Abstract

Objective

To investigate which neuropsychological tests predict eventual progression to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in both Hispanic and non-Hispanic individuals. Although our approach was exploratory, we predicted that tests that underestimate cognitive ability in healthy aging Hispanics might not be sensitive to future cognitive decline in this cultural group.

Method

We compared first-year data of 22 older adults (11 Hispanic) who were diagnosed as cognitively normal but eventually developed AD (decliners), to 60 age- and education-matched controls (27 Hispanic) who remained cognitively normal. To identify tests that may be culturally biased in our sample, we compared Hispanic with non-Hispanic controls on all tests and asked which tests were sensitive to future decline in each cultural group.

Results

Compared to age-, education-, and gender-matched non-Hispanic controls, Hispanic controls obtained lower scores on tests of language, executive function, and some measures of global cognition. Consistent with our predictions, some tests identified non-Hispanic, but not Hispanic, decliners (vocabulary, semantic fluency). Contrary to our predictions, a number of tests on which Hispanics obtained lower scores than non-Hispanics nevertheless predicted eventual progression to AD in both cultural groups (e.g., Boston Naming Test [BNT], Trails A and B).

Conclusions

Cross-cultural variation in test sensitivity to decline may reflect greater resistance of medium difficulty items to decline and bilingual advantages that initially protect Hispanics against some aspects of cognitive decline commonly observed in non-Hispanics with preclinical AD. These findings highlight a need for further consideration of cross-cultural differences in neuropsychological test performance and development of culturally unbiased measures.

Keywords: preclinical Alzheimer’s disease, Spanish–English bilingual, Hispanic, verbal fluency, object naming

Neuropsychological testing provides important information that aids in the diagnosis of dementia associated with probable Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The clinical utility of neuropsychological testing has grown as normative data have been developed to gauge cognitive impairment at an early stage of the disease. There is also consensus that neural changes of AD begin prior to the observation of significant clinical symptoms (i.e., “preclinical AD”; see Sperling et al., 2011), suggesting that subtle cognitive changes occur prior to the point at which a clinical diagnosis of probable AD can be made with any certainty. Thus, the field has shifted to identifying preclinical neuropsychological markers of AD in an attempt to provide earlier diagnosis and treatment options for individuals who will eventually develop AD (for review, see Twamley, Ropacki, & Bondi, 2006). This shift in neuropsychological research in recent years has shown that episodic and semantic memory are particularly vulnerable to early changes in preclinical AD (Bäckman, Small, & Fratiglioni, 2001; Bondi et al., 1994; Bondi, Salmon, Galasko, Thomas, & Thal, 1999; Lange et al., 2002; Linn et al., 1995; Mickes et al., 2007; Woodard et al., 2010). Subtle deficits on tests of executive functioning have also been found in elderly individuals who later develop AD (Chen et al., 2000, 2001; Clark et al., 2012; Dickerson, Sperling, Hyman, Albert, & Blacker, 2007; Rapp & Reischies, 2005), but may not be as prominent as those in episodic and semantic memory (Mickes et al., 2007).

An important omission from research on cognitive changes in preclinical AD is the consideration of cultural differences that may exist in normative data or in the impact of disease on cognition in minority populations compared with the dominant population that is usually studied. Given that there is a growing minority population in the United States (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010), it is increasingly important to determine to what extent existing normative data can be used with minority populations for the purpose of early diagnosis of AD. A number of studies have shown that individuals of other cultures underperform on certain neuropsychological tests, and steps have been taken to reduce or eliminate such biases (e.g., Ardila, Rosselli, & Puente, 1994; Judd et al., 2009; Pedraza & Mungas, 2008; Siedlecki et al., 2010). For example, Siedlecki and colleagues (2010) used structural equation modeling to determine whether a set of neuropsychological tests exhibited measurement invariance across English and Spanish speakers, and found that English speakers obtained higher scores on all tests in the battery. Because of this scalar invariance, they cautioned against comparing means across English- and Spanish-speaking samples. However, given the metric invariance they observed, they also concluded that the same constructs are likely being measured across both language groups—a conclusion that could suggest that, despite measurement bias, the measures will be sensitive to impairment across groups. A review by Pontón and Ardila (1999) suggested that education, ethnicity, language spoken, acculturation, and age are important and complex variables that cannot be ignored as they can impact test performance in Hispanics.

Along these lines, Hispanic minorities in the United States are often Spanish–English bilinguals and this can also influence neuropsychological test performance. Bilingualism is associated with advantages on some cognitive tests and disadvantages on others (for review, see Bialystok, Craik, Green, & Gollan, 2009), either of which can make it more difficult to interpret an individual’s pattern of performance with reference to monolingual normative data. Bilinguals may exhibit cognitive advantages compared with matched monolinguals on several measures of executive function. For example, young adult bilinguals exhibited smaller Stroop interference effects (e.g., Bialystok, Craik, & Luk, 2008) and were faster to resolve response conflict than monolinguals on the Simon Task (Bialystok, Craik, Klein, & Viswanathan, 2004) and the Attentional Network Task (e.g., Costa, Hernández, Costa-Faidella, & Sebastián-Gallés, 2009; Costa, Hernández, & Sebastián-Gallés, 2008). Bilingual advantages may also increase with age. For example, Bialystok et al. (2004) found that the bilingual advantage on the Simon Task was larger in older than in younger adults. This suggests that executive control may decline more slowly in aging bilinguals than in aging monolinguals. Consistent with this possibility, Kavé, Eyal, Shorek, and Cohen-Mansfield (2008) found better maintenance of cognitive status in aging with increasing number of languages spoken.

Bilingual advantages on executive tasks have also been found in young children and even in 7- to 12-month-old babies (Kovács, 2009; Kovács & Mehler, 2009; also see Bialystok, 1999, 2010; Bialystok & Martin, 2004; Bialystok & Shapero, 2005; Carlson & Meltzoff, 2008; Martin-Rhee & Bialystok, 2008). For example, Bialystok (2010) found that bilingual 6-year-olds were faster in completing both Trailmaking Test Parts A and B than matched monolinguals. These bilingual advantages in executive control may have developed to allow bilinguals to manage competition between their two languages when conversing. Though the precise underlying mechanisms and cause of bilingual advantages are currently being debated, there is an emerging consensus that some form of executive control is necessary for successful language control in bilinguals (Abutalebi & Green, 2007; Bialystok et al., 2009; Gollan & Ferreira, 2009; Hernandez, 2009).

Contrary to these effects, bilingualism has been shown to produce disadvantages on language tasks (for review, see Kroll & Gollan, in press). Bilinguals have more difficulty naming pictures than monolinguals, resulting in more tip-of-the-tongue states (Gollan & Silverberg, 2001), slower naming times, and higher error rates, even when naming pictures in their dominant language (Gollan, Montoya, Fennema-Notestine, & Morris, 2005; Ivanova & Costa, 2008). Bilinguals also produce lower scores on standardized measures of picture naming, such as the Boston Naming Test (BNT). Roberts, Garcia, Desrochers, and Hernandez (2002) administered the BNT to monolingual and French–English and Spanish–English bilingual adults, and found significantly lower scores for bilinguals compared with age- and education-matched monolinguals. The BNT is commonly used in the neuropsychological assessment of dementia and has shown declines during the preclinical period of AD (e.g., Howieson et al., 1997; Jacobs et al., 1995; Mickes et al., 2007). It is not clear, however, if this test would be diagnostically useful in bilinguals, given that cognitively healthy bilingual individuals perform less well on this test than matched monolinguals.

Verbal fluency is another commonly used neuropsychological measure that is susceptible to a bilingual disadvantage. Cognitively healthy young adult bilinguals produce fewer correct responses than monolinguals on verbal fluency tests (Gollan, Montoya, & Werner, 2002; Portocarrero, Burright, & Donovick, 2007). Even more problematic for the detection of early AD is that this bilingual disadvantage resembles the effect of AD on fluency. Studies have shown that semantic fluency is more adversely affected by AD than phonemic fluency (e.g., Butters, Granholm, Salmon, Grant, & Wolfe, 1987; Henry, Crawford & Phillips, 2004). Similarly, the bilingual disadvantage is greater for semantic fluency than phonemic fluency in both young (Gollan et al., 2002) and older adults (Rosselli et al., 2000). Given these results, it is not clear if bilingualism will attenuate the pattern of fluency deficits associated with AD in monolinguals, or if a further discrepancy between semantic and phonemic fluency should be expected for bilinguals when they begin to develop AD. It is interesting, however, that a study by Salvatierra, Rosselli, Acevedo, and Duara (2007) showed that cognitively healthy elderly bilinguals produced more responses in semantic than in phonemic fluency tasks (but see Gollan et al., 2002), whereas bilinguals with AD produced equal (though lower than normal) numbers of responses in both tasks. These results suggest that a greater decline in semantic fluency than phonemic fluency remains evident in bilinguals with AD. It remains to be determined, however, whether or not verbal fluency (particularly semantic fluency) is as effective in detecting preclinical AD in bilinguals as it is in monolinguals (e.g., Albert, Moss, Tanzi, & Jones, 2001; Clark et al., 2009; for reviews, see Twamley et al., 2006, and Henry et al., 2004).

A further complication for predicting future onset of AD in Hispanic elderly is that differences have been reported for age of onset and rate of progression of AD in Hispanics compared with non-Hispanics. Several studies report an earlier age of onset of AD in Hispanic older adults compared with non-Hispanics, after adjusting for education (Clark et al., 2005; Livney et al., 2011; also see Ringman & Flores, 2005). In contrast, several studies have found no difference in the age of onset of AD in Hispanics and non-Hispanics (Duara et al., 1996; Kwon, Khaleeq, Chan, Pavlik, & Doody, 2011). More recent work reveals bilingualism and education level to be interacting predictors of age of onset in Hispanics, with increasing degrees of bilingualism delaying diagnosis of AD in Hispanics with low education but not in those with high education (Gollan, Salmon, Montoya, & Galasko, 2011).

Some studies report longer survival rates in Hispanics with AD compared with non-Hispanics (Cosentino, Scarmeas, Albert, & Stern, 2006; Helzner et al., 2008; Mehta et al., 2008; Waring, Doody, Pavlik, Massman, & Chan, 2005). Whether this is due to differences in age of diagnosis or biological factors is still unclear. Mehta and colleagues (2008) suggest that future studies can address such concerns by examining longitudinal data that can indicate a person’s degree of cognitive decline independent of population normative data that may not be applicable to groups who are limited by language barriers and education level (see also Mulgrew et al., 1999). An open question, given these many differences between cultural groups, is whether the same tests are sensitive to preclinical AD across groups. It seems possible that the answer to this question would be “yes,” provided that culturally and linguistically matched normative samples are used, as has sometimes been done in the past (e.g., Lucas et al., 2005; Pontón et al., 1996). On the other hand, it is likely that culture-specific normative data could not circumvent all of the problems associated with the use of tests that were designed for a different cultural group (see Gasquoine, 1999; Manly & Echemendia, 2007; Pontón & Ardila, 1999). For example, Peña (2007; see also Artiola i Fortuny et al., 2005) warns that translated tests focus on linguistic equivalence but do not consider functional, cultural, and metric equivalence, which are of equal importance and, if not considered, may threaten the validity of even carefully and accurately translated measures (see also Judd et al., 2009, and standards recommended by the International Test Commission, 2010).

Given these questions, we took an exploratory approach to investigating differences between Hispanic and non-Hispanic elderly adults on a battery of commonly used neuropsychological tests. Our overarching goal was to determine which tests might be useful as preclinical markers of AD regardless of cultural group. Existing research on cognitive measures that are useful for predicting future decline in individuals with preclinical AD has focused almost exclusively on non-Hispanic Caucasians (e.g., Mickes et al., 2007; for review, see Twamley et al., 2006). We began by comparing baseline neuropsychological test performance of non-Hispanic and Hispanic participants who remained cognitively healthy in subsequent years (i.e., “robust” normal controls) in a longitudinal study at the UCSD Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) to determine which cognitive tests might be affected by culture or bilingualism. We then examined which tests were sensitive to eventual progression to AD in patients who were initially diagnosed as normal but subsequently declined. Finally, we asked if some tests that were sensitive to eventual progression to AD in one cultural group were sensitive in the other cultural group, and considered the possible theoretical implications of such differences.

Method

Participants

Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1. All procedures at the ADRC received institutional ethics approval from the UCSD Human Research Protection Program, and all participants provided written informed consent. To identify Hispanics and non-Hispanics who began participation at the ADRC prior to developing a diagnosis of probable AD, we screened longitudinal data from 126 Hispanic and 370 non-Hispanic participants who entered the ADRC study as normal control participants (1990 to the present). Participants with a history of alcoholism, drug abuse, severe psychiatric disturbances, severe head injury, and learning disabilities are excluded from participation in the ADRC study. Upon their first evaluation (i.e., Year 1 or baseline), participants were judged to be cognitively normal by two senior staff neurologists based on medical, neurological, and neuropsychological evaluations, and a number of laboratory tests used to rule out possible causes of dementia (see Galasko et al., 1994, for more details). Of these participants, 11 initially normal Hispanics were eventually diagnosed with probable AD during annual ADRC reevaluations, an average of 5.0 years later (see Table 1).1 Probable AD was diagnosed using criteria developed by the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke (NINCDS) and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (ADRDA; McKhann et al., 1984). Diagnosing neurologists were not aware of specific test scores but were provided with a general statement regarding the evaluation results (e.g., “a deficit in two or more areas of cognition”). These “decliner” participants were then matched for age, education, and years prior to diagnosis, to 11 non-Hispanic participants who were also normal initially and were later diagnosed with probable AD an average of 5.2 years later. These 11 non-Hispanic decliners were randomly selected from a larger group of non-Hispanic decliners who were carefully matched to Hispanics on age, education, and years prior to diagnosis. The respective non-Hispanic and Hispanic decliners were then matched for age and education to 33 non-Hispanic and 27 Hispanic normal controls who remained cognitively healthy for the duration of their participation in the ADRC study, and for at least two consecutive years (but many remained in the study as controls for additional years [an average of 9.2 years for Hispanics and 6.7 years for non-Hispanics]).

Participant Demographics for Non-Hispanic Normal Controls and Decliners and Hispanic Normal Controls and Decliners

| Hispanic normal controls (n = 27) |

Hispanic decliners (n = 11) |

Non-Hispanic normal controls (n = 33) |

Non-Hispanic decliners (n = 11) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Age | 72.1 | 4.0 | 71.7 | 5.1 | 73.5 | 5.4 | 73.0 | 8.2 |

| % Female | 52 | — | 91 | — | 55 | N/A | 55 | N/A |

| Education | 12.3 | 3.2 | 12.8 | 3.7 | 11.9 | 0.9 | 12.1 | 1.8 |

| Years prior to diagnosis | — | — | 5.0 | 3.6 | — | — | 5.2 | 2.8 |

| Percent tested in English | 41 | — | 36 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Age 1st exposure to English | 9.1b | 10.1 | 8.0C | 11.2 | — | — | — | — |

| Age 1st exposure to Spanish | 0.0b | 0.0 | 0.0d | 0.0 | — | — | — | — |

| % Currently using Spanish | 39.9b | 39.8 | 44.8d | 43.9 | — | — | — | — |

| Self-ratingsa | ||||||||

| Spoken English | 5.6b | 1.9 | 5.8d | 1.5 | — | — | — | — |

| Spoken Spanish | 5.7b | 1.3 | 5.8d | 1.6 | — | — | — | — |

| Writing English | 5.2b | 2.0 | 5.7d | 1.8 | ||||

| Writing Spanish | 4.6b | 2.1 | 5.6d | 2.2 | ||||

| Reading English | 5.5b | 1.8 | 5.9d | 1.3 | ||||

| Reading Spanish | 4.7b | 1.9 | 5.5d | 2.3 | ||||

Self-ratings were based on a 7-point scale: 1 (almost none), 2 (very poor), 3 (fair), 4 (functional), 5 (good), 6 (very good), 7 (like native speaker)

n = 15 due to missing language history questionnaire data.

n = 6 due to missing language history questionnaire data.

n = 8 due to missing language history questionnaire data.

Demographic characteristics

Multiple independent sample t-tests were conducted to ensure that matching conditions were met (see Table 1). Hispanics who remained cognitively healthy, henceforth “normal controls,” did not differ from non-Hispanic normal controls on age, gender, and education (all ps ≥ .26). Further analyses comparing non-Hispanic controls with non-Hispanic decliners revealed that controls did not differ from decliners on age, gender, or education (all ps ≥ .60). A comparison of Hispanic controls with Hispanic decliners also yielded no significant effects on all demographic variables (all ps ≥ .66), except for gender, in which all decliners were female (χ2[1, n = 38] = 5.12, p = .02; Fisher’s exact test, p = .03). We address this possible limitation later. Non-Hispanic decliners did not differ from Hispanic decliners in age or education (all ps ≥ .57), but did differ on gender (χ2[1, n = 22] = 3.67, p = .06; Fisher’s exact test, p = .15). Although non-Hispanics might potentially represent a heterogeneous group, all non-Hispanics included in our sample were Caucasian, with the exception of one decliner who was African American.

Language proficiency

A majority of Hispanic participants at the ADRC are bilingual with varying degrees of proficiency in each of their two languages. Of Hispanic decliners, five were born in the United States, four in Mexico, one in Argentina, and one was born in Poland but immigrated to Mexico at age 5. Of matched Hispanic controls, 19 were born in the United States, six in Mexico, one in Colombia, and one in Chile. All Hispanics at the ADRC are tested in their self-reported dominant language during annual neuropsychological evaluations. Similar proportions of decliners (64%) and nondecliners (59%) preferred to be tested in English (and the rest preferred to be tested in Spanish). Qualitatively, there appeared to be a relationship between country of origin (e.g., United States, Mexico, or other Spanish-speaking country) and language in which the participants preferred to be tested. Of all participants tested (combining decliners and controls), 71% preferred to be tested in the dominant language of their country of origin. Detailed information (see Table 1) on language background was available for eight of the 11 Hispanic decliners, and for a subset of the Hispanics who remained cognitively healthy (15 of 27 controls). For these individuals, those born in a Spanish-speaking country were exposed to English, on average, at age 20.14; this is in contrast to participants born in the United States (M = 3.14). We excluded Hispanics who reported a third proficient language, and the level of bilingualism in the non-Hispanic cohort is negligible.

Vascular risk factors

Hispanics have been shown to have greater risk of stroke compared with non-Hispanics (e.g., Sacco et al., 1998; Sacco, Hauser, & Mohr, 1991). Thus, it was important for the purposes of our study to consider this potential confound, given that strokes and vascular dementia affect test performance differently than AD (e.g., Looi & Sachdev, 1999). To address this potential confound, we compared baseline Hachinski ischemia scores, a measure of stroke risk, across the Hispanic and non-Hispanic decliner groups. Although we did not have Year 1 scores for three decliners (two non-Hispanics and one Hispanic), these individuals obtained scores of 0 in subsequent years of testing (Years 2, 4, and 9). We found no difference in stroke risk between the two decliner groups (p = .29). We also assessed for diabetes, given its greater risk in Hispanics (e.g., Harris, 1991), and the relationship between diabetes and dementia (e.g., Ott et al., 1999). Only four individuals had a diabetes diagnosis (two non-Hispanic decliners; two Hispanic normal controls), making diabetes an unlikely confound in our study.

Activities of daily living

Everyday functioning was assessed with the Pfeffer Outpatient Disabilities Scale (PODS; Pfeffer, Kurosaki, Harrah, Chance, & Filos, 1982). Non-Hispanic decliners did not differ from Hispanic decliners on Year 1 PODS scores, nor did decliners differ from controls in either cultural group (all ps ≥ .25). The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR; Hughes, Berg, Danz-inger, Coben, & Martin, 1982; Morris et al., 1991) was adopted by the ADRC relatively recently, and thus only six of 21 decliners with CDR scores had Year 1 CDR scores available. All but one of these six decliners endorsed none of the questions (i.e., obtained global CDR scores of 0), and one received a score of 0.5, which reflects mild forgetfulness but intact functioning and self-care (Hughes et al., 1982). We obtained the earliest CDR available for the remaining 15 decliners, although all of these participants had been in the ADRC for at least 2 years (average of 4.9 years) before they received a CDR score. Despite this delay, average global CDR for both groups was only slightly above 0 (0.36 for Hispanics and 0.35 for non-Hispanics) and did not differ for Hispanic and non-Hispanic decliners (p = .93).

Measures

Neuropsychological tests are administered to participants annually by trained psychometrists at the UCSD ADRC. Psychometrists for the Hispanic cohort were bilingual and bicultural, with most having Mexican American heritage, and some from Central American countries and Puerto Rico. All psychometrists at the ADRC have had BA- or MA-level education at universities in the United States. Here we report data from the first year of ADRC participation (i.e., Year 1) from all tests that were available for all (or most) participants. When necessary, translation of test materials was performed by bilingual psychologists and physicians in consultation with one of the ADRC psychometrists who is a certified translator. Back translation was performed for any tests with materials shown to the participant during testing.

In previous studies, measures most sensitive to future decline included episodic memory assessed with verbal memory tests such as Word List Learning (Chen et al., 2000) and the California Verbal Learning Test (Bondi et al., 1994). Unfortunately, Hispanics who “prefer English” and those who “prefer Spanish” were tested with different verbal memory tests, and therefore we could not include these measures in our analyses. We were, however, able to include a measure of nonverbal episodic memory. The measures included are as follows:

Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975)

The MMSE is a brief, standardized 30-point scale that assesses orientation to time and place, attention and concentration, recall, language, and visual construction.

Dementia Rating Scale (DRS; Mattis, 1988)

The DRS is a standardized 144-point mental status test with subscales for Attention (37 points), Initiation and 1 (39 points), Construction (6 points), Conceptualization (37 points), and Memory (25 points).

Vocabulary Subtest, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised WAIS-R (Wechsler, 1981)

Participants are asked to define 35 words of increasing difficulty. The test is discontinued after five consecutive incorrect responses. Definitions are scored on a 0- to 2-point scale for a total possible score of 70 points.

Digit Symbol Substitution Test, WAIS-R (Wechsler, 1981)

Participants are presented with a key that associates nine unfamiliar symbols with the numbers 1 through 9. They are then asked to use the key to draw the appropriate symbols below a random series of their associated numbers as quickly as possible for 90 s. The number of correctly completed symbols is the score of interest.

Visual Reproduction Test (Wechsler Memory Scale; Russell, 1975, adaptation)

Three figures of increasing complexity are presented to participants for 10 s each. Immediately after each presentation, participants are asked to draw the figure from memory. After 30 min of unrelated testing, participants are again asked to draw the three figures from memory. Immediately after this delayed recall attempt, participants are asked to copy the figures to assess their perceptual and constructional abilities. Three scores are obtained: the sum of scores for all three figures (21 possible points) in the immediate recall, delayed recall, and copy conditions.

Trail Making Test A and B (TMT A and TMT B; from the Halstead Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery; see Reitan, 1958; cf. Mickes et al., 2007)

In Part A (TMT A), participants draw a line to connect the numbers 1 to 25 in consecutive order as quickly as possible within a 150-s time limit. In Part B (TMT B), participants draw a line to connect 25 numbers and letters in alternating, consecutive order as quickly as possible within a 300-s time limit. Time to complete each task is scored.

Boston Naming Test 30-item version (Kaplan, Goodglass, & Weintraub, 1983)

This abbreviated version of the BNT requires the participant to name 30 objects depicted in outline drawings. The drawings are graded in difficulty, with the easiest drawings presented first. If the participant encounters difficulty in naming an object, a stimulus (i.e., semantic) or phonemic cue is provided. Correct responses produced spontaneously and after semantic cues are summed to provide the score of interest for a maximum score of 30.

Verbal Fluency Test (Thurstone & Thurstone, 1941)

In the phonemic fluency task, participants are asked to verbally generate as many different words as possible in 1 min that begin with the letter “F,” then “A,” and then “S.”2 In the semantic fluency task, they are asked to verbally generate as many exemplars as possible in 1 min from the category “animals,” then “fruits,” and then “vegetables.” Scores are based on number of unique words produced, excluding repetitions and variants (e.g., horse, horses).

Modified Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST; Nelson, 1976)

Participants must sort 48 cards into three distinct categories (twice for each category) based on various perceptual features of the cards. The sorting rule in effect changes throughout the test and must be determined by the participant through examiner-provided feedback regarding accuracy of the sort. The number of categories achieved out of six possible categories, and the number of perseverative and nonperseverative errors produced, are scored.

Results and Discussion

The means and standard deviations of neuropsychological test scores of the four groups at Year 1 are shown in Table 2. Because previous studies have shown that bilingualism and differences in culture can affect performance on neuropsychological tests in cognitively healthy individuals, we first compared non-Hispanic and Hispanic normal controls to examine these effects. These initial comparisons are necessary because baseline group differences could impact the sensitivity of cognitive tests to distinguish between controls and those who go on to develop probable AD. We then examined which cognitive tests in Year 1 distinguished decliners from controls in the Hispanic and non-Hispanic groups. After this initial comparison, we then present the remaining results in the following order: (a) tests that did not distinguish between decliners and controls in either group, (b) tests that distinguished between decliners and controls in both groups, (c) tests that distinguished between decliners and controls in Hispanics but not non-Hispanics, and (d) tests that distinguished between decliners and controls in non-Hispanics but not Hispanics. Sample sizes for each analysis differed based on the availability of specific tests for each subject.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations for Participants on all Neuropsychological Measures

| Hispanics |

Non-Hispanics |

Significant differences |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal control |

Decliner |

Normal control |

Decliner |

Normal control Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic |

Normal control vs. decliner |

||||||

| Test name | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | Non-Hispanic | Hispanic | |

| MMSE | 29.3 | (0.9) | 28.9 | (1.6) | 29.0 | (1.2) | 28.7 | (1.3) | |||

| Dementia Rating Scale | |||||||||||

| Total score | 134.8 | (5.1) | 131.6 | (7.6) | 138.3 | (4.2) | 136.2 | (5.1) | ** | ||

| Attention | 35.4 | (1.3) | 34.2 | (1.7) | 36.2 | (1.1) | 36.3 | (0.9) | * | * | |

| Construction | 5.3 | (0.8) | 5.1 | (0.7) | 5.5 | (0.7) | 4.9 | (0.8) | * | ||

| Initiation and Perseveration | 35.3 | (2.3) | 34.1 | (3.1) | 35.6 | (3.0) | 35.2 | (2.1) | |||

| Conceptualization | 34.9 | (3.2) | 35.6 | (3.0) | 36.8 | (2.0) | 36.2 | (3.0) | ** | ||

| Memory | 23.5 | (1.4) | 22.6 | (3.2) | 24.3 | (1.0) | 23.6 | (1.4) | ** | † | † |

| Visual Reproduction | |||||||||||

| Copy | 16.7 | (2.4) | 17.0 | (2.1) | 17.1 | (2.2) | 16.9 | (2.2) | |||

| Immediate | 11.3 | (3.9) | 10.6 | (4.0) | 12.2 | (3.9) | 12.1 | (3.4) | |||

| Delay | 8.2 | (3.4) | 6.9 | (2.8) | 8.3 | (4.8) | 9.8 | (1.3) | |||

| WAIS-R Digit Symbol | 37.3 | (8.8) | 30.8 | (11.0) | 51.9 | (19.2) | 50.3 | (30.4) | ** | † | |

| WAIS-R Vocabulary | 43.6 | (13.2) | 39.1 | (17.5) | 56.2 | (6.3) | 49.9 | (10.9) | ** | * | |

| Trail Making Test A | |||||||||||

| Time to complete | 47.2 | (13.7) | 65.0 | (36.1) | 38.7 | (12.7) | 53.4 | (22.2) | * | ** | * |

| Errors of commission | 0.1 | (0.3) | 0.6 | (1.0) | 0.2 | (0.7) | 0.3 | (0.5) | * | ||

| Trail Making Test B | |||||||||||

| Time to complete | 113.8 | (36.9) | 166.0 | (72.1) | 91.7 | (28.4) | 139.3 | (69.8) | ** | ** | ** |

| Errors of commission | 0.5 | (0.7) | 0.6 | (0.9) | 0.6 | (0.7) | 0.6 | (1.0) | |||

| Boston Naming Test | 26.0 | (2.5) | 23.0 | (3.8) | 27.7 | (2.1) | 25.6 | (3.2) | ** | * | ** |

| Phonemic Fluency | |||||||||||

| Total correct | 34.9 | (12.3) | 32.6 | (12.7) | 40.3 | (12.7) | 37.4 | (8.9) | † | ||

| Letter “F” | 11.4 | (4.1) | 12.3 | (4.9) | 13.7 | (4.4) | 11.8 | (2.6) | * | ||

| Letter “A” | 10.4 | (5.0) | 9.6 | (5.3) | 11.3 | (4.4) | 11.9 | (3.2) | |||

| Letter “S” | 13.0 | (5.2) | 10.7 | (4.0) | 15.3 | (5.4) | 13.6 | (5.4) | † | ||

| Intrusions | 0.8 | (1.0) | 1.0 | (1.5) | 0.4 | (0.7) | 0.6 | (0.8) | * | ||

| Perseveration | 1.4 | (1.2) | 2.2 | (2.7) | 1.3 | (1.3) | 1.7 | (1.6) | |||

| Semantic fluency | |||||||||||

| Total correct | 43.5 | (8.7) | 39.6 | (6.2) | 48.6 | (11.2) | 34.8 | (6.2) | † | ** | |

| Animals | 17.8 | (4.1) | 16.0 | (3.1) | 20.3 | (5.0) | 13.6 | (3.7) | * | ** | |

| Vegetables | 12.3 | (4.0) | 12.7 | (2.5) | 14.4 | (3.8) | 9.6 | (2.0) | * | ** | |

| Fruits | 15.0 | (3.2) | 13.6 | (3.0) | 15.7 | (4.3) | 12.3 | (2.9) | * | ||

| Intrusions | 0.4 | (1.4) | 0.9 | (1.3) | 0.2 | (0.7) | 0.2 | (0.6) | |||

| Perseveration | 1.2 | (1.3) | 1.7 | (1.9) | 1.5 | (2.1) | 0.4 | (0.9) | † | ||

| Wisconsin Card Sorting Test | |||||||||||

| Total categories | 4.8 | (1.7) | 3.8 | (1.8) | 5.2 | (1.3) | 4.6 | (2.0) | |||

| Nonperseverative errors | 6.3 | (4.8) | 13.4 | (8.6) | 7.7 | (4.5) | 9.4 | (9.7) | ** | ||

| Perseverative errors | 7.0 | (12.5) | 6.4 | (7.4) | 2.0 | (3.4) | 3.1 | (6.6) | † | ||

Marginally significant trend towards a difference, p ≤ .10.

Significant difference of p ≤ .05.

Significant difference of p ≤ .01.

Non-Hispanic v. Hispanic Normal Control Group Comparisons

Based on previous studies, we anticipated that Hispanics would obtain lower scores on the MMSE (Bohnstedt, Fox, & Kohatsu, 1994; Mulgrew et al., 1999, but see Hohl, Grundman, Salmon, Thomas, & Thal, 1999), some subscales of the DRS (e.g., Lyness, Hernandez, Chui, & Teng, 2006; Hohl et al., 1999), and, because of their bilingualism, on language measures including semantic fluency (Bialystok et al., 2008; Rosselli et al., 2000), possibly phonemic fluency (e.g., Bialystok et al., 2008; Gollan et al., 2002), and the BNT (Gollan, Fenema-Notestine, Montoya, & Jernigan, 2007; Kohnert, Hernandez, & Bates, 1998; Roberts et al., 2002; Gollan, Weissberger, Runnqvist, Montoya, & Cera, 2012). We also expected WAIS–R Vocabulary and Digit Symbol Substitution subtest scores to be lower in Hispanics, based on reported lower full scale IQ scores for college-aged Mexican Americans than for matched non-Hispanic Caucasians (Verney, Granholm, Marshall, Malcarne, & Saccuzzo, 2005).

Our predictions for tests of executive function were less clear. Although the Trail-Making Test sometimes reveals bilingual advantages (e.g., Bialystok, 2010), some have argued that the test is culturally biased because of the required familiarity with English letters. In one study, a version of the test that was meant to be culture neutral (i.e., the Color Trails Test; Maj et al., 1993) nevertheless revealed differences between cultural groups (i.e., lower scores for older cognitively normal Hispanics than for non-Hispanics; La Rue, Romero, Ortiz, Liang, & Lindeman, 1999). Another test of executive functioning, the WCST, may be culturally fair in cognitively normal Hispanic adults (Proctor & Zhang, 2008; Rey, Feldman, Rivas-Vasquez, Levin, & Benton, 1999), but one study reported that increased mainstream acculturation in Mexican American adults improved performance on this test (Coffey, Marmol, Schock, & Adams, 2005). Given these discrepant findings, either culture- or bilingual-related advantages or disadvantages seemed possible for our participants.

We conducted a series of one-way ANOVAs to compare the Hispanic (n = 27) and non-Hispanic (n = 33) normal control groups on the various cognitive tests. Confirming our predictions, Hispanics obtained lower scores relative to non-Hispanic normal controls on all language tests. As previously reported for bilinguals versus monolinguals (e.g., Roberts et al., 2002), Hispanics (many of whom were bilingual) scored significantly lower than non-Hispanics (who were almost exclusively monolingual) on the BNT, F(1, 58) = 8.05, MSE = 5.27, p = .006, . In addition, Hispanics scored significantly lower on the Vocabulary subtest of the WAIS-R, F(1, 51) = 19.09, MSE = 108. 82, p < .001, . Hispanic controls also produced fewer correct responses than non-Hispanics on the phonemic fluency task (combining scores on letters “F,” “A,” and “S”), although—replicating prior studies which revealed weaker (Gollan et al., 2002) or no disadvantage for bilinguals on letter relative to semantic fluency (Rosselli et al., 2000)—this difference was not significant overall,3 F(1, 58) = 2.85, MSE = 156.70,p = .10, . Hispanics did produce significantly more intrusion errors than non-Hispanics on the letter fluency test, F(1, 58) = 4.01, MSE = .75, p = .05, . A similar general pattern of results emerged for semantic fluency. Hispanic controls also tended to produce fewer correct responses than non-Hispanics on the semantic fluency task (combining scores on “animals,” “fruits,” and “vegetables”), a marginally significant difference overall, F(1, 58) = 3.82, MSE = 103.42, p = .06, . Looking at animals (likely the most commonly administered semantic category), the Hispanic disadvantage was significant (see also Gollan et al., 2002; Rosselli et al., 2000; F[1, 58] = 4.35, MSE = 21.26, p = .04, ; vegetables also produced a significant difference, p = .04, but fruits did not, p = .47). Hispanic and non-Hispanic controls did not differ on the number of intrusion errors produced on the semantic fluency categories (F < 1).

Consistent with the results of Verney et al. (2005), Hispanic controls obtained lower scores than non-Hispanic controls on the WAIS-R Digit Symbol Substitution, F(1, 56) = 13.07, MSE = 234.48, p = .001, . We found no difference in the MMSE scores of Hispanic and non-Hispanic controls (p = .23; see also Hohl et al., 1999), but Hispanic controls obtained lower total DRS scores than non-Hispanics, F(1, 55) = 7.91, MSE = 21.86, p = .007, . In particular, they had significantly lower scores on the Attention, F(1, 55) = 5.04, MSE = 1.47, p = .029, , Conceptualization, F(1, 55) = 7.37, MSE = 6.80, p = .009, , and Memory, F(1, 55) = 6.98, MSE = 136, p = .01, , subtests. These results are consistent with a study by Lyness and colleagues (2006) that showed lower scores in cognitively normal Hispanics compared with non-Hispanics on these same DRS subtests. Even though a large component of the DRS Initiation and Perseveration subtest involves supermarket fluency, there was no difference between Hispanic and non-Hispanic controls on this subtest, perhaps because scoring procedures impose a hard ceiling on the number of items credited.

On tests of visuospatial function and executive function, respectively, Hispanic controls were significantly slower than non-Hispanics on TMT-A, F(1, 58) = 6.19, MSE = 172.92, p = .02, , and TMT-B, F(1, 57) = 6.77, MSE = 1049.33,p = .012, . This is consistent with the results of La Rue et al. (1999) using the Color Trails Test, but not with the advantage found in bilingual children (e.g., Bialystok, 2010). The Hispanic and non-Hispanic controls did not differ in the number of categories sorted on the modified WCST, but Hispanic controls made marginally more perseverative errors than did non-Hispanics, F(1, 50) = 3.80, MSE = 84.18, p = .06, .

Taken together, our results revealed consistently lower scores for Hispanic normal controls relative to age-, education-, and gendermatched non-Hispanic controls on tests of language, executive function, and global cognitive ability. This discrepancy in performance is evident, even though the controls in the present study were longitudinally followed for a number of years to ensure that individuals with preclinical or prodromal AD (or other neurodegenerative conditions) were not included in the Hispanic or non-Hispanic group. Whether the discrepancy in performance between groups is related to culture (such as test bias), bilingualism, or other demographic differences (e.g., socioeconomic status), or a combination of these factors, remains unclear. Having found several significant baseline group differences in performance, we next considered the possible impact of these differences on the utility of cognitive tests for distinguishing between Hispanics with preclinical or prodromal AD (i.e., decliners) from those who remained cognitively normal.

Sensitivity of Measures to Eventual Progression to AD

Based on previous literature, we predicted that tests of global functioning (e.g., MMSE, DRS) and the WCST would be insensitive to future decline (e.g., Bondi et al., 1994; for review, see Twamley et al., 2006). The utility of phonemic fluency and visual memory for detecting preclinical AD is mixed (see Twamley et al.), so we made no specific predictions regarding those tests. Although previous studies have shown that certain tests of episodic memory, semantic memory, and attention are sensitive to preclinical AD in non-Hispanics (for review, see Twamley et al.), we were hesitant to predict that such tests would be sensitive in Hispanics, given the significant differences we observed between Hispanic and non-Hispanic controls (see Table 2). Tests on which Hispanic controls obtained lower scores may have underestimated performance in this group, or could be culturally biased, and for this reason may be less sensitive to small changes in cognitive status.

Tests not sensitive to progression to AD in either group

As predicted, the MMSE (ps ≥ .34), the DRS Conceptualization subscale (ps ≥ .47), the DRS Initiation and Perseveration (ps ≥ .18) subscales, and the number of categories sorted (ps ≥ .13) and perseverative errors (ps ≥ .53) on the WCST were not significantly different between decliners and controls in either cultural group. Tests of visual memory were also insensitive to future decline for both groups: VR immediate recall (ps ≥ .60), VR delayed recall (ps > .28), and VR copy (ps ≥ .76). This finding is consistent with a number of previous studies. Twamley et al. (2006) reported that only 28% of studies reviewed found that tests of visual memory were sensitive to future decline. Total score on the phonemic fluency task (ps ≥ .48), and all of the letters “F,” “A,” and “S” (all ps ≥ .19), were insensitive to eventual progression to AD for both Hispanics and non-Hispanics. The numbers of intrusions and perseveration errors on the phonemic fluency task (all ps ≥ .21) were also insensitive to future decline in both groups. Similarly, the number of intrusion errors produced in semantic fluency were not sensitive to future decline in either group (allps ≥ .31), even though semantic fluency scores were not sensitive to decline in Hispanics as they were for non-Hispanics (see “Tests sensitive to progression to AD in non-Hispanics but not Hispanics”).

Tests sensitive to progression to AD in both groups

Given the paucity of research in this area, we made limited predictions. Despite the robust bilingual disadvantages in picture-naming reported in the literature, and the significantly lower scores for Hispanic relative to non-Hispanic controls on the BNT (in the current study), the BNT was sensitive to progression to AD in both Hispanics, F(1, 36) = 8.19, MSE = 8.81, p = .007, , and non-Hispanics, F(1, 41) = 6.27, MSE = 5.54, p = .02, . Similarly, times to complete TMT-A and TMT-B were sensitive to eventual progression to AD in both Hispanics, F(1, 36) = 4.99, MSE = 497.56, p = .03, , and F(1, 35) = 8.74, MSE = 2456.10, p = .006, , for TMT-A and TMT-B, respectively, and non-Hispanics, F(1, 42) = 7.42, MSE = 239.27, p = .009, , and F(1, 42) = 10.53, MSE = 1775.56, p = .002, , for TMT-A and TMT-B, respectively, even though cognitively healthy Hispanics required significantly more time to complete the TMT-A and TMT-B tests than cognitively healthy non-Hispanics.

Tests sensitive to progression to AD in Hispanics but not non-Hispanics

Cognitive measures that were sensitive to eventual progression to AD exclusively in Hispanics were limited to error scores, with the possible exception of the Digit Symbol Substitution subtest of the WAIS-R, which was marginally sensitive to future decline in Hispanics,4 F(1, 36) = 3.64, MSE = 90.15, p = .06, , compared with non-Hispanics, in which it was not sensitive to future decline (p = .84). Hispanic decliners made significantly more errors on TMT-A, F(1, 36) = 5.88, MSE = .37, p = .02, , TMT-B, F(1, 35) = 4.29, MSE = 5.38, p = .05, , and nonperseverative errors on the WCST, F(1, 34) = 9.96, MSE = 36.47, p = .003, , than did Hispanic normal controls (ps ≥ .50).

Tests sensitive to progression to AD in non-Hispanics but not Hispanics

Contrary to our prediction that tests of global cognition would not be sensitive to decline, non-Hispanic normal controls scored significantly higher on the DRS construction subtest, F(1, 39) = 4.79, MSE = .52, p = .04, , and marginally higher on the DRS memory subtest, F(1, 39) = 2.95, MSE = 1.2, p = .09, , than non-Hispanic decliners. This was not found in the Hispanic group (ps ≥ .25).

Consistent with our prediction that verbal tests might be less sensitive to eventual progression to AD in Hispanic than in non-Hispanic participants, the WAIS-R Vocabulary subtest was not sensitive to future decline in the Hispanic group (p = .40) but was sensitive to decline in the non-Hispanic group, F(1, 32) = 4.21, MSE = 57.32, p = .05, 12 (for similar findings, see Powell et al., 2006). Semantic fluency score was not sensitive to future decline in Hispanics (p = .19) but was sensitive to decline in non-Hispanics, F(1, 42) = 15.04, MSE = 104.75, p<.001, . Although none of the differences between Hispanic normal controls and Hispanic decliners approached significance across all three semantic fluency categories (i.e., animals, vegetables, and fruits; all ps ≥ .20), non-Hispanic controls scored significantly higher than non-Hispanic decliners on all three semantic fluency categories (all ps ≤ .02).

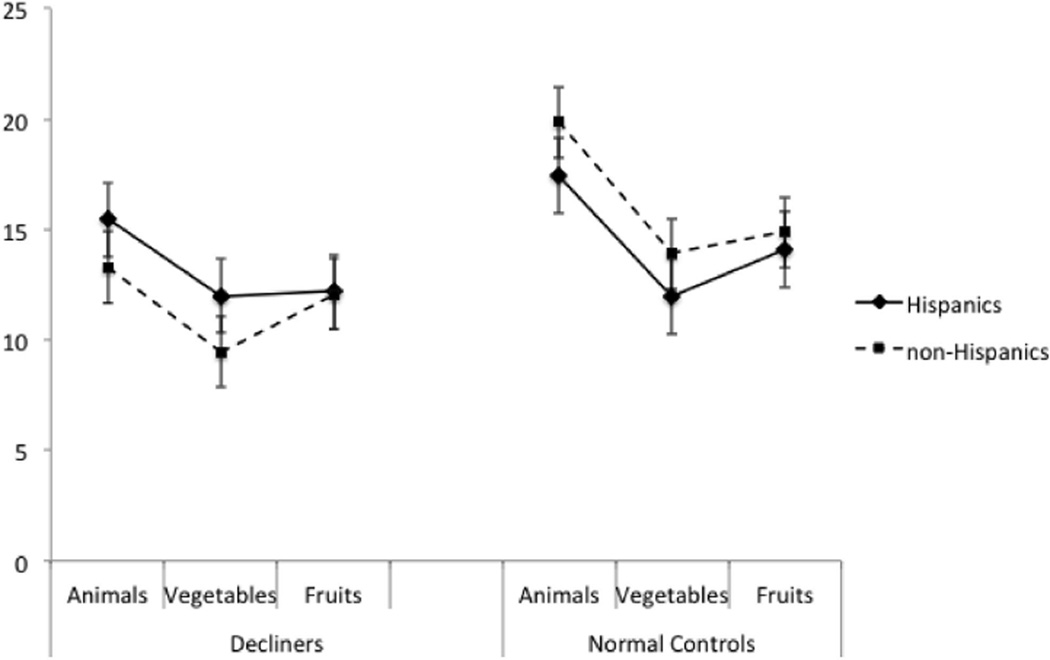

Of interest, Hispanic decliners produced significantly higher semantic fluency scores overall (collapsing all three fluency categories) than non-Hispanic decliners (p = .02). This result stands out in contrast to the otherwise consistently lower scores that cognitively healthy Hispanics had in semantic fluency (e.g., as reported here and in previous studies; e.g., Gollan et al., 2002; Portocarrero et al., 2007; Rosselli et al., 2000), and in many other measures in the current study. To further explore this apparent reversal of the disadvantage with pending onset of AD, we conducted a series of 2 (normal controls vs. decliners) × 2 (Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic) ANOVAs with total semantic fluency scores, and with each of the individual subcategories (animals, fruits, and vegetables), as dependent variables. These analyses confirmed the presence of a significant crossover interaction effect: In those who remained cognitively normal, Hispanics produced fewer correct semantic fluency responses than non-Hispanics, whereas in those who later developed AD, Hispanics produced more correct responses than non-Hispanics (see Figure 1). This interaction was significant for total semantic fluency scores, F(1, 78) = 4.60, MSE = 399.19, p = .04, , and for animals, F(1, 78) = 4.38, MSE = 84.41,p = .04, , and vegetables, F(1, 78) = 6.63, MSE = 80.97, p = .01, , categories, but not for the fruits category (p = .60). These results suggest that semantic fluency scores remain stable in Hispanics for a longer period of time prior to clinical presentation of AD.

Figure 1.

Cross-over interaction for semantic fluency total score and subcategories.

General Discussion

The goal of this study was to determine which neuropsychological tests are sensitive to preclinical AD and future cognitive decline in elderly Hispanic adults. Our prediction was that tests sensitive to future decline in monolingual non-Hispanics might not be sensitive to future decline in Hispanics because of cultural and linguistic differences that could affect test performance. Possible effects of these factors in our participants were initially assessed by comparing cognitively healthy Hispanics with non-Hispanics, and these comparisons revealed a number of significant differences in test performance between cultural groups. Despite these differences, the results only partially confirmed our predictions, with some notable exceptions that have clinical implications in terms of the diagnostic utility of neuropsychological tests for identifying cognitive changes cross-culturally. In addition, the results may shed light on the nature of cognitive changes in preclinical AD.

Looking first at participants who remained cognitively healthy for years after initial testing (i.e., “robust” normal controls), Hispanics obtained significantly lower scores relative to age- and education-matched non-Hispanics on a number of verbal measures including the BNT, the Vocabulary subtest from the WAIS-R, and with trends in this direction for semantic and letter fluency (and significant differences for animals, vegetables, and letter “F”). Hispanic controls also obtained lower scores than non-Hispanic controls on a number of nonverbal (or at least less verbally dependent) measures, including the WAIS-R Digit Symbol Substitution test and several subscales of the DRS (Attention, Conceptualization, and Memory). These lower scores in Hispanic participants on these tests is consistent with previous reports and could be related to bilingualism, cultural bias, unidentified differences in socioeconomic status (SES) between the Hispanics and non-Hispanics, differences in the quality of education between the groups, or some combination of these or other factors.

A number of measures were not sensitive to future cognitive decline in Hispanics or non-Hispanics. These included brief measures of mental status (MMSE, several DRS subscales), some measures of executive function (categories sorted on the WCST, phonemic fluency), and a nonverbal measure of episodic memory (Visual Reproduction Test). The lack of sensitivity to preclinical AD for these measures (at least in the non-Hispanic group) is generally consistent with previous reports (see review in Twamley et al., 2006). It was somewhat surprising that our only measure of delayed recall, the Visual Reproduction Test, lacked sensitivity to preclinical AD. Previous studies showed that tests of delayed recall predict future cognitive decline, but these studies have typically used sensitive tests of verbal episodic memory (Twamley et al., 2006). Additional power may be needed to detect relatively subtle changes in visual memory if they occur in preclinical AD.

A primary goal of the present study was to identify whether cognitive tests that are sensitive to preclinical AD in non-Hispanics would also be sensitive in Hispanics. Contrary to our prediction, a number of tests seemed to predict future cognitive decline in both cultural groups. A few measures emerged as uniquely sensitive for detecting preclinical AD in Hispanic but not in non-Hispanic participants (e.g., the production of errors in TMT A, TMT B, and the WCST). It is not clear why these measures should be uniquely sensitive in one cultural group more than the other, but if replicated in future work, this might provide useful information for early diagnosis of AD in Hispanics. In addition, a number of other measures revealed sensitivity to future decline in Hispanics, even though Hispanics were disadvantaged, with medium to large effect sizes, on these measures. For example, the BNT, a picture naming task known to exhibit robust bilingual disadvantages (e.g., Roberts et al., 2002), and which exhibited a large disadvantage for Hispanics in the current study (), was nevertheless sensitive to future cognitive decline in this group. Similarly, the TMT-A and TMT-B were sensitive to future decline in both cultural groups despite lower scores for Hispanic than non-Hispanic normal controls (and medium effect sizes; ). It is not clear why certain cognitive tests are sensitive to future decline in both groups despite robust cultural group effects on performance, but it could suggest that, despite cultural bias, similar constructs are measured cross-culturally by these tests (see Siedlecki et al., 2010). Although it may be tempting to use these measures to predict cognitive decline in Hispanic older adults, we caution against this approach, as it may lead to inappropriate conclusions in other respects. As suggested by Mehta and colleagues (2008), one solution (if available) is to examine longitudinal data that can indicate a person’s degree of cognitive decline independent of population normative data. However, this is only a temporary solution to a larger issue in neuropsychology. The reported findings speak to the importance of considering how demographic differences (e.g., SES), culture, bilingualism, and early AD might interact to affect test performance, with the ultimate goal of producing accurate assessments for individuals of all cultural, demographic, and linguistic backgrounds.

More in line with our prediction, two verbal tests were sensitive to future decline in non-Hispanics but not in Hispanics. Specifically, non-Hispanic decliners had lower vocabulary and semantic fluency scores relative to matched controls, whereas Hispanic decliners and their matched controls performed similarly. Based on a closer examination of the mean scores for these two tests, we speculate that they may be insensitive to future decline in Hispanics for different reasons. Looking at the Vocabulary test, the non-Hispanic controls’ score stands out as being higher than the scores of all other groups (which are all about the same). For Hispanics on this test, the effects of education level and degree of language exposure (due to bilingualism) may override any effects of an underlying disease process. Indeed, vocabulary test scores may be more resistant to decline than other tests (e.g., see Martin & Fedio, 1983, though this cannot explain why this test was sensitive to decline in non-Hispanics). The sensitivity of picture naming across both cultural groups suggests that picture naming may be more strongly affected by AD than vocabulary knowledge (e.g., see Huff, Corkin, & Growdon, 1986). A different pattern of results was observed for the semantic fluency test. Hispanic decliners had significantly higher semantic fluency scores than non- Hispanic decliners—a pattern not seen on any other test we examined. As shown in Figure 1, this interaction between cultural group (Hispanic, non-Hispanic) and cognitive status (decliner, control) was consistent across two (animals and vegetables) of the three semantic categories tested. Although speculative, this pattern could suggest that Hispanics with preclinical AD may be protected from the vulnerability in semantic fluency that characterizes preclinical AD in non-Hispanics. It is not clear why this was not observed for the fruits category, a category that also exhibited the numerically smallest difference of all three categories tested between decliners and controls in the non-Hispanic group. Note that patterns of performance on individual fluency categories (and sensitivity to disease effects) can vary within category type; for example, semantic categories usually (but not in all cases) generate more correct responses than most letter categories (Acevedo et al., 2000; Azuma et al., 1997; Bayles et al., 1989). It is possible that our findings reflect inherent differences between the individual categories, but given the small number of decliners tested, it also seems possible that the results would change with increased power.

A possible explanation for the protective effect for Hispanics with preclinical AD may be related to effects of bilingualism on semantic fluency, and lifelong competition between languages. Cognitively healthy Spanish–English bilinguals exhibit a semantic fluency disadvantage relative to matched monolinguals (Gollan et al., 2002; Portocarrero et al., 2007; Rosselli et al., 2000) that seems to be caused by competition for selection between languages (Sandoval, Gollan Ferreira, & Salmon, 2010). As exemplars from both languages become active, bilinguals are effectively placed in a dual-task scenario in which they have to simultaneously generate semantic category members, verify that exemplars belong to the target language, and inhibit production of nontarget language category members. Similar competition effects present during normal language production may lead bilinguals to develop processing mechanisms that subsequently make them better able to produce exemplars from semantic memory despite changes to the integrity of semantic memory representations (e.g., Salmon & Bondi, 2009). This explanation is tentative but suggests avenues for future research that may ultimately lead to a better understanding of semantic fluency deficits in bilingualism and in AD.

A number of limitations in the current study call for some caution in interpretation of the findings and suggest a need for further investigation. The longitudinal design of the ADRC study requires that test versions not be changed over time; as a result, several of the measures used in the current study have since been updated, and the results would need to be verified with updated versions (e.g., we used the WAIS–R not the WAIS-IV). Another limitation is that we did not have a detailed measure of verbal episodic memory, a cognitive domain that previous work has shown to be particularly sensitive to preclinical AD (e.g., Bondi et al., 1999; Mickes et al., 2007). It will be important in future work to determine if there are cultural or bilingual effects that limit the effectiveness of verbal episodic memory tests in predicting future cognitive decline in elderly Hispanics. A third limitation is that there were more women than men decliners (particularly in the Hispanic group; see Table 1; but note that key results, e.g., the interaction between cultural group and cognitive status in semantic fluency, did not change when analyzed without men). Perhaps the most notable limitation is that we had a very small number of decliners (11 in each cultural group). This was because of our strict requirement that decliners be diagnosed as normal controls (e.g., we excluded MCI) in their first year of testing. Nevertheless, our results confirm the presence of bilingual disadvantages, suggest sensitivity in some, but not all, measures for detecting future decline across cultural groups, and highlight the potential advantages of considering cross-cultural differences in neuropsychological test performance when evaluating cognition in the elderly.

In sum, the results we reported reveal significant differences between cultural groups in sensitivity of tests to future cognitive decline, and contrary to our predictions, some sensitivity of a number of existing test measures to progression to AD in Spanish-and English-speaking Hispanics. These data may help to improve early diagnosis of AD in Hispanics, but in future work it will be important to create tests that can optimally detect cognitive impairment across multiple cultural groups (e.g., see Ivanova, Salmon, & Gollan, 2013). In addition, the results we reported suggest some between-group variability in the pattern of deficits that emerge at the earliest stages of the disease (e.g., the presence or absence of semantic fluency deficits). If replicated (in future studies with a larger numbers of participants), these could reflect some cognitive advantages associated with cultural differences perhaps related to the need to manage two languages in a single cognitive system. In this respect, the current study illustrates how cross-cultural comparisons can shed light on the cognitive mechanisms underlying neuropsychological test performance and the effects of AD on these tests.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by an F31 from NIA awarded to Gali H. Weissberger (AG039177), by R01s from NICHD (HD050287) and NIDCD (R01 DC011492) awarded to Tamar H. Gollan, and by a P50 from NIA (AG005131) to the University of California.

Footnotes

These inclusion criteria were relaxed for two Hispanic decliners. One was diagnosed with mild neurocognitive disorder in Year 1 of testing, but was then reclassified as a normal control for 6 subsequent years, before receiving a diagnosis of probable AD. Analyzing the data with and without this participant did not change the findings. The second was diagnosed as a normal control in Year 1 of testing and with possible AD at Year 2 (only 2 years of testing were available). McKhann et al. (1984) criteria for possible AD state the presence of a dementia syndrome in which there are variations in onset, presentation, or clinical course, or in which there is a second systemic or neurologic disorder that is insufficient to produce dementia. Analyzing the data without this participant slightly changed one finding (see Footnote 4).

Because the ADRC longitudinal study was initiated in 1990, Spanish speakers were also tested with “F,” “A,” and “S,” despite later indications in the literature that the “P,” “M,” and “R” may be preferred when testing in Spanish (see Artiola i Fortuny, Heaton, & Hermosillo, 1998; Peña-Casanova et al., 2009).

Only letter “F” produced a significant difference between Hispanic and non-Hispanic normal controls, F(1,58)= 4.25, MSE=1834, p=.04, ; letters “S” and “A” did not (ps ≥.11). In addition, although Spanish speakers may be better assessed with letters “P,” “M,” and “R” (Artiola et al., 1998; Peña-Casanova et al., 2009), we did not observe significant differences in the present study in total letter fluency scores between Hispanics tested in English versus Spanish on the letters “F,” “A,” and “S,” for normal controls (p = .46) or decliners (p = .13).

Difference between Hispanic normal controls and decliners on Digit Symbol changed from marginally significant to significant when excluding the participant with a diagnosis of possible AD, F(1,35)=4.29, MSE=90.62, p=.05, .

Contributor Information

Gali H. Weissberger, San Diego State University and University of California, San Diego Joint Doctoral Program in Clinical Psychology

David P. Salmon, Department of Neurosciences, University of California, San Diego

Mark W. Bondi, Department of Psychiatry, VA San Diego Healthcare System, San Diego, California, and Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego

Tamar H. Gollan, Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego

References

- Abutalebi J, Green D. Bilingual language production: The neurocognition of language representation and control. Journal of Neurolinguistics. 2007;20:242–275. [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo A, Loewenstein DA, Barker WW, Harwood DG, Luis C, Bravo M, Duara R. Category fluency test: Normative data for English- and Spanish-speaking elderly. Journal of International Neuropsychological Conference. 2000;6:760–769. doi: 10.1017/s1355617700677032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert MS, Moss MB, Tanzi R, Jones K. Preclinical prediction of AD using neuropsychological tests. Journal of International Neuropsychological Society. 2001;7:631–639. doi: 10.1017/s1355617701755105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardila A, Rosselli M, Puente AE. Neuropsychological evaluation of the Spanish speaker. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artiola i, Fortuny L, Garolera M, Hermosillo Romo D, Feldman E, Fernandez Barillas H, Keefe R, Verger Maestre K. Research with Spanish-speaking populations in the United States: Lost in translation a commentary and a plea. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2005;27:555–564. doi: 10.1080/13803390490918282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artiola i, Fortuny L, Heaton RK, Hermosillo D. Neuropsychological comparisons of Spanish-speaking participants from the U.S.– Mexico border region versus Spain. Journal of the International Neu-ropsychological Society. 1998;4:363–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azuma T, Bayles KA, Cruz RF, Tomoeda CK, Wood JA, McGeagh A, Montgomery EB. Comparing the difficulty of letter, semantic, and name fluency tasks for normal elderly and patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neuropsychology. 1997;11:488–497. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.11.4.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäckman L, Small BJ, Fratiglioni L. Stability of the preclinical episodic memory deficit in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain: A Journal of Neurology. 2001;124:96–102. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayles KA, Salmon DP, Tomoeda CK, Jacobs D, Caffrey JT, Kaszniak AW, Troster AI. Semantic and letter category naming in Alzheimer’s patients: A predictable difference. Developmental Neuropsychology. 1989;5:335–347. [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok E. Cognitive complexity and attentional control in the bilingual mind. Child Development. 1999;70:636–644. [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok E. Global-Local and Trail-Making Tasks by monolingual and bilingual children: Beyond inhibition. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:93–105. doi: 10.1037/a0015466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok E, Craik FIM, Green DW, Gollan TH. Bilingual minds. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2009;10:89–129. doi: 10.1177/1529100610387084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok E, Craik FIM, Klein R, Viswanathan M. Bilingualism, aging, and cognitive control: Evidence from the Simon Task. Psychology and Aging. 2004;19:290–303. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.2.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok E, Craik FIM, Luk G. Cognitive control and lexical access in younger and older bilinguals. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2008;34:859–873. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.34.4.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok E, Martin MM. Attention and inhibition in bilingual children: Evidence from the dimensional change card sort task. Developmental Science. 2004;7:325–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2004.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok E, Shapero D. Ambiguous benefits: The effect of bilingualism on reversing ambiguous figures. Developmental Science. 2005;8:595–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2005.00451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnstedt M, Fox PJ, Kohatsu ND. Correlates of Mini-Mental-Status-Examination scores among elderly demented patients: The influence of race-ethnicity. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1994;47:1381–1387. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondi MW, Monsch AU, Galasko D, Butters N, Salmon DP, Delis DC. Preclinical cognitive markers of dementia of the Alzheimer type. Neuropsychology. 1994;8:374–384. [Google Scholar]

- Bondi MW, Salmon DP, Galasko D, Thomas RG, Thal LJ. Neuropsychological function and apolipoprotein E genotype in the preclinical detection of Alzheimer’s disease. Psychology and Aging. 1999;14:295–303. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.14.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butters N, Granholm E, Salmon DP, Grant I, Wolfe J. Episodic and semantic memory: A comparison of amnesic and demented patients. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 1987;9:479–497. doi: 10.1080/01688638708410764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SM, Meltzoff AN. Bilingual experience and executive functioning in young children. Developmental Science. 2008;11:282–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00675.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Ratcliff G, Belle SH, Cauley JA, DeKosky ST, Ganguli M. Cognitive tests that best discriminate between presymptomatic AD and those who remain nondemented. Neurology. 2000;55:1847–1853. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.12.1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Ratcliff G, Belle SH, Cauley JA, DeKosky ST, Ganguli M. Patterns of cognitive decline in presymptomatic Alzheimer’s disease. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:853–858. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark CM, DeCarli C, Mungas D, Chui HI, Higdon R, Nuñez J, van Belle G. Earlier onset of Alzheimer disease symptoms in Latino individuals compared with Anglo individuals. Archives of Neurology. 2005;62:774–778. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.5.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LJ, Gatz M, Zheng L, Chen Y-L, McCleary C, Mack WJ. Longitudinal verbal fluency in normal aging, preclinical, and prevalent Alzheimer disease. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias. 2009;24:461–468. doi: 10.1177/1533317509345154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LR, Schiehser DM, Weissberger GH, Salmon DP, Delis DC, Bondi MW. Specific measures of executive function predict cognitive decline in older adults. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2012;18:118–127. doi: 10.1017/S1355617711001524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey DM, Marmol L, Schock L, Adams W. The influence of acculturation on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test by Mexican Americans. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2005;20:795–803. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosentino S, Scarmeas N, Albert SM, Stern Y. Verbal fluency predicts mortality in Alzheimer’s disease. Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology. 2006;19:123–129. doi: 10.1097/01.wnn.0000213912.87642.3d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa A, Hernández M, Costa-Faidella J, Sebastián-Gallés N. On the bilingual advantage in conflict processing: Now you see it, now you don’t. Cognition. 2009;113:135–149. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa A, Hernández M, Sebastián-Gallés N. Bilingualism aids conflict resolution: Evidence from the ANT task. Cognition. 2008;106:59–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson BC, Sperling RA, Hyman BT, Albert MS, Blacker D. Clinical prediction of Alzheimer disease dementia across the spectrum of mild cognitive impairment. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:1443–1450. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.12.1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duara R, Barker WW, Lopez-Alberola R, Loewenstein DA, Grau LB, Gilchrist D, …St. George-Hyslop PH. Alzheimer’s disease: Interaction of apolipoprotein E genotype, family history of dementia, gender, education, ethnicity, and age of onset. Neurology. 1996;46:1575–1579. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.6.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galasko D, Hansen L, Katzman R, Widerholt W, Masliah E, Terry R, Thal LJ. Clinical-neuropathological correlations in Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Archives of Neurology. 1994;51:888–895. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1994.00540210060013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasquoine PG. Variables moderating cultural and ethnic differences in neuropsychological assessment: The case of Hispanic Americans. Clinical Neuropsychologist. 1999;13:376–383. doi: 10.1076/clin.13.3.376.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollan TH, Fenema-Notestine C, Montoya RI, Jernigan TL. The bilingual effect on Boston Naming Test performance. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2007;13:197–208. doi: 10.1017/S1355617707070038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollan TH, Ferreira VS. Should I stay or should I switch? A cost-benefit analysis of voluntary language switching in young and aging bilinguals. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2009;35:640–665. doi: 10.1037/a0014981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollan TH, Montoya RI, Fennema-Notestine C, Morris SK. Bilingualism affects picture naming but not picture classification. Memory & Cognition. 2005;33:1220–1234. doi: 10.3758/bf03193224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollan TH, Montoya RI, Werner GA. Semantic and letter fluency in Spanish-English bilinguals. Neuropsychology. 2002;16:562–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollan TH, Salmon DP, Montoya RI, Galasko DR. Degree of bilingualism predicts age of diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in low-education but not in highly educated Hispanics. Neuropsycholo-gia. 2011;49:3826–3830. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollan TH, Silverberg NB. Tip-of-the-tongue states in Hebrew-English bilinguals. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2001;4:63–83. [Google Scholar]

- Gollan TH, Weissberger G, Runnqvist E, Montoya RI, Cera CM. Self-ratings of spoken language dominance: A multilingual naming test (MINT) and preliminary norms for young and aging Spanish-English bilinguals. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2012;15:594–615. doi: 10.1017/S1366728911000332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris MI. Epidemiological correlates of NIDDM in Hispanics, Whites, and Blacks in the U.S. population. Diabetes Care. 1991;14:639–648. doi: 10.2337/diacare.14.7.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helzner EP, Scarmeas N, Cosentino S, Tang MX, Schupf N, Stern Y. Survival in Alzheimer’s disease: A multiethnic, population-based study of incident cases. Neurology. 2008;71:1489–1495. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000334278.11022.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry JD, Crawford JR, Phillips LH. Verbal fluency performance in dementia of the Alzheimer’s type: A meta-analysis. Neuropsychologia. 2004;42:1212–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez AE. Language switching in the bilingual brain: What’s next? Brain and Language. 2009;109:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohl U, Grundman M, Salmon DP, Thomas RG, Thal LJ. Mini-Mental State Examination and Mattis Dementia Rating Scale performance differs in Hispanics and non-Hispanic Alzheimer’s disease patients. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 1999;5:301–307. doi: 10.1017/s1355617799544019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howieson DB, Dame A, Camicioli R, Sexton G, Payami H, Kaye J. Cognitive markers preceding Alzheimer’s dementia in healthy oldest old. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1997;45:584–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb03091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huff FJ, Corkin S, Growdon JH. Semantic impairment and anomia in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain and Language. 1986;28:235–249. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(86)90103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes CP, Berg L, Danzinger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1982;140:566–572. doi: 10.1192/bjp.140.6.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Test Commission. International Test Commission Guidelines for Translating and Adapting Tests. 2010 Retrieved from www.intestcom.org/Guidelines/Adapting+Tests.php.

- Ivanova I, Costa A. Does bilingualism hamper lexical access in speech production? Acta Psychologica. 2008;127:277–288. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova I, Salmon DP, Gollan TH. The Multilingual Naming Test in Alzheimer’s disease: Clues to the origin of naming impairments. The Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2013 doi: 10.1017/S1355617712001282. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs DM, Sano M, Dooneief G, Marder K, Bell KL, Stern Y. Neuropsychological detection and characterization of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1995;45:957–962. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.5.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd T, Capetillo D, Carrión-Baralt J, Mármol LM, San Mguel-Montes L, Navarrete MG, Silver CH. Professional considerations for improving the neuropsychological evaluation of Hispanics: A National Academy of Neuropsychology education paper. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2009;24:127–135. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acp016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan E, Goodglass H, Weintraub S. The Boston Naming Test. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Kavé G, Eyal N, Shorek A, Cohen-Mansfield J. Multilin-gualism and cognitive state in the oldest old. Psychology and Aging. 2008;23:70–78. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.23.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohnert KJ, Hernandez AE, Bates E. Bilingual performance on the Boston Naming Test: Preliminary norms in Spanish and English. Brain and Language. 1998;65:422–440. doi: 10.1006/brln.1998.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovács AM. Early bilingualism enhances mechanisms of false-belief reasoning. Developmental Science. 2009;12:48–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovács AM, Mehler J. Cognitive gains in 7-month-old bilingual infants. PNAS Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:6556–6560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811323106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroll JF, Gollan TH. Speech planning in two languages: What bilinguals tell us about language production. In: Ferreira V, Goldrick M, Miozzo M, editors. The Oxford handbook of language production. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon OD, Khaleeq A, Chan W, Pavlik VN, Doody RS. Apolipoprotein E polymorphism and age at onset of Alzheimer’s disease in a quadriethnic sample. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2011;30:486–491. doi: 10.1159/000322368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange KL, Bondi MW, Salmon DP, Galasko D, Delis DC, Thomas RG, Thal LJ. Decline in verbal memory during preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: Examination of the effect of APOE genotype. Journal of International Neuropsychological Society. 2002;8:943–955. doi: 10.1017/s1355617702870096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]