Abstract

Significance: Chagas disease (CD) affects several million people in Latin America and is spreading beyond its classical boundaries due to the migration of infected host and insect vectors, HIV co-infection, and blood transfusion. The current therapy is not adequate for treatment of the chronic phase of CD, and new drugs are warranted. Recent Advances: Trypanosoma cruzi is equipped with a specialized and complex network of antioxidant enzymes that are located at different subcellular compartments which defend the parasite against host oxidative assaults. Recently, strong evidence has emerged which indicates that enzyme components of the T. cruzi antioxidant network (cytosolic and mitochondrial peroxiredoxins and trypanothione synthetase) in naturally occurring strains act as a virulence factor for CD. This precept is recapitulated with the observed increased resistance of T. cruzi peroxirredoxins overexpressers to in vivo or in vitro nitroxidative stress conditions. In addition, the modulation of mitochondrial superoxide radical levels by iron superoxide dismutase (FeSODA) influences parasite programmed cell death, underscoring the role of this enzyme in parasite survival. Critical Issues: The unraveling of the biological significance of FeSODs in T. cruzi programmed cell death in the context of chronic infection in CD is still under examination. Future Directions: The role of the antioxidant enzymes in the pathogenesis of CD, including parasite virulence and persistence, and their feasibility as pharmacological targets justifies further investigation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 19, 723–734.

Introduction

Chagas disease (CD), caused by the parasitic protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi, remains a major public health concern in Latin America, with an estimated total of 8 million people infected and 28 million at risk (http://apps.who.int/tdr/publications/tdr-research/publications/reporte-enfermedadchagas/pdf/swg_chagas.pdf). Moreover, the disease is spreading worldwide as a result of migration (mammalian host and insect vectors); HIV co-infection; blood transfusion; and organ transplantation; evidenced by the fact that 1 in every 4700 blood donors test positive for T. cruzi. An estimate of 300,000 infected people is found in the United States as of 2010 (www.cdc\chagas\factsheet.htlm).

Life Cycle of T. cruzi and Progression of CD

The life cycle of T. cruzi involves the invertebrate host (triatomid hematophage arthropod), where the noninfective epimastigotes replicate and differentiate to the nonreplicative infective stage (metacyclcic trypomastigotes) at the rectum of the insect vector. During the differentiation process from noninfective epimastigotes to infective metacyclic trypomastigotes (a process called metacylocgenesis), the parasite undergoes complex morphological and biochemical changes in order to effectively infect and survive in the hostile environment of the vertebrate host. Metacyclic trypomastigotes should gain access to the internal medium of the vertebrate host via the mucosal and/or skin wounds invading different cell types, including macrophages, cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts, and smooth and striated muscle cells (4). The acute phase of the disease lasts between 4–8 weeks, generally with mild flu-like self-limiting symptoms, although 10% of symptomatic cases develop severe myocarditis and/or meningoencephalitis. Organ and tissue damage during acute T. cruzi infection is caused by the parasite itself and by the host's acute inflammatory response, elicited by the presence of the pathogen. Between 30% and 40% of patients will develop chronic CD either in its cardiac, digestive, or cardio-digestive manifestation between 10 and 30 years after the initial infection. The pathological findings observed in chronic chagasic cardiomyopathy include widespread destruction and dysfunction of mitochondrial myocardial cells (68, 69), myocardium inflammation, fibrosis, and hypertrophy along with scarce parasite numbers. Exacerbation of the chronic stage with increased blood parasitemia and intracellular parasite replication is found in individuals with immunosuppressive treatment, indicating the pivotal role of the host-immune mediators in the control of parasite proliferation and persistence (57). The pathogenesis of chronic CD myocarditis is complex and involves parasite immune evasion strategies, genetically determined host-immune homeostasis defects, and autoreactive phenomena in the presence of autoantibodies. Damaged tissue in the chronic phase is also accompanied by genetic material from T. cruzi, indicating an active role of parasite persistence in pathology (7, 57). Indeed, in spite of a robust immune response, the host fails to eliminate parasites from tissues, and the pathogen is able to chronically persist.

Host-Derived Nitroxidative Stress During T. cruzi Infection

In the acute infection, resident macrophages at the site of parasite invasion are among the first professional phagocytes that are invaded by T. cruzi (29, 39). On invasion, infective insect-borne metacyclic trypomastigotes should survive and evade the highly oxidative environment found inside the phagosome in order to establish the infection (1, 46, 50). We have recently shown that during the phagocytosis of T. cruzi metacyclic trypomastigotes, macrophage membrane-associated NADPH oxidase is activated, resulting in a sustained (60–90 min) superoxide radical (O2•−) production toward the internalized parasite (1). O2•− either dismutates to H2O2 or reacts with nitric oxide (·NO) derived from the inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in a diffusion-controlled reaction, to yield peroxynitrite (ONOO−; k=1×1010 M−1 s−1), a strong oxidant and potent cytotoxic effector molecule against T. cruzi (1, 2, 16). The control of intraphagosomal parasite survival, before the replicative amastigotes reach the “safe” cytoplasmic environment, largely depends on the macrophage production of ONOO− (1, 46). In this scenario, the levels of parasite antioxidant defenses at the onset of macrophage invasion may tilt the balance toward pathogen survival (44, 46, 48). Some parasites manage to evade the initial assault of the immune system and infect other organs such as the heart and digestive tract, disseminating the infection and favoring the progression to the chronic stage of CD. Chronic chagasic cardiomyopathy is characterized by the presence of pseudo cysts of amastigote nests in the cardiac fiber. T. cruzi invasion to cardiomyocytes triggers the production of inflammatory mediators (TNF-α, IL-1β) and the induction of cardiomyocyte iNOS with the subsequent generation of sustained amounts of ·NO (13, 32). T. cruzi invasion and proinflammatory cytokines along with ·NO generation lead to cardiomyocyte mitochondrial dysfunction with an increase in reactive oxygen species that may contribute to cardiomyocyte death and chronic heart failure in chagasic patients (7, 24).

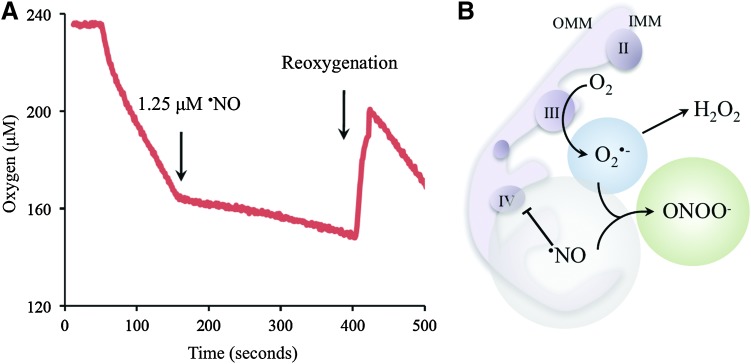

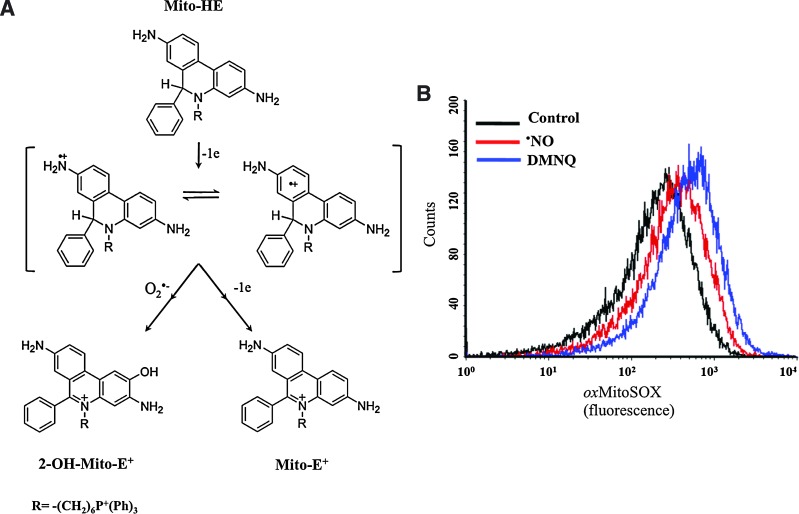

The ·NO pathway is indicated as a parasite control mechanism, as revealed by experiments performed on infected cardiomyocytes cultures. In addition, the role of the IL-12/INF-γ/iNOS axis in the control of T. cruzi infection and its implication for the outcome in CD has been well documented in key experiments using knockout mice for INF-γ, IL-12, and NOS isoforms (20, 37). ·NO oxidative damage largely depends on its reaction with superoxide (Fig. 1). Peroxynitrite can cause damage by direct reactions via one or two electron oxidations mechanisms to several molecules such as thiols and metal centers (21), also yielding secondary reactive species, including hydroxyl radical (·OH), nitrogen dioxide (·NO2), and carbonate (CO3·−) radicals that can oxidize lipids, DNA, and participate in protein oxidation and nitration, stable indicators of nitroxidative stress (9, 21, 40) (Fig. 1). Host-tyrosine nitrated proteins have been identified in heart lesions in the mouse model of CD (17, 40). Moreover, nitrated and oxidized plasma proteins as well as circulating myeloperoxidase [a heme-peroxidase released by PMNs that also participates in protein tyrosine nitration (54)] have been found in the plasma of patients with CD (17, 18). ·NO is not a strong oxidant or reactive species per se and by itself is unlikely to account for direct damage to the parasite (21). The inhibition of the respiratory chain by ·NO in mammalian mitochondria via interactions with cytochrome c oxidase is accompanied by a larger steady-state level of reduced respiratory complexes, which, in turn, favors intramitochondrial O2•− formation (11, 55). After the acute infection, host-derived ·NO may diffuse and reach intracellular amastigotes, leading to the generation of intramitochondrial O2•− and ONOO− formation. Results from our laboratory showed that T. cruzi mitochondrial oxygen consumption was reversibly inhibited by ·NO (Fig. 2A, B), and mitochondrial O2•− production under these conditions was detected using the mitochondria-targeted ethidium-derived probe [MitoSOX™, live-cell permeable probe selectively targeted to mitochondria (59)] (Fig. 3A, B). This result makes feasible the concept of ·NO-mediated control of parasite proliferation in CD via intra-parasitic ONOO− formation. In this scenario where host-derived oxidant mediators are actively generated, the antioxidant armamentarium of T. cruzi becomes crucial for parasite survival and persistence.

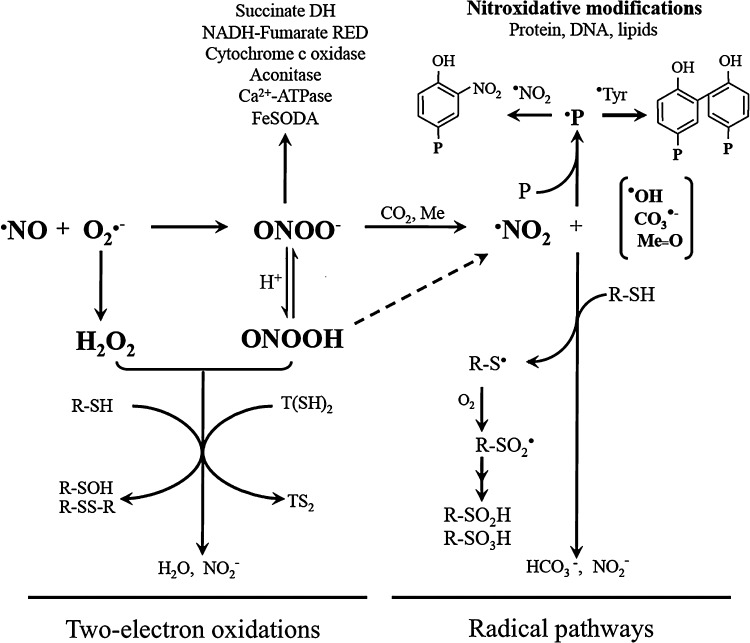

FIG. 1.

Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species cytotoxicity against Trypanosoma cruzi. Peroxynitrite anion (ONOO−), formed from the diffusion-controlled reaction between ·NO and superoxide radical (O2•−), is in equilibrium with peroxynitrous acid (ONOOH). Peroxynitrite cytotoxicity can arise by the direct reaction via two-electron oxidation as well as by secondary-derived radicals via one-electron oxidation processes. Two-electron oxidations include the reaction with low-molecular-weight thiols [RSH, T(SH)2], leading to the corresponding sulfenic (R-SOH) and disulfide (R-SS-R, TS2) derivatives. Radical pathways depends on (i) the homolysis of ONOOH to nitrogen dioxide (·NO2) and hydroxyl radicals (·OH); (ii) the reaction of ONOO− with carbon dioxide (CO2) that yields carbonate (CO3·−) and ·NO2 radicals; and (iii) the ONOO− reaction with transition metal centers (Me) yielding ·NO2 and the corresponding oxo-metal complex (Me=O). The quantitative relevance of the different reaction pathways in specific cells/tissue compartments has been analyzed elsewhere (21). ·NO2, CO3·−,·OH, and Me=O can oxidize protein tyrosine to the tyrosyl radical (·Tyr) and cysteine to thiyl radicals (R-S·). Tyrosyl radicals either dimerize to form 3,3′di-tyrosine or in the presence of ·NO2 react to form protein-3-nitrotyrosine. Thiyl radicals may form mixed disulfides or react with O2 to yield higher oxidation states of the sulfur (R-SO2H, R-SO3H sulfinic, and sulfonic acids, respectively). Different parasite targets for ·NO, O2•−, ONOO−, and its derived secondary radicals have been identified in T. cruzi, including the inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase (this work), aconitase (47), enzymes of metabolic pathways [succinate dehydrogenase and NADH-fumarate reductase (60)], mitochondrial iron superoxide dismutase (FeSODA) (this work, unpublished results), and Ca2+-ATPase (65).

FIG. 2.

Nitric oxide (·NO) interactions with T. cruzi. (A) The reversible·NO-dependent inhibition of T. cruzi mitochondrial respiration was evaluated in cells (1×108 epimastigotes) with endogenous respiratory substrates using a gas-tight chamber equipped with a Clark-type oxygen electrode connected to a computer with the DUO.18 processing program (World Precision Instruments). As indicated in the figure, authentic •NO (1.25 μM) was added to the chamber followed by reoxygenation by air bubbling. The transient inhibition of T. cruzi mitochondrial respiration in the presence of •NO was fully displaced by O2, demonstrating the reversible nature of the process. (B) Representation of T. cruzi mitochondria showing the •NO-dependent interaction with the terminal cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV). The inhibition of parasite mitochondria respiration by host-derived •NO leads to O2•− production (mainly by ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase, complex CIII) with the subsequent intramitochondrial ONOO− formation. OMM, outer mitochondrial membrane; IMM, inner mitochondrial membrane. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertonline.com/ars

FIG. 3.

Intramitochondrial superoxide radical detection in •NO-challenged parasites. (A) Schematic representation of the reactions involved in Mito-HE (MitoSOX) oxidation. Mito-HE with a triphenylphosphonium moiety is targeted to mitochondria in response to the electrochemical membrane potential. Mito-HE can be oxidized by O2•− to yield the hydroxylated product (2-OH-Mito-E+) or by other oxidants to yield the two-electron oxidation product (Mito-E+) (59). Both products have distinctive fluorescence spectra and can be separated by HPLC techniques, providing a specific O2•− assay (80). (B) Detection of mitochondrial O2•− production by •NO-challenged epimastigotes. Preloaded (MitoSOX, 5 μM for 30 min) epimastigotes (1×108) were exposed to an •NO flux (NOC-18; 1 μM min−1 during 2 h) and MitoSOX oxidation analyzed by flow cytometry. The redox-cycling agent 2,3-dimethoxy-1,4-naphthoquinone (DMNQ, 30 μM, 3 nM O2•− min−1/108 parasites) was used as a positive control for O2•− production (48). To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertonline.com/ars

T. cruzi Antioxidant Network

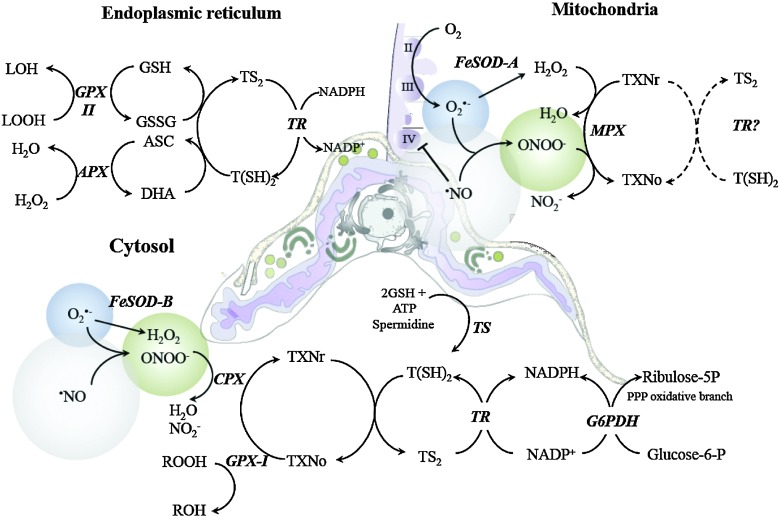

Antioxidant defenses in T. cruzi rely on a sophisticated system of linked pathways in which reducing equivalents from NADPH (derived from the pentose phosphate pathway) are delivered to a variety of enzymatic detoxification systems through the dithiol trypanothione [T(SH)2, N1,N8-bisglutathionylspermidine] and the thioredoxin homologue tryparedoxin (TXN; Fig. 3) (26). Trypanothione is synthesized in two sequential steps in which two molecules of glutathione (GSH) are covalently bound to the terminal NH2 groups of spermidine by a single cytosolic enzyme called T. cruzi trypanothione synthetase (TcTS) (42). Five distinct peroxidases have been identified in T. cruzi, differing in their subcellular location and substrate specificity. Glutathione peroxidase-I (TcGPXI, located at the cytosol and glycosome) and TcGPXII (located at the endoplasmic reticulum) confer resistance against hydro- and lipid-hydroperoxides, respectively, and use GSH and/or TXN as reducing substrates (72, 76). The T. cruzi cytosolic tryparedoxin peroxidase (TcCPX) and T. cruzi mitochondrial tryparedoxin peroxidase (TcMPX, typical two-cysteine peroxiredoxins belonging to the AhpC/Prx subfamily) have the capacity to detoxify ONOO−, H2O2 and small-chain organic hydroperoxides using TXN (Fig. 4) (48, 51, 66, 77). Parasite resistance against ONOO− toxicity is afforded by CPX overexpression (Fig. 4A), while the mutation in the peroxidatic Cys52 (Cys52Ala) of CPX fails to confer resistance, indicating the catalytic nature of the process (Fig. 5A, inset). Moreover, TcMPX overexpressers are more resistant to ·NO fluxes, which is in line with the predicted ·NO-mediated intramitochondrial ONOO− formation and detoxification by this peroxiredoxin (Fig. 5B). Whether the complete system of TXN, T(SH)2, and TR is found in the mitochondria is still a matter of debate. Finally, an ascorbate-dependent heme-peroxidase (TcAPX), located at the endoplasmic reticulum, confers resistance against H2O2 challenge using ascorbate as the reducing substrate (48, 73). The complete detoxification capacities of the different peroxidases of T. cruzi are still under investigation. In particular, further studies are required to find out whether thiol-dependent GPX-I and GPX-II can catalyze ONOO− reduction and detoxification in T. cruzi.

FIG. 4.

Subcellular distribution of the antioxidant network in T. cruzi. The antioxidant network of T. cruzi is formed by a number of enzymes and nonenzymatic redox-active molecules distributed in the endoplasmic recticulum, glycosomes, mitochondrion, and cytosol. The final electron donor for all the enzymatic systems is the NADPH derived from the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP). The reducing equivalents are funneled through the trypanothione [T(SH)2], glutathione (GSH), ascorbate (ASC), and/or tryparedoxin (TXN) redox systems. Endoplasmic reticulum: Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is metabolized by an ascorbate-dependent hemoperoxidase (APX) using ASC as the electron donor. Dehidroascorbate (DHA) is thought to be reduced by a direct reaction with T(SH)2. H2O2 in the presence of redox-active metals can initiate lipoperoxidation reactions that generate organic hydroperoxides (LOOH), which are substrates of GSH-dependent-peroxidase II (GPX-II) that uses GSH. T(SH)2 reduces oxidized glutathione (GSSG) to GSH, while trypanothione reductase (TR) reduces oxidized trypanothione (TS2). Mitochondrion: the electron transport chain (Complex II: succinate dehydrogenase, CII; Complex III: ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase, CIII and Complex IV: cytochrome c oxidase, CIV) is a principal site for superoxide (O2•−, blue sphere) formation mainly at CIII. The mitochondrial isoform of FeSODA catalyzes the dismutation of O2•− to H2O2. When host-derived •NO (gray sphere) reaches the mitochondrion, it inhibits mitochondrial respiration at CIV (with an enhanced production of O2•− by CIII) by outcompeting FeSODA for O2•− to form ONOO− (green sphere). Mitochondrial peroxiredoxin (MPX) catalytically decomposes H2O2 and/or ONOO− Figure 6 probably uses reduced TXN (TXNR) and T(SH)2 as the reducing substrate (dashed arrows). Cytosol: The antioxidant enzymes in the cytosol include cytosolic peroxiredoxin (CPX), FeSODB, and GPX-I. T(SH)2 is synthesized from two molecules of GSH and one spermidine in a reaction catalyzed by the enzyme trypanothione synthetase (TS). The oxidative branch of the PPP is induced in the metacyclic trypomastiogote, ensuring the provision of reducing equivalents from NADPH (25). The size of the spheres for •NO, ONOO−, and O2•− illustrates the diffusional capabilities of the oxidants. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6P-DH); nitrite (NO2−). Adapted from Piacenza et al. (46). To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertonline.com/ars

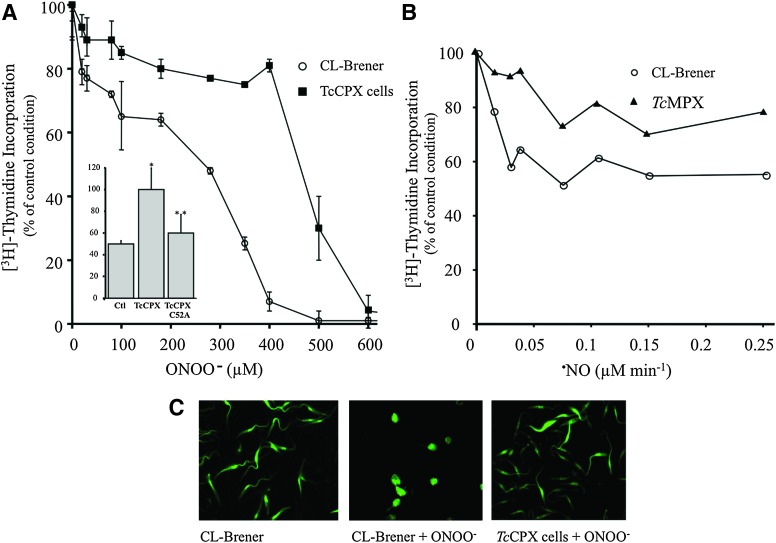

FIG. 5.

Resistance of T. cruzi CPX and MPX overexpressers to peroxynitrite challenge. (A) T. cruzi epimastigotes from wild-type (CL-Brener, control) or CPX overexpressers (3×108 cells·ml−1) were exposed to ONOO− (0–700 μM), and parasite survival was assayed by [3H]thymidine incorporation (48). Results are expressed as percentage [3H]thymidine incorporation compared with control conditions (no peroxynitrite addition) for each cell line. Inset: T. cruzi epimastigotes (CL-Brener; T. cruzi cytosolic tryparedoxin peroxidase [TcCPX] overexpressing cells, and TcCPX C52A mutants; 3×108 cells·ml−1) were exposed to a single dose of 300 μM peroxynitrite. Cell viability was evaluated as in (A). **p<0.05 compared with *. The results show the efficiency of TcCPX in ONOO− detoxification. (B) Protection against intramitochondrial peroxynitrite formation is achieved by T. cruzi MPX overexpressers. Wild-type (CL-Brener) and T. cruzi mitochondrial tryparedoxin peroxidase (TcMPX) overexpressers were exposed to ·NO fluxes generated by the ·NO donor NOC-18 (NOC-18, 0–2 mM; t 1/2∼ 18 h, Alexis) for 1 h. After treatment, parasite viability was evaluated as in (A). (C) 6-carboxy-fluorescein di-acetate (6-CFDA, 10 μM) preloaded wild-type (CL-Brener) and TcCPX parasites (3×108 cells ml−1) were exposed to a single dose of 250 μM ONOO−, and cell morphology was evaluated by epifluorescence microscopy (×60). Adapted from (48). To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertonline.com/ars

T. cruzi contains four iron superoxide dismutases (FeSODs) that detoxify O2•− generated in the cytosol (TcSODB1), glycosomes (TcSODB1-2), and mitochondria (TcSODA and C) (33). The biochemical and cell biology characterization of the T. cruzi FeSODs repertoire in terms of free radical events has been minimally explored (28, 47, 64, 74). The role of mitochondrial TcFeSODA could be particularly relevant, as this organelle is a key source of O2•− and presumably ONOO−. The preliminary data of our laboratory indicate that, although fluxes of O2•− and ·NO (SIN-1, 0–10 mM) cause a very modest enzyme inactivation, TcFeSODA activity is inhibited by biologically relevant ONOO− concentrations, which is accompanied by nitration on tyrosine residues (Martinez, Piacenza, et al., unpublished results). The nitration of a critical tyrosine near the active site can account for the observed inhibition, as previously shown for Tyr-34 in MnSOD (38, 53, 78). These data support the concept that TcFeSODA play an important role in parasite oxidant detoxification pathways by preventing ONOO− formation in this organelle trough O2•− dismutation, all of which contribute to neutralize cytotoxicity. Due to its unique characteristics when compared with the mammalian counterparts, components of the T. cruzi antioxidant system have been considered good targets for chemotherapy (23, 26, 30).

Since the end of the 1960s and the beginning of the 1970s, two drugs have been used for the treatment of CD: a 5-nitrofuran, nifurtimox [NFX, (4[5-nitrofurfurylidene)amino]-3-methylthiomorpholine-1,1-dioxide] and a 2- nitroimidazole, benznidazole (BZ, N-benzyl-2-nitroimidazole-1-acetamide) (62). Both are prodrugs that undergo intracellular activation by nitroreductases (NTRs), leading to cytotoxicity within the parasite, although the precise mechanism of action and parasite targets remain to be established (70, 71, 75). Since a long time, it has been proposed that NFX trypanocidal activity involves the generation of nitroanion radicals through NTR type II activity (one-electron reduction), which, in turn, generates O2•− radicals (19, 34). In addition, NFX-derived metabolites can lead to adduct formation with GSH and TSH, contributing to parasite oxidative stress (58). However, the direct evidence between drug-induced oxidative stress and trypanocidal activity is limited and arises from functional studies where (i) T. brucei parasites lacking cytosolic SODB are more sensitive to NFX and BZ (52); and (ii) the reported overexpression of mitochondrial TcFeSODA in an in vitro-derived BZ-resistant T. cruzi strain (41). It is now known that BZ and NFX trypanocidal activity depends on NTR type I activity, which is absent in mammalian cells and is the base for parasite selectivity (70). NTR type I activity catalyzes the two-electron reduction of nitroheterocyclic compounds producing toxic hydroxylamine derivatives and other metabolites that can induce biomolecule modifications and DNA strand breaks, leading to parasite death (8, 36, 75).

Moreover, it was recently found that in the BZ-resistant T. cruzi population, the parasite phenotype is associated with the loss of a NTR gene copy with changes in neither parasite SOD expression nor activity (36). The unambiguous determination of BZ-NFX toxicity mechanisms as well as the participation of antioxidant enzymes, and especially that of FeSOD, in resistant T. cruzi phenotypes needs further investigation. SODs readily eliminates O2•− and may contribute to T. cruzi survival in the vertebrate host by immune evasion mechanisms, such as (i) protection from direct cytotoxic effects of O2•−, mainly generated by parasite mitochondria; (ii) inhibiting the formation of ONOO− in ·NO-challenged parasites; and (iii) participating in the modulation of redox signaling processes. While the protein fold and structure of FeSOD are considered similar to mammalian MnSOD, efforts are being made to unravel the structural characteristics to allow the generation of specific inhibitors (6).

Redox Signaling of T. cruzi Programmed Cell Death

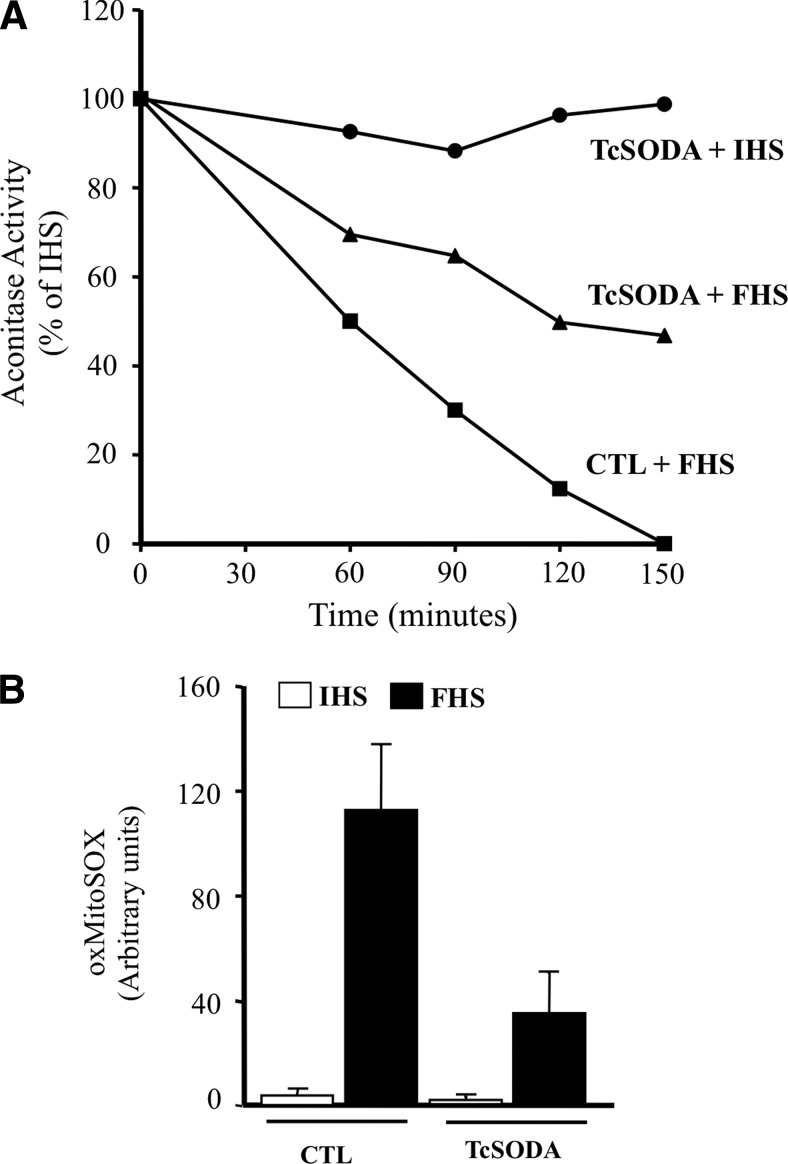

T. cruzi can undergo a programmed cell death process that is triggered by a variety of stimuli and involving alterations of cellular homeostasis (3, 27, 49). The intracellular misbalance of the parasite redox status can disengage programmed cell death in epimastigotes of T. cruzi (27, 44, 47). After appropriate challenges (fresh human serum [FHS]), a rapid loss of low-molecular thiols (i.e., T(SH)2, glutathionyl-spermidine, and GSH) occurs accompanied by mitochondrial dysfunction; disruption of mitochondrial homeostasis in the parasite is characterized by mitochondrial Ca2+ influx, an increase in mitochondrial O2•− production, impaired oxidative phosphorylation, oxygen consumption, and the release of cytochrome c to the cytosol (47). FHS-dependent mitochondrial O2•− generation is evidenced by aconitase inhibition due to the disruption of the 4Fe4S cluster (Fig. 6A). The T. cruzi cell death phenotype is accompanied by phosphatydylserine exposure to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane and by nuclear DNA condensation and fragmentation, all common morphological features of metazoan apoptosis (27, 47, 49). Notably, the overexpression of FeSODA prevented FHS-triggered processes, including aconitase inhibition, MitoSOX oxidation, and programmed cell death, underscoring the role of mitochondrial O2•− in the redox signaling of this process (Fig. 6A, B).

FIG. 6.

Enhanced mitochondrial O2•− production during T. cruzi programmed cell death. (A) Mitochondrial aconitase inhibition during programmed cell death. Wild-type and mitochondrial FeSODA overexpressers were incubated with 20% (v/v) inactivated human serum (HIS, control), or 20% or 40% (v/v) fresh human serum (FHS), and aconitase was measured in total parasite extracts at the indicated times. The results show that after the death stimuli, mitochondrial (but not cytosolic) aconitase is inactivated in wild-type parasites and partially protected in mitochondrial FeSODA overexpressers, indicating the participation of O2•− in the death process. (B) Preloaded MitoSOX parasites were exposed to the death stimuli (20 min), and this was fluorimetrically followed by MitoSOX oxidation (λex=10 nm and λem=580 nm). TcSODA overexpressers inhibited MitoSOX oxidation unambiguously indicating mitochondrial O2•− dependent MitoSOX oxidation. Adapted from (47).

Intracellular apoptotic amastigotes have been found in experimentally infected cardiomyocytes as well as in vivo in the heart tissue of infected mice (14, 15). Interactions of apoptotic parasites with immune cells may locally down regulate the host-inflammatory response with the concomitant production of anti-inflammatory cytokines (TGF-β), thus favoring parasite proliferation and transition to the chronic stage (22, 44). It has also been proposed that apoptosis enables the regulation of parasite densities in distinct host compartments, facilitating a sustained infection in the vertebrate host (67). Thus, interfering with the parasite apoptotic machinery may reveal new targets for drug design. The presence in T. cruzi of four FeSODs localized in different subcellular compartments argues in favor of a pivotal role of O2•− in parasite redox signaling.

Antioxidant Enzymes As Virulence Factors

T. cruzi consists of a mixed population of strains classified in two discrete typing units recently designated as T. cruzi I-VI (81), which circulate in the sylvatic and domestic cycles, respectively (63). The biochemical and genetic heterogeneity between strains is, in part, responsible for the diverse clinical manifestations of the disease, ranging from asymptomatic to severe cardiac and digestive presentations (31). The pathogenesis of CD depends on parasite and host factors that control virulence, tissue tropism, tissue damage, and ability to maintain long-term infections in the vertebrate host. A number of virulence factors have been identified for T. cruzi and include complement C2 receptor inhibitor trispanning (CRIT) protein (12), calreticulin (TcCRT) (56), gp35/50 (79), gp82 (61), cruzipain (35), oligopeptidase B (10), and transialidases (45), among others. Taking into account the establishment of a nitroxidative stress during CD (acute or chronic stages), the antioxidant armamentarium of T. cruzi becomes decisive. Several proteomic analyses have suggested the up-regulation of members of the T. cruzi antioxidant network (TcTS; TcMPX; TXN; FeSODA and TcAPX) in the infective metacyclic trypomastigote compared with the noninfective epimastigote stage (5, 43). Due to the fact that T. cruzi is not a clonal population, we search for the up-regulation of different components of the antioxidant network in several strains belonging to the major phylogenetic groups during the differentiation process to the infective metacyclic trypomastigotes. Our results show for all the analyzed strains an up-regulation of TcCPX, TcMPX, and TcTS protein content during metacyclogenesis, making this a general preadaptation process that allows T. cruzi to deal with the nitroxidative environment found in the vertebrate host (50). Most important, a positive association was found between virulence and the protein levels of antioxidant enzymes (TcCPX, TcMPX, and TcTS) in several T. cruzi strains, highlighting the interplay between the antioxidant enzyme network and host oxidative defense mechanisms (Table 1) (50). In accordance, strains of higher virulence showed an important heart inflammatory infiltrate with high parasitemias in the acute phase of CD. (Fig. 7A). At the cellular level, parasites that overexpressed TcCPX were resistant to macrophage killing due to peroxynitrite detoxification (Table 2) (1). Moreover, the overexpression of TcCPX in trypomastigotes augments virulence, as evidenced by a threefold increase in parasitemia with the presence of higher inflammatory infiltrates in the heart and skeletal muscle when compared with the wild strain (Fig. 7B). In this line, the experiments performed with genetically modified parasites fully recapitulated the association observed between the virulence and antioxidant enzyme content of T. cruzi wild strains (compare Fig. 7A and B) (1). These results reinforce the concept that the success of infection in the acute phase depends on parasite antioxidant enzyme levels. Whether FeSOD constitute a virulence factor for T. cruzi infection remains to be established and is currently under investigation in our laboratory. T. cruzi cytosolic FeSODB is particularly resistant to peroxinitrite inactivation, suggesting its participation mainly as an antioxidant defense enzyme, while mitochondrial FeSODA may act as an oxidative stress sensor participating in O2•—-mediated redox processes of cell signaling (Martinez, Piacenza, et al., unpublished results). Interestingly, highly virulent strains of T. cruzi showed less amastigote apoptotic death and higher proliferation rates than less virulent strains in cardiomyocyte infections (14). Taking into account that mitochondrial O2•− mediates programmed cell death in T. cruzi, we propose that FeSOD may also play a role in the pathogenesis of the disease.

Table 1.

Correlation Between Trypanosoma cruzi Enzyme Content in the Infective Metacyclic Stage and Parasitemia Elicited in Mice

Correlation is significant at the 0.001 level (two tailed).

TcMPX, T. cruzi mitochondrial tryparedoxin peroxidase; TcCPX, T. cruzi cytosolic tryparedoxin peroxidase; TcTS, T. cruzi trypanothione synthetase.

Adapted from Piacenza et al. (46)

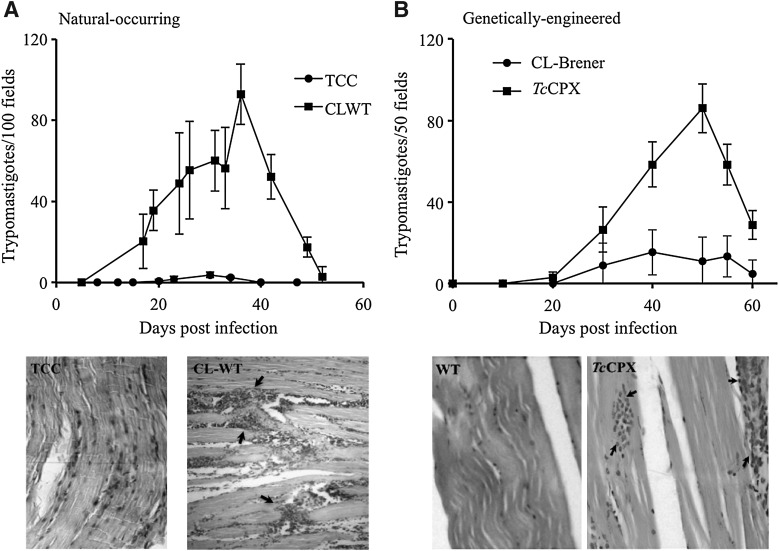

FIG. 7.

Elevated parasitemia and inflammatory infiltrates in experimentally infected animals elicited by natural and genetically modified T. cruzi strains with increased antioxidant enzyme levels. The behavior of natural attenuated (TCC) and virulent (CL-WT) T. cruzi strain (A) and that obtained by genetically modified CL_Brener (wild type, control) and TcCPX overexpressers (B) in experimental infections. Two-month-old Swiss mice were infected by an intraperitoneal inoculation with 1×103 complement-resistant metacyclic trypomastigote forms. Parasitemia was followed by parasite count number in blood-tail samples and results presented as trypomastigotes/100 fields (natural strains TCC and CL-WT) or trypomastigotes/50 fields (CL-Brener, TcCPX), and values are given as means±standard error of the mean. Histological H&E-stained heart tissue sections from mice inoculated with the attenuated and virulent strain (TCC and CL-WT; 25×magnification) and skeletal muscle tissue sections of mice inoculated with the genetically modified T. cruzi strain (CL-Brener, control, and TcCPX overexpressers; 40×magnification) were analyzed for the presence of immune infiltrates (shown with arrows), as previously adapted from Piacenza et al. and Alvarez et al. (1, 50).

Table 2.

Intraphagosomal Peroxynitrite Detoxification by Trypanosoma cruzi TcCPX Overexpressers

The load of T. cruzi amastigotes in the macrophage (J-774 line) culture was evaluated 24 h after infection with metacyclic trypomastigotes (parasite:macrophage ratio for infection 5:1). Data are mean±standard error of three independent experiments.

INF-γ/LPS was added 5 h before the infection.

p<0.01.

LPS, lipopolysaccharide.

Adapted from Alvarez et al. (1)

Concluding Remarks

T. cruzi antioxidant enzymes acting synergistically represent the first line of defense to cope with O2•−, H2O2, and ONOO− generated while infecting mammalian cells either in the acute and presumably in the chronic stage of the disease. Particularly interesting is the emerging evidence that the single T. cruzi mitochondrion can play a central role as a “powerhouse” of the reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, including O2•− and ONOO− (the latter arising from the combination of O2•− with mammalian host cell-derived •NO), when infecting non-phagocytic cells such as cardiomyocytes; these alterations in T. cruzi mitochondrion redox homeostasis and its modulation by mitochondrial antioxidant systems may facilitate the progression of a “low grade” infection to a chronic phase. Deciphering the relative role of different arms of the enzymatic antioxidant network in the various cellular compartments should be a part of future investigations. In summary, the assessment and definition of the contribution of the parasite antioxidant systems toward virulence and persistence could further define them as relevant targets for the development of new pharmacological strategies that treat CD, especially in the chronic stage.

Abbreviations Used

- BZ

benznidazole

- 6-CFDA

6-carboxy-fluorescein di-acetate

- CD

Chagas disease

- CO3·−

carbonate radical

- DMNQ

2,3-dimethoxy-1,4-naphthoquinone

- FHS

fresh human serum

- GSH

glutathione

- HIS

inactivated human serum

- IMM

inner mitochondrial membrane

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- NFX

nifurtimox

- ·NO

nitric oxide

- ·NO2

nitrogen dioxide

- NTRs

nitroreductases

- O2•−

superoxide radical

- ·OH

hydroxyl radical

- OMM

outer mitochondrial membrane

- ONOO−

peroxynitrite

- PPP

pentose phosphate pathway

- RSH-RSSR

reduced and oxidized low molecular or protein thiols

- TcCPX

T. cruzi cytosolic tryparedoxin peroxidase

- TcFeSOD

T. cruzi iron superoxide dismutase

- TcMPX

T. cruzi mitochondrial tryparedoxin peroxidase

- TcTS

T. cruzi trypanothione synthetase

- T(SH)2/TS2

reduced and oxidized trypanothione

- TXN

tryparedoxin

Acknowledgments

This work was support by grants from the National Institutes of Health, 1R01AI095173-01 (NIH, USA), and Universidad de la República (CSIC, Uruguay) to R.R. A.M. is supported by a fellowship of Agencia Nacional de Investigación e Innovación (ANII, Uruguay).

References

- 1.Alvarez MN. Peluffo G. Piacenza L. Radi R. Intraphagosomal peroxynitrite as a macrophage-derived cytotoxin against internalized Trypanosoma cruzi: consequences for oxidative killing and role of microbial peroxiredoxins in infectivity. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:6627–6640. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.167247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez MN. Piacenza L. Irigoin F. Peluffo G. Radi R. Macrophage-derived peroxynitrite diffusion and toxicity to Trypanosoma cruzi. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;432:222–232. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ameisen JC. Idziorek T. Billaut-Mulot O. Tissier JP. Potentier A. Ouaissi A. Apoptosis in a unicellular eukaryote (Trypanosoma cruzi): implications fot the evolutionary origin and role of programmed cell death in the control of cell proliferation, differentiation and survival. Cell Death Differ. 1995;2:285–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrade LO. Andrews NW. The Trypanosoma cruzi-host-cell interplay: location, invasion, retention. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:819–823. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atwood JA., 3rd Weatherly DB. Minning TA. Bundy B. Cavola C. Opperdoes FR. Orlando R. Tarleton RL. The Trypanosoma cruzi proteome. Science. 2005;309:473–476. doi: 10.1126/science.1110289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bachega JF. Navarro MV. Bleicher L. Bortoleto-Bugs RK. Dive D. Hoffmann P. Viscogliosi E. Garratt RC. Systematic structural studies of iron superoxide dismutases from human parasites and a statistical coupling analysis of metal binding specificity. Proteins. 2009;77:26–37. doi: 10.1002/prot.22412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baez A. Lo Presti MS. Rivarola HW. Mentesana GG. Pons P. Fretes R. Paglini-Oliva P. Mitochondrial involvement in chronic chagasic cardiomyopathy. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2011;105:239–246. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boiani M. Piacenza L. Hernandez P. Boiani L. Cerecetto H. Gonzalez M. Denicola A. Mode of action of nifurtimox and N-oxide-containing heterocycles against Trypanosoma cruzi: is oxidative stress involved? Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;79:1736–1745. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calcerrada P. Peluffo G. Radi R. Nitric oxide-derived oxidants with a focus on peroxynitrite: molecular targets,cellular responses and therapeutic implications. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:3905–3932. doi: 10.2174/138161211798357719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caler EV. Vaena de Avalos S. Haynes PA. Andrews NW. Burleigh BA. Oligopeptidase B-dependent signaling mediates host cell invasion by Trypanosoma cruzi. EMBO J. 1998;17:4975–4986. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.17.4975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cassina A. Radi R. Differential inhibitory action of nitric oxide and peroxynitrite on mitochondrial electron transport. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;328:309–316. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cestari Idos S. Krarup A. Sim RB. Inal JM. Ramirez MI. Role of early lectin pathway activation in the complement-mediated killing of Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol Immunol. 2009;47:426–437. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chandrasekar B. Melby PC. Troyer DA. Colston JT. Freeman GL. Temporal expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and inducible nitric oxide synthase in experimental acute Chagasic cardiomyopathy. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:925–934. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Souza EM. Araujo-Jorge TC. Bailly C. Lansiaux A. Batista MM. Oliveira GM. Soeiro MN. Host and parasite apoptosis following Trypanosoma cruzi infection in in vitro and in vivo models. Cell Tissue Res. 2003;314:223–235. doi: 10.1007/s00441-003-0782-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Souza EM. Nefertiti AS. Bailly C. Lansiaux A. Soeiro MN. Differential apoptosis-like cell death in amastigote and trypomastigote forms from Trypanosoma cruzi-infected heart cells in vitro. Cell Tissue Res. 2010;341:173–180. doi: 10.1007/s00441-010-0985-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denicola A. Rubbo H. Rodriguez D. Radi R. Peroxynitrite-mediated cytotoxicity to Trypanosoma cruzi. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;304:279–286. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dhiman M. Estrada-Franco JG. Pando JM. Ramirez-Aguilar FJ. Spratt H. Vazquez-Corzo S. Perez-Molina G. Gallegos-Sandoval R. Moreno R. Garg NJ. Increased myeloperoxidase activity and protein nitration are indicators of inflammation in patients with Chagas' disease. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2009;16:660–666. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00019-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dhiman M. Nakayasu ES. Madaiah YH. Reynolds BK. Wen JJ. Almeida IC. Garg NJ. Enhanced nitrosative stress during Trypanosoma cruzi infection causes nitrotyrosine modification of host proteins: implications in Chagas' disease. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:728–740. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Docampo R. Moreno SN. Free radical metabolism of antiparasitic agents. Fed Proc. 1986;45:2471–2476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durand JL. Mukherjee S. Commodari F. De Souza AP. Zhao D. Machado FS. Tanowitz HB. Jelicks LA. Role of NO synthase in the development of Trypanosoma cruzi-induced cardiomyopathy in mice. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:782–787. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrer-Sueta G. Radi R. Chemical biology of peroxynitrite: kinetics, diffusion, and radicals. ACS Chem Biol. 2009;4:161–177. doi: 10.1021/cb800279q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freire-de-Lima CG. Nascimento DO. Soares MB. Bozza PT. Castro-Faria-Neto HC. de Mello FG. DosReis GA. Lopes MF. Uptake of apoptotic cells drives the growth of a pathogenic trypanosome in macrophages. Nature. 2000;403:199–203. doi: 10.1038/35003208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fueller F. Jehle B. Putzker K. Lewis JD. Krauth-Siegel RL. High-throughput screening against the peroxidase cascade of African trypanosomes identifies antiparasitic compounds that inactivate tryparedoxin. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:8792–8802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.338285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta S. Bhatia V. Wen JJ. Wu Y. Huang MH. Garg NJ. Trypanosoma cruzi infection disturbs mitochondrial membrane potential and ROS production rate in cardiomyocytes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:1414–1421. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Igoillo-Esteve M. Cazzulo JJ. The glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase from Trypanosoma cruzi: its role in the defense of the parasite against oxidative stress. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2006;149:170–181. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Irigoin F. Cibils L. Comini MA. Wilkinson SR. Flohe L. Radi R. Insights into the redox biology of Trypanosoma cruzi: Trypanothione metabolism and oxidant detoxification. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:733–742. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Irigoin F. Inada NM. Fernandes MP. Piacenza L. Gadelha FR. Vercesi AE. Radi R. Mitochondrial calcium overload triggers complement-dependent superoxide-mediated programmed cell death in Trypanosoma cruzi. Biochem J. 2009;418:595–604. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ismail SO. Paramchuk W. Skeiky YA. Reed SG. Bhatia A. Gedamu L. Molecular cloning and characterization of two iron superoxide dismutase cDNAs from Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1997;86:187–197. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(97)00032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kierszenbaum F. Knecht E. Budzko DB. Pizzimenti MC. Phagocytosis: a defense mechanism against infection with Trypanosoma cruzi. J Immunol. 1974;112:1839–1844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krauth-Siegel RL. Bauer H. Schirmer RH. Dithiol proteins as guardians of the intracellular redox milieu in parasites: old and new drug targets in trypanosomes and malaria-causing plasmodia. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2005;44:690–715. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luquetti AO. Miles MA. Rassi A. de Rezende JM. de Souza AA. Povoa MM. Rodrigues I. Trypanosoma cruzi: zymodemes associated with acute and chronic Chagas' disease in central Brazil. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1986;80:462–470. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(86)90347-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Machado FS. Martins GA. Aliberti JC. Mestriner FL. Cunha FQ. Silva JS. Trypanosoma cruzi-infected cardiomyocytes produce chemokines and cytokines that trigger potent nitric oxide-dependent trypanocidal activity. Circulation. 2000;102:3003–3008. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.24.3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mateo H. Marin C. Perez-Cordon G. Sanchez-Moreno M. Purification and biochemical characterization of four iron superoxide dismutases in Trypanosoma cruzi. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2008;103:271–276. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762008000300008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maya JD. Cassels BK. Iturriaga-Vasquez P. Ferreira J. Faundez M. Galanti N. Ferreira A. Morello A. Mode of action of natural and synthetic drugs against Trypanosoma cruzi and their interaction with the mammalian host. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2007;146:601–620. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meirelles MN. Juliano L. Carmona E. Silva SG. Costa EM. Murta AC. Scharfstein J. Inhibitors of the major cysteinyl proteinase (GP57/51) impair host cell invasion and arrest the intracellular development of Trypanosoma cruzi in vitro. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;52:175–184. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90050-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mejia-Jaramillo AM. Fernandez GJ. Palacio L. Triana-Chavez O. Gene expression study using real-time PCR identifies an NTR gene as a major marker of resistance to benznidazole in Trypanosoma cruzi. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:169. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Michailowsky V. Silva NM. Rocha CD. Vieira LQ. Lannes-Vieira J. Gazzinelli RT. Pivotal role of interleukin-12 and interferon-gamma axis in controlling tissue parasitism and inflammation in the heart and central nervous system during Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1723–1733. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63019-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moreno DM. Marti MA. De Biase PM. Estrin DA. Demicheli V. Radi R. Boechi L. Exploring the molecular basis of human manganese superoxide dismutase inactivation mediated by tyrosine 34 nitration. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;507:304–309. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Munoz-Fernandez MA. Fernandez MA. Fresno M. Synergism between tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma on macrophage activation for the killing of intracellular Trypanosoma cruzi through a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:301–307. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Naviliat M. Gualco G. Cayota A. Radi R. Protein 3-nitrotyrosine formation during Trypanosoma cruzi infection in mice. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2005;38:1825–1834. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2005001200011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nogueira FB. Krieger MA. Nirde P. Goldenberg S. Romanha AJ. Murta SM. Increased expression of iron-containing superoxide dismutase-A (TcFeSOD-A) enzyme in Trypanosoma cruzi population with in vitro-induced resistance to benznidazole. Acta Trop. 2006;100:119–132. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oza SL. Tetaud E. Ariyanayagam MR. Warnon SS. Fairlamb AH. A single enzyme catalyses formation of Trypanothione from glutathione and spermidine in Trypanosoma cruzi. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:35853–35861. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204403200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parodi-Talice A. Monteiro-Goes V. Arrambide N. Avila AR. Duran R. Correa A. Dallagiovanna B. Cayota A. Krieger M. Goldenberg S. Robello C. Proteomic analysis of metacyclic trypomastigotes undergoing Trypanosoma cruzi metacyclogenesis. J Mass Spectrom. 2007;42:1422–1432. doi: 10.1002/jms.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peluffo G. Piacenza L. Irigoin F. Alvarez MN. Radi R. L-arginine metabolism during interaction of Trypanosoma cruzi with host cells. Trends Parasitol. 2004;20:363–369. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pereira ME. Zhang K. Gong Y. Herrera EM. Ming M. Invasive phenotype of Trypanosoma cruzi restricted to a population expressing trans-sialidase. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3884–3892. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3884-3892.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piacenza L. Alvarez MN. Peluffo G. Radi R. Fighting the oxidative assault: the Trypanosoma cruzi journey to infection. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2009;12:415–421. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Piacenza L. Irigoin F. Alvarez MN. Peluffo G. Taylor MC. Kelly JM. Wilkinson SR. Radi R. Mitochondrial superoxide radicals mediate programmed cell death in Trypanosoma cruzi: cytoprotective action of mitochondrial iron superoxide dismutase overexpression. Biochem J. 2007;403:323–334. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Piacenza L. Peluffo G. Alvarez MN. Kelly JM. Wilkinson SR. Radi R. Peroxiredoxins play a major role in protecting Trypanosoma cruzi against macrophage- and endogenously-derived peroxynitrite. Biochem J. 2008;410:359–368. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Piacenza L. Peluffo G. Radi R. L-arginine-dependent suppression of apoptosis in Trypanosoma cruzi: contribution of the nitric oxide and polyamine pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7301–7306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121520398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Piacenza L. Zago MP. Peluffo G. Alvarez MN. Basombrio MA. Radi R. Enzymes of the antioxidant network as novel determiners of Trypanosoma cruzi virulence. Int J Parasitol. 2009;39:1455–1464. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pineyro MD. Pizarro JC. Lema F. Pritsch O. Cayota A. Bentley GA. Robello C. Crystal structure of the tryparedoxin peroxidase from the human parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. J Struct Biol. 2005;150:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Prathalingham SR. Wilkinson SR. Horn D. Kelly JM. Deletion of the Trypanosoma brucei superoxide dismutase gene sodb1 increases sensitivity to nifurtimox and benznidazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:755–758. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01360-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Quijano C. Hernandez-Saavedra D. Castro L. McCord JM. Freeman BA. Radi R. Reaction of peroxynitrite with Mn-superoxide dismutase. Role of the metal center in decomposition kinetics and nitration. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11631–11638. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009429200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Radi R. Nitric oxide, oxidants, and protein tyrosine nitration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4003–4008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307446101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Radi R. Rodriguez M. Castro L. Telleri R. Inhibition of mitochondrial electron transport by peroxynitrite. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;308:89–95. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ramirez G. Valck C. Molina MC. Ribeiro CH. Lopez N. Sanchez G. Ferreira VP. Billetta R. Aguilar L. Maldonado I. Cattan P. Schwaeble W. Ferreira A. Trypanosoma cruzi calreticulin: a novel virulence factor that binds complement C1 on the parasite surface and promotes infectivity. Immunobiology. 2011;216:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rassi A., Jr. Rassi A. Marin-Neto JA. Chagas disease. Lancet. 2010;375:1388–1402. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60061-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Repetto Y. Opazo E. Maya JD. Agosin M. Morello A. Glutathione and trypanothione in several strains of Trypanosoma cruzi: effect of drugs. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;115:281–285. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(96)00112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Robinson KM. Janes MS. Pehar M. Monette JS. Ross MF. Hagen TM. Murphy MP. Beckman JS. Selective fluorescent imaging of superoxide in vivo using ethidium-based probes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15038–15043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601945103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rubbo H. Denicola A. Radi R. Peroxynitrite inactivates thiol-containing enzymes of Trypanosoma cruzi energetic metabolism and inhibits cell respiration. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;308:96–102. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ruiz RC. Favoreto S., Jr. Dorta ML. Oshiro ME. Ferreira AT. Manque PM. Yoshida N. Infectivity of Trypanosoma cruzi strains is associated with differential expression of surface glycoproteins with differential Ca2+ signalling activity. Biochem J. 1998;330(Pt 1):505–511. doi: 10.1042/bj3300505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schofield CJ. Kabayo JP. Trypanosomiasis vector control in Africa and Latin America. Parasit Vectors. 2008;1:24. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-1-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Souto RP. Fernandes O. Macedo AM. Campbell DA. Zingales B. DNA markers define two major phylogenetic lineages of Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;83:141–152. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(96)02755-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Temperton NJ. Wilkinson SR. Meyer DJ. Kelly JM. Overexpression of superoxide dismutase in Trypanosoma cruzi results in increased sensitivity to the trypanocidal agents gentian violet and benznidazole. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;96:167–176. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00127-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thomson L. Gadelha FR. Peluffo G. Vercesi AE. Radi R. Peroxynitrite affects Ca2+ transport in Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1999;98:81–91. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00149-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Trujillo M. Budde H. Pineyro MD. Stehr M. Robello C. Flohe L. Radi R. Trypanosoma brucei and Trypanosoma cruzi tryparedoxin peroxidases catalytically detoxify peroxynitrite via oxidation of fast reacting thiols. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:34175–34182. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404317200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.van Zandbergen G. Luder CG. Heussler V. Duszenko M. Programmed cell death in unicellular parasites: a prerequisite for sustained infection? Trends Parasitol. 2010;26:477–483. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wen JJ. Dhiman M. Whorton EB. Garg NJ. Tissue-specific oxidative imbalance and mitochondrial dysfunction during Trypanosoma cruzi infection in mice. Microbes Infect. 2008;10:1201–1209. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wen JJ. Garg NJ. Mitochondrial generation of reactive oxygen species is enhanced at the Q(o) site of the complex III in the myocardium of Trypanosoma cruzi-infected mice: beneficial effects of an antioxidant. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2008;40:587–598. doi: 10.1007/s10863-008-9184-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wilkinson SR. Bot C. Kelly JM. Hall BS. Trypanocidal activity of nitroaromatic prodrugs: current treatments and future perspectives. Curr Top Med Chem. 2011;11:2072–2084. doi: 10.2174/156802611796575894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wilkinson SR. Kelly JM. Trypanocidal drugs: mechanisms, resistance and new targets. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2009;11:e31. doi: 10.1017/S1462399409001252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wilkinson SR. Meyer DJ. Taylor MC. Bromley EV. Miles MA. Kelly JM. The Trypanosoma cruzi enzyme TcGPXI is a glycosomal peroxidase and can be linked to trypanothione reduction by glutathione or tryparedoxin. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:17062–17071. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111126200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wilkinson SR. Obado SO. Mauricio IL. Kelly JM. Trypanosoma cruzi expresses a plant-like ascorbate-dependent hemoperoxidase localized to the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13453–13458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202422899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wilkinson SR. Prathalingam SR. Taylor MC. Ahmed A. Horn D. Kelly JM. Functional characterisation of the iron superoxide dismutase gene repertoire in Trypanosoma brucei. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:198–209. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wilkinson SR. Taylor MC. Horn D. Kelly JM. Cheeseman I. A mechanism for cross-resistance to nifurtimox and benznidazole in trypanosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5022–5027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711014105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wilkinson SR. Taylor MC. Touitha S. Mauricio IL. Meyer DJ. Kelly JM. TcGPXII, a glutathione-dependent Trypanosoma cruzi peroxidase with substrate specificity restricted to fatty acid and phospholipid hydroperoxides, is localized to the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochem J. 2002;364:787–794. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wilkinson SR. Temperton NJ. Mondragon A. Kelly JM. Distinct mitochondrial and cytosolic enzymes mediate trypanothione-dependent peroxide metabolism in Trypanosoma cruzi. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8220–8225. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.8220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yamakura F. Taka H. Fujimura T. Murayama K. Inactivation of human manganese-superoxide dismutase by peroxynitrite is caused by exclusive nitration of tyrosine 34 to 3-nitrotyrosine. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14085–14089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yoshida N. Mortara RA. Araguth MF. Gonzalez JC. Russo M. Metacyclic neutralizing effect of monoclonal antibody 10D8 directed to the 35- and 50-kilodalton surface glycoconjugates of Trypanosoma cruzi. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1663–1667. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.6.1663-1667.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhao H. Kalivendi S. Zhang H. Joseph J. Nithipatikom K. Vasquez-Vivar J. Kalyanaraman B. Superoxide reacts with hydroethidine but forms a fluorescent product that is distinctly different from ethidium: potential implications in intracellular fluorescence detection of superoxide. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34:1359–1368. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00142-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zingales B. Andrade SG. Briones MR. Campbell DA. Chiari E. Fernandes O. Guhl F. Lages-Silva E. Macedo AM. Machado CR. Miles MA. Romanha AJ. Sturm NR. Tibayrenc M. Schijman AG. Second Satellite M. A new consensus for Trypanosoma cruzi intraspecific nomenclature: second revision meeting recommends TcI to TcVI. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104:1051–1054. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762009000700021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]