Abstract

Copy number variants (CNVs) represent a frequent type of lesion in human genetic disorders that typically affects numerous genes simultaneously. This has raised the challenge of understanding which genes within a CNV drive clinical phenotypes. Although CNVs can arise by multiple mechanisms, a subset is driven by local genomic architecture permissive to recombination events that can lead to both deletions and duplications. Phenotypic analyses of patients with such reciprocal CNVs have revealed instances in which the phenotype is either identical or mirrored; strikingly, molecular studies have revealed that such phenotypes are often driven by reciprocal dosage defects of the same transcript. Here we explore how these observations can help the dissection of CNVs and inform the genetic architecture of CNV-induced disorders.

Introduction

CNVs have received significant attention in recent years, in part because the increased resolution of genomic analyses has uncovered such events to be both abundant in human genomes and relevant to the pathogenesis of both rare and complex traits. CNVs range in size from a kilobase (kb) to several megabases (Mb)1. Although some CNVs are found at high frequency in human populations and are thus thought to be a potential source of genetic diversity2,3, larger CNVs, especially de novo, are associated frequently with human disorders4; in addition to the documented involvement of CNVs in birth defects (e.g. craniofacial, cardiac, respiratory, renal) 5-12, CNVs are also understood to be enriched in the pathogenesis of neurodevelopmental and neurocognitive disorders, such as intellectual disability, schizophrenia, and autism spectrum disorders (ASD)6,13-20.

The increased resolution of array-comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) has catalyzed the hyper-acceleration of CNV discovery; recent advances in exome and genome sequencing analyses are likely to increase the pace of CNV discovery further21,22. In the midst of this progress, some acute interpretative problems have arisen. First, the rarity of most CNVs precludes their statistical analysis with regard to causality. Second, because some CNVs are mediated by non-homologous recombination-prone low copy repeats23-25, recurrence of such events is not deterministic of pathogenicity but reflective of local genomic architecture. Third, CNVs typically affect multiple genes, exacerbating the problem of assigning causality to particular transcripts within a CNV. Finally, the ascertainment of the clinical significance of CNVs is often complicated by clinical heterogeneity, non- penetrance and variable expressivity13,26-28.

Given the above challenges, a central question pertains to the contribution of each gene within a CNV to the phenotype. This is a complex issue; each CNV presents unique characteristics and interpretations that are driven, in part, by its gene content and associated clinical phenotype. Nonetheless, our survey of the current data available has identified some patterns emerging in a subclass of CNVs for which the presence of low copy repeats induce the generation of both deletions and duplications of the same segment. Here, we synthesize our current understanding of the genetic causality of these CNVs and ask whether emergent genetic models can illuminate and predict the pathomechanisms caused by this class of genetic mutations.

Reciprocal CNVs and clinical phenotypes

An examination of known reciprocal CNVs and their associated clinical features has indicated that reciprocal CNV-induced phenotypes can be broadly classified into four general categories: mirrored (deletions and duplications of the chromosomal region have opposite effects), identical, overlapping, and unique. Examples of these classes are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Phenotypes of the reciprocal CNVs for which at least one major driver has been identified.

| CNV locus | Total genes | CNV primary driver(s) | Deletion Phenotypes | Duplication Phenotypes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

|

Mirrored Phenotypes

| ||||

| 1q21.113, 27 | 7 | Unknown | Head size | |

| Psychiatric disorders | ||||

|

| ||||

| 2q136 | 6 | Unknown | Head size | |

|

| ||||

| 3q2929-32 | 21 | Unknown | Head size | |

|

| ||||

| 16p11.219, 20, 90, 97-99 | 29 | KCTD13 | Head size | |

| PRRT2 | Psychiatric disorders | |||

| Metabolic homeostasis | ||||

|

| ||||

| 17q11.233, 34 | 44 | RAI1 | Sleep regulation | |

| Metabolic homeostasis | ||||

|

| ||||

| Similar or Overlapping Phenotypes | ||||

|

| ||||

| 2q11.2100, 101 | 20 | Unknown | ASD* | ASD* |

|

| ||||

| 7q11.2315, 92, 102, 103 | 24 | ELN | Distinctive facial appearance | Facial dysmorphism |

| LIMK-1 | Cardiac abnormalities | Language and speech delay | ||

| Infantile hypercalcemia | Autism behavior | |||

| Growth retardation/developmental delay | Epilepsy | |||

|

| ||||

| 8p23.1104, 105 | 22 | GATA4 | Dysmorphic features | Dysmorphic features |

| Developmental delay | Developmental delay | |||

| Heart defects | Heart defects | |||

|

| ||||

| 8q24.36, 101, 106, 107 | 3 | Unknown | ASD* | ASD* |

| Epilepsy108 | ||||

|

| ||||

| 9q34.36, 109, 110 | 97 | Unknown | Craniofacial features | Non-syndromic, IQ>70* |

| Microcephaly | ||||

| Speech delay/developmental delay | ||||

| Respiratory failure | ||||

|

| ||||

| 15q13.3 | 6 | CHRNA7 | Intellectual disability | Intellectual disability |

| Epilepsy | Autism | |||

| Seizures | Recurrent ear infections, low set ears | |||

| Variable dysmorphism of the face and digits | Obesity | |||

|

| ||||

| 16p13.1126, 111, 112 | 7 | Unknown | Microcephaly | Microcephaly/macrocephaly |

| Sever intellectual disabilities | Moderate intellectual disabilities | |||

| Epilepsy | Autism spectrum disorders | |||

| Short stature | Cardiac defects | |||

| Cardiac defects | Dysmorphism | |||

| Dysmorphism | ||||

|

| ||||

| 17p13.3113-115 | 41 | Unknown | Miller-Dieker syndrome (MIM 247200): | Microcephaly |

| Lissencephaly | Dysgenesis of the corpus callosum | |||

| Intellectual disabilities | Cerebellar atrophy | |||

| Facial dysmorphism | Developmental delay/intellectual disabilities | |||

| Attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder | ||||

| Facial dysmorphism | ||||

|

| ||||

| 17q21.31116-118 | 5 | KANSL1 | Mild-to-moderate intellectual disability | Severe developmental delay |

| Distinctive facial features | Microcephaly | |||

| Epilepsy | Facial dysmorphism | |||

| Heart defects | Abnormal digits and hirsutism | |||

| Urogenital anomalies | Failure to thrive | |||

|

| ||||

| 22q11.244, 46, 47, 49, 51, 52 | 33 | TBX1 | Dysmorphic facial features | Dysmorphic facial features |

| Velocardio-facial syndrome (cleft/lip palate, velopharyngeal insufficiency) | Velopharyngeal insufficiency cleft/lip palate | |||

| Congenital heart disease (conotruncal) | Congenital heart disease (conotruncal) intellectual disabilities | |||

| Learning disabilities | Speech delay | |||

| Hearing loss | Hearing loss | |||

| Failure to thrive | ||||

Incomplete phenotyping of the patients harboring the lesion

Mirrored phenotypes

The 16p11.218-20, 1q21.113,27, 3q2929-32, and 17q11. 233,34 CNVs are well-known lesions associated with mirrored phenotypes. Phenotypic mirroring is not ubiquitous, but appears to apply to a subset of clinical features. These include head size abnormalities for the 3q29, 16p11.2 and 1q21.1 CNVs, energy balance defects for the 16p11.2 and 17p11.2 CNVs and, to some extent, mirrored psychiatric disorders for 16p11.2 and 1q21.1 CNVs based on a model in which autism and schizophrenia are two opposite extremes of a spectrum reflecting the under- or over-development of the social brain35.

Similarly, phenotypic examination of individuals with the 17p11.2 CNV revealed a mirroring co-morbidity affecting sleep regulation and energy balance control. Deletion and duplication of a 3.7Mb region in 17p11.2 result in two reciprocal syndromes, Smith-Magenis syndrome (SMS; MIM182290)36 and Potocki-Lupski syndrome (LPS; MIM610883)37,38. SMS is associated with moderate intellectual disability, distinctive facial features, sleep disturbances, behavioral problems, obesity and hypercholesterolemia39,40 whereas LPS is associated with infantile hypotonia, sleep apnea, structural cardiovascular anomalies41, kidney abnormalities42, learning disabilities, attention-deficit disorder, obsessive-compulsive behaviours, short stature, reduced weight, and failure to thrive43.

Identical phenotypes

There are several examples in which the core phenotypes of deletions and duplications contribute to the same phenotypic spectrum. For example, 22q11.2 deletions cause DiGeorge syndrome (DGS; MIM188400)44,45 and velocardiofacial syndrome (VCFS; MIM192430)45,46. These syndromes result in conotruncal congenital heart defects, velopharyngeal insufficiency, hypoparathyroidism, thymic aplasia or hypoplasia, craniofacial dysmorphism, learning difficulties and psychiatric disorders47-50. Duplications of the same genomic segment in DGS and VCFS patients have also been reported51-53. The phenotype of duplication (dup) patients is variable, ranging from normal to multiple defects reminiscent of DGS/VCFS phenotypes with shared clinical features; these include heart defects, velopharyngeal insufficiency with or without cleft palate, hypernasal speech, and urogenital abnormalities.

Overlapping, unique, and variable phenotypes

Finally, some phenotypes are unique to deletions or duplications. For example, epilepsy is associated with del16p11.2 but not with the reciprocal dup16p11.218. Others are overlapping, as exemplified by phenotypes associated with CNVs on 15p13.3 and 7q11.23; Sharp et al. reported a microdeletion syndrome characterized by cognitive impairment, seizures and a range of congenital abnormalities54 caused by recurrent deletions of 15q13.355. The variable phenotype of the 15q13.3 deletion has been extended to include autism, seizures, learning disabilities56,57, schizophrenia and epilepsy17,58-60. Adding to the complexity, that deletion in normal family members of probands, as well as in population controls, suggests that the deletion alone is not sufficient to cause intellectual disability. The reciprocal duplication is less frequent, with a few cases described to date28,61. The duplication was first identified in four patients with intellectual disability, autism, hypotonia, obesity, recurrent ear infections, and low set ears28. However, none of these patients had structural brain abnormalities or the epileptic seizures seen in deletion patients.

Reciprocal CNVs and genetic architecture

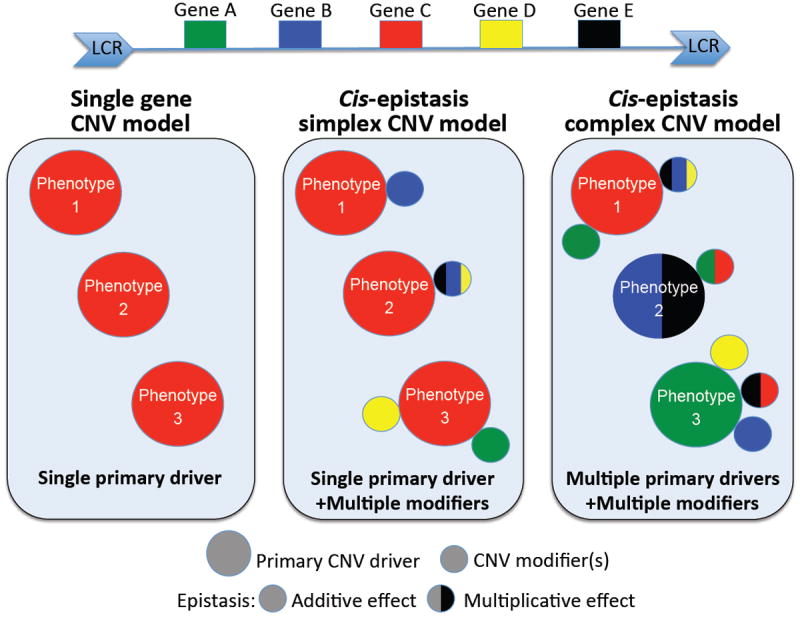

Are there any common patterns that can inform our understanding of the genetic drivers of the CNV-associated phenotypes for del and dup patients? Broadly, one can consider three basic models (Fig. 1): a) the single-gene CNV model, in which the phenotypes of deletion (del) or dup patients are the product of dosage imbalance of a single gene; b) the “simplex cis epistatic” model, in which dysfunction of a single gene is necessary and sufficient to establish phenotype, but is subject to modulation by epistasis effect exerted by other genes within the CNV; and c) the “complex cis-epistatic” model in which phenotypes are the result of the simultaneous dosage imbalance of numerous genes within the CNV, some of which drive specific endophenotypes and some of which exhibit complex additive and/or multiplicative relationships.

Figure 1. Theoretical models to explain penetrance and phenotypic variability of reciprocal CNVs.

Schematic representation of a genomic segment encompassing five genes (Gene A-E) flanked by low-copy repeats (LCRs). LCRs are depicted as blue arrows with the orientation indicated by the direction of the arrowheads. Recombination between LCRs results in reciprocal deletions and duplications. The “single gene” model posits that a single primary gene is the major driver of the phenotype; the single primary driver accounts for 100% of the expressivity and penetrance. Conversely, the cis-epistasis models posit that one or multiple genes are necessary and sufficient to cause phenotypes but epistasis interactions modulate the expressivity and penetrance of the phenotype(s). Two models arise: 1) A single primary driver or 2) Multiple primary drivers are sufficient to cause independent or same phenotypes. The other genes within the CNV modulate the penetrance and/or expressivity of the phenotype(s) primarily driven by the major driver(s).

Intuitively, the complexity intimated by the latter model is expected to be true and is consistent with our understanding of large genomic lesions, such as chromosomal abnormalities. For example, the additional copy of human chromosome 21 results in the increased expression of 29% of the genes; the remaining 71% of the expressed sequences encoded on this chromosome are either compensated for or are highly variable among individuals62. Thus, although most of the chromosome 21 transcripts are compensated for the gene-dosage effect, a subset of the overexpressed genes are likely major drivers and/or modulate the numerous of deleterious phenotypes observed in individuals with Down syndrome63. However, experimental dissection of reciprocal CNVs suggests that each of the other two models might not only be true, but in fact predominate in this class of genomic disorders. Caution is warranted, given that the number of reciprocal CNVs dissected successfully remains small and that in many instances phenotyping of patients is incomplete. Nonetheless, it is intriguing that the same paradigms are being observed in reciprocal CNVs at different regions, of different size, and with different phenotypic associations.

Reciprocal CNVs and single-gene defects

This class of CNVs is rare. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT) is the most common hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy, and CMT type 1A (CMT1A), the most common type of CMT, is subject to a gene dosage effect64. The primary genetic cause of CMT1A is a duplication of PMP22 resulting from the unequal crossover between two homologous repetitive elements that flank a 1.4-Mb region of chromosome 17p1265. Importantly, PMP22 frame-shift66 and loss of function point mutations67 have been found in severely affected CMT1A patients; likewise, same loss of function point mutations in Pmp22 were found in the Trembler-J mouse, a CMT1A model68. The reciprocal deletion of PMP22 is associated with non-progressive hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies (HNPP)69. Overexpression of PMP22 in mice causes a defect of myelination of the neurons that fully recapitulates the CMT phenotype70 whereas, as expected from human genetics, heterozygous PMP22 knock-out mice revealed a pathology comparable with HNPP71. Although CMT1A and HNPP are not mirrored disorders per se, these data emphasize the remarkable sensitivity of myelin stability to PMP22 gene dosage, since either over- or under-expression results in long-term myelin instability.

Reciprocal CNVs and cis-epistasis

This appears to be the most common variety among the handful of CNVs dissected to date. The major disease candidate gene TBX172, a member of the T-box transcription factors family, is localized between LCR-A and LCR-B on 22q11.2. Notably, altering the dosage of Tbx1 (both over- and under-expression) recapitulates DGS and VCFS in mice73. Further, both loss of function mutations and mutations shown to enhance the activity of TBX1 have been found in rare DGS/VCFS non-deleted cases74,75. These mutations could be considered as functionally equivalent to a deletion or a duplication of TBX1 respectively. Taken together, these data suggest that abnormal TBX1 dosage in either direction disrupts the same developmental pathways and result in similar developmental defects commonly ascribed to DGS/VCFS’s phenotypic spectrum.

It is important to note, however, that although TBX1 is the major driver of the 22q11.2 CNV phenotypes, patients with TBX1 point mutations are phenotypically not identical to patients with 22q11.2 deletions. For example, TBX1 is responsible for conotruncal anomaly face feature, cardiac defects, thymic hypoplasia, velopharyngeal insufficiency with cleft palate, and parathyroid dysfunction with hypocalcemia; however, there is no evidence of intellectual disabilities in patients with TBX1 mutations, suggesting that either other loci drive this component of the phenotype or that TBX1 might be subject to cis epistasis to develop cognitive defects76. The latter is supported by the detection of Tbx1 message in the frontal cortex and the hippocampus in mice77.

Similar to the 22qdel/dup CNV, a single gene has been proposed to be the major driver of mirrored phenotypes of the 16p11.2 CNV. Systematic screening of genes whose overexpression in zebrafish embryos causes microcephaly led to the identification of KCTD13 as a major driver for the neuroanatomical phenotypes of the 16p11.2 CNV78. Consistent with this observation, suppression of the same gene gave rise to macrocephalic embryos and the phenotypes were ascribed to changes in neurogenesis and apoptosis in the developing brain78. Genetic evidence supported this finding further. First, an atypical deletion of five genes, including KCTD13, segregated in a family with isolated ASD79; second, a patient with ASD was found to harbor a de novo deletion of a portion of KCTD1378. Further, epistatic analysis of KCTD13 in zebrafish embryos highlighted a contributory effect of two more genes from within the CNV, MVP and MAPK3 on the expressivity of the head size phenotype78; notably, all three genes (KCTD13, MAPK3 and MVP) are present in the aforementioned 5-gene deletion79. Moreover, the patient with the de novo KCTD13 deletion also harboured an inherited heterozygous deletion distal to 16p11.2, suggesting a possible interaction with lesions outside this CNV78.

Similar to the 22qdel/dup CNV, a single gene has been proposed to be the major driver of mirrored phenotypes of the 16p11.2 CNV. Systematic screening of genes whose overexpression in zebrafish embryos causes microcephaly led to the identification of KCTD13 as a major driver for the neuroanatomical phenotypes of the 16p11.2 CNV78. Consistent with this observation, suppression of the same gene gave rise to macrocephalic embryos and the phenotypes were ascribed to changes in neurogenesis and apoptosis in the developing brain78. Genetic evidence supported this finding further. First, an atypical deletion of five genes, including KCTD13, segregated in a family with isolated ASD79; second, a patient with ASD was found to harbor a de novo deletion of a portion of KCTD1378. Further, epistatic analysis of KCTD13 in zebrafish embryos highlighted a contributory effect of two more genes from within the CNV, MVP and MAPK3 on the expressivity of the head size phenotype78; notably, all three genes (KCTD13, MAPK3 and MVP) are present in the aforementioned 5-gene deletion79. Moreover, the patient with the de novo KCTD13 deletion also harboured an inherited heterozygous deletion distal to 16p11.2, suggesting a possible interaction with lesions outside this CNV78.

Mutations in RAI1 have been found in Smith-Magenis syndrome80 suggesting that haploinsufficiency of RAI1 is probably responsible for the behavioral, neurologic, and craniofacial aspects of this syndrome. These phenotypes are also observed in dup patients with Potocki-Lupski syndrome. Further, increased anxiety and hyperactivity, growth retardation, and altered motor and sensory coordination, were observed in Rai1-overexpressant mice, recapitulating phenotypes observed in patients with 17p11.2 duplication81. These data suggest that over- and under-expression of RAI1 cause similar phenotypes that are pathognomonic of the two syndromes. The 17q11.2 del/dup patients also exhibit mirrored metabolic balance and sleep control disorders. Detailed analyses of the del and dup mice models fully recapitulated the mirrored metabolic phenotype observed in patients, whereas a defect of the circadian rhythm has only been found in the del mice to date82. Two mouse models have been generated subsequently to mimic over- and under-expression of RAI1 (TgRai1 and Rai1+/- respectively). These studies pointed to the fact that neither the duplication nor the deletion CNV-associated phenotypes can be attributed exclusively to the RAI1 dosage. The Rai1+/- and del mice share the same phenotype, whereas the TgRai1 and dup mice phenotypes are discordant with an absence of changes in the serum chemistry and body composition in the TgRai1 mice compared to the dup mice33. As such, the mirrored metabolic and sleep control phenotypes seen in SMS/PTLS seem unlikely to be driven by Rai1 dosage alone. We speculate that copy number change of RAI1 and other genes in cis, such as the candidate SREBF183, with one of them exerting a synergistic or additive epistatic effect on the other, is required to fully manifest the reciprocal phenotypes of SMS and PTLS.

Genetic heterogeneity underlying non-reciprocal phenotypes

We have been unable to find an example in which two genes within a reciprocal CNV can drive a similar/mirrored phenotype that is shared among patients with the same del/dup. Nonetheless, each type of lesion bears phenotypes, in addition to the reciprocal/similar manifestations, that are unique; in such instances, the composite phenotype of the CNV appears to be the synthesis of defects driven by more than one genes under a classical paradigm of a contiguous gene syndrome. For example, two genes have been implicated in the etiology of the Williams-Beuren syndrome, each gene responsible for a different phenotypic component of del/dup patients. Haploinsufficiency of elastin (ELN) is responsible for the supravalvular aortic stenosis and other arteriopathies but not cognitive defects in patients with WBS84,85. Further, the identification of a small deletion including ELN and LIMK-1 in two families with partial WBS implicated LIMK-1 hemizygosity in impaired visuospatial constructive cognition86. Finally, suppression of GTF2I and GTF2IRD1 in mice recapitulated some WBS phenotypes such as microcephaly, retarded growth, and skeletal and craniofacial defects87,88, suggesting that these two transcription factors are either possible drivers of the aforementioned phenotypes or modifiers exerting an epistatic effect to modulate cardiac and cognitive defects driven by the major drivers ELN and LIMK-1 respectively.

Such observations are also reported for other CNVs. For example, in addition to mirrored phenotypes observed in the 16p11.2 CNV, epilepsy has been found only in del patients89,90. The recent finding of loss-of-function mutations in PRRT2, one of the 29 genes of the 16p11.2 CNV, in patients with epilepsy and seizures91 suggests that 1) PRRT2 is sufficient to cause epilepsy and seizures and 2) KCTD13 is unlikely the only driver of the 16p11.2 phenotypes.

Reciprocal CNVs, variable penetrance and variable expressivity

A complicating factor of these post-hoc analyses of CNV architecture is that most CNVs exhibit marked variability and non-penetrance. Moreover, phenotyping of siblings or parents is often missing or is partially reported; mild phenotypes are often not subjected to aCGH, leading to fewer duplication discoveries compared to deletion; and poor investigation and estimation of CNV burden in controls remains a source of concern. Despite these limitations, some potentially valuable observations are emerging that are likewise informing architecture of reciprocal CNVs. First, duplications appear to be more frequently inherited, whilst deletions are more frequently reported in patients to be de novo, suggesting that the latter are more likely to be penetrant92,93-95. Second, duplications are generally milder and have greater variability in expressivity than deletions92,96.

With regard to gene content, we are cautious in reaching conclusions about the relative prevalence of the three gene-based models (Fig 1). The handful of examples available to us predict that the “cis-epistasis” model is the most predominant. This would in turn predict that specifically for reciprocal phenotypes in reciprocal CNVs, there will be a single major driver influenced by proximal genetic content (as well as variation elsewhere in the genome). This is a testable hypothesis; for instance, the 16p11.2 data implicating haploinsufficiency of KCTD13 in ASD would predict a role for the same gene in the development of schizophrenia. More broadly, there are numerous examples of reciprocal CNVs in the morbid human genome whose genic etiology is not yet understood. For example, a 9-gene deletion on 1q21.1 is associated with microcephaly13,27, while the dup is associated with macrocephaly13,27; once again our model would predict that dosage imbalance of a single transcript should account for both phenotypes.

Finally, a “cis-epistasis” model (Fig 1) also predicts that “fixing” the dosage imbalance of a single driver gene within a CNV might represent an efficient means of identifying contributory interactors, which would be challenging to recognize using standard genetic or statistical methods. Initial data from the 16p11.2 CNV offer an indication that this approach is experimentally tractable but, naturally, such studies need to be reproduced for other regions. For this purpose, sensitizing the genetic background of appropriate model organisms to either haploinsufficiency or increased expression of the candidate CNV driver could be an useful template for the systematic screening for the ability of both cis and trans factors to change the penetrance and/or expressivity of driver-induced phenotypes.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to those colleagues whose work we were unable to discuss due to space constraints. We thank Erica Davis for her comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by a grant from the Simons Foundation and P50 MH094268 from the NIH. NK is a Distinguished Brumley Professor.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- *1.Redon R, et al. Global variation in copy number in the human genome. Nature. 2006;444:444–454. doi: 10.1038/nature05329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *2.Iafrate AJ, et al. Detection of large-scale variation in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2004;36:949–951. doi: 10.1038/ng1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *3.Sebat J, et al. Large-scale copy number polymorphism in the human genome. Science. 2004;305:525–528. doi: 10.1126/science.1098918. These three studies gave an early appreciation of the distribution and high prevalence of polymorphic CNVs in the human genome based on typing of a control population. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCarroll SA, Altshuler DM. Copy-number variation and association studies of human disease. Nat Genet. 2007;39:S37–42. doi: 10.1038/ng2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen X, et al. Detection of copy number variants reveals association of cilia genes with neural tube defects. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54492. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **6.Cooper GM, et al. A copy number variation morbidity map of developmental delay. Nature genetics. 2011;43:838–846. doi: 10.1038/ng.909. A large study comparing CNV burden in children with intellectual disability to unaffected adult controls. The data estimated that ~14% of disease in these children is caused by CNVs >400 kb in size. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fakhro KA, et al. Rare copy number variations in congenital heart disease patients identify unique genes in left-right patterning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:2915–2920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019645108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenway SC, et al. De novo copy number variants identify new genes and loci in isolated sporadic tetralogy of Fallot. Nature genetics. 2009;41:931–935. doi: 10.1038/ng.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osoegawa K, et al. Identification of novel candidate genes associated with cleft lip and palate using array comparative genomic hybridisation. J Med Genet. 2008;45:81–86. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.052191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanna-Cherchi S, et al. Copy-number disorders are a common cause of congenital kidney malformations. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91:987–997. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scott DA, et al. Genome-wide oligonucleotide-based array comparative genome hybridization analysis of non-isolated congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:424–430. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Serra-Juhe C, et al. Contribution of rare copy number variants to isolated human malformations. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45530. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *13.Brunetti-Pierri N, et al. Recurrent reciprocal 1q21.1 deletions and duplications associated with microcephaly or macrocephaly and developmental and behavioral abnormalities. Nature genetics. 2008;40:1466–1471. doi: 10.1038/ng.279. This study pointed to the reciprocal nature of anatomical defects associated with the 1q21 CNV. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coe BP, Girirajan S, Eichler EE. The genetic variability and commonality of neurodevelopmental disease. American journal of medical genetics Part C, Seminars in medical genetics. 2012;160C:118–129. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanders SJ, et al. Multiple recurrent de novo CNVs, including duplications of the 7q11.23 Williams syndrome region, are strongly associated with autism. Neuron. 2011;70:863–885. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **16.Sebat J, et al. Strong association of de novo copy number mutations with autism. Science. 2007;316:445–449. doi: 10.1126/science.1138659. One of the first studies to highlight the strong link between de novo CNVs and autism. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *17.Stefansson H, et al. Large recurrent microdeletions associated with schizophrenia. Nature. 2008;455:232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature07229. An study highlighting the role of rare, large CNVs in schizophrenia. Some of the recurrent CNVs detected in that study, were alredy (or have since) been also associated with autism. Refs #18, #19, and #60 expand on that subject. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **18.Weiss LA, et al. Association between microdeletion and microduplication at 16p11.2 and autism. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:667–675. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa075974. One of the first studies to highlight the role of this CNV in autism. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCarthy SE, et al. Microduplications of 16p11.2 are associated with schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1223–1227. doi: 10.1038/ng.474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar RA, et al. Recurrent 16p11.2 microdeletions in autism. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:628–638. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abecasis GR, et al. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *22.Krumm N, et al. Copy number variation detection and genotyping from exome sequence data. Genome Res. 2012;22:1525–1532. doi: 10.1101/gr.138115.112. Development of CoNIFER, a computational algorithm that can identify rare CNVs, as well as copy number genotyping of copy number polymorphic loci from exome reads. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lupski JR. Genomic disorders: structural features of the genome can lead to DNA rearrangements and human disease traits. Trends Genet. 1998;14:417–422. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01555-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee JA, Carvalho CM, Lupski JR. A DNA replication mechanism for generating nonrecurrent rearrangements associated with genomic disorders. Cell. 2007;131:1235–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stankiewicz P, Lupski JR. Genome architecture, rearrangements and genomic disorders. Trends Genet. 2002;18:74–82. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)02592-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hannes FD, et al. Recurrent reciprocal deletions and duplications of 16p13.11: the deletion is a risk factor for MR/MCA while the duplication may be a rare benign variant. Journal of medical genetics. 2009;46:223–232. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.055202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *27.Mefford HC, et al. Recurrent rearrangements of chromosome 1q21.1 and variable pediatric phenotypes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1685–1699. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805384. The study of a large cohort with various neurodevelopmental phenotypes defined the 1q21 del/dup as a major contributor and highlighted the marked phenotypic variability associated with this CNV. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Bon BW, et al. Further delineation of the 15q13 microdeletion and duplication syndromes: a clinical spectrum varying from non-pathogenic to a severe outcome. Journal of medical genetics. 2009;46:511–523. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.063412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ballif BC, et al. Expanding the clinical phenotype of the 3q29 microdeletion syndrome and characterization of the reciprocal microduplication. Mol Cytogenet. 2008;1:8. doi: 10.1186/1755-8166-1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lisi EC, et al. 3q29 interstitial microduplication: a new syndrome in a three-generation family. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:601–609. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mulle JG, et al. Microdeletions of 3q29 confer high risk for schizophrenia. American journal of human genetics. 2010;87:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Willatt L, et al. 3q29 microdeletion syndrome: clinical and molecular characterization of a new syndrome. American journal of human genetics. 2005;77:154–160. doi: 10.1086/431653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *33.Lacaria M, et al. A duplication CNV that conveys traits reciprocal to metabolic syndrome and protects against diet-induced obesity in mice and men. PLoS genetics. 2012;8:e1002713. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002713. Report of mirrored energy balance phenotypes in mouse models for the Smith Magenis/Potocki-Lupski region. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *34.Williams SR, Zies D, Mullegama SV, Grotewiel MS, Elsea SH. Smith-Magenis syndrome results in disruption of CLOCK gene transcription and reveals an integral role for RAI1 in the maintenance of circadian rhythmicity. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:941–949. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.04.013. A role for RAI1 in the control of the circadian rhythmicity. These data are consistent with sleep disorders observed in patients with Smith-Magenis syndrome. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **35.Crespi B, Badcock C. Psychosis and autism as diametrical disorders of the social brain. The Behavioral and brain sciences. 2008;31:241–261. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X08004214. discussion 261-320, A study highlighting the reciprocal relationship between brain size, autism, and schizophrenia. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith AC, et al. Interstitial deletion of (17)(p11.2p11.2) in nine patients. Am J Med Genet. 1986;24:393–414. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320240303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Potocki L, et al. Molecular mechanism for duplication 17p11.2- the homologous recombination reciprocal of the Smith-Magenis microdeletion. Nature genetics. 2000;24:84–87. doi: 10.1038/71743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Potocki L, et al. Characterization of Potocki-Lupski syndrome (dup(17)(p11.2p11.2)) and delineation of a dosage-sensitive critical interval that can convey an autism phenotype. American journal of human genetics. 2007;80:633–649. doi: 10.1086/512864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Edelman EA, et al. Gender, genotype, and phenotype differences in Smith-Magenis syndrome: a meta-analysis of 105 cases. Clin Genet. 2007;71:540–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ricard G, et al. Phenotypic consequences of copy number variation: insights from Smith-Magenis and Potocki-Lupski syndrome mouse models. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000543. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanchez-Valle A, Pierpont ME, Potocki L. The severe end of the spectrum: Hypoplastic left heart in Potocki-Lupski syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:363–366. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goh ES, et al. Definition of a critical genetic interval related to kidney abnormalities in the Potocki-Lupski syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158A:1579–1588. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soler-Alfonso C, et al. Potocki-Lupski syndrome: a microduplication syndrome associated with oropharyngeal dysphagia and failure to thrive. J Pediatr. 2011;158:655–659. e652. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.09.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilson DI, et al. DiGeorge syndrome with isolated aortic coarctation and isolated ventricular septal defect in three sibs with a 22q11 deletion of maternal origin. British heart journal. 1991;66:308–312. doi: 10.1136/hrt.66.4.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carelle-Calmels N, et al. Genetic compensation in a human genomic disorder. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1211–1216. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Driscoll DA, et al. Deletions and microdeletions of 22q11.2 in velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1992;44:261–268. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320440237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kobrynski LJ, Sullivan KE. Velocardiofacial syndrome, DiGeorge syndrome: the chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndromes. Lancet. 2007;370:1443–1452. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61601-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ryan AK, et al. Spectrum of clinical features associated with interstitial chromosome 22q11 deletions: a European collaborative study. J Med Genet. 1997;34:798–804. doi: 10.1136/jmg.34.10.798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scambler PJ. The 22q11 deletion syndromes. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:2421–2426. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.16.2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shprintzen RJ, et al. A new syndrome involving cleft palate, cardiac anomalies, typical facies, and learning disabilities: velo-cardio-facial syndrome. The Cleft palate journal. 1978;15:56–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ensenauer RE, et al. Microduplication 22q11.2, an emerging syndrome: clinical, cytogenetic, and molecular analysis of thirteen patients. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:1027–1040. doi: 10.1086/378818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Portnoi MF, et al. 22q11.2 duplication syndrome: two new familial cases with some overlapping features with DiGeorge/velocardiofacial syndromes. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;137:47–51. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yobb TM, et al. Microduplication and triplication of 22q11.2: a highly variable syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:865–876. doi: 10.1086/429841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sharp AJ, et al. A recurrent 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome associated with mental retardation and seizures. Nature genetics. 2008;40:322–328. doi: 10.1038/ng.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sharp AJ, et al. Characterization of a recurrent 15q24 microdeletion syndrome. Human molecular genetics. 2007;16:567–572. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cook EH, Jr, et al. Autism or atypical autism in maternally but not paternally derived proximal 15q duplication. American journal of human genetics. 1997;60:928–934. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dennis NR, et al. Clinical findings in 33 subjects with large supernumerary marker(15) chromosomes and 3 subjects with triplication of 15q11-q13. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:434–441. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Helbig I, et al. 15q13.3 microdeletions increase risk of idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Nature genetics. 2009;41:160–162. doi: 10.1038/ng.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miller DT, et al. Microdeletion/duplication at 15q13.2q13.3 among individuals with features of autism and other neuropsychiatric disorders. Journal of medical genetics. 2009;46:242–248. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.059907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *60.Stone JL, M OD, Gurling H, Kirov GK, Blackwood DH, Corvin A, Craddock NJ, Gill M. Rare chromosomal deletions and duplications increase risk of schizophrenia. Nature. 2008;455:237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature07239. Similar to ref #16, this is part of the same wave of CNV discoveries as major drivers of neuropsychiatric traits. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shinawi M, et al. A small recurrent deletion within 15q13.3 is associated with a range of neurodevelopmental phenotypes. Nature genetics. 2009;41:1269–1271. doi: 10.1038/ng.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ait Yahya-Graison E, et al. Classification of human chromosome 21 gene-expression variations in Down syndrome: impact on disease phenotypes. American journal of human genetics. 2007;81:475–491. doi: 10.1086/520000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Korenberg JR, et al. Down syndrome phenotypes: the consequences of chromosomal imbalance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91:4997–5001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lupski JR, et al. DNA duplication associated with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A. Cell. 1991;66:219–232. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90613-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Patel PI, et al. The gene for the peripheral myelin protein PMP-22 is a candidate for Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A. Nat Genet. 1992;1:159–165. doi: 10.1038/ng0692-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ionasescu VV, et al. Severe Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy type 1A with 1-base pair deletion and frameshift mutation in the peripheral myelin protein 22 gene. Muscle Nerve. 1997;20:1308–1310. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199710)20:10<1308::aid-mus14>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **67.Valentijn LJ, et al. Identical point mutations of PMP-22 in Trembler-J mouse and Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A. Nature genetics. 1992;2:288–291. doi: 10.1038/ng1292-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **68.Suter U, et al. Trembler mouse carries a point mutation in a myelin gene. Nature. 1992;356:241–244. doi: 10.1038/356241a0. These two papers, together, catalyzed the identification of a single gene (PMP22) as the major driver of the phenotype in a CNV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chance PF, et al. DNA deletion associated with hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies. Cell. 1993;72:143–151. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90058-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Robaglia-Schlupp A, et al. PMP22 overexpression causes dysmyelination in mice. Brain. 2002;125:2213–2221. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Adlkofer K, et al. Heterozygous peripheral myelin protein 22-deficient mice are affected by a progressive demyelinating tomaculous neuropathy. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4662–4671. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-12-04662.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Merscher S, et al. TBX1 is responsible for cardiovascular defects in velo-cardio-facial/DiGeorge syndrome. Cell. 2001;104:619–629. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00247-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liao J, et al. Full spectrum of malformations in velo-cardio-facial syndrome/DiGeorge syndrome mouse models by altering Tbx1 dosage. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1577–1585. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Torres-Juan L, et al. Mutations in TBX1 genocopy the 22q11.2 deletion and duplication syndromes: a new susceptibility factor for mental retardation. European journal of human genetics : EJHG. 2007;15:658–663. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zweier C, Sticht H, Aydin-Yaylagul I, Campbell CE, Rauch A. Human TBX1 missense mutations cause gain of function resulting in the same phenotype as 22q11.2 deletions. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:510–517. doi: 10.1086/511993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yagi H, et al. Role of TBX1 in human del22q11.2 syndrome. Lancet. 2003;362:1366–1373. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14632-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hiramoto T, et al. Tbx1: identification of a 22q11.2 gene as a risk factor for autism spectrum disorder in a mouse model. Human molecular genetics. 2011;20:4775–4785. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **78.Golzio C, et al. KCTD13 is a major driver of mirrored neuroanatomical phenotypes of the 16p11.2 copy number variant. Nature. 2012;485:363–367. doi: 10.1038/nature11091. The first systematic functional dissection of a CNV showing that modulation of KCTD13 expression leads to mirrored neuroanaotmical phenotypes. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Crepel A, et al. Narrowing the critical deletion region for autism spectrum disorders on 16p11.2. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2011;156:243–245. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Slager RE, Newton TL, Vlangos CN, Finucane B, Elsea SH. Mutations in RAI1 associated with Smith-Magenis syndrome. Nat Genet. 2003;33:466–468. doi: 10.1038/ng1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Girirajan S, et al. How much is too much? Phenotypic consequences of Rai1 overexpression in mice. European journal of human genetics : EJHG. 2008;16:941–954. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bi W, et al. Rai1 deficiency in mice causes learning impairment and motor dysfunction, whereas Rai1 heterozygous mice display minimal behavioral phenotypes. Human molecular genetics. 2007;16:1802–1813. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shimano H, et al. Overproduction of cholesterol and fatty acids causes massive liver enlargement in transgenic mice expressing truncated SREBP-1a. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1575–1584. doi: 10.1172/JCI118951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Delio M, et al. Spectrum of elastin sequence variants and cardiovascular phenotypes in 49 patients with Williams-Beuren syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2013 doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Micale L, et al. Identification and characterization of seven novel mutations of elastin gene in a cohort of patients affected by supravalvular aortic stenosis. European journal of human genetics : EJHG. 2010;18:317–323. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Frangiskakis JM, et al. LIM-kinase1 hemizygosity implicated in impaired visuospatial constructive cognition. Cell. 1996;86:59–69. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Enkhmandakh B, et al. Essential functions of the Williams-Beuren syndrome-associated TFII-I genes in embryonic development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:181–186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811531106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Morris CA, et al. GTF2I hemizygosity implicated in mental retardation in Williams syndrome: genotype-phenotype analysis of five families with deletions in the Williams syndrome region. Am J Med Genet A. 2003;123A:45–59. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ghebranious N, Giampietro PF, Wesbrook FP, Rezkalla SH. A novel microdeletion at 16p11.2 harbors candidate genes for aortic valve development, seizure disorder, and mild mental retardation. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A:1462–1471. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shinawi M, et al. Recurrent reciprocal 16p11.2 rearrangements associated with global developmental delay, behavioural problems, dysmorphism, epilepsy, and abnormal head size. Journal of medical genetics. 2010;47:332–341. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.073015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *91.Ono S, et al. Mutations in PRRT2 responsible for paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesias also cause benign familial infantile convulsions. Journal of human genetics. 2012;57:338–341. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2012.23. The first report of mutations in PRRT2, localized within the 16p11.2 CNV, in seizures. This study suggests that PRRT2 is the primary driver of seizures observed in patients with the 16p11.2 deletions. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Van der Aa N, et al. Fourteen new cases contribute to the characterization of the 7q11.23 microduplication syndrome. Eur J Med Genet. 2009;52:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ounap K, Laidre P, Bartsch O, Rein R, Lipping-Sitska M. Familial Williams-Beuren syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1998;80:491–493. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19981228)80:5<491::aid-ajmg10>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pankau R, et al. Familial Williams-Beuren syndrome showing varying clinical expression. Am J Med Genet. 2001;98:324–329. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20010201)98:4<324::aid-ajmg1103>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *95.Delio M, et al. Enhanced Maternal Origin of the 22q11.2 Deletion in Velocardiofacial and DiGeorge Syndromes. American journal of human genetics. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.01.018. A high frequency of maternal origin of the 22q11.2 deletion in Velocardial and DiGeorge cases. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Szafranski P, et al. Structures and molecular mechanisms for common 15q13.3 microduplications involving CHRNA7: benign or pathological? Hum Mutat. 2010;31:840–850. doi: 10.1002/humu.21284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **97.Horev G, et al. Dosage-dependent phenotypes in models of 16p11.2 lesions found in autism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:17076–17081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114042108. The first report of mouse models engineered for the 16p11.2 CNVs (del and dup). The study showed that the two mouse models have neuranatomical phenotypes analogous to patients. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *98.Jacquemont S, et al. Mirror extreme BMI phenotypes associated with gene dosage at the chromosome 16p11.2 locus. Nature. 2011;478:97–102. doi: 10.1038/nature10406. The first evidence that reciprocal dosage changes of genes from the 16p11.2 CNV leads to mirrored BMI phenotypes, suggesting that 16p11.2 CNV drivers are responsible for the maintenance of energy balance. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Walters RG, et al. A new highly penetrant form of obesity due to deletions on chromosome 16p11.2. Nature. 2010;463:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nature08727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **100.Girirajan S, et al. Phenotypic heterogeneity of genomic disorders and rare copy-number variants. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1321–1331. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200395. Analysis of the causes of phenotypic variability in patients with large CNV of unknown significance. The study reported extreme phenotypes in children with a second CNV of unknown significance. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *101.Pinto D, et al. Functional impact of global rare copy number variation in autism spectrum disorders. Nature. 2010;466:368–372. doi: 10.1038/nature09146. A genome-wide analysis of rare CNVs and coding variants in autism, shoing enrichment for known autism genes and for discrete biochemical pathways. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Berg JS, et al. Speech delay and autism spectrum behaviors are frequently associated with duplication of the 7q11.23 Williams-Beuren syndrome region. Genet Med. 2007;9:427–441. doi: 10.1097/gim.0b013e3180986192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Torniero C, et al. Dysmorphic features, simplified gyral pattern and 7q11.23 duplication reciprocal to the Williams-Beuren deletion. European journal of human genetics : EJHG. 2008;16:880–887. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wat MJ, et al. Chromosome 8p23.1 deletions as a cause of complex congenital heart defects and diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149A:1661–1677. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yu S, et al. Cardiac defects are infrequent findings in individuals with 8p23.1 genomic duplications containing GATA4. Circulation. Cardiovascular genetics. 2011;4:620–625. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.111.960302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Itsara A, et al. De novo rates and selection of large copy number variation. Genome Res. 2010;20:1469–1481. doi: 10.1101/gr.107680.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rosenfeld JA, et al. Copy number variations associated with autism spectrum disorders contribute to a spectrum of neurodevelopmental disorders. Genet Med. 2010;12:694–702. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181f0c5f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bonaglia MC, et al. A 2.3 Mb duplication of chromosome 8q24.3 associated with severe mental retardation and epilepsy detected by standard karyotype. European journal of human genetics : EJHG. 2005;13:586–591. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yatsenko SA, et al. Deletion 9q34.3 syndrome: genotype-phenotype correlations and an extended deletion in a patient with features of Opitz C trigonocephaly. J Med Genet. 2005;42:328–335. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.028258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bremer A, et al. Copy number variation characteristics in subpopulations of patients with autism spectrum disorders. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2011;156:115–124. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Nagamani SC, et al. Phenotypic manifestations of copy number variation in chromosome 16p13.11. European journal of human genetics : EJHG. 2011;19:280–286. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ramalingam A, et al. 16p13.11 duplication is a risk factor for a wide spectrum of neuropsychiatric disorders. J Hum Genet. 2011;56:541–544. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2011.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bi W, et al. Increased LIS1 expression affects human and mouse brain development. Nat Genet. 2009;41:168–177. doi: 10.1038/ng.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Roos L, et al. A new microduplication syndrome encompassing the region of the Miller-Dieker (17p13 deletion) syndrome. J Med Genet. 2009;46:703–710. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.065094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Toyo-oka K, et al. 14-3-3epsilon is important for neuronal migration by binding to NUDEL: a molecular explanation for Miller-Dieker syndrome. Nat Genet. 2003;34:274–285. doi: 10.1038/ng1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Grisart B, et al. 17q21.31 microduplication patients are characterised by behavioural problems and poor social interaction. J Med Genet. 2009;46:524–530. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.065367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kirchhoff M, Bisgaard AM, Duno M, Hansen FJ, Schwartz MA. 17q21.31 microduplication, reciprocal to the newly described 17q21.31 microdeletion, in a girl with severe psychomotor developmental delay and dysmorphic craniofacial features. Eur J Med Genet. 2007;50:256–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Koolen DA, et al. Clinical and molecular delineation of the 17q21.31 microdeletion syndrome. J Med Genet. 2008;45:710–720. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.058701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]