Abstract

Objective

To investigate adverse events attributed to traditional medical treatments in the Republic of Korea.

Methods

Adverse events recorded in the Republic of Korea between 1999 and 2010 – by the Food and Drug Administration, the Consumer Agency or the Association of Traditional Korean Medicine – were reviewed. Records of adverse events attributed to the use of traditional medical practices, including reports of medicinal accidents and consumers’ complaints, were investigated.

Findings

Overall, 9624 records of adverse events attributed to traditional medical practices – including 522 linked to herbal treatments – were identified. Liver problems were the most frequently reported adverse events. Only eight of the adverse events were recorded by the pharmacovigilance system run by the Food and Drug Administration. Of the 9624 events, 1389 – mostly infections, cases of pneumothorax and burns – were linked to physical therapy (n = 285) or acupuncture/moxibustion (n = 1104).

Conclusion

In the Republic of Korea, traditional medical practices often appear to have adverse effects, yet almost all of the adverse events attributed to such practices between 1999 and 2010 were missed by the national pharmacovigilance system. The Consumer Agency and the Association of Traditional Korean Medicine should be included in the national pharmacovigilance system.

Résumé

Objectif

Étudier les effets indésirables attribués aux traitements médicaux traditionnels en République de Corée.

Méthodes

On a examiné les effets indésirables enregistrés en République de Corée entre 1999 et 2010 par la FDA, l'Agence de protection du consommateur ou l'Association de médecine traditionnelle coréenne. On a également étudié les dossiers sur les effets indésirables attribués aux pratiques médicales traditionnelles, y compris les rapports d'accidents médicinaux et les réclamations de consommateurs.

Résultats

Dans l'ensemble, 9624 dossiers d'effets indésirables attribués à des pratiques médicales traditionnelles, dont 522 liés à des traitements à base de plantes, ont été identifiés. Les problèmes de foie sont les effets indésirables les plus fréquemment rapportés. Seulement huit des effets indésirables ont été enregistrés par le système de pharmacovigilance géré par la FDA. Sur les 9624 effets, 1389 (principalement des infections, des cas de pneumothorax et des brûlures) étaient liés à la thérapie physique (n=285) ou à l'acupuncture/moxibustion (n=1104).

Conclusion

En République de Corée, les pratiques médicales traditionnelles semblent souvent avoir des effets indésirables, mais presque tous les effets indésirables attribués à ces pratiques entre 1999 et 2010 n'ont pas été décelés par le système national de pharmacovigilance. L'Agence de protection du consommateur et l'Association de médecine traditionnelle coréenne devraient être incluses dans le système national de pharmacovigilance.

Resumen

Objetivo

Investigar las reacciones adversas atribuidas a los tratamientos médicos tradicionales en la República de Corea.

Métodos

Se analizaron las reacciones adversas registradas en la República de Corea entre 1999 y 2010 por la Administración de Alimentos y Medicamentos, la Agencia de Consumo y la Asociación de Medicina Tradicional Coreana. Se investigaron los registros de reacciones adversas atribuidas al empleo de prácticas médicas tradicionales, incluidos los informes de accidentes médicos y las quejas de los consumidores.

Resultados

En total, se identificaron 9624 casos de reacciones adversas atribuidas a las prácticas médicas tradicionales, entre ellos, 522 vinculados a los tratamientos a base de hierbas. Las reacciones adversas registradas con mayor frecuencia fueron los problemas hepáticos. El sistema de farmacovigilancia, dirigido por la Administración de Alimentos y Medicamentos, solo registró ocho reacciones adversas. De las 9624 reacciones, 1389 (en su mayoría infecciones, casos de neumotórax y quemaduras) estuvieron relacionadas con la terapia física (n= 285) o la acupuntura/moxibustión (n = 1104).

Conclusión

En la República de Corea, las prácticas médicas tradicionales a menudo parecen provocar reacciones adversas. Sin embargo, el sistema nacional de farmacovigilancia pasó por alto casi todas las reacciones adversas atribuidas a este tipo de prácticas entre 1999 y 2010. Es necesario incluir la Agencia de Consumo y la Asociación de Medicina Tradicional Coreana en el sistema nacional de farmacovigilancia.

ملخص

الغرض

تحري الأحداث الضائرة التي تُعزى إلى العلاجات الطبية التقليدية في جمهورية كوريا.

الطريقة

تم استعراض الأحداث الضائرة المسجلة في جمهورية كوريا في الفترة من 1999 إلى 2010 – من جانب إدارة الأغذية والأدوية أو هيئة المستهلكين أو اتحاد الطب التقليدي الكوري. وتم فحص سجلات الأحداث الضائرة التي تُعزى إلى استخدام الممارسات الطبية التقليدية، بما في ذلك تقارير الحوادث الدوائية وشكاوى المستهلكين.

النتائج

بشكل عام، تم تحديد 9624 سجلاً للأحداث الضائرة التي تُعزى إلى الممارسات الطبية التقليدية – بما في ذلك 522 سجلاً مرتبطاً بعلاجات الأعشاب. وكانت مشكلات الكبد أكثر الأحداث الضائرة المبلغ عنها من حيث معدل التكرار. وتم تسجيل ثمانية أحداث ضائرة فقط من خلال نظام التيقظ الصيدلاني الذي تديره إدارة الأغذية والأدوية. ومن بين 9624 حدثاً، ارتبط 1389 حدثاً – معظمها عدوى، وحالات من الاسترواح الصدري وحروق – بالعلاج الطبيعي (العدد = 285) أو الوخز الإبري/كي الجلد (العدد = 1104).

الاستنتاج

في جمهورية كوريا، عادة ما تظهر آثار ضائرة للممارسات الطبية التقليدية، رغم عدم تمكن نظام التيقظ الصيدلاني الوطني تقريباً من تسجيل جميع الأحداث الضائرة التي تُعزى إلى هذه الممارسات في الفترة من 1999 إلى 2010. وينبغي إدراج هيئة المستهلكين واتحاد الطب التقليدي الكوري في نظام التيقظ الصيدلاني.

摘要

目的

调查涉嫌由韩国传统医学治疗引起的不良事件。

方法

对韩国在1999 年至2010 年之间由食品和药物管理局、消费者保护机构或韩国传统医学协会记录的不良事件进行了评价。对涉嫌因传统韩医行医引起的不良事件记录(包括药物事故和消费者投诉报告)进行了调查。

结果

总体而言,确定了9624 条涉嫌因传统行医方法引起的不良事件记录(包括522 例与草药治疗相关的记录)。肝脏问题是最常见诸报告的不良事件。不良事件中,由食品和药物管理局负责运转的药物警戒系统只记录到8 次。在9624 次事件中,1389 次(多数为感染、气胸和烧伤)与物理治疗(n=285)或针灸/艾灸(n=1104)相关。

结论

在韩国,传统医学疗法看来经常出现负面影响,但是在1999 年至2010 年之间,几乎所有指向这种疗法的不良事件都没有被国家药物警戒系统记录。国家药物警戒系统应将消费者保护机构和韩国传统医学协会包含在内。

Резюме

Цель

Исследовать неблагоприятные явления, связанные с использованием методов народной медицины в Республике Корея.

Методы

Был проведен обзор неблагоприятных явлений, зарегистрированных в Республике Корея в период между 1999 и 2010 годами Управлением по санитарному надзору за качеством пищевых продуктов и медикаментов, Агентством по защите потребителей и Ассоциацией народной корейской медицины. Были подробно изучены отчеты о неблагоприятных явлениях, связанных с использованием народных методов лечения, включая отчеты о несчастных случаях медицинского характера и жалобы потребителей.

Результаты

Всего было выявлено 9624 записи о неблагоприятных явлениях, связанных с использованием методов народной медицины, в том числе 522 записи, касающиеся лечения травами. Чаще всего сообщается о таких неблагоприятных явлениях, как проблемы с печенью. Только восемь побочных эффектов были зарегистрированы системой фармакологического надзора, которой руководит Управление по санитарному надзору за качеством пищевых продуктов и медикаментов. Их 9624 записей в 1389 случаях, касающихся в основном инфекционных заболеваний, случаев пневмоторакса и ожогов, проблемы были связаны с физиотерапией (n = 285) или акупунктурой/моксотерапией (n = 1104).

Вывод

Использование методов народной медицины в Республике Корея часто приводит к возникновению неблагоприятных явлений, но почти все нежелательные последствия, связанные с такими методами, в период с 1999 по 2010 год не привлекли внимания национальной системы фармакологического надзора. Агентство по защите потребителей и Ассоциация народной корейской медицины должны быть включены в структуру национальной системы фармакологического надзора.

Introduction

In many countries, medical practices that are categorized as traditional, complementary and/or alternative are common and the focus of current advocacy.1 In 2008, for example, most of the people who lived in Australia (68.9%), China (90%), the Republic of Korea (86%), Malaysia (55.6%) and Singapore (53%) used some form of traditional medicine.2,3 Although some traditional medical practices appear beneficial, many remain untested and there is little relevant monitoring or control. Our knowledge of the adverse effects of such practices is therefore very limited. This hampers the identification of the safest and most effective traditional practices and medicines.1

The adverse effects linked to traditional Korean medicine – as practised in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea and the Republic of Korea – have never been carefully monitored. In 1985, the government of the Republic of Korea passed Ministry of Health and Society Law 85–64, which promoted the development of a national system of pharmacovigilance for tracking adverse drug reactions. Three years later, the Korean Food and Drug Administration established a national system for the voluntary reporting of adverse reactions to drugs and herbal medicines that is currently based on 20 regional pharmacovigilance centres.4,5 Since then, however, very few adverse events attributed to herbal medicines have been recorded by this system. The aim of the present study was to estimate the true incidence of such events in the Republic of Korea, using data from the Food and Drug Administration, another governmental agency (the Consumer Agency) and a nongovernmental organization (the Association of Traditional Korean Medicine).

Methods

Publications2–4,6–15 were used to determine the main forms of traditional medicine in use in the Republic of Korea and the corresponding usage rates, as percentages of the national population. Attempts were also made to identify records of any adverse events that occurred in the Republic of Korea between 1999 and 2010 and were attributed to any traditional medical practice. The relevant, published records of the Food and Drug Administration, the Consumer Agency and the Association of Traditional Korean Medicine were surveyed (see Results section of this paper). The Consumer Agency has received and investigated complaints about consumer goods, consumer services, medical services and drugs since 1999. It publishes summary data on adverse events every three years. The members of the Association of Traditional Korean Medicine are all practitioners of traditional medicine. Since 1999, this association has recorded adverse events that appear to be linked to traditional medical practices financed by health insurance companies. Although the association has generally published summary data on such adverse events every three years, it has not published any records for the adverse events it recorded between 2002 and 2004.

Results

Usage of traditional Korean medicine

Traditional Korean medicine includes herbal medicine, acupuncture, moxibustion, cupping therapy and “physical therapies” such as hot pack applications, massage, chiropractic manipulation and infrared irradiation.2,6 In a survey conducted in 2008,7 it was estimated that 86% of the people living in the Republic of Korea had used some form of traditional Korean medicine at least once and that 45.8% had used such medicine in the previous 12 months. However, only 7.2% had ever visited a traditional medicine clinic. Among the people who had received traditional Korean medical treatments, 53.4% had received them for diseases of the musculoskeletal system or connective tissue. The traditional Korean medical treatments received were acupuncture (70.6% of the people who had ever received traditional Korean medicine), a crude herbal formulation (20.8%), physical therapy (4.9%), a refined herbal product (1.3%), cupping therapy (0.9%) and moxibustion (0.6%).7

In 1999 – according to the records of the Republic of Korea’s national health insurance scheme8 – 11 345 practitioners of traditional medicine prescribed or treated patients in 35 877 000 consultations in 6972 traditional medicine clinics in the Republic of Korea. The corresponding values for 2010 – 19 065, 94 634 854 and 12 229, respectively9 – were markedly higher. Currently, acupuncture, moxibustion, cupping therapy, 56 prescription-only herbal medicines, 68 other kinds of herbal medicines and three forms of physical therapy are covered by the national health insurance scheme in the Republic of Korea.2 By 2008, the country’s Food and Drug Administration had licensed 547 crude herbal medicines, all of which were listed in the Korean Pharmacopoeia (n = 165) or the Korean Herbal Pharmacopoeia (n = 382).10,11

There appear to be very few published case reports relating to the adverse effects of traditional Korean medical treatments. In the Republic of Korea in 1979, one boy presented with lead poisoning and another with acute lead encephalopathy; both boys had ingested the same herbal medicine daily for 2 months.12 In the same country in 2006, a problem with sensitivity was reported to have resulted from acupuncture.13 Overall, 1.8%, 2.7% and 12% of the people interviewed in the Republic of Korea in 2005, 2006 and 2007, respectively, reported that they had suffered an adverse event that they associated with some form of traditional Korean medicine.14,15 In government-run surveys conducted in the Republic of Korea in 2008 and 2011, herbal medicines accounted for 8.2% and 3.7% of the adverse events attributed to all forms of traditional Korean medicine, respectively.3,7

Food and Drug Administration

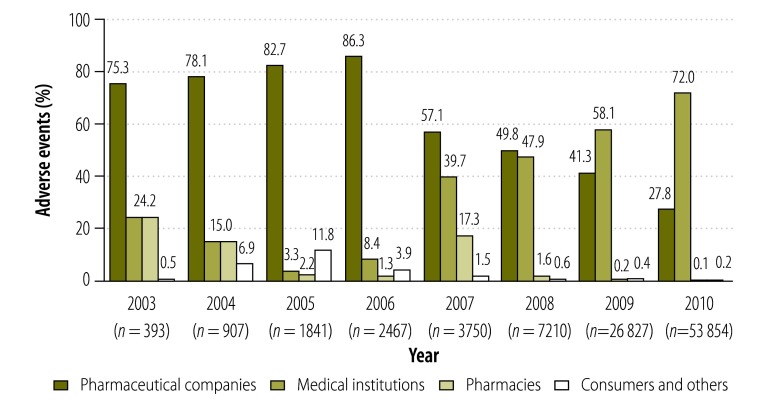

As part of the national system of pharmacovigilance, the Republic of Korea’s Food and Drug Administration collects data on adverse events from pharmaceutical companies, health-care providers, pharmacies and consumers. Only five adverse drug reactions were recorded by the Administration in 1988 but the number of such adverse events recorded each year has since grown, from 148–637 between 1999 and 2002 to 53 854 in 2010.4,16–18

Between 2003 and 2010, the proportion of adverse drug reactions reported to the Administration by pharmaceutical companies decreased from 75.3% to 27.8%, whereas the proportion reported by medical institutions increased from 24.2% to 72.0%. Over the same period, only a few adverse drug reactions were reported to the Administration by pharmacies and consumers (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Drug-related adverse events reported to the Food and Drug Administration, Republic of Korea, 2003–2010

Note: The graph shows the percentages of adverse events related to all drugs – not just Korean traditional drugs – reported in any given year.

Only eight of the 95 449 adverse drug reactions reported to the Administration between 1999 and 2010 – one of those reported in 2007 and seven of those reported in 2008 – were attributed to herbal medicines. All eight were reported by medical institutions.19,20

Consumer Agency

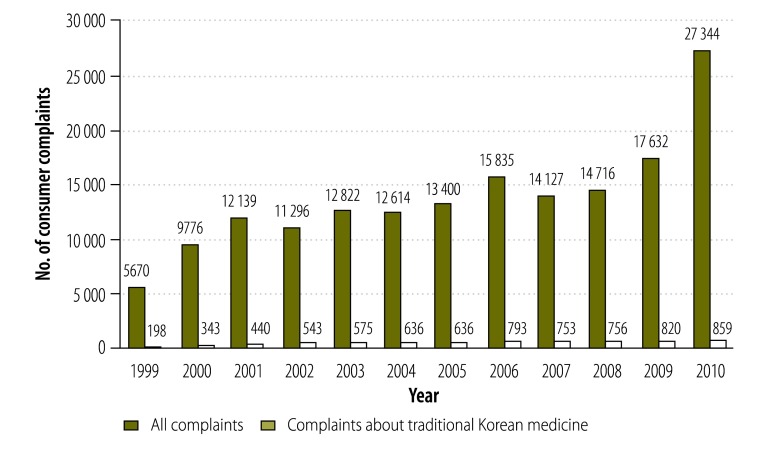

Between 1999 and 2010, the Republic of Korea’s Consumer Agency received 167 371 complaints – from consumers – about drugs and other medical treatments in general, including 7532 (4.5%) relating to herbal medicines or other forms of traditional Korean medicine. Over the same period, the average annual number of complaints about drugs and other medical treatments increased from 5670 to 27 344, and the average annual number of complaints relating to herbal medicines or other forms of traditional Korean medicine increased from 198 to 859 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Total consumer complaints and consumer complaints related to traditional Korean medical practices, Republic of Korea, 1999–2010

Data obtained from the Republic of Korea’s Consumer Agency.

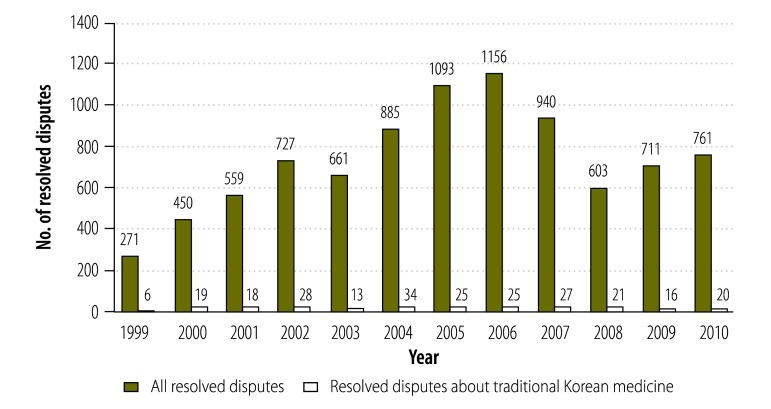

The staff of the Consumer Agency attempt to resolve the complaints they receive through communication with – and arbitration between – the relevant medical or pharmaceutical suppliers and the complainants. However, if the complaint remains unresolved, it is passed to the members of the Consumer Dispute Settlement Commission. Of the 8844 disputes that the members of this commission resolved between 1999 and 2010, 252 (2.8%) were related to traditional Korean medicine (Fig. 3). Over the same period, the percentage of each year’s resolved disputes that were related to traditional Korean medicine – 2.2% (6 of 271) in 1999 and 2.6% (20 of 761) in 2010 – showed little variation.

Fig. 3.

Disputes resolved by the Consumer Dispute Settlement Commission, in total and related to traditional Korean medical practices, Republic of Korea, 1999–2010

Note: The graph shows the numbers of disputes resolved following complaints made to the national Consumer Agency.

Between 1999 and 2010, the Consumer Agency recorded sufficient details for 190 complaints relating to traditional Korean medicine to be categorized. These 190 complaints were related to the use of herbal medicines (52.6%), acupuncture/moxibustion (31.1%), physical therapy (9.5%) and other treatments (6.8%). They included 69 cases of worsening symptoms after treatment (36.3%), 47 cases of adverse reactions to herbal medicine (24.7%), 31 cases of apparently ineffective treatment (16.3%), 18 cases of infection (9.5%), five cases of burns (2.6%), four fatalities (2.1%), two cases of pneumothorax (1.1%) and 14 “other” cases. About half (46.8%) of the 47 adverse reactions to herbal medicines involved hepatitis. The herbal medicines associated with hepatitis came from Ephedra sinica, Erigeron canadensis, Pinellia ternata, Xanthium strumarium, Evodia rutaecarpa, Prunus armeniaca, Prunus persica and Sinomenium acutum. Although the causes of the four fatalities were not recorded, acupuncture/moxibustion and cupping therapy were associated with most of the other more serious problems, which included infections, the exacerbation of symptoms, pneumothorax and burns. Of the adverse events reported to the Consumer Agency that were linked to traditional Korean medicine, more than 40% were infections attributed to the mismanagement of acupuncture or cupping therapy.

Over 50% of the adverse events associated with herbal medicines were caused either by misdiagnosis – which often led to the exacerbation of symptoms despite treatment – or by toxic ingredients.

Association of Traditional Korean Medicine

Between 1999 and 2010, the Association published the details of 2246 complaints that had been reported to health insurance companies and attributed to traditional Korean medicine: 330 between 1999 and 2001, 768 between 2005 and 2007 and 1116 between 2008 and 2010. Almost half (46.2%) of these complaints were related to acupuncture/moxibustion. The rest were related to crude herbal formulations (18.3%), physical therapies (11.8%) and “other causes” (i.e. misdiagnoses and injuries from falls; 23.7%). Complaints relating to crude herbal formulations, acupuncture and “other causes” increased over the study period, whereas complaints related to physical therapies decreased (Table 1).

Table 1. Numbers of adverse events attributed to various types of traditional Korean medical practices, Republic of Korea, 1999–2010.

| Practice | No. of events |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1999–2001 | 2005–2007 | 2008–2010 | |

| Acupuncture/moxibustion | 156 | 292 | 597 |

| Herbal medicine | 69 | 157 | 188 |

| Physical therapy | 59 | 151 | 57 |

| Other treatment | 46 | 168 | 324 |

| All treatments | 330 | 768 | 1166 |

Data obtained from the Association of Traditional Korean Medicine.

The data published by the Association allow the adverse events related to each form of traditional Korean medicine to be identified for just two years within the present study period: 2006 and 2009 (Table 2). For these two years, the adverse event most frequently associated with acupuncture was inflammation, followed by pneumothorax and nerve damage. Minor adverse events reported for these years included skin discoloration, haematoma and a herniated disc. The more serious adverse events reported were the exacerbation of symptoms, termination of pregnancy, oedema, respiratory problems, cerebral infarction and death (one case). The adverse event most commonly associated with moxibustion was a burn. Burns were also reported following infrared irradiation and hot wax therapy. The adverse events most commonly attributed to herbal medicines were hepatitis and hepatosis, followed by stomach ache, vomiting and adverse skin reactions. Of all of the adverse events recorded, 538 were either other injuries that occurred during acupuncture, cupping or physical therapies or the exacerbation of symptoms following misdiagnosis (Table 2) – often the misdiagnosis of a torn muscle ligament as a simple sprain.

Table 2. Per cent distribution of adverse events attributed to various types of traditional Korean medical practices, Republic of Korea, 2006 and 2009.

| Adverse event | Percentage of total events |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acupuncture |

Moxibustion |

Herbal medicine |

Other treatment |

||||||||

| 2006 | 2009 | 2006 | 2009 | 2006 | 2009 | 2006 | 2009 | ||||

| Infection | 47.7 | 38.4 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| Pneumothorax | 16.9 | 13.5 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| Nerve injury | 10.8 | 9.0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| Burn | – | – | 58.0 | 96.2 | – | – | – | – | |||

| Hepatitis | – | – | – | – | 50.0 | 55.1 | – | – | |||

| Hepatosis | – | – | – | – | 8.8 | 3.8 | – | – | |||

| Injury from fall | – | – | – | – | – | – | 66.6 | 88.0 | |||

| Other | 24.6 | 39.1 | 42.0 | 3.8 | 41.2 | 41.1 | 33.4 | 12.0 | |||

Data obtained from the Association of Traditional Korean Medicine.

Discussion

The adverse events associated with traditional Korean medicine are caused either by herbal medicines or by traditional practices such as acupuncture, moxibustion, cupping and physical therapies. Since 2002, when the World Health Organization (WHO) included herbal medicines in its pharmacovigilance scheme,21 each of WHO’s Member States has monitored the use of traditional herbal medicines. In the Republic of Korea, this monitoring is largely based on a national system for detecting adverse reactions to drugs. However, this system, which is run by the Food and Drug Administration, has recorded very few adverse events related to herbal medicines, even though such medicines are commonly used throughout the Republic of Korea.2,7 In China in 2010, in contrast, 95 620 adverse events – including 13 420 severe adverse reactions – were linked to the use of traditional herbal medicines.2,22 It seems clear that the Food and Drug Administration in the Republic of Korea is failing to record most of the adverse events linked to the use of herbal medicine in the country. Between 1999 and 2010, 9624 adverse events linked to the use of traditional Korean medicine were recorded in the Republic of Korea: 7352 by the Consumer Agency, 2264 by the Association of Traditional Korean Medicine and just 8 by the national Food and Drug Administration. Overall, 522 of these events – 100 of those reported to the Consumer Agency, 414 of those reported to the Association of Traditional Korean Medicine and all 8 of those reported to the Food and Drug Administration – were associated with herbal medicines.

The Food and Drug Administration is the Republic of Korea’s “responsible agency” at the Üppsala Monitoring Centre – a WHO collaborating centre for international drug monitoring. Although the Administration appears to have sufficient capabilities for collecting spontaneous reports and for data mining in global pharmacovigilance,5,23 its collection of data on adverse events related to the use of herbal medicines seems poor.

There are at least four reasons why the Administration records so few problems with herbal medicines. First, many of the adverse events recorded by the Administration – 41.3% and 27.8% of those recorded in 2009 and 2010, respectively – are reported by pharmaceutical companies. In 2009, herbal products accounted for just 1.15% of total pharmaceutical production and just 1.3% of the medications prescribed by medical practices or traditional medicine clinics.3,7,24 In 2010, such products accounted for just 0.9% of the health insurance benefits used to pay for traditional Korean medicine.9 The pharmaceutical companies tend to concentrate on non-herbal drugs and, in consequence, report very few adverse effects of herbal formulations.

Second, the 20 medical institutions that form the main source of the reports of adverse events collected by the Food and Drug Administration are all hospitals that only prescribe non-herbal medicines. Most of the institutions that focus on traditional Korean medicine do not currently contribute to the national official pharmacovigilance scheme.

Third, although institutions that focus on traditional Korean medicine can report adverse events to the Food and Drug Administration, most report such events only to the Association of Traditional Korean Medicine. Data collected by the Association are rarely passed on to the Food and Drug Administration.25

Fourth, the consumers of herbal medicines in the Republic of Korea tend to complain about adverse events to the national Consumer Agency and their complaints are seldom passed on to the Food and Drug Administration.

Currently, the national pharmacovigilance system in China involves more regional centres than the corresponding system in the Republic of Korea (34 versus 20).5,22 The Food and Drug Administrations in China and the Republic of Korea – like the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency in Japan – are supposed to collect reports of adverse events related to all medicines, including herbal ones.26,27 India, however, has a pharmacovigilance system dedicated to the investigation of traditional ayurvedic drugs. At present, this system is based on eight regional and 30 peripheral centres for pharmacovigilance.28,29 China and the Republic of Korea have not found it necessary to develop such an independent and professional pharmacovigilance system for herbal medicine, presumably because their policy-makers believe that one national system should be able to cover both herbal and non-herbal medicines.

The adverse events linked to the use of traditional Chinese medicines are often idiosyncratic reactions that include allergy, hepatitis, anaphylaxis or liver damage.30,31 Liver problems were found to be the adverse events that were most frequently linked to the use of herbal medicines in the Republic of Korea (present study) and are – globally – the adverse events that are most frequently associated with herbal medicines.32

Like herbal medicines, acupuncture appears to cause many adverse events in the Republic of Korea. Acupuncture is, however, also one of the most common traditional medical practices in the country, and is the treatment that is generally sought for diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissues. In the Republic of Korea, the adverse events associated with acupuncture – with or without moxibustion –were mostly infections, burns and pneumothorax, although nerve damage, skin discoloration, haematoma, a herniated disc and death were also reported. In China, similarly, acupuncture has been associated with pneumothorax, fainting, subarachnoid haemorrhage, infection and death.33 The Republic of Korea’s pharmacovigilance system is not designed to detect the adverse effects of acupuncture – or those of cupping or physical therapies.

Conclusion

Although herbal medicines are associated with many adverse events in the Republic of Korea, very few of these events are recorded by the national system of pharmacovigilance. If adequate protection and advice are to be given to consumers, the underreporting of such events should be addressed as a matter of urgency.

Funding:

This research was supported by the Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine via the Evidence-based Medicine for Herbal Formulae programme (grant K12031). MSL was supported by the same institute (grants K13281 and K13400).

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.WHO traditional medicine strategy, 2002–2005 Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2002/who_edm_trm_2002.1.pdf [accessed 15 May 2013].

- 2.The regional strategy for traditional medicine in the Western Pacific (2011–2020) Manila: World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Western Pacific; 2002. Available from: http://www.wpro.who.int/publications/2012/regionalstrategyfortraditionalmedicine_2012.pdf [accessed 15 May 2013].

- 3.A survey on the use of traditional Korean medicine and herbal medicine Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2011. Korean. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park BJ. Rationale for developing active drug reaction surveillance system in Korea. J Korean Soc Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1994;2:105–11. Korean. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kimura T, Matsushita Y, Yang YH, Choi NK, Park BJ. Pharmacovigilance systems and databases in Korea, Japan, and Taiwan. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20:1237–45. doi: 10.1002/pds.2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung F. TCM: made in China. Nature. 2011;480:S82–3. doi: 10.1038/480S82a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.A survey on the use of traditional Korean medicine, 2008 Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2009. Korean. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National health insurance statistical yearbook, 1999 Seoul: National Health Insurance Corporation; 2000. Korean. [Google Scholar]

- 9.National health insurance statistical yearbook, 2010 Seoul: Health Insurance Review Agency; 2011. Korean. [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Korean pharmacopoeia. 9th ed. Seoul: Food and Drug Administration; 2008. Korean. [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Korean herbal pharmacopoeia Seoul: Food and Drug Administration; 2007. Korean. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ha SY, Kang KW. Two cases of lead poisoning after taking herb pills. J Korean Pediatr Soc. 1979;22:64–70. Korean. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim Y, Kim Y, Lee H. The clinical study on 6 cases of patients with side effect caused by acupuncture therapy. J Daejeon Univ Tradit Korean Med Inst. 2006;15:47–52. Korean. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JT. Research on intake of Chinese medicine by Koreans Seoul: Food and Drug Administration; 2007. Korean. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee SD. The study for activation and development of herbal adverse reaction reporting system Seoul: Food and Drug Administration; 2007. Korean. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim JY, Ha JH, Kim BR, Jang J, Hwang M, Park HJ, et al. Analysis of characteristics about spontaneous reporting – reported in 2008. J Korean Soc Pharmacoepidemiol Risk Manag. 2010;3:23–31. Korean. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Food and drug statistical yearbook 2011 Seoul: Food and Drug Administration; 2012. Korean. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ha JH, Rhou MK, Kim YH, Na HS, Shin HJ, Park HJ. Analysis of adverse event reports received in KFDA for 2009. J Korean Soc Pharmacoepidemiol Risk Manag. 2010;3:128–36. Korean. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shin YS, Lee YW, Choi YH, Park B, Jee YK, Choi SK, et al. Spontaneous reporting of adverse drug events by Korean regional pharmacovigilance centers. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18:910–5. doi: 10.1002/pds.1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwon H, Lee SH, Kim SE, Lee JH, Jee YK, Kang HR, et al. Spontaneously reported hepatic adverse drug events in Korea: multicenter study. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27:268–73. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2012.27.3.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The importance of pharmacovigilance – safety monitoring of medicinal products Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js4893e/ [accessed 15 May 2013].

- 22.Zhang L, Yan J, Liu X, Ye Z, Yang X, Meyboom R, et al. Pharmacovigilance practice and risk control of traditional Chinese medicine drugs in China: current status and future perspective. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;140:519–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Üppsala Monitoring Centre [Internet]. WHO programme members. Countries participating in the WHO Programme for International Drug Monitoring, with year of joining. Üppsala: ÜMC; 2013. Available from: http://www.who-umc.org/DynPage.aspx?id=100653&mn1=7347&mn2 =7252&mn3=7322&mn4=7442 [accessed 15 May 2013].

- 24.Second 5-year comprehensive plan to foster and develop Korean traditional medicine (2011–2015) Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2010. Korean. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaw D, Graeme L, Pierre D, Elizabeth W, Kelvin C. Pharmacovigilance of herbal medicine. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;140:513–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park HL, Lee HS, Shin BC, Liu JP, Shang Q, Yamashita H, et al. Traditional medicine in China, Korea, and Japan: a brief introduction and comparison. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:429103. doi: 10.1155/2012/429103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Du W, Guo JJ, Jing Y, Li X, Kelton CM. Drug safety surveillance in China and other countries: a review and comparison. Value Health. 2008;11(Suppl 1):S130–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00377.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chaudhary A, Singh N, Kumar N. Pharmacovigilance: boon for the safety and efficacy of ayurvedic formulations. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2010;1:251–6. doi: 10.4103/0975-9476.74427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baghel M. The national pharmacovigilance program for Ayurveda, Siddha and Unani drugs: current status. Int J Ayurveda Res. 2010;1:197–8. doi: 10.4103/0974-7788.76779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zeng ZP, Jiang JG. Analysis of the adverse reactions induced by natural product-derived drugs. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;159:1374–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00645.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ko RJ. A U.S. perspective on the adverse reactions from traditional Chinese medicines. J Chin Med Assoc. 2004;67:109–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Üppsala Monitoring Centre [Internet]. Classification and monitoring safety of herbal medicines. Üppsala: ÜMC; 2011. Available from: http://www.who-umc.org/graphics/24727.pdf [accessed 15 May 2013].

- 33.Zhang J, Shang H, Gao X, Ernst E. Acupuncture-related adverse events: a systematic review of the Chinese literature. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:915–921C. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.076737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]