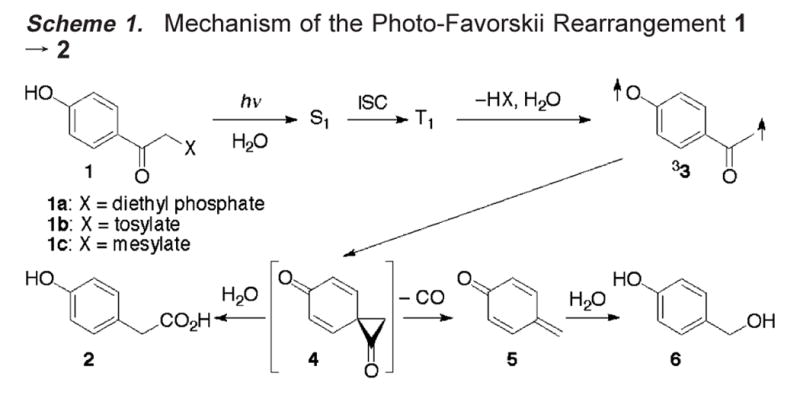

p-Hydroxyphenacyl is an effective photoremovable protecting group, not least due to the fast release of its substrates, accompanied by a photo-Favorskii rearrangement of compounds 1 to p-hydroxyphenylacetic acid (2) that is transparent down to 300 nm. First used for the release of ATP from 1 (X = ATP) a decade ago,1 the reaction has been employed in a variety of fields as diverse as neurobiology,2 enzyme catalysis,3 and biochemistry.4 The nature and timing of the bond-making and bond-breaking events have not been fully elucidated despite extensive experimental and theoretical efforts by our group5 and others.6,7 We now report observation of the primary photoproduct, the triplet biradical 33, and of a new side product, p-hydroxybenzyl alcohol (6), that is formed by decarbonylation of the putative spirodione intermediate 4 at moderate water concentrations (Scheme 1). Solvent kinetic isotope effect (SKIE) studies by nanosecond laser flash photolysis (LFP) provide significant information on the role of water in the photo-Favorskii rearrangement of p-hydroxyphenacyl diethyl phosphate 1a to p-hydroxyphenylacetic acid (2).

Anderson and Reese first reported the intriguing photoreaction 1(X = Cl) → 2 + HCl and suggested that the skeletal rearrangement may proceed via a spirodione intermediate 4,8 which has yet to be detected. Intersystem crossing (ISC) of diethyl phosphate 1a is very fast, kISC = 4 × 1011 s−1,5 and we have established that the rearrangement proceeds from the triplet state, T1.1,4b,5 This was confirmed by Phillips et al.7a-c Hydroxylic solvents play a major role in the rearrangement. The lifetime of T1 decreases from several μs in degassed, dry CH3CN to about 0.4 ns in aqueous CH3CN (50% by vol).5,7c,d

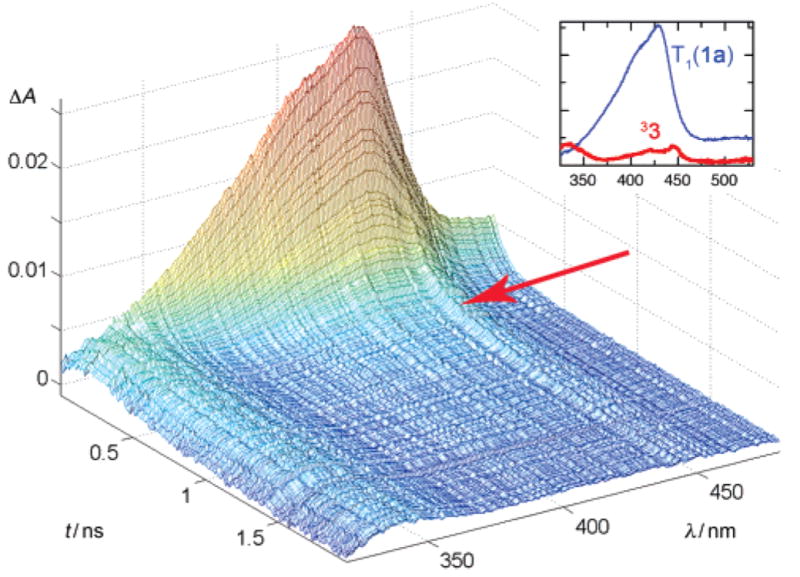

The lifetime of T1 of 1a is further reduced to 100 ± 10 ps in 87% aqueous CH3CN (Figure 1) and to 63 ± 10 ps in wholly aqueous solution. This was the key to revealing that the decay of T1 left weak absorptions at 445, 420, and 330 nm, which decayed with a somewhat longer lifetime of ca. 0.6 ns. Pump–probe spectra obtained with other derivatives of 1 with good leaving groups (1b,c: X = tosylate, mesylate) also displayed the transient species possessing the same weak, but characteristic bands and the same lifetime. Kinetic analysis of sequential reactions A → B → C is generally difficult when the rate constants of the two processes are similar, unless independent information is available regarding one of the two rate constants.9 Such information was available from recent work by Phillips and co-workers.7c Time-resolved resonance Raman spectroscopy of 1a in 50% aqueous CH3CN proved that the final product 2 appears with a rate constant of 2.1 × 109 s−1 following pulsed excitation of 1. The appearance of 2 followed a biexponential rate law, T1→M→2, i.e., the formation of 2 was slightly delayed with respect to the decay of T1, k = 3.0 × 109 s−1, which had been determined independently by optical pump–probe spectroscopy in the same solvent. A water-associated spirodione species 4·2H2O was proposed for the intermediate M, which was said to be optically transparent in the 300–700 nm range.

Figure 1.

Pump–probe spectroscopy of 1a in 87% aqueous CH3CN. The sample was excited with a pulse from a Ti/Sa–NOPA laser system (266 nm, 150 fs pulse width, pulse energy 1 μJ).10 The inset shows the species spectra of T1 and 33 that were determined by global analysis of the spectra taken with delays of 10–1800 ps using a biexponential fit.

Our observations are consistent with those of Phillips et al.,7c except that we have now detected weak absorption by the intermediate M, which we assign to the triplet biradical 33.11 The position and shape of its absorption bands are similar to those of the phenoxy radical, which are also weak.12 MP2 calculations (6-31G*, PCM acetonitrile, Supporting Information) predict that the biradical 33 is twisted by 27° around the Car–CO bond, but there are two low-frequency modes involving this twist. Thus, reliable predictions for the geometry and, hence, the absorption spectrum of 33 are difficult. If the twist of the Car–CO bond in fact is closer to 90°, then the absorption spectrum of 33 should be nearly identical to that of the phenoxy radical. TDFT as well as open-shell PPP SCF CI calculations13 predict that 33 (twisted by 27°) and the phenoxy radical should have rather similar absorption spectra. We could not locate a stationary point for the singlet biradical 13. Both planar and vertical initial trial structures for 13 converged to the spirodione 4, suggesting that cyclization to 4 immediately follows ISC of 33 (Figure 2).

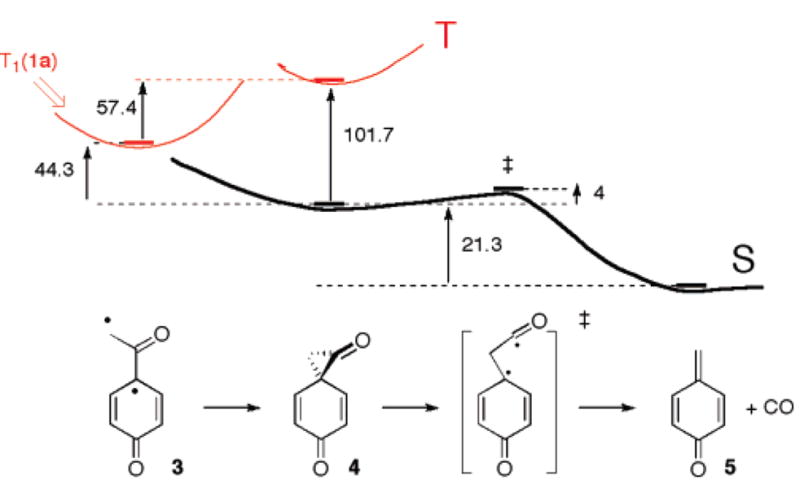

Figure 2.

Ab initio calculations (MP2/6-31G*, PCM: acetonitrile). Solid lines (–) indicate stationary points. Energy differences are in kcal mol−1.

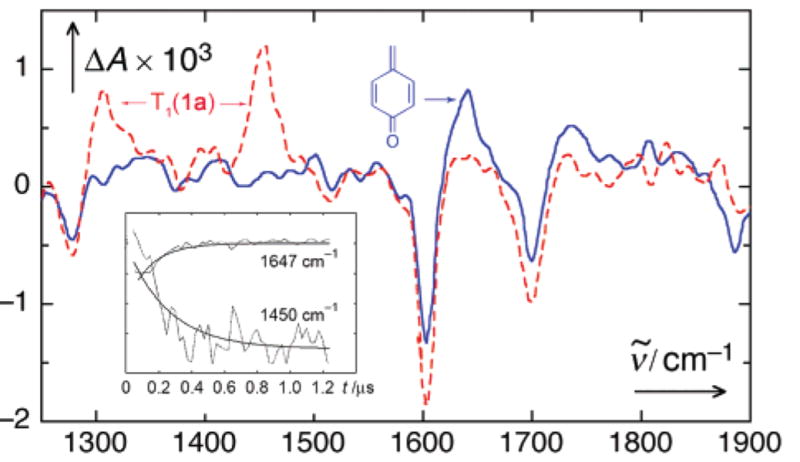

Our attempts to detect the elusive spirodione 4 by step–scan FTIR failed, and, with the wisdom of hindsight, this is no surprise. The C=O stretch vibration of cyclopropanone lies at 1813 cm−1,14 and DFT calculations (Supporting Information) predict 1880 cm−1 for 4. No transient signal was discovered in that region upon excitation (266 nm with 4-ns, 5-mJ pulses from a Nd/YAG laser) of 1a in mixtures of D2O (2–20% by vol) and CD3CN. However, transient bands at 1450 and 1300 cm−1 appeared within the 50-ns rise time of our setup. Their first-order decay was accompanied by the rise of another band at 1647 cm−1, k = (8.5 ± 1.0) × 106 s−1 in 2% D2O (Figure 3). The rate increased, while the amplitude of this band decreased with higher amounts of water. The prominent bands of the first intermediate are similar to those of triplet acetophenone15 and are assigned to the triplet state T1.

Figure 3.

FTIR difference spectra at 50 ns (red, dotted) and 1 μs delay (blue, solid line) of 1a in acetonitrile with 2% D2O. The spectra were reconstructed after factor analysis of 50 spectra using two factors.

The same intermediates were detected by nanosecond laser flash photolysis of 1a in wet CH3CN. The first-order decay of the triplet–triplet absorption by T1, λmax = 395 nm, left a broad absorption, λmax = 276 nm, which was sufficiently long-lived to be monitored on a conventional spectrophotometer. Its decay was accelerated by water, k ≈ 0.01 s−1 in 5% and 0.05 s−1 in 10% H2O, and particularly by acid. The initial amount of the 276-nm transient decreased with increasing water content. p-Hydroxybenzyl alcohol (6) was discovered to be a byproduct of the photoreaction in wet CH3CN, and its relative yield also decreased with increasing water content.16 These observations suggested that the 276-nm transient is p-quinone methide (5). Weak metastable NMR signals were detected shortly after irradiation of 1a in a mixture of D2O (2.5% by vol) and CD3-CN at −25 °C, also indicating the formation of 5 (Supporting Information).

Definitive identification of p-quinone methide (5) was possible by comparison with recent work of Kresge and co-workers, who reported rate constants for the hydrolysis of 5 that was generated by flash photolysis of p-hydroxybenzyl acetate in wholly aqueous solution, kunc = 3.3 s−1 and kH+ = 5.3 × 104 M−1 s−1.17 Using the same method to generate authentic 5 in wet CH3CN we obtained satisfactory agreement for the rate of hydrolysis of 5 formed from the two precursors. Taken together, these observations strongly support the assignment of the second transient (1647 cm−1, λmax = 276 nm)18 to p-quinone methide (5), which is formed by decarbonylation of 4, eq 1, at moderate water content. Ab initio calculations (Figure 2) indeed show that decarbonylation of 4 to p-quinone methide (5) is a very facile process with an activation energy of only 4 kcal mol−1.

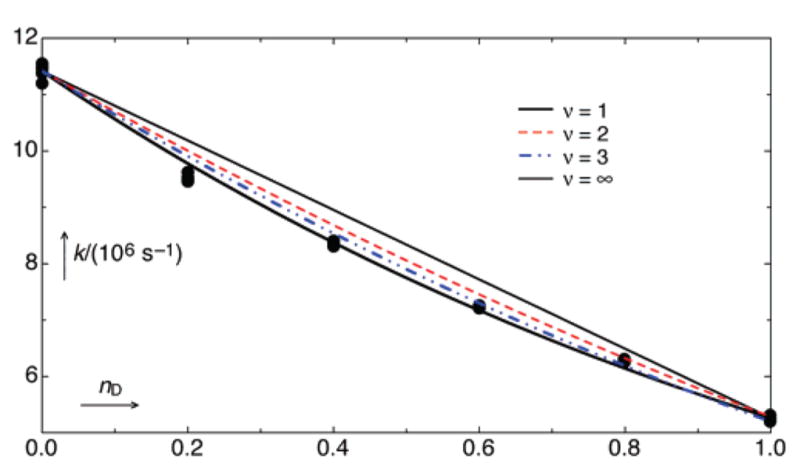

To characterize the role of water on the primary photoreaction and, in particular, the number of water molecules involved in the transition state for the release of HX, we studied the SKIE on the decay rate constants of T1(1a) by LFP. Degassed 10% aqueous CH3-CN was chosen as a solvent, because accurate lifetimes of T1(1a) could be obtained under these conditions with D/H mole fractions n = nD/(nD + nH) varying from 0 to 1. The resulting rate constants kn are given in Table 1 and are plotted in Figure 4.

Table 1. Rate Constants for the Decay of T1 (kobs) as a Function of the D/H Mole Fraction n Obtained by LFP Excitation at 248 nm and Monitored at 395 nm at 25 °C in 10% Aqueous CH3CN.

| n | kobs/(106 s−1) | average | kH/kn |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | 11.2, 11.5, 11.5, 11.4, 11.6 | 11.4 ± 0.14 | 1.00 |

| 0.20 | 9.46, 9.62, 9.54, 9.50 | 9.53 ± 0.07 | 1.20 ± 0.02 |

| 0.40 | 8.33, 8.38, 8.31, 8.41 | 8.36 ± 0.04 | 1.36 ± 0.02 |

| 0.60 | 7.26, 7.21, 7.21, 7.26 | 7.24 ± 0.03 | 1.57 ± 0.02 |

| 0.80 | 6.31, 6.30, 6.31, 6.25 | 6.29 ± 0.03 | 1.81 ± 0.02 |

| 1.00 | 5.20, 5.31, 5.25 | 5.25 ± 0.06 | 2.17 ± 0.03 |

Figure 4.

Decay rate constants kn of T1(1a) in degassed 10% (by vol) aqueous CH3CN at 25 ± 0.1 °C at various atom fractions of deuterium n in the aqueous part of the solvent. The upper solid line shows the expectation (eq 2, ν = 1) for a single-site isotope effect of 2.17, and the lower solid line shows the expectation (eq 3) for a generalized solvation effect from many sites. The intermediate dashed lines correspond to a two-site effect (red, isotope effect of 1.5 at each site; eq 2, ν = 2) and a three-site effect (blue, isotope effect of 1.3 at each site; eq 2, ν = 3).

The proton inventory method19 has rarely been applied to excited-state processes.20 It has proven to be a powerful method to determine the number of protons being transferred in the rate-determining step for ground-state reactions. Our total SKIE is large, kH/kD = 2.17 ± 0.03, and the proton inventory plot is clearly curved, indicating that the transition state involves at least two weakly bonded protons “in flight”. The relationship between the kn – n ata pairs is commonly analyzed by the Kresge–Gross–Butler (KGB) relation, eq 1,21,22 where the parameters φi‡ = (D/H)i/(D/H)L2O are the isotopic fractionation factors for the exchangeable positions i = 1 ·· v in the transition complex.

| (1) |

It is here assumed that isotopic fractionation in the reactant state is negligible. Then the fractionation factor for the ith transition-state site, φi‡, becomes equal to the reciprocal isotope effect (kH/kD)−1 generated at that site. It is significantly less than 1 only for protons being transferred in the transition state or bonded to a positively charged oxygen as in H3O+. Equation 2 then reduces to some simplified limiting cases: (a) a single site generates the entire isotope effect of 2.17, as in a single proton-transfer reaction (eq 2, v = 1 and kH/kD = 2.17); (b) two sites generate roughly equal effects as in a double proton-transfer reaction (eq 2, v = 2; kH/kD = 2.171/2 = 1.47); (c) three sites generate roughly equal effects as in general-base catalysis by water19c (eq 2, v = 3; kH/kD = 2.171/3 = 1.30); (d) a large number v of sites generate the effect as in a large change in solvation, so that each effect is small and thus the dependence of kn on n becomes exponential, eq 3.

| (2) |

| (3) |

The comparison of the data with these models in Figure 4 appears to exclude the one-proton model and to require at least two protons to generate the observed isotope effect. It is worth noting that the decay rate constants of T1(1a) in CH3CN depend in a quadratic fashion on water concentration, kobs = k0 + kw[H2O]2.5

The acidity of the phenolic proton of 1a increases by ∼104 upon excitation to the triplet state, whereas the carbonyl group becomes much more basic.5 The observed isotope effects show that H-bonding or H-transfer phenomena involving at least two protic sites accompany the expulsion of phosphate from T1(1a). Reasonable mechanisms that include such interactions include general base catalysis by water (removal of a proton from p-OH) in concert with general acid catalysis (proton transfer from the solvent to the phosphate leaving group and/or the excited carbonyl) or a water-molecule chain carrying a proton from the acidic p-OH site to the leaving phosphate group. Phillips7 and Wan6 have suggested such mechanisms, and Phillips has shown that protonation of the leaving phosphate is important.7e A sequential reaction, deprotonation of p-OH followed by general acid catalysis on phosphate expulsion from the anion, can be excluded, because the elimination reaction is faster than the deprotonation of T1(1a).5,7

In conclusion, the sequence of intermediates occurring in the photo-Favorskii rearrangement of p-hydroxyphenacyl derivatives 1 in aqueous solutions is now established (Scheme 1). The proton inventory data indicate that diethyl phosphate release from T1(1a) proceeds in concert with deprotonation and requires the assistance of at least two water molecules.7c The primary biradical 33 has hitherto escaped detection by optical spectroscopy, because its absorption is so weak and its lifetime is similar to or, at low water concentrations, shorter than that of its strongly absorbing precursor, T1(1). The formation of 33 from T1(1) amounts to release of the substrates HX; the lifetimes of T1(1) thus define the release rate. Formation of p-hydroxybenzyl alcohol (6) has not been previously reported. It is a signature of the elusive spirodione 4, the lifetime of which must be shorter than its rate of formation under the reaction conditions. Nevertheless, the spirodione 4 must be a real intermediate, because it is trapped at high water concentrations, yielding p-hydroxyphenylacetic acid (2).

Supplementary Material

Scheme 1.

Mechanism of the Photo-Favorskii Rearrangement 1 → 2

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (J.W.) and by NIH grants P50 GM069663 and R01 GM72910 (R.S.G.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Step-scan FTIR spectra, NMR of 5, and details of the calculations. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Park CH, Givens RS. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:2453–2463. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sul JY, Orosz G, Givens RS, Haydon PG. Neuron Glia Biol. 2004;1:3–10. doi: 10.1017/s1740925x04000031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zou K, Cheley S, Givens RS, Bayley H. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:8220–8229. doi: 10.1021/ja020405e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zou K, Miller TW, Givens RS, Bayley H. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2001;40:3049–3051. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010817)40:16<3049::AID-ANIE3049>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Geibel S, Barth A, Amslinger S, Jung AH, Burzik C, Clarke RJ, Givens R, Fendler K. Biophys J. 2000;79:1346–1357. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76387-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Arabaci G, Gou XC, Beebe KD, Coggeshall KM, Pei D. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:5085–5086. [Google Scholar]; Du X, Frei H, Kim SH. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8492–8500. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Givens RS, Goeldner M, editors. Dynamic Studies in Biology. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2005. [Google Scholar]; (b) Givens RS, Weber JFW, Jung AH, Park CH. Methods Enzymol. 1998;291:1–29. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(98)91004-7. Caged Compounds. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conrad PG, Givens RS, Hellrung B, Rajesh CS, Ramseier M, Wirz J. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:9346–9347. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang K, Corrie JET, Munasinghe VRN, Wan P. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:5625–5632. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Ma C, Zuo P, Kwok WM, Chan WS, Kan JTZ, Toy PH, Phillips DL. J Org Chem. 2004;69:6641–6657. doi: 10.1021/jo049331a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ma C, Kwok WM, Chan WS, Zuo P, Kan JTW, Toy PH, Phillips DL. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1463–1427. doi: 10.1021/ja0458524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ma C, Kwok WM, Chan WS, Du Y, Kan JTW, Phillips DL. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2558–2570. doi: 10.1021/ja0532032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Chan WS, Kwok WM, Phillips DL. J Phys Chem A. 2005;109:3454–3469. doi: 10.1021/jp044546+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Zuo P, Ma C, Kwok WM, Chan W, Phillips DL. J Org Chem. 2005;70:8675. doi: 10.1021/jo050761q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Chen XB, Ma C, Kwok WM, Guan X, Du Y, Phillips DL. J Phys Chem A. 2006;110:12406–12413. doi: 10.1021/jp064490e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson JC, Reese CB. Tetrahedron Lett. 1962;1:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonneau R, Wirz J, Zuberbühler AD. Pure Appl Chem. 1997;69:979–992. [Google Scholar]; Andraos J, Lathioor EC, Leigh WJ. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 2000;2:365–373. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Müller MA, Gaplovsky M, Wirz J, Woggon WD. Helv Chim Acta. 2006;89:2987–3001. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radicals such as a phenoxy radical formed by hydrogen abstraction or a phenacyl radical formed by Norrish type I cleavage of 1 can be excluded because of the short lifetime of intermediate M. Compounds 1 with poor leaving groups did, however, give some long-lived transient absorption at 330 nm that may be attributed to the formation of phenacyl radicals.

- 12.Radziszewski JG, Gil M, Gorski A, Spanget-Larsen J, Waluk J, Mroz BJ. J Chem Phys. 2001;115:9733–9738. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gisin M, Wirz J. Helv Chim Acta. 1983;66:1556–1568. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turro NJ, Hammond WB. J Am Chem Soc. 1966;88:3672–3673. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Srivastava S, Young E, Toscano JP. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:6173–6174. [Google Scholar]

- 16.The molar ratio of products 2:6 was 0.44 in 5% D2O and decreased to 0.14 in 60% D2O as determined by H-NMR.

- 17.Chiang Y, Kresge AJ, Zhu Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:6349–6356. doi: 10.1021/ja020020w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lasne MC, Ripoll JL, Denis JM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981;37:503–508. [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Alvarez FJ, Schowen RL. Buncel E, Lee CC, editors. Isotopes in Organic Chemistry. 1987;7:1–59. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kresge AJ, More O'Ferrall RA, Powell MF. Buncel E, Lee CC, editors. Isotopes in Organic Chemistry. 1987;7:177–273. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hegazi M, Mata-Segreda JF, Schowen RL. J Org Chem. 1980;45:307–310. [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Chen Y, Gai F, Petrich JW. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:10158–66. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gai F, Rich RL, Chen Y, Petrich JW. 568 Structure and Reactivity in Aqueous Solution. ACS Symp Ser. 1994:182–95. [Google Scholar]; (c) Janz JM, Farrens DL. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:55886–55894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408766200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kuehne H, Brudvig GW. J Phys Chem B. 2002;106:8189–8196. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang TK, Chiang Y, Guo HX, Kresge AJ, Mathew L, Powell MF, Wells JA. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:8802–8807. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quinn DM. Kohen A, Limbach HH, editors. Taylor and Francis. Isotope Effects in Chemistry and Biology. 2006:995–1018. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.