Abstract

The chlorite dismutases (Clds) degrade ClO2− to O2 and Cl− in perchlorate respiring bacteria, and they serve still poorly defined cellular roles in other diverse microbes. These proteins share 3 highly conserved Trp residues, W155, W156, and W227, on the proximal side of the heme. The Cld from Dechloromonas aromatica (DaCld) has been shown to form protein-based radicals in its reactions with ClO2− and peracetic acid. The roles of the conserved Trp residues in radical generation and in enzymatic function were assessed via spectroscopic and kinetic analysis of their Phe mutants. The W155F mutant was the most dramatically affected, appearing to lose the characteristic pentameric oligomerization state, secondary structure, and heme binding properties of the WT protein. The W156F mutant initially retains many features of the WT protein but over time acquires many of the features of W155F. Conversion to an inactive, heme-free form is accelerated by dilution, suggesting loss of the protein’s pentameric state. Hence, both W155 and W156 are important for heme binding and maintenance of the protein’s reactive pentameric structure. W227F by contrast retains many properties of the WT protein. Important differences are noted in the transient kinetic reactions with peracetic acid (PAA), where W227F appears to form an [Fe(IV)=O]-containing intermediate, which subsequently converts to an uncoupled [Fe(IV)=O + AA+.] system in a [PAA]-dependent manner. This is in contrast to the peroxidase-like formation of [Fe(IV)=O] coupled to a porphyrin π-cation radical in the WT protein, which decays in a [PAA]-independent manner. These observations and the lack of redox protection for the heme in any of the Trp mutants suggests a tendency for protein radical formation in DaCld that is independent of any of these conserved active site residues.

Introduction

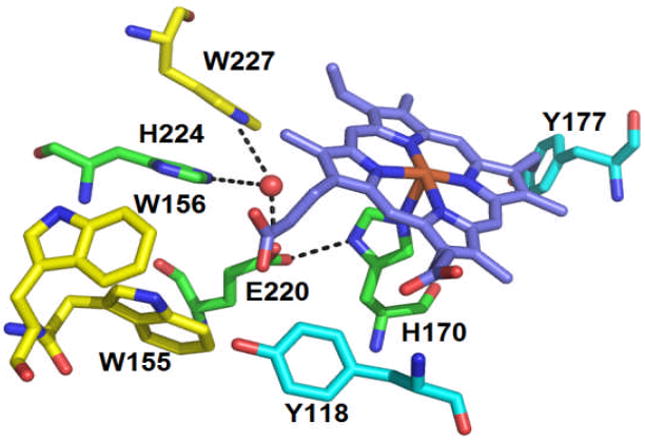

Chlorite dismutases (Clds) are heme-binding proteins identified in diverse species across the bacterial and archaeal kingdoms. These proteins were first discovered in perchlorate respiring proteobacteria, where they are essential for detoxifying chlorite (ClO2−), this pathway’s metabolic end product. They do so by catalyzing the conversion of chlorite (ClO2-) to O2 and Cl−, a reaction which involves the biologically unusual formation of an O–O bond. The reaction occurs at a His-ligated 5-coordinate high spin heme (Fig 1).

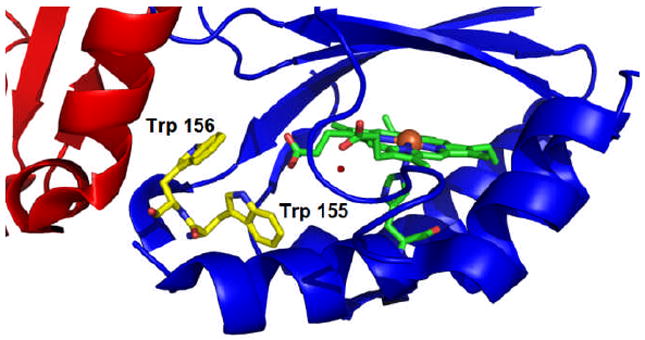

Fig. 1.

Proximal pocket of WT DaCld, with hydrogen bonding interactions indicated by dashed lines. The possible redox active residues are represented in carbon yellow (Trps) and in carbon cyan (Tyrs). The water molecule is represented as a red sphere. The figure was constructed from PDB 3Q08 using PyMOL (www.pymol.org).

Prior work using chlorite dismutase from Dechloromonas aromatica (DaCld) has shown that the protein can catalyse ~20,000 turnovers before irreversibly inactivating.1 Spectroscopic studies (see below) suggested that inactivation might occur via a pathway involving protein-based radicals, leading ultimately to porphyrin scission without observed formation of verdoheme.2 This observation was notable since the catalytic mechanism for O2 generation is not expected to involve radicals on the one hand, and since blocking radical formation might be a way to stabilize the useful chlorite-degrading and O2-generating capabilities of the catalyst on the other. DaCld possesses several potential redox active amino acids which could be involved in radical formation. These include 4 tryptophans (W33, W155, W156, and W227) and 8 tyrosines (Y64, Y82, Y118, Y136, Y143, Y177, Y186 and Y199). Of these, three tryptophans and two tyrosines are located on the proximal side and within 5 Å of the heme (Fig. 1). W155 is a strictly conserved residue in both chlorite-degrading bacteria and the broader Cld protein family as a whole, whereas W156 is only conserved in the chlorite-degrading bacteria. W227 is conserved in most chlorite decomposing bacteria, but not the entire Cld family.3 In the crystal structure of DaCld4, W227 is on the proximal side of the heme, where it appears to π-stack with H224. It is part of a H-bonding network, including the proximal H170, H224, E220, and a water molecule that is clearly discernible even in the 3.1Å resolution structure (Fig. 1). W155 and W156 are more distant from the porphyrin and do not appear to make direct hydrogen bonding contact with it or H170. However, it is possible that they could be connected to it or one another via water molecules that are not visible in the 3.1Å structure. For example, in the Cld from Nitrobacter winogradskyi, the residue corresponding to W155 is hydrogen bonded to a heme propionic side chain via a water molecule, which could also be present in DaCld (See Fig. S8 and ref 35).

Protein-based radicals have been previously observed but not extensively characterized in DaCld. Following exposure of DaCld to a large excess of chlorite, electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy indicated the presence of a protein radical.5 Further, in reactions of DaCld with peracetic acid (PAA) under second order conditions, a transient ferryl porphyrin π-cation radical intermediate was observed ([FeIV=O Por+.] or Compound I). This decayed to a second intermediate that appeared by UV/Vis to be either 1) a ferryl heme with a protein-based amino acid radical, ([FeIV=O AA+.], exchange coupled, referred to here as Compound ES, or [FeIV=O + AA+.], uncoupled) or 2) a ferryl heme ([FeIV=O], referred to as Compound II).2 The Soret band for this second intermediate bleaches immediately, an observation associated in other heme proteins with radical-mediated heme lysis.2

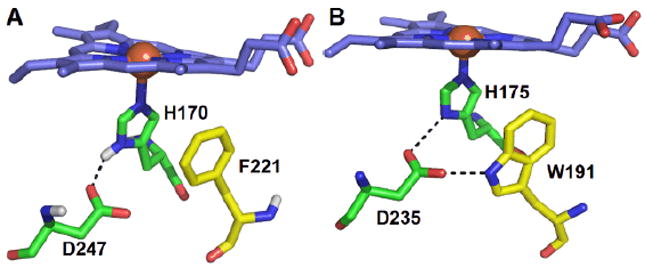

Compound I, II, and ES intermediates have been extensively characterized in peroxidases. Following addition of one equivalent of H2O2, most peroxidases, including the well-studied horseradish peroxidase (HRP), form Compound I.6-8 In contrast, in cytochrome c peroxidase (CcP), one molecule of H2O2 generates the isoelectronic Compound ES intermediate, which is an exchange-coupled-[FeIV=O Trp+.] (Fig. 2B).9 Either intermediate is capable of two sequential one-electron reductions of substrates, returning the heme to the ferric starting state. Sequence alignments and crystal structures have shown that most peroxidases, including HRP, have a phenylalanine at the analogous position of the radical-bearing Trp (Fig. 2A). Phe like Trp has an aromatic side chain but is incapable of stabilizing an analogous radical. Hence, these peroxidases do not form [FeIV=O AA+.] as part of their regular catalytic cycle. By contrast, the ascorbate peroxidase from soybean cytosol possesses a Trp residue at a location analogous to Trp191 in CcP.10 However, even though it may appear to be structurally poised to do so, this Trp is not observed to form a stable radical, and evidence suggests that the protein reacts via Compound I.10-12

Fig.2.

Proximal pockets of (A) HRP and (B) CcP from yeast. The iron is represented as an orange sphere. Figure generated using PyMOL (www.pymol.org) and from PDB 1ATJ13 and 2CYP14.

Several structural features appear to facilitate the formation of Compound ES. First, the indole ring of the Trp-bearing radical in CcP is close and parallel to the proximal histidine ligand, potentially supporting π-π interaction. Second, a hydrogen bonding network allowing for an e- transfer pathway is generally important for stabilizing the radical further away from the porphyrin ring. W191 in the yeast CcP is hydrogen bonded directly to D235, which in turn connects it to the proximal H175 (Fig. 2B). In the simplest case, if the residue that sustains the Compound ES radical is replaced by a structurally similar residue having a higher oxidation potential (e.g., Phe), Compound ES should be inaccessible. However, delocalization of the radical across other Trp/Tyr residues is also possible. Hence, substitution of the ES-associated Trp may not necessarily prevent the formation of a different protein-based radical upon reaction with H2O2.

DaCld does not have a Trp proximal to the heme in the site analogous to the CcP Compound ES-associated Trp. However, one or more of the three Trps close to the heme in DaCld could potentially have a role in intermediate formation. Of the Trp residues in the heme pocket, W227 lies closest to the heme and appears from the crystal structure to exhibit the most H-bonded connectivity with the proximal His. Thus, we hypothesized that if DaCld were to form a ferryl-Trp radical species analogous to CcP Compound ES, W227 would be the most likely radical site. W155 could likewise sustain a radical, particularly if a water molecule not visible in the crystal structure links it to the heme. Wherever initially formed, a radical could delocalize to the other nearby tryptophans or tyrosine in Fig. 1, or beyond. The work described here aims at determining the roles of the highly conserved tryptophan residues in DaCld, both in radical formation and in maintaining the stability of the protein. Prospective roles as radical sites have been probed by substituting each Trp with a phenylalanine (Phe), an aromatic residue whose side chain cation radical is not known to be accessible in ferryl heme proteins. The mutants were characterized via a combination of catalytic, kinetic, thermodynamic, and spectroscopic (UV/Vis, EPR, and resonance Raman (RR)) methods.

Experimental

Overexpression and purification

The WT DaCld gene was previously cloned into the pET41a expression vector in its mature, signal-peptide-free form and mutated here. Site directed mutagenesis was carried out using a QuikChange kit (Stratagene) and the following primers and their reverse complements, where the mutagenic codons are underlined: 5‘ AAA TTC CAC GTT CGC TTT GGC AGT CCG 3‘, 5’-AAG AAA AAC GCG GAA TTT TGG AAC ATG-3’, 5’-AAG AAA AAC GCG GAA TGG TTT AAC ATG TCG-3’ for W227F, W155F and W156F, respectively. Cultures of E. coli TunerDE3 cells containing the mutant plasmids were grown and the proteins purified as previously described.1 Soluble proteins were obtained for all three mutants.

To determine an approximate molecular weight for the mutant proteins and to ascertain their integrity, analytical gel filtration was carried out using a 1.6 × 18 cm column (S-200 Sephacryl, GE) run at 0.4 mL/min using 0.1 M potassium phosphate pH 7 at 4 °C. A mixture of standards (BioRad) was used to generate a standard curve: bovine thyroglobuline, bovine γ-globuline, chicken ovalubumine, horse myoglobin and vitamin B12 (molecular weight of 670 kDa, 158 kDa, 44 kDa, 17 kDa and 1.35 kDa respectively).

Circular dichroism (CD)

CD spectra were measured on a JASCO-815A CD spectropolarimeter. The protein solutions (3 μM in DaCld-monomer) were prepared in a 100 mM phosphate buffer at pH 6.8. In order to maintain a low background, a voltage below 600 V was applied. Spectra (50 nm/min and digital integration time per data of 1s, 20 °C) were measured from 190-250 nm for buffer to obtain a baseline, and on 1 mL solutions of 3 μM DaCld (WT or mutant). Scans were repeated 3 times and averaged. The data from 200-240 nm were fit using the web-based K2D2 software.15 This program predicts protein secondary structure from UV circular dichroism spectra using a Kohonen neural network with a 2-dimensional output layer.

UV/Visible spectroscopy

UV/Visible pH titrations were performed using a Varian Cary 50 spectrometer with temperature control from a Peltier cooler (25 °C). The pH titrations were carried out as previously described.16 Briefly, small volumes of NaOH or HCl (1M standard solutions) were added to a solution of 2 μM enzyme in 0.1 M citrate-phosphate buffer until the desired pH was reached. To determine pKa values, the Soret band maxima from each data set were plotted as a function of pH. Each data set was fit to one or two sigmoidal curves of the form AbsSoret = Absmin + (Absmax-Absmin)/(1+(pH/pKa)H)17 (H = Hill coefficient). Data plots and fits were made using Kaleidagraph software.

Equilibrium binding of heme ligands

Equilibrium binding constants for a set of anionic, cationic, and neutral ligands were determined at 100 mM phosphate, pH 7, 25 °C. The weak acid hydrogen cyanide (HCN, pKa = 9.2), is predominantly neutral at this pH. Imidazole (pKa = 7.0) is an equal mixture of the imidazolium cation and neutral imidazole. Finally, the weak bases azide (N3−) and fluoride (F−) carry a negative charge. The equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) for each ligand/protein pair were calculated by fitting plots (Kaleidagraph) of the Soret band maxima as a function of ligand concentration to equation 1, the equilibrium isotherm appropriate for weakly binding ligands:

| (1) |

Here L0, Et, KD, and ΔAmax are the initial ligand concentration, total enzyme or protein concentration, the equilibrium dissociation constants, and the maximum change in absorbance, respectively.

Chlorite dismutase activity

Chlorite dismutase activity was measured by monitoring the production of O2 on a Clark-type O2 electrode (Yellow Springs, International) at two pHs (6 and 8) and at 4 °C. The concentration of chlorite was varied and the initial rates of production of O2 were determined. The reactions were carried out in a continuously stirred 1.5 mL volume of chlorite-containing buffers (0.1 M citrate-phosphate buffer) and initiated with 5 μL of the enzyme (10 nM final in [heme]) via gas-tight syringe. Initial rate data were plotted versus [chlorite] and fit to the Michaelis Menton equation (Kaleidagraph).

Inactivation and turnover number measurement

Measurement of turnover numbers was performed as previously described.1 Briefly, enzyme solutions were incubated with increasing molar ratios of chlorite and the reactions allowed to go to completion (40 min). Enzyme concentrations were kept high in order to minimize losses of activity associated with dilution. The samples were buffer exchanged using dialysis cups (Slide-A-Lyzer mini dialysis unit, 10K MWCO, Pierce) for two 2h cycles to eliminate the chlorite and to exchange the proteins into fresh 100 mM phosphate buffer (4 °C). The remaining specific activity was measured at 4 °C, pH 6.8 using 2.4 mM chlorite and the above-described assay. The percent of residual activity retained was measured and plotted as a function of [chlorite]/[enzyme] and the data fit to a straight line. The fit extrapolated to 0% residual activity gives the turnover number.

Transient kinetics of reactions with peracetic acid

Reactions of WT and mutant DaCld with peracetic acid (PAA) were carried out on a Hi-Tech SF-61DX2 stopped-flow system at 20 °C in citrate/phosphate buffer (100 mM/200 mM mixture) at pH 6 and pH 8. All experiments used 2 μM DaCld monomer with varying concentrations of peracetic acid (50, 100, 250 and 500 μM after mixing). PAA stocks were made immediately prior to use. Three measurements were averaged.

Apparent rate constants (kobs) were determined by fitting one or a sum of two exponential curves to absorbance versus time data at several wavelengths using the KinetAssyst software from TgK Scientific or Kaleidagraph. Second-order rate constants were determined under pseudo-first order conditions (≥10x PAA relative to DaCld monomer) from the slope of kobs versus PAA concentration. The y-intercepts equal koff.

Resonance Raman spectroscopy

DaCld(W227F) samples (20 μM) for the pH titration were prepared in 100 mM citrate at pH 5.8, 100 mM sodium phosphate at pH 6.8 and 7.5, 100 mM Tris/HCl at pH 8.5, and 100 mM Ches at pH 10.0. The OD- and 18OH- derivatives of DaCld(W227F) were prepared from a concentrated stock protein solution at pH 6.8. A 20 μL sample was exchanged into 100 mM Tris/HCl pH 8.8 buffer prepared in H218O (96 atom % 18O) or 100 mM Tris/HCl pD 9.2 prepared in D2O (99.9 atom % D). Resonance Raman spectra were obtained with 406.7 nm excitation from a Kr+ laser, using the 135° backscattering geometry. The spectrometer was calibrated against Raman frequencies of toluene, dimethyl formamide, and acetone. Data were collected at ambient temperature from samples in spinning 5-mm NMR tubes. Laser power at the samples ranged from 6 to 18 mW. Data for W227F reacted with PAA were collected in 15 s acquisitions.

Electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy

20 μM DaCld and peracetic acid (10-20-fold excess) in 200 mM phosphate buffer at pH 5.8 or 7.9 were mixed at 4 °C and flash frozen in an acetone slush bath (−95 °C). Uncertainty in the quench times for these samples is estimated at ±1 s. X-band EPR spectra were recorded at 77 K using a Varian E9 spectrometer. The spectra were referenced to 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) in a frozen toluene glass.

Results

Overexpression and general properties

The W156F and W227F mutant proteins were overexpressed and purified in a manner similar to WT.1 For W155F, two protein fractions elute at 650 min and 900 min from the second, gel filtration column (Fig. S1). The first peak is present routinely and corresponds to endogenous E. coli proteins which are produced during the expression of both WT and mutant DaCld. The latter peak corresponds to W155F mutant protein with an apparent MW of 54 kDa based on the standard curve, which could correspond to a dimer (monomer MW = 28.4 kDa) (Fig S1). Moreover, the heme content was found by the pyridine hemochrome assay to be exceptionally lower than in WT or the other mutants (0.06 heme/monomer versus >0.5 heme/monomer) indicating almost no heme incorporation. The W155F mutation therefore appears to disturb both the relatively higher heme affinity and pentameric oligomerization state common to the WT, W156F, and W227F DaClds.

Structural integrity of mutant DaClds

CD spectra for the mutants are shown in Fig. S2. Each spectrum has a maximum at 210 nm and a shoulder at 220 nm. Simulations of the WT spectrum using the K2D2 software indicated that the protein contains 39% alpha helix, 15% beta sheet, and 46% turns, loops, or disordered segments. This simulation compares favourably to the secondary structure identified in the X-ray crystal structure (36% helix, 27% beta sheet, and 37% turns/loops/disordered). The same simulation program predicted helix, sheet, and turns/loops/disordered populations of 31%, 17%, and 52% for W156F; 24%, 23%, and 53% for W227F; and 85%, 1%, and 14% for W155F. These results, in conjunction with analytical gel filtration, are suggestive of largely maintained secondary and tertiary structures for the W156F and W227F mutants. The secondary and tertiary structure of W155F, by contrast, appears compromised, and the protein fails to stably bind heme.

Heme coordination in DaCld Trp mutants

To gain an understanding of how the coordination environment of the heme changes as a function of pH, UV/visible pH titrations of the three mutant proteins from low to high pH were carried out. Protein samples were initially equilibrated to pH 6 (Fig. 3), at which WT DaCld assumes a 5-coordinate high spin (5cHS) form. This species converts to a 6-coordinate low spin (6cLS) form with a pKa of 8.9.16 The same transition was apparent in the rR data, which further demonstrated definitively that the alkaline species was a ferric-hydroxide complex.16

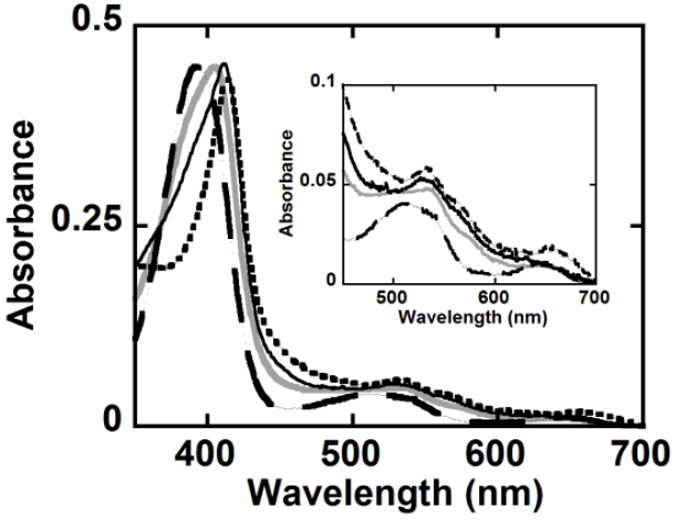

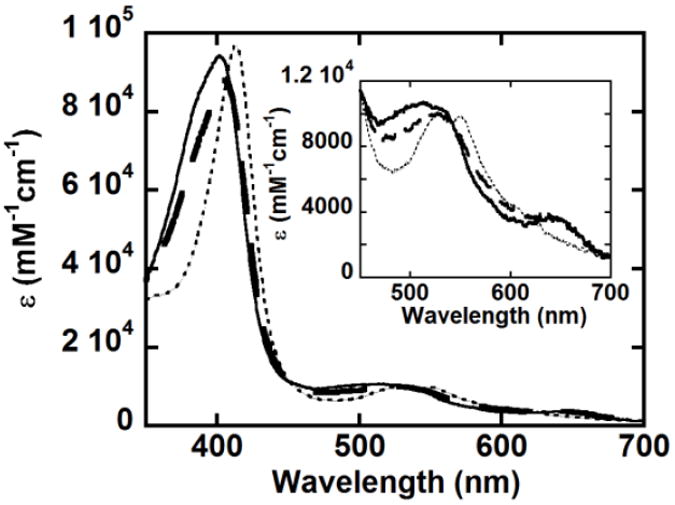

Fig. 3.

Mutation of Trp residues causes changes in the coordination of the DaCld heme. UV/Visible spectra at pH 6 of WT DaCld (

), W227F (

), W227F (

), W156F (—) and W155F (

), W156F (—) and W155F (

) in 100 mM phosphate buffer at 25 °C are shown. The inset shows the visible bands on an expanded scale.

) in 100 mM phosphate buffer at 25 °C are shown. The inset shows the visible bands on an expanded scale.

W227F

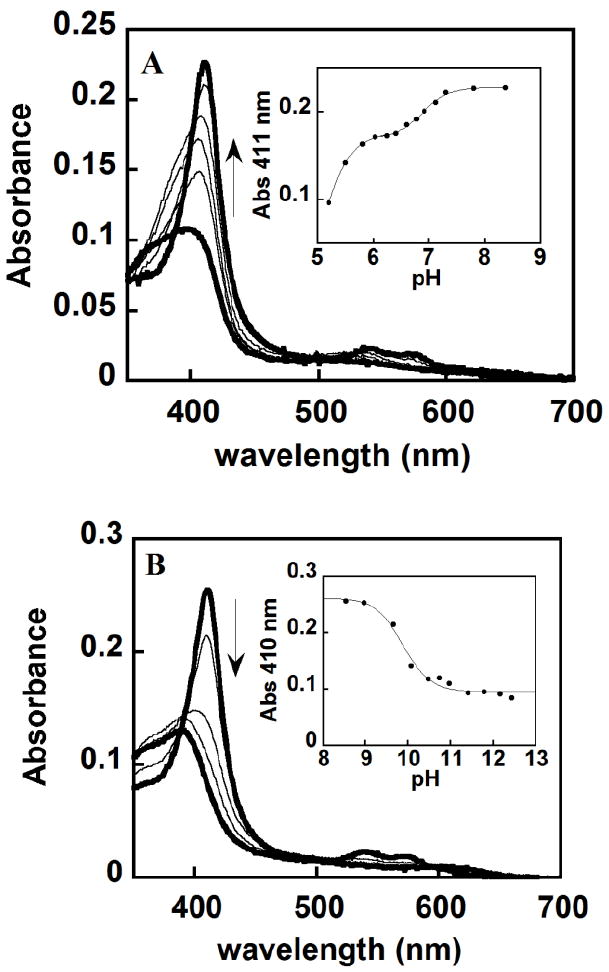

The protein is catalytically active between pH 5.2 ± 0.1 and 9.9 ± 0.02, the midpoints of two irreversible pH transitions at which the Soret absorbance decreases and blue shifts. These spectral changes are suggestive of heme loss from the protein. A single reversible transition in the UV/visible spectrum was observed between pH 5.2 and 9.9. From pH 6 to 6.8, the protein has a Soret band at 402 nm, visible (α, β) bands at 538 nm and 576 nm, and a charge transfer (CT) band at 650 nm (Fig. 3 and 4, Table 1). While resembling a five coordinate high spin (5cHS) species in the visible region, the red shifted Soret band (relative to the 5cHS acidic form of WT DaCld) may indicate the presence of some six coordinate (6c) complex. Above pH 6.8, the Soret absorbance maximum shifts to 409 nm and the α/β bands to 538/570 nm, giving a spectrum reminiscent of the six coordinate low spin (6cLS) alkaline species observed for the WT DaCld (Soret λ = 412 nm; α/β bands at 540 and 575 nm; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

W227F pH titrations showing a reversible alkaline transition (pH 6.9) and irreversible loss of heme with midpoints at pH 5.2 and 9.9. (A) Spectra at pH 5.2, 5.5, 5.8, 6.6, 7.1 and 8.4 are shown. (B) Spectra at pH 8.9, 9.7, 10, 10.9 and 12.4 are shown. The two extreme pHs for both titration are represented with a thick black line. Insets show the fitting of two (A) or one (B) sigmoidal curve. A Hill coefficient of 1 was found for each fit, indicating no evidence of allosteric interactions among the DaCld monomers.

Table 1.

Spectroscopic characteristics of DaCld: WT, W227F, W155F and W156F at pH 6 (top) and pH 8 (bottom)

| Enzyme | λ Soret | ASoret/A380 | CT1 | α/β | Spin state | Rz = A280/ASoret |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 393 | 1.1 | 509, 648 | 5cHS | 0.89 | |

| W227F | 402 | 1.35 | 650 | 538 | 6c/5cHS | 0.63 |

| W156F | 411 | 1.57 | - | 534 | 6cHS/LS | 1.68 |

| W155F | 413 | 2.43 | 660 | 6cLS | 2.7 | |

|

| ||||||

| WT | 400 | 1.1 | 509, 652 | 535 | 5cHS | 0.89 |

| W227F | 409 | 1.35 | 650 | 540, 576 | 6c/LS | 0.63 |

| W156F | 412 | 1.37 | 650 | 535, 575 | 6c/LS | 1.68 |

| W156F | 413 | 2.43 | 660 | 535, 565 | 6c/LS | 2.7 |

Absorbance at the Soret maximum was plotted versus pH and fit to a sigmoidal curve, yielding an alkaline transition at pH 6.9 ± 0.02 (Fig.4). This transition is shifted 2 pH units lower in this mutant relative to the WT protein, indicating that the Trp/Phe substitution at this position preferentially stabilizes the ferric-hydroxy complex. Such stabilization could be due to the loss of W227’s contribution to the hydrogen bonding network (Fig. 1) that modulates the imidazolate character of the proximal H170 ligand. Weakening of the interaction between Glu220 and His170 results in less imidazolate character in the latter. The trans effect of a less basic His170 would strengthen heme iron interactions with ligands (including hydroxide) on the opposite face of the porphyrin.

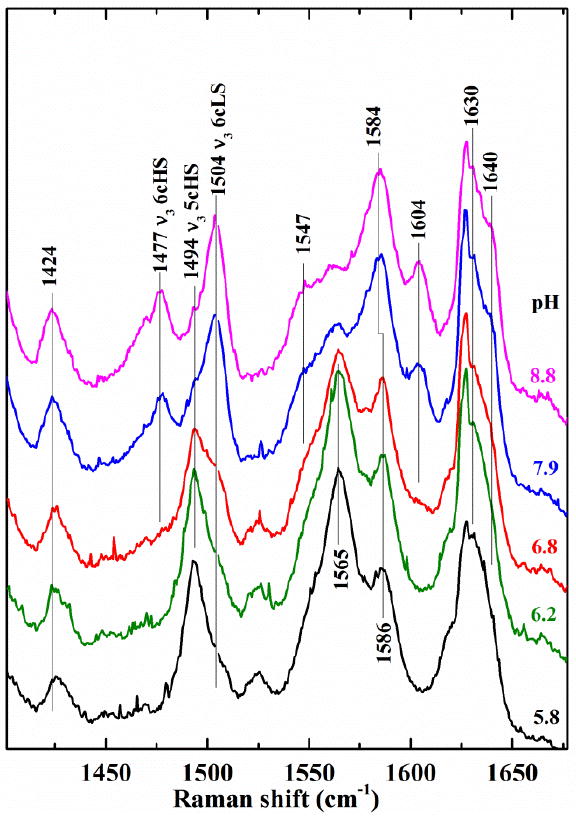

Resonance Raman data measured at multiple values of pH agree with the UV/vis data and their interpretation. In the high frequency RR spectrum of W227F, the transition from 5cHS to the 6c alkaline form is readily observed via the change in the ν3 frequency; it shifts from 1494 cm-1 at pH 5.8 to 1504 and 1477 cm-1 for the 6cLS and 6cHS forms of the heme, respectively, at pH 6.8 (Fig. 5). The low pH ν3 frequency is the same as that previously observed for WT, and both hydroxide complex values are 2 cm-1 lower than the comparable frequencies for WT DaCld. The transition is also evidenced in the appearance of ν10 (1640 cm-1 for 6cLS), ν11 (1547 cm-1 for 6cHS), and the shift of ν2 (1586 to 1584 cm-1) above pH 6.8. These observations are consistent with the pKa determined from the spectrophotometric UV-visible titration.

Fig. 5.

High frequency resonance Raman of DaCld(W227F) measured as a function of pH suggest a transition to a ferric hydroxide near pH 6.8. Excitation frequency of 406.7 nm.

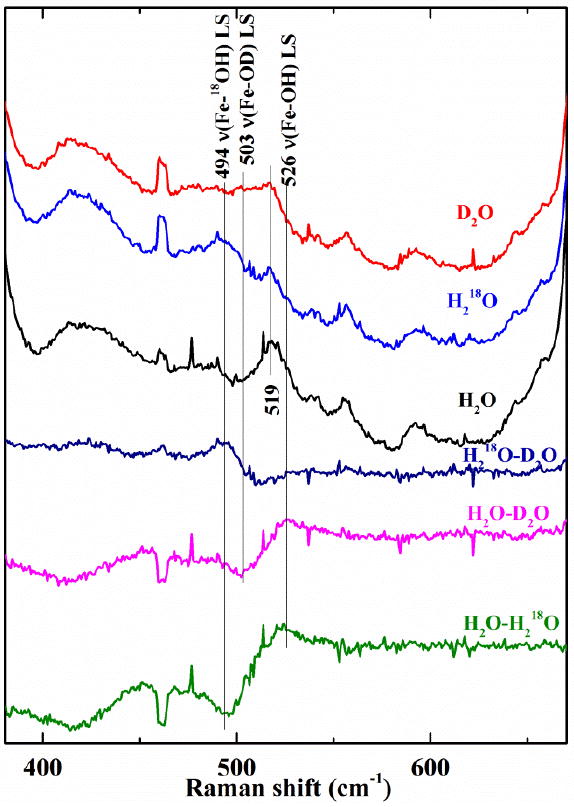

The iron-hydroxide stretching mode for the 6cLS W227F-OH species is readily identified by isotopic substitution experiments (Fig. 6). The ν(Fe-OH) stretch for the 6cLS complex is observed at 526, 503, and 494 cm-1 in H2O, D2O, and H218O, respectively. This ν(Fe-OH) stretching frequency is 12 cm-1 higher than that of WT. The ν(Fe-OH) for the 6cHS hydroxide complex is not as obvious. It appears to be quite broad (between 400 and 480 cm-1) and is consequently difficult to detect in the difference spectrum.

Fig. 6.

Isotope data for DaCld(W227F) at pH 8.8 further confirm the identity of the alkaline species as a low spin ferric-hydroxide. The top three spectra of the three isotopomers (D2O, red; H2 18O, blue; and H2O, black) were used to generate the difference spectra shown below. Laser excitation, 406.7 nm

Insofar as the stretching frequency reflects the Fe-O bond strength, these data indicate that the Fe-OH bond is stronger in W227F than in WT. The increase in Fe-OH frequency suggests that the H-bond network disruption weakens the H-bonding available to the proximal His, thereby decreasing its imidazolate character relative to WT. As the proximal His-Fe bond strength decreases, the Fe-OH bond strength increases, in a manner analogous to the inverse correlation for ν(FeIV=O) with respect to ν(FeII-His) reported for other heme proteins and iron porphyrinates.18

W156F

At pH 6, W156F appears to exist as a mixture of 6c/HS-LS species, according to its broad Soret band at 411 nm, a visible band at 535, and a shoulder at 566 nm (Fig. 3). This mixed 6cHS/6cLS species transitions to an apparent 6cLS complex with increasing pH (Fig. S3). The broad visible band shifts to 565 nm and the Soret band narrows and shifts to 413 nm. As with W227F, a pKa appears to exist between pH 6-7 but was difficult to measure precisely due to the small interval over which the titration could be done. The spectrum of the alkaline species resembles that for the WT DaCld alkaline form (a 6cLS ferric-hydroxide). Above pH 7, the Soret absorbance decreases steadily in intensity with pH, apparently due to heme loss from the protein. This irreversible process has its midpoint at pH 8.5, a remarkably low threshold compared to WT or W227F.

W155F

Spectrophotometric Titrations were performed from pH 5 to 11. The spectra were unchanged outside of large decreases in the Soret absorbance at acidic and alkaline pH (irreversible titration midpoints at 5 and 9.1), consistent with heme loss from the protein. Within the range over which the protein binds heme, W155F has UV-visible features characteristic of a 6cLS species with a red shifted Soret band at 413 nm and α/β bands at 534 and 565 nm, again suggestive of a ferric-hydroxide. The ratio ASoret/A380 is a good indicator of the amount of 5cHS species (the lower the ratio, the higher the proportion of 5cHS).19 Based on this criterion, the proportion of 5cHS species at pH 6 follows the order: WT > W227F > W156F > W155F (Table 1). This suggests that W227F is the most like WT in stabilizing an open coordination position at which an oxidant might bind and react.

Equilibrium binding of ligands

The binding of ligands was monitored via UV/vis absorbance difference spectra. KD values measured at pH 7 are reported in Table 2. This pH is near or below the pKa for the alkaline transition for W227F and W156F and ~2 pH units below the transition for WT DaCld. Each protein should therefore exist to some degree in its acidic 5cHS form. Ligand affinities were not determined for W155F due to its minimal incorporation of heme. Generally, the affinities of the W227F and W156F mutants for each ligand are similar to those measured for WT DaCld. This suggests that the electronic structure of the iron and/or access to the distal pocket are not dramatically altered by these mutations at this pH. The slightly higher affinity of W227F for anions is consistent with the decreased pKa of its alkaline transition to form the ferric-hydroxide.

Table 2.

KD (μM) values for WT, W227F, W156F with ligands demonstrating their varying affinity at pH 7.

| Ligand | WTDaClda | W227F | W156F |

|---|---|---|---|

| KCN | 4 | 10.2 ± 0.5 | 24.9 ± 7.8 |

| Imidazole | 9.6 ± 0.3 | 17.5 ± 1.5 | 26.6 ± 3.5 |

| N3- | 8.3 ± 0.1 | 7.0 ± 0.3 | 34.5 ± 3.1 |

| F- (103) | 15 ± 1 | 3.8 ±0.9 | 110 ± 30 |

WT values are from ref 16

Effect of Trp mutations on chlorite decomposition

To evaluate the roles of W227, W156, and W155 in catalysis, a steady-state analysis of their activities utilizing a polarographic O2 electrode to monitor the oxygen produced from chlorite dismutation was carried out. No chlorite dismutase activity was observed for W155F. Table 3 shows the steady state catalytic parameters for the decomposition of chlorite for the acidic (primarily 5cHS) and alkaline (ferric-hydroxide) forms of the W227F, W156F, and WT enzymes. Overall, these mutations have very small effects on the catalytic constants. The steady state turnover numbers (kcat) were 10 and 5 fold lower than WT for W227F and W156F, respectively, in their acidic, 5cHS forms. The values for kcat are unchanged for the alkaline forms. The kcat/KM for W156F is 4 fold lower at pH 6 and 1.6 fold higher at pH 8 than the WT values. The kcat/KM for W227F is more strongly affected than W156F, decreasing by 8 fold at pH 6 and 3 fold at pH 8, though the overall effects are still moderate.

Table 3.

Steady state kinetic parameters at 4 °C for WT, W156F, W227F and W155F DaCld in their acidic (top) and alkaline (bottom) forms.

| Enzyme | kcat (× 102 s-1) | KM (mM) | kcat/KM (M-1 s-1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| WTDaClda | 120 ± 5 | 0.24 ± 0.03 | 490 |

| W227Fb | 13 ± 7 | 0.21 ± 0.06 | 61 |

| W156Fb | 21 ± 7 | 0.16 ± 0.03 | 130 |

| W155F | NA | NA | NA |

|

| |||

| WTDaClda | 4.6 | 0.21 | 22 |

| W227Fb | 4.4 ± 0.2 | 0.62 ± 0.12 | 7.1 |

| W156Fb | 4.7 ± 0.4 | 0.13 ± 0.06 | 37 |

| W155F | NA | NA | NA |

The WT values are from ref 16.

The catalytic activity was measured immediately following dilution of the protein from a ~13 mg/mL and 3.9 mg/mL in 100 mM phosphate buffer for W156F and W227F respectively, pH 6.8 stock into reaction buffer at pH 6 for the acidic measurements and pH 8 for the alkaline. NA: The protein was not reactive toward chlorite.

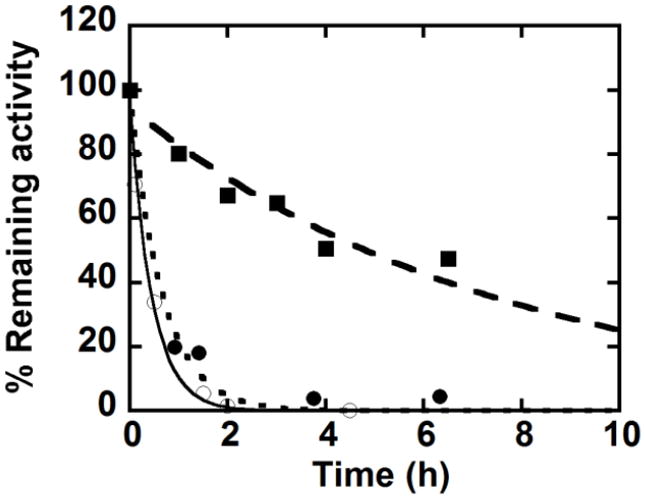

It was noted during this work that diluted stocks of the mutant proteins tend to lose activity relatively rapidly over time. To quantify these effects, specific activities immediately after dilution and after incubation in a diluted state were measured and plotted versus time. W156F loses activity exponentially over time, with a half-life depending on the extent of dilution (from a ~128 μM protein stock). Activity losses for the protein at three concentrations are compared in Fig. 7, with half-lives measured at 18 min, 27 min and ~2h when incubated at 1.3, 2.5 and 4.4 μM of W156F (100 mM citrate, pH 6, 4 °C). Some inactivation was also observed for W227F and WT DaCld under similar conditions (Fig S4), though the effect was far less pronounced (t1/2 ≥ 6h and 9h at 2.6 μM and 0.7 μM, respectively).

Fig. 7.

Residual activity following incubation of W156F at 1.3 μM (○) 2.5 μM (●) and 4 μM (■) (pH 6, 100 mM phosphate buffer, 20°C).

Dilution of W227F or W156F additionally results in changes in the heme spectrum (Fig. S5), which appear to be indicative of a shift to a 6cLS form even at pH 6. These results and the dependence of the inactivation half-life on protein concentration suggested a possible dilution-dependent change in the protein’s oligomerization state, as was observed via analytical gel filtration for W155F even in its most concentrated form. Such a change in oligomerization state could give rise to a change in the heme environment. Electrospray mass spectrometry was used in an attempt to determine the oligomerization states of these proteins. However, in each case, the oligomers fragmented into monomers (See SI) and were undetected.

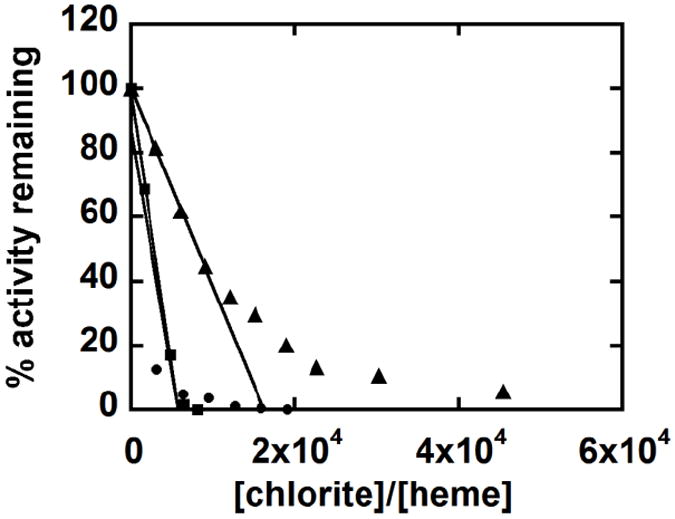

Inactivation

The turnover number for the mutant proteins was determined by the method of suicide inactivation described by Silverman.20 The turnover number is defined as the maximum number of substrate molecules eliminated per active site prior to inactivation, here presumably by oxidative heme destruction. Hence, this number quantifies the sensitivity of the heme to oxidative degradation under catalytic turnover conditions. The turnover number for WT DaCld (100 mM phosphate buffer pH 7; 25 °C) as equal to 1.7×104 ClO2− ions/heme.1 Figure 8 shows the percentage of remaining activity as a function of [ClO2−]/[heme], with linear fits to the data extrapolated to zero remaining activity. (Note: curvature in the WT data points at higher values of this ratio was attributed to protection of the active site by high concentrations of accumulating Cl− product, as previously described.1) Both W227F and W156F have significantly smaller turnover numbers than WT DaCld (each mutant ~5700, versus 17000 for WT). This indicates that the mutations do not protect the heme from degradation.

Fig. 8.

Stability of DaCld chlorite dismutase activity is diminished in the W227F and W156F mutants. Remaining activity after incubation of WT DaCld (▲), W227F (■), and W156F (●) with increasing concentrations of chlorite. The data for WT DaCld are from ref 1. The turnover numbers of 5.7 × 103 molecules of chlorite per heme for W227F and W156F were obtained by extrapolating the fitted line to the x-axis. Specific activities were measured at 4 °C in 2.4 mM chlorite.

Transient reactions of DaCld Trp mutants with PAA

DaCld(W227F), the most structurally stable of the Trp mutants, was reacted via stopped flow mixing with PAA at 20 °C in citrate/phosphate buffer at pH 6 and 8. At these pH values, DaCld(W227F) with its pKa of 6.8 should have a significant fraction of its heme iron in the acidic 5cHS and alkaline 6cLS forms, respectively.

The WT protein reacts with PAA to form [FeIV=O Por+.] (Compound I) at pH 6 (k = 1.9 × 105 M-1s-1). At pH 8 the WT PAA reaction yields either [FeIV=O AA+.], [FeIV=O + AA+.], or [FeIV=O] (Compound II) (k = 1.3 × 106 M-1s-1).2 The former two species could follow from the initial formation of a short-lived Compound I. The latter could form directly via the homolytic cleavage of the peracid O–O bond. Ferric WT DaCld exists in its acid form (5cHS) at both of these pH values, although the distal arginine at position 183 occupies its closed (heme-facing) and open (facing away from heme) conformers, respectively.21

Reaction of PAA with W227F at pH 6

When the reaction of W227F with a 25-fold excess of PAA was studied at pH 6, the data fit to a two-step model (A→B→C) that yields k1 = 16 s-1 and k2 = 5.4 s-1. Global analysis of the UV/vis spectra via singular value decomposition (using the program SPECFIT) revealed a red shift and slight diminution of the Soret absorbance (405 nm) and the appearance of visible bands near 528 and 645 nm (Fig. 9, dashed-line spectrum) for the intermediate B. The conversion of this intermediate into intermediate C is complete after 1.48 s. Intermediate C has Soret and visible bands at 414, 526, and 556 nm (dotted trace, Fig. 9). A very similar spectrum was observed following reaction of the WT protein with PAA at pH 8 (Soret λ at 415 nm and α/β at 525 and 555 nm).2

Fig. 9.

Components obtained from the global analysis of the reaction of 2 μM W227F with 50 μM PAA at pH 6 and 20 °C. A two-step A→B→C model was used to fit the data, yielding k1 = 16 s-1 and k2 = 5.4 s-1. The inset shows the visible region on an expanded scale. The ferric form is shown as a black line, intermediate B as a dashed line, and intermediate C as a dotted line.

While the intermediate C spectrum is similar to that observed for the [FeIV=O] intermediate of HRP [Compound II (410, 527, and 554 nm)], the spectrum of intermediate B is distinct from that observed for Compound I of either WT DaCld (395, 525, 550, 600, 645 nm) or HRP (400, 525, 577, 622, 651 nm) in both the positions and intensities of the bands.21,22 In spectra of known [FeIV=O Por+.] species, the extinction coefficient of the Soret absorbance is considerably less than that of the ferric heme; this large decrease is not observed for intermediate B and could suggest the presence of an additional intermediate prior to or following B. However, use of a three step model to include formation of such an intermediate did not improve the fit of the data. Another possibility is that Compound I forms but, as expected for the WT protein at pH 8,2 is not detected because it decays very rapidly to [FeIV=O AA+.] (analogous to Compund ES of CcP) or [FeIV=O + AA+.] (analogous to uncoupled radicals observed for CcP(W191F) reacted with hydrogen peroxide23 and MtKatG(W321F) reacted with PAA).24 Neither of these species is expected to have diminished Soret absorbance (like Compound I) because, in both cases, the porphyrin macrocycle maintains its aromaticity.25,26 However, both [FeIV=O AA+.] and [FeIV=O + AA+.] should have visible spectra similar to, if not indistinquishable from, [FeIV=O] described above; this is not the case (Fig. 9) suggesting that B is probably not one of these two electron oxidation products. Aromaticity, and therefore Soret extinction, would also be maintained in an acylperoxo complex; however the visible spectrum of intermediate B is also inconsistent with that of a typical acylperoxo heme complex (408, 535, 575 nm).2, 23 The nature of B was further probed by examining the W227F/PAA reaction as a function of PAA concentration.

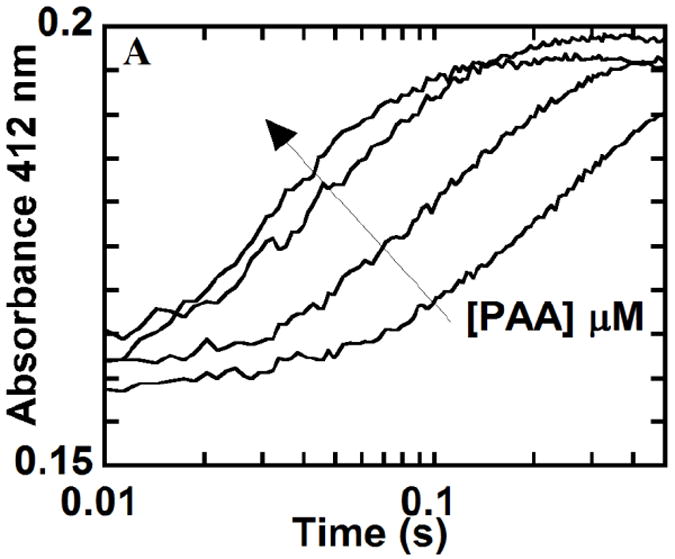

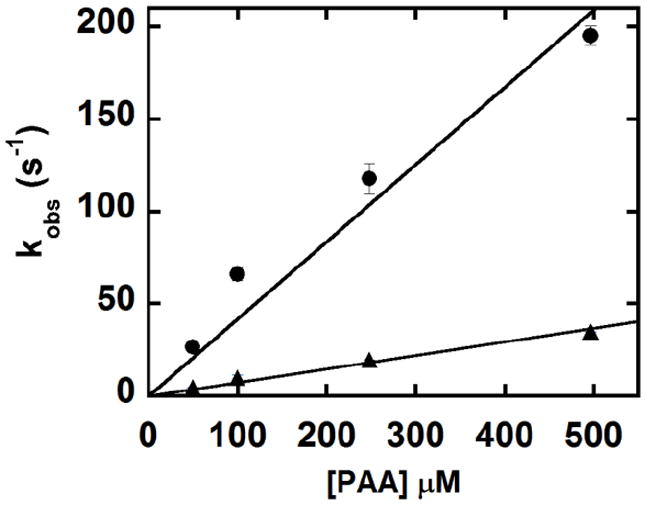

Kinetic traces at 412 nm for the reaction of 2 μM W227F with 5, 50, 125 and 250 eq of PAA at 20 °C are shown in Fig. 10. Apparent rate constants (kobs) were determined by fitting a plot of A412 versus time to a two-term exponential function (Fig. S6), to model two consecutive kinetic phases. Values of kobs were plotted as a function of [PAA] and fit in each case to a straight line, yielding apparent second order rate constants of 4.2 × 105 M-1s-1 and 7.3 × 104 M-1s-1 (Fig. 11). The first step (formation of intermediate B) has a rate constant that is comparable in magnitude to the rate constant for Compound I formation in the reaction of WT DaCld (1.9 × 105 M-1s-1). Curvature in the plot of kobs versus [PAA] for this rate constant is suggestive of enzyme/PAA complexation leading to an intermediate preceding B, which would in turn yield a hyperbolic concentration dependence for these data. However, since such an intermediate could not be clearly resolved via global analysis of the spectra, the kobs versus [PAA] data were fit as strictly second order. The second kinetic phase corresponds to the larger magnitude change in the absorbance, correlated with the conversion of intermediate B to C. The rate constants for this phase likewise depend on [PAA]. This is in contrast to the WT DaCld +PAA at pH 6.0 case, where only the first step is [PAA]-dependent and the second step is independent of PAA concentration, with a slow first order kobs = 0.3 s-1. 2

Fig. 10.

Ferric W227F was reacted with 25, 50, 125 and 250 eq of PAA at 20 °C and pH 6. Representative kinetic traces at 412 nm, the absorbance maximum of the intermediate C shown in red in Figure 9, are shown. (Arrow indicates increasing [PAA]).

Fig. 11.

Fits of straight lines to pseudo first order rate constants for the formation of intermediate B (●) and intermediate C (▲) from the reaction of W227F with PAA, measured as a function of [PAA] (pH 6). The second order rate constants for B and C formation are 4.2 × 105 M-1s-1 and 7.3 × 104 M-1s-1, respectively.

The [PAA]-dependence of the intermediate B→C conversion implies that it is an oxidation-reduction reaction of B with a second equivalent of PAA. If B is one of the aforementioned two-electron oxidation products, PAA would likely act as a 1e− reductant.23,27 Alternatively, a final possibility for the identity of B is a one electron oxidation product which exists as an equilibrium mixture of [FeIV=O] and [FeIII + AA+.]; such an equilibrium has been reported for CcP.22 Since ferric DaCld(W227F) has its Soret band at 402 nm and the ferryl protein is expected to have its Soret band around 410 nm, the observed 405 nm-Soret band is consistent with such a mixture. In this case, the [PAA]-dependence of the B→C conversion indicates that PAA would act as a 1e− oxidant of B ([FeIV=O]≡[FeIII + AA+.]) yielding [FeIV=O + AA+.]. Further characterization of intermediate C (vide infra) was carried out to shed light on nature of both B and C.

Finally, the spectrum for C formed under pseudo first order conditions by W227F diminishes in intensity over time in a [PAA]-independent manner (t1/2 = 7.7 s) (data not shown). The end product has a completely bleached heme chromophore (no appearance of new bands, for example, for verdoheme). A similar loss of chromophore occurs in the reaction of WT DaCld with 125 eq PAA at pH 6 over a slightly shorter time window (t1/2 = 6.3 s).

Reaction of PAA with W227F at pH 8

The reaction of W227F with PAA (≥20 eq) was studied at pH 8. The data at 426 nm, the wavelength of maximal absorbance change, exhibited only one phase that fit well to a single exponential function. Consistent with the observed alkaline transition with a pKa near pH 6.9, the starting spectrum resembles that expected for the 6cLS Fe(III)-OH complex (Soret λ = 411 nm; visible bands at 540 nm, 575 nm). The UV/vis spectrum of the product exhibits bands at 413 nm, 522 nm and 553 nm with a shoulder at ~605 nm) (Fig. S7) and is similar to that of C from the W227F pH 6.0

+ PAA reaction described above. The linear fit of a plot of kobs as a function of [PAA] was used to determine the second order rate constant, k = 3.2 × 104 M-1s-1. This indicates a circa order of magnitude decrease in the rate constant for formation of the initial reaction product under alkaline versus acidic conditions. Bleaching of the Soret absorbance occurred over ~148 s without the appearance of new bands (data not shown), suggesting that reaction of PAA with W227F does not lead to verdoheme as previously seen for the reactions of ferric DaCld and heme oxygenases with H2O2.28 Heme degradation occurs in a much slower manner at pH 8 (t1/2 = 74 s) than at pH 6 (t1/2 = 7.7 s).

Characterization of intermediate C

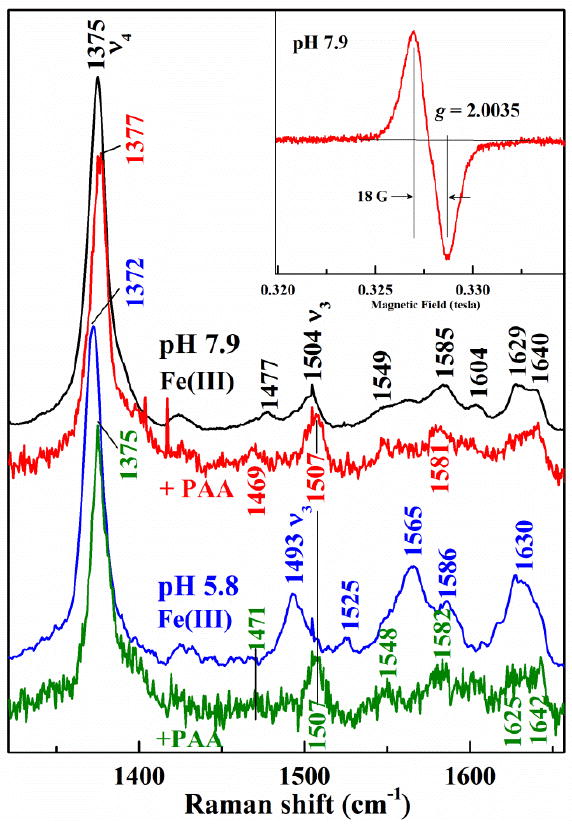

While intermediate B is observed only on the millisecond time scale, C has a long enough half-life that it can be observed for seconds to minutes. The RR spectra of C from the W227F/PAA reaction at pH 5.8 and 7.9 are shown in Figure 12. Comparison of RR spectra of intermediate C and of ferric DaCld(W227F) at pH 5.8 reveals that the 5cHS heme with its spin state marker ν3 at 1493 cm-1 is converted to an intermediate with its ν3 at 1507 cm-1. The core size markers ν4, ν2, and ν10 of intermediate C are observed at 1375, 1582, and 1642 cm-1, respectively, and are in agreement with the reported frequencies for HRP Compound II 29 and those of CcP Compound ES30. Comparison of the RR spectra of alkaline ferric DaCld(W227F) and the PAA reaction intermediate C at pH 7.9 shows that the ν3 bands at 1477 and 1504 cm-1 corresponding to 6cHS and 6cLS W227F-OH complexes, respectively, are both replaced by ν3 at 1507 cm-1 upon reaction with PAA. Additionally the ν4, ν2, and ν10 modes are very similar to those observed at pH 5.8 Thus, the same intermediate C appears to be formed under alkaline and acidic conditions and it is consistent with the presence of [FeIV=O].

Fig. 12.

Spectroscopic characterization of W227F intermediate C. The 406.7 nm-excited RR of ferric DaCld(W227F) reacted with PAA at 20 °C. Initial ferric spectra are in black for pH 7.9 and blue for pH 5.8. Spectra of intermediate C at pH 7.9 (red) and pH 5.8 (green) were obtained with addition of 18 and 10 equivalents of PAA, respectively. Each intermediate C spectrum represents 15 s reaction times, Inset: The 9-GHz EPR spectrum of the protein-based radical in W227F at pH 7.9 reacted with 18 equivalents PAA for 20 s. Experimental conditions: temperature, 77 K; modulation amplitude, 4.0 G; microwave power, 2.0 mW; modulation frequency, 100 kHz.

The 9 GHz EPR spectra recorded at 77K for DaCld(W227F) reacted with an 18 fold excess of PAA at pH 5.8 and 7.9 and flash frozen after 15 s is consistent with an isolated organic radical with an effective g value of 2.004 and a peak-to-trough width of 18 G (Inset Figure 12). The EPR spectra at both pH 7.9 and 5.8 have the same shape; spin quantification estimates the radical yield as 47 % and 37% of the total enzyme, respectively. Likely candidates for this protein-based radical are Trp or Tyr residues in DaCld(W227F) similar to those reported for catalase-peroxidases.26,31,32. Presently we envision two possible explanations for the substoichiometric yield of the radical. One is that intermediate C partially decayed prior to freezing. The second is that the radical is distributed among multiple amino acids, one of which is exchange-coupled to the ferryl. Any exchange-coupled radical would not be observed by EPR at 77 K. A multi-frequency EPR study is underway to address the identity of the protein-based radical observed here (A. Ivancich, personal communication). Taken together, the EPR and RR data suggest that intermediate C is a [FeIV=O + AA+.] in which the iron and the amino acid radical are not strongly coupled. This species could have formed as a decomposition product from either a [FeIV=O Por+.] or a [FeIV=O AA+.] species by migration of the radical away from the site of the intitial two-electron oxidation.

Discussion

Highly conserved Trp residues surround the heme periphery in chlorite dismutases. These proteins are involved in chlorite decomposition with consequent O2 generation, as well as cellular processes that remain to be fully understood in a wide variety of microorganisms. We have observed that DaCld, an enzyme with highly efficient chlorite degrading properties, is capable of forming protein-based radicals in its reactions with chlorite and peracids.2,5 Radical species could be involved in the regular reactions catalysed by Clds, or in deleterious processes that lead to heme scission. The conserved Trp residues could play additional roles beyond regulating the oxidative stability of the heme, including roles related to heme affinity, access of ligands to the heme pocket, or the stabilization of DaCld’s unusual pentameric oligomerization state. These potential functions were assessed in DaCld in which Trp227, Trp156, and Trp155 had been sequentially replaced with the redox-inactive aromatic amino acid phenylalanine.

The most dramatic effects were observed for the W155F mutant. This residue is strictly conserved across the entire family of Clds, including those from both perchlorate- and/or chlorite-decomposing organisms and those from diverse organisms with no known or expected chlorite reactivity. The latter constitute the overwhelming majority of Cld-containing species.3 The W155F mutant appears to lose the characteristic pentameric oligomerization state, secondary structure, and heme binding properties of the WT protein, and consequently has very little reactivity.

Structurally, Trp155 clearly occupies an important position. Four crystal structures of heme-bound chlorite dismutases are available [DaCld4, Azospira oryzae Cld (AzCld)33, Candidatus Nitrospira defluvii Cld (NdCld)34 and Nitrobacter winogradskyi (NwCld)35]. All possess two Trp residues at analogous positions to Trp 155 and 156 in DaCld. In the NwCld structure (2.1 Å resolution), Trp96, which corresponds to Trp155 in DaCld is part of a hydrogen bond network that links it through a water molecule to a heme propionate substituent (Fig S8).35 The crystal structure of DaCld further shows W155 and W156 on a short helix that appears to be anchored through W155 by a H-bond network analogous to that described above for NwCld. W156 is positioned at the monomer-monomer interface (Fig 13) and packs against L213 and A216 of the neighbouring subunit. Interestingly, even the structurally conservative substitution of W155 by Phe resulted in destabilization of the pentameric state of the protein, disrupting both its quaternary and tertiary structures. We hypothesize that this substitution nullifies the H-bond network connecting it with the heme, thereby weakening the stability of W156 at the subunit interface. Based on analytical gel filtration, W155F appears to be dimeric, as is the truncated Cld from NwCld and the structurally-related but sequence-distant DyP- and EfeB-families of proteins.3 However, it is not known whether W156 is positioned at the interface of the DaCld(W155F) dimer. Given the apparent importance of W155 to its intra-molecular and intermolecular structures, it is perhaps not surprising that it is the only one of the 3 Trp residues discussed here that is strictly conserved across the Cld, DyP, and EfeB families (CDE superfamily).36 However, the monomer-monomer interfaces vary significantly between the Cld, DyP, and EfeB families, so that the residue corresponding to W155 is not always at an oligomeric interface.3 Further, because the heme is flipped 180° in the DyP and EfeB families relative to the Clds, the position of the strictly conserved Trp varies relative to the heme. Hence, the precise role of this residue in the larger CDE structural superfamily of which all 3 protein families are members is uncertain.

Fig. 13.

The interface between two monomers of DaCld (red and blue). Trp 155 and 156 are illustrated in carbon yellow. The heme is represented in carbon green and the iron is an orange sphere. Figure generated using PyMOL (www.pymol.org).

W156F is also located near the monomer-monomer interface in DaCld. The effects of substituting W156 with Phe are similar to those observed for W155F, but far less severe. In fact, the protein purifies with close to stoichiometric heme bound and its pentameric state intact. Values for kcat and kcat/KM for this mutant are nearly unchanged from WT DaCld. This behavior is consistent with the hypothesis stated above regarding the importance of W155 serving as a structural anchor and W156 packing against hydrophobic side chains on the adjacent subunit. However, both the UV/vis spectrum and the catalytic activity of the protein are unstable over time, effects which are more pronounced following dilution of the protein to catalytic concentrations (0.5-10 μM) from a concentrated (130 μM) frozen stock. Specifically, the protein converts with a t1/2 = 20 min from a mixture of highly reactive 6cHS/6cLS heme to a catalytically inactive 6cLS state (incubation at 1.3 μM, 4 °C). These changes in coordination and reactivity render W156F similar to W155F. Because they are accelerated by dilution of the protein, with faster t1/2 values corresponding to greater degrees of dilution, we speculated that they may be correlated with a shift from the pentameric to a W155F-like dimeric form. However, the DaCld proteins fragmented into monomers under the various mass spectrometric conditions we were able to test, making it impossible to confirm the mutant oligomerization states definitively.37 This relative ease of dissociation suggests that, even when stabilized by the native W155 interactions, the Phe side chain in position 156 does not stabilize the subunit interface to the same extent is the indole ring of Trp.

In contrast to W155 and W156, W227 is located nearer to the heme periphery and oriented with the edge of its indole ring toward the other the monomer-monomer interface. Although it is not clear whether this Trp is directly involved in the hydrogen bond network that leads to the proximal His170 ligand (vide supra, Fig. 1)), it may play a role in positioning the His224 side chain, which is directly involved. Radical-stabilizing tryptophan residues in some peroxidases, including CcP, are correlated with direct H-bond connection and/or face-to-face π stacking with the heme or its proximal ligand. These nonbonded interactions are thought to be important conduits for radical migration away from the porphyrin.8

The W227F mutant is substantially different in its properties from either W156F or W155F. It clearly does not share the instability of coordination state, oligomerization state, or reactivity exhibited by W156F, or the dimeric/heme-free structure characteristic of W155F. Instead, the protein is a highly active (kcat/KM only 8 fold lower than WT) and stable pentamer like the WT enzyme. However, the alkaline transition to a 6cLS Fe(III)-OH form occurs with a much lower pKa than that of the WT (6.9 vs 8.916 for W227F and WT DaCld respectively), and the mutant shows small relative increases in affinity for anionic heme ligands. These observations suggest that the W227F mutation leads to a net increase in the positive charge of the Fe(III) center, a conclusion supported by RR spectroscopy. The ν(Fe-OH) stretching frequency in W227F is 12 cm-1 higher than that of WT, indicating a stronger Fe-OH bond in the mutant. This stronger bond may be due to a weakening of the interaction between E220 and the axial imidazole ligand of H170. This behavior is consistent with W227 modulating the H-bond acceptor strength of E220 with respect to the proximal H170. Whether this is due to its direct participation in that H-bonding network or the influence of W227 on its structural organization is not clear (Fig. 1). In any case, the RR spectrscopy and pKa are consistent with a more electropositive iron center due to weakening of the proximal E220/H170 H-bond upon replacement of W227 with Phe.

Transient kinetic studies of the reaction between W227F and PAA were carried out in order to determine whether W227 might be a site of radical formation. In the WT DaCld, reacting the protein with 1-3 equivalents (eq) of PAA at pH 6 results in stoichiometric formation of [FeIV=O Por+.] (Compound I). At pH 8, the same reaction results in a [FeIV=O + AA+.], where the site of the protein radical is indeterminate.2 The inability to detect Compound I at higher pH may be due to more rapid radical migration away from a very transient Compound I under those conditions. If W227 played an obligate role in the migration of the AA+. radical, its substitution with Phe would effectively eliminate this pathway.

Transient kinetic studies demonstrate that replacement of W227 with Phe does not lessen the tendency for radical formation or migration away from the porphyrin or between amino acid side chains as we had originally hypothesized. Notably, Compound I, a two electron oxidation product, is the initially observed intermediate in the WT protein, but it is not observed when reacting W227F with excess PAA. One possibility is that Compound I or the [FeIV=O AA+.] species forms initially in W227F as well but that the radical migrates more readily away from the porphyrin than in the WT. In this case, a two-electron product would be produced initially followed by rapid uncoupling of the radical from the heme iron. This uncoupled system would be observed as intermediate B. The intermediate B→C conversion for W227F depends on [PAA]. PAA as a 1e− reductant has been previously documented for a cytochrome P450.23 So, the second step in the reaction could be a one electron reduction by PAA, yielding the following sequence: FeIII → B:[FeIV=O + AA+.] → C:[FeIV=O] or [FeIII + AA+.]. The spectroscopic data seem inconsistent with this possibility. First, one would predict that B:[FeIV=O + AA+.] would have a visible spectrum similar to a ferryl heme; but, the observed spectrum is distinct from that observed for known ferryl hemes (Fig. 9). Second, if the PAA reduces the AA+. of B:[FeIV=O + AA+.], Compound II should be observed; conversely, reduction of the iron should yield [FeIII + AA+.]. The spectroscopic data for C indicates the presence of AA+. and [FeIV=O]. A [FeIV=O] ⇆ [FeIII + AA+.] equilibrium cannot be invoked because no indications of ferric heme are observed in the visible spectrum of intermediate C (Fig 9). A plausible explanation is that the W227F reaction with PAA proceeds through two one-electron oxidation steps: FeIII → B:([FeIV=O] ⇆ [FeIII + AA+.]) → C: [FeIV=O + AA+.]. This is supported by both the spectroscopic characteristics of B and C and the PAA-dependence of the B→C step.

The two one-electron oxidation steps distinguish the W227F reaction with PAA from that of WT DaCld. In WT, formation of Compound I is followed by PAA-independent (i.e. first order) conversion to [FeIV=O + AA+.]. The aggregate of data in this field suggests the strong propensity for KatGs, peroxidases, and P450s to undergo two electron oxo atom transfer reactions is attributable to the organization and basicity of the distal pocket and the strong electronic push of the proximal ligand. DaCld lacks the extensive distal H-bonding network that constrains the position and modulates the catalytic base found in KatGs and peroxidases. Moreover, RR spectroscopy shows that DaCld lacks the proximal push characteristic of a strongly H-bonded imidazole.16 While minor structure changes expected for the W227F mutation have only small effects on reactivity toward the natural substrate, the results reported here suggest that small perturbations in the heme electronic and electrostatic properties alter the reaction pathway with the non-physiological oxidant. Specifically, it appears that the proximal push and the distal pull are no longer sufficient to drive two electron oxidation of the heme by PAA. In other words, oxidation proceeds via homolytic cleavage of the peracid O-O bond.

At the same time, none of the Trp mutations enhance the stability of the enzyme toward chlorite catalysis. DaCld is subject to mechanism-based inactivation following reaction with oxidants, in both the WT and Trp mutant proteins. Heme destruction in other proteins, including heme oxygenase, occurs via ring opening with the strongly chromophoric species verdoheme and biliverdin as degradation intermediates.27 Verdoheme has been observed with WT DaCld following reaction with H2O2 but not with PAA or chlorite. The latter two oxidants instead apparently lead to generation of protein radical species.2,36 Such radical species, typically having their genesis in the porphyrin radical of Compound I, are known to lead to heme destruction in other proteins via complex and still poorly understood pathways.38,39 Both chlorite and PAA have been shown to generate protein radicals in DaCld. Such radicals, however, are not implicated in the proposed catalytic mechanism for chlorite decomposition. WT DaCld and W227F are inactivated by PAA and chlorite without the intermediacy of colored species, further suggesting the involvement of 1e− oxidations rather than hydroxylations as steps toward heme degradation. Finally heme destruction from the last observable intermediate (C) occurs with a 10-fold greater rate constant in WT than in W227F at pH 6. If heme destruction is a radical-mediated process in DaCld that can be slowed by substitution of W227 for a non-redox-active residue, this suggests that W227 is indeed a conduit for radical migration away from the porphyrin. However, the fact that heme destruction occurs in this mutant at all, with fewer overall turnovers of oxidant than in the WT protein, suggests that W227 is not the only conduit for radicals, and/or that PAA/chlorite can destroy the heme by means that do not involve the intermediacy of ferryl species like Compounds I/II.27 These results are in keeping with the observation of an [FeIV=O + AA+.] intermediate following the reaction of W227F with PAA, described above.

Conclusions

Substitution of each of the three conserved Trp residues in DaCld demonstrates essential roles for W155 and W156 in maintaining the protein in its heme-bound, enzymatically active, pentameric state. W227 is not essential for the initial formation or migration of protein radicals in DaCld, nor do any of the Trp/Phe substitutions enhance the redox stability of the protein. Collectively, these results indicate a surprisingly robust tendency toward protein radical formation in DaCld.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant GM090260 to JLD and GM094039 to GSLR. We thank Dr. A. Ivancich for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

Contributor Information

Gudrun S. Lukat-Rodgers, Email: gudrun.lukat-rodgers@ndsu.edu.

Jennifer L. DuBois, Email: jennifer.dubois@sri.com.

Notes and references

- 1.Streit BR, DuBois JL. Biochemistry. 2008;47:5271–5280. doi: 10.1021/bi800163x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mayfield JA, Blanc B, Lukat-Rodgers GS, Rodgers KR, DuBois JL. manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goblirsch B, Kurker R, Streit BR, Wilmot C, DuBois JL. J Mol Biol. 2011;408:379–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.02.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goblirsch B, Streit BR, DuBois JL, Wilmot C. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2010;15:879–888. doi: 10.1007/s00775-010-0651-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee AQ, Streit BR, Zdilla MJ, Abu-Omar MM, Dubois JL. Proc Nat Am Soc. 2008;105:15656–15659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804279105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stubbe JA, Van der Donk WA. Chem Rev. 1998;98:705–762. doi: 10.1021/cr9400875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shahangian S, Hager LP. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:1529–1533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morimoto A, Tanaka M, Takahashi S, Ishimori K, Hori H, Morishima I. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14753–14760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.14753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sivaraja M, Smith M, Goodin DB, Hoffman BM. Science. 1989;245:738–740. doi: 10.1126/science.2549632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mittler R, Zilinskas BA. FEBS Lett. 1991;289:257–259. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81083-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patterson WR, Poulos TL. Biochemistry. 1995;34:4331–4341. doi: 10.1021/bi00013a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patterson WR, Poulos TL, Goodin DB. Biochemistry. 1995;34:4342–4345. doi: 10.1021/bi00013a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gajhede M, Schuller DJ, Henriksen A, Smith AT, Poulos TL. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:1032–1038. doi: 10.1038/nsb1297-1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finzel BC, Poulos TL, Kraut J. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:13027–13036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andrade MA, Chacón P, Merelo JJ, Morán F. Prot Eng. 1993;6:383–390. doi: 10.1093/protein/6.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Streit BR, Blanc B, Lukat-Rodgers GS, Rodgers KR, DuBois JL. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:5711–5724. doi: 10.1021/ja9082182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwon TW, Brown WD. J Biol Chem. 1966;241:1509–1511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oertling WA, Kean RT, Wever R, Babcock GT. Inorg Chem. 1990;29:2633–2645. doi: 10.1021/bi00492a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghiladi R, Medzihradszky K, Rusnak F, Ortiz de Montellano P. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:13428–13442. doi: 10.1021/ja054366t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silverman RB. Methods in Enzymol. 1995;249:240–283. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)49038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blanc B, Mayfield JA, McDonald CA, Lukat-Rodgers GS, Rodgers KR, DuBois JL. Biochemistry. 2012;51:1895–1910. doi: 10.1021/bi2017377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunford HB. Heme Peroxidases. First ed. Wiley and Sons; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ivancich A, Dorlet P, Goodin DB, Un S. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:5050–5058. doi: 10.1021/ja0036514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh R, Switala J, Loewen PC, Ivancich A. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:15954–15963. doi: 10.1021/ja075108u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spolitak T, Dawson J, Ballou D. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20300–20309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501761200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spolitak T, Dawson J, Ballou D. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2008;13:599–611. doi: 10.1007/s00775-008-0348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodriguez-Lopez JN, Hernandez Ruiz J, Garcia Canovas F, Thorneley RNF, Acosta M, Arnao MB. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5469–5476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.9.5469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y, Moenne-Loccoz P, Loehr TM, Ortiz de Montellano P. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6909–6917. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.6909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Terner J, Palaniappan V, Gold A, Weiss R, Fitzgerald MM, Sullivan AM, Hosten CM. J Inorg Biochem. 2006;100:480–501. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hashimoto S, Teraoka J, Inubushi T, Yonetani T, Kitagawa T. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:11110–11118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ivancich A, Jakopitsch C, Auer M, Un S, Obinger C. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:14093–14102. doi: 10.1021/ja035582+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jakopitsch C, Ivancich A, Schmuckenschlager F, Wanasinghe A, Poeltl G, Furtmueller PG, Rueker F, Obinger C. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:46082–46095. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408399200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Geus DC, Thomassen AJ, Hagedoorn PL, Pannu NS, Van Duijn E, Abrahams JP. J Mol Biol. 2009;387:192–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kostan J, Sjoblom B, Maixner F, Mlynek G, Furtmuller P, Obinger C. J Struct Biol. 2010;172:331–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mlynek G, Sjoeblom B, Kostan J, Fuereder S, Maixner, Gysel K, Furtmuller PG, Obinger C, Wagner JM, Djinovic-Carugo K, Daims H. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:2408–2417. doi: 10.1128/JB.01262-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DuBois JL, Mayfield JA. Porphyrin Handbook. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tahallah N, Pinkse M, Maier CS, Heck AJ. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2001;15:596–601. doi: 10.1002/rcm.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Colin J, Wiseman B, Switala J, Loewen P, Ivancich A. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:8557–8563. doi: 10.1021/ja901402v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arnoa MB, Acosta M, del Rio JA, Varon R, Garcia-Canovas FA. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1990;1041:43–47. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(90)90120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.