Abstract

Recent progress in enzyme engineering has led to versions of human butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) that hydrolyze cocaine efficiently in plasma, reduce concentrations reaching reward neurocircuity in the brain, and weaken behavioral responses to this drug. Along with enzyme advances, increasingly avid anti-cocaine antibodies and potent anti-cocaine vaccines have also been developed. Here we review these developments and consider the potential advantages along with the risks of delivering drug-intercepting proteins via gene transfer approaches to treat cocaine addiction.

Keywords: Adeno-associated viral vector, butyrylcholinesterase, cocaine hydrolase, cocaine vaccine, gene therapy, helper-dependent viral vector, monoclonal antibody

INTRODUCTION

As drug addiction is a devastating illness with few effective remedies, new approaches are urgently needed. A novel therapy attainable with current technology can be based on agents that selectively prevent psychoactive substances from reaching brain reward centers. In principle, drug interception should be feasible to accomplish with antibodies or enzymes that trap or destroy active agents in the circulation. This review deals with these two therapeutic modalities in relation to cocaine addiction, emphasizing, 1) the multiple possibilities inherent in agents that actively eliminate drug from the body, and 2) the problems and promise of gene transfer as a means to deliver such agents. To put the relevant issues into context, we will first briefly address a straightforward immunological strategy, more fully explored by Kosten et al. in this special journal issue, and then continue with an in depth consideration of enzyme-based approaches to cocaine interception.

PART ONE. ANTIBODIES AND VACCINES

Vaccines Against Stimulant Drugs of Abuse

The fundamental goal of an “immunologic interception” would be to produce circulating anti-drug antibodies with sufficient affinity and abundance to sequester active molecules in the periphery and blunt or eliminate reward effects mediated through the central nervous system. The traditional means used to obtain high titers of anti-drug antibodies is vaccination, a strategy explored with some success in animal models of drug-seeking and in human trials with nicotine [1–3], and cocaine [1–7]. Vaccines against cocaine have been produced by linking analogs of this hapten to macromolecules such as keyhole limpet hemocyanin, cholera toxin, or tetanus toxin [8]. Such combinations allow the immune system to recognize the drug and mount a response that typically includes high affinity immunoglobulin G antibodies that bind drug so it cannot pass into the brain.

The Xenova TA-CD cocaine vaccine, an active therapeutic vaccine, was developed by Kosten and collaborators specifically for clinical use in managing addiction [9]. Norcocaine, a hapten cocaine metabolite, was conjugated to inactivated cholera toxin in a way that reliably induces therapeutic antibodies recognizing the cocaine molecule (antibodies to the carrier also arise but do not interfere). Tests showed that the elicited anti-cocaine antibodies reduced access to brain by binding the drug with moderately high affinity [10, 11]. In a clinical trial with street users, this vaccine achieved mixed results. A substantial fraction of the recipients developed inadequate antibody titers, but in the “vaccine responder” group a statistically significant 35% increase in drug-free urine samples was observed [12]. This modest outcome is actually quite encouraging since most study participants enrolled for remuneration rather than from a motive to quit. More than that, the results are respectable when viewed against standards for success in other challenging pharmacotherapeutic areas, such as cancer chemotherapy, to pick one relevant example.

A reasonable concern with therapeutic vaccines is that they could hinder drug elimination by making antibody-bound cocaine unavailable to metabolic enzymes. But recent data indicate that cocaine plasma half-life is not prolonged in the presence of anticocaine IgG with low nanomolar affinity for that agent [12, 13]. Since cocaine must dissociate from antibody before it can be metabolized, either in plasma or liver, such results seem surprising. However, a reduced overall rate constant for the degradation of protein-bound drug may be offset by the effect of sequestering drug in plasma. Thus, by preventing the natural accumulation in brain, antibody binding raises circulating drug levels and thereby enhances delivery to sites of metabolism (i.e., liver). As we have demonstrated [14], the irreversible enzymatic breakdown of cocaine (see below) can proceed effectively provided that the off-rate for dissociation from the antibody is not too slow (i.e., k-1 < 10 sec).

Any treatment relying on antibodies must come to grips with the fact that a fixed number of IgG molecules can always be saturated by a larger dose of cocaine. Thus, in testing vaccine formulations using cocaine-keyhole-limpet hemocyanin conjugate, the protective effects could be overridden [10, 15]. In contrast, another study based on a similar vaccine formulation reported that, once a minimum serum concentration of antibody was achieved, increasing cocaine doses failed to surmount the antibody [16]. It is not clear if later work has confirmed this positive result. Even so, individuals who are highly motivated to recover may well benefit from an anti-cocaine vaccine [11]. Efforts with new immunogens, adjuvants, and vaccination schedules continue to enhance the means to generate antibodies [17]. Recently Hicks and co-workers covalently linked a cocaine analog to the capsid proteins of noninfectious, disrupted adenovirus vector [8]. This protein complex is a more potent immunogen than cholera toxin, and the resulting dAd5GNC vaccine induced a higher antibody titer than previously reported. Vaccinated mice given low dose cocaine (~ 2 mg/kg, i.v.), had 40% less drug uptake into brain and their locomotor response to a large i.v. dose (50 mg/kg) was greatly reduced. Further work along the same lines indicates that vaccinated rats have reduced motivation to self-administer cocaine [18]. Therefore it may be anticipated that clinical trials with more potent vaccines will generate still more favorable outcomes.

Monoclonal Antibodies

A general limitation of clinical vaccination is the difficulty of controlling the exact nature of the resulting antibodies. In the laboratory, by comparison, a uniform population of mouse monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) can be obtained with desirable features such as exceptional binding affinity. Furthermore, mutations can be incorporated to make the amino acid sequence of mouse IgG closer to that of the human protein. Such a cocaine-binding antibody was reported and characterized several years ago [19]. Another anti-cocaine monoclonal selected for high affinity, and “humanized” in such a way for long persistence, was recently shown to affect cocaine intake after direct injection into rats trained for drug self-administration [20, 21]. Although the effect was superficially paradoxical (an increase in drug intake), the outcome can be interpreted as a sign that less cocaine was reaching the brain after each drug dose.

One ingenious approach has developed mAbs that function as pseudo-enzymes, or “abzymes” capable of degrading cocaine as a substrate. Catalytic anti-cocaine antibodies were first characterized nearly twenty years ago [22]. The design process involved hapten constructs mimicking the transition state complexes that arise during natural enzymatic hydrolysis of cocaine. The results were encouraging, although a recent analysis based on X-ray crystallography showed that catalytic antibodies act differently from cocaine-hydrolyzing enzymes, which rely on substrate binding to an active site serine residue [23]. Instead, it appears that the antibodies simply stabilize drug conformations that occur spontaneously but infrequently in aqueous solution and thereby lead to hydrolytic cleavage. The catalytic action is not trivial but it falls short of exerting a major impact on cocaine availability to the brain. Also, the most catalytically active IgG molecules have far lower affinity for cocaine than the average non-catalytic antibody (micromolar vs submicromolar), let alone those optimized for drug binding. Table 1 summarizes key properties of three catalytic antibodies reported by Cashman et al. [24] and another from the Landry group [25]. The latter afforded partial protection from cocaine toxicity in rats, which was plausibly attributed to enhanced cocaine breakdown because non-catalytic cocaine antibody was less effective [26].

Table 1.

Enzymatic Properties of Anti-Cocaine “Abzymes”

| mAb Code |

km (µM) |

Vmax (nmol/min/mg Protein) |

kcat (min−1) | Kcat/Km |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 105 ± 27 | 220 ± 75 | 38 | 3.6 × 105 |

| 5 | 35 ± 6 | 27 ± 1.9 | 4.2 | 1.2 × 105 |

| 12 | 77 ± 13 | 3.4 ± 0.4 | 0.6 | 7.8 × 103 |

| 15A10 | 220 | 2.3 | 1.0 × 104 |

Published kinetic constants for hydrolysis of cocaine benzoyl thioester by purified IgG mouse mAbs raised against protein bound cocaine analogue: antibodies 3,5, and 12 [24] and 15A10 [25]. As with true enzymes, Km is the substrate concentration at which the rate of cocaine hydrolysis is half maximal (Vmax); kcat is the number of cocaine molecules destroyed per minute by a given catalytic site; and kcat/Km, is a “figure of merit” or global measure of catalytic efficiency with the thioester (probably lower than with natural cocaine).

Gene Transfer Strategy for Antibody Delivery

The question is, how might the attractive capabilities of antidrug mAbs be incorporated into a practical therapy? Direct injections require a means of producing large amounts at reasonable cost. While protein engineering may eventually solve this problem, an alternative solution worth considering is antibody delivery via viral gene transfer.

Sustained viral transduction of anti-drug antibodies engineered or selected for optimal affinity and stability in vivo would be attractive if it generated enough IgG. In fact, using a recombinant adeno-associated viral vector, one study achieved 10 µM levels of a therapeutic VEGFR2-neutalizing mAb for periods greater than 140 days [27]. With an anticocaine antibody, such levels should provide ample binding for most circumstances. In other words, an anti-cocaine antibody that circulated at micro-molar concentrations could be expected to reduce the rate and amplitude of the drug wave reaching the brain after “recreational doses” of cocaine. If the antibody could be expressed for a year or two, that effect could help blunt addiction-related behaviors and, perhaps, reduce the risk of relapse to drug seeking. Further background to relevant gene transfer technologies will be considered in much greater detail below, but with primary focus shifting to the delivery of cocaine-metabolizing enzymes, which have shown surprising therapeutic promise.

PART TWO. ENZYME-BASED APPROACHES

Accelerated Cocaine Disposal

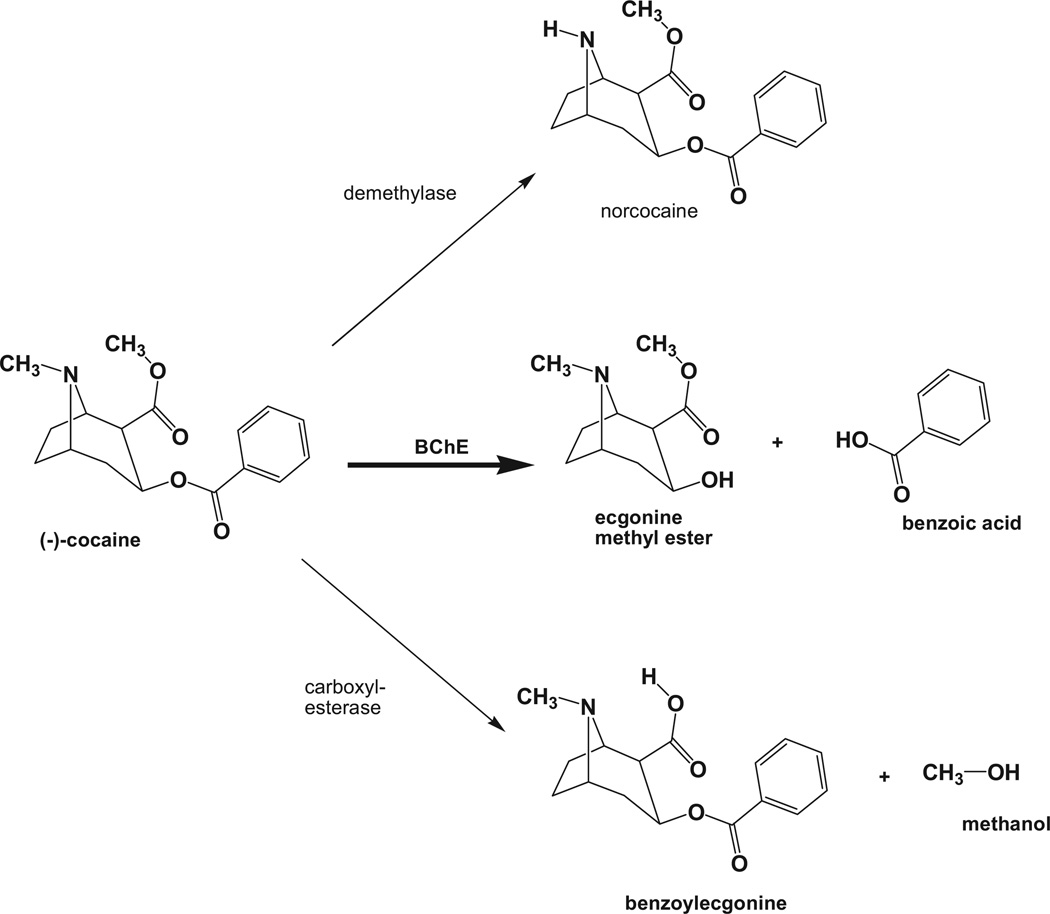

Although one would not expect enzyme treatments to eliminate cocaine craving, accumulating evidence indicates that accelerated metabolic clearance of the drug reduces its reward value to a degree that might aid motivated users in becoming and remaining abstinent. Cocaine addiction may be uniquely suited to such an approach by the nature of its metabolic pathways (Fig. 1). The hepatic cytochrome P-450 system generates a major series of cocaine metabolites, including norcocaine, benzoylecgonine, and norecgonine methyl ester [28]. Norcocaine (a class II controlled substance) retains significant rewarding properties, and its subsequent metabolism creates reactive hepatotoxic intermediates, especially in mice and rats, and probably in humans as well [29]. These reactions take place within the hepatic parenchyma, require a highly organized electron transport chain, and cannot easily be enhanced. Another metabolic enzyme is carboxylesterase, active in both liver and plasma, converting cocaine to benzoylecgonine, with reduced toxicity and stimulant properties [30, 31]. Butyrylcholinesterase (BChE), a third and most important enzyme for our purposes, converts cocaine in one step to benzoic acid and ecgonine methyl ester, which are low in toxicity and reward potential [32, 33]. This de-esterification reaction requires no co-factors and it occurs both in hepatocytes and in the plasma, which contains substantial BChE (3 to 5 mg/L) secreted by the liver [34, 35]. These facts assume increasing importance in light of recent protein engineering advances that have selectively enhanced BChE’s catalytic efficiency for cocaine hydrolysis to a dramatic extent, as will be discussed.

Fig. 1.

Pathways for cocaine metabolism in liver. Three main enzyme systems play a role in converting to cocaine to metabolites that are less active and more readily eliminated from the body. The hepatic cytochrome P450 system catalyzes N-demethylation to yield the intermediary substance nor-cocaine, which largely retains biological and psychoactivity and is hepatotoxic. Liver carboxylesterase yields benzoylecgonine, which has substantially less biologic activity than cocaine. Butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) yields ecgonine methyl ester and benzoic acid, which are largely devoid of activity.

From a physiological perspective, BChE represents a “back-up pathway” to complement acetylcholinesterase in regulating synaptic acetylcholine levels, but the enzyme also appears to have evolved as a protection against toxic plant-derived esters [36]. Cocaine is such an ester, and it is susceptible to BChE as just noted. Gorelick, one of the early investigators to recognize the significance of this reaction, initially proposed that injection of native human BChE might serve as a rescue for cocaine overdose [37]. Unfortunately, since BChE hydrolyzes cocaine only 0.1% as readily as acetylcholine, huge quantities of enzyme protein would be required for a meaningful effect. Nonetheless, Woods and collaborators, among others [38] found that sizeable doses of native human BChE could antagonize cocaine-induced locomotor activity in mice. Interest in enzyme treatments for cocaine toxicity rose after a thousand-fold more efficient cocaine esterase (“CocE”) was discovered in bacteria that utilize cocaine as a carbon source [25, 39, 40]. When given to rats this enzyme caused a 10-fold rightward shift in the dose-response curve for cocaine toxicity and it protected against lethal cocaine-induced seizures [41]. After modification for greater stability in vivo, CocE provided even better protection against cocaine toxicity [42]. It also reduced cocaine self-administration in rats and weakened cocaine’s cardiovascular effects in rhesus monkeys [43]. Clinical trials with CocE are soon expected or are already underway. But no matter how effectively the bacterial protein may act in the acute setting, there is a risk that it will prove too antigenic for long-term treatment of addiction. Meanwhile, recent computationally directed mutations of the catalytic site in human BChE have vastly increased its activity toward cocaine. The most efficient BChE mutants now have catalytic efficiencies closely comparable to bacterial CocE while being almost certainly less immunogenic, or possibly not immunogenic at all.

Details of the BChE mutagenesis are beyond the scope of this article but an outline may be of interest. Insights from docking studies “in silico” played a significant role in the process of “directed evolution”. Centers participating intensively in developing a BChE-based cocaine hydrolase included the research groups of Lockridge and collaborators at U. Nebraska, Zhan and others at U. Kentucky, and our group at the Mayo Clinic [44–50]. Early on, we compared the docking orientation of natural (−)-cocaine with those of a biologically inactive (+)-stereoisomer that hydrolyzed approximately 2000-fold more readily [45, 46]. These comparisons revealed that natural cocaine preferentially binds to the enzyme with its ester carbon atom located at some distance from the active-site serine hydroxyl, a conformation that is suboptimal for catalysis. Equally important, it appeared that (−)-cocaine should be poorer than (+)-cocaine in rotating from this “ground state” to a better orientation for hydrolysis. We introduced two mutations predicted to alleviate this difficulty in the active site region (A328W/Y332A). The result was a 50-fold increase in kcat (cocaine molecules hydrolyzed per minute per enzyme molecule). Zhan et al. soon achieved an equally large further jump in catalytic power after conducting a thermodynamic analysis and designing mutations to reduce the free energy of the transition state complex [47, 48, 50].

The rational mutations of BChE ultimately led to quadruple and quintuple mutants with catalytic efficiencies up to 1700-fold higher than natural human BChE, and far beyond the range of any known catalytic antibody. A comparison of Tables 1 and 2 demonstrates the advantage of the most efficient enzyme (CocH2) over the best reported antibody. Specifically, the enzyme’s catalytic rate constant for cocaine is 400 times higher than the mAb (implying greater effectiveness against large drug doses) while its Km is 35 times lower (implying better performance with typical user doses). Thus overall efficiency is 14,000 times higher. Further engineering of catalytic antibodies is most unlikely to achieve these performance levels.

Table 2.

Catalytic Constants for Cocaine Breakdown by Wild-Type BChE and Engineered BChE-Based Cocaine Hydrolases

| BChE | Mutations | Kcat | KM (µM) | kcat/ KM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | None | 4 ± 0.1 | 3 ± 0.2 | 1.3 × 106 |

| Double mutant | A328W/Y332A | 154 | 18 | 8.6 × 106 |

| AME-CocH | F227A/S287G/A328W/Y332M | 620 | 20 | 3.1 × 107 |

| CocH1 | A199S/S287G/A328W/Y332G | 2700 ± 190 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 1.3 × 109 |

| CocH2 | A199S/F227A/S287G/A328W/E441D | 1730 | 1 | 1.7 × 109 |

| CocH3 | A199S/F227A/S287G/A328W/Y332G/E441D | 4430 | 3.5 | 1.3 × 109 |

Compiled from Sun et al., 2002; Brimijoin et al., 2008; Pan et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2010, and Xue et al., 2011a.

Enzyme Effects on Cocaine Responses

Initial animal studies with cocaine hydrolase in our laboratory used our double-mutant BChE [45, 46, 51]. In rats we found that pre-administered hydrolase (3 mg/kg, i.v.) reduced pressor responses to cocaine (7 mg/kg i.v.), and the same enzyme reversed those responses when delivered after the fact [52]. We then turned to the more efficient enzyme, CocH1, in a version fused to human serum albumin with the intent of prolonging its plasma half-life [53]. This enzyme not only protected rats against cocaine toxicity, but aborted lethal seizures from a massive overdose (100 mg/kg, i.p.), even when injected after major convulsions had already begun [54].

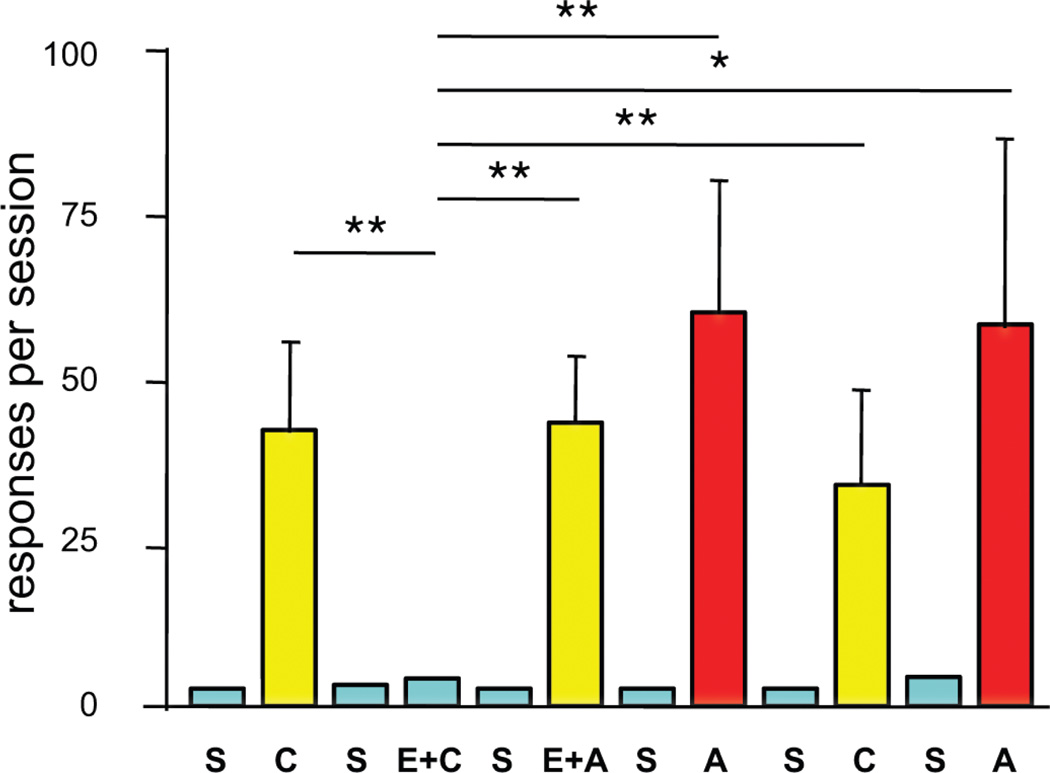

CocH displayed equally striking effects on reward-related behavior. For tests on drug seeking, rats were trained to self-administer cocaine until they maintained stable rates of lever-pressing on a progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement. This behavior was then deliberately extinguished by inactivating the lever associated with reward. After two weeks of enforced abstinence, the rats entered a version of the classic “drug-primed reinstatement” paradigm, in which non-contingent delivery of the previously self-administered drug reliably evokes drug-seeking behavior. In this case, rats were removed from its operant chamber to receive either saline or CocH, 2 mg/kg, i.v. A priming injection of saline or cocaine followed 2 hr later, and the animals returned to their chamber. In these experiments (Fig. 2) CocH prevented the increased responding normally evoked by cocaine, and clearly evident in the saline-pretreated rats (an average of ~40 presses on the formerly cocaine-paired lever) [54]. This effect was selective (i.e., specific to cocaine), in that amphetamine, a BChE-resistant psychostimulant with similar effects on synaptic monoamines, induced reinstatement to drug seeking equally well in both treatment groups.

Fig. 2.

Selective blockade of cocaine-primed reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior. Fifteen rats that previously self-administered cocaine and then extinguished responding when drug was replaced by saline were subsequently given i.v. priming injections of saline (S), cocaine (C, 10 mg/kg) or amphetamine (A, 2 mg/kg i.v.), immediately before each of 12 daily, 2-h sessions. On days 4 and 6 they received CocH (E, 2 mg/kg), 2 hr before the drug priming injection. Shown are means and SEM of total responses on the previously active lever. Horizontal brackets indicate statistical comparisons (*p< 0.05, ** p< 0.01). [54].

Enzyme pretreatment also affected responding for drug by rats entered on a “dose escalation paradigm” that involved lengthening the drug-reward sessions from a standard 2-hr duration to a 6-hr duration [55]. Over a few weeks of “long-access”, rats typically escalate their daily lever pressing and drug intake, a phenomenon deemed relevant to intensified craving and binge drug-taking in human users [56]. Rats given CocH shortly before each of multiple successive sessions initially showed more lever-pressing than controls. In subsequent sessions, however, responding by enzyme-treated rats returned to or fell below control levels. Notably, upon reverting to the 2-hr paradigm after two weeks of long-access testing, control rats maintained elevated responding for many subsequent sessions, but enzyme-treated rats showed no such aftereffect. In other words, cocaine hydrolase prevented the persistent behavioral alterations, and presumably the underlying neuroplasticity, that ordinarily follow a lengthy period of enhanced drug access.

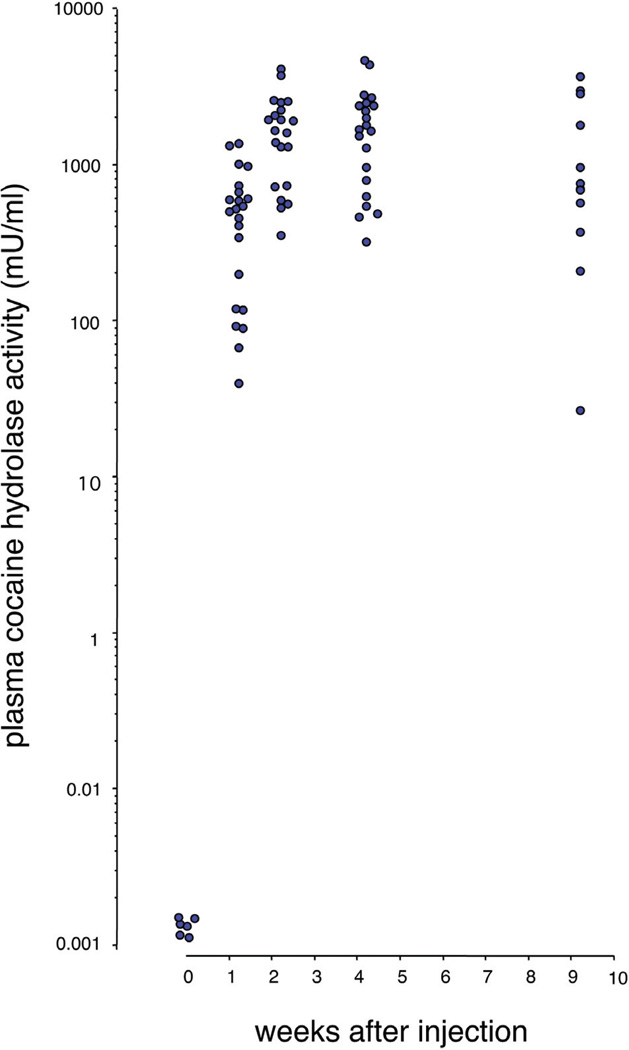

Viral Gene Transfer for Long-Term Delivery

Positive behavioral results with enzyme-treated rats suggested that therapies based on cocaine hydrolase might be effective treatments for cocaine abuse if comparable levels of enzyme could be sustained in human beings. The effects of direct enzyme injection last only a few hours in rats, limited by the protein's half-life (8 hr for the tested mutant versus 30 hr for native rat BChE). It may be possible to extend the duration of enzyme treatments with various protein modifications that increase half-life, such as complex formation with polyethylene glycol [57], or by developing slow-release depot preparations. However, with a view towards truly long-term therapy, and avoiding the huge costs associated with multiple treatments requiring gram quantities of pure protein, our laboratory initiated the exploration of cocaine hydrolase gene transfer. Our early experiments [58] involved simple E-1 deleted adenoviral vectors with mutant BChE cDNA sequences driven by a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter [59]. This type of construct transduces substantial levels of various transgenes in liver, but it also arouses immune responses that limit the duration of expression. In this sense our results were in line with previous data on other transgenes, but they served to demonstrate basic feasibility of hydrolase transfer. At peak expression, 5 to 7 days after treatment with 2.2 × 109 plaque forming units (pfu) of vector encoding a double mutant BChE (A328W, Y332A), cocaine hydrolase activity in rat plasma was 3000 times above its initial level [58]. In subsequent experiments, replacing the double mutant with the more efficient AME mutant [53, 60] and using higher vector doses (1010 pfu per rat), plasma cocaine hydrolase activity rose by a remarkable 50,000-fold (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Adenoviral transduction of BChE-based cocaine hydrolase in rats. Plasma samples collected at multiple times after tail vein injection of Ad5-CMV-AME359, 10×1011 viral particles. Each point on the logarithmic scale represents mean cocaine hydrolase activity (mU/ml) in duplicate assays from each rat. Note the million-fold range.

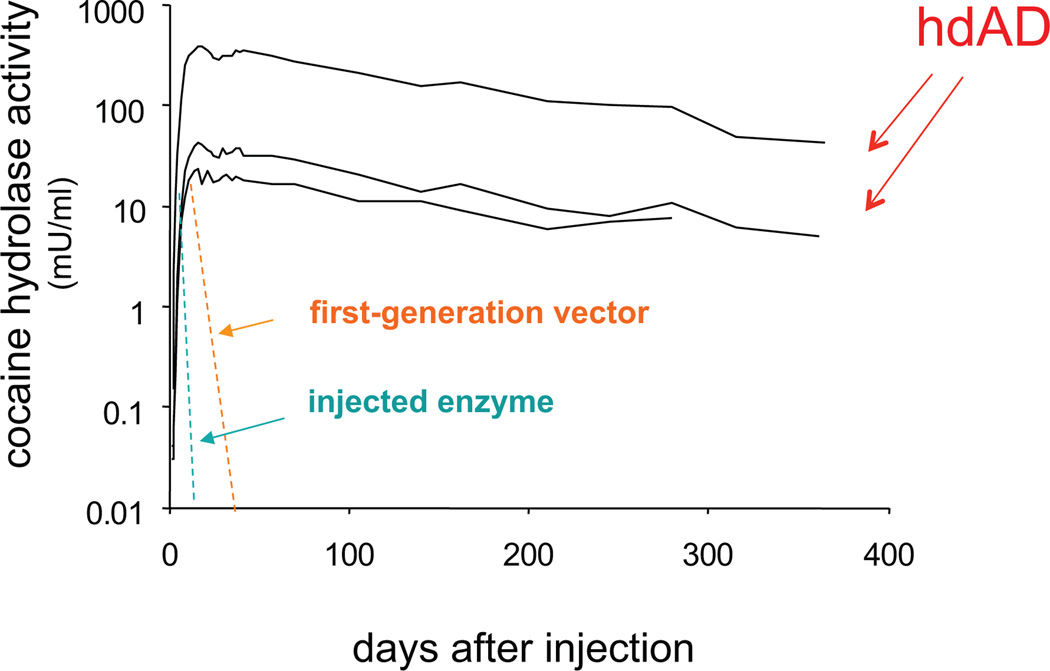

Our further studies on AME transduction have utilized a helper-dependent adenoviral vector (hdAD) incorporating a liver-specific human ApoE promoter. This advanced vector lacks DNA for all viral proteins and is less prone to provoke immunological reactions [61]. We found that transduction of AME cocaine hydrolase was sustained at high levels for extremely long periods of time, up to one year after a single vector injection (Fig. 4). Peak enzyme activity, reached approximately two weeks after vector injection, was in the range of 300 mU/ml, corresponding to an enzyme concentration of 40 µg/mL, or roughly 8 times the typical BChE levels for human plasma. High level expression of the enzyme persisted for several months. Even at one year, the longest time point tested so far, cocaine hydrolase activity in the treated rats was still about 20% of initial peak levels [62]. To establish the in vivo turnover of transduced enzyme 9 months after vector delivery, we administered one injection of iso-OMPA (3 mg/kg, i.p.), an organophosphate that can irreversibly and selectively inhibit BChE by 98–99% with less than 5% inactivation of AChE [63]. By measuring the quasi-exponential recovery of cocaine hydrolase activity in these animals, we deduced a plasma half-life of 60 hr for the expressed transgene [62]. That value was actually longer than the half-life estimated for native BChE in rats that received no vector. Therefore the expressed enzyme remained very stable, even after 9 months of transduction, when trace amounts of anti-BChE antibody could be detected in some plasma samples.

Fig. 4.

Long-term transduction of cocaine hydrolase in rats. Hydrolase transduction time course and turnover rates. Cocaine hydrolase activity (mU/ml) in rat plasma drawn at indicated times after tail vein injection of CMV-AV-CocE (dashed line, mean of six rats) or ApoE-hdAV-CocE (solid lines with data symbols, individual rats). Enzyme activity expressed in mU (nmol product/hr) per ml of plasma [62].

Gene Transfer and Behavior

Having demonstrated long term and high level expression of cocaine hydrolase we faced the crucial question regarding a proposed therapeutic gene transfer: would such a procedure suppress drug seeking-behavior, and would the suppression continue long enough to be useful? Recent tests in rats treated with hdAD vector encoding the AME enzyme and ApoE promoter have provided a strongly positive answer (Anker et al., 2012, in press). Animals first established stable lever pressing for cocaine reward on a progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement. They were then removed from the operant conditioning chambers and given hydrolase vector through the tail vein (1010 viral particles per rat). After two weeks of enforced abstinence they returned to their chambers, with normal drug-paired cues but an inactivated reinforcement lever. The reinstatement procedure consisted of 8 days in which saline or cocaine (5, 10, 15 mg/kg) was given at the beginning of experimental sessions. Once per week for the next 4 weeks the rats received i.p. injections of saline or cocaine (20 mg/kg) on successive days. Control animals (no vector or “empty vector” treatment) responded to the cocaine priming injection with robust activity on the formerly drug-paired lever but responded very little to the saline injections. In comparison, rats given active CocH-transducing vector showed the same low level of responding to cocaine as to saline. Both groups responded equally well to the non-hydrolyzed priming agent, amphetamine. In other words, the hydrolase gene transfer selectively blocked drug-primed reinstatement in the same fashion as did injections of purified enzyme protein. Most important, the therapeutic effect of a single vector treatment lasted for the entire six-months of observation. Such findings raise the possibility that a similar approach in humans could help recovering addicts to bridge the dangerous initial year or two during which relapse into full-blown addiction is frequently triggered by a single encounter with the drug.

Closer analysis of the above results revealed the surprising fact that several vector-treated rats continued with minimal responding to cocaine priming injections even after their plasma cocaine hydrolase activity had dropped substantially. This phenomenon is being explored further because of its implications for interoceptive drug cues, which are gathering attention for their importance in immediate drug reward [64]. It may turn out that repeated cocaine injections when hydrolase activity is high still elicit normal interoceptive cues but fail to generate a dopamine surge in central reward nuclei. If so, active dissociation of cue and reward might occur and further weaken tendencies for drug exposure to provoke renewed drug-seeking behavior.

Overall, present information encourages efforts to prepare the technology of delivering engineered BChE cocaine hydrolases for clinical application by viral gene transfer. The remainder of this chapter will consider additional issues that must be addressed on the road to that ultimate goal. These issues include general risk / benefit tradeoffs, especially the likelihood of adverse responses to vector or transgene. We will also discuss tissue preferences for transduction of a cocaine-metabolizing enzyme, desirable and necessary levels of expression, and the optimal duration that will serve the therapeutic aim.

General Risk/Benefit Considerations

From an ethical perspective risk-prone therapies are appropriate only for conditions that are either life threatening (e.g., incurable cancer) or impossible to tolerate (e.g., severe and intractable pain). Drug-addiction probably fails to fully satisfy either criterion even though it is deeply harmful to individuals and their families and carries risks of death or major illness. Therefore, a gene therapy for addiction must meet high standards of safety and efficacy. In our attempts to select the optimal vector and therapeutic protein, we are focused on maximizing the therapeutic index by identifying constructs that drive cocaine metabolism to the highest possible final level with a given dose of vector and a given load of transgene.

Selecting for Optimal Enzyme Properties

The best enzyme for cocaine interception would exhibit not only high maximal velocity but also a substrate affinity that permits rapid catalysis down through the lower range of drug concentrations with physiologic or behavioral effects. As outlined above, it appears that recent mutational efforts with human BChE have neared that goal or may already have reached it, measured by the yardstick of catalytic behavior. However, other desirable properties relevant to a gene therapy for drug abuse are efficiency of transcription and translation, and stability of the expressed protein in vivo. Even if the most catalytically effective cocaine hydrolases have already been identified, it remains uncertain whether all versions will transduce equally well or whether they will be equally durable after secretion into plasma. As this review was being written, tests of the most promising new BChE mutants in different vector platforms were underway. Therefore it should soon be possible to select the optimal entity with reference to actual enzyme activity generated and maintained in vivo.

Confirming Safety of Cocaine Hydrolase

One potential safety concern is whether the transgene will be targeted by the host immune system. In the case of BChE-based hydrolases in human recipients one can be cautiously optimistic that such a problem will not arise, or will be minimal. As a starting point, we assume that subjects exposed to native human BChE would show no immune response at all, except for the very rare individuals who lack this enzyme completely [65, 66]. We also hypothesize that the altered residues that enhance cocaine hydrolase activity in the re-engineered enzymes will be poorly antigenic, because they are concealed deep within the catalytic gorge. The issue of potential immune responses is important, however, and needs thorough study. In this regard, it is encouraging that immune responses to human cocaine hydrolase have proved surprisingly weak in rats. A few rats transducing this enzyme after receiving hdAD vector lost transgene activity after two months, but most continued to express cocaine hydrolase activity for up to six months with undetectable or very modest levels of anti-BChE antibodies [62]. We speculate that this subdued immune response reflects BChE’s heavy glycosylation, up to 25% of total mass [67–70]. This carbohydrate coating, if generated in the rat, may partly mask foreign amino-acid epitopes from the host immune system. However, mice appear to mount a much stronger immune reaction to endogenously transduced human BChE. They often show detectable anti-enzyme antibodies two weeks after viral transduction of CocH, and they tend to lose cocaine hydrolase activity within two months (Gao and Brimijoin, unpublished data).

We are continuing mouse experiments with the goal of determining whether antigenicity is likely to pose problems for gene transfer of mutated BChE cocaine hydrolases in human beings. The ultimate answer to that question must come from clinical trials, but it seems worthwhile to ask whether viral transduction of a murine BChE with comparable mutations will provoke immune responses and rapid clearance of the enzyme within the same species (i.e., in a conspecific host). The experiment is possible because native mouse and human BChE have identical amino acid residues at all five of the sites mutated for the most effective cocaine hydrolase tested to date in our hands. Relevant experiments are ongoing, but our preliminary data show that the mutated mouse BChE persists at stable levels in plasma for at least four months after transduction by adeno-associated virus vector type 2/8 (AAV-2/8), with no detectable antibody response. Thus it seems that mutating these sites in a conspecific enzyme does not confer immunogenicity, and we anticipate that this outcome will hold true in the human case.

Another more theoretical risk also deserves some attention. As noted previously, BChE is generally viewed as playing an auxiliary role in cholinergic neurotransmission by virtue of its capacity to hydrolyze acetylcholine. In fact BChE is about 20% as efficient in hydrolyzing acetylcholine as is acetylcholinesterase (AChE), the major enzyme responsible for clearing transmitter from the neuromuscular junction and other cholinergic synapses [71, 72]. Thus the question arises, would elevated levels of plasma BChE impair motor activity or other processes that depend critically on acetylcholine? In fact, systemic BChE gene transfer is unlikely to disturb cholinergic function by reducing synaptic acetylcholine concentration in the periphery or the central nervous system. In the first place, all tested BChE-based hydrolases with enhanced activity towards cocaine show reduced activity against acetylcholine as a substrate. This means that, if gene-transfer of the highly efficient CocH2 (see Table 2) resulted in twice normal plasma BChE levels, one could expect a nearly 2000-fold increase in hydrolysis of circulating cocaine hydrolysis but less than a 2-fold increase in hydrolysis of plasma acetylcholine. The effect on synaptic acetylcholine should be smaller still, since the transgene product is virtually confined to liver and plasma [58] while AChE is densely concentrated at nerve endings [71]. At such physiologically relevant sites this more efficient enzyme reaches levels of activity many hundred-fold above those achievable by transduced BChE diffusing in from the circulation.

The picture just described is supported by the outcome of US Defense Department studies with animals including non-human primates, and also with human subjects who received large quantities of BChE to evaluate its safety and efficacy in protecting against chemical warfare agents. Saxena and co-workers have shown that mice and guinea pigs tolerate doses of human BChE that raised plasma enzyme levels 50 to 100 fold with no clinical evidence of dysfunction or tissue pathology [73, 74]. In a recent study with similar goals [75], human plasma-derived BChE purified on an industrial scale was administered to rats and guinea pigs for detailed preclinical testing. Outcomes included general behavioral evaluation, as well as measures of blood pressure, thrombogenic potential, and pulmonary inflation pressure. Extensive postmortem pathology was also performed. Very large doses were given (up to 500 mg/kg i.v. and 100 mg/kg i.m.). If we assume that the injected BChE distributed into total extracellular fluid (~ 1/3 of body volume), its plasma concentration after the maximal tested dose would be close to 1500 mg/L, or 300 to 500 times higher than normal for an adult human. Under these circumstances it is remarkable that no negative effects of any type were noted, beyond a mild drop of blood pressure in two rats given a sub-maximal dose (i.e., a non dose-related finding). Finally, unpublished results of human studies (D. Cerasoli, USAMRICD, personal communication) have indicated no adverse effects or physiological alterations even after large BChE doses (nearly one gram per subject), which raised plasma cholinesterase levels at least 12-fold. Overall these results strongly support the conclusion that exogenously administered BChE is physiologically inert.

Choosing Vector Platform and Promoter Elements

Another issue for hydrolase gene transfer is the selection of vector platform, which, together with the choice of promoter and enhancer sequences, determines the tissue locus of enzyme transduction, the level of transduced enzyme, and the duration of transduction. At present there appear to be two viable candidates for vector of choice in regard to cocaine hydrolase gene transfer: helper dependent adenovirus (hdAD), serotype 5 [76–78], and AAV serotype 2/8 [79]. These two systems lack coding DNA for any of the proteins needed to produce a viral coat or replicate the viral genome: hdAD by virtue of molecular engineering, and AAV as a naturally helper-dependent parvovirus [80]. Both of these replication-incompetent vectors enter target cells (with these particular serotypes, primarily hepatocytes), by binding to unique surface proteins and inserting DNA that becomes incorporated as stable episomal elements within the nucleus (not integrating with the host chromosome).

Most of our current work is relying on hdAD constructs that were originally developed by Parks, Ng, and others [61, 81, 82]. These vectors represent a great advance over first generation AD vectors with simple E1-region deletions that serve to prevent replication (rendering the agent harmless for infection) but also allow robust immunologic detection that sharply curtails effective gene transduction. Soon after the hdAD constructs were introduced their impressive ability to sustain long-term transduction became evident. Using these vectors it was possible to obtain high circulating levels of human alpha antitrypsin in baboons for over one year [83] and lifetime expression (~2.5 year) of the ApoE gene in genetically deficient mice [84]. Our own experience with yearlong transduction of cocaine hydrolase is in good agreement with these earlier findings.

Despite the encouraging results to date, however, there are serious challenges to the clinical application of hdAD vectors. The greatest of these is a demonstrated risk of tissue toxicity, particularly in liver, reflecting host responses to the transiently exposed capsid proteins of the delivered vector. These proteins, required for initial cell penetration and targeting the liver, evoke a rapid, dose-related, and potentially severe attack from the innate host immune system [85, 86]. Hepatocytes are particularly vulnerable during the process of vector uptake. This reaction is equivalent to the one provoked by early generation E-1 deleted AD vectors, and suspected as the primary cause of the fatal outcome in the very first clinical trial of AD gene therapy [87]. Since the immune response is transient and limited to the period during which viral capsid proteins remain in situ, the problem may be susceptible to mitigation by temporary immune suppression. Although multiple factors must come into play, it has proved possible to reduce the innate toxicity of hdAD in mice by pretreatment with the anti-inflammatory steroid, dexamethasone [88]. In this regard, however, our preliminary histopathology studies show that hdAD transduction of CocH is not accompanied by liver damage in rats or mice, as evidenced by histopathology or measures of alanine transaminase activity in plasma. Furthermore, the vector treatment offers significant protection against cocaine-induced hepatoxicity. In other words, liver samples of rats and mice transduced with CocH by hdAD treatment and later exposed to large doses of cocaine contrast with those from unprotected animals in showing greatly reduced evidence of centrilobular necrosis and other pathologic signs. Nonetheless, concerns regarding clinical use of hdAD vectors dictate that alternatives to hdAD vectors should also be thoroughly investigated.

The principal alternative to hdAD in a gene therapy for cocaine abuse is AAV. AAV vectors have seen limited applications until recently, because of their tight limits on cloning capacity. Practically speaking, the length of DNA sequences that can be introduced as transgene payload is less than 3.5 kB [89]. A second problem is that infections with wild type AAV are prevalent in the human population and the resulting immunity prevents effective use of vectors with the same serotype [85]. On the positive side, wild AAV has never been associated with human illness [90], and AAV vectors have proved relatively benign in animal studies [91, 92]. As a result, and despite the drawbacks just noted, over a dozen clinical trials have been completed with AAV vectors, focusing on multiple diseases such as alpha 1 antitrypsin deficiency [93], hemophilia B [94], cystic fibrosis [95], Parkinson’s disease [96], heart failure [97], and rheumatoid arthritis [98], and more studies are ongoing or pending. Rodent studies on transducing cocaine hydrolase with AAV-2/8 vector and a human ApoE promoter are in the early stages in our laboratory. To date, these constructs have been yielding less than half as much plasma cocaine hydrolase activity as the equivalent hdAD construct. This figure may improve as we test the effects of alternate intronic sequences and self-complementary design to avoid problems with second strand DNA synthesis [99]. If so, the stage will be set for a fair comparison between two promising vector platforms, in which the primary standard will be delivery of the greatest drug metabolizing power with the least risk of adverse effect.

Locus of Expression

The locus of transgene expression is driven by two key factors. First is the tissue tropism of the vector itself, a feature largely determined by the general nature of the parent virus and particularly by the vector serotype [100]. Second is the promoter sequence incorporated to drive transgene expression, which can be selected to favor a range of specific cell types [101, 102]. To impact a behavioral problem like drug addiction, there are two logical sites for expression. One is the central nervous system itself, the other is a peripheral site involved in filtering the blood or suited for releasing transgene into plasma where it can intercept or destroy drug before it reaches central nervous system targets. Among the vector candidates for such therapies, none of them are likely to drive gene expression in the brain unless administered intracerebrally, because viral particles do not ordinarily have access to this central compartment. Stereotaxic delivery can bypass that problem and is properly considered for treatment of fatal illnesses like malignant glioblastoma or progressive and irreversible conditions like Parkinson's disease, but such measures appear radically inappropriate for a behavioral disorder. Fortunately, our rat data indicate that transduction of cocaine hydrolase after i.v. injection is at least as effective as transduction in neostriatal reward nuclei after stereotaxic injection. Thus, vector delivered systemically before a week-long series of twice daily cocaine exposures prevented induction of delta-FosB throughout the caudate nucleus, whereas intracerebral delivery protected only those neurons close to the injection site [62].

For systemic delivery there are relatively few good choices of target. Muscle is an accessible, large-mass tissue with the advantage that any minor vector-induced dysfunction is unlikely to pose extreme health risks. This tissue site may in fact be preferred for attempts to replace a deficient protein that is not required in large quantities (e.g., rare clotting factors). However, muscle is a poor choice if there is a need for high expression, as to intercept large drug doses entering the circulation. That challenge points us toward the liver, a tissue that evolved specifically for eliminating or neutralizing toxic xenobiotics. The liver receives a large blood flow, about 500 ml/m2 per minute [103], which represents about 20% of the total cardiac output. Therefore, within a few circulation times it has the opportunity to interact with nearly all blood-borne molecules. The liver is also the natural source for BChE, which, after appropriate protein engineering, has shown such promise as a means of degrading cocaine en route to brain. Thus, liver-transduced cocaine hydrolase is well placed for efficiency in cocaine metabolism. Furthermore, the liver secretes much of its newly synthesized BChE into the circulation, where it remains with a half-life of many days, able to destroy cocaine on contact. Thus transduced liver tissue offers double advantages of local and distributed action to eliminate this drug.

Duration of Expression

It should not be necessary to provide permanent gene transduction in order to treat cocaine addiction effectively. However, at least six months of effective drug interception is probably essential, and a period of two or three years may be desirable to achieve full cessation of drug intake and to avoid relapse. This time frame would not require a vector that incorporates permanently into genomic DNA (with attendant risk of disrupting oncogenes). It can be managed with the helper dependent “gutted” adenoviral vector, or adeno-associated viral vectors considered above. The latter two vectors show long persistence even though they do not propagate from cell to cell. However they are usually lost during mitosis because they lack elements needed to replicate the viral DNA and segregate it to daughter cells [104]. Fortunately for present purposes, although liver cells are not immortal, they turn over slowly. Even in rats and mice, whose hepatocytes exhibit a half-life of one year or less [105], effective levels of transgene remain for many months after initial vector treatment as already noted. Life spans for hepatocytes in adult human liver are estimated at between 300 and 500 days [106]. Therefore, if cell division or cell death is the primary mechanism for loss of vector DNA, one could expect a therapeutic window on the order of one or two years after a successful hepatic transduction.

CONCLUSION

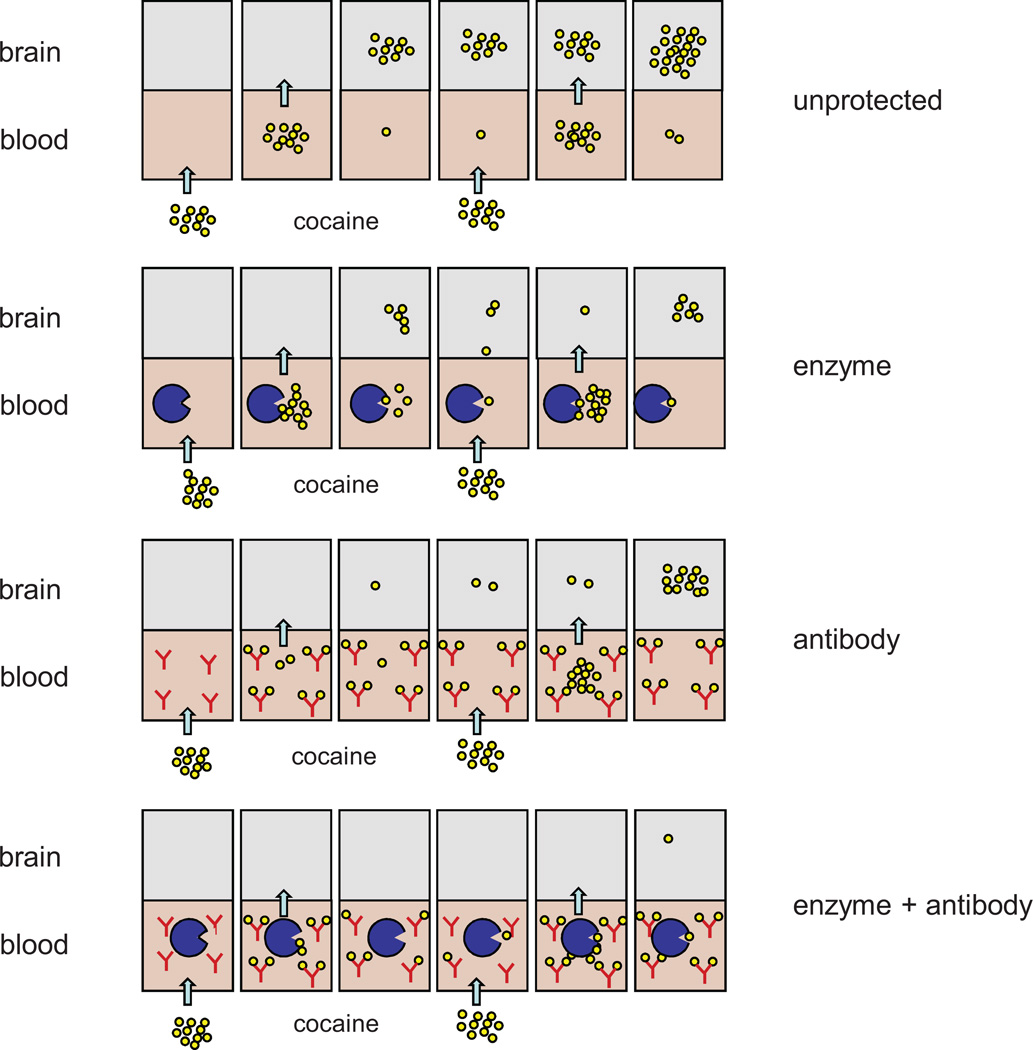

There is a real prospect of developing therapies for cocaine addiction based upon the idea of “pharmacologic interception”. The two major approaches that show real promise rely on vaccination to generate anti-cocaine antibodies or on gene transfer of cocaine hydrolase enzyme derived by mutation of native human BChE. The barriers to deployment of cocaine vaccines are lower than those facing a novel gene therapy. And with more potent vaccines based on advanced carrier-hapten constructs, vaccine effectiveness in reducing drug intake is likely to improve. On the other hand, we consider that long-term delivery of a physiologically benign cocaine hydrolase offers tremendous potential, particularly because such a therapeutic cannot easily be overwhelmed even by repeated large doses of drug. It needs to be stressed that these two approaches are not mutually exclusive. Elsewhere we have argued that they are instead complementary [14]. Our fundamental concept is that abundant antibodies can bind a low dose of cocaine but may be saturated by large or repeated doses, whereas a hydrolase may be outnumbered by cocaine molecules but will destroy them all, given time. Together these two agents should constitute a self-regenerating system, in which antibody absorbs an initial wave of drug while enzyme destroys the free molecules and then unloads the immunoglobulin-bound portion, resetting the system to its initial state (Fig. 5). This concept is the subject of ongoing experiments, and it is too early to tell whether it applies broadly to the real-world phenomenon of cocaine abuse. In current tests on rats and mice, however, combinations of enzyme and antibody are proving noticeably more effective than either agent alone in reducing cocaine-induced locomotor activity and hepatotoxicity in rats and mice (Gao, Carroll and Anker, unpublished data). If similar results are obtained in models of cocaine-seeking behavior, and especially if the effects are synergistic, it will be proper to consider human applications. It seems reasonable to expect that modest levels of transduced cocaine hydrolase, safely achievable with low doses of vector, would enhance the effect of therapeutic vaccines to the point at which most subjects can achieve and maintain drug-free status. It is also conceivable that an optimized gene therapy will safely deliver cocaine hydrolase at a high level that by itself could provide extended protection during the period when appetitive drug-associated memories and cravings are subsiding.

Fig. 5.

Model for cooperative cocaine interception by anti-cocaine antibodies and cocaine hydrolase. Schematic illustration of cocaine uptake into brain after i.v. administration to subjects under four different conditions: “unprotected” (no pretreatment), “enzyme” (provided with an efficient cocaine hydrolase), “antibody” (given high affinity anti-cocaine IgG), and “enzyme + antibody” (given both pretreatments). Panels read from left to right as a time sequence. In this model an unprotected subject accumulates cocaine in brain after each repeated injection. An enzyme treated subject does not, so long as hydrolysis is nearly complete before the second injection. An antibody treated subject may do better than an enzyme treated subject at first, but a second injection can overwhelm the protection. Dual treatment is most effective [53].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None of the author’s work on which this article is based could have been accomplished without the able collaboration and assistance of many investigators at the Mayo Clinic (Y. Gao, Y.P. Pang, S. Russell, and H. Sun), the University of Minnesota (M.E. Carroll, J. Anker), the University of Ottawa (R. Parks), Baylor University (T. Kosten, F. Orson, B. Kinsey), and CoGenesys, Inc. (D. LaFleur). Financial support for the author’s recent research was supplied by grants from NIDA (R01DA23979 & DI DA31340). Earlier work on the same subject was supported by a grant from the Minnesota Partnership for Medical Genomics and Biotechnology and a small grant from CoGenesys, Inc.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AAV

Adeno-associated virus

- BChE

Butyrylcholinesterase

- CocH

Cocaine hydrolase

- CMV

Cytomegalovirus

- hdAD

Helper-dependent adenovirus

- mAb

Monoclonal antibody

Footnotes

The author has no ongoing conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hatsukami DK, Jorenby DE, Gonzales D, Rigotti NA, Glover ED, Oncken CA, Tashkin DP, Reus VI, Akhavain RC, Fahim RE, Kessler PD, Niknian M, Kalnik MW, Rennard SI. Immunogenicity and smoking-cessation outcomes for a novel nicotine immunotherapeutic. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011;89:392–399. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hatsukami DK, Rennard S, Jorenby D, Fiore M, Koopmeiners J, de Vos A, Horwith G, Pentel PR. Safety and immunogenicity of a nicotine conjugate vaccine in current smokers. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005;78:456–467. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pentel PR, Malin DH, Ennifar S, Hieda Y, Keyler DE, Lake JR, Milstein JR, Basham LE, Coy RT, Moon JW, Naso R, Fattom A. A nicotine conjugate vaccine reduces nicotine distribution to and brain attenuates its behavioral cardiovascular effects in rats Biochem. Pharmacol. Behav. 2000;65:191–198. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00206-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kosten T, Owens SM. Immunotherapy for the treatment of drug abuse. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005;108:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kosten TR, Rosen M, Bond J, Settles M, Roberts JS, Shields J, Jack L, Fox B. Human therapeutic cocaine vaccine, safety and immunogenicity. Vaccine. 2002;20:1196–1204. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(01)00425-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orson FM, Kinsey BM, Singh RA, Wu Y, Kosten TR. Vaccines for cocaine abuse. Hum. Vaccin. 2009:5. doi: 10.4161/hv.5.4.7457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kinsey BM, Jackson DC, Orson FM. Anti-drug vaccines to treat substance abuse. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2009;87:309–314. doi: 10.1038/icb.2009.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hicks MJ, De BP, Rosenberg JB, Davidson JT, Moreno AY, Janda KD, Wee S, Koob GF, Hackett NR, Kaminsky SM, Worgall S, Toth M, Mezey JG, Crystal RG. Cocaine Analog Coupled to Disrupted Adenovirus, A Vaccine Strategy to Evoke High-titer Immunity Against Addictive Drugs. Mol. Ther. 2011;19(3):612–619. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martell BA, Mitchell E, Poling J, Gonsai K, Kosten TR. Vaccine pharmacotherapy for the treatment of cocaine dependence. Biol. Psychiatry. 2005;58:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carrera MR, Ashley JA, Zhou B, Wirsching P, Koob GF, Janda KD. Cocaine vaccines antibody protection against relapse in a rat model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:6202–6206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.6202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orson FM, Kinsey BM, Singh RA, Wu Y, Gardner T, Kosten TR. The future of vaccines in the management of addictive disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2007;9:381–387. doi: 10.1007/s11920-007-0049-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martell BA, Orson FM, Poling J, Mitchell E, Rossen RD, Gardner T, Kosten TR. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2009;66:1116–1123. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orson FM, Kinsey BM, Singh RA, Wu Y, Gardner T, Kosten TR. Substance abuse vaccines. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2008;1141:257–269. doi: 10.1196/annals.1441.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao Y, Orson FM, Kinsey B, Kosten T, Brimijoin S. The concept of pharmacologic cocaine interception as a treatment for drug abuse. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2010;187:421–424. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson MW, Ettinger RH. Active cocaine immunization attenuates the discriminative properties of cocaine. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2000;8:163–167. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kantak KM, Collins SL, Lipman EG, Bond J, Giovanoni K, Fox BS. Evaluation of anti-cocaine antibodies and a cocaine vaccine in a rat self-administration model. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2000;148:251–262. doi: 10.1007/s002130050049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haney M, Kosten TR. Therapeutic vaccines for substance dependence. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2004;3:11–18. doi: 10.1586/14760584.3.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wee S, Hicks MJ, De BP, Rosenberg JB, Moreno AY, Kaminsky SM, Janda KD, Crystal RG, Koob GF. Novel Cocaine Vaccine Linked to a Disrupted Adenovirus Gene Transfer Vector Blocks Cocaine Psychostimulant and Reinforcing Effects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011 doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.200. Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Redwan RM, Larsen NA, Zhou B, Wirsching P, Janda KD, Wilson IA. Expression characterization of a humanized cocaine-binding antibody. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2003;82:612–618. doi: 10.1002/bit.10598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norman A, Norman MK, Buesing WR, Tabet MR, Tsibulsky VL, Ball WJ. The effect of a chimeric human/murine anti-cocaine monoclonal antibody on cocaine self-administration in rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009;328:873–881. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.146407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norman AB, Tabet MR, Norman MK, Buesing WR, Pesce AJ, Ball WJ. Achimeric human/murine anticocaine monoclonal antibody inhibits the distribution of cocaine to the brain in mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2007;320:145–153. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.111781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Landry DW, Zhao K, Yang GX, Glickman M, Georgiadis TM. Antibody-catalyzed degradation of cocaine. Science. 1993;259:1899–1901. doi: 10.1126/science.8456315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan Y, Gao D, Zhan CG. Modeling the catalysis of anti-cocaine catalytic antibody competing reaction pathways and free energy barriers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:5140–5149. doi: 10.1021/ja077972s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cashman JR, Berkman CE, Underiner GE. Catalytic antibodies that hydrolyze (−)-cocaine obtained by a high-throughput procedure. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;293:952–961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larsen NA, de Prada P, Deng SX, Mittal A, Braskett M, Zhu X, Wilson IA, Landry DW. Crystallographic and biochemical analysis of cocaine-degrading antibody 15A10. Biochemistry. 2004;43:8067–8076. doi: 10.1021/bi049495l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mets B, Winger G, Cabrera C, Seo S, Jamdar S, Yang G, Zhao K, Briscoe RJ, Almonte R, Woods JH, Landry DW. A catalytic antibody against cocaine prevents cocaine's reinforcing, and toxic effects in rats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:10176–10181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fang J, Qian JJ, Yi S, Harding TC, Tu GH, VanRoey M, Jooss K. Stable antibody expression at therapeutic levels using the 2A peptide. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:584–590. doi: 10.1038/nbt1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Misra AL, Giri VV, Patel MN, Alluri VR, Mule SJ. Disposition and metabolism of [3H] cocaine in acutely and chronically treated monkeys. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1977;2:261–272. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(77)90004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ndikum-Moffor FM, Schoeb TR, Roberts SM. Liver toxicity from norcocaine nitroxide, an N-oxidative metabolite of cocaine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998;284:413–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brzezinski MR, Abraham TL, Stone CL, Dean RA, Bosron WF. Purification and characterization of a human liver cocaine carboxylesterase that catalyzes the production of benzoylecgonine the formation of cocaethylene from alcohol, and cocaine. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1994;48:1747–1755. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90461-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brzezinski MR, Spink BJ, Dean RA, Berkman CE, Cashman JR, Bosron WF. Human liver carboxylesterase hCE-1 binding specificity for cocaine heroin, and their metabolites and analogs. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1997;25:1089–1096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schuelke GS, Konkol RJ, Terry LC, Madden JA. Effect of cocaine metabolites on behavior, possible neuroendocrine mechanisms. Brain Res. Bull. 1996;39:43–48. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(95)02040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morishima HO, Whittington RA, Iso A, Cooper TB. The comparative toxicity of cocaine and its metabolites in conscious rats. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:1684–1690. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199906000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inaba T, Stewart D, Kalow W. Metabolism of cocaine in man. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1978;23:547–552. doi: 10.1002/cpt1978235547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stewart DJ, Inaba T, Tang BK, Kalow W. Hydrolysis of cocaine in human plasma by cholinesterase. Life Sci. 1977;20:1557–1564. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(77)90448-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duysen EG, Li B, Darvesh S, Lockridge O. Sensitivity of butyrylcholinesterase knockout mice to (--)-huperzine A and donepezil suggests humans with butyrylcholinesterase deficiency may not tolerate these Alzheimer's disease drugs and indicates butyrylcholinesterase function in neurotransmission. Toxicology. 2007;233:60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2006.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gorelick DA. Enhancing cocaine metabolism with butyrylcholinesterase as a treatment strategy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;48:159–165. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koetzner L, Woods JH. Characterization of butyrylcholinesterase antagonism of cocaine-induced hyperactivity. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2002;30:716–723. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bresler MM, Rosser SJ, Basran A, Bruce NC. Gene cloning and nucleotide sequencing and properties of a cocaine esterase from Rhodococcus sp. strain MB1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000;66:904–908. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.3.904-908.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turner JM, Larsen NA, Basran A, Barbas CF, 3rd, Bruce NC, Wilson IA, Lerner RA. Biochemical characterization and structural analysis of a highly proficient cocaine esterase. Biochemistry. 2002;41:12297–12307. doi: 10.1021/bi026131p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cooper ZD, Narasimhan D, Sunahara RK, Mierrzejewski P, Jutkiewicz EM, Larsen NA, Wilson IA, Landry DW, Woods JH. Rapid and robust protection against cocaine-induced lethality in rats by the bacterial cocaine esterase. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006;70:1885–1891. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.025999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Collins GT, Brim RL, Narasimhan D, Ko MC, Sunahara RK, Zhan CG, Woods JH. Cocaine esterase prevents cocaine-induced toxicity, the ongoing intravenous self-administration of cocaine in rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009;331:445–455. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.150029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Collins GT, Carey KA, Narasimhan D, Nichols J, Berlin AA, Lukacs NW, Sunahara RK, Woods JH, Ko MC. Amelioration of the cardiovascular effects of cocaine in rhesus monkeys by a long-acting mutant form of cocaine esterase. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:1047–1059. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xie W, Altamirano CV, Bartels CF, Speirs RJ, Cashman JR, Lockridge O. An improved cocaine hydrolase, the A328Y mutant of human butyrylcholinesterase is 4-fold more efficient. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999;55:83–91. doi: 10.1124/mol.55.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun H, Shen ML, Pang YP, Lockridge O, Brimijoin S. Cocaine metabolism accelerated by a re-engineered human butyrylcholinesterase. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002;302:710–716. doi: 10.1124/jpet.302.2.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun H, El Yazal J, Lockridge O, Schopfer LM, Brimijoin S, Pang YP. Predicted Michaelis-Menten complexes of cocaine- butyrylcholinesterase. Engineering effective butyrylcholinesterase mutants for cocaine detoxication. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:9330–9336. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006676200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pan Y, Gao D, Yang W, Cho H, Zhan CG. Free energy perturbation (FEP) simulation on the transition states of cocaine hydrolysis catalyzed by human butyrylcholinesterase and its mutants. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:13537–13543. doi: 10.1021/ja073724k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang W, Xue L, Fang L, Chen X, Zhan CG. Characterization of a high-activity mutant of human butyrylcholinesterase against (−)-cocaine. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2010;187:148–152. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xue Y, Steketee JD, Rebec GV, Sun W. Activation of D (2) -like receptors in rat ventral tegmental area inhibits cocaine-reinstated drug-seeking behavior. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2011;33(7):1291–1298. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07591.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xue L, Ko MC, Tong M, Yang W, Hou S, Fang L, Liu J, Zheng F, Woods JH, Tai HH, Zhan CG. Design preparation characterization of high-activity mutants of human butyrylcholinesterase specific for detoxification of cocaine. Mol. Pharmacol. 2011;79:290–297. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.068494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun H, Pang Y-P, Lockridge O, Brimijoin S. Reengineering butyrylcholinesterase as a cocaine hydrolase. Mol. Pharmacol. 2002;621:220–224. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gao Y, Brimijoin S. An engineered cocaine hydrolase blunts, and reverses cardiovascular responses to cocaine in rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004;310:1046–1052. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.068122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gao Y, LaFleur D, Shah R, Zhao Q, Singh M, Brimijoin S. An albumin-butyrylcholinesterase for cocaine toxicity, and addiction catalytic pharmacokinetic properties. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2008;175:83–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brimijoin S, Gao Y, Anker JJ, Gliddon LA, Lafleur D, Shah R, Zhao Q, Singh M, Carroll ME. A cocaine hydrolase engineered from human butyrylcholinesterase selectively blocks cocaine toxicity and reinstatement of drug seeking in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2715–2725. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carroll ME, Gao Y, Brimijoin S, Anker JJ. Effects of cocaine hydrolase on cocaine self-administration under a PR schedule and during extended access (escalation) in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2011;213:817–829. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2040-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koob G, Kreek MJ. Stress dysregulation of drug reward pathways and the transition to drug dependence. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2007;164:1149–1159. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.05030503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abuchowski A, McCoy JR, Palczuk NC, van Es T, Davis FF. Effectof covalent attachment of polyethylene glycol on immunogenicity, and circulating life of bovine liver catalase. J. Biol. Chem. 1977;252:3582–3586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gao Y, Atanasova E, Sui N, Pancook JD, Watkins JD, Brimijoin S. Gene transfer of cocaine hydrolase suppresses cardiovascular responses to cocaine in rats. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005;67:204–211. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.006924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Papadakis ED, Nicklin SA, Baker AH, White SJ. Promoters control elements designing expression cassettes for gene therapy. Curr. Gene Ther. 2004;4:89–113. doi: 10.2174/1566523044578077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pancook JD, Pecht G, Ader M, Mosko M, Lockridge O, Watkins JD. Application of directed evolution technology to optimize the cocaine hydrolase activity of human butyrylcholinesterase. FASEB J. 2003;17:A565. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Parks RJ, Chen L, Anton M, Sankar U, Rudnicki MA, Graham FL. A helper-dependent adenovirus vector system, removal of helper virus by Cre-mediated excision of the viral packaging signal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:13565–13570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gao Y, Brimijoin S. Lasting reduction of cocaine action in neostriatum--a hydrolase gene therapy approach. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009;330:449–457. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.152231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Heffron PF. Actions of the selective inhibitor of cholinesterase tetramonoisopropyl pyrophosphortetramide on the rat phrenic nerve-diaphragm preparation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1972;46:714–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1972.tb06896.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wise RA, Kiyatkin EA. Differentiating the rapid actions of cocaine. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011;12:479–484. doi: 10.1038/nrn3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Scott EM. Inheritance of two types of deficiency of human serum cholinesterase. Ann. Hum. Genet. 1973;37:139–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1973.tb01821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hodgkin W, Giblett ER, Levine H, Bauer W, Motulsky AG. Complete pseudocholinesterase deficiency, genetic and immunologic characterization. J. Clin. Invest. 1965;44:486–493. doi: 10.1172/JCI105162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.La Du BN, Lockridge O. Molecular biology of human serum cholinesterase. Fed. Proc. 1986;45:2965–2969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nachon F, Nicolet Y, Viguie N, Masson P, Fontecilla-Camps JC, Lockridge O. Engineering of a monomeric and low-glycosylated form of human butyrylcholinesterase expression, purification characterization, and crystallization. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:630–637. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lockridge O, Eckerson HW, La Du BN. Interchain disulfide bonds, subunit organization in human serum cholinesterase. J. Biol. Chem. 1979;254:8324–8330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lockridge O, Bartels CF, Vaughan TA, Wong CK, Norton SE, Johnson LL. Complete amino acid sequence of human serum cholinesterase. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:549–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Whittaker M. Cholinesterase. Basel: Karger; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chatonnet A, Lockridge O. Comparison of butyrylcholinesterase, and acetylcholinesterase. Biochem. J. 1989;260:625–634. doi: 10.1042/bj2600625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Saxena A, Sun W, Fedorko JM, Koplovitz I, Doctor BP. Prophylaxis with human serum butyrylcholinesterase protects guinea pigs exposed to multiple lethal doses of soman or VX. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2011;81:164–169. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Saxena A, Sun W, Luo C, Doctor BP. Human serum in butyrylcholinesterasein vitro and in vivo stability pharmacokinetics and safety in mice. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2005;157–158:199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Weber A, Butterweck H, Mais-Paul U, Teschner W, Lei L, Muchitsch EM, Kolarich D, Altmann F, Ehrlich HJ, Schwarz HP. Biochemical, molecular and preclinical characterization of a double-virus-reduced human butyrylcholinesterase preparation designed for clinical use. Vox Sang. 2011;100:285–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2010.01415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jozkowicz A, Dulak J. Helper-dependent adenoviral vectors in experimental gene therapy. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2005;52:589–599. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Brunetti-Pierri N, Ng P. Helper-dependent adenoviral vectors for liver-directed gene therapy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011;20:R7–R13. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vetrini F, Ng P. Liver-directed gene therapy with helper-dependent adenoviral vectors, current state of the art future challenges. Curr. Pharm. Design. 2011;17:2488–2499. doi: 10.2174/138161211797247532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mingozzi F, High KA. Therapeutic in vivo gene transfer for genetic disease using AAV, progress, challenges. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;12:341–355. doi: 10.1038/nrg2988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Berns KI, Hauswirth WW. Adeno-associated viruses. Adv. Virus Res. 1979;25:407–449. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60574-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mitani K, Graham FL, Caskey CT, Kochanek S. Rescue propagation partial purification of a helper virus-dependent adenovirus vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:3854–3858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kochanek S, Clemens PR, Mitani K, Chen HH, Chan S, Caskey CT. A new adenoviral vector, Replacement of all viral coding sequences with 28 kb of DNA independently expressing both full-length dystrophin beta-galactosidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:5731–5736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Morral N, O'Neal W, Rice K, Leland M, Kaplan J, Piedra PA, Zhou H, Parks RJ, Velji R, Aguilar-Córdova E, Wadsworth S, Graham FL, Kochanek S, Carey KD, Beaudet AL. Administration of helper-dependent adenoviral vectors, sequential delivery of different vector serotype for long-term liver-directed gene transfer in baboons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:12816–12821. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kim IH, Jozkowicz A, Piedra PA, Oka K, Chan L. Lifetime correction of genetic deficiency in mice with a single injection of helper-dependent adenoviral vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:13282–13287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241506298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Muruve DA. The innate immune response to adenovirus vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 2004;15:1157–1166. doi: 10.1089/hum.2004.15.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Brunetti-Pierri N, Palmer DJ, Beaudet AL, Carey KD, Finegold M, Ng P. Acute toxicity after high-dose systemic injection of helper-dependent adenoviral vectors into nonhuman primates. Hum. Gene Ther. 2004;15:35–46. doi: 10.1089/10430340460732445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Raper SE, Chirmule N, Lee FS, Wivel NA, Bagg A, Gao GP, Wilson JM, Batshaw ML. Fatal systemic inflammatory response syndrome in a ornithine transcarbamylase deficient patient following adenoviral gene transfer. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2003;80:148–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2003.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Seregin SS, Appledorn DM, McBride AJ, Schuldt NJ, Aldhamen YA, Voss T, Wei J, Bujold M, Nance W, Godbehere S, Amalfitano A. Transient pretreatment with glucocorticoid ablates innate toxicity of systemically delivered adenoviral vectors without reducing efficacy. Mol. Ther. 2009;17:685–696. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dong JY, Fan PD, Frizzell RA. Quantitative analysis of the packaging capacity of recombinant adeno-associated virus. Hum. Gene Ther. 1996;7:2101–2112. doi: 10.1089/hum.1996.7.17-2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kaplitt MG, Leone P, Samulski RJ, Xiao X, Pfaff DW, O'Malley KL, During MJ. Long-term gene expression, and phenotypic correction using adeno-associated virus vectors in the mammalian brain. Nat. Genet. 1994;8:148–154. doi: 10.1038/ng1094-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Koornneef A, Maczuga P, van Logtenstein R, Borel F, Blits B, Ritsema T, van Deventer S, Petry H, Konstantinova P. Apolipoprotein Bknockdown by AAV-delivered shRNA lowers plasma cholesterol in mice. Mol. Ther. 2011;19:731–740. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Choi SH, Lee HC. Long-term, antidiabetogenic effects of GLP-1 gene therapy using a double-stranded, adeno-associated viral vector. Gene Ther. 2011;18:155–163. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Brantly ML, Chulay JD, Wang L, Mueller C, Humphries M, Spencer LT, Rouhani F, Conlon TJ, Calcedo R, Betts MR, Spencer C, Byrne BJ, Wilson JM, Flotte TR. Sustained transgene expression despite T lymphocyte responses in a clinical trial of rAAV1-AAT gene therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:16363–16368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904514106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Manno CS, Pierce GF, Arruda VR, Glader B, Ragni M, Rasko JJ, Ozelo MC, Hoots K, Blatt P, Konkle B, Dake M, Kaye R, Razavi M, Zajko A, Zehnder J, Rustagi PK, Nakai H, Chew A, Leonard D, Wright JF, Lessard RR, Sommer JM, Tigges M, Sabatino D, Luk A, Jiang H, Mingozzi F, Couto L, Ertl HC, High KA, Kay MA. Successful transduction of liver in hemophilia by AAV-Factor IX, and limitations imposed by the host immune response. Nat. Med. 2006;12:342–347. doi: 10.1038/nm1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wagner JA, Messner AH, Moran ML, Daifuku R, Kouyama K, Desch JK, Manley S, Norbash AM, Conrad CK, Friborg S, Reynolds T, Guggino WB, Moss RB, Carter BJ, Wine JJ, Flotte TR, Gardner P. Safety and biological efficacy of an adeno-associated virus vector-cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (AAV-CFTR) in the cystic fibrosis maxillary sinus. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:266–274. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199902000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Christine CW, Starr PA, Larson PS, Eberling JL, Jagust WJ, Hawkins RA, VanBrocklin HF, Wright JF, Bankiewicz KS, Aminoff MJ. Safety and tolerability of putaminal AADC gene therapy for Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2009;73:1662–1669. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c29356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jaski BE, Jessup ML, Mancini DM, Cappola TP, Pauly DF, Greenberg B, Borow K, Dittrich H, Zsebo KM, Hajjar RJ. Calcium Up-Regulation by Percutaneous Administration of Gene Therapy In Cardiac Disease (CUPID) Trial Investigators. Calcium upregulation by percutaneous administration of gene therapy in cardiac disease (CUPID Trial), a first-in-human phase 1/2 clinical trial. J. Card. Fail. 2009;15:171–181. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mease PJ, Wei N, Fudman EJ, Kivitz AJ, Schechtman J, Trapp RG, Hobbs KF, Greenwald M, Hou A, Bookbinder SA, Graham GE, Wiesenhutter CW, Willis L, Ruderman EM, Forstot JZ, Maricic MJ, Dao KH, Pritchard CH, Fiske DN, Burch FX, Prupas HM, Anklesaria P, Heald AE. Safety tolerability clinical outcomes after intraarticular injection of a recombinant adeno-associated vector containing a tumor necrosis factor antagonist gene, results of a phase 1/2 Study. J. Rheumatol. 2010;37:692–703. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.McCarty DM, Fu H, Monahan PE, Toulson CE, Naik P, Samulski RJ. Adeno-associated virus terminal repeat (TR) mutant generates self-complementary vectors to overcome the rate-limiting step to transduction in vivo . Gene Ther. 2003;10:2112–2118. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Michelfelder S, Trepel M. Adeno-associated viral vectors and their redirection to cell-type specific receptors. Adv. Genet. 2009;67:29–60. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2660(09)67002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]