Abstract

RNA interference (RNAi) is a powerful and widely used approach to investigate gene function, but a major limitation of the approach is the high incidence of non-specific phenotypes that arise due to off-target effects. We previously showed that RNAi-mediated knock-down of pico, which encodes the only member of the MRL family of adapter proteins in Drosophila, resulted in reduction in cell number and size leading to reduced tissue growth. In contrast, a recent study reported that pico knockdown leads to tissue dysmorphology, pointing to an indirect role for pico in the control of wing size. To understand the cause of this disparity we have utilised a synthetic RNAi-resistant transgene, which bears minimal sequence homology to the predicted dsRNA but encodes wild type Pico protein, to reanalyse the RNAi lines used in the two studies. We find that the RNAi lines from different sources exhibit different effects, with one set of lines uniquely resulting in a tissue dysmorphology phenotype when expressed in the developing wing. Importantly, the loss of tissue morphology fails to be complemented by co-overexpression of RNAi-resistant pico suggesting that this phenotype is the result of an off-target effect. This highlights the importance of careful validation of RNAi-induced phenotypes, and shows the potential of synthetic transgenes for their experimental validation.

Introduction

For more than 10 years, silencing of gene expression by RNA interference (RNAi) in Drosophilia melanogaster has provided a powerful approach to complement classic mutant studies for assessing loss of gene function in vitro and in vivo. The recent advent of transgenic libraries of inverted repeat constructs capable of expressing dsRNA for virtually any gene of interest in vivo [1], has led to the wide uptake of heritable RNAi technology. The use of the UAS-GAL4 expression system to target dsRNA expression to different cell types or stages of development has facilitated targeted genetic screens and allowed manipulation of gene function in different cellular contexts [2]. However, a major limitation of the approach is the high incidence of non-specific phenotypes that arise due to off-target effects [3], [4]. One way to mitigate the risk of misinterpreting RNAi-induced phenotypes is to use independent dsRNA constructs that target non-overlapping sequences of the same gene: if two or more independent lines produce the same effect one can have more confidence that the resulting phenotype is due to knockdown of the gene of interest. However, conflicting results for multiple dsRNAs targeting the same gene are difficult to interpret in the absence of other information. In silico predictions of the potential for off-targets (e.g. [5]) can be indicative in this regard, but a genetic complementation test is the best way to validate specificity of the RNAi-induced phenotype. Complementation experiments with wild type transgenes do not control for specificity because the ectopic mRNA may act by titrating RNAi knockdown of endogenous genes, whether they be on- or off-targets. In mammalian systems, where short siRNA molecules are used to induce RNAi, an effective solution to this problem is to test for rescue of the RNAi-induced phenotype using RNAi-resistant transgenes containing silent mutations in the region targeted by the siRNA [6], [7]. Here we have applied this principle to assess complementation of longer dsRNA molecules (typically around 0.5 kb in length) in Drosophila to distinguish between on and off-target effects.

The MRL (Mig-10, RIAM, Lamellipodin) family of proteins has been demonstrated to modulate the actin cytoskeleton in response to extracellular signals to effect changes in cell morphology, adhesion and migration [8], [9]. In addition to these roles, we reported that the Drosophila MRL orthologue encoded by pico, was required for tissue growth [10]. This was supported, in part, through our observations of the effect of RNAi knockdown of pico. For these experiments, we developed flies carrying an inverted repeat construct (picoRNAiIR4) capable of expressing hairpin dsRNA specific for pico under GAL4-UAS control. Expression of this construct with a wing-specific GAL4 driver (MS1096-GAL4) led to a reduction of pico expression and induced a significant reduction in adult wing area. Furthermore, we found that GFP-labelled picoRNAiIR4 clones in wing imaginal discs were small and had a reduced cell doubling time compared to wild-type control cells, without any change in cell cycle phase and cell density. One aspect of this growth effect of pico was re-examined in a recent paper [11]. In contradiction with our previous results [10], it was reported that RNAi targeting of pico lines leads to severe tissue dysmorphology rather than a strict growth phenotype in the adult wing [11]. Here we have analysed the source of the apparent disparity and find that RNAi lines from different sources exhibit different phenotypic effects. Unlike the construct we previously reported, the commercially available NIG-Fly RNAi lines 11940R-2 and 11940R-3 (referred to as picoRNAiR2 and picoRNAiR3 hereafter), which are different transgenic insertions of an independent inverted repeat construct, reduce the expression of a number of genes unrelated to pico, based on qRT-PCR analysis of predicted off-target genes, and produce a crumpled wing phenotype. Importantly, this phenotype is not rescued by overexpression of an RNAi-resistant pico construct, indicating that loss of normal wing morphology caused by overexpression of the NIG-Fly RNAi lines for pico is most likely caused by off-target effects.

Results

RNAi lines targeting pico display distinct adult wing phenotypes

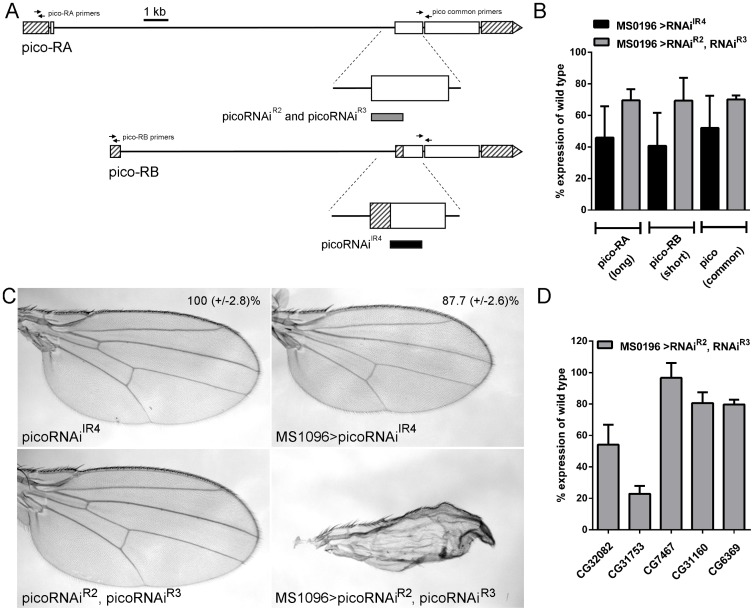

Previous studies on the function of pico loss-of-function have utilised two different sources of inverted repeat constructs to generate loss-of function phenotypes by RNAi-mediated knockdown: picoRNAi IR4 [10], and picoRNAi R2 /picoRNAi R3 (NIG-FLY). Mapping of the inverted repeat sequences to the pico transcription unit reveals that picoRNAi IR4 and picoRNAi R2,R3 map to an overlapping region of long and short pico transcripts, (picoRA and picoRB respectively, Fig. 1A).

Figure 1. Phenotypic effects of pico RNAi constructs.

A) Gene map showing long (pico-RA) and short (pico-RB) transcripts. Untranslated regions are shown with hatched boxes, coding exons are shown with open boxes. pico-RA and pico-RB share identical 3′ exons but differ at their 5′ ends. The position of oligonucleotide primers used to amply either pico-RA, pico-RB or both pico transcripts (for analysis of expression levels shown in panel B) are indicated with arrows. Magnified image of one of the coding exons shows the position of the inverted repeat constructs: picoRNAiR2/picoRNAiR3 (grey rectangle), picoRNAiIR4 (black rectangle). B) Ectopic expression of inverted repeat contructs using MS1096-GAL4 results in knockdown of pico mRNA levels in the wing imaginal disc. RNA was extracted from wing imaginal discs that had been dissected from larvae expressing UAS-picoRNAiIR4 (MS1096>picoRNAiIR4), or UAS-picoRNAiR2 and UAS-picoRNAiR3 (MS1096>picoRNAiR2, R3), and was analysed by qRT-PCR. Levels of picoRA, picoRB and all pico transcripts are shown as a percentage of the expression in wing discs from a control strain (w1118). C) Phenotypic effect of ectopic inverted repeat contructs on wing development. Flies carrying UAS-inverted repeat constructs alone (picoRNAiIR4 or picoRNAiR2 and picoRNAiR3) resemble wild type wings. Ectopic overexpression of picoRNAiIR4 (MS1096>picoRNAiIR4) resulted in a significant reduction of adult wings size (p<0.001) without any loss of morphology. In contrast ectopic picoRNAiR2, picoRNAiR3 (MS1096>picoRNAiR2, picoRNAiR3) resulted in severe loss of wing morphology as evidenced by crumpled wings. D) Ectopic co-overexpression of picoRNAiR2 and picoRNAiR3 using MS1096-GAL4 results in the knockdown of at least 4 predicted off-targets as determined by qRT-PCR. Levels of the predicted off targets (CG32082, CG31753, CG7467, CG31160, CG6369) in MS1096>picoRNAiR2,R3 wing discs are shown as a percentage of the expression in wing discs from a control strain (w1118).

To quantify the effect of these RNAi constructs on pico expression, we determined the levels of pico mRNA in whole wing imaginal discs from 3rd instar larvae either ectopically expressing picoRNAiIR4 or co-expressing picoRNAiR2 and picoRNAiR3 using MS1096-GAL4 by qRT-PCR (Fig. 1B). In early wondering third-instar wing discs, MS1096-GAL4 confers transgene expression evenly in both dorsal and ventral compartments of the wing pouch before becoming predominantly expressed in the dorsal half of the pouch. Although MS1096-GAL4 is not expressed throughout the entire wing disc, ectopic expression of one copy of picoRNAiIR4 using this driver (MS1096>picoRNAiIR4) resulted in a 52.1% reduction in picoRA and picoRB mRNA levels in whole wing disc extracts. Co-expression of one copy of both picoRNAiR2 and picoRNAiR3 (MS1096>picoRNAiR2,R3) also induced a strong depletion of both transcripts, although the knockdown was less pronounced than for picoRNAiIR4.

Next we assessed the phenotypic effect of pico RNAi using a read-out of tissue growth and morphology in the adult wing. picoRNAiIR4-mediated knockdown was accompanied by a significant reduction (p-value<0.001) of the adult wing size 87.7 +/−2.6%, without any noticeable wing dysmorphology (Fig. 1C), as previously reported [10]. In contrast, MS1096>picoRNAiR2,R3 induced a morphological defect in the adult wings, clearly visible from their crumpled appearance, despite a relatively lower efficacy of pico knockdown relative to picoRNAiIR4. Taken together, these data showed that although the two inverted repeat constructs knock down pico expression they exhibit very different phenotypes when ectopically expressed in the developing wing.

Ectopic picoR2, R3 knocks down the mRNA levels of several predicted off targets

To understand why picoRNAiR2,R3 affected tissue morphology, unlike picoRNAiIR4, we analysed the potential for off-target effects for each RNAi constructs using dsCheck (http://dscheck.rnai.jp/; [5]. Sequence analysis revealed that short inhibitory RNAs (siRNAs) generated from picoRNAiIR4 are highly specific to pico transcripts: 0 off-targets from 459 possible mers. In contrast, picoRNAiR2,R3 is predicted to generate siRNA oligomers with perfect homology to 19 other genes (Table 1). To experimentally assess the effect of picoRNAiR2,R3 on the expression of predicted off-target genes, we quantified the relative expression level of the first 5 predicted off-targets in wing discs by qRT-PCR. Notably, we observed a significant decrease in expression (20–81% of wild type, Fig. 1D) for 4 of the 5 off-targets in MS1096>picoRNAiR2,R3 discs compared to control discs (MS1096-GAL4 alone), in agreement with dsCheck predictions.

Table 1. List of potential off-targets for pico inverted repeat constructs.

| picoRNAiIR4 | picoRNAiR2 and picoRNAiR3 | ||||||||

| mis = 0 | mis = 1 | mis = 2 | FlyBase ID | CG number | mis = 0 | mis = 1 | mis = 2 | FlyBase ID | CG number |

| 459 | 0 | 0 | FBgn0261811 | CG11940-PB | 482 | 4 | 61 | FBgn0261811 | CG11940-PA |

| 459 | 0 | 0 | FBgn0261811 | CG11940-PA | 339 | 5 | 48 | FBgn0261811 | CG11940-PB |

| 0 | 2 | 7 | FBgn0022787 | CG4261-PA | 5 | 6 | 30 | FBgn0052082 | CG32082-PA |

| 0 | 2 | 3 | FBgn0031988 | CG8668-PA | 5 | 6 | 20 | FBgn0045852 | CG31753-PA |

| 0 | 2 | 2 | FBgn0027866 | CG9776-PA | 5 | 4 | 28 | FBgn0261885 | CG7467-PB |

| 0 | 2 | 2 | FBgn0021760 | CG32435-PA | 5 | 4 | 28 | FBgn0261885 | CG7467-PA |

| 0 | 2 | 2 | FBgn0033460 | CG1472-PA | 5 | 4 | 27 | FBgn0261885 | CG7467-PC |

| 0 | 2 | 2 | FBgn0021760 | CG32435-PB | 5 | 2 | 16 | FBgn0085405 | CG31160-PA |

| 0 | 2 | 2 | FBgn0021760 | CG32435-PC | 5 | 2 | 2 | FBgn0039260 | CG6369-PA |

| 0 | 2 | 2 | FBgn0027866 | CG9776-PB | 4 | 5 | 7 | FBgn0264895 | CG6682-PA |

| 0 | 1 | 7 | FBgn0052251 | CG32251-PA | 4 | 2 | 7 | FBgn0004889 | CG6235-PC |

| 0 | 1 | 5 | FBgn0031116 | CG1695-PB | 4 | 2 | 7 | FBgn0004889 | CG6235-PE |

| 0 | 1 | 5 | FBgn0031116 | CG1695-PA | 4 | 2 | 7 | FBgn0004889 | CG6235-PD |

| 0 | 1 | 5 | FBgn0263289 | CG5462-PA | 4 | 2 | 7 | FBgn0004889 | CG6235-PH |

| 0 | 1 | 5 | FBgn0263289 | CG5462-PD | 4 | 2 | 7 | FBgn0004889 | CG6235-PB |

| 0 | 1 | 5 | FBgn0263289 | CG5462-PB | 4 | 2 | 7 | FBgn0004889 | CG6235-PG |

| 0 | 1 | 5 | FBgn0263289 | CG5462-PC | 3 | 20 | 64 | FBgn0037252 | CG14650-PA |

| 0 | 1 | 3 | FBgn0033558 | CG12344-PA | 3 | 6 | 32 | FBgn0026718 | CG17608-PA |

| 0 | 1 | 3 | FBgn0039554 | CG5003-PA | 3 | 3 | 10 | FBgn0038412 | CG6898-PA |

| 0 | 1 | 3 | FBgn0261388 | CG15720-PA | 3 | 2 | 11 | FBgn0052333 | CG32333-PA |

| 0 | 1 | 3 | FBgn0053519 | CG30175-PA | 3 | 2 | 5 | FBgn0263144 | CG8276-PA |

| 0 | 1 | 3 | FBgn0031299 | CG4629-PC | 3 | 2 | 5 | FBgn0263144 | CG8276-PB |

| 0 | 1 | 3 | FBgn0028474 | CG4119-PA | 2 | 21 | 45 | FBgn0034072 | CG18250-PC |

| 0 | 1 | 3 | FBgn0024329 | CG7717-PA | 2 | 7 | 14 | FBgn0037503 | CG14598-PA |

| 0 | 1 | 3 | FBgn0024329 | CG7717-PB | 2 | 4 | 13 | FBgn0261938 | CG4644-PA |

| 0 | 1 | 3 | FBgn0031299 | CG4629-PB | 2 | 4 | 3 | FBgn0028380 | CG9670-PA |

| 0 | 1 | 3 | FBgn0031299 | CG4629-PA | 2 | 3 | 14 | FBgn0004435 | CG17759-PA |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | FBgn0051301 | CG31301-PA | 2 | 3 | 14 | FBgn0004435 | CG17759-PG |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | FBgn0028647 | CG11902-PA | 2 | 3 | 8 | FBgn0263396 | CG16901 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | FBgn0037391 | CG2017-PB | 1 | 22 | 117 | FBgn0016694 | CG17888-PD |

Off-targets were determined using dscheck (http://dscheck.rnai.jp/), which generates all possible 19 mers that can be theoretically generated from a longer dsRNA sequence and determines their homology to Drosophila genes identified by their Flybase ID and Celera Genomics (CG) number. The number of 19 mers matching each gene found by the sequence comparison are tabulated, where Mis = 0, Mis = 1, Mis = 2 correspond to the number of 19 mers with 0, 1 and 2 mismatches for each gene, respectively.

Wing dysmorphology phenotypes of picoRNAiR2,R3 are not rescued by over-expression of an RNAi-resistant pico transgene

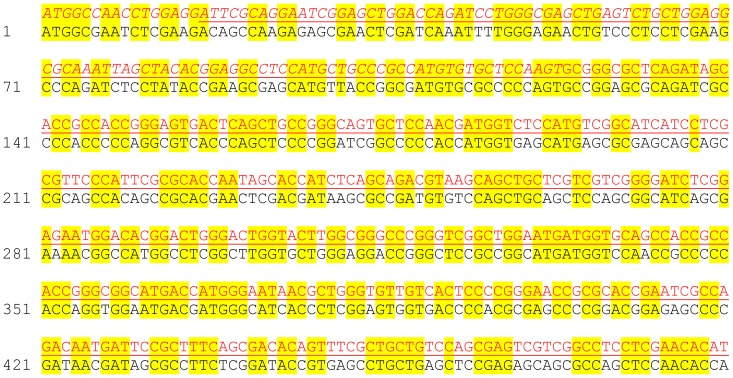

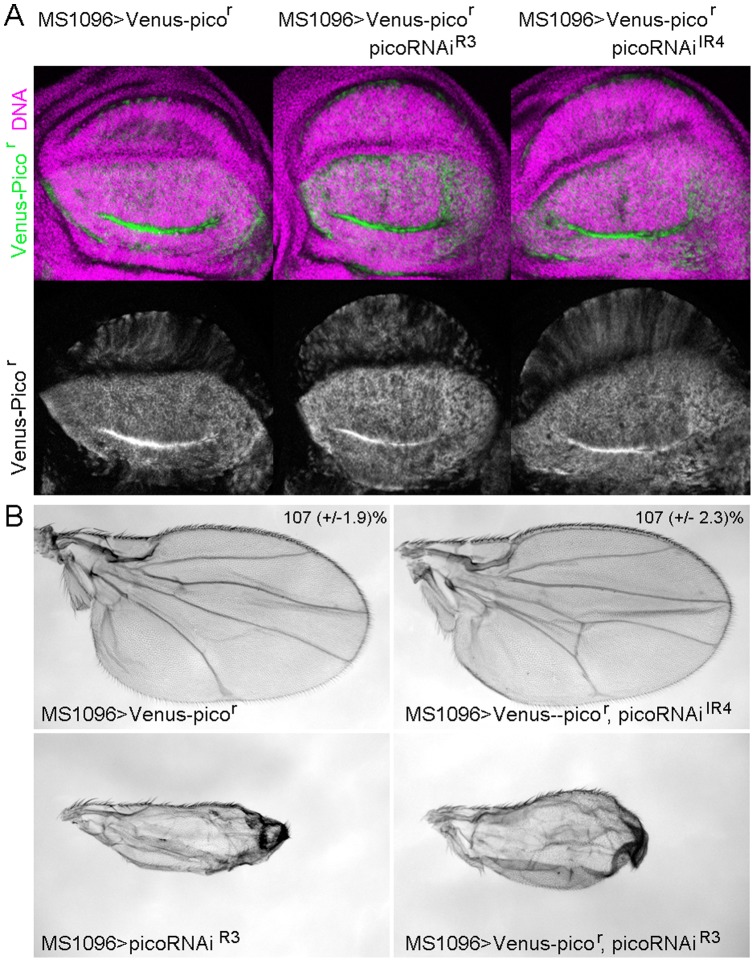

To test if the wing dysmorphology phenotype resulting from overexpression of picoRNAiR2/R3 was due to off-target effects of the inverted repeat construct, we developed an RNAi-resistant form of pico (picor) that could be used in genetic complementation tests. This was done by incorporating numerous silent polymorphic mutations into a synthetic gene construct encoding the short isoform of Pico (picoRB). Changes in the codon usage that we introduced consequently meant that, in the regions targeted by the RNAi, homology with the inverted repeat sequences was limited to no more than 8 contiguous base pairs (Fig. 2). To assess the resistance of ectopic picor to dsRNA for pico, we generated transgenic flies capable of expressing Venus-tagged picor under UAS-GAL4 control and analysed the levels of the Venus-tagged ectopic protein in the presence or absence of the inverted repeat constructs. Venus, a variant of enhanced Yellow Fluorescent Protein, was readily detectible when the tagged protein was ectopically expressed in the wing pouch under the control of MS1096-GAL4. Notably, ectopic expression of Venus-Picor was not modified by co-expression of picoRNAiIR4 or picoRNAiR3, demonstrating that ectopic Picor is resistant to RNAi-mediated knockdown (Fig. 3A).

Figure 2. Sequence comparison of wild type and synthetic pico genes.

Shown is a sequence alignment of the first 493 bp of the synthetic pico transgene (in black) and the equivalent region of the endogenous pico gene (in red). Identical bases in the two sequences are highlighted in yellow. The regions corresponding to picoRNAiIR4 is underlined. The region overlapping with that of picoRNAiR2/R3 is in italics.

Figure 3. A synthetic RNAi-resistant pico transgene rescues the phenotypic effect of ectopic picoRNAiIR4 but not picoRNAiR3.

A) Expression of a synthetic, Venus-tagged, pico transgene is not affected by co-expression of picoRNAi constructs. Confocal images of wing imaginal discs from flies expressing UAS-Venus-picor alone (MS1096>Venus-picor), or together with UAS-picoRNAi constructs (MS1096>Venus-picor, picoRNAiR3 or MS1096>Venus-picor, picoRNAi IR4) are shown. DNA staining with TO-PRO-3 (magenta in the merged image) reveals that each image is of a similar section through the disc, whilst the Venus signal (green in the merged image) reveals that the levels of Venus-picor are largely unaffected by co-expression with the pico inverted repeat constructs. B) Ectopic expression of Venus-picor rescues the growth defect resulting from picoRNAiIR4, but not the wing dysmorphology phenotype displayed by picoRNAiR3. Ectopic Venus-picor under the control of MS1096-GAL4 (MS1096>Venus-picor) results in an increase in wing size. Ectopic picoRNAiR3 (MS1096> picoRNAiR3) results in a crumpled wing (similar to the effect of co-expressing picoRNAiR2 and picoRNAiIR3, as in Figure 1C), and this is not suppressed by Venus-picor (MS1096>Venus-picor, picoRNAiR3). In contrast, coexpression of Venus-picor and picoRNAiIR4 (MS1096>Venus-picor, picoRNAiIR3) resembles the effect of Venus-picor alone.

Next we tested whether the phenotypic effect of MS1096>picoRNAiIR4 or picoRNAiR3 could be rescued by overexpression of Picor (Fig. 3B). Previously we reported that overexpression of wild type pico short with MS1096-GAL4 resulted in modest tissue overgrowth. Similarly, ectopic-tagged Venus-picor resulted in a 107% increase in adult wing size, indicating that the Venus tag does not interfere with its ability to promote growth. When we coexpressed picor together with picoRNAiIR4 the adult wings resembled those of ectopic picor alone, indicating that the reduced wing size resulting from MS1096>picoRNAiIR4 was rescued by expression of picor. Notably, the effect of picor and picoRNAiIR4 was not simply additive, indicating that the level of Picor is likely to be much more than two fold that of endogenous levels. In contrast, ectopic picor failed to rescue the crumpled wing resulting from picoRNAiR3 overexpression (Fig. 3B). Taken together, these data confirm that specific RNAi-mediated knockdown of pico results in a tissue growth phenotype, and indicate that the tissue dysmorphology phenotype associated with picoRNAiR3 is attributable to an off-target effect.

Discussion

Comprehensive validation of an RNAi-induced phenotype requires demonstration that: i) the expression level of the intended target is reduced by the RNAi; ii) the expression of any potential off-targets is not affected; and, iii) the RNAi-induced phenotype can be reversed by expression of the wild type protein; genetic complementation should be with an RNAi-resistant form of the gene, and not rely on overexpression of wild type mRNA that could sequester siRNA molecules from both off- and on-targets alike. Applying these principles to the validation of pico RNAi lines, we set about to determine whether the discrepancy in reported phenotypes for pico knockdown could be explained by potential off-target effects. Firstly, we assessed the levels of pico mRNA in wing discs expressing pico inverted repeat constructs. qRT-PCR revealed that both of the RNAi constructs tested (picoRNAiIR4 and picoRNAiR2/R3) were effective in knocking down pico mRNA levels. The efficacy of picoRNAiIR4 is consistent with our previous observations that levels of ectopically expressed epitope-tagged Pico were reduced in the presence of picoRNAiIR4 [10]. Next, we analysed potential off-targets in silico and in extracts. Unlike picoRNAiIR4, picoRNAiR2/R3 was predicted to affect the expression of numerous off-target genes. qRT-PCR analysis confirmed that the expression level of 4 out of 5 of the predicted off-targets tested were indeed reduced by picoRNAiR2/R3. Notably, although the number of siRNA oligomers that matched the off-target genes was low (e.g. 5 predicted off-target 19 mers as compared to 482 on-target 19 mers, Table 1), they nevertheless drastically affected the gene expression of these off-target genes. This highlights the importance of testing the specificity of RNAi lines experimentally. To do this, we tested the ability of a synthetic transgene to rescue the RNAi-induced phenotypes. Phenotypic analysis of picoRNAiIR4 and picoRNAiR2/R3 revealed two distinct effects: picoRNAiR2,R3 promoted loss of normal wing morphology, whereas picoIR4 induced a reduction in wing size. Importantly, we found that the effect of picoRNAiR3 was not rescued by overexpression of the RNAi-resistant form of pico (picor) and is most likely a consequence of the reduced expression of one or more of its predicted off-targets.

Our findings reinforce the value of experimentally testing the specificity of RNAi-induced phenotypes to ensure they are correctly attributed to knockdown of the gene of interest. In general, the strategy that we have employed using synthetic transgenes is widely applicable to the validation of any RNAi construct. Efficient gene synthesis of long stetches of DNA has become increasingly affordable in the last few years and rivals the cost of conventional cloning approaches. Almost any coding region of a gene can be rendered resistant because, on average, every third base can be substituted due to the degeneracy of the genetic code. However, regions containing multiple codons for either Methionine or Tryptophan, which do not allow sequence substitutions if the amino acid sequence is to be maintained, are refractory to this approach. Untranslated regions targeted by an RNAi construct can simply be omitted from any rescue construct [12], [13]. By extension, this approach could be utilised to test the role of critical domains or single amino-acids by engineering the synthetic transgene to harbour additional genetic changes that affect the coding sequence of the ectopic protein. The use of the GAL4-UAS system means that knockdown and complementation experiments can be performed in a tissue-specific or stage specific manner. Furthermore, a range of UAS-expression vectors are publicly available with fluorescent and epitope tags that can be used to readily monitor the ability of the transgene to elude RNAi-mediated knockdown. However, the use of GAL4-UAS system for genetic complementation tests is not without its limitations. Firstly, the use of a GAL4 driver (and to a lesser extent changes to codon usage) means that levels of the synthetic transgene are not endogenous. Secondly, whereas an on-target RNAi should only have an effect in cells where there is endogenous expression of the target gene, the protein produced from a synthetic rescue construct may be ectopically expressed in cells where there is no endogenous expression. This may be mitigated by the use of an enhancer trap GAL4 line driving GAL4 under the control of the target gene promoter, but enhancer trap lines that faithfully replicate the endogenous expression pattern only exist for a minority of genes.

Another strategy that has recently been developed to test genetic complementation in Drosophila melanogaster is based on the use of cross-species transgenic constructs [14], [15]. This method uses the genomic DNA of different Drosophila species such as Drosophila pseudoobscura that are divergent enough from the host sequence to make the genomic constructs RNAi-resistant. However, this approach is also not without its limitations. Cross-species constructs may also show differences in their pattern of expression relative to the endogenous gene in Drosophila melanogaster, not least because of position effects associated with the insertion site of the transgene. In addition, the genomes of the donor species often carry non-synonymous substitutions affecting the amino-acid sequences of the gene products. Very minor changes in amino acid sequences can abolish functional rescue in interspecies crosses for example by drastically affecting the ability of proteins from divergent species to interact correctly with one another [16]. In addition, because the constructs are not tagged it is hard to readily assess whether protein levels are refractory to the effects of the RNAi.

In summary, we report here the results of experiments to test the specificity of two RNAi constructs for the pico gene that display different phenotypic effects. Notably one of the RNAi constructs affects the expression of various off-target genes despite the prediction that only a limited number of siRNA oligomers generated from the full-length dsRNA target these loci. We find the use of synthetic gene fragments resistant to knockdown by RNAi to be an effective approach to distinguish between specific and non-specific effects.

Materials and Methods

Fly husbandry and genetics

Flies were reared at 25°C under standard conditions. picoIR2-3 RNAi lines came from NIG-Fly (National institute of Genetics: 11940R); picoIR4 was described in a previous paper [10]. Phenotypic analysis of adult wings and effect of pico RNAi lines on pico mRNA expression was determined using the wing imaginal disc driver MS1096-GAL4. Genotypes were as follows:

1B, D MS1096-GAL4

1B, D MS1096-GAL4; UAS-picoRNAiR2/+; UAS-picoRNAiR3/+

1B MS1096-GAL4; UAS-picoRNAiIR4/+

1C UAS-picoRNAiIR4/+

1C MS1096-GAL4/Y; UAS-picoRNAiIR4/+

1C UAS-picoRNAiR2/+; UAS-picoRNAiR3/+

1C MS1096-GAL4/Y; UAS-picoRNAiR2/+; UAS-picoRNAiR3/+

2A,B MS1096-GAL4/Y; UAS-Venus-picor/+

2A,B MS1096-GAL4/Y; UAS-Venus-picor/+; UAS-picoRNAiR3/+

2A,B MS1096-GAL4/Y; UAS-Venus-picor/+; UAS-picoRNAiIR4/+

2A,B MS1096-GAL4/Y; UAS-picoRNAiR3/+.

Wing Area Analysis

Male adult flies wings were dissected and fixed in 75% ethanol, and mounted on glass slides in Canadian Balsam mounting medium (Gary's Magic Mountant) and examined by light microscopy. The wing area, exclusive of the alula and the costal cell, was measured using NIH ImageJ (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/), n = 35 per genotype. To avoid observer bias in the measurements of wing areas, experimenters were blinded to the genotype of flies. A t-test was applied to test for a significant effect of MS1096-GAL4, UAS-picoRNAi on wing size by comparison with UAS-picoRNAi alone.

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR

3rd instar larval imaginal tissues were dissected in cold Phosphate Buffered Saline buffer, put in RNAlater (Invitrogen), quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until isolation of RNA. 3 pools of imaginal discs were made for each condition tested (MS1096-GAL4; MS1096>picoIR4; MS1096>picoIR2-3) corresponding to at least 24 imaginal discs/pool. RNA extractions were performed using the Ambion RNAqueous-Micro Kit (Invitrogen). RNA concentrations were measured at 260 nm and RNA integrity was evaluated on a 2% agarose gel. 1 µg of total RNA samples were subjected to reverse-transcription using High capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (Applied biosystems/Invitrogen). Primer design was performed using Primer3 online software, http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/ [17]. The specificity of primers was assessed by sequencing of PCR products (GATC Biotech), and alignment of the resulting sequences by performing BLASTN against the Drosophila melanogaster transcriptome. cDNA were amplified in real time using the qPCR Master mix plus for power SYBR Green I assay (Invitrogen) and analysed with the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Each run included triplicates of control cDNA corresponding to a pool of imaginal discs from MS1096-GAL4 and MS1096>picoRNAi lines, no-template controls and samples. The threshold cycle (Ct) was determined for each sample and control cDNA. A calibration curve was calculated using the Ct values of the control cDNA samples and the relative amounts of unknown samples were deduced from this curve. The level of expression for genes tested with different RNAi lines was compared to wild-type expression (in an MS1096-GAL4 strain) and expressed as a percentage of the latter.

RNAi-resistant construct design

Codon usage in the transcript picoRB was modified with the introduction of silent mutations to render it resistant to RNAi-mediated knockdown, whilst minimising the use of rare codons that are recognised by low abundance tRNA species. 187/493 bp were changed in the region targeted by picoRNAiIR4 and picoRNAiR2,3 as shown in Fig. 2. picor was synthesised and subcloned into pDONR221 Gateway cloning vector (Invitrogen). Gateway LR reactions were performed to shuttle picoR from the pDONR221 entry vector into pTVW (UASt promoter with an N-terminal Venus tag) vector (Drosophila Genomics Resource Center) for expression in flies with an N-terminal Venus Tag. Transgenic flies were generated using P element mediated germline transformation of a w1118 strain.

Acknowledgments

We thank BioPioneer Inc (USA) for gene synthesis, Genetic Services Inc (USA) and Chris Lofthouse for generation of the transgenic flies and the Liverpool Centre for Cell Imaging for assistance with confocal image acquisition. We thank members of the Bennett lab for critical comments on the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by CRUK grant C20691/A11834. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Dietzl G, Chen D, Schnorrer F, Su K-C, Barinova Y, et al. (2007) A genome-wide transgenic RNAi library for conditional gene inactivation in Drosophila . Nature 448: 151–U151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. del Valle Rodriguez A, Didiano D, Desplan C (2012) Power tools for gene expression and clonal analysis in Drosophila . Nat Methods 9: 47–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kulkarni MM, Booker M, Silver SJ, Friedman A, Hong P, et al. (2006) Evidence of off-target effects associated with long dsRNAs in Drosophila melanogaster cell-based assays. Nature Methods 3: 833–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ma Y, Creanga A, Lum L, Beachy PA (2006) Prevalence of off-target effects in Drosophila RNA interference screens. Nature 443: 359–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Naito Y, Yamada T, Matsumiya T, Ui-Tei K, Saigo K, et al. (2005) dsCheck: highly sensitive off-target search software for double-stranded RNA-mediated RNA interference. Nucleic Acids Research 33: W589–W591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Editors (2003) Whither RNAi? Nat Cell Biol 5: 489–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lassus P, Rodriguez J, Lazebnik Y (2002) Confirming specificity of RNAi in mammalian cells. Science's STKE: signal transduction knowledge environment 2002: pl13–pl13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Colo GP, Lafuente EM, Teixido J (2012) The MRL proteins: Adapting cell adhesion, migration and growth. European Journal of Cell Biology 91: 861–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Legg JA, Machesky LM (2004) MRL proteins: Leading Ena/VASP to Ras GTPases. Nature Cell Biology 6: 1015–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lyulcheva E, Taylor E, Michael M, Vehlow A, Tan S, et al. (2008) Drosophila Pico and Its Mammalian Ortholog Lamellipodin Activate Serum Response Factor and Promote Cell Proliferation. Developmental Cell 15: 680–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thompson BJ (2010) Mal/SRF Is Dispensable for Cell Proliferation in Drosophila . Plos One 5: e10077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stielow B, Sapetschnig A, Kruger I, Kunert N, Brehm A, et al. (2008) Identification of SUMO-dependent chromatin-associated transcriptional repression components by a genome-wide RNAi screen. Mol Cell 29: 742–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yokokura T, Dresnek D, Huseinovic N, Lisi S, Abdelwahid E, et al. (2004) Dissection of DIAP1 functional domains via a mutant replacement strategy. J Biol Chem 279: 52603–52612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kondo S, Booker M, Perrimon N (2009) Cross-Species RNAi Rescue Platform in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 183: 1165–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Langer CC, Ejsmont RK, Schonbauer C, Schnorrer F, Tomancak P (2010) In vivo RNAi rescue in Drosophila melanogaster with genomic transgenes from Drosophila pseudoobscura . PLoS One 5: e8928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barrientos A, Muller S, Dey R, Wienberg J, Moraes CT (2000) Cytochrome c oxidase assembly in primates is sensitive to small evolutionary variations in amino acid sequence. Mol Biol Evol 17: 1508–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rozen S, Skaletsky H (2000) Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, NJ) 132: 365–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]