Abstract

Objective

CaMKII contributes to impaired contractility in heart failure by inducing SR Ca2+-leak. CaMKII-inhibition in the heart was suggested to be a novel therapeutic principle. Different CaMKII isoforms exist. Specifically targeting CaMKIIδ, the dominant isoform in the heart, could be of therapeutic potential without impairing other CaMKII isoforms.

Rationale

We investigated whether cardiomyocyte function is affected by isoform-specific knockout (KO) of CaMKIIδ under basal conditions and upon stress, i.e. upon ß-adrenergic stimulation and during acidosis.

Results

Systolic cardiac function was largely preserved in the KO in vivo (echocardiography) corresponding to unchanged Ca2+-transient amplitudes and isolated myocyte contractility in vitro. CaMKII activity was dramatically reduced while phosphatase-1 inhibitor-1 was significantly increased. Surprisingly, while diastolic Ca2+-elimination was slower in KO most likely due to decreased phospholamban Thr-17 phosphorylation, frequency-dependent acceleration of relaxation was still present. Despite decreased SR Ca2+-reuptake at lower frequencies, SR Ca2+-content was not diminished, which might be due to reduced diastolic SR Ca2+-loss in the KO as a consequence of lower RyR Ser-2815 phosphorylation. Challenging KO myocytes with isoproterenol showed intact inotropic and lusitropic responses. During acidosis, SR Ca2+-reuptake and SR Ca2+-loading were significantly impaired in KO, resulting in an inability to maintain systolic Ca2+-transients during acidosis and impaired recovery.

Conclusions

Inhibition of CaMKIIδ appears to be safe under basal physiologic conditions. Specific conditions exist (e.g. during acidosis) under which CaMKII-inhibition might not be helpful or even detrimental. These conditions will have to be more clearly defined before CaMKII inhibition is used therapeutically.

Keywords: CaMKII, Excitation contraction coupling, Acidosis, Calcium handling, SR Ca2+-leak, SERCA function

1. Introduction

CaMKII is a multifunctional serine/threonine protein kinase. Its activation is Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent [1]. Different CaMKII isoforms (α, β, γ and δ) exist [2]. In the heart, CaMKIIδ and γ are expressed with CaMKIIδ being the predominant isoform [2,3]. In cardiomyocytes, CaMKII is a critical regulator of ECC, regulating L-type Ca2+-channels [4], SERCA activity by PLB phosphorylation [5], RyR function [6–8], as well as Na+- [9] and K+-currents [10].

CaMKII was suggested to be involved in pathophysiological remodeling of cardiomyocyte Ca2+-handling in heart failure [6,8,11–16], ventricular arrhythmogenesis [14,17,18], and atrial fibrillation [7,19]. Consequently, CaMKII-inhibition may be a novel therapeutic principle [8,15,20]. We [12] and others [21] showed that specific KO of CaMKIIδ is protective during pressure overload.

CaMKII was also suggested to play important physiological regulatory roles, e.g. in the force–frequency relationship, SR Ca2+-release, and adrenergic signaling [8,22,23]. In addition, CaMKII seems to be involved in maintaining intracellular Ca2+-transients and myocyte contractility during acidosis [5,24,25], a pathophysiologically relevant situation during cardiac ischemia. Yet, in vivo cardiac function in our first report was not impaired under physiological conditions [12] suggesting that ECC must be largely intact. Consequently, to investigate the mechanisms by which loss of CaMKIIδ may be compensated with respect to preserving physiological ECC and the possible effects on CaMKII regulatory mechanisms, we now performed extended mechanistic in vitro studies under basal conditions and upon stress (i.e. ß-adrenergic stimulation and acidosis).

2. Methods

All investigations conformed to the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” published by the US NIH (publication no. 85-23, revised 1996). For all experiments, investigators were blinded with respect to the genotype. All data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using Student's t-test for unpaired values, two-way repeated measures (RM) ANOVA (with Holm–Sidak or Fisher LSD as post hoc test) or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

2.1. Generation of isoform-specific CaMKIIδ-KO

The exact process of genetic ablation of CaMKIIδ was previously described [12]. Briefly, a ubiquitous KO was achieved by recombining LoxP sites flanking exons 1 and 2 of the CaMKIIδ locus in the germline.

2.2. Echocardiography

After anesthetization with avertin (0.01 ml/g i.p.), mice were investigated by 2D guided M-mode echocardiography (VS-VEVO 660/230, Visualsonics). In addition to ventricular dimensions measured using the standard leading edge convention, left ventricular fractional shortening and mass were calculated.

2.3. Isolation of cardiomyocytes

Myocytes were isolated as previously described [12,14]. Briefly, hearts were Langendorff-perfused with nominally Ca2+-free solution containing (in mM) NaCl 113, KCl 4.7, KH2PO4 0.6, Na2HPO4 × 2H2O 0.6, MgSO4 × 7H2O 1.2, NaHCO3 12,KHCO3 10, HEPES 10, taurine 30, BDM 10, glucose 5.5, phenol-red 0.032 for 4 min at 37 °C (pH 7.4). Then, 7.5 mg/ml liberase 1 (Roche), trypsin 0.6%, and 0.125 mM CaCl2 were added to the perfusion solution. Ventricular tissue was collected in buffer supplemented with 5% bovine calf serum and dispersed by cutting and pipetting. Ca2+ was reintroduced stepwise to 0.8 mM. For measurements, cells were freshly plated onto chambers coated with laminin.

2.4. Experimental solutions

NT was used consisting of (in mM) 140 NaCl, 4 KCl, 5 HEPES, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 1 CaCl2 (pH 7.4, 35 °C with NaOH). Fluo-3 and Fura-2 were diluted in NT with Pluronic F-127 0.2 mg/ml.

2.5. Epifluorescence experiments

Ca2+-epifluorescence and sarcomere length were measured as reported previously [12,14] at 35 °C. Myocytes were loaded with Fluo-3/AM (10 μM) for 20 min. Excitation was at 480 ± 15 nm, emission was at 535 ± 20 nm, and F/F0 was calculated. In parallel, myocyte contraction was investigated using a sarcomere length detection system (IonOptix). Myocytes were field-stimulated at 1, 2 and 4 Hz until steady-state was achieved. For more correct Ca2+-transient decline the time constant tau (τ) from the last Ca2+-transient before a 3 s pause was assessed. SR Ca2+-content was estimated by application of 10 mM caffeine (1 Hz) and τ of the caffeine-induced transient was calculated to estimate NCX-function. For semiquantitative assessment of cytosolic Ca2+-levels, cells were loaded with 10 μM Fura-2/AM for 15 min. Fura-2 fluorescence ratio was calculated by division of the signal obtained at 340 nm by that at 380 nm.

2.6. Iso experiments

To investigate adrenergic response, cells were treated with 4 nM Iso.

2.7. Ca2+-spark measurements

Myocytes were superfused with NT containing 3 mM Ca2+ (21 °C, pH 7.4) after incubation with Fluo-4/AM (10 μM, 15 min). Using a laser-scanning confocal microscope (LSM5, Zeiss), Fluo-4 was excited at 488 nm and emission was collected through a 505 nm long-pass filter. Fluorescence images were recorded in line-scan mode with 512 pixels per 38.4 μm wide scanline. Following 1 Hz stimulation, Ca2+-spark frequency (CaSpF) was measured at resting conditions and normalized to myocyte width and scanning interval (1/100 μm/s). Spark fluorescence was averaged over a 30 pixel (2.25 μm) wide window, meaning that spark width is represented in the averaged signal. Ca2+-spark amplitude (F/F0) and decay characteristics were determined for each spark. Diastolic SR Ca2+-leak for sparking cells was calculated as the product of frequency, amplitude and time to 50% decay (rt50CaSp). Total diastolic SR Ca2+-leak is based on all myocytes investigated and consequently also includes cells with functional Ca2+-transients that had no Ca2+-sparks during the scan interval.

2.8. Acidosis experiments

Acidosis was induced by switching superfusion from pH 7.4 to NT with a pH of 6.75 to mimic intracellular ischemia with values of even lower than 6.5 [25,26]. Myocytes were monitored during early (∼1– 4 min) and late acidosis (∼5–10 min) [5]. CaMKII was inhibited using KN-93 (1 μM) vs. its inactive analogue KN-92 (1 μM).

2.9. Western blot

Hearts were homogenized in Tris buffer containing (in mM) Tris– HCl 20, NaCl 200, NaF 20, Na3VO4 1, DTT 1, 1% Triton X-100 (pH 7.4) and complete protease-inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Protein concentration was determined by BCA assay (Pierce Biotechnology). Denaturated tissue homogenates were subjected to Western blotting (4–15% gradient and 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels) using anti-phopho-CaMKII (1:1,000, Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-RyR2 (1:10000, Sigma-Aldrich), anti-phospho-RyR2-2809 (1:5,000, Badrilla), anti-phospho-RyR2-2815 (1:5,000, Badrilla), anti-SERCA2a (1:20,000, Affinity Bioreagents), anti-PLB (1:10,000, Millipore), anti-phospho-Ser-16 (1:10,000, Badrilla), anti-phospho-Thr-17 (1:10,000, Badrilla), anti-NCX (1:5000, Swant), anti-I-1 (1:2000, Novus Biologicals), anti-CSQ (1:20000, Affinity Bioreagents), and anti-GAPDH (1:20,000, Biotrend) antibodies. Chemiluminescent detection was done with SuperSignal West Pico Substrate (Pierce). Expression/phosphorylation levels are given as percent of WT levels and are either normalized to GAPDH or the respective reference protein.

2.10. CaMKII activity assay

Ventricular tissue lysates were prepared using extraction buffer containing (in mM) Tris–HCl 20, EDTA 2, EGTA 2, DTT 2 as well as complete protease-inhibitor cocktail (Roche). CaMKII activity was then measured using the SignaTECT CaMKII assay system (Promega). Briefly, lysates were incubated with reaction buffer (250 mM Tris– HCl, 50 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM DTT) and either activation buffer (5 mM CaCl2, 5 μM calmodulin, 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin) or control buffer (5 mM EGTA) also containing the bionitylated peptide substrate as well as 0.5 mM ATP and 0.5 μCi [γ−32P]ATP. Reactions were allowed for 3 min at 30 °C before being terminated by adding 7.5 M guanidine-HCl. Equal amounts of samples were blotted onto the kit's SAM2 biotin capture membrane and washed with 2 M NaCl and 1% H3PO4. Kinase activity was assessed by scintillation counting.

3. Results

3.1. Preserved baseline characteristics in CaMKIIδ-KO vs. WT mice

KO mice gained normal weight (male/female KO 25.2 ± 0.8/20.4 ± 0.9 g, n = 11/11 vs. male/female WT 27.1 ± 0.9/20.4 ± 2.0 g, n = 11/7) at 11 weeks of age. In the age-matched animals (KO 11.2 ± 0.2 weeks vs. WT 11.1 ± 0.5 weeks), heart weight/body weight was not different in KO compared to WT (Fig. 1A).

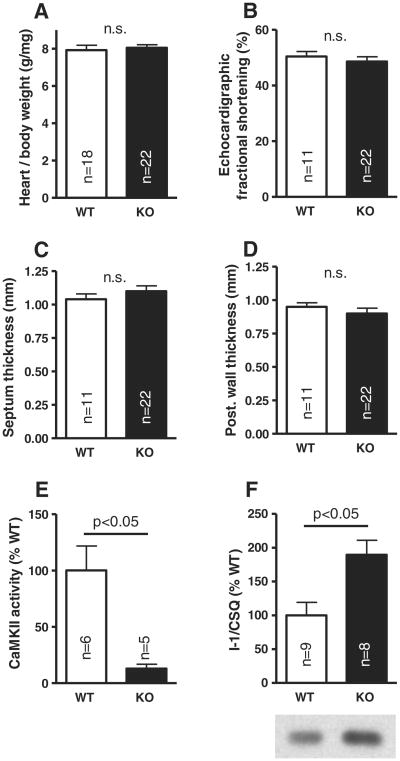

Fig. 1.

Unaltered biometric data and in vivo echocardiography in the KO: heart weight to body weight ratio (A), fractional shortening (B), septum (C), and posterior wall thickness (D). Significant reduction of total CaMKII activity in the KO (E), but increased I-1 protein expression (F).

Echocardiography showed no differences between KO and WT animals with respect to cardiac fractional shortening in vivo (Fig. 1B) or septum and posterior wall thickness (Figs. 1C and D). Calculated left ventricular mass per body weight was also not different (5.35 ± 0.20 mg/g in KO vs. 5.24 ± 0.30 mg/g in WT). Enddiastolic (3.47 ± 0.07 mm vs. 3.33 ± 0.14 mm in WT) and endsystolic diameters (1.80 ± 0.09 mm vs. 1.67 ± 0.11 mm in WT) were also unaltered.

3.2. Total CaMKII activity and I-1 expression in CaMKIIδ-KO mice

CaMKII activity in KO mice was reduced to 12.9 ± 3.9% compared to WT (p < 0.05; Fig. 1E). To further investigate possible compensatory mechanisms, we studied expression levels of I-1 and found this to be strongly increased to 190 ± 21% compared to WT (p < 0.05; Fig. 1F).

3.3. Single cell systolic function is not impaired under physiologic conditions

Ca2+-transient amplitudes at increasing stimulation rates were not impaired in KO cardiomyocytes (Fig. 2A). At 1 Hz stimulation frequency, Ca2+-transients (n = 60) were even slightly higher than in WT (n = 57) as previously described by us [12], while at increasing stimulation frequencies there were no more differences (Fig. 2B). Systolic fractional SR Ca2+-release during baseline stimulation (calculated as ratio of electrically stimulated Ca2+-transients through caffeine induced Ca2+-transients) showed no difference in the KO (69.0 ± 1.5%, n = 54 vs. 67.2 ± 1.8% in WT, n = 45). Single cell contractility (twitch amplitude) was slightly higher by trend, but not significantly altered at any stimulation frequency (Fig. 2C), corresponding to unaltered echocardiographic in vivo contractility.

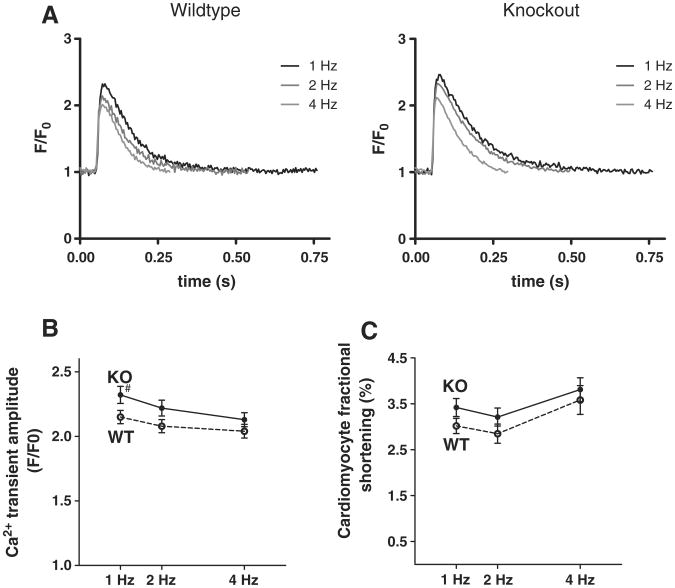

Fig. 2.

Isolated cardiomyocyte systolic function is not impaired under physiological conditions: as illustrated in original registrations (A), mean Ca2+-transient amplitudes (B) are not diminished in KO myocytes resulting in unimpaired cell contractility (C). Note that Ca2+ transient amplitude at 1 Hz was previously reported and was included here for comparison [12].

3.4. Single cell diastolic function is impaired upon CaMKIIδ-KO

Decay of the Ca2+-transient corresponds to cytosolic Ca2+-elimination during diastole, which is largely due to SR Ca2+-reuptake via PLB-regulated SERCA in mice [26]. Ca2+-transient decay was slightly, but significantly slower in KO myocytes (n = 60 vs. n = 43 in WT, Figs. 3A and B). Relaxation of the twitch, while also dependent on the mechanical properties of the myocyte, strongly depends on cytosolic Ca2+-decay. Consequently, twitch relaxation was also slower in KO (Fig. 3C). The reason for this appears to be reduced PLB phosphorylation at the CaMKII-specific Thr-17 site (Fig. 3D), while phosphorylation at the PKA-specific Ser-16 site (Fig. 3E), and PLB protein expression were unaltered (Fig. 3F). SERCA/PLB expression ratio (Fig. 3G) was significantly higher in KO mice, presumably compensating reduced PLB-phosphorylation with respect to SR Ca2+-reuptake. FDAR as assessed by the FDAR-ratio (τ of the Ca2+-transient at 4 Hz divided by τ at 1 Hz) was completely uncompromised with 75.5 ± 1.2% in the KO vs. 76.1 ± 0.9% in the WT (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Impaired diastolic function due to decreased PLB Thr-17 phosphorylation: original Ca2+-transients at 1 Hz (A) illustrate slower diastolic Ca2+-elimination in KO myocytes. Mean data for Ca2+-decay (τ, B) and twitch relaxation (rt 50%, C) underline impaired diastolic function. # indicates p < 0.05 vs. WT in Holm−Sidak post-hoc test. Western blots show significant less PLB Thr-17 phosphorylation (D), but not at Ser-16 (E), unchanged PLB expression (F), but increased SERCA/PLB ratio (G).

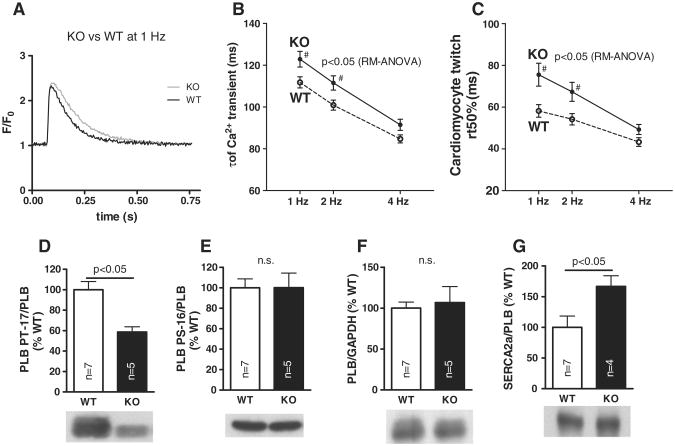

3.5. SR Ca2+-content is not altered in the face of decreased SR Ca2+-leak

Despite this impaired diastolic SR Ca2+-reuptake, SR Ca2+-content was largely unaltered in the KO (p = 0.11, Figs. 4A and B). We therefore assessed spontaneous SR Ca2+-sparks as a measure for SR Ca2+-leak (Fig. 4C). The percentage of sparking cells of all measured myocytes was significantly decreased in KO (p < 0.05, Fig. 4D), while Ca2+-spark frequency in these sparking cells was slightly, but not significantly, lower in the KO with 1.49 ± 0.13 sparks/100 μm/s (n = 55 sparking cells) compared to 1.66 ± 0.11 sparks/100 μm/s in WT (n = 148 sparking myocytes, p = 0.37). Ca2+-spark amplitude was not altered with 1.51 ± 0.02 F/F0 (n = 98 sparks) in KO vs. 1.52 ± 0.02 F/F0 (n = 128 sparks) in WT, and also time to 50% decay of the sparks was unaltered with rt50CaSp 23.43 ± 1.09 ms in KO and 22.00 ± 0.85 ms in WT sparks. In consequence, calculated total SR Ca2+-leak across all myocytes investigated (i.e. pooling those with and without sparks during the registration period) was clearly lower in the KO with 91.7 ± 4.7 F/F0/m compared to 156.6 ± 6.5 F/F0/m in the WT (Fig. 4E), while SR Ca2+-leak across only those cells that produced Ca2+-sparks, showed no difference with 532.2 ± 27.1 F/F0/m in KO compared to 554.6 ± 22.9 F/F0/m in WT (p = 0.53).

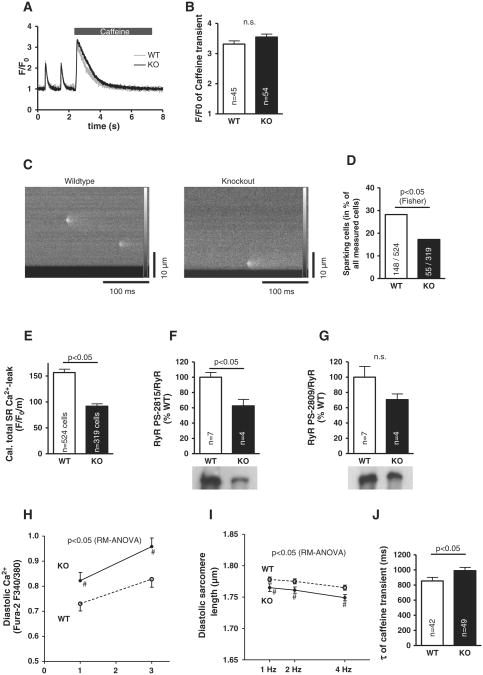

Fig. 4.

Despite decreased SR Ca2+-leak due to reduced RyR Ser-2815 phosphorylation, SR Ca2+-content is unaltered: Original registrations of caffeine-induced transients (A) as a measure of SR Ca2+-content which was unaltered (B). SR Ca2+-leak as assessed by Ca2+-sparks (C) is significantly lower in KO myocytes due to less cells showing Ca2+-sparks (D and E). Western blots show significantly reduced RyR Ser-2815 phosphorylation (F) but not at Ser-2809 (G). Fura-2 measurements show higher diastolic [Ca2+] (H) and consequently shorter diastolic sarcomere length (I) in KO myocytes. NCX function, as approximated by caffeine-induced Ca2+-transients (τ, J) is slightly impaired in KO myocytes.

Underlying this reduced SR Ca2+-leak, we found reduced RyR phosphorylation at the CaMKII-specific Ser-2815 site (Fig. 4F), while phosphorylation at Ser-2809 (Fig. 4G), which is mainly a target of PKA, was not significantly decreased in the presence of unaltered RyR expression (KO 139.8 ± 10.0% vs. WT 100.0 ± 19.3%).

Despite decreased SR Ca2+-leak, diastolic free Ca2+-levels were significantly higher in KO (n = 29) compared to WT myocytes (n = 23, Fig. 4H). This correlated with significantly shorter diastolic sarcomere lengths in KO vs. WT (Fig. 4I, KO n = 43-57, WT n = 39–60). These observations suggest that other mechanisms apart from SR Ca2+-leak must influence diastolic Ca2+ (and dominate over SR Ca2+-leak in this regard under physiologic conditions). Consequently, we investigated Ca2+-extrusion by NCX and found this to be significantly impaired in the KO (Fig. 4J). However, it appears that the mechanism for this was not a reduction of NCX expression, since this was not significantly altered in the KO (112.8 ± 8.0% vs. WT 100 ± 6.8%, n = 4 vs. n = 7).

3.6. Inotropic and lusitropic responses to adrenergic stimulation are intact

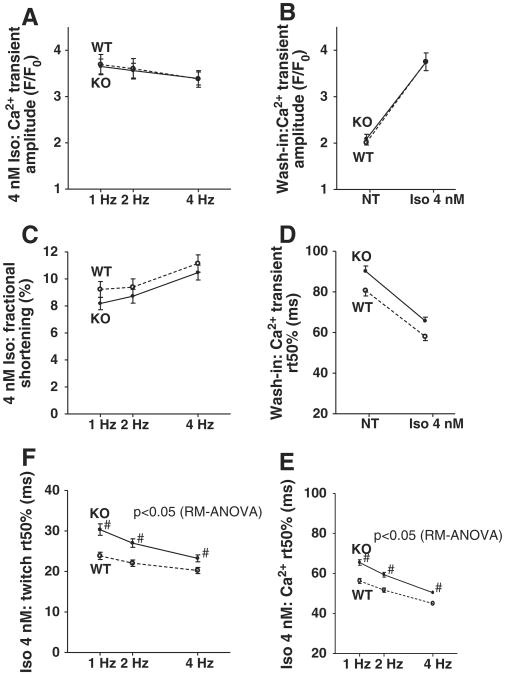

Upon adrenergic stimulation using Iso, both WT and KO showed significant inotropic responses and KO myocytes did not differ significantly from WT with respect to Ca2+-transient amplitudes (Fig. 5A, KO n = 46, WT n = 36; data from n = 17 vs. n = 11 wash-in experiments shown in Fig. 5B) or contractility (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Inotropic and lusitropic responses to adrenergic stimulation are intact: mean data for amplitudes (F/F0, B) and rt50Ca of Ca2+-transients (D) from Iso wash-in experiments, demonstrate preserved inotropic and lusitropic response in KO myocytes. This is also evident at different stimulation frequencies from mean data for Ca2+-transient amplitude (A), twitch amplitudes (C), Ca2+-transient decay (rt 50%, E) and twitch relaxation (rt 50%, F).

Lusitropic response to Iso as demonstrated in WT myocytes with clearly faster relaxation and cytosolic Ca2+-elimination was also present and strong in the KO (Fig. 5D, KO n = 17, WT n = 11). However, the slightly slower relaxation kinetics in the KO were also present under Iso stimulation and in fact were even slightly more pronounced in so far as post-hoc test now also showed significance for 4 Hz stimulation (Fig. 5E, KO n = 46, WT n = 36). Myocyte twitch relaxation under Iso was also slower in the KO for all frequencies investigated (Fig. 5F).

3.7. Recovery from acidosis requires CaMKIIδ

CaMKII activity is increased during acidosis where it is crucial in maintaining SR Ca2+-reuptake through PLB phosphorylation [25]. Since CaMKII activity is decreased and PLB phosphorylation reduced in the KO, we speculated that SR Ca2+-loading and resulting Ca2+-transients might be impaired during acidosis.

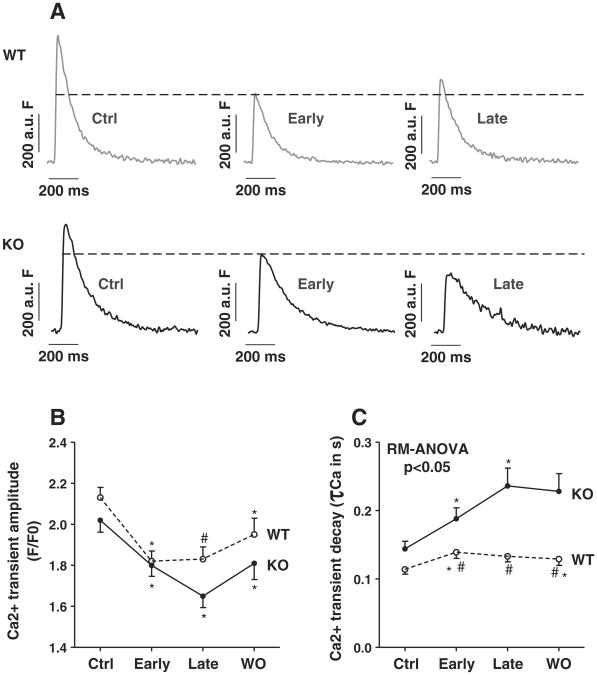

CaMKIIδ-KO (n = 41) and WT control myocytes (n = 49) showed decreased Ca2+-transient amplitudes during early acidosis (Figs. 6A and B, p < 0.05 vs. control, respectively). While WT myocytes maintained their Ca2+-transient amplitudes during late acidosis compared to non-acidic conditions, Ca2+-transients in KO cells decreased even further in late acidosis to ∼64% of control conditions (Figs. 6A and B, p < 0.05 between genotypes). This was associated with preserved relaxation properties in WT whereas KO myocytes showed progressively impaired relaxation, indicating decreased SR Ca2+-reuptake (Figs. 6A and C, p < 0.05 between genotypes).

Fig. 6.

Ca2+-transients and SR Ca2+-reuptake are impaired during acidosis: Representative Ca2+-transients in WT and KO myocytes (A). While Ca2+-transient amplitude increased in WT myocytes during late acidosis, it further decreased in KO myocytes. Mean data for Ca2+-transient amplitudes (F/F0, B) and decay (τCa, C). *p < 0.05 vs. previous phase, #p < 0.05 between genotypes using Fisher LSD post-hoc test. RM-ANOVA indicates two-way ANOVA testing for repeated measures.

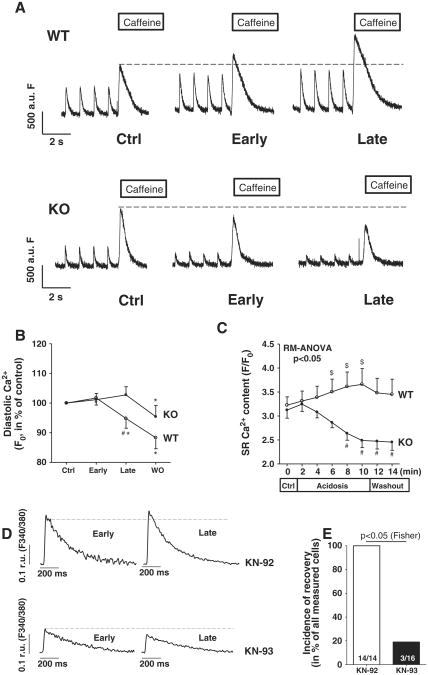

In line with this, diastolic F0 as an approximate measure for diastolic [Ca2+]i also showed divergent results between groups with a relative decrease of F0 in WT compared to an increase in KO myocytes (Fig. 7B, p < 0.05 between genotypes during late acidosis). Importantly, WT myocytes (n = 19) showed an increase in SR Ca2+-content during acidosis, whereas it dramatically decreased in the KO group (n = 16) (Figs. 7A and C, p < 0.05). We further confirmed the recovery to be a CaMKII-dependent effect by showing that recovery occurred in only ∼19% of WT myocytes treated with CaMKII-inhibitor KN-93 while recovery occurred in all myocytes treated with control substance KN-92 (p < 0.05, Figs. 7D and E).

Fig. 7.

SR Ca2+-content during acidosis is impaired due to diastolic Ca2+-overload: Representative Ca2+-traces show impaired SR Ca2+-loading in KO myocytes as compared to WT myocytes as acidosis progresses (A). Mean data for diastolic Ca2+ (B) and SR Ca2+-content (C). Abolished recovery of Ca2+-transients (D) during late acidosis during CaMKII-inhibition with KN-93 in WT cells. Recovery incidence in WT myocytes (E). $p < 0.05 vs. control conditions (Ctrl), *p < 0.05 vs. previous phase, #p < 0.05 between genotypes using Fisher-LSD post-hoc test.

4. Discussion

In the present study we investigated whether loss of CaMKIIδ affects basal cardiac function. Our results show that systolic function in vivo and in vitro is not compromised and that the response to ß-adrenergic stimulation in vitro is not diminished. SR Ca2+-leak seems to be reduced although SR Ca2+-load under basal conditions is largely unaltered. In contrast, diastolic function and SR Ca2+-reuptake appear to be compromised, leading to impaired recovery during acidosis. These functional data are supported by altered CaMKII-dependent phophorylation status of RyR and PLB and suggest that targeted inhibition of CaMKIIδ is possible without fundamentally altering basal ECC. This observation may be due to the fact that remaining CaMKII activity is sufficient to maintain physiologic regulatory roles of CaMKII under basal conditions, but not during pathophysiologic acidosis.

4.1. CaMKIIδ-KO myocytes have normal systolic but impaired diastolic function

Our data show normal systolic function both in vitro and in vivo under basal conditions and upon Iso-stress. One important point may be that relatively low basal CaMKII activity may contribute to the modest baseline phenotype. Likewise, sympathetic inotropy and lusitropy may not require strong CaMKII activation. For comparison, some parallel baseline studies were also done using mice from a different CaMKIIδ-KO line [21] and are described in the Supplement. That line exhibited similar WT vs. KO differences in Ca2+-handling to the mice used here. However, diastolic function as assessed by diastolic Ca2+-elimination and relaxation of isolated myocytes, is impaired. The molecular basis for this appears to be reduced PLB phosphorylation at the CaMKII-specific Thr-17 site, while there is no change in PKA-dependent PLB phosphorylation. Our results also show a higher SERCA/PLB ratio in the KO. However, this potential compensatory mechanism is not sufficient due to the slowed relaxation found in our study and we therefore conclude that the effect of much lower PLB phosphorylation dominates functionally. Of note, SERCA expression has vice versa been found to be lower in CaMKIIδC-overexpressing mice [6] and is a hallmark of heart failure allowing for the exciting possibility that CaMKII might be directly involved in SERCA regulation by excitation-transcription coupling.

Yet, invasive hemodynamic measurements in another mouse model of CaMKIIδ-KO had not shown alterations in relaxation [21]. But in contrast to our experiments these in vivo measurements were performed in the presence of hemodynamic preload, which will facilitate relaxation. In addition, heart rate in vivo is high in mice and the effects observed by us were strongest at lower stimulation frequencies. So while our data point to a potential impact of CaMKIIδ-KO on diastolic function in single cardiomyocytes, it seems that this apparently does not necessarily translate into detrimental hemodynamic consequences in vivo which may be a limitation of the present study.

Of note, the slower twitch relaxation in the KO appears to be slightly more pronounced than the slower Ca2+-transient decay. Conversely, while Ca2+-transient amplitudes are slightly increased in the KO, we found single cell contractility to be increased to a lesser extent and not significantly so. These differences in extent of [Ca2+]i vs. contraction might be due to the highly nonlinear nature of myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity or changes in myofilament function in the KO mice.

4.2. FDAR is not impaired in CaMKIIδ-KO

CaMKII was suggested to be central for FDAR. While there have been reports of impaired or absent FDAR upon CaMKII inhibition [27,28] these reports were challenged by others [29,30] and temporal dissociation between FDAR and CaMKII-activation has been shown [31]. Our data demonstrate that FDAR is not compromised by loss of CaMKIIδ (see also Supplemental Fig. II), suggesting that increasingly faster Ca2+-reuptake upon higher frequencies might be due to a CaMKIIδ-independent mechanism. Although CaMKII activity is decreased to 13% in the CaMKIIδ-KO (Fig. 1E), we cannot rule out the possibility that FDAR is mediated by another CaMKII isoform (e.g. CaMKIIγ which may compensate for loss of CaMKIIδ in FDAR).

Our data show that NCX function is slightly decreased in the CaMKIIδ-KO while enhanced NCX function was found in CaMKIIδC overexpressing mice [6]. In part, this reduced NCX function in the KO might contribute to slower Ca2+-elimination at low stimulation frequencies. Given the greater contribution of SERCA (∼90%) to diastolic Ca2+-elimination as compared to NCX (∼8%) [26], as well as the reduced NCX function observed, we believe that effects of PLB phosphorylation dominate over NCX effects with respect to diastolic Ca2+-decay. The reason for reduced NCX activity in our KO mouse is less clear, since NCX protein expression is unaltered. It is possible that modifications of NCX or a slight increase in [Na+]i[32] might be the reason for this apparent discrepancy. However, our results do not distinguish whether such changes might be directly due to CaMKIIδ or are rather secondary effects of the KO.

4.3. Reduced SR Ca2+-leak, but unaltered SR Ca2+-content and increased diastolic Ca2+ in CaMKIIδ-KO

Due to spontaneous SR Ca2+-release events occurring less frequently in KO-myocytes, we found total SR Ca2+-leak to be reduced under basal conditions (at least when also including cells with no sparks but regular Ca2+-transients). Our Western blot data indicate that reduced RyR phosphorylation, most importantly at the CaMKII-specific Ser-2815 site, may be the reason for this reduced SR Ca2+-leak. Diastolic SR Ca2+-leak is not only suggested to reduce SR Ca2+-content [6] and impair contractility [15] but also may be an important arrhythmogenic mechanism [14]. Despite lower SR Ca2+-leak, SR Ca2+-content was unaltered. We assume that this is because SERCA function is also lower, so that decreased SR Ca2+-loss might have been counter-balanced by decreased SR Ca2+-reuptake.Ithas been reported in another mouse model that reduced Ca2+-spark frequency in CaMKIIδ-KO upon TAC also did not lead to higher SR Ca2+-content [21] and we had also observed reduced SERCA function in KO vs. WT in our TAC model [12]. This is also interesting in so far as it had been speculated that preservation of SR Ca2+-content by reduction of SR Ca2+-leak could be a major protective mechanism in CaMKII-inhibition or -KO with respect to contractility. Apart from SR Ca2+-content, lower SR Ca2+-leak might also be protective with respect to arrhythmogenesis [14]. In any case, reduced CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation of the RyR can be assumed to be the cause for reduced SR Ca2+-leak in the KO, since the other explanation for reduced sparks – a lower SR Ca2+-load – can be excluded.

It is not clear why there are differences in the percentage of sparking myocytes, but this may simply be a statistical manifestation of the low spark rate (most myocytes had only 1–2 observed sparks during the scan interval). Thus the lower overall Ca2+ spark frequency and greater number of spark-free KO myocytes likely reflect a real decrease in diastolic SR Ca2+ leak. Notably, part of SR Ca2+ leak is not detectable as Ca2+ sparks [33], but such spark-independent SR Ca2+ leak was not assessed in these mice. However, we performed some parallel studies in another CaMKIIδ-KO mouse line [21] which included measurement of total SR Ca2+ -leak using the Shannon tetracaine induced shift method over a range of SR Ca2+ -loads [15]. Supplemental Fig. IIIC shows that CaMKIIδ-KO vs. WT mice showed lower leak at a given SR Ca2+ -load. In those CaMKIIδ-KO mice we also saw lower Ca2+ -spark frequency when normalized to SR Ca2+ -load (Supplement Fig. IIIB).

Interestingly, diastolic sarcomere length is shortened and diastolic free Ca2+-levels are increased in the KO. One typical cause of elevated diastolic Ca2+-levels (as found in heart failure) is increased SR Ca2+-leak. However, this is not the case in the current study. We rather believe that a combination of increased Ca2+-influx and reduced Ca2+-extrusion from the cytoplasm may be the reason for elevated Ca2+-levels: Our data show a reduction of NCX-activity, while there is also significantly increased L-type Ca2+-current associated with increased Cav1.2-expression [34]. Conversely, Cav1.2-expression is decreased by CaMKII overexpression [35]. This combination of increased Ca2+-influx and an impaired ability to eliminate Ca2+ by reduced Ca2+-extrusion (via NCX) and reduced SR Ca2+-reuptake might have caused a shift towards slightly higher Ca2+-levels in the cytosol in the KO. However, other Ca2+-handling pathways and buffering entities like sarcolemmal Ca2+-ATPase, mitochondria and myofilaments might also be involved. Also, a small increase in [Na+]i could elevate diastolic [Ca2+]i via effects on NCX function.

The discrepancy between the large effects on diastolic Ca2+ as compared to the small changes in diastolic sarcomere length might be because some of the diastolic [Ca2+]i rise would be below the threshold for myofilament activation. Altered myofilament properties or the use of mechanically unloaded myocytes could also contribute to that difference.

4.4. Stress response: preserved response to ß-adrenergic stress but impaired SR Ca2+-reuptake during acidosis

Our data demonstrate preserved inotropic and lusitropic effects of ß-adrenergic stimulation in the KO (see also [21]). In contrast, CaMKIIδ deficiency became functionally relevant during experimental acidosis, which may be of clinical relevance during myocardial infarction, ischemia-reperfusion, and even an acute increase in afterload that may cause subendocardial ischemia, which is likely accompanied by pH reduction. During the early phase of acidosis, low extracellular pH leads to an increased [H+]i which drives the Na+/H+-exchanger to extrude H+ from the cell in exchange with Na+. This causes an increase in [Na+]i. Na+ then gets exchanged for Ca2+ via the reverse mode of NCX so that diastolic [Ca2+]i rises [26]. Regarding our present study, it seems as if this early, NCX-dependent mechanism is not affected in the KO as diastolic Ca2+ rose in parallel to WT cells during early acidosis. During late acidosis, increased [Ca2+]i is known to activate CaMKII [25]. In healthy cardiac myocytes, CaMKII phosphorylates PLB at Thr-17 thereby partially reactivating depressed SR Ca2+-reuptake, which leads to an increase in SR Ca2+-content. Increased SR Ca2+-content ultimately causes the SR to release more Ca2+ per systole, so that progressively increasing Ca2+-transients help to partially overcome depressed myocyte contractility, a mechanism by which the cell can temporarily cope with clinically relevant situations such as myocardial ischemia. Furthermore, CaMKII-dependent enhanced SR Ca2+-filling contributes to keep diastolic Ca2+-levels within the physiological range. And indeed, all of these protective mechanisms [25,26] were present in control cells in the current study.

In contrast, in the CaMKIIδ deficient cells, there was a further increase in diastolic Ca2+ during late acidosis in the face of progressively slowed Ca2+-transients, which was in clear contrast to the partially reaccelerating Ca2+-transient decay in control cells. We believe that this most likely results from reduced CaMKII-dependent PLB phosphorylation in KO cells. Consequently, SR Ca2+-content progressively decreased during acidosis, which resulted in decreased Ca2+-transients and increased diastolic [Ca2+]i in KO cells. This inability of CaMKIIδ deficient cells to maintain contractile force could be clinically problematic in a pathophysiological setting such as acidosis or ischemia. Indeed, during myocardial ischemia, extracellular pH can fall well below 7.0 within minutes, reaching intracellular pH values of ∼6.5 [26]. Our current experimental model may be of relevance to that situation.

Our acidosis data seems to be in line with the generally impaired diastolic function observed in KO myocytes, only that under these specific stress conditions, affected diastolic function (SR Ca2+-reuptake) became functionally relevant also for systolic function: It therefore appears that this pathophysiological constellation reveals a necessity for CaMKIIδ activity for cardiomyocyte function and unmasks a crucial role for CaMKIIδ in preserving sufficient SR Ca2+-loading by facilitation of SERCA-activity during acidosis. Specifically, there is impaired systolic function (decreased Ca2+-transients) in the KO during acidosis due to the generally impaired diastolic function in this genotype (reduced recruitment of SERCA activity in acidosis) and an inability to recruit sufficient additional SERCA activity without CaMKIIδ. This hypothesis is further confirmed by our finding that pharmacological CaMKII-inhibition prevented recovery of Ca2+-transients from acidosis in WT animals. It appears that the CaMKII/PLB-pathway is critical for recovery from acidosis and that loss of CaMKIIδ cannot be compensated in this respect (e.g. by CaMKIIγ or enhanced SERCA expression).

4.5. Compensatory upregulation of I-1

While our CaMKII-activity assay showed a clear reduction of CaMKII-activity, phosphorylation levels of CaMKII-targets PLB and RyR were also reduced, but to a lesser extent. We found upregulation of I-1, which is an important inhibitor of protein phosphatase-1 activity, this way also regulating CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation of PLB [36] and RyR [37]. This mechanism may represent a novel link between Ca2+- and I-1 mediated β-adrenergic signaling.

4.6. Summary/perspective

In summary, basal systolic cardiomyocyte function under physiologic conditions does not require CaMKIIδ. As a caveat however, CaMKIIδ might have important functions under certain pathophysiologic conditions, since the ability of the cells to recover from acidosis was clearly impaired. We suggest that this is due to reduction of SERCA function recruitment by PLB phosphorylation in acidosis upon loss of CaMKIIδ. Also, our single cell data suggest that there might be latent impairment of diastolic function already under basal conditions, yet this is not apparent in vivo measurements. Consequently, while therapeutic inhibition of CaMKIIδ still appears to be a promising approach, caution is warranted with respect to acidosis, where inhibition of CaMKII might be even detrimental.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Neef received funding by EU/FP6 LSHM-CT-2005-018833 EUGeneHeart. Dr. Sag received a grant from the Medical Faculty of the University of Göttingen and the DGK. Prof. El-Armouche is funded by the DFG (TP A02 SFB 1002). Prof. Maier is funded by the DFG (MA 1982/4-2 and TP A03 SFB 1002) as well as GRK 1816 RP3 and the Fondation Leducq. Dr. Backs was funded by the DFG (BA 2258/2-1), EU/FP7 (MEDIA-261409), and by the BMBF (German Ministry of Education and Research). Prof. Maier and Prof. Backs are funded by the DZHK (Deutsches Zentrum für Herz-Kreislauf-Forschung - German Centre for Cardiovascular Research). Dr. Bers was funded by NIH P01-HL80101. We acknowledge the expert technical assistance of Thomas Sowa, Timo Schulte, and Anna Förster.

Abbreviations

- CaMKII

Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II

- ECC

excitation–contraction coupling

- FDAR

frequency-dependent acceleration of relaxation

- I-1

phosphatase-1 inhibitor-1

- Iso

isoproterenol

- KO

CaMKIIδ-KO

- NCX

Na+/Ca2+-exchanger

- NT

normale Tyrode's solution

- PLB

phospholamban

- RyR

ryanodine receptor type 2 (SR Ca2+-release channel)

- SERCA

sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- TAC

transversal aortic constriction

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

Appendix A. Supplementary data: Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.02.014.

References

- 1.De Koninck P, Schulman H. Sensitivity of CaM kinase II to the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations. Science. 1998;279:227–30. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5348.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tobimatsu T, Fujisawa H. Tissue-specific expression of four types of rat calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II mRNAs. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:17907–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maier LS, Bers DM. Role of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK) in excitation–contraction coupling in the heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;73:631–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kohlhaas M, Zhang T, Seidler T, Zibrova D, Dybkova N, Steen A, et al. Increased sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium leak but unaltered contractility by acute CaMKII overexpression in isolated rabbit cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2006;98:235–44. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000200739.90811.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sag CM, Dybkova N, Neef S, Maier LS. Effects on recovery during acidosis in cardiac myocytes overexpressing CaMKII. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;43:696–709. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maier LS, Zhang T, Chen Z, DeSantiago J, Brown JH, Bers DM. Transgenic CaMKIIδC overexpression uniquely alters cardiac myocyte Ca2+ handling: reduced SR Ca2+ load and activated SR Ca2+ release. Circ Res. 2003;92:904–11. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000069685.20258.F1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neef S, Dybkova N, Sossalla S, Ort KR, Fluschnik N, Neumann K, et al. CaMKII-dependent diastolic SR Ca2+ leak and elevated diastolic Ca2+ levels in right atrial myocardium of patients with atrial fibrillation. Circ Res. 2010;106:1134–44. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.203836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sossalla S, Fluschnik N, Schotola H, Ort KR, Neef S, Schulte T, et al. Inhibition of elevated Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II improves contractility in human failing myocardium. Circ Res. 2010;107:1150–61. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.220418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner S, Dybkova N, Rasenack EC, Jacobshagen C, Fabritz L, Kirchhof P, et al. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II regulates cardiac Na+ channels. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3127–38. doi: 10.1172/JCI26620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagner S, Hacker E, Grandi E, Weber SL, Dybkova N, Sossalla S, et al. Ca/calmodulin kinase II differentially modulates potassium currents. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2:285–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.842799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirchhefer U, Schmitz W, Scholz H, Neumann J. Activity of cAMPdependent protein kinase and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase in failing and nonfailing human hearts. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;42:254–61. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00296-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Backs J, Backs T, Neef S, Kreusser MM, Lehmann LH, Patrick DM, et al. The delta isoform of CaM kinase II is required for pathological cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling after pressure overload. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2342–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813013106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toischer K, Rokita AG, Unsöld B, Zhu W, Kararigas G, Sossalla S, et al. Differential cardiac remodeling in preload versus afterload. Circulation. 2010;122:993–1003. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.943431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sag CM, Wadsack DP, Khabbazzadeh S, Abesser M, Grefe C, Neumann K, et al. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II contributes to cardiac arrhythmogenesis in heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2:664–75. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.865279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ai X, Curran JW, Shannon TR, Bers DM, Pogwizd SM. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase modulates cardiac ryanodine receptor phosphorylation and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak in heart failure. Circ Res. 2005;97:1314–22. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000194329.41863.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang T, Maier LS, Dalton ND, Miyamoto S, Ross J, Jr, Bers DM, et al. The deltaC isoform of CaMKII is activated in cardiac hypertrophy and induces dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Circ Res. 2003;92:912–9. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000069686.31472.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Oort RJ, McCauley MD, Dixit SS, Pereira L, Yang Y, Respress JL, et al. Ryanodine receptor phosphorylation by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II promotes life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias in mice with heart failure. Circulation. 2010;122:2669–79. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.982298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khoo MS, Li J, Singh MV, Yang Y, Kannankeril P, Wu Y, et al. Death, cardiac dysfunction, and arrhythmias are increased by calmodulin kinase II in calcineurin cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2006;114:1352–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.644583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chelu MG, Sarma S, Sood S, Wang S, van Oort RJ, Skapura DG, et al. Calmodulin kinase II-mediated sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak promotes atrial fibrillation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1940–51. doi: 10.1172/JCI37059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang R, Khoo MS, Wu Y, Yang Y, Grueter CE, Ni G, et al. Calmodulin kinase II inhibition protects against structural heart disease. Nat Med. 2005;11:409–17. doi: 10.1038/nm1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ling H, Zhang T, Pereira L, Means CK, Cheng H, Gu Y, et al. Requirement for Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II in the transition from pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy to heart failure in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1230–40. doi: 10.1172/JCI38022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kushnir A, Shan J, Betzenhauser MJ, Reiken S, Marks AR. Role of CaMKIIdelta phosphorylation of the cardiac ryanodine receptor in the force frequency relationship and heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:10274–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005843107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schulman H, Anderson ME. Ca/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in heart failure. Drug Discov Today Dis Mech. 2010;7:e117–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ddmec.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nomura N, Satoh H, Terada H, Matsunaga M, Watanabe H, Hayashi H. CaMKII-dependent reactivation of SR Ca2+ uptake and contractile recovery during intracellular acidosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H193–203. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00026.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mattiazzi A, Vittone L, Mundiña-Weilenmann C. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase: a key component in the contractile recovery from acidosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;73:648–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bers DM. Excitation–contraction coupling and cardiac contractile force. 2nd. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bassani RA, Mattiazzi A, Bers DM. CaMKII is responsible for activity-dependent acceleration of relaxation in rat ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:H703–12. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.2.H703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeSantiago J, Maier LS, Bers DM. Frequency-dependent acceleration of relaxation in the heart depends on CaMKII, but not phospholamban. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:975–84. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hussain M, Drago GA, Colyer J, Orchard CH. Rate-dependent abbreviation of Ca2+ transient in rat heart is independent of phospholamban phosphorylation. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H695–706. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.2.H695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valverde CA, Mundiña-Weilenmann C, Said M, Ferrero P, Vittone L, Salas M, et al. Frequency-dependent acceleration of relaxation inmammalian heart: a property not relying on phospholamban and SERCA2a phosphorylation. J Physiol. 2005;562:801–13. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.075432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huke S, Bers DM. Temporal dissociation of frequency-dependent acceleration of relaxation and protein phosphorylation by CaMKII. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:590–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bers DM, Despa S. Na+ transport in cardiac myocytes; implications for excitation contraction coupling. IUBMB Life. 2009;61:215–21. doi: 10.1002/iub.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zima AV, Bovo E, Bers DM, Blatter LA. Ca2+ spark-dependent and -independent sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak in normal and failing rabbit ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 2010;588:4743–57. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.197913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu L, Lai D, Cheng J, Lim HJ, Keskanokwong T, Backs J, et al. Alterations of L-type calcium current and cardiac function in CaMKIIδ knockout mice. Circ Res. 2010;107:398–407. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.222562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ronkainen JJ, Hänninen SL, Korhonen T, Koivumäki JT, Skoumal R, Rautio S, et al. Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II represses cardiac transcription of the L-type calcium channel 1C-subunit gene (Cacna1c) by DREAM translocation. J Physiol. 2011;589:2669–86. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.201400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carr AN, Schmidt AG, Suzuki Y, del Monte F, Sato Y, Lanner C, et al. Type 1 phosphatase, a negative regulator of cardiac function. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:4124–35. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.12.4124-4135.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.El-Armouche A, Wittköpper K, Degenhardt F, Weinberger F, Didié M, Melnychenko I, et al. Phosphatase inhibitor-1-deficient mice are protected from catecholamine-induced arrhythmias and myocardial hypertrophy. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;80:396–406. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.