Abstract

Objectives

Experiments demonstrate that exposure to parks and other ‘green spaces’ promote favourable psychological and physiological outcomes. As a consequence, people who reside in greener neighbourhoods may also have a lower risk of short sleep duration (<6 h). This is potentially important as short sleep duration is a correlate of obesity, chronic disease and mortality, but so far this hypothesis has not been previously investigated.

Design

Cross-sectional data analysis.

Setting

New South Wales, Australia.

Participants

This study investigated whether neighbourhood green space was associated with a healthier duration of sleep (to the nearest hour) among 259 319 Australians who completed the 45 and Up Study baseline questionnaire between 2006 and 2009 inclusive.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Multinomial logit regression was used to investigate the influence of an objective measure of green space on categories of sleep duration: 8 h (normal); between 9 and 10 h (mid-long sleep); over 10 h (long sleep); between 6 and 7 h (mid-short sleep); and less than 6 h (short sleep). Models were adjusted for psychological distress, physical activity and a range of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics.

Results

People living in greener neighbourhoods reported a lower risk of short sleep. For example, compared with participants living in areas with 20% green space land-use, the relative risk ratios for participants with 80%+ green space was 0.86 (95% CI 0.81 to 0.92) for durations between 6 and 7 h, and 0.68 (95% CI 0.57 to 0.80) for less than 6 h sleep. Unexpectedly, the benefit of more green space for achieving 8 h of sleep was not explained by controls for psychological distress, physical activity or other socioeconomic factors.

Conclusions

Green space planning policies may have wider public health benefits than previously recognised. Further research in the role of green spaces in promoting healthier sleep durations and patterns is warranted.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Public Health, Social Medicine

Article summary.

Article focus

Previous work suggests that more green space within the neighbourhood environment can promote better mental health and more active lifestyles.

Better mental health and more active lifestyles are correlates of a healthy duration of sleep (usually around 8 h a night.)

Greener neighbourhoods, therefore, may guard against short sleep duration (usually less than 6 h per night), which is correlated with obesity, chronic disease and mortality.

Key messages

In a large study of Australian adults, we found those in greener neighbourhoods were at a lower risk of short sleep (<6 h a night).

More green space was not associated with longer sleep durations (which are also correlated with poor health outcomes).

Unexpectedly, the benefit of more green space for achieving a healthier duration of sleep was not explained by controls for psychological distress, physical activity and socioeconomic variables.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study benefits from a large sample size focusing on adults in middle-to-older age, who simultaneously shoulder the vast burden of chronic disease and are the biggest users of health services.

This study is strengthened by use of validated measures of sleep duration, psychological distress, physical activity and an objective measure of green space exposure.

Cross-sectional data prohibits causal inference, though follow-up of the participants across time will allow the opportunity for replication of this study with a longitudinal design.

Introduction

Positive psychological and physiological outcomes from exposure to parks and other forms of natural environment in experimental studies1–3 have fuelled support for the integration of these ‘green spaces’ within planning policy.4 5 Health benefits are thought to accrue via psychoneuroendocrine pathways, wherein the experience of nature triggers restoration.6–8 These benefits are likely to be in tandem with physical activity, more of which is not only correlated with better mental health,9 but also increasingly likely among people who live in greener neighbourhoods.10–12

While the epidemiological literature is increasingly replete with studies documenting association between green spaces, mental health and physical activity, less attention has been paid to other important health behaviours and outcomes. One such outcome is sleep duration. Many studies have reported a parabolic association13 between the number of hours a person sleeps and their subsequent risk of poor self-rated health,14 obesity,15 16 cardiovascular disease,17 diabetes 18 19 and death.20–22 Favourable mental health and active lifestyles are thought to be drivers of a healthier duration of sleep (usually around 8 h per night).23–25 Since these drivers are widely reported to be positive outcomes of living in greener neighbourhoods, we hypothesised that people with access to more green space would therefore be more likely to achieve a healthier duration of sleep.

This hypothesis was investigated in a large sample of Australian adults in middle-to-older age, who simultaneously shoulder the vast burden of chronic disease and are the biggest users of healthcare in Australia.

Method

Data

A sample of 259 319 participants with valid data on sleep duration were selected from 267 151 in the 45 and Up Study.26 The questionnaire is available online from http://www.45andup.org.au. Participants were randomly selected from the Medicare Australia database (the national provider of universal health insurance) and surveyed between 2006 and 2009. The survey response rate was 18%, though previous work has shown that results from the 45 and Up Study are comparable to those derived from a representative population survey.27 Geocoding of participants in the 45 and Up Study was available at the Census Collection Districts (CCD) scale. CCDs contain 225 people on average and were the smallest geography at which 2006 Census data were disseminated.28 The University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee approved the 45 and Up Study.

Outcome measure

Sleep duration was derived from responses to the following question: “About how many hours in each 24 h day do you usually spend sleeping (including at night and naps)?” and has been used in previous analyses of the same data.14 15 25 29 Responses to this question were missing for 7755 people and these were omitted from the analyses. To account for the curvilinear association between sleep duration and health,13 responses were classified into a multinomial variable as follows: 8 h (normal); between 9 and 10 h (mid-long sleep); over 10 h (long sleep); between 6 and 7 h (mid-short sleep); and less than 6 h (short sleep). This classification allows for the healthiest duration (8 h) to be used as a reference group for all other categories.

Green space

Meshblocks classified as ‘parkland’ in the Australian Bureau of Statistics land-use classification for 2006 were used to construct the measure of green space. ‘Farmland’ meshblocks were not used as they do not strictly represent spaces available for recreation. The measure of green space was based on the percentage available within a 1 km buffer around the population-weighted centroid of each CCD. A 1 km buffer was selected so as to represent land-use within a reasonable walking distance from place of residence, and has been used in previous studies of green space and health.11 12 30 31 The percentage green space measure was classified into fifths to explore for potential non-linearities (0–20%, 20–40%, 40–60%, 60–80%, 80%+).

Other individual and neighbourhood measures

The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) was used to assess mental health status.32 33 The K10 measures symptoms of psychological distress experienced over the past 4 weeks, including feeling tired for no reason, nervous, hopeless, restless, depressed, sad and worthless. Participants had five choices for each of the 10 questions (none of the time = 1, a little of the time = 2, some of the time = 3, most of the time = 4, all of the time=5). The K10 is constructed by summing responses to each of the questions, with scores of 22 and over identified those with a high risk of psychological distress.34 The K10 has been used in this way in previously published analyses of the 45 and Up Study.35

The measure of physical activity was an aggregate of the number of 10 min sessions spent either walking or in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, assessed using the Active Australia Survey.36 The question was “How many times did you do each of these activities last week?” Participants could indicate walking, moderate (eg, gentle swimming) and vigorous (eg, jogging) forms activity separately.

A range of other individual characteristics were also taken account of, including age, gender, ethnicity, country of birth, body mass index (BMI), annual income, highest educational qualifications, economic status (employed, unemployed, retired, inactive due to poor health), couple status, number of alcoholic drinks consumed in the last week, smoking status, language other than English spoken at home and the Duke Social Support Index.37

Two other characteristics at the neighbourhood level were considered. The Socio-Economic Index for Areas (SEIFA) ‘Index of Relative Socio-Economic Advantage/Disadvantage’ was used to measure local socioeconomic circumstances. Differences between urban and rural areas were controlled using the ‘Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia’. Like the measure of green space, both of these neighbourhood indicators were created using data from 2006 to fit with the baseline questionnaire.

Statistical analysis

Cross-tabulations were used to compare the patterning of each sleep duration category according to proximity to green space and all other explanatory variables. A multinomial logit regression was used to assess the risk of short sleep versus an 8 h sleep duration (reference), accounting for longer sleeps as separate categories simultaneously within the same model. Parameters were exponentiated to relative risk ratios (RRRs). RRRs over 1 indicated positive association, whereas RRRs below 1 denoted negative association. Bivariate models containing the measure of green space (fitted as a categorical variable) were initially adjusted for interactions between age and gender. The robustness of any associations found were then tested with controls for psychological distress and physical activity. Socioeconomic and other explanatory variables were then added sequentially, with any change in the potential association between green space exposure and sleep duration documented.

To account for the nested data structure, the Huber-White method was utilised in all models to adjust SEs.38 39 The log-likelihood ratio test (p<0.05) was used to identify statistically significant associations. Analyses were conducted in STATA V.12 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

In table 1 the prevalence of sleep for an 8 h duration (adjusted for age and gender) was demonstrably higher in neighbourhoods with a higher percentage of green space. This was also for sleep durations between 9 and 10 h, but not for those of 10 h or more. Meanwhile, the prevalence of sleep durations less than 8 h was higher in neighbourhoods with less green space. The percentage point difference reported between neighbourhoods with 80%+ and less than 20% green space proximity was 3.6 for a mid-short sleep duration between 6 and 7 h (p<0.001). A smaller though statistically significant gap was also reported for short sleeps less than 6 h (0.9 percentage points, p<0.001). The risk of short sleep duration (6 h or less per day) was four times higher among participants at a high risk of psychological distress (95% CI 3.8 to 4.3), 1.5 times higher among obese people versus those normal BMI (95% CI 1.46 to 1.63), 1.8 times higher among people earning less than $20 000/year (95% CI 1.7 to 1.9), 1.6 times higher for residents of the most deprived quintile of neighbourhoods (95% CI 1.5 to 1.7) and 1.1 times higher for those in remote and rural versus urban areas (95% CI 1.0 to 1.2).

Table 1.

Age-gender adjusted patterning of sleep duration by proximity to green space

| 8 h (normal) | Between 9 and 10 h (mid-long sleep) | Over 10 h (long sleep) | Between 6 and 7 h (mid-short sleep) | Less than 6 h (short sleep) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (259 319) | 104 432 | 47 424 | 4 938 | 92 860 | 9665 |

| Green space (% (n)) | % (95% CI) | ||||

| 0–20 (177 106) | 40.0 (39.8 to 40.3) | 17.5 (17.3 to 17.7) | 1.6 (1.5 to 1.6) | 35.6 (35.3 to 35.8) | 3.7 (3.6 to 3.8) |

| 20–40 (49 316) | 40.4 (39.9 to 40.8) | 16.9 (16.6 to 17.3)** | 1.4 (1.3 to 1.5)*** | 36.2 (35.7 to 36.7)* | 3.6 (3.4 to 3.8) |

| 40–60 (18 045) | 40.5 (39.7 to 41.3) | 17.9 (17.3 to 18.6) | 1.4 (1.2 to 1.6)* | 35.3 (34.4 to 36.1) | 3.3 (3.1 to 3.6)** |

| 60–80 (8253) | 41.2 (40.0 to 42.3)* | 18.6 (17.6 to 19.6)** | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.5) | 34.4 (33.2 to 35.7)* | 2.9 (2.5 to 3.3)*** |

| 80+ (6599) | 41.9 (40.7 to 43.2)** | 20.1 (19.1 to 21.2)*** | 1.6 (1.3 to 1.9) | 32.0 (30.8 to 33.2)*** | 2.8 (2.3 to 3.2)*** |

***p<0.001; **p<0.01; *p<0.05 (from 0–20% green space as the reference group).

Preliminary multinomial logit regression took a bivariate format with green space as the sole predictor of sleep duration. The 259 319 participants were nested within 11 719 CCDs. Compared to participants reporting 8 h sleep as the base category, the risk of shorter sleep durations was lower for those with access to more green space. For example, the RRRs for participants with 80%+ versus less than 20% green space was 0.86 (95% CI 0.81 to 0.92) for durations between 6 and 7 h, and 0.68 (95% CI 0.57 to 0.80) for less than 6 h sleep. In contrast, there was no association between neighbourhood green space and the risk of longer sleep durations between 9 and 10 h (RRR 1.06, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.14), or over 10 h (RRR 0.85, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.03).

These results appeared to corroborate our hypothesis. However, this was founded on the basis that greener neighbourhoods stimulate mental health and more active lifestyles, which would then promote a healthier duration of sleep. Ergo, we expected that the association between green space and sleep duration would be explained by controls for mental health and physical activity. Adding the K10 variable showed participants at a high risk of psychological distress were more likely to report durations of sleep less and also more than 8 h (p<0.001). Conversely, adding physical activity to the model did not result in a significant association with sleep duration. Unexpectedly, and counter to our hypothesis, adjusting for these variables had negligible impact on the association between green space and sleep duration.

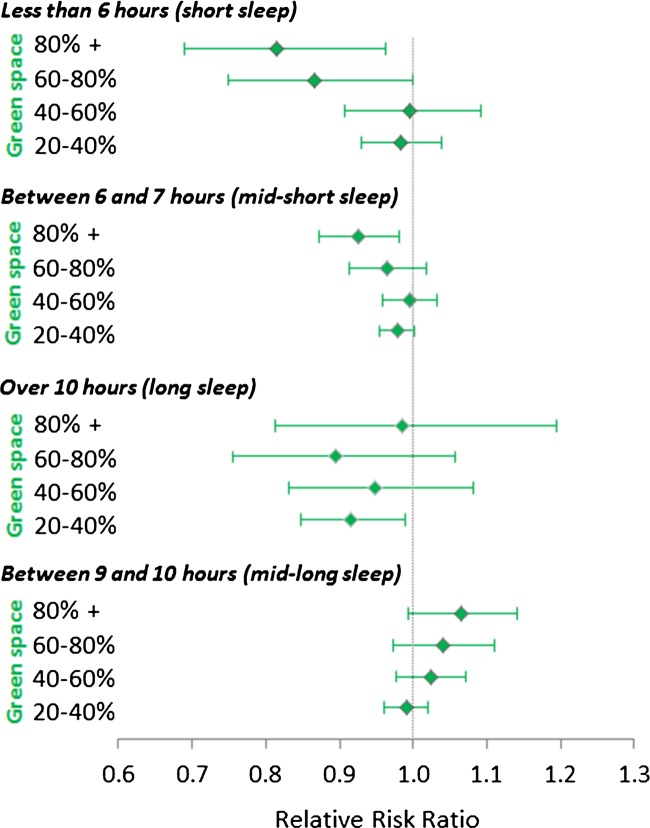

The final step was to interrogate the consistency of the green space parameters against other factors shown to be associated with short and long sleep duration. These variables were added sequentially to the previous model, with figure 1 illustrating the results of the final multinomial logit regression. Many characteristics of individuals were associated with sleep duration in line with previous work, such as unemployment and sleep less than 6 h (RRR 1.20, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.32) and more than 10 h (RRR 3.17, 95% CI 2.66 to 3.78). Participants in more affluent and geographically remote neighbourhoods were also at a lower risk of short and long sleep durations (p<0.001). Controlling for all of these variables did attenuate the negative association between green space and short sleep duration, but not fully. For participants with access to 80%+ green space within their neighbourhood compared with those with less than 20%, the RRR of sleeping between 6 and 7 h was 0.92 (95% CI 0.87 to 0.98) and 0.81 (95% CI 0.69 to 0.96) for sleep duration of less than 6 h in duration. There remained no association between green space exposure and sleep duration of more than 8 h.

Figure 1.

Association between proximity to green space and duration of sleep (fully adjusted). *Reference group=less than 20% green space. **Multinomial logit regression with robust SEs and base category comprising participants reporting 8 h sleep duration. Models were adjusted for: age, gender, Kessler scale of psychological distress, physical activity (measured by the Active Australia survey), weight status, couple status, ethnicity, country of birth, annual household income, highest qualifications, economic status, language spoken at home, number of alcoholic drinks consumed per week, smoking status, social support, the Socio-Economic Index for Areas (SEIFA) ‘Index of Relative Socio-Economic Advantage/Disadvantage’, and the ‘Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia’ (ARIA).

Discussion

As countries invest in large-scale green space planning policies,4 5 it would be prudent to ask whether parks and other forms of natural environment have any other health benefits aside from those that are already widely reported (namely, better mental health and increased physical activity). This study has demonstrated that people who live in greener environs are more likely to achieve a healthier duration of sleep. The protective effect of green space was isolated to guarding against the risk of short sleep (less than 8 h), with no association found for longer sleeps. These results were consistent after controlling for factors already known to be associated with short and long sleep and, surprisingly, were not explained by indicators of mental health and physical activity. The significance of these findings are put in context when one considers that sleep durations of less than 6 h are consistently associated with many of the major chronic health conditions15–19 that threaten the sustainability of health systems.40 41 As such, these results suggest that large-scale investments in green space policy could have a wider public health benefit than has been previously acknowledged.

Restoration from access to nature can occur directly,1 although exposure to green space is undoubtedly entwined, to a potentially large extent, with active lifestyles for which parks and other public open spaces are attractive environments for participation.42 This makes the finding that green space was associated with a healthier duration of sleep, irrespective of psychological distress or participation in physical activity, more intriguing. One possible explanation is that the physical activity variable measures participation, but not with any specific reference to the place in which it occurs. Participants scoring higher on the physical activity variable therefore do not necessarily perform those activities in the green spaces where they live and this interaction between behaviour and environment may be important to control.43 Another plausible mechanism is the dispersal of traffic density 44 and noise pollution in areas with more green space, which could otherwise have a detrimental influence on sleep duration.45 46 However, no measure of traffic density or noise pollution was available for this study. Thus, while more green space appears to be protective against a short duration of sleep, it is not yet clear whether this is demonstrably because of a direct effect on restoration that is not picked up by the K10, or if it operates via other structural processes operating at the neighbourhood level. Further research on the spatial patterning of sleep duration that accounts for other structural variables, such as noise pollution, is warranted to isolate the potentially causal mechanism(s) at play.

This study benefited from a large sample size and an objective measure of green space. However, the focus on a population of 45 years and older limits the generalisability to younger people, for whom further studies are advised. The survey response rate was 18%, though previous work has shown that results from the 45 and Up Study are comparable to those from a representative survey.27 While the cross-sectional design limits prospects for causal inference, the ability to detect these types of effects might not necessarily be enhanced with longitudinal data, as contemporaneous exposure to green space, rather than one that is temporally lagged may be what counts most for determining sleep duration. Longitudinal studies would nevertheless be useful for testing hypotheses related to temporal effects and also for exploring potential confounding produced by the possibility of individuals with a propensity for healthier durations of sleep selecting into neighbourhoods containing more green space. Follow-up of the 45 and Up Study will afford these opportunities, in addition to tracking the longer-term benefits of green space for health more generally.

It is plausible that sleep duration varies across the week and during the day (eg, naps), particularly between weekdays and weekends, but the measure of sleep available in the 45 and Up Study was generalist and could not facilitate these more detailed enquiries. Similarly, the Active Australia Survey is a measure of overall physical activity, but did not afford a distinction between leisure and other types (eg, active travel). Finally, while previous work has shown that different measures of green space yield similar associations with health outcomes,47 we recognise that not all green spaces are the same and future work should explore whether variation in subjective quality48 or type49 (eg, parks vs conservation areas) results in systematic differences in health outcomes, including sleep duration.

In conclusion, this study has found that more green space within the neighbourhood of residence is associated with a healthier duration of sleep among a large sample of Australians aged 45 and over. This association appeared to be robust to controls for mental health, physical activity and other possible individual-level confounders, though unmeasured phenomena operating at the neighbourhood level, such as traffic density, ought to be explored as data becomes available. As it stands, people living in greener areas tend to be at a lower risk of short sleep duration and this could have important subsequent impacts on health, including obesity and cardiovascular disease. It is also plausible that healthier sleep durations promoted by exposure to green space may aid mental health and participation in physical activity. As such, future studies employing longitudinal techniques may consider investigating sleep duration as a possible mediator of associations between green space and health outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: TAB, XF and GSK conceived and designed the experiments. TAB and XF performed the experiments. TAB and XF analysed the data. TAB, XF and GSK wrote the paper. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee approved the 45 and Up Study. Local ethical approval for this study was awarded by the University of Western Sydney.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Bowler DE, Buyung-Ali LM, Knight TM, et al. A systematic review of evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public Health 2010;10:456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee ACK, Maheswaran R. The health benefits of urban green spaces: a review of the evidence. J Public Health 2010;33:212–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lachowycz K, Jones AP. Greenspace and obesity: a systematic review of the evidence. Obes Rev 2011;12:e183–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nilsson K, Sangster M, Konijnendijk CC. Introduction. In: Nilsson K, Sangster M, Gallis C, Hartig T, de Vries S, Seeland K, Schipperijn J, eds. Forests, trees and human health. The Netherlands: Springer, 2011:1–19 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Australian Government Our cities our future: a national urban policy for a productive, sustainable and liveable future. Canberra: Department of Infrastructure and Transport, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sternberg EM. Healing spaces: the science of place and well-being. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaplan R, Kaplan S. The experience of nature: a psychological perspective. Cambridge: University Press, 1989 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ulrich RS. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 1984;224:420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bauman AE. Updating the evidence that physical activity is good for health: an epidemiological review 2000–2003. J Sci Med Sport 2004;7:6–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giles-Corti B, Broomhall MH, Knuiman M, et al. Increasing walking: how important is distance to, attractiveness, and size of public open space? Am J Prev Med 2005;28:169–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Astell-Burt T, Feng X, Kolt GS. Neighbourhood green space is associated with more frequent walking and moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) in middle-to-older aged adults. Findings from 203 883 Australians in The 45 and Up Study. Br J Sports Med. Published Online First: 30 April 2013.10.1136/bjsports-2012-092006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Astell-Burt T, Feng X, Kolt GS. Greener neighborhoods, slimmer people? Evidence from 246 920 Australians. Int J Obes. [Epub ahead of print 5 March 2013].10.1038/ijo2013.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knutson KL, Turek FW. The U-shaped association between sleep and health: the 2 peaks do not mean the same thing. Sleep 2006;9:881–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magee CA, Caputi P, Iverson DC. Relationships between self-rated health, quality of life and sleep duration in middle aged and elderly Australians. Sleep Med 2011;12:346–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magee CA, Iverson DC, Caputi P. Sleep duration and obesity in middle-aged Australian adults. Obesity 2009;18:420–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cappuccio FP, Taggart FM, Kandala NB, et al. Meta-analysis of short sleep duration and obesity in children and adults. Sleep 2008;31:619–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cappuccio FP, Cooper D, D Elia L, et al. Sleep duration predicts cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur Heart J 2011;32:1484–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chaput JP, Després J-P, Bouchard C, et al. Association of sleep duration with type 2 diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetologia 2007;50:2298–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knutson KL, Spiegel K, Penev P, et al. The metabolic consequences of sleep deprivation. Sleep Med Rev 2007;11:163–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kripke DF, Garfinkel L, Wingard DL, et al. Mortality associated with sleep duration and insomnia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002;59:131–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heslop P, Smith GD, Metcalfe C, et al. Sleep duration and mortality: the effect of short or long sleep duration on cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in working men and women. Sleep Med 2003;3:305–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hublin C, Partinen M, Koskenvuo M, et al. Sleep and mortality: a population-based 22-year follow-up study. Sleep 2007;30:1245–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ford DE, Kamerow DB. Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders. JAMA 1989;262:1479–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steptoe A, O'Donnell K, Marmot M, et al. Positive affect, psychological well-being, and good sleep. J Psychosom Res 2008;64:409–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magee CA, Iverson DC, Caputi P. Factors associated with short and long sleep. Prev Med 2009;49:461–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.45 and Up Study Collaborators Cohort Profile: The 45 and Up Study. Int J Epidemiol 2008;37:941–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mealing NM, Banks E, Jorm LR, et al. Investigation of relative risk estimates from studies of the same population with contrasting response rates and designs. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010;10:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Australian Bureau of Statistics Research Paper. Socioeconomic indexes for areas: introduction, use and future directions. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Magee CA, Kritharides L, Attia J, et al. Short and long sleep duration are associated with prevalent cardiovascular disease in Australian adults. J Sleep Res 2012;21:441–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maas J, Verheij RA, Groenewegen PP, et al. Green space, urbanity, and health: how strong is the relation? J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:587–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Vries S, Verheij RA, Groenewegen PP, et al. Natural environments-healthy environments? An exploratory analysis of the relationship between greenspace and health. Environ Plann A 2003;35:1717–32 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med 2002;32:959–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Furukawa TA, Kessler RC, Slade T, et al. The performance of the K6 and K10 screening scales for psychological distress in the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Psychol Med 2003;33:357–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Australian Bureau of Statistics Information paper: use of the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale in ABS Health Surveys, Australia. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feng X, Astell-Burt T, Kolt GS. Ethnic density, social interactions and psychological distress: evidence from 226 487 Australian adults. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare The active Australia survey: a guide and manual for implementation, analysis and reporting. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koenig HG, Westlund RE, George LK, et al. Abbreviating the Duke Social Support Index for use in chronically ill elderly individuals. Psychosomatics 1993;34:61–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. UCLA: Academic Technology Services SCG. Analyzing Correlated (Clustered) Data, 2008.

- 39.Williams R. A note on robust variance estimation for cluster-correlated data. Biometrics 2000;56:645–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang YC, McPherson K, Marsh T, et al. Health and economic burden of the projected obesity trends in the USA and the UK. Lancet 2011;378:815–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hossain P, Kawar B, El Nahas M. Obesity and diabetes in the developing world—a growing challenge. N Engl J Med 2007;356:213–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hug SM, Hartig T, Hansmann R, et al. Restorative qualities of indoor and outdoor exercise settings as predictors of exercise frequency. Health Place 2009;15:971–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mitchell R. Is physical activity in natural environments better for mental health than physical activity in other environments? Soc Sci Med 2012;91:130–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gidlöf-Gunnarsson A, Öhrström E. Noise and well-being in urban residential environments: the potential role of perceived availability to nearby green areas. Landscape Urban Plann 2007;83:115–26 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Basner M, Müller U, Elmenhorst E-M. Single and combined effects of air, road, and rail traffic noise on sleep and recuperation. Sleep 2011;34:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muzet A. Environmental noise, sleep and health. Sleep Med Rev 2007;11:135–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mitchell R, Astell-Burt T, Richardson EA. A comparison of green space measures for epidemiological research. J Epidemiol Community Health 2011;65:853–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Francis J, Wood LJ, Knuiman M, et al. Quality or quantity? Exploring the relationship between Public Open Space attributes and mental health in Perth, Western Australia. Soc Sci Med 2012;74:1570–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fan Y, Das KV, Chen Q. Neighborhood green, social support, physical activity, and stress: assessing the cumulative impact. Health Place 2011;17:1202–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.