Abstract

Culex quinquefasciatus (the Southern house mosquito) is an important mosquito vector of viruses such as West Nile virus and St. Louis encephalitis virus as well of nematodes that cause lymphatic filariasis. It is one species within the Culex pipiens species complex and enjoys a distribution throughout tropical and temperate climates of the world. The ability of C. quinquefasciatus to take blood meals from birds, livestock and humans contributes to its ability to vector pathogens between species. We describe the genomic sequence of C. quinquefasciatus, its repertoire of 18,883 protein-coding genes is 22% larger than Ae. aegypti and 52% larger than An. gambiae with multiple gene family expansions including olfactory and gustatory receptors, salivary gland genes, and genes associated with xenobiotic detoxification.

Mosquitoes are the most important vectors of human disease, responsible for the transmission of pathogens that cause malaria (Anopheles), yellow fever and dengue (Aedes), lymphatic filariasis (Culex, Aedes, Anopheles), and West Nile encephalitis (Culex). Sequencing the Anopheles gambiae and Aedes aegypti genomes has provided important insights into the genomic diversity underlying the complexity of mosquito biology (1, 2). We describe the sequencing of the Culex quinquefasciatus (the Southern house mosquito) genome, which offers a reference genome from the third major taxonomic group of disease-vector mosquitoes. With over 1,200 described species, Culex is the most diverse and geographically widespread of these three mosquito genera, and apart from contributing to the spread of West Nile encephalitis, also transmits St. Louis encephalitis and other viral diseases, and is a major vector of the parasitic Wuchereria bancrofti nematode which causes the majority of 120 million current cases of lymphatic filariasis (3).

Taxonomy of the Culex pipiens species complex is the subject of a long-standing debate, an issue complicated by the occurrence of viable species hybrids in many geographic areas (reviewed in 4, 5). We followed the standard set by National Center for Biotechnology Information and refer to the species sequenced here as C. quinquefasciatus. The Johannesburg strain (JHB) of C. quinquefaciatus was established from a single pond in Johannesburg, South Africa, an area where two subspecies C. pipiens quinquefasciatus and C. pipiens pipiens are sympatric but have remained much more genetically distinct than the same two sympatric subspecies found in California (5).

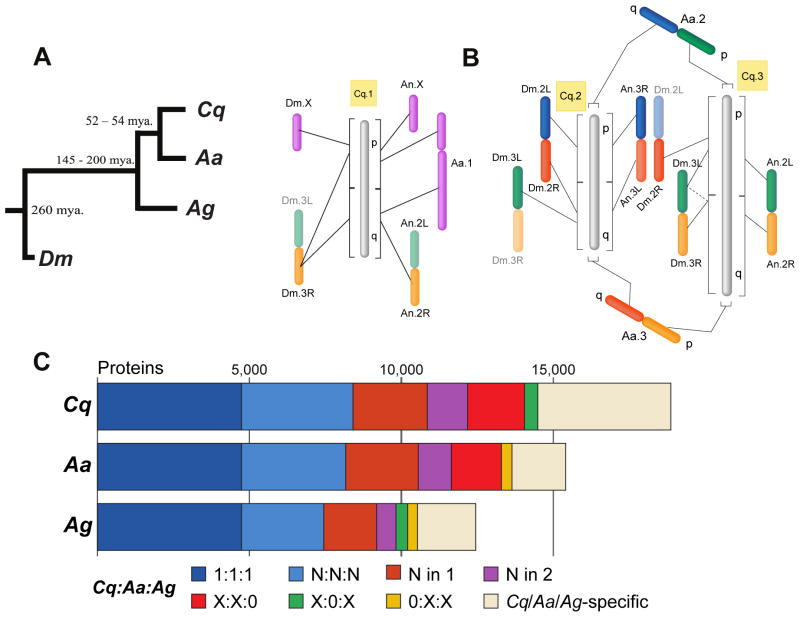

We were able to map 9% of the C. quinquefasciatus genes (1,768 genes) on the three chromosomes using published and new C. quinquefasciatus and Ae. aegypti markers (6). Of these mapped genes, 803 had An. gambiae orthologs and 641 had Drosophila melanogaster orthologs, consistent with the established species phylogeny (Fig. 1A). Examining correlations between chromosomal arms indicated whole chromosome conservation between C. quinquefasciatus, An. gambiae, and D. melanogaster (Fig. 1B, 6), whereas, and as suggested from earlier work (7), Ae. aegypti appears to have experienced an arm exchange between the two longest chromosomes following the Aedes/Culex divergence (Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

A) Codon-based estimates of DNA substitutions along the mosquito phylogeny, C. quinquefasciatus (Cq), Ae. aegypti (Aa), and An. gambiae (Ag) with D. melanogaster (Dm) as an outgroup. Dates of divergence were taken from previous studies (6). B) Chromosomal synteny between C. quinquefasciatus, Ae. aegypti, An. gambiae and D. melanogaster. Plain lines indicate main orthologous chromosomes and dashed lines secondary orthologous chromosomes. Colors indicate syntenic chromsome arms. Chromosomes not to scale. C) Orthology delineation among the protein-coding gene repertoires of the three sequenced mosquito species. Categories of orthologous groups with members in all three species include single-copy orthologs in each species (1:1:1), and multi-copy orthologs in all three (N:N:N), one (N in 1), or two (N in 2) species. Remaining orthologous groups include single or multi-copy groups with genes in only two species (X:X:0, X:0:X, 0:X:X). The remaining fractions in each species (Cq/Aa/Ag-specific) exhibit no orthology with genes in the other two mosquitoes.

A significant fraction of the assembled C. quinquefasciatus genome (29%) was composed of transposable elements (TEs) (Fig. S2); less than the TE fraction of Ae. aegypti (42% – 47%) but greater than that of An. gambiae (11% – 16%) (1, 2, 6). This suggests an increased level of TE activity and/or reduced intensity of selection against TE insertions in the two culicinae lineages since their divergence from the An. gambiae lineage. A comparative analysis of the age distribution of the different TE types in the three sequenced mosquito genomes revealed that retrotransposons have consistently been the dominant TE type in the Ae. aegypti lineage over time (Fig. S3). More recently, retrotransposons have become the predominant type of TEs active in all three species.

The C. quinquefasciatus repertoire of 18,883 protein coding genes is 22% larger than that of Ae. aegypti (15,419) and 52% larger than that of An. gambiae (12,457) (Fig. 1C). Our estimated gene number combines ab initio and similarity-based predictions from three independent automated pipelines, optimizing gene identification (6). The relative increase in C. quinquefasciatus gene number is explained in part by the presence of significantly more expanded gene families including olfactory and gustatory receptors, immune-related genes, as well as genes with possible xenobiotic detoxification functions (Table S1). Expert curation of selected gene families revealed expansions in cytosolic glutathione transferases and a substantial expansion of cytochrome P450s. A large cytochrome P450 repertoire may reflect adaptations to polluted larval habitats and have played a role in rendering this species particularly adaptable to evasion of insecticide-based control programs, with several C. quinquefasciatus P450s being associated with resistance (8, 9).

Mosquitoes are the subject of intense efforts aimed at designing novel vector control methods that are often based on the ability of the insect to sense its environment (10, 11). C. quinquefasciatus has the largest number of olfactory receptor related genes (180) of all dipteran species examined to date (Table S1). This expansion may reflect culicine olfactory behavioral diversity, with particular regard to host and oviposition site choice. C. quinquefasciatus females are opportunistic feeders, being able to detect and feed upon birds, humans and livestock depending on their availability. This plasticity in feeding behavior contributes to the ability of C. quinquefasciatus to vector pathogens, such as West Nile virus and St. Louis encephalitis virus from birds to humans. The repertoire of gustatory receptors, which are known to mediate perception of both odorants and tastants (12), has also expanded in C. quinquefasciatus, primarily through a large alternatively-spliced gene locus.

The saliva of blood-sucking arthropods contains a complex cocktail of pharmacologically active components that disarm host hemostasis (13). The ability of C. quinquefasciatus to feed on birds, humans and livestock would suggest that it contains an expanded number of proteins that would increase its ability to imbibe blood from multiple host species. Consistent with this, a large protein family unique to the Culex genus, the 16.7 kDa family, was previously discovered following salivary transcriptome analysis (13). The genome of C. quinquefasciatus revealed 28 additional members of this family.

We have outlined and quantified general similarity and differences at the chromosomal and genomic levels between three disease-vector mosquito genomes, building a foundation for more in-depth future analyses. We found substantial differences in the relative abundance of TE classes among the three mosquitoes with sequenced genomes. Most unexpectedly, this study revealed numerous instances of expansion of C. quinquefasciatus gene families compared to An. gambiae and the more closely related Ae. aegypti. The consequent diversity in many different genes may be an important factor that led to the wide geographic distribution of C. quinquefasciatus.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant HHSN266200400039C, and by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services under contract numbers N01-AI-30071 and HHSN266200400001C. The assembled genome was deposited under Genbank accession AAWU00000000.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Holt R, et al. The genome sequence of the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Science. 2002;298:129–149. doi: 10.1126/science.1076181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nene V, et al. Genome sequence of Aedes aegypti, a major arbovirus vector. Science. 2007;316:1718–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.1138878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Global programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis. WHO Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2009;84:437–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vinogradova EB. Mosquitoes: Taxonomy, Distribution, Ecology, Physiology, Genetics, Applied Importance and Control. Pensoft; Sofia–Moscow: 2000. Culex pipiens pipiens. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cornel AJ, et al. Differences in extent of genetic introgression between sympatric Culex pipiens and Culex quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae) in California and South Africa. J Med Entomol. 2003;40:36–51. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-40.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Information on materials and methods is available on Science Online.

- 7.Mori A, et al. Comparative linkage maps for the mosquitoes (Culex pipiens and Aedes aegypti) based on common RFLP loci. J Hered. 1999;90:160–164. doi: 10.1093/jhered/90.1.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kasai S, et al. Molecular cloning, nucleotide sequence and gene expression of a cytochrome P450 (CYP6F1) from the pyrethroid resistant mosquito, Culex quinquefasciatus Say. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2000;30:163–71. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(99)00114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Komagata O, et al. Overexpression of cytochrome P450 genes in pyrethroid-resistant Culex quinquefasciatus. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;40:146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alphey L, et al. Sterile insect methods for control of mosquito-borne diseases – an analysis. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2010;10:295–311. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2009.0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benedict M, et al. Guidance for Contained Field Trials of Vector Mosquitoes Engineered to Contain a Gene Drive System: Recommendations of a Scientific Working Group. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008;8:127–166. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2007.0273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hallem EA, et al. Insect odor and taste receptors. Annu Rev Entomol. 2006;51:113–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.51.051705.113646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ribeiro JMC, Arcà B. From sialomes to the sialoverse: An insight into the salivary potion of blood feeding insects. Adv Insect Physiol. 2009;37:59–118. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.