Abstract

OBJECTIVE

We sought to test the hypothesis that turmeric-derived curcuminoids limit reperfusion brain injury in an experimental model of stroke via blockade of early microvascular inflammation during reperfusion.

METHODS

Male Sprague Dawley rats subjected to middle cerebral artery occlusion and reperfusion (MCAO/R) were treated with turmeric-derived curcuminoids (vs. vehicle) 1 hour prior to reperfusion (300 mg/kg ip). Neutrophil adhesion to the cerebral microcirculation and measures of neutrophil and endothelial activation were assayed during early reperfusion (0–4 hours); cerebral infarct size, edema and neurological function were assessed at 24 h. Curcuminoid effects on TNFα−stimulated human brain microvascular endothelial cell (HBMVEC) were assessed.

RESULTS

Early during reperfusion following MCAO, curcuminoid treatment decreased neutrophil rolling and adhesion to the cerebrovascular endothelium by 76% and 67% and prevented >50% of the fall in shear rate. The increased number and activation state (CD11b and ROS) of neutrophils were unchanged by curcuminoid treatment, while increased cerebral expression of TNFα and ICAM-1, a marker of endothelial activation, were blocked by >30%. Curcuminoids inhibited NF-κB activation and subsequent ICAM-1 gene expression in HBMVEC.

CONCLUSION

Turmeric derived curcuminoids limit reperfusion injury in stroke by preventing neutrophil adhesion to the cerebrovascular microcirculation and improving shear rate by targeting the endothelium.

Keywords: ischemia, reperfusion, stroke, curcuminoids, neutrophil, endothelium

INTRODUCTION

Turmeric (Curcuma longa L) has been used in Ayurvedic medicine for millennia as an anti-inflammatory botanical (12). More recently, modern scientific research has focused on curcumin, one of the 3 major polyphenolic curcuminoids found in dried turmeric rhizomes, as an important source of turmeric’s anti-inflammatory properties (9). Included in this body of work are numerous reports of a brain protective effect of curcumin in experimental models of ischemic stroke; when curcumin is administered prior to reperfusion in rats subjected to transient occlusion of the middle cerebral artery (middle cerebral artery occlusion and reperfusion, MCAO/R) and brain injury is assessed 24 h later, infarction size, brain edema and various measures of oxidative injury are reduced (7,28,36,38,43,47). The precise mechanism and cellular or molecular targets of curcumin’s protective effect in experimental stroke, however, have not been elucidated.

Adhesion of activated neutrophils to the injured cerebrovasculature is an early (occurring within minutes) and important source of reperfusion injury in stroke, due in part to the oxidative damage caused by the accumulation and infiltration of reactive oxygen species (ROS)-producing neutrophils into the damaged brain parenchyma (4,15,29,31,32,34,42). We therefore hypothesized that the previously described cerebroprotective effects of curcumin in experimental stroke could be due in part to early inhibition of neutrophil-mediated injury at the time of reperfusion. In order to test this hypothesis, cellular effects of curcuminoids on both sides of the neutrophil/endothelial interface were examined in vivo after MCAO/R in rats to identify possible cellular targets during early reperfusion. As a translational step, evidence of curcuminoid effects on relevant molecular targets in human vascular endothelial cells in vitro was also obtained both in terminally differentiated human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVEC) and in human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBMVEC). Experiments were conducted using a naturally-occurring, clinically relevant curcuminoid mixture that is analogous in chemical composition to over the counter turmeric dietary supplements (11).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Botanical Agent

A commercial curcuminoid product (Curcumin C3 Complex), previously used in non-stroke clinical studies in humans (6,18,19,35,40) was purchased from Sabinsa Corporation (Payson, UT, USA), a wholesale supplier of turmeric for the nutraceutical (dietary supplement) industry. Extract curcuminoid content was confirmed using previously described HPLC methodology (11); the extract was composed of 97% curcuminoids by weight (70% curcumin, 21% demethoxycurcumin and 6% bis-demethoxycurcumin). Stability of curcuminoid content was confirmed by repeat HPLC analysis of the curcuminoid product, which was stored at room temperature, for the duration of the studies. For administration to rats, curcuminoids were dissolved in DMSO at a concentration of 300 mg/ml and administered ip in a single 300mg/kg dose (vs. 300 µl vehicle alone [DMSO]) 1 h prior to reperfusion. This treatment replicates the same dose and mode of administration utilized by Thiyagarajan et al in the first published report documenting cerebroprotection by curcumin in MCAO/R (38).

Animals

All animal procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Arizona Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male Sprague Dawley rats 275–350g (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA) were housed under controlled conditions with 12 hour light/dark cycles and 22–24°C temperature. All rats were placed in standard cages (2 per cage) and were fed a standard rodent diet ad libitum. In addition, immediately after the induction of anesthesia in rats undergoing MCAO/R, non-fasting baseline blood samples were obtained via jugular venipuncture using a 23 gauge needle and syringe containing sodium citrate for total white blood cell (WBC) counts (thousands/mm3) (Beckman Coulter AcT5diff, Brea, CA, SUA) and manual determination of differential WBC counts (%). Total neutrophil count was calculated as (total WBC count × % neutrophils)/100 (thousands/mm3).

Middle cerebral artery occlusion and reperfusion

Middle cerebral artery occlusion and reperfusion (MCAO/R) was surgically induced using the intraluminal filament method as previously described in detail by Ritter et al (29,30,32,33). Briefly, animals were anesthetized and a laser doppler flow meter probe (Perimed, North Royalton, OH, USA) was affixed to the skull over the middle cerebral artery territory to measure cerebral blood flow. A 4-0 nylon filament was advanced to the middle cerebral artery. The animal was included in the study if blood flow decreased ≥75% after filament placement. After occlusion was verified, the filament was secured, the neck incision was closed and the animal was allowed to recover. After 2 or 4 hours of ischemia, the neck incision was reopened and the intraluminal filament was withdrawn to initiate reperfusion.

Histologic assessment of brain injury

Cerebral infarction volume and edema were determined in MCAO/R animals (N = 7 animals/group) as previously described by us (32,33). After 4 hours of ischemia and twenty four hours of reperfusion, whole brains were sectioned into seven 2-mm coronal slices and stained with 2% triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC). Infarction volume, corrected for edema, was calculated as the difference between the volume of the contralateral hemisphere and the non-infarcted volume of the ipsilateral hemisphere, expressed as a percent of the contralateral hemisphere (32,33). Edema (%) was calculated as: [(ipsilateral hemisphere volume) – (contralateral hemisphere volume) / (contralateral hemisphere volume)] × 100 (32,33).

Neurologic evaluation

In the same animals undergoing MCAO/R for assessment of infarction volume, a neurologic evaluation was performed after three hours of ischemia (immediately before treatment) and after twenty-four hours of reperfusion. Animals were scored in four categories: level of consciousness, spontaneous circling, front limb symmetry and front limb paresis. Each category was scored from 0–3 (the greater the score, the more severe the impairment). The scores in each category were totaled to yield a total neurologic score. A total score of 6–8 indicates a moderate impairment and a score of 9–10 or greater indicates a severe impairment (32,33). If, after three hours of ischemia, an animal had a total neurologic score of less than 6 or greater than 10, it was not included in the study.

Direct observation of the cerebral microcirculation

Animals underwent the MCAO/R procedure; two hours of ischemia was followed by an hour of direct observation of the cerebral microcirculation during reperfusion (N = 4 animals/group) using intravital fluorescence microscopy as previously described by our laboratory (31–33). Briefly, anesthetized animals were intubated and mechanically ventilated. Catheters were placed in the tail artery and vein for monitoring arterial pressure and blood gases and for delivering reagents, respectively. The intraluminal filament was then placed to induce focal cerebral ischemia. Fifteen minutes before reperfusion, rhodamine 6G (0.01%) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was injected intravenously to label neutrophils. Immediately prior to reperfusion, a craniotomy was performed to expose the microcirculation on the surface of the ischemic cortex. Reperfusion was then initiated by removal of the filament, the dura was opened and the animal was placed on a microscope stage. The brain surface was continuously superfused with artificial cerebral spinal fluid (aCSF). Using fluorescence video microscopy (Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ, USA and Zeiss, Thronwood, NY, USA), cell adhesion to cerebral venules was recorded (Mitsubishi U82) during reperfusion. During 15 minutes of reperfusion, at least six postcapillary venules in each animal were randomly selected and videotaped. On video playback, neutrophil adhesion, neutrophil rolling and shear rate were quantified by a blinded observer. Neutrophil adhesion (single cells and cells in aggregates) was expressed as the cell number/100µm venule. Neutrophil rolling was determined by drawing a vertical line on a venule and counting the number of cells rolling along the upper or lower margins of the vessel that crossed this line in 30 sec (#cells/30sec). Shear rate was calculated as 8(Vwbc/D), where Vwbc is (center neutrophil velocity/1.6) and D is venule diameter.

Flow cytometry

Whole blood was analyzed for CD11b adhesion molecule expression, a measure of neutrophil activation, using methods previously described (N= 3–5 animals/group)(25,30,32). Briefly, blood was withdrawn from the jugular vein of anesthetized animals prior to 4 hours of MCAO and fifteen minutes after reperfusion. Whole blood was diluted with bovine serum albumin (Sigma) in sodium azide staining buffer (BD Biosciences-Pharmingen, San Jose, CA, USA) and an Fc receptor-blocking agent (anti-CD32 monoclonal antibody, 5mg/ml) to decrease non-specific antibody binding. Whole blood was divided into aliquots and incubated with Phycoerythrin-Cy5-conjugated anti-CD45 antibody (BD Pharmingen), a pan-leukocyte marker, a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-CD11b antibody (BD Biosciences-Pharmingen) for detection of activated neutrophils, or a non-fluorescent IgG isotype control antibody to measure background fluorescence. Following incubation, samples were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde. Data were acquired using a flow cytometer (FACSCalibur, BD Biosciences-Pharmingen). Neutrophils, identified by positive fluorescence for CD45 antibody and selected from the total leukocyte population by cell size and granularity, were assessed for CD11b expression. A total of 10,000 cells were analyzed. Data are expressed as total fluorescence intensity (TFI), which is the product of % gated and the geometric mean of fluorescence, after subtraction of the fluorescence from unlabeled IgG antibody samples.

Real time RT-PCR analysis of cerebral gene expression

As previously described (10,32), brains were quickly removed (N = 4–9 animals/group) 4 hours after reperfusion in animals subjected to 4 hours of MCAO or sham-operation, divided into hemispheres, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −70°C. As previously described (30), total RNA was extracted from the ipsilateral hemisphere using TRI® Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) followed by 2.5M lithium chloride precipitation. RNA was run on a 1% agarose gel to check for purity and integrity. Total RNA (250 ng) was reverse transcribed (iScript, BioRad, Hercules, CA). Changes in expression levels of selected genes were detected by TaqMan real-time RT-PCR analysis using rat-specific primers for interleukin-1β (IL-1β) (Rn00580432_m1), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) (Rn00562055_m1), growth-related oncogene/keratinocyte chemoattractant (GRO/KC) (Rn00578225_m1), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) (Rn00564227_m1), endothelial cell selectin (E-selectin) (Rn00594072_m1), and an 18S primer for use as an internal control (Hs99999901_s1) (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Data were analyzed using the comparative cycle threshold (Ct) method as a means of relative quantitation of gene expression, normalized to the endogenous reference (18S RNA) and expressed relative to a calibrator (normalized Ct value obtained from SHAM brain) and expressed as 2−ΔΔCt, as described by the manufacturer (Applied Biosystems) (11,32). Changes in gene expression in the ipsilateral (injured) hemisphere in MCAO/R, is expressed as fold-increase over gene expression in non-ischemic (SHAM) hemisphere (10,32).

Analysis of gene expression and NF-kB activation in cultured human endothelial cells

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were purchased from Cascade Biologicals (Portland, OR, USA). Subconfluent HUVEC were plated in 75cm2 tissue culture flasks and incubated in fresh DMEM medium with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin overnight at 37°C with 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere. Human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBMVEC) were derived from microvessels isolated from temporal lobe tissue removed during operative treatment of epilepsy as previously described (3) and approved by the University of Arizona IRB. Data presented here using HBMVEC isolated from a 57 yo female subject were replicated in parallel experiments utilizing a mixed culture of HBMVEC isolated from 2 additional female subjects, aged 46 and 13 (data not shown). Subconfluent HBMVEC were plated in collagen-coated 25cm2 tissue culture flasks (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and incubated in fresh DMEM-F12 medium (Sigma St. Louis, MO) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone), 1% glutamax (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (Sigma St. Louis, MO), 2% ECGS (50µg/ml) (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and 3.4% heparin (1mg/ml) (Sigma St. Louis, MO) overnight at 37°C with 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere. For real-time RT PCR analysis (10,30), confluent flasks of HUVEC or HBMVEC (n = 3/treatment group) were then pre-incubated with curcuminoids (0.03 – 81 µM) for 4 hours before the addition of human recombinant TNF-α (5 ng/ml) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Total RNA was extracted from cells after one hour of TNF-α stimulation following manufacturer’s protocol using TRI® Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) followed by 2.5M lithium chloride precipitation. Cellular gene expression was analyzed by real time PCR using methodology previously described for brain samples and human specific primers for intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) (Hs00164932_m1), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) (Hs00365486_m1), endothelial cell selectin (E-selectin) (Hs00174057_m1), and an 18S primer for use as an internal control (Hs99999901_s1) (Applied Biosystems). For HUVEC, curcuminoid effects on gene expression in cells stimulated with TNF-α are expressed as percent change from TNF-α stimulated cells. Curcuminoid effects on cellular ICAM-1 gene expression in HBMVEC stimulated with TNF-α are expressed as fold change from untreated cells. For determination of curcuminoid effects on NF-κB activation by western analysis (16), nuclear cell extracts were prepared from confluent 75cm2 or collagen-coated 25cm2 tissue culture flasks of HUVEC or HBMVEC treated for 4 h with curcuminoids (27 µM or 81 µM, respectively) prior to 1 h stimulation with TNF-α (5ng/ml) using a nuclear extraction kit, as per manufacturer’s protocol (Millipore). Protein concentrations of each nuclear lysate were assayed by one-step colorimetric assay (Bio-Rad) and 25–50 µg protein was resolved by SDS-PAGE. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (BioRad). Membranes were placed in blocking solution (1x Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 and 5% nonfat milk) for 1 h and immunoblotted with rabbit anti- NF-κB p50 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) and anti- NF-κB p65 (Cell Signaling Technology) at a 1:1000 dilution in 1x Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 and 5% bovine serum albumin overnight on a rocking platform at 4°C. A rabbit anti-β-actin (Cell Signaling Technology) antibody at a 1:2000 dilution in 1x Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 and 5% bovine serum albumin was used as a control to verify equivalent protein loading. After incubation, membranes were washed and incubated with appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling) for 1 h at room temperature in 1x Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 and 5% nonfat milk. Membranes were then washed and developed using standard chemiluminescence protocols (Cell Signaling Technology).

Statistical analysis

All values are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis of in vivo neutrophil adhesion and rolling, blood velocity and shear rate in the microcirculation and in vitro cellular ICAM-1 gene expression in HBMVEC were performed using ANOVA with post hoc testing. Statistical analysis of neurological scoring was performed using non-parametric Mann-Whitney testing. For all other experiments, statistical differences between groups for parametric endpoints were assessed using one (where indicated) or two-tailed Student’s t-test, Welch corrected (InStat 3.0, Graphpad, San Diego, CA, USA). Differences were considered significant at P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

Effect of Curcuminoids on Infarct Size, Brain Edema, and Neurologic Function

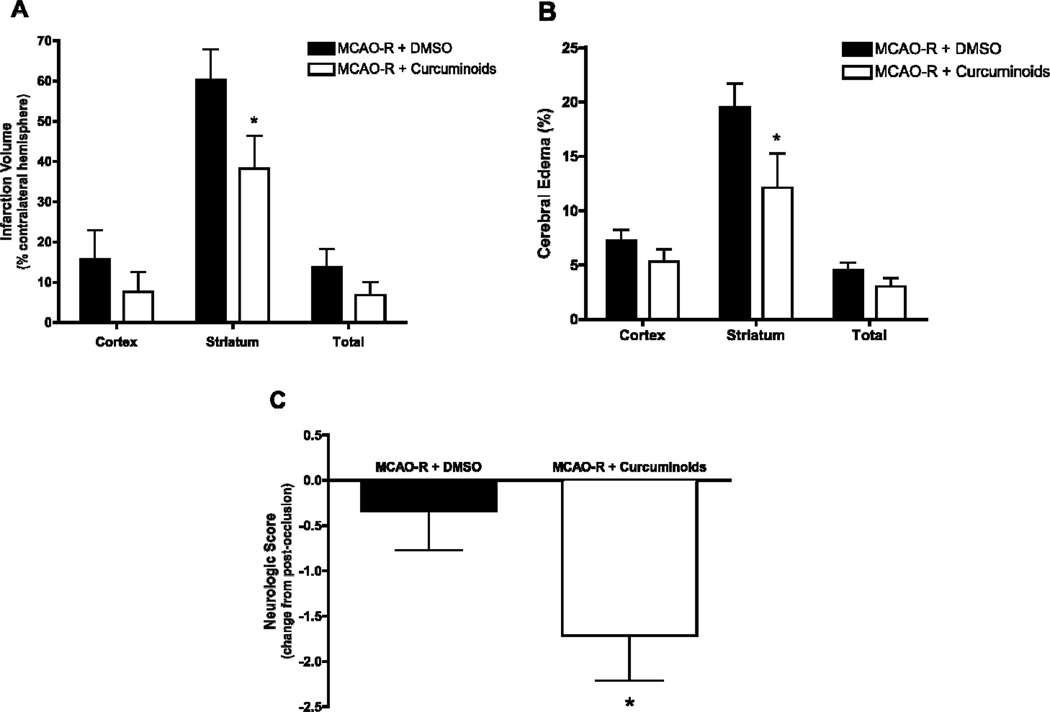

Consistent with previous reports, administration of curcuminoids (300 mg/kg ip) following occlusion but prior to reperfusion, decreased infarct size (Figure 1A) and brain edema at 24 h (Figure 1B). The major protective effect of curcuminoid treatment was documented in the striatum, where infarct and edema were decreased by 38% (P < 0.05). Consistent with these improvements in brain injury, neurologic function at 24 hours was also significantly improved by curcuminoid treatment; neurologic scores, which were no different between curcuminoid-treated and vehicle-treated rats prior to reperfusion (7.2 ± 0.2 vs. 6.8 ± 0.2, respectively), were significantly improved (decreased) following acute administration of curcuminoids (P < 0.05, Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Infarct volume, edema, and neurological scores 24 hr after MCAO/R in Sprague Dawley rats treated with curcuminoids (300mg/kg, n=7) or vehicle (DMSO, n=7) 1 h prior to reperfusion. (A) Infarction volume and (B) edema were evaluated in brains harvested from animals 24 h after reperfusion as described in Methods. Data are expressed as mean percent ± SEM and differences were evaluated by one-tailed unpaired t-tests (*p ≤ 0.05 relative to vehicle-treated control). (C) Neurological evaluation was performed 3 h after occlusion (just prior to treatment) and 24 h after reperfusion. Data are expressed as the mean change in neurological score ± SEM with the difference analyzed by one-tailed Mann-Whitney test (*p ≤ 0.05 relative to vehicle-treated control).

Effect of Curcuminoids on Neutrophil Adhesion to the Vascular Endothelium and Shear Rate Upon Reperfusion

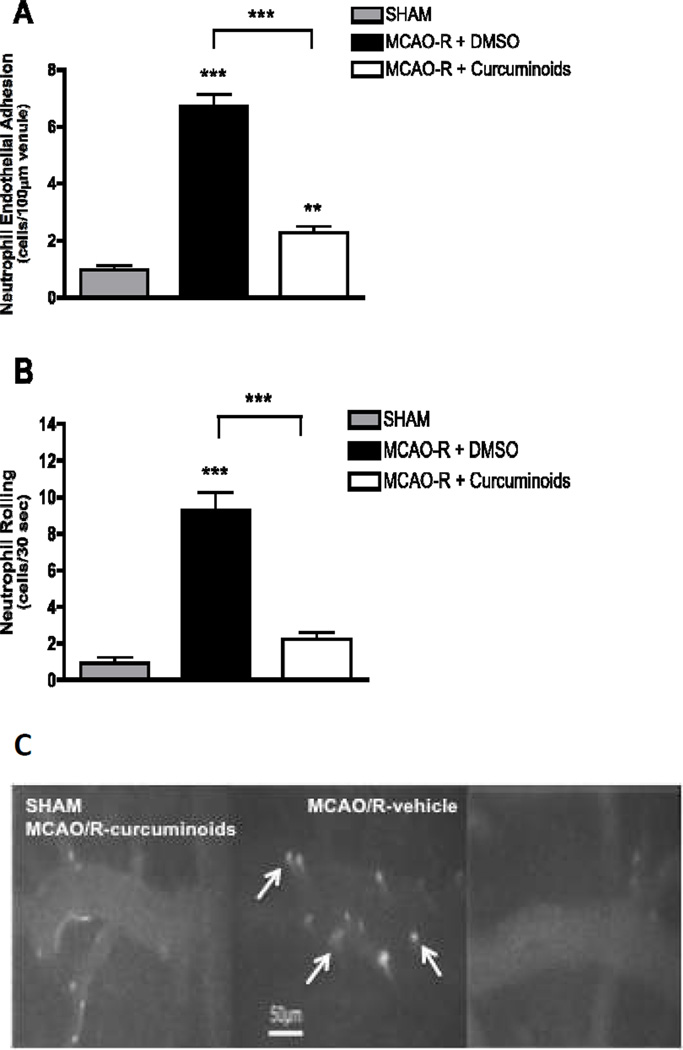

Immediately upon reperfusion (0–15 minutes), neutrophil adhesion to the vascular endothelium increased 7-fold in vehicle-treated MCAO/R vs. sham animals (Figure 2A) as observed in previous studies (31–33). Curcuminoid treatment prevented 67% of this increase in adherent neutrophils (Figure 2A). Curcuminoids also significantly decreased neutrophil rolling (76% inhibition, P < 0.001) as compared to vehicle-treated MCAO/R animals (Figure 2B); indeed, the number of rolling neutrophils, which was increased 10-fold in MCAO/R vs. sham animals, was statistically no different than sham animals in curcuminoid-treated MCAO/R animals. Representative photomicrographs demonstrating the increased number of rolling and adherent neutrophils in vehicle-treated MCAO/R animals (vs. sham) at 0–15 minutes of reperfusion and the marked inhibitory effects of curcuminoid treatment in MCAO/R animals are shown in Figure 2C. In addition, blood flow velocity (VWBC) following MCAO/R was markedly reduced to 24% of normal (sham) (Table 1). Curcuminoid-treatment of MCAO/R animals significantly increased VWBC (p < 0.01), restoring it to 60% of sham values (Table 1). Shear rates, which decreased by 76% in MCAO/R animals treated with vehicle (vs. sham), were similarly improved by curcuminoid treatment, which again prevented over 50% of the observed decrease in vehicle-treated MCAO/R animals (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Neutrophil adhesion to and rolling on microvascular endothelium at 0–15 minutes after reperfusion in male Sprague Dawley rats undergoing MCAO/R with vehicle (DMSO, n=4) or curcuminoid (300 mg/kg, n=4) treatment 1 h prior to reperfusion. (A) Neutrophil adhesion to venules and (B) neutrophil rolling are expressed as the cell number/100µm venule ± SEM with significance determined by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc testing (*p ≤ 0.05, ***p ≤ 0.001). (C) Representative photomicrographs demonstrating the increased number of rolling and adherent neutrophils in MCAO/R (vs. sham) animals at 0–15 minutes of reperfusion and the marked inhibitory effects of curcuminoid treatment on neutrophil adhesion.

Table 1.

Effects of curcuminoid treatment on cerebral microcirculation hemodynamics in Sprague Dawley rats subjected to MCAO/R (vs. sham surgery)

| Group | N | Diameter (µm) | Velocity (µm/sec) | Shear Rate (sec-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHAM | 6 | 46.7 +/− 2.1 | 5400 +/− 600 | 590 +/− 76.2 |

| MCAO + DMSO | 9 | 56.7 +/− 3.7 | 1578.4 +/− 165.3b | 141.8 +/− 14.9b |

| MCAO + TURM | 14 | 41.7 +/− 2.6 | 3317 +/− 478.1a,c | 381.2 +/− 45.5a,d |

p < 0.01 vs. SHAM,

p < 0.001 vs. SHAW,

p < 0.01 vs. MCAO/DMSO,

p < 0.001 vs. MCAO/DMSO

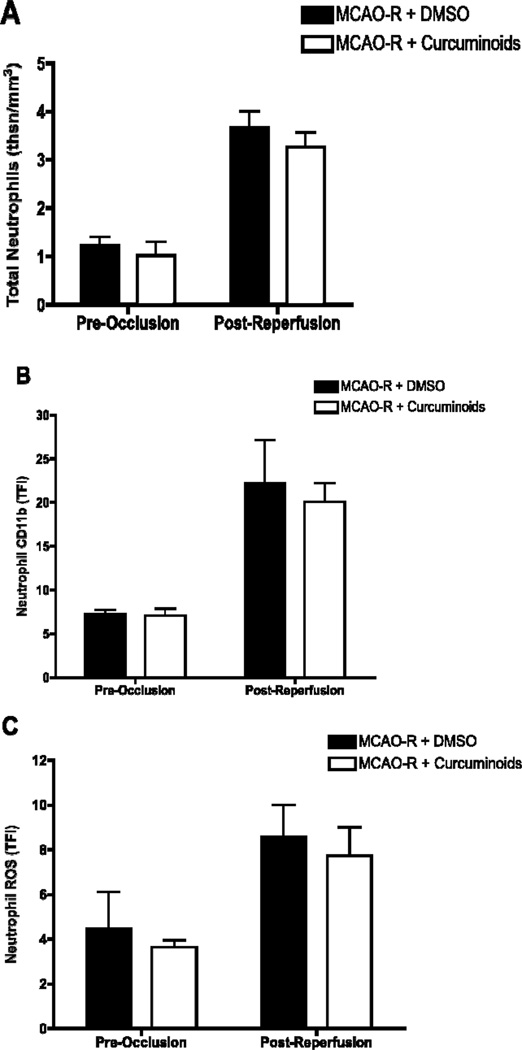

Effects of Curcuminoids on Neutrophils Immediately post-MCAO/R

Circulating neutrophil number, which was increased 3-fold immediately following reperfusion (0–15 minutes), was not altered by curcuminoid treatment as compared to vehicle (Figure 3A). The activation state of neutrophils immediately post-reperfusion was also not altered by curcuminoid-treatment; cell surface expression of CD11b (Figure 3B) and neutrophil production of ROS (Figure 3C), which were increased 3- and 2-fold respectively over baseline values following MCAO/R, were unchanged by curcuminoid treatment.

Figure 3.

Neutrophil number and activation state during early reperfusion in male Sprague Dawley rats undergoing MCAO/R following treatment with vehicle (DMSO, n=3–5) or curcuminoids (300mg/kg, n=4) 1 h prior to reperfusion. Blood was withdrawn from the jugular vein of anesthetized animals prior to 4 hours of MCAO and fifteen minutes after reperfusion. Whole blood, drawn 15 min after reperfusion (vs. 4 hours prior to MCAO), was analyzed by manual determination of differential WBC counts or flow cytometry as described in methods. (A) Total number of neutrophils expressed as (total WBC count × % neutrophils)/100 (thousands/mm3) ± SEM and analyzed using unpaired Student’s t-tests. (B) Cell surface expression of CD11b in neutrophils and (C) neutrophil production of ROS, expressed as total fluorescence intensity (TFI) ± SEM, were analyzed using unpaired Student’s t-tests.

Effects of Curcuminoids on Cerebrovascular Endothelium post-MCAO/R

Following MCAO/R, cerebral expression of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-1β) and genes specific to the activated vascular endothelium, which mediate neutrophil chemotaxis and adhesion (neutrophil chemokine, GRO/KC; adhesion factors, ICAM-1 and E-selectin), were significantly increased as compared to shams (Table 2; P < 0.05). Curcuminoid-treatment of MCAO/R animals decreased expression of these genes by > 30%, with IL-1 being the sole exception (Table 2). However, curcuminoid treatment effects on inflammatory gene expression only achieved statistical significance at this 4 h time point for inhibition of TNF-α, an important local mediator of cerebrovascular endothelial activation (5,37), and ICAM-1, the TNF-inducible endothelial protein required for neutrophil adhesion (5).

Table 2.

Effects of curcuminoids on cerebral gene expression in MCAO/R Sprague Dawley Rats

| GENE | MCAO+DMSO | MCAO+Curc | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1β | 6.31 ± 1.099 | 4.953 ± 1.97 | 21.5 |

| GRO/KC | 126.83 ± 33.461 | 86.536 ± 10.147 | 31.8 |

| TNFα | 7.126 ± 1.048 | 4.33 ± 0.272a,b | 39.2 |

| ICAM-1 | 4.497 ± 0.658 | 2991 ± 0.219b | 33.5 |

| E-selectin | 14.693 ± 2.868 | 9.868 ± 2.528 | 32.8 |

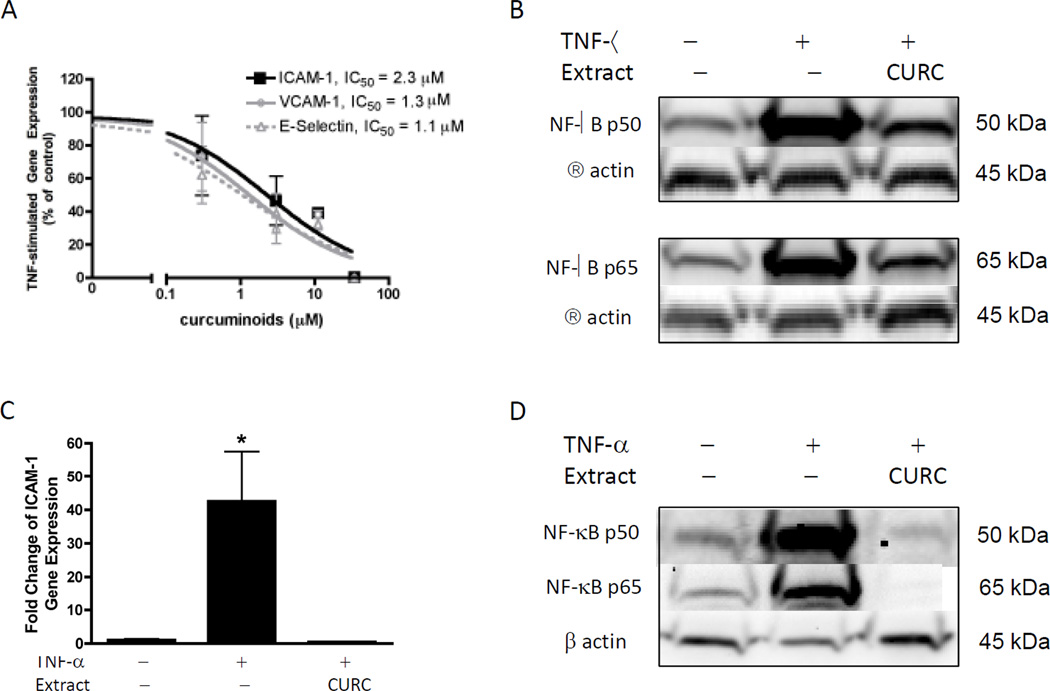

Effects of Curcuminoids on Human Vascular Endothelial Cell Activation

In vitro treatment of human endothelial cells derived from the umbilical vasculature (HUVEC) with TNF-α induced gene expression of the adhesion molecules, ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E selectin, >250-fold over those of control cells (data not shown, P <0.05). Curcuminoid treatment completely and potently (IC50 ~1–2 µM) inhibited TNF-α induced expression of ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E selectin (Figure 4A). Activation and nuclear translocation of the p50 and p65 subunits of NF-κB, the transcription factor mediating TNF-α effects on gene transcription in endothelial cells (41), were also inhibited by curcuminoid treatment of HUVEC (Figure 4B). To verify that this protective effect of curcuminoids extended to endothelial cells present in the human cerebrovascular microcirculation, curcuminoid inhibition of TNF-α-stimulated ICAM gene expression was verified in human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBMVEC) (Figure 4C). Curcuminoid inhibition of NF-kB activation and nuclear translocation in HBMVEC was similarly verified (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Effects of curcuminoids on TNF-α stimulated gene-expression and NF-κB activation in human endothelial cells derived from umbilical veins (HUVEC, A & B) or brain microvessels (HBMVEC, C & D). (A) HUVEC were pre-treated for 4h with curcuminoids (0.03 – 34 µM) before TNF-α (5 ng/ml) stimulation to induce ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and E-selectin gene expression, as determined by real-time RT PCR of cellular RNA isolated at 4 hours, as described in Methods. Data are expressed as percent of TNF-stimulated control ± SEM and analyzed using non-linear curve-fit regression. (B) HUVEC were pre-incubated with curcuminoids (27µM) for 4h before stimulation with TNF-α (5ng/ml) for 1h. Nuclear protein lysates were analyzed for NF-κB p50 and p65 protein expression by Western blotting using chemiluminescence. An antibody against β-actin was used to verify equivalent protein loading. (C) HBMVEC were pre-treated for 4h with curcuminoids (81 µM) before TNF-α (5 ng/ml) stimulation to induce ICAM-1 gene expression as determined by real-time RT PCR of cellular RNA isolated at 4 hours, as described in Methods. Data are expressed as fold-change relative to unstimulated controls (mean ± SEM) and analyzed using ANOVA with post-hoc testing. * p < 0.05 vs. controls. (D) HBMVEC were pre-incubated with curcuminoids (81 µM) for 4h before stimulation with TNF-α (5ng/ml) for 1h. Nuclear protein lysates were analyzed for NF-κB p50 and p65 protein expression by Western blotting using chemiluminescence. An antibody against β-actin was used to verify equivalent protein loading.

CONCLUSIONS

Experimental studies clearly demonstrate a potential role for curcumin, one of the three major polyphenols present in turmeric, in limiting oxidative brain injury in stroke (7,28,36,38,43,47). Not well explored in previous studies, however, was the precise mechanism(s) by which curcumin yielded this protective effect. Data presented here now provide unique evidence that curcuminoids act very early during reperfusion to inhibit (>70%) neutrophil rolling and adhesion to the cerebral microvascular endothelium. Because neutrophils are the primary source of oxidant injury during reperfusion, curcuminoids thus blocked a major contributor to reperfusion injury by preventing neutrophil targeting and accumulation at sites of ischemic insult following experimental stroke (4,8,14,29,34,42). Consistent with this marked reduction in cerebrovascular neutrophil-endothelial adhesion (NEA), curcuminoid treatment also improved microvascular hemodynamics, restoring blood velocity and shear rate back to 60% of normal, as compared to 25% of normal in MCAO/vehicle rats. Early inhibition of NEA was associated with later (24 h) improvements in neurologic function, infarct size and cerebral edema. Indeed, it is interesting to note that neurologic function in control animals did not improve following reperfusion, while neurologic function improved by almost 2 points (on a 12-point scale) with curcuminoid treatment, bringing the average total neurological score in curcuminoid-treated animals (5.5 ± 0.6) into a range associated with only minimal impairment (< 6). Thus, inhibition of neutrophil-mediated reperfusion injury appears to be an important pathophysiologic means by which curcuminoids protect the brain in stroke.

The cerebral endothelium and not the neutrophil, appeared to be the primary target for these early anti-inflammatory effects of curcuminoids in stroke, as evidenced by decreased ischemia-induced cerebral expression of TNF-α, a local inducer of endothelial activation (20,23,44,46), and cerebral endothelial cell expression of ICAM-1, the endothelial factor required for neutrophil adhesion (5,46), while the number and activation state (cell surface CD11b and ROS production) of circulating neutrophils was unchanged. Thus, these studies not only identify curcuminoid inhibition of neutrophil-endothelial adhesion (NEA) in cerebral microvasculature as an important pathophysiologic means by which curcuminoids protect the brain in stroke, but also pinpoint the injured vascular endothelium as its cellular target; inhibition of endothelial activation by curcuminoids appeared to be the cause of disrupted NEA in animals subjected to MCAO/R.

Blockade of NF-κB-mediated endothelial activation by purified curcumin has previously been described in vitro using human endothelial cells isolated from non-cerebral vascular beds (1,17,27). In vitro results presented here extend these findings to demonstrate that the naturally-occurring, mixture of curcuminoids present in turmeric dietary supplements, which were brain protective in experimental stroke, potently inhibited (IC50 ~ 1µM) human endothelial TNF-stimulated NF-κB activation and subsequent expression of ICAM and other adhesion molecules critical for NEA. Further critical evidence supporting the translational significance of curcuminoid inhibition of endothelial activation in experimental stroke comes from our verification that curcuminoids similarly inhibited NF-κB activation and NF-κB-driven ICAM gene expression in endothelial cells isolated from the human cerebrovascular microcirculation. To our knowledge, these novel experimental results are the first to demonstrate a protective effect of curcuminoids in the human cerebrovasculature. Because serum concentrations of conjugated curcuminoids exceeding the IC50 demonstrated here for curcuminoid inhibition of human endothelial cell activation have been documented in clinical studies testing this same curcuminoid formulation (40), this translational evidence supports the general tenet that turmeric dietary supplements similar in chemical composition to the product used here may have utility in the clinical management of stroke and stroke risk.

Curcumin has been reported to mitigate ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury in multiple organs, including brain, heart, kidney and intestine (7,13,15,28,36,38,43,45,47). However, to our knowledge, this is the first study to examine curcumin(oid) effects on neutrophil adhesion to the ischemic vascular endothelium in any organ. Thus, it is possible that the previously documented protective effects of curcuminoids during I/R injury in other organs may similarly be attributable to curcuminoid inhibition of ischemia-induced activation of the microvascular endothelial cells, a postulate that awaits further testing. Of significance, however, because NEA and leukocyte-mediated organ damage are not unique to ischemia-reperfusion injury (24,26,34), it is notable that our novel finding of curcuminoid inhibition of NEA during cerebral ischemia parallels two previous reports of curcumin inhibition of NEA following endotoxin injury in microcirculatory beds of the liver (22) and brain (39). Thus, the totality of current in vivo and in vitro evidence suggests that curcuminoid inhibition of NEA via targeting of NF-κB in the vascular endothelium may be a central mechanism explaining protective effects of curcumin(oids) in diseases characterized by inflammatory microvascular endothelial injury, of which stroke is but one important clinical example.

Certain limitations of our in vivo study design should be noted here. While stroke typically occurs in the aged population, the MCAO/R model cannot be performed in aged animals due to various technical limitations (21). However, previous studies by our laboratory and others demonstrating age-related increases in NEA in the ischemic cerebrovasculature when aged vs. young animals are subjected to global ischemia, a model for sudden cardiac death rather than stroke (29), suggest that curcuminoid-induced decreases in NEA are relevant for human stroke in the aged population. One additional limitation of our in vivo studies was our use exclusive use of male rats to document inhibitory effects of curcuminoids on endothelial activation during MCAO/R. However, our demonstration of similar protective effects of the curcuminoids in limiting the activation of endothelial cells derived from the human cerebrovascular microcirculation of women suggests that this effect is likely not sex-specific.

Because our in vivo stroke studies, in contradistinction to previous studies examining purified curcumin in stroke (7,28,36,38,43,47), examined cerebral effects of the naturally occurring mixture of curcuminoids present in turmeric rhizomes, results from our studies are consistent with a possible role of turmeric dietary supplements in the management of stroke risk. Indeed, the curcuminoid-enriched turmeric extract used in this study was chosen because its chemical composition, independently verified here, is similar to most commercial turmeric dietary supplements (11) and its pharmacokinetic and safety profile have already been studied in humans (6,19,35,40). One additional limitation of our study, however, was the use of a single, high ip dose of curcuminoids. However, the corresponding human equivalent dose (HED), after correcting for body surface area, is 3 g of curcuminoids, a dose that is high but within the range previously demonstrated to be safe in humans (6,20,35,40). Not tested here, but of obvious clinical importance are the effects of acute oral (vs. ip) turmeric on neutrophil-mediated reperfusion injury at time of stroke, as well as possible effects of chronic dietary supplementation with low-dose turmeric in mitigating neutrophil mediated injury at time of ischemic stroke. Previous reports documenting cerebroprotective effects of low dose oral curcumin treatment in rodent models of global ischemia (43) or Alzheimer’s disease (2), however, suggest that further pre-clinical trials are warranted to explore the potential benefits of curcuminoids in the setting of ischemic stroke.

PERSPECTIVES.

Decreased brain injury post-stroke occurred subsequent to marked inhibition of neutrophil adhesion to the cerebrovascular endothelium during early reperfusion due to targeting of the endothelial side of the leukocyte/endothelial interface by an acute administration of curcuminoids prior to reperfusion. As these studies were the first to examine brain-protective effects of a curcuminoid mixture analogous in composition to turmeric dietary supplements in stroke, the translation significance of these findings were confirmed by verifying the ability of curcuminoids to mitigate TNF-stimulated activation of endothelial cells derived from the human cerebrovascular microcirculation in vitro. These findings provide a foundation for future laboratory and clinical studies examining the utility of curcuminiods in the treatment of acute and chronic vascular inflammation and associated end-organ ischemic damage.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant # 0920 from the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (ABRC) to LR and JLF, with partial support from P20NR007794 from the National Institute of Nursing Research at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to JLF, the Hudson/Lovaas Endowment to PFM, and P50AT000474 from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine and the Office of Dietary Supplements of the National Institutes of Health to JLF and BNT. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of ABRC or the NIH.

Abbreviations

- aCSF

artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- E selectin

endothelial selectin

- HBMVEC

human brain microvascular endothelial cells

- HUVEC

human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- ICAM-1

intercellular adhesion molecule-1

- IL-1β

interleukin 1 β

- MCAO/R

middle cerebral artery occlusion and reperfusion

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa B

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- TTC

triphenyl tetrazolium chloride

- VCAM-1

vascular cell adhesion molecule-1

- WBC

white blood cell

- Vwbc

blood flow velocity

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmad M, Theofanidis P, Medford RM. Role of activating protein-1 in the regulation of the vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 gene expression by tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4616–4621. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.8.4616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Begum AN, Jones MR, Lim GP, Morihara T, Kim P, Heath DD, Rock CL, Pruitt MA, Yang F, Hudspeth B, Hu S, Faull KF, Teter B, Cole GM, Frautschy SA. Curcumin structure-function, bioavailability, and efficacy in models of neuroinflammation and Alzheimer's disease. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;326:196–208. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.137455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernas MJ, Cardoso FL, Daley SK, Weinand ME, Campos AR, Ferreira AJ, Hoying JB, Witte MH, Brites D, Persidsky Y, Ramirez SH, Brito MA. Establishment of primary cultures of human brain microvascular endothelial cells to provide an in vitro cellular model of the blood-brain barrier. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:1265–1272. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buck BH, Liebeskind DS, Saver JL, et al. Early neutrophilia is associated with volume of ischemic tissue in acute stroke. Stroke. 2008;39:355–360. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.490128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.del Zoppo GJ. Microvascular responses to cerebral ischemia/inflammation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;823:132–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhillon N, Aggarwal BB, Newman RA, et al. Phase II trial of curcumin in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4491–4499. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dohare P, Garg P, Jain V, Nath C, Ray M. Dose dependence and therapeutic window for the neuroprotective effects of curcumin in thromboembolic model of rat. Behav Brain Res. 2008;193:289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duilio C, Ambrosio G, Kuppusamy P, DiPaula A, Becker LC, Zweier JL. Neutrophils are primary source of O2 radicals during reperfusion after prolonged myocardial ischemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H2649–H2657. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.6.H2649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epstein J, Sanderson IR, Macdonald TT. Curcumin as a therapeutic agent: the evidence from in vitro, animal and human studies. Br J Nutr. 2010;103:1545–1557. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509993667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Funk JL, Migliati E, Chen G, Wei H, Wilson J, Downey KJ, Mullarky PJ, Coull BM, McDonagh PF, Ritter LS. PTHrP induction in focal stroke: a neuroprotective vascular peptide. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;284:R1021–R1030. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00436.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Funk JL, Frye JB, Oyarzo JN, Chen G, Lantz RC, Jolad SD, Solyom AM, Timmermann BN. Efficacy and mechanism of action of turmeric supplements in the treatment of experimental arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:3452–3464. doi: 10.1002/art.22180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Funk JL. Turmeric. In: Coates P, Betz JM, Blackman MR, et al., editors. Encyclopedia of Dietary Supplements. 2nd edition. Informa Healthcare; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammad FT, Al-Salam S, Lubbad L. Curcumin provides incomplete protection of the kidney in ischemia reperfusion injury. Physiol Res. 2012 Aug 8; doi: 10.33549/physiolres.932376. (Epub) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin R, Yang G, Li G. Inflammatory mechanisms in ischemic stroke: role of inflammatory cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;87:779–789. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1109766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karatepe O, Gulcicek OB, Ugurlucan M, Adas G, Battal M, Kemik A, Kamali G, Altug T, Karahan S. Curcumin nutrition for the prevention of mesenteric ischemia-reperfusion injury: an experimental rodent model. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:3611–3616. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kilgore KS, Schmid E, Shanley TP, Flory CM, Maheswari V, Tramontini NL, Cohen H, Ward PA, Friedl HP, Warren JS. Sublytic concentrations of the membrane attack complex of complement induce endothelial interleukin-8 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 through nuclear factor-kappa B activation. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:2019–2031. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim YS, Ahn Y, Hong MH, Joo SY, Kim KH, Sohn IS, Park HW, Hong YJ, Kim JH, Kim W, Jeong MH, Cho JG, Park JC, Kang JC. Curcumin attenuates inflammatory responses of TNF-alpha-stimualted human endothelial cells. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2007;50:41–49. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31805559b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurd SK, Smith N, VanVoorhees A, Troxel AB, Badmaev V, Seykora JT, Gelfand JM. Oral curcumin in the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis vulgaris: A prospective clinical trial. J Am Acad Dematol. 2008;58:625–631. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lao CD, Ruffin MT, 4th, Normolle D, Heath DD, Murray SI, Bailey JM, Boggs ME, Crowell J, Rock CL, Brenner DE. Dose escalation of a curcuminoid formulation. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2006;6:10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu T, Young PR, McDonnell PC, White RF, Barone FC, Feuerstein GZ. Cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant mRNA expressed in cerebral ischemia. Neurosci Lett. 1993;164:125–128. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90873-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu F, McCullough LD. Middle cerebral artery occlusion model in rodents: methods and potential pitfalls. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:464701. doi: 10.1155/2011/464701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lukita-Atmadja W, Ito Y, Baker GL, McCuskey RS. Effects of curcuminoids as anti-inflammatory agents on the hepatic microvascular response to endotoxin. Shock. 2002;17:399–403. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200205000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuo Y, Onodera H, Shiga Y, et al. Role of cell adhesion molecules in brain injury after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. Brain Res. 1994;656:344–352. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91478-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mazzoni MC, Schmid-Schönbein GW. Mechanisms and consequences of cell activation in the microcirculation. Cardiovasc Res. 1996;32:709–719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morrison H, McKee D, Ritter L. Systemic Neutrophil Activation in a Mouse Model of Ischemic Stroke and Reperfusion. Biol Res Nurs. 2011;13:154–163. doi: 10.1177/1099800410384500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oda M, Han JY, Nakamura M. Endothelial cell dysfunction in microvasculature: relevance to disease processes. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2000;23:199–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pendurthi UR, Williams JT, Rao LV. Inhibition of tissue factor gene activation in cultured endothelial cells by curcumin. Suppression of activation of transcription factors Egr-1, AP-1, and NF-kappa B. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:3406–3413. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.12.3406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rathore P, Dohare P, Varma S, et al. Curcuma oil: reduces early accumulation of oxidative product and is anti-apoptogenic in transient focal ischemia in rat brain. Neurochem Res. 2008;33:1672–1682. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9515-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ritter LS, Orozco JA, Coull BM, McDonagh PF, Rosenblum WI. Leukocyte accumulation and hemodynamic changes in the cerebral microcirculation during early reperfusion after stroke. Stroke. 2000;31:1153–1161. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.5.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ritter LS, Stempel KM, Coull BM, McDonagh PF. Leukocyte-platelet aggregates in rat peripheral blood after ischemic stroke and reperfusion. Biol Res Nurs. 2005;6:281–288. doi: 10.1177/1099800405274579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ritter L, Funk J, Schenkel L, Tipton A, Downey K, Wilson J, Coull B, McDonagh P. Inflammatory and hemodynamic changes in the cerebral microcirculation of aged rats after global cerebral ischemia and reperfusion. Microcirculation. 2008;15:297–310. doi: 10.1080/10739680701713840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ritter L, Davidson L, Henry M, Davis-Gorman G, Morrison H, Frye JB, Cohen Z, Chandler S, McDonagh P, Funk JL. Exaggerated Neutrophil-Mediated Reperfusion Injury after Ischemic Stroke in a Rodent Model of Type 2 Diabetes. Microcirculation. 2011;18:552–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2011.00115.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruehl ML, Orozco JA, Stoker MB, McDonagh PF, Coull BM, Ritter LS. Protective effects of inhibiting both blood and vascular selectins after stroke and reperfusion. Neurol Res. 2002;24:226–232. doi: 10.1179/016164102101199738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmid-Schonbein GW. The damaging potential of leukocyte activation in the microcirculation. Angiology. 1993;44:45–56. doi: 10.1177/000331979304400108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharma RA, McLelland HR, Hill KA, Ireson CR, Euden SA, Manson MM, Pirmohamed M, Marnett LJ, Gescher AJ, Steward WP. Pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic study of oral Curcuma extract in patients with colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1894–1900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shukla PK, Khanna VK, Ali MM, Khan MY, Srimal RC. Anti-ischemic effect of curcumin in rat brain. Neurochem Res. 2008;33:1036–1043. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9547-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stanimirovic DB, Wong J, Shapiro A, Durkin JP. Increase in surface expression of ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-selectin in human cerebromicrovascular endothelial cells subjected to ischemia-like insults. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 1997;70:12–16. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6837-0_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thiyagarajan M, Sharma SS. Neuroprotective effect of curcumin in middle cerebral artery occlusion induced focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Life Sci. 2004;74:969–985. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vachharajani V, Wang SW, Mishra N, El Gazzar M, Yoza B, McCall C. Curcumin modulates leukocyte and platelet adhesion in murine sepsis. Microcirculation. 2010;17:407–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2010.00039.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vareed SK, Kakarala M, Ruffin MT, Crowell JA, Normolle DP, Djuric Z, Brenner DE. Pharmacokinetics of curcumin conjugate metabolites in healthy human subjects. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:1411–1417. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Voraberger G, Schäfer R, Stratowa C. Cloning of the human gene for intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and analysis of its 5'-regulatory region. Induction by cytokines and phorbol ester. J Immunol. 1991;147:2777–2786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang CX, Shuaib A. Neuroprotective effects of free radical scavengers in stroke. Drugs Aging. 2007;24:537–546. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200724070-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Q, Sun AY, Simonyi A, et al. Neuroprotective mechanisms of curcumin against cerebral ischemia-induced neuronal apoptosis and behavioral deficits. J Neurosci Res. 2005;82:138–148. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Worthmann H, Tryc AB, Goldbecker A, et al. The temporal profile of inflammatory markers and mediators in blood after acute ischemic stroke differs depending on stroke outcome. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;30:85–92. doi: 10.1159/000314624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yeh CH, Chen TP, Wu YC, Lin YM, Jing Lin P. Inhibition of NFkappaB activation with curcumin attenuates plasma inflammatory cytokines surge and cardiomyocytic apoptosis following cardiac ischemia/reperfusion. J Surg Res. 2005;125:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang RL, Chopp M, Li Y, et al. Anti-ICAM-1 antibody reduces ischemic cell damage after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. Neurology. 1994;44:1747–1751. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.9.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao J, Zhao Y, Zheng W, Lu Y, Feng G, Yu S. Neuroprotective effect of curcumin on transient focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Brain Res. 2008;1229:224–232. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.06.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]