Abstract

Context

The initial report of an interaction between a serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) and stress in the development of depression is perhaps the best-known and most cited finding in psychiatric genetics. Two recent meta-analyses explored the studies seeking to replicate this initial report and concluded that the evidence did not support the presence of the interaction. However, even the larger of the meta-analyses included only 14 of the 56 studies that have explored the relationship between 5-HTTLPR, stress and depression.

Objective

We sought to perform a meta-analysis including all relevant studies assessing whether 5-HTTLPR moderates the relationship between stress and depression.

Data Sources

We identified relevant articles from previous meta-analyses and reviews and a PubMed database search.

Study Selection

We excluded two studies presenting data that were included in other, larger, studies already included in our meta-analysis to avoid duplicate counting of subjects.

Data Extraction

In order to perform a more inclusive meta-analysis, we used the Liptak-Stouffer Z-score method to combine findings of primary studies at the significance test level rather than raw data level.

Results

We included 54 studies and found strong evidence that 5-HTTLPR moderates the relationship between stress and depression, with the 5-HTTLPR s allele associated with an increased risk of developing depression under stress (p<0.0001). When restricting our analysis to the studies included in the previous meta-analyses, we found no evidence of association (Munafo studies p=0.16; Risch studies p=0.11). This suggests that the difference in results between previous meta-analyses and ours was not due to the difference in meta-analytic technique but instead to the expanded set of studies included in this analysis.

Conclusions

Contrary to the results of the smaller earlier meta-analyses, we find strong evidence that 5-HTTLPR moderates the relationship between stress and depression in the studies published to date.

Keywords: Graduate, Medical, Education, Residency, Serotonin, Transporter

The principal function of the serotonin transporter is to remove serotonin from the synapse, returning it to the presynaptic neuron where the neurotransmitter can be degraded or re-released at a later time. A polymorphism in the promoter region of the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR) has been found to affect the transcription rate of the gene, with the short (s) allele transcriptionally less efficient that the alternate long (l) allele. In 2003, Caspi and colleagues examined the relationship between 5-HTTLPR, stress and depression using a prospective, longitudinal birth cohort and found that subjects carrying the less functional 5-HTTLPR s allele reported greater sensitivity to stress1.

This study has been cited over 2000 times in the scientific literature and generated a great deal of excitement and controversy around the potential of gene × environment interaction studies2. To date, there have been 55 follow-up studies, exploring whether 5-HTTLPR moderates the relationship between stress and depression, with some studies supporting the association between the 5-HTTLPR s allele and greater stress sensitivity and others not. Two recent meta-analyses have assessed a subset of these studies and concluded that there is no evidence supporting the presence of genetic moderation3, 4.

Since their publication, these meta-analyses have been criticized for only including a subset of the studies investigating the relationship between 5-HTTLPR stress and depression5–9. In fact, while 56 primary data studies have assessed whether 5-HTTLPR moderates the relationship between stress and depression, the Munafo and Risch meta-analyses included only 5 and 14 of those studies respectively10–48. Further, Uher and McGuffin have demonstrated that the larger, Risch meta-analysis included a significantly greater proportion of negative replication studies than positive replication studies8.

There are multiple reasons that the studies included in the meta-analyses were limited. First, the primary study data needed for traditional meta-analysis was often not available, either in the original publications or in follow-up email inquiries to study authors. For instance, Munafo and colleagues reported that 15 studies met criteria for inclusion in their meta-analysis. However, they were only able to obtain the primary study data needed for inclusion for five of those studies. There is no evidence that the studies that were able to be included in the meta-analyses were of higher “quality” than those not included.

Another reason why many studies were not included in the Risch and Munafo meta-analysis is that both meta-analyses focused exclusively on studies that explored an interaction between 5-HTTLPR and stressful life events (SLEs) in the development of depression. The original Caspi article, however, not only reported an interaction between 5-HTTLPR and SLEs, but also an interaction between 5-HTTLPR and childhood maltreatment stress. Nine studies have attempted to replicate this interaction with childhood maltreatment, but these studies were not included in the meta-analyses.

Some observers have noted that the SLE study design may have limited power to detect genetic moderation effects because they are susceptible to biases introduced by impaired recall of stressors by subjects and highly variable stressors between subjects9, 45. A newer class of studies has attempted to bypass these potential problems by focusing on specific populations that have experienced a substantial, specific stressor. These studies test whether 5-HTTLPR moderates the relationship between a specific stressor and depression. Eighteen studies have employed such specific stressor designs, but like the childhood maltreatment studies, these studies were excluded from the previous meta-analysis.

In this study, rather than focus on a limited of studies, we sought to perform a meta-analysis on the entire body of work assessing the relationship between 5-HTTLPR, stress and depression. Unfortunately, different types of studies have generally used different study designs to explore this question, rendering it very difficult to combine the studies into a single traditional meta-analysis. An approach useful in situations where equivalent raw data are not available across all studies, is to combine the studies at the level of significance tests 49. The Liptak-Stouffer Z-score method is a well-validated method for combining p-values across studies that has been utilized widely across genomics and biostatistics 50–56. In this study, we utilize the Liptak-Stouffer Z-score method to combine the results from studies investigating whether the 5-HTTLPR variant moderates the relationship between stress and depression.

Methods

Studies

Potential studies were identified from previous meta-analyses and review articles and through PubMed at the National Library of Medicine, using the search terms (depression OR depressed) AND (“serotonin transporter” OR 5-HTTLPR) AND (stress OR stressful OR maltreatment)3, 4, 9. We subsequently checked the reference sections of the identified publications and reviews found and contacted authors through email to identify additional studies in press or review. We considered all English language studies published by March 2010 assessing whether 5-HTTLPR moderates the relationship between either stressful life events, childhood maltreatment or specific stressors and depression. Two studies were excluded because their data was part of another, larger study included in the analysis14, 57. In total, data from 54 publications met inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis.

In addition to investigating all studies together, we also utilized a grouping method proposed in an earlier review to stratify studies by the type of stressor studied (Childhood Maltreatment, Specific Medical Conditions and Stressful Life Events) and assessed the presence of the association within each group9. When publications reported results for multiple types of stressors that matched different groups, we included the study in each relevant group1, 46, 58–61.

Quality Assessment

We evaluated the methodological quality of the included studies by applying an 11-item quality checklist, derived from the STREGA and STROBE checklists 62, 63. We extracted information relevant to methodological quality criteria (items 2–7, 10), and basic reporting standards (items 1, 8, 9, 11) from the Introduction, Methods, Results and Discussion sections of all included studies. Consistent with current guidelines, we did not weigh studies by quality scores or exclude studies with low quality studies 64. Instead we report the quality data extracted, so that it is available for readers to evaluate (Supplemental Table 1) 64, 65. Further, to assess whether our results were influenced by studies rated as lower quality through this measure, we repeated our overall meta-analysis with only studies with a quality score above the median 66.

P value extraction

Two investigators (KK and SS) independently extracted the relevant p value from each study. There were no cases of disagreement between the two investigators. When several p values were provided (due to the use of several depression scales or separate p values for different subsets of samples) we used a weighted mean p value for our analyses. For studies with non-significant results that did not provide exact probabilities, a p value of 1 (no association in either direction) was assumed. When an article reported analyses that matched different groups of our study, we incorporated the mean of the p value of each group into the overall analysis.

Statistical Analysis

The Liptak-Stouffer Z-score method was utilized to combine studies at the level of significance tests, weighted by study sample size. First, all extracted p-values were converted to one-tailed p-values, with p-values below 0.5 corresponding to greater s allele stress sensitivity and p-values above 0.5 corresponding to greater l allele stress sensitivity.

Next, these p-values were converted to Z-scores using a standard normal curve such that p-values below 0.5 were assigned positive Z-scores and p-values above 0.5 were assigned negative Z-scores. Subsequently these Z-scores were combined by calculating , where the weighting factors wi corresponds to the individual sample sizes, k corresponds to the number of total studies and Zi corresponds to the individual study Z-scores. The outcome of this test, Zw, follows a standard normal distribution and the corresponding probability can be obtained from a standard normal distribution table. We applied this procedure to the overall sample as well as to each of the three study groups.

To assess whether our results were substantially influenced by the presence of any individual study, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by systematically removing each study and recalculating the significance of the result. Further, to compare our method of combining studies at the significance test level with the method of combining studies at the raw data level utilized in the previous meta-analyses, we performed an analysis with only the studies included in the previous meta-analyses4.

In order to account for the possibility that results of the meta-analysis were affected by publication bias, we calculated the number of unpublished studies that would have to exist to change the outcome of the Liptak-Stouffer test from significant to non-significant (Fail-safe N)67. The ratio between the Fail-safe N and the number of studies actually published gives an estimate for the likelihood that the significant meta-analytical result is due to publication bias.

Results

Our initial search identified 148 publications. Out of these studies, we identified 54 studies that included 40,749 subjects meeting criteria for inclusion (Table 1). We found strong evidence that 5-HTTLPR moderates the relationship between stress and depression, with the s allele associated with an increased risk of developing depression under stress (p=0.00002). The significance of the result was robust to sensitivity analysis, with the overall p values remaining significant when each study was individually removed from the analysis (1.0E-6<p<0.00016). In addition, when we restricted our analysis to those studies with a study “quality” score above the median, the p value remained highly significant (3.2E-10, N=14).

Table 1.

Description of 5-HTTLPR, Stress and Depression Studies Included in the Overall Meta-analysis

| Study | No. of Participants | % Female |

Mean Age |

Study Design |

Stressor | Depression Measure | Reported Findings* |

Averaged one-tailed p value** |

Fisher’s p after study exclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mossner et al, 2001 | 72 | 46 | NA | Exposed only | Parkinson’s Disease | Hamilton Depression Rating Scale |

Positive | 0.0125 | 1.90E-05 |

| Caspi et al, 2003 | 845 | 48 | 26 | Longitudinal | Child Maltreatment | Diagnosis of Depression | Positive | 0.0100 | 4.20E-05 |

| Eley et al, 2004 | 374 | 58 | 16 | Case-Control | Adverse Family Environment |

MFQ | Partially positive | 0.2575 | 1.95E-05 |

| Grabe et al, 2004 | 973 | 69 | 52 | Cross- sectional |

Number of Chronic Diseases |

von Zerssen’s Complaints Scale |

Partially positive | 0.2503 | 2.16E-05 |

| Kendler et al, 2005 | 549 | NA | 35 | Longitudinal | Stressful Life Events | Diagnosis of Depression | Positive | 0.0070 | 3.27E-05 |

| Nakatani et al, 2005 | 2509 | 25 | 64 | Exposed only | Acute Myocardial Infarction |

Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale |

Positive | 0.0075 | 1.62E-04 |

| Jacobs et al, 2006 | 374 | 100 | 27 | Longitudinal | Stressful Life Events | SCL-90 | Positive | 0.0200 | 2.51E-05 |

| Kaufman et al, 2006 | 196 | 51 | 9 | Cross- sectional |

Child Abuse | MFQ | Partially positive | 0.0225 | 2.12E-05 |

| Ramasubbu et al, 2006 | 51 | 35 | 60 | Exposed only | Stroke | Diagnosis of Depression | Positive | 0.0130 | 1.86E-05 |

| Sjoberg et al, 2006 | 198 | 63 | 17 | Cross- sectional |

Psychosocial Circumstances in Family |

Depression Self-Rating Scale |

Partially positive/ opposite |

0.4721 | 1.76E-05 |

| Surtees et al, 2006 | 4175 | 47 | 60 | Cross- sectional |

Childhood Adversities/Stressful Life Events |

Diagnosis of Depression | Negative | 0.5000 | 1.33E-06 |

| Taylor et al, 2006 | 110 | 57 | 21 | Cross- sectional |

Childhood Adversities | BDI | Partially positive |

0.0268 | 1.95E-05 |

| Wilhelm et al, 2006 | 127 | 67 | 48 | Longitudinal | Stressful Life Events | Diagnosis of Depression | Partially positive |

0.1178 | 1.89E-05 |

| Zalsman et al, 2006 | 79 | 68 | 38 | Case-control | Stressful Life Events | Hamilton Depression Rating Scale | Partially positive |

0.2233 | 1.81E-05 |

| Cervilla et al, 2007 | 737 | 72 | 49 | Case-control | Stressful Life Events | Diagnosis of Depression | Positive | 0.0143 | 3.62E-05 |

| Chipman et al, 2007 | 2094 | 52 | 23 | Cross-sectional | Stressful Life Events | Goldman Depression Scale | Negative | 0.3400 | 1.60E-05 |

| Chorbov et al, 2007 | 236 | 100 | 22 | Longitudinal | Traumatic Events | Diagnosis of Depression | Opposite | 1.0000 | 1.10E-05 |

| Cicchetti et al, 2007 | 339 | 46 | 17 | Cross- sectional |

Child Abuse | ASEBA | Partially positive |

0.2518 | 1.94E-05 |

| Dick et al, 2007 | 956 | NA | NA | Family-based association study | Problems with work, relationship or health |

Diagnosis of Depression | Positive | 0.0040 | 5.37E-05 |

| Kilpatrick et al, 2007 | 589 | 64 | ≥ 60 (77%) |

Cross- sectional |

Hurricane exposure + low social support 6 months before hurricane |

Diagnosis of Depression | Positive | 0.0015 | 3.94E-05 |

| Kim et al, 2007 | 732 | NA | ≥65 | Cross- sectional |

Stressful Life Events | Diagnosis of Depression | Negative | 0.0385 | 3.11E-05 |

| Kraus et al, 2007 | 139 | 49 | 42 | Exposed only | Interferon-α Treatment | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

Negative | 0.5650 | 1.73E-05 |

| Mandelli et al, 2007 | 670 | 68 | 48 | Case-only | Stressful Life Events | Diagnosis of Depression | Positive | 0.0112 | 3.50E-05 |

| Middeldorp et al, 2007 | 367 | 68 | 39 | Longitudinal | Stressful Life Events | Anxiety-Depression Rating Scale |

Negative | 0.5000 | 1.73E-05 |

| Otte et al, 2007 | 557 | 15 | 68 | Exposed only | Coronary Disease | Diagnosis of Depression | Partially positive |

0.0275 | 2.86E-05 |

| Scheid et al, 2007 | 568 | 100 | 20–34 | Cross- sectional |

Stressful Life Events | CES-D | Negative | 0.0800 | 2.50E-05 |

| Brummett et al, 2008 | 288 | 75 | 58 | Cross- sectional |

Caregiving to patients with Altzheimer’s disease/dementia |

CES-D | Positive | 0.0015 | 2.64E-05 |

| Kohen et al, 2008 | 150 | 37 | 60 | Exposed only | Stroke | Geriatric Depression Scale | Positive | 0.0225 | 2.03E-05 |

| Lazary et al, 2008 | 567 | 79 | 31 | Cross- sectional |

Stressful Life Events | Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale |

Positive | 0.0025 | 3.67E-05 |

| Lenze et al, 2008 | 23 | 87 | 77 | Exposed only | Hip Fracture | Diagnosis of Depression | Positive | 0.0068 | 1.81E-05 |

| Power et al, 2008 | 1421 | NA | ≥65 | Cross- sectional |

Stressful Life Events | MINI, CES-D | Negative | 0.6200 | 1.10E-05 |

| Wichers et al, 2008 | 394 | 100 | 18–64 | Cross- sectional |

Childhood Trauma | SCL-90; SCID Depressive Symptoms |

Negative | 0.2000 | 2.03E-05 |

| Aguilera et al, 2009 | 534 | 55 | 23 | Cross- sectional |

Childhood Trauma | SCL-90-R | Positive | 0.0001 | 4.63E-05 |

| Araya et al, 2009 | 4334 | NA | 7 | Longitudinal | Stressful Life Events | SDQ Emotional Symptom 5- item Subscale |

Negative | 0.5000 | 1.03E-06 |

| Aslund et al, 2009 | 1482 | 48 | 17–18 | Cross- sectional |

Quarrels or violence between parents; Physical or Psychological Matreatment |

Depression Self-Rating Scale |

Positive | 0.0078 | 7.68E-05 |

| Bull et al, 2009 | 98 | 36 | 46 | Longitudinal | Interferon-α and Ribavirin Treatment |

Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale/BDI |

Positive | 0.0150 | 1.95E-05 |

| Coventry at al, 2009 | 3243 | 60 | 32 | Longitudinal | Stressful Life Events | Diagnosis of Depression | Negative | 0.5000 | 4.33E-06 |

| Drachmann Bukh et al, 2009 | 290 | 66 | 39 | Case-only | Stressful Life Events | Diagnosis of Depression | Negative | 0.0350 | 2.25E-05 |

| Kim et al, 2009 | 521 | 55 | 72 | Longitudinal | Number of Chronic Health Problems |

Diagnosis of Depression | Positive | 0.0050 | 3.27E-05 |

| Laucht et al, 2009 | 309 | 54 | 19 | Cross- sectional |

Stressful Life Events | Diagnosis of Depression, BDI | Partially negative/ opposite |

0.7375 | 1.57E-05 |

| Lotrich et al, 2009 | 71 | 27 | 48 | Exposed only | Interferon-α Treatment | BDI | Positive | 0.0250 | 1.88E-05 |

| McCaffery et al, 2009 | 977 | 21 | 59 | Exposed only | Established Cardiovascular Disease |

BDI | Negative | 0.5000 | 1.57E-05 |

| Ressler et al, 2009 | 926 | 62 | ≥ 18 | Cross- sectional |

Childhood Trauma | Diagnosis of Depression (partially), BDI |

Partially positive |

0.5000 | 1.59E-05 |

| Ritchie et al, 2009 | 942 | 58 | 65–92 | Cross- sectional |

Childhood Adversities | Diagnosis of Depression, CES-D, Treatment with Antidepressants |

Partially opposite |

0.5390 | 1.51E-05 |

| Wichers et al, 2009 | 502 | 100 | 27 | Longitudinal | Stressful Life Events | Diagnosis of Depression, SCL-90-R |

Partially positive |

0.3803 | 1.84E-05 |

| Zhang et al, 2009 | 792 | 54 | 33 | Case- control |

Stressful Life Events | Diagnosis of Depression | Opposite | 0.9975 | 5.24E-06 |

| Zhang et al, 2009 | 306 | 38 | NA | Exposed only | Parkinson’s Disease | CES-D | Negative | 0.5000 | 1.74E-05 |

| Hammen et al, 2010 | 346 | 62 | 24 | Longitudinal | Negative Acute Life Events, Chronic Family Stress at age 15 |

BDI | Partially positive |

0.3763 | 1.86E-05 |

| Benjet et al, in press | 78 | 100 | 12 | Cross- sectional |

Relational Aggression | Children’s Depression Inventory |

Positive | 0.0050 | 1.94E-05 |

| Goldman et al, in press | 984 | 45 | 66 | Longitudinal | Stressful Life Events | CES-D | Partially positive |

0.0203 | 4.19E-05 |

| Grassi et al, in press | 145 | 100 | 56 | Exposed only | Breast Cancer | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

Negative | 0.5000 | 1.75E-05 |

| Kumsta et al, in press | 125 | NA | 11/15 | Longitudinal | Institutionalization in Romanian orphanages at ages 6 – 42 months |

CAPA, Rutter Child Scale, Strengths&Difficulties Questionnaire |

Positive | 0.0117 | 2.02E-05 |

| Sen et al, in press | 268 | 58 | 28 | Longitudinal | Medical Internship | Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) |

Positive | 0.0020 | 2.54E-05 |

| Sugden et al, in press | 2017 | 51 | 12 | Longitudinal | Bullying Victimization | ASEBA | Negative | 0.1603 | 2.94E-05 |

| Sum | 40749 | ||||||||

| Average (N) | 755 | p=0.00002 | |||||||

“Positive” indicates a significant (p<0.05) interaction effect with the S allele, “Negative” indicates no interaction effect (p>0.05) and “Opposite” indicates a significant (p<0.05) interaction effect with the L allele.

One-tailed p value with smaller values indicating greater stress sensitivity among S allele subjects

In examining the three groups of stress studies separately, we found strong evidence for an association between the s allele and increased stress sensitivity in studies of childhood maltreatment (p=0.00007), in studies of specific medical conditions (p=0.0004), but only marginal evidence in the studies of stressful life events (p=0.033) (Table 2, 3 and 4 respectively). The removal of individual studies did not lead to changes in the significance of the outcome in studies of childhood maltreatment (7.4E-6<p<0.00014) or specific medical conditions (0.00017<p<0.0068). However, because the genetic effect in the set of stressful life events was barely below the significance threshold (p=0.033), the result was no longer significant after the exclusion of any one of several studies 1, 32, 35, 37, 68 (0.013<p<0.62).

Table 2.

| Study | Total No. of Participants |

1-tailed p |

Fisher’s p after study exclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caspi et al, 2003 | 845 | 0.010 | 5.38E-04 |

| Kaufman et al, 2006 | 196 | 0.023 | 1.17E-04 |

| Wichers et al, 2008 | 394 | 0.200 | 9.71E-05 |

| Aguilera et al, 2009 | 534 | 5.0E-05 | 8.31E-04 |

| Aslund et al, 2009 | 1482 | 0.008 | 1.40E-03 |

| Ressler et al, 2009 | 926 | 0.500 | 2.97E-05 |

| Benjet et al, in press | 78 | 0.005 | 9.27E-05 |

| Kumsta et al, in press | 125 | 0.012 | 1.03E-04 |

| Sugden et al, in press | 2017 | 0.160 | 7.42E-06 |

| Sum | 6936 | ||

| Average (N) | 694 | p=0.00007 | |

Table 3.

| Study | Total No. of Participants |

1- tailed p |

Fisher’s p after study exclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grabe et al, 2004 | 973 | 0.250 | 0.00041 |

| Nakatani et al, 2005 | 2509 | 0.008 | 0.00679 |

| Ramasubbu et al, 2006 | 51 | 0.013 | 0.00041 |

| Kraus et al, 2007 | 139 | 0.565 | 0.00035 |

| Otte et al, 2007 | 557 | 0.028 | 0.00104 |

| Kohen et al, 2008 | 150 | 0.023 | 0.00051 |

| Lenze et al, 2008 | 23 | 0.007 | 0.00038 |

| Bull et al, 2009 | 98 | 0.015 | 0.00046 |

| Kim et al, 2009 | 521 | 0.005 | 0.00145 |

| Lotrich et al, 2009 | 71 | 0.025 | 0.00042 |

| McCaffery et al, 2009 | 977 | 0.500 | 0.00017 |

| Zhang et al, 2009 | 306 | 0.500 | 0.00034 |

| Grassi et al, in press | 145 | 0.5 | 0.00035 |

| Sum | 6592 | ||

| Average (N) | 471 | p=0.0004 | |

Table 4.

| Study | Total No. of Participants |

1-tailed p |

Fisher’s p after study exclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caspi et al, 2003 | 845 | 0.010 | 0.054 |

| Eley et al, 2004 | 374 | 0.258 | 0.034 |

| Kendler et al, 2005 | 549 | 0.007 | 0.047 |

| Jacobs et al, 2006 | 374 | 0.020 | 0.040 |

| Sjoberg et al, 2006 | 198 | 0.472 | 0.032 |

| Surtees et al, 2006 | 4175 | 0.500 | 0.014 |

| Taylor et al, 2006 | 110 | 0.028 | 0.034 |

| Wilhelm et al, 2006 | 127 | 0.118 | 0.034 |

| Zalsman et al, 2006 | 79 | 0.342 | 0.033 |

| Cervilla et al, 2007 | 737 | 0.014 | 0.050 |

| Chipman et al, 2007 | 2094 | 0.292 | 0.039 |

| Chorbov et al, 2007 | 236 | 0.99995 | 0.025 |

| Dick et al, 2007 | 956 | 0.004 | 0.062 |

| Kim et al, 2007 | 732 | 0.039 | 0.046 |

| Mandelli et al, 2007 | 670 | 0.011 | 0.049 |

| Middeldorp et al, 2007 | 367 | 0.500 | 0.032 |

| Scheid et al, 2007 | 568 | 0.080 | 0.040 |

| Lazary et al, 2008 | 567 | 0.002 | 0.050 |

| Power et al, 2008 | 1421 | 0.620 | 0.026 |

| Araya et al, 2009 | 4334 | 0.500 | 0.013 |

| Coventry et al, 2009 | 3243 | 0.500 | 0.021 |

| Drachmann Bukh et al, 2009 | 290 | 0.035 | 0.037 |

| Laucht et al, 2009 | 309 | 0.500 | 0.032 |

| Ritchie et al, 2009 | 942 | 0.539 | 0.030 |

| Wichers et al, 2009 | 502 | 0.380 | 0.033 |

| Zhang et al, 2009 | 792 | 0.998 | 0.016 |

| Hammen et al, 2010 | 346 | 0.376 | 0.034 |

| Goldman et al, in press | 984 | 0.020 | 0.055 |

| Sum | 26921 | ||

| Average (N) | 961 | p=0.03 | |

When we restricted our analysis to the studies included in the two previous meta-analyses, we found no evidence of an association between 5-HTTLPR and stress sensitivity (Munafo studies p=0.16; Risch studies p=0.11).

One criticism of meta-analyses is that positive studies may be more likely to be published than negative studies and this sort of publication bias can create false positive results. We thus determine how many unpublished studies would need to exist to make the result of our overall analysis non-significant (p=0.05). We found that 729 unpublished or undiscovered studies with an average sample size (N = 755) and a non-significant result (p = 0.5) would need to exist. This corresponds to a fail-safe ratio of 14 studies not included in this meta-analysis for every included study.

Discussion

We found strong evidence that a serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) moderates the relationship between stress and depression, with the less functional short (s) allele associated with increased stress sensitivity. Our results differ from the results of the two other meta-analyses that have explored this specific association. To test whether this difference in results was due to the expanded set of studies that we included or the different meta-analytic technique utilized, we applied our meta-analytic technique to the sets of studies used in the previous meta-analyses. With these limited set of studies, our meta-analytic technique produced the same non-significant results as the previous meta-analyses, suggesting that the difference in results between meta-analyses was due to the different set of included studies.

The results of our secondary meta-analyses, where we stratified studies by stressor type, provide insight into how the inclusion of studies missing from previous studies resulted in an overall highly significant result in our meta-analysis. Both previous meta-analyses focused exclusively on stressful life events and reported no evidence that 5-HTTLPR moderates the relationship between SLEs and depression. Here, we were able to include 11 additional SLE studies, most of which were published too recently for inclusion in the previous meta-analyses. Still, we found only marginal evidence that 5-HTTLPR moderates the relationship between stressful life events and depression6. In contrast, we found robust evidence that 5-HTTLPR moderates the relationship between both childhood maltreatment and specific stressors and depression.

One important variable that may help to account for the different results in the different stressor groups is the variation in methods between the studies within each group69. Within the childhood maltreatment and specific stressors groups, the methodological details of the primary studies were generally similar. In contrast, there is marked variation in methods between SLE studies. First the studies vary substantially in what was considered a stressful life event. In addition, the method through which stressful life events were measured varied substantially between studies in this group. Some studies measured stress through one-time self-report life events checklists while others employed repeated in-person interviews and life history calendars1, 70. It is noteworthy that almost all of the studies that failed to identify an effect of genetic moderation used self-report checklists (Table 1). In addition, some studies asked subjects about SLEs and depressive episodes that occurred decades earlier while others assessed SLEs and depressive episodes soon after they occurred30, 71. As a result, the extent to which recall bias affected the findings of these studies varied substantially between the studies. Given this marked variation in methods between SLE studies, it is not surprising that the results between studies have also varied. In contrast, the methods of childhood maltreatment and specific stressors have been more uniform and the results of the studies have been more consistent.

An additional reason for the difference between the meta-analyses of the different stressor subgroups may be the nature of the stressors studied. Most of the specific stressor studies focused on chronic stressors while the SLE studies focused on acute stressful life events. Interestingly, three studies have explicitly looked at both acute and chronic stressors in their cohorts and all three have found that the 5-HTTLPR moderating effects were stronger for chronic stressors 10, 16, 45. Future primary studies that are able to systematically test genetic moderation effects on different types of stressors will be valuable in furthering our understanding of the specific characteristics of stressors that are moderated by 5-HTTLPR and other genetic loci important in stress response.

One criticism of the 5-HTTLPR-stress studies published to date is that investigators often performed multiple tests, using different subsets of their population or different stress or depression measures, but focus their paper on the tests that produced the most significant results and present their overall findings as a confirmation of the original hypothesis4, 72. For instance, different studies have found evidence of genetic moderation only in the female subset of their sample, only in the subset of their sample that was evaluated through an in-depth clinical interview or only when the analysis was restricted to chronic stressors10, 73, 74. As we discuss above, some of the variation in results with different population sub-samples or depression and stress measures may represent true and important heterogeneity in the 5-HTTLPR moderation effect. However another possible explanation for the variation in results within the same study is that some of these secondary findings are actually false positive results that resulted from uncorrected multiple testing. To guard against false positive from the primary studies causing a false positive in our meta-analysis, we did not rely on the statistical tests highlighted by authors. Instead, we calculated a weighted average of p values of the tests that were performed in a given study. When authors only reported the significance results for a subset of these tests, we assumed that p = 1 for the unreported tests. The fact that we confirmed the previous non-significant results when we applied our meta-analytic technique to the sets of studies included in the previous meta-analyses suggests that statistical bias from primary studies did not unduly affect our results.

While this meta-analysis focused specifically on observational studies specifically assessing whether 5-HTTLPR moderates the relationship between stress and depression, the results we found are consistent with a broad range of studies exploring the relationship between functional serotonin transporter genetic variation and stress in different ways. Experimental neuroscience studies have found consistent evidence that 5-HTTLPR s allele carriers demonstrate a more pronounced amygdala and HPA axis response to affective or threatening stimuli 75–77. In addition, non-human primates studies that have found increased stress sensitivity among individuals with a low functioning serotonin transporter allele78, 79. Together, these lines of evidence provide clear and converging evidence that 5-HTTLPR plays a role in moderating the response to stress. It is also clear from these studies however, that this variant explains only a small proportion of the genetic variance relevant to stress response. The successes and failures of the studies exploring the 5-HTTLPR variant included in this analysis should guide our future work as we try to develop a broader understanding of the genetic architecture that moderates the relationship between stress and depression.

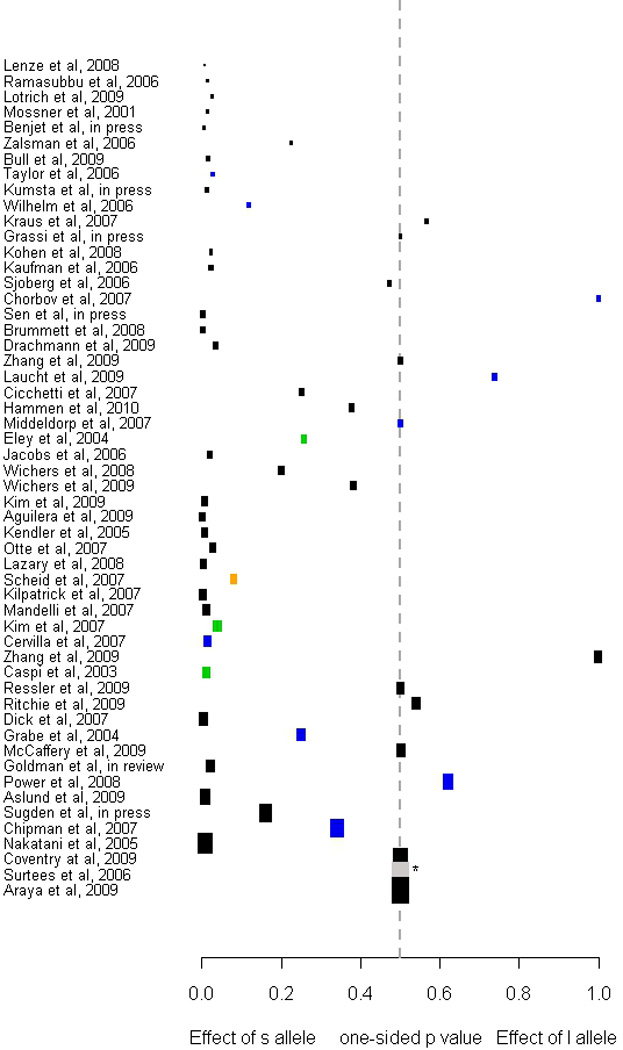

Figure 1. Forest plot for the 54 studies included in the meta-analysis.

The boxes indicate the one-tailed p value for each study, with lower values corresponding to greater stress sensitivity of s allele carriers and higher values corresponding to greater stress sensitivity of l allele carriers. The size of the box indicates the relative sample size. The triangle indicates the result of our overall meta-analysis.

Labels: Magenta - study included only in the Munafo meta-analysis; Cyan - study included only in the Risch meta-analysis; Blue - study included both in the Munafo and the Risch meta-analysis.

* Risch et al included only a subset of this study (Gillespie et al, N=1091).

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This work was supported by NIH KL2 grant number: UL1RR024986 (SS), the University of Michigan Depression Center (SS) and Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes (KK).

Role of the Sponsor: The funding agencies played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr. Sen and Ms. Karg had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Sen, Karg, Burmeister

Acquisition of data: Karg, Sen

Analysis and interpretation of data: Sen, Karg, Shedden.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Sen, Burmeister, Karg, Shedden.

Statistical analysis: Shedden, Karg, Sen.

Obtained funding: Sen, Burmeister.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Sen

Study supervision: Sen, Burmeister.

Financial Disclosures: None reported.

Additional Contributions: Brady West, MA, Center for Statistical Consultation and Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, helped with the statistical analyses for this article.

Competing Interests: Karg, Burmeister, Shedden and Sen declare no competing interests and therefore have nothing to declare.

References

- 1.Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, et al. Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science. 2003 Jul 18;301(5631):386–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1083968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holden C. Behavioral genetics. Getting the short end of the allele. Science. 2003 Jul 18;301(5631):291–293. doi: 10.1126/science.301.5631.291a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Munafo MR, Durrant C, Lewis G, Flint J. Gene x Environment Interactions at the Serotonin Transporter Locus. Biol Psychiatry. Aug 6;:2008. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Risch N, Herrell R, Lehner T, et al. Interaction between the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR), stressful life events, and risk of depression: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009 Jun 17;301(23):2462–2471. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lotrich FE, Lenze E. Gene-environment interactions and depression. JAMA. 2009 Nov 4;302(17):1859–1860. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1576. author reply 1861–1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rutter M, Thapar A, Pickles A. Gene-Environment Interactions Biologically Valid Pathway or Artifact? Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66(12):1287–1289. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.167. 12/2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaufman J, Gelernter J, Kaffman A, Caspi ATM. Arguable Assumptions, Debatable Conclusions. Biological Psychiatry. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uher R, McGuffin P. The moderation by the serotonin transporter gene of environmental adversity in the etiology of depression: 2009 update. Mol Psychiatry. :2009. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caspi A, Hariri AR, Holmes A, Uher R, Moffitt TE. Genetic Sensitivity to the Environment: The Case of the Serotonin Transporter Gene and Its Implications for Studying Complex Diseases and Traits. Am J Psychiatry. 2010 Mar 15; doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09101452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hammen C, Brennan PA, Keenan-Miller D, Hazel NA, Najman JM. Chronic and acute stress, gender, and serotonin transporter gene-environment interactions predicting depression symptoms in youth. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010 2010 Feb;51(2):180–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02177.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kilpatrick DG, Koenen KC, Ruggiero KJ, et al. The serotonin transporter genotype and social support and moderation of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in hurricane-exposed adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2007 2007 Nov;164(11):1693–1699. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06122007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mandelli L, Serretti A, Marino E, Pirovano A, Calati R, Colombo C. Interaction between serotonin transporter gene, catechol-o-methyltransferase gene and stressful life events in mood disorders. The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;10(04):437–447. doi: 10.1017/S1461145706006882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scheid JM, Holzman CB, Jones N, et al. Depressive symptoms in mid-pregnancy, lifetime stressors and the 5-HTTLPR genotype. Genes Brain Behav. 2007 2007 Jul;6(5):453–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaufman J, Yang BZ, Douglas-Palumberi H, et al. Social supports and serotonin transporter gene moderate depression in maltreated children. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Dec 7;101(49):17316–17321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404376101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaufman J, Yang BZ, Douglas-Palumberi H, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor-5-HTTLPR gene interactions and environmental modifiers of depression in children. Biol Psychiatry. 2006 Apr 15;59(8):673–680. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kendler KS, Kuhn JW, Vittum J, Prescott CA, Riley B. The interaction of stressful life events and a serotonin transporter polymorphism in the prediction of episodes of major depression: a replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 May;62(5):529–535. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobs N, Kenis G, Peeters F, Derom C, Vlietinck R, van Os J. Stress-related negative affectivity and genetically altered serotonin transporter function: evidence of synergism in shaping risk of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006 Sep;63(9):989–996. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.9.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sjoberg RL, Nilsson KW, Nordquist N, et al. Development of depression: sex and the interaction between environment and a promoter polymorphism of the serotonin transporter gene. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006 Aug;9(4):443–449. doi: 10.1017/S1461145705005936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, Sturge-Apple ML. Interactions of child maltreatment and serotonin transporter and monoamine oxidase A polymorphisms: depressive symptomatology among adolescents from low socioeconomic status backgrounds. Dev Psychopathol. Fall;19(4):1161–1180. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aguilera M, Arias B, Wichers M, et al. Early adversity and 5-HTT/BDNF genes: new evidence of gene-environment interactions on depressive symptoms in a general population. Psychol Med. 2009 Feb 12;:1–8. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709005248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stein MB, Schork NJ, Gelernter J. Gene-by-environment (serotonin transporter and childhood maltreatment) interaction for anxiety sensitivity, an intermediate phenotype for anxiety disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008 Jan;33(2):312–319. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim JM, Stewart R, Kim SW, Yang SJ, Shin IS, Yoon JS. Modification by two genes of associations between general somatic health and incident depressive syndrome in older people. Psychosom Med. 2009 Apr;71(3):286–291. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181990fff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kohen R, Cain KC, Mitchell PH, et al. Association of serotonin transporter gene polymorphisms with poststroke depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008 Nov;65(11):1296–1302. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.11.1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lenze EJ, Munin MC, Ferrell RE, et al. Association of the serotonin transporter gene-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR) genotype with depression in elderly persons after hip fracture. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005 2005 May;13(5):428–432. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.5.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakatani D, Sato H, Sakata Y, et al. Influence of serotonin transporter gene polymorphism on depressive symptoms and new cardiac events after acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2005 Oct;150(4):652–658. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.03.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otte C, McCaffery J, Ali S, Whooley MA. Association of a serotonin transporter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) with depression, perceived stress, and norepinephrine in patients with coronary disease: the Heart and Soul Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2007 2007 Sep;164(9):1379–1384. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06101617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramasubbu R, Tobias R, Buchan AM, Bech-Hansen NT. Serotonin transporter gene promoter region polymorphism associated with poststroke major depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006 2006 Winter;18(1):96–99. doi: 10.1176/jnp.18.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phillips-Bute B, Mathew JP, Blumenthal JA, et al. Relationship of genetic variability and depressive symptoms to adverse events after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Psychosom Med. 2008 2008 Nov;70(9):953–959. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318187aee6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCaffery JM, Bleil M, Pogue-Geile MF, Ferrell RE, Manuck SB. Allelic variation in the serotonin transporter gene-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR) and cardiovascular reactivity in young adult male and female twins of European-American descent. Psychosom Med. 2003 2003 Sep-Oct;65(5):721–728. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000088585.67365.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lotrich FE, Ferrell RE, Rabinovitz M, Pollock BG. Risk for depression during interferon-alpha treatment is affected by the serotonin transporter polymorphism. Biol Psychiatry. 2009 Feb 15;65(4):344–348. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Araya R, Hu X, Heron J, et al. Effects of stressful life events, maternal depression and 5-HTTLPR genotype on emotional symptoms in pre-adolescent children. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009 Jul 5;150B(5):670–682. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dick DM, Plunkett J, Hamlin D, et al. Association analyses of the serotonin transporter gene with lifetime depression and alcohol dependence in the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA) sample. Psychiatr Genet. 2007 2007 Feb;17(1):35–38. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e328011188b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kraus MR, Al-Taie O, Schafer A, Pfersdorff M, Lesch KP, Scheurlen M. Serotonin-1A receptor gene HTR1A variation predicts interferon-induced depression in chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2007 2007 Apr;132(4):1279–1286. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brummett BH, Boyle SH, Siegler IC, et al. Effects of environmental stress and gender on associations among symptoms of depression and the serotonin transporter gene linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR) Behav Genet. 2008 2008 Jan;38(1):34–43. doi: 10.1007/s10519-007-9172-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lazary J, Lazary A, Gonda X, et al. New evidence for the association of the serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4) haplotypes, threatening life events, and depressive phenotype. Biol Psychiatry. 2008 Sep 15;64(6):498–504. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wichers M, Kenis G, Jacobs N, et al. The BDNF Val(66)Met x 5-HTTLPR x child adversity interaction and depressive symptoms: An attempt at replication. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008 Jan 5;147B(1):120–123. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aslund C, Leppert J, Comasco E, Nordquist N, Oreland L, Nilsson KW. Impact of the interaction between the 5HTTLPR polymorphism and maltreatment on adolescent depression.A population-based study. Behav Genet. 2009 2009 Sep;39(5):524–531. doi: 10.1007/s10519-009-9285-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bull SJ, Huezo-Diaz P, Binder EB, et al. Functional polymorphisms in the interleukin-6 and serotonin transporter genes, and depression and fatigue induced by interferon-alpha and ribavirin treatment. Mol Psychiatry. 2009 Dec;14(12):1145. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coventry WL, James MR, Eaves LJ, et al. Do 5HTTLPR and stress interact in risk for depression and suicidality? Item response analyses of a large sample. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009 Nov;12 doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bukh J, Bock C, Vinberg M, Werge T, Gether U, Vedel Kessing L. Interaction between genetic polymorphisms and stressful life events in first episode depression. J Affect Disord. :2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCaffery JM, Duan QL, Frasure-Smith N, et al. Genetic predictors of depressive symptoms in cardiac patients. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009 Apr 5;150B(3):381–388. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang K, Xu Q, Xu Y, et al. The combined effects of the 5-HTTLPR and 5-HTR1A genes modulates the relationship between negative life events and major depressive disorder in a Chinese population. J Affect Disord. 2009 2009 Apr;114(1–3):224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benjet C, Thompson RJ, Gotlib IH. 5-HTTLPR moderates the effect of relational peer victimization on depressive symptoms in adolescent girls. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009 Sep 14; doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumsta R, Stevens S, Brookes K, et al. 5HTT genotype moderates the influence of early institutional deprivation on emotional problems in adolescence: Evidence from the english and romanian adoptee (ERA) study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02249.x. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sen S, Kranzler H, Chan G, et al. A Prospective Cohort Study Investigating Factors Associated with Depression during Medical Internship. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010 doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.41. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sugden K, Arseneault L, Harrington H, Moffitt T, Williams B, Caspi A. The serotonin transporter gene moderates the development of emotional problems among children following bullying victimization. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.01.024. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldman N, Glei D, Lin Y-H, Weinstein M. The serotonin transporter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR): Allelic variation and links with depressive symptoms. Depress Anxiety. doi: 10.1002/da.20660. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mossner R, Henneberg A, Schmitt A, et al. Allelic variation of serotonin transporter expression is associated with depression in Parkinson's disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2001 2001 May;6(3):350–352. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hedges LV, Olkin I. Statistical methods for meta-analysis. New York: Academic; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Richards JB, Waterworth D, O'Rahilly S, et al. A genome-wide association study reveals variants in ARL15 that influence adiponectin levels. PLoS Genet. 2009 Dec;5(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000768. e1000768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hwang D, Rust AG, Ramsey S, et al. A data integration methodology for systems biology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 2005 Nov 29;102(48):17296–17301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508647102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leung M, Cheung C, Yu K, et al. Gray Matter in First-Episode Schizophrenia Before and After Antipsychotic Drug Treatment.Anatomical Likelihood Estimation Meta-analyses With Sample Size Weighting. Schizophr Bull. 2009 Sep 16; doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Majeti R, Becker MW, Tian Q, et al. Dysregulated gene expression networks in human acute myelogenous leukemia stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 2009 Mar 3;106(9):3396–3401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900089106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liptak T. On the combination of independent tests. Magyar Tudományos Akadémia Matematikai Kutató Intezetenek Kozlemenyei. 1958;3:171–197. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stouffer S, Suchman E, DeVinnery L, Star S, Williams R. The American Soldier, volume I: Adjustment during Army Life. Princeton University Press; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koziol JA, Tuckwell HC. A bayesian method for combining statistical tests. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference. 999;78:317–323. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gillespie NA, Whitfield JB, Williams B, Heath AC, Martin NG. The relationship between stressful life events, the serotonin transporter (5-HTTLPR) genotype and major depression. Psychol Med. 2005 2005 Jan;35(1):101–111. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chipman P, Jorm AF, Prior M, et al. No interaction between the serotonin transporter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) and childhood adversity or recent stressful life events on symptoms of depression: results from two community surveys. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007 Jun 5;144B(4):561–565. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Laucht M, Treutlein J, Blomeyer D, et al. Interaction between the 5-HTTLPR serotonin transporter polymorphism and environmental adversity for mood and anxiety psychopathology: evidence from a high-risk community sample of young adults. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009 2009 Jul;12(6):737–747. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708009875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Taylor SE, Way BM, Welch WT, Hilmert CJ, Lehman BJ, Eisenberger NI. Early family environment, current adversity, the serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism, and depressive symptomatology. Biol Psychiatry. 2006 2006 Oct 1;60(7):671–676. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zalsman G, Huang YY, Oquendo MA, et al. Association of a triallelic serotonin transporter gene promoter region (5-HTTLPR) polymorphism with stressful life events and severity of depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2006 2006 Sep;163(9):1588–1593. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Little J, Higgins JP, Ioannidis JP, et al. Strengthening the reporting of genetic association studies (STREGA): an extension of the STROBE Statement. Hum Genet. 2009 2009 Mar;125(2):131–151. doi: 10.1007/s00439-008-0592-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007 2007 Oct 20;370(9596):1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Detsky AS, Naylor CD, O'Rourke K, McGeer AJ, L'Abbe KA. Incorporating variations in the quality of individual randomized trials into meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992 1992 Mar;45(3):255–265. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kavvoura FK, Ioannidis JP. Methods for meta-analysis in genetic association studies: a review of their potential and pitfalls. Hum Genet. 2008 2008 Feb;123(1):1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00439-007-0445-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Juni P, Witschi A, Bloch R, Egger M. The hazards of scoring the quality of clinical trials for meta-analysis. JAMA. 1999 1999 Sep 15;282(11):1054–1060. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.11.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rosenthal R. The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychological bulletin. 1979;86:638–641. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cervilla JA, Molina E, Rivera M, et al. The risk for depression conferred by stressful life events is modified by variation at the serotonin transporter 5HTTLPR genotype: evidence from the Spanish PREDICT-Gene cohort. Mol Psychiatry. 2007 2007 Aug;12(8):748–755. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Uher R, McGuffin P. The moderation by the serotonin transporter gene of environmental adversity in the aetiology of mental illness: review and methodological analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2008 2008 Feb;13(2):131–146. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Surtees PG, Wainwright NW, Willis-Owen SA, Luben R, Day NE, Flint J. Social adversity, the serotonin transporter (5-HTTLPR) polymorphism and major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2006 2006 Feb 1;59(3):224–229. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wilhelm K, Mitchell PB, Niven H, et al. Life events, first depression onset and the serotonin transporter gene. Br J Psychiatry. 2006 Mar;188:210–215. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.009522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Munafo MR, Flint J. Replication and heterogeneity in gene x environment interaction studies. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009 2009 Jul;12(6):727–729. doi: 10.1017/S1461145709000479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Eley TC, Sugden K, Corsico A, et al. Gene-environment interaction analysis of serotonin system markers with adolescent depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2004 2004 Oct;9(10):908–915. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ressler KJ, Bradley B, Mercer KB, et al. Polymorphisms in CRHR1 and the serotonin transporter loci: Gene x Gene x Environment interactions on depressive symptoms. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. Apr 5;153B(3):812–824. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Munafo MR, Brown SM, Hariri AR. Serotonin transporter (5-HTTLPR) genotype and amygdala activation: a meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2008 2008 May 1;63(9):852–857. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gotlib IH, Joormann J, Minor KL, Hallmayer J. HPA axis reactivity: a mechanism underlying the associations among 5-HTTLPR, stress, and depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2008 2008 May 1;63(9):847–851. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Way BM, Taylor SE. The serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism is associated with cortisol response to psychosocial stress. Biol Psychiatry. Mar 1;67(5):487–492. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Barr CS, Newman TK, Schwandt M, et al. Sexual dichotomy of an interaction between early adversity and the serotonin transporter gene promoter variant in rhesus macaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 2004 Aug 17;101(33):12358–12363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403763101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Spinelli S, Schwandt ML, Lindell SG, et al. Association between the recombinant human serotonin transporter linked promoter region polymorphism and behavior in rhesus macaques during a separation paradigm. Dev Psychopathol. 2007 2007 Fall;19(4):977–987. doi: 10.1017/S095457940700048X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]