Abstract

Expression and function of selenoproteins in endocrine tissues remain unclear, largely due to limited sample availability. Pigs have a greater metabolic similarity and tissue size than rodents as a model of humans for that purpose. We conducted 2 experiments: 1) we cloned 5 novel porcine selenoprotein genes; and 2) we compared the effects of dietary selenium (Se) on mRNA levels of 12 selenoproteins, activities of 4 antioxidant enzymes, and Se concentrations in testis, thyroid, and pituitary with those in liver of pigs. In Experiment 1, porcine Gpx2, Sephs2, Sep15, Sepn1, and Sepp1 were cloned and demonstrated 84–94% of coding sequence homology to human genes. In Experiment 2, weanling male pigs (n = 30) were fed a Se-deficient (0.02 mg Se/kg) diet added with 0, 0.3, or 3.0 mg Se/kg as Se-enriched yeast for 8 wk. Although dietary Se resulted in dose-dependent increases (P < 0.05) in Se concentrations and GPX activities in all 4 tissues, it did not affect the mRNA levels of any selenoprotein gene in thyroid or pituitary. Testis mRNA levels of Txnrd1 and Sep15 were decreased (P < 0.05) by increasing dietary Se from 0.3 to 3.0 mg/kg. Comparatively, expressions of Gpx2, Gpx4, Dio3, and Sep15 were high in pituitary and Dio1, Sepp1, Sephs2, and Gpx1 were high in liver. In conclusion, the mRNA abundances of the 12 selenoprotein genes in thyroid and pituitary of young pigs were resistant to dietary Se deficiency or excess.

Introduction

Testis, thyroid, and pituitary are 3 major endocrine organs in the body that regulate growth, reproduction, and metabolism. The discovery of the impaired thyroid hormone metabolism in selenium (Se)-deficient animals (1,2) and the subsequent identification of deiodinases (3) signified the crucial roles of Se in endocrine functions. Although a number of studies have followed those initial experiments to explore Se biology in thyroid and other endocrine organs (for review, see 4,5), gene expressions of selenoproteins, especially the recently identified members, and their responses to dietary Se alterations remain largely unclear. Apparently, the limited availability of human samples and the small sizes of rodent samples represent one of the greatest challenges for any research of endocrine organs. In fact, pigs offer a greater physiological similarity and organ size than rodents as an excellent model of humans for this purpose (6,7).

Only 7 of the 24/25 selenoprotein genes (8) identified in mice and humans were cloned in pigs. These include Gpx1, Gpx4, Dio1, Dio3, Txnrd1, Selk, and Sepw1. There was no information on the other porcine selenoprotein genes except for the expressed sequence tag (EST)6 of Gpx2, Sephs2, Sep15, Sepn1, and Sepp1. Among these genes, Gpx1, Gpx2, and Gpx4 code for 3 of the 5 Se-dependent glutathione peroxidases (GPX); Dio1 and Dio3 for 2 of the 3 iodothyronine deiodinases; and Txnrd1 for 1 of the 3 thioredoxin reductases. Sepp1 codes for selenoprotein P (SelP) that accounts for >50% of the Se in plasma (9). Sepw1 codes for selenoprotein W that is highly expressed in muscle and brain (10). Sephs2 codes for selenophosphate synthetase 2 that catalyzes the formation of monoselenophosphate, the Se donor required for selenocysteine (Sec) synthesis (11). Sep15 codes for selenoprotein 15kDa that is a redox protein associated with UDP-glucose:glycoprotein glucosyltransferase in endoplasmic reticulum and probably plays a role in the quality control of misfolded proteins (12). Sepn1 codes for selenoprotein N that is associated with muscle diseases (13). Selk codes for selenoprotein K that is another redox protein located in endoplasmic reticulum (14). Although characterizing the metabolic functions of all these selenoproteins will probably take a long time, the sequence homology analysis of the porcine EST database allows us to isolate the novel selenoprotein genes from pigs by in silico (computational) cloning followed by PCR and sequencing (15). The cloned sequence information will help us in designing primers to study regulation of these novel selenoprotein genes by dietary Se in pigs.

Previously, regulations of selenoprotein gene expression by dietary Se were determined mainly by using sodium selenite as the Se source and northern blot as the method of mRNA quantification. Data from those studies may present questionable physiological relevance and limited precision, because organic Se is the main source of Se in ordinary human diets (16,17) and northern blot provides only a semiquantitative estimate of mRNA abundances. Se-enriched yeast may be a better source of Se than sodium selenite (17) and real-time quantitative PCR (Q-PCR) is a more sensitive and accurate method for that type of research (18). Therefore, we conducted 2 experiments to: 1) clone Gpx2, Sephs2, Sep15, Sepn1, and Sepp1 from pig tissues based on their candidate fragments from the porcine nucleotide database and characterize their sequence homology with the human genes; and 2) compare effects of 3 concentrations of dietary Se (as Se-enriched yeast) on mRNA levels of 12 selenoproteins assayed by Q-PCR, activities of 4 antioxidant enzymes, and Se concentrations in testis, thyroid, and pituitary with those in liver of young male pigs.

Materials and Methods

Experiment 1

Cloning of novel selenoprotein genes in porcine tissues.

Based on the database of National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), we selected Gpx2, Sephs2, Sep15, Sepn1, and Sepp1 as the cloning targets in the present study. Data mining was conducted as previously described (19). Briefly, the mRNA (cDNA) or protein sequence of the human selenoprotein gene was used as the query sequence to search for highly similar sequences in pigs using the appropriate BLAST programs (NCBI). The acquired sequences in pig were assembled and extended using Vector NTI (Invitrogen, version 9.1.0). If the similar sequence(s) linked to UniGene database, more EST were available for assembling. The assembled gene was considered as a selenoprotein gene if the in-frame TGA for Sec was identified in the open reading frame and the Sec insertion sequence (SECIS) element in the 3′-untranslated region was identified by the online program SECISearch (8).The target porcine gene was amplified by RT-PCR. Primers (Supplemental Table 1) were designed based on homology analysis of the in silico cloned (presumed) selenoprotein gene sequence with the same gene from other species. If no similar porcine sequences were found by in silico cloning, sequences of the target gene from human, mouse, rat, and cattle were aligned to design degenerated primers in the highly conserved region. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen catalog no. 15596–026) from spleen (for Sephs2 and Sep15), muscle (for Sepn1), small intestine (for Gpx2), and kidney (for Sepp1) of a Se-adequate, adult male Landrace pig. These tissues were selected as the RNA source for a given target gene based on the assumption that pigs and humans or mice share similar tissue mRNA abundance for the gene. The RT-PCR and the subsequent T/A cloning were carried out using commercial kits (TaKaRa, Dalian; reverse transcriptase, catalog no. D2620; DNA polymerase, catalog no. DR001AM, and pMD18-T vector catalog no. D101). A minimum of 3 positive transformants were sequenced for each gene (Invitrogen) and the sequence with the highest consensus was submitted to GenBank (NCBI).

Experiment 2

Pig, diet, and sample collection.

Our protocol was approved by the Animal Care Office of Sichuan Agricultural University. A total of 30 weanling male pigs (3-wk old, PIC strain, Sichuan Lanyan Group) were selected and fed a Se-deficient, corn-soybean meal (produced in the Se-deficient area in Sichuan, China) basal diet (BD) (Table 1) for 4 wk to adjust their Se status. The pigs were divided into 3 groups (n = 10) and fed the BD supplemented with 0, 0.3, or 3.0 mg Se/kg as Se-enriched yeast (Angel Yeast) for 8 wk. The analyzed Se concentrations in the experimental diets were 0.02, 0.30, and 3.05 mg/kg, respectively. At baseline and then biweekly, body weights were recorded for and blood samples collected from individual pigs. Plasma samples were prepared by centrifugation of the whole blood (2200 × g; 15 min; 5804R Centrifuge, F45–30–11 rotor, Eppendorf) and stored at −80°C. At the end of the study, 6 pigs from each treatment group were killed to collect liver, testis, thyroid, and pituitary. After immediate dissection on an ice-cold surface, the organs were perfused with ice-cold isotonic saline, minced with surgical scissors, divided into aliquots, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until use.

TABLE 1.

Composition of BD (as fed)

| Ingredients1 | Content, g/kg |

|---|---|

| Corn | 688.2 |

| Soybean meal | 280.0 |

| Choline | 1.0 |

| l-Lysine | 4.0 |

| dl-Methionine | 0.5 |

| l-Tryptophan | 0.3 |

| l-Threonine | 1.5 |

| Salt | 3.0 |

| CaHPO4 | 7.0 |

| CaCO3 | 4.0 |

| Trace mineral premix2 | 10.0 |

| Vitamin premix3 | 0.5 |

The Se concentrations of corn, soybean, and Se-rich yeast (Angel Yeast) were 0.005, 0.03, and 1000 mg/kg. Analyzed Se concentration in the BD was 0.02 mg/kg.

Trace mineral premix provided per kg diet: FeSO4·7H2O, 993 mg; CuSO4·5H2O, 786 mg; ZnSO4·7H2O, 440 mg; MnSO4, 27.5 mg; KI, 0.4 mg; and colistin sulfate, 40 mg.

Vitamin premix provided per kg diet: retinyl acetate, 3027 μg; cholecalciferol, 22 μg; dl-α-tocopheryl acetate, 32 mg; menadione, 2 mg; thiamin, 4 mg; riboflavin, 14 mg; calcium pantothenate, 40 mg; niacin, 60 mg; pyridoxol, 6 mg; d-biotin, 0.2 mg; folacin, 1.2 mg; and cobalamin, 72 μg.

Concentrations of Se and activities of enzymes.

The hydride generation-atomic fluorescence spectrometer (AFS-830, Titan Instruments) (20) was used to measure tissue and plasma Se concentrations against the standard Se reference [GBW (E) 080441, National Research Center for Certified Reference Materials, Beijing, China]. Tissue samples (0.2 g for pituitary and 0.5 g for other tissues) were thawed on ice and homogenized as previously described (21). Activities of GPX were measured by the coupled-method (22) (0.12 mmol/L of H2O2 as substrate) using an ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometer (DU800, Beckman). To assess the general antioxidant status of the experimental pigs, activities of glutathione reductase were measured using the method of Massey and Williams (23), activities of glutathione S-transferase were measured using a GST assay kit (A004, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute), and activities of superoxide dismutase were measured as described by Elstner and Heupel (24). Concentrations of protein were determined using the Bradford method (25).

Q-PCR analysis of the selenoprotein mRNA abundance.

Primers (Supplemental Table 2) for the 12 selenoprotein genes (5 of them were cloned in this study) and 2 reference genes, β-actin gene (Actb) and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene (Gapdh), were designed using Primer Express 3.0 (Applied Biosystems). The total RNA was extracted as described above. Potential DNA contamination of the extraction was eliminated using the DNA-free kit (Ambion, catalog no. AM1906) and the RNA quality was verified by both agarose gel (1%) electrophoresis and spectrometry (A260/A280). The mRNA levels of selenoprotein genes were analyzed using Q-PCR (ABI 7900HT, Applied Biosystems). Briefly, RT and PCR amplifications were conducted in duplicates for both target and reference genes. Negative controls containing the template RNA and all PCR reagents, but not reverse transcriptase, were included to determine the RNA purity from DNA contamination. The reaction mixture (6.0 μL) contained 3.0 μL of freshly premixed 2× QuantiTect SYBR Green RT-PCR Master mix and QuantiTect RT mix (QIAGEN, catalog no. 204243), 0.4 μmol/L of the primer pair, and 100 ng of RNA template. The PCR consisted of 1 cycle of 48°C for 30 min, 1 cycle of 95°C for 10 min, and 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 58°C for 1 min, followed by the dissociation step at 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 20 s, and 95°C for 15 s. To confirm the specific amplification, melt curve analysis was performed (Supplemental Fig. 1) and the products were also visualized on ethidium bromide-stained 2% (wt:v) agarose gel after electrophoresis using Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer.

Relative mRNA abundances of the 12 selenoprotein genes in the 4 tissue samples were determined using the Δ cycle threshold (ΔCt) method as outlined in the protocol of Applied Biosystems. In brief, a ΔCt value was the Ct difference between the target selenoprotein gene and the reference gene (ΔCt = Cttarget – Ctreference). Actb was used as the reference gene and its reliability was confirmed by the perfect parallelism of its Ct values in all the tissue samples with those of Gapdh (Supplemental Fig. 2). For each of the target selenoprotein genes, the ΔΔCt values of all the samples were then calculated by subtracting the average ΔCt of the liver from the ΔCt of all the other tissue samples. The ΔΔCt values were converted to fold differences by raising 2 to the power –ΔΔCt (2−ΔΔCt).

Statistical analysis.

One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni t test (SPSS for Windows 13.0) was used to test the effects of the 3 dietary Se levels on each variable within the same tissue. Two-way ANOVA was used to determine the tissue-specific distribution for a given gene at the same dietary Se level. Data are presented as means ± SE. The null hypothesis was rejected if P < 0.05 (2-tailed).

Results

Experiment 1

Porcine Gpx2, Sephs2, Sep15, Sepn1, and Sepp1 were cloned and their sequences were submitted to NCBI (Table 2). Based on the secondary structures of their SECIS elements (Supplemental Fig. 3), Gpx2, Sephs2, and Sepn1 belong to form 1, whereas Sep15 and Sepp1 belong to form 2 (26). Among the 5 novel genes, the number of base pairs in the coding sequence (CDS) was 573 for Gpx2, 1356 for Sephs2, 489 for Sep15, and 1173 for Sepp1. The incomplete Sepn1 CDS had 1498 base pairs and lacked ∼180 base pairs in the 5′-site. There were 14 in-frame TGA codons in the porcine Sepp1, but only 1 in each of the other 4 novel genes. Between pigs and humans, the CDS homology ranged from 84 to 94% and the protein sequence homology was ≥92% for all the genes except for Sepp1 (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of the 5 novel pig selenoprotein genes

| Accession no. | Length |

Identity to human |

Sec position1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | CDS | Peptide | CDS | Peptide | ||

| bp | amino acids | % | ||||

| Gpx2 | DQ898282 | 573 | 190 | 94 | 97 | 40 |

| Sephs2 | EF033624 | 1356 | 451 | 89 | 92 | 63 |

| Sep15 | EF178474 | 489 | 162 | 85 | 93 | 93 |

| Sepn12 | EF113595 | 1498 | 498 | 93 | 93 | 370 |

| Sepp1 | EF113596 | 1173 | 390 | 84 | 76 | 14 Sec3 |

From the N terminus.

About 180 bp in the 5′-site of CDS of porcine Sepn1 was not available, which in turn resulted in the absence of ∼60 amino acids in the N terminus of the protein sequence. The missing counterpart in the CDS or peptide of human Sepn1 was not compared for the identity analysis.

Positions of the 14 Sec in the Sepp1 peptide were at the 59, 267, 286, 309, 311, 327, 339, 352, 354, 361, 376, 378, 385, and 387 residuals.

Experiment 2

Growth performance, tissue Se concentration, and enzyme activity.

Pigs fed the 3 dietary Se concentrations had similar growth performance (Supplemental Table 3). Plasma Se concentrations of pigs were increased (n = 6; P < 0.05) by 0.3 and 3.0 mg Se/kg relative to the Se-deficient pigs (0.02 mg Se/kg) at the end of study, whereas GPX3 activities were sigmoidally raised (Table 3). Compared with 0.3 mg Se/kg, dietary Se deficiency decreased (P < 0.05), whereas dietary Se excess increased (P < 0.05) the Se concentrations in all 4 tissues. Liver had the greatest relative (19% to 3-fold) fluctuation in Se concentration between 0.02 and 3.0 mg Se/kg among the 4 tissues. Likewise, dietary Se deficiency decreased (P < 0.05) GPX activity by 95% in liver but only 32% in pituitary. However, pigs fed 3.0 mg Se/kg had similar (43–88%) increases in GPX activity among all 4 tissues relative to those of pigs fed 0.3 mg Se/kg. Dietary Se concentrations did not affect activities of the other 3 antioxidant enzymes in any of the 4 tissues (Supplemental Table 4).

TABLE 3.

Tissue Se concentration and GPX activity of pigs fed diets containing 0, 0.3, or 3.0 mg Se/kg for 8 wk1

| Measures | BD | BD + 0.3 mg Se/kg | BD + 3.0 mg Se/kg |

|---|---|---|---|

| Se, μmol/L plasma or nmol/g tissue | |||

| Plasma | |||

| Initial (wk 0) | 0.61 ± 0.04 | 0.73 ± 0.04 | 0.68 ± 0.08 |

| Final (wk 8) | 0.29 ± 0.04a | 1.42 ± 0.10b | 2.45 ± 0.12c |

| Liver | 1.03 ± 0.13a | 5.46 ± 0.34b | 16.40 ± 1.02c |

| Testis | 1.48 ± 0.16a | 2.59 ± 0.22b | 4.60 ± 0.23c |

| Thyroid | 0.57 ± 0.04a | 1.85 ± 0.08b | 5.22 ± 0.11c |

| Pituitary2 | 3.10 | 4.35 | 6.07 |

| GPX, EU/mg protein | |||

| Plasma | |||

| Initial (wk 0) | 15.24 ± 1.45 | 16.62 ± 1.00 | 19.50 ± 1.85 |

| Final (wk 8) | 3.96 ± 1.05a | 13.26 ± 1.08b | 14.38 ± 1.70b |

| Liver | 7.96 ± 1.59a | 168.77 ± 19.27b | 282.84 ± 11.75c |

| Testis | 15.23 ± 0.91a | 25.27 ± 3.85a,b | 36.08 ± 3.64b |

| Thyroid | 1.83 ± 0.21a | 11.43 ± 1.64b | 21.41 ± 1.60c |

| Pituitary | 18.03 ± 1.45a | 26.32 ± 3.98a | 45.90 ± 2.30b |

Values are means ± SE, n = 6. Means in a row with superscripts without a common letter differ, P < 0.05.

Samples were pooled by group due to limited amounts of tissue.

Abundances of selenoprotein mRNA.

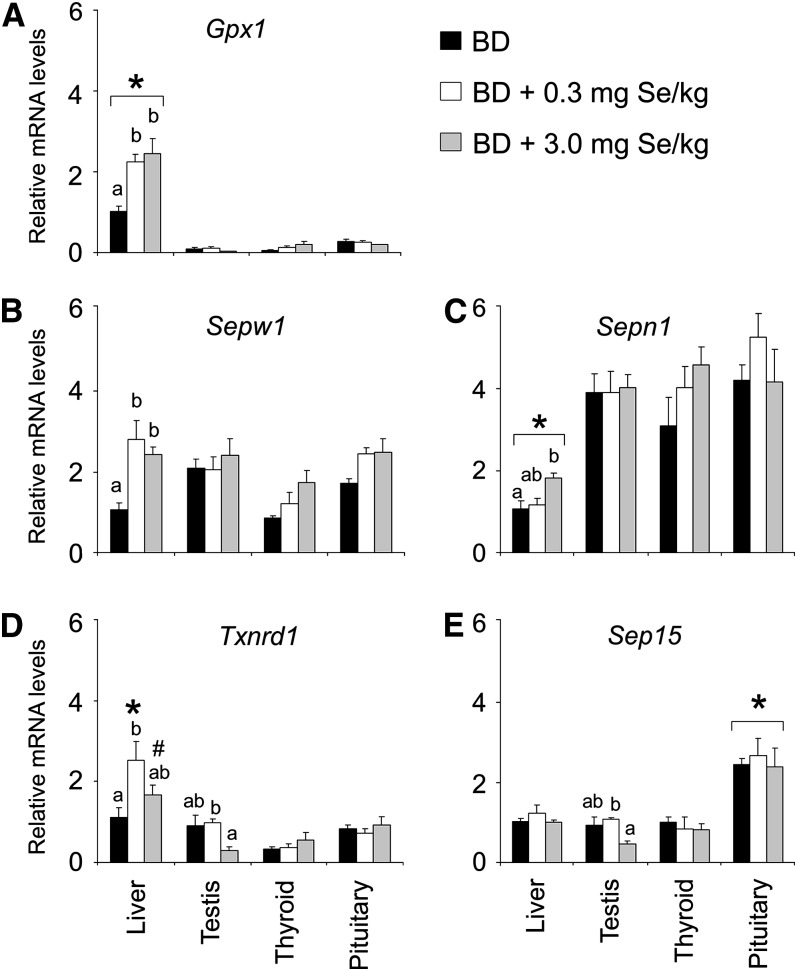

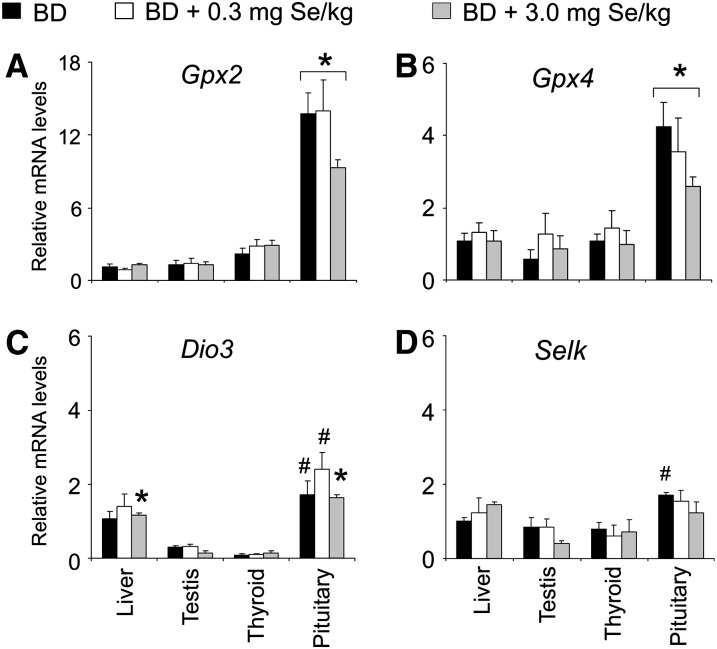

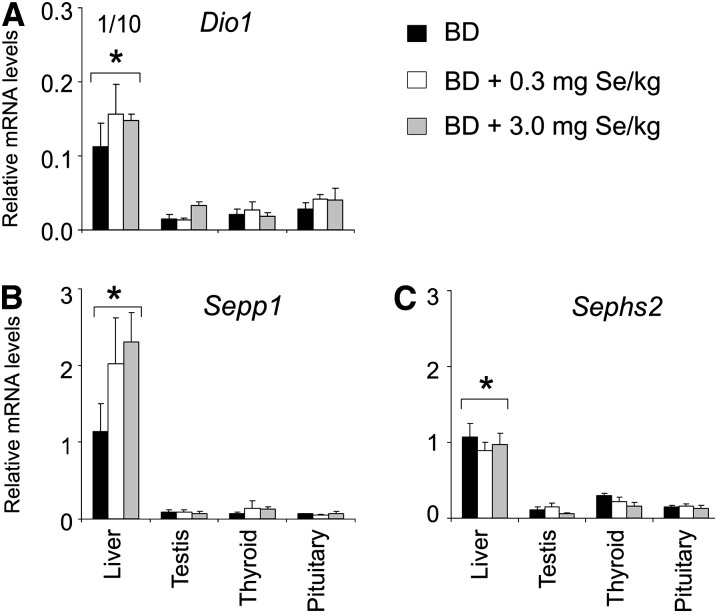

Compared with pigs fed 0.3 and/or 3.0 mg Se/kg, those fed the BD had lower (P < 0.05) mRNA levels of Gpx1, Sepw1, Sepn1, and Txnrd1 (Fig. 1A–D) in liver. In contrast, pigs fed 3.0 mg Se/kg had lower (P < 0.05) mRNA levels of Txnrd1 and Sep15 in testis than those fed 0.3 mg Se/kg (Fig. 1D,E). Dietary Se did not affect the mRNA levels of any gene in thyroid and pituitary or Gpx2, Gpx4, Dio3, Selk, Dio1, Sepp1, and Sephs2 in liver and testis (Figs. 2 and 3). Pituitary had higher (P < 0.05) mRNA levels of Gpx2, Gpx4, Dio3, and Sep15 than the other 3 tissues at all 3 dietary Se concentrations. Pituitary also had higher (P < 0.05) mRNA levels of Selk than testis and thyroid at dietary Se deficiency. Compared with the endocrine tissues, liver had higher (P < 0.05) mRNA levels of Dio1, Sepp1, Sephs2, and Gpx1 at all 3 dietary Se concentrations and higher (P < 0.05) mRNA levels of Txnrd1 at 0.3 mg Se/kg.

FIGURE 1 .

Abundance of Gpx1, Sepw1, Sepn1, Txnrd1, and Sep15 mRNA in tissues of pigs fed 0, 0.3, or 3.0 mg Se/kg diet for 8 wk. Data are means ± SE, n = 4. Within a tissue, labeled means without a common letter differ, P < 0.05. *Different from other tissues at that Se concentration, P < 0.05. #Different from corresponding testis and thyroid, P < 0.05.

FIGURE 2 .

Abundance of Gpx2, Gpx4, Dio3, and Selk mRNA in tissues of pigs fed 0, 0.3, or 3.0 mg Se/kg for 8 wk. Data are means ± SE, n = 4. *Different from other tissues at that Se concentration, P < 0.05. #Different from corresponding testis and thyroid, P < 0.05.

FIGURE 3 .

Abundance of Dio1, Sepp1, and Sephs2 mRNA in tissues of pigs fed 0, 0.3, or 3.0 mg Se/kg for 8 wk. Data are means ± SE, n = 4. Values for Dio1 mRNA abundances in liver were minimized to 10% of the originals, indicated by “1/10.” *Different from other tissues at that Se concentration, P < 0.05.

Discussion

All 5 cloned novel porcine selenoprotein genes, Gpx2, Sephs2, Sep15, Sepn1, and Sepp1, bear the 2 identifications of selenoproteins: in-frame TGA (UGA) codon and SECIS element in the 3′- untranslated region (8,26). Like their homologs reported in other mammals, Gpx2, Sephs2, Sep15, and Sepn1 code respective selenoproteins with 1 Sec. In contrast, the porcine Sepp1 mRNA (cDNA) contains 14 Sec codons and 11 of them appeared in the last 100 amino acid residues. This number of Sec is within the range of 10 to 17 in SelP characterized from other species (27) and their location in the protein is consistent with the fact that the C-terminal, Se-rich domain of SelP is critical for the maintenance of Se in brain and testis (28). The SECIS elements of the 5 pig selenoprotein genes, like other eukaryotic SECIS elements, fall into 2 classes of structural models: form 1 and form 2 (26). Compared with the human homologs, the DNA sequences in the CDS of the 5 porcine selenoproteins had a homology of 84–94% and the deduced amino acid sequences had a homology ≥92%, except for Sepp1. Thus, our success in cloning the 5 novel porcine selenoprotein genes and in demonstrating their high sequence homology to the human homologs provides molecular justification for the use of pigs as a human model to study Se biology in endocrine tissues.

The results of Expt. 2 show similar responses of Se distribution and GPX activity to dietary Se between liver and the 3 endocrine tissues. Although dietary Se deficiency downregulated mRNA levels of Gpx1, Sepw1, Sepn1, and Txnrd1 in liver, mRNA abundance of the 12 selenoprotein genes in thyroid and pituitary remained fairly constant across all 3 dietary Se concentrations. Probably due to a relative large variation, a potential downregulation of the Sepp1 mRNA abundance in liver by Se deficiency was not significant (P = 0.23). The downregulation of Gpx1 mRNA in the Se-deficient liver may be explained by the low rank of GPX1 in the hierarchy of selenoproteins in competing for Se (21,29–33) and the activation of nonsense-mediated decay under limited Se supply (33,34). The decreased hepatic mRNA levels of the other 3 selenoprotein genes in the Se-deficient pigs were also similar to those reported in other species, although their changes were somewhat less than those of Gpx1 (21,29,32,35,36). Whereas the hepatic Gpx4 mRNA remained unchanged by dietary Se in the present study, it was actually decreased by Se deficiency in a previous study in which pigs were fed sodium selenite and mRNA was detected using northern blot with a rat cDNA probe (30). The lack of decrease in mRNA abundances of Gpx1 and other selenoprotein genes in the 3 Se-deficient endocrine tissues implies at least 2 possibilities. First, the endocrine tissues rank higher than liver in the hierarchy of Se metabolism. Second, the nonsense-mediated decay of Gpx1 and other selenoprotein genes may not occur in the endocrine tissues. It will be interesting to find out how these 2 possibilities affect the overall control of Se metabolism and endocrine functions under various physiological conditions (37).

The downregulation of Txnrd1 and Sep15 mRNA levels in testis of pigs fed 3.0 mg Se/kg, compared with those fed 0.3 mg Se/kg, appears to be unique. Because these declines were not observed in the other 3 tissues, the expression of selenoprotein genes in testis seems to be more sensitive to the high level of dietary Se. As Txnrd1 and Sep15 code for antioxidant enzyme or protein that may control the quality of cellular proteins (12,38), downregulation of these genes in testis may be an outcome of Se toxicity (39–41) or help precipitate the toxicity. As shown in mice (42), pigs had higher hepatic mRNA abundances of Gpx1, Txnrd1, Dio1, Sepp1, and Sephs2 than those in the endocrine tissues. The higher Dio1 mRNA in liver than in thyroid helps explain why the hepatic iodothyronine deiodinase 1 is the most important in catalyzing the circulating thyroxine to the more active 3,5,3′-tri-iodothyronine, although thyroxine is produced and released from thyroid (2). Similarly, the high hepatic Sepp1 mRNA level is consistent with the fact that liver is the major source of plasma SelP (43). However, another group reported that testis had higher mRNA levels of Txnrd1 and Sepp1 than liver in rats (44). It is unclear if the discrepancy from our finding was due to species (rats vs. pigs), source of Se (sodium selenite vs. Se yeast), or detection method (ribonuclease protection analysis vs. Q-PCR). Notably, pituitary had higher mRNA levels of Gpx2, Gpx4, Dio3, and Sep15 than liver and the other 2 endocrine tissues. The abundant gene expression of these selenoproteins and their resistance to dietary or tissue Se alteration raise a question as to how these selenoproteins affect the pituitary endocrine function (5). Previously, Gpx2 mRNA expression was detected only in the gastrointestinal tissues and liver by northern blot (45). It will be interesting to discover the relative contribution of GPX2, along with GPX4, to the total GPX activity in pituitary. Expression of Sepn1 mRNA was higher in the 3 endocrine tissues than in liver. Being involved in a genetic muscular disorder and the early development and cell proliferation or regeneration (13), the production and function of selenoprotein N in endocrine tissues warrants more research.

Different from the dietary Se regulation of Gpx1 mRNA (29,31,44), we have observed 43–88% increases (P < 0.05) in GPX activity among all 4 tissues by elevating dietary Se from 0.3 to 3 mg/kg. This upregulation of tissue GPX1 activity by excess dietary Se is also different from the saturation of GPX1 activity in liver of rats or GPX3 activity in the plasma or serum of rats (31,32,46,47). In a previous pig study, GPX1 activity in thyroid and pituitary was not elevated by increasing dietary Se supplementation from 0.1 to 0.3 mg/kg (30). The discrepancy from the present study may be related to supplemental Se forms (organic vs. inorganic) and the interval of dietary Se concentrations (from 0.3 to 3.0 mg Se/kg vs. 0.1 to 0.3 mg Se/kg). Presumably, Se in the Se-enriched yeast exists mainly in the organic form such as selenomethionine (SeMet). When animals ingest this type of Se, their plasma and tissue Se concentrations contain Se present in selenoproteins and in randomly incorporated SeMet. When Se is transported out of liver into blood, the plasma GPX activity (assayed) and the SelP concentration (not assayed herein) reach plateaus. Then, the SeMet-derived Se probably plays a major role in continuously elevating the plasma Se concentration, because Se in small molecular forms counts for <3% of the total (48). This complicates the comparison of Se concentrations and GPX activities. Nevertheless, the concomitant elevations of Se concentration and GPX activity in tissues, particular in endocrine tissues, to the super-nutritional level of dietary Se supplementation may offer a different perspective for the antitumor mechanism of dietary Se (49). In addition, the lack of responses of mRNA levels of Gpx1 and other selenoprotein genes in any of the tissues to dietary Se increases from 0.3 to 3 mg/kg suggests limitation of these indicators to assess body Se status (50) when Se supply exceeds the requirement.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Professors Quan Sun, Zhangzheng Qin, Yuan Yang, and Ge Gao for their technical help.

Supported in part by the Chang Jiang Scholars Program of the Chinese Ministry of Education (X. G. L.) and the Chinese Natural Science Foundation (30628019 to X. G. L. and 30700585 to J. C. Z.).

Author disclosures: J.-C. Zhou, H. Zhao, J.-G. Li, X.-J. Xia, K.-N. Wang, Y.-J. Zhang, Y. Liu, Y. Zhao, and X. G. Lei, no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental Figures 1–3 and Supplemental Tables 1–4 are available with the online posting of this paper at jn.nutrition.org.

Abbreviations used: BD, basal diet; CDS, coding sequence; Ct, cycle threshold; EST, expressed sequence tag; GPX, glutathione peroxidase; NCBI, National Center for Biotechnology Information; Q-PCR, real-time quantitative PCR; Sec, selenocysteine; SECIS, selenocysteine insertion sequence; SelP, selenoprotein P; SeMet, selenomethionine.

References

- 1.Beckett GJ, Beddows SE, Morrice PC, Nicol F, Arthur JR. Inhibition of hepatic deiodination of thyroxine caused by selenium deficiency in rats. Biochem J. 1987;248:443–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arthur JR, Nicol F, Beckett GJ. Hepatic iodothyronine 5′-deiodinase: the role of selenium. Biochem J. 1990;272:537–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berry MJ, Banu L, Larsen PR. Type I iodothyronine deiodinase is a selenocysteine-containing enzyme. Nature. 1991;349:438–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beckett GJ, Arthur JR. Selenium and endocrine systems. J Endocrinol. 2005;184:455–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Köhrle J, Jakob F, Contempré B, Dumont JE. Selenium, the thyroid, and the endocrine system. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:944–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller ER, Ullrey DE. The pig as a model for human nutrition. Annu Rev Nutr. 1987;7:361–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wassen FWJS, Klootwijk W, Kaptein E, Duncker DJ, Visser TJ, Kuiper GGJM. Characteristics and thyroid state-dependent regulation of iodothyronine deiodinases in pigs. Endocrinology. 2004;145:4251–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kryukov GV, Castellano S, Novoselov SV, Lobanov AV, Zehtab O, Guigó R, Gladyshev VN. Characterization of mammalian selenoproteomes. Science. 2003;300:1439–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrison I, Littlejohn D, Fell GS. Distribution of selenium in human blood plasma and serum. Analyst. 1996;121:189–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeh JY, Beilstein MA, Andrews JS, Whanger PD. Tissue distribution and influence of selenium status on levels of selenoprotein W. FASEB J. 1995;9:392–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu XM, Carlson BA, Irons R, Mix H, Zhong N, Gladyshev VN, Hatfield DL. Selenophosphate synthetase 2 is essential for selenoprotein biosynthesis. Biochem J. 2007;404:115–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Korotkov KV, Kumaraswamy E, Zhou Y, Hatfield DL, Gladyshev VN. Association between the 15-kDa selenoprotein and UDP-glucose:glycoprotein glucosyltransferase in the endoplasmic reticulum of mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:15330–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petit N, Lescure A, Rederstorff M, Krol A, Moghadaszadeh B, Wewer UM, Guicheney P. Selenoprotein N: an endoplasmic reticulum glycoprotein with an early developmental expression pattern. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:1045–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu C, Qiu F, Zhou H, Peng Y, Hao W, Xu J, Yuan J, Wang S, Qiang B, et al. Identification and characterization of selenoprotein K: an antioxidant in cardiomyocytes. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:5189–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gill RW, Sanseau P. Rapid in silico cloning of genes using expressed sequence tags (ESTs). Biotechnol Annu Rev. 2000;5:25–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olson OE, Palmer S. Selenium in food consumed by South Dakotans. Proc S D Acad Sci. 1978;57:113–21. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schrauzer GN. Selenomethionine and selenium yeast: appropriate forms of selenium for use in infant formulas and nutritional supplements. J Med Food. 1998;1:201–6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein D. Quantification using real-time PCR technology: applications and limitations. Trends Mol Med. 2002;8:257–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jongeneel CV. Searching the expressed sequence tag (EST) databases: panning for genes. Brief Bioinform. 2000;1:76–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moreno ME, Pérez-Conde C, Cámara C. Speciation of inorganic selenium in environmental matrices by flow injection analysis-hydride generation-atomic fluorescence spectrometry. Comparison of off-line, pseudo on-line and on-line extraction and reduction methods. J Anal At Spectrom. 2000;15:681–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lei XG, Evenson JK, Thompson KT, Sunde RA. Glutathione peroxidase and phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase are differentially regulated by dietary selenium. J Nutr. 1995;125:1438–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawrence RA, Sunde RA, Schwartz GL, Hoekstra WG. Glutathione peroxidase activity in rat lens and other tissues in relation to dietary selenium intake. Exp Eye Res. 1974;18:563–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Massey V, Williams CH Jr. On the reaction mechanism of yeast glutathione reductase. J Biol Chem. 1965;240:4470–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elstner EF, Heupel A. Inhibition of nitrite formation from hydroxylammonium chloride: a simple assay for superoxide dismutase. Anal Biochem. 1976;70:616–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grundner-Culemann E, Martin GW III, Harney JW, Berry MJ. Two distinct SECIS structures capable of directing selenocysteine incorporation in eukaryotes. RNA. 1999;5:625–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tujebajeva RM, Ransom DG, Harney JW, Berry MJ. Expression and characterization of nonmammalian selenoprotein P in the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Genes Cells. 2000;5:897–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hill KE, Zhou J, Austin LM, Motley AK, Ham AJL, Olson GE, Atkins JF, Gesteland RF, Burk RF. The selenium-rich C-terminal domain of mouse selenoprotein P is necessary for the supply of selenium to brain and testis but not for the maintenance of whole body selenium. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:10972–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hill KE, Lyons PR, Burk RF. Differential regulation of rat liver selenoprotein mRNAs in selenium deficiency. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;185:260–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lei XG, Dann HM, Ross DA, Cheng WH, Combs GF Jr, Roneker KR. Dietary selenium supplementation is required to support full expression of three selenium-dependent glutathione peroxidases in various tissues of weanling pigs. J Nutr. 1998;128:130–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiss SL, Evenson JK, Thompson KM, Sunde RA. Dietary selenium regulation of glutathione peroxidase mRNA and other selenium-dependent parameters in male rats. J Nutr Biochem. 1997;8:85–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hadley KB, Sunde RA. Selenium regulation of thioredoxin reductase activity and mRNA levels in rat liver. J Nutr Biochem. 2001;12:693–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiss Sachdev S, Sunde RA. Selenium regulation of transcript abundance and translational efficiency of glutathione peroxidase-1 and -4 in rat liver. Biochem J. 2001;357:851–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moriarty PM, Reddy CC, Maquat LE. Selenium deficiency reduces the abundance of mRNA for Se-dependent glutathione peroxidase 1 by a UGA-dependent mechanism likely to be nonsense codon-mediated decay of cytoplasmic mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2932–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bermano G, Nicol F, Dyer JA, Sunde RA, Beckett GJ, Arthur JR, Hesketh JE. Selenoprotein gene expression during selenium-repletion of selenium-deficient rats. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1996;51:211–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vendeland SC, Beilstein MA, Yeh JY, Ream LW, Whanger PD. Rat skeletal muscle selenoprotein W: cDNA clone and mRNA modulation by dietary selenium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8749–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Small-Howard AL, Berry MJ. Unique features of selenocysteine incorporation function within the context of general eukaryotic translational processes. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:1493–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhong L, Arnér ESJ, Holmgren A. Structure and mechanism of mammalian thioredoxin reductase: the active site is a redox-active selenolthiol/selenenylsulfide formed from the conserved cysteine-selenocysteine sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5854–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaushal N, Bansal MP. Dietary selenium variation-induced oxidative stress modulates CDC2/cyclin B1 expression and apoptosis of germ cells in mice testis. J Nutr Biochem. 2007;18:553–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim YY, Mahan DC. Prolonged feeding of high dietary levels of organic and inorganic selenium to gilts from 25 kg body weight through one parity. J Anim Sci. 2001;79:956–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hawkes WC, Turek PJ. Effects of dietary selenium on sperm motility in healthy men. J Androl. 2001;22:764–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoffmann PR, Höge SC, Li PA, Hoffmann FW, Hashimoto AC, Berry MJ. The selenoproteome exhibits widely varying, tissue-specific dependence on selenoprotein P for selenium supply. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3963–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burk RF, Hill KE. Selenoprotein P. A selenium-rich extracellular glycoprotein. J Nutr. 1994;124:1891–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Evenson JK, Wheeler AD, Blake SM, Sunde RA. Selenoprotein mRNA is expressed in blood at levels comparable to major tissues in rats. J Nutr. 2004;134:2640–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chu FF, Doroshow JH, Esworthy RS. Expression, characterization, and tissue distribution of a new cellular selenium-dependent glutathione peroxidase, GSHPx-GI. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:2571–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buckman TD, Sutphin MS, Eckhert CD. A comparison of the effects of dietary selenium on selenoprotein expression in rat brain and liver. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1163:176–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mahan DC, Clone TR, Richert B. Effects of dietary levels of selenium-enriched yeast and sodium selenite as selenium sources, fed to growing-finishing pigs on performance, tissue selenium, serum glutathione peroxidase activity, carcass characteristics, and loin quality. J Anim Sci. 1999;77:2172–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burk RF, Hill KE, Motley AK. Plasma selenium in specific and non-specific forms. Biofactors. 2001;14:107–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Davis CD. Nutritional interactions: credentialing of molecular targets for cancer prevention. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2007;232:176–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Elsom R, Sanderson P, Hesketh JE, Jackson MJ, Fairweather-Tait SJ, Åkesson B, Handy J, Arthur JR. Functional markers of selenium status: UK food standards agency workshop report. Br J Nutr. 2006;96:980–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.