Abstract

Penile reconstruction still represents a formidable challenge for the urologist. In this review, the most recent advances in penile reconstruction after trauma, excision of benign and malignant disease and in patients with micropenis, aphallia or female to male gender dysphoria are reported.

Keywords: aphallia, female-to-male sex reassignment surgery, genital lymphoedema, lichen sclerosus, micropenis, penile cancer, penile trauma

Introduction

Over the past decades, reconstructive surgery of the penis has continued to evolve; however, due to the complexity of the penis, repairing and reconstructing this organ remains anatomically, functionally and aesthetically a great challenge. This is because the goal of penile reconstructive surgery is the achievement of a cosmetically acceptable and functional result in order to allow the patient to recover sexual and urinary function with confidence.

Ideally, in penile trauma, avulsion, partial or complete excision, surgical repair should be immediate with preservation of as much viable tissue as possible as no other tissue in the body has characteristics, in terms of elasticity, texture and colour, to be considered an ideal candidate for genital reconstruction. When primary repair with genital tissue is not feasible, skin grafts, and a variety of pedicled and free flaps are available for genital reconstruction.

Materials and methods

This review will concentrate on the techniques of penile reconstruction after traumatic amputation, excision of benign and malignant conditions and in patients with micropenis, aphallia and gender dysphoria. A non-structured PubMed search has been carried out using the following keywords: ‘penile trauma', ‘penile cancer', ‘micropenis', ‘aphallia', ‘female-to-male sex reassignment surgery', ‘genital lymphoedema' and ‘lichen sclerosus'. Only the most significant articles published on penile reconstruction have been selected. For simplicity, this review has been subdivided in glans and penile shaft reconstruction.

Glans reconstruction

Reconstruction of the glans in isolation is required following traumatic amputation or surgical excision for benign and malignant conditions such as lichen sclerosus (LS) and squamous cell carcinoma of the penis.

In particular, glans resurfacing is indicated in patients with LS or carcinoma in situ of the glans penis. The procedure, initially described by Depasquale et al.1 and Hadway et al.,2 involves the partial or complete excision of the glans mucosa, which is literally peeled off the underlying spongiosum, followed by repair with the use of a split-thickness skin graft (STSG) of non-genital skin.

Glans resurfacing is a simple and reproducible technique and guarantees that excellent cosmetic and functional results have been reported in almost all cases.3, 4 (Figure 1 and Table 1).

Figure 1.

Total glans resurfacing. (a) Complete involvement of the glans penis with partial meatal stenosis. (b) The glans and the coronal sulcus are completely denuded. The involved mucosa is excised preserving completely the underlying spongy tissue. (c) The denuded glans and corona are covered with a STSG that is quilted to recreate the coronal groove. (d) The final result after full glans resurfacing. STSG, split-thickness skin graft.

Table 1. Success rate of glans resurfacing.

| Study | Condition | No. of patients | Complications | Follow-up (month) | Recurrence rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depasquale et al. (2000)1 | LS | 5 | 0 | — | na |

| Garaffa et al. (2011)3 | LS | 31 | 5 | 12 | na |

| Hadway et al. (2006)2 | CIS | 10 | 0 | 30 | 0 |

| Shabbir et al. (2010)4 | CIS | 25 | 1 | 29 | 28 |

Abbreviations: CIS, carcinoma in situ, LS, lichen sclerosus; na, not available.

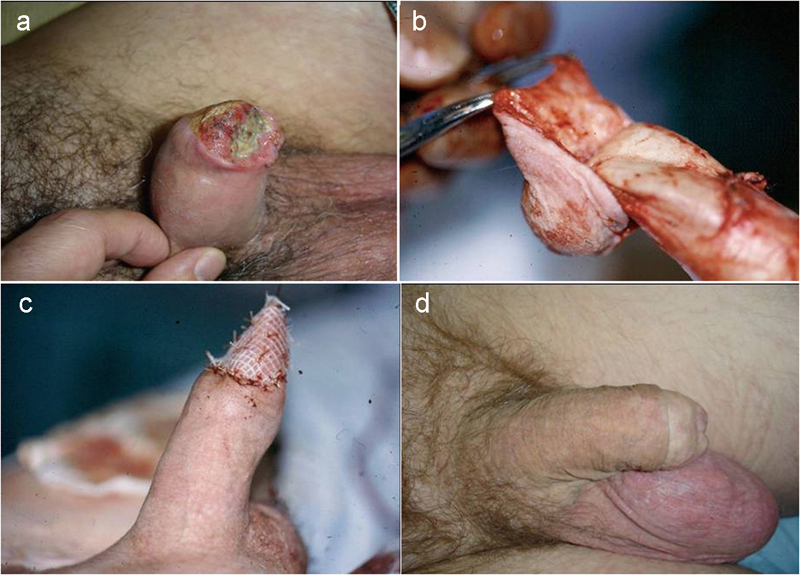

Glans reconstruction is necessary following traumatic amputation of the distal aspect of the shaft or following glansectomy, the surgical excision of the glans penis, which is dissected off the tip of the corpora cavernosa in patients with pT1 and pT2 squamous cell carcinoma of the glans.5, 6 Regardless of the cause of glans amputation, reconstruction can be achieved with a STSG that is applied on the corporal heads to form a pseudoglans (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Technique of glansectomy for squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. (a) Diffuse glans involvement by squamous cell carcinoma. (b) The glans is dissected off the tunica albuginea of the tip of the corpora cavernosa. (c) The denuded corporal tips are covered with a STSG harvested from the inner thigh to fashion a pseudo glans. (d) Final results 6 months postoperatively. STSG, split-thickness skin graft.

Glans reconstruction with the use of STSG is a simple and reproducible procedure. Complications include poor graft take requiring regrafting in around 6% of patients and inadequate final cosmetic or functional outcome in 1% of cases.5 Overall, almost all patients retain sexual and urinary function and are reported to be already engaging in satisfactory penetrative sex 3 months postoperatively.6

Alternatively, glans and coronal reconstruction can be also achieved with the use of urethral, rectus abdominis or palmaris longus flaps.7, 8 Although the results are satisfactory, only few cases reports have been described in the literature and therefore, larger series will be necessary to confirm the reliability of these techniques for glans reconstruction.

Penile shaft reconstruction

Indications for penile shaft reconstruction are penile skin loss, partial or subtotal penectomy, traumatic amputation of the penis, micropenis, aphallia or penile agenesis and female-to-male trans-sexualism.

Genitals skin loss can be consequence of trauma, infections such as Fournier's gangrene, burns, LS or iatrogenic as in the case of surgical excision of benign and malignant conditions or of excessive circumcision.

A variety of local skin flaps can be used for penile skin cover; however, the best cosmetic results are achieved with the use of skin grafts. In particular, full-thickness skin grafts (FTSG) guarantee superior results than their split thickness counterpart since they heal with less contracture and therefore preserve the physiological girth and length expansion during erection.9

Among benign conditions that require surgical excision of the affected penile skin and dartos followed by reconstruction, genital lymphoedema deserves to be cited separately. This condition, which arises when the lack of lymphatic drainage results in the abnormal retention of lymphatic fluid in the subcutaneous tissues, can be primary, in the presence of an abnormal development of the subcutaneous lymphatic system, or secondary to any conditions that may affect and impair the inguinal lymph nodes. Extended inguinal and pelvic node dissections, trauma, radiotherapy, malignant and granulomatous infiltration, venereal diseases and parasitic infections all involving the inguinal lymph nodes are all known causes of genital lymphoedema.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17

Surgical management of penile lymphoedema involves the complete excision of all the lymphoedematous tissue and of the overlying skin followed by repair with the use of skin grafts and local flaps. The lymphoedematous tissue is dissected off Buck's fascia because the swelling involves only the skin and the underlying dartos fascia. The affected skin must always be completely excised as undermining the margins, in the attempt to preserve the genital skin while excising the lymphoedematous tissue, invariably determines the disruption of the fine vascular supply to the skin, with consequent skin necrosis.

Since the inner layer of the prepuce has a separate lymphatic drainage along the dorsal neurovascular bundle towards the internal pudendal system, this structure is never involved by the lymphoedematous process and therefore should be spared and used for penile skin cover (Figure 3).9

Figure 3.

Surgical management of extensive penoscrotal lymphoedema. (a) Extensive penoscrotal lymphoedema. (b) After the isolation of cords and shaft, all the lymphoedematous tissue is excised. (c) The shaft is covered using the inverted inner preputial layer, which is not affected by the lymphoedema, and a FTSG harvested from a non-hair bearing area. (d) The final result after 6 months. FTSG, full-thickness skin graft.

Total phallic reconstruction instead is indicated in patients who have undergone partial or total penectomy, traumatic amputation, in the case of micropenis, aphallia or female-to-male trans-sexualism.

Patients who have suffered partial amputation of the penis are initially offered conservative management such as division of the suspensory ligament of the penis or excision of the suprapubic adiposity in order to maximize the length of the penile stump. If these procedures result in an insufficient length gain, with consequent incapacity of the patient to engage in penetrative sexual intercourse and void while standing, or in the presence of severe psychological distress, patients should be offered total phallic reconstruction.

Ideally, phallic reconstruction should allow the creation of a cosmetically acceptable sensate phallus with incorporated competent neourethra, to allow micturition while in the standing position, and with enough bulk to tolerate the insertion of a penile prosthesis for successful sexual penetration.

A single-stage procedure and minor disfigurement of the donor site are also desirable requisites.18

The complex anatomy and physiology of the penis and the fact that there is no good substitute for the unique erectile tissue of the corpora render reconstruction prohibitive for the surgeon; this is why, despite a variety of surgical techniques have been described, none fulfils all the ideal criteria.19, 20

The development of total phallic construction techniques has paralleled the evolution of flaps in plastic surgery and, after the initial attempt of Bogoras in 1936, who used a random pedicled oblique abdominal singular tubularized flap to create a phallus, a variety of techniques have been described in the literature.20, 21, 22

However, only the advent of microsurgical techniques in plastic surgery has represented the real breakthrough in phallic reconstruction with the initial description of the radial artery-based forearm free flap (RAFF) phalloplasty by Chang and Hwang23 and Song et al.24 This reconstructive procedure involved the creation of ‘a tube within a tube' using forearm skin with the urethra fashioned from the non-hair-bearing area and the whole flap base on the radial artery. Contrariwise to all previous techniques, the RAFF allowed the creation of a cosmetically acceptable sensate phallus of cylindrical shape.

Despite free osteocutaneous fibular flaps, anterolateral thigh flaps, latissimus dorsi flap and upper arm flaps have been introduced in order to minimize donor site morbidity, they are associated with poorer cosmetic results than the RAFF phalloplasty (Table 2).25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31

Table 2. Comparison of phalloplasty techniques.

| Technique | Cosmesis | Urethra | Sensation | Donor-site morbidity | Stages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gillies20 | Excellent | Yes | No | +++ | Multiple |

| Infraumbilical flap21 | Moderate | No | At the base | + | Single |

| Gracilis flap22 | Moderate | No | No | + | Single |

| OFF27 | Moderate | Yesa | Yes | + | 2 |

| ALT26, 28 | Good | Yesb | Yes | + | Single |

| LDF29 | Good | Yesa | Yes | ++ | Single |

| RAFF24, 25, 30, 31, 33 | Excellent | Yes | Yes | +++ | Multiple |

| RAFFU34 | Good | Yes | Yesc | + | Multiple |

Abbreviations: ALT, anterolateral thigh flaps; LDF, latissimus dorsi flap; OFF, osteocutaneous fibular flaps; RAFF, radial artery-based forearm free flap; RAFFU, radial artery-based free flap urethroplasty.

A prelaminated skin-graft urethroplasty can be fashioned and incorporated in the phallus. However, urethral complications can be as high as 50%.

A neourethra can be fashioned in a ‘tube within a tube' fashion only in patients with thin adipose layer. In patients with thick adipose layer, the ALT flap is not wide enough to be rolled in a ‘tube within a tube' fashion.

Sensation is present on the entire neourethra and at the base of the pedicled phalloplasty.

In particular, osteocutaneous flaps have been designed in order to guarantee the rigidity necessary to achieve successful penetrative intercourse; the main disadvantages of these flaps are that the phallus is difficult to conceal and the bone component tends to be progressively desorbed with consequent loss of rigidity.32 In miocutaneous flaps instead, muscle contracture is common and this leads to poor cosmetic results.

The RAFF phalloplasty involves three or four stages, which are usually carried out at 3 months distance from each other and the overall process takes at least 1 year. In general, the first stage consists in the creation of the phallus and transposition to the recipient site; in the transsexual, an additional second stage involves the anastomosis of the native to the phallic urethra. During this stage, the urethral anastomosis is protected until it is completely healed by diverting the urine with a suprapubic catheter. The third stage involves the sculpture of the glans according to the Norfolk technique and the insertion of the reservoir of a three-piece inflatable penile prosthesis, while in the last stage, the cylinders and the pump of the penile prosthesis are inserted and connected with the reservoir.

Total phallic reconstruction with the use of the RAFF is a reproducible technique. The most feared complication is acute venous thrombosis of the microsurgical anastomosis which occurs in around 3% of patients in postoperative days 3 and 4 and is characterized by a phallus that appears oozy and discolored and by a progressive weakening of the pulse. Due to its subtle onset, it is recognized invariably too late and leads to the complete loss of the phallus. Acute thrombosis of the arterial anastomosis is instead immediate and easily identifiable; therefore, immediate re-exploration of the anastomosis with preservation of the phallus is almost always possible. Partial necrosis of the phallus due to arterial or venous ischemia may occur in up to 10% of cases.30, 31

The most common long-term complications are neourethral stricture and fistulas, which occur respectively in around 10% and 20% of cases. Surgical correction is almost always possible and after revision surgery, 99% of patients are able to void standing from the tip of the phallus. Sensation on the phallus has been reported by 86% of patients with an overall satisfaction rate after revision surgery of 97% (Figure 4).30, 31

Figure 4.

The final result after RAFF phalloplasty. RAFF, radial artery-based forearm free flap.

The main drawback of this type of phalloplasty is donor-site morbidity. Although good cosmetic and functional results can be achieved with adequate preparation of the donor site for grafting and with the use of FTSG to cover the defect, the residual scar on the arm still represents a ‘stigma' for patients.30, 31, 33

Therefore, patients who wish to achieve cosmetic and functional results similar to the one provided by the RAFF but want to minimize the donor-site morbidity can be offered the incorporation of a 4 cm wide tubularized free flap based on the radial artery in a prefashioned infraumbilical flap phalloplasty to create a neourethra. This technique is called radial artery-based free flap urethroplasty. In a recent series of 27 patients, this technique, called radial artery-based free flap urethroplasty yielded excellent cosmetic and functional results and all patients who have completed the two stages of the procedure were able to void from the tip of the phallus and had acceptable donor-site morbidity due to the smaller size of the flap.34

Penile prosthesis implantation in phalloplasty is necessary to guarantee the adequate rigidity to allow patients to engage in penetrative sexual intercourse and is carried out at least 1 year after the formation of the phalloplasty in order to allow the phallus to recover adequate cutaneous sensation.

Due to the absence of tunica albuginea, only hydraulic devices should be implanted, and the cylinders are housed in a Goretex or Dacron sheath to anchor them to the pubic branch and to prevent distal erosion.

Penile prosthesis insertion in a phalloplasty is associated with high risk of complications. This is due to the absence of the tunica albuginea that protects the cylinders from traumas and erosion and to the necessity to use foreign materials to house the cylinders.

In a recent series of 129 patients who have undergone penile prosthesis implantation in phalloplasty, infection rate, erosion rate and mechanical dysfunction of the device were respectively 11.9%, 8.1% and 22.2% with an overall revision rate of 41%. Overall, up to 60% of patients had a normally functioning penile prosthesis, were able to cycle the device and, potentially, to have penetrative sexual intercourse.35

Conclusions

In glans reconstruction, the best results are achieved with the use of STSG, while defects on the shaft are better dealt with FTSG since they allow the preservation of the physiological girth and length expansion during erection.

For total phallic reconstruction, the RAFF phalloplasty with delayed insertion of a hydraulic penile prosthesis guarantees excellent cosmetic and functional results.

Author contributions

GG and AAR wrote the paper. GG carried out the literature review. DJR reviewed the draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Depasquale I, Park AJ, Bracka A. The treatment of balanitis xerotica obliterans. BJU Int. 2000;86:459–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadway P, Corbishley CM, Watkin N. Total glans resurfacing for premalignant lesions of the penis: initial outcome data. BJU Int. 2006;98:532–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garaffa G, Shabbir M, Christopher AN, Minhas S, Ralph DJ.The surgical management of lichen sclerosus of the glans penis: our experience and review of the literature J Sex Mede-pub ahead of print 6 Jan 2011; doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02165.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Shabbir M, Muneer A, Kalsi J, Shuckla CJ, Zacharakis E, et al. Glans resurfacing for the treatment of carcinoma in situ of the glans penis: surgical technique and outcomes. Eur Urol. 2011;59:142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak P, Corbishley, Watkin N. Organ-sparing surgery for invasive penile cancer: early follow-up data. BJU Int. 2004;94:1253–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.05153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morelli G, Pagni R, Mariani C, Campo G, Menchini-Fabris F, et al. Glansectomy with split-thickness skin graft for the treatment of penile carcinoma. Int J Impot Res. 2009;21:311–4. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2009.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgado CJ, Licata L, Fuller DA, Chen HC, Mardini S. Glans penis coronaplasty with palmaris longus tendon following total penile reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2009;62:690–2. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31817f0228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaeer O, El-Sebaie A. Construction of neoglans penis: a new sculpturing technique for rectus abdominis myofasical flap. J Sex Med. 2005;2:259–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.20237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garaffa G, Christopher AN, Ralph DJ. The management of genital lymphoedema. BJU Int. 2008;102:408–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson RA, Alberts GL, King LE., Jr Penile and scrotal elephantisis caused by indolent chlamidia trachomatis infection. Urology. 2003;61:224. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter W, Bunker C. Chronic penile lymphoedema: a report of 6 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1108–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy MJ, Kogan B, Carlson JA. Granulomatous lymphangitis of the scrotum and the penis. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:419–24. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2001.028008419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver HM, Tsangaris NT, Eaton OM. Lymphoedema and lymphography in sarcoidosis. Arch Intern Med. 1966;117:712–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhlemann MF, Walker NP, Tan LB, Champion RH. Elephantine sarcoidosis presenting as ulcerating lymphoedema. J R Soc Med. 1985;78:260–1. doi: 10.1177/014107688507800319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham G, Blake PG, Mathews R, Bargman JM, Izatt S, et al. Genital swelling as a surgical complication of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1990;170:306–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshmukh N, Kjellberg SI, Shaw PM. Occult inguinal hernia, a cause of rapid onset of penile and scrotal edema in subjects on chronic peritoneal dialysis. Mil Med. 1995;160:597–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolt RJ, Peelen W, Nikkels PG, de Jong TP. Congential lymphodema of the genitalia. Eur J Pediatr. 1998;157:943–6. doi: 10.1007/s004310050973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogoras N.Uber die volle plastische wiederherstellung eines zum Koitus fahigen Penis (peniplastica totalis) Zentralbl Chir 1936631271German. [Google Scholar]

- Babaei A, Safarinejad MR, Farrokhi F, Iran-Pour E. Penile reconstruction: evaluation of the most accepted techniques. Urol J. 2010;7:71–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillies HD, Harrison RJ. Congenital absence of the penis with embryological consideration. Br J Plast Urol. 1948;1:8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettocchi C, Ralph DJ, Pryor JP. Pedicled pubic phalloplasty in females with gender dysphoria. BJU Int. 2004;95:120–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.05262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persky L, Resnick M, Desprez J. Penile reconstruction with gracilis pedicle grafts. J Urol. 1983;129:603–5. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)52255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang TS, Hwang WY. Forearm flap in one-stage reconstruction of the penis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;74:251–8. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198408000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song R, Gao Y, Song Y, Yu Y, Song Y. The forearm flap. Clin Plast Surg. 1982;9:21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DA, Schlossberg SM, Jordan GH. Ulnar forearm phallic reconstruction and penile reconstruction. Microsurgery. 1995;16:314–21. doi: 10.1002/micr.1920160506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubino C, Figus A, Dessy LA. Alei G, Mazzocchi M et al. Innervated island pedicled anterolateral thigh flap for neo-phallic reconstruction in female-to-male transsexuals. J Urol. 1993;150:1093–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2007.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopulos NA, Schaff J, Biemer E. The use of free prelaminated and sensate osteofasciocutaneous fibular flap in phalloplasty. Int J Care Injured. 2008;39 Suppl 3:S62–7. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felici N, Felici A. A new phalloplasty technique: the free anterolateral thigh flap phalloplasty. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:153–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perovic SV, Djinovic R, Bumbasirevic M, Djordjevic M, Vukovic P. Total phalloplasty using a musculocutaneous latissimus dorsi flap. BJU Int. 2007;100:899–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garaffa G, Christopher NA, Ralph DJ. Total phallic reconstruction in female to male transsexuals. Eur Urol. 2010;57:715–22. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garaffa G, Raheem AA, Christopher NA, Ralph DJ. Total phallic reconstruction after penile amputation for carcinoma. BJU Int. 2009;104:852–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgado CJ, Chim H, Rowe D, Bodner DR. Vascularized cadaveric fibula flap for treatment of erectile dysfunction following failure of penile implants. J Sex Med. 2010;7:3504–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvaggi G, Monstrey S, Hoebeke P, Ceulemans P, van Landuyt K, et al. Donor-site morbidity of the radial forearm free flap after 125 phalloplasties in gender identity disorder. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118:1171–7. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000221110.43002.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garaffa G, Ralph DJ, Christopher N. Total urethral construction with the radial artery based forearm free flap in the transsexual. BJU Int. 2010;106:1206–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoebeke PB, Decaesteker K, Beysens M, Opdenakker Y, Lumen N, et al. Erectile implants in female-to-male-transsexuals: our experience in 129 patients. Eur Urol. 2010;57:334–40. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]