Abstract

We assessed the effect of DBT skills utilization on features of borderline personality disorder as measured by the Personality Assessment Inventory-Borderline Features Scale (PAI-BOR). Participants were outpatients (N = 27) enrolled in a dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) program in a university-affiliated community mental health clinic. Diary cards were collected each week to track self-reported skills use. At the beginning of each new skills training module, patients completed another PAI-BOR. Univariate and multilevel analyses indicated significant improvement on the total PAI-BOR score and on several PAI-BOR subscale scores. Results also revealed that overall DBT skills use increased significantly over time, as did individual skills related to mindfulness, interpersonal effectiveness, emotion regulation, and distress tolerance. Multilevel modeling results indicated that overall skills use showed a significant effect on PAI-BOR total scores, Affective Instability scores, Identity Problems scores, and Negative Relationships scores, even after controlling for initial levels of distress and diary card compliance.

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) is a branch of cognitive-behavioral therapy that was designed to treat women who meet criteria for borderline personality disorder (BPD) and engage in self-injurious behavior (Linehan, 1993a). There are four standard DBT outpatient components: individual therapy, skills group, telephone coaching, and therapist consultation team. Randomized clinical trials have found significant reductions in self-injurious behaviors and anger expression, and improvement in treatment retention and social adjustment for women who have received one-year of DBT compared to those in control conditions (Linehan, Armstrong, Suarez, Allmon, & Heard, 1991; Linehan, Heard, & Armstrong, 1993; Linehan, Tutek, Heard, & Armstrong, 1994; Verheul et al., 2003) and when compared to treatment by experts (Linehan et al., 2006). The maintenance of these effects has been demonstrated 1-year post-treatment (Linehan et al., 1993; Linehan et al., 2006). DBT has also been effectively modified to treat other populations, such as women with binge eating disorder, women with comorbid substance dependence and BPD, and depressed older adults (see Koerner & Dimeff, 2000; Koerner & Linehan, 2000; Robins & Chapman, 2004, for reviews).

Authors speculate that DBT is effective because several unique treatment strategies cause a reduction in ineffective behaviors when the patient is emotionally dysregulated (Lynch, Chapman, Rosenthal, Kuo, & Linehan, 2006; Linehan, Bohus, & Lynch, 2007). However, it is unclear which ingredients are “active” and account for patient improvement. Identifying these components highlight those aspects that require more or less emphasis in respect to gaining effective treatment outcomes (Linehan, 2000).

One unique aspect of DBT is the inclusion of a skills group that targets ineffective behavioral patterns that are specific for the BPD patient. There are four skills modules that have overarching goals to reduce core symptoms of BPD: (1) core mindfulness skills aim to reduce confusion about the self, (2) interpersonal effectiveness skills aim to decrease interpersonal chaos, (3) emotion regulation skills aim to decrease mood lability, and (4) distress tolerance skills aim to decrease impulsive behaviors (Linehan, 1993b). This group encourages behavioral rehearsal between sessions by reviewing homework and monitoring skills use, thus, promoting skills generalization. Lynch et al. (2006) posited that the focus in DBT on generalizing skills to patient’s natural environment might account for some of the positive treatment outcomes.

Researchers have investigated the effectiveness of DBT skills group paired with non-DBT individual therapy (cited in Linehan, 1993a; Harley, Baity, Blais, & Jacobo, 2007). During the initial randomized control clinical trial for DBT, Linehan (1993a) assigned patients who were already receiving individual therapy in the community to either a DBT skills group or an assessment-only condition. Results showed that augmenting individual therapy in the community with DBT skills group did not improve treatment outcomes, suggesting that skills group alone cannot account for treatment gains. However, Harley and colleagues (2007) recently found that a modified DBT skills program significantly reduced BPD symptoms and depression scores post-treatment. In this naturalistic study, 45 patients received individual therapy in conjunction with a modified DBT skills group. Therapists were predominately non-DBT oriented (n = 39; 79.6%). Harley et al. (2007) concluded that these preliminary results demonstrate the feasibility and effectiveness of providing DBT in more real-world settings. However, neither of these two studies tested what effect the skills themselves have on symptom reduction when embedded in the larger treatment program. Additionally, only treatment completers were included in their outcome analyses.

Several studies have examined DBT skills when embedded in the larger DBT treatment program (Miller, Wyman, Huppert, Glassman, & Rathus, 2000; Lindenboim, Comtois, & Linehan, 2007). Miller et al. (2000) examined whether the perceived helpfulness of specific skills were related to changes in the behavioral patterns they are intended to treat in an adolescent DBT program (n = 33 consecutive treatment-completers). These researchers found that participants experienced a significant reduction in confusion about the self, impulsivity, emotional instability, and interpersonal problems at the end of the 12-week treatment program. Participants rated all the DBT skills in the moderate to extremely helpful range. However, interestingly, none of the skills’ helpfulness ratings were correlated with a reduction in the corresponding problem area. There were some associations between helpfulness ratings of the skills and noncorresponding problem areas. Specifically, there was a positive relation between helpfulness of emotion-regulation skills and changes in confusion about the self, and helpfulness of one distress tolerance skill and changes in interpersonal problems. Additionally, there was a negative association between helpfulness of a mindfulness skill and change in the emotional instability problem area.

To evaluate homework compliance, Lindenboim et al. (2007) investigated skills utilization over the course of treatment for women aged 18–45 who were enrolled in a randomized controlled clinical trial for DBT. These researchers found that these suicidal patients with BPD reported practicing skills frequently (63% or 78% of days, depended on scoring method used). They also found that several distress tolerance and mindfulness skills were practiced most frequently and that self-reported skills use increased over the course of the treatment year.

THE CURRENT STUDY

The main aim of this study is to investigate the impact of DBT skills use on borderline features over the course of treatment when embedded in the larger treatment program. Although the nonrandomized and uncontrolled nature of this study prevents drawing any causal conclusions, the results from this study may identify a possible “active ingredient” of DBT treatment that can account for reductions in BPD symptoms. This study employs a multi-level repeated measures design that utilizes data from all participants that were ever enrolled in the treatment program. Therefore, the results from this naturalistic design are likely to be highly relevant to community treatment centers.

We have three specific aims. First, we will examine whether or not BPD features as measured by Personality Assessment Inventory-Borderline Features Scale (PAI-BOR; Morey, 1991) decrease over the course of treatment. This extends previous work examining the utility of this PAI-BOR as an intake assessment for BPD in DBT treatment seekers (Jacobo, Blais, Baity, & Harley, 2007). Second, we investigate whether or not skills utilization increases over the course of treatment to replicate the findings of Linenboim and colleagues (2007). Third, we test whether or not skills utilization predicts decreases in PAI-BOR scores over time. The PAI-BOR includes four subscales that measure BPD symptoms: affective instability, identity problems, negative relationships, and self-harm (a broader measure of impulsivity, but not suicidality). These four problem areas are also targeted in DBT skills group. Specifically, affective instability is addressed with emotion regulation skills, identity problems are targeted with mindfulness skills, negative relationships are addressed with interpersonal effectiveness skills, and impulsive behaviors are targeted with distress tolerance skills. In addition to testing overall skills use on symptom reduction, we will test the impact that each of these skills sets have on the corresponding PAI-BOR symptom area.

METHOD

SAMPLING PROCEDURE

Participants were outpatients enrolled in a university-affiliated community mental health clinic DBT program (N = 27). The age range of the sample was 16–61 years (M = 30.4). The participants were almost exclusively Caucasian (n = 24; 96%) and the majority were women (n = 23; 85%). At intake, the number of current Axis I disorders diagnosed in this sample ranged from 0 to 4 with a mean of 1.41 (SD = 0.93). Twelve (44%) met diagnostic criteria for a current Depressive Disorder (DD) only; three (11%) met criteria for a current Bipolar Disorder only; two (7%) met criteria for an Adjustment Disorder only; and one (4%) participant met criteria for an Eating Disorder (ED) only. Six (22%) participants had a least two current Axis I diagnoses. The most common Axis I comorbidity included four (15%) participants with both DD and an Anxiety disorder. In addition, two (7%) participants had comorbid DD with an ED and one (4%) participant had comorbid DD with substance use diagnoses. Three (11%) participants had no recorded Axis I diagnoses at intake. Psychiatric medications were available to patients as an ancillary treatment through the DBT program. Most of the participants in this study (89%) were taking at least one pychotropic medication. All of these participants were taking an anti-depressant, and the mean number of different classes of medication was 2.14.

Patients were targeted for inclusion in the treatment program if they were interested in receiving DBT services, and they produced clinically significant elevations on at least one subscale of the PAI-BOR. The PAI-BOR is a 24-item self-report measure that assesses features associated with BPD (total score α = .86). Four subscales of the PAI-BOR target affective instability (α = .80), identity problems (α = .63), negative relationships (α = .56), and self-harm (impulsivity, but not suicidality; α = .80), respectively. The PAI-BOR has demonstrated reliability and validity in previous studies (e.g., Morey, 1991; Trull, 1995). Total scores >37 on the PAI-BOR (two standard deviations above the mean score for community participants) suggest the presence of clinically significant borderline features (Morey, 1991; Trull, 1995; Trull, Useda, Conforti, & Doan, 1997). Eighteen (67%) of our participants had significant affective instability subscale scores at baseline (score >11); 12 (44%) had significant identity problems subscale scores (score >11); 14 (52%) had significant negative relationships sub-scale scores (score >11); and 11 (41%) had significant self-harm subscale scores (score >8). The baseline mean total score on the PAI-BOR for our sample was 43.3 (SD = 11.2). The majority of participants scored above the PAI-BOR score threshold for BPD features (total score >37; n = 19, 70%).

After being identified for inclusion in the program, participants were administered the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Borderline Personality Disorder Section (SIDP-IV-BPD; Pfohl, Blum, & Zimmerman, 1997) as part of the intake process. The SIDP-IV is a semi-structured interview that assesses criteria of Axis II personality disorders. Previous research has demonstrated the concurrent, short-term, and long-term reliability of this measure (see Zimmerman, 1994). For this study, we used the SIDP-IV Borderline Section to determine the number of BPD criteria that each participant endorsed. In this study, each patient’s responses to the BPD SIDP-IV items were discussed in the clinical consultation team to arrive at a consensus score for each BPD criterion. Sixty-three percent (17/27) of study participants met criteria for a diagnosis of BPD (they endorsed at least five of the nine DSM-IV criteria on the SIDP-IV). The prevalence for each of the BPD criteria was: affective instability (93%), suicidal behavior (70%), anger (67%), chronic feelings of emptiness (67%), interpersonal problems (56%), impulsivity (52%), identity disturbance (48%), transient dissociation in response to stress (41%), and frantic efforts to avoid abandonment (37%). Of the 19 participants with elevated total PAI-BOR scores, 74% also met SIDP-IV criteria for BPD.

During the initial intake process, patients also completed the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis & Spencer, 1993) to measure general distress (α = .97). The Global Severity Index (GSI) score ranged from 0.81–2.66 (M = 1.97, 80+ percentile rank) in this sample.

ASSESSMENT PROCEDURE

This treatment program provided the four standard DBT components: (1) individual therapy, (2) weekly skills group lead by two DBT therapists, (3) telephone coaching with the primary therapist, and (4) consultation team for the therapists. The skills group covered each of the four DBT skills modules twice per 12-month cycle. The teaching sequence for the skills modules occurred in the following order: Mindfulness, Interpersonal Effectiveness, Emotion Regulation, and Distress Tolerance. At the beginning of each new skills module, patients were asked to complete the PAI-BOR scale. The number of completed PAI-BORs ranged from one to eight (M = 4.1, SD = 2.30). Treatment providers included five advanced clinical psychology doctoral students and one clinical psychologist, all who had been trained to conduct DBT. All doctoral student therapists received one hour of additional supervision by a clinical psychologist beyond the weekly consultation team.

Skills utilization was assessed by diary cards that therapists collected weekly. For every day of the week, patients circled whether or not they had practiced each DBT skill (22 skills were listed). The average number of skills utilized per week was calculated for the total time each participant was in treatment and for the average number of skills completed per week between each PAI-BOR assessment. The number of diary cards completed ranged from 2 to 108 (M = 36.85, SD = 31.64). All data were included in the analyses regardless of the length of time patients were enrolled in treatment or the outcome of treatment (treatment length ranged from 2 to 118 weeks, M = 49.0, SD = 39.6). However, for multilevel analyses examining trends over time, only data from the first 52 weeks of treatment are used. A measure of diary card compliance was calculated by dividing the number of completed diary cards by the number of weeks in therapy (M = .80, SD = .21).

ANALYSES

Change in borderline features, as measured by the PAI-BOR, and skills use, as indicated on the weekly diary cards, were analyzed using multilevel regressions. Multilevel modeling allows an overall trend across individuals to be estimated from repeated measurements within individuals over time. In addition to controlling for nested assessments within individuals, the multilevel framework does not require that all individuals are assessed an equal number of times or at the same intervals. Estimates at each time interval are made from all available data and the number of assessments is taken into account when determining the influence of that particular time interval on the trend as a whole. Time in our models was coded as the number of weeks since the initial PAI-BOR assessment, or treatment enrollment. Multilevel analyses were conducted using SAS PROC MIXED (Singer, 1998).

Multilevel modeling also allows for estimates to have random variation among individuals. For example, although the model estimates an average intercept for the group of individuals, individuals may significantly vary around that estimate. In addition, if there are two or more random effects, covariance can also be modeled. For example, a model in which there is significant random variation between individuals on the intercept and slope, may also have a significant random covariance between intercept and slope. The significance of these random variance and covariance estimates can be tested by comparing −2 log likelihood values for the models with and without the specific parameter. All random effects were tested using this method in our analyses and only those that were significant were retained in the final models.

RESULTS

BORDERLINE SYMPTOM REDUCTION

Results from t-tests, contrasting PAI-BOR scores at study entry and at the end of treatment, indicated significant improvement in total PAI-BOR scores, MΔ = 5.3, SD = 9.9, t(26) = 2.8, p = .011, Identity Problems sub-scale scores, MΔ = 1.1, SD = 2.8, t(26) = 3.6, p = .001, and Self-Harm sub-scale scores, MΔ = 1.1, SD = 2.6, t(26) = 2.2, p = .038, but only marginally significant improvement in Affective Instability subscale scores, MΔ = 1.1, SD = 3.0, t(26) = 1.9, p = .076. Gender was a significant covariate of change in Negative Relationships subscale scores. When gender was included in the model, results also indicated significant improvement in Negative Relationships subscale score from pre- to post-treatment, F(1, 25) = 15.266, p = .001).

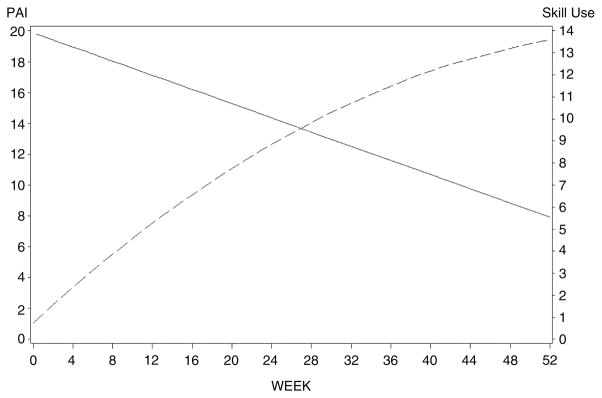

Multilevel modeling conducted on PAI-BOR total and subscale scores over time indicated a linear decrease (β = −0.230, p = .013) in overall borderline features during the first year of treatment (Figure 1). In addition to total PAI-BOR scores, Affective Instability subscale scores, and Negative Relationships subscales scores showed a significant negative (decreasing) linear trend over time. The results for Identity Disturbance and Self Harm subscale scores indicated a negative, but not significant, linear trend. Therefore, these analyses indicated that BPD features did decrease over time, although the rate was statistically significant for only the PAI-BOR Total, Affective Instability, and Negative Relationship scores. All results held after controlling for client age, initial distress at the time of enrollment (BSI GSI score), number of BPD criteria met at intake (as assessed by the borderline section of the SIDP-IV), and treatment compliance (as measured by the percent of weeks that diary cards were completed by each individual over the course of treatment). Table 1 presents the results for the full model for each PAI-BOR score.

FIGURE 1.

Plot of linear trends indicating increase in overall DBT Skills Use over 52 weeks (dotted line) and decrease in PAI-BOR Total scores over 52 weeks (solid line). Both trend lines are corrected for covariates (age, initial BSI-GSI score), number of DSM-IV-TR BPD criteria at intake, and diary card compliance.

TABLE 1.

Standardized Coefficients from the Multilevel Model of Change in PAI-BOR Total and Subscale Scores Across the First Year of Treatment

| Outcome

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAI-BOR Total Score | Affective Instability Subscale | Identity Problems Subscale | Negative Relationships Subscale | Self Harm Subscale | |

| Fixed Effects | |||||

| Intercept | 19.871* | 3.052 | 7.342** | 8.796** | 2.951 |

| Linear Trend | −0.230* | −0.056* | −0.030 | −0.058* | −0.030 |

| Age | 0.041 | 0.068 | −0.040 | 0.043 | −0.024 |

| BSI GSI | 8.110** | 1.978† | 1.391* | 1.268† | 2.795* |

| BPD Symptoms | 1.384† | 0.542 | 0.271 | 0.088 | 0.272 |

| Compliance | 4.446 | 3.857 | 1.392 | 0.432 | 1.024 |

| Random Effects | |||||

| Intercept | 50.117** | 10.894 | 2.195* | 4.918** | 13.470** |

| Linear Trend | 0.086† | 0.004 | — | 0.008† | 0.005† |

| Covariance | — | — | — | −0.104 | −0.007 |

| Residual | 19.793*** | 2.658*** | 4.398*** | 2.253*** | 2.495*** |

Note. Parameters that were not estimated in the full, best fitting model for each outcome are indicated by dashes (—).

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

SKILLS UTILIZATION

According to the reports from the weekly diary cards completed by the participants, mindfulness skills were most frequently utilized by our sample (44% of total skills used), followed by Distress Tolerance (29%), Emotion Regulation (18%), and Interpersonal Effectiveness (9%) skills, respectively. On average, participants reported using 7.1 (SD = 3.5) skills per week (range = 0.3 to 13.2).

Multilevel modeling of the use of skills over time suggests that overall skill use increased (Linear trend, β = 0.415, p < .0001; Quadratic trend, β = −0.003, p = .028) over the first year of treatment (Figure 1). Specifically, overall skills use as well as Mindfulness (linear), Interpersonal (linear), Emotion Regulation (quadratic), and Distress Tolerance (linear) skills use showed a significant positive trend over time.1 Therefore, overall skills use as well as individual skills use all increased significantly over time. These results held after controlling for client age, initial distress at the time of enrollment (BSI GSI score), number of BPD criteria met at time of intake (as assessed by the borderline section of the SIDP-IV), and treatment compliance (as measured by the percent of weeks that diary cards were completed by each individual over the course of treatment). Table 2 presents the results for the full model for each skill set.

TABLE 2.

Standardized Coefficients from the Multilevel Model of Change in Skill Utilization Across the First Year of Treatment

| Outcome

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Skill Use | Mindfulness Skill Use | Interpersonal Skill Use | Emotion Regulation Skill Use | Distress Tolerance Skill Use | |

| Fixed Effects | |||||

| Intercept | 0.7482 | −0.2541 | 0.2792 | 0.2338 | −0.8937 |

| Linear Trend | 0.4145*** | 0.2239*** | 0.0422*** | 0.0033 | 0.0920*** |

| Quadratic Trend | −0.0032* | −0.0035*** | −0.0004* | 0.0040* | — |

| Cubic Trend | — | — | — | −0.0001* | — |

| Age | 0.0125 | 0.0055 | 0.0009 | 0.0035 | 0.0147 |

| BSI GSI | −0.4176 | 0.0060 | −0.0631 | −0.1352 | 0.0978 |

| BPD Symptoms | −0.0950 | −0.0344 | −0.0150 | −0.0186 | −0.0408 |

| Compliance | 1.3483 | 1.2981 | −0.0984 | 0.1130 | 1.0346 |

| Random Effects | |||||

| Intercept | 3.2634* | 2.6333** | 0.0433 | — | 0.0735 |

| Linear Trend | 0.0373* | — | 0.0009† | 0.0025* | 0.0059* |

| Covariance | — | — | 0.0078* | — | — |

| Residual | 4.3564*** | 2.0825*** | 0.1091*** | 0.2417*** | 0.8111*** |

Note. Parameters that were not estimated in the full, best fitting model for each outcome are indicated by dashes (—).

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

THE EFFECT OF SKILL UTILIZATION ON BORDERLINE SYMPTOM REDUCTION

Multilevel models examining the effect of skill utilization on borderline features indicate that overall skill use was associated with a significant reduction (β = −0.480, p < .001) in total borderline features endorsed over time. Overall skill use was also associated with significant reductions in Affective Instability (β = −0.146, p = .005), Identity Disturbance (β = −0.175, p < .001), and Negative Relationships (β = −0.086, p = .039) sub-scale scores. The effect of overall skills use on Self Harm subscale scores was also negative (i.e., more skills use was associated with lower Self Harm scores), but not significant. As indicated, these results held while controlling for client age, initial distress at the time of enrollment, number of BPD criteria met at intake, and treatment compliance. Table 3 presents the results for the full model for each PAI-BOR score.2

TABLE 3.

Standardized Coefficients from the Multilevel Model Predicting Change in PAI-BOR Total and Subscale Scores from Skill Utilization Across the First Year of Treatment

| Outcome

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAI-BOR Total Score | Affective Instability Subscale | Identity Problems Subscale | Negative Relationships Subscale | Self Harm Subscale | |

| Fixed Effects | |||||

| Intercept | 24.571* | 4.129 | 7.714** | 8.477** | 4.084 |

| Skills Use | −0.480*** | −0.146** | −0.175** | −0.086* | −0.066 |

| Age | −0.004 | 0.037 | −0.037 | 0.034 | −0.039 |

| BSI GSI | 7.761** | 2.070* | 1.625* | 1.616* | 2.499* |

| BPD Symptoms | 0.441 | 0.268 | 0.158 | 0.021 | 0.016 |

| Compliance | 6.856 | 4.966 | 1.609 | −0.215 | 0.435 |

| Random Effects | |||||

| Intercept | 67.760*** | 9.809*** | 3.569*** | 5.232*** | 15.330*** |

| Residual | 31.044*** | 4.325*** | 3.634*** | 2.823*** | 3.422*** |

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

In addition to examining the effect of overall skills use on borderline features, we examined use of specific skill sets: Mindfulness, Interpersonal, Emotion Regulation, and Distress Tolerance. When all control variables (listed above) and all four skill sets were included in the model, only Mindfulness (β = −0.277, p = .044) and Emotion Regulation (β = −0.803, p = .022) skills significantly predicted a reduction in Identity Disturbance subscale scores over time. Emotional Regulation skills were marginally associated with a reduction in Negative Relationships subscale scores (β = −0.588, p = .062) and Mindfulness skills were marginally associated with a reduction in Self Harm subscale scores (β = −0.272, p = .056).

SUMMARY OF THE MAIN FINDINGS

Over the course of one year of DBT treatment, patients indicated an improvement in overall BPD features, as well as in the Affective Instability and Negative Relationships features.

Over the course of one year of DBT treatment, patients reported that they used more DBT skills as treatment progressed. Increases in skills use over time were found for the DBT skills sets Mindfulness, Interpersonal Effectiveness, Emotion Regulation, and Distress Tolerance.

Increased skills use was associated with a reduction in BPD features over the course of one year of DBT treatment. Skills use was also associated with a reduction in the following specific subscales of BPD features: Affective Instability, Negative Relationships, and Identity Disturbance.

The increased use of Mindfulness and Emotion Regulation skills predicted a significant reduction in Identity Disturbance features.

DISCUSSION

The present study examined the effect of DBT skills use on BPD features over the natural course of treatment. Linking skills utilization to symptom reduction highlights potential mechanisms of action in a standard DBT treatment program. Although the naturalistic design prohibits drawing any causal conclusions, it offers data that likely generalize to community treatment programs. To this end, we addressed three specific questions: (1) Do BPD features, as measured by the PAI-BOR, decrease over the course of treatment? (2) Does skills utilization increase over the course of treatment? (3) Does skills utilization predict reductions in PAI-BOR scores? More specifically, do skills modules predict reductions in the BPD features that the skills target? To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the impact of skills utilization on BPD symptoms in the natural course of DBT treatment.

Examination of pre-post self-report data revealed that patients enrolled in the DBT program experienced a significant reduction in BPD features as measured by the PAI-BOR. There was a significant reduction in the total score and several subscales, including Identity Problems, Self-harm (a measure of impulsivity, more broadly), and a marginally significant improvement in the Affective Instability subscale. When gender was added as a covariate, there was also a significant reduction in the Negative Relationships subscale. When examining the PAI-BOR scores using multilevel modeling, results indicated a significant linear decrease over the first year of treatment, consistent with the univariate analyses. Specifically, PAI-BOR total score, Affective Instability subscale scores, and Negative Relations subscale score significantly decreased over time. Identity Problems and Self-harm subscale scores exhibited a decreasing linear trend, although not significant. Given that the PAI-BOR measures enduring features of the disorder, this was a somewhat conservative test of BPD symptom improvement. To our knowledge this is the first study to utilize the PAI-BOR as an outcome measure for patients enrolled in a DBT treatment program, and this extends previous work demonstrating the validity of using the PAI-BOR as an intake assessment for patients with BPD (Jacobo et al. 2007; Stein, Pinsker-Aspen, & Hilsenroth, 2007).

We also found that skills utilization increased over time in treatment. This finding could be interpreted as patients strengthening their skills use and generalizing skills taught in DBT to new situations over the course of treatment and is consistent with Lindenboim et al.’s (2007) work demonstrating that participants in a randomized control trial of DBT increased their skills practice over the course of the study. Our findings demonstrate this pattern is also likely in a community treatment center. The rank order of the frequency of which our participants reported using skills was as follows: Mindfulness (44% of total skills), Distress Tolerance (29%), Emotion Regulation (18%), and Interpersonal Effectiveness (9%). Similarly, Lindenboim et al. (2007) found that Distress Tolerance and Mindfulness skills were practiced most frequently followed by Emotion Regulation skills: Interpersonal Effectiveness skills were practiced the least frequently. Miller et al. (2000) also reported that Mindfulness and Distress Tolerance skills were rated as the most helpful by adolescent patients. As for why Mindfulness and Distress Tolerance skills be practiced most frequently, Lindenboim et al. (2007) hypothesize that it could be that these skills are those that are the most frequently rehearsed in treatment. For example, when patients call their therapist for a coaching call, they are likely in distress and will be coached to use a distress tolerance skill. Mindfulness skills are also taught more frequently than the other skills in group (once after every module) as they are referred to as the “core” skills.

Lastly, we examined the impact that skills utilization had on symptoms of BPD. We found that overall skills use was associated with a significant reduction in total borderline features over the course of treatment. Overall skills use was associated with reductions in subscales of the PAI-BOR, including Affective Instability, Identity Problems, and Negative Relationships. These findings held even when controlling for age, diary card compliance, and level of distress and number of borderline symptoms at intake. We also examined the effect of specific skills sets on features of BPD. The four DBT skills modules and the four subscales of the PAI-BOR target similar constructs. We expected using skills designed to target a specific feature of BPD would be associated with a reduction in that symptom over the course of treatment. Specifically, we expected that utilization of Mindfulness skills would be associated with improvement in Identity Problems, use of Interpersonal Effectiveness would be associated with reduction in Negative Relationships, utilizing more Emotion Regulation skills would be associated with improvement in Affective Instability, and using Distress Tolerance skills would be associated with reduction in Self-harm scores. As expected, Mindfulness skills were associated with decreases in the Identity Problems scale. However, unexpected associations were found as well. Emotion Regulation skills predicted a reduction in Identity Problems scores, Emotion Regulation skills predicted a marginally significant decrease in Negative Relationships subscale scores, and Mindfulness skills were also associated with marginally significant reduction in Self-harm subscale scores.

Why might use of one skills set predict changes in a seemingly unrelated feature of BPD? First, it is possible that skills from one set are necessary to deal with problems in another area. For example, it seems reasonable that to effectively interact with people, one would be required to regulate emotions to do so. Also, with increased ability to regulate emotions (e.g., Emotion Regulation) comes more consistency in day to day interactions, providing a more stable and consistent sense of self (e.g., Identity Disturbance). These results suggest that using DBT skills in one area can have carry-over effects to other features of BPD. It is also interesting that Distress Tolerance skills were not associated with significant improvements in any BPD feature. This could be because individuals who increasingly utilize Distress Tolerance skills are in continual crisis throughout treatment. Another possibility is that reliance on Distress Tolerance skills is initially high in the beginning of treatment but that over the course of treatment, a decrease in the use of these skills is an indicator of more behavioral control and problem-solving abilities.

The findings from this study make several unique contributions. First, we tested the effect of DBT as it is likely to be administered in community outpatient clinics. We also employed a multi-level repeated measures design that utilized all data from participants that were ever enrolled in the treatment program. Therefore, results from this study may be more generalizable to community treatment centers, which may have dropouts at various time points during DBT treatment. Secondly, this study extends the research on DBT treatment outcomes to date by demonstrating a specific component, namely self-reported skills use, is associated with symptom reduction. Lastly, our results suggest that specific DBT skill sets are associated with reductions in features of BPD. Therefore, skills training and use were found to be important components of a comprehensive DBT program. However, we know from Linehan (1993a) that augmenting non-DBT individual therapy with skills group did not impact treatment outcomes. Interestingly, Harley et al. (2007) found that augmenting individual therapy, regardless of therapists’ orientation, with DBT skills group did effectively reduce symptoms of BPD. However, patients who received individual therapy out of their therapists’ system were much more likely to drop out of treatment than if they received treatment consistent with their therapists’ orientation. Additionally, only those patients who completed treatment were included in the outcome analyses. Although these findings could reflect non-DBT individual therapists who were practicing and reinforcing DBT skills in individual sessions, it is difficult to determine exactly what the therapists were doing in sessions. Taken together, these studies suggest that the reinforcement and practice of skills use in individual DBT sessions and in coaching calls may be an important part of their effectiveness. This is consistent with Lynch et al.’s (2006) hypothesis that the generalization of new behavioral skills to relevant contexts of the patient’s natural environment serves as an active treatment component. Future studies might examine the role of other treatment modalities (coaching calls and individual therapy) on skill acquisition and use.

The results of this research are not without limitations. First, findings could reflect differences in motivation to change. Highly motivated participants are probably more likely to use skills and comply with diary card monitoring. However, by controlling for diary card compliance, our findings suggest a unique effect of skills utilization beyond this individual difference. Second, due to the relatively small sample size, our power to detect smaller effects was limited. Our repeated measures design (and multilevel modeling) maximized power for a small sample size; nonetheless, null findings might be due to attenuated statistical power to detect small effects. Third, given that we measured skills use by self-report, it is unknown if the participants were actually using the skills they endorsed and if they were using them as indicated. Future studies might employ a performance-based assessment of skills use to more accurately assess skills utilization. Lastly, this study did not have a control group. Therefore, findings might not be specific to DBT skills training but could be due to any type of general skills training. The specificity of skills training is an area in need of further exploration. Future studies can compare the efficacy of DBT skills training versus a more generic skills training to test the specificity of the skills training component in the overall treatment. However, finding that mindfulness skills in particular predicted improvement in BPD features suggests some specificity for DBT skills training.

Footnotes

For both Overall Skills Use and Emotion Regulation Skills Use, the significant quadratic trend indicated that the increase in skills use leveled off as time of treatment increased. See Figure 1 displays this pattern for Overall Skills Use.

The advantage of collecting multiple measurements of both borderline features and skill use is that it allows for a more precise examination of these associations over time. In contrast, studies that simply examine pre-post change scores (and then correlate these) are limited in that the estimate of change over time is much less reliable because of fewer data points that are considered. For this reason, it is preferable to conduct multiple assessments throughout treatment in order to provide a more precise estimate of the trend of improvement (or lack thereof) over time. Further, multilevel modeling can accommodate different numbers of assessments, missing data for some participants, and can be used to examine associations between purported active ingredients in treatment and change over time.

References

- Derogatis LR, Spencer PM. The brief symptom inventory (BSI): Administration, scoring, and procedures manual. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Harley RM, Baity MR, Blais MA, Jacobo MC. Use of dialectical behavior therapy skills training for borderline personality disorder in a naturalistic setting. Psychotherapy Research. 2007;17:351–358. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobo MC, Blais MA, Baity MR, Harley R. Concurrent validity of the personality assessment inventory for borderline scales in patients seeking dialectical behavior therapy. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2007;88:74–80. doi: 10.1080/00223890709336837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koerner K, Dimeff LA. Further data on dialectical behavior therapy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2000;7:104–112. [Google Scholar]

- Koerner K, Linehan MM. Research on dialectical behavior therapy for patients with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2000;23:151–167. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70149-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenboim N, Comtois KA, Linehan MM. Skills practice in dialectical behavior therapy for suicidal women meeting criteria for borderline personality disorder. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2007;14:147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: The Guildford Press; 1993a. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Skills training manual for treating borderline personality disorder. New York: The Guildford Press; 1993b. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. The empirical basis of dialectical behavior therapy: Development of new treatments versus evaluation of existing treatments. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2000;7:113–119. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Armstrong HE, Suarez A, Allmon D, Heard HL. Congnitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;48:1060–1064. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360024003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Bohus M, Lynch TR. Dialectical behavior therapy for pervasive emotion dysregulation: Theoretical and practical underpinnings. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 581–605. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Heard HL, Armstrong HE. Naturalistic follow-up of a behavioral treatment for chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50:971–974. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820240055007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Tutek DA, Heard HL, Armstrong HE. Interpersonal outcome of cognitive behavioral treatment for chronically suicidal borderline patients. Americal Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:1771–1776. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.12.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM, Brown MZ, Gallop RJ, Heard HL, et al. Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs. therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:757–766. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch TR, Chapman AL, Rosenthal MZ, Kuo JR, Linehan MM. Mechanisms of change in dialectical behavior therarpy: Theoretical and empirical observations. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62:459–480. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AL, Wyman SE, Huppert JD, Glassman SL, Rathus JH. Analysis of behavioral skills use utilized by suicidal adolescents receiving dialectical behavior therapy. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2000;7:183–187. [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC. Personality assessment inventory: Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M. Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Robins CJ, Chapman AL. Dialectical behavior therapy: Current status, recent developments, and future directions. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2004;18:73–79. doi: 10.1521/pedi.18.1.73.32771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD. Using SAS PROC MIXED to fit multilevel models, hierarchical models, and individual growth models. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 1998;24:323–355. [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Pinsker-Aspen JH, Hilsenroth MJ. Borderline pathology and the Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI): An evaluation of criterion and concurrent validity. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2007;88:81–89. doi: 10.1080/00223890709336838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ. Borderline personality disorder features in nonclinical young adults: I. Identification and validation. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Useda D, Conforti K, Doan B. Borderline personality disorder features in young adults: 2. Two-year outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:307–314. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.2.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheul R, van den Bosch LMC, Koeter MWJ, de Ridder MAJ, Stijnen T, van den Brink W. Dialectical behavior therapy for women with borderline personality disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;182:135–140. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M. Diagnosing personality disorders: A review of issues and research methods. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:225–245. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950030061006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]