Abstract

Unless the concept is clearly understood, “universal coverage” (or universal health coverage, UHC) can be used to justify practically any health financing reform or scheme. This paper unpacks the definition of health financing for universal coverage as used in the World Health Organization’s World health report 2010 to show how UHC embodies specific health system goals and intermediate objectives and, broadly, how health financing reforms can influence these.

All countries seek to improve equity in the use of health services, service quality and financial protection for their populations. Hence, the pursuit of UHC is relevant to every country. Health financing policy is an integral part of efforts to move towards UHC, but for health financing policy to be aligned with the pursuit of UHC, health system reforms need to be aimed explicitly at improving coverage and the intermediate objectives linked to it, namely, efficiency, equity in health resource distribution and transparency and accountability.

The unit of analysis for goals and objectives must be the population and health system as a whole. What matters is not how a particular financing scheme affects its individual members, but rather, how it influences progress towards UHC at the population level. Concern only with specific schemes is incompatible with a universal coverage approach and may even undermine UHC, particularly in terms of equity. Conversely, if a scheme is fully oriented towards system-level goals and objectives, it can further progress towards UHC. Policy and policy analysis need to shift from the scheme to the system level.

Résumé

Si le concept est correctement défini, la «couverture universelle» (ou la couverture maladie universelle, CMU) peut être utilisée pour justifier pratiquement toute réforme ou tout régime du financement des soins de santé. Ce document présente la définition du financement des soins de santé pour une couverture universelle, telle qu'elle apparaît dans le Rapport sur la santé dans le monde 2010 de l'Organisation mondiale de la Santé, afin de montrer comment la CMU incarne les objectifs spécifiques et intermédiaires du système de santé et, plus généralement, comment les réformes du financement du système de santé peuvent influencer ces objectifs.

Tous les pays cherchent à améliorer l'équité dans l'utilisation des services de santé, dans la qualité des services et dans la protection financière des populations. Par conséquent, la survie de la CMU reste pertinente pour tous les pays. La politique de financement des soins de santé fait partie intégrante des efforts réalisés pour faire de la CMU une réalité, mais pour que cette politique de financement permette la survie de la CMU, les réformes du système de santé doivent viser explicitement l'amélioration de la couverture santé et les objectifs intermédiaires qui y sont liés, à savoir, l'efficacité, l'équité dans la répartition des ressources de la santé, ainsi que la transparence et la responsabilisation.

L'unité d'analyse de ces objectifs doit prendre en compte la population et le système de santé dans son ensemble. Ce qui importe, ce n'est pas comment un système de financement particulier affecte chacun de ses membres, mais plutôt comment il influe sur les progrès et conduit vers une CMU à l'échelle des populations. Les préoccupations autour des programmes spécifiques sont incompatibles avec une approche de couverture universelle et peuvent même nuire à la CMU, notamment en termes d'équité. Et inversement, si un régime est pleinement orienté sur des objectifs systémiques, il peut étendre les progrès réalisés à la CMU. Les analyses des politiques et les politiques elles-mêmes doivent changer d'échelle pour passer du simple régime au système.

Resumen

A menos que se entienda el concepto con claridad, “cobertura universal” (o cobertura sanitaria universal) se puede utilizar para justificar casi cualquier reforma o plan de financiación sanitaria. El presente documento amplía la definición de financiación de la salud para una cobertura universal, tal y como se utiliza en el Informe sobre la salud en el mundo 2010 de la Organización Mundial de la Salud, a fin de mostrar cómo la cobertura sanitaria universal abarca los objetivos concretos e intermedios relacionados con los sistemas sanitarios y, en sentido amplio, cómo pueden influir en los mismos las reformas de financiación sanitaria.

Todos los países pretenden mejorar la igualdad en la utilización de los servicios sanitarios, la calidad de estos y la protección financiera de su población. Por ello, la búsqueda de una cobertura sanitaria universal es importante para cada país. La política de financiación de la salud es un elemento esencial en los esfuerzos para avanzar hacia la cobertura sanitaria universal. Sin embargo, para que las estrategias de financiación de la salud estén en línea con la procura de la cobertura sanitaria universal, las reformas del sistema sanitario deben aspirar de forma explícita a mejorar la cobertura y los objetivos intermedios relacionados con esta, a saber, la eficacia, la igualdad en la distribución de los recursos, así como la transparencia y la responsabilidad.

La unidad sobre la cual se deben analizar las metas y objetivos debe ser la población y el sistema sanitario en conjunto. Lo importante no es cómo un modelo particular de financiación afecta a cada uno de sus miembros, sino cómo influye en el progreso hacia la cobertura sanitaria universal a nivel de la población. Si únicamente concierne a proyectos concretos, será incompatible con un enfoque universal e incluso podría minar la cobertura sanitaria universal, particularmente en lo que respecta a la igualdad. Por el contrario, si un plan se enfoca por completo hacia los objetivos y las metas a nivel del sistema, se puede continuar avanzando hacia la cobertura sanitaria universal. Las estrategias y los análisis de estrategias tienen que cambiar desde el nivel del plan al nivel del sistema.

ملخص

يمكن استخدام "التغطية الشاملة" (أو التغطية الصحية الشاملة، UHC) لتبرير أي إصلاح أو مخطط في مجال التمويل الصحي بشكل عملي، ما لم يتم فهم المفهوم بوضوح. وتشرح هذه الورقة تعريف التمويل الصحي من أجل التغطية الشاملة وفق استخدامه في التقرير الخاص بالصحة في العالم لعام 2010 الصادر عن منظمة الصحة العالمية، لإيضاح مدى اشتمال التغطية الصحية الشاملة على مرامي معينة وأغراض متوسطة للنظام الصحي، والكيفية التي يمكن أن تؤثر بها إصلاحات التمويل الصحي عليها، على نحو واسع.

تسعى جميع البلدان لتحسين الإنصاف في استخدام الخدمات الصحية وجودة الخدمات والحماية المالية لسكانها. ولذا، توجد صلة لهدف التغطية الصحية الشاملة بكل بلد. وتعد سياسة التمويل الصحي جزءاً لا يتجزأ من الجهود الرامية للتوجه صوب التغطية الصحية الشاملة، ولكن لكي تتماشى سياسة التمويل الصحي مع هدف التغطية الصحية الشاملة، يجب أن تستهدف إصلاحات النظم الصحية بوضوح تحسين التغطية والأغراض المتوسطة المرتبطة بها، وتحديدًا، الكفاءة والإنصاف في توزيع الموارد الصحية والشفافية والمساءلة.

يجب أن تكون وحدة التحليل للمرامي والأغراض هي السكان والنظام الصحي ككل. وما يستحق الاهتمام ليس الكيفية التي يؤثر بها مخطط تمويلي معين على أعضائه الفرديين، وإنما هو الكيفية التي يؤثر بها على التقدم صوب التغطية الصحية الشاملة على الصعيد السكاني. ولا يتوافق القلق بشأن مخططات معينة فقط مع أسلوب التغطية الشاملة بل قد يقوض التغطية الصحية الشاملة، ولاسيما الإنصاف. وفي مقابل ذلك، إذا تم توجيه أحد المخططات بشكل كامل صوب المرامي والأغراض على مستوى النظام، فإنه يستطيع إحراز مزيد من التقدم صوب التغطية الصحية الشاملة. ويتعين أن تتحول السياسات وتحليل السياسات من المخطط إلى مستوى النظام.

摘要

除非概念非常清楚,“全面医保”(或全民健康保险,UHC)实际上可以用来证明任何医疗融资改革或计划。本文分析世界卫生组织的《2010年世界卫生报告》中使用的全面医保的卫生筹资定义,以说明UHC如何体现特定卫生系统目标和中间目标,并更广泛地说明卫生筹资改革如何影响这些目标。

所有国家都追求提高其公民在使用卫生服务、服务质量和金融保护方面的公平性。因此,UHC目标对每个国家都很重要。卫生筹资政策是实现UHC的工作组成部分,但卫生筹资政策要与UHC目标看齐,卫生系统改革需要明确改善医保范围以及与其关联的中间目标,即在卫生资源分配、透明度和问责制方面的效率和公平。

目的和目标的分析单位必须是整体人口与健康系统。重要的不是特定的筹资计划如何影响其个别成员,而是它如何影响群体水平上的UHC进展。只局限于具体方案的做法与合全民医保方法格格不入,甚至可能破坏UHC,在公平方面尤其如此。反之,如果计划完全面向系统层面的目标和目的,它可以进一步迈向UHC。政策和政策分析需要从计划转移到系统层面。

Резюме

В отсутствие четкого понимания соответствующей концепции понятие «единая система» (или «единая система здравоохранения», ЕСЗ) может использоваться при обосновании практически любой реформы или схемы финансирования. В данной статье раскрыто понятие финансирования здравоохранения применительно к единой системе здравоохранения, которое используется в публикации «Доклад о состоянии здравоохранения в мире в 2010 году» Всемирной Организации Здравоохранения, чтобы продемонстрировать, как ЕСЗ реализует конкретные задачи системы здравоохранения и достигает ее промежуточных целей, а также показать в общих чертах, как на это могут повлиять реформы финансирования системы здравоохранения.

Все государства стремятся к обеспечению равенства доступа населения к медицинским услугам, качеству обслуживания и финансовой защите. Поэтому стремление к созданию ЕСЗ свойственно каждому из них. Политика финансирования здравоохранения является составной частью усилий по продвижению к ЕСЗ, однако, чтобы она соответствовала стремлению к ЕСЗ, реформы системы здравоохранения должны быть четко направлены на улучшение охвата и достижение связанных с ним промежуточных целей, а именно, на эффективность, справедливое распределение ресурсов здравоохранения, обеспечение прозрачности и ответственности.

Предметом анализа для определения целей и задач должны быть население и система здравоохранения в целом. Это подразумевает изучение не того, как конкретная схема финансирования воздействует на ее отдельных участников, а скорее того, как она влияет на продвижение к ЕСЗ на уровне населения. Интерес только к конкретным схемам несовместим с подходом, который подразумевается единой системой здравоохранения, и даже может подрывать принципы ЕСЗ, особенно в плане обеспечения справедливости. И наоборот, если схема полностью ориентирована на достижение целей и задач на уровне всей системы, она способна обеспечить дальнейшее продвижение к ЕСЗ. Политика и ее анализ должны перейти с уровня схемы на уровень системы.

Introduction

Since the publication of The world health report 2010,1 universal coverage (also often referred to as universal health coverage or UHC) has received increased attention. Like having a “sustainable health financing system”, it is something that sounds very good. But what does it mean, exactly, and why is it something worth pursuing?

The world health report 2010 contains the following definition of health financing for universal coverage:

“Financing systems need to be specifically designed to: provide all people with access to needed health services (including prevention, promotion, treatment and rehabilitation) of sufficient quality to be effective; [and to] ensure that the use of these services does not expose the user to financial hardship.”1

Some of the debates around recent reform experiences, particularly those related to the interpretation of what is meant by “insurance”,2–5 suggest that there remains a lack of common understanding about the concept portrayed in The world health report 2010. This is not merely an academic debate; conceptual differences create operational differences in terms of the health financing policy choices made by countries, what they are advised to do, and how reforms are assessed. This paper aims to clarify what is meant by health financing for universal coverage; how UHC embodies specific health system goals and intermediate objectives, what is the appropriate unit of analysis for these, and, broadly, the ways in which health financing can influence progress towards UHC. An assessment of specific policy options or recommendations for reform is beyond the scope of the paper, although some illustrations are provided.

The next section of this paper derives a set of generic policy objectives for health financing policy from the framework for health system performance of the World Health Organization (WHO). The third section justifies UHC, as defined above, as an aim of health policy by linking it explicitly to the goals of the health systems framework. This is followed by a discussion of the three dimensions of coverage. Next is a further specification of both UHC goals and intermediate objectives, followed by an illustration of the types of health financing reforms that can influence progress towards UHC. The sixth section contains a discussion of the unit of analysis for UHC and of the practical importance of understanding the distinction between schemes and systems. The final section of the paper summarizes the core messages arising from this conceptual approach.

Health financing and system performance

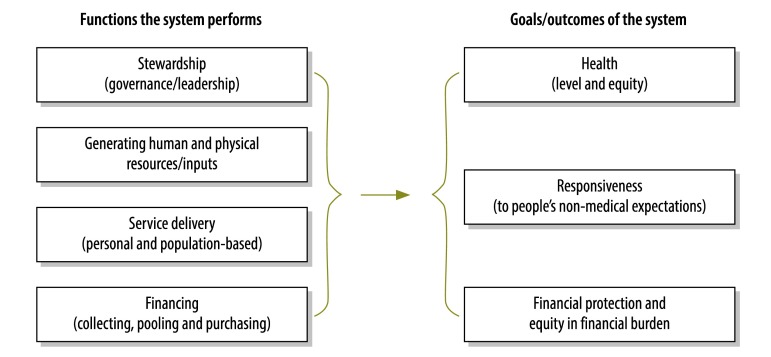

The starting point for the approach used goes back to The world health report 2000, on health system performance.6,7 The framework used for that report identified three generic goals and four generic functions of all health systems (WHO reconfigured these four functions into six “building blocks”,8 but the framework is the same, as is the application to health financing policy used here). The aim of any health system is to maximize the attainment of the goals (adjusted for the relative importance that a country attaches to each), conditioned by contextual factors from outside the health system that influence the level of goal attainment that can be reached (e.g. a country’s income, education levels, political factors, etc.). A simplified depiction of this framework is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Health system functions and goals

Adapted from Duran et al., 2011.9

The general challenge for health policy is reflected in the arrow in the middle of Fig. 1: how do the functions influence the goals? Of course, the goals are influenced by social determinants emanating from outside the health system, but the policy focus here is on health system policies and actions. So to put this somewhat more precisely, how does the way the system is designed and operating affect the extent to which the goals are attained, given the impact of extra-sectoral factors in a given country context? In what ways are shortcomings in attainment linked to health system problems, and conversely, how can deliberate changes in how the health system operates (i.e. reforms) improve goal attainment? To “fill in the missing middle” of the health system framework shown in Fig. 1, the connections between the system and the goals need to be understood. Although this is a general issue for health systems and thus concerns each of the four functions (separately and together),9 the concern here is how the financing function can influence the attainment of the goals.10 This approach leads to the identification of a more specific set of financing policy objectives that can be targets of health financing policy actions. These are:

policy objectives that are essentially identical to broad health system goals, namely promoting universal protection against financial risk and a more equitable distribution of the burden of funding the system; and

policy objectives that are intermediate and instrumental to the broad health system goals: (i) promoting equitable use and provision of services relative to the need for such services; (ii) improving the transparency of the system and its accountability to the population; (iii) promoting quality in service delivery; and (iv) improving efficiency in the organization and delivery of health services and in the administration of the health system.

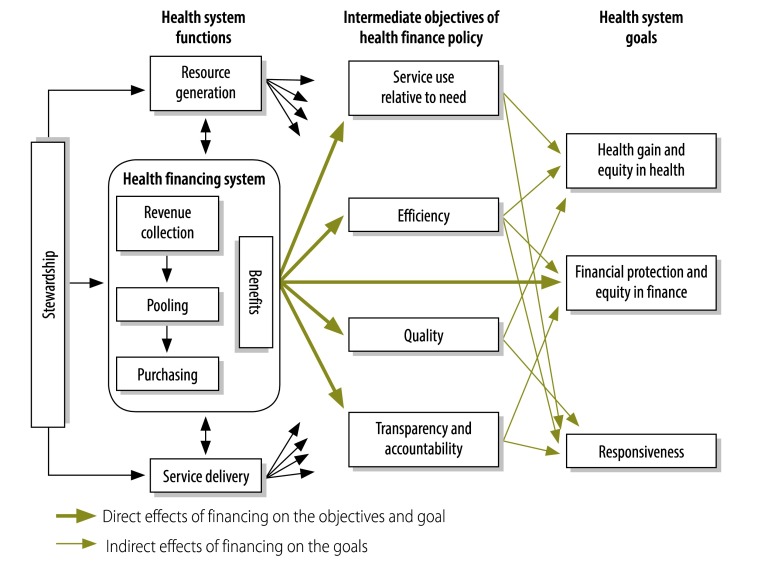

The connection between health financing and overall system goals, directly and indirectly via the intermediate objectives, is depicted in Fig. 2. One important concept illustrated in the figure is that the health financing system does not act alone in affecting the intermediate objectives and final goals; coordinated policy and implementation across health system functions are essential for making progress on the desired objectives, such as improving the quality of care. Many countries, moreover, face problems with physical access to health services and human resource supply, and again, financing policy alone cannot address these problems. These other health system functions exert an important influence on the goals, but examining this influence is beyond the scope of this paper, which is focused on health financing policy.

Fig. 2.

Health system goals and health financing policy objectives

Adapted from Kutzin J, 2008.10

The way health financing arrangements are organized often affects other social goals. Although they are not the focus of this paper, these effects are important for public policy. In particular, health financing mechanisms can influence individual choices and options with regard to employment. In countries that have a national system of coverage with a unified set of entitlements, as in most of western Europe, people are free to change jobs without fear of losing their health coverage. Conversely, where health insurance coverage is linked to one’s place of employment and there is neither compulsory coverage nor uniform entitlement, as in the United States of America, many people are “locked” into a job because they risk losing coverage if they take a new position with a different company.11 In a study by Bansak et al., a reform that “untied” coverage from employment was shown to enhance people’s opportunities to switch jobs.12 There is also some evidence that publicly funded coverage programmes in Mexico13 and Thailand14 have slowed the pace of labour market formalization because they have reduced the need for people to make formal social security contributions to obtain good health coverage.

Where does universal coverage fit in?

The definition of UHC from The world health report 2010, quoted in the introduction, embodies one of the ultimate goals of health systems – financial protection – as well as intermediate objectives associated with improved health system performance: that all people obtain the health services they need (i.e. equity in service use relative to need) and that these services are of sufficient quality to be effective.

The first aspect of UHC defined above (use of needed services of good quality) corresponds closely to the concept of effective coverage, i.e. the probability that an individual will get an intervention that they need and experience better health as a result.15 This concept can be disaggregated into the following elements:

reducing the gap in a country’s population between the need for services and the use of those services, which implies that: (i) all persons who need an intervention are aware of their need; and (ii) all persons who are aware of their need are able to use the services that they require;

ensuring that services are of sufficient quality to increase the likelihood that they will improve (or promote, maintain, restore, etc., depending on the nature of the intervention) the health of those who use them.

Measuring effective coverage across all services and the entire health system is not feasible. To date, this has been done only in the case of individual health conditions and interventions, such as immunization coverage (e.g. a cross-country review)16 or hypertension control (e.g. in Kyrgyzstan);17 a specific set of interventions within one aspect of care, such as maternal and neonatal health interventions (e.g. in Nepal);18 or a wide but still limited set of interventions (e.g. in Mexico and China).19,20

Despite this difficulty with measurability, the concept of effective coverage is useful for orienting health policy. When combined with financial protection, it enables a more precise specification of UHC: it is system-wide effective coverage combined with universal financial protection.

Although the objectives embedded within UHC are distinct, UHC is a unified concept. From the perspective of any citizen or resident of a country, the problem boils down to this: Can I sleep well at night secure in the knowledge that if anything happens to me or a member of my family, good health services will be accessible and affordable, that is, obtainable without risk of a severe and long-term impact on my financial well-being? The extent to which the objectives of equity in the use of needed services of good quality with financial protection are realized is simultaneously determined at the person’s point of contact with the health system. For example, if measures are introduced to reduce financial barriers to service use, we are likely to observe both increased utilization across the entire population and a reduced financial burden for those using care.

Given the definition of UHC and its specification here, however, fully achieving UHC is impossible for any country. Even countries that succeed in attaining universal financial protection have shortfalls in effective coverage. Gaps will always exist because not all individuals in a society can be aware of all of their needs for services, new and more expensive diagnostic and therapeutic technologies continuously emerge, and the quality of care is not perfect in any country. Thus, strictly speaking, no country in the world has achieved universal coverage.

Despite this, however, the aims of improving equity in the use of services, service quality and financial protection are widely shared. Thus, even if UHC can never be fully achieved, moving towards UHC is relevant to all countries. It is justified from a health system performance perspective because it implies progress in attaining the goals of health systems: directly in terms of financial protection and indirectly on the goals of health and responsiveness via the intermediate objectives associated with effective coverage. Put another way, it is more useful to think of UHC as a direction rather than a destination.

UHC is a set of objectives that health systems pursue; it is not a scheme or a particular set of arrangements in the health system. Keeping this distinction between policy objectives and policy instruments is essential for conceptual clarity and practical decision-making. Making progress towards UHC is not inherently synonymous with increasing the percentage of the population in an explicit insurance scheme. In some countries, such as Germany and Japan, insurance schemes are the instruments used to ensure financial access and financial protection for the entire population. Hence, the percentage of the population covered by insurance is a critical determinant of progress on UHC objectives in those countries. But in 1989, when the Republic of Korea achieved universal population coverage under its social health insurance system, most citizens were still at risk for very high and potentially catastrophic out-of-pocket payments because of the large and open-ended nature of cost sharing arrangements, particularly in a hospital setting.21 In some other countries, such as Sweden and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, financial access and financial protection for all are achieved without anything called an insurance scheme. But in countries where constitutional or other promises of “free services” are not realized, as in many low- and middle-income countries, citizens remain at risk of financial hardship if they need health services.

The universal coverage “cube”

The world health report 2010 depicted three dimensions of coverage as the axes of a cube: population, service and cost.1 The population axis describes the UHC objective of population coverage with both services and financial protection. The cost coverage axis is critical to the financial protection objective, although it needs to be interpreted relative to capacity to pay. And by defining the service coverage axis in terms of needed and effective services, this dimension captures the objectives of ensuring that everyone is able to use the health services that they need and that these services are of good quality. These three dimensions connect closely to health financing policies related to UHC and to the monitoring of UHC.

Ex ante, the cube portrays policies on benefit design, reflecting decisions on who is entitled to what services and how much they are obligated to pay for those services at the time of use. This is an important aspect of health financing policy, but it is not the whole story. Benefit design needs to be coordinated with policies on revenue collection, pooling arrangements and purchasing to enable the defined benefits to be realized in practice.22

Ex post, the cube provides a monitoring framework for UHC. It can be used to graphically depict how many people received various needed health services of sufficient quality and how much they had to pay. This can be portrayed, in simple terms, as the per cent of the cube that is filled with pooled funds, although it is conceptually feasible to introduce refinements to this to capture, for example, out-of-pocket expenditures relative to people’s ability to pay for them, or service use relative to each person’s need for services.23 But progress towards UHC is not simply about “filling the cube” (as discussed in the section on the unit of analysis for UHC).

Intermediate objectives

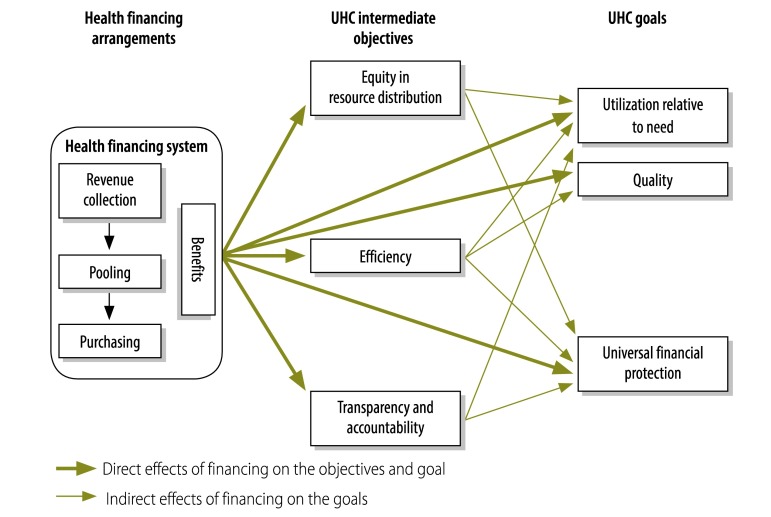

As shown in Fig. 2, health financing influences the final goals and intermediate objectives of health systems. The links to UHC can be made even more precise by connecting financing policy to the three goals or objectives associated with UHC: (i) reducing the gap between need and utilization; (ii) improving quality, and (iii) improving financial protection. This is shown in Fig. 3. As noted earlier in the paper, reforms only in health financing policy are not sufficient to improve quality, improve people’s awareness of their need for services, or remove barriers to the use of care. Financing policy can, however, influence each of these directly. For example, governments can allocate a greater share of public revenues to health to increase the size of the prepaid funding pool, thereby enabling greater attainment of financial protection and utilization goals. In addition, progress towards UHC can be promoted through actions to improve efficiency, equity in the distribution of resources, and transparency and accountability. These intermediate objectives for UHC are described in greater detail here.

Fig. 3.

Intermediate objectives and final goals of universal health coverage (UHC) that health financing can influence

As reflected in the figure, improving efficiency has a central role in improving coverage. Given that all health systems face resource constraints, improving efficiency (i.e. making better use of available resources) is a means to “get more” in terms of attaining the objectives associated with UHC and, more generally, the goals of health systems. Actions that stimulate efficiency have the same potential effects as an increase in the level of health spending – each of these measures can enable greater attainment of UHC objectives, assuming that the “savings” from efficiency gains are retained and reallocated within the health system. The assumption is important. Efficiency should not be equated simply with “cost containment” or as an excuse to reduce public spending on health. Certainly from a health policy perspective, the aim is to increase attainment from a given level of funding rather than to reduce funding to achieve the same level of attainment. More broadly, however, evidence suggests that when the efficiency gains are treated as “savings” by a country’s finance authorities, the incentives for further efficiency gains are diminished.24,25 This suggests that extracting efficiencies from the sector in the name of budgetary savings is self-defeating.

By positioning efficiency as an intermediate objective, we make explicit the point that health systems can become more efficient at promoting financial protection and increased, equitable utilization of health services relative to need (and conversely, that inefficiencies undermine these objectives). Gains in efficiency are essential for attenuating the severity of the trade-offs that countries must inevitably make in light of financial – and particularly fiscal – constraints26,27 and for higher attainment of goals in circumstances in which more money can be put into the system.

As reflected in Fig. 3, financing reforms that improve equity in the distribution of resources can also lead to improvements in equity in the use of services and financial protection. This objective can be operationalized in several ways depending on what is relevant to a particular country, but the overall aim is to match the distribution of resources to the relative health service needs of different individuals and groups in the population.28 In some countries, such as the Republic of Moldova,29 a relevant concern is attaining greater equalization in the level of public spending on health per capita across geographic areas. In other countries, notably Mexico30 and Thailand,31 redressing inequities in the distribution of public subsidies across financing schemes has been a priority, whereas South Africa is concerned with reducing inequity in the distribution of total health spending on behalf of the insured and uninsured populations.32 As shown in these studies, increasing (or reducing) equity in the distribution of health spending (contextualized for the aspect of equity relevant to each country) tends to improve (or worsen) both equity in the use of services and financial protection.

The objective of improving transparency and accountability seems inherently desirable, of course, but it needs to be specified more precisely to enable the link to UHC to be operationalized. Two useful ways to think about this are:

transparency in terms of people’s understanding of their entitlements (rights) and their obligations with regard to health service use, as well as the extent to which these are realized in practice; and

transparency and accountability of health financing agencies (e.g. extent of corruption, public reporting on performance).33

If people improve their understanding of the services to which they are entitled, they will be more empowered to demand what has been promised. Improving this aspect of transparency can thus contribute to reducing the gap between the need for services and their use.34 It may also contribute to improved financial protection in settings where lack of transparency manifests as informal payments.35 Similarly, improving the accountability of health financing agencies (e.g. social health insurance funds) for the use of public resources is likely to translate into a better use of resources. Or conversely, corruption in the health sector can be seen as a source of inefficiency insofar as resources that could have been used to improve access, quality or financial protection are diverted to other uses.36

Getting the unit of analysis right

The equity and universality aspects of the definition of UHC have important, practical implications for both policy and the analysis of various reforms. Universal means universal, so for any country, the appropriate unit of analysis is the entire population and the system as a whole. This is in contrast to being concerned only with financing schemes and their members. There is a difference between a new insurance scheme designed for the purpose of making its members better off, and one intended to serve as an agent of change to improve equity in the use of services, service quality and financial protection for the entire population. This is perhaps the most important operational issue at stake in the conceptualization of UHC: real problems can and do arise when the success of a scheme is assumed to be generalizable to the wider system. Two issues are highlighted here in regard to this: (i) a scheme may make some people better off at the expense of the rest of the system or population; and (ii) the design features that emerge from a scheme with objectives set at the system level are very different from those emerging from a scheme in which the objectives are set only at the scheme level.

The first point can be illustrated most clearly in the case of voluntary health insurance. Excluding poor persons or others with high health risks contributes to the financial viability of a voluntary health insurance scheme, as is well known from the experience of the United States. In one study, for example, smoking and obesity were associated with a lack of ability to obtain voluntary coverage and smoking was associated with the loss of voluntary coverage.37 Thus, for those who can afford it, a voluntary insurance scheme can offer good benefits, particularly if it systematically excludes people known to have high health risks (e.g. people with hypertension, diabetes, human immunodeficiency virus infection, etc.). Financial access and financial protection are enhanced for scheme members, but at the expense of others in the population who do not have the opportunity to benefit from this.

This problem is magnified in contexts of greater resource scarcity. In South Africa, for example, about 40% of total health spending benefits 16% of the population that is covered by a “medical scheme” (i.e. employment-linked voluntary health insurance that typically services upper-income persons). The entire population is entitled to use public facilities, but these are overcrowded and poorly resourced, particularly in comparison with the private providers who tend to serve insured persons. So, although everyone is entitled to something, the concentration of health spending – and thus system resources – on behalf of insured people means that equity in service use is far from a reality in South Africa. Financing arrangements contribute to a health system favouring the rich, with total expenditure for the insured population being from 4.5 to 6 times higher than for people who only use publicly-funded health services, a distribution pattern very unlikely to reflect need. The concentration of resources on behalf of the insured has a spillover effect on those without this form of coverage:

“…the existence of a pool of funds that is such a large share of total health care funds inevitably impacts on the distribution of health care professionals between the public and private health sectors, and hence contributes to a skewed distribution of service benefits.”32

In effect, good coverage for some people comes at the expense of the rest. The interests of the scheme(s) are in conflict with UHC objectives at the level of the entire system.

A similar situation can exist in the case of mandatory social health insurance (SHI), particularly in low- and middle-income contexts where such schemes begin with the population that has regular, salaried employment (the “formal sector”). Starting an explicit insurance programme for this population has long been recommended.38 Indeed, in a recent review of experiences with health insurance published in the Bulletin, the authors conclude that:

“SHI [schemes] hold strong potential to improve financial protection and enhance utilization among their enrolled populations […] This underscores the importance of health insurance as an alternative health financing mechanism capable of mitigating the detrimental effects of user fees, and as a promising means for achieving universal healthcare coverage.”2

But their logic is flawed. The fact that scheme members have better financial protection and increased access does not mean that these have improved for the entire population. Furthermore, where SHI schemes begin by covering the formal sector, they tend to concentrate resources on a relatively small and economically advantaged part of the population. Such schemes do not naturally “evolve” to include the rest of the population. Instead, the initially covered groups, who tend to be well organized and influential, use their power to increase their benefits and subsidies, rather than to extend the same benefits to the rest of the population.22,39–41 As a result, the initial enrolment in the SHI scheme “increases coverage” only in the sense that more people are in an explicit health insurance scheme. However, this reform strategy moves the health system away from UHC. The initial members of the scheme were in the higher income bracket and thus already enjoyed better financial access and greater ability to cope with out-of-pocket expenses. Creating a scheme for them simply exacerbates these underlying inequalities in both financial access to services and financial protection.

This was the case in both Mexico and Thailand, where SHI contributions for the formal sector are directly subsidized by transfers from general tax revenues, a practice that contributes to public per capita spending on the schemes that protect the more affluent population being considerably higher than for the rest of the population.30,42 Over the past 10 years, these countries have implemented reforms that have reduced these inequities, but, notably, neither has been able to integrate the population outside the formal workforce into the pre-existing schemes. Inequalities in coverage remained even after the advent of these reforms. In Thailand, for example, the Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS) – the health financing scheme for the population not covered by either the scheme for civil servants or that for private firm employees – did not cover haemodialysis treatment for kidney disease, while the other two schemes did. This explicit inequality in entitlements was inconsistent with UHC because it was not linked to need, but rather, to whether or not an individual was employed in the formal sector. Pressure from civil society organizations led to the inclusion of renal replacement therapy in the scheme, but the financial consequences for the UCS are more severe than for the other two schemes, which continue to be funded at higher levels.43

UHC implies that the focus needs to shift from scheme to system. By conceptualizing a new insurance scheme as an instrument to reform the entire system rather than as an end in itself, design features can be tailored to promoting a universal population approach from the beginning. This is reflected in the reform experience of Kyrgyzstan and, to some extent, the Republic of Moldova.44 Both countries took a “whole systems approach” to the design of their financing policies and measured progress not in terms of the per cent of the population covered by their schemes, but of the impact on equity in service use and financial protection across the entire population. In each case, the path to universality was designed into the reform from an early stage by putting payroll tax contributions and general revenue transfers into the same pool on behalf of both the formal and informal sector populations, and then using the new SHI funds to drive system-wide efficiency and equity gains through the combination of centralized pooling and output-based provider payment mechanisms.45,46

Hence, from the perspective of UHC, whether or not a financing scheme improves attainment of coverage objectives for its members is not intrinsically important; what matters is the impact of that scheme on the attainment of the objectives for the population and system as a whole. Assessing schemes simply with respect to whether or not they improve coverage for their members is both inadequate and a potential source of misleading policy recommendations. Depending on the details of policy design in a given context, a scheme may contribute to or detract from UHC objectives for the population as a whole. Explicit attention to this is essential.

Towards action on universal coverage

“Health financing for UHC” reflects how health financing arrangements (and reforms to these) can influence UHC goals and intermediate objectives. In The world health report 2010, three broad strategies were summarized as:

“more money for health” (raising more funds);

“strength in numbers” (larger pools); and

“more health for the money” (improving efficiency and equity in the use of funds through reforms in purchasing and pooling as well as actions not directly related to health financing).

It is beyond the scope of this paper to recommend or suggest what reforms to implement. Nonetheless, the following examples illustrate the kinds of actions that can promote progress towards UHC:

Introduction of new revenue-raising mechanisms or increasing the share of total public spending devoted to health, to increase the level of compulsory prepaid revenues for health, thereby making possible greater attainment of any or all of the objectives;

risk-adjusted equalization of budgets or payments to health care providers or purchasing agencies, to improve equity in the distribution of resources and services;

reduction of fragmentation in pooling to expand the redistributive capacity of prepaid funds, thereby enabling greater financial protection and equity in the distribution of resources and services from a given level of resources;

simplification and promotion of the benefit package to increase people’s awareness of their entitlements; and

performance-related provider payments, to create incentives for improved quality and efficiency in service delivery.

These are merely examples intended to illustrate some ways in which financing reforms – actions taken to alter arrangements for revenue collection, pooling, purchasing and benefit design – can support progress towards UHC. Because of the connotations often associated with the word “insurance”, it is worth noting that every country’s health financing system performs these functions, either explicitly or implicitly. Thus, for example, introducing a purchaser–provider split or changing how pooling arrangements are organized are not only issues for so-called “insurance systems”. Just as moving towards UHC – i.e. progressing on the intermediate and final objectives associated with UHC – is relevant to every country, so too do all health financing systems include the functions of collection, pooling and purchasing, and face decisions on the rationing of benefit entitlements. The specific label attached to a given system should not be used to limit thinking with regard to reform options.

Conclusion

Universal coverage can be justified from a political perspective as a reflection of underlying values such as social cohesion, the belief in every individual’s right to the highest attainable level of health (as per the WHO Constitution), or as a “right to health” or “right to equitable access to health services”, specified in many national constitutions. But from a narrower health systems performance perspective, UHC as defined in The world health report 2010 is desirable because it embodies both a final goal of health systems and intermediate objectives with strong links to ultimate goals.

Strictly interpreted, UHC is a utopian ideal that no country can fully achieve. To translate UHC into country-specific reality involves disaggregating the concept into its component objectives and emphasizing progress towards (rather than full achievement of) these goals: improving equity in the use of needed health services, improving service quality and improving financial protection. All countries share these goals to varying degrees. Therefore, making progress towards UHC is relevant to every country in the world.

Making such progress requires action across the health system, not only in financing policy. For example, health financing cannot do much to improve people’s awareness of their health needs. Financing policy action is a necessary but not sufficient condition for progress.

Universal means universal. The appropriate unit of analysis when planning or analysing reforms is the entire population. How a particular financing scheme affects its members is not of interest per se; what matters is how the scheme influences UHC goals at the level of the entire population. A concern only with specific schemes is not a universal coverage approach. Schemes can contribute to system-wide UHC goals, but they need to be explicitly designed to do so. Otherwise, increased population coverage with health insurance can actually become a potential obstacle to progress towards UHC.

The combination of UHC goals and intermediate objectives can be used to set the direction of health financing reforms in any country, when contextualized into specific and measurable objectives for that country. “Health financing for universal coverage” implies that reforms in collection, pooling, purchasing and benefit design are aimed specifically at improving one or several of those objectives and goals, as measured at the population or system level. All health financing systems perform these functions, and this is why, as stated in The world health report 2010, every country can do something to move towards universal health coverage.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to David Evans, Tamás Evetovits, Matthew Jowett and Inke Mathauer for helpful comments.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.The world health report – Health systems financing: the path to universal coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spaan E, Mathijssen J, Tromp N, McBain F, ten Have A, Baltussen R. The impact of health insurance in Africa and Asia: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90:685–92. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.102301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apoya P, Marriott A. Achieving a shared goal: free universal healthcare in Ghana Oxford: Oxfam International; 2011. Available from: http://www.oxfam.org/sites/www.oxfam.org/files/rr-achieving-shared-goal-healthcare-ghana-090311-en.pdf [accessed 4 June 2013].

- 4.Glassman A. Center for Global Development Blog [Internet]. Amanda Glassman. Really Oxfam? Really? [Posted 14 March 2011]. Available from: http://blogs.cgdev.org/globalhealth/2011/03/really-oxfam-really.php [accessed 12 June 2013].

- 5.Global Health Check [Internet]. Dhillon RS. A closer look at the role of community-based health insurance in Rwanda’s success Oxford: Oxfam International; 2011. Available from: http://www.globalhealthcheck.org/?p=324 [accessed 4 June 2013].

- 6.The world health report – Health systems: improving performance. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray CJL, Frenk J. A framework for assessing the performance of health systems. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:717–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Everybody’s business: strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes. WHO’s framework for action Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. Available from: http://www.who.int/entity/healthsystems/strategy/everybodys_business.pdf [accessed 12 June 2013].

- 9.Duran A, Kutzin J, Martin-Moreno JM, Travis P. Understanding health systems: scope, functions and objectives. In: Figueras J, McKee M, editors. Health systems, health, wealth and societal well-being: assessing the case for investing in health systems Berkshire: Open University Press; 2011. pp. 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kutzin J. Health financing policy: a guide for decision-makers Copenhagen: World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe, Division of Country Health Systems; 2008 (Health Financing Policy Paper 2008/1). Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/78871/E91422.pdf [accessed 12 June 2013].

- 11.Gruber J, Madrian BC. Health insurance, labor supply, and job mobility: a critical review of the literature Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2002 (Working Paper 8817).

- 12.Bansak C, Raphael S. The State Children’s Health Insurance program and job mobility: identifying job lock among working parents in near-poor households. Ind Labor Relat Rev. 2008;61:564–79. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aterido R, Hallward-Driemeier M, Pagés C. Does expanding health insurance beyond formal-sector workers encourage informality? Washington: The World Bank; 2011 (Policy Research Working Paper 5785).

- 14.Wagstaff A, Manachotphong W. Universal health care and informal labor markets: the case of Thailand Washington: The World Bank; 2012 (Policy Research Working Paper 6116).

- 15.Shengelia B, Tandon A, Adams OBR, Murray CJL. Access, utilization, quality, and effective coverage: an integrated conceptual framework and measurement strategy. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:97–109. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lessler J, Metcalf CJE, Grais RF, Luquero FJ, Cummings DAT, Grenfell BT. Measuring the performance of vaccination programs using cross-sectional surveys: a likelihood framework and retrospective analysis. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jakab M, Lundeen E, Akkazieva B. Health system effectiveness in hypertension control in Kyrgyzstan. Bishkek: Center for Health System; 2007 (Policy Research Paper No. 44). Available from: http://www.hpac.kg/custom/download.php?title=Health+Systems+Effectiveness+in+Hypertension+Control+in+Kyrgyzstan&download=PRP44.E.pdf [accessed 12 June 2013].

- 18.Pradhan YV, Upreti SR, Pratap KCN, Ashish KC, Khadka N, Syed U, et al. Nepal Newborn Change and Future Analysis Group Newborn survival in Nepal: a decade of change and future implications. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27(Suppl 3):iii57–71. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lozano R, Soliz P, Gakidou E, Abbott-Klafter J, Feehan DM, Vidal C, et al. Benchmarking of performance of Mexican states with effective coverage. Lancet. 2006;368:1729–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69566-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Y, Rao K, Wu J, Gakidou E.China’s health system performance. Lancet 20083721914–23.http//dx..org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61362-8 PMID18930536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang B-M. Health insurance in Korea: opportunities and challenges. Health Policy Plan. 1991;6:119–29. doi: 10.1093/heapol/6.2.119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kutzin J. A descriptive framework for country-level analysis of health care financing arrangements. Health Policy. 2001;56:171–204. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8510(00)00149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans DB, Saksena P, Elovainio R, Boerma T. Measuring progress towards universal coverage Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fuenzalida-Puelma HL, O’Dougherty S, Evetovits T, Cashin C, Kacevicius G, McEuen M. Purchasing of health care services. In: Kutzin J, Cashin C, Jakab M, editors. Implementing health financing reform: lessons from countries in transition Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 2010. pp. 155–86. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chakraborty S, O’Dougherty S, Panopoulou P, Cvikl MM, Cashin C. Aligning public expenditure and financial management with health financing reforms. In: Kutzin J, Cashin C, Jakab M, editors. Implementing health financing reform: lessons from countries in transition Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 2010. pp. 269–98. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomson S, Foubister T, Figueras J, Kutzin J, Permanand G, Bryndová L. Addressing financial sustainability in health systems Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 2009 (Policy Summary 1). Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/76041/E93058.pdf [accessed 12 June 2013].

- 27.Thomson S, Võrk A, Habicht T, Rooväli L, Evetovits T, Habicht J. Responding to the challenge of financial sustainability in Estonia’s health system Tallinn: World Health Organization; 2010. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/107877/E93542.pdf [accessed 12 June 2013].

- 28.Wagstaff A. The World Bank Blog [Internet]. Washington: Adam Wagstaff. What’s the “universal health coverage” push really about? [Posted 10 November 2010]. Available from: http://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/what-s-the-universal-health-coverage-push-really-about [accessed 12 June 2013].

- 29.Shishkin S, Jowett M. A review of health financing reforms in the Republic of Moldova Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 2012 (Health Financing Policy Paper 2012/1). Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/166788/E96542.pdf [accessed 12 June 2013].

- 30.Knaul FM, González-Pier E, Gómez-Dantés O, García-Junco D, Arreola-Ornelas H, Barraza-Lloréns M, et al. The quest for universal health coverage: achieving social protection for all in Mexico. Lancet. 2012;380:1259–79. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61068-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prakongsai P, Limwattananon S, Tangcharoensathien V. The equity impact of the universal coverage policy: lessons from Thailand. In: Chernichovsky D, Hanson K, editors. Innovations in health system finance in developing and transitional economies Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing; 2009. pp. 57–81. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ataguba JE, McIntyre D. Paying for and receiving benefits from health services in South Africa: is the health system equitable? Health Policy Plan. 2012;27(Suppl 1):i35–45. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kutzin J. Conceptual framework for analysing health financing systems and the effects of reforms. In: Kutzin J, Cashin C, Jakab M, editors. Implementing health financing reform: lessons from countries in transition Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 2010. pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gotsadze G, Gaál P. Coverage decisions: benefit entitlements and patient cost sharing. In: Kutzin J, Cashin C, Jakab M, editors. Implementing health financing reform: lessons from countries in transition Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 2010. pp. 187–217. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gaál P, Jakab M, Shishkin S. Strategies to address informal payments for health care. In: Kutzin J, Cashin C, Jakab M, editors. Implementing health financing reform: lessons from countries in transition Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 2010. pp. 327–60. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Transparency International. Global corruption report 2006: special focus on corruption and health London: Pluto Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jerant A, Fiscella K, Franks P. Health characteristics associated with gaining and losing private and public health insurance: a national study. Med Care. 2012;50:145–51. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31822dcc72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shaw RP, Griffin CC. Financing health care in sub-Saharan Africa through user fees and insurance Washington: The World Bank; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Savedoff WD. Is there a case for social insurance? Health Policy Plan. 2004;19:183–4. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czh022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kutzin J. Health insurance for the formal sector in Africa: yes, but... Geneva: World Health Organization, Division of Analysis, Research and Assessment; 1997 (WHO/ARA/CC/97.4). [Google Scholar]

- 41.González Rossetti A. Social health insurance in Latin America London: Institute for Health Sector Development; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nitayarumphong S, Pannarunothai S. Achieving universal coverage of health care through health insurance: the Thai situation. In: Nitayarumphong S, Mills A, editors. Achieving universal coverage of health care Nontaburi: Ministry of Public Health; 1998. pp. 257–80. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Treerutkuarkul A. Thailand: health care for all, at a price. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:84–5. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.010210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kutzin J, Jakab M, Shishkin S. From scheme to system: social health insurance and the transformation of health financing in Kyrgyzstan and Moldova. In: Chernichovsky D, Hanson K, editors. Innovations in health system finance in developing and transitional economies Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing; 2009. pp. 291–312. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kutzin J, Ibraimova A, Jakab M, O’Dougherty S. Bismarck meets Beveridge on the Silk Road: coordinating funding sources to create a universal health financing system in Kyrgyzstan. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:549–54. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.049544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shishkin S, Jowett M. A review of health financing reforms in the Republic of Moldova Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 2012 (Health Financing Policy Paper 2012/1). Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/166788/E96542.pdf [accessed 12 June 2013].