Abstract

We identified a genotype G10P[14] rotavirus strain in 5 children and 1 adult with acute gastroenteritis from the Northern Territory, Australia. Full genome sequence analysis identified an artiodactyl-like (bovine, ovine, and camelid) G10-P[14]-I2-R2-C2-M2-A11-N2-T6-E2-H3 genome constellation. This finding suggests artiodactyl-to-human transmission and strengthens the need to continue rotavirus strain surveillance.

Keywords: Rotavirus, G10P[14], group A rotavirus full genome analysis, Australia, enteric infections, indigenous Australian, viruses, acute gastroenteritis, zoonoses

Group A rotavirus infection is the major cause of acute gastroenteritis in children worldwide. The rotavirus genome consists of 11 segments of double-stranded RNA encoding 6 structural viral proteins (VP1–4, VP6, VP7) and 6 nonstructural proteins (NSP 1–5/6) (1). Genotypes are assigned on the basis of 2 outer capsid proteins into G (VP7) and P (VP4) genotypes; these proteins also elicit type-specific and cross-reactive neutralizing antibody responses (1). Strains that include genotypes G1P[8], G2P[4], G3P[8], G4P[8], and G9P[8] cause most rotavirus disease in humans (1). Since 2008, rotaviruses have been classified by using the open reading frame of each gene. The nomenclature Gx-P[x]-Ix-Rx-Cx-Mx-Ax-Nx-Tx-Ex-Hx represents the genotypes of the gene segments encoding VP7-VP4-VP6-VP1-VP2-VP3-NSP1-NSP2-NSP3-NSP4-NSP5/6 (2). To date, 27 G, 35 P, 16 I, 9 R, 9 C, 8 M, 16 A, 9 N, 12 T, 14 E, and 11 H genotypes have been described (2).

Two live oral vaccines are available globally: Rotarix (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia) and RotaTeq (Merck, Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA). Rotarix is a monovalent vaccine that contains a single human G1P[8] strain (3). RotaTeq is a pentavalent vaccine comprised of 5 human–bovine reassortant virus strains (3). Both vaccines were introduced into the Australian National Childhood Immunization Program in July 2007. The strategy of a rotavirus vaccination program is to target the most frequently circulating rotavirus strain(s) and provide homotypic and heterotypic protection.

G10P[14] rotavirus strains are rarely reported as the source of infection in humans. Of 7 previously reported G10P[4] rotavirus infections, 1 each was in the United Kingdom and Thailand and 5 were in Slovenia (4). During 2011, the Australian Rotavirus Surveillance Program identified 6 G10P[14] strains in the Northern Territory (NT). We report the characterization of G10P[14] strains detected in Australia.

The Study

Six rotavirus-positive specimens collected from NT were genetically untypeable by reverse transcription PCR (Technical Appendix). Sequence analysis of the VP7 and VP4 genes of these strains demonstrated highest nucleotide identity with G10 and P[14] rotaviruses, respectively. The G10P[14] strains were from specimens collected from 5 children and 1 adult (84 years of age) during August and September 2011 (Table 1). Of the 6 G10P[14] case-patients, 5 were from Tennant Creek, NT, ≈1,000 km south of Darwin in northern Australia; the residence of the other case-patient is unknown. All strains were detected in indigenous Australians. Specimens V585, V582, and WDP280 were collected from case-patients who had received 2 doses of Rotarix, and specimen SA179 was collected from a case-patient who had received 1 dose. No vaccination data were available for the case-patient from whom specimen SA175 was collected.

Table 1. Cohort and vaccination status for novel G10P[14] rotavirus strain, Northern Territory, Australia, 2011* .

| Case-patient specimen ID | Case-patient age | Date specimen collected | Location (postal code) of specimen collection† | Rotavirus vaccine (no. doses)‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V582 | 8 mo | Aug 13 | 0860 | Rotarix (2) |

| WDP280 | 10 mo | Aug 19 | 0872 | Rotarix (2) |

| V585 | 2 y | Aug 19 | 0860 | Rotarix (2) |

| SA175 | 3 mo | Sep 2 | Unknown | Unknown |

| SA179 | 4 mo | Sep 6 | 0872 | Rotarix (1) |

| D355 | 84 y | Sep 11 | 0860 | Not applicable |

*ID, identification. †Postal code zone 0860 encompasses Tennant Creek, Northern Territory; samples WDP280 and SA179 were collected in post code zone 0872, in communities near code zone 0860. ‡Rotarix, Glaxo SmithKlineBiologicals, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Sanger sequencing was used to generate the complete genome of specimen V585 (Technical Appendix). For the other 5 G10P[14] strains, the complete open reading frames of VP7, VP4, NSP4, and NSP5 and partial reading frames of VP1, VP2, VP3, VP6, NSP1, and NSP2 were sequenced (Table 2, Appendix). These 5 strains demonstrated >99.5% sequence identity to V585, confirming that V585 was representative of all 6 strains. The genotype of each segment of V585 was determined by using RotaC version 2.0 (http://rotac.regatools.be), a web-based genotyping tool for group A rotaviruses; a G10-P[14]-I2-R2-C2-M2-A11-N2-T6-E2-H3 constellation was identified. Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic analyses were performed by using full-length open reading frame nucleotide sequences of V585 and other group A rotavirus strains (Technical Appendix). The nucleotide sequences of the 11 gene segments of V585 and the VP7 and VP4 genes of the other 5 G10P[14] strains were deposited in GenBank (accession nos. JX567748–JX567768).

Table 2. Number of nucleotide differences between RVA/human-wt/AUS/V585/2011/G10P[14] and other G10P[14] rotavirus strains*.

| Strain |

RVA/human-wt/AUS/V585/2011/G10P[14] nucleotide sequences† | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VP1 (887) |

VP2 (1285) |

VP3 (612) |

VP4 (2331) |

VP6 (1203) |

VP7 (981) |

NSP1 (1449) |

NSP2 (879) |

NSP3 (914) |

NSP4 (725) |

NSP5 (618) |

|

| D355 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SA175 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| SA179 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| V582 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| WDP280 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| *The number of bases differences between RVA/human-wt/AUS/V585/2011/G10P[14] and other G10P[14] strains for each genome segment is shown. VP, viral protein; NSP, nonstructural protein. †Numbers in parentheses are the final number of nucleotide positions analyzed for each genome segment. | |||||||||||

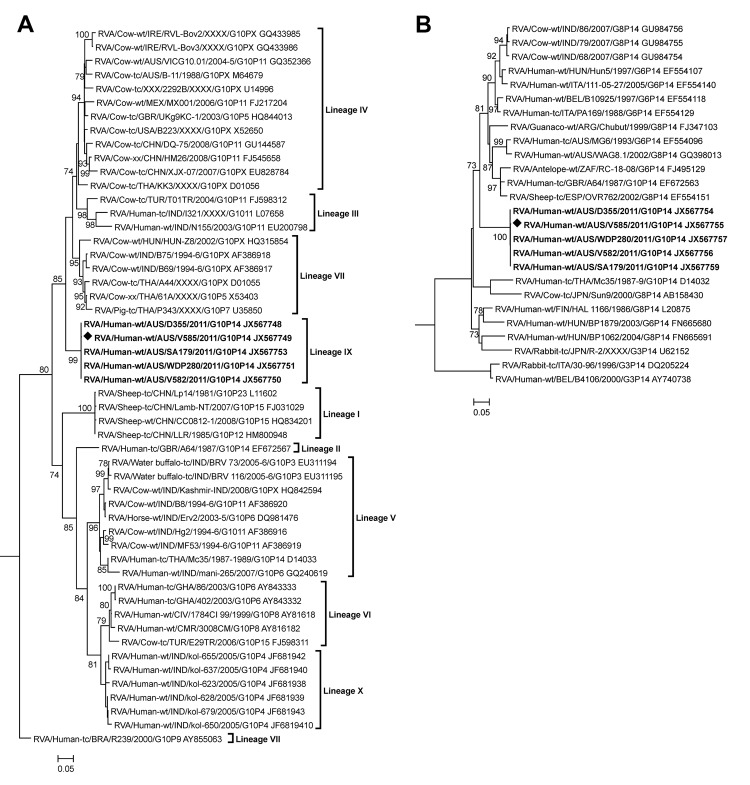

Phylogenetic analysis of the VP7 gene identified 10 lineages (Figure 1, panel A). The 6 G10P[14] strains from NT (lineage IX) were distinct from human G10P[14] rotaviruses RVA/human-tc-GBR/A64/1987/G10P14 (lineage II) and RVA/human-tc/THA/Mc35/1987–1989/G10P[14] (lineage V), and they were most closely related to bovine strains identified predominantly in Ireland, China, and Australia (lineage IV). V585 had the highest level of nucleotide identity (92.5%) to the bovine strain RVA/cow-wt/IRE/RVL-Bov3/XXXX/G10P[X] (Table 3). Nucleotide identity was lower to Australian bovine G10 strains RVA/cow-wt/AUS/VICG10.01/2004-5/G10P[11] (91.1%) and RVA/cow-tc/AUS/B-11/1099/G10P[X] (90.6%).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic trees constructed from the nucleotide sequences of viral protein (VP) 7 gene (A) and VP4 gene (B) of rotavirus strain V585; other group A rotavirus strains represent the G10 and P[14] genotypes. The reference strain RVA/human-tc/USA/Wa/1974/G1P[8] was included as an outgroup in the phylogenetic analysis but is not shown in the final tree. The position of strain V585 is indicated by a solid diamond, and all strains from this study are in boldface. Bootstrap values >70% are shown. Scale bars show 0.05 nt substitutions per site. The nomenclature of all the rotavirus strains indicates the rotavirus group, species isolated from, country of strain isolation, the common name, year of isolation, and the genotypes for genome segment 9 and 4, as proposed by the Rotavirus Classification Working Group (2).

Table 3. Nucleotide identity of 11 genome segments of the G10P[14] rotavirus strain V585, Northern Territory, Australia*.

| Gene encoding | Genotype of V585 | Cutoff value† | Identity of V585 against indicated strains |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype reference strain | GenBank strains‡ | |||

| VP1 | R2 | 83 | 85.6 (DS-1) | 96.9 (GirRV) |

| VP2 | C2 | 84 | 84.9 (DS-1) | 89.5 (B12) |

| VP3 | M2 | 81 | 85.1 (DS-1) | 88.9 (MG6) |

| VP4 | P[14] | 80 | 87.4 (A64) | 88.9 (B10925) |

| VP6 | I2 | 85 | 86.6 (DS-1) | 93.8 (RotaTeq BrB-9/SC2-9/W17-9) |

| VP7 | G10 | 80 | 86.8 (A64) | 92.5 (RVL-Bov3) |

| NSP1 | A11 | 79 | 79.9 (Hun5) | 80.2 (BP1879) |

| NSP2 | N2 | 85 | 87.4 (DS-1) | 94.3 (B12) |

| NSP3 | T6 | 85 | 92.4 (WC3) | 94.0 (GirRV/A64) |

| NSP4 | E2 | 85 | 88.7 (DS-1) | 90.8 (Azuk-1) |

| NSP5 | H3 | 91 | 92.9 (AU-1) | 94.1 (RUBV81/Egy3399) |

*VP, viral structural protein; NSP, nonstructural protein. †Numeric values are given as percentage nucleotide identity. Percentage nucleotide cutoff values, genotype designation, and genotype reference strains proposed in (2). ‡Strains that shared the highest nucleotide identity with the Australian G10P[14] strain V585.

The VP4 genes of the G10P[14] strains from NT formed a cluster distinct from other characterized P[14] sequences identified globally from humans and animals (Figure 1, panel B). V585 had the highest level of nucleotide identity (88.9%) to the human strain RVA/human-wt/BEL/B10925/1997/G6P[14] (Table 3). Nucleotide identity was lower to other Australian P[14] sequences, RVA/human-tc/AUS/MG6/1993/G6P[14] (87.5%) and RVA/human-wt/AUS/WAG8.1/2002/G8P[14] (87.2%).

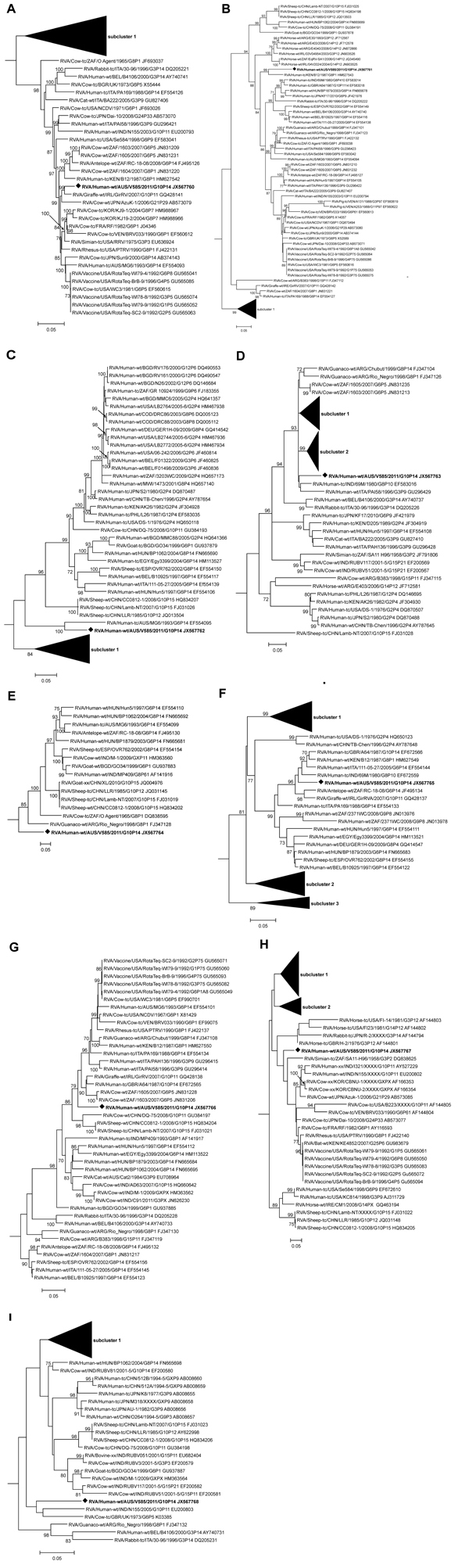

Phylogenetic analysis of VP1, VP2, NSP2, and NSP3 demonstrated that V585 clustered with genes of rotaviruses identified in the mammalian order Artiodactyla (bovine, ovine, and camelid) and human strains derived from zoonotic infections (Figure 2, Appendix). Similarly, VP3, which clustered with the RVA/human-tc/AUS/MG6/1993/G6P[14], was thought to be the result of zoonotic transmission (5) (Figure 2, Appendix, panel C). NSP1, NSP4, and NSP5 clustered with sequences from artiodactyl hosts, however branching was not supported by significant bootstrap values (Figure 2, Appendix, panels E, H, I). The NSP1 and NSP5 genes were divergent from sequences that define their respective genogroups (Table 3). Overall, the 11 genome segments of the G10P[14] strains from NT had relatively low nucleotide identity (80.2%–96.9%) to other strains in each of the respective genogroups, demonstrating that this G10P[14] strain identified in Australia was divergent from other strains identified globally (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic trees constructed from the nucleotide sequences of genes of rotavirus strain V585 and other group A rotavirus strains representing the R2, C2, M2, I2, A11, N2, T6, E2, and H3 genotypes. A) Viral protein (VP) 1, B) VP2, C) VP3, D) VP6, E) nonstructural protein (NSP) 1, F) NSP2, G) NSP3, H) NSP4, and I) NSP5. The reference strains for each genogroup were included in the phylogenetic analysis, but only the relevant genotype to V585 is shown in the final tree. The position of strain V585 is indicated by an open square, and all strains from this study are in boldface font. Bootstrap values >70% are shown. Scale bar shows 0.05 nt substitutions per site. The nomenclature of all the rotavirus strains indicates the rotavirus group, species isolated from, country of strain isolation, the common name, year of isolation, and the genotypes for genome segment 9 and 4, as proposed by the Rotavirus Classification Working Group (2).

Conclusions

The V585 strain possessed a G10-P[14]-I2-R2-C2-M2-A11-N2-T6-E2-H3 genome constellation. With the exception of the VP7 gene, the constellation is consistent with G6P[14] and G8P[14] strains identified globally: G6/G8-P[14]-I2-(R2/R5)-C2-M2-(A3/A11)-N2-T6-(E2/E12)-H3 (6). Human P[14] strains are related to rotavirus strains isolated from even-toed ungulates belonging to the mammalian order Artiodactyla (6). Consistent with this observation, each individual genome segment of V585 was most closely related to artiodactyl-derived strains or human zoonotic rotavirus strains characterized to be derived from artiodactyl hosts. In Australia, G10P[11] strains have been isolated from calves, and G8P[14] strains and G6P[14] strains have been isolated from children (7,8). However, the V585 strain demonstrated modest nucleotide identity with these 3 strains identified in Australia. These data suggest that V585 is novel and probably derived from a strain circulating in an artiodactyl host and transmitted to humans. A large feral animal population, including goats, rabbits, and camels, exists in the region where these specimens were collected, thereby supporting the possibility of an interspecies transmission event (9).

Vaccination with the monovalent G1P[8] Rotarix is available in NT, where 2-dose vaccine coverage is 74% for indigenous Australian infants (10). Rotarix vaccination status was available for 4 of the 5 children in this study: 3 were fully vaccinated, and 1 had received the primary dose. The heterotypic G10P[14] strain identified in these vaccinated children suggests a lack of protective immunity, although it cannot be excluded that vaccination provided protection against severe disease from other genotypes. Vaccine effectiveness against gastroenteritis leading to hospitalization has been variable in NT; vaccine was estimated to be 77.7% effective during a 2007 G9P[8] outbreak (11) and 19% effective against a fully heterotypic G2P[4] strain in 2009 (12). Rotarix has been effective for decreasing rotavirus infection notification rates in Darwin, NT (10), and New South Wales (13). However, in 1 location in central NT, reported rotavirus infection rates have remained similar in the vaccine era to those in the prevaccine era (10), suggesting low vaccine uptake, low vaccine take, or waning immunity. The living conditions of the indigenous Australian population in central NT are typically crowded, with inadequate facilities for sanitation and food preparation (14). The number of diarrheal disease cases is high: admissions coded for enteric infections in NT indigenous Australian infants occur at a rate 10-fold higher than among nonindigenous Australian infants (15). The concurrent medical conditions present in the NT indigenous Australian population, combined with diversity of circulating rotavirus types, may have contributed to a lack of immunity. Detection of these unusual G10P[14] strains emphasizes the need for continued rotavirus surveillance to help guide current and future vaccination strategies.

Detailed descriptions of the methods and materials used and primers used for full genome characterization of rotavirus G10P[14].

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the assistance of Heather Cook, Centre for Disease Control, Department of Health, NT, for collection and supply of patient information.

C.D.K. is a codeveloper of an investigational rotavirus vaccine.

C.D.K. is director of the Australian Rotavirus Surveillance Program, which is supported by research grants from vaccine manufacturers CSL and GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals. This work was supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (1031473); the Australian Commonwealth Department of Health and Aging; GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals; and CSL (Melbourne). C.D.K. is supported by a Career Development Award from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (607347). This study was supported by the Victorian Government's Operational Infrastructure Support Program.

Biography

Dr Cowley is a molecular virologist at the Murdoch Childrens Research Institute. His research interests include the molecular characterization and evolution of rotavirus strains in the community of Australia.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Cowley D, Donato CM, Roczo-Farkas S, Kirkwood CD. Novel G10P[14] rotavirus strain, Northern Territory, Australia. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2013 Aug [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1908.121653

These authors contributed equally to this article.

References

- 1.Estes MK, Kapikian AZ. Rotviruses. In: Fields BN, Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields virology, 5th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. p. 1917–74. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matthijnssens J, Ciarlet M, McDonald SM, Attoui H, Banyai K, Brister JR, et al. Uniformity of rotavirus strain nomenclature proposed by the Rotavirus Classification Working Group (RCWG). Arch Virol. 2011;156:1397–413 . 10.1007/s00705-011-1006-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soares-Weiser K, Maclehose H, Bergman H, Ben-Aharon I, Nagpal S, Goldberg E, et al. Vaccines for preventing rotavirus diarrhoea: vaccines in use. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2:CD008521 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steyer A, Bajzelj M, Iturriza-Gomara M, Mladenova Z, Korsun N, Poljsak-Prijatelj M. Molecular analysis of human group A rotavirus G10P[14] genotype in Slovenia. J Clin Virol. 2010;49:121–5 . 10.1016/j.jcv.2010.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palombo EA, Bishop RF. Genetic and antigenic characterization of a serotype G6 human rotavirus isolated in Melbourne, Australia. J Med Virol. 1995;47:348–54 . 10.1002/jmv.1890470410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matthijnssens J, Potgieter CA, Ciarlet M, Parreno V, Martella V, Banyai K, et al. Are human P[14] rotavirus strains the result of interspecies transmissions from sheep or other ungulates that belong to the mammalian order Artiodactyla? J Virol. 2009;83:2917–29 . 10.1128/JVI.02246-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swiatek DL, Palombo EA, Lee A, Coventry MJ, Britz ML, Kirkwood CD. Detection and analysis of bovine rotavirus strains circulating in Australian calves during 2004 and 2005. Vet Microbiol. 2010;140:56–62 . 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swiatek DL, Palombo EA, Lee A, Coventry MJ, Britz ML, Kirkwood CD. Characterisation of G8 human rotaviruses in Australian children with gastroenteritis. Virus Res. 2010;148:1–7 . 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grant J. Feral animals in the NT 2012. [cited 2012 Aug 15]. http://www.lrm.nt.gov.au/feral

- 10.Snelling TL, Markey P, Carapetis JR, Andrews RM. Rotavirus in the Northern Territory before and after vaccination. Microbiol Aust. 2012;33:61–3 http://journals.cambridgemedia.com.au/UserDir/CambridgeJournal/Articles/05snelling412.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snelling TL, Schultz R, Graham J, Roseby R, Barnes GL, Andrews RM, et al. Rotavirus and the indigenous children of the Australian outback: monovalent vaccine effective in a high-burden setting. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:428–31 . 10.1086/600395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snelling TL, Andrews RM, Kirkwood CD, Culvenor S, Carapetis JR. Case–control evaluation of the effectiveness of the G1P[8] human rotavirus vaccine during an outbreak of rotavirus G2P[4] infection in central Australia. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:191–9. 10.1093/cid/ciq101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buttery JP, Lambert SB, Grimwood K, Nissen MD, Field EJ, Macartney KK, et al. Reduction in rotavirus-associated acute gastroenteritis following introduction of rotavirus vaccine into Australia's National Childhood vaccine schedule. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30(Suppl):S25–9 and. 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181fefdee [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Australian Bureau of Statistics. The health and welfare of Australia's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. 2010. [cited 2012 Aug 27]. http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/lookup/4704.0Main+Features1Oct+2010

- 15.Li QS, Guthridge S, d'Espaignet ET, Paterson B. From infancy to young adulthood: Health status in the Northern Territory, 2006. In: Department of Health and Community Services, Darwin, Australia. 2006. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Detailed descriptions of the methods and materials used and primers used for full genome characterization of rotavirus G10P[14].