Abstract

The immotile testicular mammalian spermatozoon gets transformed into a motile spermatozoon during 'epididymal maturation'. During this process, the spermatozoa transit from the caput to the cauda epididymis and undergo a number of distinct morphological, biophysical and biochemical changes, including changes in protein composition and protein modifications, which may be relevant to the acquisition of motility potential. The present proteome-based study of the hamster epididymal spermatozoa of caput and cauda led to the identification of 113 proteins spots using Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization tandem mass spectrometry (MALDI-MS/MS) analysis. Comparison of these 113 protein spots indicated that 30 protein spots (corresponding to 20 proteins) were significantly changed in intensity. Five proteins were increased and eleven were decreased in intensity in the cauda epididymal spermatozoa. In addition, two proteins, glucose-regulated protein precursor (GRP78) and tumor rejection antigen (GP96), were unique to the caput epididymal spermatozoa, while one protein, fibrinogen-like protein 1, was unique to cauda epididymal spermatozoa. A few of the five proteins, which increased in intensity, were related to sperm metabolism and ATP production during epididymal maturation. The changes in intensity of a few proteins such as ERp57, GRP78, GP96, Hsp60, Hsp70, and dihydrolipoamide S-acetyltransferase were validated by immunoblotting. The present study provides a global picture of the changes in protein composition occurring during hamster sperm epididymal maturation, besides being the first ever report on the proteome of hamster spermatozoa.

Keywords: epididymis, hamster, motility, proteome, spermatozoa

Introduction

The testicular mammalian spermatozoon is an immature and immotile cell and, following maturation in the epididymis, gets transformed into a mature and motile cell, capable of capacitating and fertilizing the oocyte successfully 1, 2, 3. During epididymal maturation, the spermatozoon transits from the caput to the cauda epididymis through the corpus epididymis and undergoes a number of distinct morphological, biochemical and biophysical changes 4. Some of these changes, such as stabilization of sperm tail components 5, changes in the biophysical properties of the membranes 6, changes in protein composition 7, 8, 9 and protein modifications 8, 10, 11, may be directly relevant to the acquisition of motility potential by spermatozoa during epididymal maturation 12. Changes in protein composition during epididymal maturation of spermatozoa may be attributed to the ability of spermatozoa to absorb/release proteins from/into the epididymal fluid 2, 13 or to the protein modifications introduced by virtue of post-translational changes such as glycosylation and proteolytic cleavage 4. A few earlier studies have indicated that epididymal secretory proteins bind to the sperm surface during epididymal maturation in a variety of mammalian species 14, 15. Some of these proteins of the epididymal fluid that bind to spermatozoa include sperm-associated antigen 16 and cysteine-rich secretory protein 1 17 in rat; P26h, P25b and P34H in hamster 18, bull 19 and humans 20; and epididymal proteins (HE1, HE2, HE4, HE5 and HE12) 4 and epididymal protease inhibitor 21 in humans.

With the advent of proteomics, it has been possible to establish the total proteome of spermatozoa from different species such as mouse 22, rat 23, bull 24, 25, boar 26 and man 27, 28, thus leading to the identification of many more proteins in the spermatozoa. Proteome studies also provide information on sperm function 29, 30, 31, 32, which have also led to the identification of immunogenic sperm antigens 33. Besides these studies, as yet there have been only two studies on the protein changes occurring during epididymal maturation and both studies have been carried out in the rat 8, 11.

In the present study, attempt has been made to establish the proteome of hamster spermatozoa from the caput and cauda epididymal regions using Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization tandem mass spectrometry (MALDI-MS/MS) so as to delineate the variations in the proteome during epididymal transit and to get an insight into the molecular basis of epididymal maturation in hamster spermatozoa. Such studies based on the differential proteome of spermatozoa acquired from different regions of the epididymis help to identify and predict the role of epididymal proteins involved in sperm motility. Candidate proteins involved in the process may further be used as tools to understand the molecular basis of motility acquisition potential. This is the first report on the proteome of hamster spermatozoa and the changes in protein composition during epididymal maturation.

Materials and methods

Preparation of spermatozoal proteins

The caput and cauda epididymal spermatozoa of 6-month-old male Golden hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) were collected as described in references 10, 34. The caput and cauda regions of the epididymis were dissected, surrounding fat removed, punctured, and the spermatozoa were then allowed to ooze out into Tris-buffered saline (TBS, pH 7.5 containing 30 mmol L−1 Tris, and 150 mmol L−1 NaCl). The resulting suspension was checked under a phase-contrast microscope and found to be free from epithelial cells. The spermatozoa were washed thrice in TBS to remove any traces of epididymal fluid and the final spermatozoa pellet was rinsed in 30 mmol L−1 Tris, pH 7.5. Proteins were then extracted from these sperm pellets at 4 °C for 1 h using the lysis buffer (7 mol L−1 urea, 2 mol L−1 thiourea, 30 mmol L−1 n-octyl β-𝒟-glucopyranoside, 18 mmol L−1 DTT, 16 mmol L−1 CHAPS, 0.5% pharmalytes pH 3–10 and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The extract was then centrifuged at 131 000 × g for 1 h, the supernatant containing the solubilized sperm proteins was recovered and the concentration of the protein was estimated by using the amido black method 35. The institutional animal ethics committee approved the use of animals.

Two-dimensional 2D gel electrophoresis and PD Quest image analysis

An equal amount of sperm protein (150 μg) was diluted in a rehydration buffer (composition same as that of lysis buffer), adsorbed onto a commercially available Immobilized pH gradient (IPG) strip (7 cm, pH 5–8; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) by passive rehydration for 12 h and then subjected to isoelectric focusing at 50 mA per IPG strip at 4000 V for 20 000 VH using a Protean IEF cell (Bio-Rad) as described in reference 34. After focusing, the strips were equilibrated and the second-dimension electrophoresis was performed on 10% SDS polyacrylamide gels (8 × 8 × 0.15 cm3; Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK). The gels were stained using colloidal Coomassie G-250 stain 36. A total of 30 gels (15 sets) were run using proteins from a single caput and the cauda epididymal region of an individual animal.

The stained gels were then scanned using the Fluor-S™ Multi-Imager (Bio-Rad) and the resulting images were analyzed by PD Quest (version 8.0.1; Bio-Rad) to identify the protein spots and to assess the qualitative and quantitative changes. The non-parametric Mann-Whitney test was performed with 95% significance level (P < 0.05) to determine which proteins varied in intensity between the caput and the cauda epididymal spermatozoa.

Protein identification by MALDI-MS/MS

In-gel digestion and identification of proteins was performed according to a standard procedure 37. In brief, the protein spots were excised, destained, vacuum-dried, trypsin digested, spotted on a MALDI plate and identified by MALDI MS/MS using the Applied Biosystems 4800 Proteomics Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) 34. Peptide mass calibration was performed using an external mass standard (Calmix 5; Applied Biosystems). The spectra were analyzed using in-house GPS Explorer™ software version 3.5 (Applied Biosystems, Foster, CA, USA), with fixed carbamidomethylcysteine and variable methionine oxidation. The database used was Rodentia NCBInr 2008 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

The criteria used for MS and MS/MS peak filtering were a mass tolerance of 50 ppm and the number of accepted missed cleavage sites set to one. The experimental mass values were mono-isotopic. No restrictions on protein molecular weight and pI values were applied. The MS/MS fragment tolerance for MS peak filtering was 0.25, while that for MS/MS peak filtering was 0.1. The criteria used to accept identifications included the MOWSE score, the extent of sequence coverage and the number of matched peptides as detailed in Supplementary Table 1.

Immunolocalization of ERp57 GRP78 and GP96, in hamster, mouse, rat and ejaculated human spermatozoa

The caput and cauda epididymal spermatozoa of hamster were washed in TBS, fixed in 2% formaldehyde in PBS, coated onto clean glass coverslips, air-dried (37 °C), permeabilized in ice-cold (−20 °C) methanol for 20 s and then subjected to immunofluoresence using anti-ERp57 (1:200) antibodies as the primary antibody and goat anti-rabbit-Cy3 (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA, USA) as the secondary antibody. After immunostaining, the coverslips were mounted on clean glass slides using VECTASHIELD® (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) as the mounting medium and viewed under an Axioplan2 epifluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc., Jena, Germany). Immunolocalization was carried out for ERp57 protein in the caput and cauda spermatozoa of mouse, rat and ejaculated spermatozoa of humans. Using the same protocol, immunolocalization was also carried out in the caput and cauda epididymal spermatozoa of hamster.

Immunoblot analysis

Hamster sperm proteins that were separated by SDS-PAGE were electrotransferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane at 100 V for 1 h using the wet transfer system (Hoefer Scientific Instruments, San Francisco, CA, USA) 34. The membranes were checked for equal loading by 0.1% Ponceau S and were then blocked with 5% (w/v) non-fat milk in TBST (10 mmol L−1Tris, 150 mmol L−1 NaCl containing Tween 20, 0.1% [v/v]) for 1 h at room temperature, washed and incubated with the primary antibody prepared in TBST plus 1% BSA for 1 h. The primary antibodies used were ERp57 (polyclonal, 1:2 000), GRP78 (polyclonal, 1:1 000), Hsp60 (monoclonal, 1:500), Hsp70 (monoclonal, 1:2 000) GP96 (monoclonal, 1:1 000) and dihydrolipoamide S-acetyltransferase (1:2 000). All the antibodies were obtained commercially (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). The secondary antibody used was conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) and was used at a concentration of 1:10 000. The blots were developed using the ECL kit (Amersham). Exposed films were scanned using a Fluor-S™ Multi-Imager (Bio-Rad), and the bands of interest were quantified using GeneTools version 3.06.04 from SynGene (Cambridge, England).

Results

Hamster epididymal sperm proteins

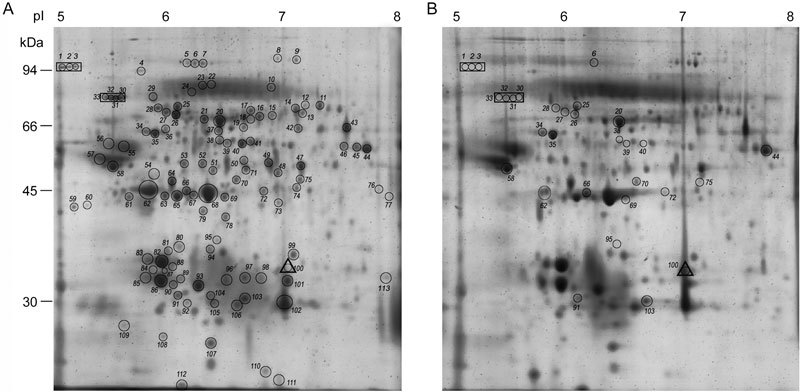

Sperm proteins (150 μg) from the caput and cauda epididymal spermatozoa of individual hamsters (n = 15) were resolved using 2D gels (Figure 1). All the 2D gels from the two groups, namely caput and cauda epididymal spermatozoa, gave similar results characteristic of the group. For comparative analysis, a total of ten 2D gels representing five each of caput and cauda epididymal spermatozoa were analyzed by using PD Quest software. The five sets of gels showed a high coefficient of correlation (r = 0.91–0.96 for cauda epididymal spermatozoa and r = 0.92–0.93 for caput). The number of protein spots detected in the caput and cauda epididymal spermatozoa of hamster were 179 and 165, respectively. Attempts were made to analyze all the spots by MALDI MS/MS mass spectrometry with peptide mass fingerprinting and MS/MS. Out of 179 spots, 48 spots were very faint and were not processed. The remaining 131 protein spots consistent with the proteomes of either caput or cauda, or both were processed. Out of the 131 protein spots, 113 protein spots were unambiguously identified (Supplementary Table 1) and 18 yielded no identity, as the MOWSE score was low. The 113 protein spots represented 61 proteins, and of these only 14 proteins have been reported earlier in the hamster protein database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov; Supplementary Table 1). The peptide mass fingerprint sequences of these proteins have been submitted to UniProtKB protein database (http://www.uniprot.org; Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1.

Representative 2D maps of the proteins of hamster caput (A) and cauda (B) epididymal spermatozoa resolved in the pI range of pH 5–8. The mol. wt. of the standard proteins is indicated. The protein spots encircled and numbered in (A) and (B) are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Encircled proteins within a rectangle in A and B represent spots unique to caput and the encircled protein within a triangle represents a protein unique to cauda epididymal spermatozoa. The encircled proteins in (B) are those proteins that exhibit increase or decrease in intensity in cauda epididymal spermatozoa compared with caput epididymal spermatozoa.

A significant number of the identified proteins in the hamster sperm proteome existed in several pI isoforms, the details of which are provided in Supplementary Table 1. The proteins of the hamster sperm proteome could be functionally characterized as proteins involved in metabolism and ATP production (36.2%), proteins with structural function (25.8%), chaperones and stress proteins (21.3%), antioxidants and detoxifying enzymes (6.1%), proteins involved in signaling and transport (5.3%) and those involved in other functions (5.3%) (Supplementary Table 1).

Protein composition of hamster caput and cauda epididymal spermatozoa

For differential studies using PD Quest analysis, 131 protein spots were matched from both caput and cauda epididymal spermatozoa (five data sets). These 131 protein spots (Figure 1), when subjected to non-parametric Mann–Whitney's test (P < 0.05), indicated that a total of 52 protein spots showed significant change in intensity (Figure 1, Table 1). Of these, only 30 protein spots gave positive MS/MS identities. Of the 30 protein spots (Table 1), 5 protein spots were increased (P < 0.05), while 14 protein spots were decreased (P < 0.05) in intensity in the cauda epididymal spermatozoa. Seven protein spots were unique to the caput epididymal spermatozoa, while one protein spot was unique to the cauda epididymal spermatozoa (Table 1). Supplementary Table 2 illustrates the gel-to-gel variability of 11 selected protein spots.

Table 1. Identity of protein spots showing either increase (up) or decrease (down) in intensity in cauda epididymal spermatozoa compared to the intensity in caput epididymal spermatozoa (P < 0.05) of hamster.

| Serial Number | Spot codea | Protein | Intensity Mean ± SD | Intensity change in cauda epididymal spermatozoa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caput | Cauda | ||||

| Metabolism / ATP production (20.0 %) | |||||

| 1 | 20 | Dihydrolipoamide S-acetyltransferase | 890.3 ± 22.2 | 1154.4 ± 93.2 | 1.3 up |

| 2 | 58 | ATP synthase b-subunit, mitochondrial* | 420.8 ± 97.3 | 1209.9 ± 444.0 | 2.8 up |

| 3 | 66 | ATP-specific succinyl-CoA ligase, b-subunit | 186.0 ± 18.9 | 60.4 ± 8.8 | 3.1 down |

| 4 | 72 | Enolase 1- α* | 70.5 ± 12.9 | 38.3 ± 5.9 | 1.8 down |

| 5 | 95 | N- acetyl-glucosamine kinase | 177.7 ± 26.4 | 122.4 ± 9.1 | 1.5 down |

| 6 | 44 | Dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase, mitochondrial | 478.7 ± 129.4 | 720.2 ± 72.0 | 1.5 up |

| Structural proteins (10.0%) | |||||

| 7 | 62 | γ-actin | 972.8 ± 128.7 | 277.3 ± 14.5 | 3.5 down |

| 8 | 69 | γ-actin | 206.8 ± 34.9 | 40.1 ± 4.7 | 5.1 down |

| 9 | 70 | Outer dense fiber protein /cenexin 1 | 122.7 ± 35.5 | 46.0 ± 20.8 | 2.7 down |

| Stress proteins and chaperone (53.4%) | |||||

| 10 | 34 | Heat shock protein 60* | 190.0 ± 24.9 | 126.7 ± 35.7 | 1.5 down |

| 11 | 35 | Heat shock protein 60 * | 364.5 ± 44.1 | 290.2 ± 16.5 | 1.2 down |

| 12 | 28 | Heat shock-related 70 kDa protein 2* | 117.0 ± 12.3 | 26.2 ± 9.2 | 4.5 down |

| 13 | 25 | Stress 70 protein | 341.7 ± 54.0 | 71.6 ± 11.7 | 4.8 down |

| 14 | 26 | Stress 70 protein | 318.9 ± 51.2 | 220.6 ± 22.2 | 1.9 down |

| 15 | 6 | Osmotic stress protein 94 | 172.6 ± 34.2 | 46.2 ± 27.5 | 3.7 down |

| 16 | 1 | Tumor rejection antigen GP96* | 96.4 ± 56.9 | - | unique to caput |

| 17 | 2 | Tumor rejection antigen GP96* | 326.7 ± 56.6 | - | unique to caput |

| 18 | 3 | Tumor rejection antigen GP96* | 235.3 ± 50.2 | - | unique to caput |

| 19 | 30 | 78 kDa glucose regulated protein precursor (GRP78)* | 196.0 ± 9.2 | - | unique to caput |

| 20 | 31 | 78 kDa glucose regulated protein precursor (GRP78)* | 703.7 ± 71.9 | - | unique to caput |

| 21 | 32 | 78 kDa glucose regulated protein precursor (GRP78)* | 595.1 ± 171.0 | - | unique to caput |

| 22 | 33 | 78 kDa glucose regulated protein precursor (GRP78)* | 378.5 ± 106.9 | - | unique to caput |

| 23 | 38 | Endoplasmic reticulum protein (ERp57) | 267.1 ± 81.5 | - | undetected |

| 24 | 39 | Endoplasmic reticulum protein (ERp57) | 284.9 ± 64.6 | - | undetected |

| 25 | 40 | Endoplasmic reticulum protein (ERp57) | 492.2 ± 81.1 | - | undetected |

| Antioxidant and detoxifying enzymes (3.3%) | |||||

| 26 | 103 | Peroxiredoxin 6 | 318.7 ± 61.3 | 636.3 ± 113.1 | 2.0 up |

| Other proteins (13.3%) | |||||

| 27 | 27 | ATPase, H+ transporting, lysosomal V1 subunit A | 146.1 ± 9.7 | 68.0 ± 19.9 | 2.1 down |

| 28 | 75 | Tu translation elongation factor | 75.3 ± 6.3 | 30.6 ± 5.9 | 2.5 down |

| 29 | 91 | Prohibitin | 151.8 ± 23.2 | 277.1 ± 32.5 | 1.8 up |

| 30 | 100 | Fibrinogen-like protein 1 | - | 453.8 ± 63.8 | unique to cauda |

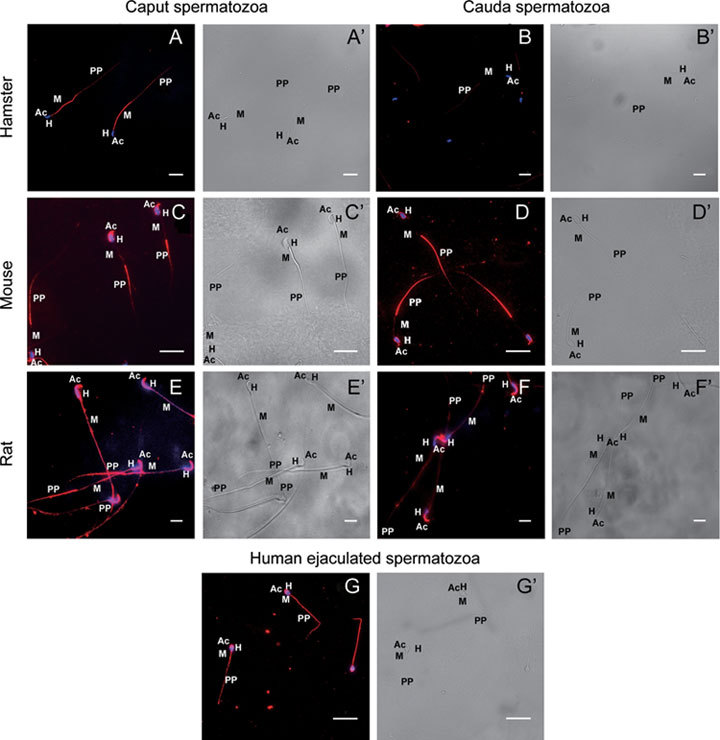

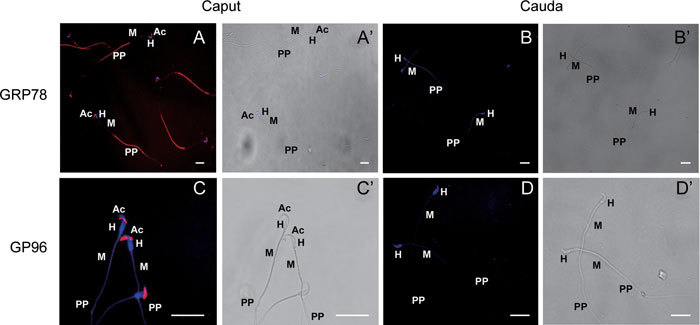

Immunofluorescent localization of ERp57, GRP78 and GP96 in the spermatozoa

Immunofluorescent studies clearly demonstrated that ERp57 is localized in the mid-piece of the caput epididymal spermatozoa of hamster, with faint staining in the principal piece (Figure 2A). In contrast, the cauda epididymal spermatozoa showed very faint staining in the principal piece and no localization in the mid-piece (Figure 2B). The observed differential localization of ERp57 in the caput and cauda spermatozoa of hamster prompted us to undertake further studies on on the localization of ERp57 in the caput and cauda spermatozoa of mouse and rat and in the ejaculated spermatozoa of man (Figure 2C–G). These studies indicated that localization of ERp57 in the spermatozoa varied depending on the animal and in some animals depending on the region of the epididymis. For instance, in mouse, in both the caput and cauda spermatozoa (Figure 2C and D) ERp57 was localized in the acrosome and principal piece of the flagellum. In contrast, in the rat caput epididymal spermatozoa (Figure 2E) ERp57 was seen to be present in the head, mid and principal piece, but the cauda spermatozoa showed localization only in the acrosome (Figure 2F). Ejaculated human spermatozoa (Figure 2G) showed localization of ERp57 in the entire flagellum and in the head region. Immunofluorescent studies were also carried out with two other proteins, namely GRP78 and GP96, using hamster caput and cauda epididymal spermatozoa (Figure 3A–D). GRP78 appeared to be localized only in the acrosome and principal piece of caput spermatozoa and was absent in cauda spermatozoa (Figure 3A and B). GP96 was also absent in the cauda spermatozoa but localized only to the acrosome in the caput spermatozoa (Figures 3C and D).

Figure 2.

Immunofluorescent localization of ERp57 in the spermatozoa of hamster (A, B), mouse (C, D), rat (E, F) and humans (G). A', B', C', D' and E', F′ and G′ are the corresponding brightfield images of A, B, C, D and E, F and G. Caput epididymal spermatozoa of hamster (A) show intense staining in the mid-piece [M], with faint staining in the principal piece [PP]. Cauda epididymal spermatozoa of hamster (B) did not show any positive staining in the mid-piece [M], but showed faint staining in the principal piece [PP]. In mouse, both caput and cauda epididymal spermatozoa (C, D) staining are observed in the acrosome [Ac] and principal piece [PP]. In rat, the caput epididymal spermatozoa (E) showed staining both in the head [H] and in the entire flagellum, whereas the cauda epididymal spermatozoa (F) showed staining limited only to the acrosome [Ac]. Ejaculated human spermatozoa (G) show staining in the acrosome [Ac] and entire flagellum. 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was used for nuclear staining. Scale bars = 20 μm.

Figure 3.

Immunofluorescent localization of GRP78 and GP96 in hamster caput and cauda epididymal spermatozoa. Immunofluorescence localization of GRP78 showed an intense staining in the acrosome (Ac) and principal piece (PP) of caput spermatozoa of hamster (A), while GP96 showed intense staining only in the acrosome (Ac) of caput epididymal spermatozoa (C). Cauda epididymal spermatozoa did not show any positive staining for either GRP78 (B) or GP96 (D) proteins. A', B', C', D' are the corresponding brightfield images of A, B, C, D. 'H' denotes the head and 'M' denotes the mid-piece of the spermatozoa. Scale bars = 20 μm.

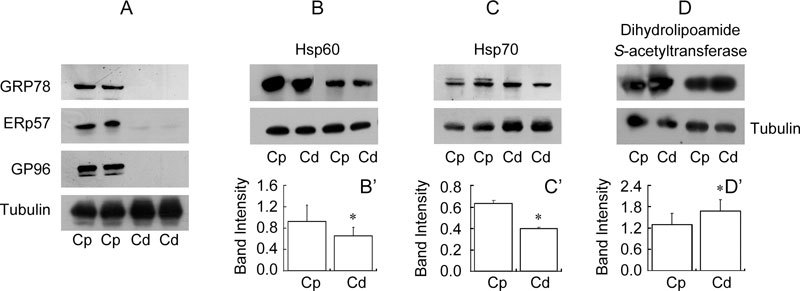

Validation of protein changes by immunoblot analysis

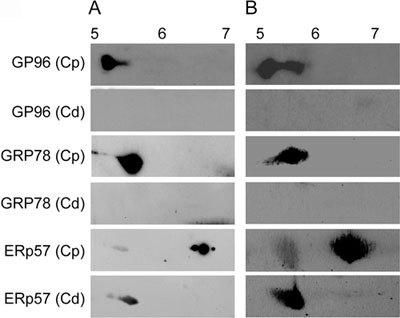

In order to validate the changes in intensity of proteins observed in the 2D gels of the caput and cauda epididymal spermatozoa of hamster, immunoblot analysis of six of the proteins, viz. ERp57, GRP78, GP96, Hsp60, Hsp70 and dihydrolipoyl S-acetyltransferase, was carried out. The results clearly demonstrated that ERp57, GRP78 and GP96 were predominantly present in the caput and totally absent in the cauda spermatozoa (Figure 4A), thus confirming the proteome data, which also indicated that both these proteins (GP96 and GRP78) were unique to the caput epididymal spermatozoa (Table 1). Western blot analysis also revealed that the intensities of Hsp60 and Hsp70 were significantly decreased (Mann-Whitney test, P < 0.05) in cauda as compared with caput spermatozoa (Figures 4B, B′, C and C′), thus confirming the proteome data. Dihydrolipoyl S-acetyltransferase showed an increase (P < 0.05)during maturation, thus confirming the proteome data (Figures 4D and D′, Table 1). The band intensities were normalized with respect to tubulin, which was used as an internal control.

Figure 4.

Immunoblot analysis of GRP78, ERp57, GP96 (A), Hsp60 (B), Hsp70 (C) and dihydrolipoamide S-acetyltransferase (D) using hamster caput [Cp] and cauda [Cd] epididymal sperm lysates. Densitometry analysis of Hsp60 (B′) and Hsp70 (C′) showed a decrease in intensity in cauda epididymal spermatozoa, while dihydrolipoamide S-acetyltransferase (D′) showed an increase in intensity in cauda epididymal spermatozoa. *P < 0.05, Mann-Whitney test, compared with Cp. Tubulin was used as an internal control.

To further validate the qualitative changes observed in the 2D proteome of caput and cauda epididymal spermatozoa of hamster, immunoblot analysis of three proteins was performed by resolving the respective lysates in the 5–8 and 3–10 pI range (Figures 5A and B). The results clearly demonstrated that GP96 and GRP78 are present only in the caput and are completely absent in cauda epididymal spermatozoa, whereas ERp57 seems to be present in both the caput and the cauda epididymal spermatozoa. It was also observed that ERp57 exists as two different pI isoforms, with a pI of 6.5 and 5.5 specific to the caput and cauda epididymal spermatozoa, respectively. Based on these results, it appears that the inability to detect ERp57 in cauda spermatozoa may be because of its low quantity and changed pI.

Figure 5.

Immunoblot analysis of GRP78, ERp57 and GP96 using hamster caput [Cp] and cauda [Cd] epidydimal sperm lysates resolved in the pI range of 5–8 (A) and 3–10 (B).

Discussion

Earlier studies have indicated that certain proteins increased or decreased in the cauda epididymal spermatozoa either by acquisition/removal of proteins from/into the epididymal fluid or by post-translational modifications 2, 9, 13. A total of 113 protein spots (representing 61 proteins) were unambiguously identified (Supplementary Table 1), and only 14 of these proteins have been reported earlier in the hamster protein database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov; Supplementary table 1). Thus, this study adds 47 proteins more to the protein database of the hamster and also reports the identification of Ezrin and fibrinogen-like protein 1, which were not reported from the proteome of mammalian spermatozoa (Supplementary Table 1).

Twelve protein spots (corresponding to six proteins) identified as differentials in this study were also reported by Baker et al. 11 for the rat spermatozoa (Table 1). ATP synthase beta subunit showed similar trends in both species. Heat shock-related 70 kDa protein 2 and Stress 70 protein, which were downregulated in the hamster during maturation, showed an upregulation in rat. GP96 and GRP78 showed varying trends in the rat spermatozoa (GP96 downregulated by 2.7-fold and GRP78 upregulated by 1.77-fold), while these proteins were unique to caput spermatozoa in the hamster.

Comparison of the proteome of hamster spermatozoa with that of other mammalian spermatozoa indicated that a significant number of the hamster sperm proteins have also been reported earlier in the proteome of spermatozoa from mouse 22, 23, bull 40 and man 28, thus indicating that these proteins were conserved in mammalian spermatozoa. Some of the proteins in the hamster sperm proteome existed in several pI isoforms (Supplementary Table 1), thus confirming earlier studies in other cells, including spermatozoa 22, 23, 28, 41, 42, 43. Further, functional characterization of the 113 protein spots indicated that the majority of the proteins were involved in generating energy required for sperm motility (such as proteins involved in metabolism and ATP production), in maintaining the structural integrity of the spermatozoon (such as tektin, tubulin, outer dense fibres, etc.), in providing protection from stress (such as chaperones, stress-proteins and detoxifying enzymes), and in signaling and transport or other functions of the spermatozoa (Supplementary Table 1).

As of date, protein composition changes during epididymal maturation have so far been carried out only in rat spermatozoa. Both the studies indicated significant changes (43 and 60 protein spots, respectively) 8, 11, but only eight and seven proteins, respectively, were identified in the two studies. The two studies showed a discrepancy with respect to phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein, with one reporting a decrease 8 and the other an increase 11. The reasons for the discrepancy have not been addressed. When the changes in these two studies were compared with the present study, it was observed that the ATP synthase β subunit that increased and that decreased in intensity in rat spermatozoa during epididymal maturation 11 also showed a similar trend in the cauda epididymal spermatozoa of hamster (Table 1). Thus, based on the limited data, generalization may not be feasible at this time.

Certain proteins increased in the cauda epididymal spermatozoa of hamster. Functionally these proteins could be grouped as those involved in ATP generation (dihydrolipoamide S-acetyltransferase, ATP synthase β subunit and dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase), in reactive oxygen species (ROS) protection (peroxiredoxin 6) and Prohibitin, a protein of which the function is still not clear. Increase in these proteins is commensurate with the acquisition of motility potential in cauda epididymal spermatozoa, which requires energy in the form of ATP and post-translational modification of proteins 38, 39. For instance, the ATP synthase β subunit was shown to be associated with motility initiation in hamster spermatozoa 44 and in epididymal maturation in rat spermatozoa 11. The activity of dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase is not apparently required for hamster sperm motility but is crucial for hamster sperm acrosome reaction 45, 46. Increase in peroxiredoxin 6 in cauda epididymal spermatozoa may be attributed to the ability of these enzymes to protect the spermatozoa from elevated levels of reactive oxygen species 47. As mentioned earlier, the exact function of prohibitin is not clear, but Thompson et al. 48 suggested that prohibitin facilitates the marking of defective spermatozoa in the epididymis for degradation.

Apart from the above proteins, which increased during epididymal maturation, it was observed that certain proteins decreased in hamster spermatozoa during epididymal maturation (Table 1). These proteins could be categorized as structural proteins (actin and outer dense fiber protein), heat shock proteins (Hsp60 and Hsp70), stress proteins (the osmotic stress protein 94 and stress 70 protein), ATPases, metabolic enzymes (succinyl-CoA ligase, N-acetyl-glucosamine kinase), and a miscellaneous protein such as Tu translation elongation factor. Hamster epididymal proteins such as P26h, P25b and P34H 18 were not identified in the study. This probably implies that the epididymal proteins of hamster are not tightly bound to the spermatozoa and are probably washed away during the processing of the spermatozoa.

A few of these changes may be relevant to sperm motility acquisition. For instance, it has been shown that the immotile caput epididymal spermatozoa of guinea pig contained a significantly higher F-actin relative to motile spermatozoa from the vas deferens 49. Further, in hamster mature spermatozoa, it was observed that sperm tails are 7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazole phallaoidin negative, indicating that either G-actin or depolymerized actin oligomers are present rather than bundles of actin filaments 50. This also implies that as spermatozoa pass through the epididymis the depolymerization of actin might take place, thus converting filamentous F-actin to G-actin subunits. The ODFs are sperm tail-specific cytoskeletal structures and it is suggested that it provides tensile strength to the sperm and protects the tail against shearing injury during epididymal transport 51, 52. Therefore, it is surprising that one of the 11 isoforms exhibits a decrease in the level in cauda epididymal spermatozoa. Although not much is known about the expression levels of ODF isoforms and their relation to sperm motility in rodent species, studies in asthenozoospermic men surprisingly revealed higher expression of one of the ODF isoforms in these spermatozoa, with low motility when compared with spermatozoa from normozoospermic men 32. Zhao et al. 32 explained this result by suggesting that this form may be upregulated to compensate for the other ODFs, which may be functionally compromised.

In the cauda epididymal spermatozoa of hamster, Hsp60, Hsp70 and the osmotic stress protein 94 are decreased. Hsp60 and Hsp70 have also been identified in mammalian spermatozoa 53, 54. It is difficult to explain why there is a decrease in heat shock proteins in hamster cauda epididymal spermatozoa though HSPs may be involved in regulating spermatogenesis 55. A decrease in the intensity of enolase-1-α in the cauda epididymal spermatozoa of hamster was observed, thus confirming the observations in rat spermatozoa 11. Moreover, one of the isoforms of Enolase, ENO-alpha-alpha, is shown to be associated with abnormal and/or immature spermatozoa 56. N-acetyl-glucosamine kinase belongs to the sugar kinase/Hsp70/actin super family that catalyzes phosphoryl transfer from ATP to their respective substrates. A study by Hinderlich et al. 57 showed higher transcript expression of this gene in the mouse testis, suggesting an important function of this gene in male reproductive functions. Murdoch and Jones 58 also mention that N-acetyl glucosamine, the substrate for this enzyme, acts as an energy source for spermatozoa only after being phosphorylated, thereby demonstrating the importance of N-acetyl-glucosamine kinase for sperm function. Decreased expression of this protein during epididymal maturation could mean a reduced preference for N-acetyl glucosamine as an energy substrate.

In addition to the above proteins, which either increased or decreased in levels in hamster spermatozoa during epididymal maturation, a few of the proteins such as GP96 and GRP78 were absent in cauda epididymal spermatozoa, as also confirmed by immunoblot studies (Figures 4 and 5). These observations are not in accordance with earlier observations made on rat spermatozoa wherein GP96 was shown to decrease and GRP78 to increase during epididymal transit 11. However, localization of ERp57 in human spermatozoa was observed to be similar to the earlier studies 60, 61 (Figure 2G). ERp57 has been shown to have a role in sperm–egg fusion in mice 60 and human 61 spermatozoa.

Fibrinogen-like protein 1 was the only protein that was unique to the cauda epididymal spermatozoa of hamster. Olson et al. 62 demonstrated that the epithelial cells of hamster epididymis exhibit region-specific expression and secretion of fibrinogen-related protein fgl2, and implicated it in disposal of defective spermatozoa. It is possible that this protein gets adsorbed on spermatozoa from cauda epididymal fluid.

In summary, we have established the proteome of hamster spermatozoa and also identified the proteins undergoing changes during epididymal transit. Most of the upregulated proteins in our study are related directly or indirectly to acquisition of motility potential of spermatozoa during epididymal maturation. Although this study provides information about the changes in spermatozoal proteins that occur during epididymal maturation, further studies on the functional characterization of these proteins could help in proper understanding of the molecular basis of epididymal maturation. The mechanism of differential expression of these proteins may be another line of study. Detailed studies on the proteins involved in motility acquisition could help in revealing the cause behind asthenozoospermia.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Priyanka Rai for her valuable suggestions and technical help.

Footnotes

Supplementary information accompanies the paper on Asian Journal of Andrology website (http://www.nature.com/aja).

Supplementary Information

Identification of 113* protein spots of hamster spermatozoa by MALDI MS and MS/MS

Variability in the intensity of 11 protein spots from caput and cauda epididymal spermatozoa of hamster.

References

- Devi LG, Shivaji S. Computerized analysis of the motility parameters of hamster spermatozoa during maturation. Mol Reprod Dev. 1994;38:94–106. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080380116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper TG. Interactions between epididymal secretions and spermatozoa. J Reprod Fertil Supp. 1998;53:119–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean DJ. Spermatogonial stem cell transplantation and testicular function. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;322:21–31. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-0009-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall GA. New insights into epididymal biology and function. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15:213–27. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmn055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagimachi R.Mammalian fertilizationIn: Knobil K, Neill JD, editors. The Physiology of ReproductionNew York, NY: Raven Press; 1994p189–317. [Google Scholar]

- Christova Y, James P, Mackie A, Cooper TG, Jones R. Molecular diffusion in sperm plasma membranes during epididymal maturation. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;216:41–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.10.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivaji S, Scheit KH, Bhargava PM.Proteins Secreted by the EpididymisNew York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1990p35–84. [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Qu F, Xia L, Guo Q, Ying X, et al. Identification and characterization of ERp29 in rat spermatozoa during epididymal transit. Reproduction. 2007;133:575–84. doi: 10.1530/REP-06-0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitken RJ, Nixon B, Lin M, Koppers AJ, et al. Proteomic changes in mammalian spermatozoa during epididymal maturation. Asian J Androl. 2007;9:554–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7262.2007.00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devi KU, Ahmad MB, Shivaji S. A maturation-related differential phosphorylation of the plasma membrane proteins of the epididymal spermatozoa of the hamster by endogenous protein kinases. Mol Reprod Dev. 1997;47:341–50. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199707)47:3<341::AID-MRD13>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker MA, Witherdin R, Hetherington L, Cunningham Smith K, Aitken RJ. Identification of post-translational modifications that occur during sperm maturation using difference in two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Proteomics. 2005;5:1003–12. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatti JL, Castella S, Dacheux F, Ecroyd H, Métayer S, et al. Post-testicular sperm environment and fertility. Anim Reprod Sci. 2004;8283:321–39. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toshimori K. Biology of spermatozoa maturation: an overview with an introduction to this issue. Microsc Res Tech. 2003;61:1–6. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voglmayr JK, Fairbanks G, Jackowitz M, Colella JR. Post testicular developmental changes in the ram sperm cell surface and their relationship to luminal fluid proteins of the reproductive tract. Biol Reprod. 1980;22:655–67. doi: 10.1093/biolreprod/22.3.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaquier JA, Cameo MS, Cuasnicu PS, Gonzalez Echeverria MF, Piñeiro L, et al. The role of epididymal factors in human sperm fertilizing ability. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1988;541:292–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb22266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yenugu S, Hamil KG, Grossman G, Petrusz P, French FS, et al. Identification, cloning and functional characterization of novel sperm associated antigen 11 (SPAG11) isoforms in the rat. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2006;4:23. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-4-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen DJ, Rochwerger L, Ellerman DA, Morgenfeld MM, Busso D, et al. Relationship between the association of rat epididymal protein 'DE' with spermatozoa and the behavior and function of the protein. Mol Reprod Dev. 2000;56:180–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(200006)56:2<180::AID-MRD9>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Légaré C, Bérubé B, Boué F, Lefièvre L, Morales CR, et al. Hamster sperm antigen P26h is a phosphatidylinositol-anchored protein. Mol Reprod Dev. 1999;52:225–33. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199902)52:2<225::AID-MRD14>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessard C, Parent S, Leclerc P, Bailey JL, Sullivan R. Cryopreservation alters the levels of the bull sperm surface protein P25b. J Androl. 2000;21:700–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Légaré C, Gaudreault C, St-Jacques S, Sullivan R. P34H sperm protein is preferentially expressed by the human corpus epididymidis. Endocrinology. 1999;140:3318–27. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.7.6791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson RT, Sivashanmugam P, Hall SH, Hamil KG, Moore PA, et al. Cloning and sequencing of human Eppin: a novel family of protease inhibitors expressed in the epididymis and testis. Gene. 2001;270:93–102. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00462-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker MA, Hetherington L, Reeves GM, Aitken RJ. The mouse sperm proteome characterized via IPG strip prefractionation and LC-MS/MS identification. Proteomics. 2008;8:1720–30. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200701020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker MA, Hetherington L, Reeves GM, Aitken RJ. The rat sperm proteome characterized via IPG strip prefractionation and LC-MS/MS identification. Proteomics. 2008;8:2312–21. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenner GP, Johnson LA, Hruschka WR, Bolt DJ. Two-dimensional electrophoresis and densitometric analysis of solubilized bovine sperm plasma membrane proteins detected by silver staining and radioiodination. Arch Androl. 1992;29:21–32. doi: 10.3109/01485019208987705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalancette C, Faure RL, Leclerc P. Identification of the proteins present in the bull sperm cytosolic fraction enriched in tyrosine kinase activity: a proteomic approach. Proteomics. 2006;6:4523–40. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugaya M, Sunaga T, Toda T, Akama K. Proteome analysis of boar sperm and changes of proteins with sperm maturation in epididymis. Seikagaku. 2003;75:839. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston DS, Wooters J, Kopf GS, Qiu Y, Roberts KP. Analysis of the human sperm proteome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1061:190–202. doi: 10.1196/annals.1336.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Heredia J, Estanyol JM, Ballescà JL, Oliva R. Proteomic identification of human sperm proteins. Proteomics. 2006;6:4356–69. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitken RJ, Baker MA. The role of proteomics in understanding sperm cell biology. Int J Androl. 2008;31:295–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2007.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliva R, Martínez-Heredia J, Estanyol JM. Proteomics in the study of the sperm cell composition differentiation and function. Syst Biol Reprod Med. 2008;54:23–36. doi: 10.1080/19396360701879595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliva R, de Mateo S, Estanyol JM. Sperm cell proteomics. Proteomics. 2009;9:1004–17. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Huo R, Wang FQ, Lin M, Zhou ZM, et al. Identification of several proteins involved in regulation of sperm motility by proteomic analysis. Fertil Steril. 2007;87:436–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domagala A, Pulido S, Kurpisz M, Herr JC. Application of proteomic methods for identification of sperm immunogenic antigens. Mol Hum Reprod. 2007;13:437–44. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gam026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kota V, Dhople VM, Shivaji S. Tyrosine phosphoproteome of hamster spermatozoa: role of glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 2 in sperm capacitation. Proteomics. 2009;9:1809–26. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkel AW, Bieger SC. Quantification of proteins dissolved in an electrophoresis sample buffer. Anal Biochem. 1994;223:329–31. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson NL, Esquer-Blasco R, Hofmann JP, Anderson NG. A two-dimensional gel database of rat liver proteins useful in gene regulation and drug effect studies. Electrophoresis. 1991;12:907–30. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150121110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevchenko A, Tomas H, Havlis J, Olsen JV, Mann M. In-gel digestion for mass spectrometric characterization of proteins and proteomes. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2856–60. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RM, Eriksson RL, Gerton GL, Moss SB. Relationship between sperm motility and the processing and tyrosine phosphorylation of two human sperm fibrous sheath proteins pro-hAKAP82 and hAKAP82. Mol Hum Reprod. 1999;5:816–24. doi: 10.1093/molehr/5.9.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki K. Energy metabolism and sperm function. Soc Reprod Fertil Suppl. 2007;65:309–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peddinti D, Nanduri B, Kaya A, Feugang JM, Burgess SC, et al. Comprehensive proteomic analysis of bovine spermatozoa of varying fertility rates and identification of biomarkers associated with fertility. BMC Syst Biol. 2008;2:19. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-2-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman IM. Actin isoforms. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1993;5:48–55. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(05)80007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cvoro A, Korać A, Matić G. Intracellular localization of constitutive and inducible heat shock protein 70 in rat liver after in vivo heat stress. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;265:27–35. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000044312.59958.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn B, Muthana M, Hopkinson K, Slack LK, Mirza S, et al. Analysis of purified gp96 preparations from rat and mouse livers using 2-D gel electrophoresis and tandem mass spectrometry. Biochimie. 2006;88:1165–74. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujinoki M, Kawamura T, Toda T, Ohtake H, Shimizu N, et al. Identification of the 58-kDa phosphoprotein associated with motility initiation of hamster spermatozoa. J Biochem. 2003;134:559–65. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvg174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra K, Shivaji S. Novel tyrosine-phosphorylated post-pyruvate metabolic enzyme dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase involved in capacitation of hamster spermatozoa. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:887–99. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.022780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Kota V, Shivaji S. Hamster sperm capacitation: role of pyruvate dehydrogenase A and dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase. Biol Reprod. 2008;79:190–9. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.066704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernet P, Aitken RJ, Drevet JR. Antioxidant strategies in the epididymis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;216:31–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.10.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson WE, Ramalho-Santos J, Sutovsky P. Ubiquitination of prohibitin in mammalian sperm mitochondria: possible roles in the regulation of mitochondrial inheritance and sperm quality control in the regulation of mitochondrial inheritance and sperm quality control. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:254–60. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.010975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azamar Y, Uribe S, Mújica A. F-actin involvement in guinea pig sperm motility. Mol Reprod Dev. 2007;74:312–20. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouquet JP, Kann ML, Dadoune JP. Immunoelectron microscopic distribution of actin in hamster spermatids and epididymal capacitated and acrosome-reacted spermatozoa. Tissue Cell. 1990;22:291–300. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(90)90004-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen C, Füzesi L, Hoyer-Fender S. Outer dense fibre proteins from human sperm tail: molecular cloning and expression analyses of two cDNA transcripts encoding proteins of ∼70 kDa. Mol Hum Reprod. 1999;5:627–35. doi: 10.1093/molehr/5.7.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltz JM, Williams PO, Cone RA. Dense fibers protect mammalian sperm against damage. Biol Reprod. 1990;43:485–91. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod43.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpe S, Galeati G, Bernardini C, Tamanini C, Mari G, et al. Comparative immunolocalization of heat shock proteins (Hsp)-60, -70, -90 in boar, stallion, dog and cat spermatozoa. Reprod Domest Anim. 2008;43:385–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2007.00918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachance C, Fortier M, Thimon V, Sullivan R, Bailey JL, et al. Localization of Hsp60 and Grp78 in the human testis epididymis and mature spermatozoaInt J Androl Published Online: 20 January 2009; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sarge KD, Cullen KE. Regulation of hsp expression during rodent spermatogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1997;53:191–7. doi: 10.1007/PL00000591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Force A, Viallard JL, Grizard G, Boucher D. Enolase isoforms activities in spermatozoa from men with normospermia and abnormospermia. J Androl. 2002;23:202–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinderlich S, Berger M, Schwarzkopf M, Effertz K, Reutter W. Molecular cloning and characterization of murine and human N-acetylglucosamine kinase. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:3301–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch RN, Jones RC. The metabolic properties of spermatozoa from the epididymis of the tammar wallaby, Macropus eugenii. Mol Reprod Dev. 1998;49:92–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199801)49:1<92::AID-MRD10>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellerman DA, Myles DG, Primakoff P. A role for sperm protein disulfide isomerase activity in gamete fusion: evidence for the participation of ERp57. Dev Biol. 2006;10:831–7. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachance C, Bailey JL, Leclerc P. Expression of hsp60 and grp78 in the human endometrium and oviduct and their effect on sperm functions. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:2606–14. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Wu J, Huo R, Mao Y, Lu Y, et al. ERp57 is a potential biomarker for human fertilization capability. Mol Hum Reprod. 2007;13:633–9. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gam049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson GE, Winfrey VP, NagDas SK, Melner MH. Region-specific expression and secretion of the fibrinogen-related protein, fgl2, by epithelial cells of the hamster epididymis and its role in disposal of defective spermatozoa. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51266–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410485200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Identification of 113* protein spots of hamster spermatozoa by MALDI MS and MS/MS

Variability in the intensity of 11 protein spots from caput and cauda epididymal spermatozoa of hamster.