Abstract

Desulfocapsa sulfexigens SB164P1 (DSM 10523) belongs to the deltaproteobacterial family Desulfobulbaceae and is one of two validly described members of its genus. This strain was selected for genome sequencing, because it is the first marine bacterium reported to thrive on the disproportionation of elemental sulfur, a process with a unresolved enzymatic pathway in which elemental sulfur serves both as electron donor and electron acceptor. Furthermore, in contrast to its phylogenetically closest relatives, which are dissimilatory sulfate-reducers, D. sulfexigens is unable to grow by sulfate reduction and appears metabolically specialized in growing by disproportionating elemental sulfur, sulfite or thiosulfate with CO2 as the sole carbon source. The genome of D. sulfexigens contains the set of genes that is required for nitrogen fixation. In an acetylene assay it could be shown that the strain reduces acetylene to ethylene, which is indicative for N-fixation. The circular chromosome of D. sulfexigens SB164P1 comprises 3,986,761 bp and harbors 3,551 protein-coding genes of which 78% have a predicted function based on auto-annotation. The chromosome furthermore encodes 46 tRNA genes and 3 rRNA operons.

Keywords: Sulfur-cycle, thiosulfate, sulfite, sulfur disproportionation, marine, sediment

Introduction

The disproportionation of inorganic sulfur is a microbially catalyzed chemolithotrophic process, in which elemental sulfur, thiosulfate and sulfite serve as both electron donor and acceptor, and are converted to hydrogen sulfide and sulfate. Thus, the overall process is comparable to the fermentation of organic compounds and is consequently often described as “inorganic fermentation”. Disproportionation of thiosulfate and sulfite represent exergonic processes with ΔG0’ of -21.9 and -58.9 kJ mol-1 of substrate, respectively [1]. In contrast, the disproportionation of elemental sulfur is endergonic under standard conditions (ΔG0’ = 10.2 kJ mol-1 S0). However, the energy output depends on the concentration of hydrogen sulfide, and under environmental conditions, where concentrations of free hydrogen sulfide are low due to precipitation with iron and/or rapid oxidation, the process becomes exergonic - e.g. ΔG0’ = -30 kJ mol-1 S0 at a hydrogen sulfide concentration of 10-7 M and a sulfate concentration of 2.8 x 10-2 M [2,3]. Isotope tracer studies have shown that inorganic sulfur disproportionation is of environmental significance in marine sediments [4,5]. Furthermore it seems to be a very ancient mode of microbial energy metabolism that has presumably left significant isotopic signatures in the geological sulfur rock record [6,7].

The ability to disproportionate inorganic sulfur compounds has recently been documented for a number of anaerobic sulfate-reducing Deltaproteobacteria, in particular for species of the genera Desulfocapsa, Desulfobulbus, Desulfovibrio and Desulfofustis (see [8] for a review). Additionally, Milucka et al. [9] found first evidence for this process to occur among Desulfobacteraceae in association with methane-oxidizing Archaea. The authors proposed that the associated bacteria disproportionate sulfur that stems from sulfate reduction by the methanotrophic archaea and that is released in the form of disulfide.

The reaction pathways underlying thiosulfate and sulfite disproportionation have been partly resolved owing to studies of enzymatic activities in cell extracts [10,11]. However, the mechanism by which elemental sulfur is first accessed by the cell and later processed is enigmatic, and the genetic basis of the deltaproteobacterial disproportionation pathways are currently unclear.

The two validly described members of the deltaproteobacterial genus Desulfocapsa, D. sulfexigens SB164P12 [2] and D. thiozymogenes Bra2 [12] are both able to grow by disproportionating elemental sulfur, thiosulfate or sulfite under anaerobic conditions using CO2 as their sole carbon source. Unlike D. thiozymogenes and most members of their sister genera within the family Desulfobulbaceae, D. sulfexigens is unable to grow by sulfate reduction. This specialized energy metabolism qualifies D. sulfexigens as a relevant candidate model organism for studying the physiologically interesting and biogeochemically relevant process of disproportionation of inorganic sulfur compounds. Here we present a summary of the taxonomic classification and key phenotypic features of D. sulfexigens SB164P1 together with the description of its complete and annotated genome sequence.

Classification and features

Desulfocapsa sulfexigens (sul.f.ex′i.gens. L. n.sulfurum, sulfur; L. v.exigo, to demand; M. L. part. adj. sulfexigens, demanding sulfur for growth) SB164P1T, DSM 10523T [13] was isolated from a tidal flat in the bay of Arcachon at the southwest coast of France. It is a strictly meso- and neutrophilic anaerobic bacterium with rod-shaped cells that are motile by a polar flagellum (Table1). In addition to growing by disproportionating sulfite, thiosulfate and elemental sulfur, D. sulfexigens SB164P1T also grows by reducing elemental sulfur with H2 as the electron donor, a process, which occurs concomitantly with elemental sulfur disproportionation in the presence of H2 (K. Finster unpublished results). When growing by elemental sulfur disproportionation in the presence of excess ferric iron as sulfide scavenger, pyrite and sulfate are the main end products of its dissimilatory metabolism. D. sulfexigens SB164P1T grows autotrophically on bicarbonate, as 13C-bicarbonate is incorporated into cell material and biomass production is not stimulated by the presence of acetate in the growth medium [10]. The strain is routinely grown with ammonia as a nitrogen source but can also fix N2 (Unpublished data).

Table 1. Classification and general features of D. sulfexigens SB164P1 according to the MIGS recommendations [14].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [15] | |

| Phylum Proteobacteria | TAS [16] | ||

| Class Deltaproteobacteria | TAS [17,18] | ||

| Order Desulfobacterales | TAS [18,19] | ||

| Family Desulfobulbaceae | TAS [20,21] | ||

| Genus Desulfocapsa | TAS [12,22] | ||

| Species Desulfocapsa sulfexigens | TAS [2,23] | ||

| Gram stain | negative | TAS [2] | |

| Cell shape | rod-shaped | TAS [2] | |

| Motility | motile | TAS [2] | |

| Sporulation | non-sporulating | TAS [2] | |

| Temperature range | mesophilic; optimum 300 C | TAS [2] | |

| pH range | 6.0 to 8.2 | TAS [2] | |

| MIGS-6.3 | Salinity range | 0.17 – 0.33 M Na+ | TAS [2] |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirements | anaerobic | TAS [2] |

| Carbon source | HCO3- | TAS [2] | |

| Energy source | elemental sulfur, sulfite, thiosulfate | TAS [2] | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | marine surface sediment | TAS [2] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | free-living | TAS [2] |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | none | NAS |

| Biosafety level | 1 | NAS | |

| Isolation | tidal flat sediment | NAS | |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Arcachon Bay, France | TAS [2] |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection | 1996 | NAS |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | 44.66 | NAS |

| MIGS-4.2 | Longitude | -1.17 | NAS |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | surface sediment | TAS [2] |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | Sea level | TAS [2] |

TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement.

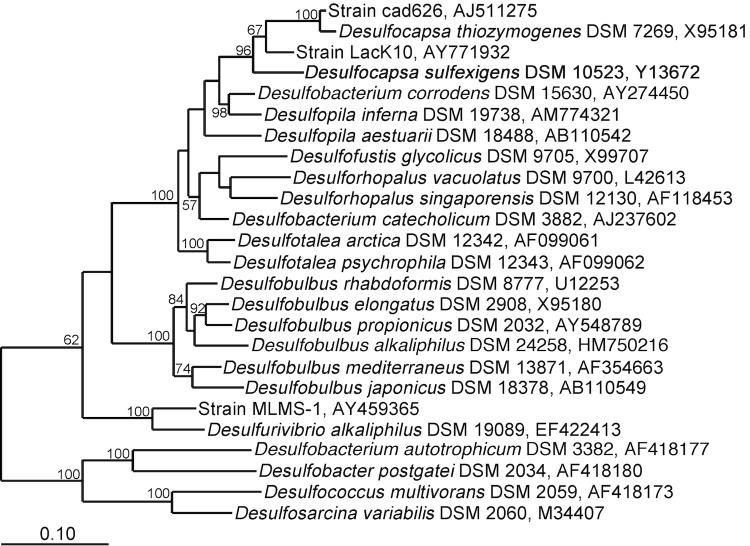

D. sulfexigens SB164P1 and D. thiozymogenes Bra2T [12] constitute the only validly published members of the genus Desulfocapsa, which on the basis of 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis forms a monophyletic lineage within the deltaproteobacterial family Desulfobulbaceae (Figure 1). So far, full genome sequences have been published for two other members of this family, Desulfobulbus propionicus DSM 2032 [25] and Desulfotalea psychrophila LSv54 [26], while genome sequences of two additional members are deposited in GenBank: Desulfurivibrio alkaliphilus AHT 2 (GenBank: AAQF01000000) and strain MLMS-1 (GenBank: CP001940). D. sulfexigens SB164P1T shares less than 89% 16S rRNA gene sequence identity with any of these species (Figure 1). The lack of genome sequences of close phylogenetic relatives also adds value to the here published complete genome sequence of D. sulfexigens.

Figure 1.

Phylogeny of Desulfocapsa sulfexigens based on the 16S rRNA gene. The tree was inferred from maximum likelihood analysis (RAxML [24]) with sampling of 1330 aligned sequence positions. Tree searches were performed with the general time reversible evolutionary model with a gamma-distributed rate variation across sites. Scale bar, 10% estimated sequence divergence. Values at nodes are neighbor-joining-based bootstrap percentages, calculated with Jukes Cantor distance correction and 1,000 replications.

Genome sequencing information

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

The strain was grown with thiosulfate as energy source in standard bicarbonate medium at pH 7 and at 30° C [2]. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, stored at minus 80° C and shipped on dry ice to the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics (Berlin, Germany). There, the DNA was isolated with the Genomic DNA kit (Qiagen, Hildesheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions, evaluated using standard procedures and sequenced.

Genome sequencing, assembly and annotation

The genome of D. sulfexigens SB164P1 was sequenced using the 454 GS FLX Titanium [Table 2] pyrosequencing system (360,793 reads; Roche) combined with fosmid end-sequencing using the pCC1FOS vector (5,836 reads; Epicentre). Together, the pyrosequencing and the fosmid end-sequencing reads achieved a coverage of 32.4×. The reads were assembled in a hybrid-assembly using Newbler version 2.5.3 (Roche). Gaps in the assembly were closed using 259 reads generated by Sanger sequencing. The genome was auto-annotated using the IMG-ER pipeline [27].

Table 2. Genome sequencing project information.

| MIGS ID | Characteristic | Details |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | 2kb (pUC19) and 40kb (pcc1FOS) Sanger and 454 standard libraries |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platform | ABI-3730, 454 GS FLX Titanium |

| MIGS-31.2 | Sequencing coverage | 1.1× Sanger 40kb insert, 31.3× pyrosequencing |

| MIGS-31 | Finishing Quality | Finished |

| MIGS-30 | Assembler | gsAssembler (Newbler) version 2.5.3 |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | IMG-ER pipeline [27](CRISPR: CRT [28] and PILERCR [29]; tRNAs: tRNAScan-SE-1.23 [30]; rRNA: RNAmmer [31]; other genes: Prodigal [32]) |

| GenBank ID | CP003985, CP003986 | |

| GenBank date of release | 14.01.2013 | |

| GOLD ID | Gi18068 | |

| NCBI project ID | 91121 | |

| IMG Taxon ID | 2512875001 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source material identifier | DSM 10523T |

| Project relevance | Sulfur cycle |

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers:

Sequences of chromosome and plasmid of Desulfocapsa sulfexigens have been deposited at GenBank with the accession numbers CP003985 and CP003986, respectively.

Genome properties

In total, the genome of D. sulfexigens SB164P1 consists of one chromosome with a size of 3,986,761 bp (G+C content: 45% [Table 3]) and one plasmid with a size of 36,751 bp (G+C content: 44%). A total of 3,551 protein coding genes (thereof 31 on the plasmid), 46 tRNA-encoding genes, and 3 rRNA operons were predicted. Of all protein-encoding genes, 2,794 (78.7%) were auto-annotated with a functional prediction. The distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 4.

Table 3. Genome statistics.

| Attribute | Value | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 4,023,512 | |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 3,615,930 | 89.87% |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 1,825,760 | 45.38% |

| Extrachromosomal elements (plasmids) | 1 | |

| Size of extrachromosomal element (bp) | 36,751 | |

| Total genes | 3,551 | 100% |

| RNA genes | 60 | 1.69% |

| rRNA operons | 3 | |

| Protein-coding genes | 2,794 | 78.68% |

| Genes in paralog clusters | 1,286 | 36.22% |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 2,772 | 78.06% |

| Genes assigned Pfam domains | 2,902 | 81.72% |

| Genes with signal peptides | 764 | 21.52% |

| CRISPR count | 1 |

Table 4. Number of genes associated with the general COG functional categories.

| Code | Genes on chromosome |

Genes on plasmid |

%age | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | 175 | 2 | 5.7 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | ||||

| K | 120 | 1 | 3.9 | Transcription |

| L | 153 | 8 | 5 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 5 | 0 | 0.2 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 33 | 1 | 1.1 | Cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning |

| Y | ||||

| V | 51 | 0 | 1.7 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 310 | 0 | 10.2 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 250 | 0 | 8.2 | Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis |

| N | 83 | 0 | 2.7 | Cell motility |

| Z | ||||

| W | ||||

| U | 93 | 0 | 3 | Intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport |

| O | 116 | 0 | 3.8 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 256 | 1 | 8.4 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 105 | 0 | 3.4 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 216 | 1 | 7.1 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 71 | 1 | 2.3 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 157 | 2 | 5.1 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 79 | 0 | 2.6 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 161 | 0 | 5.3 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 50 | 0 | 1.6 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| S | 230 | 1 | 7.5 | Function unknown |

| - | 859 | 0 | - | Not in COGs |

Insights from the genome sequence

Sulfur and energy metabolism

D. sulfexigens SB164P1 thrives on the disproportionation of thiosulfate, sulfite and elemental sulfur, but is unable to reduce sulfate, although it is related to sulfate reducers, of which several are able to grow by both sulfate reduction and disproportionation, e.g. D. thiozymogenes, D. propionicus DSM 2032 and Desulfofustis glycolicus DSM 9705 [2,12,33]. This is intriguing as the genome of D. sulfexigens SB164P1 contains the complete set of genes known to be involved in dissimilatory sulfate reduction [34] including: SulP-family sulfate permease (UWK_00097), ATP sulfurylase (UWK_02284), Mn- dependent inorganic pyrophosphatase (UWK_01588, UWK_03148), the AprA and B subunits of APS reductase (UWK_02023, UWK_02024) and the DsrA, B, C and D subunits of the dissimilatory sulfite reductase (UWK_01633, UWK_01634, UWK_01635) and DsrC (UWK_00448). Also genes encoding sulfite-reductase-associated electron transport proteins DsrPJKM (UWK_00239 – UWK_00242) are present in the genome of D. sulfexigens SB164P1. Thus, it is still unknown why D. sulfexigens SB164P1 is unable to respire sulfate.

In addition, 6 genes encoding polysulfide reductases were found (UWK_00238, UKW_02207, UWK_02291, UWK_03020, UKW_03030, UWK_03039, UWK_03284). Four of 7 polysulfide reductases form an operon with a 4Fe-4S ferredoxin iron–sulfur binding domain containing a hydrogenase and a cytochrome C family protein. They may be involved in the reduction of elemental sulfur to H2S [35] and are thus likely involved in hydrogenotrophic sulfur reduction - an alternative to elemental sulfur disproportionation for generating energy for D. sulfexigens SB164P12 [8]. The genome contains several molybdopterin oxidoreductases (UWK_01206, UWK_02209 & UWK_02642, UWK_02781) that are likely involved in sulfur metabolism either as subunits of thiosulfate or tetrathionate reductases. Thiosulfate reductase catalyzes the initial step in the disproportionation of thiosulfate, i.e. its reductive cleavage into sulfite and sulfide [8]. An operon containing genes encoding a sulfur reductase/hydrogenase beta subunit (UWK_01338), an oxidoreductase FAD/NAD(P)- binding subunit (UWK_01339), a NADH ubiquinone oxidoreductase (UWK_01340) and a sulfur reductase/hydrogenase alpha subunit (UWK_01341) was identified. Similar to the function of polysulfide reductases, this operon may encode proteins that are involved in coupling hydrogen oxidation to sulfur reduction. Finally, three genes encoding for heterodisulfide reductase subunits HdrA, HdrB and HdrC (UKW_02025, UKW_02026, UKW_02027) were found. They may be involved in the oxidation of elemental sulfur to sulfite [36], and thus replace the function of the reverse sulfite reductase in the disproportionation pathway [8], which was not found in the genome. Sulfite as an intermediate was confirmed by the observation of free sulfite in medium of cultures that grew by thiosulfate as well as by elemental sulfur disproportionation [11]. However, only genes encoding dissimilatory sulfite reductases were hitherto identified in the genome. Finally the genome encodes nine rhodanese-related sulfurtransferases that may be involved in the metabolism of thiosulfate and elemental sulfur during disproportionation (UWK_00046; UWK _ 00165; UWK _ 00611; UWK _00945; UWK _01143; UWK _01446; UWK _ 01496; UWK _03368; UWK _03369) although their specific roles in disproportionation mechanisms need to be investigated.

Inhibition experiments with the proton gradient uncoupler CCCP, the electron transport chain inhibitor HQNO [11] as well as with molybdate [2], a competitive inhibitor of sulfate reducers that interferes with the formation of activated sulfate (APS) [37], showed that D. sulfexigens uses both substrate level phosphorylation and the generation of proton motive force for ATP generation during disproportionation [34]. In accordance, its genome contained genes encoding a F-type ATPase. Subunits A, B and C of the F0 subcomplex are encoded by genes (UKW_ 00974; UWK _01665), (UWK_00972; UWK _001702; UWK _01703) and (UWK_00973; UWK _01666). The subunits α, β, γ, δ and ε of the F1 subcomplex are encoded by genes (UWK_00971; UWK _01705), (UWK_00978; UWK _01708), (UWK_00970; UWK _01706), (UWK_01704) and (UWK_00977; UWK _01708), respectively. The genome also encodes a proton-translocating NADH hydrogenase (UWK_03559 to UWK_03571).

Carbon assimilation

D. sulfexigens SB164P1 grows autotrophically by fixing CO2. Accordingly, its genome encodes a complete acetyl-CoA pathway for fixing CO2 including the key enzymes carbon monoxide dehydrogenase catalytic subunit (UWK_03164) and acetyl-CoA decarboxylase/synthase (UWK_03163) [38]; and carbon monoxide dehydrogenase activity was observed in enzyme assay-based studies of D. sulfexigens SB164P1 [10]. Indirect support for an active carbon assimilation via the reversed acetyl-CoA pathway was provided by the high carbon fractionation value of 37 per mill determined by carbon isotope studies of the cell biomass [10]. Thus, D. sulfexigens SB164P1 appears to be able to thrive on CO2 as its only carbon source using a reverse acetyl-CoA pathway. This is the first report of the identity of a carbon fixation pathway of a member of the family Desulfobulbaceae. Notably, this pathway is shared with the sulfate reducer Desulfobacterium autotrophicum HRM1 of the Desulfobacteraceae in which it has been studied in detail [39].

Organic carbon in the form of acetate neither enhanced the growth yield nor the growth rate of D. sulfexigens SB164P1, indicating that CO2 fixation is not a growth-limiting process. Despite the fact that D. sulfexigens SB164P1 is unable to use organic substrates as e-donors and energy source, its genome encodes a complete TCA cycle [40]: (citrate synthase I and II (UWK_01937; UWK _00579), aconitate hydratase (UWK_01509), isocitrate dehydrogenase (UWK_01609), 2-oxo-glutarate dehydrogenase α, β, γ subunit (UWK_02894 to UWK_02896), succinyl CoA synthetase α and β subunit (UWK_01582; UWK _01584), fumarate reductase cytochrome b subunit, flavoprotein subunit and Fe-S protein subunit (UWK_03265 to UWK_03267) and malate dehydrogenase (UWK_03173). It also encodes a complete glycolysis pathway (Berg et al. 2002): Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (UWK_01632), fructose 6-phosphate kinase (UWK_01908), fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (UWK_03194), fructose bisphosphate aldolase (UWK_02512), triosephosphate isomerase (UWK_00786; UWK _01623), glyceraldehyde-3 phosphate dehydrogenase (UWK_01687), phosphoenol pyruvate synthase (UWK_00627; UWK__02176; UWK _02650), 3-phosphoglycerate kinase (UWK_00787), 2,3 phosphoglycerate mutase (UWK_03186) and pyruvate kinase (UWK_00304; UWK _00318; UWK _00709) are encoded in its genome. These pathways run probably in reverse in D. sulfexigens and are involved in the synthesis of cell material.

Nitrogen metabolism

D. sulfexigens SB164P1 grows with free nitrogen gas as sole nitrogen source. Accordingly, all genes necessary for nitrogen fixation were identified in the genome [41]. They are closely linked in the genome. The derived proteins are: NifH (UWK_0033), NifHD1 and NifHD2 that function as regulator proteins (UWK_00334; UWK _00335), NifD and NifK, which constitute the α and β chain of the molybdenum-iron nitrogenase (UWK_00336; UWK _00337), a nitrogenase associated protein (UWK_00340) and NifE, NifN and NifB (UWK_00347; UWK _00348; UWK _00349). Cultures of D. sulfexigens reduce acetylene to ethylene in a standard nitrogen fixation assay. Thus, despite the low energy output of the sulfur disproportionation reaction D. sulfexigens conserves sufficient energy to grow both autotrophically and diazotrophically.

Furthermore the D. sulfexigens SB164P1 genome indicates a potential for dissimilatory nitrate and nitrite metabolism including an operon that contains three units of an ABC type nitrate/sulfonate/bicarbonate transport system consisting of a periplasmic (UKW_00829), a permease (UKW_00830) and an ATPase (UKW_00831) component. In addition, the genome contains two nitrate/nitrite transporters driven by electrochemical potential (UKW_02352, UKW_03309), three nitrate/TMAO reductases (UKW_02209, UKW_02550, UKW_03309), one nitrate reductase (gamma subunit) (UKW_00242), one NADPH-nitrite reductase (UKW_03259) and two hydroxylamine reductases (UKW_00765, UKW_03258). The NADPH dependent nitrite reductase is of an assimilatory type that reduces nitrite to ammonium hydroxide. Ammonium can then be assimilated by the cell. A similar set of transport systems and reductases has been reported being responsible for nitrate assimilation in Rhodobacter capsulatus E1F1 [42].

Oxidative stress

The genome of D. sulfexigens encodes several genes involved in defense against oxidative stress such as superoxide dismutase (UWK_02392) and catalase (UWK_00321). In addition, the genome encodes the two subunits of a cytochrome bd-type quinol oxidase (UWK_01593; UWK _01594). This enzyme reduces oxygen with electrons from the quinone pool and may thereby protect cells from oxygen [43]. Moreover, the genome encodes 5 glutathione synthases (UWK_00572; UWK_00580; UWK _01802; UWK _03585; UWK _03624). Glutathione may serve as an antioxidant and as an oxygen scavenger [44].

As the substrates for sulfur disproportionation are mainly generated as intermediates of sulfide oxidation in the oxic-anoxic interfaces D. sulfexigens seems well equipped to maneuver in an environment, where it occasionally may encounter oxygen or its partly reduced intermediates. In such a habitat, the capacity to detoxify reactive oxygen species including hydroxyl- and superoxide radicals as well as hydrogen peroxide seems of key importance for survival.

Chemotaxis and motility

The genome of D. sulfexigens SB 164P1 contains 10 methyl-accepting chemotaxis transmembrane proteins (UWK_00167; UWK_00267; UWK_00616; UWK_00640; UWK_00995; UWK_01396; UWK_01397; UWK_01493; UWK_01787; UWK_01890) that interact with chemotaxis signal transduction proteins CheW (UWK_00950; UWK_03012; UWK_03013). CheW is also involved in flagellar motion. In addition, we found a number of different response regulators including 32 copies of one type that was automatically annotated as a response regulator containing a CheY-like receiver AAA-type ATPase, and a DNA binding domain. This regulator receives signals from a sensor partner in a bacterial 2-component system (UKW_00056; UKW_00306; UKW_00595; UKW_00622; UKW_00625, UKW_00834; UKW_00976; UKW_01208; UKW_01271; UKW_01512; UKW_01944; UKW_01945; UKW_01945; UKW_01952; UKW_02106; UKW_02134; UKW_02287; UKW_02315; UKW_02346; UKW_02374; UKW_02508; UKW_02614; UKW_02645; UKW_02648; UKW_02788; UKW_02863; UKW_02986; UKW_03016; UKW_03064; UKW_03068; UKW_03331; UKW_03429; UKW_03516). We also found a number of other genes that are encoding parts of the chemotaxis complex such as CheB that is composed of a sensor histidine kinase and a response regulator (UKW_02813; UKW_03014), CheC that functions as a methylation inhibitor and restores the pre-stimulus level of the cell (UKW_03066; UKW_03067) and CheR, a methylase which methylates the chemotaxis receptor (UKW_03015)(see [45] for a detailed overview).

The genome contains all the genes that are required for flagellum formation [46] (FlgA, UWK_03088; FlgB, UWK_03070; FlgC, UWK_03071; FlgD, UWK_03080; FlgE, UWK_03081; FlgF, UWK_03097; FlgG, UWK_03098; FlgH, UWK_03101; FlgI, UWK_03101; FlgJ, UWK_03102; FlgK, UWK_03106; FlgL, UWK_03100; FlgM, UWK_03104; FlgP, UWK_03101; FliC, UWK_03115; FliD, UWK_03113; FliE, UWK_03072; FliG, UWK_3074; FliH, UWK_03075; FliI, UWK_03076; FliJ, UWK_03077; FlgL, UWK_03084; FliM, UWK_03085; FliN, UWK_03086; FliO, UWK_03087; FliP, UWK_03088; FliQ, UWK_03089; FliR, UWK_03090; FliS, UWK_03112; FlhA, UWK_03092; FlhB, UWK_03091; FlhF, UWK_03093). The flagellar motor consists of proteins MotA and MotB encoded by UWK_03082 and UWK_03083, respectively. A motor of this type is driven by a proton gradient. This may explain the need for ATPases, which may be used to generate a proton motive force rather than being involved in ATP synthesis.

Conclusion

The complete genome of the marine bacterium Desulfocapsa sulfexigens SB164P1 provides the starting point for a detailed analysis of the pathways involved in the disproportionation of inorganic sulfur compounds including elemental sulfur, thiosulfate and sulfite. Apart from being studied in its own right sulfur disproportionation is a key process in the sulfur cycle on a global scale with significant imprints in the geological record. In addition, the increasing number of 16S rRNA gene sequences with close similarity to members of the genus Desulfocapsa indicates the prevalence of the process in numerous, geophysically diverse habitats.

Acknowledgements

Kai Finster acknowledges support by the Danish agency for science technology and innovation (ref.no. 272-08-0497). KF is very grateful to the colleagues at the Max Planck Institute of Marine Microbiology for their hospitality and support. LS and KUK were funded by the Danish National Research Foundation.

Abbreviations:

- APS

Adenosine 5'-phosphosulfate CCCP, Carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone , HQNO: 2-n-heptyl-4-hydroxyquinoline N-oxide

References

- 1.Bak F, Cypionka H. A novel type of energy metabolism involving fermentation of inorganic sulphur compounds. Nature 1987; 326:891-892 10.1038/326891a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finster K, Liesack W, Thamdrup B. Elemental sulfur and thiosulfate disproportionation by Desulfocapsa sulfoexigens sp. nov., a new anaerobic bacterium isolated from marine surface sediment. Appl Environ Microbiol 1998; 64:119-125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thamdrup B, Finster K, Hansen JW, Bak F. Bacterial disproportionation of elemental sulfur coupled to chemical reduction of iron or manganese. Appl Environ Microbiol 1993; 59:101-108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fike DA, Gammon CL, Ziebis W, Orphan VJ. Micron-scale mapping of sulfur cycling across the oxycline of a cyanobacterial mat: a paired nanoSIMS and CARD-FISH approach. ISME J 2008; 2:749-759 10.1038/ismej.2008.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jørgensen BB. A thiosulfate shunt in the sulfur cycle of marine sediments. Science 1990; 249:152-154 10.1126/science.249.4965.152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canfield DE, Thamdrup B, Fleischer S. Isotope Fractionation and Sulfur Metabolism by Pure and Enrichment Cultures of Elemental Sulfur-Disproportionating Bacteria. Limnol Oceanogr 1998; 43:253-264 10.4319/lo.1998.43.2.0253 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Philippot P, Van Zuilen M, Lepot K, Thomazo C, Farquhar J, Van Kranendonk MJ. Early archaean microorganisms preferred elemental sulfur, not sulfate. Science 2007; 317:1534-1537 10.1126/science.1145861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finster K. Microbiological disproportionation of inorganic sulfur compounds. J Sulfur Chem 2008; 29:281-292 10.1080/17415990802105770 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Milucka J, Ferdelman TG, Polerecky L, Franzke D, Wegener G, Schmid M, Lieberwirth I, Wagner M, Widdel F, Kuypers MMM. Zero-valent sulphur is a key intermediate in marine methane oxidation. Nature 2012; 491:541-546 10.1038/nature11656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frederiksen TM, Finster K. The transformation of inorganic sulfur compounds and the assimilation of organic and inorganic carbon by the sulfur disproportionating bacterium Desulfocapsa sulfoexigens. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2004; 85:141-149 10.1023/B:ANTO.0000020153.82679.f4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frederiksen TM, Finster K. Sulfite-oxido-reductase is involved in the oxidation of sulfite in Desulfocapsa sulfoexigens during disproportionation of thiosulfate and elemental sulfur. Biodegradation 2003; 14:189-198 10.1023/A:1024255830925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janssen PH, Schuhmann A, Bak F, Liesack W. Disproportionation of inorganic sulfur compounds by the sulfate-reducing bacterium Desulfocapsa thiozymogenes gen. nov., sp. nov. Arch Microbiol 1996; 166:184-192 10.1007/s002030050374 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Validation of publication of new names and new combinations previously effectively published outside the IJSEM. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2000; 50:1699-1700 10.1099/00207713-50-5-1699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Phylum XIV. Proteobacteria phyl. nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 2, Part B, Springer, New York, 2005, p. 1 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuever J, Rainey FA, Widdel F. Class IV. Deltaproteobacteria class. nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT, editors. Bergey's Manual of Sys-tematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 2, Part B. New York: Springer; 2005. p 922-1144. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Validation List No. 107. List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2006; 56:1-6 10.1099/ijs.0.64188-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuever J, Rainey FA, Widdel F. Order III. Desulfobacterales ord. nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT, editors. Bergey's Manual of Sys-tematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 2, Part B. New York: Springer; 2005. p 959-1002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuever J, Rainey F, Widdel F. Desulfobulbus Widdel 1981, 382 VP (Effective publication: Widdel 1980, 374). In: Brenner D, Krieg N, Garrity G, Staley J, Boone D, Vos P, Goodfellow M, Rainey F, Schleifer K-H, editors. Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology: Springer US; 2005. p 988-992. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuever J, Rainey FA, Widdel F. Family II. Desulfobulbaceae fam. nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 2, Part C, Springer, New York, 2005, p. 988. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Validation List no. 61. Validation of the publication of new names and new combinations previously effectively published outside the IJSB. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:601-602 10.1099/00207713-47-2-601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Validation of publication of new names and new combinations previously effectively published outside the IJSEM. Validation List no. 76. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2000; 50:1699-1700 10.1099/00207713-50-5-1699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stamatakis A, Ludwig T, Meier H. RAxML-III: a fast program for maximum likelihood-based inference of large phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 2005; 21:456-463 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pagani I, Lapidus A, Nolan M, Lucas S, Hammon N, Deshpande S, Cheng JF, Chertkov O, Davenport K, Tapia R, et al. Complete genome sequence of Desulfobulbus propionicus type strain (1pr3 T). Stand Genomic Sci 2011; 4:100-110 10.4056/sigs.1613929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rabus R, Ruepp A, Frickey T, Rattei T, Fartmann B, Stark M, Bauer M, Zibat A, Lombardot T, Becker I, et al. The genome of Desulfotalea psychrophila, a sulfate-reducing bacterium from permanently cold Arctic sediments. Environ Microbiol 2004; 6:887-902 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00665.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Markowitz VM, Mavromatis K, Ivanova NN, Chen IMA, Chu K, Kyrpides NC. IMG ER: a system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:2271-2278 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bland C, Ramsey T, Sabree F, Lowe M, Brown K, Kyrpides N, Hugenholtz P. CRISPR Recognition Tool (CRT): a tool for automatic detection of clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats. BMC Bioinformatics 2007; 8:209 10.1186/1471-2105-8-209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anonymous. 2009 PILER Genomic repeat analysis software. <http://www.drive5.com/pilercr>.

- 30.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: A Program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Research 1997;25(5):0955-964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Lagesen K, Hallin P, Rødland EA, Stærfeldt HH, Rognes T, Ussery DW. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res 2007; 35:3100-3108 10.1093/nar/gkm160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hyatt D, Chen GL, LoCascio P, Land M, Larimer F, Hauser L. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics 2010; 11:119 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Widdel F, Pfennig N. Studies on dissimilatory sulfate-reducing bacteria that decompose fatty acids II. Incomplete oxidation of propionate by Desulfobulbus propionicus gen. nov., sp. nov. Arch Microbiol 1982; 131:360-365 10.1007/BF00411187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bradley AS, Leavitt WD, Johnston DT. Revisiting the dissimilatory sulfate reduction pathway. Geobiology 2011; 9:446-457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jormakka M, Yokoyama K, Yano T, Tamakoshi M, Akimoto S, Shimamura T, Curmi P, Iwata S. Molecular mechanism of energy conservation in polysulfide respiration. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2008; 15:730-737 10.1038/nsmb.1434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quatrini R, Appia-Ayme C, Denis Y, Jedlicki E, Holmes D, Bonnefoy V. Extending the models for iron and sulfur oxidation in the extreme acidophile Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. BMC Genomics 2009; 10:394 10.1186/1471-2164-10-394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oremland R, Capone D. Use of specific inhibitors in biogeochemistry and microbial ecology. Adv Microb Ecol 1988; 10:285-383 10.1007/978-1-4684-5409-3_8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ragsdale SW, Wood HG. Enzymology of the Acetyl-CoA pathway of CO2 fixation. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 1991; 26:261-300 10.3109/10409239109114070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Länge S, Scholtz R, Fuchs G. Oxidative and reductive acetyl CoA/carbon monoxide dehydrogenase pathway in Desulfobacterium autotrophicum - 1. Characterization and metabolic function of the cellular tetrahydropterin. Arch Microbiol 1988; 151:77-83 10.1007/BF00444673 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thauer RK. Citric-acid cycle, 50 years on. Eur J Biochem 1988; 176:497-508 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb14307.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gussin G, Ronson C, Ausubel F. Regulation of nitrogen fixation genes. Annu Rev Genet 1986; 20:567-591 10.1146/annurev.ge.20.120186.003031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pino C, Olmo-Mira F, Cabello P, Martnez-Luque M, Castillo F, Roldn M, Moreno-Vivin C. The assimilatory nitrate reduction system of the phototrophic bacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus E1F1. Biochem Soc Trans 2006; 34:127-129 10.1042/BST0340127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cypionka H. Oxygen Respiration by Desulfovibrio Species. Annu Rev Microbiol 2000; 54:827-848 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mannervik B, Carlberg I, Larson K. Glutathione - General review of mechanisms of action. In: Dolphin D, Poulsen R, Avicmovic, editors. Coenzymes and Cofactors IIIA. New York: Wiley; 1989. p 475-516. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Porter SL, Wadhams GH, Armitage JP. Signal processing in complex chemotaxis pathways. Nat Rev Microbiol 2011; 9:153-165 10.1038/nrmicro2505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pallen MJ, Matzke NJ. From the origin of species to the origin of bacterial flagella. Nat Rev Microbiol 2006; 4:784-790 10.1038/nrmicro1493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]