.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krol E., Becker A. Global transcriptional analysis of the phosphate starvation response in Sinorhizobium meliloti strains 1021 and 2011. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 2004;272:1–17. doi: 10.1007/s00438-004-1030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yuan Z.C., Zaheer R., Finan T.M. Regulation and properties of PstSCAB, a high-affinity, high-velocity phosphate transport system of Sinorhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:1089–102. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.3.1089-1102.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Terpolilli J.J., O'Hara G.W., Tiwari R.P., Dilworth M.J., Howieson J.G. The model legume Medicago truncatula A17 is poorly matched for N2 fixation with the sequenced microsymbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021. New Phytol. 2008;179:62–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fujishige N.A., Kapadia N.N., De Hoff P.L., Hirsch A.M. Investigations of Rhizobium biofilm formation. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2006;56:195–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2005.00044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peltzer M.D., Roques N., Poinsot V., et al. Auxotrophy accounts for nodulation defect of most Sinorhizobium meliloti mutants in the branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis pathway. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2008;21:1232–41. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-21-9-1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sauviac L., Philippe H., Phok K., Bruand C. An extracytoplasmic function sigma factor acts as a general stress response regulator in Sinorhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 2007;189:4204–16. doi: 10.1128/JB.00175-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bastiat B., Sauviac L., Bruand C. Dual control of Sinorhizobium meliloti RpoE2 sigma factor activity by two PhyR-type two-component response regulators. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192:2255–65. doi: 10.1128/JB.01666-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barker D., Pfaff T., Moreau D., et al. Growing Medicago truncatula: choice of substrates and growth conditions. In: Mathesius U., Journet E.P., Sumner L.W., editors. The Medicago truncatula handbook. 2006. Noble foundation. ISBN 0-9754303-1-9. http://www.noble.org/MedicagoHandbook. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Journet E.P., El-Gachtouli N., Vernoud V., et al. Medicago truncatula ENOD11: a novel RPRP-encoding early nodulin gene expressed during mycorrhization in arbuscule-containing cells. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2001;14:737–48. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2001.14.6.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lafferty J.D., McCallum A., Pereira F.C.N. In: Brodley C.E., Danylu A.P., editors. Proceedings of the Eighteenth International Conference on Machine Learning, June 28–July 1, 2001; Williamstown, MA, USA. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc., Williams College; 2001. pp. 282–9. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bernal A., Crammer K., Hatzigeorgiou A., Pereira F. Global discriminative learning for higher-accuracy computational gene prediction. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2007;3:e54. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeCaprio D., Vinson J.P., Pearson M.D., Montgomery P., Doherty M., Galagan J.E. Conrad: gene prediction using conditional random fields. Genome Res. 2007;17:1389–98. doi: 10.1101/gr.6558107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anders S., Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate—a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andersen C.L., Jensen J.L., Orntoft T.F. Normalization of real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR data: a model-based variance estimation approach to identify genes suited for normalization, applied to bladder and colon cancer data sets. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5245–50. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mørk S., Holmes I. Evaluating bacterial gene-finding HMM structures as probabilistic logic programs. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:636–42. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thoden J.B., Huang X.Y., Raushel F.M., Holden H.M. Carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase—creation of an escape route for ammonia. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:39722–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206915200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ferrières L., Francez-Charlot A., Gouzy J., Rouillé S., Kahn D. FixJ-regulated genes evolved through promoter duplication in Sinorhizobium meliloti. Microbiology. 2004;150:2335–45. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vasse J., Debilly F., Camut S., Truchet G. Correlation between ultrastructural differentiation of bacteroids and nitrogen fixation in alfalfa nodules. J. Bacteriol. 1990;172:4295–306. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.8.4295-4306.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vivancos A.P., Guell M., Dohm J.C., Serrano L., Himmelbauer H. Strand-specific deep sequencing of the transcriptome. Genome Res. 2010;20:989–99. doi: 10.1101/gr.094318.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Levin J.Z., Yassour M., Adiconis X.A., et al. Comprehensive comparative analysis of strand-specific RNA sequencing methods. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:709–U767. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lewis S.E., Searle S.M., Harris N., et al. Apollo: a sequence annotation editor. Genome Biol. 2002;3:Research0082. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-12-research0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schlüter J.P., Reinkensmeier J., Daschkey S., et al. A genome-wide survey of sRNAs in the symbiotic nitrogen-fixing alpha-proteobacterium Sinorhizobium meliloti. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:245. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Del Tordello E., Bottini S., Muzzi A., Serruto D. Analysis of the regulated transcriptome of Neisseria meningitidis in human blood using a tiling array. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:6217–32. doi: 10.1128/JB.01055-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brantl S. Regulatory mechanisms employed by cis-encoded antisense RNAs. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2007;10:102–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Osteras M., Driscoll B.T., Finan T.M. Molecular and expression analysis of the Rhizobium meliloti phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (pckA) gene. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:1452–60. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.6.1452-1460.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Osteras M., Boncompagni E., Vincent N., Poggi M.C., Le Rudulier D. Presence of a gene encoding choline sulfatase in Sinorhizobium meliloti bet operon: choline-O-sulfate is metabolized into glycine betaine. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:11394–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Capela D., Barloy-Hubler F., Gouzy J., et al. Analysis of the chromosome sequence of the legume symbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti strain 1021. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:9877–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161294398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ghosh T., Bose D., Zhang X.D. Mechanisms for activating bacterial RNA polymerase. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2010;34:611–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ronson C.W., Nixon B.T., Albright L.M., Ausubel F.M. Rhizobium meliloti ntrA (rpoN) gene is required for diverse metabolic functions. J. Bacteriol. 1987;169:2424–31. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.6.2424-2431.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.De Lucena D.K.C., Puhler A., Weidner S. The role of sigma factor RpoH1 in the pH stress response of Sinorhizobium meliloti. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10:265. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Barnett M.J., Bittner A.N., Toman C.J., Oke V., Long S.R. Dual RpoH sigma factors and transcriptional plasticity in a symbiotic bacterium. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:4983–94. doi: 10.1128/JB.00449-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bastiat B., Sauviac L., Picheraux C., Rossignol M., Bruand C. Sinorhizobium meliloti sigma factors RpoE1 and RpoE4 are activated in stationary phase in response to sulfite. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e50768. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.MacLellan S.R., MacLean A.M., Finan T.M. Promoter prediction in the rhizobia. Microbiology. 2006;152:1751–63. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28743-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cho B.K., Zengler K., Qiu Y., et al. The transcription unit architecture of the Escherichia coli genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009;27:1043–U115. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wilms I., Overloper A., Nowrousian M., Sharma C.M., Narberhaus F. Deep sequencing uncovers numerous small RNAs on all four replicons of the plant pathogen Agrobacterium tumefaciens. RNA Biol. 2012;9:446–57. doi: 10.4161/rna.17212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fléchard M., Fontenelle C., Trautwetter A., Ermel G., Blanco C. Sinorhizobium meliloti rpoE2 is necessary for H(2)O(2) stress resistance during the stationary growth phase. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2009;290:25–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fléchard M., Fontenelle C., Blanco C., Goude R., Ermel G., Trautwetter A. RpoE2 of Sinorhizobium meliloti is necessary for trehalose synthesis and growth in hyperosmotic media. Microbiology. 2010;156:1708–18. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.034850-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Del Val C., Rivas E., Torres-Quesada O., Toro N., Jiménez-Zurdo J.I. Identification of differentially expressed small non-coding RNAs in the legume endosymbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti by comparative genomics. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;66:1080–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05978.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ulvé V.M., Sevin E.W., Cheron A., Barloy-Hubler F. Identification of chromosomal alpha-proteobacterial small RNAs by comparative genome analysis and detection in Sinorhizobium meliloti strain 1021. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:467. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Valverde C., Livny J., Schlüter J.P., Reinkensmeier J., Becker A., Parisi G. Prediction of Sinorhizobium meliloti sRNA genes and experimental detection in strain 2011. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:416. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.MacLellan S.R., Smallbone L.A., Sibley C.D., Finan T.M. The expression of a novel antisense gene mediates incompatibility within the large repABC family of alpha-proteobacterial plasmids. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;55:611–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Espeli O., Moulin L., Boccard F. Transcription attenuation associated with bacterial repetitive extragenic BIME elements. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;314:375–86. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Khemici V., Carpousis A.J. The RNA degradosome and poly(A) polymerase of Escherichia coli are required in vivo for the degradation of small mRNA decay intermediates containing REP-stabilizers. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;51:777–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Aguena M., Ferreira G., Spira B. Stability of the pstS transcript of Escherichia coli. Arch. Microbiol. 2009;191:105–12. doi: 10.1007/s00203-008-0433-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Macvanin M., Edgar R., Cui F., Trostel A., Zhurkin V., Adhya S. Noncoding RNAs binding to the nucleoid protein HU in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:6046–55. doi: 10.1128/JB.00961-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dornenburg J.E., DeVita A.M., Palumbo M.J., Wade J.T. Widespread antisense transcription in Escherichia coli. mBio. 2010;1:e00024–10. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00024-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Selinger D.W., Cheung K.J., Mei R., et al. RNA expression analysis using a 30 base pair resolution Escherichia coli genome array. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000;18:1262–8. doi: 10.1038/82367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sharma C.M., Hoffmann S., Darfeuille F., et al. The primary transcriptome of the major human pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 2010;464:250–5. doi: 10.1038/nature08756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nicolas P., Mäder U., Dervyn E., et al. Condition-dependent transcriptome reveals high-level regulatory architecture in Bacillus subtilis. Science. 2012;335:1103–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1206848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Georg J., Hess W.R. cis-Antisense RNA, another level of gene regulation in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2011;75:286–300. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00032-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Aneja P., Charles T.C. Poly-3-hydroxybutyrate degradation in Rhizobium (Sinorhizobium) meliloti: isolation and characterization of a gene encoding 3-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:849–57. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.3.849-857.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.MacLean A.M., White C.E., Fowler J.E., Finan T.M. Identification of a hydroxyproline transport system in the legume endosymbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2009;22:1116–27. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-22-9-1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Better M., Lewis B., Corbin D., Ditta G., Helinski D.R. Structural relationships among Rhizobium meliloti symbiotic promoters. Cell. 1983;35:479–85. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90181-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shatters R.G., Somerville J.E., Kahn M.L. Regulation of glutamine synthetase II activity in Rhizobium meliloti 104A14. J. Bacteriol. 1989;171:5087–94. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.9.5087-5094.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.De Bruijn F.J., Rossbach S., Schneider M., et al. Rhizobium meliloti 1021 has three differentially regulated loci involved in glutamine biosynthesis, none of which is essential for symbiotic nitrogen fixation. J. Bacteriol. 1989;171:1673–82. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.3.1673-1682.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Arcondeguy T., Huez I., Fourment J., Kahn D. Symbiotic nitrogen fixation does not require adenylylation of glutamine synthetase I in Rhizobium meliloti. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1996;145:33–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gao Y.F., Wu T., Zhu J.B., Yu G.Q., Shen S.J. Characterization of sequences downstream from transcriptional start site of Rhizobium meliloti nifHDK promoter. Sci. China C Life Sci. 1997;40:217–24. doi: 10.1007/BF02882051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Taté R., Riccio A., Merrick M., Patriarca E.J. The Rhizobium etli amtB gene coding for an NH4+ transporter is down-regulated early during bacteroid differentiation. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 1998;11:188–98. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1998.11.3.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dusha I., Austin S., Dixon R. The upstream region of the nodD3 gene of Sinorhizobium meliloti carries enhancer sequences for the transcriptional activator NtrC. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1999;179:491–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb08768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dombrecht B., Marchal K., Vanderleyden J., Michiels J. Prediction and overview of the RpoN-regulon in closely related species of the Rhizobiales. Genome Biol. 2002;3:Research0076. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-12-research0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.