Abstract

In mammals, CCR7 is the chemokine receptor for the CCL19 and CCL21 chemokines, molecules with a major role in the recruitment of lymphocytes to lymph nodes and Peyer's patches in the intestinal mucosa, especially naïve T lymphocytes. In the current work, we have identified a CCR7 orthologue in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) that shares many of the conserved features of mammalian CCR7. The receptor is constitutively transcribed in the gills, hindgut, spleen, thymus and gonad. When leukocyte populations were isolated, IgM+ cells, T cells and myeloid cells from head kidney transcribed the CCR7 gene. In blood, both IgM+ and IgT+ B cells and myeloid cells but not T lymphocytes were transcribing CCR7, whereas in the spleen, CCR7 mRNA expression was strongly detected in T lymphocytes. In response to infection with viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus (VHSV), CCR7 transcription was down-regulated in spleen and head kidney upon intraperitoneal infection, whereas upon bath infection, CCR7 was up-regulated in gills but remained undetected in the fin bases, the main site of virus entry. Concerning its regulation in the intestinal mucosa, the ex vivo stimulation of hindgut segments with Poly I:C or inactivated bacteria significantly increased CCR7 transcription, while in the context of an infection with Ceratomyxa shasta, the levels of transcription of CCR7 in both IgM+ and IgT+ cells from the gut were dramatically increased. All these data suggest that CCR7 plays an important role in lymphocyte trafficking during rainbow trout infections, in which CCR7 appears to be implicated in the recruitment of B lymphocytes into the gut.

Keywords: Chemokines, Chemokine receptors, CCR7, Rainbow trout, Mucosal immunity, Lymphocytes

1. Introduction

In rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) 22 different genes coding for chemokines, or chemotactic cytokines, have been identified to date (Alejo and Tafalla, 2011). In all vertebrates, chemokines can be further divided into subfamilies according to the position of conserved cysteines in their sequence. Among these groups, the CC subfamily (with two contiguous conserved cysteines) is the most numerous with 28 members in mammals and 18 in rainbow trout (Laing and Secombes, 2004). A high level of variation in the number of genes within the CC subgroup in the different fish species is evident, ranging from these 18 genes present in trout to 81 that have been described in zebrafish (Danio rerio) (Nomiyama et al., 2008). These differences indicate extensive duplication events that, together with the fact that chemokines are rapidly changing proteins (Bao et al., 2006; Nomiyama et al., 2008), make the establishment of true orthologues between fish and mammalian chemokine genes very difficult. An attempt to group fish CC chemokines was made by Peatman and Liu (2007) who established seven large groups of fish CC chemokines through phylogenetic analysis: the CCL19/21/25 group, the CCL20 group, the CCL27/28 group, the CCL17/22 group, the macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP) group, the monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP) group and a fish-specific group.

Chemokines attract and modulate the immune function of the recruited cells through interaction with G protein linked chemokine receptors that form a family of structurally and functionally related proteins (Horuk, 1994). Systematic searches for chemokine receptors in fish genomes and expressed sequence tag (EST) databases have identified 26 genes in zebrafish (DeVries et al., 2006; Nomiyama et al., 2008) for at least 111 chemokine genes, as compared to the 18 chemokine receptors for 44 chemokines known in humans. Although promiscuity in ligand binding is a known property of chemokine receptors, the large difference in numbers between chemokine and their putative receptors in zebrafish has suggested that fish chemokines may bind to receptors substantially different from known mammalian chemokine receptors (Nomiyama et al., 2008). Interestingly, the pufferfish, which only encodes 18 different chemokines as compared to the 111 genes of zebrafish, still has a comparable number of putative receptor genes (20) (DeVries et al., 2006). In rainbow trout, only the sequences of CCR9, CXCR4 and CXCR8 have been reported to date (Daniels et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 2002). The CCR9 sequence was originally reported as CCR7, however, recent analysis including the human CCR9 sequence has identified it as a CCR9 homologue and it is now cataloged as such in the GenBank database (Accession number NM_001124610).

In mammals, CCR7 is the receptor for both CCL19 and CCL21 (Forster et al., 2008). CCR7 is highly expressed in naive T cells and is very important for their normal trafficking (Hwang et al., 2007), since the expression of CCL21 in the luminal side of high endothelial venules facilitates their entrance in the lymph nodes (Gretz et al., 2000). B lymphocytes on the other hand, express CCR7 at significantly lower levels, but CCR7 expression is increased upon engagement of the B cell receptor, thus facilitating T–B interactions within the lymph node (Okada et al., 2005). CCR7 is also up-regulated in dendritic cells (DCs) during their maturation, leading them from their niches in peripheral tissues to the lymph nodes (Sanchez-Sanchez et al., 2006). Apart from the maturing DC populations, a subset of DCs with an exclusive phenotype including CCR7 expression are thought to contribute to peripheral immune tolerance against self-antigens (Ohl et al., 2004).

In gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), the desensitization of CCR7 in wild-type mice (Warnock et al., 2000), the genetic disruption of CCR7 (Forster et al., 2008), or natural mutations in the CCR7 ligands CCL19 and CCL21 (Luther et al., 2000; Warnock et al., 2000), all lead to a reduced homing of T cells into the Peyer's patches present in the gut. Interestingly, B cell homing to these secondary lymphoid tissues has shown to be less CCR7 dependent (Okada et al., 2002; Forster et al., 2008).

In the current study, we have identified and cloned a CCR7 homologue in rainbow trout. Phylogenetic analysis of the newly identified sequence reveals a closer sequence similarity to mammalian CCR7 sequences than the previous discovered trout chemokine receptor, confirming the change in ascription of that gene previously reported as trout. We have studied both its constitutive transcription in different rainbow trout tissues and cell types, and its regulation of transcription in response to viral hemorrhagic septicaemia virus (VHSV) intraperitoneal or bath infection as well as in response to Ceratomyxa shasta, a parasite with a strong tropism for the gut. Our studies reveal a major role of CCR7 in the mobilization of lymphocytes to mucosal sites such as gills or intestine, but not to the skin. Undoubtedly, understanding the mechanisms through which chemokine receptors are regulated will be essential for the delimitation of the roles of the target chemokines and for understanding lymphocyte trafficking in fish.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cloning of rainbow trout CCR7

The previously identified D. rerio CCR7 sequence (GenBank Accession number NM_001098743.1) was used to search public EST databases for similar rainbow trout sequences. All sequences identified as chemokine receptor-like molecules were translated using the Clone Manager suite 7 program. Translated sequences were compared with mammalian CCRs using BLAST (http://www.blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), thus identifying two rainbow trout expressed tags (Accession numbers CX721232 and CU065128) that encoded fragments of a CCR7-like molecule.

The sequences lacked a stop codon, therefore 3′RACE was performed to obtain the complete sequence using cDNA obtained from peripheral blood leukocytes (PBLs) and the primers indicated in Table 1 using the 3′RACE System for Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends from Invitrogen. An overlapping fragment was amplified which contained the final segment of the CCR7 coding sequence and the 3′ untranslated region (UTR). Primers were then designed to amplify the full coding sequence.

Table 1.

Primers used for the CCR7 cloning and real time RT-PCR expression.

| Gene | Name | Sequence (5′–3′) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCR7 | RACE-F | CCTGAGGTGCTGCCTCAACCCCTTTG | 3′RACE |

| CCR7 | RACE-nF | CCTCCTGAAGCTGCTGAAGGATCTGG | 3′RACE |

| CCR7 | FULL F | CACCATGGCTACAGAGTTCATCACTGATTTCAC | Full sequence |

| CCR7 | FULL R | TTAGGGGGAGAAAGTGGTTGTGGTCT | Full sequence |

| CCR7 | CCR7-RT-F | TTCACTGATTACCCCACAGACAATA | Real time |

| CCR7 | CCR7-RT-R | AAGCAGATGAGGGAGTAAAAGGTG | Real time |

| CCR9 | CCR9-RT-F | TCAATCCCTTCCTGTATGTGTTTGT | Real time |

| CCR9 | CCR9-RT-R | GTCCGTGTCTGACATAACTGAGGAG | Real time |

| EF-1α | EF1-RT-F | GATCCAGAAGGAGGTCACCA | Real time |

| EF-1α | EF1-RT-F | TTACGTTCGACCTTCCATCC | Real time |

2.2. Sequence analysis

Homology searching was performed using the Basic Local Alignment Tool program (http://www.blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). The TMHMM program v. 2.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/) was used to predict the protein structure. Multiple sequence alignments were carried out using the Clustal W program. The phylogenetic tree was created using the neighbor joining (NJ) method using the MEGA5 program and was bootstrapped 1000 times using the Jukes and Cantor model (Jukes, 1969).

A previous sequence (Accession number AJ003159.1) had been identified as rainbow trout CCR7 (Daniels et al., 1999), however posterior analysis in which the human CCR9 was included revealed a closer homology to CCR9 as verified in our study. This sequence is now identified in the GenBank as rainbow trout CCR9.

2.3. Fish

Healthy rainbow trout (O. mykiss) were obtained from Centro de Acuicultura El Molino (Madrid, Spain). Fish were maintained at the Centro de Investigaciones en Sanidad Animal (CISA-INIA) laboratory at 14 °C with a re-circulating water system, 12:12 h light:dark photoperiod and fed daily with a commercial diet (Skretting, Spain). Prior any experimental procedure, fish were acclimatized to laboratory conditions for 2 weeks and during this period no signs of infection or mortalities were ever observed. The experiments described comply with the Guidelines of the European Union Council (86/609/EU) for the use of laboratory animals.

2.4. Isolation of tissues and leukocytes

To evaluate the levels of constitutive CCR7 transcription in different tissues, four unhandled rainbow trout were sacrificed by overexposure to MS-222 and gills, gut, skin, head kidney (HK), spleen, thymus, liver, gonad and brain removed for RNA extraction. All these samples from naïve animals used to estimate constitutive levels of CCR7 transcription were pooled in groups of 2–4 fish; however, at least 3 independent pools were always analyzed.

In other naïve fish, different leukocyte populations were obtained. For this, blood was collected from the caudal vein using a heparinized syringe and immediately diluted in cold medium Mixed Isove's DMEM/Ham's F12 (Gibco) at a ratio of 1:1. Head kidney and spleen were aseptically removed and homogenized with an Elvehjem homogenizer to prepare single cell suspension. Single cells suspensions prepared in previous steps were layered onto an isotonic Percoll gradient (Biochrom AG) (r = 1.075 g ml−1) and centrifuged at 650g for 40 min. Cells at the interphase were collected, washed with PBS, resuspended in corresponding volume of medium to the final concentration of 4 × 106 cells ml−1 and kept on ice until further preparation.

Hindgut leukocytes were obtained following the protocol described in Zhang et al. (2010). Briefly, hindgut was opened lengthwise, washed in PBS and cut in small pieces. The cell extraction procedure started with three rounds of 30 min agitation at 4 °C in L-15 medium supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum (FCS, Gibco), 100 IU ml−1 penicillin and 100 lg ml−1 streptomycin (Gibco), followed by an agitation in PBS with 1 mM EDTA and 1 mM DTT for 30 min. Finally, the tissues were digested with 0.15 mg ml−1 of collagenase (Sigma) in L-15 for 2 h at 20 °C. All leukocyte fractions were collected and pooled, washed in L-15 medium, and separated onto 63/40% discontinuous Percoll gradient for 30 min at 400g. Cells at the interface were collected and washed twice with L-15, and resuspended in L-15 with 5% FCS at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells ml−1.

2.5. Enrichment of the cells by magnetic cell sorting

Leukocytes isolated by density gradient centrifugation as described above were magnetically sorted according to instructions of manufacturer. Briefly, leukocytes were incubated for 30 min on ice with selected anti-trout IgM (1.14) (DeLuca et al., 1983), anti-trout myeloid cells (Köllner et al., 2001) or anti-trout T cells (D30) mAbs. Following washing step, cells were resuspended in 160 μl of sorting buffer (PBS with 0.5% BSA and 2 mM EDTA) plus 40 μl of goat-anti-mouse- IgG microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Germany) for 30 min. Finally, the magnetically labeled leukocytes were resuspended in 2 ml of sorting buffer and applied to columns attached to the magnetic separator (MiniMACS, Miltenyi Biotec, Germany). Unlabeled leucocytes flowing through the column were discarded. After washing of the column with appropriate amount of buffer, column was detached from magnetic separator and labeled cells were flushed out using 1 ml of buffer. Quality of the separation was assessed by the flow cytometry and only fractions exceeding 95% purity were used for preparation of RNA.

2.6. Rainbow trout infection with VHSV

For all in vivo infections with VHSV, the 0771 strain was used and propagated in the RTG-2 rainbow trout cell line as previously described (Montero et al., 2011). All virus stocks were titrated in 96-well plates according to Reed and Muench (1938).

Rainbow trout were divided in two groups of 20 trout each. Groups were injected intraperitoneally with either 100 μl of culture medium (mock-infected control) or 100 μl of a viral solution containing 1 × 106 TCID50 (tissue culture infective dose per ml). At days 1, 3, 7 and 10 post-injection, five trout from each group were sacrificed by overexposure to MS-222, and head kidney and spleen removed for RNA extraction. The experiment was repeated once to confirm the results.

In a further experiment, rainbow trout were challenged with VHSV through bath infection to determine if CCR7 played a role in the mobilization of cells to the fin bases, the main entry site and a primary replication area (Montero et al., 2011) or the gills. For this, 12 rainbow trout of approximately 4–6 cm were transferred to 2 L of a viral solution containing 5 × 105 TCID50 ml−1. After 1 h of viral adsorption with strong aeration at 14 °C, the fish were transferred to their water tanks. A mock-infected group treated in the same way was included as a control. At days 1, 3 and 6 post-infection, five trout from each group were sacrificed by overexposure to MS-222. The area surrounding the base of the dorsal fins as well as the gills were removed for RNA extraction from four fish in each group.

2.7. In vitro stimulation of hindgut and hindgut leukocytes

In order to establish if CCR7 transcription was regulated in the hindgut or hindgut leukocytes upon immune stimulation, hindgut segments of approximately 1 cm of length were removed from 3 naïve fish and placed in 24 well plates with 1 ml of Leibovitz medium (L-15, Invitrogen) supplemented with 100 IU ml–1 penicillin, 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin and 5% FCS alone or supplemented with Poly I:C (10 mg ml−1) or Escherichia coli inactivated for 5 min at 100 °C (1 × 104 bacteria ml−1). Hindgut cells isolated as described before and adjusted to 1 × 106 cells ml−1 were stimulated and incubated in the same conditions. After 24 h of incubation at 18 °C, RNA was extracted and the levels of CCR7 transcription determined.

2.8. C. shasta trout infection

Rainbow trout were infected with the metazoan parasite C. shasta and after 3 months of infection, gut lymphocytes were extracted as previously described (Zhang et al., 2010). It has been previously shown that fish surviving to 3 months after initiation of the infection had obvious signs of inflammation in the gut mucosa, as shown by extensive infiltration of B lymphocytes (Zhang et al., 2010). Both IgM+ and IgT+ B cells were isolated from the gut segments of both infected and non-infected controls and sorted as described before (Zhang et al., 2010).

2.9. cDNA preparation

Total RNA was extracted from trout tissues or isolated leukocyte populations using Trizol (Invitrogen) following the manufactureŕs instructions. Tissues were first homogenized in 1 ml of Trizol in an ice bath, while cells were directly resuspended in Trizol. The RNA pellets were washed with 75% ethanol, dissolved in diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water and stored at −80 °C.

RNAs were treated with DNAse I to remove any genomic DNA traces that might interfere with the PCR reactions. One microgram of RNA was used to obtain cDNA in each sample using the Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions. The resulting cDNA was diluted in a 1:10 proportion with water and stored at −20 °C.

2.10. Evaluation of CCR7 gene expression by real time PCR

To evaluate the levels of transcription of CCR7, real-time PCR was performed with an Mx3005P™ QPCR instrument (Stratagene) using SYBR Green PCR Core Reagents (Applied Biosystems). Reaction mixtures containing 10 μl of 2× SYBR Green supermix, 5 μl of primers (0.6 mM each) and 5 μl of cDNA template were incubated for 10 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 amplification cycles (30 s at 95 °C and 1 min at 60 °C) and a dissociation cycle (30 s at 95 °C, 1 min 60 °C and 30 s at 95 °C). For each mRNA, gene expression was corrected by the elongation factor 1α (EF-1α) expression in each sample and expressed as 2−ΔCt, where ΔCt is determined by subtracting the EF-1α Ct value from the target Ct as previously described (Cuesta and Tafalla, 2009). The primers used were designed from the CCR7 sequence using the Oligo Perfect software tool (Invitrogen) and are shown in Table 1. All amplifications were performed in duplicate to confirm the results. Negative controls with no template were always included in the reactions.

2.11. Statistics

Data handling, analyses and graphic representation was performed using Microsoft Office Excel 2010. Statistic differences were determined using a Mann–Whitney U test or a one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05).

3. Results

3.1. Identification of rainbow trout CCR7

Using the previously described zebrafish CCR7, public EST databases were searched and two overlapping EST sequences that correlated with different fragments of a CCR7-like sequence were identified (Accession numbers CX721232 and CU065128). Assembly of these two sequences gave a nucleotide sequence which encoded a 326 aa protein which closely resembled CCR7. Posterior phylogenetic analysis through neighbor joining trees with different teleost and vertebrate CCR7 sequences confirmed this identification. Once the complete sequence had been obtained through 3′RACE, it was used in a BLAST search of the GenBank database which revealed that it was highly similar to known teleost and other vertebrate CCR7 sequences. The sequence similarity of this novel sequence and known CCR7 sequences from teleosts and other vertebrates can be observed in the alignment shown in Fig. 1. Conserved features needed for CCR7 function such as seven transmembrane domains (predicted using TMHMM) (Krogh et al., 2001), the DRY sequence in internal loop 2, which interacts with the G-protein signaling partner (Scheer et al., 1996), cysteines required for disulfide bond formation and regulation (Ai and Liao, 2002), conserved aspartic acids and tyrosines in the N-terminus which interact with the ligand and serines and threonines in the internal C terminus which can be phosphorylated for regulating receptor function are also present in this sequence. Interestingly, while four of five residues, identified by Ott et al. (2004) as important for CCR7 receptor activation, were conserved, the fifth asparagine at position 305 of the human CCR7 sequence is not conserved in either the teleost or duck sequences (although it was conserved in the trout CCR9 sequence). The teleost CCR7 sequences do have a conserved asparagine three amino acids before this location which may serve the same function, however.

Fig. 1.

Alignment of rainbow trout CCR7 with known teleost, mouse, human and duck CCR7 sequences and the known trout CCR9 sequence. Transmembrane sequences of the proteins are indicated in yellow. Cysteines needed for disulfide bonds and regulation are indicated in blue while conserved tyrosines and aspartic acid residues required for ligand binding are indicated in grey. The DRY sequence plus conserved serines and threonines that are required for regulation and G protein binding are indicated in purple as are putative glycosylation sequences in the amino terminus of the tilapia, zebrafish human and duck sequences. Residues required for activation of the receptor identified by Ott et al. (2004), are indicated in green (red for the probable alternate in the teleost sequences). The published sequences used were: O. mykiss chemokine receptor (ccr9), mRNA Accession number: NM_001124610.1 (as an outgroup), Oreochromis niloticus C–C chemokine receptor type 7-like (LOC100692019), mRNA Accession number: XM_003454632.1, D. rerio chemokine (C–C motif) receptor 7 (ccr7), mRNA Accession number: NM_001098743.1, Anas platyrhynchos CC chemokine receptor 7 gene Accession number: EU418503.1, Mus musculus chemokine (C–C motif) receptor 7 (Ccr7), mRNA Accession number: NM_007719.2, Homo sapiens chemokine (C–C motif) receptor 7 (CCR7), mRNA Accession number: NM_001838.3. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

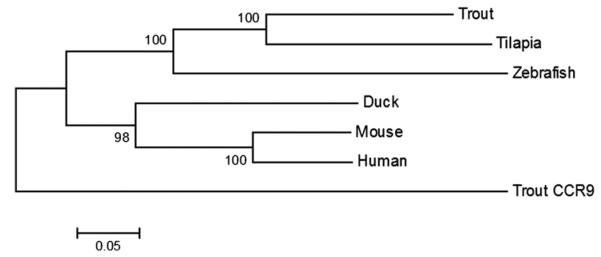

Further phylogenetic analysis of the rainbow trout CCR7 with the other known teleost CCR7 sequences (Fig. 2), as well as sequences of several human CCRs showed that rainbow trout CCR7 clustered with other CCR7 sequences, clearly distinct from the rainbow trout sequence previously identified as CCR7 (and designated CCR9).

Fig. 2.

Evolutionary relationships of trout CCR7 with other known teleost, human, mouse and duck CCR7 sequences inferred using the neighbor-joining method (Saitou and Nei, 1987). The numbers shown next to the branches represent support for the cluster in a bootstrap test (1000 replicates) (Felsenstein, 1985). The evolutionary distances were computed using the Jukes–Cantor method (Jukes, 1969). All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA5 (Tamura et al., 2011). The published sequences used were the same as in Fig. 1.

3.2. Distribution of CCR7 expression in naïve rainbow trout tissues and isolated leukocyte populations

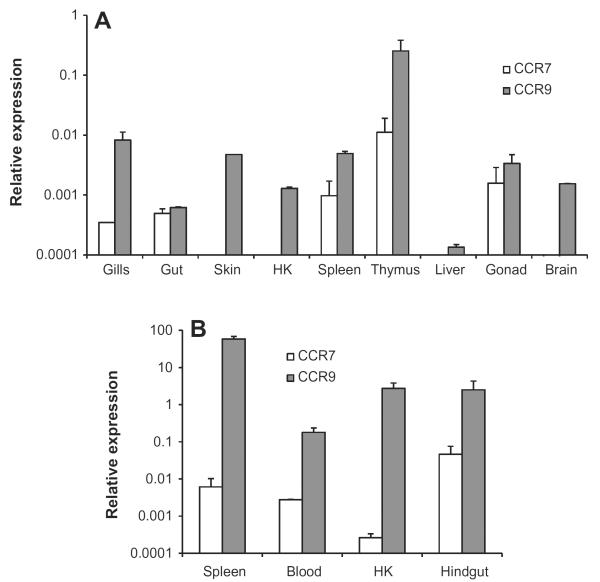

A very specific expression pattern was observed for the trout CCR7 gene in tissues obtained from naïve fish as it was only detected in gills, hindgut, spleen, thymus and gonad (Fig. 3A). No transcription was detected in the skin, head kidney, liver or the brain. On the other hand, the former CCR7, now designated as CCR9, was expressed in all tissues studied at relative levels higher than those of CCR7. When leukocyte populations were isolated with Percoll, CCR7 transcription was detected in blood, spleen, head kidney and hindgut leukocytes, at relative levels lower than those detected for CCR9 (Fig. 3B). The fact that head kidney leukocytes but not head kidney as a whole transcribed CCR7 may be due to activation of the cells through the isolation process, since an increase in the levels of CCR7 transcription after Percoll isolation was also observed in hindgut and spleen leukocytes.

Fig. 3.

Constitutive levels of transcription of CCR7 and CCR9 in different tissues or leukocyte populations. The amount of CCR7 or CCR9 mRNA in a pooled sample from 2 to 4 naïve individuals was estimated through real time PCR in duplicate. Chemokine receptor transcription was evaluated in gills, gut, skin, head kidney (HK), spleen, thymus, liver, gonad and brain (A) or in complete leukocyte populations isolated form blood, spleen, head kidney (HK) or hindgut (B). Data are shown as the mean gene expression relative to the expression of endogenous control EF-1α ± SD.

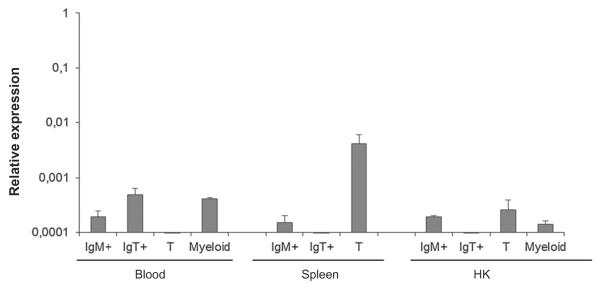

In blood, spleen and head kidney, we sorted the most numerous cell types and further analyzed CCR7 transcription (Fig. 4). In blood, IgM+ and IgT+ lymphocytes and myeloid cells showed detectable levels of CCR7 transcription, which were not observed in blood T lymphocytes. In the spleen, however, T lymphocytes showed the higher levels of CCR7 transcription followed by IgM+ cells. In this case, no CCR7 mRNA was detected in IgT+ cells. Finally in head kidney, CCR7 transcription was detected in IgM+ cells, T cells and myeloid cells but not in IgT+ cells.

Fig. 4.

Constitutive levels of transcription of CCR7 in sorted leukocyte populations. Chemokine receptor transcription was evaluated through real time PCR in the main sorted leukocyte populations from blood, spleen and HK using specific monoclonal antibodies. Data are shown as the mean gene expression relative to the expression of endogenous control EF-1α ± SD.

3.3. CCR7 transcription in response to VHSV infection

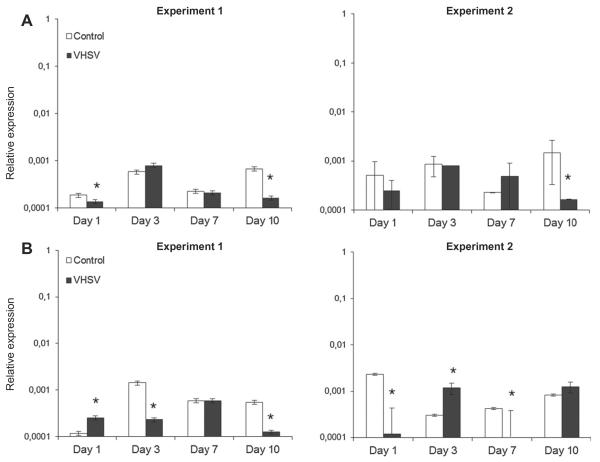

In order to determine if CCR7 plays a role in lymphocyte trafficking during the course of a systemic viral infection such as VHSV, we first studied CCR7 transcription in the spleen and head kidney after infecting rainbow trout intraperitoneally with the virus. In the spleen, VHSV induced a significant down-regulation of CCR7 transcripts at both days 1 and 10 post-infection (Fig. 5A). When the experiment was repeated this down-regulation of CCR7 transcription in response to the virus was only significant at day 10 post-infection. In the head kidney, a significant increase of CCR7 transcription was detected at day 1 post-infection in response to the virus, however, as in the spleen, VHSV reduced CCR7 transcription at both days 3 and 7 post-infection. In this case, when the experiment was repeated, similar results were observed, with significant down-regulations at days 1 and 7 post-infection, and a significant increase in response to the virus at day 3 post-infection.

Fig. 5.

Levels of transcription of CCR7 in the spleen (A) or head kidney (B) of rainbow trout infected intraperitoneally with VHSV or mock-infected with 100 μl of culture medium. At days 1, 3, 7 and 10 post-injection five trout from each group were sacrificed, RNA pooled and the levels of expression of CCR7 studied through real-time PCR in duplicate in two individual experiments. Data are shown as the mean chemokine gene expression relative to the expression of endogenous control EF1-α ± SD. *Relative expression significantly different than the relative expression in respective control (p < 0.05).

It has been established that the fin bases constitute the main entry site for fish rhabdoviruses such as VHSV (Harmache et al., 2006). Once the virus is internalized the dermis layer of the skin constitutes one of the primary replication sites within this area (Montero et al., 2011). Although CCR7 had not been detected constitutively in the skin, we also studied whether VHSV exposure could induce a mobilization of leukocytes to this area that could be mediated by this receptor. However, throughout the complete experiment CCR7 remained undetected in the fin base area, thus suggesting that this molecule is not implicated in lymphocyte homing to the skin.

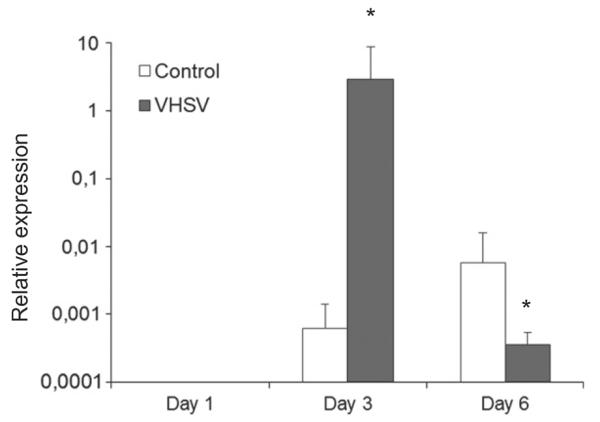

Although the gills do not constitute a major entry site for VHSV with only low (Brudeseth et al., 2002) or undetectable (Montero et al., 2011) levels of virus replication, a bath challenge with VHSV is able to trigger an effective immune response in this tissue with a strong up-regulation of many different chemokine genes at days 1 and 3 post-infection (Montero et al., 2011). In this context, we have seen that the levels of transcription of CCR7 are strongly up-regulated in response to the virus at day 3 post-infection (Fig. 6), when the levels of induction of chemokine genes are known to be high. After 6 days of infection, the levels of CCR7 mRNA in the gills significantly decrease in comparison to the levels observed at that point in mock-infected fish. No visible changes in leukocyte infiltration levels were detected through histology throughout the sampling periods (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Transcription of CCR7 in gills obtained from VHSV infected fish in comparison to mock-infected individuals. After 1, 3 or 6 days after a bath challenge with VHSV, the levels of transcription of CCR7 were assayed in five fish per group by real-time PCR. Data are shown as the mean chemokine gene expression relative to the expression of endogenous control EF1-α. *Relative expression significantly different than the relative expression in respective control (p < 0.05).

3.4. Transcription of CCR7 in the hind gut in response to immune stimuli

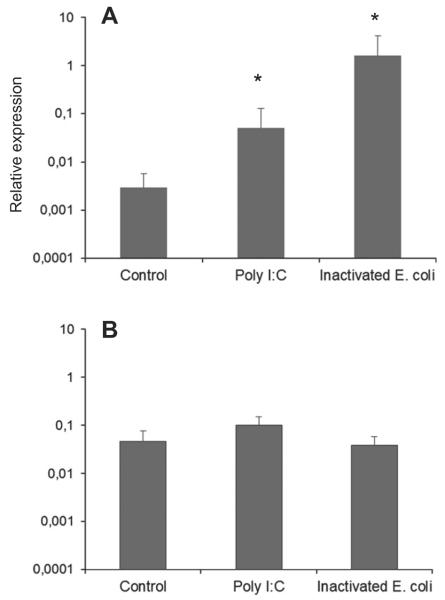

After having determined that CCR7 transcription was detected in hindgut and hindgut isolated leukocytes, we studied the levels of CCR7 transcription in hindgut segments or isolated hindgut leukocytes stimulated in vitro with Poly I:C or inactivated E. coli (Fig. 7). In the hindgut segments, both Poly I:C and inactivated bacteria were capable of up-regulating the levels of transcription of this chemokine receptor. When hindgut leukocytes were isolated, however, the levels of CCR7 transcription remained unaffected in response to the immune stimuli.

Fig. 7.

Levels of CCR7 transcription in hindgut segments (A) or isolated hindgut cells (B) stimulated in vitro with LPS or Poly I:C. Hindgut segments or 1 × 106 isolated hindgut leukocytes from different trout were treated in vitro with either Poly I:C (10 μg ml−1) or inactivated E. coli (1 × 104 bacteria ml−1). After 24 h of incubation at 18 °C, RNA was extracted and the levels of CCR7 transcription determined. Data are shown as the mean chemokine gene expression relative to the expression of endogenous control EF-1α ± SD of three independent cultures.

3.5. Transcription of CCR7 in response to C. shasta infection

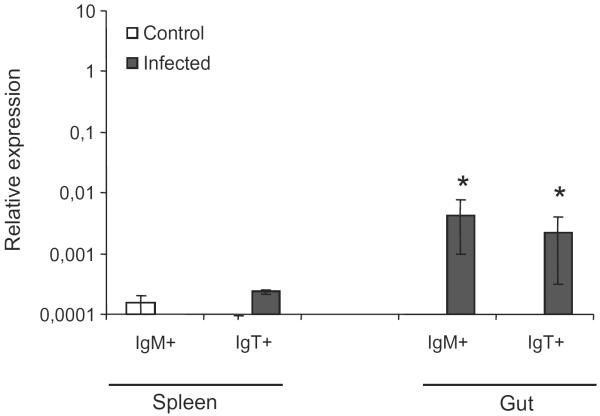

Infection of rainbow trout with C. shasta, a parasite with strong tropism for the gut, significantly up-regulated the levels of transcription of CCR7 in both sorted IgM+ and IgT+ cells in this area (Fig. 8). In the spleen of infected fish, a small increase was observed in CCR7 levels in IgT+ cells, however, IgM+ cells did not show a significant change in CCR7 transcription in response to the parasite infection. These levels of CCR7 transcription are relative to the levels of expression of EF-1α in an approximately equal number of sorted cells in each organ, and thus provide us an estimate of number of transcripts per cell.

Fig. 8.

Levels of transcription of CCR7 in IgM+ or IgT+ cells sorted from the spleen or gut of fish infected with C. shasta or mock-infected. After 1 month of infection, leukocytes were isolated from the gut and spleen of three animals in each group and IgM+ and IgT+ cells sorted using specific antibodies. The levels of transcription of CCR7 were individually assayed in these populations in duplicate through real time PCR. Data are shown as the mean chemokine gene expression relative to the expression of endogenous control EF-1α ± SD of three independent fish. *Relative expression significantly different than the relative expression in respective control (p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

In the current study, we have identified a rainbow trout chemokine receptor sequence, which is a homologue to mammalian CCR7. It has been difficult to establish true homologies between identified teleost CC chemokines and mammalian chemokines, but it seems that the degree of sequence conservation is much higher for CC chemokine receptors that have been identified to date, since their homology with mammalian counterparts are higher (Liu et al., 2009). Although a previous rainbow trout chemokine receptor sequence had been reported as CCR7, it was discovered before the human CCR9 had been identified (Daniels et al., 1999). A more recent analysis including all mammalian chemokine receptors has demonstrated that this sequence is in fact a CCR9 homologue, and as such it is now so designated in the Genbank database. Our phylogenetic studies with the new chemokine receptor as well as the former sequence confirm the ascription of this new gene as the true rainbow trout CCR7 orthologue.

The expression pattern of this rainbow trout CCR7 also resembles that of mammalian CCR7, which is strongly expressed in thymus, intestine and lymph nodes and at low levels in spleen, kidney, lung and stomach (Yoshida et al., 1997), in contrast to that of CCR9 which is strongly transcribed in all tissues and leukocyte populations studied. In mammals, CCR7 is expressed at high levels in T cells and at lower levels in B cells (Yoshida et al., 1997). Surprisingly, in our experiments a very high level of CCR7 transcription was detected in spleen T cells, whereas it was detected in head kidney T cells at levels equivalent to IgM+ cells and remained undetected in blood T cells. These differences among the levels of CCR7 detected in T cell populations from different organs should imply differences in immune role and trafficking for different trout T cell subpopulations not yet clear, but previously suggested (Takizawa et al., 2011). In blood, CCR7 transcription was also detected in IgT+ cells, a fish specific B cell population specialized in mucosal immunity (Zhang et al., 2010), for which recirculation patterns and chemokine receptor expression cannot be inferred from mammalian homologues.

In mammals, CCR7 is also expressed in mammalian mature DCs. While CCR6 is expressed primarily on immature DCs in the periphery, upon pathogen encounter, these DCs mature and migrate to secondary lymphoid organs in response to CCL19 and CCL21 where they present pathogen antigen to T cells to initiate specific adaptive immune responses (Sallusto et al., 1998; Sanchez-Sanchez et al., 2006). In most teleost species, the presence of professional antigen presenting cells has not been clearly established. Some markers for DCs such as CD83 (Ohta et al., 2004) or CD80/86 (Zhang et al., 2009) in rainbow trout have been identified, and very recently a cell population resembling DCs has been characterized in this species adapting mammalian protocols (Bassity and Clark, 2012). This CD83+ DC-like population was shown to present antigen in a more efficient way than IgM+ lymphocytes, however whether they represent an exclusive professional antigen presenting cells independent of other antigen presenting cells such as B cells remains questionable, especially since IgM+ cells have been shown to express significantly higher levels of CD80/86 than other leukocyte subtypes (Zhang et al., 2009).

Once we had established the distribution of CCR7 in tissues and leukocyte subtypes in normal conditions, we then studied how this receptor was regulated in the context of in vivo infections. When VHSV was injected intraperitoneally, CCR7 transcription significantly decreased in both spleen and head kidney, although in this last organ at very early times post-infection, an increase in CCR7 was detected. These results may indicate that upon viral infection through the peritoneum lymphoid cells are mobilized from these organs, since we have seen a significant mobilization of CD4+, IgM+, IgT+ and CD83+ cells to the peritoneum (data not shown), similar to that observed in response to other (Martinez-Alonso et al., 2012). It seems therefore feasible that CCR7 could be involved in this viral-induced mobilization of spleen and head kidney cells to primary sites of viral encounter. In concordance to this hypothesis, lymph nodes from CCR7−/− mice are devoid of naïve T cells whereas the T cell populations from spleen (red pulp), blood or bone marrow are greatly expanded (Forster et al., 1999). Furthermore, LPS injection in chicken decreased the splenic CCR7 mRNA content by approximately 100 times (Annamalai and Selvaraj, 2011). Although it has been established that, upon TCR activation, CCR7 is up-regulated in T cells to promote the recirculation of recently activated T cells to encounter activated B cells, experiments performed with LCMV, revealed that although CCR7 is up-regulated in cytotoxic CD8+ T cell populations upon virus exposure, in vivo infection with this virus provokes a marked down-regulation of CCR7 (Sallusto et al., 1999). It has been hypothesized that once activated in lymphoid organs, effector CD8 T cells are armed with hazardous molecules (e.g. perforin, CD95L) and the main function of these cells is to destroy virus-infected target cells or tumor cells in the periphery. Antigen-bearing DCs in lymphoid organs are also potential targets for the effector cells, therefore, exclusion of effector CD8 T cells from the white pulp of spleen may protect professional antigen presenting cells from cytotoxic T cell attack (Potsch et al., 1999).

When the VHSV infection was performed in trout through bath exposure, we observed an up-regulation of CCR7 in the gills suggesting a CCR7-mediated recruitment of immune cells, but not in the fin bases, despite the fact that this is the main site of virus entry into the host (Harmache et al., 2006). Once the virus is internalized through the fin bases, the dermis layer of the skin constitutes one of the primary replication sites within this area (Montero et al., 2011), and although the chemokine response in this area seems to be limited in response to the virus (Montero et al., 2011), all evidence points to the fact that CCR7 is not implicated in recruiting lymphocytes to the skin. In bovine, γgδ T cells in the skin are shown to recirculate from the blood through the skin back into the afferent and efferent lymph within in a CCR7-independent fashion (Vrieling et al., 2012).

Excluding the skin, CCR7 does seem to play a role in the mobilization of leukocytes to peripheral mucosal tissues such as the gills (in response to VHSV) or the hindgut. The implication of CCR7 in lymphocyte mobilization to the gut is foreseen in the up-regulation of CCR7 transcription upon immune stimulation ex vivo, although the reason for the lack of CCR7 regulation when isolated hindgut leukocytes are used instead of gut segments is unknown, but might be a consequence of the complicated protocol of leukocyte isolation needed for hindgut leukocytes. The implication of CCR7 in hindgut leukocyte recruitment has also been demonstrated in a natural context through the strong increase in CCR7 transcription detected in sorted B cells that have been mobilized to the gut in response to C. shasta infection. In mammals, although B cell homing to secondary lymphoid tissues has shown to be less CCR7 dependent than T cell homing (Forster et al., 2008), B cells from CCR7−/− mice do not migrate to the lymph node upon antigenic challenge and B cells are mobilized to the lymph node B-zone-T-zone boundary upon exposure to antigen in a CCR7-dependent manner (Okada et al., 2005). In our model, whether other CCRs are playing a role in the recruitment remains to be investigated.

In conclusion, we have identified a CCR7 homologue in rainbow trout that is strongly transcribed in spleen T cells and moderately transcribed in IgM+ cells and IgT+ cells from blood. Infection with VHSV induced a down-regulation of CCR7 transcription in spleen and head kidney and an up-regulation of CCR7 transcription in the gills. CCR7 also seems to be strongly involved in the recruitment of B lymphocytes to the gut, since B cells mobilized to the gut in response to C. shasta showed a strong up-regulation of CCR7 mRNA levels. Finally, all evidence point to a lack of CCR7 involvement in skin lymphocyte homing.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Starting Grant 2011 (Project No. 280469) from the European Research Council and the AGL2011-29676 project from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (Plan National AGL2011-29676). This work was also supported by a US National Science Foundation grant (NSF-MCB-0719599 to J.O.S.) and a US National Institutes of Health grant (R01GM085207-01 to J.O.S.).

References

- Ai LS, Liao F. Mutating the four extracellular cysteines in the chemokine receptor CCR6 reveals their differing roles in receptor trafficking, ligand binding, and signaling. Biochemistry. 2002;41(26):8332–8341. doi: 10.1021/bi025855y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alejo A, Tafalla C. Chemokines in teleost fish species. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2011;35(12):1215–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annamalai T, Selvaraj RK. Chemokine receptor CCR7 and CXCR5 mRNA in chickens following inflammation or vaccination. Poult. Sci. 2011;90(8):1695–1700. doi: 10.3382/ps.2011-01377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao B, Peatman E, Peng X, Baoprasertkul P, Wang G, Liu Z. Characterization of 23 CC chemokine genes and analysis of their expression in channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2006;30(9):783–796. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassity E, Clark TG. Functional Identification of dendritic cells in the teleost model, rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brudeseth BE, Castric J, Evensen O. Studies on pathogenesis following single and double infection with viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus and infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Vet. Pathol. 2002;39(2):180–189. doi: 10.1354/vp.39-2-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuesta A, Tafalla C. Transcription of immune genes upon challenge with viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus (VHSV) in DNA vaccinated rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Vaccine. 2009;27(2):280–289. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels GD, Zou J, Charlemagne J, Partula S, Cunningham C, Secombes CJ. Cloning of two chemokine receptor homologs (CXC-R4 and CC-R7) in rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1999;65(5):684–690. doi: 10.1002/jlb.65.5.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca D, Wilson M, Warr GW. Lymphocyte heterogeneity in the trout, Salmo gairdneri, defined with monoclonal antibodies to IgM. Eur. J. Immunol. 1983;13(7):546–551. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830130706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries ME, Kelvin AA, Xu L, Ran L, Robinson J, Kelvin DJ. Defining the origins and evolution of the chemokine/chemokine receptor system. J. Immunol. 2006;176(1):401–415. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster R, Davalos-Misslitz AC, Rot A. CCR7 and its ligands: balancing immunity and tolerance. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8(5):362–371. doi: 10.1038/nri2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster R, Schubel A, Breitfeld D, Kremmer E, Renner-Muller I, Wolf E, Lipp M. CCR7 coordinates the primary immune response by establishing functional microenvironments in secondary lymphoid organs. Cell. 1999;99(1):23–33. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gretz JE, Norbury CC, Anderson AO, Proudfoot AE, Shaw S. Lymph-borne chemokines and other low molecular weight molecules reach high endothelial venules via specialized conduits while a functional barrier limits access to the lymphocyte microenvironments in lymph node cortex. J. Exp. Med. 2000;192(10):1425–1440. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.10.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmache A, LeBerre M, Droineau S, Giovannini M, Bremont M. Bioluminescence imaging of live infected salmonids reveals that the fin bases are the major portal of entry for Novirhabdovirus. J. Virol. 2006;80(7):3655–3659. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.7.3655-3659.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horuk R. Molecular properties of the chemokine receptor family. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1994;15(5):159–165. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(94)90077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang IY, Park C, Kehrl JH. Impaired trafficking of Gnai2± and Gnai2−/− T lymphocytes: implications for T cell movement within lymph nodes. J. Immunol. 2007;179(1):439–448. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jukes TH. Recent advances in studies of evolutionary relationships between proteins and nucleic acids. Space Life Sci. 1969;1(4):469–490. doi: 10.1007/BF00924238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köllner B, Blohm U, Kotterba G, Fischer U. A monoclonal antibody recognising a surface marker on rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) monocytes. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2001;11(2):127–142. doi: 10.1006/fsim.2000.0300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;305(3):567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laing KJ, Secombes CJ. Trout CC chemokines: comparison of their sequences and expression patterns. Mol. Immunol. 2004;41(8):793–808. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Chang MX, Wu SG, Nie P. Characterization of C–C chemokine receptor subfamily in teleost fish. Mol. Immunol. 2009;46(3):498–504. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luther SA, Tang HL, Hyman PL, Farr AG, Cyster JG. Coexpression of the chemokines ELC and SLC by T zone stromal cells and deletion of the ELC gene in the plt/plt mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97(23):12694–12699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.23.12694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Alonso S, Vakharia VN, Saint-Jean SR, Perez-Prieto S, Tafalla C. Immune responses elicited in rainbow trout through the administration of infectious pancreatic necrosis virus-like particles. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2012;36(2):378–384. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero J, Garcia J, Ordas MC, Casanova I, Gonzalez A, Villena A, Coll J, Tafalla C. Specific regulation of the chemokine response to viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus at the entry site. J. Virol. 2011;85(9):4046–4056. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02519-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomiyama H, Hieshima K, Osada N, Kato-Unoki Y, Otsuka-Ono K, Takegawa S, et al. Extensive expansion and diversification of the chemokine gene family in zebrafish: identification of a novel chemokine subfamily CX. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:222. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohl L, Mohaupt M, Czeloth N, Hintzen G, Kiafard Z, Zwirner J, Blankenstein T, Henning G, Forster R. CCR7 governs skin dendritic cell migration under inflammatory and steady-state conditions. Immunity. 2004;21(2):279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta Y, Landis E, Boulay T, Phillips RB, Collet B, Secombes CJ, Flajnik MF, Hansen JD. Homologs of CD83 from elasmobranch and teleost fish. J. Immunol. 2004;173(7):4553–4560. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.7.4553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada T, Miller MJ, Parker I, Krummel MF, Neighbors M, Hartley SB, O'Garra A, Cahalan MD, Cyster JG. Antigen-engaged B cells undergo chemotaxis toward the T zone and form motile conjugates with helper T cells. PLoS Biol. 2005;3(6):e150. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada T, Ngo VN, Ekland EH, Forster R, Lipp M, Littman DR, Cyster JG. Chemokine requirements for B cell entry to lymph nodes and Peyer's patches. J. Exp. Med. 2002;196(1):65–75. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott TR, Pahuja A, Nickolls SA, Alleva DG, Struthers RS. Identification of CC chemokine receptor 7 residues important for receptor activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279(41):42383–42392. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401097200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peatman E, Liu Z. Evolution of CC chemokines in teleost fish: a case study in gene duplication and implications for immune diversity. Immunogenetics. 2007;59(8):613–623. doi: 10.1007/s00251-007-0228-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potsch C, Vohringer D, Pircher H. Distinct migration patterns of naive and effector CD8 T cells in the spleen: correlation with CCR7 receptor expression and chemokine reactivity. Eur. J. Immunol. 1999;29(11):3562–3570. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199911)29:11<3562::AID-IMMU3562>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed LJ, Muench A. A simple method of estimating 50% end points. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987;4(4):406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallusto F, Kremmer E, Palermo B, Hoy A, Ponath P, Qin S, Forster R, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A. Switch in chemokine receptor expression upon TCR stimulation reveals novel homing potential for recently activated T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 1999;29(6):2037–2045. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199906)29:06<2037::AID-IMMU2037>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallusto F, Schaerli P, Loetscher P, Schaniel C, Lenig D, Mackay CR, Qin S, Lanzavecchia A. Rapid and coordinated switch in chemokine receptor expression during dendritic cell maturation. Eur. J. Immunol. 1998;28(9):2760–2769. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199809)28:09<2760::AID-IMMU2760>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Sanchez N, Riol-Blanco L, Rodriguez-Fernandez JL. The multiple personalities of the chemokine receptor CCR7 in dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2006;176(9):5153–5159. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.9.5153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheer A, Fanelli F, Costa T, De Benedetti PG, Cotecchia S. Constitutively active mutants of the alpha 1B-adrenergic receptor: role of highly conserved polar amino acids in receptor activation. EMBO J. 1996;15:3566–3578. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takizawa F, Dijkstra JM, Kotterba P, Korytar T, Kock H, Kollner B, Jaureguiberry B, Nakanishi T, Fischer U. The expression of CD8 alpha discriminates distinct T cell subsets in teleost fish. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2011;35(7):752–763. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011;28(10):2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrieling M, Santema W, Van Rhijn I, Rutten V, Koets A. Gammadelta T cell homing to skin and migration to skin-draining lymph nodes is CCR7 independent. J. Immunol. 2012;188(2):578–584. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnock RA, Campbell JJ, Dorf ME, Matsuzawa A, McEvoy LM, Butcher EC. The role of chemokines in the microenvironmental control of T versus B cell arrest in Peyer's patch high endothelial venules. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191(1):77–88. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida R, Imai T, Hieshima K, Kusuda J, Baba M, Kitaura M, et al. Molecular cloning of a novel human CC chemokine EBI1-ligand chemokine that is a specific functional ligand for EBI1, CCR7. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272(21):13803–13809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Thorgaard GH, Ristow SS. Molecular cloning and genomic structure of an interleukin-8 receptor-like gene from homozygous clones of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2002;13(3):251–258. doi: 10.1006/fsim.2001.0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YA, Hikima J, Li J, LaPatra SE, Luo YP, Sunyer JO. Conservation of structural and functional features in a primordial CD80/86 molecule from rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), a primitive teleost fish. J. Immunol. 2009;183(1):83–96. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YA, Salinas I, Li J, Parra D, Bjork S, Xu Z, LaPatra SE, Bartholomew J, Sunyer JO. IgT, a primitive immunoglobulin class specialized in mucosal immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2010;11(9):827–835. doi: 10.1038/ni.1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]