Abstract

The synthesis and characterization of spin-labeled phospholipids (SLP) – derivatives of 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphothioethanol (PTE) – with pH-reporting nitroxides that are covalently attached to the lipid’s polar head group is being reported. Two lipids were synthesized by reactions of PTE with thiol-specific pH-sensitive methanethiosulfonate spin labels methanethiosulfonic acid S-(1-oxyl-2,2,3,5,5-pentamethylimidazolidin-4-ylmethyl) ester (IMTSL) and S-4-(4-(dimethylamino)-2-ethyl-5,5-dimethyl-1-oxyl-2,5-dihydro-1 H-imidazol-2-yl)benzyl methanethiosulfonate (IKMTSL). The pKa value of the IMTSL-PTE lipid measured by EPR titration in aqueous buffer/iso-propanol solutions of various compositions was found to be essentially the same – pKa≈2.35 – indicating that in mixed aqueous/organic solvents the amphiphilic lipid molecules could be shielded from changing bulk conditions by a local shell of solvent molecules. To overcome this problem, the spin-labeled lipids were modeled by synthesizing IMTSL- and IKMTSL-2-mercaptoethanol adducts. These model compounds yielded the intrinsic for IMTSL-PTE and IKMTSL-PTE in aqueous buffers as 3.33+0.03 and 5.98+0.03, respectively. A series of EPR titrations of IMTSL-PTE in mixed water/iso-propanol solution allowed for calibrating the polarity-induced pKa shifts, , vs. bulk solvent dielectric permittivity. These calibration data allowed for estimating the local dielectric constant, εeff, experienced by the reporter nitroxide of the IMTSL-PTE lipid incorporated into the non-ionic Triton® X-100 micelles as 60±5 and 57±5 at 23 and 48 °C respectively. For micelles formed from an anionic surfactant sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) the electrostatic-induced pKa shift, units of pH, was obtained by subtracting the polarity-induced contribution. This shift yields Ψ= –121 mV electric potential of the SDS micelle surface.

Introduction

Cellular membranes are essential structural elements of all the eukaryotic cells. The membranes are primarily composed of lipids and proteins that are responsible for many aspects of cellular function including cell adhesion, signaling, and transport of ions and other compounds in and out of cells. Many of these functions are thought to be modulated by electrical charges of the lipid headgroups and the associated diffuse double-layer potential that is formed in the aqueous phase adjacent to the membrane. Thus, electrostatic properties of lipid bilayers are considered to be directly involved in such fundamental phenomena as insertion of proteins and viruses into the membranes, formation of DNA-lipid complexes,1 fusion of vesicles and membranes, and electroporation.2 Detailed understanding of these phenomena calls for experimental methods capable of accurately measuring the membrane surface potential at well defined sites.

Currently, only a few analytical methods including NMR,3,4 fluorescent spectroscopy,5–7 and spin probe EPR8–12 could be used for assessing electrostatic properties of the lipid bilayer surfaces. Both fluorescent and EPR methods are based on spectroscopic observation of reversible ionization of molecular probes upon pH titration. These probes are typically placed at the lipid interface offering an advantage of obtaining a spectral readout of the proton-exchange equilibrium directly from that location. The pKa’s of these probes are determined by both local electric potential and the effective interfacial dielectric constant. The latter affects the relative stability of charged and uncharged species. While the fluorescent methods have very low concentration requirements, all the fluorescent pH-indicators for lipid bilayers described to this date are based on relatively bulky easily-polarized aromatic fragments4 that could perturb bilayer interface at least in the vicinity of the probes. In a contrast, nitroxides that are typically employed in spin-labeling EPR studies are smaller and possess lesser dipolar moment than the fluorescence tags. However, conventional nitroxides such as Tempo, Proxyl, or Doxyl derivatives have rather limited sensitivity of magnetic parameters to local electric fields and solvent polarity and do not report directly on the proton exchange equibria.13

Regardless of the detection scheme - optical or EPR – most of the molecular probes for assessing lipid bilayer electrostatic potential reported in the literature are based on an amphiphilic design that positions an ionizable and more polar reporter moiety at the bilayer interface by partitioning a lipophilic tail within the lipids’ acyl chains. For example, the most commonly employed bilayer electrostatic probe - 4-heptadecyl-7-hydroxycoumarin (HHC) – is composed from a lipophilic tetradecyl chain attached to an ionizable coumarin dye.5 The main disadvantage of such partition probes is in somewhat uncertain location of the detecting and/or reporting moieties of the molecular probe with respect to the bilayer interface. For example, the transmembrane location of the most widely used membrane EPR spin probes – n-doxyl-labeled stearic acids – was demonstrated to be pH-dependent.9,12 Such dependence results in changes in EPR spectra and was attributed to reversible protonation of the anchoring site (either COOH or COO– forms).10

Here we describe and characterize two molecular probes for evaluating surface potentials of lipid bilayers that are based on covalent attachment of small pH-reporting nitroxide tags to a phospholipid polar head. Molecular probes of this type mimic the phospholipid structure as close as possible both in the acyl chain and the polar head regions. Therefore, such probes are expected to exert little or any perturbation to lipid bilayer and position the reporter moiety right at the lipid-water interfacial layer. It should be noted here that previously a fluorescent probe fluorescein has been attached to dipalmitoylphosphatidylethanolamine and characterized for measuring the pH-changes at the lipid-water interface.14,15 However, the fluorescein moiety is rather bulky and, as such, is expected to affect the fine balance of molecular interactions at the bilayer interfaces in a larger degree than the nitroxide molecular tags employed here. Also, the protonation state of fluorescein is evaluated through changes in a quantum yield – an experimental parameter that is difficult to measure accurately for optically turbid media such as lipid vesicles.

Currently, among all the spin-labeled phospholipids that are commercially available, only one synthetic lipid - 1,2-diacyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-Tempocholine 1 (Scheme 1) - bears the nitroxide moiety in the lipid’s polar head. Unfortunately, magnetic-resonance parameters of such a lipid-mimicking spin label are not intrinsically sensitive to proton concentration or the bilayer electrostatic potential. To overcome such a deficiency we have employed nitroxides of imidazolidine and imidazoline series that contain protonatable functionalities within the structure. Such nitroxides are known for high sensitivity of the EPR spectrum to pH changes, tunability of the pKa range through introduction of various substituents into the nitroxides’ side chains, and the reversibility of pH effects.16 The only previous record of employing such nitroxides for evaluating the surface potentials and polarity of phospholipid bilayers has been provided by Khramtsov and coworkers who described an imidazolidine derivative that, like fluorescent pH indicator HHC, partitions in lipid bilayers.17 More recently, we have introduced the first thiol-specific pH-sensitive nitroxide spin-label of the imidazolidine series, methanethiosulfonic acid S-(1-oxyl-2,2,3,5,5-pentamethylimidazolidin-4-ylmethyl) ester (IMTSL).

SCHEME 1.

Chemical structure of the synthetic spin-labeled lipid 1,2-diacyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-Tempocholine 1.

While IMTSL has already been proven useful for site-directed spin-labeling EPR studies of proteins and peptides,18,19 its intrinsic pKa≈3.33 after reacting with cysteine or glutathione is rather acidic to warrant a broad range of biophysical applications. Thus, in order to expand the pH range of cysteine-specific EPR labels, we have synthesized a new thiol-specific pH-sensitive nitroxide of the imidazoline series, S-4-(4-(dimethylamino)-2-ethyl-5,5-dimethyl-1-oxyl-2,5-dihydro-1H–imidazol-2-yl)benzyl methanethiosulfonate (IKMTSL) that is being described here.

We also report on the synthesis of spin-labeled phospholipids (SLP) – derivatives of 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphothioethanol (PTE) – with pH-reporting nitroxides that are covalently attached to the lipid’s polar head group. The intrinsic of such lipids in water and in a series of mixed water-organic solutions with various dielectric permittivities were evaluated from EPR titrations of model water-soluble IMTSL– and IKMTSL–2-mercaptoethanol adducts. It is shown that pKa values of such spin probes as well as isotropic nitrogen hyperfine coupling constants, Aiso, are affected by solutions’ bulk dielectric permittivity. The use of these new lipid-mimicking molecular probes for evaluating interfacial pKa’s in neutral and anionic detergent micelles and estimation of the effective interfacial dielectric constant as well as surface electrostatic potential is also reported.

Experimental Section

Materials and Reagents

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) or Acros Organics (Morris Planes, NJ) unless otherwise indicated. 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphothioethanol (>99% pure) was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL) as a chloroform solution and used without further purification. All solvents were reagent grade and used as received.

EPR measurements

X-band (9.5 GHz) continuous wave (CW) EPR spectra were recorded at 23 and 48 °C with a Varian (Palo Alto, CA) Century Series E-109 spectrometer interfaced to a PC. Temperature was maintained with stability better than ±0.02 °C and a gradient below 0.07 °C/cm over the sample region by a digital variable temperature accessory described previously.20 Aqueous solutions were drawn into polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) capillaries (0.81×1.12 mm, NewAge Industries, Inc., Southampton, PA), the capillaries were folded twice and inserted into 3×4 mm clear fused quartz tubes open from both ends (VWR International, West Chester, PA). Typical spectrometer settings were as follows: modulation amplitude was set to a quarter or a half of the narrowest line peak-to-peak line width; time constant, 32 ms; incident microwave power, 2 mW; sweep time, 30 s; scan width, 80 G. Typically, between 10 and 50 individual scans were averaged out. Fast-motion EPR spectra were least-squares simulated using a fast-exchange model with software described earlier.21,22

EPR titration experiments in aqueous medium were carried out with the following set of standard buffer solutions purchased from VWR International (West Chester, PA): (a) potassium tetraoxalate at pH 1.68, (b) hydrochloric acid/glycine at pH 2.0, (c) potassium hydrogen phthalate/hydrochloric acid at pH 3.0, (d) potassium hydrogen phthalate at pH 4.0, e) acetic acid/sodium acetate at pH 4.63, (f) potassium hydrogen phthalate/sodium hydroxide at pH 5.0, (g) potassium hydrogen phthalate/sodium hydroxide at pH 6.0, (h) sodiumphosphate/potassium phosphate at pH 6.86, 7.0, 7.38, and 8.0, (i) boric acid/potassium chloride/sodium hydroxide at pH 9.0, (j) sodium borate at pH 9.18, and (k) sodium bicarbonate/sodium carbonate at pH 10. All buffer solutions contained 0.5% biocide Dowicide A (sodium o-phenylphenate tetrahydrate) and were at a concentration of 50 mM, except the phosphate buffer (pH 6.86) which was at a concentration of 25 mM. These reference buffer solutions are specified to be accurate to at least 0.02 pH unit at 25 °C and deviate from the specified values by not more than 0.05 pH unit at 40 °C. Some measurements were carried out with freshly prepared phosphate buffers. In all experiments pH values were measured with an Orion micro-combination pH electrode 98 Series (Thermo Electron Corporation, Beverly, MA, USA).

For EPR titrations in mixed water-organic solutions, a buffer and iso-propanol were mixed in a chosen proportion (v/v). Then a nitroxide from an aqueous stock solution was added to yield the final concentration of ca. 0.1 mM. It should be noted that for organic solvent-water mixtures the pH-meter readings do not provide a direct measurement of the negative logarithm of the hydrogen ion activities. Thus, the actual pH values for each sample were recalculated by accounting for the dilution factor. Effects of the medium on the activity coefficient of the hydrogen ion23 were estimated to be small and not taken into considerations.

EPR titration experiments in micellar solutions were performed using anionic sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and non-ionic polyoxyethylene isooctylphenyl ether (Triton® X-100) detergents.

For incorporating IMTSL-PTE into Triton® X-100 micelles in a 1:200 lipid-to-detergent ratio a chloroform stock solution of IMTSL-PTE (0.002 g, 2.15×10−6 M) was evaporated at a reduced pressure and then kept in a vacuum desiccator for 4 h. Triton® X-100 detergent (0.278 g, 0.262 mL, 4.3×10−4 M) was added to the vial and the sample was successively heated to 55 °C, sonicated for 15 sec, and vortexed for another 30 sec. This procedure was repeated three more times. The resulting stock solution was kept in a 4 °C refrigerator between the experiments.

A similar procedure was employed for preparing SDS micelles doped with IMTSL-PTE. The chloroform stock solution of IMTSL-PTE (0.001 g, 1.07×10−6 M) was added to a solution of SDS (0.092 g, 3.21×10−4 M) in CH3OH (1.5 ml). The solvents were removed with N2 flow, and the residue was kept in the vacuum dessicator for 8 h. Water (0.15 mL) was added to the solid residue and the resulting mixture was repeatedly sonicated (10 sec) and vortexed (30 sec) until obtaining a transparent solution. The resulting stock solution was kept in the 4 °C refrigerator between the experiments.

In a typical titration experiment, an aliquot of the micellar stock solution was added to a buffer with a chosen pH yielding the final nitroxide concentration of about ca. 0.1 mM.

Synthesis of the spin-labeled lipids

Spin-labeled phospholipids were synthesized through a reaction of 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphothioethanol – a synthetic phospholipid with a thiol-modified phosphatidyl group – with thiol-specific pH-sensitive methanethiosulfonate spin labels. Those included methanethiosulfonic acid S-(1-oxyl-2,2,3,5,5- pentamethylimidazolidin-4-ylmethyl) ester (IMTSL) we have recently reported18,19 and S-4-(4-(dimethylamino)-2-ethyl-5,5-dimethyl-1-oxyl-2,5-dihydro-1H–imidazol-2-yl)benzyl methanethiosulfonate (IKMTSL, Scheme S1, Supporting Information) we have recently synthesized (see Supporting Information for further details). Further throughout the text these spin-labeled lipids will be referenced as IMTSL-PTE and IKMTSL-PTE respectively.

IMTSL-PTE

A solution of IMTSL (0.004 g, 14.2 µM) in a mixture of CH3CN (0.1 ml) and 50 mM phosphate buffer (0.5 ml, pH=6.86) was added to 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphothioethanol, sodium salt (PTE) (0.01 g, 13.7 µM) dissolved in 1 ml of CHCl3. The two-phase reaction mixture was vigorously stirred at room temperature for 24 h. The organic layer was separated, the aqueous phase was extracted with CHCl3 (1×3 ml), and the combined organic extract was separated on a preparative TLC plate (Kieselgel 60 F254) with a mixture of CHCl3 (80 ml), CH3OH (30 ml), and H2O (1 ml) as eluent. The fraction with Rf=0.82 was collected. ESI-HRMS [M−Na+2H]+: calcd for C46H91N2O9PS2 910.5898, found 910.5898.

IKMTSL-PTE

A solution of IKMTSL (0.0054 g, 14.06 µM) in DMSO (0.1 ml) was added to a mixture of a 50 mM phosphate buffer (0.5 ml, pH=6.86) and a solution of PTE (0.01 g, 13.7 µM) in 1 ml of CHCl3. The two-phase reaction mixture was vigorously stirred at room temperature for 48 h. The work-up procedure was similar to that for IMTSL-PTE. The reaction mixture was separated on preparative TLC plate (Kieselgel 60 F254) with a mixture of CHCl3 (140 ml), CH3OH (30 ml), and H2O (1 ml) as eluent. The fraction with Rf=0.48 was collected. ESI-HRMS [M−Na+2H]+: calcd for C53H96N3O9PS2 1013.6314, found 1013.6320.

Labeling of 2-mercaptoethanol

An aqueous solution of 2-mercaptoethanol (0.0544 ml, 7.8 µM) was added to a solution of methanethiosulfonate spin label (7.8 µM) prepared in 0.1 ml of DMSO. The reaction mixture was allowed to stay for 1 h at room temperature and then used for EPR titration experiments without further purification.

Results and Discussion

EPR titration of spin labeled lipids in water-iso-propanol solutions

Prior to employing pH-sensitive phospholipids for evaluating interfacial electrostatic and dielectric properties of detergent micelles, the reference pKa values of these probes in water (intrinsic ) have to be determined. Since the lipids are essentially insoluble in water, a series of EPR titrations of the spin-labeled lipids in water/iso-propanol solutions of various compositions was performed with an intention of extrapolating the titration data to 100% water. Surprisingly, titrations of IMTSL-PTE in 40/60, 50/50 and 60/40 (v/v%) buffer/iso-propanol solutions yielded very close pKa’s of 2.31±0.09, 2.40±0.07, and 2.33±0.07 pH units respectively (see Table 1). We speculate that the most likely reason for such close pKa values is some rearrangement of solvent molecules around the amphiphilic lipid. The most likely reason for such close pKa values could be a discrete dielectric environment experienced by individual amphiphilic spin-labeled lipids in these mixed solvents due the solvophobic effect. It should be noted that while the critical micelle concentration (cmc) for IMTSL-PTE in water is expected to fall into a nano- to micromolar range, the cmc in mixed water/iso-propanol solvents is expected to be significantly higher as it has been shown for surfactants in mixed water/polar organic solvents.24 Thus, formation of micelles and/or micelle-like aggregates at IMTSL-PTE concentrations ca. 0.1 mM in our experiment cannot be excluded a priori. However, such an aggregation of spin-labeled lipids should inevitably result in broadening of EPR signal because of significant spin-exchange and/or dipolar nitroxide-nitroxide interactions. The absence of such a broadening in experimental EPR spectra (not shown) ruled out the possibility of IMTSL-PTE aggregation. Thus, it was concluded that IMTSL-PTE molecules are individually dispersed in mixed water/iso-propanol solvents at iso-propanol concentrations from 40 to 60 volume%. We speculate that in these mixed water/iso-propanol solvents the non-polar acyl chains of the individual IMTSL-PTE molecules could be surrounded by a shell of more hydrophobic, compared to water, iso-propanol molecules with the alkyl fragment pointing towards the acyl chain and the hydroxy groups directed outside. The same way the polar lipid head group and, thus, pH-sensitive nitroxide, could have a preference for more polar water molecules and/or hydroxy groups of iso-propanol. Such a molecular shell is expected to provide about the same dielectric microenvironment for the nitroxide reporter group upon varying the bulk water/iso-propanol ratio resulting only in modest variations in the pKa values (Table 1).

Table 1.

Titration data for IMTSL-PTE in buffer/iso-propanol solutions of various compositions.

| Volume % of iso-propanol |

Bulk εa | AisoR•, G | AisoR•H+, G | Observed pKa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | 55.26 | 15.34±0.02 | 14.24±0.05 | 2.33±0.07 |

| 50 | 48.22 | 15.29±0.02 | 14.23±0.04 | 2.40±0.07 |

| 60 | 40.85 | 15.25±0.02 | 14.19±0.06 | 2.31±0.09 |

Bulk dielectric constants ε of the solutions were estimated according ref. [25].

Overall, it was concluded that EPR titration of spin labeled lipids in water-iso-propanol cannot be used for extrapolating intrinsic of these compounds in water because of possible solute association effects. Thus, we have focused on an alternative strategy of calibrating intrinsic using model compounds.

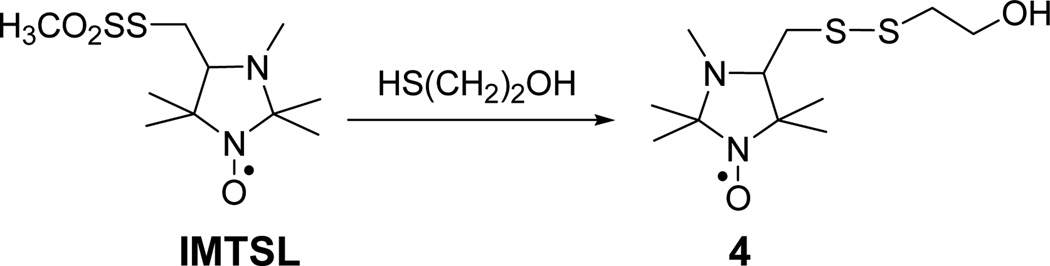

EPR titration of IMTSL-2-mercaptoethanol adducts in water-iso-propanol solutions

Previously, we have shown that both pKa and magnetic parameters of IMTSL are different from those of IMTSL-labeled substrates and that this difference mainly arises from replacing the methanethiosulfonate (MTS) group of IMTSL with the disulfide group.19 Moreover, it was found that other substitutions further away from the label tertiary amino group yield only negligible changes if any. For example, the pKa value of the imidazolidine tertiary amino group of both IMTSL-cysteine adduct and a small unstructured tripeptide glutathione labeled with IMTSL was found to be unaffected by other ionizable groups present in the side chains.19 Thus, we have modeled IMTSL-PTE by synthesizing water soluble IMTSL-2-mercaptoethanol (IMTSL-ME) adduct 4 (Scheme 3). We believe that the hydroxyethyl moiety of the compound 4 is mimicking the inductive effects of the PTE head group attachment rather well and, therefore, the basic properties of the amino functionality are not expected to be altered. Thus, the pKa value of IMTSL-ME in water is expected to provide a close estimate of the intrinsic of IMTSL-PTE. This value was found to be (Table 2) from EPR titrations and was taken for the intinsic of IMTSL-PTE.

SCHEME 3.

Synthesis of the IMTSL-2-mercaptoethanol adduct 4 (IMTSL-ME).

Table 2.

Titration data for 2-mercaptoethanol adduct 4 in the buffer/iso-propanol solutions of various compositions.

| Volume % of iso-propanol |

Bulk εa | AisoR•, G | AisoR•H+, G | Observed pKa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 80.37 | 15.86±0.01 | 14.58±0.01 | 3.33+0.03 |

| 20 | 68.35 | 15.73±0.01 | 14.49±0.02 | 2.77+0.03 |

| 30 | 61.95 | 15.61±0.02 | 14.42±0.03 | 2.58+0.06 |

| 40 | 55.26 | 15.44±0.02 | 14.34±0.04 | 2.27+0.06 |

| 50 | 48.22 | 15.38±0.03 | 14.27±0.05 | 2.14+0.08 |

| 60 | 40.85 | 15.29±0.02 | 14.21±0.04 | 1.77+0.07 |

Bulk dielectric constants ε of the solutions were estimated according ref. [25].

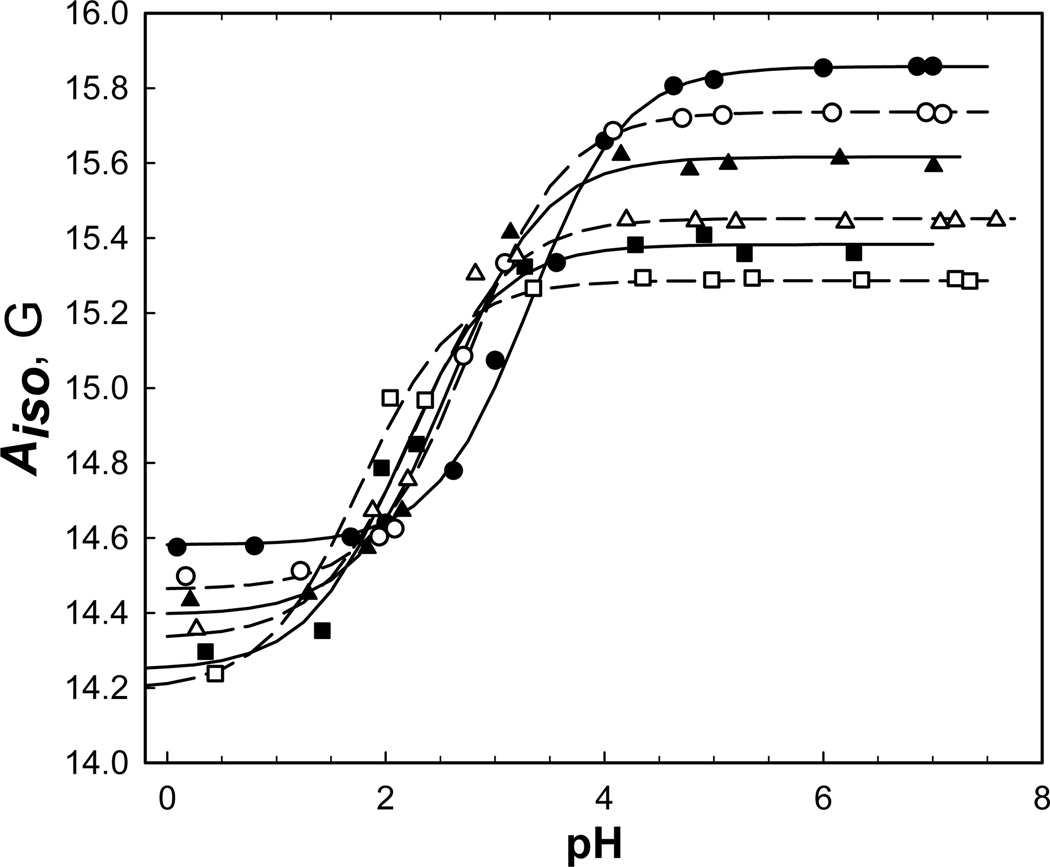

The compound 4 is readily soluble not only in water but also in water-iso-propanol solutions and, therefore, could be used for evaluating effects of the solution dielectric constant on the label pKa. Thus, we have carried EPR titrations for a series of solutions with different volume fractions of water vs. iso-propanol. All X-band (9.5 GHz) spectra of 4 consisted of three well-resolved nitrogen hyperfine coupling components indicating fast rotational motion of the nitroxide on the EPR time scale (Figure 1). Under all experimental conditions no splitting of the high field nitrogen hyperfine component was observed. This is consistent with a fast chemical exchange between protonated and non-protonated forms of the nitroxide. Thus, all the EPR spectra were least-squares simulated as a single nitroxide component in the fast motion limit. Some of the spectra recorded at pH close to the label pKa (such as at pH=3.00 and 3.56 in Fig. 1) showed some small asymmetry of the high field nitrogen hyperfine coupling component. The simulations of such spectra were refined using a two component model and the resulting nitrogen hyperfine coupling constants, Aiso, were averaged out proportionally to the weights of the individual components.19 Aiso determined from such fits are shown in Figure 2. The observed decrease in Aiso upon lowering pH is associated with protonation of the tertiary amine and, therefore, could be fitted to the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation:

| [1] |

where AisoR•H+ and AisoR• are the isotropic nitrogen hyperfine coupling constants for the acidic and the basic forms of IMTSL-ME respectively. These best-fit titration curves are shown as solid and dashed lines in Figure 2 and the best-fit parameters are summarized in the Table 2 and the Figure 3.

FIGURE 1.

Representative room-temperature X-band EPR spectra of IMTSL-2-mercaptoethanol (IMTSL-ME) in a series of 50 mM of buffer solutions of various pH indicated next to the spectra. Vertical dashed lines mark approximate positions of the maximum of the high field nitrogen hyperfine coupling components corresponding to protonated and non-protonated forms of the nitroxide and are given as guides for an eye. Approximate magnitude of the isotropic nitrogen hyperfine coupling constant, Aiso, is shown by an arrow.

FIGURE 2.

Experimental X-band EPR titration data for IMTSL-2-mercaptoethanol adduct 4 measured at T=20 °C in buffer/iso-propanol solutions of the following ratios (v/v): (●) 100:0; (○) 80:20; (▲) 70:30; (△) 60:40; (□) 50:50; (□) 40:60. Solid and dashed lines show the least-squares Henderson-Hasselbalch titration curves (eq. [1]).

FIGURE 3.

Magnetic parameters for non-protonated (○) and protonated (●) forms for IMTSL-2-mercaptoethanol adduct 4 and its pKa (■) vs. mixed solvent bulk dielectric constant ε; corresponding linear regressions are shown as solid lines.

The results of this titration series summarized in the Table 2 and the Figure 3 demonstrate that in a contrast to the IMTSL-PTE the IMTSL-2-mercaptoethanol adduct 4 exhibits a pronounced dependence of the pKa value on the fraction of iso-propanol and associated changes in the bulk dielectric constant ε. Specifically, isotropic nitrogen hyperfine constants Aiso for both the protonated (R•H+) and the non-protonated (R•) forms of the nitroxide gradually increase with ε (Fig. 3). This is in accord with the general trend reported for other nitroxides.27–29 Both Aiso hyperfine constants and pKa values change linearly with ε ranging from 40 to 80 units (Fig. 3).

Previously, analysis of Aiso of various nitroxides has been carried out for both protic and aprotic solvents.26–28 For aprotic solvents the most common is the Onsager dielectric-continuum model of the reaction field that allows for a nitroxide to polarize.26 This model predicts a proportionality of Aiso to (ε −1)/(ε +1).26 Recent reexamination of the experimental data refined this model by accounting for an exponential dependence of the dielectric permittivity on the inverse radial distance from the nitroxide.28 While these models work reasonably well for aprotic solvents, for protic media one has to account for Aiso contributions arising from formation of a hydrogen bond between the oxygen of the nitroxide and the proton donor group of the solvent.28 Parameters of such a bond between a nitroxide and alcohols have been recently determined and were found to be unchanged for four different alcohols studied.29 In aqueous environment including lipid bilayer interfaces the lifetime of such a bond is expected to be small and, therefore, Aiso should be proportional to proton donor concentration. For water/iso-propanol solutions with up to 60 % of iso-propanol by volume the dielectric permittivity is approximately proportional to the iso-propanol volume fraction and, thus, hydrogen bonding contribution to Aiso should change linearly with both iso-propanol volume% and ε. The data in Figure 3 show a linear dependence Aiso on ε, thus, indicating the dominant contribution from transient hydrogen bonding.

Fitting experimentally observed pKa values (Fig. 3) yielded the following linear relationship between the pKa and ε values for IMTSL-2-mercaptoethanol adduct:

| [2] |

This empirical calibration could be used for estimating the effective dielectric constant at the location of the pH-sensitive nitroxide. For example, from pKa measured for IMTSL-PTE lipid in buffer/iso-propanol solutions (Table 1) the effective dielectric permittivity in the vicinity of the nitroxide was determined to be εeff≈56 that corresponds to approximately 60/40 v/v water/iso-propanol solution.

An EPR titration of IKMTSL-2-mercaptoethanol adduct (KMTSL-ME), which was synthesized as a model compound for the second spin-labeled lipid KMTSL-PTE, yielded for aqueous buffers. This value was accepted as the intrinsic of the IKMTSL-PTE lipid (see Table S1 of the Supporting information for details). Similar to IMTSL-ME, the titration of IKMTSL-ME in a series of water-iso-propanol solutions demonstrated a linear pKa vs. ε relationship (not shown) with a= −22.8±8.2 and b=17.3±1.7.

EPR titration of spin labeled lipids in neutral micelles

For an ionizable molecule at the polar/apolar interface such as IMTSL-PTE incorporated into micelles or lipid bilayers, the observed interfacial contains contributions arising from the change in the Gibbs free energy upon transferring the probe from the bulk water into a media with a different electric permittivity, ΔGpol, and the local electric potential Ψ affecting equilibrium of charged and uncharged species, ΔGel. Because pKa= –log10(K), where K is the equilibrium constant of protonation of the nitroxide tertiary amino group, the probe interfacial is given by:5,7

| [3] |

where the electrostatic shift, , is related to the electrostatic surface potential, Ψ, as:

| [4] |

In eq. [4] e is the elementary charge, k is the Boltzman’s constant, and T is absolute temperature.

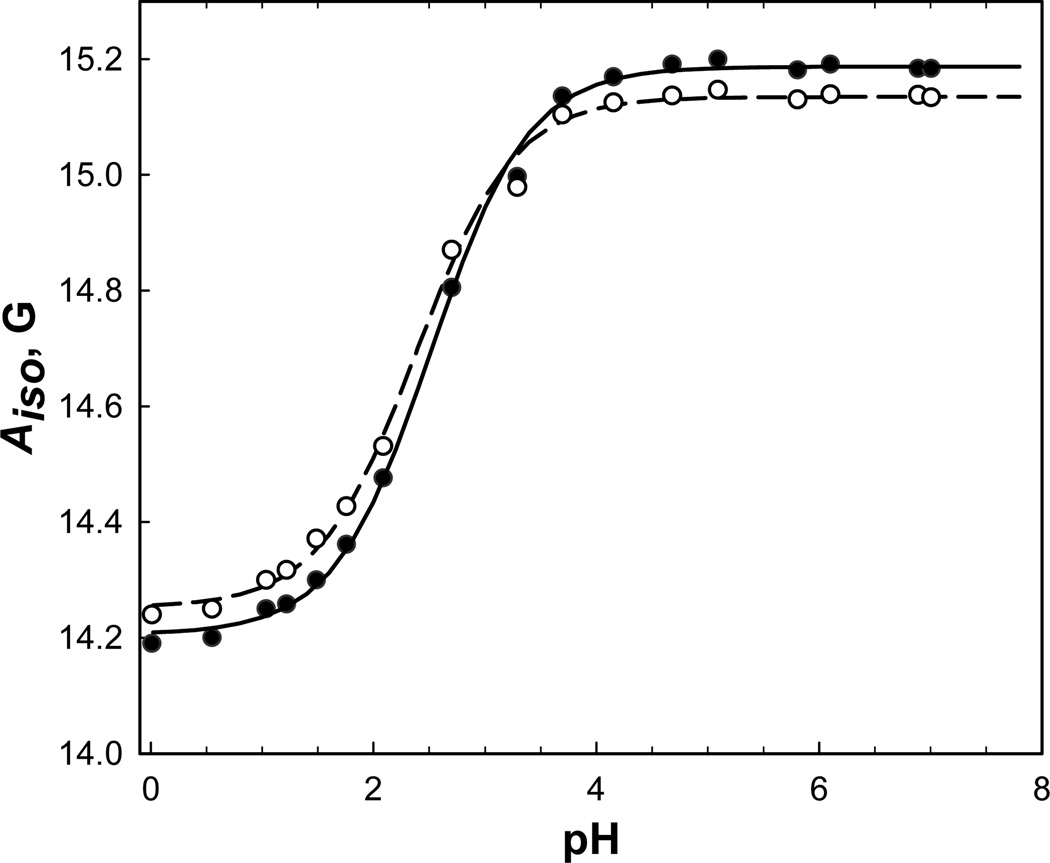

For uncharged interfaces, such as formed by non-ionic surfactants including polyoxyethylene isooctyl phenyl ether (Triton® X-100), the electrostatic shift vanishes and the interfacial deviates from reference in water only by the term. In order to evaluate we have carried out EPR titrations of IMTSL-PTE in the micellar solution prepared from a nonionic Triton® X-100 surfactant. Similar to IMTSL-ME, the EPR spectra of IMTSL-PTE in the Triton® X-100 micelles consisted of three well-resolved nitrogen hyperfine coupling components (e.g., see Figure 4) and no splitting of the high field nitrogen hyperfine component was observed over the entire pH range studied (i.e., from 0.1 to 7.0 units). Thus, the chemical exchange between protonated and non-protonated forms of the nitroxide is fast and the spectra could be simulated as a single nitroxide component. Figure 4 demonstrates that such a model fits the experimental spectra rather well. Nitrogen hyperfine parameters determined from such a fitting were used to derive the interfacial by fitting to the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation [1] (Figure 5).

FIGURE 4.

(A) A representative experimental X-band EPR spectrum of IMTSL-PTE in nonionic micelles formed by polyoxyethylene isooctyl phenyl ether (Triton® X-100) at 23 °C and an intermediate pH=2.62 value that is close to the observed . The best fit to a single component nitroxide spectrum is (B) and (C) is the difference between the simulated and the experimental spectra.

FIGURE 5.

Changes in isotropic nitrogen hyperfine coupling constant Aiso upon EPR titration of IMTSL-PTE in nonionic micelles formed by polyoxyethylene isooctyl phenyl ether (Triton® X-100) at 23 °C (●) and 48 °C (○). Corresponding least-squares fits to the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation [1] are shown as a solid and a dashed line respectively.

Two titration experiments at 23 and 48 °C yielded very close interfacial and 2.39±0.03 units of pH respectively (Table 3 and Fig. 5). These two interfacial values deviate significantly from the intrinsic . For electrically neutral Triton® X-100 such a deviation should be entirely attributed to allowing for estimating effective local dielectric permittivity at the location of the nitroxide from an empirical calibration given by eq. [2] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Titration data for IMTSL-PTE lipid in nonionic Triton® X-100 micelles.

| T, °C | AisoR•, G | AisoR•H+, G |

|

Calculated εeff | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23.00±0.02 | 15.19±0.01 | 14.19±0.01 | 2.52±0.01 | −0.81±0.03 | 60±5 | ||

| 48.00±0.04 | 15.13±0.01 | 14.25±0.01 | 2.39±0.03 | −0.94±0.04 | 57±5 |

Considering a relatively small enthalpy of the proton exchange reaction30 and a weak dependence of magnetic parameters of IMTSL on temperature,19 the small shift in IMTSL-PTE observed between 23 and 48 °C could arise from either a slight dislocation of the spin-labeled lipid with respect to the micelle interface or changes in the effective dielectric constant experienced by the nitroxide. The trends of the isotropic nitrogen hyperfine coupling constant Aiso are in agreement with such an assumption. Indeed, upon increasing temperature the hyperfine constant Aiso of the protonated form of the nitroxide decreases indicating a less polar environment. The latter is consistent with an increased magnitude of fluctuation of the detergent molecules in and out of the micelles and lower dielectric permittivity gradient at the interface. The value of at 48 °C is also lower than at 23 °C indicating an enhanced and a lower dielectric constant. However, the value of Aiso for protonated form of IMTSL-PTE is increasing with temperature indicating a more polar environment. This apparent contradiction could be explained by a dislocation of a charged form of the nitroxide away from apolar micelles: such a dislocation should be facilitated by an increase in local dynamics at higher temperatures.

EPR titration of spin labeled lipids in anionic micelles

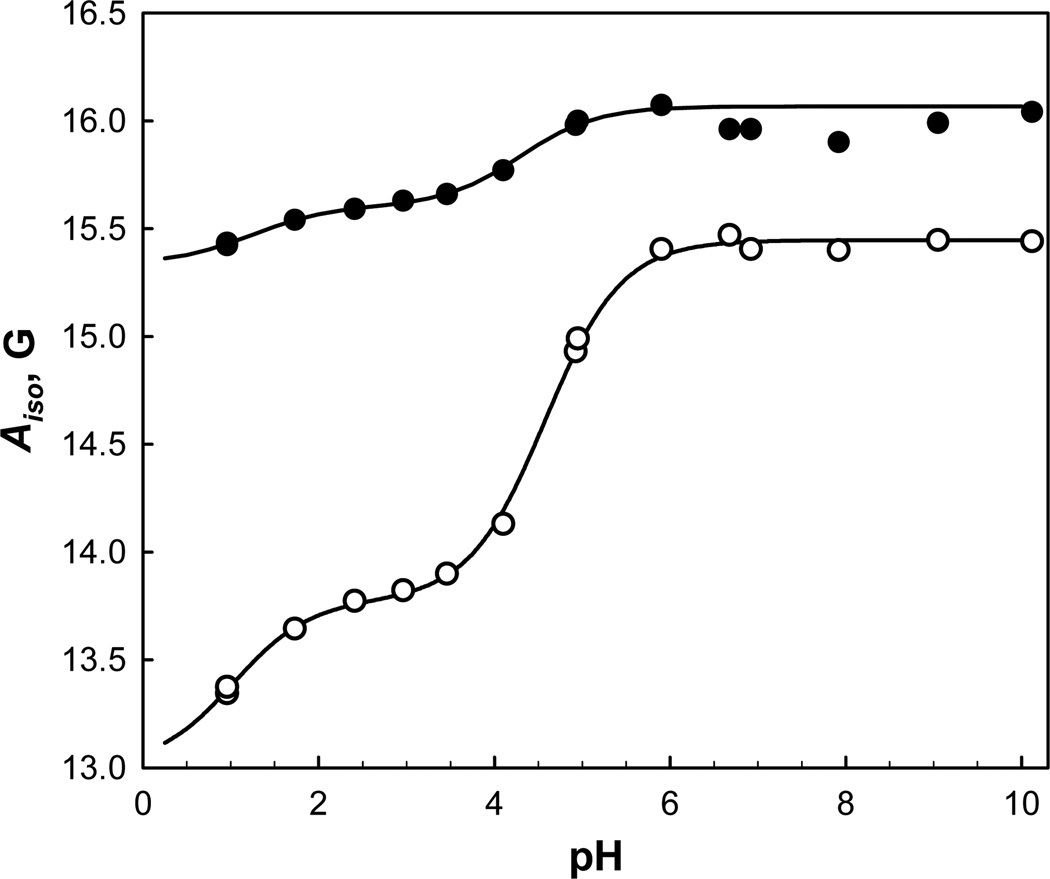

Titration of IMTSL-PTE has been also performed in anionic micelles formed from sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). Contrary to the titration in the neutral micelles, the EPR spectra of IMTSL-PTE in SDS indicated the presence of at least two nitroxide components with line shapes approaching fast motion limit. This model was verified by least-squares simulations of experimental spectra as exemplified in Figure 6. Notably, the two components were present over the entire pH range studied – from 1.0 to10.0 pH units – and, thus, cannot be associated with two forms of IMTSL-PTE undergoing proton exchange. Moreover, a steep decrease of ΔAiso=1.67±0.03 G was observed for the nitrogen hyperfine coupling constants of the major component (>94% of all the EPR intensity for the spectra recorded above pH=5.9) upon lowering pH from 6.0 to 2.4 units (Fig. 7). Such a large change is indicative of protonation of the nitroxide tertiary amino group and is similar to that observed for the 2-mercaptoethanol adduct 4 in buffer/iso-propanol solutions of various compositions (ΔAiso≈1.3 – 1.1 G; Table 2). While the minor nitroxide component also showed some changes in Aiso, the magnitude of ΔAiso=0.47±0.03 G (Table 4 and Fig. 7) was significantly smaller than observed in other experiments for IMTSL-PTE or the model compound 2-mercaptoethanol adduct 4. Thus, we have focused on the analysis of the major nitroxide component (Component 1, Table 4).

FIGURE 6.

(A) A representative experimental X-band EPR spectrum of IMTSL-PTE in anionic micelles formed from sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) at 23 °C and pH=5.00. (B) and (C) are best-fit two nitroxide components and (D) is the difference between the simulated and the experimental spectra.

FIGURE 7.

Changes in isotropic nitrogen hyperfine coupling constant Aiso for the major (○) and the minor (●) components of EPR spectra of IMTSL-PTE upon titration of anionic micelles formed from dodecyl sulfate (SDS). Corresponding least-squares fits to the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation modified for two pKa’s are shown as solid lines.

Table 4.

Titration data for IMTSL-PTE lipid in anionic SDS micelles at T=23.0±0.02. °C.

| Aiso,1R•,G |

Aiso,1R•H+, G |

|

|

Aiso,2R•H+, G |

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component1 | 15.45±0.02 | 13.78±0.03 | 4.58±0.04 | 2.06±0.04 | 13.00±0.32 | 1.0±0.3 | |||

| Component2 | 16.07±0.02 | 15.60±0.02 | 4.28±0.07 | n/a | 15.34±0.07 | 1.2±0.3 |

In a contrast to the titration of Triton® X-100 micelles, the Aiso data for SDS revealed an additional smaller transition at low pH≈1 values. We speculate that the latter change in Aiso originates from an additional repartitioning of the protonated form of IMTSL-PTE into the more hydrophobic phase. As the phosphatidyl group turns neutral upon protonation the nitroxide bearing a positive charge would be attracted closer to the negatively charged micelle surface by the electrostatic forces. The very low ΔAiso=13.35±0.05 G is indicative of a nitroxide transfer to a low dielectric environment and that is in agreement with such a hypothesis. Note, that uncharged Triton® X-100 micelles do not offer such an opportunity and, therefore, the second transition is absent in the EPR titration data (Figure 5).

Because of two transitions present, the ΔAiso data for SDS titration were fitted to a modified Henderson-Hasselbalch curve that accounts for two pKa’s. The corresponding curves are shown as solid lines in the Figure 7 and the titration data are summarized in the Table 4. Assuming that IMTSL-PTE in SDS micelles resides in a dielectric environment similar to that of Triton® X-100 micelles, the observed difference in pKa for these two micelle types should arise solely from the negative potential on the SDS surface. The same assumption has been employed by Fernández and Fromherz for calibrating coumarin-based fluorescent pH indicators.5 Then from eq. [3] and the pKa data at 23 °C from Tables 3 and 4 the electrostatic-induced pKa shift is units of pH. From eq. [4] one obtains an electric potential of Ψ= −121 mV for SDS micelles. This value is within 15% of that measured by fluorescent hydroxycoumarin indicators31,32 and fits well into the Ψ=−76 to −144 mV range obtained by using other colored dyes and fluorescent pH-indicators33 although some less realistic values such as Ψ=−180 mV have been also reported.34 Such discrepancies in the Ψ values have been noticed previously by other authors and were attributed to the nature of the indicator dyes and the non-ionic surfactants employed.33 The difference in the electric potential values could also be attributed to some uncertainties in the probe calibration as well as to a difference in the locations of the EPR and the fluorescent pH indicators with respect to the micelle interface.

Conclusions

Synthesis and initial EPR characterization of a phospholipid labeled at the polar head group with pH-sensitive nitroxides is being reported for the first time. The pKa values of these lipids measured by EPR titration in aqueous buffer/iso-propanol solutions of various compositions were found to be essentially the same – pKa≈2.35 – indicating that in mixed aqueous/organic solvents the amphiphilic lipid molecules could be shielded from changing bulk conditions by a local shell of co-solvent molecules. Thus, in order to overcome this problem of calibrating the spin-labeled lipid pKa vs. bulk dielectric permittivity of protic solvents two water-soluble adducts of 2-mercaptoethanol and methanethiosulfonate spin labels IMTSL and IKMTSL were synthesized. Using these model compounds the intrinsic for IMTSL-PTE and IKMTSL-PTE were estimated as 3.33±0.03 and 5.98±0.03 respectively. Further, the latter compounds allowed for calibrating polarity-induced pKa shifts, , which arise from the change in the Gibbs free energy upon transferring the probes from the bulk water into a protic media with a different electric permittivity, vs. bulk dielectric permittivity of the mixed water/iso-propanol solvents. These calibration data allowed for ascertaining the local dielectric constant experienced by the reporter nitroxide of the IMTSL-PTE lipid incorporated into the nonionic Triton® X-100 micelles. Specifically, EPR titrations of such micelles at 23 and 48 °C yielded interfacial that were lower than the intrinsic for IMTSL-PTE by −0.81 and −0.94 units of pH, respectively. Such polarity-induced shifts, , yielded effective dielectric permittivity constants at the probe location as 60±5 and 57±5, respectively at these two temperatures. For charged micelles, such as formed from anionic surfactant dodecyl sulfate (SDS), electrostatic-induced pKa shift, , was obtained by subtracting the polarity-induced contribution. For IMTSL-PTE the former shift was determined to be units of pH which corresponds to Ψ= −121 mV electric potential of the SDS micelle surface. This Ψ value is within 15% of those measured previously by fluorescent lipoid pH indicators.5 Such similarity of EPR and fluorescence measurements provides a further validation of the method presented here. Remaining difference in the electric potential values could be attributed to some uncertainties in the probe calibration as well as to a difference in location of the EPR and the fluorescent pH indicators with respect to the micelle interface.

Overall, a method to assess interfacial electrostatics and polarity of micelles and similar assemblies of amphiphilic molecules based on EPR of pH-reporting nitroxides tethered directly to the lipid polar heads has been developed. It is speculated that the small molecular volume and amphiphilic nature of the nitroxide tag could be advantageous for ascertaining interfacial electrostatic properties of lipid bilayers.

Supplementary Material

SCHEME 2.

An illustration of spin-labeling of the PTE phospholipid and chemical structures of thiol-specific methanethiosulfonate nitroxides IMTSL and IKMTSL.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health grant 1R01GM072897 to AIS.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Synthetic procedures for the methanethiosulfonate spin label IKMTSL, titration data for IKMTSL-2-mercaptoethanol adduct (IKMTSL-ME), and pKa vs. ε correlation plot for the IKMTSL-2-mercaptoethanol adduct in water-iso-propanol mixtures of various composition. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Gelbart WM, Bruinsma RF, Pincus PA, Parsegian VA. Phys. Today. 2000;53:38–44. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipowsky R, Sackmann E, editors. Structure and Dynamics of Membranes. Handbook of Biological Physics. Vol. 1 Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cafiso D, McLaughlin A, McLaughlin S, Winiski A. Methods Enzymol. 1989;171:342–364. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(89)71019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crowell KJ, Macdonald PM. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1416:21–30. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(98)00206-5. and references cited herein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernandez MS, Fromherz P. J. Phys. Chem. 1977;81:1755–1761. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rottenberg H. Methods Enzymol. 1989;171:364–375. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(89)71020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fromherz P. Methods Enzymol. 1989;171:376–387. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(89)71021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marquezin CA, Hirata IY, Juliano L, Ito AS. Biophys. Chem. 2006;124:125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barratt MD, Laggner P. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1974;363:127–133. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(74)90011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanson A, Ptak M, Rigaud JL, Gary-Bobo CM. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 1976;17:435–444. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(76)90045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonnet P-A, Roman V, Fatome M, Berleur F. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 1990;55:133–143. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sankaram MB, Brophy PJ, Jordi W, Marsh D. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1990;1021:63–69. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gullá AF, Budil DE. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2001;105:8056–8063. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thelen M, Petrone G, O’Shea P, Azzi A. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1984;766:161–168. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(84)90228-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soucaille P, Prats M, Tocanne JF, Teissie J. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1988;939:289–294. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(88)90073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khramtsov VV, Volodarsky LB. In: Use of Imidazoline Nitroxides in Studies of Chemical Reactions: ESR Measurements of the Concentration and Reactivity of Protons, Thiols, and Nitric Oxide, in Biological Magnetic Resonance, Spin Labeling: The Next Millennium. Berliner LJ, editor. Vol. 14. New York: Plenum Press; 1998. pp. 109–180. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khramtsov VV, Marsh D, Weiner L, Reznikov VA. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1992;1104:317–324. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(92)90046-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smirnov AI, Ruuge A, Reznikov VA, Voinov MA, Grigor’ev IA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:8872–8873. doi: 10.1021/ja048801f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Voinov MA, Ruuge A, Reznikov VA, Grigor’ev IA, Smirnov AI. Biochemistry. 2008;47:5626–5637. doi: 10.1021/bi800272f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alaouie AM, Smirnov AI. J. Magn. Reson. 2006;182:229–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smirnov AI, Belford RL. J. Magn. Reson., Ser. A. 1995;113:65–73. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smirnova TI, Smirnov AI, Clarkson RB, Belford RL. J. Phys. Chem. 1995;99:9008–9016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harned HS, Owen BB. The Physical Chemistry of Electrolyte Solutions. 3rd edn. New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagarajan R, Wang C-C. Langmuir. 2000;16:5242–5251. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Åkerlöf G. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 1932;54:4125–4139. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griffith OH, Dehlinger PJ, Van SP. J. Membr. Biol. 1974;15:159–192. doi: 10.1007/BF01870086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marsh D. J. Magn. Reson. 2008;190:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gagua AV, Malenkov GG, Timofeev VP. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1978;56:470–473. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smirnova TI, Smirnov AI, Pachtchenko S, Poluektov OG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:3476–3477. doi: 10.1021/ja068395v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olofsson G, Hepler LG. J. Solution Chem. 1975;4:127–143. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lovelock B, Grieser F, Healy TW. J. Phys. Chem. 1985;89:501–507. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hartland GV, Grieser F, White LR. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 1987;83:591–613. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mchedlov-Petrossyan NO, Vodolazkaya NA, Yakubovskaya AG, Grigorovich AV, Alekseeva VI, Savvina LP. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2007;20:332–344. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ikeya A, Okada T. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2003;264:496–501. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9797(03)00473-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.