Abstract

Meropenem, a broad-spectrum parenteral β-lactam antibiotic, in combination with clavulanate has recently shown efficacy in patients with extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. As a result of meropenem’s short half-life and lack of oral bioavailability, the development of an oral therapy is warranted for TB treatment in underserved countries where chronic parenteral therapy is impractical. To improve the oral absorption of meropenem, several alkyloxycarbonyloxyalkyl ester prodrugs with increased lipophilicity were synthesized and their stability in physiological aqueous solutions and guinea pig as well as human plasma was evaluated. The stability of prodrugs in aqueous solution at pH 6.0 and 7.4 was significantly dependent on the ester promoiety with the major degradation product identified as the parent compound meropenem. However, in simulated gastrointestinal fluid (pH 1.2) the major degradation product identified was ring-opened meropenem with the promoiety still intact, suggesting the gastrointestinal environment may reduce the absorption of meropenem prodrugs in vivo unless administered as an enteric-coated formulation. Additionally, the stability of the most aqueous stable prodrugs in guinea pig or human plasma was short, implying a rapid release of parent meropenem.

Keywords: Meropenem, β-lactam prodrugs, aqueous stability, XDR-TB

1. Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), the main bacterium that causes the disease tuberculosis (TB), is estimated to latently infect more than 2 billion people and resulted in 1.4 million deaths in 2011.1 TB is considered one of the most challenging bacterial infections to cure due to the ability of Mtb to switch its metabolism to a non-replicating drug-tolerant state, which in turn necessitates prolonged antibiotic therapy.2 The standard treatment regimen developed by the British Medical Research Council uses a combination therapy of isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol given daily for 2 months followed by a 4–7month continuation phase of isoniazid and rifampin.3 Unfortunately, the emergence of multidrug- and extensively drug resistant (MDR-, XDR-) TB is undermining the great advances made in the 20th century to control TB.1 Emergence of resistance highlights the need for new TB drugs with novel mechanisms of action that ideally target both replicating and non-replicating mycobacteria.4,5

Although β-lactams are the most widely administered class of antibiotics, they have never been systematically used in TB therapy. As early as 1941, it was shown that mycobacteria are resistant to penicillin6, and a report from 1949 documented the ability of Mtb to inactivate β-lactams.7 In the following decades, the ineffectiveness of β-lactams for TB was largely attributed to poor membrane penetration of the imposing outer mycobacterial cell barrier.8 A series of studies culminating in a 2009 report by Blanchard and co-workers shattered this long held dogma and demonstrated: 1) the intrinsic resistance of Mtb toward β-lactams results from a chromosomally-located extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) encoded by the gene blaC, which hydrolyzes most β-lactams at the diffusion controlled rate, 2) BlaC is irreversibly inhibited by the β-lactamase inhibitor clavulanate, whereas other approved β-lactamase inhibitors are slowly hydrolyzed, and most importantly 3) inhibition of peptidoglycan synthesis is bactericidal under non-replicating conditions.9–13 Based on their kinetic studies, Blanchard and co-workers evaluated a combination of clavulanate with a wide variety of β-lactams. Meropenem (a β-lactam of the carbapenem class) was shown to exhibit the highest activity with minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) ranging from 0.03–1.25 µg/mL against 13 XDR-TB strains in the presence of 2.5 µg/ml clavulanate.13 Meropenem’s activity is likely a result of its binding to transpeptidases and endopeptidases (the M. tuberculosis penicillin binding proteins) as well its slow rate of inactivation by BlaC (has a kcat/KM value more than three orders of magnitude below the best substrates).12 These encouraging results were later confirmed in vivo in a murine TB model14 and in the clinic, with several case reports describing the successful use of this combination in patients with XDR-TB from the Russian Federation of Chechnya.15, 16 Meropenem and clavulanate are both FDA-approved drugs and are now available in less expensive generic forms (the patent for meropenem expired in 2010).

The major caveat to the treatment of TB with meropenem is the requirement of multiple intravenous infusions due to its negligible oral absorption and short 0.75–1-hour half-life,17 which is impractical for dosing of underserved populations where TB is most prevalent. Meropenem is a highly polar zwitterionic molecule (Log D < −2.5)18 and unstable in aqueous conditions and must therefore be given intravenously within 3 hours following aqueous reconstitution. Aqueous degradation products are derived from β-lactam hydrolysis (major) and β-lactam dimerization (minor) via intermolecular attack of the pyrrolidine nitrogen onto the β-lactam.19 Consequently, new derivatives or formulations of meropenem are required to improve stability, half-life, and oral bioavailability.

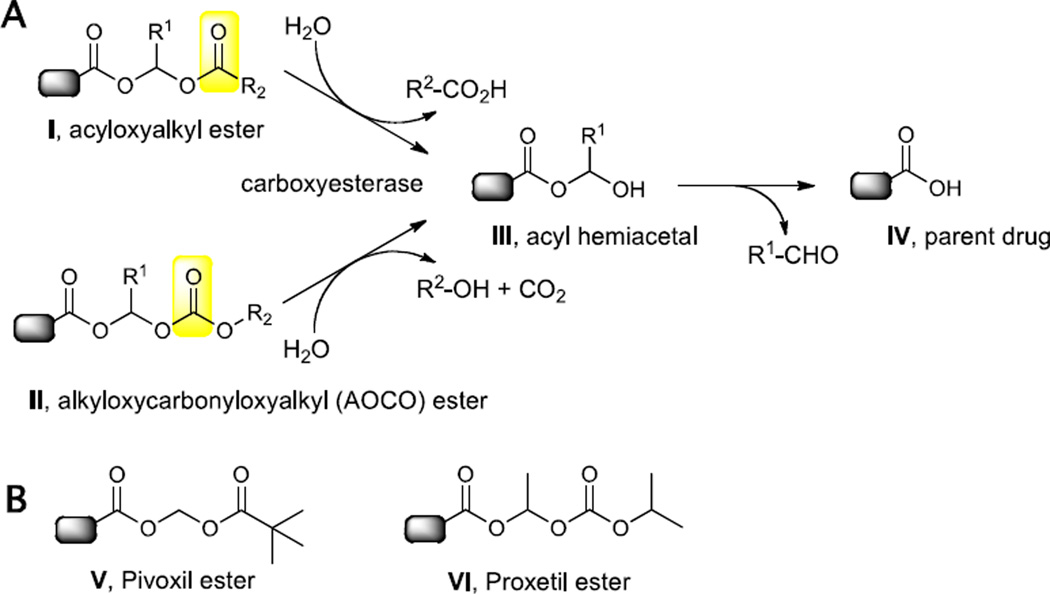

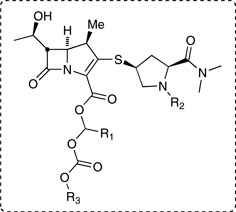

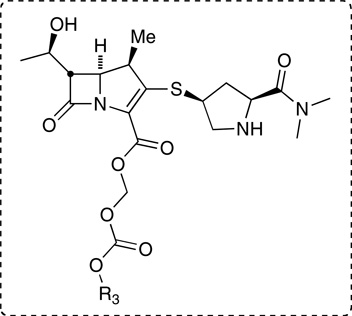

A standard approach to improve the oral absorption of β-lactams is to synthesize an ester prodrug that increases the lipophilicity and thereby improves the absorption through the gastrointestinal tract.20, 21, Once absorbed into the bloodstream, the ester prodrug is hydrolyzed by serum or tissue carboxyesterases to release the parent drug. Prodrug strategies for β-lactams employ acyloxyalkyl- (I) and related alkyloxycarbonyloxyalkyl (II) esters (Figure 1) where hydrolysis occurs at the remote carbonyl to afford an intermediate acyl-hemiacetal (III) that collapses with expulsion of an aldehyde and release of the parent β-lactam (IV). The hydrolysis rates and stability can be tuned by introducing steric bulk at the acyl position (R2 of I) or carbonate position (R2 for II) or the acetal linkage (R1) of I or II (Figure 1). Simple esters of β-lactams are ineffective since they enhance the hydrolytic lability of the β-lactam carbonyl22 and/or are incompletely hydrolyzed as found in cephalosporin and carbapenem β-lactams.20 Several acyloxyalkyl esters of carbapenems have been reported in an effort to improve the bioavailability of the parent carbapenem.23 The most advanced oral carbapenem in development is tebipenem pivoxil with bioavailabilities of 71, 59, and 35% in the mouse, dog, and monkey, respectively (see V, Figure 1 for the structure of the pivoxil ester).24 Meropenem bis-prodrugs with a pivoxil ester attached to the carboxylate and various acyloxymethyl carbamates attached to the pyrrolidine nitrogen were reported with bioavailabilities ranging from 27.0–29.5% in the rat and 24.4–38.4% in the beagle dog.18 Although pivoxil esters have been utilized as promoieties to improve the lipophilicity of β-lactam antibiotics, the released pivalic acid is a concern for chronic therapy such as TB. Pivalic acid enters into the branched-chained fatty acid acyl carnitine pathway and forms pivaloyl CoA, which is excreted as pivaloyl carnitine.25 Carnitine plays an essential role in fatty acid beta-oxidation, energy metabolism, and mitochondrial function and its depletion leads to serious side effects.26

Figure 1.

A. Ester prodrugs strategies for β-lactams and mechanism of release. Carboxyesterase catalyzes cleavage at the remote carbonyl (highlighted in yellow), which results in formation of an acyl hemiacetal intermediate that spontaneously breaks down to release the parent drug. B. Representative acyloxyalkyl and alkyloxycarbonyloxyalkyl (AOCO) promoieties found in clinically approved β-lactams.

In order to avoid generation of pivalic acid, we instead focused on alkyloxycarbonyloxyalkyl (AOCO) esters, which upon hydrolysis release an alcohol and carbon dioxide along with the parent β-lactam and aldehyde linker. One successful AOCO prodrug (cefpodoxime proxetil (VI), Figure 1) releases innocuous isopropanol upon prodrug cleavage. The extra methyl group at the acetal linkage of the proxetil ester compensates for the decreased steric bulk of the isopropoxy group (relative to the tert-butyl moiety in the related pivoxil prodrug). The primary drawback of the proxetil promoiety is the introduction of an additional stereocenter at the acetal linkage.

Herein we describe the synthesis and evaluation of a proxetil ester and novel bicyclic (benzosuberyl, tetralyl, and indanyl) alkyloxycarbonyloxyalkyl promoieties of meropenem in an effort to add significant lipophilicity to the parent molecule and ultimately improve oral absorption. We chose the bicyclo promoieties based on the first broad-spectrum penicillin prodrug carbenicillin indanyl (Geocillin) and the ability to release a soft non-toxic leaving group such as 5-hydroxyindane or 1- or 2-benzosuberol. Upon ester hydrolysis, a bicyclic alcohol is formed that is glucuronidated and rapidly excreted from the blood.27 We also hypothesized that the bulky bicyclic promoieties may obviate the methyl group on the bridging acetal found in the proxetil ester.

2. Results and discussions

2.1. Chemistry

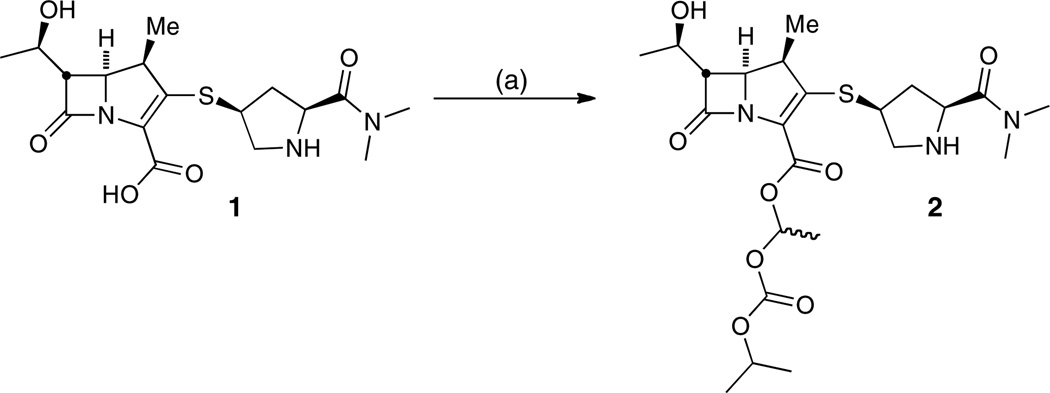

The synthesis of meropenem proxetil 2 was optimally performed by reacting meropenem 1 with 1.1 equivalents of freshly prepared 1-iodoethyl isopropyl carbonate28 and 4 equivalents of Cs2CO3 in DMF at 0 °C for 30 minutes (Scheme 1). Under these conditions, a total conversion of 98% was observed via HPLC analysis. The use of 1–8 equivalents of sodium or potassium carbonate as inorganic bases did not produce the product at an acceptable conversion rate (41′72%) compared with 4 equivalents of Cs2CO3 (Table 1). We hypothesize this improvement is based on the relatively large size of the caesium atom compared to sodium or potassium. Because of its size, the cesium coordinates to the carboxylate less efficiently and thus causes an increased nucleophilicity of the carboxylate. Moreover, under these conditions, the pyrrolidine nitrogen is not deprotonated and therefore not nucleophilic enough to attack the iodide reagent.

Scheme 1a.

aReaction conditions: (a) 1-iodoethyl isopropyl carbonate, Cs2CO3, DMF, 0 °C, 30 min, 64%.

Table 1.

Investigation of inorganic bases for the alkylation of meropenem (1) with 1-iodoethyl isopropyl carbonate

| Base | Equivalents | Reaction time (min) |

% Conversion HPLC |

|---|---|---|---|

| K2CO3 | 1 | 120 | 41 |

| 2 | 120 | 51 | |

| 4 | 45 | 62 | |

| 8 | 45 | 72 | |

| Na2 CO3 | 4 | 60 | 67 |

| Cs2CO3 | 2 | 60 | 81 |

| 4 | 30 | 98 |

| Table 1. Aqueous stability of meropenem and prodrugs at pH 7.4, 6.0, and 1.2. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Compound | HEPES pH 7.4 |

MES pH 6.0 |

SGF pH 1.2 |

| t1/2, mina OR (% remaining) at 120 minb | |||

| 2, diasteromer-1, R1 = R2 = H; R3 = i-Pr | (90%) | (94%) | 8.8 |

| 2, diastereomer-2, R1 = R2 = H; R3 = i-Pr | (87%) | (92%) | 9.8 |

| 17, R1 = R2 = H; R3 = (S)-1-indanyl | < 1 | n.d.c | n.d. |

| 20, R1 = R2 = H; R3 = (R)-1-indanyl | < 1 | n.d. | n.d. |

| 18, R1 = R2 = H; R3 = (S)-1-tetralyl | 1.4 | 0.90 | n.d. |

| 21, R1 = R2= H; R3 = (R)-1-tetralyl | 1.5 | 0.96 | n.d. |

| 19, R1 = R2 = H; R3 = (S)-1-benzosuberyl | 28 | 32 | 9.3 |

| 22, R1 = R2 = H; R3 = (R)-1-benzosuberyl | 27 | 32 | 11 |

| 23a, R1 = Me; R2 = H; R3= (S)-1-benzosuberyl | 64 | 80 | 18 |

| 24a, R1 = H; R2 = Ac; R3 = (S)-1-benzosuberyl | 28 | 28 | 7.0 |

| 37, R1 = R2 = H; R3 = 2-indanyl | (70%) | (96%) | 13 |

| 38, R1 = R2 = H; R3 = 2-tetralyl | (78%) | (93%) | 14 |

| 39, R1 = R2 = H; R3 = 2-benzosuberyl | (79%) | (96%) | 21 |

The hydrolysis of the prodrugs followed first-order degradation kinetics and the fractional rate of degradation (k) was determined by plotting the log of prodrug peak area vs. time. Half-lives (min) were determined by dividing the ln 2 by k (fractional rate of hydrolysis).

If a half-life was unable to be calculated, the % of prodrug remaining after a 120 min incubation is reported.

not determined

The purification of 2 from the reaction mixture proved extremely challenging owing to the poor stability of the compounds (vide infra), but was ultimately achieved by evaporating the DMF at 25 °C under reduced pressure followed by immediate silica gel purification with 10% methanol–CH2Cl2 and 1% NH4OH as the mobile phase to afford the compound as a white foam in 64% isolated yield.

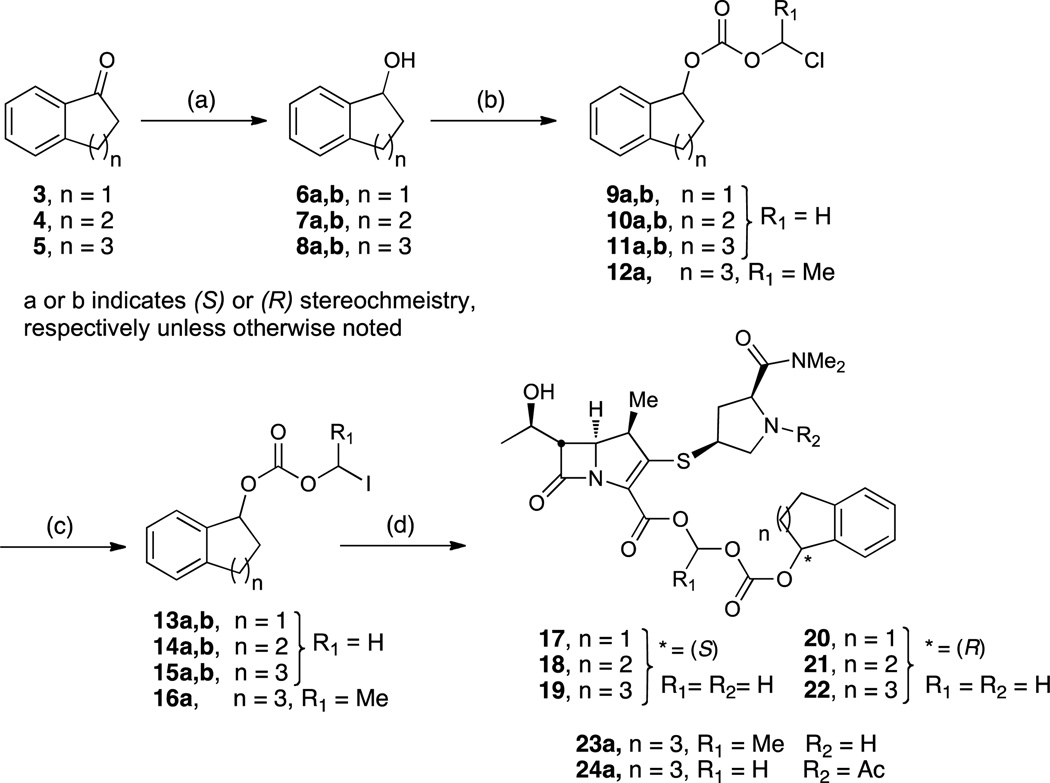

The synthesis of (R)- and (S)-1-indanyl-, 1-tetralyl-, and 1-benzosuberyl-oxycarbonyloxymethyl meropenem prodrugs are outlined in Scheme 2. Enantioselective reduction of commercially available ketones 3–5 employing either the (R) or (S) Corey-Bakshi-Shibata (CBS) catalyst and borane dimethylsulfide as the reducing agent provided the corresponding alcohols 6a,b–8a,b in enantiomeric ratios of 98:2 to 99:1 as determined by chiral HPLC. Treatment of the enantiopure alcohols with chloromethyl- or chloroethyl chloroformate afforded carbonates 9a,b–11a,b and 12a in excellent yields that were converted to the corresponding iodo derivatives 13a,b–15a,b and 16a by a Finkelstein reaction. Finally, the carboxylate of meropenem was alkylated with 2.3 equivalents of the respective iodomethyl or iodoethyl carbonate 13a,b–15a,b and 16a and 4 equivalents of Cs2CO3 in DMF at 0 °C resulting in a 90–95% conversion in 30 minutes. The reaction mixture was concentrated and subsequently purified by the aforementioned procedure to afford pure prodrugs 17–22 and 23a as white foams in moderate to excellent yields. Compound 24a was prepared by alkylation of 15a with N-acetyl meropenem, prepared in situ by treatment of meropenem 1 with acetic anhydride in DMF at 0 °C.

Scheme 2a.

aReaction conditions: (a) (+) or (-)-CBS, BH3⋅SMe3, THF, 0 °C–rt, quant. yield; (b) for 12a: ClCO2CH(CH3)Cl, pyridine, CH2Cl2, rt, 30 min, 85%; for 9a,b–11a,b: ClCO2CH2Cl, pyridine, CH2Cl2, rt, 30 min, 76–98%; (c) NaI, acetone, 40 °C, 5 h, 25% for 16a, 70–95% for 13a,b-15a,b; (d) for 17–22 and 23a: 1, Cs2CO3, DMF, 0 °C, 30 min, 57–84%; for 24a: i) Ac2O, 1, DMF, 0 °C, 15 min; ii) then add 16a, 30 min, 0 °C, 62%

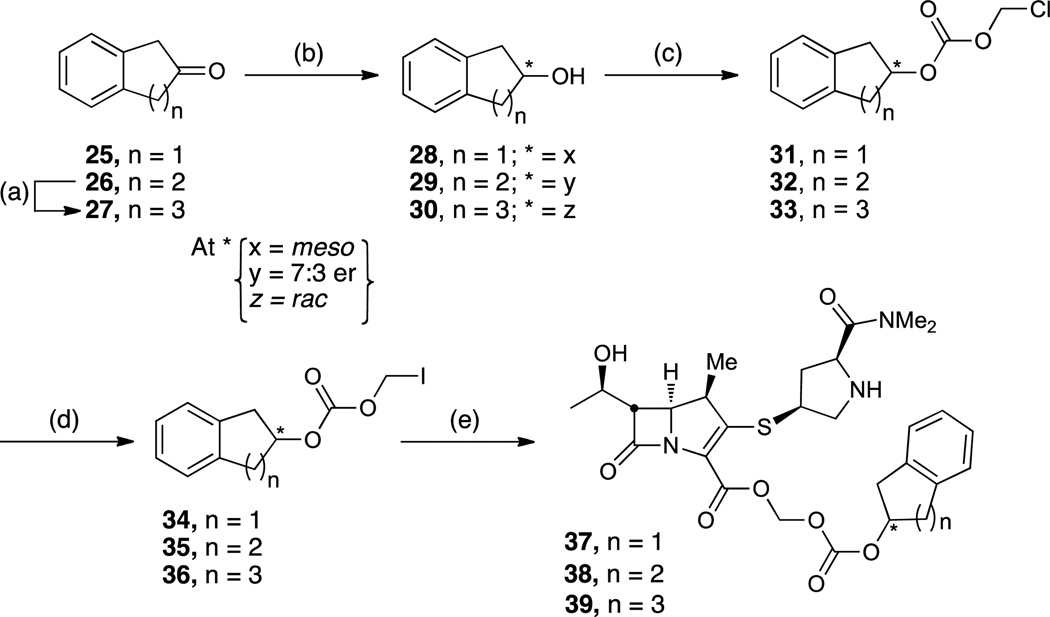

The synthesis of the 2-indanyl-, 2-tetralyl-, and 2-benzosuberyl- oxycarbonyloxymethyl esters of meropenem 37–39 are presented in Scheme 3. The synthesis of 2-benzosuberone 27 was accomplished in three steps from 1-tetralone 4 by following established procedures described elsewhere.29, 30 The enantioselective reduction of 2-benzosuberone 27 and 2-tetralone 26 to the corresponding (R)- and (S)-alcohols was attempted with the (R)- or (S)-CBS catalyst and borane dimethyl sulfide as the reducing agent by the aforementioned procedure. However, the reaction was not enantioselective for 2-benzosuberone 27 and only the racemic alcohol was produced. Reduction of 2-tetralone 26 was modestly enantioselective providing an enantiomeric ratio of 7:3. The remarkable difference in enantioselectivity between the 1- and 2-substituted ketones may be attributed to the difference in their respective aryl ketone substituent sizes.31 With the alcohol at the benzylic position (1-series), the substituents on either side of the ketone differ decisively with a benzene ring on one side and an aliphatic chain on the other. In contrast, when the ketone is surrounded by two neighboring methylene groups, as in the case of the 2-series, the two substituents are relatively similar on a proximate scale. Therefore, the chiral induction can be significantly reduced, which results in low to no selectivity. Since 2-indanol 28 is an achiral molecule, no enantioselective reduction is required and a simple NaBH4 reduction in MeOH of 2-indanone 25 afforded 2-indanol 28. The chloromethyl and iodomethyl carbonate intermediates 31–36, and final prodrug molecules 37–39 were prepared as previously described in Scheme 2. For both the 2-tetralyl 38 and 2-benzosuberyl 39, a mixture of diastereomers was isolated in each case.

Scheme 3a.

aReaction Conditions: (a) Ref. 29, 30; (b) for 28: NaBH4, MeOH, rt, 97%; for 29–30: CBS, BH3·SMe3, THF, 0 °C–rt, 68–89%; (c) ClCO2CH2Cl, pyridine, CH2Cl2, rt, 30 min, 70–94%; (d) NaI, acetone, 40 °C, 5 h, 62–70%; (e) 1, Cs2CO3, DMF, 0 °C, 30 min, 68–84%.

2.2. Prodrug aqueous stability

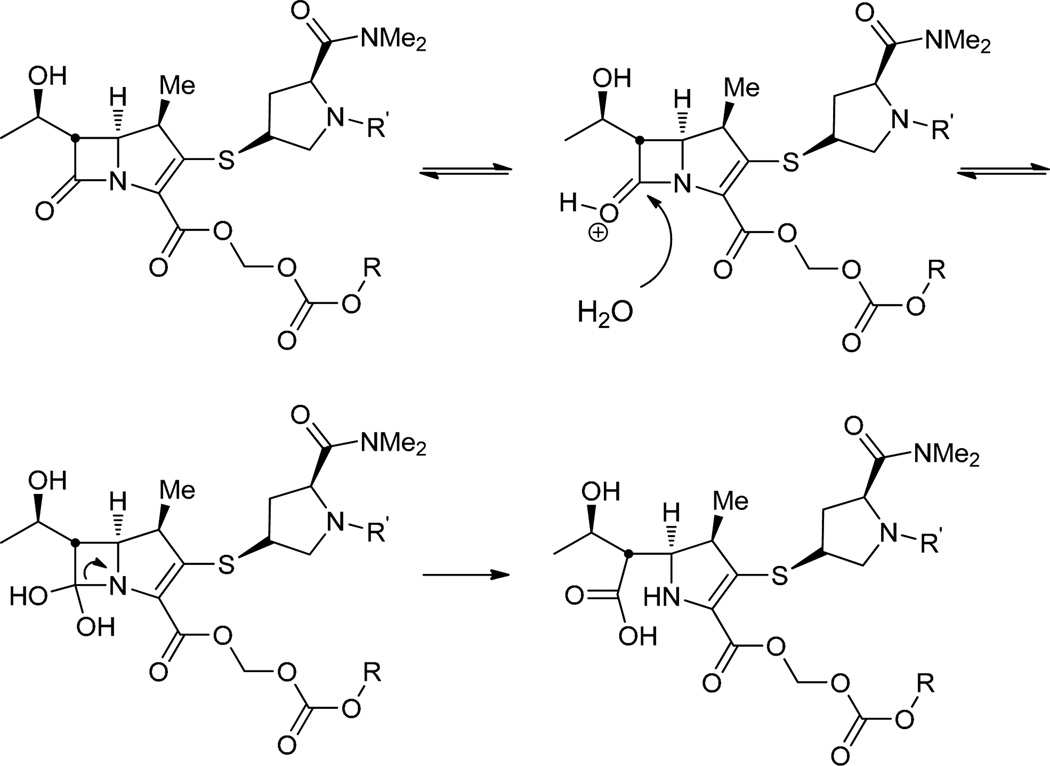

Aqueous stability was determined at pH 7.4, 6.0, and 1.2, which simulates physiological, intestinal, and gastric pH, respectively. We initially evaluated the aqueous stability of our first synthesized prodrug, meropenem proxetil 2. At physiological pH 7.4, only 10 and 13% of each diastereomer was hydrolyzed to 1 in a period of 2 hours. At intestinal pH 6.0, similarly slow hydrolysis was apparent; however, in simulated gastric fluid (pH 1.2), the half-life of each diastereomer was 9.8 and 8.8 minutes. To our surprise, the major degradation product was identified as the β-lactam ring-opened metabolite with the proxetil promoiety still intact, which was identified by HRMS (LC-TOF, calcd for C23H37N3O9S (ESI−): 530.2178, found 530.2185 (error 1.3ppm)). This supports the assumption that the ester linkage is stable at acidic pH. However, the promoiety does not protect the β-lactam bond from acidic hydrolysis. Recently, the stability of meropenem (carbapenem), cefotaxime (cephalosporin), ceftibuten (cephalosporin), and faropenem (penem) were investigated in simulated gastric fluid, pH 1.2 without enzymes.32 Meropenem was observed to possess the shortest half-life compared to the other β-lactams showing 80% degradation in about 30 minutes. The amount of meropenem, cefotaxime, ceftibuten, and faropenem remaining after 60 minutes in simulated gastric fluid was 5, 65, 94, and 70%, respectively. Although the reason for the instability of meropenem was not discussed, we hypothesize it stems from the increased torsional and angle strain of the carbapenem scaffold compared with other types of β-lactams.

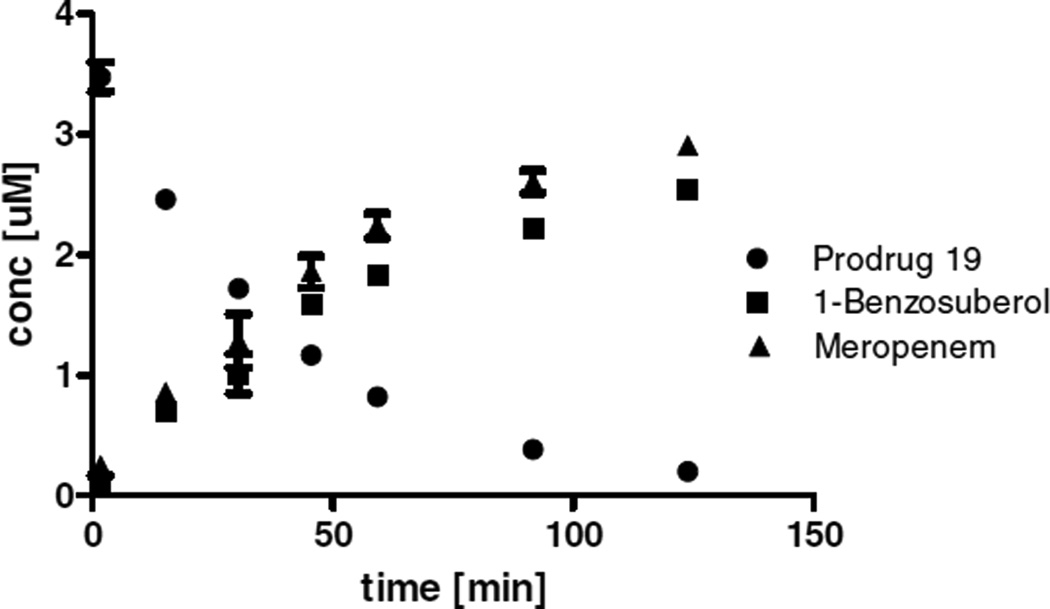

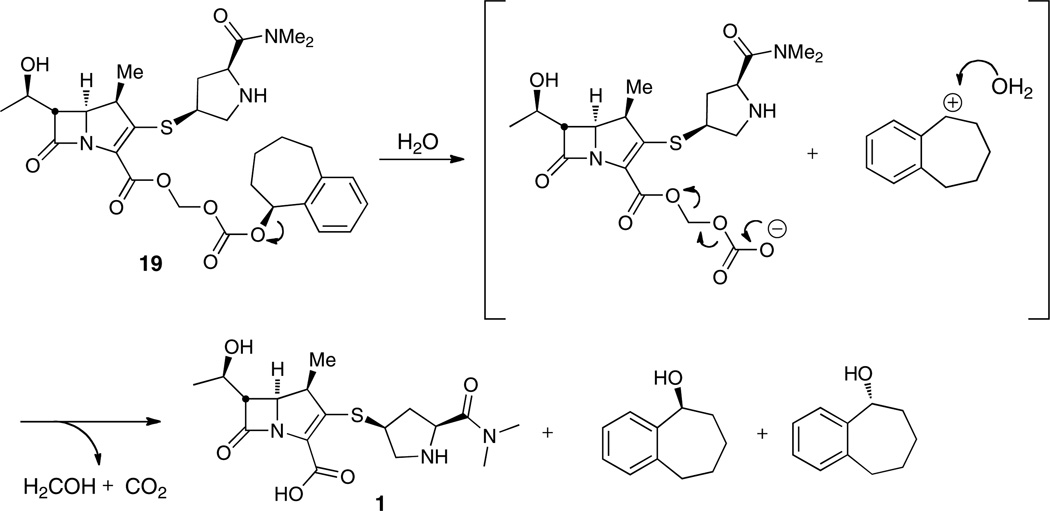

The aqueous stability of the 1-bicyclo series of meropenem prodrugs was subsequently investigated. Interestingly, the stability of prodrugs 17–22 decreases with ring size of the bicyclic promoiety at both physiological and intestinal pH. The stereochemistry of the alcohol substituent, however, has no impact on reactivity (Table 1). This trend in stability might be an indication that the smaller ring size means less steric bulk and thus less shielding of the proximate functionals groups including the β-lactam from the acidic environment. Relative to the proxetil prodrug at all measured pH’s, the 1-bicyclo prodrugs were remarkably less stable as evidenced by their short half-lives. Prodrugs with the 1-benzosuberyl promoiety (19 and 22) were 20 and 37 times more stable to hydrolysis compared with the 1-tetralyl (18 and 21) and 1-indanyl (17 and 20) containing prodrugs at physiological and intestinal pH, respectively. Hydrolytical stability at physiologic vs. intestinal pH, however, differed only slightly for both derivatives. Consequently, the major degradation products identified at pH 6 and 7.4 was the expected parent compound meropenem as well as the corresponding alcohol (Figure 2). We suspected the lower stability of the 1-bicyclo series compared to 2 to be a result of the missing methyl group and therefore less bulk at the acetal linkage. We thus hypothesized that the addition of such a methyl group at the acetal linkage of prodrug 19 (analogous to the proxetil ester 2) would decrease the hydrolysis rate. The prodrug with the additional methyl group 23a improved the stability about 2-fold at all pH values, supporting our former assumption. We also postulated that the secondary nitrogen in the pyrrolidine ring may attack the electrophilic carbonate or ester groups of the promoiety. Subsequently, the N-acetyl derivative 24a was synthesized; however, there was no significant change in the hydrolysis rate (Table 1). To fully understand the mechanism of hydrolysis 19 was incubated at 37 °C for 4 hours in 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 and the solution was evaporated to dryness. The residue was dissolved in n-heptane and injected onto a normal phase HPLC column using the conditions described in Chiral HPLC method 3. To our surprise, the racemic alcohol was identified demonstrating that hydrolysis takes place via an SN1 solvolysis mechanism (Scheme 4) instead of an attack on the carbonate or carboxylate functional groups. This process is favored due to the attachment of the carbonate at the benzylic position of the bicyclic ring system, where a positive charge can be stabilized through the π-system of the aryl ring.

Figure 2.

Aqueous stability of prodrug 19 at pH 7.4. The concentration of (●) prodrug 19, the released meropenem (▲), and 1-benzosuberol (■) are shown. The concentration for each species is plotted as a function of incubation time. All measurements were performed in triplicate and error bars represent the standard deviation.

Scheme 4.

As a result of the poor aqueous stability of the benzylic 1-series of bicyclic prodrugs, we synthesized homobenzylic 2-substituted analogues from the corresponding 2-ketones (Scheme 3). In that case the alcohol would not be at the benzylic position any more, which should prevent SN1 hydrolysis at the alcohol. Indeed, prodrugs 37–39 showed substantially improved stability at physiological and intestinal pH (70 – 96% remaining) compared with the 1-series (<1 – 28 min half-lives) due to their inability to form a benzylic cation (Table 1). Additionally, the 2-substituted series of prodrugs were somewhat more stable (15%) at intestinal pH relative to physiological pH. The stability was also investigated in simulated gastric fluid to determine the rate of hydrolysis in the stomach. In each case, half-lives ranged from 13 – 20 minutes and the major degradation product identified by mass spectrometry was the β-lactam ring-opened metabolite with the promoiety still intact (scheme 5), similar to what was observed with meropenem proxetil 2.

Scheme 5.

2.3. Plasma stability

The prodrugs with the longest stability in aqueous solution at physiological and intestinal pH were further investigated for their stability in guinea pig plasma. The diastereomers of meropenem proxetil 2 had significantly different plasma stabilities, 7.1 and 1.4 minutes, that can be attributed to their different specificities for carboxylesterases as previously described for the proxetil and related axetil promoieties.33 The half-lives of compounds 2, 19, 22, 37–39 range from 0.9 to 1.9 minutes, indicating poor plasma stability (Table 2).

Table 2.

Guinea pig and human plasma stability of meropenem and selected prodrugs.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Compound | t1/2 (min) Guinea Pig |

t1/2 (min) Human |

| 2, R3 = i-Pr (Diastereomer 1) | 6.5±1.5 | 108±12 |

| 2, R3 = i-Pr (Diastereomer 2) | 1.4±0.23 | 11±1.0 |

| 19, R3 = (S)-1-benzosuberyl | 1.3±0.26 | 44±1.8 |

| 22, R3 = (R)-1-benzosuberyl | 0.9±0.10 | 34±3.3 |

| 37, R3 = 2-indanyl | 0.9±0.51 | 4.3±0.74 |

| 38, R3 = 2-tetralyl | 1.7±0.05 | 8.1±0.38 |

| 39, R3 = 2-benzosuberyl | 1.9±0.08 | 23±0.87 |

As human plasma generally contains less carboxylesterases than rodent plasma, we determined the stability of those compounds in human plasma as well. The half-lives were increased significantly. While the hlaf-lives for 37 and 38 were still very short with 4.3 and 8.1 min, the half-life for all benzosuberyl prodrugs increased to 23–44 min with a difference of 10 min for the two different diastereomers 19 and 22. This, again, can probably be attributed to the different specificities for carboxylesterases. The half-lives of the two proxetil diastereomers were very different with 11 and 108 min. The orientation of the methyl group at the acetal linkage, which adds to the steric bulk close to the active center might be accountable for this remarkable difference. Kakumanu et al. found that the R isomer of cefpodoxime proxetil was metabolized more quickly than the S isomer in rat intestinal homogenates, confirming stereoselective hydrolysis of proxetil esters.34

3. Conclusions

Several alkyloxycarbonyloxyalkyl prodrugs of meropenem (1) were synthesized in an effort to improve the lipophilicity and oral absorption of the parent carbapenem. Thereby, high yields were obtained through established methods. Improved yields over conventional methods for coupling meropenem with an alkyl iodide were obtained with Cs2CO3. In addition, purification of the prodrugs was successfully achieved utilizing standard normal phase silica gel and a CH2Cl2–MeOH–NH4OH solvent system. The aqueous stability of prodrugs 2, 17–24, and 37–39 at biologically relevant pH 1.2 (stomach), 6.0 (intestinal), and 7.4 (blood) at 37 °C is reported in Table 1. The prodrugs containing the 1-benzosuberyl, 1-tetralyl, and 1-indanyl-oxycarbonyloxymethyl promoieties 17–24 were unstable in aqueous solution and resulted in the formation of a racemic alcohol indicative of an SN1 solvolysis mechanism. The prodrugs containing the 2-benzosuberyl, 2-tetralyl, and 2-indanyl-oxycarbonyloxymethyl promoieties 37– 39 were significantly more stable at physiological pH 7.4 and intestinal pH 6.0. In simulated gastric fluid (pH 1.2), the 1-series 17–24 degraded quickly and formed the β-lactam ring-opened parent molecule while the more stable 2-series 37–39 and 2 degraded to form the ring-opened prodrug metabolite. The guinea pig plasma stability of the most aqueous stable prodrugs was very short, half-lives in human plasma were somewhat longer. These low plasma stability implies a rapid esterase-catalyzed release of the parent compound 1. It is reasonable to assume that esterases located in both the intestine and liver may cleave the promoieties as efficiently as the plasma esterases, which would affect the oral absorption of the prodrugs. Overall, the work presented in this research article describes the facile synthesis of meropenem prodrugs with increased lipophilicity; however, caution should be exercised regarding the choice of promoiety for meropenem, and experiments must be conducted to ensure the stability of the prodrug is acceptable for future in vitro and in vivo investigations. The instability in stomach acid could be overcome with enteric-coated formulations. Modification of the ionizable pyrrolidine nitrogen (e.g. carbamate prodrugs) could be used to slow the production of meropenem and this strategy has been explored previously.18

4. Experimental section

4.1. Chemistry

Meropenem was purchased from A.G Scientific (San Diego, CA) and all other chemical reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Flash chromatography was performed using a Combiflash Companion® equipped with flash column silica cartridges with the indicated solvent system. Solvents for chromatography (CH2Cl2, MeOH, EtOAc, hexanes, and NH4OH) were all purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). 1H and 13C NMR spectra were obtained from a Varian 600 MHz spectrometer. Proton chemical shifts (δ) are reported in ppm from an internal standard of chloroform (7.26) or dichloromethane (5.32). Carbon chemical shifts are reported using an internal standard of residual chloroform (77.23) or dichloromethane (54.00). Proton chemical data are reported as follows: chemical shift, multiplicity (s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, m = multiplet, br = broad, ovlp = overlapping), coupling constant, and integration. High-resolution mass spectra were obtained on an Agilent TOF II TOF/MS instrument equipped with an ESI probe.

4.2. General procedures

4.2.1. General procedures (A) for the enantioselective reduction of ketones (3–5)

To a solution of (R)-(+)-2-methyl-CBS-oxazaborolidine or (S)-(–)-2-methyl-CBS-oxazaborolidine (0.2 equiv) in THF (1 mL/0.21 mmol ketone) at 0 °C was added a 2.0 M solution of borane dimethyl sulfide in THF (1.2 equiv). The mixture was stirred for 15 min then a solution of ketone (1.0 equiv) in THF (1 mL/0.21 mmol ketone) was cannulated dropwise into the reaction mixture. After stirring for 30 min, the reaction was quenched by the addition of MeOH (1 mL/0.75 mmol of BH3·SMe2), then concentrated under reduced pressure to afford colorless oils that solidified overnight at –20 °C. The (R)-CBS reagent produced the (S)-alcohols (6a–8a) and the (S)-CBS produced the (R)-alcohols (6b–8b).

4.2.2. General procedure (B) for the synthesis of chloroalkylcarbonates (9a,b–11a,b, 12a, and 31–33)

To a solution of alcohols (6a,b–8a,b, and 28–30) (1.0 equiv) in CH2Cl2 (0.1 M) at 23 °C was added pyridine (2 equiv) and the reaction was stirred for 15 min. Next, chloromethyl or chloroethyl chloroformate (2.0 equiv) was added dropwise and the resulting solution was stirred for 30 min at 23 °C. The reaction mixture was washed consecutively with H2O, 1 N aqueous HCl, and saturated aqueous NaCl. The organic layer was dried (MgSO4), filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to afford the crude product, which was taken on to the next step without any further purification due to instability on silica gel.

4.2.3. General procedure (C) for the synthesis of iodoalkylcarbonates (13a,b–15a,b, 16a, and 34–36)

To a solution of chloroalkylcarbonates (9a,b–11a,b and 12a) (1.0 equiv) and 4 Å molecular sieves (0.5 g) in acetone (0.2 M) was added sodium iodide (3.0 equiv). The solution was stirred for 5 h in the dark at 40 °C. Subsequently, the reaction mixture was filtered and evaporated under reduced pressure to yield an orange solid, which was dissolved in Et2O and washed consecutively with 10% Na2SO3, H2O, and saturated aqueous NaCl. The organic layer was dried over MgSO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure to afford the crude product. Purification was not performed due to the instability of the molecules.

4.2.4. General procedure (D) for the synthesis of meropenem prodrugs (17–22, 23a, 24a, and 37–39)

A solution of meropenem (100 mg, 1.0 equiv) and Cs2CO3 (367 mg, 1.04 mmol 4.0 equiv) in DMF (1.3 mL) was stirred at 0 °C for 10 min. Next, a solution of the crude iodoalkylcarbonate (0.6 mmol, 2.3 equiv) in DMF (1.3 mL) was added dropwise to the reaction mixture. After stirring for 20 min at 0 °C, the reaction mixture was evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure. Purification by flash chromatography (10% MeOH–CH2Cl2 with 1% NH4OH) afforded the title compounds as white foams.

4.3. Chemical Synthesis

4.3.1. (S)-1-Indanol (6a)

Synthesized from 1-indanone 3 (1.00 g, 7.57 mmol, 1.0 equiv) using general procedure A. Purification by flash chromatography (10% EtOAc–hexanes) afforded the title compound (1.01 g, quant.): er = 99:1 (Chiral HPLC, method 1); Analytical data matched previously reported values.27

4.3.2. (R)-1-Indanol (6b)

This compound was prepared similarly to 6a except (S)-(+)-2-methyl-CBS-oxazaborolidine was utilized as the enantioselective catalyst to afford the title compound (1.01 g, quant.): er = 99:1 (Chiral HPLC, method 1); Analytical data matched previously reported values.27

4.3.3. (S)-1-Tetralol (7a)

Synthesized from 1-tetralone 4 (1.00 g, 6.84 mmol, 1.0 equiv) following general procedure A. Purification by flash chromatography (10% EtOAc–hexanes) afforded the title compound (1.12 g, quant.): er = 99:1 (Chiral HPLC, method 2); Analytical data matched previously reported values.27 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.80 (m, 1H), 1.93 (m, 1H), 2.00 (m, 2H), 2.74 (ddd, J = 16.8, 7.8, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 2.85 (dt, J = 16.8, 5.4 Hz, 1H), 4.80 (m, 1H).

4.3.4. (R)-1-Tetralol (7b)

This compound was prepared analogously to 7a, but (S)-(+)-2-methyl-CBS oxazaborolidine was employed as the enantioselective catalyst to afford the title compound (1.02 g, quant.): er = 98:2 (Chiral HPLC, method 2); Analytical data matched previously reported values.27

4.3.5. (S)-1-Benzosuberol (8a)

Synthesized from 1-benzosuberone 5 (1.00 g, 6.24 mmol, 1.0 equiv) using general procedure A. Purification by flash chromatography (10% EtOAc–hexanes) afforded the title compound (974 mg, 96%) as a white solid: er = 98:2 (Chiral HPLC, method 3);Analytical data matched previously reported values. 27 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.48 (m,1H), 1.80 (m, 3H), 1.96 (m, 1H), 2.06 (m, 1H), 2.72 (dd, J = 14.4, 10.8 Hz, 1H), 2.93 (dd, J = 14.1, 8.8 Hz, 1H), 4.93 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.10 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.16 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.21 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H).

4.3.6. (R)-1-Benzosuberol (8b)

This compound was prepared analogously to 8a, but (S)-(–)-2-methyl-CBS-oxazaborolidine was employed as the enantioselective catalyst to afford the title compound (1.02 g, 99%) as a white solid: er = 99:1 (Chiral HPLC, method 3); Analytical data matched previously reported values.27

4.3.7. 2-Indanol (28)

To a solution of 2-indanone 25 (1.0 g, 7.5 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in MeOH (150 mL) was added NaBH4 (500 mg, 12.2 mmol, 1.7 equiv) portionwise. The reaction was stirred 10 min then diluted with H2O (75 mL) and extracted with Et2O (2× 100 mL). The organic layer was dried (MgSO4), filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to afford the crude product as a brown solid in quantitative yield. The product was utilized in the following step without further purification: Rf = 0.26 (20% EtOAc-Hexanes 1% Formic Acid); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.86 (br s, 1H), 2.91 (dd, J = 16.4, 2.9 Hz, 2H), 3.21 (dd, J = 16.4, 5.9 Hz, 2H), 4.68 (m, 1H), 7.18 (dd, J = 5.4, 3.6 Hz, 2H), 7.25 (dd, J = 5.4, 3.6 Hz, 1H).

4.3.8. 2-Tetralol (29)

Synthesized from 2-tetralone 26 (1.00 g, 6.84 mmol, 1.0 equiv) following general procedure A. Purification by flash chromatography (20% EtOAc–hexanes) afforded the title compound (1.0 g, quant) as a colorless oil: Rf = 0.12 (20% EtOAc–hexanes); er = 7:3 (Chiral HPLC, method 2); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.61 (m, 1H), 1.83 (dtd, J = 12.5, 9.3, 5.9 Hz, 1H), 2.07 (m, 1H), 2.78 (dd, J = 16.1, 7.9 Hz, 1H), 2.85 (ddd, J = 16.2, 9.6, 6.6 Hz, 1H), 2.96 (dt, J = 16.8, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 3.10 (dd, J = 16.1, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 4.17 (m, 1H), 7.10 (m, 4H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 27.0, 31.5, 38.4, 67.2, 125.9, 126.0, 128.6, 129.5, 134.2, 135.6; HRMS (APCI+) calcd for C10H11 [M – OH] + 131.0855, found 131.0857 (error 1.5 ppm).

4.3.9. 2-Benzosuberol (30)

Synthesized from 2-benzosuberone 27 29, 30 following general procedure A. Purification by flash chromatography (20% EtOAc–Hexanes) afforded the title compound as a colorless oil that solidified overnight (97 mg, 89%): Rf = 0.42 (20% EtOAc– Hexanes); er = 1:1 (Chiral HPLC, method 3); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.56 (m, 1H), 1.88 (m, 2H), 2.08 (s, 1H), 2.13 (m, 1H), 2.78 (m, 1H), 2.80 (m, 1H), 3.01 (d, J = 13.2 Hz, 1H), 3.09 (dd, J = 13.2, 9.0 Hz, 1H), 3.82 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.12 (m, 1H), 7.16 (t, J = 4.4 Hz, 2H), 7.19 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ24.4, 35.5, 40.6, 44.7, 69.3, 126.2, 126.6, 128.8, 130.5, 136.5, 143.4; HRMS (APCI+) calcd for C11H13 [M – OH]+ 145.1012, found 145.1013 (error 0.7 ppm).

4.3.10. (S)-Indan-1-yl chloromethylcarbonate (9a)

The title compound) The title compound was prepared from (S)-1-indanol 6a (998 mg, 7.43 mmol, 1.0 equiv) according to general procedure B to afford a yellow oil (1.6 g, 98%), which was directly taken onto the next step without further purification due to instability on silica gel: Rf = 0.77 (20% EtOAc–Hexanes).

4.3.11. (R)-Indan-1-yl chloromethylcarbonate (9b)

This title compound was prepared analogously to 9a, but with (R)-1-indanol 6b to afford a yellow oil (1.6 g, 97%).

4.3.12. (S)-Tetral-1-yl chloromethylcarbonate (10a)

Synthesized from (S)-1-tetralol 7a (1.12 g, 7.6 mmol, 1.0 equiv) according to general procedure B. Purification by flash chromatography (1% EtOAc–hexanes) afforded the title compound (1.68 g, 92%) as a yellow oil: Rf = 0.58 (20% EtOAc–hexanes); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.82–1.89 (m, 1H), 1.96–2.07 (m, 2H), 2.14– 2.20 (m, 1H), 2.73–2.79 (m, 1H), 2.85–2.91 (m, 1H), 5.74 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 5.77 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 5.92 (m, 1H), 7.14 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 7.18–7.20 (m, 1H), 7.24–7.29 (m, 1H), 7.36 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHZ, CDCl3) δ 18.3, 28.7, 28.8, 72.2, 75.8, 126.2, 128.7, 129.2, 129.7, 132.9, 137.9, 153.2.

4.3.13. (R)-Tetral-1-yl chloromethylcarbonate (10b)

The title compound was prepared analogously to 10a, but with (R)-1-tetralol 7b to afford a yellow oil (1.4 g, 94%).

4.3.14. (S)-Benzosuber-1-yl chloromethylcarbonate (11a)

Synthesized from (S)-1-benzosuberol 8a (973 mg, 6.0 mmol, 1.0 equiv) according to general procedure B. Purification by flash chromatography (1% EtOAc–hexanes) afforded the title compound (1.43 g, 94%) as a colorless oil: Rf = 0.14 (1% EtOAc–hexanes); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.62–1.77 (m, 2H), 1.84–1.93 (m, 1H), 1.94–2.01 (m, 1H), 2.03–2.13 (m, 2H), 2.75 (dd, J = 10.2, 4.2 Hz, 1H), 3.01 (dd, J = 11.4, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 5.72 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 5.79 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 5.87 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.14 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 7.18–7.23 (m, 1H), 7.32 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 26.9, 27.5, 33.1, 35.6, 72.2, 81.7, 126.1 (2C), 128.1, 129.9, 138.7, 141.4, 152.7.

4.3.15. (R)-Benzosuber-1-yl chloromethylcarbonate (11b)

The title compound was prepared analogously to 11a, with (R)-1-benzosuberol 8b to afford a colorless oil (1.2 g, 76%).

4.3.16. (1S, 1′S/R)-Benzosuber-1-yl chloroethylcarbonate (12a)

Synthesized from (S)-1-benzosuberol 8a (1.13 g, 6.99 mmol, 1.0 equiv) according to general procedure B employing chloroethyl chloroformate as the alkylating agent. Purification by flash chromatography (10% EtOAc–hexanes) afforded the title compound (1.60 g, 85%) as a 1:1 mixture of diastereomers at C-1′ as a colorless oil: Rf = 0.48 and 0.43 (10% EtOAc–hexanes); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.61 (m, 0.5H), 1.69 (m, 1H), 1.73 (m, 0.5H), 1.84 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 1.5H), 1.86 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 1.5H), 1.87 (m, 1H), 1.97 (m, 1.5H), 2.06 (m, 1.5H), 2.75 (m, 1H), 3.00 (m, 1H), 5.84 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 0.5H), 5.86 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 0.5H), 6.43 (q, J = 6.0 Hz, 0.5H), 6.47 (q, J = 6.0 Hz, 0.5H), 7.13 (m, 1H), 7.19 (m, 2H), 7.32 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 25.14, 25.18, 26.8, 27.1, 27.45, 27.55, 33.0, 33.3, 35.57, 35.58, 81.2, 81.5, 84.55, 84.60, 126.1, 126.2, 128.0, 128.1, 129.8, 129.9, 138.8, 138.9, 152.2, 152.3.

4.3.17. Indan-2-yl chloromethylcarbonate (31)

Synthesized from 2-indanol 28 (971 mg, 7.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv) according to general procedure B. Purification by flash chromatography (10% EtOAc–hexanes with 1% formic acid) afforded the title compound (1.53 g, 94%) as a white solid: Rf = 0.57 (10% EtOAc–hexanes with 1% formic acid); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.14 (br s, 1H), 3.17 (br s, 1H), 3.37 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 3.40 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 5.54 (br s, 1H), 5.74 (s, 2H), 7.21–7.23 (m, 2H), 7.25–7.28 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 39.3, 72.1, 80.5, 124.6, 127.0, 139.6, 153.1.

4.3.18. Tetral-2-yl chloromethylcarbonate (32)

Synthesized from 2-tetralol 29 (1.0 g, 6.8 mmol, 1.0 equiv) according to general procedure B. Purification by flash chromatography (hexane to 20% EtOAc–hexanes) afforded the title compound (1.14 g, 70% over two steps) as a colorless solid: Rf = 0.39 (20% EtOAc– hexanes); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 2.06 (m, 1H), 2.14 (m, 1H), 2.87 (dt, J = 16.8, 7.2 Hz, 1H), 2.97 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 2.99 (dd, J = 16.2, 6.6 Hz, 1H), 3.20 (dd, J = 16.7, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 5.18 (m, 1H), 5.73 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 5.75 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 7.08 (m, 1H), 7.11 (m, 1H), 7.15 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 26.2, 27.6, 34.3, 72.1, 75.3, 126.1, 126.3, 128.6, 129.3, 132.7, 135.1, 152.9.

4.3.19. Benzosuber-2-yl chloromethylcarbonate (33)

Synthesized from (S)-2-benzosuberol 30 (62 mg, 0.38 mmol, 1 equiv) according to general procedure B. Purification by flash chromatography (hexane to 20% EtOAc–hexanes) afforded the title compound (90 mg, 92%) as a colorless solid: Rf = 0.42 (20% EtOAc–hexanes); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.57 (m, 1H), 1.98 (m, 2H), 2.24 (m, 1H), 2.80 (t, J = 4.2 Hz, 2H), 3.07 (d, J = 13.5 Hz, 1H), 3.25 (dd, J = 13.8, 10.3 Hz, 1H), 4.76 (t, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H), 5.72 (s, 2H), 7.12 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.17 (m, 3H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 24.3, 35.2, 36.7, 41.0, 72.0, 77.6, 126.5, 127.1, 128.9, 130.4, 135.1, 142.9, 152.5.

4.3.20. (S)-Indan-1-yl iodomethylcarbonate (13a)

The title compound was prepared from 9a (1.6 g, 7.19 mmol, 1.0 equiv) according to general procedure C to afford a yellow oil (1.73 g, 76%): Rf = 0.61 (20% EtOAc–hexanes); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 2.25 (m, 1H), 2.51 (m, 1H), 2.89 (ddd, J = 16.1, 8.5, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 3.15 (m, 1H), 5.71 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 5.75 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 6.15 (dd, J = 6.7, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.24 (m, 1H), 7.28 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.32 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 30.1, 32.1, 72.1, 83.6, 124.9, 125.8, 126.8, 129.6, 139.5, 144.7, 153.3.

4.3.21. (R)-Indan-1-yl iodomethylcarbonate (13b)

This compound was prepared analogously to 13a, but using 9b as the substrate to afford a yellow oil (1.72 g, 75%).

4.3.22. (S)-Tetral-1-yl iodomethylcarbonate (14a)

The title compound was prepared from 10a (1.6 g, 6.7 mmol, 1.0 equiv) according to general procedure C to afford a yellow oil (1.8 g, 85%): Rf = 0.64 (20% EtOAc–hexanes); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.74–1.81 (m, 1H), 1.87– 1.99 (m, 2H), 2.06–2.11 (m, 1H), 2.64–2.74 (m, 1H), 2.77–2.83 (m, 1H), 5.84 (br s, 1H), 5.87– 5.91 (m, 2H), 7.06 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 7.10–7.14 (m, 1H), 7.16–7.20 (m, 1H), 7.28 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 18.4, 28.7, 28.9, 34.1, 75.9, 126.2, 128.7, 129.2, 129.7, 132.9, 137.9, 153.0.

4.3.23. (R)-Tetral-1-yl iodomethylcarbonate (14b)

This compound was prepared analogously to 14a, but using 10b as the substrate to afford a yellow oil (1.5 g, 70%).

4.3.24. (S)-Benzosuber-1-yl iodomethylcarbonate (15a)

The title compound was prepared from 11a (1.4 g, 5.5 mmol, 1.0 equiv) according to procedure C to afford a pale yellow oil (1.8 g, 95%): Rf = 0.53 (20% EtOAc–hexanes); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ1.62–1.77 (m, 2H),1.84–1.92 (m, 1H), 1.94–2.01 (m, 1H), 2.02–2.12 (m, 2H), 2.72–2.79 (m, 1H), 2.97–3.04 (m,1H), 5.86 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 5.95 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 5.99 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 7.14 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 7.17–7.24 (m, 2H), 7.31 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 26.7, 27.3, 32.9, 33.9, 35.4, 81.5, 125.9 (2C), 127.9, 129.7, 138.5, 141.1, 152.8.

4.3.25. (R)-Benzosuber-1-yl iodomethylcarbonate (15b)

This compound was prepared analogously to 15a, but using 11b as the substrate to afford a yellow oil (1.5 g, 93%).

4.3.26. (1S, 1’R/S)-Benzosuber-1-yl iodoethylcarbonate (16a)

Synthesized from 12a (1.57 g, 5.84 mmol, 1.0 equiv) according to procedure C. 1H NMR showed only 30% conversion to the title compound. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.61 (m, 0.5H), 1.69 (m, 1H), 1.73 (m, 0.5H), 1.87 (m, 1H), 1.97 (m, 1.5H), 2.06 (m, 1.5H), 2.24 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 1.5H), 2.27 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 1.5H), 2.75 (m, 1H), 3.00 (m, 1H), 5.84 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 0.5H), 5.86 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 0.5H), 6.76 (q, J = 5.9 Hz, 0.5H), 6.80 (q, J = 5.9 Hz, 0.5H), 7.13 (m, 1H), 7.19 (m, 2H), 7.32 (m, 1H).

4.3.27. Indan-2-yl iodomethylcarbonate (34)

The title compound was prepared from 31 (1.50 g, 6.65 mmol, 1.0 equiv) according to general procedure C to afford a white solid with a yellow hue (1.47 g, 70%): Rf = 0.52 (20% EtOAc–hexanes); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.12 (br s, 1H), 3.15 (br s, 1H), 3.36 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 3.39 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 5.53 (br s, 1H), 5.95 (s, 2H), 7.20–7.22 (m, 2H), 7.24–7.27 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 33.9, 39.4, 80.5, 124.6, 127.0, 139.6, 152.9.

4.3.28. Tetral-2-yl iodomethylcarbonate (35)

The title compound was prepared from 32 (1.14 g, 4.74 mmol, 1.0 equiv) according to general procedure C to afford a colorless solid (1.09 g, 69%): Rf = 0.53 (20% EtOAc–hexanes); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 2.10 (m, 1H), 2.16 (m, 1H), 2.90 (dt, J = 16.8, 7.2 Hz, 1H), 2.98 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 3.02 (dd, J = 16.8, 7.8 Hz, 1H), 3.23 (dd, J = 16.4, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 5.13 (m, 1H), 5.96 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 5.98 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 7.13 (m, 1H), 7.15 (m, 1H), 7.19 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 25.9, 27.3, 34.0, 34.2, 75.0, 125.8, 126.0, 128.3, 129.0, 132.4, 134.7, 152.3.

4.3.29. Benzosuber-2-yl iodomethylcarbonate (36)

The title compound was prepared from 33 (0.55 g, 2.14 mmol, 1.0 equiv) according to general procedure C to afford a colorless solid (0.57 g, 77%): Rf = 0.55 (20% EtOAc–hexanes); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.57 (m, 1H), 1.96 (m, 2H), 2.22 (m, 1H), 2.79 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 2H), 3.05 (d, J = 14.1 Hz, 1H), 3.24 (dd, J = 14.1, 10.0 Hz, 1H), 4.75 (t, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H), 5.94 (s, 2H), 7.10 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.16 (m, 3H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 24.3, 34.0, 35.2, 36.8, 41.0, 77.6, 126.5, 127.1, 128.9, 130.5, 135.1, 142.9, 152.3.

4.3.30. Isopropoxycarbonyloxymethyl (1/R, 5S,6S)-2-{[(2S,4S)-2-(N,N-dimethylcarbamoyl)pyrrolidin-4-yl]thio}-6-[(1R)-1-hydroxyethyl]-1-methylcarbapen-2-em-3-carboxylate (2)

A solution of meropenem (100 mg, 0.26 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and Cs2CO3 (367 mg, 1.04 mmol, 4.0 equiv) in DMF (0.5 mL) was stirred at 0 °C for 10 min. Next, 1-iodoethyl isopropyl carbonate (87 mg, 0.34 mmol, 1.3 equiv) was added dropwise and the reaction mixture was stirred for 30 min at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was subsequently evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure. Purification by flash chromatography (10% MeOH–CH2Cl2 with 1% NH4OH) afforded the title compound (75 mg, 64%) as an off-white foam as a 1:1 mixture of diastereomers. The analytical data is for the mixture: Rf = 0.23 (diastereomer 1) and 0.25 (diastereomer 2) (10% MeOH–CH2Cl2 with 1% NH4OH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.26 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 1.28 (app t, J = 5.9 Hz, 3H), 1.29 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 3H), 1.32 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 3H), 1.55 (app dd, J = 13.5, 5.3 Hz, 3H), 1.60 (m, 1H), 2.44 (m, 2H), 2.60 (dt, J = 13.6, 8.1 Hz, 1H), 2.95 (s, 3H), 2.99 (s, 3H), 3.06 (td, J = 11.3, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 3.24 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 3.24 (m, 1H), 3.42 (m, 1H), 3.74 (m, 1H), 3.99 (m, 1H), 4.23 (m, 2H), 4.88 (hept, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H), 6.83 (q, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 6.84 (q, J = 5.4 Hz); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 17.3, 17.4, 19.9, 20.0, 21.9 (2C), 21.97, 22.00, 22.04, 22.1, 36.1, 36.5, 36.6, 37.0, 43.9, 44.0, 44.56, 44.63, 56.07, 56.12, 56.59, 56.65, 58.70, 58.72, 60.41, 60.45, 66.07, 66.12, 73.28, 73.31, 91.9, 92.3, 124.9, 125.0, 152.3, 152.4, 152.9, 153.0, 159.2, 159.3, 172.0, 172.1, 173.1, 173.2; HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C23H36N3O8S [M + H]+ 514.2218, found 514.2219 (error 0.2 ppm).

4.3.31. (S)-Indan-1-yloxycarbonyloxymethyl (1R,5S,6S)-2-{[(2S,4S)-2-(N,N-dimethylcarbamoyl)pyrrolidin-4-yl]thio}-6-[(1/R)-1-hydroxyethyl]-1-methylcarbapen-2-em-3-carboxylate (17)

Synthesized according to general procedure D employing 13a to afford the title compound (112 mg, 75%) as a white solid: Rf = 0.19 (10% MeOH–CH2Cl2 with 1% NH4OH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.23 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 1.29 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 3H), 1.59 (m, 1H), 2.20 (m, 1H), 2.48 (td, J = 15.0, 7.2 Hz, 1H), 2.71 (dt, J = 13.2, 7.8 Hz, 1H), 2.87 (m, 1H), 2.92 (s, 3H), 2.97 (s, 3H), 3.10 (m, 2H), 3.24 (dd, J = 6.6, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 3.49 (dd, J = 11.4, 5.6 Hz, 1H), 3.57 (m, 1H), 3.83 (m, 1H), 4.19 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 4.27 (t, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 4.35 (d, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H), 5.79 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 5.90 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 6.11 (dd, J = 6.5, 2.9 Hz, 1H), 7.21 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (m, 2H), 7.47 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 17.5, 22.0, 30.6, 32.5, 36.0, 36.2, 37.1, 43.2, 44.6, 55.5, 56.9, 58.5, 60.5, 66.1, 82.7, 83.7, 124.6, 125.3, 126.3, 127.2, 129.9, 140.3, 145.3, 153.2, 154.2, 159.9, 171.1, 173.5; HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C28H36N3O8S [M + H]+ 574.2218, found 574.2224 (error 1.0 ppm).

4.3.32. (R)-Indan-1-yloxycarbonyloxymethyl (1/R, 5S,6S)-2-{[(2S,4S)-2-(N,N-dimethylcarbamoyl)pyrrolidin-4-yl]thio}-6-[(1/R)-1-hydroxyethyl]-1-methylcarbapen-2-em-3-carboxylate (20)

Synthesized according to general procedure D employing 13b to afford the title compound (108 mg, 72%) as a white foam: Rf = 0.24 (10% MeOH–CH2Cl2 with 1% NH4OH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.22 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 1.29 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 3H), 1.59 (dt, J = 13.8, 7.2 Hz, 1H), 2.21 (m, 1H), 2.48 (m, 1H), 2.71 (dt, J = 13.2, 8.1 Hz, 1H), 2.85 (m,1H), 2.91 (s, 3H), 2.97 (s, 3H), 3.09 (m, 2H), 3.23 (dd, J = 6.0, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 3.46 (dd, J = 11.4, 5.6 Hz, 1H), 3.56 (m, 1H), 3.82 (m, 1H), 3.98 (m, 2H), 4.19 (m, 1H), 4.25 (t, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 4.34 (dd, J = 9.1, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 5.82 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 5.88 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 6.10 (dd, J = 6.5, 2.9 Hz, 1H), 7.21 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 7.28 (m, 2H), 7.46 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 17.4, 22.0, 30.6, 32.6, 36.1, 36.2, 37.1, 43.3, 44.6, 55.6, 56.9, 58.5, 60.5, 66.1, 82.7, 83.7, 124.6, 125.4, 126.2, 127.2, 129.9, 140.3, 145.4, 153.3, 154.2, 159.9, 171.2, 173.5; HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C28H36N3O8S [M + H]+ 574.2218, found 574.2221 (error 0.5 ppm).

4.3.33. (S)-Tetral-1-yloxycarbonyloxymethyl (1R,5S,6S)-2-{[(2S,4S)-2-(N,N-dimethylcarbamoyl)pyrrolidin-4-yl]thio}-6-[(1R)-1-hydroxyethyl]-1-methylcarbapen-2-em-3-carboxylate (18)

Synthesized according to general procedure D employing 14a to afford the title compound (87 mg, 57%) as a white solid: Rf = 0.35 (10% MeOH–CH2Cl2 with 1% NH4OH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.24 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 3H), 1.27 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 3H), 1.54 (dt, J = 13.6, 7.0 Hz, 1H), 1.80 (m, 1H), 1.93 (m, 1H), 2.01 (td, J = 11.4, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 2.13 (m, 1H), 2.58 (dt, J = 13.8, 8.4 Hz, 1H), 2.72 (ddd, J = 16.8, 9.0, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 2.84 (m, 1H), 2.92 (s, 3H), 2.96 (s, 3H), 3.05 (dd, J = 11.7, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 3.06 (m, 2H), 3.20 (dd, J = 12.0, 5.6 Hz, 1H),3.23 (dd, J = 6.6, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 3.42 (m, 1H), 3.73 (m, 1H), 3.93 (t, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 4.19 (m, 1H),4.24 (d, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H), 5.80 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 5.85 (t, J = 4.2 Hz, 1H), 5.92 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 7.11 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.17 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.37 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 17.3, 19.0, 22.1, 29.2, 29.3, 36.1, 36.6, 36.9, 44.2, 44.6, 56.1, 56.6, 58.7, 60.4, 65.8, 75.8, 82.6, 124.4, 126.6, 129.0, 129.5, 130.2, 133.8, 138.6, 153.7, 154.2, 159.7, 172.2, 173.5; HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C29H38N3O8S [M + H]+ 588.2374, found 588.2379 (error 0.9 ppm).

4.3.34. (R)-Tetral-1-yloxycarbonyloxymethyl (1R, 5S,6S)-2-{[(2S,4S)-2-(N,N-dimethylcarbamoyl)pyrrolidin-4-yl]thio}-6-[(1R)-1-hydroxyethyl]-1-methylcarbapen-2-em-3-carboxylate (21)

Synthesized according to general procedure D employing 14b to afford the title compound (124 mg, 82%) as a white solid foam: Rf = 0.29 (10% MeOH–CH2Cl2 with 1% NH4OH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.23 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 1.28 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 3H), 1.55 (dt, J = 13.6, 7.0 Hz, 1H), 1.80 (m, 1H), 1.93 (m, 1H), 2.00 (m, 1H), 2.13 (m, 1H), 2.63 (dt, J = 13.8, 8.4 Hz, 1H), 2.72 (ddd, J = 16.8, 9.0, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 2.84 (m, 1H), 2.92 (s, 3H), 2.96 (s, 3H), 3.05 (dd, J = 12.0, 3.8 Hz, 1H), 3.07 (m, 2H), 3.22 (dd, J = 6.6, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 3.28 (dd, J = 11.7, 5.9 Hz, 1H), 3.46 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 3.76 (m, 1H), 4.03 (t, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 4.18 (m, 1H), 4.27 (dd, J = 9.4, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 5.81 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 5.85 (m, 1H), 5.91 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 7.11 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.16 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.35 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 17.4, 19.0, 22.0, 29.2, 29.3, 36.1, 36.4, 36.9, 43.9, 44.6, 56.0, 56.7, 58.6, 60.5, 66.0, 75.9, 82.7, 124.5, 126.5, 129.0, 129.6, 130.2, 133.8, 138.7, 153.6, 154.1, 159.8, 171.9, 173.5; HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C29H38N3O8S [M + H]+ 588.2374, found 588.2378 (error 0.7 ppm).

4.3.35. (S)-Benzosuber-1-yloxycarbonyloxymethyl (1R, 5S,6S)-2-{[(2S,4S)-2-(N,N-dimethylcarbamoyl)pyrrolidin-4-yl]thio}-6-[(1R)-1-hydroxyethyl]-1-methylcarbapen-2-em-3-carboxylate (19)

Synthesized according to general procedure D employing 15a to afford the title compound (131 mg, 84%) as a white foam: Rf = 0.32 (10% MeOH–CH2Cl2 with 1% NH4OH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.25 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 1.30 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 3H), 1.58 (dt, J = 13.6, 7.0 Hz, 2H), 1.68 (m, 1H), 1.83 (m, 1H), 1.96 (m, 1H), 2.01 (m, 2H), 2.62 (m, 1H), 2.73 (dd, J = 13.8, 9.6 Hz, 1H), 2.94 (s, 3H), 2.95 (m, 1H), 2.98 (s, 3H), 3.04 (dd, J = 11.7, 4.1 Hz, 1H), 3.20 (m, 2H), 3.23 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 3.30 (dd, J = 11.4, 5.6 Hz, 1H), 3.47 (m, 1H),3.75 (m, 1H), 4.06 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 4.21 (m, 1H), 4.28 (d, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H), 5.80 (m, 2H), 5.89 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 7.11 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.16 (m, 2H), 7.29 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 17.4, 22.0, 27.5, 28.1, 33.7, 36.0, 36.1, 36.3, 37.0, 43.7, 44.6, 55.8, 56.8, 58.5, 60.4, 65.9, 81.6, 82.8, 124.4, 126.5, 128.4, 130.3, 139.7, 141.8, 153.6, 153.7, 159.8, 171.7, 173.6 (missing 1 aryl C); HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C30H40N3O8S [M + H]+ 602.2531, found 602.2537 (error 1.0 ppm).

4.3.36. (R)-Benzosuber-1-yloxycarbonyloxymethyl (1R,5S, 6S)-2-{[(2S,4S)-2-(N,N-dimethylcarbamoyl)pyrrolidin-4-yl]thio}-6-[(1R)-1-hydroxyethyl]-1-methylcarbapen-2-em-3-carboxylate (22)

Synthesized according to general procedure D employing 15b to afford the title compound (123 mg, 79%) as a white solid foam: Rf = 0.24 (10% MeOH–CH2Cl2 with 1% NH4OH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.23 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 1.27 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 3H), 1.55 (m, 2H), 1.66 (m, 1H), 1.83 (m, 1H), 1.93 (m, 1H), 2.00 (m, 2H), 2.66 (m, 1H), 2.72 (dd, J = 13.8, 9.6 Hz, 1H), 2.92 (s, 3H), 2.97 (s, 3H), 3.05 (dd, J = 12.0, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 3.22 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 3.35 (dd, J = 11.4, 5.6 Hz, 1H), 3.52 (m, 1H), 3.78 (m, 1H), 3.89 (m, 3H), 4.12 (t, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 4.17 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 4.30 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 5.80 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 5.85 (s, 2H), 7.10 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 7.15 (m, 2H), 7.28 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 17.4, 22.0, 27.4, 28.1, 33.6, 36.0, 36.1, 36.3, 37.0, 43.6, 44.6, 55.8, 56.8, 58.5, 60.4, 66.0, 81.7, 82.6, 124.4, 126.5, 128.4, 130.3, 139.6, 142.0, 153.6, 153.7, 159.8, 171.7, 173.6 (missing 1 aryl C); HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C30H40N3O8S [M + H]+ 602.2531, found 602.2529 (error 0.3 ppm).

4.3.37. (1S,1′S/R)-Benzosuber-1-yloxycarbonyloxyethyl (1R,5S,6S)-2-{[(2S,4S)-2-(N,N-dimethylcarbamoyl)pyrrolidin-4-yl]thio}-6-[(1R)-1-hydroxyethyl]-1-methylcarbapen-2-em-3-carboxylate (23a)

Synthesized according to general procedure D employing 16a to afford the title compound (69 mg, 43%) as a 1:1 mixture of 2 diastereomers: Rf = 0.29 and 0.32 (10% MeOH–CH2Cl2 with 1% NH4OH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.22 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1.5H), 1.25 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1.5H), 12.7 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1.5H), 1.29 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1.5H), 1.53 (m, 1H), 1.54 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 1.5H), 1.60 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 1.5H), 1.70 (m, 1H), 1.83 (m, 1H), 1.97 (m, 2H), 2.01 (m, 1H), 2.56 (m, 1H), 2.73 (m, 2H), 2.79 (m, 2H), 2.93 (d, J = 4.1 Hz, 3H), 2.95 (m, 0.5H), 2.96 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 3H), 3.03 (td, J = 11.4, 4.2 Hz, 1H), 3.06 (m, 0.5H), 3.17 (dt, J = 6.0, 5.4 Hz, 1H), 3.21 (ddd, J = 15.6, 6.0, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 3.38 (m, 1H), 3.72 (m, 1H), 3.91 (m, 1H), 4.18 (m, 1H), 4.21 (td, J = 9.6, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 5.78 (m, 1H), 6.84 (m, 1H), 7.10 (m, 1H), 7.16 (m, 2H), 7.28 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 17.3, 19.9, 20.0, 22.1, 27.7, 28.17, 28.23, 33.8, 33.9, 36.06, 36.11, 36.7, 36.8, 36.9, 44.27, 44.29, 44.6, 44.7, 56.3, 56.4, 56.51, 56.53, 58.9, 60.3, 60.4, 66.1, 81.2, 81.3, 92.1, 92.5, 124.7, 124.9, 126.5, 126.7, 128.3, 128.4, 130.3, 152.5, 152.6, 152.8, 153.0, 159.1, 159.2, 172.2, 172.3, 173.0, 173.1; HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C31H42N3O8S [M + H]+ 616.2687, found 616.2691 (error 0.7 ppm).

4.3.38. (S)-Benzosuber-1-yloxycarbonyloxymethyl (1R,5S,6S)-2-{[(2S,4S)-1-acetyl-2-(N,N-dimethylcarbamoyl)pyrrolidin-4-yl]thio}-6-[(1R)-1-hydroxyethyl]-1-methylcarbapen-2-em-3-carboxylate (24a)

A solution of meropenem (100 mg, 1.0 equiv) and Cs2CO3 (367 mg, 1.04 mmol 4.0 equiv) in DMF (1.3 mL) was stirred at 0 °C for 10 min. Next, acetic anhydride (30 mg, 0.29 mmol, 1.1 equiv) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred for 1 h until starting material was consumed by TLC. Subsequently, (S)-1-benzosuberol iodomethylcarbonate 15a (200 mg, 1.73 mmol, 1.57 equiv) in DMF (1.0 mL) was added dropwise to the reaction mixture. After 1 h the reaction was concentrated in vacuo and the residue was purified by flash chromatography (10% MeOH–CH2Cl2 with 1% NH4OH) to afford the title compound (104 mg, 62%): Rf = 0.25 (10% MeOH–CH2Cl2 with 1% NH4OH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD2Cl2) δ 1.25 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 1.28 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 3H), 1.60 (m, 1H), 1.68 (m, 1H), 1.80 (s, 1H), 1.84 (m, 2H), 1.96 (m, 1H), 2.01 (s, 3H), 2.01 (m, 1H), 2.67 (dt, J = 14.4, 7.8 Hz, 1H), 2.72 (dd, J = 13.5, 10.6 Hz, 1H), 2.90 (s, 3H), 2.96 (t, J = 11.7 Hz, 1H), 3.07 (s, 3H), 3.20 (m, 1H), 3.24 (dd, J = 6.5, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 3.42 (m, 1H), 3.51 (t, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 3.70 (m, 1H), 3.98 (dd, J = 10.0, 7.6 Hz, 1H), 4.17 (m, 1H), 4.25 (dd, J = 9.0, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.78 (t, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 5.79 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 5.82 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 5.89 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 7.11 (m, 1H), 7.16 (m, 2H), 7.28 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 17.5, 22.1, 22.7, 27.5, 28.1, 33.7, 35.5, 36.0, 36.3, 37.4, 41.6, 44.6, 56.1, 56.6, 58.1, 60.7, 66.1, 81.7, 82.8, 125.2, 126.6, 128.4, 130.3, 139.7, 142.0, 151.4, 153.6, 159.7, 168.9, 171.3, 173.6 (missing 1 aryl C); HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C32H42N3O9S [M + H]+ 644.2636, found 644.2633 (error 0.5 ppm).

4.3.39. Indan-2-yloxycarbonyloxymethyl (1R,5S,6S)-2-{[(2S,4S)-2-(N,N-dimethylcarbamoyl)pyrrolidin-4-yl]thio}-6-[(1R)-1-hydroxyethyl]-1-methylcarbapen-2-em-3-carboxylate (37)

Synthesized according to general procedure D employing 34 to afford the title compound (107 mg, 71%) as an off-white foam: Rf = 0.26 (10% MeOH–CH2Cl2 with 1% NH4OH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD2Cl2) δ 1.25 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 3H), 1.29 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 3H), 1.55 (dt, J = 13.5, 6.7 Hz, 1H), 2.58 (dt, J = 14.4, 7.2 Hz, 1H), 2.94 (s, 3H), 2.96 (m, 1H), 2.97 (s, 3H), 3.06 (m, 2H), 3.13 (m, 2H), 3.19 (dd, J = 11.7, 5.3 Hz, 1H), 3.24 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 3.33 (m, 2H), 3.41 (m, 1H), 3.74 (m, 1H), 3.92 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 4.20 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H), 4.24 (d, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H), 5.47 (m, 1H), 5.79 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 5.88 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 7.17 (m, 2H), 7.24 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD2Cl2) δ 17.3, 22.1, 36.1, 36.7, 36.9, 39.8, 44.3, 44.7, 56.3, 56.6, 58.8, 60.4, 65.9, 80.7, 82.5, 124.4, 125.1, 127.3, 140.5, 153.8, 154.1, 159.7, 172.2, 173.4; HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C28H36N3O8S [M + H]+ 574.2218, found 574.2214 (error 0.7 ppm).

4.3.40. (2S/R)-Tetral-2-yloxycarbonyloxymethyl (1R,5S,6S)-2-{[(2S,4S)-2-(N, N-dimethylcarbamoyl)pyrrolidin-4-yl]thio}-6-[(1R)-1-hydroxyethyl]-1-methylcarbapen-2-em-3-carboxylate (38)

Synthesized according to general procedure D employing 35 to afford the title compound (127 mg, 82%) as an off-white foam as a mixture of diastereomers (epimeric at the C-2 indanyl carbon): Rf = 0.25 and 0.30 (10% MeOH–CH2Cl2 with 1% NH4OH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD2Cl2) δ 1.25 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 1.28 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 3H), 1.55 (dt, J = 13.5, 6.7 Hz, 1H), 2.03 (m, 1H), 2.10 (m, 1H), 2.61 (dt, J = 13.8, 8.1 Hz, 1H), 2.84 (m, 1H), 2.93 (s, 3H), 2.95 (m, 2H), 2.97 (s, 3H), 3.06 (dd, J = 11.7, 2.9 Hz, 1H), 3.19 (m, 3H), 3.44 (m, 1H), 3.54 (m, 2H), 3.75 (m, 1H), 3.95 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 4.18 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 4.25 (d, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H), 5.13 (m, 1H), 5.80 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 5.89 (t, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 7.10 (m, 4H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD2Cl2) δ 17.3, 22.1, 26.6, 28.0, 34.7, 36.0, 36.6, 36.8, 44.1, 44.6, 54.4, 56.1, 56.5, 58.6, 60.4, 65.7, 75.3, 82.5, 124.3, 126.3, 126.5, 129.0, 129.7, 133.6, 135.8, 153.8, 159.7, 172.1, 173.6; HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C29H38N3O8S [M + H]+ 588.2374, found 588.2369 (error 0.9 ppm).

4.3.41. (2S/R)-Benzosuber-2-yloxycarbonyloxymethyl (1R,5S,6S)-2-{[(2S,4S)-2-(N, N-dimethylcarbamoyl)pyrrolidin-4-yl]thio}-6-[(1R)-1-hydroxyethyl]-1-methylcarbapen-2-em-3-carboxylate (39)

Synthesized according to general procedure D employing 36 to afford the title compound (110 mg, 65%) as an off-white foam as a mixture of diastereomers (epimeric at the C-2 benzosuberyl carbon): Rf = 0.25 and 0.27 (10% MeOH–CH2Cl2 with NH4OH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD2Cl2) δ 1.26 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 1.28 (app dd, J = 6.2, 2.6 Hz, 3H), 1.54 (m, 2H), 1.93 (m, 2H), 2.18 (m, 1H), 2.59 (dt, J = 13.5, 8.2 Hz, 1H), 2.77 (m, 2H), 2.94 (s, 3H), 2.97 (s, 3H), 3.06 (m, 4H), 3.19 (m, 2H), 3.24 (dd, J = 6.5, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 3.41 (dt, J = 16.2, 7.5 Hz, 1H), 3.74 (m, 1H), 3.92 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 4.20 (pent, J = 6.5, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.24 (dd, J = 9.1, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 4.68 (t, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 5.78 (app dd, J = 7.0, 5.9 Hz, 1H), 5.87 (app dd, J = 8.2, 5.9 Hz, 1H), 7.13 (m, 4H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD2Cl2) δ 17.4, 22.1, 25.1, 35.7, 36.1, 36.7, 36.9, 37.3, 41.6, 44.2, 44.7, 56.3, 56.7, 58.8, 60.4, 66.0, 77.7, 82.5, 124.5, 126.9, 127.4, 129.4, 130.9, 136.3, 143.8, 153.6, 153.7, 159.8, 172.2, 173.4; HRMS (ESI+) calcd for C30H40N3O8S [M + H]+ 602.2531, found 602.2530 (error 0.2 ppm).

4.4. High Performance Liquid Chromatography

Solvents and reagents for liquid chromatography included HPLC grade methanol, isopropanol, and n-heptanes, (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), ammonium acetate (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), and acetic acid (Pharmco, Brookfield, CT).

4.4.1. Reversed-phase HPLC

The HPLC system was composed of an Agilent 1100 Liquid Chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), a Phenomenex Gemini-NX 150× 4.6 mm, 5 µm reversed-phase column (Phenomenex, Torrence, CA), and a Shimadzu UV/Vis detector (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) set at 300 nm. Ammonium acetate (25 mM, pH 4.8) and methanol were the aqueous (A) and organic (B) components of the mobile phase. Meropenem, and prodrugs eluted at 4.3, 5.7, and 7.5–8.5 min, respectively, with the following step gradient elution: 15% B over 5.0 min, 95% B from 5.0–8.5 min, and re-equilibration at 15% B from 8.5–10.0 min prior to the next injection. The detection wavelength was set at 300 nm and the flow rate was 1.0 mL/min.

4.4.2. Normal-phase Chiral HPLC

Chromatography was performed on a Shimadzu chromatograph system consisting of a SIL-10A autosampler, LC-10AD and LC-10AT binary pump system (Shimadzu, Columbia, MD) and a Spectra Focus UV/Vis optical scanning detector (Spectra-Physics, Santa Clara, CA). Chiral separations were achieved using a Chiralcel OJ 250× 4.6 mm, 10 µm column (Daicel Chemical Industries, Tokyo, Japan) with n-heptane and isopropanol as mobile phase A and B, respectively. Method 1: 5% B isocratic elution at 1.0 mL/min during which (S)-1-indanol and (R)-1-indanol eluted at 8.46 and 9.19 min, respectively with the detection wavelength set at 254 nm. Method 2: 15% B isocratic elution at 1.0 mL/min during which (S)-1-tetralol and (R)-1-tetralol eluted at 5.16 and 5.88 min, respectively, with the detection wavelength set at 254 nm. Method 3: 25% B isocratic elution at 1.0 mL/min during which (S)-1-benzosuberol, (R)-1-benzosuberol eluted at 4.53 and 5.15 min, respectively and the detection wavelength set at 254 nm.

4.5. Prodrug stability

Reagents for prodrug stability included hydrochloric acid (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), sodium chloride, 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES),tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Meropenem and prodrugs (2, 17–22, 23a, 24a, 37–39) (100 µM) were incubated at 37 °C in simulated gastric fluid (pH 1.2)35, 100 mM MES pH 6.0, and 100 mM Tris, pH 7.4. In triplicate, samples (980 µL) were pre-incubated for 2 min at 37 °C followed by the addition of 20 µL of a 5.0 mM DMSO stock solution of meropenem or prodrug. The final incubation volume was 1.0 mL and aliquots (100 (µL) were removed from the incubation solution at 0, 5, 10, 15, 30, 45, 60, and 120 min, and immediately injected (85 µL) onto the HPLC. Stability was determined by calculating the half-life of the parent compound or the percentage of prodrug remaining after the final incubation time.

4.6. Plasma stability

The plasma stability of selected prodrugs was investigated with Dunkin Hartley female pooled guinea pig plasma (BioChemed, Winchester, VA). In triplicate, plasma (1.0 mL) was pre-incubated for 2 min at 37 °C followed by the addition of 20 µL of a 5.0 mM stock solution of prodrug. Aliquots (100 µL) were withdrawn at 0, 2.5, 5, 10, 15, and 30 min and immediately quenched with an equal volume of acetonitrile to precipitate the proteins. The samples were filtered through nylon 0.2 µM spin filters (Chrom Tech, Inc., Apple Valley, Minnesota) and 100 µL of the filtrate was injected onto the HPLC. The stability of the prodrugs was determined by calculating the half-lives of the parent compounds.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by the National Institute of Health grant R21AI090147 to R.P.R. We thank Kathryn Nelson for carefully proofreading this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.World Health Organization, WHO Report 2012. Global Tuberculosis Control. http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/

- 2.Barry CE, 3rd, Boshoff HI, Dartois V, Dick T, Ehrt S, Flynn J, Schnappinger D, Wilkinson RJ, Young D. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:845. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Guidelines for treatment of tuberculosis. (fourth edition) http://www.who.int/tb/publications/2010/9789241547833/en/

- 4.Villemagne B, Crauste C, Flipo M, Baulard AR, Deprez B, Willand N. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012;51:1. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marriner GA, Nayyar A, Uh E, Wong SY, Mukherjee T, Via LE, Carroll M, Edwards RL, Gruber TD, Choi I, Lee J, Arora K, England KD, Boshoff HI, Barry CE., 3rd Top. Med. Chem. 2011;7:47. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abraham EP, Chain E, Fletcher CM, Gardner AD, Heatley NG, Jennings MA, Florey HW. Lancet. 1941;238:177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iland CN, Baines S. J. Pathol. Bacteriol. 1949;61:329. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jarlier V, Gutmann L, Nikaido H. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1937. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.9.1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chambers HF, Moreau D, Yajko D, Miick C, Wagner C, Hackbarth C, Kocagoz S, Rosenberg E, Hadley WK, Nikaido H. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2620. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.12.2620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flores AR, Parsons LM, Pavelka MS., Jr. Microbiology. 2005;151:521. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27629-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang F, Cassidy C, Sacchettini JC. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006;50:2762. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00320-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hugonnet JE, Blanchard JS. Biochemistry. 2007;46:11998. doi: 10.1021/bi701506h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hugonnet JE, Tremblay LW, Boshoff HI, Barry CE, 3rd, Blanchard JS. Science. 2009;323:1215. doi: 10.1126/science.1167498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.England K, Boshoff HI, Arora K, Weiner D, Dayao E, Schimel D, Via LE, Barry CE., 3rd Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012;56:3384. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05690-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dauby N, Muylle I, Mouchet F, Sergysels R, Payen MC. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2011;30:812. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3182154b05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Payen MC, De Wit S, Martin C, Sergysels R, Muylle I, Van Laethem Y, Clumeck N. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung. Dis. 2012;16:558. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mouton JW, van den Anker JN. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1995;28:275. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199528040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanaka S, Matsui H, Kasai M, Kunishiro K, Kakeya N, Shirahase H. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 2011;64:233. doi: 10.1038/ja.2010.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takeuchi Y, Sunagawa M, Isobe Y, Hamazume Y, Noguchi T. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 1995;43:689. doi: 10.1248/cpb.43.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stella VJ. In: Prodrugs Biotechnology: Pharmaceutical Aspects. Stella VJ, Borchardt RT, Hagerman MJ, Oliyai R, Maag H, Tilley JW, editors. Vol. V. New York: Springer; 2007. p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sinkula AA. In: Pro-drugs as Novel Drug Delivery Systems. Higuchi T, Stella V, editors. Vol. 14. Washington D.C.: American Chemical Society; 1975. p. 116. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nielsen NM, Bundgaard H. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1988;40:506. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1988.tb05287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumagai T, Tamai S, Abe T, Hikida M. Curr. Med. Chem. - Anti-Infective Agents. 2002;1:1. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kijima K, Morita J, Suzuki K, Aoki M, Kato K, Hayashi H, Shibasaki S, Kurosawa T. Jpn. J. Antibiot. 2009;62:214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arrigoni-Martelli E, Caso V. Drugs. Exp. Clin. Res. 2001;27:27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brass EP. In: Prodrugs Biotechnology: Pharmaceutical Aspects. Stella VJ, Borchardt RT, Hagerman MJ, Oliyai R, Maag H, Tilley JW, editors. Vol. V. New York: Springer; 2007. p. 425. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bichlmaier I, Siiskonen A, Kurkela M, Finel M, Yli-Kauhaluoma J. Biol. Chem. 2006;387:407. doi: 10.1515/BC.2006.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bandgar BP, Sarangdhar RJ, Khan F, Mookkan J, Shetty P, Singh G. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:5915. doi: 10.1021/jm200704f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phan DH, Kou KG, Dong VM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:16354. doi: 10.1021/ja107738a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li L, Cai P, Guo Q, Xue S. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:3516. doi: 10.1021/jo800231s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corey EJ, Helal CJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998;37:1986. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980817)37:15<1986::AID-ANIE1986>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saito T, Sawazaki R, Kaori Ujiie, Oda M, Saitoh H. Pharmacology & Pharmacy. 2012;3:201. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stoeckel K, Hofheinz W, Laneury JP, Duchene P, Shedlofsky S, Blouin RA. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2602. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.10.2602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kakumanu VK, Arora V, Bansal AK. Eur. J. Pharmaceut. Biopharmaceut. 2006;64:255. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.US Pharmacopeia Test Solution for Simulated Gastric Fluid. http://www.pharmacopeia.cn/v29240/usp29nf24s0-_risls126.html.