Abstract

Predicting physical and functional links between cellular components is a fundamental challenge of biology and network science. Yet, correlations, a ubiquitous input for biological link prediction, are affected by both direct and indirect effects, confounding our ability to identify true pairwise interactions. Here we exploit the fundamental properties of dynamical correlations in networks to develop a method to silence indirect effects. The method receives as input the observed correlations between node pairs and uses a matrix transformation to turn the correlation matrix into a highly discriminative silenced matrix, which enhances only the terms associated with direct causal links. Achieving perfect accuracy in model systems, we test the method against empirical data collected for the Escherichia coli regulatory interaction network, showing that it improves on the best preforming link prediction methods. Overall the silencing methodology helps translate the abundant correlation data into valuable local information, with applications ranging from link prediction to inferring the dynamical mechanisms governing biological networks.

The currently incomplete maps of molecular interactions between cellular components limit our understanding of the molecular mechanisms behind human disease1-6. Ultimately, high-throughput mapping projects7-10 are expected to provide the accurate maps of interactomes necessary to systematically unlock disease mechanisms. Yet, as a complete interaction map is at least a decade away, we need to develop tools that allow us to infer the structure of cellular networks from empirically obtained biological data11,12. Many current tools designed to infer functional and physical interactions in the cell rely on the global response matrix,

| (1) |

which captures the change in node i's activity in response to changes in node j's13. This matrix can be measured directly from gene knockout or overexpression experiments, or inferred indirectly using related measures such as Pearson or Spearman correlations14, mutual information15,16 or Granger causality17. Traditional methods for predicting links15,16,18,19 assume that the magnitude of Gij correlates with the likelihood of a direct functional or physical link between nodes i and j. Yet Gij cannot distinguish between direct and indirect relationships: a path i → k → j can result in a significant response measured between i and j, falsely suggesting the existence of a direct link between them (Fig. 1a-b).

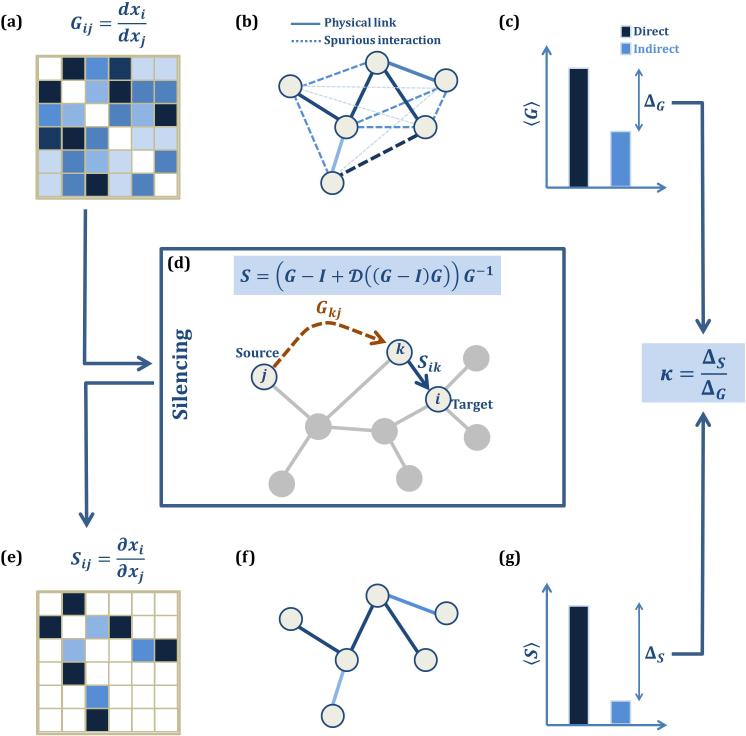

Figure 1. Silencing indirect links.

(a) The experimentally observed global response matrix, Gij, accounts for direct as well as indirect correlations, with no clear separation between them. The source of Gij could be gene coexpression data, statistical correlations or genetic perturbation experiments. (b) In the absence of a clear separation in Gij assigned to direct and indirect correlations, our ability to infer direct physical links (solid lines) is limited. Simple thresholding, i.e. accepting all links for which Gij exceeds a predefined threshold, is known to predict spurious links (strong dashed lines) and overlook true links (light solid lines). (c) While the average Gij terms associated with direct links (dark blue) are higher than the average terms associated with indirect links (light blue), as captured by the discrimination ratio, ΔG, the difference is not sufficient to identify direct and indirect links. (d) Silencing is achieved through Eq. (5), which exploits the flow of information in the network: the flow from the source (j) to the target (i) is carried through the indirect effect Gkj (orange) coupled with the direct impact Sik of the target's nearest neighbor κ (blue). By silencing the indirect contributions, Eq. (5) provides the local response matrix, Sij , whose non-zero elements correspond to direct links. (e) – (f) In Sij the terms associated with indirect links are silenced, allowing us the detect only the direct links of the underlying network. (g) As indirect terms become much smaller in Sij, we obtain a greater discrimination ratio, ΔS. The degree of silencing, κ, captures the increase observed in the discrimination ratio by the transition from Gij to Sij (5).

Several methods correcting for such effects have been proposed: information theoretic approaches evaluate the association between nodes by measuring the entropy of their mutual activities, where a low entropy indicates a statistical dependence between the node activities16,18,20; probabilistic models, such as the graphical Gaussian model, allow one to evaluate the correlation between i and j, while controlling for the state of node k, and thereby provide a more indicative measure of direct linkage21-25; other models rely on assumptions pertaining to the network topology, such as the tendency of real networks to exhibit strong degree correlations26. The ultimate solution, however, should enable us to fully unwind the direct from the indirect effects, providing a measure which distinctly indicates the existence of direct links. Consequently, here we focus on the local response matrix

| (2) |

in which the contribution of indirect effects is eliminated. In contrast with (1), which allows for global changes in i and j's environment, here the “∂” indicates that Sij is defined to capture only local effects, namely the response of i to changes in j when all surrounding nodes except i and j remain unchanged. Hence Sij > 0 implies a direct link between i and j.

Here we derive a method for calculating the local response matrix (2) from experimentally accessible correlation measures, allowing us to mathematically discriminate direct from indirect links. We show that the resulting Sij matrix, in which the contribution of indirect paths is silenced, is more discriminative than the empirically obtained Gij matrix, enhancing our ability to extract direct links from experimentally collected correlation data.

Results

The silencing method

To extract Sij from the experimentally accessible Gij, we formally link (1) and (2) via

| (3) |

Equation (3) is exact and the sum accounts for all network paths connecting i and j (Supplementary Note S.I.1 - 2). It is of limited use, however, as it requires us to solve N2 coupled algebraic equations. In Supplementary Note S.I.1 we show that (3) can be reformulated as

| (4) |

where I is the identity matrix and sets the off-diagonal terms of M to zero. To obtain an approximate solution for S we use that fact that typically, perturbations decay rapidly as they propagate through the network, so that the response observed between two nodes is dominated by the shortest path between them. This allows us to approximate with (Supplementary Note S.I.3), obtaining

| (5) |

Equation (5), our main result, provides Sij from the experimentally accessible Gij. It achieves this through a 'silencing effect’, in which direct response terms are preserved, while indirect responses are silenced. To understand this consider a specific term in Gij, documenting the response of node i to j's perturbation. As indicated by Eq. (3), this response is a consequence of all direct and indirect paths leading from j to i. As we document below, the transformation (5) detects the indirect paths and silences them, maintaining only the contribution of the direct paths (Fig. 1d-f).

Silencing in model systems

To demonstrate the predictive power of (5), we implemented Michaelis-Menten dynamics on a model network (Supplementary Note S.III), as commonly used to model generegulation27,28. We obtained Gij by perturbing the activity of each node and then calculated Sij using (5). Figure 2a shows the Gij and Sij terms associated with interacting (green) and non-interacting (orange) node pairs. Although Gij is higher for direct interactions, the overlap between the orange and the green symbols indicates a lack of a clear threshold q that separates direct and indirect interactions. In contrast, Sij displays a clear separation between direct and indirect interactions, accurately predicting each direct link. Indeed, the ROC curve derived from Gij (Fig. 2b, red) has an area of AUROC = 0.91, reflecting inherent limitations in separating direct from indirect interactions based on Gij only. In contrast for Sij we obtain AUROC = 0.997 (blue), where the true positive rate (TPR) reaches 100% with a false positive rate (FPR) of less than 10–3. Also, although for Gij precision increases gradually with the threshold q (Fig. 2c), for Sij precision jumps to one for q > 10–4. Hence, in our well controlled model system effectively any non-zero Sij corresponds to a direct link.

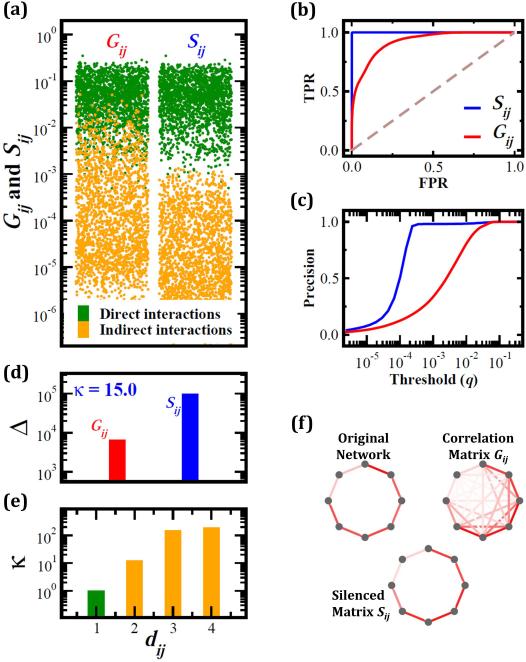

Figure 2. Network inference in model systems.

We numerically simulated Michaelis-Menten dynamics on a scale-free network [40-42], extracting the correlations Gij between all pairs of nodes (see Sec. S.III for details). (a) Gij and Sij associated with interacting (green) and non-interacting (orange) node pairs. Sij silences the correlations associated with indirect interactions, resulting in a clear separation between direct and indirect interactions, a phenomenon absent from Gij. (b) ROC curve obtained from Gij (red, area 0.91) and Sij (blue, area 0.997). The Sij network reaches 100% accuracy with a negligible amount of false positives. (c) Precision obtained for threshold q for Gij (red) and Sij (blue). The gradual rise of the Gij-based precision indicates that for a broad range of thresholds only a small fraction of the links will be identified. In contrast, the steep rise in precision for Sij indicates its enhanced discriminative power between direct and indirect links: virtually any non-zero Sij corresponds to a directly interacting pair. (d) The discrimination ratio, Δ, is much higher in Sij (blue) compared to Gij (red). This indicates that Sij is a much better predictor of direct vs. indirect interactions. The silencing (5), which captures the increase in the discrimination ratio is κ = 15.0. (e) Silencing increases with the path length dij between i and j, so that the more indirect is the link the more dramatic is the silencing. (f) The source of Sij's success is the silencing effect, here illustrated on correlations measured for a linear cascade. The reconstruction of the cascade from Gij is confounded by numerous non-vanishing indirect correlations. In Sij the indirect correlations are silenced, providing a perfect reconstruction.

The performance of (5) is due to the silencing effect: it leaves Gij unchanged if i and j are linked, while it systematically lowers all Gij not rooted in a direct interaction. To quantify this effect we measured the discrimination ratio ΔG = 〈Gij〉Dir/〈Gij〉Indir (ΔS = 〈Sij〉Dir/〈Sij〉Indir) which captures the ratio between Gij (Sij) terms associated with direct links and those associated with indirect links (Fig. 1c and g). We find that Sij is much more discriminative than Gij owing to its silencing of indirect responses. To quantify this effect we measure the silencing

| (6) |

which captures the increased power of Sij to discriminate between direct and indirect links compared to Gij. In our model system we find that κ = 15, a silencing of more than an order of magnitude (Fig. 2d). Furthermore, the longer is the distance dij between two nodes, the larger is the silencing (Fig. 2e). As an illustration, consider a linear cascade in which changes in any node result in a finite response Gij by all other nodes (Fig. 2f). Equation (5) silences all indirect responses, while leaving the response of direct links effectively unchanged, offering a discriminative measure that enables a perfect reconstruction of the original network.

Predicting molecular interactions in E. coli

To test the predictive power of (5) on real data we used the E. coli datasets distributed by the DREAM5 network inference challenge19. The input data include a compendium of microarray experiments measuring the expression levels of 4,511 E. coli genes (141 of which are known transcription factors) under 805 different experimental conditions (Supplementary Note S.IV.1). We constructed three separate global response matrices Gij between the 141 transcription factors and their 4,511 potential target genes, based on (i) Pearson correlations; (ii) Spearman rank correlations; and (iii) mutual information, which are three commonly used methods for link detection (Supplementary Note S.IV.3). From each of the three Gij matrices we obtained Sij via (5), and compared the performance of Gij with the pertinent Sij. To validate our predictions we relied on the gold standard used in the DREAM5 challenge, consisting of 2,066 established gene regulatory interactions. Measuring AUROC from Gij and Sij, we find an improvement of 56% for Pearson correlations (Fig. 3a), 67% for Spearman rank correlations (Fig. 3b) and a smaller improvement of 6% for mutual information (Fig. 3c), e.g. allowing us to improve upon the top performing inference methods19.

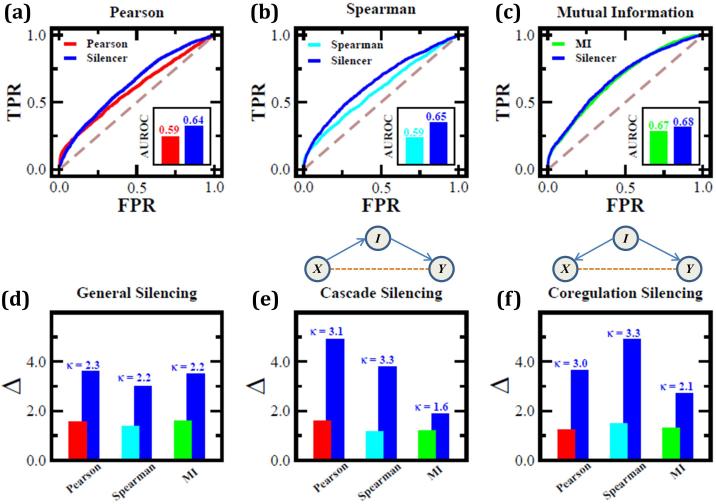

Figure 3. Inferring regulatory interactions in E. coli.

(a) Starting from gene expression data, we used Pearson correlations in expression patterns to construct Gij for 4,511 E. coli genes, obtaining Sij via (4). We compared our predictions to a gold standard of experimentally verified genetic regulatory links [19]. The area under the ROC curve (AUROC) is increased from 0.59 to 0.64 in the transition from Gij to Sij, representing a 56% improvement (above the baseline of 0.5 for a random guess). (b) An improvement of 67% is observed for Spearman rank correlations. (c) A less dramatic improvement of 6% is shown when Gij is constructed using mutual information. (d) The discrimination ratio for all three methods compared with that obtained from the pertinent Sij matrix. The transition to Sij (4) increases the discrimination between direct and indirect interactions by a factor of two or more, so that indirect interactions have a significantly lower expression in Sij. (e) - (f) This observation becomes even more dramatic when focusing on two specific motifs: cascades and co-regulators. In Gij the indirect correlation between X and Y, which is induced by the intermediate node, I, may lead to the false prediction of the spurious X – Y link. Thanks to silencing, the discrimination between the direct and indirect links in these motifs is increased by a factor of three or more for Pearson and Spearman correlations, and by a factor of about two for mutual information.

We further tested the discrimination ratio, Δ, and the silencing, κ, for each of these methods, finding that indirect correlations are subject to an average of two-fold silencing in the transition from Gij to Sij (Fig. 3d). Silencing is especially crucial in the presence of the cascade and co-regulation motifs shown in Figures 3e-f, where most inference methods indicate a spurious link between X and Y owing to the indirect correlation mediated by node I. Indeed, the transformation (5) silences these indirect correlations by a factor of three or more for Pearson and Spearman correlations and by a smaller factor for mutual information, overcoming one of the most common hurdles of inference methods, which tend to over-represent triadic motifs19.

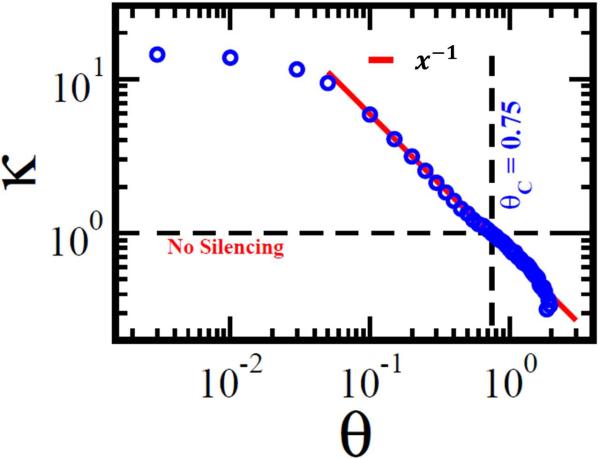

The effects of noise and uncertainty

As all experimental data is subject to noise, the global response matrix, Gij, is characterized by some degree of uncertainty. To test the performance of our methodology in the presence of noise, we repeated the numerical experiment of Figure 2, this time adding Gaussian noise to Gij, which allows us to calculate silencing as a function of increasing the signal to noise ratio θ (Fig. 4). As expected, silencing is unaffected by small values of θ, so that κ features a plateau below θ ≲ 0.1. For large θ, silencing decays as κ ~ θ–1, demonstrating that the performance of the method decreases slowly with increasing the signal to noise ratio. Indeed, as opposed to a rapid exponential decay, the observed slower power-law dependence indicates that the method is rather tolerant against noise. Silencing is lost only when the noise reaches the critical level θC ≈ 0.75, when the signal is almost completely overridden by noise, leading to κ = 1 (Supplementary Note S.V.1).

Figure 4. Silencing in a noisy environment.

To test the method's performance in the presence of a noisy input we added Gaussian noise to the numerically obtained Gij, and measured the silencing, κ, vs. the signal to noise ratio θ. For low noise levels (θ ≲ 0.1) silencing is relatively unharmed. At higher noise level silencing decreases as κ ~ θ–1, a slow decay that supports the robustness of the method. Silencing is lost at θC ≈ 0.75, when the signal is almost fully driven by the noise.

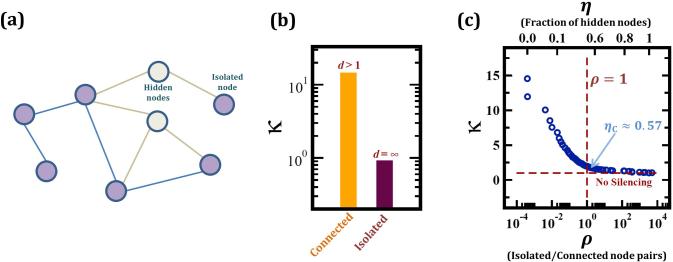

Hidden nodes offer another source of uncertainty. They represent the fact that in most cases we are unable to read the states of all nodes in the system29. To illustrate the effect of the hidden nodes on the performance of the silencing method, we consider the case of a simple cascade i → k → j, where the intermediate node k is hidden. In this scenario, Eq. (5) will not be able to silence the indirect i → j link because in the observable system the Gij term cannot be attributed to any indirect path. Hence, absent any other information about the system, it is mathematically impossible to infer the indirectness of Gij, as the removal of k isolated i from j30. This touches upon the fundamental mechanism of silencing: as illustrated in Figure 1 (and Supplementary Note S.I.2) the silencing transformation (5) exploits the flow of information through indirect paths. Consequently, if as a result of hidden nodes the network fragments into several components such that the node pair i and j become isolated from each other, then all indirect paths between them became hidden and the pertinent Gij term will not be silenced (Fig. 5a–b). Hence silencing is expected to fail only when the network breaks into many isolated components so that most node pairs become isolated. Fortunately, a fundamental property of complex networks is that with average degree 〈k〉 >> 1, one needs to remove a large fraction of the nodes to fragment the underlying giant connected component31-34. Therefore we can build on percolation theory, which allows us to analytically predict how the size of the largest connected component changes with the random removal of a certain fraction of nodes35,36. The calculation shows that silencing is maintained as long as the fraction of hidden nodes is smaller than

| (7) |

where (Supplementary Note S.V.2). This equation indicates that for large 〈k〉 the method will be reliable even if a large fraction of the nodes are hidden.

Figure 5. Performance with hidden nodes.

(a) A network with N = 8 nodes of which a fraction η = 1/4 are hidden. The observable sub-network has six nodes, five forming a connected component (with 10 connected node pairs) and one isolated (6 isolated pairs). The ratio between isolated and connected node pairs here is ρ = 6/10. Equation (5), applied to the observable network, successfully silences the indirect Gij terms among the nodes of the connected component. However the correlations between the isolated node and the rest of the network, lacking an indirect path, are not silenced. (b) To test the silencing in the presence of hidden nodes we used the numerically obtained Gij (Fig. 2) from which we eliminated a fraction η of the nodes, obtaining an observable network with 104 isolated node pairs (ρ ≈ 103). After applying Eq. (5) to the remaining nodes we find that the silencing of Gij terms associated with connected node pairs is unaffected (orange bar), while for the isolated node pairs silencing drops to κ = 1, namely no silencing (purple bar). Hence for the isolated node pairs Sij is not more predictive than Gij. (c) Increasing the fraction of hidden nodes, η (top horizontal axis), we measured κ vs. ρ. As expected, silencing is observed as long as most node pairs are connected via finite paths (ρ < 1). However, when the number of hidden nodes is increased to the point that the isolated pairs dominate (ρ > 1), silencing is no longer observed (κ = 1). The critical fraction of hidden nodes, ηC, corresponds to ρ = 1, the point where silencing no longer plays a significant role. Here we find ηC ≈ 0.57 (blue arrow), in agreement with the prediction of Eq. (7).

To test this prediction, we revisited the numerically obtained Gij analyzed in Figure 2 and measured the degree of silencing after randomly removing an increasing fraction of nodes. In each case we also measured the ratio between isolated and connected node pairs (ρ). We find that, as predicted, the degree of silencing is driven mainly by ρ, approaching κ ≈ 1 (no silencing) when ρ ≥ 1, namely when the isolated pairs begin to dominate the network (Fig. 5c). Here as 〈k〉 = 4, Eq. (7) predicts ηC ≈ 0.57, i.e. the method will fail only when almost 60% of the nodes are hidden. Note that for biological networks 〈k〉 is expected to be in the range of37 〈k〉 ≲ 10, predicting ηC ≲ 0.8. Namely, one needs to lose access to 80% of the nodes for silencing to lose its effectiveness.

Discussion

With computational complexity , Eq. (5) is scalable and requires no assumptions about the network topology. By silencing indirect effects, it turns the raw correlation data into a predictive Sij matrix, dominated by direct interactions. It is especially suited to treat perturbation data, such as genetic perturbation experiments, in which case Gij describes the response of all genes (dxi) as a consequence of the perturbation of the source gene (dxj)38. In practice, however, Gij could be the result of a broader set of experimental realizations where other measures are used to evaluate the association between nodes, typically statistical measures such as Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients. Still, our empirical results (Fig. 3) clearly show that the transformation (5) successfully applies to these empirically accessible measures as well. Hence silencing is largely insensitive to the specific process by which Gij was constructed.

The method's broad applicability is rooted in the fact that it does not depend on the value of each specific term in Gij, but rather on the global relationships between them. Indeed, the global structure of Gij reflects the patterns of propagation of the perturbations along the network. Equation (5) helps uncover these paths from the raw data, disentangling the direct from the indirect effects. These patterns of information flow are inherent to the underlying network structure, and should not depend on the specific experimental realization of (1). For instance, a cascade i → j → k will be characterized by a decreasing correlation propagating along the arrows, a large correlation between i and j and a weaker one between i and k. Although the magnitude of these correlations might depend on the size or the form of i's perturbation as well as on the statistical measure we used to evaluate them, the decay pattern required to infer the structure of the cascade is an inherent property of the network flow and can be successfully detected by the silencing method (Supplementary Note S.I.4).

The silencing transformation is derived from fundamental mathematical principles of dynamical correlations in networks. Hence it is expected to apply under rather general conditions. However, as Equation (5) indicates it requires that the input matrix, Gij, is invertible. This imposes some limitations when constructed from statistical correlation measures. For instance in the empirical results of Figure 3a we constructed Gij from Pearson correlations, using the states of 4,511 nodes measured under 805 experimental conditions. In general, if the number of experimental conditions is smaller than the number of nodes the resulting Pearson correlation matrix may be singular. In this case additional processing will be required before (5) could be applied. Here, following the DREAM5 protocol, we only focused on the correlations between the 141 known transcription factors and the rest of the nodes, which lead to an invertible Gij (Supplementary Note S.IV). Other means to ensure Gij's invertibility are discussed in Supplementary Note S.IV.4.

Isolating indirect effects in correlation data, a fundamental challenge of network inference, is typically approached through local probabilistic tools12,14-18. In contrast, the success of the silencing method is rooted in its exploitation the global network topology39: it relies on the fundamental principles of network structure and dynamics to identify and silence the effects of indirect paths. The ability to extract Sij from Gij could also have implications for our understanding of network dynamics. Indeed, Gij is a global network measure, as its magnitude is determined by the numerous indirect paths connecting i and j. Hence, for a given dynamics, the Gij matrix will take a different form depending on the network topology, making it a poor predictor of the system's dynamics. By eliminating indirect effects, Sij measures the effect gene i would have on gene j had they been isolated from the rest of the network. It thus helps us quantify the dynamical mechanism that governs individual pairwise interactions, avoiding the convolution of dynamical and topological effects present in experimental data. For instance, consider a set of perturbation experiments providing Gij. The structure of Gij reflects the microscopic mechanisms that govern the pairwise interactions, e.g. genetic regulation and biochemical processes. It is difficult, however to extract this information from Gij since its terms are a convolution of many interactions, reflecting the many paths leading from i to j. The transition to Sij , via (5), allows us to treat each isolated interaction on its own, providing a direct observation into the microscopic interaction mechanism. Direct application of this fact could be the derivation of a rate equation that governs the system's dynamics from Gij, as well as predicting the universality class and the scaling laws governing the system's response to perturbations. Hence (5) helps translate the ever-growing amount of data on global correlations into valuable local information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Sharma, F. Simini, J. Menche, S. Rabello, G. Ghoshal, Y.-Y Liu, T. Jia, M. Pósfai, C. Song, Y.-Y. Ahn, N. Blumm, D. Wang, Z. Qu, M. Schich, D. Ghiassian, S. Gil, P. Hövel, J. Gao, M. Kitsak, M. Martino, R. Sinatra, G. Tsekenis, L. Chi, B. Gabriel, Q. Jin and Y. Li for discussions, and S.S. Aleva, S. Morrison J. De Nicolo and A. Pawling for their support. This work was supported by the National Institute of Health, Center of Excellence of Genomic Science (CEGS), Grant number NIH CEGS 1P50HG4233; and the National Institute of Health, Award number 1U01HL108630-01; DARPA Grant Number 11645021; The DARPA Social Media in Strategic Communications project under agreement number W911NF-12-C-0028; the Network Science Collaborative Technology Alliance sponsored by the US Army Research Laboratory under Agreement Number W911NF-09- 02-0053; the Office of Naval Research under Agreement Number N000141010968 and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency awards WMD BRBAA07-J-2-0035 and BRBAA08-Per4-C-2-0033.

Footnotes

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Vendruscolo M. In: Networks in Cell Biology. Buchanan M, Caldarelli G, De Los Rios P, Rao F, editors. Cambridge University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ideker T, Sharan R. Protein networks in disease. Genome Res. 2008;18:644–652. doi: 10.1101/gr.071852.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kann MG. Protein interactions and disease: Computational approaches to uncover the etiology of diseases. Briefings in Bioinformatics. 2007;8:333–346. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbm031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albert R. Scale-free networks in cell biology. Journal of Cell Science. 2005;118:4947–57. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barabási A-L, Oltvai ZN. Network biology: understanding the cell's functional organization. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2004;5:101–113. doi: 10.1038/nrg1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vidal M, Cusick ME, Barabási A-L. Interactome networks and human disease. Cell. 2011;144(6):986–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rual JF, et al. Towards a proteome-scale map of the human protein-protein interaction network. Nature. 2005;437:1173–8. doi: 10.1038/nature04209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu H, et al. High-quality binary protein interaction map of the yeast interactome network. Science. 2008;322:104–110. doi: 10.1126/science.1158684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braun P, et al. An experimentally derived confidence score for binary protein-protein interactions. Nature Methods. 2009;6:91–97. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krogan NJ, et al. Global landscape of protein complexes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2006;440:637–43. doi: 10.1038/nature04670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costanzo M, et al. The Genetic landscape of a cell. Science. 2010;327:425–431. doi: 10.1126/science.1180823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramani AK, et al. A map of human protein interactions derived from co-expression of human mRNAs and their orthologs. Molecular Systems Biology. 2008;4:180–195. doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barzel B, Biham O. Quantifying the connectivity of a network: The network correlation function method. Phys. Rev. E. 2009;80:046104. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.80.046104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eisen M, et al. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:9212–17. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Butte AJ, Kohane IS. Mutual information relevance networks: functional genomic clustering using pairwise entropy measurements. Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing. 2000;5:415–426. doi: 10.1142/9789814447331_0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Margolin AA, et al. ARACNE: An algorithm for the reconstruction of gene regulatory networks in a mammalian cellular context. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:S7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-S1-S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo S, et al. Uncovering interactions in the frequency domain. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2008;4(5):e1000087. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faith JJ, et al. Large-scale mapping and validation of Escherichia coli transcriptional regulation from a compendium of expression profiles. PLoS Biol. 2007;5(1):e8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marbach D, et al. Wisdom of crowds for robust gene network inference. Nature Methods. 2012;9:796–804. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lezon TR, et al. Using the principle of entropy maximization to infer genetic interaction networks from gene expression patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:19033–38. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609152103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma S, et al. An Arabidopsis gene network based on the graphical Gaussian model. Genome Research. 2007;17(11):1614–25. doi: 10.1101/gr.6911207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lide H, Jun Z. Using matrix of thresholding partial correlation coefficients to infer regulatory network. BioSystems. 2008;91:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystems.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen L, Zheng S. Studying alternative splicing regulatory networks through partial correlation analysis. Genome Biology. 2009;10:R3. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-1-r3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng J, et al. Partial correlation estimation by joint sparse regression models. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2009;104(486):735–746. doi: 10.1198/jasa.2009.0126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yuan Y, et al. Directed Partial Correlation: inferring large-scale gene regulatory network through induced topology disruptions. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(4):e16835. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adamic LA, Adar E. Friends and neighbors on the web. Social Networks. 2003;25(3):211. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alon U. An introduction to systems biology: design principles of biological circuits. Chapman & Hall; London, U.K.: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karlebach G, Shamir R. Modeling and analysis of gene regulatory networks. Nature Reviews. 2008;9:770–780. doi: 10.1038/nrm2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caldarelli G, Capocci A, De Los Rios P, Muñoz MA. Scale-free networks from varying vertex intrinsic fitness. Physical Review Letters. 2002;89:258702. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.258702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Y-Y, Slotine J-J, Barabási A-L. Observability of complex systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110(7):2460–65. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215508110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Erdös P, Rényi A. On the evolution of random graphs. Publications of the Mathematical Institute of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. 1960;5:17–61. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Albert R, Jeong H, Barabási A-L. Error and attack tolerance of complex networks. Nature. 2000;406:378–482. doi: 10.1038/35019019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen R, Erez K, Ben-Avraham D, Havlin S. Resilience of the Internet to random breakdowns. Physical Review Letters. 2000;85:214626–28. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.4626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bollobás B. Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics. Cambridge University Press; 2001. The Evolution of Random Graphs–the Giant Component. pp. 130–159. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stauffer D, Aharony A. Introduction to percolation theory. CRC Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohen R, Havlin S. Complex networks: structure, robustness and function. Cambridge University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Venkatesan K, et al. An empirical framework for binary interactome mapping. Nature Methods. 2009;6:83–89. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kauffman S. The ensemble approach to understand genetic regulatory networks. Physica A. 2004;340:733–740. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2003.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marks DS, Hopf TA, Sander C. Protein structure prediction from sequence variation. Nature Biotechnology. 2012;30(11):1072–80. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barabási A-L, Albert R. Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science. 1999;286:509–512. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Albert R, Barabási A-L. Statistical mechanics of complex networks. Reviews of Modern Physics. 2002;74:47–97. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caldarelli G. Scale-Free Networks. Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.