Abstract

Attempts to document changing HIV incidence rates among MSM are compromised by issues of generalizability and statistical power. To address these issues, this paper reports annualized mean HIV incidence rates from the entire published incidence literature on MSM from Europe, North America and Australia for the period 1995–2005. Publications that met the entry criteria were coded for region of the world, sampling method and year of study. From these reports, we calculated a mean incidence rate with confidence intervals for these variables. Although no differences in mean incidence rates were found for MSM from 1995 to 2005, HIV incidence rates are lower in Australia than either North America or Europe. We calculated a mean incidence rate of 2.39% for MSM in the United States, which if sustained within a cohort of MSM, would yield HIV prevalence rate of approximately 40% at age 40. These extrapolations overlap published HIV prevalence rates for MSM younger than age 40 in the United States. HIV incidence rates in the 2–3% range will adversely affect the health of gay male communities for decades to come. This analysis suggests that greater attention should be devoted to the question of how best to design prevention interventions that will lower HIV incidence rates among gay men.

Keywords: Men who have sex with men, HIV/AIDS, Epidemiology, Prevention

Introduction

The question that dominates current discussions of HIV incidence among men who have sex with men (MSM) is whether rates of new infections are rising (e.g. Jaffe et al. 2007; New York Times 2008). The concerns raised by the possibility that HIV incidence rates may be rising among MSM are certainly appropriate, since incidence provides an estimate of the rate at which a disease is spreading in a population and so the public health attention that should be devoted to that disease. Furthermore, HIV incidence provides a biologically-based estimate of AIDS risk, thereby avoiding the biases associated with other approaches to measuring epidemiological trends, such as self-reported behavioral measures of sexual risk taking. Thus, if HIV incidence rates are indeed rising among gay men, efforts to increase the effectiveness of current HIV prevention efforts should be attempted.

The attention devoted to the question of whether incidence rates are rising among MSM has been driven by ongoing reports of rising rates of widely used proxy markers for risk of HIV transmission, such as increasing rates of high risk sexual activity (e.g. Osmond et al. 2007) and sexually transmitted disease outbreaks among MSM (e.g. CDC 2006). On occasion, reports indicating heightened rates of positive test results for HIV antibody among MSM (e.g. Macdonald et al. 2004) and even reports of rising HIV incidence rates among MSM appear in the literature (e.g. Calzavara et al. 2002). Increases in any one of these measures could reasonably be interpreted to suggest that HIV incidence itself is rising, which, if true, would adversely affect health in MSM communities for decades to come.

The public health attention devoted to the question of whether HIV incidence rates are rising among MSM, and the tendency to rely on proxy markers for HIV incidence trends, highlights two important properties of the attempt to use HIV incidence to predict AIDS epidemiological trends among MSM. The first of these is that biological test data measuring HIV incidence within population-based samples are among the most valid measures of AIDS epidemiological trends available to us. The second is that incidence data that meet these methodological criteria are very difficult and expensive to generate, and this is especially true for MSM populations. However, incidence estimates from a single study may be biased because they are generated from non-representative samples of MSM or from cohort studies in which study procedures may have lowered risk taking behaviors and, by extension, seroconversion rates. Furthermore, given sample size issues, most HIV incidence estimates generated from MSM samples have large confidence intervals, thereby making it difficult to demonstrate increases or decreases in incidence rates over time. Combined, these methodological problems generally make it difficult to argue that any one stand-alone estimate of HIV incidence is a rigorous measure of epidemiological trends among the broad range of MSM communities.

Therefore, the goal of this paper will be to review the literature on HIV incidence among MSM in Western industrialized countries since 1995, or the period from the dawning of the period that saw the widespread utilization of HAART medications until 2006 for the purpose of providing a mean estimate of HIV incidence within this population. By providing a mean estimate of HIV incidence from the entire published literature on MSM, many of the interpretational problems associated with a single stand-alone incidence estimate can be avoided. From this literature we calculate overall incidence estimates for MSM in industrialized countries. Second, using data from the United States, we provide an extrapolation of what mean incidence estimates will yield in terms of prevalence over time within a new cohort of American MSM who are now 20 years of age. Finally, we compare these projections to current prevalence rates among MSM younger than 40 years of age (i.e. men aged less than 15 years of age when AIDS was first discovered and who have lived most of their adult lives within the background mean incidence rates described in this paper). We end this paper with recommendations for the use of HIV incidence data to improve AIDS prevention practice among MSM.

Methods

Search Procedures

We conducted two independent searches of the literature describing HIV incidence among MSM in the United States and Canada, Western Europe and Australia and New Zealand. To conduct each search we used four computerized search engines (Google Scholar, Pub Med, Index Medicus and Ovid) using the search terms MSM, gay men, HIV incidence, AIDS incidence and all combinations of these terms. Reference lists of papers that fell in the scope of the search were searched for relevant candidate publications to include in this analysis. We also contacted investigators in the United States and Canada, Western Europe and Australia and New Zealand to ask if unpublished incidence estimates existed in their geographic region of the world, and if so, to allow us to report these estimates as part of this analysis. Candidate publications identified by the two independent literature searches were compared and a final list of papers that fit the scope of the literature search was defined.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

The entry criteria for the search included publications describing HIV incidence data among MSM populations from 1995 to 2005 in Western Europe, North America or Australia/New Zealand. Publications could also describe incidence rates among non-MSM populations, but needed to include an estimate of incidence among MSM in that report to be included in the list of papers summarized in this analysis. Some reports described incidence estimates for both prior to and after 1995 (Buchbinder et al. 1996; Calzavara et al. 2002; CDC 2001; del Romero et al. 2001; Dukers et al. 2007; Giuliani et al. 2005; Hurtado et al. 2007; Scheer et al. 1999; SMASH 1999; Suligoi et al. 1999; Weinstock et al. 1998, 2002). Reports for which most of the incidence data appear to have been collected after 1995 were included in this review (CDC 2001; del Romero et al. 2001; Hurtado et al. 2007; SMASH 1999; Suligoi et al. 1999); reports for which the majority of the incidence data appear to have been collected prior to 1995 were excluded (Buchbinder et al. 1996; Dukers et al. 2007; Scheer et al. 1999; Weinstock et al. 1998, 2002).

Our search of the literature was guided by the need to identify annual estimates of HIV incidence with sample sizes that would permit the calculation of mean incidence rates and confidence intervals for these estimates. Publications resulting from studies that were designed to examine the effect of an important co-factor for incident HIV infections such as a concurrent STI infection were excluded from the literature (e.g. CDC 2004; Taylor et al. 2005). Also excluded were studies that used HIV incidence measures to determine the effects of HIV prevention interventions (e.g. Bartholow et al. 2006; The Explore Study Team 2004; Koblin et al. 2006) since these interventions may have influenced HIV seroincidence estimates within the studied cohorts. Finally, 12 other papers were excluded because the authors did not report sample size per year or an annualized incidence rate (Calzavara et al. 2002; Craib et al. 2000; Dufour et al. 1998; Giuliani et al. 2005; Hogg et al. 2001; Mackellar et al. 2006; Major et al. 1998; Public Health—Seattle & King County 2005; Remis et al. 2002; Strathdee et al. 2000; van der Snoek et al. 2006; Weinstock et al. 2002).

Although we are using the phrase “MSM”, or men who have sex with men, to describe the findings of this analysis, the data collected within the broader literature appear to have been drawn from a wide range of men with varying social identities related to their sexual and/or relationship practices with other men. We are using the term MSM for this analysis as it is the most inclusive term to describe this population and do not mean to imply that the men who participated in the body of research described in this paper would necessarily identify as “MSM”. Most of the participants in the studies reported here would probably identify as gay men. This review excluded incidence estimates for transgender populations (e.g. Kellogg et al. 2001a) as well as estimates based on samples of MSM injection drug users (e.g. Kral et al. 2003).

HIV incidence was detected in three ways within this literature and all methods were included in this review (see Branson 2007 for an overview of HIV testing methods). The first of these methods relies on longitudinal test/retest methods using standard EIA/Western Blot assays to test for HIV antibody. The second method of incidence ascertainment was through use of the STARHS assay, which can be used to generate HIV incidence rates within samples of individuals who are undergoing HIV testing either in cross-sectional surveys or voluntary counseling and testing sites (Janssen et al. 1998). The third method used to determine recent HIV infection, and serve as the basis of HIV incidence estimates, was through use of nucleic acid amplification screening (Pilcher et al. 2005).

Papers were screened to exclude multiple reporting of HIV incidence rates. Buchbinder et al. (2005) and Seage et al. (2001) report the same seroincidence estimates for MSM in the HIVNET study; only the Buchbinder et al. (2005) paper was included in the analysis reported here. Because the literature reporting HIV incidence rates at testing sites in San Francisco is complex due to partially overlapping study populations and changes in methodology over time, one of the co-authors of this paper (WM) conducted a separate analysis to provide unified HIV incidence rate estimates in San Francisco by year and sampling frame with confidence intervals as a personal communication to supersede the published literature summarizing incidence estimates on MSM at anonymous testing sites and the STD clinics in that city so far (Buchacz et al. 2005; CDC 2004; Fernyak et al. 2002; Katz et al. 2002; Kellogg et al. 2001b; McFarland et al. 1997, 1999; Schwarcz et al. 2001; Truong et al. 2006). These estimates are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of 24 studies of HIV incidence among MSM

| Source | Study dates | Location | HIV incidence detection method | Sample population | Continent of study | Na | HIV incidence estimates by yearb | 95% confidence intervals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buchbinder et al. (2005) | April 1995–May 1997 | Boston, MA, Chicago, IL, Denver, CO, New York, NY, San Francisco, CA and Seattle, WA | HIV + test after recent HIV-test | Community based | North America | 3,257 | 1.55 PY per year | 1.23–1.95 |

| CDC (2001) | 1994–2000 (incidence estimates from 1994 to 1998) | Baltimore, MD, Dallas, TX, Los Angeles, CA, Miami, FL, New York, NY, San Francisco, CA, and Seattle, WA | STARHS | Community based | North America | 3,449 | By city, per year | |

| Baltimore 0.8 (n = 352) | 0.0–6.0 | |||||||

| Dallas 3.3 (n = 523) | 0.9–8.9 | |||||||

| Los Angeles 2.9 (n = 506) | 0.7–8.4 | |||||||

| Miami 0.7 (n = 484) | 0.0–4.5 | |||||||

| New York 7.6 (n = 530) | 3.3–15.8 | |||||||

| San Francisco 1.2 (n = 690) | 0.2–4.5 | |||||||

| Seattle 0.7 (n = 364) | 0.0–5.3 | |||||||

| San Francisco data (McFarland et al.) | 1998–2006 | San Francisco, CA | STARHS | HIV test site | North America | 17,714 | 1998—1.94 (n = 2,180) | 0.9–3.69 |

| 1999—4.06 (n = 1,431) | 2.01–7.09 | |||||||

| 2000—2.93 (n = 1,804) | 1.42–5.24 | |||||||

| 2001—2.84 (n = 1,531) | 1.31–5.35 | |||||||

| 2002—2.81 (n = 1,626) | 1.31–5.2 | |||||||

| 2003—1.67 (n = 1,611) | 0.65–3.57 | |||||||

| 2004—3.19 (n = 1,607) | 1.52–5.72 | |||||||

| 2005—2.23 (n = 2,709) | 1.15–3.9 | |||||||

| 2006—2.36 (n = 3,233) | 1.29–3.94 | |||||||

| San Francisco data (McFarland et al.) | 1998–2006 | San Francisco, CA | STARHS | STD clinic | North America | 14,639 | 1998—4.81 (n = 1,023) | 1.89–7.72 |

| 1999—4.93 (n = 1,105) | 2.25–8.27 | |||||||

| 2000—3.37 (n = 1,556) | 1.6–5.88 | |||||||

| 2001—3.22 (n = 1,415) | 1.46–5.8 | |||||||

| 2002—4.51 (n = 1,614) | 2.34–7.37 | |||||||

| 2003—3.92 (n = 1,900) | 2.06–6.41 | |||||||

| 2004—4.24 (n = 2,032) | 2.37–6.88 | |||||||

| 2005—4.12 (n = 1,889) | 2.23–6.77 | |||||||

| 2006—2.70 (n = 2,105) | 1.38–4.78 | |||||||

| CDC (2005) | June 2004– April 2005 | Baltimore, MD, Los Angeles, CA, Miami, FL, NY, NY, and San Francisco, CA | STARHS | Community based | North America | 1767 | By city | |

| Baltimore 8.0 (n = 462) | 4.2–11.8 | |||||||

| Los Angeles 1.4 (n = 382) | 0.0–2.9 | |||||||

| Miami 2.6 (n = 222) | 0.0–5.6 | |||||||

| New York City 2.3 (n = 336) | 0.28–4.2 | |||||||

| San Francisco 1.2 (n = 365) | 0.0–2.6 | |||||||

| Choi et al. (2004) | 2000–2001 | San Francisco, CA | STARHS | Community based | North America | 496 | 1.8 per year | 0.3–6.5 |

| del Romero et al. (2001) | 1988–2000 | Madrid, Spain | HIV + test after recent HIV-test | HIV test site | Europe | 2,670 = 8,050 PY | 1995—1.06 (n = 977 PY) | NR |

| 1996—1.16 (n = 952 PY) | ||||||||

| 1997—1.67 (n = 904 PY) | ||||||||

| 1998—1.71 (n = 815 PY) | ||||||||

| 1999—1.97 (n = 664 PY) | ||||||||

| 2000—2.16 (n = 324 PY) | ||||||||

| Dougan et al. (2007) | 1997–2004 | England, Wales and Northern Ireland, UK | STARHS | STD clinic | Europe | 5,997 in 1997 | 1997—2.4 (n = 5,997) | 1.5–4.0 |

| 7,234 in 2004 | 2004—3.0 (n = 7,234) | 1.9–4.6 | ||||||

| Dukers et al. (2002) | 1991–2001 | Amsterdam, The Netherlands | STARHS | STD clinic | Europe | 3,090 | 1995—0.9 PY (n = 285) | 0.0–6.0 |

| 1996—4.0 PY (n = 303) | 1.0–11.1 | |||||||

| 1997—5.4 PY (n = 263) | 1.5–13.9 | |||||||

| 1998—1.6 PY (n = 314) | 0.1–6.7 | |||||||

| 1999—3.7 PY (n = 331) | 0.9–10.0 | |||||||

| 2000—5.2 PY (n = 340) | 1.6–12.5 | |||||||

| 2001—4.4 PY (n = 348) | 1.2–11.0 | |||||||

| Elford et al. (2001) | Sep 1997–July 1998 | London, UK | HIV + test after recent HIV-test | HIV test site | Europe | 275 | 1.8 PY | 0.9–3.2 |

| A. Fogarty et al. (2006), (unpublished data) | June 2001–Dec 2005 | Sydney, NSW | HIV + test after recent HIV-test | Community based | Australia | 4,720.6 PY | 2001—0.00 (n = 116.4 PY) | N/A |

| 2002—1.66 (n = 723.0 PY) | 0.86–2.88 | |||||||

| 2003—0.71 (n = 1,127.5 PY) | 0.31–1.39 | |||||||

| 2004—1.03 (n = 1,363.8 PY) | 0.56–1.72 | |||||||

| 2005—0.58 (n = 1,389.8 PY) | 0.25–1.13 | |||||||

| Hurtado et al. (2007) | 1988–2003 | Valencia, Spain | HIV + test after recent HIV-test | HIV test site | Europe | 2,831 | 1995—1.64 (n = 517) | 0.8–3.4 |

| 1996—1.36 (n = 531) | 0.6–3.0 | |||||||

| 1997—0.45 (n = 546) | 0.1–1.8 | |||||||

| 1998—0.49 (n = 497) | 0.1–2.0 | |||||||

| 1999—1.58 (n = 428) | 0.7–3.5 | |||||||

| 2000—1.41 (n = 413) | 0.6–3.4 | |||||||

| 2001—1.51 (n = 411) | 0.6–3.6 | |||||||

| 2002—1.91 (n = 362) | 0.8–4.6 | |||||||

| 2003—3.28 (n = 239) | 1.2–8.7 | |||||||

| Jin et al. (2008) | 2002–2006 | Sydney, NSW | HIV + test after recent HIV-test | Community based | Australia | 1,426 = 5,948.6 PY | 0.87 PY | 0.65–1.14 |

| Lampinen et al. (2005) | 1997–2003 | Vancouver, Canada | HIV + test after recent HIV-test | Community based | North America | 247 | 1997—0.56 (n = 179.2 PY) | 0–1.65 |

| 1998—0.96 (n = 208.4 PY) | 0–2.29 | |||||||

| 1999—0.86 (n = 233.5 PY) | 0–2.04 | |||||||

| 2000—0.42 (n = 237.8 PY) | 0–1.24 | |||||||

| 2001—0.43 (n = 232.3 PY) | 0–1.27 | |||||||

| 2002—1.53 (n = 196.7 PY) | 0–3.25 | |||||||

| 2003—2.36 (n = 84.9 PY) | 0–5.62 | |||||||

| Lavoie et al. (2008) | 1996–2003 | Montreal, Canada | HIV + test after recent HIV-test | Community based | North America | 1,587 = 5,121 PY | 0.62 PY | 0.41–0.84 |

| Mehta et al. (2006) | 1993–2002 | Baltimore, MD | HIV + test after recent HIV-test | STD clinic | North America | 100 = 127 PY | 3.14 PY | 0.86–7.87 |

| Murphy et al. (2004) | 1995–2001 | United Kingdom | STARHS | STD clinic | Europe | 43,100 | 1995—3.00 (n = 5922) | 1.87–4.82 |

| 1996—3.29 (n = 5,670) | 2.06–5.23 | |||||||

| 1997—2.43 (n = 5,910) | 1.45–4.02 | |||||||

| 1998—2.33 (n = 6,153) | 1.39–3.86 | |||||||

| 1999—1.46 (n = 5,776) | 0.77–2.66 | |||||||

| 2000—2.41 (n = 5,224) | 1.55–3.58 | |||||||

| 2001—2.45 (n = 6,684) | 1.66–3.5 | |||||||

| Nascimento et al. (2004) | 1995–2001 | Catalonia, Spain | HIV + test after recent HIV-test | HIV test site | Europe | 675 = 1,144 PY | 1.95 PY | 1.21–2.90 |

| Nash et al. (2005) | 2001 | New York, NY | STARHS | Community based | North America | 4,750 | 2.5 | 2.1–2.8 |

| Pilcher et al. (2005) | Nov 2002–Oct 2003 | North Carolina | STARHS | HIV test site | North America | 3,777 | 2.14 PY | 1.56–2.88 |

| Remis et al. (2000) | Oct 1999–May 2000 | Ontario, Canada | STARHS | HIV test site | North America | 8,082 | 2.7 PY | NR |

| SMASH study team (1999) | 1993–1998 | Sydney, NSW | HIV + test after recent HIV-test | Community based | Australia | 2,215.4 PY | 1995—1.7 (n = 526.0 PY) | 0.8–3.2 |

| 1996—1.1 (n = 460.6 PY) | 0.4–2.5 | |||||||

| 1997—1.0 (n = 307.1 PY) | 0.2–2.8 | |||||||

| 1998—0.0 (n = 71.9 PY) | N/A | |||||||

| Suligoi et al. (1999) | 1991–1996 | Italy | HIV + test after recent HIV-test | STD clinic | Europe | 337 = 453.1 PY | 1995—2.6 PY | NR |

| Tabet et al. (1998) | 1995 | Seattle, WA | HIV + test after recent HIV-test | Community based | North America | 578 | 1.3 PY | NR |

STARHS serological testing algorithm for recent HIV seroconversion, STD sexually transmitted disease, NR not reported

PY = person years of follow-up;

PY = per 100 person years of follow-up

Approach to the Data Analysis

Overall and within each subgroup (i.e. community, based, HIV test site, STD treatment samples or across regions), unweighted average incidence rates were estimated. To account for the different sizes of the individual studies, weighted average incidence rates were calculated overall and within each subgroup using a fixed-effects model (van den Noortgate and Onghena 2005). As a measure of precision of the weighted average incidence rates, 95% confidence intervals were calculated.

From each of the individual publications we coded several characteristics of specific incidence estimates among MSM populations. Among these were the year of each incidence estimate, the continent (i.e. North America, Europe and Australia/New Zealand) from which the data were generated, the type of incidence approach used to generate the estimate, the sampling method used to recruit MSM for incidence testing (i.e. community-based samples, samples from HIV testing centers or STI clinic samples). Comparisons were made across these stratifying variables to test for differences in HIV incidence.

Using the mean seroincidence rate calculated from the US community-based literature, we projected expected prevalence rates with a conceptual closed cohort of young MSM, emphasizing expected HIV prevalence rates to the age of 40. The cohort of men would be closed in the epidemiological sense only (i.e. a defined cohort whose n is set through time) and would have normal contact within the 123 broader gay communities. If Pn is prevalence at age n, In is incidence at age n, MRn is the general age-specific mortality rate at age n, HIVMRn is the age-specific HIV mortality rate at age n, and CRn is the disease remission rate at age n, HIV prevalence at age n + 1, Pn+1, can be calculated stepwise by using the formula

Under the assumptions that HIV incidence (In) is constant to age 40, that there is no HIV disease remission (i.e. CRn = 0) and that both general mortality rates (MRn) and HIV-specific mortality rates (HIVMRn) are negligible in this age group in the HAART era relative to Pn, the formula reduces to

We will address limitations of these simplifications in the “Discussion”.

In theory, the prevalence at any age should be corrected by additional terms that adjust for background age-specific mortality rates as well as mortality rates for HIV, and the incidence rate itself should be adjusted with the assumption that sexual activity decreases over the lifespan. In practice, these adjustments changed the model very little prior to age 60, certainly staying within the calculated confidence limits. It should be noted that this model gives the prevalence of the total burden of HIV-related disease (i.e. from HIV infection through death), which even in an era of widespread HAART medication use is likely to contain some proportion of men who are suffering the effects of HIV morbidity or who are already deceased within an age cohort. As such the prevalence extrapolations reported here might be expected to be somewhat higher than prevalence rates generated from community-based samples, since sick or deceased men would be less likely to be sampled within such venues than would healthy men who remain in the cohort.

Results

Table 1 summarizes the main findings of the publications and estimates contributed via personal communications identified in the literature search by research design characteristics, continent of country where the study was conducted, year(s) in which the incidence data were collected, incidence rates and 95% confidence intervals for these rates, if reported. Twenty-four separate studies reporting incidence estimates from Europe, North America or Australia from 1995 to 2005 are described in Table 1. Many of these papers report incidence estimates for multiple years within MSM samples, thus these studies as a group give 89 annualized estimates for incidence of HIV infection within MSM communities in industrialized countries. Incidence rates with confidence intervals were given for 78 annualized estimates in these reports. Estimates of the mean incidence rates from the literature given in this paper were restricted to those reports that also gave confidence intervals.

What are the Recent Incidence Rates Among MSM Residents of Industrialized Nations?

We calculated mean incidence estimates with confidence by type of testing site, by continent, and by calendar year from the reported literature. These estimates are given in Table 2, and yielded a combined overall weighted incidence estimate among MSM of 2.5% per year. Statistically significant differences were determined by examining whether confidence intervals for these estimates overlapped. Notably, we found differences across these stratifications by type of HIV testing site and continent, as well as differences by testing sites within North America and Europe. No differences were found to exist by calendar year. These findings can be interpreted to mean that community-based samples yielded lower HIV incidence rates than those found in STD clinic samples. These general findings were reproduced in both the European and North American sub-analyses. European HIV test site samples yielded lower incidence rates than did European STD clinic samples and North American community-based and HIV clinic samples yielded lower HIV incidence rates than those estimated for North American STD clinic samples. Finally, while this literature does provides evidence to demonstrate that HIV incidence rates are lower in Australia than in Europe or the United States, the literature as a whole does not support assertions that HIV incidence rates are rising or falling among MSM from 1995 to 2005.

Table 2.

HIV incidence estimates among MSM residents of industrialized countries, 1995–2006 by recruitment setting, continent and year

| N | Incidence estimate

|

95% confidence interval | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted estimate | Weighted estimate | ||||

| Overall | 75 | 2.383 | 2.525 | 2.344 | 2.591 |

| Recruitment setting | |||||

| Community | 30 | 1.811 | 1.835 | 1.690 | 1.979 |

| HIV | 20 | 2.308 | 2.269 | 1.966 | 2.573 |

| STD | 25 | 3.347 | 2.833 | 2.375 | 3.138 |

| Continent | |||||

| Australia | 8 | 1.081 | 0.978 | 0.770 | 1.185 |

| Europe | 26 | 2.438 | 2.500 | 2.142 | 2.858 |

| North America | 41 | 2.602 | 2.787 | 2.498 | 2.838 |

| Continent and recruitment setting | |||||

| Australia, community | 8 | 1.081 | 0.978 | 0.770 | 1.185 |

| Europe, HIV | 10 | 1.543 | 1.401 | 0.834 | 1.967 |

| Europe, STD | 16 | 2.998 | 2.582 | 2.120 | 3.044 |

| North America, community | 22 | 2.070 | 2.250 | 2.049 | 2.452 |

| North America, HIV | 10 | 2.533 | 2.450 | 2.091 | 2.810 |

| North America, STD | 9 | 3.967 | 3.863 | 3.166 | 4.520 |

| Year | |||||

| 1995 | 4 | 1.810 | 2.726 | 1.776 | 3.676 |

| 1996 | 12 | 2.375 | 2.565 | 2.206 | 2.925 |

| 1997 | 6 | 2.040 | 2.335 | 1.702 | 2.968 |

| 1998 | 7 | 1.983 | 2.270 | 1.779 | 2.762 |

| 1999 | 6 | 3.871 | 2.314 | 1.646 | 2.982 |

| 2000 | 6 | 2.573 | 2.624 | 2.088 | 3.161 |

| 2001 | 7 | 2.370 | 2.558 | 2.297 | 2.819 |

| 2002 | 5 | 2.406 | 2.967 | 2.234 | 3.701 |

| 2003 | 6 | 2.398 | 2.272 | 1.803 | 2.740 |

| 2004 | 11 | 2.636 | 2.820 | 2.584 | 3.056 |

| 2005 | 3 | 1.303 | 2.421 | 1.908 | 2.934 |

| 2006 | 2 | 2.530 | 2.566 | 1.304 | 3.829 |

Although not given separately in Table 2, the mean weighted incidence rates for studies from the United States were 2.39 (95% CI, 2.16, 2.62) for community based studies, 2.45 (95% CI, 2.09, 2.81) for HIV alternative test site studies and 3.84 (95% CI, 3.17, 4.52) for STI treatment clinic studies.

Given These Incidence Rates, What Will the Prevalence of HIV Infection be Over Time Within New Cohorts of Urban MSM?

We next turned to the question of what these incidence estimates would yield, if sustained over time, in terms of HIV prevalence across the life course within a new cohort of young gay men just entering their adult years. The prevalence extrapolations are presented here only as a thought experiment to help illustrate what current incidence rates reported for gay men might yield over time so that the potential implications of these incidence rates can be better interpreted. The model that we are using is purposively simple, since many of the estimates that might be used in a more sophisticated model (i.e. incidence rates across age grades and cohorts, across all ethnic groups, for men with varying levels of sexual mixing) are not currently available in the literature. Nonetheless, the very crude prevalence extrapolations presented here may provide some guide as to what prevalence levels may result given current HIV incidence rates reported in the published epidemiological literature.

The prevalence extrapolations are described for the United States case only since they can be compared to a report from the CDC giving estimates for HIV prevalence rates derived from a large-scale, community-based sample of MSM (i.e. CDC 2005). An extrapolation for African American MSM will also be given to show how expected rates of HIV infection might differ among a group of men at very high vulnerability to HIV infection.

Consistently conservative measures of HIV incidence and prevalence at age 20 were used to estimate the HIV prevalence rates that might be expected in a new cohort of young MSM in the United States. That is, the community-based estimate of HIV incidence was used for MSM in the United States (i.e. 2.39%) as opposed to higher incidence estimates generated through HIV test site or STD clinic based samples. HIV incidence for African American MSM was based on the lower of two separate seroincidence estimates published by the CDC for African American MSM (i.e. 4.0% CDC 2001). To estimate prevalence estimates for the general population of MSM in the United States, we assumed a 0% prevalence rate at age 18 among MSM, and 2.39% incidence per year until age 20, yielding an HIV prevalence rate just under 5% at age 20. This estimate is probably at the low end of the range that might be expected from a recent CDC prevalence report of HIV prevalence among MSM in five American cities (i.e. HIV prevalence among MSM aged 18–24 at 14%, CDC 2005).

Table 3 shows that using these prevalence and incidence estimates within a cohort of young men now 20 years of age, the total burden of HIV disease would be estimated to be 25.4% by the time that they reach the age of 30 (95% CI 23.6, 27.1%), 41.4% at age 40 (95% CI 38.6, 44.1%) and 54.0% at age 50 (95% CI 50.6, 57.1%). To provide a similar projection for African American men, we also assumed a 0% HIV prevalence rate at age 18, but used an annual incidence rate of 4% to yield expected prevalence estimates for HIV disease burden across the life span. Among African American MSM the model predicts that 7.8% of African American MSM will be HIV positive by age 20, 38.7% at age 30 and 59.3% by age 40.

Table 3.

Expected prevalence rates of HIV infection within a cohort of young MSM who are seronegative at age 18; 2.39% annual incidence rate for the general population of MSM; 4% incidence rate for African American MSM

| Age | General population of MSM | African American MSM |

|---|---|---|

| 20 | 4.7% (95% CI: 4.3, 5.2) | 7.8% (95% CI: 2.3,18.8) |

| 25 | 15.6% (95% CI: 14.2, 16.9) | 24.9% (95% CI: 8.8, 51,8) |

| 30 | 25.2% (95% CI: 23.0, 27.3) | 38.7% (95% CI: 14.5, 71.4) |

| 35 | 33.7% (95% CI: 31.0, 36.3) | 50.0% (95% CI: 19.9, 83.0) |

| 40 | 41.2% (95% CI: 38.1, 44.2) | 59.3% (95% CI: 25.0, 90.0) |

To What Extent do These Projections of HIV Prevalence Within a Cohort Over Time Match HIV Seroprevalence Estimates for MSM Under the Age of 40?

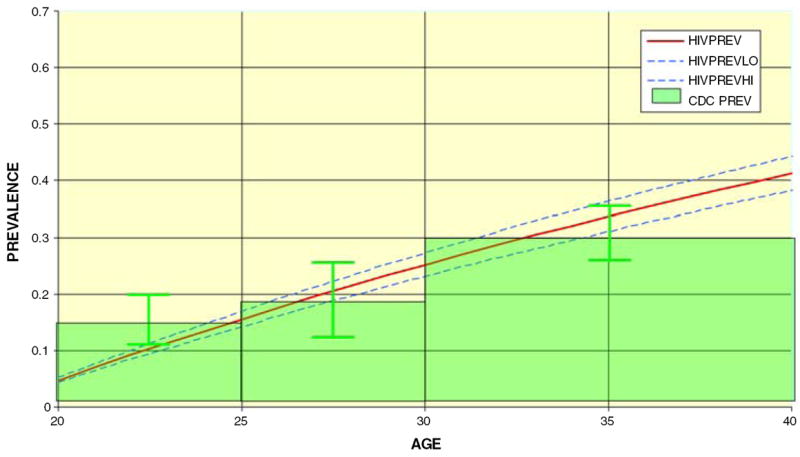

We then turned to the question of whether these HIV disease prevalence illustrative extrapolations are comparable to current seroprevalence estimates among MSM in the United States by comparing our prevalence extrapolations to recent measures of HIV prevalence among MSM. We restricted these comparisons to men under the age of 40, as these men would have been, by definition, younger than 15 when the AIDS epidemic was first discovered some 25 years ago. Thus, these men are unlikely to have been HIV infected before the discovery of the AIDS epidemic, would have lived the majority of their adult lives within the background seroincidence context described in this paper, and are unlikely to have suffered substantial HIV-related mortality experienced by the generations of MSM older than 40. Again, we used the largest current data set reporting HIV seroprevalence rates by age among MSM currently available in the United States (CDC 2005) to make comparisons with the seroprevalence extrapolations reported in Table 3. CDC (2005) reports that the prevalence of HIV infection among MSM aged 18–24 is 14%; from 25 to 29 the prevalence of HIV infection is 17%; from 30 to 39 the prevalence of HIV infection is 29%. Figure 1 shows that the estimates and confidence intervals for the HIV disease prevalence extrapolations estimated in this paper overlap the prevalence estimates reported by the CDC for MSM between the ages of 25 and 40. This finding can be interpreted to mean that the projections reported in this paper describe reasonably well the course of the AIDS epidemic as it is currently being experienced by MSM in the United States under the age of 40.

Fig. 1.

HIV prevalence by age US MSM community samples, HIV incidence at 2.39% (extracted from CDC 2005)

Discussion

The current question that dominates discussions of HIV incidence among MSM is whether infection rates are rising. This analysis suggests that a more useful discussion might be to estimate what current incidence rates will yield over time, and then to begin the discussion to define how best to lower HIV incidence rates among gay men. This analysis found that HIV incidence rates did not significantly increase or decrease among MSM during the decade from 1995 to 2006. However, at a 2.39% annual incidence rate within a cohort of young men uninfected at age 18, approximately 41% of these men would be HIV seropositive by age 40. These estimated prevalence rates should give us pause, as they are higher than those reported for sub-Saharan countries generally acknowledged to be in the grip of an AIDS crisis so severe that an unprecedented level of internationally-based public health assistance has been given to control the epidemic in these countries (UNAIDS 2007). Perhaps even more sobering, a projected HIV prevalence rate of 41% at age 40 is not much lower than the prevalence rate reported for the household-based San Francisco Men’s Health study in 1984, prior to the fielding of any formal AIDS prevention work among gay men in that city (48.5% within a sample of men aged 25–54, Winkelstein et al. 1987).

The projections reported here—and those estimated earlier in the AIDS epidemic (Hoover et al. 1991)—suggest that incidence estimates in the 2–3% range will adversely affect the health of gay male communities for decades to come. The stability of HIV incidence rates from 1995 to 2005 suggests that very high prevalence rates of HIV are being reproduced across new generations of gay men, and that conclusion is almost certainly true among African American MSM. Furthermore, the mean incidence estimates calculated for the United States are based on data collected in many different American cities, which suggests that the incidence estimates described here reflect a widespread epidemiological phenomenon, at least within urban settings. Finally, comparisons of the HIV seroprevalence projections reported in this analysis with MSM currently under the age of 40 suggest that this analysis should not be regarded as one that is only predicting events that may happen at some point in the future. We are describing phenomena that are currently unfolding around us. Thus, this analysis suggests that in terms our effectiveness in the fight against AIDS among MSM in the United States, we are currently running in place.

This analysis has several important limitations that should be acknowledged. First, it is based on a review of published incidence estimates for MSM in industrialized “Western” countries and cannot be generalized to MSM who reside in developing world settings. Nor can these estimates be back-generalized to any one city. To the extent that all incidence rates for MSM have not been published, or that there is a differential interest in publishing elevated incidence rates, the mean incidence estimates reported in this analysis would be biased. We could find no evidence to suggest that any country had designed a surveillance system to yield representative national incidence estimates for MSM from the period from 1995 to 2006. Rather, the reporting of seroincidence estimates in this literature seems to be heavily weighted towards the reporting of data from very large cities. To the extent that the literature omits the reporting of seroincidence estimates for rural, suburban or MSM residents of secondary urban centers, the incidence estimates reported in this literature are likely to be biased. Since all of the incidence estimates reported in this literature are for populations of urban MSM, these findings should not be generalized to rural or suburban MSM populations.

The projections reported in this analysis were presented only as illustrations of what current HIV incidence rates would yield over time, and are subject to a set of limitations of their own. First, these assumptions are based on the assumption that the background HIV incidence rate for cohorts of MSM is stable from youth to age 40. However, to the extent that MSM move from low incidence to higher incidence contexts (i.e. from rural to urban settings) or the reverse (from urban to rural settings) as they age, this assumption is likely to be flawed. Similarly, if levels of risk-taking change across the life course (with, say, younger men being at higher risk), these projections could be biased. However, it should also be noted that we re-ran the prevalence projections under assumptions of higher incidence rates among men in their 20s and lower in their 30s and 40s, but yielded comparable prevalence estimates by age 40 to those presented in this paper (see also Hoover et al. 1991). Specifically, we modified the extrapolation presented here assuming that men would have 1/3 higher incidence of HIV in before the age of 30 than they do in their thirties, and 1/3 lower incidence of HIV after the age of 40. This modification yielded estimated point prevalence of HIV of 32.2% at age 30, 46.7% at age 40, and 53.9% at age 50. At no point during the ages of interest addressed in this study (ages 20–40) was the modified point prevalence less than the upper confidence interval reported for the extrapolation that assumed a constant incidence rate from age 20 to 40.

Finally, it should be pointed out that the prevalence extrapolations reported here are for the total burden of HIV disease, including mortality. Thus, the extrapolations reported here are likely to be higher than prevalence rates generated through cross-sectional venue-based sampling of MSM (e.g. CDC 2005), as cross-sectional venue-based sampling would not be the method of choice to sample deceased (by definition) or infirm men. Any one of the possible biases noted above—or a combination of these biases operating in tandem—is likely to bias the prevalence or incidence estimates reported in this paper in unknown ways. That said, the comparison of HIV prevalence projections with actual rates published for American MSM lends some confidence that these projections are reasonably accurate, at least for the case of gay male residents of large urban centers in the United States.

This analysis highlights the importance of finding ways to lower incidence rates among MSM to levels beneath those that could be expected to reproduce the AIDS epidemic across age cohorts. Many recommendations to improve AIDS prevention efforts among MSM have already been suggested in the literature. A limited number of recommendations that can be based directly on this analysis will be mentioned here. Certainly a first step would include significant improvement in the quality of HIV prevention programs among MSM. The analysis presented in this paper has emphasized the implications of the fact that the period of seroconversion risk for sexually-active MSM can extend for decades across the life course. As it is unlikely that the risks for HIV transmission are driven by the same mix of factors for men in their 20s, 30s, 40s, 50s and later, developing age-appropriate AIDS prevention strategies for men across the life course may work to improve HIV prevention practice for this population. Ensuring that these programs have the policy and funding support necessary to achieve the goal of lowering HIV incidence rates among gay men would also be an important step forward. Both of these needs are especially important among MSM sub-populations that are characterized by very high HIV incidence rates, such as African American MSM and substance abusing MSM.

Additional thought also needs to be devoted to how HIV surveillance programs might be better used to support the goal of lowering HIV incidence rates among gay men. Such progress could be made through the design of surveillance programs that would yield representative prevalence and incidence data for MSM communities not only for cross-sectional samples, but also across time. The many sources by which published incidence rates for MSM might be biased have been reviewed above. To the extent that these published rates can be demonstrated to be biased, additional evidence is provided for the need to construct surveillance systems that provide accurate measures of HIV incidence rates among gay men to guide prevention efforts. In addition, design of a surveillance system that could be used to generate data about the characteristics of men who have recently seroconverted would yield important data that might be used to inform, and improve, current HIV prevention practice among MSM. By studying the characteristics of MSM who become newly infected with HIV it should be possible to identify not only the characteristics of men most vulnerable to infection, but also the social and environmental contexts and sexual strategies that are associated with highest risk of HIV transmission. These analyses could be used to adapt HIV prevention practice to reach men at greatest actual risk of HIV infection and to address the individual characteristics, social contexts and sexual strategies associated with greatest vulnerability to HIV infection. In this manner, a well-designed HIV seroprevalence system might be used to not only generate estimates of HIV prevalence and incidence, but also to provide important guidance towards ending ongoing HIV infections among MSM.

It may seem highly optimistic to end this paper with recommendations on how to improve HIV prevention practice for MSM, as substantial energy and resources within the gay male community and non-governmental and governmental public health organizations have already been devoted to meet this goal over the past 25 years. Some observers may conclude that efforts to prevent HIV transmission among MSM are unlikely to yield important public health outcomes and are, in the end, a waste of time and effort. While it is possible to argue for a position that supports HIV prevention nihilism, such arguments cannot be supported using the incidence data reported in this paper. Under the same approach underlying the prevalence projections generated for the United States (i.e. assuming a prevalence rate of 0% within a cohort of MSM aged 20) and using the weighted incidence estimate for community-based samples of Australian MSM (1%), prevalence rates for HIV infection among Australian MSM would be 2% (95% CI 1.3, 2.6) at age 20, 11.4% (95% CI 7.9%, 14.8) at age 30 and 19.5% (95% CI 13.9, 25.5) at age 40. In short, expected HIV prevalence rates in the Australian case are roughly half those calculated for US MSM by age 40. While such facile comparisons ignore important contextual variables that can drive HIV epidemics at different rates across societies, this difference is so stark that it raises the question of whether it is possible to construct HIV prevention programming and policy to yield far more successful results among gay male communities than have been obtained to date in the United States. Thus, given the very high stakes of the fight against AIDS among MSM, arguments in favor of HIV prevention nihilism should have little attraction in comparison to invitations to help find ways to improve prevention efforts so that the AIDS epidemic will no longer be reproduced across generations of gay men.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants MH080648, “Longitudinal Internet Research Investigating Health Outcomes in Adolescence” (Dr. Friedman), DA022936 “Long Term Health Effects of Methamphetamine Use in the MACS” (Drs. Stall and Guadamuz), AA015100 “Parent Alcoholism Among ADHD Youth: A Longitudinal Study” (Dr. Marshal). This paper is dedicated to the memory of Mr. Hank Wilson, a long-time AIDS activist in San Francisco whose life work was devoted to improving health and well-being among gay men.

Contributor Information

Ron Stall, Email: rstall@pitt.edu, Department of Behavioral and Community Health Sciences, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, 208 Parran Hall 130 DeSoto Street, Pittsburgh, PA 15261, USA.

Luis Duran, Email: lgd2@pitt.edu, Department of Behavioral and Community Health Sciences, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, 208 Parran Hall 130 DeSoto Street, Pittsburgh, PA 15261, USA.

Stephen R. Wisniewski, Email: wisniew@edc.pitt.edu, Department of Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

Mark S. Friedman, Email: msf11@pitt.edu, Department of Behavioral and Community Health Sciences, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, 208 Parran Hall 130 DeSoto Street, Pittsburgh, PA 15261, USA.

Michael P. Marshal, Email: marshalmp@upmc.edu, Department of Behavioral and Community Health Sciences, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, 208 Parran Hall 130 DeSoto Street, Pittsburgh, PA 15261, USA; Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA.

Willi McFarland, Email: willi.mcfarland@sfdph.org, AIDS Office, Department of Public Health, City and County of San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA.

Thomas E. Guadamuz, Email: teg10@pitt.edu, Department of Behavioral and Community Health Sciences, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, 208 Parran Hall 130 DeSoto Street, Pittsburgh, PA 15261, USA.

Thomas C. Mills, Email: tcmills@earthlink.net, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA.

References

- Bartholow BN, Goli V, Ackers M, McLellan E, Gurwith M, Durham M, et al. Demographic and behavioral contextual risk groups among men who have sex with men participating in a Phase 3 HIV vaccine efficacy trial: Implications for HIV prevention and behavioral/biomedical intervention trials. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;43:594–602. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243107.26136.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branson B. State of the art for diagnosis of HIV infection. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2007;45:S221–S225. doi: 10.1086/522541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchacz K, McFarland W, Kellogg TA, Loeb L, Holmberg SD, Dilley J, et al. Amphetamine use is associated with increased HIV incidence among men who have sex with men in San Francisco. AIDS (London, England) 2005;19:1423–1424. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000180794.27896.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchbinder S, Douglas J, McKirnan D, Judson F, Katz M, MacQueen K. Feasibility of Human Immunodeficiency Virus vaccine trials in homosexual men in the United States: Risk behavior seroincidence and willingness to participate. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1996;174:954–961. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.5.954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchbinder S, Vittinghoff E, Heagerty PJ, Celum CL, Seage GR, Judson FN, et al. Sexual risk, nitrite inhalant use, and lack of circumcision associated with HIV seroconversion in men who have sex with men in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2005;39:82–89. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000134740.41585.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzavara L, Burchell AN, Major C, Remis RS, Corey P, Myers T, Millson P, Wallace E Polaris Study Team. Increases in HIV incidence among men who have sex with men undergoing repeat diagnostic HIV testing in Ontario, Canada. AIDS (London, England) 2002;16:1655–1661. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200208160-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. HIV incidence among young men who have sex with men—seven US cities, 1994–2000. MMWR. 2001;50:440–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. Trends in primary and secondary syphilis and HIV infections in men who have sex with men—San Francisco and Los Angeles, California, 1998–2002. MMWR. 2004;53:575–578. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. HIV prevalence, unrecognized infection, and HIV testing among men who have sex with men—five US cities, June 2004–April 2005. MMWR. 2005;54:597–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. Primary and secondary syphilis—United States, 2003–2004. MMWR. 2006;55(10):269–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K, McFarland W, Neilands TB, Nguyen S, Louie B, Secura GM, et al. An opportunity for prevention: Prevalence, incidence, and sexual risk for HIV among young Asian and Pacific Islander men who have sex with men, San Francisco. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2004;31:475–480. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000135988.19969.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craib K, Weber A, Cornelisse P, Martindale S, Miller J, Schecter M, et al. Comparison of sexual behaviors, unprotected sex and substance use between two independent cohorts of gay and bisexual men. AIDS (London, England) 2000;14:303–311. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200002180-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Romero J, Castilla J, Garcia S, Clavo P, Ballesteros J, Rodriguez C. Time trend in incidence of HIV seroconversion among homosexual men repeatedly tested in Madrid, 1988–2000. AIDS (London, England) 2001;15:1319–1321. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200107060-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougan S, Elford J, Chadborn T, Brown AE, Roy K, Murphy G, et al. Does the recent increase in HIV diagnoses among men who have sex with men in the United Kingdom reflect a rise in HIV incidence or increased uptake of HIV testing? Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2007;83:120–125. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.021428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour A, Parent R, Alary M, Otis J, Remis R, Mâsse B, Lavoie R, LeClerc R, Turmel G, Vincelette J Omega Study Group. Characteristics of young and older men who have affective and sexual relations with men (MASM) in Montreal. Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1998;9(Suppl. A):30A. [Google Scholar]

- Dukers NHTM, Fennema HSA, van der Snoek EM, Krol A, Geskus RB, Pospiech M, et al. HIV incidence and HIV testing behavior in men who have sex with men: Using three incidence sources, The Netherlands, 1984–2005. AIDS (London, England) 2007;21:491–499. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328011dade. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dukers NHTM, Spaargaren J, Geskus RB, Beijnen J, Coutinho RA, Fennema HSA. HIV incidence on the increase among homosexual men attending an Amsterdam sexually transmitted disease clinic: Using a novel approach for detecting recent infections. AIDS (London, England) 2002;16:F19–F24. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200207050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elford J, Leaity S, Lampe F, Wells H, Evans A, Miller R, et al. Incidence of HIV infection among gay men in a London HIV testing clinic, 1997–1998. AIDS (London, England) 2001;15:650–653. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200103300-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernyak SE, Page-Shafer K, Kellogg TA, McFarland W, Katz MH. Risk behaviors and HIV incidence among repeat testers at publicly funded HIV testing sites in San Francisco. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2002;31:63–70. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200209010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliani M, Di Carlo A, Palamara G, Dorrucci M, Latini A, Prignano G, et al. Increased HIV incidence among men who have sex with men in Rome. AIDS (London, England) 2005;19:1429–1431. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000180808.27298.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg RS, Weber AE, Chan K, Martindale S, Cook D, Miller ML, et al. Increasing incidence of HIV infections among young gay and bisexual men in Vancouver. AIDS (London, England) 2001;15:1321–1322. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200107060-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover D, Muñoz A, Carey V, Chmiel J, Taylor J, Margolick J, et al. Estimating the 1978–1990 and future spread of HIV type 1 in subgroups of homosexual men. American Journal of Epidmiology. 1991;134(10):1190–1205. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado I, Alastrue I, Ferreros I, del Amo J, Santos C, Tasa T, et al. Trends in HIV testing, serial HIV prevalence and HIV incidence among people attending a Center for AIDS Prevention from 1988 to 2003. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2007;83:23–28. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.019299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe H, Valdiserri R, DeCock K. The reemerging HIV/AIDS epidemic in men who have sex with men. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298(20):2412–2414. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.20.2412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen R, Satten G, Stramer S, Rawal B, O’Brien T, Weiblen B, et al. New testing strategy to detect early HIV-1 infection for use in incidence estimates and for clinical and prevention purposes. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280(1):42–48. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin F, Prestage GP, McDonald A, Ramacciotti T, Imrie JC, Kippax SC, et al. Trend in HIV incidence in a cohort of homosexual men in Sydney: Data from the Health in Men Study. 2008;5:109–112. doi: 10.1071/sh07073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz MH, Schwarcz SK, Kellogg TA, Klausner JD, Dilley JW, Gibson S, et al. Impact of highly active antiretroviral treatment on HIV seroincidence among men who have sex with men: San Francisco. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:388–394. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.3.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg T, Clements-Nolle K, Dilley J, Katz M, McFarland W. Incidence of human immunodeficiency virus among male-to-female transgenderered persons in San Francisco. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2001a;28(4):380–384. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200112010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg TA, McFarland W, Perlman JL, Weinstock H, Bock S, Katz MH, et al. HIV incidence among repeat HIV testers at a county hospital, San Francisco, California, USA. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2001b;28:59–64. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200109010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblin B, Husnik M, Colfax G, Huang Y, Madison M, Mayer K, et al. Risk factors for HIV infection among men who have sex with men. AIDS (London, England) 2006;20:731–739. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000216374.61442.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kral AH, Lorvick J, Gee L, Bacchetti P, Rawal B, Busch M, et al. Trends in human immunodeficiency virus seroincidence among street-recruited injection drug users in San Francisco, 1987–1998. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;157:915–922. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampinen TM, Ogilvie G, Chan K, Miller ML, Cook D, Schechter MT, et al. Sustained increase in HIV-1 incidence since 2000 among men who have sex with men in British Columbia, Canada. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2005;40:242–244. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000168182.14523.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie E, Alary M, Remis R, Otis J, Vincelette J, Turmel B, et al. Determinants of HIV seroconversion among men who have sex with men living in a low HIV incidence population in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapies. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2008;35(1):25–29. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31814fb113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald N, Dougan S, MacGarrigle C, Baster K, Rice G, Evans G, et al. Recent trends in diagnosis of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in England and Wales among men who have sex with men. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2004;80:492–497. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.011197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackellar D, Valleroy L, Anderson J, Behel S, Secura G, Bingham T, et al. Recent HIV testing among you men who have sex with men: Correlates, contexts and HIV seroconversion. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2006;33(3):183–192. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000204507.21902.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major C, Remis R, Galli R, Wu K, Degazio R, Fearon M. Towards real-time HIV surveillance using HIV testing data. Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1998;9(Suppl. A):40A. [Google Scholar]

- McFarland W, Busch MP, Kellogg TA, Rawal BD, Satten GA, Katz MH, et al. Detection of early HIV infection and estimation of incidence using a sensitive/less-sensitive enzyme immunoassay testing strategy at anonymous counseling and testing sites in San Francisco. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes and Human Retrovirology. 1999;22:484–489. doi: 10.1097/00126334-199912150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland W, Kellogg TA, Dilley J, Katz MH. Estimation of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) seroincidence among repeat anonymous testers in San Francisco. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1997;146:662–664. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta SD, Ghanem KG, Rompalo AM, Erbelding EJ. HIV seroconversion among public sexually transmitted disease clinic patients: Analysis of risks to facilitate early identification. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;42:116–122. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000200662.40215.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy G, Charlett A, Jordan LF, Osner N, Gill ON, Parry JV. HIV incidence appears constant in men who have sex with men despite widespread use of effective antiretroviral therapy. AIDS (London, England) 2004;18:265–272. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200401230-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento CMR, Casado MJ, Casabona J, Ros R, Sierra E, Zaragoza K, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence among repeat anonymous testers in Catalonia, Spain. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2004;20:1145–1147. doi: 10.1089/0889222042544956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash D, Bennani Y, Ramaswamy C, Torian L. Estimates of HIV incidence among persons testing for HIV using the sensitive/less sensitive enzyme immunoassay, New York City, 2001. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2005;39:102–111. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000144446.52141.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New York Times. Editorial: HIV rises among young gay men. New York Times. 2008 Jan 14; [Google Scholar]

- Osmond D, Pollack L, Pual J, Catania J. Changes in prevalence of HIV infection and sexual risk behavior in men who have sex with men in San Francisco: 1997–2002. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(9):1677–1683. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.062851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilcher CD, Fiscus SA, Nguyen TQ, Foust E, Wolf L, Williams D, et al. Detection of acute infections during HIV testing in North Carolina. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;352:1873–1883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health—Seattle & King County. Healthy People, Healthy Communities. (2005). HIV/AIDS Epidemiology Program. [October 25, 2006];Facts about HIV/AIDS in Men who have Sex with Men (MSM) http://www.metrokc.gov/health/apu/epi.

- Remis RS, Alary M, Otis J, Masse B, Demers E, Vincelette J, Turmel B, LeClerc R, Lavoie R, Parent R, George C Omega Study Group. No increase in HIV incidence observed in a cohort of men who have sex with other men in Montreal. AIDS (London, England) 2002;16:1183–1185. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200205240-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remis RS, Major C, Calzavara L, Myers T, Burchell A, Whittingham EP. The HIV Epidemic Among Men Who Have Sex with Other Men: The Situation in Ontario in the Year 2000. Report, Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Toronto; Toronto Ontario: Nov, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Scheer S, Douglas JM, Vittinghoff E, Bartholow BN, McKirnan D, Judson FN, et al. Feasibility and suitability of targeting young gay men for HIV vaccine efficacy trials. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes and Human Retrovirology. 1999;20:172–178. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199902010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarcz S, Kellogg T, McFarland W, Louie B, Kohn R, Busch M, et al. Differences in the temporal trends of HIV seroincidence and seroprevalence among sexually transmitted disease clinic patients, 1989–1998: Application of the serologic testing algorithm for recent HIV seroconversion. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;153:925–934. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.10.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seage GR, Holte SE, Metzger D, Koblin B, Gross M, Celum C, et al. Are US populations appropriate for trials of human immunodeficiency virus vaccine?: The HIVNET vaccine preparedness study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;153:619–627. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.7.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMASH study team. HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis C & Sexually Transmissible Infections in Australia. Annual Surveillance Report. Edited by the National Centre in HIV Social Research, The University of New South Wales; Sydney, Australia: 1999. [11/20/06]. http://web.med.unsw.edu.au/nchecr/Downloads/99ansurvrpt.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Martindale SL, Cornelisse PGA, Miller ML, Craib KJP, Schechter MT, et al. HIV infection and risk behaviours among young gay and bisexual men in Vancouver. Journal of the Canadian Medical Association. 2000;162:21–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suligoi B, Giuliani M, Galai N, Balducci M the STD Surveillance Working Group. HIV incidence among repeat HIV testers with sexually transmitted diseases in Italy. AIDS. 1999;13:845–850. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199905070-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabet SR, Krone MR, Paradise MA, Corey L, Stamm WE, Celum CL. Incidence of HIV and sexually transmitted diseases (STD) in a cohort of HIV-negative men who have sex with men (MSM) AIDS. 1998;12:2041–2048. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199815000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M, Hawkins K, Gonzalez A, Buchacz K, Aynalem G, Smith L, et al. User of the serologic testing algorithm for recent HIV seroconversion (STARHS) to identify recently acquired HIV infections in men with early syphilis in Los Angeles county. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2005;38(5):505–508. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000157390.55503.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The EXPLORE study team. Effects of a behavioral intervention to reduce acquisition of HIV infection among men who have sex with men: The EXPLORE randomized controlled study. Lancet. 2004;364:41–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16588-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong HHM, Kellogg T, Klausner JD, Katz MH, Dilley J, Knapper K, et al. Increases in sexually transmitted infections and sexual risk behavior without a concurrent increase in HIV incidence among men who have sex with men in San Francisco: A suggestion of HIV serosorting? Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2006;82:461–466. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.019950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. AIDS epidemic update: December 2007. UNAIDS; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- van den Noortgate W, Onghena P. Meta-analysis. In: Everitt BS, Howell DC, editors. Encyclopedia of statistics in behavioral science. London: Wiley; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- van der Snoek EM, Dewit JBF, Gotz HM, Mulder PGH, Neumann MHA, Van der Meijden WI. Incidence of sexually transmitted diseases and HIV infection in men who have sex with men related to knowledge, perceived susceptibility, and perceived severity of sexually transmitted diseases and HIV infection: Dutch MSM—cohort study. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2006;33:193–198. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000194593.58251.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock H, Dale M, Gwinn M, Satten GA, Kothe D, Mei J, et al. HIV seroincidence among patients at clinics for sexually transmitted diseases in nine cities in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2002;29:478–483. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200204150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock H, Sweeney S, Satten GA, Gwinn M for the STD Clinic HIV Seroincidence Study Group. HIV seroincidence and risk factors among patients repeatedly tested for HIV attending sexually transmitted disease clinics in the United States, 1991 to 1996. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes & Human Retrovirology. 1998;19:506–512. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199812150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkelstein W, Lyman D, Padian N, Grant R, Samuel M, Wiley J, et al. Sexual practices and risk of infection by the human immunodeficiency virus: The San Francisco Men’s Health Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1987;257(3):321–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]