Abstract

We rarely, if ever, repeatedly encounter exactly the same situation. This makes generalization crucial for real world decision making. We argue that categorization, the study of generalizable representations, is a type of decision making, and that categorization learning research would benefit from approaches developed to study the neuroscience of decision making. Similarly, methods developed to examine generalization and learning within the field of categorization may enhance decision making research. We first discuss perceptual information processing and integration, with an emphasis on accumulator models. We then examine learning the value of different decision making choices via experience, emphasizing reinforcement learning modeling approaches. Next we discuss how value is combined with other factors in decision making, emphasizing the effects of uncertainty. Finally, we describe how a final decision is selected via thresholding processes implemented by the basal ganglia and related regions. We also consider how memory related functions in the hippocampus may be integrated with decision making mechanisms and contribute to categorization.

There has been a recent explosion of interest in decision making mechanisms across fields in neuroscience, marked by rapid development of new computational and experimental approaches (Gold and Shadlen, 2007). However, research using neuroscience methods has often been limited to simplified tasks without the requirement to generalize to new situations. Yet even seemingly simple decisions require generalization -- it is extremely rare that we repeatedly encounter identical situations. Therefore, incorporating theories of generalization developed in the field of categorization and category learning may help to significantly advance the field of decision making. Conversely, categorization theories have mainly focused on the representation of category structure at the expense of considering many other factors such as underlying perceptual information processing, value, and response selection. For both theoretical and pragmatic reasons, we argue that categorization is a type of decision making, and that the basic mechanisms involved in simple decision making will be utilized for categorization as well.

The recent increase in interest in decision making comes from the convergence of a number of trends across different fields. Behavioral neuroscientists studying basic perceptual phenomena became interested in the “next step” beyond simple perception: deciding what is being perceived (Shadlen and Newsome, 2001; Sugrue et al., 2005). Ethologists increasingly appreciated that even seemingly simple behaviors are contextually dependent, and that the organism must in effect “decide” which is appropriate; for example, when hearing a mating call a frog must select whether to respond via an approach behavior (Hoke et al., 2008). Behavioral economists became interested in studying the neural basis of economic decision making, resulting in the field now called “neuroeconomics” (Loewenstein et al., 2008). Cognitive neuroscientists emphasized the importance of decision making in mediating between basic perceptual and memory functions and behavioral choice, and the major role of frontoparietal systems in doing so (Banich et al., 2009). Neuropsychologists showed the serious real life decision impairments suffered by those with damage to frontoparietal systems (Koenigs et al., 2007; Rahman et al., 2001; Damasio, 1994; Ernst and Paulus, 2005). And in cognitive psychology, there was increasing appreciation that even seemingly simple cognitive processes like perception and recognition memory require decision making (Estes, 2002; Gardiner et al., 2002).

We begin by proposing working definitions of decision making, categorization, and generalization. We then discuss several ways in which decision making research can inform categorization and vice versa. First are mechanisms involving perception; we will focus our discussion on recent developments in the use of accumulator models in processing perceptual information. Next are mechanisms involved in learning the value of the different decision options: we will focus on the recent adaptation of reinforcement learning models to neuroscience studies of decision making. Then there are choice mechanisms that integrate the value of options with other factors; here we will emphasize the role of uncertainty in decision making. Finally, we’ll discuss mechanisms of thresholding and selection. We will also discuss how additional cognitive and neural systems, may contribute to decision making and categorization. We will focus on one such system, the medial temporal lobe system underlying memory processing. We conclude with a brief discussion of other systems that may be involved in categorization, including those involved in emotion and amodal conceptual processing, and point out future directions for research in these areas.

Decision making and Categorization: Definitions and Intersections

In this section working definitions of decision making and categorization are proposed. The similarity between decision making and categorization is apparent if one compares the task demands of a typical laboratory decision making task with those of a typical categorization task. In simple economic decision making (Corrado et al., 2008) tasks subjects view a stimulus (e.g., a slot machine), choose whether or not to gamble, and are given information about how much money is won or lost. In simple categorization the subject views a stimulus, indicates its category membership, and receives feedback (Seger, 2009). These tasks have many similarities: viewing a stimulus, making a decision and response indicating the decision, and receiving feedback about whether the decision was correct or not. From this perspective it is clear that regardless of what the tasks are called there is much overlap between decision making and categorization in perceptual, cognitive, and motor processes recruited during both types of tasks.

More formally, decision making requires isolating a variety of options. Each of these options then must be evaluated, i.e. somehow scored and/or ranked. Finally one option must be selected. Decisions can take place at a variety of levels of complexity and hierarchy. Simple decisions involve the application of criteria to perceptual and/or mnemonic contents resulting in evaluative judgments: “The stimulus is red”, “This is a slot machine worth gambling on” or “My memory of the event was that it happened in the classroom”. More complex decisions integrate more information, to arrive at a course of action: The decision to buy a particular stock, or to ask a particular person out on a date.

Likewise, categorization requires identifying a number of candidate categories. Each of these options then must be evaluated, or scored, and finally one category must be selected. These definitions of decision making and categorization are to this point identical. However categorization works on generalizable representations, and it is generalization that is the key distinction between them. Categories allow the organism to evaluate a stimulus or situation in terms of its membership in a group, category, or conceptual structure. Like decisions, categorization also takes place at a variety of levels. Simple categorization involves identifying the appropriate group or category for a particular item based on past experience with similar items. More complex forms of categorization can incorporate a more complex model of the preexisting world, or involve alternate goals for categorization beyond simple grouping, such as making inferences on the basis of category membership. In order to unite categorization and decisions, which we believe is necessary for the ecological validity of both, we must reexamine how items and categories are related. To keep the discussion tractable, we will focus on relatively simple decision making and categorization tasks.

Generalization

In the previous section we argued that the critical difference between seemingly simple decision making and categorization is generalization. Simple decision making tasks avoid generalization by repeating the same stimuli across trials; in contrast, categorization tasks require subjects to apply their knowledge to new stimuli. In addressing the question of generalization, we will take a broad approach: our definition is that generalization is any extension to a stimulus that is novel or changed in any way. In this section we divide generalization into 3 levels, discuss some general computational constraints affecting generalization, and introduce the main models of category representation and generalization that have been developed in cognitive psychology and machine learning.

Human generalization exists on a broad scale. Our operational definition that generalization is any extension to a stimulus that is novel or changed in any way includes very small changes as well as larger, more abstract changes. We note here three different levels of generalization that may be particularly relevant for characterizing the limits of different neural systems. A minimum level of generalization is the ability to adapt to very small changes in a stimulus, such as relative size, orientation, and to ignore irrelevant perceptual noise in processing repeated items. Even two apparently identical stimuli will not be processed identically because they will be accompanied by different random noise in the perceptual system (Ashby and Townsend, 1986). Classification tasks or arbitrary categorization tasks, which involve making category judgments on the same set of stimuli repeatedly (Seger and Miller, 2010), require only this minimal sense of generalization. Classification tasks are intermediate between decision making tasks and full categorization tasks, since aside from their generalization demands they are closely matched on other task demands. Furthermore, classification tasks have important real world analogs in learning in situations in which stimuli are arbitrarily assigned to groups; for example, learning which of a large group of students are in the morning section of a course, and which in the afternoon section.

A second level of generalization can be thought of as generalizing to items closely related to previously studied items; these items would be those within or very close to the area of perceptual or feature space in which previously studied stimuli were located. This is the most typically studied level of generalization. A final level is to extend the learned knowledge to stimuli that are outside the studied perceptual space. Some argue that this level of generalization requires additional analogical reasoning or rule-based processing (Casale et al., 2012; Snyder and Munakata, 2010).

Characterizing generalization has been the primary focus of most theories of category learning. Mathematical psychologists have argued that category evaluation is based on similarity measures, typically formulated as different ways of quantifying degree of perceptual overlap or distance. Tversky (1977) identified limitations of similarity based on simple metric data such as distances in a physically defined perceptual space, and instead proposed an abstract feature based approach in which similarity was based on the degree of shared features across items. Shepard (1987) argued that when stimuli are represented in psychological space (on the basis of perceived similarity or generalization) rather than in a physical metric space that generalization always follows an exponential gradient.

By the 1980s researchers had proposed several different potential category learning mechanisms. The controversy over whether all categorization can be explained by a single one of these approaches, or whether there might be multiple category learning systems that each represent categories in a different way and use different generalization algorithms continues to this day. The most prominent opposing theories (see Ashby and Maddox, 2005, for a review) are exemplar models, which represent categories as a collection of individual items; prototype models, in which categories are represented as the average or prototypical member; decision bound models, which posit that categories are represented in terms of a boundary in some perceptual space; and rule based models, which represent categories in terms of a verbalizable rule. Generalization to novel stimuli in decision bound and rule based models is straightforward and deterministic, based on which side of the bound the stimulus is located, or whether stimulus meets the conditions of the rule. Prototype and exemplar models are probabilistic. In prototype models categorization is based on distance from the prototype. Exemplar-based models support generalization through explicitly defined similarity measures that compare the current exemplar to previously observed examples.

Since their introductions, many of these modeling approaches have been hybridized to improve performance. Some hybrid models are an explicit combination of two or more different types of representation, such as ATRIUM and RULEX which combine exemplars and rules (Nosofsky et al., 1994; Erickson and Kruschke, 1998). Others hybrid models use flexible learning methods that allow for learning at different levels of generality and specificity. One way of looking at exemplar and prototype models is as extremes along a continuum, with prototype models defining a single representation to encompass all items, and exemplar models having a separate representation for each item (Ashby and Alfonso-Reese, 1995). Love and colleagues’ SUSTAIN model (Love et al., 2004) forms “clustered” representations that can flexibly represent commonalities across stimuli at a number of levels, with some clusters in effect representing individual exemplars (particularly for unusual members), and other clusters in effect representing averages or prototypes. DIVA uses principle components analysis to identify critical features and an autoencoder artificial neural network to learn to associate stimuli with categories (Kurtz, 2007).

Statistical learning algorithms developed in the field of machine learning have promise for characterizing human categorization. Kernel methods may provide a particularly powerful approach to extracting critical features from exemplars to support generalization (Jäkel et al., 2009). Kernels are flexible similarity metrics that can be applied to a variety of stimulus dimensions (e.g., color, spatial frequency, etc), and which can interact in a hierarchical manner, with kernels representing simpler features providing input to kernels representing more complex features (Serre et al., 2007). The potential for kernel approaches for characterizing categorization and generalization in neural regions is supported by research that has successfully derived kernel representations from neural data in areas V1 and V2 (Willmore et al., 2010).

Another set of approaches, often termed rational models, address the problem of categorization at the normative level rather than the procedural level. These models are based on the key insight of Bayesian statistics that optimal probabilistic inference combines knowledge of the prior probability with knowledge of conditional probability. In categorization, this means that judgments of category membership should be based on the overall probability that stimuli belong to each category along with conditional feature probability within each category; for example, for the feature “yellow”, the observed probability that members of category A are yellow. This normative Bayesian approach has been implemented in category learning models using nonparametric Bayesian statistics (Anderson, 1991) or Monte Carlo approaches (Sanborn et al., 2010). Because these models are normative and computationally abstract, it can be unclear how or whether they might be implemented in terms of psychological and/or neural processes.

Perceptual Processes: Information Accumulation

The first step in simple decision making, including simple categorization, is the basic perceptual processing of the stimulus. In this section we discuss the challenges faced by perceptual systems, in particular the visual system, in analyzing information in such a way that the organism can utilize it for a wide variety of processes. We argue that the combination of specific representations in perceptual cortex and representations that summarize this information for particular functions in higher order regions allows perceptual knowledge to be used for multiple purposes. We will focus on a class of models known as accumulator models that can effectively summarize such information. A broad treatment of all the ways that category learning may affect perceptual cortical processing is beyond the scope of this review. The reader is referred instead to Seger and Miller (2010) for a review, and Folstein et al. (2012) for recent insights into what kinds of categories do and do not lead to cortical plasticity.

The picture that is emerging from the study of visual cortex is that, at least in the adult organism1, visual cortex is primarily focused on providing detailed representations of individual items. Perceptual cortex has a certain degree of tolerance: that is, it can adapt to changes in size or position (Li and DiCarlo, 2010; Li et al., 2007). Electrophysiological studies measuring individual neuron activity to repeated similar stimuli often find sharpening across repeated training, in which the activity of a subset of neurons increases while the majority decreases (McMahon and Olson, 2007). Tolerance and sharpening help to minimize the effects of perceptual noise. Tolerance can be seen as a limited form of generalization; however it is insufficient for making many decisions about the item, including view invariance for recognition (Yamashita et al., 2010), and while it may contribute to categorization through improved visual processing of relevant features, it cannot be the sole process involved (Freedman et al., 2003; Sigala and Logothetis, 2002). There needs to be a subsequent, more generalizable, mechanism.

Many perceptual tasks require integration of perceptual information across time. The most common approach to modeling these summation processes are the accumulator or drift diffusion models, which originated in mathematical psychology in the 1960s (Audley and Pike, 1965) and were developed by a number of researchers including Ratcliff (1978) and Townsend and Ashby (1983). Accumulator models presume that information about a stimulus is incrementally summed across time, until sufficient information is present for a decision. The key parameters in an accumulator model are the rate of evidence accumulation or integration (called drift rate when modeled as a continuous process), and the response criterion setting (sometimes referred to as boundary separation). We focus on accumulation in this section, and will discuss response criterion in “Thresholding and Action” below; although both aspects are commonly modeled together, there is evidence that they recruit different neural systems.

The neuroscience paradigm most often used to study information accumulation in primates is the coherent motion detection task. In this task, the subject views a display of multiple moving dots; although each dot moves in a different direction, there is a net direction of movement (e.g., leftward or rightward), and the task of the subject is to decide what that direction is. This task has the advantages that information is easily manipulated, that information is accumulated across time slowly enough to allow researchers to calculate the slopes of accumulation curves and relate them to electrophysiological measures on a scale of 100s of milliseconds, and that the primary perceptual processing pathway for motion is well known and relatively circumscribed to a region known as MT or V5 (Shadlen and Newsome, 2001). Individual cells within MT have firing rates that reflect local aspects of motion; across cells the net activity (calculated as a population vector) closely tracks the net motion, but is not calculated within MT itself. Instead, a separate region in the parietal lobe referred to as LIP has cells that are active to the summed motion information (Shadlen and Newsome, 2001). Activity in LIP in the coherent dot motion perception task is well characterized by accumulator models (Churchland et al., 2011; Gold et al., 2010; Gold and Shadlen, 2007).

FMRI studies find that accumulation of information about dot movement recruits regions in the human intraparietal sulcus, which is homologous to LIP (Kayser et al., 2010a, 2010b). This method has been extended to other perceptual domains, including recognition of simple line drawings (Ploran et al., 2007), detection of net orientation of a set of stimuli (de Lange et al., 2011) and discrimination between two ambiguous visual object classes, e.g. faces versus houses (Heekeren et al., 2004). Evidence accumulation recruits the same neural region for different responses (e.g. hand movements versus saccades), indicating that it is relatively abstract and not tied to specific motor effectors (Ho et al., 2009; Liu and Pleskac, 2011). FMRI studies using a variety of tasks have found multiple cortical regions that are sensitive to the accumulation of information; in addition to the parietal lobe, these include the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Domenech and Dreher, 2010; Ploran et al., 2007), insula (Ho et al., 2009), and higher order visual cortex in the inferior temporal lobe (Ploran et al., 2007; Ploran et al., 2011).

Development of these novel fMRI scanning procedures is still in the early stages, but future research could extend paradigms developed for simple perceptual decision making to examine activity as subjects accumulate information necessary to categorize. As one example, subjects could be trained to categorize stimuli in which category membership is a function of multiple features, and accumulation could be examined as features are presented across time. It might further be possible to compare whether different types of features necessary for categorization recruit different accumulation methods.

One particularly important application would be extending these methods to examine generalization and extension of category knowledge to novel stimuli. It is an open question how generalization processes may be incorporated into accumulator models in order to support categorization and categorization learning. The primary development of accumulator models has been for decision making tasks in well-known domains with discrete, well-defined stimulus types (e.g. leftward versus rightward motion; houses versus faces). To account for categorization using accumulation approaches it will be useful to (1) adapt these models and experimental approaches to situations in which the stimuli are defined as a class (category) rather than individuals, (2) account for the dynamic development of new categories across learning, and (3) account for transfer to completely novel stimuli both within the experienced range, as well as extrapolation to stimuli outside the range. Some research has begun to address the first two points. Freedman and Assad (2006, 2009, 2011) examined the establishment of response categories in the coherent dot motion task by implementing a decision bound such that directions of movement on different sides of the bound were associated with different responses. Further research found that activity changes in LIP preceded those in PFC, which is consistent with an accumulation account and inconsistent with LIP activity being a result of top-down processing from PFC (Swaminathan and Freedman, 2012). However all these studies of LIP use motion as the primary underlying perceptual stimulus. It is unclear how this and other neural regions might be recruited for accumulating information about arbitrary or novel categories that are not based on a simple perceptual structure.

Research in cognitive psychology gives insights into how information accumulation and categorization may be combined at the computational level; the Exemplar Based Random Walk model of (Nosofsky and Palmeri, 1997) categorizes new stimuli by first retrieving similar previously learned exemplars from memory, and then combining these exemplar-match signals via an accumulator mechanism. However, there is still a conceptual gap between the specific accumulation mechanism in LIP, and the more general purpose, flexible mechanisms that will be necessary for categorization learning more broadly. As described above, accumulation related brain activations have been identified in many cortical areas in humans, including frontal, insular, and parietal regions. The prefrontal-inferior parietal cortices are known to be able to implement strategies flexibly; for example, individual PFC neurons can switch from representing one category to another category when the situation demands it (Cromer et al., 2010). It is an open question whether these systems are equally as flexible in switching between accumulation tasks. Future research may extend and adapt the fMRI methods already developed to examine accumulation of information in perceptual decision making (Ploran et al., 2007; Ploran et al., 2011). For example, studies could examine flexibility by having subjects switch between perceptual decision making tasks (e.g., switch between dot movement and color identification tasks), or between perceptual identification and categorization tasks. An additional important question to examine will be the executive functions that control this switching, including possible commonalities with mechanisms recruited for switching between strategies (Yoshida et al., 2009), updating contents of working memory (Bledowski et al., 2010), and selective attention (Hedden and Gabrieli, 2010; Wager et al., 2005).

Learning Reward Values Via Reinforcement Learning

Most economic decision making theories entail two steps: A first step (often referred to as valuation) in which the subject calculates the individual values of different options, or the relative value of the options, and a second step (often referred to as choice) in which the subject combines these value estimates with other factors to make the decision (Vlaev et al., 2011; Kable and Glimcher, 2009; Corrado et al., 2008; Rangel et al., 2008). In this section we discuss recent computational and empirical investigations of neural representations of value; choice is the focus of the following section. We focus on reinforcement learning theory (Sutton and Barto, 1998), which provides a way to calculate value that is normative (i.e. in some way theoretically optimal; Waelti et al., 2001), quantitative, and mechanistic. Reinforcement learning also is well established as an accurate model of dopamine neuron activity in the brain, known as the reward prediction error hypothesis of phasic dopamine function (Fiorillo et al., 2003; Montague et al., 2006; Dayan and Niv, 2008).

Broadly speaking, reinforcement learning methods calculate value (the total expected future reward associated with taking a particular action in a particular situation or state) via a prediction error (the difference between the predicted outcome and the received reward). After each trial or time step, the prediction error is used to update estimate of value. The models use an abstraction termed a “state” as the basic entity for which value is calculated; a state generally reflects the current context and possible actions to be taken. For example, in a categorization task a state might consist of the stimulus and the associated category response. This updated value is used the next time an identical trial-type (or state) occurs. In human studies the update magnitude is generally controlled by a single free parameter, often represented as alpha or the learning rate. There are three variants of reinforcement learning that have been used most frequently in the fields of Psychology and Neuroscience. The first to be developed was the Rescorla-Wagner rule (developed in the field of animal behavior to describe classical conditioning), which calculates prediction error as the difference between the current reward (coded as either 1 or 0) and the current value (Gläscher and Büchel, 2005). However, this rule cannot account for higher order conditioning. Two common variants that can account for higher order conditioning are Q-learning and SARSA. Q-learning calculates values for specific states and actions and always chooses the one maximum value for update comparisons; in contrast, SARSA considers only the difference between the current and past values for the current state-action pair. Although SARSA can lead to ‘matching behaviors’ which are non-optimal for reward maximization, SARSA models were shown to better reflect decision-making as well as phasic dopaminergic activity in a monkey model (Morris et al., 2006). Reinforcement learning models can account for dopamine neuron activity with a high degree of accuracy; dopamine neurons thus can be thought of as a neural signal indicating prediction error (Fiorillo et al., 2003; Montague et al., 2006).

Most of the reinforcement modeling approaches discussed here originated and were behaviorally validated in studies of non-human animals with a focus on primary (food, water) and conditioned secondary (simple tones or shapes) rewards. However, the concept of reward has been broadened substantially in human subjects to include a range of feedback types. Examples include money (Kim et al., 2011; Knutson et al., 2005), social reputation (Izuma et al., 2008; Phan et al., 2010) and the types of cognitive feedback used in most behavioral studies of categorization (e.g., the words “right” or “wrong”, or a word or symbol indicating the correct category; Aron et al., 2004). Both traditional and cognitive rewards activate the dopaminergic midbrain and the ventral striatum, as recently reviewed by Montague et al. (2006). Furthermore, reward systems are activated by factors other than reward as well, including stimulus novelty (Blatter and Schultz, 2006) and salience, both in the sense of wanting or desirability (Berridge, 2007) and behavioral relevance (Zink et al., 2003; Bromberg-Martin et al., 2010). Reinforcement learning theory has been extended to try to account for these effects (Kakade and Dayan, 2002). Recent work has also shown reward-system activity in response to unrewarding cognitive factors such as unrewarded goal achievement (Tricomi and Fiez, 2008) prediction error based on confidence (Daniel and Pollmann, 2012) as well as imagined (or ‘fictive’) rewards (Lohrenz et al., 2007). Thus, the resulting calculations of value as reward prediction, and prediction error, are not narrowly limited to particular types of reward but instead are suitable for learning in a broad variety of situations even when overt reward is not present. This of course is the situation in many laboratory tasks of categorization learning, in which subjects receive only cognitive feedback.

Reinforcement learning models generally assume that learning takes place as a Markov decision process, meaning they assume the model can be represented as a series of discrete states where the next state is a function only of the current state and the current stimuli representing the environment. This simplification has an immediate consequence regarding category learning. The value of available options is conditionalized on the current state; similar yet not identical states do not inherit value. For that and other more practical reasons, generalization is a significant problem for reinforcement learning models. The concept of a “state” may be a convenient but misleading abstraction. Very little is known about how the brain generates states and relates them to behavioral options (Smaldino and Richerson, 2012), how generalizable states may or may not be, or even whether states are neurally computed as Markov processes. Empirical research indicates that states are not completely independent; humans generalize between states when they have similarities such as overlapping stimulus features (Kahnt et al., 2010), indicating the necessity of incorporating a model of generalization into reinforcement learning models of brain function (for an initial theoretical attempt see Kakade and Dayan, 2002). The development of a more realistic approach to modeling states is an active area of research, including methods for creating new states when needed (Gershman et al., 2010; Redish et al., 2007) and ways of disambiguating perceptually overlapping states (Gureckis and Love, 2009).

Another promising approach is recent development of models that combine standard reinforcement learning with explicit knowledge representations, sometimes termed model-based, referring to the subject acting on a mental model rather than on model-free reinforcement based knowledge (Daw et al., 2011; Gläscher et al., 2010). This research may be synergistic with category learning research that examines how cognitive theories interact with other sources of category information (Luhmann et al., 2006; Kalish et al., 2011). Studies often find exemplar effects in rule based categorization such that subjects are better at applying the rule to stimuli that are similar to previously learned exemplars (Thibaut and Gelaes, 2006; Brooks and Hannah, 2006; Hahn et al., 2010), indicating that subjects may be combining rules (a form of model-based knowledge) with knowledge based on previous reinforcement (model-free knowledge based on experience with individual exemplars).

Although midbrain dopaminergic regions are sensitive to prediction error, they are reliant on interaction with representations in other neural systems. These interactions occur across time. Early activity in regions including the basal ganglia and hippocampus is sent to the lateral habenula and from there to VTA/SNc neurons, resulting in coding of the reward prediction error measure in lateral habenula and VTA/SNc (Morita et al., 2012; Shabel et al., 2012; Lisman and Grace, 2005). The basal ganglia, hippocampus, and cortex (particularly frontoparietal networks) are also the targets of the VTA/SNc neurons. Many cortical and subcortical regions show sensitivity to value and / or reward, even including primary visual cortex (Shuler and Bear, 2006). However, the most important regions coding for value are the primary target regions of midbrain dopamine neurons, in particular the basal ganglia and ventral and medial prefrontal cortex; we discuss each region below.

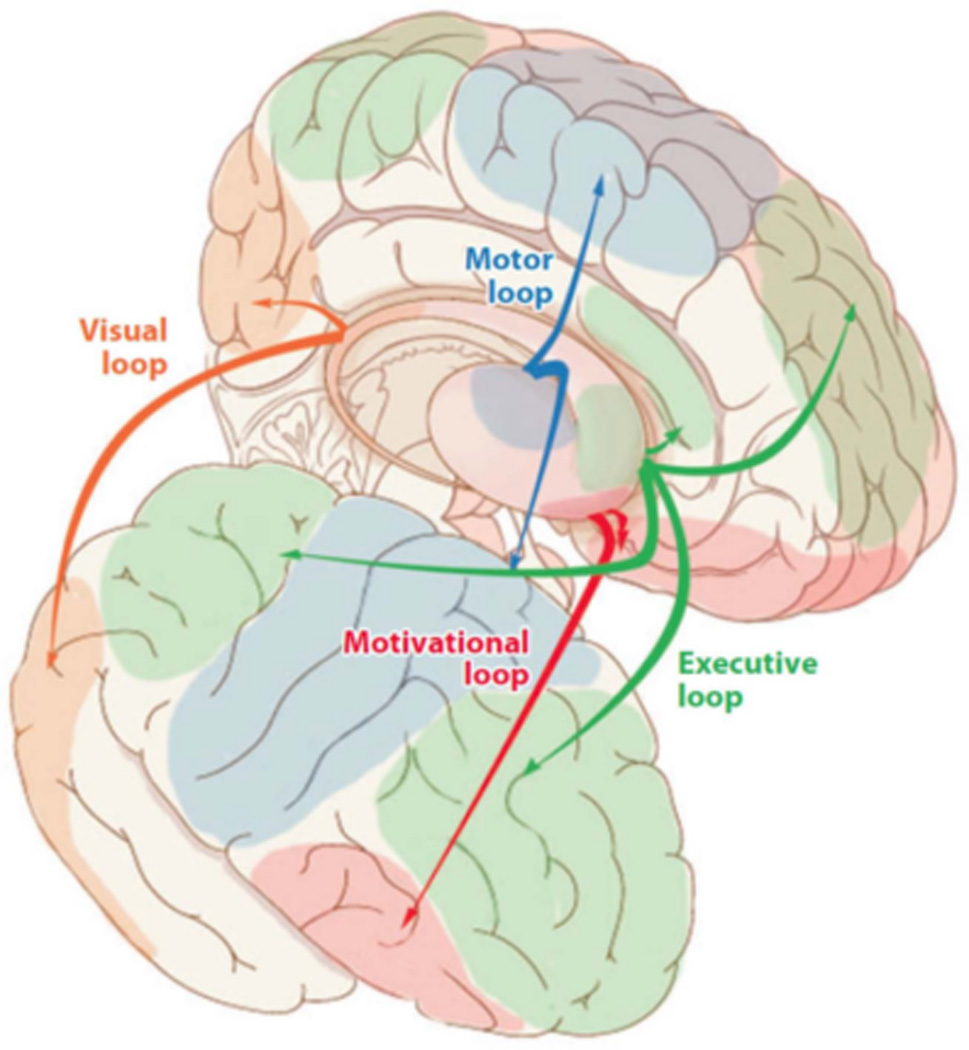

The basal ganglia form a subcortical structure that interacts with cortical regions in corticostriatal networks or “loops”, as illustrated in Figure 1. The basal ganglia receive strong dopaminergic innervation from the SNc/VTA, which directly modulates striatal activity, and is essential for synaptic strengthening in corticostriatal synapses via long term potentiation (Calabresi et al., 2007). Consistent with this reliance on dopamine projections, activity in the striatum overall is sensitive to reward prediction error (Kahnt et al., 2009; Dickerson et al., 2011). However, there are some regional differences in emphasis within the striatum. A primary distinction is between the ventral (nucleus accumbens and adjoining regions of the ventral putamen and caudate) and dorsal striatum (majority of the caudate and putamen). As shown in Figure 1, the ventral striatum interacts with orbitofrontal cortex in the motivational loop, whereas the dorsal striatum interact with other cortical regions in the motor, executive, and visual loops. Overall, ventral striatum is most sensitive to reward prediction error, whereas the dorsal regions are sensitive to the predicted value of the reward (Seger et al., 2010; Haruno and Kawato, 2006; O'Doherty et al., 2004; Lau and Glimcher, 2008; Samejima et al., 2005; Dickerson et al., 2011). Furthermore, the ventral striatum is more strongly associated with learning reward associations (as in classical conditioning) even in the absence of the requirement to act on this information. In contrast, dorsal striatum is recruited when the reward is conditional on or affects the organism’s own behavior (Tricomi et al., 2004; Bellebaum et al., 2011).

Figure 1.

Illustration of the corticostriatal loops connecting cortex with basal ganglia.

The ventral prefrontal (or orbitofrontal) cortex is thought to code for aspects of value (Padoa-Schioppa, 2011). People with damage to this region are impaired at making good decisions (Bechara et al., 1997; Gläscher et al., 2012; Camille et al., 2011; Ernst and Paulus, 2005). The somatic marker hypothesis argues that this poor decision making is due to impairment in using emotion to guide decision making. People learn from experience how different situations make them feel, including the embodied somatosensory aspects of emotion, and make future decisions based on these somatic memories, or markers (Verdejo-García and Bechara, 2009; Damasio, 1994; Bechara and Damasio, 2005). Neuroeconomic theories postulate that the ventral prefrontal cortex is important for learning and representing value, and that the emotions and motivational states associated with a stimulus or situation are an important factors determining its value. Ventral prefrontal cortex codes the value of many different things (Levy and Glimcher, 2012) including nutritive substances such as food and drink (Chib et al., 2009), money and consumer goods (FitzGerald et al., 2009) sensory qualities such as taste and odor (Rolls and Grabenhorst, 2008), and emotional qualities including pain (Roy et al., 2012). Both positive and negatively valenced values are represented, for example the value of both appetitive and aversive foods (Plassmann et al., 2010). Most studies find common coding for and integration across different types of value, including money, food, and/or consumer goods (Seymour and McClure, 2008; FitzGerald et al., 2009; Chib et al., 2009), money and pain (Park et al., 2011), and appetitive and aversive foods (Plassmann et al., 2010), however Sescousse et al. (2010) found differences in location within orbitofrontal cortex between representation of monetary and erotic reward value. Value is represented independently of motor response (Padoa-Schioppa and Assad, 2006; Hare et al., 2011). Rushworth et al. (2011) argued for separate types of value representation in lateral versus medial regions of the orbitofrontal cortex, with lateral regions more important for learning and assigning value to each option, and medial regions more important for comparison of value across options. Other models, however, locate value comparison to other regions, such as medial prefrontal cortex (Philiastides et al., 2010) or parietal cortex (Kable and Glimcher, 2009; Hare et al., 2011). Value representations exhibit range scaling that is sensitive to the range of magnitudes available in the current context; for example, $5 is coded differently if the range is between $1 to $5 versus the range is between $5 and $100 (Padoa-Schioppa, 2009; Kobayashi et al., 2010).

Other prefrontal regions are also involved in aspects of value representation. Medial prefrontal regions including the anterior cingulate cortex are important for representing the value of actions and effort (Rangel and Hare, 2010; Rudebeck et al., 2008; Croxson et al., 2009; Camille et al., 2011) and using reward and value to guide response selection (Noonan et al., 2011). Kennerley et al. (2011) argue that the ACC is important for integration of multiple decision factors. Dorsolateral prefrontal and anterior prefrontal regions are primarily associated with choice, and will be discussed in the next section.

Choice: Effects of Uncertainty

The previous section discussed reinforcement learning mechanisms for learning and representing the value of different stimuli and categories across neural regions. However, value is not mapped to a final decision in a deterministic way; the decision making literature is full of examples of situations in which subjects make decisions that are not optimal in terms of expected value (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979). The stage of decision making in which value is integrated with other factors is often called “choice” (Kable and Glimcher, 2009). In this section we will focus on one factor, uncertainty, which is particularly relevant to categorization when extending knowledge to new exemplars and situations. Uncertainty has recently attracted significant interest in neuroeconomics, with discussion of uncertainty about perception, action, value, and outcome (Bach and Dolan, 2012). In the area of categorization, we will differentiate between two potential sources of uncertainty: “reward uncertainty” concerning the outcome or reward associated with the category, and “representational uncertainty” concerning whether the item is within the limits of the category in perceptual space. Reward uncertainty is more directly associated with previous research in behavioral economics, whereas representational uncertainty has most typically been addressed in cognitive psychology. Choice is also affected by other factors, such as motivational context (Roelfsema et al., 2010; Frankó et al., 2010; Worthy et al., 2009; Maddox et al., 2006; Maddox and Markman, 2010), and emotional state (Chua et al., 2009; Quartz, 2009; Paulus and Yu, 2012).

Reward uncertainty has a long history. From simple theories of choice behavior such as expected value theory (Pascal’s 1670/1966) or expected utility theory (Bernoulli’s 1738/1954; von Neumann and Morgenstern, 1944) that provided tactical advice for maximizing winnings in games of chance, to more complex theories of rational decision making (Ellsberg, 1961), uncertainty has long been an important concern in the field of economics. Kahneman and Tversky’s influential prospect theory (1979) established the study of uncertainty and decision making within the field of cognitive psychology. Within the realm of uncertain decision making, psychologists further explored choice behavior under various types of uncertainty based on Knight’s (1921) definitions: risk, in which there is a known probability of the reward occurring, and ambiguity, in which the probabilities of rewards are not fully known. Overall humans find both types of uncertainty aversive and will often choose the certain but less valuable option (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979; Fox and Tversky, 1992); however, ambiguity is typically even more aversive than risk.

There has been a large amount of recent research computationally characterizing both risk and ambiguity and identifying brain regions sensitive to both types of reward uncertainty. Risk is often defined more formally as the variability in reward or value prediction (Kahnt et al., 2010). Risk is reflected in the firing patterns of the same dopamine neurons that are involved in reward prediction: risk is typically coded as a gradually increasing firing rate extending from the time of stimulus presentation to reward delivery (Fiorillo et al., 2003). FMRI studies find that risk modulates activity in regions of the basal ganglia and orbitofrontal cortex involved in value coding (Tobler et al., 2007; Preuschoff et al., 2006; Levy et al., 2010; Berns and Bell, 2012). Additional neural systems are also recruited when processing risk, including the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, insula and parietal lobe (Huettel et al., 2006; Huettel et al., 2005; Platt and Huettel, 2008; Kahnt et al., 2010). Ambiguity overall recruits a number of the same regions as risk; some studies (but not all: (Levy et al., 2010) find additional recruitment for ambiguity processing within the prefrontal cortex (Huettel et al., 2006; Hsu et al., 2005). Ambiguity related activity in neural regions appears to follow an inverted U function: lowest in conditions of zero ambiguity (known risk) and complete ambiguity (no knowledge of probabilities), and highest for intermediate levels of ambiguity (Bach et al., 2009; Bach et al., 2011; Lopez-Paniagua & Seger, 2012)

“Representational ambiguity” reflects the fact that there can be uncertainty about whether new exemplars are members of a category. All theories of category structure include the idea that some exemplars are better examples of the category than others, or can be identified as category members more quickly than others; this can be interpreted as reflecting more or less ambiguous evidence for category membership. For example, in prototype models, exemplars close to the prototype are better members of the category, and ambiguity about their category membership is low. Exemplars further from the prototype are more ambiguous. Furthermore, in a situation with multiple prototypes, ambiguity may result from items falling in an intermediate position between prototypes with a similar distance to both. Neuroscience research has not extensively studied representational ambiguity, but a number of studies have found basic effects consistent with ambiguity playing a role. Daniel et al. (2011) found increased corticostriatal activity related to the distance from the prototype. Grinband et al. (2006) found similar results as a function of distance from the decision bound in a rule based task. This pattern is present even in rodents; Kepecs et al. (2008) found that distance to the decision bound in a mixed odor classification task affected activity in orbitofrontal neurons. The measure of representational ambiguity will depend on the theory of how categories are represented. The general approach taken in most studies to date is to measure the distance of the stimulus in perceptual space from key representational features: for example, the distance from the prototype in prototype models, or averaged distance from previously learned exemplars in exemplar models. However, as discussed above in the section on Generalization, there are a number of theories of categorization that can be used to characterize degree of category membership. An ideal approach may be a synergistic one of using neural data to constrain categorization models and vice versa. One important caveat is that the judgment of similarity between items is not always a simple matter of relative difference in perceptual space; Medin et al. (1995) review a number of situations in which features or dimensions can come to have disproportionate weightings.

Future research should explore the degree to which reward and representational ambiguity involve similar mechanisms. One possibility is that they are completely independent: that representational ambiguity affects processes that assign stimuli to a category, whereas reward ambiguity affects only later processes that associate categories with value. Alternatively, there may be interactions; there is little relevant previous research on the topic. Another important direction is understanding how ambiguity decreases and certainty develops across the time course of learning. Learning has received little attention in decision making research on uncertainty; most studies present subjects with single decisions between options with stated risk and/or ambiguity values, rather than examining how subjects learn risk or ambiguity values from experience. However, learning is key to understanding ambiguity; typically ambiguity is high at the beginning of learning, but naturally decreases as learning progresses. Likewise, in categorization tasks subjects may be uncertain at first, but gain certainty as learning progresses. Uncertainty as measured within categorization theories (e.g., distance from the decision bound or prototype) may shift from being characterized by ambiguity (lack of knowledge of category membership) to risk (known probability of category membership).

A final way in which categorization may be affected by uncertainty is if the environment changes and reward or category membership of stimuli varies across training. Most studies of category representation have examined learning in a static environment, but Summerfield et al. (2011) found that when the environment changed rapidly, subjects used a simple working memory strategy in which they based decisions on immediately preceding stimuli rather than knowledge abstracted across trials. Reward uncertainty across time has been examined in the realm of delay discounting or intertemporal choice, which reflects the observation that humans are likely to choose immediate rewards over delayed rewards, even when the delayed reward is of greater value. In a stable environment, this leads to economically suboptimal choices (Kable and Glimcher, 2010; Kalenscher and Pennartz, 2008; Bickel et al., 2009). The tendency to choose immediate rewards has been linked to personality measures of impulsivity (Sripada et al., 2011). Choosing the higher valued delayed option is associated with prefrontal cortex activity in most studies (Luo et al., 2012), and is reduced when TMS is applied to the prefrontal cortex (Figner et al., 2010). However, it should be noted that the rationality of choosing immediate rewards is reliant on stability of the environment (McGuire and Kable, 2012), and humans incorporate knowledge of stability into their choices. The anterior PFC have been associated with making choices about future activity, possibly through monitoring the environment across time to help the organism decide whether to switch to a different strategy to maximize value (Rushworth et al., 2011), or through implementing a process of prospection (simulation of future possibilities; Luhmann et al., 2008).

Thresholding and Action

So far we have discussed a number of information processing steps recruited in simple decision making, as well as the special challenges in incorporating generalization processes as are necessary in categorization learning. In the preceding section we discussed factors including uncertainty that affect choice. The last step in this choice process is the selection of the decision, typically closely followed by the execution of the appropriate behavior associated with the decision. We will refer to this final step as decision thresholding, though different terms are used including selection, gating, and response criterion setting. Thresholding is an important part of decision making that leads to the selection of a final decision, and interacts with motor processing to allow for execution of situationally appropriate behaviors.

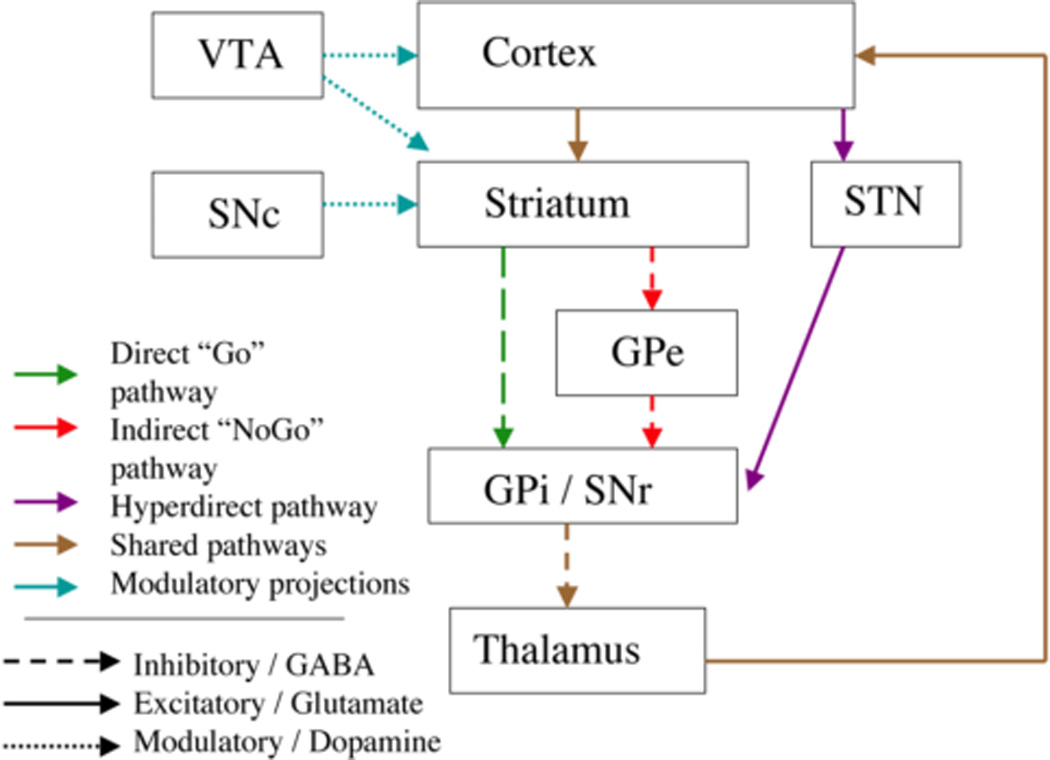

Neuroscience studies have found that the basal ganglia play a vital role in the implementation of criterion setting and thresholding. Anatomically, the basal ganglia participate in recurrent neural circuits or “loops” with cerebral cortex: cortex projects to the striatum (the input nuclei of the basal ganglia, including in primates the caudate, putamen, and nucleus accumbens), which in turn project to the basal ganglia output nuclei, from there to the thalamus, and then finally back to cortex (Seger, 2009; Lawrence et al., 1998; Seger and Miller, 2010). Different regions of cortex project to different regions of the basal ganglia, forming separate corticostriatal systems, as illustrated in Figure 1. The basal ganglia in their normal state produce as output a tonic level of inhibition to the thalamus. This inhibition results in tonic low levels of activity in the excitatory projection from the thalamus to cortex that effectively leaves the cortex inhibited, or insufficiently activated. The inhibition onto the thalamus can be selectively reduced, allowing for movement to occur, or strengthened, suppressing movement further. As illustrated in Figure 2, there are three primary pathways through the basal ganglia that modulate this inhibition, referred to as direct, indirect, and hyperdirect pathways. The direct pathway is most closely associated with response selection via the selective release of inhibition on the thalamus (Frank, 2006; Frank, 2005; Humphries et al., 2006; Stewart et al., 2012). Although the basal ganglia are most commonly thought of in terms of action selection, they play an analogous role in selection of other neural representations, for example in selection of an appropriate cognitive strategy, or selection of items to gate into working memory (O'Reilly and Frank, 2006; McNab and Klingberg, 2008).

Figure 2.

Illustration of the direct, indirect, and hyperdirect pathways through the basal ganglia.

Many studies have shown basal ganglia activity is sensitive to response thresholding (Forstmann et al., 2010; Kühn et al., 2010; Li et al., 2009; Li et al., 2007), and the speed-accuracy tradeoff (Wenzlaff et al., 2011; Bogacz et al., 2009). Thresholding activity is present in both supraliminal and subliminal conditions when subjects are unaware of the perceptual features influencing their actions (Pessiglione et al., 2008; Brooks et al., 2012). Sheth et al., (2011) found that the thresholds in the basal ganglia changed across the time course of learning; earlier in learning they were more permissive to allow for exploration of different options, whereas later they shifted to more consistently selecting the highest value option. Representation of value and other aspects of choice likely influence the basal ganglia via the anterior cingulate cortex; improved accuracy of thresholds across the time course of learning is reflected in changes in anterior cingulate activity (Domenech and Dreher, 2010; Kahnt et al., 2011).

Computational models have begun to integrate response thresholding with other aspects of decision making. Wang and colleagues (Lo and Wang, 2006; Furman and Wang, 2008) developed a model that combines layers representing perceptual activity, thresholding in the basal ganglia, and motor activity. In their model the decision threshold is sensitive to the strength of the corticostriatal synapses, and changes with experience through the influence of dopaminergic plasticity mechanisms. Thresholding is an important part of accumulator models, which typically have separate parameters for accumulation of information (drift rate) and thresholding, often referred to as response criterion setting (Smith and Ratcliff, 2004; Ratcliff, 1978). Nosofsky et al. (2012) instructed subjects to use relatively lax or strict criteria for categorizing stimuli and found correlations between criterion values and activity in both the basal ganglia and in cortical regions associated with accumulation.

There are several options as to how generalization may occur in thresholding processes. Thresholding models typically take as input activity in cortical regions projecting to the striatum; one option is that generalization is limited to the input regions, and the thresholding system is not involved. Another option is that there is convergence of information from cortex into the thresholding system, and generalization can occur via processes that combine this information. Anatomically, there are features of corticostriatal projections that indicate information combination: there is a broad numeric convergence (approximately 10:1) in the projections of cortex to striatum, and some projection neurons from cortex travel longitudinally down the striatum and can make synapses on multiple modules. However, at a cellular level individual striatal modules (groups of functionally and anatomically segregated striatal spiny cells) receive input from relatively constrained regions of cortex (Kincaid et al., 1998; Zheng and Wilson, 2002), which indicates relatively focused combination and less generalization potential (Seger, 2008).

The best developed theory of how basal ganglia thresholding and selection processes contribute to generalization with categorization learning tasks is the striatal pattern classifier underlying procedural learning in the COVIS model (Ashby et al., 2011; Ashby et al., 1998). COVIS models the known anatomical projections from visual cortex to the posterior caudate nucleus, and output projections from the posterior caudate to premotor regions; it also incorporates dopamine sensitive plasticity within the corticostriatal synapse. COVIS postulates that this basal ganglia circuit serves to map small regions of perceptual space on to motor responses indicating category membership by learning to select these motor responses when appropriate perceptual information is received. Another possible contribution of striatal thresholding processes to categorization is that they may provide a mechanism to resolve conflict between multiple sources of information. Ashby and Crossley (2010) propose that the hyperdirect path can allow the prefrontal cortex to override a response determined by the striatum, but not vice versa. Finally, many corticostriatal output projections return to the same cortical region that served as input; these return projections to visual cortex may serve to select among competing representations (Seger, 2008). This process can subserve generalization if it results in selection of the most typical of the potential representations, enhancing central tendencies and deemphasizing atypical features. The dopaminergic plasticity mechanisms within the basal ganglia provide a potential mechanism for past experience to contribute to learning these central tendencies.

One open question is whether decision thresholding is abstract, or tied to a specific motor response. As noted above, although models of selection in the basal ganglia often focus on the motor domain, the same selection processes are present at the cognitive level in selecting appropriate strategies and appropriate information for working memory. Categorization researchers have often assumed that the particular response used to indicate category membership should be irrelevant for categorization learning. However, there is increasing evidence that striatal thresholding is tightly attached to particular actions (den Ouden et al., 2010; Connolly et al., 2009). Behavioral research using categorization tasks has found that learning can be tied to specific motor effectors or response modalities (Horner and Henson, 2009; Denkinger and Koutstaal, 2009). In particular, learning in tasks with a high level of dependence on the basal ganglia is impaired when subjects transfer between effectors (Spiering and Ashby, 2008; Ashby et al., 2003). Maddox et al. (2010) argue that basal ganglia dependent categorization involves learning of both stimulus - category label and category label - response associations.

In summary, thresholding mechanisms in decision making allow for the selection of a final decision, and for execution of situationally appropriate behaviors. Empirical work in categorization typically involves thresholding in that categorical decision must lead to a discrete behavioral response (e.g., pressing a key on a response box). Generalization may be accomplished either prior to the thresholding process, or via convergence of multiple projections onto the thresholding system.

Memory and the Hippocampus in Decision Making and Generalization

Much research in decision making has given minimal consideration to the potential roles of the hippocampus. The processes discussed above, including perceptual accumulation, choice, and thresholding, do not explicitly call for involvement of the hippocampus or the declarative memory systems it supports. This may be a lasting effect of early research that found that hippocampal-based memory processes were apparently not important for categorization learning. For example, patients with amnesia have overall preserved learning on a variety of categorization tasks such as the Posner dot pattern task (Knowlton and Squire, 1993) and early learning in probabilistic classification tasks (Knowlton et al., 1994). The results of early neuroimaging research implied that the hippocampus was actively suppressed during learning (Poldrack et al., 1999; Seger and Cincotta, 2005; Poldrack et al., 2001). However, more recent neuropsychological research has found some circumstances in which patients with amnesia have impaired category learning (Hopkins et al., 2004; Graham et al., 2006), indicating that there are situations in which the hippocampus does make important contributions. Recent neuroimaging research finds more complicated interactions between striatal and hippocampal systems (Foerde et al., 2006; Seger et al., 2011; Dickerson et al., 2011), indicating that each may contribute when task demands are appropriate. In this section we will describe new ways of conceptualizing the role of the hippocampus in decision making and categorization. First, we will describe the computational role of the hippocampus for associative or relational processing and how it may be recruited for generalization in decision making and categorization. Second, we will discuss how the hippocampus may contribute to and interact closely with mechanisms discussed above as being important for decision making and categorization.

Computational models postulate that the hippocampus subserves relational processing via two important functions implemented in hippocampal circuitry: pattern separation, in which cortex projects to a large number of cells in the dentate gyrus, forming distinct individual representations of currently experienced episodes, and pattern completion in which autoassociative mechanisms in the CA3 region form relations between input elements, binding them together into a relational memory (Norman and O'Reilly, 2003; Becker et al., 2009). These functions are vital for forming discrete representations of individual items and events that we experience in order to minimize confusion between similar items and events. FMRI in humans supports these roles of the hippocampus in learning new items and relationships. First, the hippocampus is recruited for encoding novel stimuli (Bunzeck et al., 2012; Poppenk et al., 2010; Preston et al., 2010) and identifying contextual novelty (Kumaran and Maguire, 2009). Second, the hippocampus is active when subjects learn relationships between items (Giovanello et al., 2009; McCormick et al., 2010; Shohamy and Wagner, 2008).

Within the realm of categorization, the role of the hippocampus in novelty processing implies that it may be critical in forming initial stimulus representations (Little et al., 2006; Seger et al., 2011), and raises the possibility that categorization learning impairments in people with hippocampal amnesia may be due to interference with stimulus encoding rather than categorization learning per se (Meeter et al., 2008; Shohamy et al., 2009). Alternatively, subjects may make some category membership decisions on the basis of retrieving an individual memory of a similar preceding event, and then using analogical reasoning processes to decide whether the new stimulus is sufficiently similar to the retrieved one (Seger and Miller, 2010). The hippocampus may be particularly useful in encoding stimuli that are exceptions to the overall structure of the category due to the demands for individual representations of exception stimuli. Davis and colleagues (Davis et al., 2012a; 2012b) found evidence that hippocampal recruitment is greater for exception than rule following items and was accurately predicted by computational measures of recognition strength and error correction. Furthermore, the degree of hippocampal contributions to categorization may depend on the particular strategy used to learn the category; Zeithamova et al. (2008) found greater hippocampal activity when subjects learned to categorize stimuli into one of two categories than when they learned to categorize the same stimuli as members or nonmembers of a single category.

Recent studies have identified types of generalization that may be supported by the hippocampus. There is an inherent contradiction in considering the role of generalization in the hippocampus: as argued above, the role of relational processing in the hippocampus for memory is to encode individual items and events to minimize confusion with similar items and events. The complementary memory systems framework (O'Reilly and Norman, 2002) formalizes this contradiction: it argues that we have multiple systems for learning because achieving accurate individual item representations is computationally incompatible with generalizing across items. However, research indicates that the hippocampus can contribute to encoding overlapping patterns of associations in such a way that the resulting representation includes novel consistent pairings, and contributes to transferring previously learned associations to novel stimuli (Shohamy and Wagner, 2008; Kumaran et al., 2009; Reber et al., 2012; Zeithamova and Preston, 2010). Kumaran and McClelland (2012) present a model of how these recurrent interactions within the hippocampus may lead to generalization. For example, Shohamy and Wagner (2008) used a task in which subjects were trained on several overlapping relations (e.g., A -> X, A -> Y, B -> X), and found both that subjects could extend this pattern of relations to the novel relation B -> Y and that hippocampal activity during encoding was associated with this extension. Wimmer and Shohamy (2012) further showed the hippocampus plays a role in extending expectation of reward to unrewarded stimuli associated with rewarded stimuli. These results imply that the hippocampus may be more involved in categorization tasks in which there are tightly overlapping associations that may be amenable to hippocampal encoding mechanisms, and which may be mediated by reward.

There is increasing focus across the field of neuroscience on how the hippocampus can interact with other neural systems in a cooperative and complementary fashion (Johnson et al., 2007; Doeller et al., 2008). The hippocampus may have a significant role to play in several of the decision making processes we have discussed in this paper. At the level of learning of value, recent decision making research emphasizes the role of dopamine and reward learning systems in modulating hippocampal activity (Shohamy and Adcock, 2010) and contributing to memory formation that is sensitive to value and reward. As such, the implications of reward related value learning processes discussed in a previous section are relevant for hippocampal systems as well as the basal ganglia and orbitofrontal cortex regions discussed previously. However, it is likely that each system will utilize reward information for different computational purposes. For example, basal ganglia mediated learning requires reward to be presented within a brief time after the decision, whereas the hippocampus is more sensitive to delayed rewards (Foerde and Shohamy, 2011). At the level of choice, there are a number of examples in which hippocampal and frontoparietal systems interact. Relational representations subserved by the hippocampus interact with relational processing in the anterior prefrontal cortex (Wendelken and Bunge, 2010). Relational representations supported by the hippocampus have been shown to be important in working memory (Hannula et al., 2006) and imagination of future events (Martin et al., 2011). There is less relevant research about the interactions between hippocampus and other systems in decision making. Future research may address the relation between hippocampal systems and perceptual accumulation systems: is the hippocampus an output target of these systems, or does it provide input to accumulator systems, or both, depending on the situation? Another open question is whether or how hippocampal mechanisms interact with other decision making mechanisms at the final level of decision thresholding.

Future Challenges: Conceptual Knowledge and Categorization Goals

In this paper, we focused on relatively simple forms of decision making and categorization. In the future, researchers will need to extend beyond these fundamental processes and address additional questions. One important limitation is that many simple categorization tasks focus on learning novel categories that have minimal overlap with previously learned categories. However, in the real world perceptual categories are embedded in complex conceptual knowledge representations (Rehder and Kim, 2006; Lambon Ralph et al., 2010) that combine information across modalities and functions, and in humans interface with language and lexical representations (Rogers and McClelland, 2011, Strnad et al., 2011). Thus, categorization mechanisms must be able to interact with these representations in order to subserve learning. For example, when we learn about a new kind of animal, we incorporate this knowledge into our preexisting knowledge about animals. Preexisting knowledge has been shown to affect what can be learned about new items; a good example is the phenomenon of blocking, in which previous knowledge limits the types of relationships that are learned (Soto and Wasserman, 2010; Bott et al., 2007; Folstein et al., 2010). One particularly important domain is social categorization, and how the interactions between preexisting knowledge and category learning may contribute to potentially misleading stereotypes based on racial or other groupings (Ito and Bartholow, 2009; Beer et al., 2008; Oosterhof and Todorov, 2008)

A further limitation is that simple categorization tasks have as their goal examining how stimuli are assigned to category membership. However, the functions of categorization go well beyond mere grouping. One important reason to learn categories is that they provide a basis for inference: knowing that an item belongs to a category allows the organism to infer many additional characteristics about the item (Yamauchi et al., 2002). Another is that categories have goals, and some category members are better for achieving that goal than others; for example, in the category of edible fish, one goal might be having a desirable taste, and a salmon might fulfill this goal better than a guppy (Kim and Murphy, 2011). Some factors that affect categorization for the purpose of grouping may not affect categorization for other purposes such as inference in the same way (Hoffman and Murphy, 2006); for example, Murphy and Ross found that representational ambiguity (discussed above) did not affect performance on an inference task (Murphy and Ross, 2005).

A final important direction for future research will be incorporating knowledge of emotion into categorization and how emotion affects category decision making. Research on decision making has addressed emotion in a number of ways. The somatic marker hypothesis argues that emotion and its associated physiological states or feelings are crucial to making good real life decisions (Bechara and Damasio, 2005). Neuroeconomic theories account for emotion as one of several types of value (Roy et al., 2012; Rolls and Grabenhorst, 2008). Emotions and mood states interact with more cognitive processes by biasing decision making strategies; for example, the emotion of regret can contribute to loss aversion (Chua et al., 2009). Finally, the amygdala, a neural system involved in a variety of emotional processes, interacts with the cortical, hippocampal, and striatal systems that have been emphasized in this review (Pennartz et al., 2011; Popescu et al., 2009); future research would benefit from examining these interactions and their role in decision making and categorization.

Conclusion

In this review we have argued that categorization is a form of decision making which incorporates generalization mechanisms, and discussed how recent computational and experimental methods developed to study decision making may be extended to allow for generalization. Accomplishing this will likely keep decision and categorization researchers busy for some time to come. We hope that research integrating decision making and categorization will ultimately allow us to more deeply understand generalization and categorization within the human conceptual system.

Research Highlights.

Identifies commonalities between decision making and categorization

Argues that decision making must incorporate mechanisms that allow for generalization

Examines how accumulator, reinforcement learning, and theshold models may generalize

Considers the role of the hippocampus in generalization and decision making

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01- MH079182) to C.A.S. We would like to thank Dan Lopez-Paniagua, Kurt Braunlich, Hillary Wehe, and Howard A. Landman for useful comments on previous drafts of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The question of plasticity during development is an important one; there is wide evidence that during development the perceptual system learns to represent the types of perceptual information present in the environment. This leads to specialized representations, particularly in the higher order visual regions in which there are groups of cells that specialize in processing faces, objects, words, and other important types of visual stimuli (Op de Beeck et al., 2008) (Tsao et al., 2008).

References

- Anderson JR. The adaptive nature of human categorization. Psychol Rev. 1991;98:409–429. [Google Scholar]

- Aron AR, Shohamy D, Clark J, Myers C, Gluck MA, Poldrack RA. Human midbrain sensitivity to cognitive feedback and uncertainty during classification learning. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:1144–1152. doi: 10.1152/jn.01209.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby FG, Alfonso-Reese LA. Categorization as probability density estimation. J Math Psychol. 1995;39:216–233. [Google Scholar]

- Ashby FG, Alfonso-Reese LA, Turken AU, Waldron EM. A neuropsychological theory of multiple systems in category learning. Psychol Rev. 1998;105:442–481. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.105.3.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby FG, Crossley MJ. Interactions between declarative and procedural-learning categorization systems. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2010;94:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby FG, Ell SW, Waldron EM. Procedural learning in perceptual categorization. Mem Cognit. 2003;31:1114–1125. doi: 10.3758/bf03196132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby FG, Maddox WT. Human category learning. Annu Rev Psychol. 2005;56:149–178. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby FG, Paul EJ, Maddox WT. COVIS. In: Pothos EM, Wills AJ, editors. Formal Approaches in Categorization. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ashby FG, Townsend JT. Varieties of perceptual independence. Psychol Rev. 1986;93:154–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audley RJ, Pike AR. Some stochastic models of choice. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology. 1965;18:207–225. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8317.1966.tb00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach DR, Dolan RJ. Knowing how much you don't know: a neural organization of uncertainty estimates. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:572–586. doi: 10.1038/nrn3289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach DR, Hulme O, Penny WD, Dolan RJ. The known unknowns: neural representation of second-order uncertainty, and ambiguity. J Neurosci. 2011;31:4811–4820. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1452-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach DR, Seymour B, Dolan RJ. Neural activity associated with the passive prediction of ambiguity and risk for aversive events. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1648–1656. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4578-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banich MT, Mackiewicz KL, Depue BE, Whitmer AJ, Miller GA, Heller W. Cognitive control mechanisms, emotion and memory: A neural perspective with implications for psychopathology. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33:613–630. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Damasio AR. The somatic marker hypothesis: A neural theory of economic decision. Games and economic behavior. 2005;52:336–372. [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Damasio H, Tranel D, Damasio AR. Deciding advantageously before knowing the advantageous strategy. Science. 1997;275:1293–1295. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5304.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker S, Macqueen G, Wojtowicz JM. Computational modeling and empirical studies of hippocampal neurogenesis-dependent memory: Effects of interference, stress and depression. Brain Res. 2009;1299:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.07.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer JS, Stallen M, Lombardo MV, Gonsalkorale K, Cunningham WA, Sherman JW. The Quadruple Process model approach to examining the neural underpinnings of prejudice. Neuroimage. 2008;43:775–783. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellebaum C, Jokisch D, Gizewski ER, Forsting M, Daum I. The neural coding of expected and unexpected monetary performance outcomes: Dissociations between active and observational learning. Behav Brain Res. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernoulli D. Exposition of a new theory on the measurement of risk. Econometrica. 1954;22:23–36. Original work published 1738. [Google Scholar]

- Berns GS, Bell E. Striatal topography of probability and magnitude information for decisions under uncertainty. Neuroimage. 2012;59:3166–3172. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC. The debate over dopamine's role in reward: the case for incentive salience. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;191:391–431. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0578-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Pitcock JA, Yi R, Angtuaco EJ. Congruence of BOLD response across intertemporal choice conditions: fictive and real money gains and losses. J Neurosci. 2009;29:8839–8846. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5319-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatter K, Schultz W. Rewarding properties of visual stimuli. Exp Brain Res. 2006;168:541–546. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0114-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bledowski C, Kaiser J, Rahm B. Basic operations in working memory: Contributions from functional imaging studies. Behav Brain Res. 2010;214:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogacz R, Wagenmakers EJ, Forstmann BU, Nieuwenhuis S. The neural basis of the speed-accuracy tradeoff. Trends Neurosci. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bott L, Hoffman AB, Murphy GL. Blocking in category learning. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2007;136:685–699. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.136.4.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]