Abstract

Objective

This multisite randomized trial addressed risks and benefits of staying on long-acting injectable haloperidol or fluphenazine versus switching to long-acting injectable risperidone microspheres.

Method

From December 2004 until March 2008, adult outpatients with a SCID diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who were taking haloperidol decanoate (n=40) or fluphenazine decanoate (n=22) were randomly assigned to Stay on current long-acting injectable medication or Switch to risperidone microspheres and followed for 6 months under study protocol and an additional 6 months naturalistic follow-up. Kaplan-Meier and Cox regression analyses were used to examine the primary outcome, time-to-treatment-discontinuation, and random regression models were used to examine secondary outcomes.

Results

Groups did not differ in time-to-treatment-discontinuation through 6 months of protocol-driven treatment. When the 6 month naturalistic follow-up period was included, time-to-treatment-discontinuation was significantly shorter for individuals assigned to Switch than for individuals assigned to Stay (10% of Stayers discontinued versus 31% of Switchers; p =.01). Groups did not differ with respect to psychopathology, hospitalizations, sexual side effects, new-onset TD, or new onset EPS. However, those randomized to Switch to long-acting injectable risperidone microspheres had greater increases in body mass (increase of 1.0 BMI versus decrease of −0.3 BMI ; p=.00) and prolactin (maximum increase to 23.4 ng/ml versus decrease to 15.2 ng/ml, p=.01) compared to those randomized to Stay.

Conclusion

Switching from haloperidol decanoate or fluphenazine decanoate to risperidone microspheres resulted in more frequent treatment discontinuation as well as significant weight gain and increases in prolactin.

Introduction

Current outcomes for most people with schizophrenia are disappointing. Hence, a compelling clinical question regularly faced by people with schizophrenia and their prescribers is, "Should I stay on my current antipsychotic regimen or switch to a different one?" Schizophrenia PORT1 guidelines recommend long-acting injectable antipsychotic maintenance therapy for persons who have difficulty complying with oral medication or who prefer regimens of relatively widely spaced injections. An important open question for people taking first-generation long-acting injectable medications who are not symptom free is whether the benefits of changing to a second generation long-acting injectable outweigh the relative risks and costs. Because the cost-per-day of risperidone microspheres (RM) is over 50 times that of first-generation long-acting injectable antipsychotic medications, this question is of particular interest to payers.

To date, RM has been compared to placebo2 or to oral antipsychotic medications3–4. A randomized controlled trial (RCT) that compared RM (25 mg, 50 mg, or 75 mg) to placebo found that RM is more efficacious than placebo and is well tolerated, especially at lower dosages2. Further, RM continued to be well tolerated for a year or longer5. This study excluded those who received a long-acting injectable antipsychotic medication within 120 days5. More recent RCTs have compared RM to oral antipsychotics. Chue et al3 found no significant differences between RM and oral risperidone. Keks et al4 had similar results in comparison to olanzapine. A two-year RCT comparing RM to quetiapine6 found significantly longer time to relapse with RM, and most recently, Rosenheck et al7 reported no significant differences between RM and psychiatrists’ choice of oral antipsychotic. A non-randomized prospective study examining a switch from first-generation depot antipsychotics to RM concluded that patients could be switched without compromising clinical stability8. However, this study did not include a comparison to individuals who remained on first-generation injectables.

We provide data from an RCT addressing relative risks and benefits of staying on a first-generation injectable antipsychotic versus switching to a second-generation injectable antipsychotic, RM, in patients currently taking FD or HD. We studied RM because it was the first second-generation long-acting injectable available for clinical use.

Method

Study Participants

Between December 2004 and March 2008, 15 study sites in the NIMH Schizophrenia Trials Network and 5 sites in Connecticut’s public mental health system recruited individuals 18 and older with a SCID diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who were currently taking FD or HD (defined by plasma level >0 for the prescribed antipsychotic or chart documentation of a recent injection). Eligible patients were those who might benefit from a switch to RM – specifically, those with sub-optimal response to treatment because of persistent psychopathology or significant side effects. However, we did not enroll anyone whose symptoms or side effects were so severe that a medication change was indicated immediately. Hence, we only enrolled individuals for whom a change in medication was a reasonable clinical option but not required. Additional inclusion criteria were: willingness to change antipsychotic medication, access to medications without financial burden, and at least one clinic visit every 3 months for the past 6 months. Additional exclusion criteria included: exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms within prior 3 months resulting in significant intervention (e.g. psychiatric hospitalization, services from crisis intervention or psychiatric emergency department); living in a skilled nursing facility due to physical condition or disability; pending criminal charges; currently pregnant or breastfeeding; prescribed more than one antipsychotic medication (oral risperidone was allowed). This research was conducted with approval from participating institutions’ institutional review boards.

After thorough description of the study to participants and assessment of understanding of consent materials, clinical interviewers obtained written informed consent to participate. (Online supplement includes a CONSORT diagram detailing recruitment flow.)

Study design and treatment

Following baseline assessment, participants were randomly assigned to either Stay on current injectable medication or to Switch to RM. Randomization was stratified by gender and by baseline decanoate. No exceptions were made to the pre-determined randomization streams.

Participants assigned to Switch to RM and who hadn’t taken oral risperidone previously received oral risperidone for at least a week to identify and exclude anyone with an idiosyncratic untoward reaction to risperidone. Those who had previously tolerated oral risperidone proceeded directly to RM. Participants receiving HD injections every 4 weeks received their first dose of RM the same day they received their last dose of HD and received RM every two weeks thereafter. Those receiving FD every 2 weeks received RM the same day that they received their last two FD injections and received RM every two weeks thereafter. Condition entry was defined as the date the participant was informed of and began the randomized treatment assignment.

The protocol specified that study participants continue their assigned treatment for six months unless clinically contraindicated. Medication dosing was unconstrained by study protocol; prescribers used clinical judgment to adjust dosages of assigned treatment if indicated. The protocol allowed use of adjunctive or concomitant psychotropic medications other than antipsychotic medications. After the 6-month study period, assessment continued for an additional 6 months of naturalistic follow-up. Treatment throughout was open label with assessment by blinded clinical raters. During both protocol-specified and naturalistic follow-up, study medications were not supplied by the study; participants were required to have access to study medications without financial burden (e.g., through entitlements).

Baseline measures

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) P (patient version)9 provided a research diagnoses. Chart review and participant interview informed socio-demographic information and psychiatric history.

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome measure was time to all-cause medication discontinuation. Record reviews provided start and stop dates for each dosage of each medication prescribed and dates of each injection.

Secondary outcome measures

Secondary outcomes included psychiatric symptoms, hospitalization, and medication adverse events assessed at baseline and 6 follow-up points: 2 weeks, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, and 12 months after condition entry.

We used the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)10 to assess psychiatric symptoms. Dates of inpatient hospitalization were obtained from a self-report calendar augmented by record review.

Other secondary measures included Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale(AIMS)11 and Simpson-Angus Extrapyramidal Side Effect Scale12 for extra-pyramidal side effects, Arizona Sexual Experiences Scale13 for sexual functioning, and Subjective Side Effect Rating Scale14 for distress from common side effects of antipsychotic medications. We recorded participants’ pulse, blood pressure, height, weight, waist and hip measurements, serum prolactin levels, lipid panels, and blood and urine glucose levels. Outcomes collected but not reported herein will be the subject of future reports.

We adapted the Schooler/Kane15 research criteria for tardive dyskinesia(TD) (at least “moderate” movements in one or more body areas or at least “mild” movements in two or more body areas rated with the AIMS) to identify new-onset TD. We defined possible new-onset EPS as an average increase of > 0.3 across items on the Simpson-Angus scale.

Rater training, reliability and blinding

Clinicians with at least master’s degrees and clinical experience with people with schizophrenia conducted all interviews. Randomization occurred centrally, and study sites followed procedures to maintain blinding. Raters participated in initial training, conducted by Schizophrenia Trials Network staff, for certification and annual re-training to maintain certification.

Data analysis

Paralleling the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) Phase 116 and subsequent analyses of the impact of switching antipsychotic medications using CATIE data17, we used Kaplan-Meier and Cox regression to examine the effect of Staying on a first-generation injectable antipsychotic compared to Switching to RM on time to all-cause treatment discontinuation including covariates of gender and baseline medication, our two pre-specified stratification variables. We applied random regression models to examine secondary outcomes. Independent variables included Group (Stay or Switch), Time (linear and quadratic), and Group by linear and quadratic Time with covariates of gender and baseline medication. We used intent-to-treat models for primary analyses in which a significant Group-by-Time interaction would support the hypothesized treatment effect. Secondarily, we examined two as-treated models, one that completely excluded individuals who discontinued their assigned treatment condition and one in which data from such individuals were excluded only from time of discontinuation of assigned treatment. For participants assigned to Stay, discontinuation from assigned treatment was defined as discontinuing FD or HD or adding one or more additional antipsychotics (addition of oral haloperidol to HD or oral fluphenazine to FD did not count as discontinuation of assigned treatment). For participants assigned to Switch, discontinuation from assigned treatment was defined as discontinuing RM or adding another antipsychotic (addition of oral risperidone or paliperidone did not count as discontinuation of assigned treatment).

Results

Sixty-two individuals were randomized and 53 (29 Stay, 24 Switch) began their assigned treatment. Groups did not differ at baseline on demographics, dosage of first generation injectable, or secondary measures (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographic and other characteristics of the two groups at baseline

| Randomly Assigned to Stay on First Generation Injectable (N=30) |

Randomly Assigned to Switch to Long- Acting Injectable Risperidone Microspheres (N=32) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | chi- square |

df | p | |

| Male Gender | 22 | 73% | 22 | 69% | 0.2 | 1 | .69 |

| Haloperidol Dec | 19 | 63% | 21 | 66% | 0.0 | 1 | .85 |

| Caucasian Race | 11 | 37% | 12 | 38% | 0.0 | 1 | .95 |

| Latino Ethnicity | 4 | 13% | 1 | 3% | 2.2 | 1 | .14 |

| TD Present | 9 | 30% | 13 | 41% | 0.8 | 1 | .39 |

| EPS Present | 8 | 27% | 14 | 44% | 2.0 | 1 | .16 |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t−test | df | P | |

| Age (years) | 47.3 | 9.1 | 48.5 | 12.2 | −0.4 | 60 | .66 |

| Baseline Haloperidol Q4 Week Dosage (n=19 Stay, 18 Switch) | 114.7 | 56.9 | 119.9 | 43.5 | −0.3 | 35 | .78 |

| Baseline Fluphenazine Q2 Week Dosage (n=10 Stay, 8 Switch) | 37.5 | 28.4 | 32.5 | 15.6 | 0.4 | 16 | .66 |

| PANSS Total | 69.9 | 17.9 | 65.4 | 14.0 | 1.1 | 60 | .28 |

| Body Mass Index | 31.3 | 8.7 | 31.0 | 9.8 | 0.1 | 60 | .90 |

| Arizona Sexual Experiences Scale Total | 15.2 | 5.0 | 15.9 | 5.6 | −0.4 | 54 | .66 |

| Prolactin (ng/ml) | 18.5 | 13.8 | 16.7 | 9.8 | 0.5 | 47 | .59 |

Among those assigned to Stay, three (10%) discontinued their assigned treatment within the first six study months (one changed to the oral version of the injectable, one to a different oral antipsychotic, and one began antipsychotic polypharmacy with addition of a different oral agent). Reasons for discontinuation included increased psychiatric symptoms (n=1), EPS concerns (n=1), and participant report that he was informed that he did not have to take the injectable form of the medication (n=1). Among those assigned to Switch, five (21%) discontinued their assigned treatment within the first six study months (all returned to their baseline first-generation injectable); reasons included increased psychiatric symptoms (n=3), hypertension and weight gain (n=1), and participant preference to “feel better” (n=1).

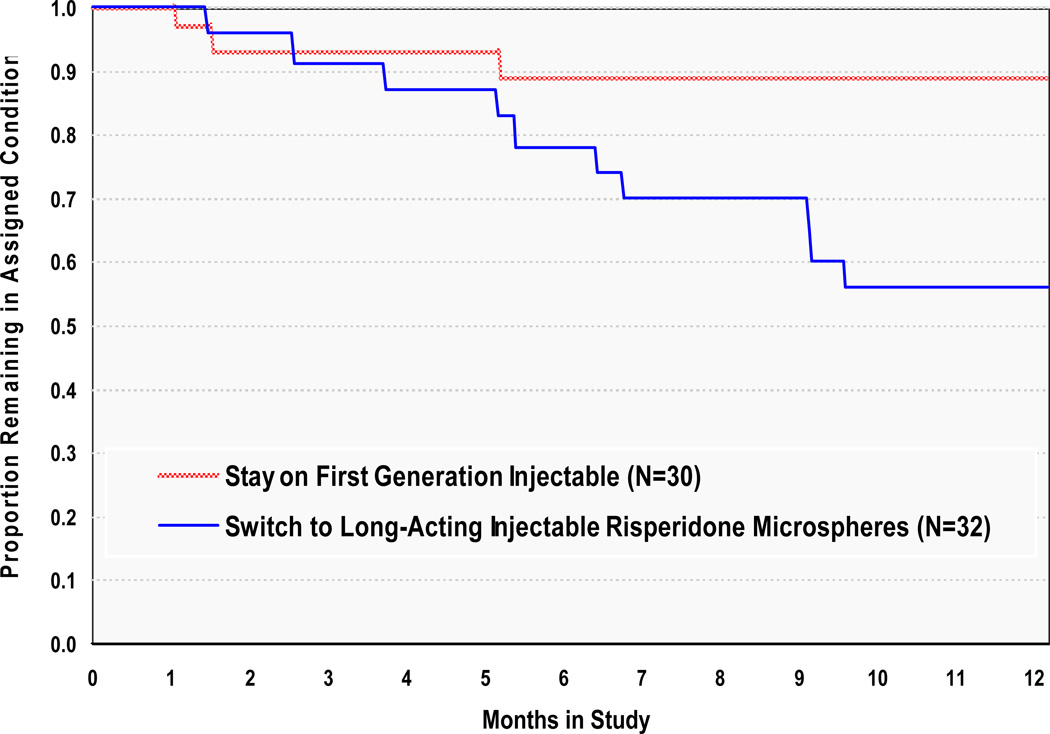

Groups did not differ in time to all-cause treatment discontinuation during the first six study months (Kaplan-Meier Mantel-Cox X2(1) = 0.94 p =.33), where treatment was defined by study protocol. When the additional six months of naturalistic follow up are included, time to all-cause treatment discontinuation was significantly shorter for individuals assigned to Switch to RM than for individuals assigned to Stay on a first-generation injectable antipsychotic (Kaplan-Meier Mantel-Cox X2(1) = 6.00 p =.01; Figure 1), and switching from a first-generation injectable to RM resulted in treatment discontinuation significantly more often (31% discontinued) than did continuation on a first generation injectable antipsychotic (10% discontinued). This difference remained significant after controlling for gender and baseline antipsychotic [FD vs HD] in Cox regression analyses (Wald X2(1)=5.00, p =.03), and neither gender nor baseline decanoate was significantly related to treatment discontinuation at six or 12 months.

FIGURE 1.

Time to Medication Change for Any Reasona

a Groups did not differ at 6 months (Kaplan-Meier Mantel-Cox X2(1) = 0.94 p =.33). However, groups differed significantly at 12 months (Kaplan-Meier Mantel-Cox X2(1)=6.00, p =.01. In Cox Regression analyses, Treatment Group remained significant after controlling for gender and baseline decanoate (Wald X2(1)=5.00, p =.03)).

Stay and Switch groups did not differ significantly on psychopathology over time (Table 2), whether measured as total PANSS, total PANSS positive items, or the 5 factors defined by Marder and colleagues18. Groups did not differ with respect to likelihood of being hospitalized for psychiatric reasons, which was uncommon in both groups. Three (10%) and two (6%) individuals were hospitalized at least once during the six months under study protocol for Stay and Switch groups, respectively, X2(1)=0.3, p=.59, while four (13%) and three (9%) individuals were hospitalized at least once during the full twelve months for Stay and Switch groups, respectively, X2(1)=0.2, p=.62). Nor did groups differ with respect to time to first hospitalization for psychiatric reasons. Neither group experienced hospitalizations for medical reasons during the 6 months under study protocol; three participants assigned to Switch were hospitalized for medical reasons in months 6–12.

TABLE 2.

Intent to Treat Random Regression Analysis of Secondary Outcome Measures for People with Schizophrenia-Spectrum Disorders in a Randomized Controlled Study of Staying on a First Generation Antipsychotic Injectable versus Switching to Long-Acting Injectable Risperidone Microspheres

| PANSS Total Score | 6 Months | ||||

| Predictor | Regression Coefficient | SE | z | p-value | 95% CI |

| Intercept | 65.10 | 4.42 | 14.73 | 0.00 | 56.44 – 73.76 |

| Switch Group | −1.22 | 3.67 | −0.33 | 0.74 | −8.41 – 5.97 |

| Time | −1.44 | 0.35 | −4.13 | 0.00 | −2.13 – (−)0.75 |

| Group by Time | 0.52 | 0.51 | 1.03 | 0.30 | −0.48 – 1.52 |

| Male | 0.03 | 3.99 | 0.01 | 0.99 | −7.79 – 7.85 |

| HD Baseline | 3.44 | 3.78 | 0.91 | 0.36 | −3.97 – 10.85 |

| PANSS Total Score | 12 Months | ||||

| Predictor | Regression Coefficient | SE | z | p-value | 95% CI |

| Intercept | 64.18 | 4.36 | 14.72 | 0.00 | 55.63 – 72.73 |

| Switch Group | −0.56 | 3.62 | −0.15 | 0.88 | −7.66 – 6.54 |

| Time | −0.44 | 0.20 | −2.14 | 0.03 | −0.83 – (−)0.05 |

| Group by Time | 0.04 | 0.31 | 0.11 | 0.91 | −0.57 – 0.65 |

| Male | −0.24 | 3.93 | −0.06 | 0.95 | −7.94 – 7.46 |

| HD Baseline | 2.62 | 3.72 | 0.70 | 0.48 | −4.67 – 9.91 |

| Arizona Sexual Experiences Scale | 6 Months | ||||

| Predictor | Regression Coefficient | SE | z | p-value | 95% CI |

| Intercept | 16.46 | 1.51 | 10.87 | 0.00 | 13.50 – 19.42 |

| Switch Group | 0.82 | 1.26 | 0.65 | 0.52 | −1.65 – 3.29 |

| Time | −0.06 | 0.14 | −0.46 | 0.65 | −0.33 – 0.21 |

| Group by Time | 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.80 | −0.34 – 0.44 |

| Male | −2.10 | 1.37 | −1.53 | 0.13 | −4.79 – 0.59 |

| HD Baseline | 0.75 | 1.33 | 0.57 | 0.57 | −1.86 – 3.36 |

| Arizona Sexual Experiences Scale | 12 Months | ||||

| Predictor | Regression Coefficient | SE | z | p-value | 95% CI |

| Intercept | 16.16 | 1.52 | 10.61 | 0.00 | 13.18 – 19.14 |

| Switch Group | 0.94 | 1.26 | 0.75 | 0.45 | −1.53 – 3.41 |

| Time | 0.08 | 0.07 | 1.05 | 0.29 | −0.06 – 0.22 |

| Group by Time | − 0.07 | 0.12 | −0.64 | 0.53 | −0.31 – 0.17 |

| Male | −2.07 | 1.38 | −1.50 | 0.13 | −4.77 – 0.63 |

| HD Baseline | 0.82 | 1.34 | 0.61 | 0.54 | −1.81 – 3.45 |

| Body Mass Index – Change from Baseline | 6 Months | ||||

| Predictor | Regression Coefficient | SE | z | p-value | 95% CI |

| Intercept | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.75 | 0.45 | −0.21 – 0.49 |

| Switch Group | −0.08 | 0.15 | −0.54 | 0.59 | −0.37 – 0.21 |

| Time | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.85 | 0.40 | −0.07 – 0.17 |

| Group by Time | 0.23 | 0.09 | 2.67 | 0.01 | −0.05 – 0.41 |

| Male | −0.22 | 0.16 | −1.36 | 0.17 | −0.53 – 0.09 |

| HD Baseline | 0.24 | 0.15 | 1.54 | 0.12 | −0.05 – 0.53 |

| Body Mass Index – Change from Baseline | 12 Months | ||||

| Predictor | Regression Coefficient | SE | z | p-value | 95% CI |

| Intercept | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.68 | 0.50 | −0.26 – 0.56 |

| Switch Group | −0.08 | 0.18 | −0.46 | 0.65 | −0.43 – 0.27 |

| Time | 0.08 | 0.05 | 1.41 | 0.16 | −0.02 – 0.18 |

| Time2 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −2.16 | 0.03 | −0.01– (−)0.01 |

| Group by Time | 0.25 | 0.08 | 3.13 | 0.00 | 0.09 – 0.41 |

| Group by Time2 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −1.80 | 0.07 | −0.03 – 0.01 |

| Male | −0.28 | 0.19 | −1.47 | 0.14 | −0.65 – 0.09 |

| HD Baseline | 0.30 | 0.18 | 1.69 | 0.09 | −0.05 – 0.65 |

| Prolactin (ng/ml) | 6 Months | ||||

| Predictor | Regression Coefficient | SE | z | p-value | 95% CI |

| Intercept | 22.85 | 3.40 | 6.71 | 0.00 | 16.19 – 29.51 |

| Switch Group | 0.30 | 2.91 | 0.10 | 0.92 | −5.40 – 6.00 |

| Time | −0.37 | 0.37 | −1.01 | 0.31 | −1.10 – 0.36 |

| Group by Time | 1.32 | 0.53 | 2.48 | 0.01 | 0.28 – 2.36 |

| Male | −9.74 | 2.99 | −3.25 | 0.00 | −15.6 – (−)3.88 |

| HD Baseline | 1.81 | 2.79 | 0.65 | 0.52 | −3.66 – 7.28 |

| Prolactin (ng/ml) | 12 Months | ||||

| Predictor | Regression Coefficient | SE | z | p-value | 95% CI |

| Intercept | 20.36 | 3.10 | 6.56 | 0.00 | 14.28 – 26.44 |

| Switch Group | 0.15 | 3.12 | 0.05 | 0.96 | −5.97 – 6.27 |

| Time | −0.38 | 0.45 | −0.85 | 0.40 | −1.26 – 0.50 |

| Time2 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.62 | 0.54 | −0.04 – 0.08 |

| Group by Time | 1.81 | 0.71 | 2.57 | 0.01 | 0.42 – 3.20 |

| Group by Time2 | −0.12 | 0.05 | −2.31 | 0.02 | −0.22– (−)0.02 |

| Male | −6.40 | 2.38 | −2.69 | 0.01 | −11.1 – (−)1.74 |

| HD Baseline | 1.64 | 2.20 | 0.74 | 0.46 | −2.67 – 5.95 |

Groups did not differ with respect to incidence of sexual side effects (Table 2), new-onset EPS within 6 months (n=2 of 21 (10%) of those without EPS at baseline who were assigned to Stay and n=2 of 13 (15%) of those without EPS at baseline who were assigned to Switch, X2(1)=0.3, p=.61) or within 12 months (n=3 of 21 (14%) of those without EPS at baseline who were assigned to Stay and n=2 of 13 ( 15%) of those without EPS at baseline who were assigned to Switch, X2(1)=0.0, p=.93), or new-onset TD within 6 months (n=5 of 21 (24%) of those without TD at baseline who were assigned to Stay and n=6 of 14 (43%) of those without TD at baseline who were assigned to Switch, X2(1)=1.4, p=.23) or 12 months (n=7 of 21 (33%) of those without TD at baseline who were assigned to Stay and n=7 of 14 (50%) of those without TD at baseline who were assigned to Switch, X2(1)=1.0, p=.32).

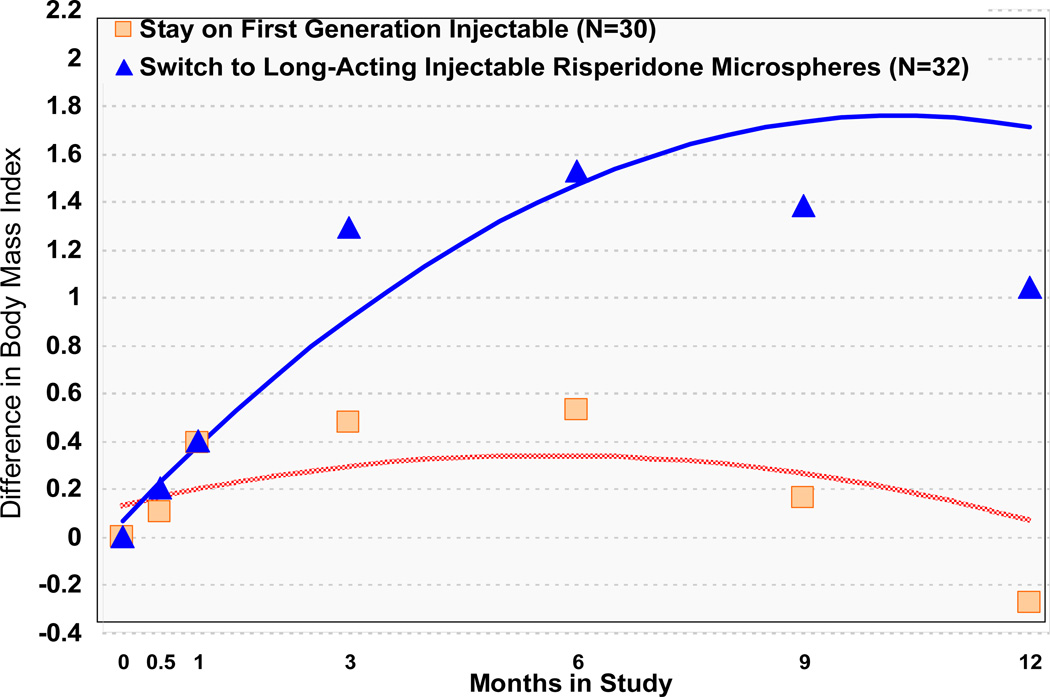

Those assigned to RM significantly increased their body mass index (BMI) compared to those assigned to Stay. (Table 2; Figure 2). On average, individuals assigned to Switch gained 1.5 BMI (SD = 2.2 BMI, N=22) at six months and 1.0 BMI (SD=2.0, N=17) at 12 months, and individuals assigned to Stay gained or lost little (0.5 BMI (SD = 1.3 BMI, N=24) at 6 months and −0.3 BMI (SD=1.7, N=24) at 12 months).

FIGURE 2.

Difference in Body Mass Index Through Timea

a Significant Group by Time interaction (z = 2.67, p = .01 at 6 months and z = 3.13, p = .00 at 12 months).

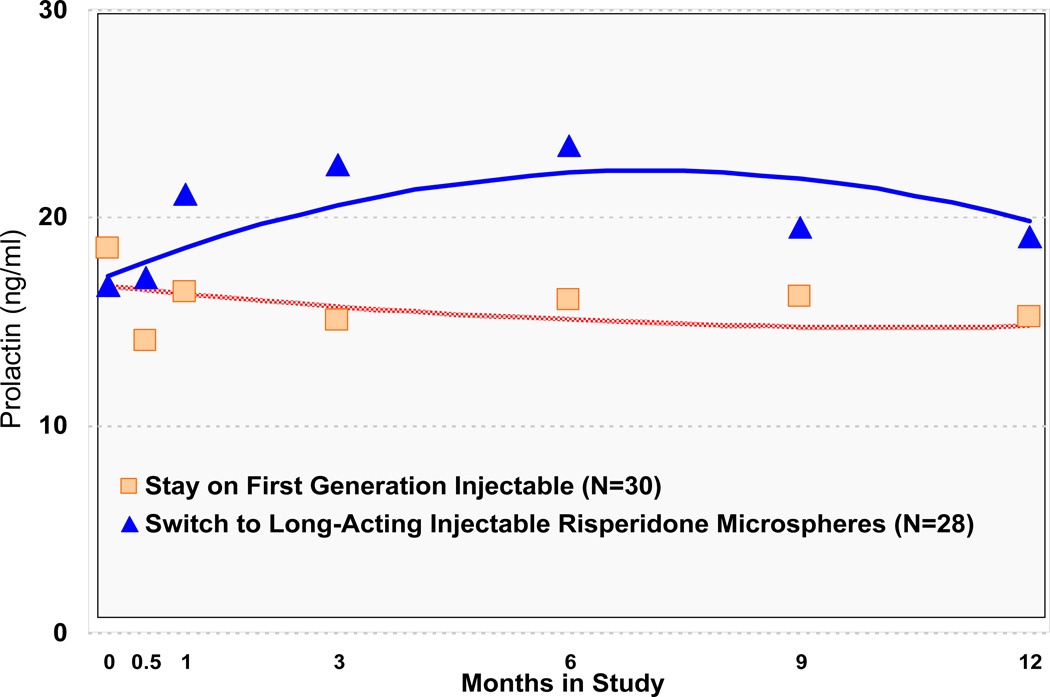

RM also resulted in a significant increase in prolactin levels compared to those assigned to Stay on a first generation injectable, with mean prolactin levels for those assigned to RM rising above the threshold considered significantly elevated above normal, after one month of treatment (Table 2; Figure 3). Additionally, men had significantly lower prolactin levels than women (Table 2; Online Supplement). Each of the secondary (as-treated) models was consistent with findings from primary intent-to-treat analyses.

FIGURE 3.

Prolactin Through Timea

a Significant Group by Time interaction (z = 2.48, p = .01 at 6 months and z = 2.57, p =.01 for Group by Time and z= −2.31, p = .02 for Group by Time2 at 12 months).

Of the 24 individuals randomized to Switch to RM who began their assigned treatment, 17 (71%) began with 25 mg., 6 (25%) with 37.5 mg., and 1 (4%) with 50 mg. of RM. Fourteen individuals (12 on 25 m.g., 1 on 37.5 m.g., and 1 on 50 m.g. RM) remained at their starting dosage for the duration of their RM trial. Of the remaining 10, 8 (80%) experienced a dosage increase (3 from 25 m.g. to 50 m.g. RM, 3 from 37.5 m.g. to 50 m.g. RM, and 2 from 25 m.g. to 37.5 m.g. RM), 1 (10%) experienced a dosage decrease (from 37.5 m.g. to 25 m.g. RM), and 1 (10%) experienced both an increase and decrease (from 37.5 m.g. to 50 m.g. to 37.5 m.g. RM).

Discussion

As in previous studies, changing antipsychotics was more likely to result in treatment discontinuation than staying on the original antipsychotic regimen17,19. Individuals randomly assigned to Switch to long-acting injectable RM were more likely to discontinue treatment within one year than were those who continued on their baseline first-generation injectable antipsychotic medication. The extent to which this increased rate of discontinuation for Switchers was due to RM being less well tolerated than a first generation injectable antipsychotic medication versus the bias associated with staying on a medication already known to be tolerated is unclear. Answering that question would require comparing outcomes for individuals switched to a first generation injectable antipsychotic medication with individuals switched to RM. A recently published retrospective study compared 726 individuals initiated on RM to 1484 who were initiated on a first generation injectable while hospitalized20. The authors reported that those initiated on RM were less likely to be discharged on that same medication and offered, as one possible explanation, that RM, in the dosages commonly used, may not be as efficacious as first generation injectable medications20.

Similar to earlier studies8, we found that individuals in this small trial could switch from conventional depot antipsychotics to RM without compromising clinical stability. Adverse effects often are limiting factors in a medication’s use and acceptability. We did not find significant differences between the medications studied with respect to new onset EPS, TD or sexual side events. While individuals with some side effects were eligible to participate in the study, those with side effects so bothersome that a change in medication was indicated were not eligible to participate. Hence, it may be that the study excluded those most vulnerable to developing EPS or TD. We did find significant differences in BMI and prolactin that favored the FD and HD over RM.

Because this was an open label study, patients (and their prescribers) in the “Switch” condition may have been more inclined to attribute changes in feelings/symptoms/side effects to the medication than were those in the “Stay” condition, who may have experienced similar changes as part of normal variations in their illness. Because the study excluded individuals who could not tolerate remaining on their baseline treatment, those assigned to “Stay” may have been advantaged with respect to measures of discontinuation. Treatment discontinuation may also be subject to expectation bias in an open label study. Hence, time to all cause discontinuation may be a more appropriate measure for double blind trials where prescriber and patient expectation effects are controlled. In contrast, ratings of EPS and TD were conducted by blinded raters and measures of weight and prolactin levels were based on objective measures and unlikely to be influenced by knowledge of the treatment assignment.

A limitation of the study is its modest sample size and limited statistical power. Additionally, our study was both too small and too short to allow evaluation of the long-term cost implications of the switch from first generation injectables to RM. Nevertheless, we were able to detect a significant difference in the primary outcome measure at 12 months and in important secondary measures. For other important secondary measures, including psychiatric symptoms, hospitalizations, new-onset EPS and new-onset TD, we found no trends that would suggest a large difference between treatment groups. A larger and longer study, however, might reveal differences that are clinically and statistically significant. Additionally, the small sample size precluded subgroup analyses that may have identified groups that did better on one of the treatments.

Given the aim of this study-- to determine the relative risks and benefits of changing from HD or FD to RM-- generalizability of the findings are necessarily limited to people who are already receiving long-acting injectable antipsychotics. Those who are prescribed long-acting injectable medications likely differ from individuals who are prescribed oral therapy. Hence, these findings do not inform the relative risks and benefits of switching from oral antipsychotics to RM.

Despite these limitations, this study adds to the literature that suggests, for individuals who have responded somewhat to their current antipsychotic but who still have residual symptoms, switching to a different antipsychotic is unlikely to improve symptom control and new side effects are likely. Given this, physicians should review with patients the side effects associated with various antipsychotics as an important component of shared decision making.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. McEvoy received honoraria from Eli Lilly & Co., Janssen Pharmaceutica, and Pfizer and provided consulting services for Eli Lilly & Co., Organon, and Solvay. Dr. Schooler received honoraria from DaiNippon Sumitomo. Eli Lilly & Co, Hoffman LaRoche, Johnson and Johnson, Merck, Pfizer, , and received grants from Astra Zeneca, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Eli Lilly & Co, OrthMcNeil Janssen and Pfizer. The authors would like to thank Linda Frisman, Robert Gibbons, Philip Harvey, John Kane and Peter Weiden for their suggestions during the design and implementation phases of this study and Jennifer Manuel and Sue Marcus for help with the analyses. We thank Patrick Corrigan, Psy.D., Lisa Dixon, M.D., Andrew Leon, Ph.D., Stephen Marder, M.D.(Chair), Delbert Robinson, M. D., Yvette Sangster, and Larry Siever, M.D. for serving on the study’s Data Safety Monitoring Board.

Research was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grant numbers MH71663 (N. Covell, PI) and MH59312 (S. Essock, PI) and by NIMH contract number MH900001 (S. Stroup, PI).

Participating Schizophrenia Trial Network Sites included: L. Adler, Clinical Insights, Glen Burnie, Md.; M. Byerly, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, Dallas; S. Caroff, Behavioral Health Service, Philadelphia; J. Csernansky, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis; C. D’Souza, Connecticut Mental Health Center, New Haven; C. Jackson, James J. Peters VA Medical Center, Bronx; T. Manschreck, Corrigan Mental Health Center, Fall River, Mass.; J. McEvoy, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C.; A. Miller, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio; H. Nasrallah, University of Cincinnati Medical Center, Cincinnati; S. Olson, University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis; J. Patel, University of Massachusetts Health Care, Worcester; B. Saltz, Mental Health Advocates, Boca Raton, Fla.; R.M. Steinbook, University of Miami School of Medicine, Miami; and A. Tapp, Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System, Tacoma, Wash. Additional sites included 5 sites in the public mental health system in CT (K. Marcus, Medical Director).

Footnotes

Portions previously presented at the 49th annual meeting of the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit of the National Institute of Mental Health, Hollywood, FL, June 29–July 2, 2009

Disclosures

Drs. Essock, Stroup, and Covell report no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Kelly DL, et al. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychopharmacological treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:71–93. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kane JM, Eerdekens M, Lindenmayer JP, et al. Long-acting injectable risperidone: efficacy and safety of the first long-acting atypical antipsychotic. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1125–1132. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chue P, Eerdekens M, Augustyns I, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of long-acting risperidone and risperidone oral tablets. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;15:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keks NA, Ingham M, Khan A, et al. Long-acting injectable risperidone v. olanzapine tablets for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Randomised, controlled, open-label study. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:131–139. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.017020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindenmayer JP, Khan A, Eerdekens M, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of long-acting injectable risperidone in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;17:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaebel W, Schreiner A, Bergmans P, et al. Relapse prevention in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder with risperidone long-acting injectable vs quetiapine: results of a long-term, open-label, randomized clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;35:2367–2377. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenheck RA, Krystal JH, Lew R, et al. Long-acting risperidone and oral antipsychotics in unstable schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:842–851. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1005987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turner M, Eerdekens E, Jacko M, et al. Long-acting injectable risperidone: safety and efficacy in stable patients switched from conventional depot antipsychotics. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;19:241–249. doi: 10.1097/01.yic.0000133500.92025.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Biometrics Research Department. New York: Psychiatric Institute; 1995. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders - patient edition (SCID-I/P. Version 2.0) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The Positive and Negative Syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schooler NR. Evaluation of drug-related movement disorders in the aged. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:603–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simpson GM, Angus JWS. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1970;212:11–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1970.tb02066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGahuey CA, Gelenberg AJ, Laukes CA, et al. The Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (ASEX): reliability and validity. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:25–40. doi: 10.1080/009262300278623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiden PJ, Miller A. Which side effects really matter? Screening for common and distressing side effects of antipsychotic medications. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2001;7:41–47. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200101000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schooler NR, Kane JM. Research diagnoses for tardive dyskinesia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39:486–487. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290040080014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1209–1223. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Essock SM, Covell NH, Davis SM, et al. Effectiveness of Switching Antipsychotic Medications. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:2090–2095. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.12.2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marder SR, Davis JM, Chouinard G. The effects of risperidone on the five dimentions of schizophrenia derived by factor analysis: Combined results of the North American trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:538–546. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Essock SM, Schooler NR, Stroup TS, et al. Effectiveness of Switching from Antipsychotic Polypharmacy to Monotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10060908. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Citrome L, Jaffe A, Levine J. Treatment of schizophrenia with depot preparations of fluphenazine, haloperidol, and risperidone among inpatients at state-operated psychiatric facilities. Schizophr Res. 2010;119:153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.02.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.