Abstract

The rarity of neuroendocrine tumors (NET) has contributed to a paucity of large epidemiologic studies of patients with this condition. We characterized presenting symptoms and clinical outcomes in a prospective database of over 900 patients with NET. We used data from patient questionnaires and the medical record to characterize presenting symptoms, disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS). The majority of patients in this database had gastroenteropancreatic NET. The median duration of patient-reported symptoms prior to diagnosis was 3.4 months; 19.5% reported durations from 1 to 5 years, 2.5% from 5 to 10 years and 2% greater than 10 years. The median DFS among patients with resected small bowel NET or pancreatic NET was 5.8 yrs and 4.1 years, respectively. After correcting for left truncation bias, the median OS was 7.9 yrs for advanced small bowel NET and 3.9 yrs for advanced pancreatic NET. Chromogranin A (CGA) above twice the upper limit of normal was associated with shorter survival times (HR 2.8 (1.9, 4.0) p<0.001) patients with metastatic disease, regardless of tumor subtype. Our data suggest that while most NET patients are diagnosed soon after symptom onset, prolonged symptom duration prior to diagnosis is a prominent feature of this disease. Though limited to observations from a large referral center, our observations confirm the prognostic value of CGA, and suggest that median survival durations may be shorter than reported in other institutional databases.

Keywords: neuroendocrine tumors, disease-free survival, overall survival, chromogranin A

Introduction

A low incidence of neuroendocrine tumors (NET) has presented challenges to completing large epidemiologic studies characterizing the clinical presentation and course of patients with this condition (Yao et al. 2008). Data on the type and duration of symptoms prior to the diagnosis of NET may lead to earlier diagnosis (Modlin et al. 2008). Additionally, a clearer understanding of the natural history and prognostic factors for patients with NET may facilitate the development of treatment guidelines and the design of clinical trials (Modlin et al. 2008; Kulke et al. 2011).

While symptoms of hormone hypersecretion are a hallmark of NET, only a minority of patients have been reported to exhibit such symptoms at the time of their initial presentation (Pape et al. 2008a; Pape et al. 2008b; Yao et al. 2008; Zerbi et al. 2010; Jann et al. 2011). Presenting signs and symptoms for patients with symptoms of hormone hypersecretion are thought to occur, on average, for many years prior to diagnosis (Vinik et al. 2009; Vinik et al. 2010). Few studies, however, have evaluated the time to presenting signs and symptoms of NET patients.

Clinical outcomes of patients with NET have been assessed in population-based cohorts and in institutional databases but data on disease free survival estimates in these studies are limited (Pape et al. 2008a; Pape et al. 2008b; Yao et al. 2008; Zerbi et al. 2010; Jann et al. 2011). Additionally, survival estimates for patients with advanced disease are highly variable. In an analysis of over 35,000 NET cases in the SEER database, the median survival duration was 2 years for patients with metastatic pancreatic NET (panNET) and 4.7 years for patients with metastatic small bowel NET tumors (Yao et al. 2008). Institutional studies, on the other hand, have reported median survival durations of 5.8–7.4 years for patients with advanced panNET (Pape et al. 2008a; Strosberg et al. 2008; Strosberg et al. 2011), and over 10 years for patients with metastatic small bowel NET (Pape et al. 2008a; Jann et al. 2011).

Tumor stage, tumor grade, and site of tumor origin are well established prognostic factors for patients with NETs (Solcia et al. 2000; Rindi et al. 2006; Pape et al. 2008b; Strosberg et al. 2011). However, the role of biochemical markers such as chromogranin A (CGA) or alkaline phosphatase (ALP) in assessing prognosis remains controversial. While several studies have reported associations between elevated CGA increased disease burden, and shorter survival (Janson et al. 1997; Stivanello et al. 2001; Kolby et al. 2004; Nehar et al. 2004; Ekeblad et al. 2008; Nikou et al. 2008; Korse et al. 2009; Yao et al. 2011; Yao et al. 2012), CGA can be elevated in non-malignant conditions and associations with high prognosis have not been uniformly observed (Lawrence et al. 2011a). Elevated ALP has been reported to be associated with shorter survival in patients with advanced NET by our group and by others (Clancy et al. 2006; Kwekkeboom et al. 2011).

To better define and compare the clinical presentation and subsequent course of patients with small bowel, pancreatic and other NETs, we used data from a prospectively collected institutional database, based in a gastrointestinal oncology unit, comprising over 900 patients with NET. We evaluated patient-reported presenting symptoms, disease-free and overall survival, together with potential prognostic factors.

Materials and methods

Assessment of presenting symptoms, baseline demographics, and clinical outcomes

Patients with a confirmed diagnosis of NET (excluding small cell lung cancer) were recruited to an IRB-approved study in the gastrointestinal clinic at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) beginning in July 2003. Consent had been obtained from each patient after a full explanation of the purpose and nature of all procedures used. Data on presenting signs and symptoms was obtained from patient questionnaires. Baseline clinical and demographic information was derived from both questionnaires and from the medical record. All pathology was reviewed in the pathology department at Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center at the time of patient consultation (2003–2010). For the purposes of this project, each case was assigned a tumor grade (low, intermediate, or high) best corresponding to the World Health Organization (WHO) 2010 classification: G1, G2 and G3 (Klimstra et al. 2010; Rindi et al. 2010). Assignments were based on available information in the pathology report on tumor grade, tumor differentiation, mitotic rate and the Ki-67 labeling index; tissue blocks were not re-reviewed due to inconsistent availability. Serum ALP and serum CGA values were extracted from clinical laboratory test reports. Testing for CGA was performed at either Quest Diagnostics or Mayo Medical Research clinical labs.

Variables associated with symptom duration prior to diagnosis were evaluated by a multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis adjusting for age and stage at diagnosis, gender, tumor origin, and tumor grade.

Assessment of Disease-Free Survival and Overall Survival

Patients were categorized as having either small bowel NET, panNET or other NET. Survival data was obtained from the medical record, or, if not available, from the Social Security Death Index. In patients without distant metastases at the time of diagnosis, disease free survival (DFS) was calculated from the date of primary tumor resection to the date of the first outcome in the following order: local recurrence, development of distant metastases, death from any cause, or to the censoring date which was date of the last patient visit at the DFCI. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of diagnosis of metastatic disease to the date of death or to the date of censoring (October 21, 2010). Median times for disease free survival and overall survival were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, comparisons assessed by the log-rank test. Left truncation bias10,26 can lead to overestimates of standard survival distributions caused by the variable times between initial or metastatic diagnosis and entry into the study at consent date. To account for this, overall survival was also estimated using a modified Kaplan-Meier method using SAS macro survlt; http://mayoresearch.mayo.edu/mayo/research/biostat/sasmacros.cfm (Shariff et al. 2008; Cain et al. 2011; Strosberg et al. 2011). Median follow-up time was computed among censored observations only, adjusting for left truncation by using the baseline survival curve of a Cox proportional hazards model with no covariates, accounting for entry time by consent date.

Assessment of Prognostic Factors

We assessed potential prognostic factors using patients with complete information on age, gender, tumor stage (metastatic or localized at initial diagnosis), tumor subtype (small bowel NET, panNET, other NET), and tumor grade (low, intermediate, high and unknown). We used a multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analyses accounting for left truncation with entry at the consent date. For analysis of serum CGA and ALP, we included patients with an available measurement closest to the time of metastatic diagnosis. CGA and ALP were categorized as binary categorical variables (elevated/non-elevated above the upper limit of normal). All statistical testing was done at the two-sided 0.05 alpha level, using SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Patient characteristics

937 patients were enrolled in the prospective database between July 2003 and October 2010 (Table 1). Consent rates for the study exceeded 95%. Dates of initial diagnosis ranged from June 1958 to February 2010. The median patient age was 54 years; 411 patients (44%) had localized disease and 526 (56%) had distant metastases at the time of their initial diagnosis. Of those with localized disease, all but 24 underwent surgical resection. In light of the diversity of NET, we focused our subsequent analyses on the two most common subgroups, small bowel NET, and panNET which comprised 38% and 23% of the cohort, respectively. Other NET represented 39% of the cohort, and comprised a diverse group of NET arising in other sites, including NETs of unknown primary site (11%), bronchi (9%), appendix (5%), stomach (3%), and of other origins (11%). Nearly all (97%) small bowel NET tumors were well differentiated; 86% of panNET and 78% of other NET had well differentiated histology.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the patient population

| All patients (N=937)a | Small bowel NET (N=358) | Pancreatic NET (N=215) | Other NET (N=364) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median Age at Diagnosis (range) | 54 yrs (13.2–86.4) | 57 yrs (26.6–86.4) | 53 yrs (13–85.8) | 51 yrs (14.3–86.2) |

| Gender (M,F) | 435 (46.4%), 502 (53.6%) | 178 (50%), 180 (50%) | 109 (50.7%), 106 (49.3%) | 148 (40.7%), 216 (59.3%) |

| Ethnicity (Caucasian, African-American, Other) | 878 (93%), 24 (3%), 35(4%) | 337(94%), 12 (3%), 9 (3%) | 204 (95%), 2 (1%), 9 (4%) | 337 (93%), 10 (2%), 17(6%) |

| Tumor Grade | ||||

| Low | 815 (86.97%) | 347 (96.9%) | 184 (85.6%) | 284 (78%) |

| Intermediate | 56 (5.98%) | 6 (1.7%) | 16 (7.4%) | 34 (9.3%) |

| High | 34 (3.63%) | 1 (0.3%) | 11 (5.12%) | 22 (6%) |

| Unknown | 32 (3.42%) | 4 (1.1%) | 4 (1.9%) | 24 (6.6%) |

| Stage | ||||

| Localized at Diagnosis | 411 | 129 | 77 | 205 |

| LNb + | 172 (49%) | 98 (82.3%) | 31 (51%) | 43 (25%) |

| LNb − | 182 (51%) | 21 (17.6%) | 30 (49%) | 131 (75%) |

| Unknown | 57 | 10 | 16 | 31 |

| Metastatic c | 677 | 272 | 182 | 223 |

| At Diagnosis | 526 | 229 | 138 | 159 |

| After F/U | 151 | 43 | 44 | 64 |

Total cases include small bowel NET (38%), pancreatic NET (23%) and other NET (unknown primary site (11%), bronchi (9%), appendix (5%), stomach (3%), and of other origins (11%).

Resected patients with lymph node status

Patients with distant metastases at diagnosis or during follow up

Symptoms at initial presentation

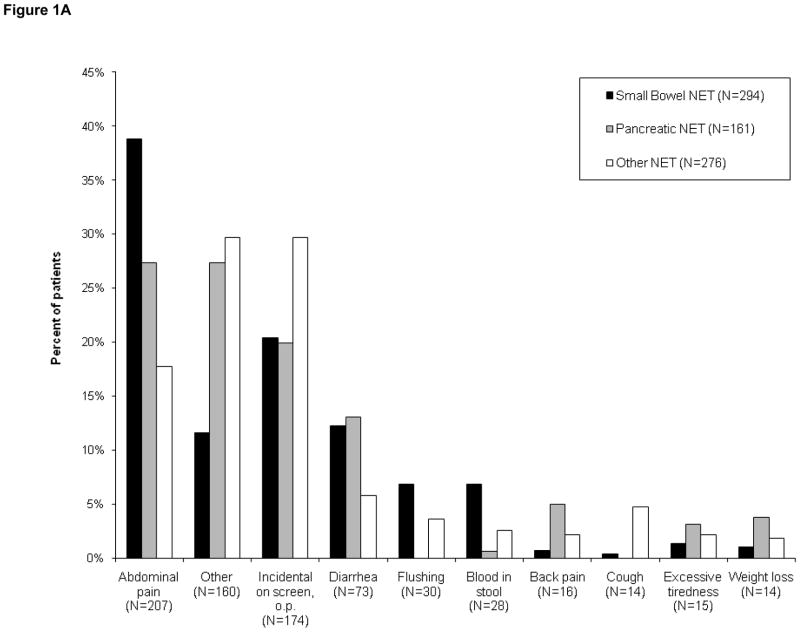

731 (78.0%) patients completed questionnaires characterizing symptoms leading to their diagnosis. Abdominal discomfort was the most common presenting symptom for patients with gastrointestinal tumor (Fig. 1A). 24% of the patients were diagnosed either during screening procedures or procedures performed for other reasons (20% for panNET, 20% for small bowel NET, 30% for other NET). Among patients with small bowel NET, 12% presented with symptoms of diarrhea, and 7% reported symptoms of flushing.

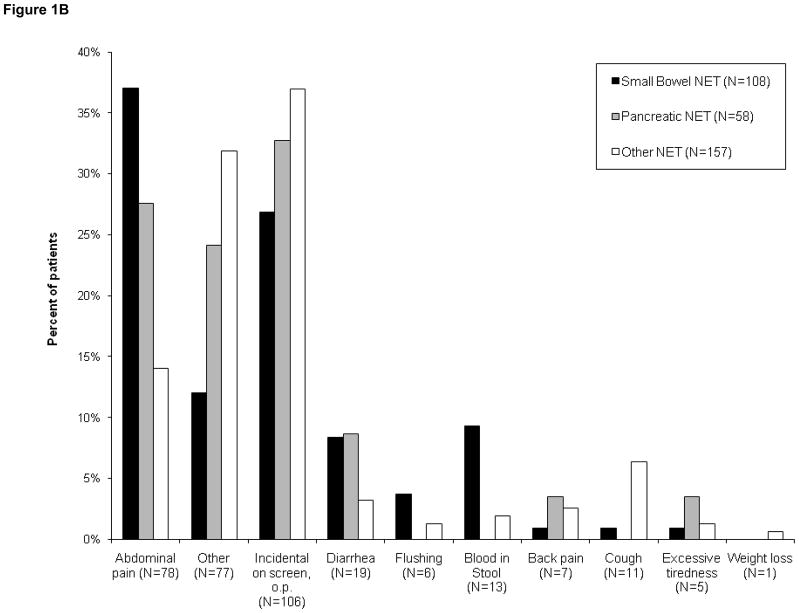

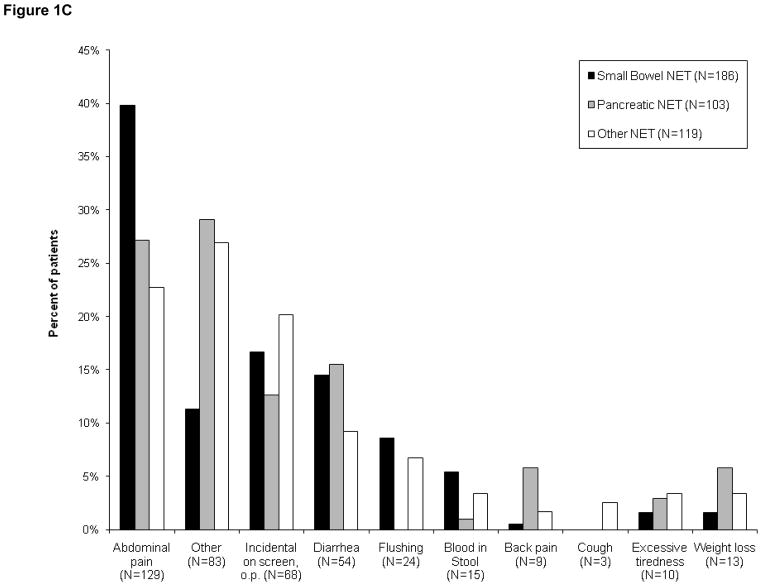

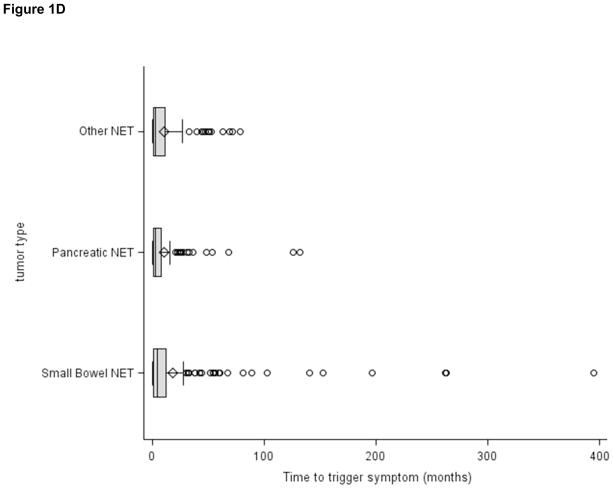

Figure 1.

Figures 1(A–C): Patient-reported symptoms at time of diagnosis

Figure 1A. Patient-reported symptoms, entire cohort (N=731)

Figure 1B. Symptoms reported by patients presenting with localized disease (N=323)

Figure 1C. Symptoms reported by patients with metastatic disease (N=408)

Figure 1D. Patient-reported time from initial onset of symptoms to diagnosis (N=393)

The reported presenting symptoms differed to some extent between patients with localized or metastatic disease (Figs. 1B and 1C). While abdominal pain was a common presenting symptom in both subsets, incidental diagnosis was more common among patients with localized disease than in those whose disease was metastatic (33% vs 17%). In contrast, symptoms of flushing or diarrhea were less common in patients with localized disease than in those with metastases at diagnosis. Flushing was reported in 2% of patients with localized disease versus 6% metastatic. Diarrhea was reported in 6% of patients with localized disease versus 13% metastatic.

To estimate the time from onset of symptoms to diagnosis, we limited our analysis to the 393 patients who reported a date of initial symptoms prior to diagnosis and excluded patients who reported no symptoms or who were incidentally diagnosed. Median time from onset of symptoms to diagnosis was 3.4 months for the cohort overall, and 4.3, 2.9 and 2.9 months for patients with small bowel NET, panNET, and other NET respectively. However, some patients reported prolonged symptom duration prior to diagnosis; in the cohort overall, 19.5% reported durations from 1 to 5 years, 2.5% from 5 to 10 years and 2% greater than 10 years. A multivariate regression model showed that only high tumor grade was significantly associated with a shorter time from onset of symptoms to diagnosis aHR 2.5 (1.6, 4.0), p<0.001.

To address the possible effect of recall bias we also evaluated presenting symptoms in the 213 patients that consented to the study within 6 months of their diagnosis. While the calculated time durations were slightly shorter that for the cohort overall, we found a similar pattern in that the median time from initial symptoms to diagnosis was relatively short (2.7 months) while 14.5% reported durations from 1 to 5 years, 1.9% from 5 to 10 years and 1.4% greater than 10 years.

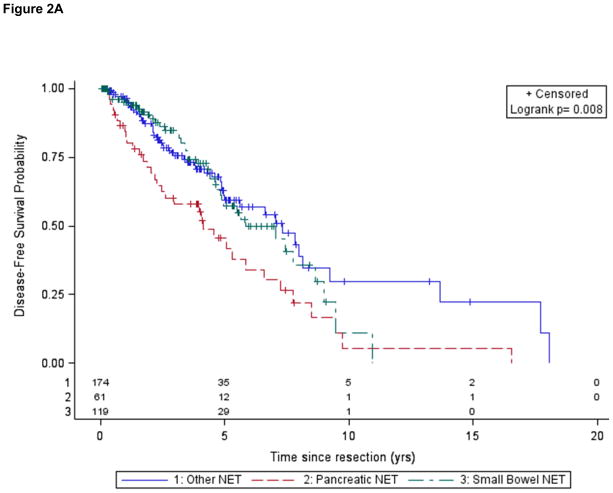

Disease Free Survival

411 patients without distant metastases underwent resection of their primary tumor; of these, 354 had known lymph node status and were used to estimate DFS. Of these 354 patients, 124 of these patients experienced a recurrence: 102 prior to study enrollment, 22 after study enrollment. Five year DFS rates were 56% in the cohort overall; 57% in small bowel NET, and 42% in panNET. The median DFS was 5.8 years in the cohort overall: 5.8 yrs for patients with small bowel NET and 4.1 yrs for those with panNET (Table 2; Fig. 2A).

Table 2.

Prognostic factors for disease free survival (resected patients; n= 354)

| Variable | Adjusted HRa (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Older Age | 1.0 (0.9, 1.0), p=0.07 |

| Male Gender | 1.2 (0.9, 1.8), p=0.3 |

| Lymph Node involvement | 1.9 (1.3, 3.0), p=0.003 |

| Tumor Grade | |

| Intermediate | 3.1 (1.8, 5.3), p<0.001 |

| High | 5.5 (1.6, 18.2), p=0.006 |

| Unknown | 1.4 (0.3, 6.0), p=0.6 |

| Primary Siteb | |

| panNET vs Other | 1.5 (0.9, 2.3), p=0.1 |

| SBN vs Other | 0.9 (0.5, 1.5), p=0.6 |

| panNET vs SBN | 1.7 (1.0, 2.8), p=0.04 |

Hazard Ratios adjusted for age at diagnosis, gender, indicator variables of tumor type, tumor grade and lymph node status

panNET = pancreatic NET, SBN = small bowel NET, Other = other NET

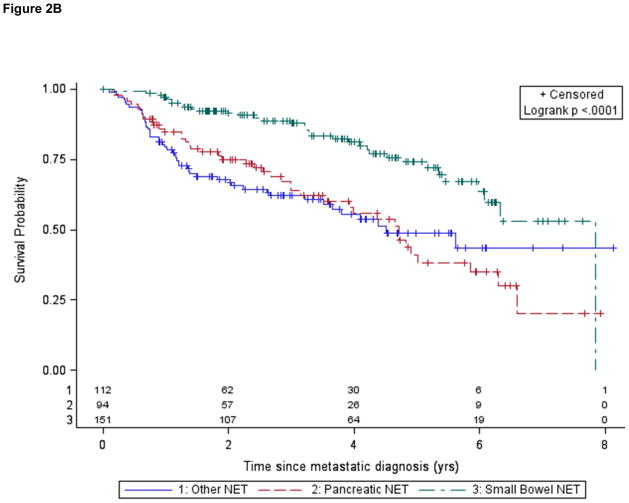

Figure 2.

Figure 2A. Disease-free survival following resection according to tumor site of origin

Figure 2B. Overall survival for patients with metastatic disease according to tumor subtype (analysis limited to patients diagnosed within 1 year of study)

Lymph node involvement was associated with shorter DFS in small bowel NET but not in panNET. Patients with small bowel NET also had a higher incidence of positive lymph nodes (82%) than other subgroups. Among patients with resected small bowel NET and no lymph node involvement, only 2 of 21 experienced a recurrence, and the median DFS was not reached. Among patients with resected small bowel NET and lymph node involvement, 37 of 98 experienced a recurrence; these patients had a median DFS of 5.5 yrs.

Overall survival

There were 270 deaths during the course of the study, the median follow up time was 4.2 years, and the mean follow up time was 6 years (range of 6.4 months to 52.4 yrs). Due to a low number of deaths in resected patients, we were not able to accurately estimate overall survival for this cohort, so we limited our survival estimates to patients with unresectable, metastatic disease. Our initial estimated median overall survival duration for metastatic patients was 8.0 yrs for the cohort overall; 10.1 yrs for small bowel NET, 5.9 yrs for panNET and 5.9 yrs for other NET. Previous studies have noted that “immortal time bias” or “left truncation bias” may artificially inflate survival estimates due to the inclusion of patients who have been diagnosed many years prior to evaluation at a referring institution, and therefore have longer than average survival (Shariff et al. 2008; Strosberg et al. 2011). Using a modified Kaplan-Meier analysis that corrects for left truncation bias, we estimated the median survival duration to be 5.2 yrs for the cohort overall: 7.9 yrs for small bowel NET, 3.9 yrs for panNET, and 3.7 yrs for other NET (Table 2). We obtained similar results when we restricted our analysis to patients diagnosed within 1 year (Fig. 2B), another approach that would mitigate left truncation bias. Intermediate or high tumor grade, older age, and pancreatic primary site were independent adverse prognostic factors in patients with advanced NET.

We assessed associations between the biomarkers CGA or ALP and survival from the date each test was obtained. We used any available test results closest to the date of diagnosis of metastatic disease which was within 2–3 months on average, with a range of 0 to 14 yrs for both markers. CGA above the upper limit of normal was associated with shorter survival in patients with metastatic small bowel NET or non-panNET; however using this cutoff we did not observe a statistically significant association between elevated CGA and survival in panNET. Using a CGA cutoff of twice the upper limit of normal, we observed an association between elevated levels and shorter survival in the cohort overall (adjusted HR 2.8 (1.9, 4.0), p<0.001) (Table 3), and significant associations in all subgroups. ALP levels above the normal upper limit were associated with shorter survival in the cohort overall (Table 3) and in both the small bowel NET and non-panNET subgroups. We did not observe a significant association between elevated ALP and survival for patients with advanced panNET.

Table 3.

Prognostic factors for overall survival (metastatic patients; n= 677)

| Variable | Adjusted HRa (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Older age | 1.02 (1.01, 1.03), p<0.001 |

| Male Gender | 1.2 (0.9, 1.5), p=0.3 |

| Stage at diagnosis | 1.4 (1.0 1.9), p=0.05 |

| Tumor Grade | |

| Intermediate | 1.6 (1.04, 2.5), p=0.03 |

| High | 3.9 (2.5, 6.0), p<0.001 |

| Unknown | 1.5 (0.8, 2.8), p=0.2 |

| Primary Siteb | |

| panNET vs Other | 1.0 (0.8, 1.4), p=0.8 |

| SBN vs Other | 0.5 (0.3, 0.6), p<0.001 |

| panNET vs SBN | 2.3 (1.7, 3.2), p<0.001 |

Hazard Ratios adjusted for age at diagnosis, gender, indicator variables of tumor type, tumor grade; corrected for left truncation

panNET = pancreatic NET, SBN = small bowel NET, Other = other NET

Discussion

Our study provides detailed data on presenting symptoms and clinical outcomes in a large, highly annotated institutional cohort of NET patients. The majority of patients in our cohort had gastroenteropancreatic NET; we focused our analyses on two major subgroups, small bowel NET and pan NET. We found that delays in diagnosis from initial symptoms were shorter than previously reported. We also noted that median disease free and overall survival times were shorter than other institutional studies, but overall survival was longer than population based estimates. Elevated serum biomarkers chromogranin A and alkaline phosphatase were prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic disease.

The distribution of tumor subgroups in our cases differs from population estimates (Maggard et al. 2004; Yao et al. 2008) and reflects a higher proportion of small bowel and pancreatic NETs, likely due to accrual centered at a gastrointestinal cancer clinic. In a recently published large NET study, Faggiano et al. (Faggiano et al. 2012) describe characteristics of 820 NET from a multicenter Italian cohort where the percentage of lung NETs was higher (29% vs our 8%). When restricted to gastrointestinal NETs alone, the relative frequencies in our cohort are similar to those reported in population based series (Maggard et al. 2004).

Abdominal pain was the most common presenting symptom in our cohort. However, a high proportion (24% in our study) was diagnosed incidentally, consistent with prior reports (Pape et al. 2008a; Zerbi et al. 2010; Strosberg et al. 2011; Faggiano et al. 2012). Our observations similarly confirm previous studies that initial presentation with symptoms of hormone hypersecretion is relatively uncommon (14% in our cohort), and when it does occur patients are more likely to already have metastatic disease (Boudreaux et al. 2010; Kulke et al. 2010; Jann et al. 2011; Faggiano et al. 2012).

Published reports have also suggested that delays in diagnosis are common in patients with NETs (Modlin et al. 2008; Vinik et al. 2010). Using patient-reported surveys, we found that, encouragingly, the majority of patients were diagnosed less than 4 months after symptom onset. We also noted, however, that 19.5% of patients were diagnosed from one to 5 years after symptom onset suggesting that prolonged symptom duration prior to diagnosis remains a prominent feature of this disease.

Reports on disease-free survival (DFS) durations for patients with resected NETs are relatively scarce (Pape et al. 2008a; Casadei et al. 2010; Kimura et al. 2011; Landerholm et al. 2011; Boninsegna et al. 2012; Strosberg et al. 2012). Previous studies have reported median DFS durations of 88 months following resection of ileal NET (Landerholm et al. 2011; Le Roux et al. 2011) and 80–85 months following resection of panNET (Gomez-Rivera et al. 2007; Boninsegna et al. 2012). Our median DFS estimates of 70.1 months for patients with small bowel NET and 49.5 months for patients with panNET are somewhat shorter than these previous estimates. Differences in stage distributions did not seem to explain the shorter DFS observed in our cohort; our observed 5-year DFS for panNET with positive lymph nodes was 39% which is lower than the 53% reported for ENETS stage III patients (Strosberg et al. 2012). We note that the majority of resected patients developed a recurrence prior to study enrollment; it seems likely that selective referral of patients who developed earlier recurrence may have influenced our estimates and resulted in shorter DFS estimates than in other studies.

Pathology classification systems for NETs have evolved over time, and re-review of all tumor blocks was not feasible in our dataset. However, we observed that, as in prior studies (Casadei et al. 2010; Kimura et al. 2011), intermediate and high tumor grade was associated with shorter DFS across tumor subtypes. Additionally, lymph node involvement was associated with shorter DFS in patients with resected small bowel or non-panNET, as previously reported (Le Roux et al. 2011). We did not observe a strong association between lymph node involvement and shorter DFS in patients with panNET. Others have also failed to identify associations between lymph node involvement and DFS in panNET, and have suggested that lymph node ratio, rather than presence or absence of lymph nodes, may be a better prognostic measure for such patients (Gomez-Rivera et al. 2007; Casadei et al. 2010; Boninsegna et al. 2012).

Published estimates of median survival times for patients with metastatic NETs are variable. Population-based studies have generally reported shorter times than studies based on institutional cohorts (Yao et al. 2008). A multiplicity of diagnosis codes for NETs, as well as a requirement for a “malignant” diagnosis, may have affected the inclusion of patients in the population-based SEER database and influenced survival estimates in SEER-based studies (Modlin et al. 2008; Yao et al. 2008; Lawrence et al. 2011b). At the same time, selection bias likely overestimates published survival estimates based on data from tertiary referral centers (Pape et al. 2008a; Pape et al. 2008b; Strosberg et al. 2008; Jann et al. 2011). “Immortal time bias” or “left truncation bias” in institutional databases, resulting from the selective inclusion of patients with a favorable prognosis who were diagnosed years prior to evaluation, has been reported to be an important factor in epidemiologic studies of survival, including studies of NETs (Shariff et al. 2008; Strosberg et al. 2011). When we accounted for this bias using a modified Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox regression, we estimated a median overall median survival duration of 5.2 years for patients with metastatic NETs. As in prior studies, we observed differences in overall survival depending on site of tumor origin, with patients who had metastatic small bowel NET tumors experiencing longer survival durations (7.9 years) than those with panNET (3.9 years). These values fall midway between SEER estimates (4.7 yrs and 2 yrs respectively (Yao et al. 2008)) and uncorrected estimates from other large institutional series (10 yrs and 5.8–7.5 yrs respectively), and may represent a more realistic estimate for survival in this patient population. These estimates compare favorably to those for advanced colorectal or pancreatic adenocarcinoma, where 5-year survival rates are estimated to be only 12% and 1.8%, respectively (Howlader et al. 2009) http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2009_pops09/ (accessed 2012).

Associations between elevated CgA and shorter survival have also been reported in small bowel NET and panNET (Janson et al. 1997; Arnold et al. 2008; Ekeblad et al. 2008; Nikou et al. 2008; Korse et al. 2009; Yao et al. 2011). Unanticipated imbalances in CGA between the two arms of a recent randomized trial of patients with advanced NET have been reported to have adversely affected trial outcome (Yao et al. 2012). Our observations confirm that when a cutoff of twice the upper limit of normal is used, elevated CGA is strongly associated with shorter survival in patients with advanced NET (Howlader et al. 2009). We additionally observed an association between elevated ALP and shorter survival in metastatic patients overall, although the hazard ratio was lower than that observed with CGA. We did not observe a statistically significant association between ALP levels and survival in the subgroup of patients with advanced panNET, although this finding may in part be related to the smaller sample size of this subgroup.

In summary, our data, though limited to a single large referral center and subject to potential referral bias, suggest that disease-free and overall survival times for patients with NET, while longer than those for patients with other malignancies, may be shorter than those reported in other institutional databases. We observed a high rate of incidental diagnosis, and in a subgroup of NET patients, prolonged times from symptom onset to diagnosis, suggesting that further effort is needed to facilitate an early diagnosis in patients with NET. For patients with advanced disease, CGA is a robust prognostic marker. The time estimates and prognostic factors identified in this large analysis may be useful in facilitating both the clinical care and the design of trials of therapeutic agents in this disease.

Table 4.

Disease-free and overall survival duration

| Overall Cohort | Small bowel NET | Pancreatic NET | Other NET | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events/N | Median Survival time (yrs) | Events/N | Median Survival time (yrs) | Events/N | Median Survival time (yrs) | Events/N | Median Survival time (yrs) | |

| Disease free survival (Patients with Resected, Localized Diseaseb) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| All patientsb | 124/354 | 5.8 | 39/119 | 5.8 | 34/61 | 4.1 | 51/147 | 7.3 |

| LN − | 48/182 | 7.7, | 2/21 | Not reached, | 15/30 | 4.6, | 31/131 | 7.8, |

| LN +, Log-rank p | 76/172 | 5.0, p=0.001 | 37/98 | 5.6, p=0.05 | 19/31 | 4.0, p=0.7 | 20/43 | 5.0, p=0.002 |

|

| ||||||||

| Overall survival (Patients with Distant Metastasesc) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Uncorrected | 267/677 | 8.0 | 77/272 | 10.1 | 87/182 | 5.9 | 103/223 | 5.9 |

| Diagnosed within 1 yr of consent | 125/357 | 6.0 | 34/151 | 7.9 | 43/94 | 4.7 | 48/112 | 4.5 |

| Corrected for left truncation bias | 267/677 | 5.2 | 77/272 | 7.9 | 87/182 | 3.9 | 103/223 | 3.7 |

Corrected for left truncation bias

Limited to those with documented Lymph Node (LN) status

Metastases at initial presentation or during follow-up

Table 5.

Prognostic value of chromogranin A or alkaline phosphatase in advanced NET

| Overall Cohort | Small Bowel NET | Pancreatic NET | Other NET | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aHR (95%CI)a | Events/N | aHR (95%CI) | Events/N | aHR (95%CI) | Events/N | aHR (95%CI) | Events/N | |

| Chromogranin A | ||||||||

| WNLb | ref | 29/107 | ref | 10/56 | ref | 9/17 | ref | 10/34 |

| > 1xUNLb | 2.2 (1.5, 3.4), p<0.001 | 117/242 | 2.2 (1.1, 4.4), p=0.03 | 242/112 | 1.5 (0.7, 3.3), p=0.4 | 38/65 | 2.9 (1.4, 6.2), p=0.005 | 37/65 |

| WNLb | ref | 43/160 | ref | 13/83 | ref | 16/35 | ref | 14/42 |

| > 2xUNLb | 2.8 (1.9, 4.0), p<0.001 | 103/189 | 3.5 (1.9, 6.8), p<0.001 | 39/85 | 2.7 (1.4, 5.2), p=0.004 | 31/47 | 2.4 (1.2, 4.7), p=0.01 | 33/57 |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | ||||||||

| WNLb | ref | 88/244 | ref | 36/131 | ref | 25/43 | ref | 27/70 |

| > 1xUNLb | 2.0 (1.4, 2.8), p<0.001 | 65/106 | 2.4 (1.3, 4.4), p=0.005 | 16/32 | 1.1 (0.6, 2.0) p=0.8 | 26/45 | 3.7 (1.9, 6.7), p<0.001 | 23/29 |

adjusted Hazard Ratios (aHR) calculated from time of test, adjusted for age at diagnosis, gender, indicator variables of tumor type, tumor grade, and elevated chromogranin A or elevated alkaline phosphatase

UNL= upper limit of normal, WNL=within normal limit

Acknowledgments

Funding

Dr. Ter-Minassian is supported by the Raymond and Beverly Sackler American Association of Cancer Research Fellowship for Ileal Carcinoid Research. MH Kulke is supported in part by NIH grants R01 CA151532-01A1 and 5P50CA127003-05 (Gastrointestinal Cancer SPORE). Additional funding for this project was provided by a grant from Novartis Pharmaceuticals.

The authors are grateful for support from Robert and Ann Ramsey, the Saul and Gitta Kurlat fund for neuroendocrine tumor research, and the Caring for Carcinoid Foundation.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported. MH Kulke has served as a consultant to Pfizer, Novartis and Ipsen. CS Fuchs has served as a consultant to Amgen, Sanofi-Aventis, Pfizer, Genentech, Roche and Bayer.

References

- Arnold R, Wilke A, Rinke A, Mayer C, Kann PH, Klose KJ, Scherag A, Hahmann M, Muller HH, Barth P. Plasma chromogranin A as marker for survival in patients with metastatic endocrine gastroenteropancreatic tumors. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:820–827. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boninsegna L, Panzuto F, Partelli S, Capelli P, Delle Fave G, Bettini R, Pederzoli P, Scarpa A, Falconi M. Malignant pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour: Lymph node ratio and Ki67 are predictors of recurrence after curative resections. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:1608–1615. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreaux JP, Klimstra DS, Hassan MM, Woltering EA, Jensen RT, Goldsmith SJ, Nutting C, Bushnell DL, Caplin ME, Yao JC. The NANETS consensus guideline for the diagnosis and management of neuroendocrine tumors: well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors of the Jejunum, Ileum, Appendix, and Cecum. Pancreas. 2010;39:753–766. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181ebb2a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain KC, Harlow SD, Little RJ, Nan B, Yosef M, Taffe JR, Elliott MR. Bias due to left truncation and left censoring in longitudinal studies of developmental and disease processes. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:1078–1084. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casadei R, Ricci C, Pezzilli R, Campana D, Tomassetti P, Calculli L, Santini D, D’Ambra M, Minni F. Are there prognostic factors related to recurrence in pancreatic endocrine tumors? Pancreatology. 2010;10:33–38. doi: 10.1159/000217604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy TE, Sengupta TP, Paulus J, Ahmed F, Duh MS, Kulke MH. Alkaline phosphatase predicts survival in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:877–884. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9345-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekeblad S, Skogseid B, Dunder K, Oberg K, Eriksson B. Prognostic factors and survival in 324 patients with pancreatic endocrine tumor treated at a single institution. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7798–7803. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faggiano A, Ferolla P, Grimaldi F, Campana D, Manzoni M, Davi MV, Bianchi A, Valcavi R, Papini E, Giuffrida D, et al. Natural history of gastro-entero-pancreatic and thoracic neuroendocrine tumors. Data froma large prospective and retrospective Italian Epidemiological study: THE NET MANAGEMENT STUDY. J Endocrinol Invest. 2012;35:817–823. doi: 10.3275/8102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Rivera F, Stewart AE, Arnoletti JP, Vickers S, Bland KI, Heslin MJ. Surgical treatment of pancreatic endocrine neoplasms. Am J Surg. 2007;193:460–465. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2009 (Vintage 2009 Populations) National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jann H, Roll S, Couvelard A, Hentic O, Pavel M, Muller-Nordhorn J, Koch M, Rocken C, Rindi G, Ruszniewski P, et al. Neuroendocrine tumors of midgut and hindgut origin: tumor-node-metastasis classification determines clinical outcome. Cancer. 2011;117:3332–3341. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janson ET, Holmberg L, Stridsberg M, Eriksson B, Theodorsson E, Wilander E, Oberg K. Carcinoid tumors: analysis of prognostic factors and survival in 301 patients from a referral center. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:685–690. doi: 10.1023/a:1008215730767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura W, Tezuka K, Hirai I. Surgical management of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Surg Today. 2011;41:1332–1343. doi: 10.1007/s00595-011-4547-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimstra DS, Modlin IR, Coppola D, Lloyd RV, Suster S. The pathologic classification of neuroendocrine tumors: a review of nomenclature, grading, and staging systems. Pancreas. 2010;39:707–712. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181ec124e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolby L, Bernhardt P, Sward C, Johanson V, Ahlman H, Forssell-Aronsson E, Stridsberg M, Wangberg B, Nilsson O. Chromogranin A as a determinant of midgut carcinoid tumour volume. Regul Pept. 2004;120:269–273. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korse CM, Taal BG, de Groot CA, Bakker RH, Bonfrer JM. Chromogranin-A and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide: an excellent pair of biomarkers for diagnostics in patients with neuroendocrine tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4293–4299. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.7047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulke MH, Anthony LB, Bushnell DL, de Herder WW, Goldsmith SJ, Klimstra DS, Marx SJ, Pasieka JL, Pommier RF, Yao JC, et al. NANETS treatment guidelines: well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors of the stomach and pancreas. Pancreas. 2010;39:735–752. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181ebb168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulke MH, Siu LL, Tepper JE, Fisher G, Jaffe D, Haller DG, Ellis LM, Benedetti JK, Bergsland EK, Hobday TJ, et al. Future directions in the treatment of neuroendocrine tumors: consensus report of the National Cancer Institute Neuroendocrine Tumor clinical trials planning meeting. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:934–943. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwekkeboom DJ, de Herder WW, Krenning EP. Somatostatin receptor- targeted radionuclide therapy in patients with gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011;40:173–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landerholm K, Zar N, Andersson RE, Falkmer SE, Jarhult J. Survival and prognostic factors in patients with small bowel carcinoid tumour. Br J Surg. 2011;98:1617–1624. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence B, Gustafsson BI, Kidd M, Pavel M, Svejda B, Modlin IM. The clinical relevance of chromogranin A as a biomarker for gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011a;40:111–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence B, Gustafsson BI, Chan A, Svejda B, Kidd M, Modlin IM. The epidemiology of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011b;40:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Roux C, Lombard-Bohas C, Delmas C, Dominguez-Tinajero S, Ruszniewski P, Samalin E, Raoul JL, Renard P, Baudin E, Robaskiewicz M, et al. Relapse factors for ileal neuroendocrine tumours after curative surgery: a retrospective French multicentre study. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:828–833. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggard MA, O’Connell JB, Ko CY. Updated population-based review of carcinoid tumors. Ann Surg. 2004;240:117–122. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000129342.67174.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modlin IM, Moss SF, Chung DC, Jensen RT, Snyderwine E. Priorities for improving the management of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1282–1289. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehar D, Lombard-Bohas C, Olivieri S, Claustrat B, Chayvialle JA, Penes MC, Sassolas G, Borson-Chazot F. Interest of Chromogranin A for diagnosis and follow-up of endocrine tumours. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2004;60:644–652. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.02030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikou GC, Marinou K, Thomakos P, Papageorgiou D, Sanzanidis V, Nikolaou P, Kosmidis C, Moulakakis A, Mallas E. Chromogranin a levels in diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of 42 patients with non-functioning pancreatic endocrine tumours. Pancreatology. 2008;8:510–519. doi: 10.1159/000152000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape UF, Berndt U, Muller-Nordhorn J, Bohmig M, Roll S, Koch M, Willich SN, Wiedenmann B. Prognostic factors of long-term outcome in gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008a;15:1083–1097. doi: 10.1677/ERC-08-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape UF, Jann H, Muller-Nordhorn J, Bockelbrink A, Berndt U, Willich SN, Koch M, Rocken C, Rindi G, Wiedenmann B. Prognostic relevance of a novel TNM classification system for upper gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer. 2008b;113:256–265. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rindi G, Arnold R, Bosman FT, Capella C, Klimstra DS, Kloppel G, Komminoth P, Solcia E. Nomenclature and classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms of the digestive system. In: Bosman FT, Carniero F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, editors. World Health Organization classification of tumours. 4. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer Press; 2010. pp. 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rindi G, Kloppel G, Alhman H, Caplin M, Couvelard A, de Herder WW, Erikssson B, Falchetti A, Falconi M, Komminoth P, et al. TNM staging of foregut (neuro)endocrine tumors: a consensus proposal including a grading system. Virchows Arch. 2006;449:395–401. doi: 10.1007/s00428-006-0250-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shariff SZ, Cuerden MS, Jain AK, Garg AX. The secret of immortal time bias in epidemiologic studies. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:841–843. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007121354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solcia E, Rindi G, Larosa S, Capella C. Morphological, molecular, and prognostic aspects of gastric endocrine tumors. Microsc Res Tech. 2000;48:339–348. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(20000315)48:6<339::AID-JEMT4>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stivanello M, Berruti A, Torta M, Termine A, Tampellini M, Gorzegno G, Angeli A, Dogliotti L. Circulating chromogranin A in the assessment of patients with neuroendocrine tumours. A single institution experience. Ann Oncol. 2001;12(Suppl 2):S73–77. doi: 10.1093/annonc/12.suppl_2.s73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strosberg JR, Nasir A, Hodul P, Kvols L. Biology and treatment of metastatic gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2008;2:113–125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strosberg JR, Cheema A, Weber J, Han G, Coppola D, Kvols LK. Prognostic validity of a novel American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Classification for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3044–3049. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strosberg JR, Cheema A, Weber JM, Ghayouri M, Han G, Hodul PJ, Kvols LK. Relapse-Free Survival in Patients With Nonmetastatic, Surgically Resected Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: An Analysis of the AJCC and ENETS Staging Classifications. Ann Surg. 2012;256:321–325. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824e6108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinik AI, Silva MP, Woltering EA, Go VL, Warner R, Caplin M. Biochemical testing for neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2009;38:876–889. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181bc0e77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinik AI, Woltering EA, Warner RR, Caplin M, O’Dorisio TM, Wiseman GA, Coppola D, Go VL. NANETS consensus guidelines for the diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumor. Pancreas. 2010;39:713–734. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181ebaffd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao JC, Pavel M, Phan AT, Kulke MH, Hoosen S, St Peter J, Cherfi A, Oberg KE. Chromogranin A and neuron-specific enolase as prognostic markers in patients with advanced pNET treated with everolimus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:3741–3749. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, Dagohoy C, Leary C, Mares JE, Abdalla EK, Fleming JB, Vauthey JN, Rashid A, et al. One hundred years after “carcinoid”: epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3063–3072. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao JC, Hainsworth JD, Wolin EM, Pavel ME, Baudin E, Gross D, Ruszniewski P, Tomassetti P, Panneerselvam A, Saletan S, et al. Multivariate analysis including biomarkers in the phase III RADIANT-2 study of octreotide LAR plus everolimus (E+O) or placebo (P+O) among patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumors (NET) J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:abstr 157. [Google Scholar]

- Zerbi A, Falconi M, Rindi G, Delle Fave G, Tomassetti P, Pasquali C, Capitanio V, Boninsegna L, Di Carlo V. Clinicopathological features of pancreatic endocrine tumors: a prospective multicenter study in Italy of 297 sporadic cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1421–1429. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]