Abstract

Introduction

Inspiratory muscle training (IMT) has been applied during pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). However, it remains unclear if the addition of IMT to a general exercise training programme leads to additional clinically relevant improvements in patients with COPD. In this study, we will investigate whether the addition of IMT to a general exercise training programme improves 6 min walking distance, health-related quality of life, daily physical activity and inspiratory muscle function in patients with COPD with inspiratory muscle weakness.

Methods and analysis

Patients with COPD (n=170) with inspiratory muscle weakness (Pi,max <60 cm H2O or <50%pred) will be recruited to a multicentre randomised placebo controlled trial of IMT and allocated into one of the two groups. Patients in both groups will follow a 3 month general exercise training programme, in combination with home-based IMT. IMT will be performed with a recently developed device (POWERbreathe KH1). This device applies an inspiratory load that is provided by an electronically controlled valve (variable flow resistive load). The intervention group (n=85) will undertake an IMT programme at a high intensity (≥50% of their Pi,max), whereas the placebo group (n=85) will undertake IMT at a low training intensity (≤10% of Pi,max). Total daily IMT time for both groups will be 21 min (6 cycles of 30 breaths). Improvement in the 6 min walking distance will be the primary outcome. Inspiratory muscle function, health-related quality of life and daily physical activity will be assessed as secondary outcomes.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval has been obtained from relevant centre committees and the study has been registered in a publicly accessible clinical trial database. The results will be easily interpretable and should immediately be communicated to healthcare providers, patients and the general public.

Results

This can be incorporated into evidence-based treatment recommendations for clinical practice.

ClinicalTrials.gov

Article summary.

Article focus

Inspiratory muscle dysfunction occurs in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and is associated with dyspnoea and decreased exercise capacity.

What are the additional functional and health benefits of adding home-based inspiratory muscle training (IMT) to a general exercise training programme in COPD patients with inspiratory muscle weakness?

Key messages

This multicentre randomised controlled trial will investigate and report on the additional improvements in exercise tolerance after adding IMT to a 3 months general exercise training programme. Inspiratory muscle function, health-related quality of life and daily physical activity will be assessed as secondary outcomes.

The study will focus on patients with COPDand inspiratory muscle weakness defined as Pi,max <60 cm H2O or <50%pred.

The variable flow resistive training method applies a specific training stimulus and allows full monitoring of the compliance with the home-based IMT.

Strengths and limitations of this study

In contrast to previous studies, we designed a large, adequately powered, multicentre randomised controlled trial to investigate the effects of IMT in patients with COPD and inspiratory muscle weakness. The results from this study will help to clarify whether adjunctive IMT leads to greater functional improvements (exercise capacity, quality of life, participation in daily activity and symptoms) than exercise training alone.

The results will be focused on effects in COPD patients with inspiratory muscle weakness. The results of this study will therefore primarily be applicable in COPD patients with inspiratory muscle weakness.

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major cause of chronic morbidity and mortality worldwide.1 2 COPD is characterised by persistent expiratory flow limitation which is usually progressive.3 Dyspnoea is the most prominent exercise-limiting symptom of the disease,4 which leads to chronic avoidance of physical activities. Consequently, low-physical activity levels contribute to skeletal muscle deconditioning and exercise capacity reduction, which impact negatively on health-related quality of life.5 6 Inspiratory muscle dysfunction is another extrapulmonary manifestation, which is often present in patients with COPD.7 8 It contributes to hypoxaemia, hypercapnia, dyspnoea and decreased exercise tolerance.9–11 Pulmonary rehabilitation including exercise training, education, nutritional intervention and psychosocial support is a standard care for patients with COPD to counteract extrapulmonary disease manifestations.6 12 13 Inspiratory muscle training (IMT) has also been applied frequently and is extensively studied in recent years in patients with COPD.14 From meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in patients with COPD, it can been concluded that IMT as a stand-alone therapy improves inspiratory muscle function (strength and endurance), decreases symptoms of dyspnoea and improves exercise capacity.14 15 The value of IMT as an add-on to a general exercise training programme is, however, still under debate.16–19 While IMT always results in significant improvements in inspiratory muscle function, its additional effects on more clinically relevant outcomes (eg, functional exercise capacity and quality of life) are insufficiently supported by scientific evidence so far.14 From subgroup analyses in the most recent meta-analysis, it was concluded that significant additional effects of IMT on more clinically relevant outcomes are more likely to be found in patients with inspiratory muscle weakness.12 This was previously defined as a maximal inspiratory mouth pressure (Pi,max) of less than 60 cm H2O.14 It has therefore been recommended that future studies in patients with COPD should focus specifically on patients with more pronounced inspiratory muscle weakness.14 20 It was recently shown that adjunctive IMT led to significantly greater functional improvements in a well-designed RCT in patients with chronic heart failure selected for inspiratory muscle weakness.21 Comparable RCTs in patients with COPD are so far lacking.14 We are therefore carrying out a large, adequately powered, multicentre RCT on the effects of IMT as an adjunct therapy to a general exercise training programme in patients with COPD with inspiratory muscle weakness. Recommendations on the use of IMT as an adjunct to general exercise training in these patients in international guidelines are ambiguous.12 The outcome of this study will therefore have a direct impact on clinical practice, as the results will clarify whether adjunctive IMT leads to superior clinically relevant improvements for patients with COPD. Functional outcomes of relevance to patients (exercise capacity, quality of life, participation in daily physical activity and symptoms) were therefore chosen as the main outcomes.

One of the hypotheses that links enhanced inspiratory muscle function to improvements in exercise capacity is that IMT should allow the respiratory system of patients with COPD to work more comfortably at high lung volumes during exercise.22 In the present study, we will use a recently developed IMT device that applies a variable resistance provided by an electronically controlled valve (variable flow resistive load). In contrast to the traditionally applied threshold loading, this variable flow resistive load is specifically challenging the inspiratory muscles at higher lung volumes, and may lead to larger training effects in patients with COPD who develop dynamic hyperinflation during exercise. Besides these potentially beneficial characteristics of the applied load, another advantage of the device is the ability to store home-based training data for up to 40 sessions. Continuous registrations of pressure and flow at 500 Hz provide data on the external work of breathing and enable the verification of quantity as well as quality of unsupervised training sessions. The latter is of particular importance since 85% of the training sessions during this RCT will be performed by patients at their homes without supervision.

Aims

This study will examine the effects of adding a well-controlled, high-intensity IMT programme to a 3-month general exercise training programme, using a large, multicentre, randomised controlled design, in patients with COPD and inspiratory muscle weakness. Outcomes will be exercise capacity (primary outcome), inspiratory muscle function, health-related quality of life (HRQL) and participation in daily physical activity.

Hypotheses

We hypothesise that the addition of IMT to a general exercise training programme in patients with COPD and inspiratory muscle weakness will result in superior improvements exercise capacity, inspiratory muscle function, HRQL and daily physical activity, compared with general exercise training alone.

Methods

Patients

All patients with spirometry-proven COPD who are referred for outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation will be screened for inclusion. Only patients with inspiratory muscle weakness (Pi,max <60 cm H2O or <50% predicted) will be eligible to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria consist of (1) diagnosed psychiatric or cognitive disorders; (2) progressive neurological or neuromuscular disorders; (3) severe orthopaedic problems having a major impact on daily activities and (4) previous inclusion in rehabilitation programme (<1 year).

Study design

Patients will be informed about the study protocol prior to the start of the rehabilitation programme. Informed consent will be obtained at that time. Patients will be randomised into an intervention and a placebo group. Group allocation will be performed by simple randomisation using sealed opaque envelopes in random block sizes of four and six (order unknown to investigators).23

Both groups will follow a general exercise training programme as described previously.24 The intervention group will receive an additional IMT programme described to the patients as ‘resistance training’ at high intensity (≥ 50% Pi,max), whereas the placebo group will receive an IMT intervention described to patients as ‘endurance training’ at a low training intensity (≤10% Pi,max).

Measurements of primary and secondary endpoints will be undertaken before and after 3 months of rehabilitation. All tests will be performed by experienced investigators who are blinded to group allocation. To ensure consistency between the centres, all assessments will be performed according to the instructions agreed upon and described in a manual of procedures and an instructional video, even if they may differ slightly from usual local procedures. To further improve the consistency, the five centres will regularly receive a newsletter to update them on the progress of the study and to share eventual technical problems between centres. Staff from all participating centres will be able to contact the coordinating centre in Leuven by email or telephone in case they should have any questions concerning the study.

To detect a minimally clinically important difference between groups of 26 m in the 6 min walking distance (6MWD),25 assuming a SD of the within group differences in the 6MWD at the end of the intervention period of 60 m in both groups with a degree of certainty (statistical power) of 80% and a risk for a type 1 error (α) <5%, a sample size for both groups of 85 patients is needed, given an anticipated dropout rate of 30%. This study will therefore be performed as a multicentre RCT to ensure the inclusion of 170 patients within a time frame of 2 years. Besides the lead centre at the University Hospital in Leuven, Belgium, patients will also be recruited in the University Hospital Gent, Belgium; Schön Klinik Berchtesgadener Land, Germany; University Hospital Nijmegen, the Netherlands; and Laval University Quebec, Canada. Each of the five centres is expected to include between 30 and 40 patients within the 2-year inclusion period.

In accordance with the Belgian law relating to experiments on humans dated 7 May, 2004, KU/UZ Leuven shall assume, even without fault, the responsibility of any damages incurred by a subject which linked directly or indirectly to participation in the study, and shall therefore provide compensation through its insurance programme. All collaborating sites will have adequate insurance coverage for (1) Medical professional and/or medical malpractice liability, (2) general liability and (3) other possible damages resulting from the Study at the institution.

Interventions

General exercise training

Patients in both groups will follow a 3-month general exercise training programme. Patients will perform cycling, treadmill walking, stair climbing, arm ergometry and resistance training of arm as well as leg muscles.26 Training frequency will be three sessions per week, resulting in a total of 36 training sessions. Duration of the training session will increase from 40–60 min at the start of the programme to 60–90 min after 3 months. Patients will perform endurance training or interval training at moderate to high intensity (initially 60–70% of maximal workload). The overall training intensity will be increased gradually during the course of the programme using a CR10 Borg Scale rating of 4–6 on dyspnoea sensation or leg effort as a means of maintaining training overload.27 Physiotherapists providing this intervention will be blinded to group allocation of patients.

Inspiratory muscle training programme

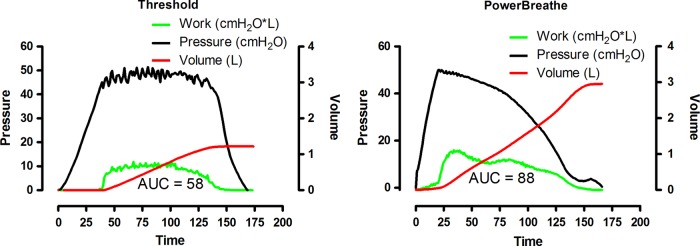

Patients will receive either high-intensity IMT (‘strength training’=intervention group) or low-intensity placebo IMT (‘endurance training’=placebo group). The training load in this study will be adjusted according to data from a previously performed pilot study about a home-based, high-intensity IMT programme in patients with COPD with inspiratory muscle weakness.28 Total daily training time for both groups will be 21 min, consisting of 6 cycles of 30 breaths (2 cycles, 3 times daily in the intervention group or 3 cycles, 2 times daily in the control group). There will be approximately 3.5 min of resistive breathing during every cycle, each followed by 1 min of resting. Patients will train 7 days/week, for 12 weeks using the Powerbreathe KH1 device (POWERbreatheKH1, HaB International Ltd, Southam, UK). This handheld device applies a variable resistance provided by an electronically controlled valve (variable flow resistive load). Loading is maintained at the same relative intensity throughout the breath, by reducing the absolute load to accommodate the pressure–volume relationship of the inspiratory muscles. The application of a tapered load allows patients to get close to maximal inspiration, even at high-training intensities (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison between constant threshold (threshold) and variable resistive inspiratory muscle training (POWERbreathe KH1).

Figure 1 illustrates a comparison of a single breath (training at an intensity of 60% Pi,max) using a conventional constant threshold loading device, with that of a variable flow resistive loading device (POWERbreathe KH1).28 It is apparent from this figure that, in contrast to the threshold loading, the variable flow resistive load overloads the inspiratory muscles at higher lung volumes. Since one of the hypotheses that links enhanced inspiratory muscle function to improvements in exercise capacity is that IMT may allow the respiratory system of patients with COPD to work more comfortably at high lung volumes during exercise,22 we hypothesise that this variable flow resistive IMT should be better suited to reduce inspiratory effort (Pes/Pi,max) during whole body exercise. Besides these hypothetically beneficial characteristics of the applied load, a further advantage of the electronic leading device is the ability to store parameters of up to 40 IMT sessions. Continuous registrations of pressure and flow at 500 Hz provide data on the external work of breathing and enable us to control quantity as well as quality of unsupervised training sessions. This is of special importance since 85% of the training sessions during this RCT will be performed by patients at their homes without supervision. The device stores data on average mean pressure (cm H2O), average mean power per breath (watt), average peak flow per breath (L/s) and total work of breathing during one session of 30 breaths (joules). Patients will be instructed to perform fast and forceful inspirations and will be encouraged to achieve maximal inhalation and exhalation with every breath. This breathing pattern will be supported by acoustic signals from the loading device.

The intervention group will start training at 40% of their initial Pi,max. Intermediate measurements of Pi,max will be performed every week. These Pi,max values will be used to calculate the training load to be implemented the following week. In other words, the training load in each week will be increased continuously over time by adjusting to at least 50% of the Pi,max value recorded in the previous week. Rates of perceived inspiratory effort on a modified CR10 Borg Scale (4–6 of 10) will also be used to support decisions on training load increments. The control group will train at an inspiratory load of 10% of their initial Pi,max. This training intensity will not be changed during the study period. Each week, three training sessions will be performed under supervision at the outpatient clinic. During these supervised sessions, the results of unsupervised sessions will be evaluated and patients will receive instructions and feedback on their training efforts. Resting periods will be given as needed as long as the patients are able to complete the full volume of training prescribed. Training intensity in the intervention group will be adapted during these supervised sessions.

When patients experience acute exacerbations or respiratory infections, they will temporarily interrupt their participation in the rehabilitation and IMT programme. Based on the guidance from the treating pulmonologist, they will, however, return to the programme as quickly as possible. Periods of infections, exacerbations and hospitalisations will be registered and their stay in the programme will be prolonged in order to complete 12 weeks of IMT training programme.

Outcome measures

Table 1 provides an overview of the outcome measures at different time points in the study.

Table 1.

Outcome measurements

| Start | 3 months | |

|---|---|---|

| Screen | X | |

| Informed consent | X | |

| Respiratory muscle strength | X | X |

| Inspiratory muscle endurance | X | X |

| Maximal exercise capacity | X | X |

| Endurance exercise capacity | X | X |

| Six-minute walking distance | X | X |

| Daily physical activity (7 days) | X | X |

| Pulmonary function | X | X |

| Quadriceps force | X | X |

| Handgrip force | X | X |

| CRDQ | X | X |

| HADS | X | X |

CRDQ, Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire (HRQL); HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Respiratory muscle force

Maximal voluntary respiratory pressures will be registered at the mouth to assess respiratory muscle force. Measurements will be performed from total lung capacity for maximal expiratory pressure (Pe,max) or residual volume for maximal inspiratory pressure (Pi,max) using the technique proposed by Black and Hyatt.29 An electronic pressure transducer will be used (MicroRPM; Micromedical, Kent, UK). Assessments will be repeated at least five times (30 s recovery between attempts), and should be continued until at least good reproducibility has been achieved from the three best measurements (within 10 cm H2O difference among measurements). Reference values published by Rochester and Arora30 will be used to define normal respiratory muscle force.

Inspiratory muscle endurance

To measure inspiratory muscle endurance, patients will be asked to breathe against a submaximal inspiratory load provided by the flow resistive loading device (POWERbreathe KH1), until task failure. The inspiratory load that will be selected (typically between 50%and 60% of the Pi,max) will typically allow patients to continue breathing against the resistance for 3–7 min. Breathing instructions for patients will be the same as during the training sessions. Number of breaths, average duty cycle (inspiratory time as a fraction of the total respiratory cycle duration), average mean load, average mean power and total external inspiratory work will be recorded during the test by the handheld loading device. We have recently performed a validation of the parameters that are recorded during this test and found excellent agreement between the handheld loading device and measurements performed with external, laboratory measurement equipment.31 After 12 weeks of IMT, the endurance test will be repeated using an identical load. Improvements in endurance time and breathing parameters will be recorded.

Maximal exercise capacity (incremental exercise test)

Maximal exercise capacity will be assessed by a maximal incremental cycle exercise test (Ergometrics 900, Ergoline, Bitz, Germany). After a 2 min resting period and 3 min of unloaded cycling, patients will start cycling at a load of 20 w. Load will then be increased by 10 w/min and patients will cycle until symptom limitation. Oxygen uptake, carbon dioxide output and ventilation will be measured breath by breath (Vmax series, SensorMedics, Anaheim, California, USA). Heart rate and oxygen saturation will be recorded continuously. Maximal oxygen uptake will be compared with normal values.32 The perception of dyspnoea and leg effort will be quantified at 2 min intervals during exercise and at the end of the test using the modified Borg scale.27 The development of dynamic hyperinflation during the exercise test will be assessed by recording the changes in end-expiratory lung volumes. Patients will be instructed to perform maximal inspiratory manoeuvers after a normal expiration during resting breathing and at the end of each level of exercise. Assuming a constant total lung capacity, a decrease in inspiratory capacity will indicate an increase in the end-expiratory lung volume, which indicates the degree of dynamic hyperinflation.33 Tidal volume (VT), inspiratory time (TI), total time of the respiratory cycle (TTOT) and respiratory frequency (fR) will be assessed. The TI/TTOT (duty cycle) represents the proportion of the breath during which the inspiratory muscles are contracting.

Endurance exercise capacity (constant work rate test)

A constant power output cycle test until symptom limitation will be performed at 80% of the maximal power output (in Watts) that was reached during the initial incremental exercise test (Ergometrics 900, Ergoline, Bitz, Germany). Oxygen uptake, carbon dioxide output and minute ventilation will be measured breath by breath (Vmax series, ). Breathing pattern and dynamic hyperinflation will be monitored as described previously for the incremental cardiopulmonary exercise test. Heart rate and oxygen saturation will be monitored continuously. The perception of dyspnoea and leg effort will be quantified at 2 min intervals during exercise and at the end of the test using the modified CR10 Borg scale.27

Six-minute walking distance

Functional exercise performance will be measured using a 6 min walking test in a 50 m corridor. Standardised encouragement will be provided.34 The best of the two tests separated by recovery time of 30 min will be used and related to reference values.35 Oxygen saturation, heart rate and symptoms of leg effort and dyspnoea will be recorded before and after the test.

Physical activity monitoring

Measurements will be performed with an accelerometer-based activity monitor (DynaPort Minimod, McRoberts BV, The Hague, The Netherlands). The Minimod is a small (64×62×13 mm) and lightweight device (68 g, including batteries) that contains a three-axial piezocapacitive sensor measuring at high time-resolution (100 Hz). Analysis of raw data allows for the classification of intensity, duration and frequency of movement. Different postures and walking are identified and energy expenditure is estimated. The Minimod has been validated in patients with COPD.36 Assessments will be undertaken on seven consecutive days during waking hours.

Pulmonary function

Spirometry and whole body plethysmography will be performed according to the European Respiratory Society guidelines for pulmonary function testing (Vmax Autobox, Sensor Medics, Bilthoven, The Netherlands).37 Diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide will be measured by the single breath method (Sensor Medics 6200, Bilthoven, The Netherlands).38

Peripheral muscle force

Isometric quadriceps force will be quantified using a Cybex Norm Dynamometer (Cybex Norm, Enraf Nonius, Delft, The Netherlands). Peak extension torque will be measured at 60° of knee flexion. At least three measurements will be obtained and the highest reproducible value (within 11%) will be taken into analysis. Reference values have been developed in our laboratory.39

Isometric hand grip force will be measured using a hydraulic hand grip dynamometer (Jamar Preston, Jackson, Michigan). Peak force will be assessed with the elbow fixed to the rib cage and flexed 90° and with the wrist in neutral position. At least three measurements will be obtained and the highest reproducible value will be taken into analysis and related to reference values.26

Health-related quality of life

The Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire (CRDQ) will be used to assess HRQL.40 This 20-item questionnaire scores quality of life in four domains (dyspnoea, mastery, emotional functioning and fatigue) and has been validated in the Dutch, German and French language.41–43 The total score can range from 20 to 140 with higher scores indicating better quality of life.

Anxiety and depression

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) will be used to assess emotional distress.44 The HADS consists of 14 items and has separate scores for anxiety (7 items) and depression (7 items). A score of 11 or greater on either of the subscales suggests clinically significant symptoms of anxiety or depression.

Statistical analysis

Differences in primary and secondary outcomes between groups after 3 months of intervention will be compared adjusting for baseline differences using analysis of covariance.45 An ‘intention-to-treat’ as well as a ‘per-protocol’ analysis will be carried out to compare outcomes between groups.

Ethics and dissemination

The results from the RCT of IMT will be submitted for publication.

Discussion

This large, adequately powered, multicentre RCT will investigate the effects of IMT as an adjunct to a general exercise training programme. Outcomes will be exercise capacity (primary outcome), HRQL and participation in daily physical activity in the selected patients with COPD who have pronounced inspiratory muscle weakness. The IMT in this RCT will be performed using the variable flow resistive loading device described previously (POWERbreatheKH1, and validated.31 Besides the hypothetically beneficial characteristics of the applied load described above, a further advantage of this device is the ability to store training parameters of up to 40 sessions. Continuous recording of pressure and flow enables us to monitor the quantity as well as quality of unsupervised training sessions. The latter is of special importance, since 85% of IMT sessions will be undertaken by patients in their homes, without supervision.

We anticipate that the outcomes of this study will be of direct relevance to clinical practice. The results of this study should therefore be incorporated immediately into evidence-based treatment recommendations for clinical practice. During the communication of these recommendations, it will be of special importance to stress that the results obtained in this RCT will be limited to the selected group of patients with COPD, that is, those with inspiratory muscle weakness.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: DL is the principal investigator and together with RG and NC designed and established the study. All authors are responsible for the selection of measures, recruitment and data collection. NC and DL are responsible for data analysis. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests: AKM acknowledges a beneficial interest in the POWERbreathe inspiratory muscle trainers in the form of a share of royalty income to the University of Birmingham and Brunel University. She also provides consultancy services to the POWERbreathe International Ltd.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval has been obtained from relevant centre committees.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Further details of the study protocol can be requested from the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Mannino DM, Buist AS. Global burden of COPD: risk factors, prevalence, and future trends. Lancet 2007;370:765–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:532–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2011 Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD. http://www.goldcopd.org/.Ref Type: Internet Communication. [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Donnell DE, Travers J, Webb KA, et al. Reliability of ventilatory parameters during cycle ergometry in multicentre trials in COPD. Eur Respir J 2009;34:866–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamilton N, Killian KJ, Summers E, et al. Muscle strength, symptom intensity, and exercise capacity in patients with cardiorespiratory disorders. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;152:2021–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lacasse Y, Martin S, Lasserson TJ, et al. Meta-analysis of respiratory rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A Cochrane systematic review. Eura Medicophys 2007;43:475–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Decramer M, Demedts M, Rochette F, et al. Maximal transrespiratory pressures in obstructive lung disease. Bull Eur Physiopathol Respir 1980;16:479–90 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polkey MI, Kyroussis D, Hamnegard CH, et al. Diaphragm strength in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;154:1310–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laghi F, Tobin MJ. Disorders of the respiratory muscles. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;168:10–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Begin P, Grassino A. Inspiratory muscle dysfunction and chronic hypercapnia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis 1991;143:905–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gosselink R, Troosters T, Decramer M. Peripheral muscle weakness contributes to exercise limitation in COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;153:976–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nici L, Donner C, Wouters E, et al. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement on pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;173:1390–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ries AL, Bauldoff GS, Carlin BW, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation: joint ACCP/AACVPR evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2007;131:4S–42S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gosselink R, De VJ, Van den Heuvel SP, et al. Impact of inspiratory muscle training in patients with COPD: what is the evidence? Eur Respir J 2011;37:416–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geddes EL, O'Brien K, Reid WD, et al. Inspiratory muscle training in adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an update of a systematic review. Respir Med 2008;102:1715–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ambrosino N. The case for inspiratory muscle training in COPD. Eur Respir J 2011;37:233–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McConnell AK. CrossTalk opposing view: respiratory muscle training does improve exercise tolerance. J Physiol 2012;590:3397–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel MS, Hart N, Polkey MI. CrossTalk proposal: training the respiratory muscles does not improve exercise tolerance. J Physiol 2012;590:3393–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polkey MI, Moxham J, Green M. The case against inspiratory muscle training in COPD. Against Eur Respir J 2011;37:236–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Decramer M. Response of the respiratory muscles to rehabilitation in COPD. J Appl Physiol 2009;107:971–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winkelmann ER, Chiappa GR, Lima CO, et al. Addition of inspiratory muscle training to aerobic training improves cardiorespiratory responses to exercise in patients with heart failure and inspiratory muscle weakness. Am Heart J 2009;158:768–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo YM, Hopkinson NS, Polkey MI. Tough at the top: must end-expiratory lung volume make way for end-inspiratory lung volume? Eur Respir J 2012;40:283–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doig GS, Simpson F. Randomization and allocation concealment: a practical guide for researchers. J Crit Care 2005;20:187–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Troosters T, Gosselink R, Decramer M. Short- and long-term effects of outpatient rehabilitation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized trial. Am J Med 2000;109:207–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Puhan MA, Chandra D, Mosenifar Z, et al. The minimal important difference of exercise tests in severe COPD. Eur Respir J 2011;37:784–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mathiowetz V, Dove M, Kashman N, et al. Grip and pinch strength: normative data for adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1985;66:69–72 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borg GA. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1982;14:377–81 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Langer D, Jacome C, Hoffman M, et al. Comparison of two high intensity inspiratory muscle training programs in patients with COPD: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;187:A2566 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Black LF, Hyatt RE. Maximal respiratory pressures: normal values and relationship to age and sex. Am Rev Respir Dis 1969;99:696–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rochester DF, Arora NS. Respiratory muscle failure. Med Clin North Am 1983;67:573–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Langer D, Jacome C, Charususin N, et al. Measurement validity of an electronic inspiratory loading device during a loaded breathing task in patients with COPD. Respir Med 2013;107:633–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones NL, Makrides L, Hitchcock C, et al. Normal standards for an incremental progressive cycle ergometer test. Am Rev Respir Dis 1985;131:700–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yan S, Kaminski D, Sliwinski P. Reliability of inspiratory capacity for estimating end-expiratory lung volume changes during exercise in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;156:55–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guyatt GH, Pugsley SO, Sullivan MJ, et al. Effect of encouragement on walking test performance. Thorax 1984;39:818–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Troosters T, Gosselink R, Decramer M. Six minute walking distance in healthy elderly subjects. Eur Respir J 1999;14:270–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langer D, Gosselink R, Sena R, et al. Validation of two activity monitors in patients with COPD. Thorax 2009;64:641–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J 2005;26:319–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.MacIntyre N, Crapo RO, Viegi G, et al. Standardisation of the single-breath determination of carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur Respir J 2005;26:720–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Decramer M, Lacquet LM, Fagard R, et al. Corticosteroids contribute to muscle weakness in chronic airflow obstruction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994;150:11-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guyatt GH, Berman LB, Townsend M, et al. A measure of quality of life for clinical trials in chronic lung disease. Thorax 1987;42:773–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Puhan MA, Behnke M, Frey M, et al. Self-administration and interviewer-administration of the German Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire: instrument development and assessment of validity and reliability in two randomised studies. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2004;2:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bourbeau J, Maltais F, Rouleau M, et al. French-Canadian version of the Chronic Respiratory and St George's Respiratory questionnaires: an assessment of their psychometric properties in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Can Respir J 2004;11:480–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wijkstra PJ, TenVergert EM, Van AR, et al. Reliability and validity of the chronic respiratory questionnaire (CRQ). Thorax 1994;49:465–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vickers AJ, Altman DG. Statistics notes: analysing controlled trials with baseline and follow up measurements. BMJ 2001;323:1123–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.