Abstract

The study purpose was to evaluate a computer-based questionnaire (SCKnowIQ) and CHOICES educational intervention using cognitive interviewing with childbearing-aged people with sickle cell disease (SCD) or trait (SCT). Ten control group participants completed the SCKnowIQ twice. Ten intervention group participants completed the SCKnowIQ before and after the CHOICES intervention. Most participants found the questionnaire items appropriate and responded to items as the investigators intended. Participants’ responses indicated that the information on SCD and SCT and reproductive options was understandable, balanced, important, and new to some. Internal consistency and test-retest reliability were adequate (.47 to .87) for 4 of the 6 scales, with significant within-group changes in knowledge scores for the intervention group but not for the control group. Findings show evidence for potential efficacy of the intervention, but proof of efficacy requires a larger randomized study.

Keywords: sickle cell disease, sickle cell trait, reproductive, computer-based education, cognitive interviews

Childbearing-aged people with an inherited condition such as sickle cell disease (SCD) or carriers of the sickle cell trait (SCT) face many challenges concerning their reproductive behavior. Unfortunately, measures for knowledge, attitudes and skills related to or interventions focused on reproductive behavior in people with SCD or SCT are unavailable. When new behaviors or populations are studied, usually a new questionnaire is developed (French, Cooke, McLean, Williams, & Sutton, 2007) and formative research is needed to validate it and assess its reliability. Similarly, formative research is needed to demonstrate how understandable and appropriate new interventions are for the intended audience, especially those interventions designed for populations vulnerable to health disparities, such as people with SCD. To overcome these gaps, we created the Sickle Cell Reproductive Health Knowledge Parenting Intent Questionnaire (SCKnowIQ) and a multimedia Internet-based CHOICES intervention. The purpose of this study was to conduct a formative mixed method evaluation of SCKnowIQ items and the CHOICES intervention using cognitive interviews with childbearing-aged people with SCD or SCT.

SCD affects mainly people of African, Mediterranean, Asian subcontinent, or Latin descent. Understanding of the disease and its symptoms, pathology and therapy are low in those most at risk (Boyd, Watkins, Price, Fleming, & DeBaun, 2005). The knowledge of the patterns of SCD inheritance is particularly limited (Boyd, et al., 2005; Gallo, Knafl, & Angst, 2009; Hershberger, 2007; Hershberger & Pierce, 2010). For many of those with SCD or SCT, the decision whether or not to have a child occurs with insufficient understanding of heritability of the SCD or SCT and the serious health consequences to the affected offspring. The decision to have a child is influenced by such factors as faith/religion, SCD severity (Ahmed, Atkins, Hewison, & Greer, 2006), economic status and partners’ opinions (Aquilino & Losch, 2005; Canady, Tiedje, & Lauber, 2008). Some people with SCD express strong opinions about foregoing parenthood to avoid passing the disease or the trait to their children or grandchildren (Gallo et al., 2010).

Reproductive health decisions and behaviors are complex and have been studied extensively in adults in a variety of situations (Ahluwalia, Johnson, Rogers, & Melvin, 1999; Joyce, Kaestner, & Korenman, 2002; Rosengard, Phipps, Adler, & Ellis, 2004), but are not well studied in people with SCD or SCT (Asgharian & Anie, 2003; Gallo et al., 2010). Intention to be a parent may change over time and reflect the parents’ emotional state before, during, or after pregnancy (Sable & Libbus, 2000; Sable & Wilkinson, 1998). Furthermore, reproductive health intentions in male partners have a strong influence on female partners’ intention to conceive and decisions about pregnancy termination (Rosengard, Phipps, Adler, & Ellis, 2005). According to the Theory of Reasoned Action (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980), personal factors such as knowledge can influence an individual’s intention to become a parent and reproductive health behaviors. Other personal factors such as reproductive health beliefs and attitudes and subjective norms may influence reproductive health intentions and behaviors (Wang, Charron-Prochownik, Sereika, Siminerio, & Kim, 2006), but these factors have not been reported for people with SCD or SCT. Unfortunately, there are virtually no studies published to date regarding parenting intentions expressed by persons with SCD or SCT (Asgharian & Anie, 2003; Gallo et al., 2010). Men and women with SCD or SCT can decide to not bear a child, to bear a child who is unaffected (without SCD), affected with SCD, or a carrier (SCT), or to seek other non-childbearing options such as parenting an unaffected, non-biological child (e.g., foster, adopt) (Asgharian & Anie, 2003; Gallo et al., 2010). We postulate that for a person with SCD or SCT, the decision whether or not to reproduce is influenced by the person’s knowledge of the genetic transmission of SCD or SCT and risks of pregnancy to the mother, as well as the person’s perception of the SCD severity (Asgharian & Anie, 2003; Gallo et al., 2010). Unfortunately, with regard to making informed decisions about becoming a parent, investigators found that nearly half of the parents lacked sufficient knowledge of the genetic transmission of SCD or SCT (Gallo et al., 2009).

A logical approach to foster informed reproductive health decisions by people with SCD or SCT is to enhance their reproductive health knowledge by providing tailored information about the options and consequences of those reproductive options so that their reproductive health behaviors are consistent with the reproductive health intentions they specify in advance of a pregnancy (their intention to implement a parenting plan). This is the focus of our newly developed CHOICES intervention with outcomes to be measured by means of the SCKnowIQ. Development of both the instrument and intervention was informed by extensive formative work including focus group findings (Gallo et al., 2010), feedback from a cultural expert with extensive research experience among African American communities, and advice from a lay advisory board of young adults with SCD or SCT. This prior work demonstrated cultural relevance and an appropriate health literacy level of the instrument and intervention. The aim of our second formative study of young adults with either SCD or SCT who were considering parenthood was to examine the content validity and reliability of the SCKnowIQ, the understandability and appropriateness (validity) of the CHOICES intervention, and the potential of the SCKnowIQ to detect changes after the intervention.

Methods

Design

We accomplished the study aim with a two-group, repeated-measures design. Because this research was focused on methodology issues (validity, reliability, sensitivity) and feasibility (appropriateness), the participants were sequentially assigned to control and intervention groups. The first group completed the study questionnaire twice separated by 4 weeks (control group). The second group completed the questionnaire before and after completing the intervention (intervention group). The control group engaged in a cognitive interview as they individually completed each questionnaire item, and the intervention group engaged in a cognitive interview as they individually completed each screen of the intervention and completed the questionnaire items before and after the intervention.

This study was approved by the University of Illinois at Chicago’s (UIC) Institutional Review Board before its initiation. All participants provided written informed consent before proceeding with study procedures.

Setting

Participants with SCD were all patients of the University of Illinois (UI) Sickle Cell Clinic and were recruited at the UI Hospital & Health Sciences System in Chicago and/or referred to the study by the Sickle Cell Center Community Outreach Coordinator. People with SCT were also referred by the Outreach Coordinator or recruited from the UI Pediatric Sickle Cell Clinics. Participants completed study procedures at a place convenient to them, including the UIC College of Nursing, another UIC location, at participants’ homes, or another community location chosen by the participant.

Sample

Eligible participants had either SCD or SCT, were able to have children and would probably have them in the future, were 18 to 35 years old, and could speak and read English. Potential participants were excluded if they were legally blind; physically or cognitively unable to complete the study procedures (e.g., not able to use the computer or follow directions); reported a health history of hysterectomy, tubal ligation, medically or surgically induced menopause or vasectomy that would prevent ability to bear children; or reported a desire to remain childless or have no further children.

The sample of 20 included 16 women (80%) and 4 men (20%), all Black or African American, 9 with SCD and 11 with SCT. Their mean age was 27 ± 5 years; other sample demographic characteristics appear in Table 1. There was no statistically significant difference in subject characteristics between intervention and control groups.

Table 1. Sample Demographic Characteristics by Intervention and Control Groups (N = 20).

| Characteristics* | Intervention (n = 10) |

Control (n = 10) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| N | % | N | % | |

| Marital | ||||

| Never Married | 8 | 80 | 7 | 70 |

| Married/Separated | 2 | 20 | 3 | 30 |

|

| ||||

| Education | ||||

|

| ||||

| Grade School or High school (1 – 12) | 1 | 10 | 3 | 30 |

|

|

||||

| Some college | 5 | 50 | 6 | 60 |

|

|

||||

| 4-year college or graduate degree | 4 | 40 | 1 | 10 |

|

| ||||

| Employment | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes, part-time | 3 | 30 | 5 | 50 |

|

|

||||

| Yes, full-time | 3 | 30 | 1 | 10 |

|

|

||||

| Not employed | 3 | 30 | 2 | 20 |

|

|

||||

| Not employed, full-time student | 1 | 10 | 2 | 20 |

|

| ||||

| Health Insurance | ||||

|

| ||||

| Employer or union | 3 | 30 | 2 | 20 |

|

|

||||

| Medical card (Medicaid) | 6 | 60 | 7 | 10 |

|

|

||||

| No insurance/ Other | 1 | 10 | 1 | 10 |

|

| ||||

| Ethnicity | ||||

|

| ||||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 10 | 100 | 10 | 100 |

|

| ||||

| Race | ||||

|

| ||||

| Black/African American | 10 | 100 | 10 | 100 |

|

| ||||

| Income | ||||

|

| ||||

| $0-$9,999 | 4 | 40 | 2 | 20 |

|

|

||||

| $10,000-$29,999 | 2 | 20 | 3 | 30 |

|

|

||||

| $40,000-$49,999 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 10 |

|

|

||||

| $50,000-$74,999 | 1 | 10 | 2 | 20 |

|

|

||||

| $75,000-$99,999 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 10 |

|

|

||||

| Other (specify) | 1 | 10 | 1 | 10 |

|

| ||||

| Partner has Sickle Cell Disease | ||||

|

| ||||

| No | 5 | 50 | 6 | 60 |

|

|

||||

| Don’t know | 1 | 10 | 2 | 20 |

|

|

||||

| No partner | 4 | 40 | 2 | 20 |

|

| ||||

| Partner has Sickle Cell Trait | ||||

|

| ||||

| No | 5 | 50 | 5 | 50 |

|

|

||||

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 |

|

|

||||

| Don’t know | 1 | 10 | 2 | 20 |

|

|

||||

| No partner | 4 | 40 | 2 | 20 |

|

| ||||

| Relative has Sickle Cell Disease | ||||

|

| ||||

| No | 3 | 30 | 3 | 30 |

|

|

||||

| Yes | 7 | 70 | 7 | 70 |

Note:

No significant difference in subject characteristics between intervention and control group.

Procedures

Participants used a grant-purchased pen-tablet (toshiba.com) with touch screen technology to complete the study questionnaire and view the intervention. Trained research specialists conducted one-on-one cognitive interviews with the control group as participants individually answered the questionnaire (n = 10) and the intervention group as participants individually viewed each screen of the educational intervention (n = 10). All sessions were audiotape-recorded. All participants completed the questionnaire twice: before and after the cognitive interview. The intervention group completed the second questionnaire immediately after the cognitive interview, whereas the control group completed the second questionnaire 4 weeks after the cognitive interview session. No attrition occurred over the study period. We compensated participants $60 for their time (about 2 to 4 hours) and travel expenses.

Instruments

Cognitive interviews

Cognitive interviewing is an approach to better understand how the participant formulates a response to the subject matter of each item or topic and is useful to reveal problems (Jha et al., 2010; Knafl et al., 2007; Strack & Martin, 1987; Tourangeau, 1987; Tourangeau & Raskinski, 1988). Ultimately, cognitive interviewing findings can improve information gained from questionnaires and improve the quality of data collected as well as refine an intervention. In this study, audio-taped cognitive interviews were used to assess participants for their understanding, information retrieval, judgment and response editing as they completed the SCKnowIQ items (see Table 2 for probes). Probes for the understanding of the CHOICES intervention screens were: What did you think about when you read this information? How well do you think you will remember this information? What are your suggestions for changing this information?.

Table 2. Cognitive Interview Dimensions and Probes.

| Cognitive Dimension | Probes for SCKnowIQ |

|---|---|

| Understanding and interpretation (what does the question mean to the respondent and is the meaning different from that intended) |

What did you think about when you answered this question? |

| Please repeat the question in your own words? | |

| Information retrieval (Do respondents recall relevant information to answer the question?) |

How did you decide which answer you would pick for this question? |

| Judgment formation (Respondent frames answer consistent with recalled information) |

Did you think about your answer as it applies to you now or at another time? |

| If at another, when? Why did you choose that time? | |

| Response editing (Respondent gives socially desirable response or shows acquiescence.) |

Do you think other people like you would answer the question in the same way or some other way? |

SCKnowIQ

The SCKnowIQ development was guided by the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA). To develop its 89 items and item responses, we used literature reviews of previously developed instruments on reproduction (Kaslow, 2000; Koontz, Short, Kalinyak, & Noll, 2004; Rosengard et al., 2004, 2005), focus group findings from older adults with SCD or SCT (Gallo et al., 2010), lay advisory group feedback, and expert consensus. The questionnaire includes demographic and influencing factors (23 items focused on gender, age, ethnicity, marital status, years of education completed, annual family income, SCD of self/partner/relative, SCT of self and partner, use of hydroxyurea, severity of SCD, type of insurance, number of previous pregnancies, number of children, prior use of computers, and current access to computers) and five subscales related to TRA concepts: (1) Sickle Cell Disease and Reproductive Knowledge (18 items focused on genetic transmission of SCD and SCT, the etiology of SCD, parenting options for people with SCD or SCT, types of contraceptives safe for people with SCD or SCT, and the risks of complications during pregnancy for the woman with SCD); (2) Informed Reproductive Health Decisions (3 items focused on importance, likelihood and influencers of being a parent); (3) Intention to Implement a Parenting Plan/Parenting Intent (15 items focused on intention to not bear a child, to bear a child who is unaffected [without SCD], affected with SCD, or a carrier [SCT], or to seek other non-childbearing options such as parenting an unaffected, non-biological child [e.g., foster, adopt]); (4) Reproductive Health Behaviors/Behaviors Related to Intentions (17 items focused on behaviors engaged in during the past 6 months to implement the parenting plan); and (5) Reproductive Health Attitudes and Beliefs (13 items focused on relative importance of attitudes and normative considerations). Response options vary by subscale: multiple choice options with a single correct option (knowledge subscale); 0-to-5 Likert scales regarding how important, likely, influenced, happy, or concerned; 0-to-4 agree/disagree scale; or other item-specific options. We expected the average participant would require 30 to 45 min to complete the SCKnowIQ.

Intervention

The CHOICES intervention is an Internet-based, tailored, multimedia education program about reproductive options and consequences. We designed CHOICES to help men and women with SCD and SCT to develop and implement a parenting plan that supports their informed reproductive health decision and reproductive health behaviors. We used the Kolb Experiential Learning Theory (ELT) (Claxton & Murrell, 1987; Kolb, Boyatzis, & Mainemelis, 2000) to guide intervention development. We used the simplified ELT concept of teaching around the circle, which includes four basic concepts (Claxton & Murrell, 1987): (1) concrete experience in which we provided a video, audio or text-based case study or clinical practice simulation that allowed the participant to involve him/herself in a concrete experience related to reproductive issues relevant to people with SCD or SCT; (2) reflective observation in which we guided the participant to reflect on the concrete experience from different perspectives (partner, family members, spiritual leader, etc.); (3) abstract conceptualization in which we guided the participant to engage with content about SCD, SCT and reproductive issues and behaviors; and (4) active experimentation in which we guided the participant to explore the content in video clips of the perspectives of other couples who made a variety of decisions and engaged in a variety of behaviors and discussed the consequences they faced. The CHOICES content is highly interactive and experiential. To create the intervention, we incorporated ideas from focus groups of people 36 years old and older with SCD and SCT (Gallo et al., 2010), a lay advisory board involving young people with SCD and SCT, and a panel of experts in SCD and SCT who evaluated the content appropriateness of the intervention before we initiated this study with cognitive interviews. We expected the average participant to require 2 hours to complete the CHOICES intervention.

Data Analysis

SCKnowIQ

Two research specialists transcribed verbatim into a text file the interviews by questionnaire item and each of the cognitive interview probes. Using content analysis, the first two authors (AMG, DJW) independently reviewed the ten transcripts and identified problems and concerns for each questionnaire item. Then, the two authors met, verified that the research specialists followed the protocol without leading the participant to a specific response, discussed the problems and concerns reported by participants and established agreement by consensus regarding the final modifications and refinements to the questionnaire.

CHOICES intervention

Research specialists listened to each entire cognitive interview, but transcribed only those sections that indicated any problems or issues with the materials, such as comments indicating lack of understanding, material requiring clarification or comments suggesting inappropriate or insensitive material. Using content analysis, the first two authors each independently reviewed half of the transcripts (n = 5 each, 10 total) and identified problems and concerns for each intervention screen. Then, the two authors met, re-read and discussed the problems and concerns and established agreement by consensus regarding the final modifications and refinements to the intervention.

We analyzed quantitative data using univariate and graphical methods to facilitate inspection and interpretation of data. We employed descriptive statistics including means, frequencies, and standard deviations to describe sample demographic characteristics. We used Cronbach’s alpha and intraclass correlation (ICC) to evaluate internal consistency and test-retest reliability for the SCKnowIQ. We measured pre-post differences in SCKnowIQ scores within each experimental group using paired t tests. Finally, we conducted repeated measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA) to examine the group difference on increasing SCKnowIQ score over time. Statistical significance was established at an alpha level of .05. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 statistical software.

Results

Cognitive Interviews: SCKnowIQ

Understanding and interpreting questionnaire items

Most of the content of each questionnaire item was interpreted by participants as we intended, and the item format was deemed acceptable to the participants. When participants decided on their responses to each questionnaire item about SCD, SCT and reproductive options, they relied on three main themes: past experiences with SCD and SCT, previous knowledge about SCD and SCT, and individual perceptions. Past experiences included their own and family members’ medical histories, symptoms, quality of life and management of the illness. Previous knowledge included either formal or informal prior education on inheritance patterns and transmission of SCD and SCT in the family and the need for testing for SCT. Individual perceptions included beliefs and attitudes about making decisions and the desire to become a parent, and the ways to avoid having a child with SCD.

Making sense of the questionnaire or problems with questionnaire

Whereas most participants understood the terminology and language used in the questionnaire items, some shared their difficulties in understanding the terminology of several items related to advanced reproductive technologies and medical procedures. For example, four participants were not familiar with the word, “sterilization surgery,” three with “tested fertilized eggs,” and two with “tested sperm.” As one participant indicated, “I never have [heard of] the concept [tested fertilized eggs], so I do not know. It is not something that I had done, because I do not understand, I never heard about it.”

A few participants were confused by questionnaire items with terms and phrases such as “partner,” the sickle cell disease medication “hydroxyurea,” and the information about sickle cell disease and pregnancy. Seven participants’ responses indicated that they saw some items as duplicates even when the item stem indicated it referred specifically to SCD or SCT. Two participants thought that questions they interpreted as duplicate were “trick” questions to see if the participants answered the questions consistently.

Other participants indicated that some items were not important or did not have applicability or relevance to their situation. These items related to becoming a parent, having an abortion or sterilization surgery, using advanced reproductive technologies, or adopting a child. For example, one woman found it difficult to think about all the ways an individual can become a parent, as she had no experience with the many choices for reproductive options. Another participant clearly did not see having prenatal testing as applicable to her, “It’s irrelevant to me because I don’t have a baby or didn’t have a baby in the past.”

We learned that participants were comparing their own experiences to the questionnaire item content. For example, participants had received education about SCD and SCT in the past and were familiar with the basic concepts.

For the 18 knowledge questionnaire items, most participants tried to reason out their answer choice based on their past knowledge of and past experiences with SCD and SCT and inheritance patterns and their own and family members’ experiences. For example, in some cases, participants talked about what they remembered about figures and charts that they had reviewed in the past that provided probabilities of having children with sickle cell disease. When participants could not remember previous information or did not have the information necessary to make an answer choice, they guessed on the answer or selected, “I don’t know.”

Although two participants had strong feelings about abortion, they indicated that keeping the item in the questionnaire was important because others may have different life experiences and may make different choices. As one participated noted, “I am not at all likely to get an abortion because I don’t believe in abortions. If I’m gonna have a baby, I’m gonna have a baby, whether it has sickle cell disease or not. But… [other] people might think a different way than I do….everybody doesn’t have the same viewpoints on abortions.”

Seven participant response focused on concerns about the tone of a few questionnaire items that focused on attitudes and beliefs. For example, most participants did not like the use of the word “happy,” in two separate items that asked how happy they would be if they became pregnant with a baby who had SCD [or SCT]. Most of these participants indicated that having a baby is a happy time even if a child has the trait; he/she is healthy and will live a normal life. One participant said of having a baby with SCT, “Well, I think about having a baby. The trait, yes, that it’s not a big risk. I’d be happy. Happy, happy, happy, happy.” Three participants thought that the two items focusing on ways to actively avoid having children with SCD and SCT were problematic because they thought that they did not have control over the situation of having a child with or without the disease or trait. A few participants provided concrete suggestions for several of the items.

Cognitive Interviews: CHOICES Intervention

Overall, participants were positive about the information presented in the educational program. They found the content important and informative for people with SCD and SCT, and they drew on their personal experiences and knowledge about SCD and SCT to understand and interpret the information. Although five participants already knew the basic information about SCD and SCT, four participants found this content to be new information. One participant exclaimed, “I’m stunned because I just learned about the red blood cells and what hemoglobin does. They transfer oxygen, that I wasn’t aware of; wow, this [page] definitely caught my attention because it’s telling me the percentage on the trait as well as the disease. I didn’t know.”

Information about assisted reproductive technology (ART) options was new information for most participants. Participants thought that this information provided a balanced view about ART and that it was important to include in the program. The men reflected further on the pregnancy and ART information and thought that women would appreciate this specific information more than men. However, three participants were concerned about the cost of ART and the inability of most people to pay for the procedures. Two participants indicated that the information about the inheritance of SCD and SCT was “a lot to remember” and suggested that additional visual reinforcements should be added to this section. One participant did not understand why fostering a child would be a potential option in this program.

While four participants stated that abortion and prenatal testing were not options for them and suggested that the content be removed from the program, others recommended that the information be included in the educational program because people have different opinions about these procedures and the program needs to be balanced with information on all sides of the issues. As one participant said, “I don’t believe in abortion, but I can’t just say that [it shouldn’t be included in the program] because it’s only my opinion. Everybody has their own opinion. I say you can put it out and get different feedback on it.”

Five participants expressed the importance of including information about SCT in addition to SCD in the educational program too. For example, one participant said, “It’s [the program] finally starting to touch on some of the things that come with the trait. This is the first time [SCT has] been introduced … This is one of the things that’s going to help people understand how important [SCT] is.” Other participants remarked about the importance of people learning about SCT and testing for SCT. As one participant said, “I don’t think a lot of people realize the importance to being tested with SCT.”

Overall, content presented by video was received positively, and it was seen as reinforcing content provided in the text. As one participant said of a video where a couple was deciding about their future relationship, “I liked the whole re-enactment part. Show the part of what would have happened if they would have stayed together….” Two participants thought that one video was not realistic in the way it presented the consequences of SCD. As one participant said about the video, “[The video] kinda greets you with a touch of sugar so it will be easier for you to digest it better. It should be more realistic.” Most participants indicated that they would remember the information in the educational program because it kept them interested; they indicated that the videos and animations helped them to remember the information too.

Most participants recommended minor changes to the educational program. Their suggestions concentrated on adding or condensing information about the types, treatment and complications of SCD and reproductive options, including more visual illustrations or changing a few visuals that they thought were not appropriate, changing the wording, sentence structure, and the placement and layout of the pages, and deleting repetitive content.

Reliability of the SCKnowIQ

The initial assessment of internal consistency of the SCKnowIQ indicates adequate reliability (.47 to .87) for 4 of the 6 scales, considering the small sample (Table 3). Internal consistency was higher for the posttest measure than the pretest. Not surprisingly, the concern scale with 2 items had low internal consistency. Additional assessment of internal consistency and item analysis are indicated by this initial evaluation. Test-retest reliability ranged from .44 to .91, with the behavior scale illustrating the lowest intraclass correlations.

Table 3.

Internal Reliability and Test-Retest Reliability for SCKnowIQ (N = 20)

| Scale | Internal Reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) |

Test-retest Reliability (ICC) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | ||

| Knowledge (18 items) | .79 | .76 | .62 |

| Parenthood decision (2 items) | .82 | .84 | .91 |

| Intention (13 items) | .57 | .78 | .79 |

| Behavior (all 17 items) | .47 | .65 | .44 |

| Attitude (4 items) | .86 | .87 | .91 |

| Concerns (2 items) | .42 | .55 | .89 |

Sensitivity of the SCKnowIQ

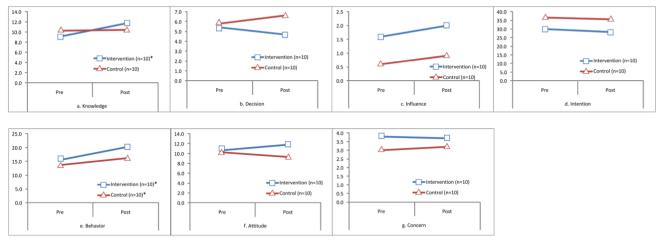

The Figure 1 panels show the pre- to post-test changes for each scale by group. Within-group t tests indicated that the instrument was sensitive to changes in knowledge scores (p <. 05) for the intervention group that had access to the CHOICES intervention but that there was no change in knowledge scores (p =. 92) for the control group that did not have access to the intervention (Figure 1a). The within-group comparisons of pre- to posttest scores for the other 4 scales were not sensitive to the intervention in this small sample. In the RM-ANOVA model, none of the group-by-time interactions was statistically significant. However, if observed trends (Figure 1a-g) from this small sample are replicated in a randomized controlled trial of the CHOICES intervention with a larger sample, it is plausible that group effects could be detected for the knowledge, decision, behavior, intention, and attitude scales but possibly not for influence or concern. Therefore, the domains of the intervention show some indication of change after the education program.

Figures 1a-1g.

Pre-Post Trends by Group for SCKnowIQ Scale.

Note: None of the Group × Time interactions were statistically significant in the small sample (N = 20).

*p < .05 (pre-post paired t test)

Scale (possible range of scores): meaning of higher score

a. Knowledge (0-18): Higher score indicates better knowledge

b. Decision (0-8): Higher score indicates higher likelihood of wanting to become a parent

c. Influence (0-4): Higher score indicates more likely to be influenced by others

d. Intention (0-47): Higher score indicates higher risk of having a child with SCD or SCT

e. Behavior-17 items (0-38): Higher score indicates health behaviors led to lower risk of having a child with SCD or SCT

f. Attitudes (0-16): Higher score indicates higher level of attitude against having a child with SCD or SCT

g. Concern (0-8): Higher score indicates higher level of concerns about having a child with SCD or SCT

Discussion

We found that cognitive interviewing was useful in the validation and refinement of the SCKnowIQ questionnaire and the CHOICES educational intervention for adults with SCD or SCT of childbearing age. Overall, participants were positive about the SCKnowIQ items and the CHOICES intervention information presented on laptop computers in the text, videos, images and animations. Participants drew from their personal experiences to understand and interpret the questionnaire items and the key messages in the CHOICES intervention. Most participants found the questionnaire items appropriate, and their responses supported validity of the items. Specifically, the cognitive interview responses indicated that they were interpreting the questions as the investigators intended and were able to find an answer option that reflected their situation. Participants’ responses also indicated that the information on SCD and SCT and reproductive options was balanced, important and new to some participants. They recommended inclusion of the questionnaire and the education information in the program. The internal consistency and stability reliability of the questionnaire is adequate for a new instrument and warrants its evaluation in a larger study, but in that study some subscales may require removal of items to improve reliability. Our sample was too small for item analysis statistics to be meaningful.

Study findings support content validity and informed decisions to keep, delete or modify questionnaire items and add, delete or modify the text, pictures and videos in the CHOICES intervention. Future research is needed to validate the construct validity of the SCKnowIQ, another important aspect of validity testing that was beyond the scope of this study. Further research is needed to improve internal consistency of the behavior, intention, and concerns scales by refining the items contributing to these scores and to determine the stability of the knowledge and behavior scales in an adequately sized sample. The sensitivity of the SCKnowIQ to change after the intervention requires confirmation in a larger sample.

Limitations detract from the study findings. Because of the intensive nature of the cognitive interviews on either the questionnaire or the CHOICES intervention, we were not able to assess the exact amount of time required to complete the entire program. Also the sample was small because of the cognitive interview approach, which provided only estimates of the instrument reliability and sensitivity. It is possible that the cognitive interview process may have decreased the intervention effect because responding to those detailed questions distracted the participant from the learning process that would occur without the distraction. Although the sample was predominately female, the participants’ cognitive processing provided valuable insights on the relevance of the SCKnowIQ and the CHOICES educational intervention to both men and women. In future studies, special efforts are likely to be needed to recruit sufficient numbers of men to participate if findings will be sufficiently relevant to young men with SCD or SCT. Finally, the sample was entirely African American and it is unknown if individuals with SCD or SCT and from other ethnic groups would have similar responses. A Hispanic participant contributed similar responses in the prior focus group research that guided development of the SCKnowIQ and the CHOICES educational intervention (Gallo et al., 2010), which supports likely relevance to other ethnic groups.

Despite these limitations, the cognitive interviewing process reflected the value of including input from people with SCD or SCT in validating an instrument and educational intervention. To often this validity step is missing during the instrument and intervention development process, and it is not until they are tested in randomized studies that the validity issues emerge. Built on the advice of focus group participants who were older than 35 years, had SCD or SCT, and had prior experience with reproductive decisions, our instrument and intervention had many strengths and required relatively few changes to be meaningful to young adults with SCD or SCT. We have confidence from our cognitive interview findings that the instrument items measure what we intend and are culturally appropriate for young adults with SCD or SCT.

Application

Despite the small sample, there was adequate internal consistency and test-retest reliability for 4 of the 6 scales and significant within-group changes in knowledge scores for the intervention group but not for the control group. These findings are encouraging and support our plans to implement a randomized controlled trial of the CHOICES intervention with outcomes measured with the SCKnowIQ in 200 people with SCD or SCT. Clearly, as part of this additional research there is a need to verify the internal consistency and stability of the SCKnowIQ. Application of these findings in practice is premature until findings of the randomized clinical trial are available. With adequate research, the CHOICES intervention has potential to be the first primary prevention intervention for SCD, which could be an important public health advance that could reduce the burden of this disease on patients, families, and the healthcare system.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by Grant Number U54HL090513 from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. The final peer-reviewed manuscript is subject to the National Institutes of Health Public Access Policy. The authors acknowledge Veronica Angulo and Mary Blythe Richardson for their assistance and Kevin Grandfield for editorial assistance. A special thanks to all who participated in the Lay Advisory Board and cognitive interviews.

References

- Ahluwalia IB, Johnson C, Rogers M, Melvin C. Pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system (PRAMS): Unintended pregnancy among women having a live birth. Journal of Women’s Health & Gender-Based Medicine. 1999;8:587–589. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1.1999.8.587. doi:10.1089/jwh.1.1999.8.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S, Atkin K, Hewison J, Green J. The influence of faith and religion and the role of religious and community leaders in prenatal decisions for sickle cell disorders and thalassaemia major. Prenatal Diagnosis. 2006;26:801–809. doi: 10.1002/pd.1507. E-publication. doi: 10.1002/pd.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Predicting behavior from intentions. In: Ajzen I, editor. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. Prentice-Hall, Inc.; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1980. pp. 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Aquilino ML, Losch ME. Across the fertility lifespan: desire for pregnancy at conception. MCN American Journal of Maternal and Child Nursing. 2005;30(4):256–262. doi: 10.1097/00005721-200507000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asgharian A, Anie KA. Women with sickle cell trait: reproductive decision-making. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2003;21(1):23–34. doi: 10.108010264683021000060057. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd JH, Watkins AR, Price CL, Fleming F, DeBaun MR. Inadequate community knowledge about sickle cell disease among African-American women. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2005;97(1):62–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canady RB, Tiedje LB, Lauber C. Preconception care & pregnancy planning: Voices of African American women. MCN American Journal of Maternal and Child Nursing. 2008;33(2):90–97. doi: 10.1097/01.NMC.0000313416.59118.93. doi: 10.1097/01.NMC.0000313416.59118.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claxton CS, Murrell PH. Learning styles: Implications for improving educational practices. ERIC Clearinghouse on Higher Education at the George Washington University; Washington, DC: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- French DP, Cooke R, McLean N, Williams M, Sutton S. What do people think about when they answer theory of planned behaviour questionnaires? A ‘think aloud’ study. Journal of Health Psychology. 2007;12(4):672–687. doi: 10.1177/1359105307078174. doi: 10.1177/1359105307078174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo AM, Knafl KA, Angst DB. Family information management patterns in childhood genetic conditions. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2009;24(3):194–204. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo AM, Wilkie D, Suarez M, Labotka R, Molokie R, Thompson A, Johnson B. Reproductive decisions in people with sickle cell disease or sickle cell trait. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2010;32(8):1073–1090. doi: 10.1177/0193945910371482. doi: 10.1177/0193945910371482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershberger PE. Pregnant, donor oocyte recipient women describe their lived experience of establishing the “family lexicon”. Journal of Obstetrical, Gynecological & Neonatal Nursing. 2007;36(2):161–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2007.00128.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2007.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershberger PE, Pierce PF. Conceptualizing couples’ decision making in PGD: Emerging cognitive, emotional, and moral dimensions. Patient Education Counseling. 2010;81(1):53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.11.017. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha A, Suarez ML, Ferrans CE, Molokie R, Kim YO, Wilkie DJ. Cognitive testing of PAINReportIt in adult African Americans with sickle cell disease. Computers, Informatics, Nursing. 2010;28(3):141–150. doi: 10.1097/NCN.0b013e3181d7820b. doi: 10.1097/NCN.0b013e3181d7820b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce T, Kaestner R, Korenman S. On the validity of retrospective assessments of pregnancy intention. Demography. 2002;39(1):199–213. doi: 10.1353/dem.2002.0006. doi: 10.1353/dem.2002.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaslow NJ. The efficacy of a pilot family psychoeducational Intervention for pediatric sickle cell disease. Families, Systems & Health. Journal of Collaborative Family Health Care. 2000;18(4):381–205. [Google Scholar]

- Knafl K, Deatrick J, Gallo AM, Holcombe G, Bakitas M, Dixon J, Grey M. The analysis and interpretation of cognitive interviews for instrument development. Research in Nursing & Health. 2007;30(2):224–234. doi: 10.1002/nur.20195. doi: 10.1002/nur.20195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb DA, Boyatzis RE, Mainemelis C. Experiential learning theory: Previous research and new directions. In: Sternberg RJ, Zhang LF, editors. Perspectives on cognitive, learning, and thinking styles. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2000. pp. 227–248. [Google Scholar]

- Koontz K, Short AD, Kalinyak K, Noll R. A randomized, controlled pilot trial of a school intervention for children with sickle cell anemia. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2004;29(1):7–17. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh002. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosengard C, Phipps MG, Adler ME, Ellis JM. Adolescent pregnancy intentions and pregnancy outcomes: A longitudinal examination. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35:453–461. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.02.018. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosengard C, Phipps MG, Adler ME, Ellis JM. Psychosocial correlates of adolescent males’ pregnancy intentions. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):414–418. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0130. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-0130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sable MR, Libbus MK. Pregnancy intention and pregnancy happiness: Are they different? Maternal & Child Health Journal. 2000;4(3):191–196. doi: 10.1023/a:1009527631043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sable MR, Wilkinson DS. Pregnancy intentions, pregnancy attitudes, and the use of prenatal care in Missouri. Maternal & Child Health Journal. 1998;2(3):155–165. doi: 10.1023/a:1021827110206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strack F, Martin L. Thinking, judging, and communicating: A process account of context effects in attitude surveys. In: H H-J, Schwarz N, Sudman S, editors. Social information processing and survey methodology. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1987. pp. 123–144. [Google Scholar]

- Tourangeau R. Attitude measurement: A cognitive perspective. In: Hippler H, Scharwartz N, Sudman S, editors. Social Information Processing and Survey Methodology. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1987. pp. 149–162. [Google Scholar]

- Tourangeau R, Raskinski R. Cognitive processes underlying context effects in attitude measurement. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103:209–314. [Google Scholar]

- Wang SL, Charron-Prochownik D, Sereika SM, Siminerio L, Kim Y. Comparing three theories in predicting reproductive health behavioral intention in adolescent women with diabetes. Pediatric Diabetes. 2006;7(2):108–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-543X.2006.00154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]