Abstract

Interaction of pharmaceutical companies (PC) with healthcare services has been a reason for concern. In medicine, awareness of the ethical implications of these interactions have been emphasized upon, while this issue has not been highlighted in dentistry. This study undertook a cross-sectional rapid assessment procedure to gather views of dentists in various institutions towards unethical practices in health care and pharmaceutical industry. The purpose of this study was to assess the need for the formulation and implementation of guidelines for the interaction of dentists with the pharmaceutical and device industry in the best interest of patients.

A group of 209 dentists of Lahore including faculty members, demonstrators, private practitioners and fresh graduates responded to a questionnaire to assess their attitudes and practices towards pharmaceutical companies’ marketing gifts.

The study was conducted during 2011 and provided interesting data that showed the pharmaceutical industry is approaching private practitioners more frequently than academicians and fresh graduates. Private practioners accepted the gifts but mostly recognized them as unethical (over 65%). Both groups considered sponsoring of on-campus lectures as acceptable (over 70%).

Respondents are not fully aware of the ethical demands which are imperative for all health care industries, and there is a dire need of strict guidelines and code of ethics for the dentist’s interaction with the pharmaceutical and device industry so that patient interest is protected.

Keywords: Attitude, practice, Pharmaceutical companies, Dentists, Marketing gifts

Introduction

The global pharmaceutical industry has grown at a tremendous pace reaching up to $956 billion and is expected to rise to nearly $1.2 trillion in 2016, representing a compound annual growth rate of 3–6 percent the world over (1). With this aggressive growth and ever increasing competition the marketing strategies of pharmaceutical and some dental/medical equipment companies are becoming ethically questionable (2–4). Although the pharmaceutical industry is sponsoring a lot of research worldwide, the major portion of their budget is allocated to promotional activities (4, 5). The usual promotional activities are obliging doctors by minor gifts, like stationery items, donating equipments, kits and even invitations for dinners, or sponsoring participation in seminars and training programs. This brings about a conflict between the physician’s financial interest and the welfare of the patient (4–13).

In medicine, awareness of the ethical implications of such gifts has been raised for the past few decades and a code of ethics has been formulated for interaction between medical practitioners and pharmaceutical companies. In dentistry, the need to realize the ethical implications of such interactions is greater than medicine because of the more active involvement of device industry and material manufacturers. The interactions of dentists include those with pharmaceutical, biotech, medical device and research equipment industry. Interactions with these industries can be positive if kept above reproach (14). However, with the growing competition amongst the pharmaceutical industry, device industry and material manufacturers, the unethical marketing practices are also growing.

The present study was undertaken to assess the attitudes and practices of fresh dental graduates, faculty members and private practitioners in dentistry towards pharmaceutical gifts, and consequently the need for implementation of guidelines and a code of ethics in the dental fraternity in Pakistan. Another purpose of this study was to assess the difference in perception of fresh graduates, residents, faculty members and private practitioners.

Method

The study sample included dentists of various categories: fresh graduates, residents/demonstrators, faculty members and private practitioners. The assessment tool was a questionnaire that was designed based on previously published studies in India (15) and Norway (16). It was handed out at various teaching and training dental institutions, clinics and dental conferences, and was filled in anonymously. The data was collected from October 2011 to December 2011. The teaching & training institutions included in this study were de’ Montmorency College of Dentistry, Sharif Medical and Dental College, Lahore Medical and Dental College and Fatima Memorial Dental College and Hospital. The sample size for each category selected was based on the expected representative size. All the data was compiled and analyzed using Microsoft Excel (Windows 7) and SPSS (version 17). For testing significance, since the data was predominantly qualitative in nature, Chi square test was applied at a P value of 0.05 or less.

Results

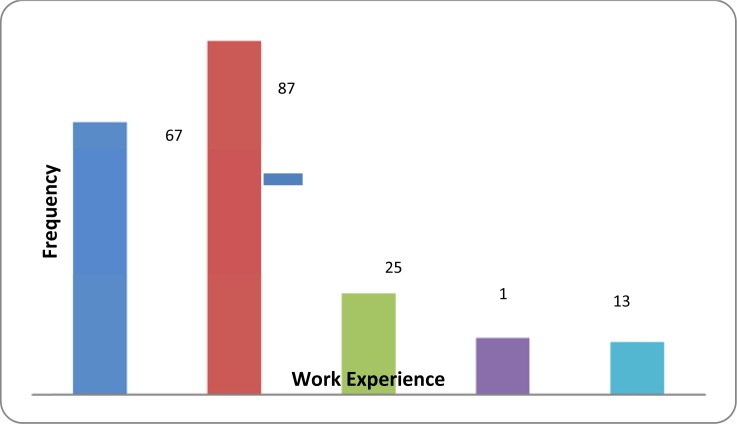

A total of 220 participants were requested to fill a study instrument, 209 (95 %) completed it and were included for data analysis. The participants included fresh graduates (FG), demonstrators (D), faculty members (FM) and private practitioners (PP) working in dentistry. The demographic data of the study participants are summarized in table 1 and Figure 1.

Table 1.

Demographic data of study participants

| Category (Dentist) | Respondents | Data completed |

|---|---|---|

| Fresh graduates | 70 | 67 |

| Demonstrators | 90 | 87 |

| Faculty members | 30 | 26 |

| Private practitioners | 30 | 29 |

| Total | 220 | 209 (95%) |

| Gender (n=209) | ||

| Male | 98 | 46.9% |

| Female | 111 | 53.1% |

| Age (years) | ||

| < 30 | 74 | 35.4% |

| >30 | 135 | 64.6% |

Fig. 1.

Work experience of study participants

The response of the four different groups to the pharmaceutical representative (PR) is shown in tables 2 and 3. It appeared that private practitioners (PP) were more frequently contacted by the PRs. During the previous 3 months, 89.6% of PPs had been visited as compared to 62.8% of faculty.

Table 2.

Response outcome of participants of the academic group

| Views/Responses | Fresh graduates n=67 | Demonstrators n=87 | Faculty n=26 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Interaction with pharmaceutical representatives in the last 3 months | 43 (64.1%) | 54 (62.0%) | 16 (61.5%) |

| 2 | Gifts offered | 43 (64.1%) | 54 (62.0%) | 13(50.0%) |

| 3 | Gifts accepted | 31 (46.2%) | 41 (47.0%) | 6 (23.0%)* |

| 4 | Considering accepting gifts unethical | 39 (58.2%) | 61 (70.1%) | 24 (92.3%) |

| 5 | Gifts affect prescription | 31 (46.2%) | 39 (44.8%) | 2 (7.6%)* |

| 6 | Allowing PRs to arrange on campus lectures | 57 (85.0%) | 61 (70.1%) | 17(65.3%) |

| 7 | Receiving honorarium for a lecture acceptable | 44 (65.6%) | 51 (58.6%) | 11 (42.3%)* |

| 8 | Considering pharmaceutical interaction as useful | 58 (86.5%) | 67 (78.1%) | 19 (73.0%) |

These values were statistically significant

Table 3.

Response outcome of participants of the academic and private groups

| Views/Responses | Academic group (n=180)* | Private practitioners (n=29) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Interaction with pharmaceutical representatives in the last 3 months | 113 (62.8%) | 25 (89.6%) | <0.05 |

| 2 | Gifts offered | 110 (61.1%) | 22 (75.8%) | <0.05 |

| 3 | Gifts accepted | 78 (43.3%) | 20 (69.0%) | <0.05 |

| 4 | Considering accepting gifts unethical | 124 (69.0%) | 19 (65.5%) | >0.05 |

| 5 | Gifts affect prescription | 72 (40.0%) | 12 (41.3%) | >0.05 |

| 6 | Allowing PRs to arrange on campus lectures | 135 (75.0%) | 21 (72.4%) | >0.05 |

| 7 | Receiving honorarium for a lecture acceptable | 106 (59.0%) | 15 (55.1%) | >0.05 |

| 8 | Considering pharmaceutical interaction as useful | 144 (80.0%) | 22 (75.8%) | >0.05 |

These values were statistically significant

A similar trend was observed in the offering of gifts, with the highest percentage of gifts being offered to private practitioners (over 75%) as against 61.1% to fresh graduates, demonstrators and faculty members. When gifts were offered, the PPs accepted in higher proportion (69.0%) than faculty (43.1%).

From the ethical point of view of accepting gifts, a very high percentage (92%) of faculty members declared that accepting gifts from pharmaceutical industry was unethical while 58.2% of fresh graduates, 70.1% of demonstrators and 65% of private practitioners considered the acceptance of gifts as unethical.

The academic group included fresh graduates, demonstrators and teaching faculty. An interesting observation was that almost 69% of private practitioners accepted gifts from the PRs but 65% of them considered it unethical at the same time. This shows a clear contrast in their actions and opinions. An average of 44% of the fresh graduates, demonstrators and private practitioners revealed that their prescriptions were affected by their interaction with the PRs while only 7.6% of the faculty members considered their interaction with PRs to affect their prescribing habit.

It was interesting to note that both fresh graduates and demonstrators were offered gifts and accepted them in the ratio of 1.4: 1, while the academic staff accepted gifts to a lesser degree, the ratio between gifts offered and accepted being 2.2: 1.0. In the additional question on commenting about the gift as ethical or unethical, the academic group by far declared them as unethical and the ratio of labeling it as unethical was faculty: demonstrators: fresh graduates: 1.6: 1.2: 1. In terms of accepting and declaring it as unethical, the academic staff provided a ratio of 4 declaring unethical: 1 accepting. This ratio was much narrower in the other groups.

In the entire study group 75% of the subjects who were offered gifts accepted them, and acceptance of gifts affected 40% of the prescribing practice.

Discussion

This study gave an insight on the impact of pharmaceutical industry’s interaction with dental surgeons at various levels from fresh graduates to faculty members and private practitioners. Historically, pharmaceutical industry has been trying to influence doctors’ prescribing habits and has often not adhered to ethical principles (17). In dentistry, interaction with device industry and material manufacturers is also a necessary evil along with the pharmaceutical industry. This renders a dentist more susceptible to their marketing strategies than a physician (13). Pharmaceutical industry exploits the fact that long term habits are developed early in a doctor’s career, so they make special efforts to stay in constant touch with the fresh graduates and students along with the senior members of the dental fraternity (18). These efforts of the pharmaceutical industry create a conflict of interest in ethical practices (8–12).

The pharmaceutical industry seems to focus significantly more on private practitioners than on fresh graduates, demonstrators or the faculty members of different teaching institutions. Private practitioners showed the highest percentage of accepting gifts offered to them and they also appeared to disregard the ethical considerations, and their approach was mainly more focused on the business and commercial aspects of their relationship with the pharmaceutical industry. In comparison, faculty members were offered 10% less gifts than private practitioners, while their gift acceptance rate was almost 63% less than private practitioners. This contrast in percentage of accepting gifts can be attributed to the difference in the level of education of private practitioners and faculty members, since most of the private practitioners are general dentists while faculty members invariably have some postgraduate qualification. According to a study, physician response to the pharmaceutical industry may vary by practice settings. A more ethically aware environment in a university setting leads to better ethical practices, while professional isolation of private practice may lead to being influenced by the information provided by the pharmaceutical representatives (19). This trend was also reported in a very recent study conducted in Libya (20).

The results showed some confusing responses especially in fresh graduates and demonstrators who accepted gifts regardless of considering them as unethical. This finding is similar to one of the recent studies in which it was concluded that although physicians understood the concept of conflict of interest, their interaction with the pharmaceutical industry led to psychological dynamics that influenced their reasoning (2).

In some of the earlier studies, however, no statistically significant differences were found in the responses of the faculty members and residents (5). Such trends probably indicate inadequacies in the training and curricula in terms of professional ethics.

One limitation of the present study was an absence of control over the validity of the responses since it could not be ascertained whether the respondents were trying to project certain concepts or simply report their actual practices. True evaluation for built-in validity assessment could be a blend of knowledge, attitudes and practices.

The majority of fresh graduates, demonstrators and private practitioners seemed to have their prescribing habits affected by gifts; however, only a very small percentage of faculty members appeared to be influenced by gifts. This difference can again be attributed to the latter’s academic qualifications and their awareness of ethical implications.

On the other hand, all the four groups considered their interaction with the pharmaceutical industry as useful. This finding is also similar to results from previous studies (21).

The present study highlights the need for regulations to be imposed by the government, but laws alone cannot reinforce ethical practice, and physicians themselves need to abstain from the negative commercial influences of marketing (22).

Conclusion

The present study indicates lack of awareness on ethical implications of interaction with the pharmaceutical industry in the undergraduate and postgraduate training. Pakistan Medical and Dental Council has laid clear guidelines on interaction with the pharmaceutical industry, but unfortunately most of the medical and dental graduates are unaware of even the existence of such a document. These guidelines should be updated with the changing trends and implemented at all levels in the noble profession of health care. Continuing dental education should also have an ethical component and Pakistan Medical and Dental Council should implement a mandatory component on ethics for renewal of practicing license in order to reinforce ethical considerations periodically.

Acknowledgments

Authors are grateful to Mr. Muneeb Rehmat of Fatima Memorial College of Medicine & Dentistry for his help when required.

References

- 1.Anonymous. IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. The Global use of Medicines: Outlook Through 2016. Report by the IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics 2011.

- 2.Chimonas S, Brennan TA, Rothman DJ. Physicians and drug representatives: exploring the dynamics of the relationship. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(2):184–90. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0041-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodwin MA. Medicine, Money, and Morals: Physicians Conflict of interest. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gagnon MA, Lexchin J. The cost of pushing pills: a new estimate of pharmaceutical promotion expenditures in the United States. PLoS Med. 2008;5(1):e1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wazana A. Physicians and the pharmaceutical industry: is a gift ever, just a gift? JAMA. 2000;283:373–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chimonas S, Rothman DJ. New federal guidelines for physician pharmaceutical industry relations: the politics of policy formation. Health Aff. 2005;24(4):949–60. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.4.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Studdert DM, Mello MM, Brennan TA. Financial conflicts of interest inphysician relationships with the pharmaceutical industry: self-regulation in the shadow of federal prosecution. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1891–900. doi: 10.1056/NEJMlim042229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brett AS, Burr W, Moloo J. Are gifts from pharmaceutical companies ethically problematic? A survey of physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2213–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.18.2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgan MA, Dana J, Loewenstein G, Zinberg S, Schulkin J. Interactions of doctors with the pharmaceutical industry. Med Ethics. 2006;32:559–63. doi: 10.1136/jme.2005.014480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brodkey AC. The role of the pharmaceutical industry in teaching psychopharmacology: a growing problem. Acad Psychiatry. 2005;29:222–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.29.2.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gülöksüz S, Oral ET, Ulaş H. Attitudes and behaviors of psychiatry residents and psychiatrists working in training institutes towards the relationship between the pharmaceutical industry and physicians. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2009;20(3):236–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Margolis LH. The ethics of accepting gifts from pharmaceutical companies. Pediatrics. 1991;88:1233–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiodo GT, Tolle SW, Donhoe MT. Ethical issues in the acceptance of gifts: part 2. Gen Dent. 1999;47(4):357–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anonymous. Policy and Guidelines for Interactions between Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry and Pharmaceutical, Biotech, Medical Device and Research Equipment Supplies Industry (Industry) Approved at the Joint Schulich Council / ECSC meeting on June 4, 2010

- 15.Sharma V, Aggarwal S, Singh H, Garg S, Sharma A, Sharma R. Attitudes and practices of medical graduates in Delhi towards gifts from the pharmaceutical industry. Indian J Med Ethics. 2010;7(4):223–5. doi: 10.20529/IJME.2010.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lea D, Spigset O, Slørdal L. Norwegian medical students' attitudes towards the pharmaceutical industry. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;66(7):727–33. doi: 10.1007/s00228-010-0805-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Komesaroff PA, Kerridge IH. Ethical issues concerning the relationships between medical practitioners and the pharmaceutical industry. Med J Aust. 2002;176:118–21. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Austad KE, Avorn J, Kesselheim AS. Medical students' exposure to and attitudes about the pharmaceutical Industry: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2011;8(5):e1001037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson BL, Silverman GK, Loewenstein GF, Zinberg S, Schulkin J. Factors associated with physicians' reliance on pharmaceutical sales representatives. Acad Med. 2009;84(8):994–1002. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ace53a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alssageer MA, Kowalski SR. A survey of pharmaceutical company representative interactions with doctors in Libya. Libyan J Med. 2012:7. doi: 10.3402/ljm.v7i0.18556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fischer MA, Keough ME, Baril JL, et al. Prescribers and pharmaceutical representatives: why are we still meeting? J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(7):795–801. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0989-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grande D. Limiting the influence of pharmaceutical industry gifts on physicians: self-regulation or government intervention? J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):79–83. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1016-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]