Abstract

Objective

Anorexia nervosa (AN) and bulimia nervosa (BN) are marked by longitudinal symptom fluctuations. DSM-IV-TR does not address how to classify eating disorder (ED) presentations in individuals who no longer meet full criteria for these disorders. To consider this issue, we examined subthreshold presentations in women with initial diagnoses of AN and BN.

Method

A total of 246 women with AN or BN were followed for a median of 9 years; weekly symptom data were collected at frequent intervals using the Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation of Eating Disorders (LIFE-EAT-II). Outcomes were ED presentations that were subthreshold for ≥3 months, including those narrowly missing full criteria for AN or BN, along with binge eating disorder (BED) and purging disorder.

Results

During follow-up, most women (77.6%) experienced a subthreshold presentation. Subthreshold presentation was related to intake diagnosis (Wald χ2 = 8.065, df = 2, p = 0.018). Individuals with AN most often developed subthreshold presentations resembling AN; those with BN were more likely to develop subthreshold BN. Purging disorder was experienced by half of those with BN and one-quarter of those with AN binge/purge type (ANBP); BED occurred in 20% with BN. Transition from AN or BN to most subthreshold types was associated with improved psychosocial functioning (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Subthreshold presentations in women with lifetime AN and BN were common, resembled the initial diagnosis, and were associated with modest improvements in psychosocial functioning. For most with lifetime AN and BN, subthreshold presentations seem to represent part of the course of illness and to fit within the original AN or BN diagnosis.

Keywords: Anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, classification, eating disorder not otherwise specified, longitudinal

Introduction

The validity of DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2000) eating disorder (ED) diagnoses is under review in preparation for DSM-V. DSM-IV-TR includes three EDs, anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN) and ED not otherwise specified (EDNOS), each defined on the basis of current symptoms. AN and BN are defined by specific criteria sets whereas EDNOS is a heterogeneous diagnosis defined by clinically significant ED presentations that ‘do not meet criteria’ for AN or BN (APA, 2000, p. 594). Prototypic examples of EDNOS are presentations that narrowly miss the full criteria for AN or BN, but EDNOS also includes symptom clusters that have been described as binge eating disorder (BED; APA, 2000) or purging disorder (Keel, 2007; Keel & Striegel-Moore, 2009). Research indicating the longitudinal instability of ED symptoms suggests that an individual may meet criteria for AN or BN at one point, and narrowly miss meeting full criteria for that disorder at another point in time (Milos et al. 2005; Tozzi et al. 2005; Eddy et al. 2008; Agras et al. 2009; Anderluh et al. 2009). How best to classify these subthreshold presentations in individuals with lifetime AN or BN (e.g. within the initial diagnosis of AN or BN or as a different disorder such as EDNOS) is not addressed in DSM-IV-TR.

Indeed, the boundaries between the specific EDs (AN and BN) and EDNOS are not clear. The literature suggests that a sizable minority of individuals diagnosed with EDNOS have a history of meeting full criteria for AN or BN, raising questions about the distinctiveness of these groups (Fairburn & Bohn, 2005). Cross-sectional studies generally demonstrate few clinically meaningful differences between individuals with full-syndrome AN or BN and their EDNOS counterparts (e.g. AN compared to EDNOS that resembles AN, or BN compared to EDNOS that resembles BN), although cross-sectional differences between AN and BN, and certain EDNOS types including BED or purging disorder, have been noted, underscoring the heterogeneity of EDNOS (see Thomas et al. 2009).

There is a paucity of longitudinal research on EDNOS. One early study of a small cohort of women with EDNOS found that the majority (82%) either endorsed a history of AN or BN at study intake or developed one of these two disorders during a mean of 40 months of follow-up (Herzog et al. 1993). A more recent prospective study by Milos et al. (2005) examined diagnostic cross-over to and from EDNOS, finding that during a 30-month follow-up, 20.0% of individuals with an initial diagnosis of AN and 26.9% with an initial diagnosis of BN crossed over to EDNOS; in that same time-frame, 13.8% of those with an initial diagnosis of EDNOS crossed over to AN, 3.4% to BN, and 51.7% to recovery. This research demonstrated that even during a short-term follow-up period, cross-over between AN, BN and EDNOS was common, and movement from EDNOS to recovery was likely. A notable study limitation, however, was the lack of descriptive data about the types of EDNOS presentations or change in clinical severity or functioning experienced in these transitions. More recently, Agras et al. (2009) described the 4-year prospective course of EDNOS, operationally defined as excluding BED and narrowly missing criteria for AN, BN or BED (considered a distinct diagnosis in this study). The authors found that most (82%) individuals with EDNOS had a lifetime history of AN, BN or BED, and that EDNOS was often experienced on the path from AN, BN or BED to full recovery. Indeed, compared to AN or BN, time to full recovery was significantly shorter from EDNOS (but not from BED).

The current study was designed to extend the extant research by describing a range of specific subthreshold presentations that emerge during long-term follow-up in women with initial diagnoses of AN and BN. The overarching objective of this line of research was to inform the nosology of EDs in preparation for DSM-V by considering how EDNOS presentations should be classified in women with lifetime AN and BN. Previous research from our group, examining the course of EDs in the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Longitudinal Study of AN and BN, indicated that during follow-up, approximately three-quarters of individuals with lifetime AN or BN experience a period of time during which they remain symptomatic but no longer meet full criteria for AN or BN (Eddy et al. 2008). In this previous paper, the specific symptom presentations experienced during those periods were not examined (Eddy et al. 2008). In the current study, using the uniquely rich MGH Longitudinal Study dataset of individuals with AN and BN who were followed for a median of 9 consecutive years, we build on the previous study by characterizing five specific presentations considered to be subthreshold for AN or BN in women with initial diagnoses of AN restricting (ANR) or AN binge/purge type (ANBP) and BN. We also describe changes in psychosocial functioning associated with movement from full-syndrome AN or BN to any of the subthreshold presentations in order to understand the clinical significance of these transitions. We hypothesized that subthreshold presentations experienced would symptomatically resemble the initial ED diagnoses, and that these transitions would be associated with improved functioning.

Method

Participants

Two hundred and ninety-four treatment-seeking women were recruited for participation in the MGH Longitudinal Study of AN and BN between 1987 and 1991; after complete description of the study, 246 (84%) women provided written consent to participate. At intake, all subjects met DSM-III-R criteria for AN, BN or both AN and BN; participants were reclassified according to DSM-IV-TR criteria as 136 with AN (51 with ANR and 85 with ANBP) and 110 with BN. At study entry, the mean age of the sample was 24.8 years (S.D.=6.7 years), with a mean duration of illness of 6.7 years (S.D.=6.1 years). Four per cent of the sample were non-Caucasian. More complete demographic data and study methods have been presented elsewhere (Herzog et al. 1999).

Procedure

Participants were interviewed every 6–12 months by trained assessors. Initial assessments were conducted in person. Follow-up interviews were conducted in person whenever possible, although the majority (approximately 90%) were conducted by telephone. Participants were paid for the initial and each follow-up assessment. The mean and the median duration of follow-up were 8.6 and 9.0 years respectively; attrition was 7.0%. There were no differences between those who remained in the study and those who discontinued participation.

Instruments

The Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation of Eating Disorders (LIFE-EAT-II; Keller et al. 1987) was used to assess symptoms at intake and throughout the follow-up period; it was administered by trained interviewers every 6 months. At each interview, participants were prompted to generate anchors to aid in remembering the events of the past 6 months and weekly symptoms (and changes) were assessed and recorded through retrospective recall. The LIFE-EAT-II yields weekly ED symptom data that allowed DSM-IV-TR diagnoses to be assigned throughout follow-up (i.e. recomputed for each 13-week interval throughout the study) using symptom scores for the current week and the preceding 12 weeks (i.e. 3-month period in accordance with the DSM-IV-TR duration criterion). ANR, ANBP and BN were defined by DSM-IV-TR criteria.

Five subthreshold ED presentations were examined and are defined in Table 1 using criteria guidelines from DSM-IV-TR for EDNOS.† ED recovery was defined by minimal to no symptoms (i.e. failure to be classified as AN, BN or any of the subthreshold presentations) during 13 consecutive weeks.

Table 1.

Definitions of subthreshold eating disorder (ED) presentation types

| Subthreshold presentation | 3-month criteria |

|---|---|

| Sub-ANR | Narrowly misses DSM-IV criteria for ANR: 86–90% IBW, irrespective of menstrual status; binge/purge behaviors ≤1×/month |

| Sub-ANBP | Narrowly misses DSM-IV criteria for ANBP: 86–90% IBW; irrespective of menstrual status; binge/purge behaviors >1×/month; does not have BN |

| Sub-BN | Narrowly misses DSM-IV criteria for BN: >90% IBW; binge/purge behaviors 2–7×/month |

| Purging disorder | Purging without binge eating: >90% IBW; purging ≥4×/month; binge eating ≤1×/month |

| Binge eating disorder | Binge eating without purging: >90% IBW; binge eating ≥8×/month; purging ≤1×/month |

Sub-ANR, Subthreshold restricting anorexia nervosa; Sub-ANBP, subthreshold binge/purge anorexia nervosa; Sub-BN, subthreshold bulimia nervosa; IBW, ideal body weight.

Purging disorder was defined using the criteria recommended by Keel & Striegel-Moore (2009).

Psychosocial functioning was assessed longitudinally using the Range of Impaired Function Tool (LIFE-RIFT; Keller et al. 1987), a semi-structured interview that measures occupational, interpersonal and recreational functioning, and satisfaction or subjective quality of life. In each domain, scores range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating poorer functioning; scores ≥2 reflect impaired functioning. For the purposes of these analyses, we considered the composite psychosocial functioning score, which ranges from 4 (no impairment, high functioning) to 20 (severe impairment).‡ The LIFE-RIFT has demonstrated good reliability, concurrent validity and predictive validity (Leon et al. 1999, 2000).

Training

Assessors were trained through a five-step program modeled after the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Collaborative Psychobiology of Depression Study. First, interviewers learned Research and Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) and DSM categories. Second, they practiced interviews on non-patient volunteers and trained interviewers who engaged in role-play. Third, they observed and scored training tapes of expert interviewers to resolve deviations from expert ratings. Fourth, they observed actual interviews. Fifth, they were observed by a senior interviewer while conducting study interviews. Ongoing supervision by a senior interviewer was available throughout the study and a semi-annual monitoring and re-certification program was conducted to ensure high inter-rater reliability. Interviewers demonstrated high reliability with 88% agreement and 0.93 intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) for AN and 90% agreement and 0.94 ICC for BN.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses of the transitions were completed in R (R Development Core Team, 2007). Frequencies of overall transitions to subthreshold presentations and transitions to specific subthreshold states were compared by intake diagnosis. These frequencies were supplemented by figures depicting the patterns of diagnoses in this sample to aid in the interpretation of the transitions. A generalized estimating equations (GEE) model with multinomial logistic response function evaluated the relationship between baseline diagnosis and subsequent subthreshold diagnostic presentations; duration of follow-up was included as a covariate in these analyses.

We used first-order Markov modeling to estimate the transition probability between states for any given 3-month period by intake diagnosis. This modeling assumes that the probability of transitioning is a stationary process; that is, that the probabilities do not change over time. Notably, we also ran the transition analyses separately for the early (years 1–4), middle (years 5–8) and late (years 9–12) transition matrices, which were similar to those presented here. These separate matrices are available upon request to the authors.

Mixed-effects linear models were used to compare mean psychosocial scores during periods with the intake diagnosis to psychosocial scores during periods of subthreshold presentations or no diagnosis. These models included the follow-up assessment point as a covariate. Separate analyses were performed for each intake diagnosis (i.e. ANR, ANBP, BN). Pair-wise comparisons between mean scores were based upon an α of p<0.01 for intake ANR and ANBP (four and five comparisons respectively) and p <0.008 for intake BN (six comparisons). The number of comparisons for each intake diagnosis was based on the frequency of occurrence of specific transitions (i.e. pair-wise comparisons were not made for infrequent transitions), and this number of comparisons was used to determine the significance level.

Results

During the course of follow-up, 77.6% (n = 191) of the sample experienced a period of ≥ 3 months in which subjects endorsed symptoms that were subthreshold for AN or BN. This included 64.7% (n = 33) of those with an intake diagnosis of ANR, 67.1% (n=57) of those with an intake diagnosis of ANBP, and 91.8% (n = 101) of those with an intake diagnosis of BN. Individuals with BN were more likely than those with AN to experience a subthreshold presentation during follow-up, controlling for duration of follow-up (Wald χ2=6.807, df=1, p=0.009). Furthermore, there were between-group differences in the likelihood of developing specific subthreshold presentations (Wald χ2=8.065, df=2, p=0.018), described below. Duration of follow-up did not contribute significantly to the model (Wald χ2=0.151, df=1, p=0.698).

Transition to specific subthreshold presentations

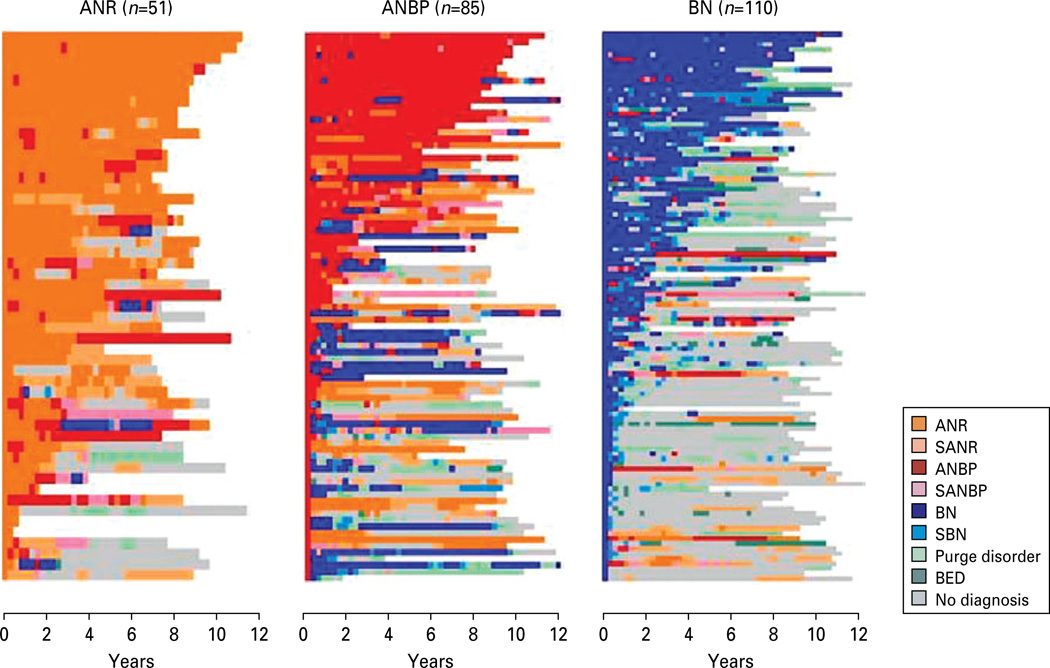

Fig. 1 depicts the longitudinal course transitions for women with intake diagnoses of ANR, ANBP and BN to the range of subthreshold presentations. Women with intake ANR were most likely to develop sub-threshold ANR (54.9%, n=28), followed by subthreshold ANBP (21.6%, n=11). The mean and median duration of these subthreshold episodes for women with intake ANR was 12.0 and 6.8 months respectively for subthreshold ANR (range 3–48 months), and 11.3 and 6.0 months respectively for subthreshold ANBP (range 3–60 months). Transitions from intake ANR to subthreshold BN (3.9%, n=2), purging disorder (5.9%, n=3) and BED (2.0%, n=1) were uncommon. During follow-up, 45.1% (n=23) with intake ANR developed exactly one subthreshold diagnosis, 15.7% (n=8) developed exactly two subthreshold diagnoses, and 3.9% (n=2) developed exactly three subthreshold diagnoses; none developed more than three. Among those women with ANR who developed a subthreshold diagnosis during follow-up, 45.5% (n=15) experienced a subthreshold diagnosis that persisted for ≥12 months.

Fig. 1.

Longitudinal emergence of specific subthreshold presentations in women with initial diagnoses of anorexia nervosa (AN) restricting type (ANR), AN binge/purge type (ANBP) and bulimia nervosa (BN). SANR, subthreshold ANR; SANBP, subthreshold ANBP; SBN, subthreshold BN; BED, binge eating disorder. Each row depicts the course for one participant.

For women with an intake diagnosis of ANBP, transitions to subthreshold ANR (40.0%, n=34) or subthreshold ANBP (35.3%, n=30) were most common, followed by transitions to subthreshold BN (23.5%, n=20) and purging disorder (23.5%, n=20); transition to BED was uncommon (9.4%, n=8). Among women with intake ANBP, the mean and median duration of these subthreshold episodes was respectively 9.6 and 6.6 months for subthreshold ANR (range 3–51 months), 6.5 and 4.5 months for subthreshold ANBP (range 3–54 months), 4.6 and 3.5 months for subthreshold BN (range 3–24 months), and 10.5 and 6.9 months for purging disorder (range 3–75 months). During follow-up, 22.3% (n=19) with intake ANBP developed one subthreshold diagnosis, 27.1% (n=23) developed exactly two subthreshold diagnoses, 15.3% (n=13) developed exactly three sub-threshold diagnoses, and 2.4% (n=2) developed exactly four subthreshold diagnoses; none developed more than four. Among those women with ANBP who developed a subthreshold diagnosis during follow-up, 47.4% (n=27) experienced a subthreshold diagnosis that persisted for ≥12 months

For women with an intake diagnosis of BN, transition to subthreshold BN was most common (68.2%, n=75), followed by transition to purging disorder (50.9%, n=56). Transition to subthreshold ANR (23.6%, n=26), BED (20.0%, n=22) and subthreshold ANBP (17.3%, n=19) also occurred. Among women with intake BN, the mean and median duration of these subthreshold episodes was respectively 3.8 and 3.0 months for subthreshold BN (range 3–45 months), 12.5 and 6.6 months for purging disorder (range 3–81 months), 12.1 and 9.0 months for subthreshold ANR (range 3–51 months), 10.9 and 6.8 months for BED (range 3–51 months), and 5.9 and 4.2 months for sub-threshold ANBP (range 3–51 months). During follow-up, 29.1% (n=32) with intake BN developed exactly one subthreshold diagnosis, 42.7% (n=47) developed exactly two subthreshold diagnoses, 14.5% (n=16) developed exactly three subthreshold diagnoses, and 5.5% (n=6) developed exactly four subthreshold diagnoses; none developed more than four. Among those women with BN who developed a subthreshold diagnosis during follow-up, 39.6% (n=40) experienced a subthreshold diagnosis that persisted for ≥12 months.

Transition analyses

Transition analyses demonstrated that, during any given 3-month period of follow-up, the likelihood of remaining stable within a given diagnosis was greater than that of transitioning (see Table 2). The matrices showed that when transitions occurred, full-syndrome disorders tended to move to subthreshold presentations (45% of transitions from full-syndrome disorders were to subthreshold) or to different full-syndrome disorders (42% were to different full-syndrome disorders), and rarely (13%) directly to recovery. Subthreshold presentations either returned to full-syndrome diagnoses (36%) or moved to recovery (41%). The subthreshold presentations were more likely than the full-criteria disorders to precede recovery, with the exception of subthreshold ANBP, which rarely directly preceded recovery (≤5% probability). From recovery, individuals most frequently transitioned to subthreshold presentations (82%) rather than to full-syndrome disorders (18%). Finally, these analyses also highlight the improbability of certain transitions during any given 3-month period (e.g. ANR never transitioned directly to BN, subthreshold BN, purging disorder or BED).

Table 2.

Transition matrix: probability of transitioning during any 3-month interval for initial diagnosis ANR, ANBP and BN

| Time 1 | Time 2 |

Observed row-wise frequencies |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANR | ANBP | BN | Sub-ANR | Sub-ANBP | Sub-BN | Purging disorder |

BED | No Dx (recovered) |

||

| ANR | 0.91/0.84/0.74 | 0.04/0.08/0.09 | 0.00/0.00/0.00 | 0.04/0.06/0.10 | 0.00/0.01/0.03 | 0.00/0.00/0.00 | 0.00/0.00/0.00 | 0.00/0.00/0.00 | 0.01/0.02/0.04 | 891/454/68 |

| ANBP | 0.15/0.06/0.04 | 0.75/0.85/0.74 | 0.04/0.06/0.11 | 0.01/0.00/0.01 | 0.04/0.02/0.06 | 0.00/0.00/0.01 | 0.00/0.00/0.01 | 0.00/0.00/0.00 | 0.01/0.01/0.01 | 173/939/157 |

| BN | 0.00/0.00/0.00 | 0.11/05/0.02 | 0.74/0.83/0.80 | 0.00/0.01/0.00 | 0.05/0.03/0.01 | 0.03/0.04/0.08 | 0.00/0.02/0.02 | 0.03/0.01/0.01 | 0.05/0.02/0.05 | 38/484/1106 |

| Sub-ANR | 0.12/0.07/0.04 | 0.01/0.01/0.01 | 0.01/0.01/0.01 | 0.73/0.72/0.80 | 0.02/0.06/0.02 | 0.00/0.00/0.00 | 0.00/0.00/0.00 | 0.00/0.00/0.00 | 0.12/0.13/0.13 | 176/231/193 |

| Sub-ANBP | 0.04/0.03/0.01 | 0.06/0.07/0.13 | 0.04/0.09/0.10 | 0.04/0.09/0.14 | 0.73/0.63/0.54 | 0.00/0.00/0.03 | 0.04/0.04/0.03 | 0.00/0.01/0.00 | 0.04/0.05/0.03 | 49/116/71 |

| Sub-BN | 0.00/0.00/0.00 | 0.00/0.02/0.01 | 0.00/0.29/0.25 | 0.00/0.02/0.00 | 0.50/0.00/0.01 | 0.00/0.38/0.30 | 0.00/0.16/0.15 | 0.00/0.00/0.03 | 0.50/0.13/0.25 | 2/45/216 |

| Purge D/o | 0.00/0.00/0.00 | 0.00/0.01/0.00 | 0.03/0.06/0.06 | 0.00/0.01/0.00 | 0.00/0.01/0.01 | 0.00/0.03/0.05 | 0.81/0.76/0.77 | 0.00/0.00/0.00 | 0.16/0.13/0.11 | 37/142/374 |

| BED | 0.00/0.08/0.00 | 0.00/0.00/0.00 | 0.00/0.17/0.05 | 0.00/0.00/0.00 | 0.00/0.00/0.00 | 0.00/0.08/0.02 | 0.00/0.17/0.01 | 0.00/0.17/0.75 | 1.00/0.33/0.18 | 1/12/154 |

| No Dx | 0.03/0.02/0.00 | 0.00/0.00/0.00 | 0.00/0.00/0.01 | 0.05/0.07/0.01 | 0.00/0.00/0.00 | 0.00/0.01/0.02 | 0.02/0.04/0.02 | 0.00/0.01/0.02 | 0.89/0.85/0.91 | 270/461/1694 |

Cell entries represent the estimated probability of transitioning from Time 1 diagnosis to Time 2 diagnosis within any 3-month interval for patients with an initial diagnosis of ANR/ANBP/BN respectively. Probabilities >0.10 are represented in bold. The final column indicates the frequency of the Time 1 diagnosis by initial diagnosis of ANR/ANBP/BN respectively.

ANR, Anorexia nervosa (AN) restricting type; ANBP, AN binge/purge type; BN, bulimia nervosa; Sub-ANR, subthreshold ANR; Sub-ANBP, subthreshold ANBP; Sub-BN, subthreshold bulimia nervosa; Purge D/o, purging disorder; BED, binge eating disorder; No Dx, no eating disorder diagnosis.

Psychosocial functioning

Mixed-effects linear models comparing psychosocial scores during periods with the intake diagnosis to psychosocial scores during subthreshold presentations or recovery were significant for each of the three intake groups (ANR, ANBP and BN) (see Table 3). For women with intake ANR, pair-wise comparisons indicated that, compared to psychosocial functioning during full-criteria ANR, psychosocial functioning was significantly improved during periods of subthreshold ANR and purging disorder, and also during recovery; however, these women did not experience an improvement in psychosocial functioning during periods of subthreshold ANBP (p>0.01). For women with intake ANBP or BN, transition to all subthreshold presentations or recovery was associated with an improvement in psychosocial functioning (p<0.001), in comparison to the corresponding full-criteria diagnosis. To evaluate the possible difference in psychosocial functioning between subthreshold presentations and recovery, we ran pair-wise comparisons between each subthreshold presentation and recovery. For women with intake ANR, psychosocial functioning improved during recovery compared to during any of the subthreshold presentations (p<0.01). For women with intake ANBP or BN, psychosocial functioning generally improved during recovery, although there were no differences between subthreshold ANBP and recovery in the intake ANBP group, or between subthreshold ANR and recovery in the intake BN group.

Table 3.

Global psychosocial functioning in full syndrome versus subthreshold presentations: comparisons within intake diagnostic groups

| Baseline Dx | Transition Dx | Occurrence frequency |

Global psychosocial functioning |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scorea | Full criteria>Sub | Sub > Recovered | |||

| ANR (total observations: 4806) | ANR | 2586 | 10.85 ± 3.16 | ||

| Sub-ANR | 540 | 8.97 ± 2.83 | <0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Sub-ANBP | 147 | 10.42 ± 2.93 | N.S. | <0.001 | |

| Sub-BN | – | – | |||

| Purging disorder | 96 | 9.22 ± 1.56 | <0.001 | 0.004 | |

| BED | – | – | |||

| Recovered | 810 | 8.30 ± 2.61 | <0.001 | ||

| ANBP (total observations: 8568) | ANBP | 2622 | 11.71 ±3.21 | ||

| Sub-ANR | 723 | 10.88 ± 3.17 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Sub-ANBP | 363 | 9.84 ± 3.00 | <0.001 | N.S. | |

| Sub-BN | 144 | 10.62 ± 2.46 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Purging disorder | 435 | 10.90 ± 3.22 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| BED | – | – | |||

| Recovered | 1401 | 9.59 ± 2.69 | <0.001 | ||

| BN (total observations: 11 934) | BN | 3021 | 11.42±2.69 | ||

| Sub-ANR | 597 | 9.59 ± 2.16 | <0.001 | N.S. | |

| Sub-ANBP | 210 | 9.90 ± 2.81 | <0.001 | 0.02 | |

| Sub-BN | 651 | 10.39 ± 2.99 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Purging disorder | 1164 | 10.45 ± 2.80 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| BED | 477 | 10.78 ± 2.28 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Recovered | 5136 | 9.51 ± 2.58 | <0.001 | ||

Higher scores indicate greater impairment.

ANR, Anorexia nervosa (AN) restricting type; ANBP, AN binge/purge type; BN, bulimia nervosa; Sub-ANR, subthreshold ANR; Sub-ANBP, subthreshold ANBP; Sub-BN, subthreshold bulimia nervosa; BED, binge eating disorder; N.S., not significant.

Conclusions

DSM-IV-TR does not provide guidelines on how to classify individuals previously diagnosed with AN or BN who remain symptomatic but no longer meet full criteria for these disorders. Should these individuals retain the initial diagnosis of AN or BN or be assigned a separate diagnosis of EDNOS? Is symptomatic improvement, or symptomatic change, part of the natural course of AN or BN and therefore part of the illness, or does it constitute a different disorder (i.e. EDNOS)? This investigation sought to characterize specific subthreshold symptom presentations in women with initial diagnoses of AN or BN using longitudinal course data to inform this noslogical issue.

Our findings indicate that, during follow-up, the majority of this sample developed what we called subthreshold presentations. Consistent with our hypotheses, we found that subthreshold presentations tended to resemble intake diagnoses. Those with AN were most likely to develop subthreshold AN; those with BN were most likely to develop subthreshold BN. Furthermore, those with ANR were unlikely to develop subthreshold presentations resembling BN spectrum disorders, whereas those with ANBP or BN developed a range of presentations characterized by bingeing and purging.

For women with either type of AN, transition to subthreshold ANR or ANBP resulted from an increase in weight. For those with ANR who moved to sub-threshold ANBP, this transition also meant the onset of binge eating and/or purging behaviors; for those with ANBP who moved to subthreshold ANR, this transition meant a decrease in the binge eating and purging behaviors. For women with ANBP who moved to subthreshold BN or purging disorder, in addition to weight gain these transitions meant a persistence, and possibly an increase, in binge and/or purge symptoms. For women with BN, transitions to subthreshold BN or purging disorder resulted from a decrease in the frequency of binge eating and purge behaviors, or the cessation of binge eating and the continuation of purging. For those with BN who moved to subthreshold ANR, this transition meant both a decrease in binge/purge symptoms and weight loss. Thus, for most women, these transitions resulted from what could be described as symptomatic improvements, although this depended in part on the initial (or preceding) diagnosis. Furthermore, the sub-threshold categories themselves were broad, including individuals with symptoms ranging in severity (e.g. behavioral frequency).

During follow-up, women with lifetime diagnoses of AN and BN developed multiple subthreshold presentations over time. Although the duration of these subthreshold episodes was highly variable, ranging from 3 months to nearly 7 years, the median time in any subthreshold episode, irrespective of initial diagnosis, was <1 year. Our data indicate that, from sub-threshold presentations, individuals are as likely to return to full-syndrome diagnoses as to move to full recovery. These findings are consistent with those of Agras et al. (2009), who similarly found that EDNOS occurred between full-criteria AN or BN and recovery. Psychosocial analyses supported the intermediary status of the subthreshold presentations. In general, the subthreshold presentations were associated with overall psychosocial functioning scores that were improved compared to full-criteria ANR, ANBP or BN, but poorer compared to recovery, consistent with the behavioral symptom change inherent in these transitions. The magnitude of difference in psychosocial functioning seemed greatest between the full-criteria disorders and their subthreshold counterparts (i.e. ANR with subthreshold ANR, ANBP with sub-threshold ANBP, and BN with subthreshold BN).

Not all individuals who reach a subthreshold presentation progressed to full recovery; indeed, the majority of individuals in this sample with an initial diagnosis of AN did not recover during follow-up, whereas those with BN did (Herzog et al. 1999; Keel et al. 2005). Furthermore, although psychosocial functioning was relatively improved during the subthreshold presentations compared to AN or BN, scores remained at clinical levels (Leon et al. 1999).

Study strengths and limitations should be noted. This study included a comprehensive assessment of symptoms collected over a longitudinal period of follow-up in a large sample of women with EDs with a high retention rate. A unique strength was the availability of weekly symptom data, which permitted careful investigation of the range of subthreshold presentations in these women. Among the limitations, however, was the fact that as data collection began in 1986, prior to the establishment of the EDNOS category; this sample included only women with initial diagnoses of AN or BN. In future studies, it will be important to determine whether subthreshold presentations in women with lifetime AN or BN are similar with regard to symptoms, severity, course and treatment response to EDNOS presentations observed in women without lifetime AN or BN. In the latter group of women, EDNOS would constitute the most severe phase of illness, compared to in women with lifetime AN or BN, in which these periods are generally associated with some degree of improvement. An additional limitation is that the sample was treatment seeking, limiting generalizability to community samples or samples with a shorter duration of illness. Women in this study received a wide range of treatment during follow-up and although the potential impact of treatment on the emergence or course of these subthreshold presentations was of interest, it was outside the scope of this investigation. Finally, although consideration of change in psychosocial functioning was a strength of this study and begins to address limitations of previous research (Herzog et al. 1993; Milos et al. 2005; Agras et al. 2009), inclusion of a wider range of indices of functioning, particularly those that measure distress/impairment related to the ED symptoms, to inform the clinical utility of these distinctions, and perhaps to delineate ‘partial recovery/remission’ specifiers for EDs, is an important goal for future studies.

The Eating Disorders Workgroup for DSM-V is charged with the difficult task of culling and synthesizing nosological findings to inform revisions to the classification system. Our findings indicate that, for the majority of individuals with lifetime AN and/ or BN, the course of their illness will be marked by symptom fluctuations that could be clinically described as EDNOS. However, these data suggest these subthreshold presentations are a part of the course of illness for individuals with AN and/or BN, rather than different disorders (e.g. types of EDNOS). Our data do not suggest that these subthreshold presentations in women with lifetime AN or BN are distinct enough from the AN or BN to warrant a separate diagnosis as they are similar in symptomatic presentation, often time-limited, and not directive of course/outcome. Importantly, these findings raise questions about when and if it is ever appropriate to diagnose EDNOS in individuals with lifetime AN or BN. Well-designed studies that include comprehensive longitudinal assessment of a range of potentially important clinical validators that could help to clarify the boundaries between AN, BN and EDNOS are needed. Likewise, future research using more sensitive measures of clinical distress or impairment may help to clarify the boundaries between threshold EDs, partial recovery and full recovery.

Our findings may be useful in promoting discussion and inciting empirical work to address these issues. Recognition of these subthreshold presentations as broadened forms of AN or BN, as improved states of AN or BN, or a different ED diagnosis (i.e. EDNOS), has important nosological bearings and potential clinical implications (e.g. treatment indications, insurance coverage). Our data suggest that, for most women with lifetime AN or BN, EDNOS presentations may best be classified as part of the AN or BN diagnosis.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by RO1 MH038333 (PI D.B.H.) and F32 MH084396 (PI K.T.E.).

Footnotes

Some of the data in this paper were presented at the Eating Disorders Research Society Meeting in Montreal, Canada, September 2008.

Note that a 13-week duration criterion was used to be consistent with the definitions of ANR, ANBP and BN; a 26-week duration criterion was also tested and yielded similar findings.

Note that the individual indices (occupational, interpersonal and recreational functioning and satisfaction/subjective quality of life) were also analyzed separately and the pattern of findings was unchanged.

Declaration of Interest

None.

References

- Agras WS, Crow S, Mitchell JE, Halmi KA, Bryson S. A 4-year prospective study of eating disorder NOS compared with full eating disorder syndromes. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2009;42:565–570. doi: 10.1002/eat.20708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderluh M, Tchanturia K, Rabe-Heskith S, Collier D, Treasure J. Lifetime course of eating disorders: design and validity testing of a new strategy to define the eating disorders phenotype. Psychological Medicine. 2009;39:105–114. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th edn, text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Eddy KT, Dorer DJ, Franko DL, Tahilani K, Thompson-Brenner H, Herzog DB. Longitudinal diagnostic crossover of anorexia and bulimia nervosa: implications for DSM-V. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:245–250. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07060951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Bohn K. Eating disorder NOS (EDNOS): an example of the troublesome ‘not otherwise specified’ (NOS) category in DSM-IV. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43:691–701. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog DB, Dorer DJ, Keel PK, Selwyn SE, Ekeblad ER, Flores AT, Greenwood DN, Burwell RA, Keller MB. Recovery and relapse in anorexia and bulimia nervosa: a 7.5-year follow-up study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:829–837. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199907000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog DB, Hopkins JD, Burns CD. A follow-up study of 33 subdiagnostic eating disordered women. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1993;14:261–267. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199311)14:3<261::aid-eat2260140304>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel PK. Purging disorder: subthreshold variant or full-threshold eating disorder? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40:S89–S94. doi: 10.1002/eat.20453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel PK, Dorer DJ, Franko DL, Jackson SC, Herzog DB. Postremission predictors of relapse in women with eating disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:2263–2268. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.12.2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel PK, Striegel-Moore The validity and clinical utility of purging disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2009;42:706–719. doi: 10.1002/eat.20718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, Nielsen E, Endicott J, McDonald-Scott P, Andreasen NC. The Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation: a comprehensive interview for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1987;44:540–548. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180050009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon AC, Solomon DA, Mueller TI, Endicott J, Posternak M, Judd LL, Schlettler PJ, Akiskal HS, Keller MB. A brief assessment of psychosocial functioning of subjects with bipolar I disorder: the LIFE-RIFT. Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation Range of Impaired Functioning Tool. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2000;188:805–812. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200012000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon AC, Solomon DA, Mueller TI, Turvey CL, Endicott J, Keller MB. The Range of Impaired Functioning Tool (LIFE-RIFT): a brief measure of functional impairment. Psychological Medicine. 1999;29:869–878. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799008570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milos G, Spindler A, Schnyder U, Fairburn CG. Instability of eating disorder diagnoses: prospective study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;187:573–578. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.6.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2007. www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JJ, Vartanian LR, Brownell KD. The relationship between eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS) and officially recognized eating disorders: meta-analysis and implications for DSM. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:407–433. doi: 10.1037/a0015326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tozzi F, Thornton LM, Klump KL, Fichter MM, Halmi KA, Kaplan AS, Strober M, Woodside DB, Crow S, Mitchell JE, Rotondo A, Mauri M, Cassano G, Keel P, Plotnikov KH, Pollice C, Lilenfeld LR, Berrettini WH, Bulik CM, Kaye WH. Symptom fluctuation in eating disorder: correlates of diagnostic crossover. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:732–740. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]