Abstract

In 2011, an estimated 50.2 million adults and children lived in US households with food insecurity, a condition associated with adverse health effects across the life span. Relying solely on parent proxy may underreport the true prevalence of child food insecurity. The present study sought to understand mothers’ and children’s (aged 6–11 y) perspectives and experiences of child food insecurity and its seasonal volatility, including the effects of school-based and summertime nutrition programs. Forty-eight Mexican-origin mother-child dyads completed standardized, Spanish-language food-security instruments during 2 in-home visits between July 2010 and March 2011. Multilevel longitudinal logistic regression measured change in food security while accounting for correlation in repeated measurements by using a nested structure. Cohen’s κ statistic assessed dyadic discordance in child food insecurity. School-based nutrition programs reduced the odds of child food insecurity by 74% [OR = 0.26 (P < 0.01)], showcasing the programs’ impact on the condition. Single head of household was associated with increased odds of child food insecurity [OR = 4.63 (P = 0.03)]. Fair dyadic agreement of child food insecurity was observed [κ = 0.21 (P = 0.02)]. Obtaining accurate prevalence rates and understanding differences of intrahousehold food insecurity necessitate measurement at multiple occasions throughout the year while considering children’s perceptions and experiences of food insecurity in addition to parental reports.

Introduction

Household food insecurity is defined as reduced or uncertain access to sufficient healthful and safe foods or the limited ability to acquire enough food in socially acceptable ways (1). In 2011, 17.9 million US households (14.9%) were food insecure. Household food insecurity encompasses low food security (a reduction in food quality, variety, or desirability and sometimes dietary intake) and very low food security (reduced energy intake and change in eating habits at multiple times over the course of a year). In 2011, 10% (nearly 3.9 million) of US households with children experienced child food insecurity— the most severe form of the condition (2).

Food insecurity among Hispanic and Mexican-origin US households exceeds national estimates. In 2011, 26.2% of Hispanic families in the United States were food insecure, and of US households with child food insecurity, 17.4% were Hispanic (2). In Texas border colonias, or communities that often lack sanitary conditions, water/sewer systems, paved roads, frequently contain self-built homes (3), and whose inhabitants face economic and locational disadvantages (4), food insecurity is even more prevalent than federal calculations indicate. In 2009 the Colonia Household and Community Food Resource Assessment surveyed 610 households in colonias near the towns of Progreso and La Feria in Hidalgo and Cameron counties along the Texas-Mexico border. Seventy-eight percent were food insecure at the household, adult, or child level, whereas 61.8% of households with children (n = 484) experienced child food insecurity (5). In a separate analysis of Hidalgo County colonias residents, 64% of children (aged 6–11 y) self-reported low or very low food security using the 9-item Food Security Survey Module for Youth (6). Because such south Texas colonias may represent an archetype for immigrant destinations elsewhere in the United States (7), these measurements in food insecurity are a nutrition and public health concern of national importance.

Food insecurity and health are inextricably linked. Living in a food-insecure household is associated with poorer self-reported physiologic and psychological health (8, 9), increased rates of overweight and obesity (10, 11), and diminished scores on academic, behavioral, and social scales compared with individuals in food-secure homes (12). The 50.2 million people in the United States who lived in food-insecure households in 2011 (2) are all at risk of detrimental life-span health effects associated with this preventable condition.

Much food-security research relies on proxy reports and cross-sectional analyses (13–15), but parental reports of children’s food security may present inaccurate or incomplete representations of children’s realities. For example, in demonstrating the multidimensionality of food security, Nord and Bickel (16) compared the prevalence of child hunger when reported in 2 ways: first, by using all household-referenced items of the 18-item Household Food Security Survey Module, and second, by restricting measures of child hunger to only the child-referenced items using responses from the same families. Child hunger was found to be prevalent in 0.87% of homes using household hunger items but prevalent in 1.12% of homes when using child-referenced items only, indicating a 29% greater prevalence. Such an increase highlights the notion that child hunger may be underreported when relying exclusively on household-level measures. More research is needed to understand differences in food security within households. Pairing the youth module in conjunction with the household module may help scientists, policy makers, and service providers obtain an improved understanding of differential food insecurity among multiple household members.

Longitudinal analyses that consider correlation are a preferred methodology because the temporal role between exposure and outcome can be measured, reverse causality is avoided, confounding due to unmeasured variables is minimized, and rates of type 1 error are reduced (17, 18). Evidence suggests that summer meals offered jointly through the National School Lunch Program (NSLP)5 and the Summer Food Service Program (SFSP) may reduce household food insecurity (19); however, the number of meals provided and participation rates differ greatly between school and summertime (20). Thus, longitudinal assessments ought to consider the seasonal nature of food security and the impact of school-based nutrition programs and the SFSP on child food insecurity during school and summertime.

Research on children’s ability to reliably self-report food security is ongoing. Fram et al. (21) demonstrated that children as young as 9 y old are willing and able to discuss food security, whereas Connell et al. (22) found that children as young as 12 y understand concepts of household food security and can self-report using a standardized instrument. Perhaps, then, preadolescents are able to reliably self-report food security. Interviews sponsored by the authors and led by promotora researchers (State of Texas–certified community health workers trained in research methods) indicated that colonia-dwelling Mexican-origin children (6–11 y old) understand concepts of food security and are willing to report their experiences.

The present study had 2 principal objectives: 1) to assess seasonal fluctuation in children’s food security, as reported by mothers and children, considering the correlation of repeated measurements; and 2) to examine differences in intrahousehold reporting of children’s food security, accounting for the correlation inherent in the nested structure. The primary hypothesis was that both mother- and child-reported rates of child food insecurity will decrease from summer to school months, when many children in the current sample participate in school-based nutrition programs. The secondary hypothesis was that when mothers and children are interviewed separately, they will report different experiences of child food security.

Participants and Methods

Setting

Study participants were residents of 40 spatially selected colonias within 2 functionally rural areas of Hidalgo County along the Texas-Mexico border in the Lower Rio Grande Valley. The study setting and selection criteria are explained in expanded detail elsewhere (6) and discussed briefly here. These colonias are communities that may lack sanitary conditions, water/sewer systems, and paved roads; often consist of self-built housing (3); and are inhabited predominantly by people of Hispanic origin (˃93%) (23). Such Hidalgo County colonias residents encounter economic and locational hardships (4), encompass a difficult-to-reach population, and may mirror newly emerging immigrant destinations in other parts of the United States (7). Employment opportunities available to colonias residents include skilled craft (painters, construction workers, and electrical assistants), laborers, health care providers, retail sales, and restaurant staff.

Study sample

Promotora researchers recruited mother-child dyads for a cohort study; 25 dyads were from Alton area colonias in the western part of the county, whereas 25 dyads resided in San Carlos area colonias (eastern part of the county). Two families did not complete both home visits; thus, analysis included complete data for 48 pairs. Promotora researchers were native Spanish speakers, colonia residents, and integral team members. They were involved with research protocol development, cultural and linguistic appropriateness of research protocol and measures, participant recruitment, and data collection. Promotora researchers recruited a nonrandom sample of participants from 40 spatially selected colonias in 20 census block groups (CBGs), which were selected in consultation with community partners and identified from prior work as areas of high socioeconomic deprivation, and included 10 CBGs in the Alton area and 10 CBGs in the San Carlos area. The sample included at least 1 colonia in each of the 20 CBGs and no more than 2 participant households within the same colonia. Study inclusion criteria required a dyad be composed of a mother and 1 child 6–11 y of age who resided full-time in the home. Promotora researchers explained the study (assessments, confidentiality, and financial incentive) to mothers who provided consent for themselves and for the child, and children provided assent to participate. All materials and protocols were approved by the Texas A&M University Institutional Review Board.

Data collection

Data were collected through promotora researcher–administered surveys in participants’ homes during 2 waves between July 2010 and March 2011. Wave 1 (summertime) assessments were conducted between July and August 2010 and wave 2 (school-year) assessments were completed from February to March 2011. All data were collected in Spanish (the native language for study participants) using translations provided by a certified multilingual translator and verified by promotora researchers.

Measurements

Mothers.

Mothers’ perceptions of children’s food security during the previous 4 wk were assessed by using the 8-item US Children’s Food Security Scale, developed with the USDA Economic Research Service and validated for use among Hispanic populations (24). The 8 items that mothers reported for children included the following: balanced diet for children, relying on low-cost foods for children’s meals, children not eating enough, cutting size of children’s meals, children skipping meals and the frequency of doing so, children going hungry, and children not eating for a full day. Mothers completed the child food-security scale once during each of the 2 waves.

Mothers reported demographic characteristics including age, highest level of education completed, marital status, race/ethnicity (Hispanic, Mexican, Mexican American, or other), country of birth, residential composition (number of adults and children residing in the household), total household monthly income, employment status of all adults and children, and participation in nutrition assistance programs, such as SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program), WIC (Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children), NSLP, the School Breakfast Program (SBP), and SFSP.

Children.

At each wave, children self-reported perceptions and experiences of food security during the previous 4 wk by using the 9-item Food Security Survey Module for Youth (25). The 9 food-security items that children reported include worrying about the amount of food available in the home, running out of food, having balanced meals, relying on low-cost foods, reducing the size of meals, eating less, skipping meals, going hungry, and not eating for a full day. Items that children reported were similar to mothers’ items with the addition of worrying about the amount of food supplies and running out of food supplies in the household. Whereas mothers reported the majority of demographic covariates, children self-reported age during the first in-home visit. At each visit, promotora researchers interviewed children out of sight and hearing from mothers to avoid undue parental influence.

Analysis

Data were entered into Access databases (Microsoft Corp.) from hard copy, and all entries were verified by an independent coder. In the event of a discrepancy, participants were contacted for a resolution, if possible, or entries were marked as missing if too much time had passed for a precise measurement. Mother- and child-reported demographic characteristics were time-invariant (using baseline reports only) to avoid complications in longitudinal analyses. For food-security scales, affirmative response options [“Often true,” “Sometimes true,” (household scale) and “A lot,” “Sometimes” (child scale)] were coded as “yes” whereas “Never true” and “Never” were coded as “no” for each binary variable. Each affirmative response was coded as 1 whereas a negative response was coded as zero. A continuous score was determined by summing all affirmative responses (maximum score for mother report: 8; maximum score for child report: 9) (25, 26). Categorical level of food security was ascribed through USDA Economic Research Service recommendations; for mothers’ reports, 0 = high food security, 1 = marginal food security, 2–4 = low food security, and 5–8 = very low food security (26). For children’s reports, 0 = high food security, 1 = marginal food security, 2–5 = low food security, and 6–9 = very low food security (25). Households with high and marginal food security were considered food secure, whereas those with low and very low food security were considered food insecure. Descriptive statistics (means, SDs, n, %) were calculated for each demographic covariate.

Longitudinal analyses were conducted to assess seasonal change in children’s food security, as perceived by mothers and experienced by children during summer and school. A single multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression model was estimated to account for the correlation inherent in repeated measurements and shared living environments among mother-child dyads using Stata command xtmemixed (StataCorp LP). The multilevel model nested children within households. A group indicator variable distinguished mothers from children, which allowed researchers to compare the odds of reporting food insecurity between mothers and children. The model was adjusted for several demographic covariates, overall model fit was assessed by Wald χ2 statistic, and significance was determined by an α < 0.05.

Discordance among mother and child reports of child food insecurity across both waves was assessed with Cohen’s κ statistic. Landis and Koch (27) ascribe a κ < 0.00 as “poor,” 0.00–0.20 as “slight,” 0.21–0.40 as “fair,” 0.41–0.60 as “moderate,” 0.61–0.80 as “substantial,” and 0.81–1.00 as “almost perfect” such labels were used to evaluate discordance in the present analysis. All analyses were performed in Stata statistical software, release 12 (StataCorp LP).

Results

Baseline demographic characteristics of study participants are shown in Table 1. At baseline, characteristics of food-secure and food-insecure households (determined by mothers’ reports) differed only in regard to child age; children living in food-insecure households were slightly younger than were children living in food-secure households [t = 2.10 (P = 0.04)] (data not shown). All mothers self-reported Hispanic or Mexican race and ethnicity.

TABLE 1.

Baseline self-reported demographic characteristics of mother-child dyads1

| Characteristic | Value |

| Mothers’ age, y | 34.7 ± 7.0 |

| Child’s age, y | 8.5 ± 1.4 |

| Child sex | |

| Female, n (%) | 28 (58.0) |

| Total children, n | 3.6 ± 1.3 |

| Individuals in residence, n | 5.7 ± 1.4 |

| Mothers’ education, y | 8.4 ± 2.4 |

| Mothers’ country of birth, n (%) | |

| United States | 4 (8.3) |

| Mexico | 44 (91.7) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Married or cohabitating | 42 (87.5) |

| Employment,2 n (%) | |

| Mother | 7 (14.6) |

| Father | 39 (81.3) |

| Other adults | 4 (8.3) |

| Total monthly income, n (%) | |

| Missing | 10 (20.8) |

| ≤$699 | 4 (8.3) |

| ≥$700 | 34 (70.8) |

| Nutrition assistance programs, n (%) | |

| NSLP | 48 (100.0) |

| SBP | 48 (100.0) |

| SFSP | 9 (18.8) |

| SNAP | 41 (85.4) |

| WIC | 23 (47.9) |

Values are means ± SDs or n (%), n = 48. NSLP, National School Lunch Program participation during the school year; SBP, School Breakfast Program participation during the school year; SFSP, Summer Food Service Program participation during the summer; SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Full-time or part-time.

During the summer, 8 (16.7%) mothers considered their children to have high food security, 12 (25.0%) children were marginally food secure, 26 (54.2%) children had low food security, whereas 2 (4.2%) children had very low food security (percentages do not add to 100% due to rounding). At the same point in time, 8 (16.7%) children reported high food security, 10 (20.8%) had marginal food security, 25 (52.1%) had low food security, and 5 (10.4%) had very low food security at the child level. During the school year, 1 (2.1%) mother reported that her child had high food security, 24 (50%) children were marginally food secure, and 23 (47.9%) children experienced low food security. At the same time, 30 (62.5%) children self-reported high food security, 9 (18.7%) were marginally food secure, 6 (12.5%) had low food security, and 3 (6.2%) had very low food security while in school.

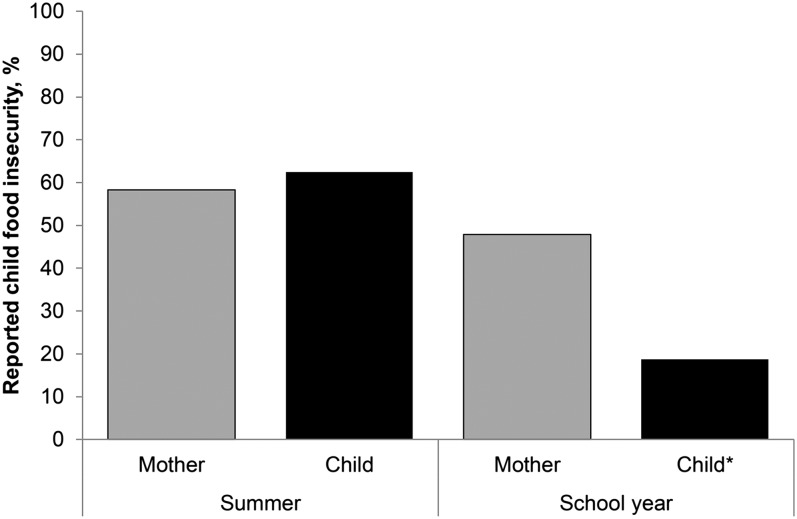

According to children, food insecurity was more prevalent in the summer than during school [62.5 vs. 18.8%, z = 2.3 (P = 0.02)]; from mothers’ perspectives, there was no change in child food security from summer to school months [58.3 vs. 47.9%, z = 0.74 (P = 0.46)] (see Fig. 1). Although not significant, children and mothers reported different rates of food insecurity during the summer [62.5 vs.58.3%, z = 0.33 (P = 0.75)] and school year [18.7 vs. 47.9%, z = 1.52 (P = 0.13)]. Adjusted ORs from the multilevel longitudinal model, including the significant effects of school-based nutrition programs and single parent status on children’s food security, are shown in Table 2. Overall, the model was an improved fit of the data [Wald χ210 = 25.37 (P < 0.01, Akaike Information Criterion = 253.60)]. Discordance analysis revealed fair mother-child agreement across the 2 waves of data [κ = 0.21 (P = 0.02)].

FIGURE 1.

Proportion of child food insecurity as reported by mothers and children during the summer and school year. Values are percentages of reported child food insecurity, n = 48 dyads. *Different from summer, P = 0.02.

TABLE 2.

Adjusted ORs for multilevel longitudinal assessment of child food insecurity during summer and school months1

| Food insecurity | |

| Mothers’ group2 | 1.91 (0.99, 3.67) |

| Self-reported Mexican race3 | 4.47 (1.51, 13.23)** |

| Single parent | 4.63 (1.12, 19.19)* |

| School nutrition programs4 | 0.26 (0.12, 0.52)** |

| SFSP | 0.90 (0.23, 3.54) |

| SNAP | 1.17 (0.39, 3.50) |

| Education | 1.03 (0.85, 1.25) |

| Household size | 1.17 (0.86, 1.58) |

| Household income | 0.92 (0.71, 1.17) |

| Nativity5: Mexico | 0.91 (0.14, 5.75) |

Values are adjusted ORs (95% CI) derived from multilevel longitudinal logistic regression model and adjusted for all other variables listed in the table. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. SFSP, Summer Food Service Program; SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

Relative to children.

Relative to self-reported Hispanic ethnicity.

School Breakfast Program and/or National School Lunch Program.

Relative to United States.

Discussion

In the present analysis, 48 Mexican-origin mother-child dyads were followed from summer to school months to ascertain changes in child food security using analytic techniques that accounted for correlation attributable to repeated measurements and shared living environments. Consistent with both hypotheses, there was dyadic discordance in the prevalence of child food insecurity and the condition was less severe during the school year compared with summertime, after holding constant race/ethnicity, education, household income, residential composition, marital status, nativity, SNAP, SFSP, and child participation in school-based nutrition programs.

The school-based nutrition programs SBP and NSLP buffered children from the effects of food insecurity in the present sample, a finding supported by the estimate that 2 in-school meals per day (5 d/wk) satisfy about half of the energy needs for children (28). Summertime lack of SBP and NSLP may influence the increased rates of child food insecurity. Whereas SFSP and NSLP summertime meals (NSLP provides summer funding) (29) may ameliorate the seasonal effects of worsening household food security (19), the SFSP program has had limited success in Texas. Barriers to SFSP participation may include inconvenient site location, the need for private transportation, language, and other information obstacles. In 2010, 9.2% of Texas NSLP participants also received meals from the SFSP, ranking the state 41st in satisfying the nutritional needs of children (20). Increased effort must be made to ensure that children have equal access to federally funded nutrition programs regardless of season.

Among the present sample, it appears likely that access to school-based nutrition programs was the driving factor in seasonal fluctuation of children’s food security, and that volatility in parental employment did not play a significant role. Being employed during the summer did not differ from during the school year for fathers [82 vs. 76% (P = 0.50)] or mothers [14 vs. 23% (P = 0.51)].

The second aim of this study was to examine discordance in child food insecurity on the basis of mothers’ and children’s experiences and perceptions. During the summer, children’s reports of food insecurity (62.5%) exceeded those by mothers (58.3%). From summer to school year, mothers’ perceived child food insecurity lessened by nearly 11% (from 58.3 to 47.9%), but during the same time frame children’s reports of food insecurity decreased from 62.5 to 18.7%. The results indicate that children’s experiences were worse than mothers’ perceptions. Contrary to interpretations by other researchers (30), it appears that among the present sample, mother buffering may not fully protect children from the effects of food insecurity.

Overall, there was fair dyadic food security agreement. Prior examination of mother-child dyads living in south Texas colonias revealed slight agreement in the 4-level food-security outcome [κ = 0.13 (P = 0.07)] (31). The lack of observed dyadic agreement leads the authors to argue that children’s food security ought to be assessed independently from parental perceptions in order to obtain an accurate prevalence and gain an improved comprehension of differential energy allocation (as perceived or observed) within households.

The prevalence of mother-reported child food insecurity (58.3–62.5%) among the present sample exceeds 2011 national estimates for Hispanic families in the United States (17.4%) (2), and more closely resemble that of nearby locales in Alton and San Carlos area colonias (64%) (6) and Progreso and La Feria colonias (62%) (5). Such studies demonstrate the alarming rates of child food insecurity among Mexican-origin families living in Texas border colonias.

This research includes several notable strengths. The multilevel analysis relied on repeated measurements using advanced techniques to control for correlation inherent with multiple assessments among dyads who share a common living environment. Furthermore, it considered the perspectives and experiences of children while recognizing that their comprehension of food insecurity exists in a distinct context from adults. Prior research that evaluated food security at more than 1 point in time using change scores revealed that food-insecure adults and children face short- and long-term adverse health effects (32). Yet, such analytic techniques do not account for correlation. To fully appreciate changes in food security, causes, and covariates, researchers ought to use available statistical techniques for modeling longitudinal data that take into account the correlation of repeated measurements and shared environments. An additional strength of this research includes our improved understanding of the true prevalence of child food insecurity among a sample of limited-resource and difficult-to-reach Mexican-origin families living in Texas border colonias. Recognizing food insecurity among this population as a growing public health and nutrition concern is important because Hispanics are expected to represent nearly 30% of the US population by 2050 (33) and because Texas border colonias may represent an archetype for new-immigrant destinations elsewhere in the country (7). Finally, household and child food security surveys used in the present research are standardized and approved for use among Hispanic populations as well as among children (22, 24, 34) and these Spanish-language surveys were administered by promotora researchers with established trust among participants (35).

There are a couple of limitations to this exploratory work that warrant mention. The sample size comprised 48 mother-child dyads, which may limit statistical significance and prevents results from being generalized to other populations. Post hoc sample size estimations encourage at least 291 participants and are based on some assumptions that are subject to change (36). Second, this research surveyed 1 child from each household, and thus cannot provide a complete picture of differential food security among multiple children and adults within a household.

Food-security research is ripe with areas for advancement. Future investigations may involve replication studies or those involving multiple-child households that consider the perspectives and experiences of all children. In addition, researchers may explore whether fixed-effects, random-effects, or mixed-effects models are the most appropriate fit for their longitudinal food- security data.

In conclusion, child food insecurity among Alton and San Carlos area colonias was worse in the summer, as reported by both children and mothers. Nationally, child food insecurity as reported by mothers affected 17.4% of Hispanic families in 2011 (2), yet among the current sample 62.5% of children reported food insecurity during the summer, highlighting the serious conditions faced by these Texas border colonias residents. The findings of the present study contribute to evidence of alarming rates of child food insecurity, a condition linked to adverse academic, social, behavioral, physiologic, and psychological outcomes (8–12) in these and other border locales (5, 6).

By using logistic regression models for multilevel longitudinal data, this report found that child food security improves significantly from summer to school months, with protection during school offered by the SBP and NSLP. However, the SFSP did not do enough to reduce the burden during the summer. It is imperative that summer feeding programs enhance availability, recruitment, participation, and retention rates to ensure that children satisfy energy needs during the summer, which, in turn, may improve food security at the child, adult, and household levels.

Advanced analytic techniques with input of mother and child perspectives and experiences of food insecurity offer researchers a tool with which to accurately assess the prevalence of this condition. With that, policy makers, service providers, and advocates will have increased leverage to bring awareness to and improve federal and state implementation for nutrition programs in order to reduce the burden of child food insecurity.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the promotora researchers (Maria Davila, Thelma Aguillon, Hilda Maldonado, Maria Garza, and Esther Valdez) and the data entry team (Jenny Becker Hutchinson, Kelli Gerard, Leslie Puckett, Garett Sansom, and Ashlie Huelsebusch). J.R.S. designed the research; C.C.N. performed statistical analyses; and C.C.N., J.R.S., and W.R.D. wrote the manuscript and had primary responsibility for final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: NSLP, National School Lunch Program; SBP, School Breakfast Program; SFSP, Summer Food Service Program; CBG, census block group.

Literature Cited

- 1.Coleman-Jensen A, Nord M, Andrews M, Carlson S. Household food security in the United States in 2010. USDA, Economic Research Service; 2011. Report No.: ERR-125. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coleman-Jensen A, Nord M, Andrews M, Carlson S. Household food security in the United States in 2011. USDA, Economic Research Service; 2012. Report No.: ERR-141. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramos IN, May M, Ramos KS. Environmental health training of promotoras in colonias along the Texas-Mexico border. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:568–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharkey JR, Horel S, Han D, Huber JCJ. Association between neighborhood need and spatial access to food stores and fast food restaurants in neighborhoods of colonias. Int J Health Geogr. 2009;8:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharkey JR, Dean WR, Johnson CM. Association of household and community characteristics with adult and child food insecurity among Mexican-origin households in colonias along the Texas-Mexico border. Int J Equity Health. 2011;10:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharkey JR, Nalty C, Johnson C, Dean WR. Children's very low food security is associated with increased dietary intakes in energy, fat, and added sugar among Mexican-origin children (6–11 y) in Texas border colonias. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esparza AX, Donelson AJ. The colonias reader: economy, housing, and public health in U.S -Mexico. Tucson (AZ): The University of Arizona Press; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stuff JE, Casey PH, Szeto KL, Gossett JM, Robbins JM, Simpson PM, Connell C, Bogle ML. Household food insecurity is associated with adult health status. J Nutr. 2004;134:2330–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casey PH, Szeto KL, Robbins JM, Stuff JE, Connell C, Gossett JM, Simpson PM. Child health-related quality of life and household food security. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:51–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams EJ, Grummer-Strawn L, Chavez G. Food insecurity is associated with increased risk of obesity in California women. J Nutr. 2003;133:1070–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basiotis PP, Lino M. Food insufficiency and prevalence of overweight among adult women. Family Econ. Nutrition Rev. 2003;15:55–7 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alaimo K, Olson CM, Frongillo EA., Jr Food insufficiency and American school-aged children's cognitive, academic, and psychosocial development. Am Acad Pediatrics. 2001;108:44–53 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaiser LL, Melgar-Quinonez HR, Lamp CL, John MC, Sutherlin JM, Harwood JO. Food security and nutritional outcomes of preschool-age Mexican-American children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:924–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook JT, Frank DA, Casey PH, Rose-Jacobs R, Black MM, Chilton M, de Cuba SE, Appugliese D, Coleman S, Heeren T, et al. A brief indicator of household energy security: associations with food security, child health, and child development in US infants and toddlers. Am Acad Pediatrics. 2008;122:e867–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosas LG, Harley K, Fernald LCH, Guendelman SM F, Neufeld LM, Eskenazi B. Dietary associations of household food insecurity among children of Mexican descent: results of a binational study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:2001–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nord M, Bickel G. Estimating the prevalence of children's hunger from the current population survey food security supplement. The Second Food Security Measurement and Research Conference; 1999 Feb 23-4; Washington (DC): USDA Economic Research Service; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Booker CL, Unger JB, Azen SP, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Lickel B, Johnson CA. A longitudinal analysis of stressful life events, smoking behaviors, and gender differences in a multicultural sample of adolescents. Subst Use Misuse. 2008;43:1521–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jyoti DF, Frongillo EA, Jones SJ. Food insecurity affects school children's academic performance, weight gain, and social skills. J Nutr. 2005;135:2831–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nord M, Romig K. Hunger in the summer: seasonal food insecurity and the National School Lunch and Summer Food Service programs. J Child Poverty. 2006;12:141–58 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Food Resource and Action Center. Hunger doesnapost take a vacation: summer nutrition status report 2012 [cited 2012 Aug 28]. Available from: http://frac.org/pdf/2012_summer_nutrition_report.pdf.

- 21.Fram MS, Frongillo EA, Jones SJ, Williams RC, Burke MP, DeLoach KP, Blake CE. Children are aware of food insecurity and take responsibility for managing food resources. J Nutr. 2011;141:1114–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Connell CL, Lofton KL, Yadrick K, Rehner TA. Children’s experiences of food insecurity can assist in understanding its effect on their well-being. J Nutr. 2005;135:1683–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. US Census Bureau. State and county quickfacts—Alton (city), Texas [homepage on the Internet] [cited 2012 Nov 5].Available from: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/48/4802212.html.

- 24.Pérez-Escamilla R, Segall-Correa AM, Kurdian Maranha L, Sampaio F, Marin-Leon L, Panigassi G. An adapted version of the U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Insecurity Module is a valid tool for assessing household food insecurity in Campinas, Brazil. J Nutr. 2004;134:1923–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.USDA Economic Research Service Self-administered food security survey module for children ages 12 years and older. 2006 [homepage on the Internet] [cited 2012 Nov 5]. Available from: http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/survey-tools.aspx

- 26.USDA Economic Research Service U.S. household food security survey module: three-stage design, with screeners [homepage on the Internet] [cited 2012 Nov 5]. Available from: http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/survey-tools.aspx

- 27.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–74 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gleason P, Suitor C. Children’s diets in the mid-1990s: dietary intake and its relationship with school meal participation. Report submitted to the U.S. department of agriculture, food and nutrition service. Princeton (NJ): Mathematica Policy Research; 2001. Report No.: CN-01-CD1.

- 29.National Summer Learning Association. Federal funding for meals during the summer [homepage on the Internet] [cited 2012 Aug 21]. Available from: http://www.summerlearning.org/resource/resmgr/wellness/wellness_resources_in_brief.pdf.

- 30.Cook JT, Frank DA, Berkowitz C, Black MM, Casey PH, Cutts DB, Meyers AF, Zaldivar N, Skalicky A, Levenson S, et al. Food insecurity is associated with adverse health outcomes among human infants and toddlers. J Nutr. 2004;134:1432–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nalty CC, Sharkey JR, Dean WR. Children's reporting of food insecurity in predominately food insecure households in Texas border colonias. Nutr J. 2013;12:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whitaker RC, Sarin A. Change in food security status and change in weight are not associated in urban women with preschool children. J Nutr. 2007;137:2134–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pew Research Hispanic Center. U.S. population projections, 2005–2050 [homepage on the Internet] [cited 2012 Nov 5]. Available from: http://www.pewhispanic.org/2008/02/11/us-population-projections-2005–2050/

- 34.Connell CL, Nord M, Lofton KL, Yadrick K. Food security of older children can be assessed using a standardized survey instrument. J Nutr. 2004;134:2566–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.St John JA, Johnson CM, Sharkey JR, Dean WR, Arandia G. Empowerment: evolution of promotoras as promotora-researchers in the Comidas Saludables & Gente Sana en las Colonias del Sur de Tejas (Healthy Food and Healthy People in South Texas Colonias). Program J Prim Prev.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Twisk JWR. Applied longitudinal data analysis for epidemiology. Cambridge (UK): The University of Cambridge; 2003. [Google Scholar]