Abstract

Objectives/background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) can be prevented by routine colonoscopy. CRC screening in special populations, e.g. spinal cord injury and disorders, presents unique barriers and, potentially, a higher risk of complications. We were concerned about potentially higher risks of complications and sought to determine the safety of colonoscopy.

Methods

Retrospective observational design using medical record review for 311 patients who underwent 368 colonoscopies from two large VA SCI centers from 1997–2008. Patient demographics and peri-procedural characteristics, including indication, bowel prep quality, and pathological findings are presented. Descriptive statistics are presented.

Results

The population was predominantly male and Caucasian, and 199 (64%) had high-level injuries (T6 or above). Median age at colonoscopy was 61 years (interquartile range 53–69). Just <1/2 of the colonoscopies were diagnostic, usually for evidence of rectal bleeding. Although a majority of colonoscopies were reported as poorly prepped, the proportion that were adequately prepped increased over time (from 3.7 to 61.3%, P = <0.0001). Of the 146 polyps removed, 101 (69%) were adenomas or carcinomas. Ten subjects had 11 complications, none of which required surgical intervention.

Conclusions

Although providing quality colonoscopic care in this population is labor intensive, the data suggests that it appears safe and therapeutically beneficial. The results indicate that the risk of screening is outweighed by the likelihood of finding polyps. Recognition of the benefit of colonoscopy in this population may have improved bowel prep and reporting over time. Spinal cord injury providers should continue to offer screening or diagnostic colonoscopy to their patients when indicated, while being aware of the special challenges that they face.

Keywords: Spinal cord injuries, Veterans, Colonoscopy, Complication, Colorectal cancer, Screening

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second most common cancer and the third most common fatal cancer in the USA.1 Fortunately, CRC is one of the few cancers that can be prevented via early polypectomy during screening colonoscopy.2 The general population is advised to undergo CRC screening, such as colonoscopy every 10 years, starting at age 50 years.2 However, compliance rates for this potentially life-saving procedure lag far behind that for other cancer screening tests, such as cervical and breast (83, 74, and 59%, respectively).3,4 Reasons for non-adherence are multifold and include modesty or concern for peri-procedural injury,5 although serious complications after colonoscopy are extremely rare, occurring in less than 1% of cases, and are almost never life threatening.6

The difficulties associated with colonoscopy in persons with spinal cord injury and disorders (SCI&D) are unique. The bowel effluent that results from the bowel preparation process can complicate skin management and cause pressure ulcers, a common co-morbidity in this population.7–9 Also, many persons with SCI&D have concomitant injury to their autonomic nervous system, which can have many adverse consequences. One such condition is neurogenic bowel, characterized by loss of bowel control, resulting in diarrhea, constipation, and/or evacuation difficulty, which can lead to suboptimal bowel preparation, necessitating bowel prep regimen modification in this population.7–14 Patients with T6 or above injuries are also at risk of peri-procedural autonomic dysreflexia, characterized by hypertension and bradycardia. Lastly, sensory deficits in this population can mask the discomfort associated with bowel distension that can alert the endoscopist to decrease insufflation pressure to mitigate the risk of perforation.

For these reasons, providers may be reluctant to refer their SCI&D patients for screening colonoscopy. Patients with SCI&D are less likely than the general population to have received a colon screening procedure.10 In fact, nearly half of persons with SCI&D do not receive screening, even though they interact with the health system more frequently than the general population15 and have similar (or higher) CRC incidence rates.8,9 This is especially disappointing since physician recommendation has been shown to be highly associated with compliance5 and since 2000, CRC screening has been a VA performance measure for both the general veteran population, as well part of the VA SCI Annual Comprehensive Preventive Health Evaluation.16 The importance of screening this population is heightened since sensory deficits and chronic rectal bleeding, either from hemorrhoids or regular digital fecal extraction, may mask symptoms or obviate the use of fecal occult blood tests (FOBTs).17 As the life expectancy of this population now approximates that of the general veteran population,18 regular CRC screening represents a critical opportunity to save lives and improve quality of care. It is unclear, however, if persons with SCI&D are at increased risk of post-colonoscopy complications and whether the benefits of colonoscopy outweigh the risks. We sought to describe: (1) patient demographics, procedure indications, and pathological findings; (2) rates of adequacy of bowel preparation; and (3) the incidence of post-procedural complications in a population of Veterans with SCI&D undergoing colonoscopy.

Methods

After receiving approval from our local Institutional Review Boards, VA administrative data (from the National Patient Clinical Database) files were used to identify all Veterans with SCI&D who underwent colonoscopy from 1997 to 2008 at two VA SCI centers using ICD9 codes 45.22–45.25. We excluded patients without SCI&D, with emergent colonoscopies, colonoscopies performed for a research study, and flexible sigmoidoscopies. We included colonoscopies that did not reach the cecum if the endoscopist did not recommend a repeat CRC procedure. For patients who underwent another colonoscopy within a week, we excluded the first colonoscopy on the basis that it was likely inadequate.

We reviewed subjects’ electronic medical records (VistA Computerized Patient Record System) for demographics (race, ethnicity, sex), pre-procedure symptoms, procedure indication (screening, diagnosis, or polyp/cancer surveillance), length of stay, procedural details, and peri- or post-procedure complications. Bowel preparation that was reported by the endoscopist as poor, fair, inadequate, or suboptimal in any part of the colon was categorized as an “inadequate” preparation. Bowel preparations described as good, excellent, adequate, or optimal were considered “adequate”. We categorized highest motor level into cervical, upper thoracic (T1–T6), lower thoracic (T7–T12), lumbar, or sacral, as well as complete and incomplete injuries. We divided our study period into four equal, consecutive quartiles (quartile 1 (q1): 2/97–12/99 (n = 54), q2: 1/00–11/02 (n = 91), q3: 12/02–9/05 (n = 99), q4: 10/05–9/08 (n = 124)) based on date of colonoscopy. We recorded all medical events (autonomic dysreflexia during the procedure, new pressure ulcers, pneumonia, gastrointestinal bleed or perforation, or death) if they occurred within 7 days of the procedure. Minor complications included post-procedure abdominal pain, bloating, or ileus.

Frequencies, medians, and ranges were reported for all variables. χ2 analysis was used to compare proportions. If normally distributed, Student's unpaired t-test was used to compare means of continuous variables between populations. If not normally distributed, a non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare medians. SAS version software 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, SC, USA) was used for analysis. In order to account for a significant proportion of missing values for bowel preparation, mean imputation was performed via a non-response weighting method. Our imputation method applied the overall proportion of adequate prep to the missing data for each quartile (which tends to bias results towards the null hypothesis). This method is more conservative and preferred if it is thought that the data are missing in a non-random fashion, i.e. if censoring is occurring (e.g. if endoscopists were more likely to document an inadequate prep).

Results

Demographics

Our query resulted in 311 patients with SCI&D who underwent 368 colonoscopies from 5 February 1997 to 16 October 2008, the majority of whom were male Caucasians. Median age was 61 years (interquartile range (IQR): 53–69) at colonoscopy and decreased significantly over time (68 in q1 and 57 in q4, P = 0.001). Median age at time of SCI was 36 years (IQR: 24–55). Sixty-four percent of the sample had higher level injuries (T6 or above). Median length of stay for the 368 colonoscopies was 9 days (IQR: 4–38). Median duration of colonoscopy was 34 minutes (IQR: 25–45). The most common indication for colonoscopy was diagnostic (45%), followed by screening (33%), and surveillance (22%). The most common diagnostic indication was bleeding (66%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Site 1 (n = 186) | Site 2 (n = 125) | Total (n = 311) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | P value | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 183 (98) | 123 (98) | 306 (98) | 0.99 |

| Female | 3 (2) | 2 (2) | 5 (1) | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian/non-hispanic | 115 (63) | 107 (89) | 222 (73) | <0.0001 |

| African–American/non-hispanic | 63 (34) | 12 (10) | 75 (25) | |

| Other | 5 (3) | 1 (1) | 6 (2) | |

| Missing | 3 | 5 | 8 | |

| Diabetes | ||||

| Yes | 53 (28) | 32 (26) | 85 (27) | 0.61 |

| No | 133 (72) | 93 (74) | 226 (73) | |

| SCI motor level | ||||

| Cervical | 88 (48) | 61 (49) | 149 (48) | 0.98 |

| Upper thoracic (T6 and above) | 31 (17) | 19 (15) | 50 (16) | |

| Lower thoracic (T7 and below) | 46 (25) | 32 (26) | 78 (26) | |

| Lumbar/sacral | 19 (10) | 12 (10) | 31 (10) | |

| Missing | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| SCI extent | ||||

| Complete | 39 (30) | 50 (43) | 89 (36) | <0.0001 |

| Incomplete | 91 (70) | 65 (57) | 156 (64) | |

| Missing | 56 | 10 | 66 | |

| SCI level | ||||

| Tetraplegia | 89 (48) | 62 (50) | 151 (49) | 0.81 |

| Paraplegia | 96 (52) | 63 (50) | 159 (51) | |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Median (IQR) | ||||

| Age at time of colonoscopy | 61 (53–70) | 60 (52–69) | 61 (53–69) | 0.84 |

| Age at SCI | 39 (26–56) | 32 (23–50) | 36 (24–55) | 0.33 |

Pathology

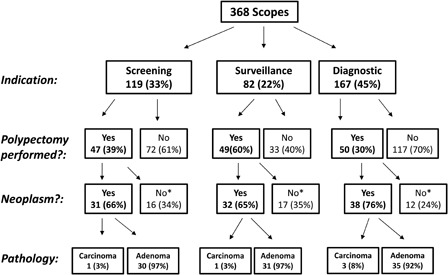

Polypectomy was performed in 146 colonoscopies (40%). On pathological review, 5 (4%) were found to be carcinomas, 96 (67%) were adenomas (pre-malignant lesions), and 42 (29%) were either normal mucosa or hyperplastic polyps (no malignant potential). Location was not documented in three polypectomy cases. Diagnostic colonoscopies were less likely to require polypectomy (31 vs. 48%), but were more likely to be positive for neoplasm (76 vs. 69%; P = 0.0005; Fig. 1). A closer examination of these data indicates that the vast majority (63%) of the adenomas were documented as being in the proximal colon (defined as proximal to the splenic flexure), a location that would not be accessible by flexible sigmoidoscopy alone. Significantly smaller proportion of the tumors were found in the distal colon (37%, P < 0.009), providing further support for colonoscopy screening in this population.8

Figure 1.

Pathology results *No malignant potential (i.e. hyperplastic polyp or normal colonic mucosa)

Bowel prep quality

The proportion of colonoscopies with adequate prep increased significantly over time, from 12.5% in q1 to 58.6% in q4 (P = 0.001), with an overall percentage of 50%. Quality of prep was not associated with level or completeness of SCI. We found that a high proportion of procedures did not include any prep documentation. The results indicate that the proportion of subjects without documented prep quality decreased significantly over time, from 70% in q1 to just 6% in q4 (P < 0.001), with an overall percentage of 23% (n = 86) (Table 2). Using a more conservative imputation method of overall prevalence of adequate preparation, as described above in the Methods section, the proportion of adequately prepped scopes improved significantly (P < 0.001) over time (data not shown).

Table 2.

Adequacy of bowel prep over time (n = 368) – n (%)

| Bowel prepquality | Quartile 1 (2/97–12/99) n = 54 | Quartile 2 (1/00–11/02) n = 91 | Quartile 3 (12/02–9/05) n = 99 | Quartile 4 (10/05–9/08) n = 124 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inadequate | 14 (87.5) | 38 (60.3) | 44 (50.6) | 48 (41.4) | 0.0018 (excludesmissing) |

| Adequate | 2 (12.5) | 25 (39.7) | 43 (49.4) | 68 (58.6) | |

| Missing | 38 | 28 | 12 | 8 | – |

Complications

No patients developed bowel perforation or experienced new rectal bleeding requiring intervention. Five patients had minor complications of abdominal pain, bloating, or ileus. There were 11 medical events recorded for 10 unique patients, including 1 case of new early-stage pressure ulcer, 3 cases of pneumonia. Two deaths occurred within 7 days of the procedure, including one acute myocardial infarction 1-week post-colonoscopy in a subject who also had developed pneumonia. The other death occurred on the same day as the colonoscopy, and no specific cause of death was found in the autopsy. In fact, all medical events occurred in patients with multiple co-morbidities who underwent diagnostic colonoscopy (Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of each colonoscopy

| Site 1 (n = 223) | Site 2 (n = 145) | Total (n = 368) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | P value | |||

| Quality of bowel prep | ||||

| Inadequate (poor/fair) | 83 (54) | 61 (48) | 144 (51) | 0.30 |

| Adequate (good/excellent) | 71 (46) | 67 (52) | 138 (49) | |

| Missing | 69 | 17 | 86 | |

| Indication | ||||

| Routine screening | 77 (35) | 42 (29) | 119 (33) | <0.0001 |

| Surveillance (personal or family history) | 24 (10) | 58 (40) | 82 (22) | |

| Diagnostic | 122 (55) | 45 (31) | 167 (45) | |

| Diagnostic subcategory | ||||

| Bleeding (+FOBT, anemia) | 55 (65) | 22 (69) | 77 (66) | 0.48 |

| Diarrhea/constipation | 15 (18) | 3 (9) | 18 (16) | |

| Other | 14 (17) | 7 (22) | 21 (18) | |

| Missing | 38 | 13 | 51 | |

| Polyps removed | ||||

| Yes | 68 (30) | 78 (54) | 146 (40) | <0.0001 |

| No | 155 (70) | 67 (46) | 222 (60) | |

| Polyp pathology | ||||

| Adenoma | 45 (67) | 51 (67) | 96 (67) | 0.041 |

| Carcinoma | 5 (7) | 0 | 5 (4) | |

| Normal mucosa/hyperplastic polyp | 17 (26) | 25 (33) | 42 (29) | |

| Missing | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Duration of colonoscopy (minutes, Median, IQR) | 30 (21–45) | 35 (30–50) | 34 (25–45) | 0.0015 |

| LOS (days, Median, IQR) | 10 (4–38) | 6 (3–40) | 9 (4–38) | 0.16 |

Note: LOS, length of stay; FOBT, fecal occult blood test.

Discussion

Colonoscopy, although more invasive than other CRC screening modalities, can be both diagnostic and therapeutic and is a safe and well-tolerated procedure in the general population. In a large random sample of more than 50 000 Medicare patients,6 the rate of serious gastrointestinal (GI) events, such as bleeding or perforation, was 0.7%. Minor complications occurred slightly more frequently: 1.2% for abdominal pain, bloating, or ileus. Another large study reported a similar incidence of serious complications of 0.5%, which increased nearly 10-fold in the setting of polypectomy.17 No major complications were observed. We identified six post-colonoscopy medical events of specific relevance to our population (e.g. pressure ulcers, pneumonias, and/or respiratory difficulties). These events were likely directly related to the bowel preparation and sedation, not the instrumentation. Further, the majority of the post-colonoscopy medical events occurred in extremely debilitated patients, who were much sicker than the average Medicare outpatient. A previous study comparing outcomes, including autonomic dysreflexia, in persons with and without SCI&D after colonoscopy did not report any peri-procedural complications.19 Our neoplasm detection rates (68% for adenomas and 4% for adenocarcinoma) support other investigators’ claims that CRC rates in persons with SCI&D approach that of the general population.19,20

Despite the challenges regarding adequate bowel preparation (which improved significantly over time in our sample), colonoscopy did not appear to pose a clinically significant higher risk of complications in this population and is potentially life-saving by detecting CRC. However, an old clinical adage is to not perform a test if you are not going to act on the results. Hence, although colonoscopies may be safe in this population, if a cancer is detected and the patient is deemed not healthy enough to undergo resection, this would weaken the argument to screen this population. However, a study by of 44 Veterans with SCI&D who underwent large bowel resection reported a 30-day mortality of 4.5% and an in-hospital complication rate of 34%, rates that are comparable to the general population, suggesting that SCI&D patients can tolerate bowel resection well.8 Further, many adenomatous polyps are amenable to removal during colonoscopy, potentially preventing a more invasive procedure in the future.

One striking finding of our sample was the high rate of inadequate bowel preparation in this population, which has been observed by other researchers when compared with healthy patients.8–14,20 In the non-SCI&D population, colonoscopy is usually performed as an outpatient procedure; the patient self-administers the bowel prep the night before and usually goes home the same day as the procedure. However, in order to accommodate an intensified and longer bowel prep regimen7 and to assist with pressure ulcer prevention, many patients with SCI&D are admitted prior to the procedure or receive colonoscopy during an unrelated admission, as evidenced by our long median length of stay. Not only does poor bowel prep result in depletion of scarce health care resources, it can also increase the risk for missing cancerous lesions, which emphasizes the importance of educating endoscopists regarding proper bowel regimens for the SCI&D population. Encouragingly, the proportion of colonoscopies with adequate bowel prep and with procedure documentation increased significantly over time in our study. Many factors could have influenced this trend, including advances in preparation techniques, nursing care, and increased awareness regarding the unique needs of this population. Another finding supporting increased provider awareness regarding the importance of screening this population for CRC is that the median age at time of colonoscopy decreased by over a decade during our study period.

There are several limitations to our study. (1) Although our sample size is large, we did not have a control group, other than what has been reported in the literature. However, the rates of complication for colonoscopy in comparable healthy Veteran populations is very robust as these data are collected and reported for all Veterans using VA health care on an annual basis. (2) Our study was conducted at two of the largest VA SCI centers (which represents about 10% of the overall population of Veterans with SCI) over a 10-year period. It is possible that practices at these centers do not generalize to other VA SCI centers or to spoke sites. (3) Clinical care for patients with SCI&D has evolved over the past decade in a multitude of ways. Variation in nursing practices, endoscopic proficiency, and sedation techniques makes it difficult to determine which factors are responsible for our findings. (4) Retrospective chart analyses are subject to missing or erroneous data. Data on the specialty of the physicians ordering the prep and which type of bowel preparation were missing for many patients and thus were not reported. Also, some procedure times were unreliable (i.e. listed as under 10 minutes with documentation of cecal intubation) and tumor location was not documented for four cases. As mentioned previously, we also encountered a significant proportion of missing procedure notes, which has been documented in other studies of Veterans undergoing colonoscopy.21 One likely reason for the high rate of missing data found early on in the study period is that widespread use of VA's electronic medical record system began in 1998. (5) Lastly, given that our outcome of interest was rare, it is possible that our sample size was underpowered to detect the true rate of complications after colonoscopy in Veterans with SCI&D. Also, we only captured incident complications and did not examine whether colonoscopy worsened prevalent conditions such as pressure ulcers. However, our follow-up was fairly robust, given that many of these patients were either in house for at least 7 days and had their re-admission or post-acute outpatient information captured by the medical record. This is the strength of the VA computerized medical record system as compared with the private sector, in which most colonoscopies are outpatient procedures, and thus, post-procedure complications may not be captured.

Conclusion

Despite being resource-intensive and technically difficult, as evidenced by increased prep time and longer lengths of stay, colonoscopy in our population of relatively medically stable individuals with SCI&D had a low rate of complications and a high rate of colonic neoplasm detection. Given that almost one-third of our patients had pre-cancerous lesions (adenomas) removed or cancers detected, this would suggest a survival advantage vis-a-vis the development of CRC. Only when the CRC screening rate increases (and is closer to that of the general VA population), can the question of “true” CRC rates in SCI be addressed. Our finding that most of the tumors were found in the proximal location supports colonoscopy over other screening methods for persons with SCI.8,9 Thus, we agree with other researchers who recommend that the indications for CRC screening in medically stable persons with SCI&D be the same as the general population,20,21 albeit with an extended colonic preparation period and cross-disciplinary care, especially for patients with a history of autonomic dysreflexia. Finally, for best results, we emphasize that standard bowel preparations for people with SCI&D should occur over an extended time period (i.e. 2 days as a default) and include multiple methods of preparation (e.g. combine both polyethylene glycol/electrolyte solutions, as well as a stimulant laxative such as bisacodyl and/or magnesium oxide).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the assistance of Scott Miskevics with obtaining source data.

Research and funding support for this study were provided by the SCI Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (SCI-QUERI), VA Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) Service. The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2010;60(5):277–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Brooks D, Saslow D, Brawley OW. Cancer screening in the United States, 2010: a review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin 2010;60(2):99–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chu LL, Weinstein S, Yee J. Colorectal cancer screening in women: an underutilized lifesaver. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011;196(2):303–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Cancer screening – United States, 2010. MMWR 2012;61(3):41–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denberg TD, Melhado TV, Coombes JM, Beaty BL, Berman K, Byers TE, et al. Predictors of nonadherence to screening colonoscopy. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20(11):989–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Mariotto AB, Meekins A, Topor M, Brown ML, et al. Adverse events after outpatient colonoscopy in the Medicare population. Ann Intern Med 2009;150(12):p849–857, W152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ancha HR, Spungen AM, Bauman WA, Rosman AS, Shaw S, Hunt KK, et al. Clinical trial: the efficacy and safety of routine bowel cleansing agents for elective colonoscopy in persons with spinal cord injury – a randomized prospective single-blind study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;30(11–12):1110–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stratton MD, McKirgan LW, Wade TP, Vernava AM, Virgo KS, Johnson FE, et al. Colorectal cancer in patients with previous spinal cord injury. Dis Colon Rectum 1996;39(9):965–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frisbie JH, Chopra S, Foo D, Sarkarati M. Colorectal carcinoma and myelopathy. J Am Paraplegia Soc 1984;7(2):33–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lavela SL, Weaver FM, Smith B, Chen K. Disease prevalence and use of preventive services: comparison of female Veterans in general and those with spinal cord injuries and disorders. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2006;15(3):301–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barber DB, Rogers SJ, Chen JT, Gulledge DE, Able AC. Pilot evaluation of a nurse-administered carepath for successful colonoscopy for persons with spinal cord injury. SCI Nurs 1999;16(1):14–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burke CA, Church JM. Enhancing the quality of colonoscopy: the importance of bowel purgatives. Gastrointest Endosc 2007;66(3):565–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singal AK, Rosman AS, Bauman WA, Korsten MA. Recent concepts in the management of bowel problems after spinal cord injury. Adv Med Sci 2006;51:15–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stiens SA, Fajardo NR, Korsten MA. The gastrointestinal system after spinal cord injury. New York: Demos Medical Publishing; 2003. p. 321–48 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnston MV, Diab ME, Chu BC, Kirshblum S. Preventive services and health behaviors among people with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2005;28(1):43–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collins EG, Langbein WE, Smith B, Hendricks R, Hammond M, Weaver F. Patients’ perspective on the comprehensive preventive health evaluation in Veterans with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2005;43(6):366–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levin TR, Zhao W, Conell C, Seeff LC, Manninen DL, Shapiro JA, et al. Complications of colonoscopy in an integrated health care delivery system. Ann Intern Med 2006;145(12):880–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strauss DJ, Devivo MJ, Paculdo DR, Shavelle RM. Trends in life expectancy after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2006;87(8):1079–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han SJ, Kim CM, Lee JE, Lee TH. Colonoscopic lesions in patients with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2009;32(4):404–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rabadi MH, Vincent AS. 2012 Colonoscopic lesions in Veterans with spinal cord injury. JRRD 49(2):257–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palmer LB, Abbott DH, Hamilton N, Provenzale D, Fisher DA. Quality of colonoscopy reporting in community practice. Gastrointest Endosc 2010;72(2):321–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]